1 Faculty of Economics, Aurel Vlaicu University of Arad, 310032 Arad, Romania

2 Department of Law, Management Science and Economics, Daugavpils University, 5401 Daugavpils, Latvia

Abstract

In the contemporary dynamic world, the integration and advancements of artificial intelligence (AI) have become a global phenomenon with a profound impact on human life and the ability to generate value across various industries and business sectors. The present study integrates four personality-based traits—innovativeness, optimism, discomfort, and insecurity—to explore how professionals from the legal field perceive this technology and their readiness to incorporate digital legal tools and AI in their profession. To empirically validate the proposed research hypotheses, a quantitative research method was employed. The quantitative data analysis was carried out using partial least squares structural equation (PLS-SEM) modelling. Conducted in two Eastern European countries, Latvia and Romania, the research findings indicate that an optimistic mindset drives innovation and generates new opportunities for professionals to use AI tools effectively, enhance efficiency, and solve emerging challenges within the field. The findings offer guidance for policymakers in developing policies, training programs, and communication strategies to facilitate a smooth transition to AI-based practice, support practitioner training, and build community confidence by clarifying AI’s capabilities and constraints.

Keywords

- artificial intelligence

- personality-based traits

- readiness

- Latvia

- Romania

The global boom of artificial intelligence (AI) is one of the main and biggest challenges of the contemporary world, bringing a new era that will reshape and fundamentally transform the existence of individuals, businesses, and society as a whole. Nowadays, the use of AI is on the rise in both private and public domains, integrating itself into our daily life and exerting a growing impact across different aspects of human existence. This is also the case with the fusion of this advanced technology and the legal field, where digital legal tools and AI have the potential to revolutionize the practice of law, bringing new opportunities and major challenges. Thus, given its widespread adoption, AI disrupts the future of legal work and is anticipated to be a key component in shaping a new era of law. However, AI technology applications in the legal field, as well as in other fields, depend on how users perceive the advantages provided by this technology and their readiness to acquire the necessary skills and knowledge to incorporate AI applications into their current operations.

At the individual level, the willingness to adapt and use advanced technology depend on the attitudes of potential users, as they may consider themselves unprepared or prepared for the new advanced technology (Dabija and Vătămănescu, 2023). Parasuraman (2000) identifies four personality traits—optimism, innovativeness, discomfort, and insecurity—that predict a person’s willingness to adopt new technology. According to Pelau et al (2021), the continued integration and advancement of AI in everyday life and in various activity fields is associated with both positive emotions and attitudes, as well as concerns and negative feelings about its future trajectory. To successfully implement advanced technology, scholars have emphasized the necessity and importance of evaluating the readiness of all potential users (Cramarenco et al, 2023), considering that this assessment will provide valuable insights into potential threats as well as possible solutions to address these threats (Yosser et al, 2020; Moravec et al, 2024). Therefore, the integration of AI technology can play a major role and has the potential to revolutionize the field of law; however, it is crucial for legal professionals to be open to learning and using new tools and applications.

Considering these challenges, the purpose of the present study is to explore the attitudes and readiness of legal professionals regarding AI adoption and application in their professional fields. In this study, AI adoption and application refers to the awareness, acceptance, and practical use of various digital tools and AI technologies such as natural language processing, rule-based systems, machine learning, predictive algorithms, and automation tools, in shaping a new era of law and improve efficiency, decision-making, and service delivery. This study provides an empirical assessment of four independent variables associated with AI readiness arising from individual personality-based traits. Readiness for AI adoption is the dependent variable of this study, reflecting an individual’s openness, preparedness, and psychological willingness to engage with AI technologies. Attitude is reflected through the four independent variables optimism, innovativeness, discomfort, and insecurity. These personality-based traits, designed and developed by Parasuraman (2000), have been widely used in different contexts and fields and have received considerable attention in decision-oriented research, where technology-based innovation is crucial (Abdul Hamid, 2022; Blut and Wang, 2020). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to evaluate the proposed research hypotheses. A total of 394 respondents with legal professions from two Eastern European countries participated in this research, of which 263 were from Romania and 131 from Latvia.

The contribution of this study is supported by the actual significance given to the global boom of AI in everyday life and in various activity fields. This study attempts to extend the existing body of knowledge by strengthening the predictive power of individual psychological traits—innovativeness, optimism, discomfort, and insecurity—on legal professionals’ attitudes towards incorporating digital legal tools and AI in their profession. We thus contribute by incorporating the technological readiness model developed by Parasuraman (2000) in deeply regulated and traditionally conservative fields, such as the legal one, and within an Eastern European cultural and geographic area. Integrating this model into the legal context and within a distinct geographic and cultural setting represents a novel approach to understand the attitudes and readiness of legal professionals regarding AI adoption and application. The study offers actionable implications for policymakers in developing AI literacy campaigns, skills development programs, and communication strategies to facilitate a smooth transition to AI-based practice as well as build community confidence through understanding AI capabilities and constraints. At the present time, according to our knowledge, in the context of the fusion of AI technology and the field of justice, the literature available is limited. In addition, no empirical research has utilized this approach and PLS-SEM to explore the attitudes and readiness of AI adoption and application in this field and within this Eastern European geographic area and cultural setting.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, the authors review the scientific literature and develop the research hypotheses. The third section describes the research sample, data collection, the questionnaire measures and the results. The present study ends with research conclusions, limitations, and avenues for future research.

The rapid advancements achieved in recent years in the field of AI, as well as the wide range covered by its specific applications and devices, have generated significant changes at the level of human society, and have already had a great impact on all facets of human existence. Within the framework of an accelerated digital shift (Balcerzak et al, 2023), artificially designed systems have been successfully applied across various types of industries and business fields. Gursoy et al (2019) investigated how AI-based technologies changed client experiences in the hospitality industry, while Du and Gao (2022) examined the integration of AI into China’s public healthcare system, demonstrating greater efficiency as well as resilience. Pelau et al (2021) investigated how Romanian logistics businesses used AI tools for route optimization, whereas Karaca et al (2021) examined automation in Turkish manufacturing, showing productivity improvements with job displacement problems. Lăzăroiu and Rogalska (2023) found that generative artificial intelligence contributes to partial job loss, particularly for regular and repetitive professions, while enhancing labor productivity through automation and intelligent work allocation. Furthermore, the use of cognitive digital twins, the Internet of Robotic Things, and multi-sensory extended reality environments is changing organizational design in manufacturing and logistics (Lăzăroiu et al, 2024). In addition, blockchain-integrated fintech ecosystems are deploying generative artificial intelligence algorithms to enhance transparency, automate risk assessment, and allow smart contract execution in decentralized financial environments (Lăzăroiu et al, 2023; Andronie et al, 2024). These developing technologies not only disrupt established processes, but they also need a considerable reorganization of roles, skills, and training, both on an individual and institutional level.

AI greatly influences not only the activities of companies, organizations, or institutions, but also personal life at the individual level, through the applications used to an increasing extent. All of these findings confirm that AI integration and advances are certainly possible in the field of justice. In addition to individuals from various other work fields, professionals from the legal environment face the need to manage large amounts of information, make decisions, and draw conclusions based on initial data. Recent studies and debates among researchers, experts, and legal practitioners from different countries have highlighted the ever-greater emphasis on the implementation and utilization of AI tools in the justice context, particularly in lawyers’ work. The progress of AI implementation and use in traditional legal structures is highlighted in the study of Putra et al (2023), who provided examples from existing practices in China, the USA, and Estonia, either from the perspective of supporting legal data analysis or from the perspective of simulating judicial decisions using past information. Such examples demonstrate that technology, such as AI, can be integrated into traditional legal practices to enhance accessibility and the efficiency of legal services, as well as to ensure speed and accuracy in resolving legal cases.

According to prior scholars, AI can be involved in performing routine programmable tasks, such as analyzing and processing case files, transferring documents to courts, and managing legal files (Holder et al, 2016). Regarding the work of lawyers, recent studies, such as Jiang et al (2023), have found that AI systems, such as robot lawyers, can improve the performance of legal professionals by managing repetitive tasks. However, Tung (2019) and Xu et al (2022) argue that while AI tools can simplify case analysis and legal research, this tools are inadequate in interpreting human emotional nuances, making them insufficient to replace human judgment. Putra et al (2023) and Xu et al (2022) explained that although the idea of entirely substituting human lawyers and judges with AI has raised unprecedented challenges and questions, this is still a long way off because humans are needed to understand some human attributes and psychological aspects, as well as the nuances, exceptions, circumstances, or complexity of the legal context, which often go beyond algorithms and datasets to make predictions or perform tasks. As a result, being the most effective when used in conjunction with human skills, it is anticipated that in the near future, AI will assist humans in legal-related work rather than replace them.

The usefulness of AI technology for legal practitioners was also highlighted in terms of its applications in document writing and scanning, electronic file management, and identifying and processing relevant and up-to-date specialist information with incredible speed and accuracy (Xu et al, 2022). Therefore, because of AI tools, legal professionals can perform their tasks faster and more effectively by eliminating uncertainties, reducing time delays, and performing repetitive tasks that consume time and resources. They can focus their activities on research, development, and contextualization. They will also have more time and patience to counsel their clients and to improve their professional work and personal life. In recent times, particularly during the COVID-19 outbreak and in the post-pandemic phase, the use of digital legal tools has experienced significant practical implementation and expansion. Saxena (2025) points out the possibility of expanding judicial channels, exemplifying the resolution of various disputes at the court level by using online e-court technology.

AI integration and advances in legal structures represent a real challenge because, on the one hand, numerous advantages are mentioned that it brings, but on the other hand, it also raises ethical concerns, which led some scholars to weigh the risks and benefits of using AI tools for legal professionals and clients. According to Putra et al (2023), these technologies require ongoing assessment and oversight to guarantee their ethical, equitable, and advantageous applications in society. Therefore, it is essential for any country to establish and constantly update a framework to guarantee the fair, transparent, and ethical application of modern technologies, with a focus on justice and human rights (Kreps et al, 2023; Putra et al, 2023).

The European Union has taken significant steps in this direction by adopting the Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 on AI, the first supranational legal framework regulating AI, and which classifies AI systems based on their level of risk: unacceptable, high, limited and minimal. AI systems used in justice are classified in the high-risk category, resulting in rigorous duties for both suppliers and users (Official Journal of the European Union, 2024). Regarding Romania and Latvia, in both countries, there are significant local concerns and initiatives about the use of AI in the legal field. The distinction between the two countries is related to the priority area and the efforts undertaken. In Romania, experts in the field focus more on legislative regulations. For example, the Romanian Senate is currently working on a measure which regulates the responsible use of AI by prohibiting the use of AI judgments without human interaction, particularly in the legal field and public security applications. Latvia is focusing more on implementing AI in collaboration with academia and dedicated organizations. In a comparative analysis, the situation in the two Eastern European countries is not very different in terms of the level of use of AI tools by lawyers. In Latvia, legal professionals have access to the dedicated LEXU AI platform, which offers them a smooth experience with the advantage of substantially reducing the time and effort required for legal research. LEXU AI is also the first Baltic solution of its kind to revolutionize legal research by developing capabilities based on AI. There are also efforts in academia in this regard, with the University of Latvia, through its Faculty of Law, involved in the further development of this platform. In Romania, the first AI virtual assistant dedicated to Romanian legislation—Lawren.ai—was launched in 2024 by law firm Buju Stanciu & Asociații. It provides complex legal information interpreted clearly and quickly. There are also emerging platforms—NewLaw.ro—that use AI tools for collaboration between clients and lawyers, contributing to the adoption of modern AI solutions.

However, the integration and use of AI in the practice of law, as well as in various other fields, are related to the perception that potential users are aware of the benefits and their willingness to be prepared and learn how to integrate these applications into their actual activities. Considering these challenges, some research has focused on identifying the factors that influence the willingness to implement new technology systems. According to Cronan et al (2018), individuals’ behaviors are mostly influenced by their intentions and will. However, there were also opinions that perceived utility and device simplicity are not applicable to adoption intention (Lu et al, 2019). The argument is that these factors are related to user learning of new AI technologies. Therefore, preparing users to adopt AI technology is important, and from this perspective, research in this field provides interesting results through established links with factors that contribute to people’s perception of AI technologies. In his study, Parasuraman (2000) identified four components that are involved in the readiness to use technology and reflect people’s willingness to embrace the adoption of new technologies: innovativeness, optimism, discomfort, and insecurity. Among them, optimism and innovativeness are considered positive factors that stimulate the appetite for technology and inspire potential users to have a favorable attitude and adopt new and innovative technology. The other two, discomfort and insecurity, are interpreted as factors that inhibit people and contribute to a decrease in their intent to adopt innovative technology.

Optimism reflects an individual’s positive attitude and expectations toward new technology, leading optimistic individuals to focus less on potential negative impacts and making them more likely to accept new technology. Optimism is understood as the tendency of individuals to perceive technology as a beneficial tool that may provide people more efficiency, flexibility, and control in their professional activities (Parasuraman, 2000; Rojas-Méndez et al, 2017). Therefore, when a person has a positive attitude toward the use of technology, having the belief that its development and adoption will have a favorable consequence, it may be concluded that the person is optimistic and has a desire to accept and use the technology (Wu and Lim, 2024). Such people are more dynamic and willing than their peers to embrace new technologies in their daily lives (Ali et al, 2019; Trifan and Pantea, 2023). According to Walczuch and Streukens (2007) and Ali et al (2019), optimism is a characteristic of individuals who expect positive outcomes rather than negative ones. Optimists are generally more adaptable and open to change, perceiving innovations not as threats but as opportunities for development. In legal structures, where tradition and caution prevail, these positive attitudes and beliefs are particularly relevant in the context of the introduction of new and innovative technology.

In their studies, Trifan and Pantea (2023) and Walczuch and Streukens (2007) point out the significant effect of optimism in attitudes that impact and contribute to technology adoption. Similarly, in a multiple case study on AI adoption in professional services businesses, Yang et al (2024) found that positive perceptions of AI’s capacity to improve productivity and decision quality were significant key motivational factors. Furthermore, the belief that AI can support rather than replace human judgment was associated with increased participation in adoption initiatives.

In the legal field, optimism can reduce common concerns about new technology. Legal practitioners that have a positive attitude toward the use of technology are more likely to perceive AI as an additional tool to their own knowledge and expertise, thus demonstrating a greater willingness to integrate AI into their field of work. According to Yang et al (2024), this optimistic attitude is also in line with contemporary organizational trends concerning innovation and digital transformation. We anticipate that legal practitioners who exhibit high levels of optimism will also be more open to adopt AI technologies, perceiving them as tools that may enhance efficiency and professional autonomy. Therefore, we make the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). An optimistic perception is positively related to readiness for AI adoption and application in the legal field.

According to previous research, innovativeness is the extent to which a person is driven to actively participate in digital transformation processes, is open to new concepts, and is prepared for new and innovative technologies (Parasuraman and Colby, 2015). Such innovative professionals often act as early adopters, getting involved in testing, improving, and promoting new technologies within their organizations (Wu and Lim, 2024). According to earlier study, it is the willingness to change, an open mind, or the ability to be creative (Ali et al, 2019). In relation to the use of AI technology, Trifan and Pantea (2023) describe innovativeness as open-mindedness, openness to novelty, willingness to change, creativity, and openness in information processing. Parasuraman and Colby (2015) explain this position by highlighting a favorable perception of its utility. In their study on the adoption of AI in professional services firms, Yang et al (2024) found that employees with a high level of personal innovativeness played a central role in the processes of experimentation and internal promotion of AI technology. By taking steps like investigating AI applications for document classification or assisting with legal research, they distinguished themselves and actively influenced management and colleagues to adopt them more widely.

In the legal field, professionals who are less open to innovation may be resistant to the uncertainties associated with AI tools, perceiving them as incompatible with traditional professional values. In contrast, innovative people are more likely to approach these new technologies with curiosity and initiative, even in the absence of clear regulatory frameworks or institutional precedents. Their openness to new technologies allows them to adapt more quickly and creatively to changes in the professional environment (Yang et al, 2024). Given the previous discussion, this study hypothesizes that legal professionals who exhibit a high level of personal innovation will be more willing to adopt new and innovative AI technologies, perceiving their integration as a natural extension of their capacity for adaptation and professional creativity. Therefore, this study introduces the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). An innovative attitude is positively related to readiness for AI adoption and application in the legal field.

Generally, people understand insecurity as a lack of self-confidence and uncertainty about their own ability to handle certain situations. Insecurity can be experienced in several areas of a person’s life and is a source of anxiety, difficulties in making quick decisions, and difficulty in performing in one area or another. Distrust in one’s own user skills and fear of technology, accompanied by fear of negative technological consequences and a desire for safety, creates a combination of factors that generate a reluctant attitude toward adopting technology (Wu and Lim, 2024). In their work, Parasuraman and Colby (2015) define insecurity as the level of skepticism or anxiety that individuals feel in relation to the effective use of new technologies. People characterized by a high level of insecurity tend to show confidence in their digital skills and often distrust the safety, reliability, or ethical neutrality of systems based on artificial intelligence (Munoko et al, 2020). In professions with a high degree of responsibility, such as law, these psychological barriers are amplified by fears of losing control, exposing clients to risk, or generating erroneous automated results.

Rahman et al (2017) reported that the more insecure people feel, the less likely they are to adopt new technologies. The study by Kim et al (2025) identifies insecurity as one of the main inhibiting factors of AI in the legal field. The authors highlighted lack of trust, algorithmic opacity, and ambiguity of legal liability as significant obstacles to AI integration, especially among practitioners who already experience anxiety related to the use of the technology. Similarly, empirical research focusing on ethical perceptions of AI among professionals and policymakers, found that lawyers with low confidence in their own technological competences tend to perceive AI as unethical, unsafe, or poorly regulated (Khan et al, 2023). These data suggest that insecurity functions not only as a psychological barrier but also as an ethical filter that influences how AI is perceived—either as a resource or a risk. Given that insecurity reduces openness to training, discourages experimentation, and intensifies fear of negative outcomes, we hypothesize that legal professionals who exhibit high levels of insecurity will have a reduced willingness to adopt AI-based tools. Thus, we propose the third research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). An insecure perception negatively affects readiness for AI adoption and application in the legal field.

Discomfort is the emotional and cognitive strain that people experience when they are overwhelmed by technical complexity or are compelled to use tools they do not completely understand (Parasuraman and Colby, 2015). In their study, Wu and Lim (2024) explain discomfort as a feeling a lack of competence in handling a new technology that may especially lead individuals to reject adopting them. Unlike insecurity, which refers to a perceived lack of competence or confidence, discomfort is a reaction manifested through anxiety, avoidance, or stress in the face of digital systems perceived as difficult to master. According to Tsikriktsis (2024), the degree of discomfort experienced by the exposed person is nothing more than a phobia they have towards using technology. Trifan and Pantea (2023) support the idea that, in a state of technological discomfort, people distance themselves from technology and innovation. Therefore, discomfort can negatively influence its adoption and application.

In the legal profession, where precision, control, and accountability are essential, discomfort can significantly reduce openness to AI new and innovative technologies adoption. According to Kim et al (2025), the opacity, unpredictability, and self-adaptive character of AI systems cause psychological discomfort among professionals in the field, especially when the functioning of these systems cannot be explained or justified in traditional legal terms. This emotional state often translates into avoidance of training, resistance to pilot initiatives, or lack of active involvement in implementation processes. Furthermore, Khan et al (2023) found that legal practitioners who encounter ethical uncertainty or ambiguity about the function of AI are extremely uncomfortable with automated legal reasoning. The complexity of developing technologies, the rapid speed of technical development, and institutional pressure to adapt all contribute to the discomfort. As a result, discomfort becomes a significant affective barrier to adopting new and innovative technologies, not because innovation is rejected outright, but because users feel intellectually and emotionally unprepared. In a field of law, where reputational and procedural concerns are high, this state can hinder even the best-intentioned digital transformation attempts. As a result, legal professionals who experience high levels of discomfort with technology may be may be less likely to accept or adopt it. Considering these discussions, we propose the last hypothesis of the present research:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). An uncomfortable perception negatively affects readiness for AI adoption and application in the legal field.

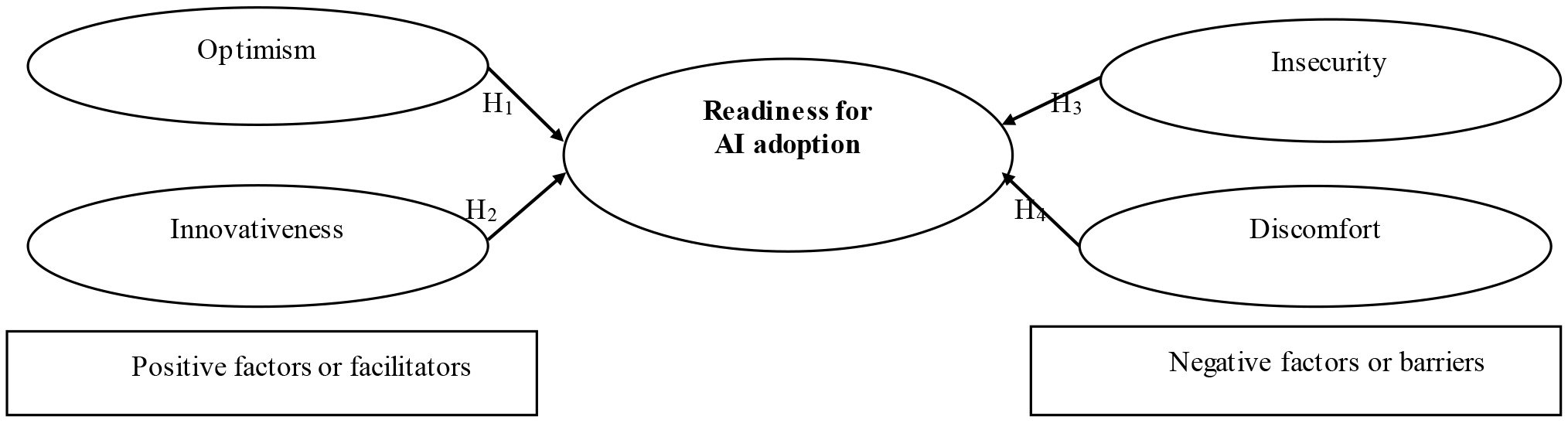

The conceptual framework of the study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Proposed conceptual framework. Source: Prepared by the authors.

In this study, a quantitative research methodology was employed based on a questionnaire distributed online and applied in two different countries, Romania and Latvia. The research questionnaire was developed by the research team on the Google Forms platform and then distributed to the study’s target group from both countries using an online survey link sent via email and social media. The reason for choosing the Google Forms platform was to make our questionnaire easier for respondents to fill it out, to receive honest responses from respondents, to reduce implementation costs, and to facilitate rapid data processing. Compared to traditional methods such as face-to-face interviews or telephone interviews, the online survey format reduced social desirability bias, ensured anonymity, and increased the likelihood of obtaining honest responses. It also enabled respondents to complete the survey at their convenience and from any location, improving response rates.

Respondents from both countries were selected based on their characteristics in accordance with the purpose of this study. The study’s target participants consisted of individuals engaged in the legal profession, including paralegals, lawyers, prosecutors, judges, notaries, bailiffs, mediators, insolvency practitioners, and other individuals with professional legal training. To recruit respondents, each member of the research team contacted individuals with a legal profession to ask for their willingness and availability to participate in this research and to inform them about the study’s objective, the length of the questionnaire, and the types of questions used. Respondents with a legal profession took part as the target group on a voluntary basis and were assured that their data and responses would only be utilized for academic purposes and would remain confidential and anonymous. Table 1 displays the demographic statistics of respondents from both nations.

| Measure | Romania | Latvia | Overall sample | ||||

| N = 263 | N = 131 | N = 394 | |||||

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | ||

| Age group (in years) | 20–29 | 30 | 11.4 | 28 | 21.4 | 58 | 14.7 |

| 30–39 | 63 | 24.0 | 29 | 22.1 | 92 | 23.3 | |

| 40–49 | 107 | 40.6 | 27 | 20.6 | 134 | 34.0 | |

| over 50 | 63 | 24.0 | 47 | 35.9 | 110 | 28.0 | |

| Gender | Female | 168 | 63.9 | 95 | 72.5 | 263 | 66.7 |

| Male | 95 | 36.1 | 35 | 26.7 | 130 | 33.0 | |

| Not answer | - | - | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Legal profession | Paralegals | 44 | 16.7 | 33 | 25.2 | 77 | 19.5 |

| Lawyer | 107 | 40.6 | 29 | 22.1 | 136 | 34.5 | |

| Prosecutor | 17 | 6.5 | 2 | 1.5 | 19 | 4.8 | |

| Judge | 20 | 7.7 | 15 | 11.5 | 35 | 8.9 | |

| Notary | 35 | 13.3 | 12 | 9.2 | 47 | 11.9 | |

| Bailiff | 24 | 9.1 | 9 | 6.9 | 33 | 8.4 | |

| Mediator | 6 | 2.3 | 1 | 0.8 | 7 | 1.8 | |

| Insolvency practitioner | 5 | 1.9 | 4 | 3.1 | 9 | 2.3 | |

| Law related | 5 | 1.9 | 26 | 19.7 | 31 | 7.9 | |

| Professional experience (in years) | 18 | 6.8 | 29 | 22.1 | 47 | 11.9 | |

| 3–5 | 23 | 8.7 | 15 | 11.5 | 38 | 9.7 | |

| 6–10 | 33 | 12.5 | 13 | 9.9 | 46 | 11.7 | |

| 11–20 | 81 | 30.8 | 35 | 26.7 | 116 | 29.4 | |

| 108 | 41.1 | 39 | 29.8 | 147 | 37.3 | ||

Source: Prepared by the authors.

The statistics reported in Table 1 indicate that 394 respondents took part as the target group in this study. Hair et al (2019) recommend using at least 200 samples for PLS-SEM. Similarly, Kline (2023) suggests that a minimum of 100 observations is necessary for estimation of PLS-SEM, while 200 observations are required for reliable estimations. The survey participants comprised 263 individuals with a legal profession from Romania and 131 from Latvia. Regarding the age category of the participants, the majority of the Romanian sample (40.6%) was between 40 and 49 years old and the majority of the Latvian sample (35.9%) was over 50 years old. The representativeness of the respondents by gender category was similar between the two groups in the sense of a female majority (72.5% for Latvians and 63.9% for Romanians). At the professional level, most participants from Romania (40.6%) were lawyers, and in the Latvian sample, most (25.2%) worked as paralegals. Regarding the professional experience of the respondents, the sample of Romanians included 71.9% of respondents with professional experience between 11 and 20 years and over 20 years. Counterparts of Latvia accounted for 56.5%.

The questionnaire of this study was developed by the research team in English and translated into Romanian and Latvian. Before commencing the formal data collection process, a pre-testing procedure was conducted to eliminate some shortcomings. The questionnaire was sent to three respondents from each country. In accordance with the recommendations received, minor changes were made, with some questions being eliminated or revised with the aim of enhancing the problem design and making filling out and understanding the questionnaire easier. The research questionnaire was completed from November 2023 to January 2024 and lasted approximately 5 minutes. In total, 394 valid questionnaires were collected from both countries.

The questionnaire was divided into two parts. The demographic statistics of the respondents consisted of four questions with a single answer choice related to gender, age group, type of legal profession, and experience in this profession. The second part explores the attitudes and readiness of legal professionals regarding AI adoption and application in their professional fields. Attitude is reflected through the four independent variables optimism, innovativeness, discomfort, and insecurity. These variables reflect both positive and negative personality-based attitudes toward technology and serve as predictors of readiness. Readiness for AI adoption is the dependent variable of this study, reflecting an individual’s openness, preparedness, and psychological willingness to engage with AI technologies.

All 28 measurement items from the questionnaire (Table 2) were developed by the research team based on previous literature (Al-Sharafi et al, 2022; Buvár and Gáti, 2023; Parasuraman and Colby, 2015; Rinjany, 2020; Trifan and Pantea, 2023; Uren and Edwards, 2023) and revised in the context of this study’s purpose. Respondents rated the items on a 5-point Likert scale, where the answers with total agreement were worth 5 and the answers with total disagreement were worth 1.

| Construct name | Construct code | Items code | Description of items |

| Optimism | AI_OP. | AI_OP.1 | I believe that new and innovative technologies help people build stronger relationships because they can communicate more and faster, avoiding some ambiguities or delays. |

| AI_OP.2 | I believe that AI could help to eliminate repetitive activities and focus the activities of professionals on research, development, and contextualization. | ||

| AI_OP.3 | Because of AI tools, I will have more time to my personal life. | ||

| AI_OP.4 | I believe that AI will be able to have a growing significance in the legal profession by quickly identifying and processing relevant and up-to-date specialist information. | ||

| AI_OP.5 | Because of AI tools, I will perform my tasks faster and effectively. | ||

| Innovativeness | AI_IN. | AI_IN.1 | I stay informed about the most recent technology advancements in my field. |

| AI_IN.2 | I like the challenge that the rapid advancement of AI technology brings. | ||

| AI_IN.3 | I find AI technologies to be intellectually engaging. | ||

| AI_IN.4 | I find AI technologies to be problem-solving tools for users. | ||

| AI_IN.5 | I can understand and use new and innovative AI technologies in my profession without help from others. | ||

| Insecurity | AI_IS. | AI_IS.1 | I believe that technology can decrease the quality of human relationships by reducing inter-human interactions. |

| AI_IS.2 | Deficiency in empathy and profound understanding of some human characteristics and psychological aspects can be disadvantages of using AI in my profession. | ||

| AI_IS.3 | AI systems rely on algorithms and data sets to make predictions or perform tasks but cannot understand the nuances, exceptions, or complexities of the legal context. | ||

| AI_IS.4 | Whenever a process is automated, any errors made by that system need to be identified and corrected. | ||

| AI_IS.5 | By implementing the AI tools in my profession, I fear that I will feel alone/isolated. | ||

| AI_IS.6 | The exponential advancement of technology could negatively affect my way of life. | ||

| Discomfort | AI_DS. | AI_DS.1 | Sometimes, I think that new and innovative technological systems are not designed to be used by people without proper training. |

| AI_DS.2 | AI applications adoption by the legal practitioners requires the development of legal-digital skills. | ||

| AI_DS.3 | Whenever a process is automated, additional work time is required because the correctness of the result obtained is not guaranteed, and without human intervention, errors can occur. | ||

| AI_DS.4 | A cautious implementation of AI by the legal practitioners is necessary because new and innovative technologies are not reliable. | ||

| AI_DS.5 | If I provide certain information to a system, I cannot be sure if I am doing it correctly or not due to the risks associated with the exchange of information. | ||

| AI_DS.6 | Prudent replacement of essential human tasks with automated ones is required. | ||

| AI_DS.7 | Adaptability and continuous learning are of fundamental importance in the context of the advancement of modern technologies. | ||

| AI_DS.8 | The implementation of AI in everyday work requires additional resources. | ||

| Readiness for AI | AI_RD. | AI_RD.1 | I have relevant knowledge to use AI innovative technologies in my profession. |

| AI_RD.2 | I am up to date with the latest technological developments and am willing to advise others on the same. | ||

| AI_RD.3 | I feel prepared for the implementation of AI applications in my profession. | ||

| AI_RD.4 | I like the challenge of the implementation of AI technologies in my profession. |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

AI, artificial intelligence; OP, Optimism; IN, Innovativeness; IS, Insecurity; DS, Discomfort; RD, Readiness.

In this study, the researchers used PLS-SEM as the statistical tool to evaluate the proposed research hypotheses. The PLS-SEM is a rising trend in analytical methodology (Hair and Alamer, 2022), and the use of PLS-SEM provided several methodological advantages over other statistical techniques. Hair et al (2019) recommend the use of PLS-SEM due to its applicability in handling complex models with heterogeneous relationships and its ability to perform efficiently in relatively small samples and non-normal data distributions. The analysis was conducted using Smart PLS 4 (version 4.0, SmartPLS GmbH, Bönningstedt, Germany) , a widely recognized and user-friendly software for PLS-SEM modeling. In the first part of the data analysis, reliability and validity were tested. In the second part, the hypothetical relationships between the constructs were examined for Romania and Latvia and for both countries combined.

Table 3 presents the reliability and convergent validity results. Considering

the recommended acceptable value for item loading (Hair and Alamer, 2022), we

removed one item from the Discomfort construct (AI_DS.6) in the Romanian sample;

in the overall sample we removed one item from the Discomfort construct

(AI_DS.8) and one item from the Insecurity construct (AI_IS.1) because the

value was not satisfactory. The internal reliability of the research constructs

was investigated using composite reliability (CR). The values for this

indicator exceed the recommended value of 0,70 in all three cases. In addition,

the values of Cronbach’s alpha (

| Constructs | Items | Loading | CR | AVE | |

| Romania | |||||

| AI_DS. | AI_DS.1 | 0.774 | 0.851 | 0.889 | 0.539 |

| AI_DS.2 | 0.793 | ||||

| AI_DS.3 | 0.880 | ||||

| AI_DS.4 | 0.701 | ||||

| AI_DS.5 | 0.790 | ||||

| AI_DS.7 | 0.565 | ||||

| AI_DS.8 | 0.579 | ||||

| AI_IN. | AI_IN.1 | 0.810 | 0.886 | 0.916 | 0.687 |

| AI_IN.2 | 0.839 | ||||

| AI_IN.3 | 0.866 | ||||

| AI_IN.4 | 0.854 | ||||

| AI_IN.5 | 0.773 | ||||

| AI_IS. | AI_IS.1 | 0.773 | 0.848 | 0.888 | 0.570 |

| AI_IS.2 | 0.799 | ||||

| AI_IS.3 | 0.838 | ||||

| AI_IS.4 | 0.723 | ||||

| AI_IS.5 | 0.740 | ||||

| AI_IS.6 | 0.642 | ||||

| AI_OP. | AI_OP.1 | 0.852 | 0.915 | 0.937 | 0.747 |

| AI_OP.2 | 0.911 | ||||

| AI_OP.3 | 0.892 | ||||

| AI_OP.4 | 0.814 | ||||

| AI_OP.5 | 0.849 | ||||

| AI_RD. | AI_RD.1 | 0.888 | 0.956 | 0.968 | 0.885 |

| AI_RD.2 | 0.950 | ||||

| AI_RD.3 | 0.962 | ||||

| AI_RD.4 | 0.960 | ||||

| Latvia | |||||

| AI_DS. | AI_DS.1 | 0.763 | 0.843 | 0.881 | 0.491 |

| AI_DS.2 | 0.790 | ||||

| AI_DS.3 | 0.871 | ||||

| AI_DS.4 | 0.688 | ||||

| AI_DS.5 | 0.785 | ||||

| AI_DS.6 | 0.453 | ||||

| AI_DS.7 | 0.578 | ||||

| AI_DS.8 | 0.576 | ||||

| AI_IN. | AI_IN.1 | 0.810 | 0.886 | 0.916 | 0.687 |

| AI_IN.2 | 0.839 | ||||

| AI_IN.3 | 0.866 | ||||

| AI_IN.4 | 0.854 | ||||

| AI_IN.5 | 0.773 | ||||

| AI_IS. | AI_IS.1 | 0.773 | 0.848 | 0.888 | 0.570 |

| AI_IS.2 | 0.799 | ||||

| AI_IS.3 | 0.838 | ||||

| AI_IS.4 | 0.723 | ||||

| AI_IS.5 | 0.740 | ||||

| AI_IS.6 | 0.642 | ||||

| AI_OP. | AI_OP.1 | 0.852 | 0.915 | 0.937 | 0.747 |

| AI_OP.2 | 0.911 | ||||

| AI_OP.3 | 0.892 | ||||

| AI_OP.4 | 0.814 | ||||

| AI_OP.5 | 0.849 | ||||

| AI_RD. | AI_RD.1 | 0.888 | 0.956 | 0.968 | 0.885 |

| AI_RD.2 | 0.950 | ||||

| AI_RD.3 | 0.962 | ||||

| AI_RD.4 | 0.960 | ||||

| Overall sample | |||||

| AI_DS. | AI_DS.1 | 0.857 | 0.949 | 0.958 | 0.765 |

| AI_DS.2 | 0.780 | ||||

| AI_DS.3 | 0.840 | ||||

| AI_DS.4 | 0.904 | ||||

| AI_DS.5 | 0.902 | ||||

| AI_DS.6 | 0.913 | ||||

| AI_DS.7 | 0.918 | ||||

| AI_IN. | AI_IN.1 | 0.973 | 0.966 | 0.972 | 0.875 |

| AI_IN.2 | 0.949 | ||||

| AI_IN.3 | 0.922 | ||||

| AI_IN.4 | 0.968 | ||||

| AI_IN.5 | 0.860 | ||||

| AI_IS. | AI_IS.2 | 0.747 | 0.824 | 0.877 | 0.588 |

| AI_IS.3 | 0.823 | ||||

| AI_IS.4 | 0.766 | ||||

| AI_IS.5 | 0.795 | ||||

| AI_IS.6 | 0.698 | ||||

| AI_OP. | AI_OP.1 | 0.876 | 0.953 | 0.963 | 0.839 |

| AI_OP.2 | 0.904 | ||||

| AI_OP.3 | 0.945 | ||||

| AI_OP.4 | 0.923 | ||||

| AI_OP.5 | 0.930 | ||||

| AI_RD. | AI_RD.1 | 0.940 | 0.954 | 0.967 | 0.879 |

| AI_RD.2 | 0.925 | ||||

| AI_RD.3 | 0.943 | ||||

| AI_RD.4 | 0.942 | ||||

Source: Prepared by the authors.

CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance extracted.

Regarding the average variance extracted (AVE), the values are greater than 0.5 threshold, with one exception in the Latvian sample where the value of AVE for the AI_DS construct is 0.491. According to the specific literature (Hair et al, 2017; Huang et al, 2013), construct convergent validity is still adequate if the value of the indicator AVE is less than 0.50, but the value of the indicator CR exceeds the minimum acceptable level of 0.60. In our Latvian sample, the value of CR for the AI_DS construct was 0.881, which exceeded the recommended threshold (0.6).

Next, the discriminant validity of the research construct was examined by applying the Fornell-Larcker criterion and the Hetertrait-Monotrait (HTMT) criterion. The findings of the Fornell-Larcker test are presented in Table 4 and are in line with the specific requirements of the literature (Hair et al, 2017), respectively, the values on the bold diagonal are higher than the correlation values of the research constructs.

| Romania | |||||

| Construct | AI_DS. | AI_IN. | AI_IS. | AI_OP. | AI_RD. |

| AI_DS. | 0.734 | ||||

| AI_IN. | –0.457 | 0.829 | |||

| AI_IS. | 0.514 | –0.453 | 0.755 | ||

| AI_OP. | –0.259 | 0.377 | –0.280 | 0.864 | |

| AI_RD. | –0.738 | 0.676 | –0.618 | 0.438 | 0.941 |

| Latvia | |||||

| Construct | AI_DS. | AI_IN. | AI_IS. | AI_OP. | AI_RD. |

| AI_DS. | 0.701 | ||||

| AI_IN. | –0.470 | 0.829 | |||

| AI_IS. | 0.520 | –0.453 | 0.755 | ||

| AI_OP. | –0.250 | 0.377 | –0.280 | 0.864 | |

| AI_RD. | –0.746 | 0.676 | –0.618 | 0.438 | 0.941 |

| Overall sample | |||||

| Construct | AI_DS. | AI_IN. | AI_IS. | AI_OP. | AI_RD. |

| AI_DS. | 0.875 | ||||

| AI_IN. | 0.295 | 0.935 | |||

| AI_IS. | 1.470 | –0.126 | 0.767 | ||

| AI_OP. | –0.005 | 0.688 | –0.070 | 0.916 | |

| AI_RD. | –0.875 | –0.095 | –0.161 | 0.259 | 0.938 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

According to Table 5, the results of the HTMT technique are lower than the recommended cut-off value of 0.85 (Hair et al, 2017; Hair and Alamer, 2022; Henseler et al, 2015), indicating discriminant validity.

| Romania | |||||

| Construct | AI_DS. | AI_IN. | AI_IS. | AI_OP. | AI_RD. |

| AI_DS. | - | ||||

| AI_IN. | 0.522 | - | |||

| AI_IS. | 0.596 | 0.517 | - | ||

| AI_OP. | 0.296 | 0.412 | 0.317 | - | |

| AI_RD. | 0.818 | 0.734 | 0.681 | 0.467 | - |

| Latvia | |||||

| Construct | AI_DS. | AI_IN. | AI_IS. | AI_OP. | AI_RD. |

| AI_DS. | - | ||||

| AI_IN. | 0.544 | - | |||

| AI_IS. | 0.607 | 0.517 | - | ||

| AI_OP. | 0.284 | 0.412 | 0.317 | - | |

| AI_RD. | 0.829 | 0.734 | 0.681 | 0.467 | - |

| Overall sample | |||||

| Construct | AI_DS. | AI_IN. | AI_IS. | AI_OP. | AI_RD. |

| AI_DS. | - | ||||

| AI_IN. | 0.286 | - | |||

| AI_IS. | 0.168 | 0.146 | - | ||

| AI_OP. | 0.145 | 0.738 | 0.080 | - | |

| AI_RD. | 0.811 | 0.080 | 0.179 | 0.256 | - |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Table 6 presents the results of the path analysis. To evaluate the hypothetical relationships between the constructs of this research, a Bootstrapping technique based on 5.000 interactions in Smart PLS 4 was used.

| Romania | ||||||

| Hypotheses | Paths | Path coefficient ( |

Standard deviation | t-value | p-value | Support |

| H1 | AI_OP. |

0.142 | 0.050 | 2.284 | 0.005 | Yes |

| H2 | AI_IN. |

0.327 | 0.088 | 3.698 | 0 | Yes |

| H3 | AI_IS. |

–0.199 | 0.068 | 2.904 | 0.004 | Yes |

| H4 | AI_DS. |

–0.451 | 0.068 | 6.666 | 0 | Yes |

| R2 | 0.739 | |||||

| Adj.R2 | 0.731 | |||||

| Latvia | ||||||

| Hypotheses | Paths | Path coefficient ( |

Standard deviation | t-value | p-value | Support |

| H1 | AI_OP. |

0.149 | 0.051 | 2.916 | 0.004 | Yes |

| H2 | AI_IN. |

0.316 | 0.081 | 3.922 | 0 | Yes |

| H3 | AI_IS. |

–0.194 | 0.069 | 2.797 | 0.005 | Yes |

| H4 | AI_DS. |

–0.459 | 0.066 | 6.979 | 0 | Yes |

| R2 | 0.742 | |||||

| Adj.R2 | 0.734 | |||||

| Overall sample | ||||||

| Hypotheses | Paths | Path coefficient ( |

Standard deviation | t-value | p-value | Support |

| H1 | AI_OP. |

0.416 | 0.047 | 8.843 | 0 | Yes |

| H2 | AI_IN. |

0.512 | 0.049 | 10.411 | 0 | Yes |

| H3 | AI_IS. |

–0.226 | 0.035 | 6.542 | 0 | Yes |

| H4 | AI_DS. |

–0.107 | 0.020 | 5.321 | 0 | Yes |

| R2 | 0.832 | |||||

| Adj.R2 | 0.829 | |||||

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Table 6 reveals that in the case of the Romanian sample, there is a significant

correlation between optimistic perception and readiness for AI adoption

and application (

This study, conducted in two Eastern European countries, Romania and Latvia, highlights the positive connection between the optimistic perspective expressed by legal professionals and their willingness to adopt new AI technologies in the legal environment. At the same time, research indicates that an optimistic mindset stimulates innovation and generates new opportunities for legal professionals to use AI tools effectively, enhance efficiency, and solve the new challenges they face.

According to prior research, individuals with an optimistic perspective are more dynamic and willing to embrace new technologies than their peers. They believe that new and innovative technologies provide them with the opportunity and power to progress more than ever before (Trifan and Pantea, 2023; Walczuch and Streukens, 2007). Therefore, because of AI tools, legal professionals can perform their tasks faster and more effectively by eliminating uncertainties, reducing time delays, and repetitive tasks that consume time and resources. Moreover, AI will aid legal professionals in identifying and analyzing relevant elements and up-to-date information, allowing them to concentrate their efforts on research, development, and contextualization. Thus, professionals in the legal field will perform their tasks faster and more effectively, and will have more time and patience to counsel their clients and improve their work and personal life.

Based on the study findings, individuals with a innovative attitude, embrace new ideas enjoy and understand the challenges posed by the rapid advancement of AI technology and stay updated on the latest technical advancements in their field. This result supports the views of several past studies that stated that individuals with an innovative mindset are early adopters because they embrace new technologies without hesitation and consider these technologies to be both mentally stimulating and problem-solving tools for users (Rahman et al, 2017; Trifan and Pantea, 2023).

The results show that individuals with an insecure perception of AI technologies have a reluctant attitude toward adopting AI technology, showing distrust in their own user skills and fear of technology, accompanied by fear of negative technological consequences and a desire for safety. Moreover, individuals with an insecure perception of AI technologies consider that AI can decrease the quality of human relationships by reducing inter-human interactions, which will negatively affect their life. Another argument is the absence of empathy and a profound understanding of some human attributes and psychological aspects because AI systems rely on algorithms and datasets to make predictions or perform tasks, but cannot understand the nuances, exceptions, or complexities of the legal context.

Additionally, our findings indicate that an uncomfortable perception negatively affects the readiness of legal professionals regarding the adoption and application of new and innovative technologies in their professional fields. These findings support previous research (Mukherjee and Hoyer, 2021; Popa et al, 2024; Trifan and Pantea, 2023) and highlight that new and innovative technological systems are not designed to be used without proper training. This finding suggests that the adoption of AI in the practice of law requires the development of digital skills. Therefore, AI implementation requires additional resources, adaptability, and continuous learning. Moreover, prudent replacement of essential human tasks with automated ones is required because, in an automated process, the correctness of the result obtained is not guaranteed, and without human intervention, errors can occur.

Grounded in technological readiness theory, our findings highlight that psychological readiness should be considered a key success factor in AI adoption initiatives. Leaders of the law profession, government legal bodies, and legal technology companies must invest in change management programs that foster legal professionals’ optimism, confidence, and receptivity to new and innovative technology. For example, developing personalized training programs and AI literacy workshops that demonstrate the technology’s practical utility can significantly reduce anxiety and resistance among legal professionals. The research findings suggest that AI adoption strategies in Eastern European legal systems need to be human-centered and sensitive to professional culture. Given that professionals with uncertain or uncomfortable perceptions are showing resistance to AI implementation, leaders of the law profession, government legal bodies, and legal technology companies should take a participatory approach by ensuring that legal professionals understand how AI complements, rather than replaces, their work. Mentoring methods could also be used, in which the professionals with innovative attitudes support their colleagues with more hesitant perceptions, thus encouraging a gradually transforming culture.

At the policy level, these findings have several implications for governments and regulators from the legal field and from the East European region. To foster a digital shift in the legal sector, Eastern European countries require national strategies that include incentives for AI implementation, legal and ethical guidelines to clarify AI’s role in decision-making, and public investments in legal professionals’ digital skills. It is important to note that ethical frameworks must also address fears about AI’s lack of empathy or its impact on human interaction, concerns that, if not addressed, could block adoption and undermine trust in AI-based systems.

Recent technological advances are one of the main and biggest challenges in contemporary society, leading to innovations and shifts that have often disrupted traditional norms in various aspects of human existence. Although these advancements are inevitable and have the potential to generate value in all aspects of life, different challenges and obstacles will inevitably arise. These challenges and barriers often come up because individuals fear the unknown, have a desire for safety, are concerned about their skills, or are concerned about the social and ethical impact of these new technologies. As humans are naturally adaptable creatures, they should adjust to, embrace, and benefit from technological advances in order to promote collective welfare.

To successfully manage the changes brought about by emerging technology and to ensure its ethical, fair, transparent, and beneficial integration and application, smooth transition is required by taking strategic steps through a careful approach, an open attitude toward innovation, and a continuous desire to learn. Considering these challenges, AI technology, used in the legal context, can be a tool and also a creative partner if legal professionals are willing to learn and adopt technology, to be open to novelty, and to utilize change management to manage the discomfort that may be set in.

The present study offers actionable implications for policymakers in developing AI literacy campaigns, skills development programs, and communication strategies to facilitate a smooth transition to AI-based practice as well as build community confidence through understanding AI capabilities and constraints. According to our findings, for the continued integration and advancement of AI in the legal profession and the practice of law, adaptability and continuous learning are of fundamental importance in the context of the unprecedented development of new technologies when some professional roles may move away from traditional skill sets. The results of this study suggest that the continued integration and advancement of AI in the legal profession and the practice of law require the development of legal-digital skills because legal practitioners need to know how to choose the right AI tool for a particular task, understand how it works, and evaluate the relevance, quality, and accuracy of the answers obtained using AI. Similarly, they must also be able to synthesize the overall results, identify any vulnerabilities, and ensure that the decisions made by AI are in line with the applicable legal and ethical regulations.

Because new legal-digital skills will be in high demand in this professional sphere, it is necessary for decision-makers to institute new training programs to enable legal practitioners to adapt to this new environment. From a practical point of view, decision-makers can develop tailored policies, interventions, and communication strategies to counsel and support those who do not have the proper mindset to embrace these new challenges. For instance, such knowledge can be disseminated through educational programs, conferences, and campaigns. Furthermore, law schools should update their curricula to develop proper skills and mindsets for future legal practitioners. Such focused strategies will ensure a smooth transition and continuous integration and application of AI in this occupational field.

In addition, by changing traditional legal practices, it is crucial to establish the trust of the entire community in the new system. The community needs a comprehensive understanding of the functionality of AI in the legal field as well as its capabilities and constraints. Although AI tools can enhance accessibility, efficiency, speed, and accuracy in legal services within traditional justice, the complete substitution of human lawyers and judges with AI remains distant because of the need for human understanding of various human attributes, psychological aspects, nuances, exceptions, circumstances, and legal complexities that surpass algorithms and data sets in making predictions or performing tasks. As a result, being the most effective when used in conjunction with human skills, it is anticipated that in the near future, AI will assist humans in legal-related work rather than replace them.

The present research makes few contributions. For instance, this research adds to the body of literature by strengthening the predictive power of individual psychological traits—innovativeness, optimism, discomfort, and insecurity—on legal professionals’ attitudes towards incorporating digital legal tools and AI in their profession. We thus contribute by highlighting how these psychological factors influence the degree of openness to technology in a specific professional field, the legal one, and within an Eastern European cultural and geographic area. This theoretical framework has not previously been utilized to assess readiness to incorporate digital legal tools and AI in the legal context, therefore our study offers a novel approach. At the present time, according to our knowledge, in the context of the fusion of AI technology and the field of justice, the literature available is limited. Existing literature on the adoption of AI and digital technologies focuses mainly on structural factors, such as digital infrastructure, digitalization policy, or the degree of technological literacy. Our study emphasizes the subjective dimension of professionals’ perceptions, emotions, and mindsets, an area still insufficiently explored, especially in a traditionally conservative field such as the legal one. The study’s findings indicate that the success of AI adoption depends not only by technological capabilities, but also by the socio-psychological framework in which such technologies are implemented. At the same time, our study responds to a gap in the literature regarding the regional and cultural realities of Eastern Europe regarding the implementation of AI in traditional professional sectors, such as the legal one. Region-specific cultural and historical factors have a significant effect on how AI is perceived and embraced by legal professionals, these aspects giving a distinctive character to the present research. The findings of this study are also relevant for policymakers in developing AI literacy campaigns, skills development programs, and communication strategies to facilitate a smooth transition to AI-based practice as well as building community confidence through understanding AI capabilities and constraints. In addition, no empirical research has utilized this approach and PLS-SEM to explore the attitudes and readiness of AI adoption and application in this field and within this Eastern European geographic area and cultural setting.

Future research can build on the proposed model and our research findings by using other geographical areas or world regions with different cultural contexts to integrate cultural facets into this research framework. Longitudinal study might show how the level of readiness varies over time as AI tools become more integrated into legal practice. In addition, generational differences should be considered in future studies. Future research should explore more variables or incorporate different research theories in the legal context to analyze the response of this professional field to the global boom of AI. In the future, researchers may opt for another data collection method. The use of interviews in future studies could offer valuable insights into this research topic.

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

VAT and AK conceived the study and were responsible for the design and development of the data analysis. VAT and AK were responsible for data collection and analysis. VAT and MS were responsible for data interpretation. VAT and MS were responsible for analysis validation. VAT wrote the first draft of the article. VAT, AK, and MS reviewed and edited the final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for the insightful comments to improve the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.