1 Department of Human Anatomy and Histology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Xinxiang Medical University, 453000 Xinxiang, Henan, China

2 Department of Pathology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Xinxiang Medical University, 453000 Xinxiang, Henan, China

3 Department of Pathology, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical University, 453000 Xinxiang, Henan, China

4 Micromorphology Laboratory, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Xinxiang Medical University, 453000 Xinxiang, Henan, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a lethal malignancy worldwide. Exosomes are extracellular vesicles derived from the endosomal pathway of nearly all cells and can be found in body fluids. They can be considered an intercellular system in the human body that can mediate near- and long-distance intercellular communication due to their features and functions. Investigations have revealed that exosomes are participated in different processes, physiologically and pathologically, especially in cancer. However, the clinical value of exosomes and their mechanisms of action in CRC are unclear and have not been systematically assessed. The purpose of this review is to discuss how exosomes play a role in the occurrence and development of CRC, with a particular focus on the functions and underlying mechanisms of tumor-derived exosomes as well as non-tumor-derived exosomes. We also describe the evidence that exosomes can be used as diagnostic and prognostic markers for CRC. In addition, the possibilities of exosomes in CRC clinical transformation are also discussed.

Keywords

- colorectal cancer

- exosome

- biomarker

- diagnosis

- clinical transformation

Worldwide, colorectal cancer (CRC) is a common malignant tumor [1]. According to the Global Cancer Statistics 2020, CRC is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer, the second leading cause of cancer death in women, and the third leading cause of incidence and mortality in men [2]. It is a malignancy originating from the mucosal epithelium and glands of the large intestine. Histologically, there are several subtypes of CRC, and approximately 90% of CRCs are adenocarcinomas [3]. Patients with CRC often present with anemia, blood in the stools, aberrant bowel movement, and weight loss [4]. It has been demonstrated that the occurrence of CRC is related to dietary patterns, metabolism, and inflammation [5]. The initiation and progression of CRC may also be affected by environmental and genetic factors [6]. Thus, CRC is the result of a complex multi-step process involving numerous factors and genes. For patients with CRC, the systemic treatment regimens utilized for clinical management include tumor resection, 5-Fluorouracil-based chemotherapy, radiotherapy, anti-angiogenic treatment, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy [7, 8, 9]. Although the death rate of CRC has decreased due to earlier screenings and improved treatments, more than one-third of patients die within 5 years of initial diagnosis, with liver metastases being the most fatal cause of death [10, 11, 12].

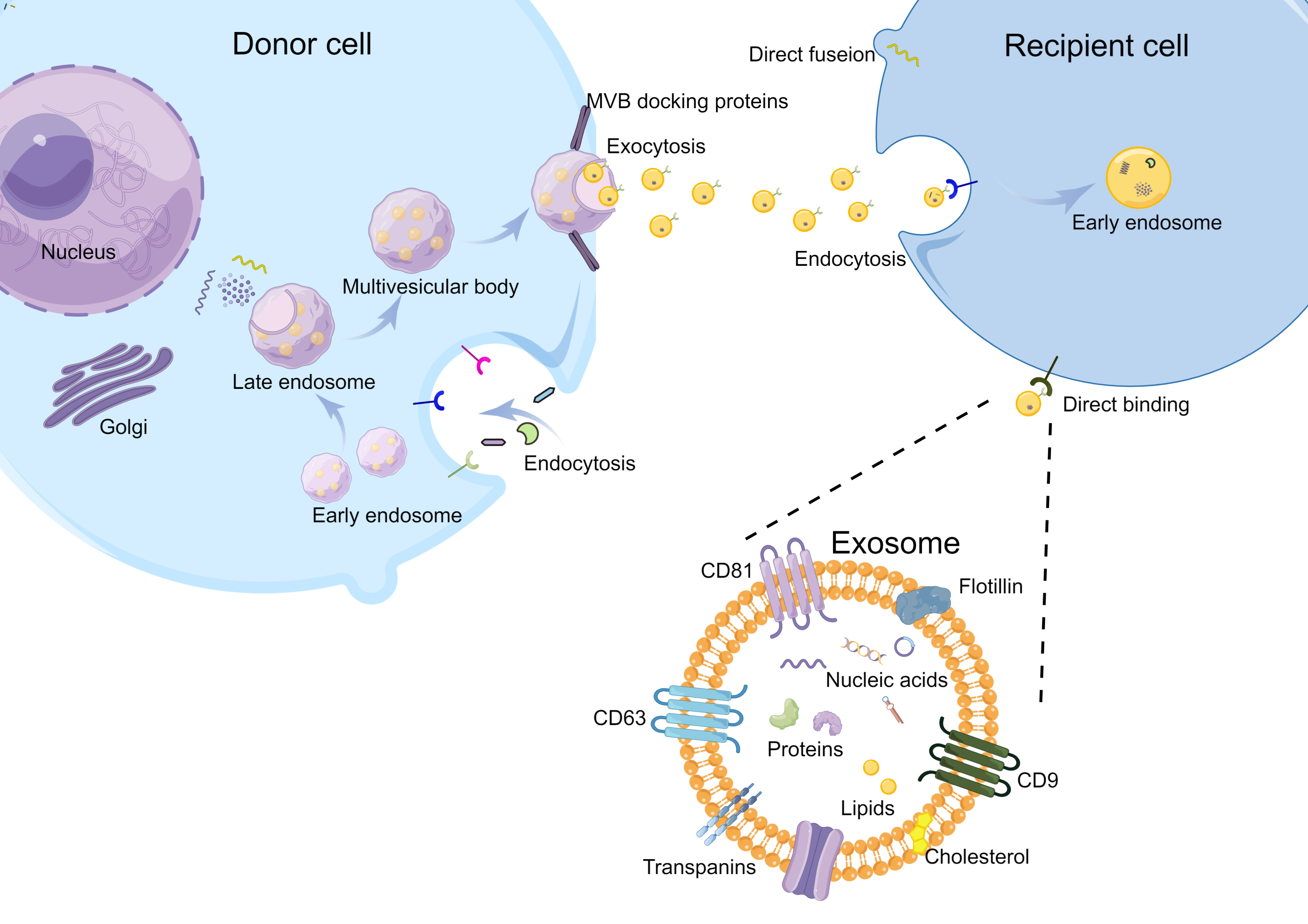

Exosomes are extracellular vesicles (EVs) with diameters ranging from 40 to 160 nm. They are derived from the endosomal pathway of nearly all cells, and they can be found in cell culture fluids, breast milk, blood, urine, pleural effusion, saliva, and other body fluids [13, 14, 15]. Exosomes carry specific cargo consisting of DNA, RNA, cytosolic and cell-surface proteins, metabolites, and lipids. They can be thought of as an intercellular system in the human body that mediate communication between cells and influence a variety of cell biological behaviors [13, 16]. During the generation of exosomes, the plasma membrane is double invaginated, and intracellular multivesicular bodies (MVBs) containing intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) are formed. MVBs fuse to the plasma membrane, and ILVs are ultimately secreted as exosomes through exocytosis. The uptake of exosomes is not random but depends on the surface proteins on the membrane of exosomes and recipient cells [17]. When exosomes encounter suitable recipient cells, exosomes can adhere to the surface of recipient cells through the interaction of ligands and receptors. They can directly fuse with cell membranes or be endocytosed by recipient cells and release the cargo into target cells (Fig. 1) [13, 14]. Numerous studies have shown that exosomes are involved in different physiological and pathological processes, such as inflammatory responses, cancer development, metastasis, and immunity [17, 18].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Biogenesis and intercellular communications of exosomes. The plasma membrane is double invaginated, forming the intracellular multivesicular bodies (MVBs) containing intraluminal vesicles (ILVs). MVBs fuse to the plasma membrane, and ILVs are ultimately secreted as exosomes through exocytosis. The intercellular communications of exosomes depend on the interactions between ligands and receptors. When the exosomes meet the proper recipient cells, they can directly fuse with cell membranes or be endocytosed by recipient cells and release the cargo into target cells.

Recently, it has been demonstrated that exosomes play a role in the occurrence, development, invasion, metastasis, tumor microenvironment (TME) remodeling, chemoresistance, and other processes in CRC [19]. This paper reviews the functions and underlying mechanisms of action of tumor-derived and non-tumor-derived exosomes in CRC, intending to summarize the previous studies on potential biomarkers and effective targets for the treatment of CRC.

Exosomes were first reported as a “type of small vesicles” in 1983, and the name “exosome” was first used in 1989 [20, 21]. They were initially believed to be superfluous membrane vesicles during cell maturation, with the effect of regulating membrane function, removing cellular debris, and eliminating surface molecules [14]. However, exosomes have successfully attracted attention among researchers because of their special roles in multiple facets of cell activity.

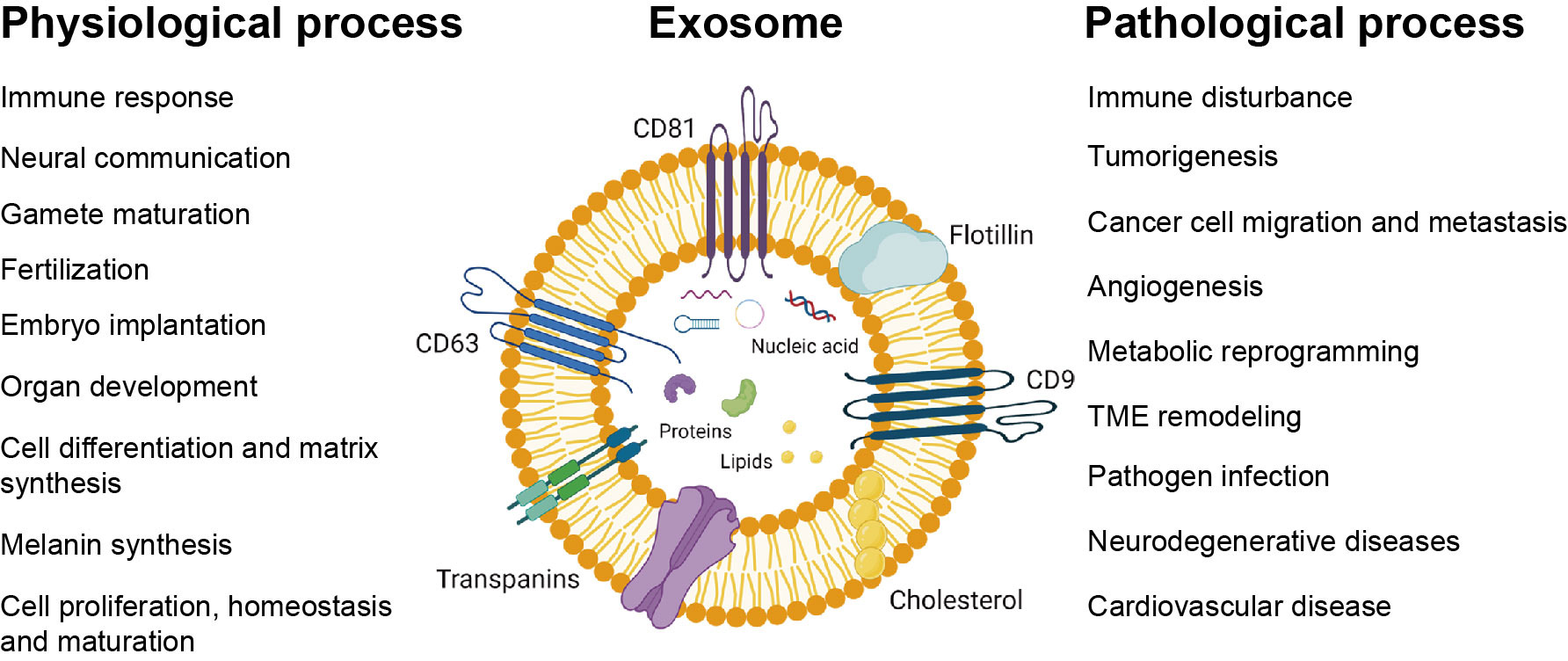

Exosomes can be secreted by the donor cells through exocytosis and accepted by the recipient cells through endocytosis or directly fusing to cell membranes. Thus, exosomes act as a medium in intercellular communications and transmit information to a large number of cells and locations, physiologically or pathologically (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Exosomes play a role in physiological and pathological processes. Exosomes are involved in basic physiological processes such as immune response, neural communication, gamete maturation, fertilization, embryo implantation, organ development, cell differentiation and matrix synthesis, melanin synthesis, cell proliferation, homeostasis, and maturation. They are also involved in some pathological processes, such as immune disturbance, tumorigenesis, cancer cell migration and metastasis, angiogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, tumor microenvironment (TME) formation, pathogen infection, neurodegenerative diseases, and cardiovascular disease.

Exosomes are involved in the signal transduction of the nervous system due to reciprocal signal transfer among sensory and motor neurons, interneurons, and glial cells [22]. Moreover, they play an important role in the aging process [23]. Exosomes also play an important role in reproductive development. They are involved in gamete maturation, fertilization, embryo implantation, immunological communication between the mother and the fetus, and fetal protection by regulating local and/or systemic immune responses, organ development, and melanin synthesis [24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. Additionally, exosomes are related to cell proliferation, homeostasis, and maturation, such as in hepatocytes and reticulocytes [20, 29].

Exosomes are involved in immune response and infection [30, 31]. They participate in antigen presentation and induce the activation of T and/or B cells [32]. The contents of exosomes are involved in regulating innate and adaptive immune responses. It has been demonstrated that the DNA of some intracellular bacteria sorted into exosomes is able to activate innate immune responses or lower antibacterial defenses [33].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that exosomes are widely involved in the occurrence and development of cancers. They are a double-edged sword in tumor growth and progression. For example, exosomes derived from M2 macrophages can inhibit the migration and invasion of glioma cells [34]. Alternatively, the impact of tumor exosomal DNA on inflammatory responses can indirectly worsen cancer [35]. In addition, tumor-derived exosomes can promote immune evasion by cancer cells and generate an immunosuppressive microenvironment [17, 36]. Exosomes derived from tumor cells may be absorbed by surrounding cells and transform the microenvironment into one that is prone to tumor development [37]. They also participate in tumor growth, metastasis, apoptosis, metabolic reprogramming, extracellular matrix degradation, stromal reprogramming, immune surveillance escape, and drug resistance [23, 38, 39]. In addition, exosomes are involved in neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular disease, and pathogenic infections [14, 40].

Numerous studies have explored the relationship between exosomes and the pathogenesis of different cancers. The data demonstrated that exosomes have a relationship with the hallmarks of cancer, such as sustaining proliferation signaling, activating invasion and metastasis, inducing angiogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, and immune evasion [41]. We reviewed the functions and mechanisms of exosomes in CRC, including CRC cell-generated exosomes and non-tumor cell-produced exosomes.

Tumor-derived exosomes (TDEs) were first named in 1981, and it has attracted much attention in the past years [42]. Exosomes act as signal messengers or transducers for communications between cells [43]. Once the recipient cells take up TDEs, the exosomes are internalized, and exosomal contents (such as microRNA, lncRNA, and circRNA) are released. The recipient cells respond to these exosomal contents by changing their phenotypes. This process is finely regulated and specifically determined by complex surface molecules on the extracellular vesicles and the recipient cell membrane [44]. This paper will summarize the functions and mechanisms of tumor-derived exosomes in CRC (Fig. 3; Table 1, Ref. [45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92]).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Mechanism of tumor-derived exosomes in colorectal cancer (CRC). Exosomes derived from CRC cells can transport their cargo to other cells and play an important role in the occurrence and progression of CRC, including tumor growth, invasion and metastasis, angiogenesis, immune evasion, TME remodeling, metabolic reprogramming, and therapy resistance.

| Type | Molecule | Function | Target | Ref. |

| miRNA | miR-934 | Promote colorectal cancer liver metastasis | PTEN | [51] |

| miR-106b | Promote migration, invasion, and metastasis | PDCD4 | [53] | |

| miR-135a-5p | Promote CRC liver metastasis | kinase 2-yes-associated protein-MMP7 axis | [54] | |

| miR-25-3p | Facilitate vascular permeability and angiogenesis | KLF2, KLF4 | [68] | |

| miR-25-3p, miR-130b-3p, miR-425-5p | Enhance M2 polarization of macrophages and induce liver metastasis of CRC | [95] | ||

| miR-208b | Treg expansion, oxaliplatin resistance | PDCD4 | [72] | |

| miR-146a-5p, miR-155-5p | Activate CAFs and enhance the invasive capacity of CRC cells | SOCS1, ZBTB2 | [78] | |

| miR-1246/92b-3p/27a-3p | Promote metastasis | [57] | ||

| miR-21-5p | Induce angiogenesis and vascular permeability | KRIT1 | [69] | |

| miR‐221/222 | Promote metastasis | SPINT1 | [58] | |

| miRNA-335-5p | Promote migration, invasion, and metastasis | RASA1 | [59] | |

| miR-200c-3p | Inhibit migration and invasion, and promote apoptosis after LPS stimulation | ZEB-1 | [60] | |

| miR-46146 | OX resistance | PDCD10 | [89] | |

| miR-106b-3p | Promote metastasis | DLC-1 | [61] | |

| miR-19b | Enhance radioresistance and stemness of CRC cell | FBXW7 | [90] | |

| microRNA-21-5p | Induce an inflammatory premetastatic niche | TLR7 | [63] | |

| miR-1229 | Promote angiogenesis | HIPK2 | [70] | |

| miR-17-5p | Promote CRC cell growth and inhibit anti-tumor immunity | SPOP | [76] | |

| miR‑10a | Promote lung metastasis | [66] | ||

| miR-10b | Activate fibroblasts to become CAFs | PIK3CA | [82] | |

| miR-1255b-5p | Suppress EMT and liver metastasis | hTERT | [67] | |

| miR-224-5p | Promote tumor growth | CMTM4 | [49] | |

| miR-203 | Promote the differentiation of monocytes to M2-TAMs | [83] | ||

| miR-101-3p | Be related to metabolic reprogramming, promote tumor growth, migration, and 5-FU resistance | HIPK3 | [84] | |

| lncRNA | RPPH1 | Promote metastasis and proliferation | TUBB3 | [55] |

| SNHG10 | Contribute to immune escape | INHBC | [73] | |

| lnc-HOXB8-1:2 | Lead to TAM infiltration and M2 polarization | hsa-miR-6825-5p | [74] | |

| CRNDE-h | Promote Th17 cell differentiation | RORγt | [75] | |

| MALAT1 | Promote the invasion and metastasis | miR-26a/26b | [62] | |

| PCAT1 | Promote EMT and liver metastasis | miR-329-3p | [65] | |

| HOTTIP | Increase resistance of CRC cells to mitomycin | miR-214 | [92] | |

| 91H | Enhance CRC metastasis | HNRNPK | [49] | |

| HOTAIR | Impede anti-tumor immunity | PKM2 | [77] | |

| circRNA | CircLPAR1 | Suppress tumor growth | eIF3h | [45] |

| CircPACRGL | Promote proliferation, invasion, migration, and differentiation of N1 to N2 neutrophils | miR-142-3p/miR-506-3p | [52] | |

| Circ-133 | Promote cell migration | GEF-H1 | [56] | |

| Circ_0005963 | Promote chemoresistance | miR-122 | [86] | |

| circ_0000338 | Improve the chemoresistance | miR-217 and miR-485-3p | [88] | |

| circ_0094343 | Inhibit proliferation, clone formation, and glycolysis | miR-766-5p | [46] | |

| circ_PTPRA | Induce CRC cell cycle arrest and inhibited cell proliferation | miR-671-5p | [47] | |

| circ-FBXW7 | Ameliorate chemoresistance to oxaliplatin in CRC | miR-128-3p | [91] | |

| circEPB41L2 | Suppress CRC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and promote apoptosis | miR-21-5p, miR-942-5p | [48] | |

| Others | HSPC111 | Altered lipid metabolism of CAFs and promote liver metastasis | ACLY | [79] |

| p-STAT3 | Promote 5-FU resistance | [87] | ||

| ANGPTL1 | Attenuate CRC liver metastasis | MMP9 | [80] | |

| CXCL16 | Promote metastasis | [57] | ||

| Wnt4 | Enhance migration and invasion | [64] | ||

| IRF-2 | Remodel the lymphatic network and promote metastasis | VEGFC | [70] | |

| CXCL1, CXCL2 | Attract CRCSC-primed neutrophils to promote tumorigenesis of CRC cells | IL-1β | [81] | |

| Wnt4 | Promote Angiogenesis | β-Catenin | [71] | |

| β-catenin | promote cancer progression | Wnt signaling pathway | [50] | |

| KRAS | Alter the metabolic state of recipient colonic epithelial cells | [85] |

One of the typical hallmarks of cancer is sustaining proliferation signaling,

ultimately causing the rapid growth of the tumor. CRC tumor-derived exosomes

(CTDEs) can regulate the growth of CRC cells through a variety of pathways, such

as involvement in cell proliferation, cell cycle, and apoptosis. For example,

circLPAR1 is encapsulated by CRC cell exosomes, internalized by CRC

cells, and inhibits tumor growth. The investigation of underlying mechanisms

showed that exosome circLPAR1 might bind to eIF3h directly and

inhibit METTL3-eIF3h interaction, ultimately reducing the

translation of BRD4 [45]. Exosome-carried circ_0094343 derived

from CRC cells plays an inhibitory role in the proliferation and clone formation

of HCT116 cells via the miR-766-5p/TRIM67 axis [46]. Exosomal

circ_PTPRA can function as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) and

increase the expression of SMAD4 by binding to miR-671-5p,

ultimately inducing CRC cell cycle arrest and inhibiting cell proliferation [47].

It has also been demonstrated that a hypoxic microenvironment in CRC may promote

tumor cells to release exosomes rich in miR-410-3p. These exosomes may

transfer to normoxic cells and enhance the proliferation of normoxic CRC cells

[93]. Exosomal circEPB41L2 derived from CRC cells could suppress CRC

cell proliferation and promote apoptosis by serving as a sponge for

miR-21-5p and miR-942-5p and regulating the PTEN/AKT

signaling pathway [48]. CRC cell exosome miR-224-5p promotes cell

proliferation by downregulating CMTM4, thus promoting the malignant

transformation of human normal colonic epithelial cells [49]. Oncogenic mutant

Invasion and metastasis are the leading causes of cancer-associated death in

patients with CRC; however, the molecular mechanisms underlying tumor invasion

and metastasis are complex and elusive [94]. Numerous studies have shown that

CTDEs are associated with the invasion and metastasis of CRC. For example,

tumor-derived exosomes miR-934 can target PTEN, resulting in

downregulation of the PTEN expression, which in turn activates the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway to induce M2 macrophage polarization,

ultimately promoting CRC liver metastasis [51]. Cancer-derived exosomal

circPACRGL can absorb miR-142-3p/miR-506-3p as a sponge and

facilitate the TGF-

Angiogenesis is critical for tumor growth, survival, and progression. The

process is very complex, including the degradation of the vessel’s basement

membrane, the activation, proliferation, and migration of vascular endothelial

cells, and reconstruction to form new blood vessels and networks [102].

Tumor-derived exosomes are largely involved in this process [103]. This has been

demonstrated in the angiogenesis of CRC. For example, exosomal

miR-25-3p, which is CRC cell-derived, directly targets KLF2 and

KLF4 and regulates VEGFR2, ZO-1, claudin5,

and occludin expression in endothelial cells, consequently promoting

vascular permeability and angiogenesis [68]. Exosomal miR-21-5p, which

is secreted by CRC cells, induces angiogenesis and vascular permeability by

targeting KRIT1 [69]. MiR-1229, which is derived from the CRC

cell exosomes, inhibits the expression of HIPK2 protein, thus activating

the VEGF pathway and promoting angiogenesis [70]. Exosomal Wnt4

derived from CRC cells increases

Exosomes are important in modulating tumor immune response and have a dual role.

They may activate immune responses or exhibit strong pro-tumor immune reactions

[17]. Numerous studies have revealed CRC tumor-derived exosomes (CTDEs) can

function as mediators of host anti-tumor immune responses and tumor cell immune

evasion. For example, miR-208b is secreted by colon cancer cells and

sufficiently transported to recipient T cells. In T cells, miR-208b,

which is delivered by exosomes, directly targets PDCD4 and induces

immune evasion [72]. The CRC cell-derived exosomal lncRNA SNHG10s can be

taken up by NK cells and suppress the function of NK cells by upregulating

INHBC expression. It has been suggested that exosomal lncRNA

SNHG10 could lead to the inhibition of NK cells, ultimately contributing

to immune escape [73]. Exosomes containing Lnc-HOXB8-1:2 are secreted by

neuroendocrine differentiated CRC cells, and Lnc-HOXB8-1:2 from exosomes

competitively binds hsa-miR-6825-5p as ceRNA relieves the inhibitory

effect of hsa-miR-6825-5p on CXCR3 expression, upregulates its

expression, and then leads to TAM infiltration and M2 polarization, and promotes

immune evasion of CRC [74]. CRNDE-h, which is derived from tumor cells,

could inhibit ubiquitination and degradation of ROR

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex internal environmental system

around tumor cells, which plays an essential role in tumorigenesis. CTDEs in the

TME are essential in the formation and reprogramming of the TME. For example,

miR-146a-5p and miR-155-5p contained in CRC cell exosomes can

be secreted by CRC cells and taken up by the cancer-associated fibroblasts

(CAFs). Then, they may activate CAFs through JAK2-STAT3/NF-

Metabolic reprogramming is an adaptive mechanism that enables tumor cells to regulate the flow of their energy to meet their needs for rapid growth. It is manifested by an increase in glucose uptake and an enhancement of glycolysis under aerobic conditions, as well as high production of lactate. These metabolic changes are also known as the “Warburg effect” [104]. A growing number of studies have shown that exosomes can mediate metabolic reprogramming in cancer [105]. As in CRC, hsa-miR-101-3p, which is derived from CRC cell exosomes, is associated with metabolic reprogramming in CRC by targeting HIPK3 [84]. Moreover, mutant KRAS exosomes are able to cause a Warburg-like effect on recipient colonic epithelial cells [85].

It has been demonstrated that the delivery of exosomal cargos between different cancer cells is associated with tumor drug resistance [106]. Exosomes are used as carriers for cell-to-cell communication in the tumor microenvironment, however; drug-resistant tumor cells can also use this property to develop resistance to sensitive cells [107]. Therapy-resistance mechanisms mediated by CTDEs are summarized as follows: hsa_circ_0005963 is involved in chemoresistance in CRC. The exploration of underlying mechanisms showed that hsa_circ_0005963 could be a sponge for miR-122 [86]. Tumor-secreted miR-208b directly targets PDCD4 and promotes Treg expansion, and it may be associated with a decrease of oxaliplatin (OX)-based chemosensitivity in CRC [72]. It is also demonstrated that exosomes from RKO/R cells are able to promote acquired 5-FU resistance in CRC, which is mainly related to p-STAT3 contained in the exosomes [87]. Circ_0000338 is present in exosomes and improves the chemoresistance of CRC cells by targeting miR-217 and miR-485-3p [88]. Exosome miR-46146 can be an important promoter of OX resistance by targeting PDCD10 and may be a potential target for OX resensitization by CRC cells [89]. MiR-19b can be present in exosomes secreted by CRC cells. By delivering miR-19b, CRC-derived exosomes enhance the radiation resistance and stemness characteristics of CRC cells. Accordingly, miR-19b inhibition can enhance the efficacy of radiotherapy and reduce the stemness characteristics of CRC, suggesting that miR-19b inhibition may be a promising strategy for sensitization of CRC cells to radiotherapy [90]. Exosomal circ-FBXW7 can improve the chemoresistance of CRC to OX by direct binding to miR-128-3p, which provides a promising treatment strategy for patients with OX-resistant CRC [91]. Exosomal circATG4B plays an important role in chemoresistance in CRC. The underlying mechanisms show that it can competitively bind to TMED10, prevent TMED10 from binding to ATG4B, and induce increased autophagy, ultimately promoting chemotherapy resistance [108]. Exosomal long non-coding RNA HOTTIP derived from mitomycin-resistant CRC cells can be transferred into the parental cells and increase the resistance of CRC cells to mitomycin via impairing miR-214-mediated degradation of KPNA3 [92].

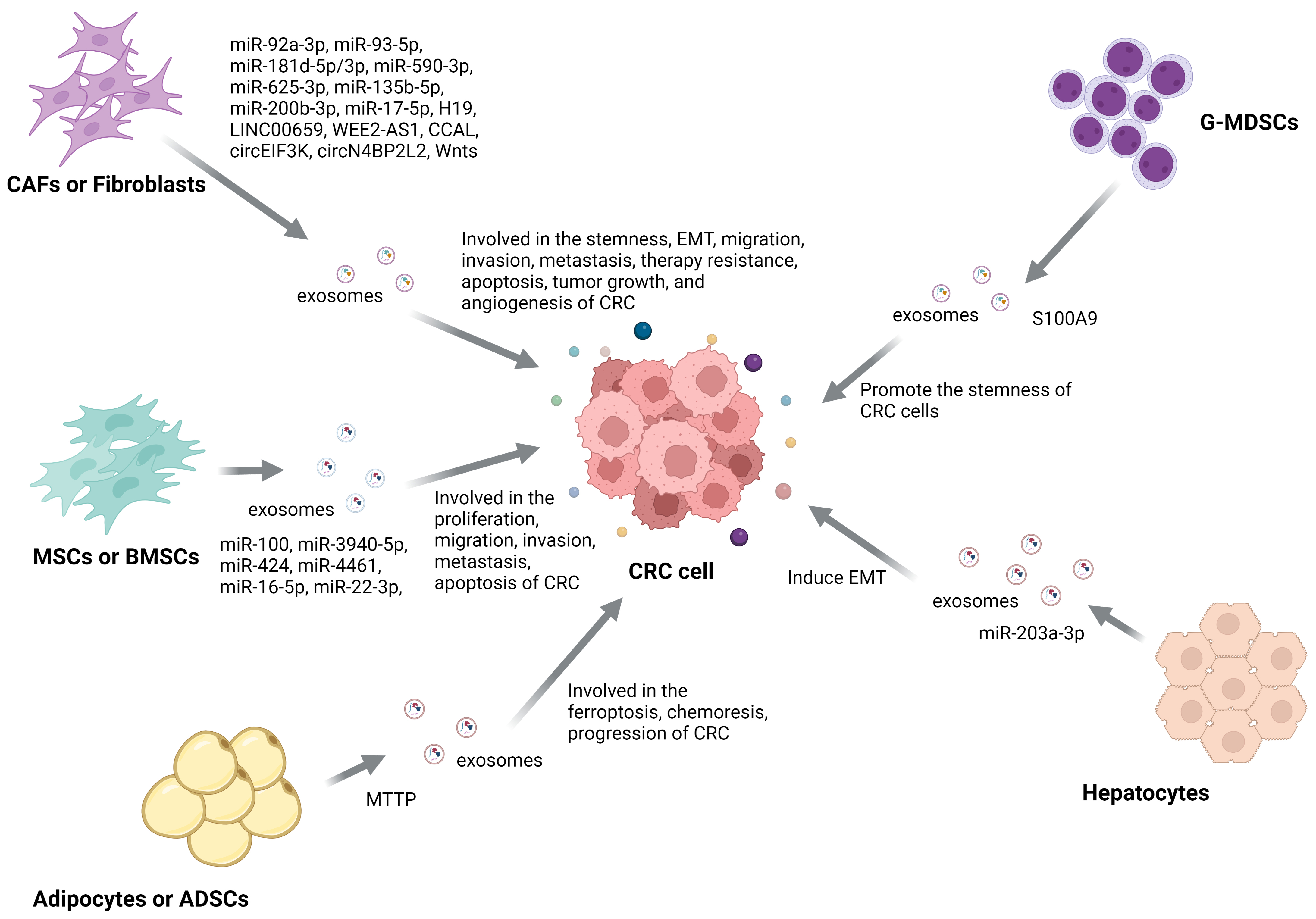

Although tumor cells are the main cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME), there are also many other cells, such as fibroblasts, immune cells, endothelial cells, etc. [109]. Exosomes secreted by non-CRC cells in the TME may also affect the fate of CRC cells. Here, we summarize the functions and mechanisms of non-tumor-derived exosomes in CRC (Fig. 4; Table 2, Ref. [110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134]).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.The Mechanism of non-tumor-derived exosomes function in CRC. Exosomes derived from non-CRC cells can transport their cargo to CRC cells and affect most pathological processes in CRC, including stemness, EMT, migration, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, apoptosis, tumor growth, and therapy resistance.

| Type | Molecule | Source | Function | Target | Ref. |

| miRNA | miR-92a-3p | CAFs | Promote the stemness, EMT, metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance of CRC cells | FBXW7, MOAP1 | [110] |

| miR-93-5p | CAFs | Against radiation-induced apoptosis | FOXA1 | [112] | |

| miR‑181d‑5p | CAFs | Inhibit 5-FU sensitivity | NCALD | [115] | |

| miR-181b-3p | CAFs | Promote the occurrence and development of CRC | SNX2 | [116] | |

| miR-100 | MSCs | Suppress proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis and induce apoptosis | mTOR | [126] | |

| miR-3940-5p | MSCs | Inhibit the growth, metastasis, invasion, and EMT of CRC cells | ITGA6 | [127] | |

| miR-590-3p | CAFs | Enhance radioresistance in CRC | CLCA4 | [118] | |

| miR-625-3p | CAFs | Promote migration, invasion, EMT, and chemotherapeutic resistance in CRC cells | CELF2 | [119] | |

| microRNA-135b-5p | CAFs | Promote CRC cell growth and angiogenesis | TXNIP | [120] | |

| miR-424 | BMSCs | Promote progression of CRC | TGFBR3 | [129] | |

| miR-200b-3p | CAFs | Increase sensitivity to 5-FU | HMGB3 | [122] | |

| miR-4461 | BMSCs | Inhibit migration and invasion | COPB2 | [128] | |

| microRNA-16-5p | BMSCs | Inhibit proliferation, migration, and invasion, while promoting apoptosis | ITGA2 | [130] | |

| miR-203a-3p | hepatocyte | Induce EMT | Src | [134] | |

| miR-17-5p | CAFs | Contribute to tumor progression | RUNX3 | [123] | |

| miR-22-3p | BMSCs | Suppress CRC cell proliferation and invasion | RAP2B | [131] | |

| LncRNA | H19 | CAFs | Promote the stemness and chemoresistance of CRC | miR-141 | [111] |

| LINC00659 | CAFs | Promote CRC cell proliferation, invasion, and migration | miR-342-3p | [113] | |

| WEE2-AS1 | CAFs | Facilitate tumorigenesis and progression | MOB1A | [121] | |

| CCAL | CAFs | Promote oxaliplatin resistance of CRC cells | HuR | [124] | |

| circRNA | circEIF3K | CAFs | Promote the progression of CRC | miR-214 | [114] |

| cricN4BP2L2 | CAFs | Promote the CRC cell stemness and oxaliplatin resistance | EIF4A3 | [117] | |

| Others | MTTP | Adipocyte | Suppress ferroptosis, promote chemoresistance | PRAP1 | [133] |

| S100A9 | G-MDSCs | Promote the stemness of CRC cells | [132] | ||

| Wnts | Fibroblasts | Induce the dedifferentiation of cancer cells to promote chemoresistance | [125] |

For example, CAFs are the main stromal cells in TME. CAFs can transfer exosomes

that are rich in miR-92a-3p directly to CRC cells and increase the

expression of miR-92a-3p in CRC cells significantly. In CRC cells,

miR-92a-3p directly targets FBXW7 and MOAP1,

ultimately promoting the stemness, EMT, metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance

of CRC cells [110]. CAFs can deliver H19 in exosomes to CRC cells,

promoting the stemness and resistance of CRCs. Mechanistically, H19

activates the

Exosomes from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are closely related to the

therapeutic efficacy of MSCs. After being ingested by CRC cells, MSC exosomes can

exert their effects through the miR-100/mTOR/miR-143 axis in CRC cells,

inhibiting the proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis of CRC cells

and inducing CRC cell apoptosis. It suggests that MSC-exosome treatment and

miR-100 restoration might be considered potential therapeutic strategies

for CRC [126]. MSC-exosomal miR-3940-5p inhibits the growth, metastasis,

invasion, and EMT of CRC cells by targeting ITGA6 and the following

TGF-

Some other cells may also affect the fate of CRC cells. For example, Granulocytic Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (G-MDSCs) promote the stemness of CRC cells through exosomal S100A9 [132]. Adipocyte-derived exosomal MTTP could suppress ferroptosis and promote chemoresistance in CRC [133]. MiR-203a-3p derived from hepatocyte exosomes increases the expression of E-cadherin in CRC cells and inhibits Src expression, which in turn leads to a decrease in the invasion rate of CRC cells [134].

Due to their unique properties, exosomes contribute to many aspects of precise tumor diagnosis and treatment, including predicting prognosis and drug efficacy, dynamic monitoring, and precisely targeted drug delivery [14].

Because of the various cargos in the exosomes and the typical features on the surface of exosomes, they can reflect the status of their parent cells. Thus, exosomes have emerged as a platform with potentially broader and complementary applications to be used in the field of liquid biopsy for the diagnosis, prognostic analysis, and monitoring of cancer [135]. In this manuscript, we summarized the exosomes used in the diagnosis and prognosis of CRC (Table 3, Ref. [55, 58, 72, 75, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166]).

| Type | Exosomes | Clinical Potential | Ref. |

| miRNA | miR-208b | A predictive biomarker for oxaliplatin-based therapy response | [72] |

| miR‐221/222 | A prognostic marker and potential therapeutic target for CRC with liver metastasis | [58] | |

| miR-7641 | A molecular biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis of CRC | [167] | |

| miR-96-5p and miR-149 | A biomarker for early detection of CRC | [169] | |

| miR-377-3p and miR-381-3p | Circulating biomarkers for diagnosis of CRC | [136] | |

| miR-1539 | A potential biomarker for screening and a predictor of poor clinicopathological behavior in CRC | [138] | |

| miR-150-5p and miR-99b-5p | Serve as diagnostic biomarkers for CRC | [139] | |

| miR-3937 | A potential liquid biopsy marker for CRC | [140] | |

| miR-548c-5p | A critical biomarker for CRC diagnosis and prognosis | [141] | |

| miRNA-139-3p | A biomarker for early diagnosis and metastasis prediction in CRC | [143] | |

| miR-424-5p | A biomarker for early diagnosis in CRC | [75] | |

| miR-320d | A biomarker for metastatic CRC | [144] | |

| miR-221 | An independent prognostic factor for CRC | [145] | |

| miR-874 | An independent prognostic factor for overall survival of CRC patients | [148] | |

| miR-17-5p and miR-92a-3p | A prognostic biomarker for primary and metastatic CRC | [150] | |

| miR-21 | A predictor of recurrence and poor prognosis in CRC | [152] | |

| miR-6869-5p | A circulating biomarker for the prognosis of CRC | [153] | |

| miR-122 | A potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for CRC with liver metastasis | [154] | |

| miR-150 | A potential prognostic factor and treatment target for CRC | [157] | |

| miR-150-5p | A novel non-invasive biomarker for CRC diagnosis and prognosis | [159] | |

| miR-125b-5p | Be potentially correlated with a more aggressive CRC phenotype | [161] | |

| miR-92b | A promising biomarker for early detection of CRC | [162] | |

| miR-126, miR-1290, miR-23a, and miR-940 | Potential biomarkers for early diagnosis of CRC | [164] | |

| microRNA-125b | A biomarker of resistance to mFOLFOX6-based chemotherapy in CRC | [165] | |

| miR-181b, miR-193b, miR-195, and miR-411 | A predicter for lymph node metastasis in T1 CRC patients | [166] | |

| LncRNA | RPPH1 | A potential biomarker for diagnosis and therapy in CRC | [55] |

| GAS5 | An independent prognostic factor for CRC | [145] | |

| FOXD2-AS1, NRIR, and XLOC_009459 | Biomarkers for the diagnosis of CRC | [151] | |

| UCA1 | A predicter for therapeutic efficacy of cetuximab in CRC patients | [156] | |

| CCAT2 | A potential predictor of CRC | [163] | |

| circRNA | circCOG2 | A biomarker for poor prognosis and a therapeutic target for CRC | [137] |

| circ-0004771 | A novel potential diagnostic biomarker of CRC | [146] | |

| circ_0006174 | A biomarker for the diagnosis of chemoresistance in CRC | [147] | |

| circ-PNN | A potential biomarker for the detection of CRC | [155] | |

| Others | FZD10 | A biomarker for prognosis and diagnosis of CRC | [168] |

| GPC1 | A biomarker for early detection of CRC | [169] | |

| CPNE3 | A diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for CRC | [142] | |

| FGB and |

Biomarker for diagnostic efficacy of early CRC | [149] | |

| QSOX1 | A marker for early diagnosis and non-invasive risk stratification in CRC | [158] | |

| KRAS | A predictor for outcome in CRC patients with metastasis | [160] |

Exosomal LncRNA RPPH1 levels in blood plasma are higher in untreated

CRC patients but lower after tumor resection. It displayed a better diagnostic

value (AUC = 0.86) compared to CEA and CA199 and could serve as

a potential target for therapy and diagnosis in CRC [55]. The miR-208b

derived from exosomes of CRC cells can promote Treg amplification by regulating

PDCD4, and it has the ability to reduce the sensitivity of

oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in CRC. These research results suggest that the

exosomal miR-208b can serve as a biomarker for predicting oxaliplatin

treatment response and may become a new target for immunotherapy [72]. Exosomal

miR-221/222 promotes CRC progression and may serve as a novel prognostic

marker and therapeutic target for CRC with liver metastasis [58]. By deep

sequencing, it has been demonstrated that miR-7641 has the potential to be a

candidate for the non-invasive and specific molecular markers for CRC diagnosis

and prognosis [167]. Exosome-delivered FZD10 increases Ki-67

expression via Phospho-ERK1/2 and may be a promising novel prognostic

and diagnostic biomarker for CRC [168]. Elevated plasma GPC1

Because of the properties and functions of exosomes, they can be designed for drug or functional nucleic acid delivery [170] and have the therapeutic potential to be used in the treatment of CRC. For example, engineered exosomes have been used to simultaneously deliver the anticancer drug 5-FU and the miR-21 inhibitor oligonucleotide (miR-21i) to Her2-positive cancer cells. The results revealed that systematic administration of exosomes loaded with 5-FU and miR-21i in tumor-bearing mice showed significant anti-tumor effects in colon cancer [171]. Studies have shown that the expression of PGM5 antisense RNA 1 (PGM5-AS1) in colon cancer is induced by GFI1B. PGM5-AS1 prevents colon cancer cells from proliferating, migrating, and acquiring oxaliplatin tolerance, and engineered exosomes that co-deliver PGM5-AS1 and oxaliplatin can reverse colon cancer resistance [172]. MiR-506-3p delivered to CRC cells via exosomes reduces CRC proliferation and induces apoptosis, suggesting that delivery of miR-506-3p to CRC cells via exosomes may become a novel diagnosis and treatment method for CRC [173]. Tumor-derived exosomes (TEXs) may induce beneficial anti-tumor immune responses, and TEXs have shown certain beneficial anti-tumor properties in addition to miRNA delivery functions, suggesting that the introduction of TEX-miR-34a may be a new promising approach for combination therapy for CRC [174]. Studies have shown that dendritic cells are loaded with exosomes from cancer stem cell-rich spheroids, which may be a new potential immunotherapy approach [50]. It has been reported that the ascites-derived exosomes (Aex), in combination with the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), could be used in the immunotherapy of CRC. The phase I clinical trial suggested that AEX combined with GM-CSF immunotherapy for advanced CRC is feasible and safe and may be an alternative to immunotherapy for advanced CRC [175].

Although exosomes have been considered promising emerging therapeutic options and tumor neo-antigen drug delivery tools and carriers in tumor precision therapy, there are still many issues waiting to be resolved. Nowadays, exosomes can be isolated and purified by ultracentrifugation, density gradient centrifugation, polymer precipitation, ultrafiltration, and size exclusion chromatography; however, flexible and fast detection platforms are still lacking. Moreover, how to load exosomes with specific cargo still need to be explored. Because few studies have focused on the fusion-based loading methods present, their detrimental effects on recipient cells remain unclear [14].

Exosomes are derived from the endosomal pathway of nearly all cells and may be considered a cell-to-cell system in the human body that can mediate near- and long-distance intercellular communication and affect various aspects of cell biology. They are involved in different physiological and pathological processes, such as the communication of the nervous system, reproduction and development, inflammatory responses, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer development.

CRC is one of the most highly malignant tumors worldwide. Numerous studies have revealed that exosomes play important roles in tumor growth, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, immune evasion, TME remodeling, metabolic reprogramming, therapy resistance, and some other processes of CRC. Because of these features and functions of exosomes, they may be used in the fields of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of CRC. We have reviewed the current state of studies focused on the exosomes in CRC. We have compared the effects of tumor-derived and non-tumor-derived exosomes on the processes of CRC, summarized the clinical value of various types of exosomal cargos, and presented the potential of exosomes to be used in the clinical transformation process.

However, there are still many issues waiting to be resolved before exosome-based therapy can be used in the clinical treatment of CRCs. First, it is still a problem to obtain a large number of exosomes quickly so far. The isolation and purification of exosomes can be realized by the following methods, such as separation based on the size of density or particle, sedimentation or phase, affinity, microfluidic systems, or thermophoretic enrichment. However, the efficiency, quantity, and quality of exosomes separated by different separation methods are different, and there is still a lack of unified methods that can quickly and effectively obtain exosomes. Moreover, how to equip exosomes with specific drugs is also a problem. There are two methods for loading exosomes with drug, endogenous and exogenous. The two methods both have their own disadvantages; the endogenous method is not accurate in quantifying the specific substances in the exosomes, while the loading efficiency is not high using the exogenous methods. Thus, how to equip exosomes with specific drugs is also a question that needs to be resolved. Furthermore, the long-term efficacy and safety of using exosomes in the treatment of CRC remain unclear. Therefore, there is a need for comprehensive clinical studies or trials of exosomes used in CRC. It is possible that with technological developments and further clinical trials, exosomes will be a real emerging tool for the “cell-free” treatment of CRC.

Conceptualization: JH, YH; writing - original draft preparation: JH, SM, YZ, BW, SD, YH; writing – review and editing: JH, YH; visualization: SM, YH; analyzing: YZ, BW, SD; interpreting data from the reviewed literature, JH, SM, YZ, BW, SD; supervision: YH. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Thanks Dr. Jiateng Zhong for the contribution to review and editing.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82203350), Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (No. 212300410223), and the Xinxiang Medical University (No. XYBSKYZZ201820), Teaching and Research Cultivation Project of School of Basic Medical Sciences, Xinxiang Medical College (No. JCYXYKY202021), the Open Project Program of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical University (No. KFKTYB202125).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.