1 Department of Marketing, International Business and Economics, West University of Timișoara, 300115 Timișoara, Romania

Abstract

In today’s visually-driven marketplace, where social media and personal branding dictate consumer preferences, companies must strategically position themselves to align with evolving identity trends. This study provides managerial insights into the role of brand personality in shaping brand-consumer relationships, focusing on the impact of personality on trust, attachment, commitment, and customer satisfaction. This research employed a rigorous quantitative approach, including reliability analysis of measurement instruments, confirmatory factor analysis, and analysis of variance (ANOVA). Hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM) through path analysis, and the robustness of the estimates was assessed using the bootstrap procedure. The findings reveal the strategic importance of brand personality traits, demonstrating their influence across brand-consumer relationship dimensions. Furthermore, the study highlights the managerial implications of brand personality, offering a comparative assessment of personality profiles associated with global brands such as Zara, H&M, McDonald’s, and KFC. These insights enable brand managers to refine positioning strategies, optimize consumer engagement, and foster long-term brand equity.

Keywords

- brand personality

- personality congruence

- trust

- satisfaction

- brand loyalty

In an era shaped by visual culture, social media, and the rise of personal branding, consumer decision-making is no longer driven purely by functional attributes. Today’s customers actively seek brands that mirror and reinforce their self-identity, elevating brand personality to a central role in fostering engagement and loyalty (Maehle et al, 2011). Marketing research has increasingly focused on self-congruity as a key predictor of consumer behaviour (Kolańska-Stronka and Singh, 2024; Alabed et al, 2022). Brand personality congruence refers to the extent to which a brand’s image aligns with a consumer’s self-perception (Lee et al, 2020; Bargoni et al, 2024). When this congruity is high, consumers tend to form strong, personal connections with the brand, whereas low congruity often leads to discomfort and emotional detachment (Kumar and Kaushik, 2022). A recent study on consumer behavior, shows that individuals prefer brands whose personalities reflect their own (Venciute et al, 2023).

Over the past two decades, research has consistently validated the importance of brand personality and consumer-brand personality congruence in shaping customer preferences, satisfaction, and retention (Brakus et al, 2009; Sung and Kim, 2010; Shetty and Fitzsimmons, 2022; Park and Ahn, 2024), the study of brand personality being one of the most important research trends regarding the consumer brand relationships (Japutra and Molinillo, 2019; Bargoni et al, 2024).

From a managerial standpoint, aligning brand personality with consumer identity represents a core element of competitive strategy. Recent findings by Agyekum et al (2025) emphasize the influence of brand love and self-congruity as critical drivers of consumer behavior. Thus, marketing managers are encouraged to adopt data-driven segmentation and persona-based strategies, enabling more precise message tailoring and the cultivation of stronger brand-consumer relationships.

Asperin (2007) highlights a notable gap in the measurement of brand-consumer personality congruence. Existing literature tends to emphasize self-image congruence, often overlooking the more nuanced alignment between brand personality and consumer personality (Sirgy, 1982; Hosany and Martin, 2012; Sung and Huddleston, 2018). This conceptual limitation presents a strategic opportunity for brand managers, particularly in emerging markets, where consumer-brand relationship dynamics remain relatively underexplored. While some studies have examined these dynamics in some emerging markets such as Malaysia (Mohtar et al, 2019), India (Kumar et al, 2006), Brazil (Maciel et al, 2013), and Russia (Supphellen and Grønhaug, 2003), research focusing on consumers in South-Eastern European emerging markets is especially scarce (Milas and Mlačić, 2007; Marković et al, 2022).

Additionally, the study responds to a growing managerial imperative: understanding consumers beyond traditional demographic segmentation. By exploring how individuals internalize brand traits that reflect or complement their own personalities, managers are better positioned to personalize communication strategies, guide product development, and optimize loyalty initiatives. In an increasingly digital consumer landscape, the articulation of coherent and congruent brand personalities emerges as a strategic priority for organizations seeking to sustain competitive advantage.

Moreover, unlike most studies that use the original or modified Aaker’s (1997) brand personality scale, we tested a five-dimensional, 26-item scale adapted from Ferrandi and Valette-Florence’s reduced versions (2002a; 2002b) and Saucier’s (1994) mini-markers. Our methodology incorporates both positive and negative brand traits (including withdrawn, careless, harsh, temperamental, and moody) to provide a more comprehensive managerial tool for market analysis and brand positioning. Additionally, we have used four of Ferrandi and Valette-Florence’s dimensions, opting for Neuroticism (2002a) instead of Emotional Stability, recognizing its greater cultural relevance in South-Eastern European consumer behavior.

For brand executives, marketing strategists, and corporate decision-makers, these insights offer valuable opportunities in order to refine consumer segmentation models, optimize brand positioning, and develop high-impact loyalty programs.

Brand personality is a set of human characteristics associated to a brand (Aaker, 1997; Keller and Richey, 2006), shaped starting from the consumer’s experience or from any direct or indirect interaction with the brand (Keller, 1993; Aaker, 1997).

There are two primary brand personality theories (Radler, 2018; Oklevik et al, 2020; Ghorbani et al, 2022). Aaker’s approach considers brand personality as a set of humanlike characteristics, encompassing gender, profession, status, and traits (brand-as-a-person metaphor). The alternative theory, influenced by human personality psychology (Geuens et al, 2009), defines brand personality exclusively in terms of human traits (brand-as-a-personality definition).

Aaker’s scale has received numerous criticisms, mostly for its limited applicability in various industries and different cultural contexts (Rauschnabel et al, 2016).

The research in this field has also focused on the consequences of creating a positive and distinct personality for the brand. These studies (Sindhu et al, 2021; Sirgy, 1982), consider the personality of the brand and its congruence with the personality of the consumer as independent variables, while consumer satisfaction, trust, attachment, commitment, loyalty as dependent variables.

We consider personality a part of the self-concept, the latter including, as is the case with the brand’s identity and image, in addition to personality traits, other demographic, social, lifestyle characteristics too.

Consumers have strong preferences for brands perceived to possess personality traits that reflect their identity (Sirgy, 1982). The validity of consumer-brand relationships has been widely supported in the marketing literature (Louis and Lombart, 2010; Ramaseshan and Stein, 2014; Tong et al, 2018; Japutra and Molinillo, 2019; Cardoso et al, 2022; R. Valette-Florence and P. Valette-Florence, 2020; Shetty and Fitzsimmons, 2022).

Despite the extensive literature on brand personality and its psychological underpinnings, its integration into managerial decision-making remains underdeveloped. The relevance of brand personality for management is rooted in its potential to guide strategic decisions on brand communication, consumer targeting, and relationship marketing. By conceptualizing brand personality as a managerial asset, firms can design differentiated value propositions, personalize brand narratives, and optimize brand-customer alignment across diverse market segments. Thus, brand personality research contributes to the development of managerial capabilities related to brand equity management and consumer engagement.

Brand personality significantly affects key business outcomes like brand equity (Su and Tong, 2015) and customer loyalty (Sindhu et al, 2021), highlighting the need for managers to understand its drivers. While consumer personality traits are less controllable for managers, they are valuable for market segmentation. Branding strategies influence all dimensions of brand personality, but nuances matter (Wang et al, 2025). For instance, hedonic benefit appeals mainly strengthen perceptions of sophistication and ruggedness, making them more suitable for brands like Mercedes-Benz or Jeep, rather than sincerity-focused brands like Volvo.

From a strategic perspective, brand personality acts as a bridge between brand identity and consumer perception. Managers must constantly navigate between building a consistent identity and adapting to shifting consumer expectations. This dual challenge makes brand personality an essential strategic tool, one that can be managed, measured, and refined. Moreover, the incorporation of consumer-brand personality congruence into brand management strategies allows for data-informed segmentation and precision marketing, ultimately enhancing organizational responsiveness and consumer satisfaction.

Brakus et al (2009) demonstrated that brand personality enhances satisfaction by enabling self-expression. Similarly, Lee et al (2009) found in their study on various family restaurants that brand personality significantly shapes positive and negative emotions, serving as a predictor for satisfaction.

Su and Tong (2015) applied Aaker’s brand personality framework (1997) to study Denim jeans’ influence on consumer satisfaction and demonstrated diverse effects of brand personality dimensions on both consumer satisfaction and brand loyalty.

Marković et al’s (2022) study on Serbian consumers revealed a crucial role for brand personality in fostering customer satisfaction.

Previous research on store personality has shown that the store’s symbolic image significantly influences perceived differentiation, customer satisfaction, store patronage, and loyalty behavior (Willems, 2022).

Based on the above, we formulated the following hypothesis:

H1: Brand personality has a significant influence on consumer satisfaction.

Brand trust reflects consumers’ perception of three dimensions associated with a brand: credibility, integrity and goodwill (Gurviez and Korchia, 2002; Louis and Lombart, 2010).

Sung and Kim (2010) established that the brand’s personality dimensions’ effect on trust and emotions associated with the brand is different. Thus, ruggedness and sincerity have greater effects on trust than on emotions, and arousal and sophistication have a stronger influence on emotions than brand trust, while the effect of competence on trust and emotions is similar.

Japutra and Molinillo (2019) identified a positive relationship between the dimensions of responsibility, activity and trust in the brand. Responsibility included the down-to-earth, stable and responsible traits, and the activity dimension included dynamic, active, innovative features.

R. Valette-Florence and P. Valette-Florence (2020) analyzed 917 respondents to explore how the personalities of six brands, classified as either hedonic or utilitarian, relate to brand relationships. They found that brand personality directly impacts trust, attachment, and commitment, and indirectly influences commitment through trust.

A strong brand personality fosters emotional connections, enhances preference, evokes emotions, and boosts trust and loyalty (Tong et al, 2018).

Cardoso et al (2022) studied 124 Airbnb users, finding a significant link between brand personality and institutional trust. Sincerity, among the five personality dimensions (sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication, and ruggedness), had the greatest impact on trust.

Park and Ahn (2024) found that traditional brand personalities still convey strong trust and authenticity. Due to their proven reliability and historical depth, personality models better explain consumer preferences. However, in the context of artificial intelligence, when consumers are explicitly informed or become aware that an image is AI-generated, their trust in that image tends to decline (Lu et al, 2023).

Based on the above, we formulated the following hypothesis:

H2: Brand personality has a positive effect on brand trust.

In psychology, attachment corresponds to an emotionally charged connection between a person and an object (Malär et al, 2011), while in marketing it corresponds to the emotional connection between the consumer and the brand (Fournier, 1998; Louis and Lombart, 2010; Malär et al, 2011), the connection that links the consumer to a brand and involves feelings such as affection, passion and emotional connection.

Freling and Forbes (2005) showed that brands with a strong personality generate the emotional attachment that increases the chances of repurchasing them, extending the assortment range and the possibility of paying higher prices at purchase.

Brand personality explains 32.4% of brand attachment (Ambroise, 2006). Gouteron (2008) found that all dimensions of brand personality positively affect attachment, while Louis and Lombart (2010) identified only “friendly”, “original”, and “elegant” as influential. Ramaseshan and Stein (2014) also confirmed a significant positive link between brand personality and attachment.

Building on previous research, Shimul (2022) identified brand personality, brand trust, brand experience, and nostalgia as key antecedents of brand attachment.

Thus, we formulated the hypothesis:

H3: The personality of the brand directly and positively influences the attachment to the brand.

Commitment represents the attitudinal willingness to repurchase and frequent the brand, which is combined with a favorable attitude from the consumer (Fournier, 1998).

Ben Sliman et al (2005) found a positive impact of brand personality on retailer commitment. Louis and Lombart (2010) note that only “friendly” and “original” personality aspects positively affected commitment. Gouteron (2008) shows all personality dimensions influence the desire to continue with a brand, with sincerity, confidence, sensuality, and gentleness impacting resistance to brand change.

Tong et al (2018) validated the impact of the luxury fashion brands personality on trust and brand commitment on a sample of American consumers.

Some authors emphasize that while the brand personality-brand trust and trust-commitment relationships appear dominant in empirical studies, it is less certain whether brand personality directly influences brand commitment (R. Valette-Florence and P. Valette-Florence, 2020).

Considering the afore mentioned, we formulated the following hypothesis:

H4: Brand personality has a direct and positive influence on commitment.

Trust is a crucial element in fostering an emotional bond within the consumer-brand relationship, which can ultimately enhance brand satisfaction. For instance, Stribbell and Duangekanong (2022) demonstrated that brand trust significantly and positively influences customer satisfaction in the realm of international education services. Supporting this view, Diputra and Yasa (2021) found that trust plays a vital role in driving satisfaction among Samsung smartphone users in Indonesia. Likewise, Uzir et al (2021) highlighted the positive impact of trust on customer satisfaction in home delivery services, particularly within the context of online shopping during the COVID-19 pandemic.

H5: Brand trust influences consumer satisfaction.

In the field of consumer-brand relationships, research has shown that customers can develop a deep sense of love for their favorite brands, which in turn generates a range of positive outcomes—one of which is satisfaction (Wong, 2023). Building on this perspective, a systematic literature review by Shimul (2022) identified customer satisfaction as a direct outcome of brand attachment. Empirical studies further support this view: drawing on data from 1236 Apple and Samsung smartphone users, Vahdat et al (2020) found that emotional brand attachment has a significant positive impact on customer satisfaction, while Pabla and Soch (2023), in their analysis of airline passengers’ brand experiences, validated a similarly strong and significant influence of brand love on satisfaction. Similarly, Ferreira et al (2019) report that in a retail fashion context, brand love has positive effects on customer satisfaction.

H6: Brand attachment influences consumer satisfaction.

Amoroso et al (2018) investigated the extent to which brand commitment influences satisfaction, loyalty, and continuance intention among Japanese consumers using mobile wallet applications, finding a positive effect of commitment on satisfaction. This relationship was further supported by a more recent study. In their research, Amoroso and Ackaradejruangsri (2024) examined brand commitment and continuance intention in the context of mobile wallet applications in Japan. Comparing data over a five-year period, they identified brand commitment as a key antecedent to Japanese consumer satisfaction.

H7: Brand commitment influences consumer satisfaction.

A previous study suggests the idea that consumers prefer those products where there is a high degree of congruence between self-identity, their own perceived personality and the brands personality (Lin, 2010).

Mulyanegara et al (2009) confirmed that certain consumer personality traits strongly correlate with certain brand personality dimensions and that this correlation influences brand preferences. For example, conscientious consumers will prefer those products that have a personality characterized by performance and trust.

Park and Lee (2005) found that brand-self congruence boosts consumer satisfaction and directly increases loyalty, but only with strong involvement. In low-involvement cases, congruence influences loyalty indirectly through satisfaction.

Chang et al (2001) found that consumers tend to show differences in the assessments they make to brands, differences that are positive for a high ideal self-concept.

Yi and La (2002) found that brand personality influences brand identification, directly impacting loyalty and indirectly affecting satisfaction.

The consumer-brand congruence is considered a good predictor of satisfaction also in the studies by Sirgy et al (1997), Jamal and Goode (2001), Ekinci and Riley (2003), Venciute et al (2023), Pryor (2024), the authors considering either actual self-congruence or ideal self-congruence, or both.

Therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis:

H8: Actual self-congruence will have a positive impact on consumer satisfaction.

Empirical studies like Ekinci et al (2008) showed that ideal self-congruence significantly influences buying behavior, as consumers who see their ideal self in the company’s image are more likely to feel satisfied. Japutra et al (2018) also found that higher ideal self-congruence strengthens consumer attitudes, satisfaction, and perceived service quality, fulfilling needs for self-esteem and consistency.

Therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis:

H9: Ideal self-congruence will have a positive impact on consumer satisfaction with a brand.

Customer satisfaction, is widely seen as a major driver of customer retention. It results from comparing expectations with perceived performance and often leads to loyalty. Evidence shows higher satisfaction significantly boosts loyalty in service sectors (Chatzi et al, 2024; Tanford, 2016).

El-Adly (2019), in a study conducted on two sub-samples of hotel customers in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and abroad, examined the relationship between customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty in the hotel sector. The results showed that customer satisfaction had a direct positive impact on customer loyalty.

Hwang et al (2021) investigated the antecedents of customer loyalty in private and national brands within South Korea’s retail industry, finding that satisfaction has a direct and positive influence on loyalty for both brand categories. The direct and positive influence of satisfaction on future behavioral intentions has also been tested and validated in the French retail sector (Lombart and Louis, 2014).

Therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis:

H10: Consumer satisfaction will have a positive impact on brand loyalty.

Trust, attachment, and commitment are considered essential for successful long-term relationships (Garbarino and Johnson, 1999). This study tests whether brand personality is a relevant source for building cognitive and emotional links in consumer-brand relationships, where trust, attachment, and commitment act as interconnected stages, each influencing the next.

Choi et al (2024), based on previous studies, tested the hypothesis that brand trust positively affects consumers’ emotional attachment to the brand.

Building on previous research, Shimul (2022) identified brand personality, brand trust, brand experience, and nostalgia as key antecedents of brand attachment and consumers’ brand commitment, brand loyalty, (re)purchase intention, and positive word-of-mouth (WOM) intentions were the most frequently studied constructs as consequences.

In his review of the brand attachment literature, Shimul (2022) emphasized that brand attachment is a key antecedent of brand commitment. He also noted that brand attachment enhances consumer satisfaction (Belaid and Temessek Behi, 2011), which in turn drives (re)purchase intentions, and leads to brand loyalty.

Several authors have emphasized the role of trust in fostering brand attachment (e.g., Park et al, 2008; R. Valette-Florence and P. Valette-Florence, 2020). In turn, brand attachment has a significant positive impact on overall commitment, with the strength of this effect varying depending on whether the product’s perceived value is hedonic, functional, or utilitarian (R. Valette-Florence and P. Valette-Florence, 2020).

Consumers who develop an emotional bond with a brand attribute personal significance to it. As Wong (2023) noted, brand managers can boost commitment by cultivating brand love, and “dream”-themed integrated campaigns can spark emotions and strengthen attachment.

Ahmad and Thyagaraj (2015) found, on one hand, that brand personality influences both brand trust and brand attachment, and on the other hand, that brand trust has a significant impact on brand attachment, while brand attachment significantly influences brand commitment.

Based on the above, we formulated the following hypotheses:

H11: Brand trust has a positive influence on brand attachment;

H12: Brand attachment directly and positively influences brand commitment.

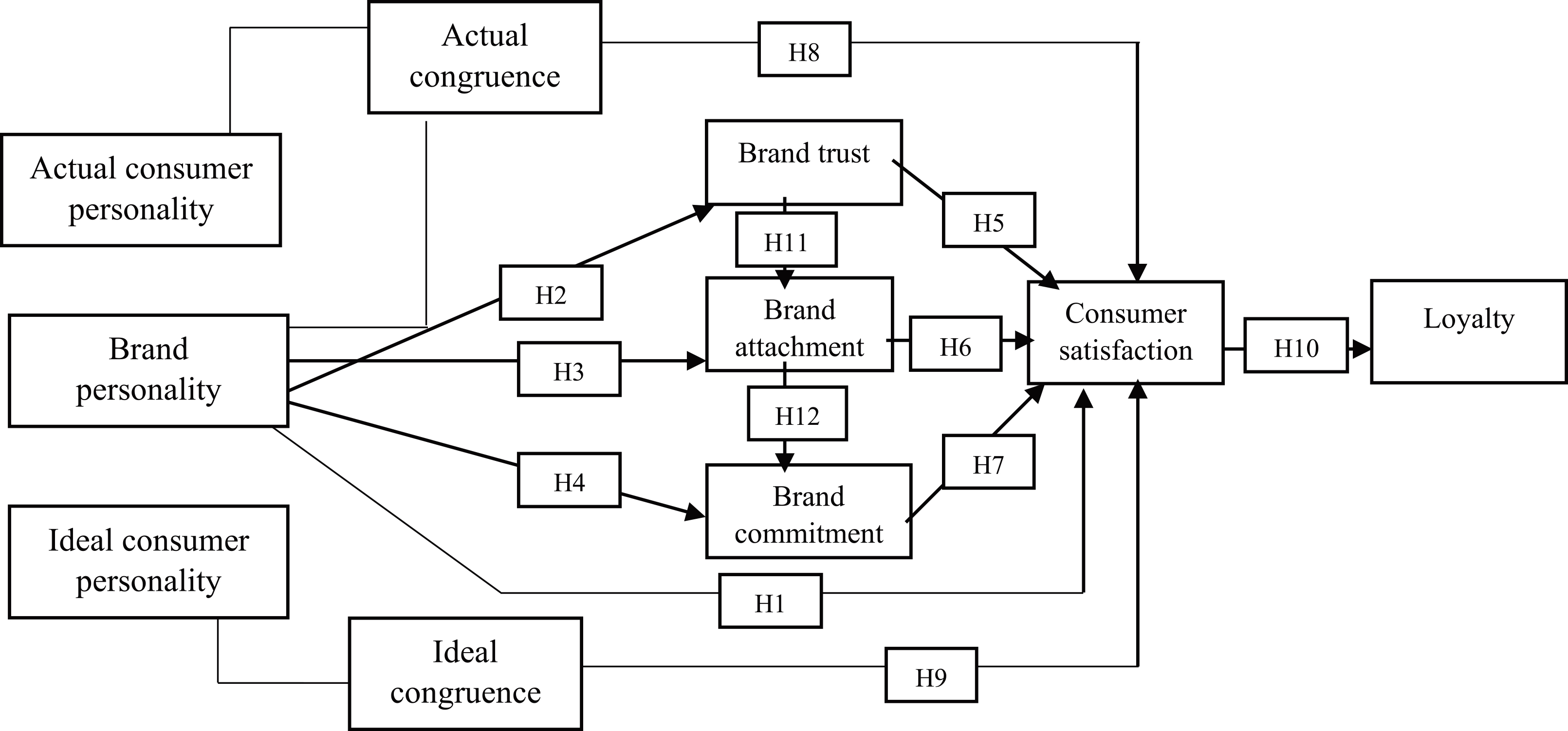

The research model proposed is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Research model proposed.

By examining brand personality through the lens of managerial outcomes, such as customer satisfaction, trust, and loyalty, this study positions brand personality as a critical input for brand strategy formulation. Our hypotheses not only test psychological congruence but also reflect managerial performance metrics. Accordingly, the theoretical framework aims to generate actionable insights for marketing managers, enabling data-driven decisions regarding consumer segmentation, emotional branding, and long-term customer relationship management.

In practical terms, each tested hypothesis provides a means for managers to evaluate the return on brand investments. For instance, understanding that brand personality affects direct brand trust, brand attachment and brand commitment, and indirect customer satisfaction (trust and attachment) helps managers prioritize messaging that aligns with aspirational consumer identities. Similarly, trust and attachment are central to customer lifetime value models and loyalty program success, making the tested relationships in this study directly relevant for marketing practitioners seeking sustainable growth.

The scales used to measure the constructs included in the proposed research

model are presented in Table 1, and the reliability and validity of these scales

are shown in Table 2. All scales used to measure the model’s

dimensions/constructs are reliable, with Cronbach’s

| Scale | Proposed and tested by | Type of scale |

| Brand personality | Adaptation after scales proposed by Ferrandi and Valette-Florence (2002a; 2002b), supplemented with items from the lexical scale of the human personality elaborated by Saucier (1994) | 5 point Likert scale |

| 5 dimensions and 26 items | ||

| Consumer personality | Adaptation after scales proposed by Ferrandi and Valette-Florence (2002a; 2002b), supplemented with items from the lexical scale of the human personality elaborated by Saucier (1994) | 5 point Likert scale |

| 5 dimensions and 26 items | ||

| Consumer satisfaction | Oliver (1980), Swinyard and Whitlark (1994), Plichon (1999) | 5 point Likert scale |

| 8 items | ||

| Trust in the brand | Gurviez and Korchia (2002) | Three-dimensional scale |

| 5 point Likert scale | ||

| 9 items | ||

| Brand attachment | Adaptation after Lacoeuilhe and Belaïd (2007) | 5 point Likert scale |

| 8 items | ||

| Brand commitment | Adaptation after Fullerton (2005) | 5 point Likert scale |

| 7 items | ||

| Brand loyalty | Adaptation after Zeithaml et al (1996), with three items | 5 point Likert scale |

| 3 items |

| Scale | CR | AVE | KMO | Bartlett test | |

| CONS_PERS_RE | 0.623 | 0.851 | 0.641 | 0.693 | 134.967 (0.000) |

| CONS_PERS_ID | 0.758 | 0.905 | 0.724 | 0.745 | 284.998 (0.000) |

| BRAND_PERS | 0.760 | 0.904 | 0.723 | 0.761 | 318.637 (0.000) |

| CONG_RE | 0.557 | 0.832 | 0.654 | 0.659 | 67.795 (0.000) |

| CONG_ID | 0.721 | 0.892 | 0.736 | 0.744 | 160.830 (0.000) |

| SATIS | 0.885 | 0.945 | 0.743 | 0.860 | 867.998 (0.000) |

| TRUST | 0.823 | 0.916 | 0.669 | 0.706 | 841.384 (0.000) |

| ATACH | 0.887 | 0.951 | 0.782 | 0.883 | 793.441 (0.000) |

| COMITT | 0.904 | 0.957 | 0.798 | 0.901 | 906.138 (0.000) |

| LOYAL | 0.770 | 0.877 | 0.703 | 0.705 | 186.822 (0.000) |

CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance extracted; KMO, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin; CONS_PERS_RE, actual consumer personality; CONS_PERS_ID, ideal consumer personality; BRAND_PERS, brand personality; CONG_RE, actual congruence; CONG_ID, ideal congruence; SATIS, consumer satisfaction; TRUST, brand trust; ATACH, brand attachment; COMITT, brand commitment; LOYAL, loyalty.

The significance level for the Bartlett sphericity test for all dimensions/constructs is 0.000 (less than 0.05), and all dimensions/constructs have a high level of convergent validity. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) indicators for all dimensions/constructs within the research model exceed 0.500, indicating statistically significant correlations among the items within each dimension/construct. These correlations demonstrate sufficient strength to support the application of factor analysis, and all factor loadings had values greater than 0.400 (Field, 2009). Furthermore, average variance extracted (AVE) indicator values surpass the threshold of 0.500, and composite reliability values exceed 0.700, as recommended by Fornell and Larcker (1981). Consequently, all dimensions/constructs exhibit a high level of convergent validity, as detailed in Table 2.

In Table 3 we can see that the ten constructs within the proposed conceptual model have a high level of discriminant validity. The values of the AVE indicator for each construct are higher than the squared correlations between each construct and all other constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| CONS_PERS_RE | 0.641 | |||||||||

| CONS_PERS_ID | 0.362** (0.131) | 0.724 | ||||||||

| BRAND_PERS | 0.267** (0.071) | 0.252** (0.064) | 0.723 | |||||||

| CONG_RE | –0.479** (0.229) | –0.048 (0.002) | –0.007 (0.000) | 0.654 | ||||||

| CONG_ID | –0.263** (0.069) | –0.023 (0.001) | –0.788** (0.621) | 0.216** (0.047) | 0.736 | |||||

| SATIS | 0.072 (0.005) | 0.081 (0.007) | 0.204** (0.042) | –0.023 (0.001) | –0.180** (0.032) | 0.743 | ||||

| TRUST | 0.175** (0.030) | 0.169* (0.029) | 0.309** (0.095) | –0.062 (0.004) | –0.291** (0.085) | 0.449** (0.202) | 0.669 | |||

| ATACH | 0.134* (0.018) | 0.190** (0.036) | 0.323** (0.104) | 0.005 (0.000) | –0.250** (0.063) | 0.449** (0.202) | 0.632** (0.399) | 0.782 | ||

| COMITT | 0.100 (0.010) | 0.171* (0.029) | 0.334** (0.112) | 0.009 (0.000) | –0.213** (0.045) | 0.340** (0.116) | 0.536** (0.287) | 0.790** (0.624) | 0.792 | |

| LOYAL | 0.079 (0.006) | 0.028 (0.001) | 0.011 (0.000) | –0.019 (0.000) | –0.063 (0.004) | 0.167* (0.028) | 0.105 (0.011) | 0.036 (0.001) | –0.005 (0.000) | 0.703 |

Note: **, Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). *, Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

AVE on the diagonal; square of correlation (in parenthesis) and correlation appear below the diagonal.

Similar to Wallace et al (2017), we applied the absolute difference theory to create the items for actual congruence (CONG_RE) and ideal congruence (CONG_ID) constructs. Actual/ideal personality congruence scores were operationalized as the absolute difference score between preferred brand personality scores and respondents actual/ideal personality scores for each personality facet (belonging items). Further, average scores were determined on the n = 26 personality facets, afterwards the index was multiplied by –1, so that larger values would indicate higher real or ideal congruence.

The research was conducted on a sample of 216 Romanian respondents. The sample consists of 119 women (55.1%) and 97 men (44.9%), respondents aged 18–25 (66.2%), 26–30 years (20.4%), 31–40 years (8.3%), 41–50 years (4.2%), 51–60 (0.9%). The sample structure roughly reflects the customer portfolio of the four brands, which consists predominantly of clients aged between 18 and 40. The questionnaire was administered both online and offline, the selection of the respondents of the sample was made by using the snowball method.

Brands included in this research are from the quick service restaurant industry, McDonald’s and KFC, and fashion retail sector, Zara and H&M. The fashion retail brands Zara and H&M were chosen because clothing is often used to express one’s identity, such as social status or group affiliation. These purchases are widely accessible, highly visible, and carry symbolic meaning. Additionally, fashion is a commonly studied category in self-congruity research (Fens et al, 2022).

McDonald’s and KFC were selected due to existing research on the link between brand personality and consumer-brand relationships in various countries. These two iconic brands were assumed to have distinct personalities, shaped by their marketing communications. McDonald’s, through its mascot Ronald McDonald, conveys a playful, friendly, and child-oriented image. Though used less today, these associations remain strong. In contrast, KFC’s identity is built around Colonel Sanders, a real person, symbolizing authenticity, nostalgia, trust, and emotional connection.

The analysis of the data was conducted using the SPSS 23 (Manufacturer: IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), AMOS 23 (Manufacturer: IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and Excel Microsoft 365 (Manufacturer: Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Besides profiling the personality structure of the four brands (McDonald’s, KFC, Zara, and H&M), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted for each personality trait in order to assess the differences and thus potential competitiveness aspect of each brand personality. One-way ANOVA uses a single-factor fixed-effects model to compare the effects of one factor on a continuous variable (Bell and Bryman, 2015), based on the F ratio statistic test. The result of the comparison of means between the four brands proved whether the difference between them regarding the variable is statistically significant. The Levene test was used to assess the criterion of the equality of variances of the compared groups. A lower than 0.05 significance level of the Levene test showed the criterion was violated. Consequently, the results obtained from the application of the Welch and Brown-Forsythe tests were taken into account (Field, 2009).

Also, Tukey Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc comparisons were conducted in order to evaluate brand level pair-wise differences on the dimensions of the personality scale (Table 4).

| Personality dimensions | EXTR | AGRE | CONCS | NEURO | OPEN | ||||||

| Brand Comparative (I) Brands (J) | Mean Dif. (I-J) | Sig. | Mean Dif. (I-J) | Sig. | Mean Dif. (I-J) | Sig. | Mean Dif. (I-J) | Sig. | Mean Dif. (I-J) | Sig. | |

| Mc Donald’s | KFC | 0.315 | 0.090 | 0.259 | 0.351 | 0.041 | 0.989 | 0.285 | 0.334 | 0.203 | 0.491 |

| ZARA | 0.134 | 0.662 | 0.027 | 0.997 | –0.122 | 0.698 | 0.261 | 0.293 | –0.294 | 0.090 | |

| H&M | 0.245 | 0.175 | 0.126 | 0.805 | 0.014 | 0.999 | 0.440 | 0.021 | 0.023 | 0.998 | |

| KFC | McDonald’s | –0.315 | 0.090 | –0.259 | 0.351 | –0.041 | 0.989 | –0.285 | 0.334 | –0.203 | 0.491 |

| ZARA | –0.181 | 0.451 | –0.232 | 0.367 | –0.164 | 0.507 | –0.024 | 0.999 | –0.497 | 0.001 | |

| H&M | –0.070 | 0.944 | –0.133 | 0.800 | –0.027 | 0.996 | 0.155 | 0.763 | –0.180 | 0.537 | |

| ZARA | McDonald’s | –0.134 | 0.662 | –0.027 | 0.997 | 0.122 | 0.698 | –0.261 | 0.293 | 0.294 | 0.090 |

| KFC | 0.181 | 0.451 | 0.232 | 0.367 | 0.164 | 0.507 | 0.024 | 0.999 | 0.497 | 0.001 | |

| H&M | 0.111 | 0.724 | 0.099 | 0.856 | 0.136 | 0.547 | 0.179 | 0.548 | 0.317 | 0.030 | |

| H&M | McDonald’s | –0.245 | 0.175 | –0.126 | 0.805 | –0.014 | 0.999 | –0.440 | 0.021 | –0.023 | 0.998 |

| KFC | 0.070 | 0.944 | 0.133 | 0.800 | 0.027 | 0.996 | –0.155 | 0.763 | 0.180 | 0.537 | |

| ZARA | –0.111 | 0.724 | –0.099 | 0.856 | –0.136 | 0.547 | –0.179 | 0.548 | –0.317 | 0.030 | |

HSD, Honestly Significant Difference; EXTR, Extraversion; AGRE, agreeableness; CONCS, Conscientiousness; NEURO, Neuroticism; OPEN, Openness. In the case of values marked in bold, the difference between the means is statistically significant.

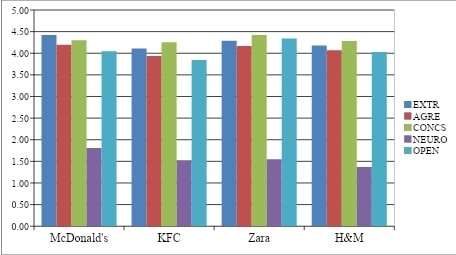

As a conclusion, within the current research in order to illustrate how the four

brands are perceived, thought of and reflected by potential shoppers and

consumers, the preferred brands were profiled and found that: (i) McDonald’s is

more neurotic than H&M (

The profile of the four brands starting from the 5 dimensions of the personality scale is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The personality profile of the analyzed brands.

For hypotheses validation purposes, in order to identify the cause-effect

relationship, we have used structural equation modeling (SEM), Path analysis. In

the next stage, the overall quality of the conceptual model was assessed. The

results obtained were as follows:

The summary of our research hypotheses testing is shown in Table 5.

| Hypotheses | Independent variable | Dependent variable | Regression coefficient ( |

Student test (t) | Significance level (p) | Result |

| 1 | BRAND_PERS | SATIS | 0.036 | 0.349 | 0.727 | Reject |

| 2 | BRAND_PERS | TRUST | 0.309 | 4.770 | 0.000 | Valid |

| 3 | BRAND_PERS | ATTACH | 0.141 | 2.575 | 0.010 | Valid |

| 4 | BRAND_PERS | COMITT | 0.088 | 2.016 | 0.044 | Valid |

| 5 | TRUST | SATIS | 0.271 | 3.527 | 0.000 | Valid |

| 6 | ATTACH | SATIS | 0.323 | 3.020 | 0.003 | Valid |

| 7 | COMITT | SATIS | –0.075 | –0.772 | 0.440 | Reject |

| 8 | CONG_RE | SATIS | –0.006 | –0.092 | 0.927 | Reject |

| 9 | CONG_ID | SATIS | –0.007 | –0.065 | 0.948 | Reject |

| 10 | SATIS | LOYAL | 0.167 | 2.489 | 0.013 | Valid |

| 11 | TRUST | ATTACH | 0.589 | 10.757 | 0.000 | Valid |

| 12 | ATTACH | COMITT | 0.762 | 17.416 | 0.000 | Valid |

Based on the analysis of the values presented in the table above, it can be

concluded that research hypotheses H2, H3, H4, H5, H6,

H10, H11, and H12 were supported. The findings indicate that brand

personality exerts a positive, direct, and statistically significant influence on

brand trust (

The relationship between brand personality and consumer satisfaction with the

brand was not validated; consequently, hypothesis H1 is rejected (p

= 0.727

This study brings contributions to the development of the theory on brand personality, the theory underpinning the consumer-brand personality congruence, but also to the development of the theory of brand-consumer personality.

Many studies have prioritized examining the effects of actual or ideal congruence between consumer self-image and brand image, with fewer focusing on consumer-brand personality congruence. Most research uses Aaker’s (1997) brand personality scale, but in this study, we used a scale by Ferrandi and Valette-Florence (2002a; 2002b), based on Saucier’s (1994) human personality markers. We expanded Ferrandi and Valette-Florence’s scale to include both positive and negative traits and replaced Emotional Stability with Neuroticism to better fit our cultural context.

The present study identified a significant relationship between brand personality and trust, attachment, and commitment and our results also confirm the findings of other authors on this topic (Brakus et al, 2009; Lee et al, 2009; Kim et al, 2015; Ramaseshan and Stein, 2014; Japutra and Molinillo, 2019; R. Valette-Florence and P. Valette-Florence, 2020).

Surprisingly, our results did not confirm previous findings on the link between consumer-brand personality congruence, actual and ideal, and consumer satisfaction, possibly because congruence and self-consolidation theories alone do not fully explain consumer behavior. Similar findings were reported by Chang et al (2001), Ekinci and Riley (2003), and Ekinci et al (2008). This may be due to contextual and sample differences, as our research took place in a different country and involved a predominantly young population. Also, brand personality does not directly influence consumer satisfaction with the brand, but rather indirectly through brand trust and brand attachment. Similar, though sometimes partial, conclusions emerged in other studies. Lombart and Louis (2014) found that in retailer personality, traits like agreeableness and sophistication boost customer satisfaction, while introversion reduces it. In their Malaysian study on consumer-based virtual brand personality (CBVBP) in online banking, Ong et al (2017) reported that customer satisfaction only partially mediates the relationship between brand personality and brand loyalty.

Brand personality does not directly influence consumer satisfaction with the brand, but rather indirectly through brand trust and brand attachment.

Nowadays profiling brand consumers based on several demographic aspects is insufficient to shape the true image of the targeted customers.

For the above reasons, the study aims also to illustrate how the favored brands are perceived in the mind of the consumers, based on the five personality traits.

The One-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD post-hoc comparison analysis show, for example, that there are differences between the analyzed brands, sometimes not very big, in terms of personality profile. Thus, between McDonald’s and KFC there are significant differences concerning the extraversion dimension, the first being more extraverted than the second, while Zara is different from H&M concerning the openness dimension, the first being more open minded.

The findings of our study extend beyond academic theory, offering meaningful contributions to the management field. First, by validating the relationships between brand personality traits and key brand-consumer relational outcomes, we provide empirical evidence that can inform brand strategy. These relationships underscore the importance of crafting a coherent and culturally resonant brand personality in managerial practice. Furthermore, our findings challenge the assumption of a universal link between personality congruence and loyalty, suggesting that managerial approaches must be context-specific and informed by cultural and demographic nuances.

The rejection of some hypotheses also has critical implications for management. The absence of a direct relationship between personality congruence and satisfaction encourages managers to adopt a multi-dimensional approach to consumer-brand alignment, focusing not only on symbolic congruence but also on performance, trust, and experiential factors. Research conclusions, as well managerial approaches, may vary depending on the level of consumer involvement in the decision-making process—low or high involvement—the nature of the involvement—rational or emotional—and the perceived value of the brands, whether utilitarian, hedonic, or functional.

Such comparative profiling enables more precise positioning and highlights potential areas for differentiation, especially in saturated markets like fast fashion and quick-service dining.

Understanding consumer personality and the interplay between brand personality and consumer personality provides marketing managers with valuable insights for effective market segmentation and brand positioning. For instance, positioning a brand as trustworthy may resonate with consumers exhibiting higher levels of neuroticism, whereas a sociable brand personality tends to attract extroverted consumers (Mulyanegara et al, 2009). Knowledge of consumers’ personality profiles enables marketing managers to strategically employ various marketing stimuli to embed compatible personality traits within their brands.

These stimuli include visual identity elements such as logos and typography, advertising campaigns featuring specific presenters or endorsers (Mishra et al, 2015), and auditory components like music (Lara-Rodríguez et al, 2019).

Some researchers suggest that websites impart specific traits to brands (Lara-Rodríguez et al, 2019), while others indicate that web content and advertising serve as brand ambassadors (Lee and Kim, 2018). Additionally, De Moya and Jain (2013) and De Moya and Jain (2017) emphasize the role of communities and social media in shaping brand personality.

In recent years, brand personality studies have shifted focus to the digital realm, investigating how consumers attribute humanlike characteristics to brands during digital interactions. This exploration extends to websites, social networking sites (Ghorbani et al, 2022), and interactions with virtual brand agents, artificial intelligence, and service robots (Calderón-Fajardo et al, 2023). From a managerial perspective, our research holds significance as it provides fresh insights into how brand managers can use brand personality as a predictive tool for assessing customer satisfaction and loyalty levels. In the virtual business landscape, trust is crucial. Validating the link between brand personality and trust is vital for brand managers. By emphasizing sincerity and honesty, companies can boost customer trust, enhancing their brand and overall company credibility. These insights underscore the strategic importance of leveraging brand personality as a trust-building mechanism, guiding brand managers in crafting digital engagement strategies that enhance credibility and foster long-term consumer relationships.

Our study demonstrates that brand personality is a strategic resource that informs segmentation, positioning, and brand communication strategies. Management scholars and practitioners alike can draw from these findings to design more resonant brand experiences and leverage congruence mechanisms for deeper engagement. As digital transformation and AI-powered branding continue to evolve, integrating personality-based brand metrics into performance dashboards may become a key trend in data-driven management practices.

The study focuses on consumers from a single country, which limits the possibility to generalize the results.

Another limitation of our study is the data collection process, which relied on self-reported declarative data about perceived personality and brand relationships, particularly loyalty. Additionally, social desirability may have influenced respondents’ answers, leading to conscious or unconscious distortions in how they described themselves.

Another limitation of our study is the small number of product categories and brands, focusing only on fashion retail and quick-service restaurants. The brands examined serve similar utilitarian and symbolic functions, so including casual dining restaurants, could have enhanced our research.

Future research could also explore the long-term impact of AI-driven brand interactions on consumer trust and emotional attachment. While existing studies have demonstrated that anthropomorphized AI enhances engagement (Lopes et al, 2025), further investigations could assess how sustained exposure to AI-driven branding influences brand loyalty and perceived authenticity. Additionally, a study conducted by Muniz et al (2024) highlights the role of virtual influencers in shaping brand trust, revealing that disclosure of their nonhuman nature can negatively affect consumer perceptions. Similarly, research on luxury brand personality in digital interactions suggests that modern brands face higher scrutiny online, while traditional brands maintain stronger consumer trust (Cowan and Kostyk, 2024).

These findings suggest that future studies should examine cross-cultural variations in consumer responses to AI-powered brand personalities, providing valuable insights into how different markets interact with and interpret virtual brand agents.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; KMO, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin; AVE, average variance extracted; CR, composite reliability; UAE, United Arab Emirates; WOM, word-of-mouth; CONS_PERS_RE, actual consumer personality; CONS_PERS_ID, ideal consumer personality; BRAND_PERS, brand personality; CONG_RE, actual congruence; CONG_ID, ideal congruence; SATIS, consumer satisfaction; TRUST, brand trust; ATACH, brand attachment; COMITT, brand commitment; LOYAL, loyalty; Tukey HSD post hoc test, Tukey Honestly Significant Difference post hoc test; GFI, Goodness of Fit Index; AGFI, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index; NFI, Normed Fit Index; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

Data and Materials available upon request.

CD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing; GP: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing—review & editing; AMM: Investigation, Resources, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing; RIN: Conceptualization, Resources, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; SAS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing—original draft; CC: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

This article was supported by the UVT1000 DEVELOP fund of the West University of Timisoara.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGpt 4 in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.