1 Department of Tourism Management, Faculty of Economics, Istanbul University, 34126 Istanbul, Turkiye

2 Department of Management Information Systems, Kesan Yusuf Capraz College of Applied Science, Trakya University, 22100 Edirne, Turkiye

3 Department of Tourism and Hotel Management, Vocational School, Istanbul Yeni Yüzyil University, 34040 Istanbul, Turkiye

Abstract

This article empirically examines the relationship between holiday recovery experience and life satisfaction, along with the mediating roles of optimism and job satisfaction after vacation. Data were collected from a sample of 361 white-collar workers in Istanbul. Structural equation modelling was employed to test the hypotheses. The findings reveal a positive relationship between holiday recovery experience and life satisfaction. In addition, holiday recovery experience was positively associated with both optimism and job satisfaction after vacation. Optimism and job satisfaction after vacation were found to partially mediate the relationship between holiday recovery experience and life satisfaction. The results offer practical implications for white-collar employees and business organisations. Understanding the importance of the holiday recovery experience and its influence on life satisfaction may help individuals plan more restorative and effective vacations. This study is the first in the literature to explore the mediating effects of optimism and job satisfaction after vacation in the relationship between holiday recovery experience and life satisfaction. It contributes to the growing body of research on the psychological and organisational benefits of recovery experiences for white-collar workers.

Keywords

- vacation

- holiday recovery experience

- life satisfaction

- job satisfaction

- optimism

Throughout human history, numerous inventions and technological advancements have significantly improved people’s quality of life, making it more comfortable than ever before. Despite these advancements providing various conveniences, modern life can also have adverse effects on individuals. In the digital age, numerous instances exist where technological progress complicates people’s lives. For example, individuals exposed to harsh and unpleasant work environments often experience poor psychological well-being and are at risk of developing health problems (Reynolds, 1997; Sonnentag and Kruel, 2006). In such work environments, stress and mental health issues can accumulate over time, frequently leading to burnout or other chronic conditions (Pflügner et al, 2021).

Extended working hours negatively impact individuals’ physical and mental well-being (Sparks et al, 2018; Virtanen et al, 2012). Furthermore, individuals today contend with heightened stress and challenges characteristic of the modern era, stemming from workplace demands, intense competition, socioeconomic factors and other stressors. As these pressures increase, the distinction between personal and professional life becomes increasingly blurred, further exacerbating stress. This is particularly pronounced among urban dwellers, who face unique pressures and strains in their daily lives (Amin and Richaud, 2020; Ramsden and Smith, 2018). Although urban settings may limit individuals’ access to green spaces or quiet areas conducive to relaxation, leisure activities within their living areas can offer an alternative means of recovery. For this reason, vacations away from one’s immediate surroundings have become an essential form of recuperation. Advances in transportation technology have made travel faster, more affordable, and more accessible for tourists who are willing and able to travel. In addition to leisure activities within residential areas, taking a vacation outside one’s usual environment has become a key method of recovery (Altunel et al, 2017). Since recovery experiences (RE) serve as vital tools for employee recuperation, managers should not overlook the significance of leisure activities—whether near home or away (i.e., vacations)—in promoting employee well-being.

Various leisure activities affect employee recovery (Altunel and Akova, 2016; Saltık and Akova, 2019). Thus, this study specifically examines vacation as a form of leisure activity. RE encompass a range of activities, such as relaxation techniques, engaging in enjoyable hobbies, disconnecting from work-related activities or spending quality time with family and friends. These activities are essential for both mental and physical recovery and should be prioritised in work-life balance strategies. Additionally, other factors influencing recovery may include the extent to which employees can detach from work-related stressors during their vacation, the level of support received from superiors and teammates upon returning to work and the availability of resources and opportunities for personal growth and development in the workplace (Altunel et al, 2017).

Previous studies have demonstrated a positive association between vacation and life satisfaction (LS) (Chen et al, 2016), subjective well-being (Chen et al, 2013) and psychological well-being (Syrek et al, 2018). Additionally, vacation plays a crucial role in employee recovery, leading to evident positive effects on health and well-being (De Bloom et al, 2009). Furthermore, the holiday recovery experience (HRE) is significant in relation to optimism, LS and job satisfaction (JS). While some studies have examined the effects of HRE on LS (Chen et al, 2016), research on its impact on JS after vacation and optimism remains limited. Hence, further investigation is warranted to better understand HRE. Given its potential to enhance employee recovery, a comprehensive understanding of HRE can significantly assist managers in developing effective workplace health strategies. Moreover, studies on the HRE of white-collar workers operating in high-stress environments and its positive effects remain scarce. This gap motivated the authors of this study to examine the impact of white-collar employees’ HRE on their LS, JS after vacation and optimism.

The literature extensively reviews the relationship between JS and LS (Adhikari, 2023; Głaz, 2022; Judge and Watanabe, 1993; Kase and Doolittle, 2023; Marcionetti and Castelli, 2023; Üstgörül and Catalin, 2023). Previous studies on JS have explored various factors, such as unlimited vacation days (Dries, 2010), optimism (Ahmed, 2012; Burhanudin et al, 2020; Munyon et al, 2010; Yang et al, 2023; Zhang et al, 2020) and self-esteem (Ahmed, 2012) across different sectors. JS is defined as the emotional state and behavioural expression resulting from employees’ job evaluations (Golbasi et al, 2008), while LS refers to the degree to which individuals find their lives meaningful and fulfilling (VandenBos, 2015). Although previous studies indicate the significance of LS for JS, some research suggests that JS significantly influences LS (Cayupe et al, 2023), contradicting earlier literature. These studies highlight the bidirectional relationship between JS and LS. Overall, the existing literature underscores a strong relationship between these two concepts.

On the other hand, LS also influences employees’ workplace behaviours (Zhao et al, 2016), while employee JS significantly contributes to business success. Employees with higher LS levels tend to be more engaged and motivated at work, enhancing overall organisational performance (Bernales-Turpo et al, 2022). Achieving work-life balance is crucial for fostering satisfaction and promoting positive outcomes that improve employees’ overall well-being. Work-life balance also mediates the relationship between employee engagement and LS (Cain et al, 2018). Managers must understand the factors that can disrupt employee JS and take appropriate measures. Earlier studies have established a positive relationship between JS and LS (Judge and Watanabe, 1993). Moreover, previous research has also found a positive relationship between optimism and LS (Kardas et al, 2019). However, there is no evidence indicating the mediating effect of JS after vacation on the relationship between HRE and LS.

Optimism, defined as a positive expectation for the future (Carver et al, 2010), is a critical factor influencing employees’ daily and professional lives. It encompasses positive perceptions of life, expectations and general outlook (Dember et al, 1989), impacting both JS (Mishra et al, 2016) and LS (Piper, 2022). As a dimension reflecting positive expectations, optimism correlates with greater subjective well-being, particularly during challenging times (Carver et al, 2010). McCabe and Johnson (2013) observed a significant effect of holidays on optimism. Moreover, existing literature suggests a strong association between optimism and JS (Mishra et al, 2016; Zhang et al, 2020), LS (Leung et al, 2005; Piper, 2022) and mental recovery (Carbone and Echols, 2017), highlighting its positive impact on employee well-being.

According to the restoration theory, activities such as vacations or travel can help individuals recover both mentally and physically. The stresses, routines and intense work pace of daily life can lead to mental fatigue. Tourism allows individuals to escape this exhaustion and restore their energy, thereby improving their mental health (Lehto, 2013). Based on this theory, it can be assumed that individuals who recover during vacation will experience increased optimism, which will, in turn, positively affect their LS. However, there is a lack of evidence regarding the mediating effect of optimism on the relationship between HRE and LS. Hence, exploring the potential mediating role of optimism between HRE and LS is essential.

Moreover, in well-being studies, optimism has been considered a mediating variable. Given its mediating role in other studies, optimism can also serve as a mediating variable in this study (Karademas, 2006; Serrano et al, 2020). Recognising this, it is important to investigate how optimism functions within the framework of employee recovery. In this context, the main aim of this study is twofold:

• To examine the mediating effect of optimism on the relationship between HRE and LS.

• To examine the mediating effect of JS after vacation on the relationship between HRE and LS.

Limited studies indicate that HRE affects LS (Chen et al, 2016). Previous research has shown that tourism satisfaction (Halim and Rahman, 2017) and both passive and active tourism experiences (Chen et al, 2018) act as mediators in the relationship between HRE and LS. Given the limited research on the mediation effect in the relationship between HRE and LS, further studies are needed for a more comprehensive understanding. Furthermore, determining whether JS after vacation and optimism amplify the effect of HRE on LS can provide insights into their potential synergistic impact on various work-related factors, such as motivation, loyalty and employee adaptation to work after vacation. This can, in turn, positively contribute to organisational success.

This study makes significant theoretical and practical contributions by extending previous research on the impact of HRE on JS within the relevant literature stream. Additionally, it deepens the understanding of the link between HRE and LS by highlighting the mediating effects of optimism and JS after vacation. Furthermore, this study enhances the comprehension of the mechanisms underlying HRE and presents novel findings that bolster existing theoretical frameworks.

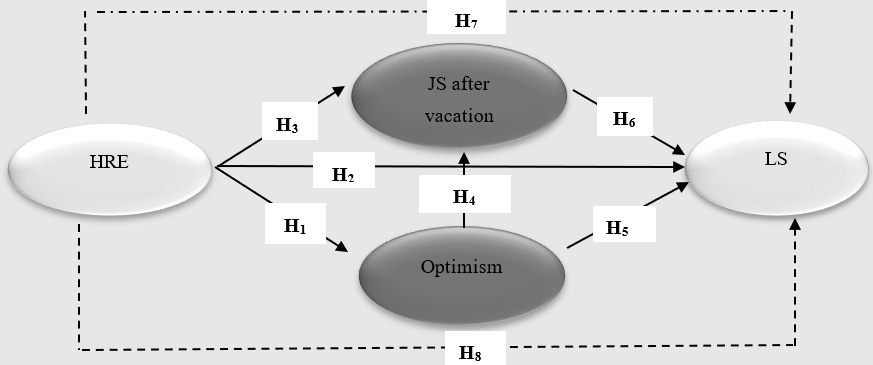

The results of this study have practical implications for both employees and organisations. Examining the proposed model (see Fig. 1) also contributes to the theoretical understanding of the mediating effects of JS after vacation and optimism on the relationship between HRE and LS.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Proposed model. HRE, holiday recovery experience; JS, job satisfaction; LS, life satisfaction.

With the rapidly increasing mass tourism movements after the Second World War, the expansion of annual leave rights and the rise in disposable income among employees in industrialised countries, going on vacation has become a fundamental aspect of modern life (Sezgin and Yolal, 2012). As a result, vacations have evolved from being a luxury to an essential part of contemporary work culture.

A vacation can be defined as leisure time distinct from work and has garnered increased attention and debate in recent decades. Workers worldwide, particularly in developed countries, are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of taking time off for themselves. Consequently, business owners are recognising the need for employees to have time away from work (Etzion, 2003). This growing recognition has spurred a broader focus on the physical and mental recovery associated with taking time off, not just for personal well-being but also for productivity in the workplace and business success.

Many researchers have revealed the positive psychological consequences of vacation (e.g., (Westman and Etzion, 2001), (Chen et al, 2013), (Chen et al, 2016)). For example, Westman and Etzion (2001) found that vacation can benefit businesses by reducing stress and burnout, allowing a person to step away from work and thereby break the cycle of resource loss. Moreover, the relationship between taking vacations, employee health and the challenges employees experience at work has begun to attract the attention of scholars. Since then, research on vacation has examined its relationship with variables such as LS (Chen et al, 2017; Chen et al, 2018; Hoopes and Lounsbury, 1989; Lončarić et al, 2018; Pagán, 2015; Pan et al, 2020; Sirgy et al, 2011), JS (Dries, 2010), burnout (Etzion, 2003; Westman and Etzion, 2001), work stress (Etzion, 2003; Westman and Etzion, 2001), well-being (Chen et al, 2013; De Bloom et al, 2012; Strauss-Blasche et al, 2000), behavioural intention (Lončarić et al, 2018) and health (Tarumi et al, 1998). These studies underline the growing recognition that taking vacations not only improves individual well-being but also enhances organisational outcomes.

During vacation periods, employees are in better emotional and physical states, feeling healthier and more energetic. They experience reduced tension and fatigue, leading to increased satisfaction (De Bloom et al, 2012). Vacations have a significant impact on both personal and business aspects of people’s lives, allowing them to escape from stressful routines. According to Chen et al (2013), vacations increase individuals’ well-being. Furthermore, Chen et al (2016) observed that another positive psychological outcome of holidays is recovery, which helps restore impaired mood (Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007). This recovery process is essential not only for individual health but also for sustaining long-term productivity.

Researchers argue that insufficient RE can harm individuals’ psychological well-being. In their study, Sonnentag and Fritz (2007) found that RE is related to most psychological well-being indicators. The demands of business life can negatively impact an individual’s mood. However, participation in non-work activities can help individuals restore their moods. At this point, RE emerges as a critical concept. RE is defined as the degree to which a person perceives that energy resources help them restore themselves during non-work time through activities (Kinnunen et al, 2011). To encourage beneficial RE, employees may try to avoid work-related activities in their leisure time.

In prior studies, HRE has generally been associated with well-being (Kawakubo and Oguchi, 2019), LS (Chen and Petrick, 2016; Chen et al, 2016; Chen et al, 2018; Halim and Rahman, 2017; Kawakubo and Oguchi, 2019), tourism satisfaction (Chen et al, 2016; Halim and Rahman, 2017), vacation duration (Chen et al, 2018) and creativity (Kawakubo and Oguchi, 2019). Some studies have found correlations between HRE, LS and JS, but no research has examined the effect of HRE on optimism or the mediating effect of optimism on HRE and LS. This gap in research presents a valuable opportunity for further investigation.

Two theories can be considered to rationalise HRE: effort-recovery theory (ERT) and conservation of resources theory (CRT) (Chen et al, 2016; Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007). According to ERT (Chen et al, 2016), employees working in stressful environments are often exposed to high workloads, leading to job-related issues such as sickness, absenteeism and inefficiency. Participation in recreational activities, such as socialising, taking vacations and watching movies, can mitigate these adverse effects by promoting psychological well-being and relaxation (Chohan et al, 2019). Meanwhile, CRT posits that people seek to acquire and maintain not only financial resources, such as property and cars, but also personal resources, such as a positive mood and high energy (Chen et al, 2016; Hobfoll and Wells, 1998). The theory suggests that stress can deplete personal resources and well-being, necessitating access to new resources such as positive energy and motivation to alleviate stress (Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007). Both theories provide a framework for understanding how vacations and RE help individuals replenish their personal resources. They can also be applied to understand HRE and its effects on LS, JS after vacation and optimism.

Optimism is a psychological dimension that corresponds to perceptions and expectations of the positive aspects of life (Dember et al, 1989). This dimension can be considered a structure in which cognitive, emotional and motivational processes are intertwined (Carver and Scheier, 2014). It encompasses positive effects (i.e., positive moods) and the expectation of positive outcomes, even in unfavourable conditions, with such expectations not limited to a particular behaviour or classification (Dixon and Schertzer, 2005; Scheier and Carver, 1985; Scheier and Carver, 1992; Scheier et al, 2001). Furthermore, optimism is an important determinant of outcomes or markers for health (Geers et al, 2009; Rasmussen et al, 2009).

Given its role in shaping both emotional and physical health outcomes, optimism is a key psychological resource that can be nurtured through RE, such as vacations. Previous academic studies (e.g., (McCabe and Johnson, 2013)) have identified various relationships between positive mood and taking vacations. Based on this, the present study examines this relationship within the context of RE during vacations and JS after vacation.

As mentioned earlier, recovery during vacation is crucial for mental health (e.g., subjective well-being, LS). This is why researchers frequently investigate recovery and well-being. Moreover, previous studies have yielded significant findings in this area. Chen et al (2016) explored the relationship between HRE and LS, with tourism satisfaction acting as a mediating variable. Their findings indicated that people who had control over their vacation activities, felt relaxed and detached from work and engaged in new and demanding experiences were more likely to report higher overall LS.

Chen and Petrick (2016) examined how HRE during a leisure trip affected perceived LS post-trip. Their study found that all four factors of HRE had positive effects on LS. The findings also suggested that even a short weekend getaway can help individuals recover from work stress, while longer vacations provide greater opportunities for deeper recovery. Halim and Rahman (2017) investigated the impact of HRE on LS, noting that the direct effect of HRE on LS was not significant. However, they found that the indirect effect of HRE on LS, mediated through tourism satisfaction, was significant. Kawakubo and Oguchi (2019) revealed that RE during vacation positively influenced employees’ creativity and enhanced both occupational well-being and LS. More recently, Chen et al (2018) demonstrated that autonomy is a key factor in the relationship between vacation experiences and LS, with its effect on LS mediated by both passive and active tourism experiences.

Based on the discussions above, it is evident that HRE has a positive effect on individuals’ mental well-being. Similarly, it can be hypothesised that a positive psychological outcome, such as optimism, may also be influenced by HRE, similar to its impact on LS.

To summarise, based on the findings of previous studies, it can be reasonably assumed that HRE plays a significant role in employees’ LS and optimism. As prior research indicates that HRE affects positive mental well-being outcomes, further studies are needed to expand the literature on this topic. Thus, the following research hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1: HRE positively affects employees’ optimism.

Hypothesis 2: HRE positively affects employees’ LS.

People experience job stress as a result of their work and make efforts to cope with the challenges they encounter in daily life. To manage this stress, they often seek holidays as a means of recovery, allowing them to distance themselves from their usual environments and take a break from work (De Bloom et al, 2009; Etzion, 2003). For example, Kinnunen et al (2010) found that RE can serve as a buffer against the tensions associated with job insecurity. Furthermore, Cheng (2019) found that RE has a direct impact on LS and JS. Similarly, Headrick et al (2023) discovered that RE generally increases job engagement and is positively associated with better job performance. Building on previous studies in the literature, the following research hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 3: HRE positively affects employees’ JS after vacation.

Optimism is an important predictor of positive physical health outcomes (Rasmussen et al, 2009). It has also been widely linked to JS (Ahmed, 2012; Burhanudin et al, 2020; Zhang et al, 2020). Additionally, optimism has been found to influence employees’ JS by moderating the relationship between grit and JS (Yang et al, 2023). Furthermore, optimism enhances employees’ creativity, which is crucial for overall performance. For these reasons, fostering optimism in employees is vital for businesses seeking to enhance productivity (Rego et al, 2012). Lastly, optimism is a strong positive predictor of subjective well-being and overall functioning (Carver et al, 2010).

As previously discussed, several researchers have found a significant impact of optimism on both physical and mental well-being. These studies consistently demonstrate a positive correlation between optimism and overall well-being (Conversano et al, 2010; Souri and Hasanirad, 2011). Previous research has also revealed that optimism positively affects LS and JS (Ahmed, 2012; Al-Mashaan, 2003; Bailey et al, 2007; Kluemper et al, 2009). In this regard, it is believed that individuals experience improvements in their physical and mental health during holidays. As a result, optimism among white-collar workers, who constitute the sample of this study, may increase during their holidays, potentially leading to higher levels of JS after vacation and LS. Thus, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 4: Optimism positively affects JS after vacation.

Hypothesis 5: Optimism positively affects LS.

LS refers to a person’s cognitive assessment of every aspect of their life based on self-selected criteria (Pavot and Diener, 1993). Another form of satisfaction is JS, which is closely associated with LS. JS is an emotionally pleasant state resulting from factors such as achieving or fulfilling individual business values (Locke, 1969). Additionally, JS is one of the most significant factors in defining employees’ attitudes in the workplace. The psychological well-being of individuals working in stressful jobs tends to decline, negatively impacting job performance (Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007). Therefore, individuals need leisure time, such as a vacation, to reduce stress levels. A vacation is an activity that allows individuals to unwind and fosters many positive emotions, such as happiness, love and high spirits (Demirbulat and Avcikurt, 2015).

Several studies (Bialowolski and Weziak-Bialowolska, 2021; Rode, 2004) indicate that the relationship between JS and LS is positive. However, a study conducted by Raz et al (2011) found that vacations have no effect on increasing JS. Previous studies have not examined the relationship between JS after vacations and LS among white-collar workers, leaving it unclear whether JS after vacation changes and how it affects LS. Therefore, this study investigates whether JS after vacation positively affects LS, contributing to the literature by revealing the impact of JS following a vacation on LS. Based on previous literature, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 6: JS after vacation positively affects LS.

Prior studies have revealed that HRE positively affects LS (Chen and Petrick, 2016; Chen et al, 2016; Chen et al, 2018; Kawakubo and Oguchi, 2019). However, Halim and Rahman (2017) found no significant direct effect of HRE on LS. Instead, they identified a significant indirect effect of tourism satisfaction between HRE and LS, suggesting that the relationship between HRE and LS may be mediated by another variable.

Moreover, JS (Hayat and Afshari, 2022; Widhy et al, 2022) and optimism (Tolentino et al, 2022; Zaheer and Khan, 2022) frequently appear as mediators or moderators in the literature. Previous research has determined that optimism (Karademas, 2006) and JS (Ocen et al, 2017) play mediating roles. For example, Munyon et al (2010) demonstrated that optimism can moderate the relationship between organisational citizenship behaviour and JS. However, no studies have investigated the mediating effect of JS after vacation and optimism on the relationship between HRE and LS, despite arguments that this relationship is mediated by tourism satisfaction (Chen et al, 2016; Halim and Rahman, 2017) and passive and active tourism experiences (Chen et al, 2018). Furthermore, it remains unclear whether JS after vacation mediates the relationship between HRE and LS.

Previous studies have determined that optimism has both direct (Zhang et al, 2020) and indirect positive effects on JS (Yang et al, 2023). Additionally, prior research has found that JS positively affects LS (Aydintan and Koç, 2016).

Based on the discussion above, several inferences can be drawn. First, individuals with higher levels of optimism may experience greater LS. This is because individuals with increased optimism tend to focus on positive changes, which can enhance their overall LS. In this context, optimism, as a perspective, could act as a moderator that strengthens the impact of HRE on LS. Second, individuals who experience recovery during a vacation may feel mentally relaxed upon returning to work, which could lead to increased JS after vacation. Individuals who are satisfied with their work may also experience an increase in LS. Based on this explanation, JS after vacation could serve as a moderator in this relationship.

To summarise, the mediating effects of JS after vacation and optimism on the relationship between HRE and LS require further investigation, as JS and optimism are positive determinants of LS. Thus, this research proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 7: JS after vacation plays a mediating role in the effect of HRE on LS.

Hypothesis 8: Optimism plays a mediating role in the effect of the HRE on LS.

In this study, a two-part questionnaire was designed to collect data from the participants. In the first part of the questionnaire, 27 items measure HRE, optimism, JS after vacation and LS. HRE was measured with 15 items adapted from the recovery experience questionnaire devised by Sonnentag and Fritz (2007). This scale consists of four dimensions: psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery and control. The items of this scale were revised to measure HRE.

Five items from the satisfaction with life scale designed by Diener et al (1985) were used to measure LS. This scale consists of one dimension and five items. Optimism was measured with four items adapted from Hashim (2018), who originally adapted them from Wagnild and Young’s (1993) resilience scale. These items were chosen as they were the most appropriate for this study in terms of content. Moreover, they allow the authors to measure optimism with fewer items. Additionally, these items have been utilised in numerous academic studies spanning over 30 years, demonstrating strong reliability and validity (Beckett, 2011). While initially employed in psychology (Wagnild and Young, 1993), the items have gradually gained preference in other social science fields, such as management, organisation and educational sciences. For instance, they were utilised in a study examining the relationship between psychological resilience and employee burnout in the workplace (Beckett, 2011). As such, the authors of the present study deemed these items suitable for their research.

JS after vacation was measured with three items adapted from Judge et al (1998)’s study. The second portion of the questionnaire covered the demographic characteristics of participants, including gender, age, marital status, level of education and occupation.

These scales were selected as they have been validated in many academic studies (e.g., (Mojza et al, 2010), (Kinnunen et al, 2011)). All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘strongly agree’). The authors translated these scales into Turkish, after which two academicians who are specialists in their fields reviewed the translated items. After constructing the surveys, a pilot test with 30 participants was conducted. Following this stage, no significant modifications were made.

Utilising the convenience sampling method (Etikan et al, 2016), a questionnaire was administered to white-collar employees in Istanbul. According to the Turkish Language Association, white-collar workers are defined as those who do not rely on physical strength in production. In Turkiye, they are commonly referred to as civil servants (Turkish Language Association, 2024).

There are several reasons why white-collar employees were chosen as the focus of this study. First, the term ‘white collar’, commonly used both in literature and everyday language, refers to individuals who are educated, well-compensated and often occupy positions near the upper echelons of management (Erdayı, 2012). Consequently, white-collar workers are more inclined to prioritise taking vacations compared to their blue-collar counterparts, as their higher annual income means they can afford vacation travel more readily. Moreover, in Turkiye, the financial circumstances of white-collar workers are typically higher than those of blue-collar workers (TUIK, 2023).

As Turkiye’s largest city, with a population of 16 million, the research was conducted in Istanbul (TUIK, 2024). The city itself contributes 30% to the country’s total economic output, largely driven by a significant portion of white-collar workers (TUIK, 2022).

As it is a large and stressful city for those who live and work there (Pouya et al, 2016), white-collar employees in Istanbul—as in other major cities—participate in leisure activities and take vacations to rejuvenate themselves and recover from work-related stress (Tarumi et al, 1998). Since the education levels and incomes of white-collar employees are higher than those of blue-collar employees (Ateş et al, 2014), they have more financial opportunities to take vacations, and their tendency to go on vacation is significantly higher than that of blue-collar employees.

Thus, it was more convenient for the authors to conduct research on white-collar workers who can afford to go on vacation rather than on blue-collar workers. Additionally, as Istanbul is Turkiye’s most important city in terms of commerce, tourism, education and culture, and is home to most of the country’s white-collar workforce, researching this demographic was particularly relevant to the study’s objectives.

The questionnaire was conducted between 10 March and 26 April 2019. Two main criteria were put forward when selecting research units. First, the participants should be white-collar workers in Istanbul. Second, participants must have travelled for a vacation in the past year. The identities of the participants remained anonymous.

Some difficulties were encountered during the questionnaire application process. The most significant of these was the lack of sufficient time for white-collar workers to complete the questionnaire during working hours. Therefore, participants were approached during breaks and after work.

Moreover, white-collar workers asked researchers to obtain their consent before participating in the questionnaire. Data collection was conducted in the workplaces of white-collar employees. Additionally, multiple site visits were made to the same businesses at different times to ensure greater participation.

At the end of this process, 361 usable questionnaires were included in the data

analysis. Since there are no strict population figures for white-collar workers,

10 participants per item were deemed appropriate for such studies (Wolf et al, 2013). Considering the number of items in this study, 361 surveys was deemed to

be a suitable number for data analysis, as this number exceeds 220 (22 items

In the case where data are collected via a questionnaire, bias may occur during the data collection stage. Therefore, the authors of this research followed several steps to avoid bias when collecting and analysing the data. First, participants were asked to join the study willingly. This process aimed to reduce social desirability bias in participants’ responses (Podsakoff et al, 2003). Then, the likelihood of common method variance was evaluated using Harman’s one-factor test (Fuller et al, 2016). The result of the test showed that the common factor explains 38% of the variance in the research model, which is below the 50% cut-off threshold. In addition, variance inflation factor (VIF) values were evaluated. The results showed that the VIF values ranged between 1.356 and 1.642, indicating acceptability.

The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

| Gender | Female | 227 | 62.9 |

| Male | 134 | 37.1 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 36 | 10.0 |

| 26–33 | 140 | 38.8 | |

| 34–41 | 131 | 36.3 | |

| 42–49 | 35 | 9.7 | |

| 50 and older | 19 | 5.3 | |

| Marital status | Married | 200 | 55.4 |

| Single | 161 | 44.6 | |

| Education | High school | 31 | 8.6 |

| Associate degree | 28 | 7.8 | |

| Undergraduate | 234 | 64.8 | |

| Master/Doctorate | 61 | 16.9 | |

| Unknown | 7 | 1.9 | |

| Profession | Bank Clerks | 188 | 52.1 |

| Officers | 95 | 26.3 | |

| Teachers | 27 | 7.5 | |

| Others | 39 | 10.8 | |

| Architect-Engineers | 12 | 3.3 | |

| Positions | Non-Managerial White-Collar Employees | 206 | 57.0 |

| First Line Managers | 52 | 14.4 | |

| Middle Managers | 67 | 18.6 | |

| Top Managers | 36 | 10.0 |

The gender distribution was unequal; 62.9% were female, and 37.1% were male. Most participants were between 26 and 33 years old (38.8%), followed by the 31–41 age group (36.3%). Most of the participants were married (55.4%). In terms of education, 64.8% of the participants were undergraduates. When the participants are examined in terms of their profession, it is seen that bank clerks were in the first place (52.1%). Most of the participants were non-managerial white-collar employees (57.0%).

SEM was performed to test the model’s goodness of fit. SEM was used because the

data showed normal distribution according to the kurtosis and skewness values

(Appendix A). The goodness-of-fit indices for the structural model were as

follows:

| CFI | GFI | RMSEA | IFI | NFI | ||

| Before Modifications | 2.160 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.057 | 0.97 | 0.94 |

| After Modifications | 2.079 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.055 | 0.97 | 0.94 |

Remark: Acceptable fit indices of SEM models:

sd, standard deviation; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; GFI, Goodness of Fit Index; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; IFI, Incremental Fit Index; NFI, Normed Fit Index.

The goodness-of-fit indices for the structural model were as follows: 455.404

with 219 degrees of freedom (

| Constructs | Items | AVE | CR | Factor loadings | |

| LS | SL1 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.76 | |

| SL3 | 0.91 | ||||

| SL4 | 0.77 | ||||

| HRE | Factor 1: Psychological Detachment | HRE1 | 0.87 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| HRE2 | 0.97 | ||||

| HRE3 | 0.89 | ||||

| Factor 2: Relaxation | HRE5 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.91 | |

| HRE6 | 0.94 | ||||

| HRE7 | 0.92 | ||||

| Factor 3: Mastery | HRE8 | 0.66 | 0.85 | 0.97 | |

| HRE9 | 0.75 | ||||

| HRE11 | 0.70 | ||||

| Factor 4: Control | HRE12 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.83 | |

| HRE13 | 0.93 | ||||

| HRE14 | 0.95 | ||||

| HRE15 | 0.93 | ||||

| Optimism | O1 | 0.72 | 0.91 | 0.88 | |

| O2 | 0.88 | ||||

| O3 | 0.86 | ||||

| O4 | 0.78 | ||||

| JS after vacation | JS1 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.90 | |

| JS2 | 0.92 | ||||

| JS3 | 0.94 | ||||

AVE, Average Variance Extracted; CR, Composite Reliability; LS, Life Satisfaction; HRE, Holiday Recovery Experience; JS, Job Satisfaction.

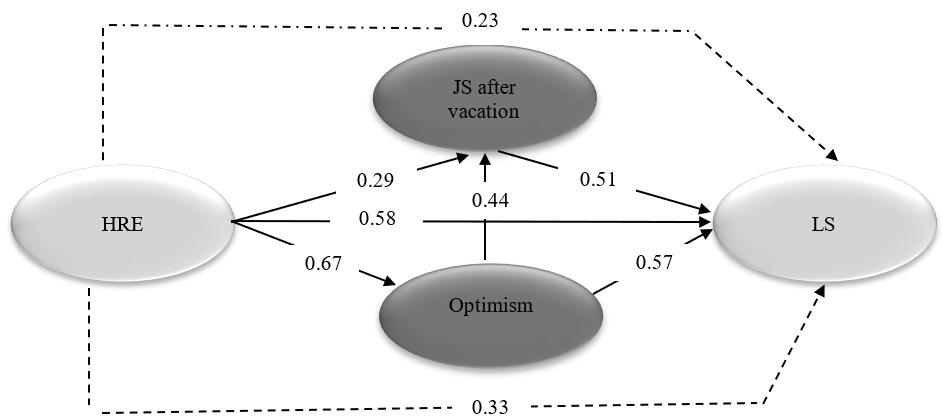

As can be seen in Fig. 2, path coefficients from HRE to LS (

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Coefficients of the research model.

Moreover, the effect of HRE on JS after vacation (

Initially, it was first tested whether the independent variable positively

affected the dependent variables. Once significant was found significant

(p

The current study examined the relationship between HRE, optimism, JS after vacation and LS. Additionally, it explored the mediating effect of JS after vacation and optimism on the relationship between HRE and LS. Data were collected through a questionnaire administered to 361 white-collar individuals residing and working in Istanbul, aligning with the study’ objectives. The research hypotheses were tested using SEM. The findings of the study are novel within the existing literature and offer insights into HRE, JS after vacation, optimism and LS.

The study produced several important findings. First, the SEM results showed that HRE positively affects employees’ LS. This result is consistent with previous research (Chen and Petrick, 2016; Chen et al, 2016; Kawakubo and Oguchi, 2019), supporting the conclusion that white-collar workers who experienced recovery during a holiday saw an increase in LS. This finding highlights the importance of recovery during holidays for the LS of white-collar workers. Second, this study found that HRE positively affects white-collar employees’ optimism and JS after vacation. This result is significant as it demonstrates the impact of HRE on both optimism and JS after vacation.

Third, white-collar employees’ optimism positively affects their JS after vacation. This result is consistent with previous studies not related to vacations (Ahmed, 2012; Burhanudin et al, 2020; Zhang et al, 2020). In this field, this finding is original, as this study specifically investigated the relationship between optimism and JS after vacation. The results showed that increased optimism among white-collar workers leads to greater JS after vacation.

Fourth, white-collar employees’ optimism positively affects their LS. This is in line with previous studies that found a significant relationship between optimism and LS in different samples (Kapikiran, 2012). This result shows how increased optimism enhances LS among white-collar employees and highlights the importance of holidays for such workers.

Fifth, white-collar employees’ JS after vacation positively affects their LS. Although this result aligns with previous studies on JS and LS not related to vacations (Bialowolski and Weziak-Bialowolska, 2021; Rode, 2004), this study additionally found that JS after vacation, which is positively affected by HRE, also has a positive effect on LS.

Sixth, the relationship between HRE and LS following vacations for white-collar workers is partially mediated by JS after vacation and optimism. Previous studies have determined that tourism satisfaction (Chen et al, 2016; Halim and Rahman, 2017) and passive and active tourism experiences (Chen et al, 2018) mediate the effect of HRE on LS. In this case, it appears that optimism and JS after vacation also mediate the relationship between HRE and LS, similar to the mediating effect of tourism satisfaction and passive and active tourism experiences. It is conceivable that there may be a relationship between optimism, LS, tourism satisfaction and passive and active tourism experiences.

Based on the findings, this study makes both theoretical and practical contributions. In terms of theoretical contribution, this study adds to the body of knowledge in several ways. For one, only a few studies have empirically examined the relationship between HRE and LS, and only a small number have analysed the mediating effect between HRE and LS. In these studies, mediating effects are explained through tourism satisfaction (Halim and Rahman, 2017) and both passive and active tourism experiences (Chen et al, 2018). Unlike other studies, this research investigates the mediating effect of JS after vacation and optimism between HRE and LS. In this respect, the findings expand the HRE, LS, JS after vacation and optimism literature. Moreover, this paper is the first in the related literature to explore the mediating effects of JS after vacation and optimism on the relationship between HRE and LS.

In terms of practical contribution, the findings of this study can help business managers better understand JS after vacation and develop new methods to increase employee LS, JS and optimism. As such, they can create a more productive work environment. Additionally, destination marketers can better understand the expectations and desires of white-collar workers when designing advertisements and services.

This research is not exempt from certain limitations. However, despite these limitations, this paper also opens new avenues for future studies. First, this study was conducted on white-collar employees residing in Istanbul, Turkiye. Therefore, future studies could explore other regions worldwide. Conducting similar research in countries with diverse socioeconomic conditions could lead to varied results. Second, while this study measures LS, JS after vacation and optimism, future studies could include pre- and post-vacation measurements. Third, the data in this study were solely obtained through a questionnaire. Future research could consider using a mixed-method approach. Fourth, control variables were not included in the research model. Incorporating control variables in future studies may strengthen the evidence supporting the research findings, leading to more reliable results. Fifth, this study focused on the impact of HRE, JS after vacation and optimism on LS, and the attendant effects may not dissipate immediately but could extend over a longer period. Future studies could compare the effects observed a few days after the vacation with those observed months later. Finally, additional variables could be incorporated into the model, and JS after vacation and optimism could be measured based on vacation types, duration, destination, demographic attributes, etc.

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

OA conceptualized the study, contributed to the design of the research process, and was involved in the editorial revisions. MÖ performed literature review, the data analysis, and contributed to editorial revisions. MEB contributed to the data collection, literature review and participated in manuscript revisions. GŞ led the literature review and contributed to the editorial revisions. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable contributions of all participants in this study.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See Appendix A.

| Items | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| SL1. In most ways, my life is close to my ideal. | –244 | –484 |

| SL3. I am satisfied with my life. | –349 | –688 |

| SL4. So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life. | –376 | –513 |

| RE1. I forget about work on vacation. | –369 | –1.150 |

| RE2. I don’t think about work at all on vacation | –402 | –1.086 |

| RE3. I distance myself from my work on vacation. | –371 | –1.092 |

| RE5. I do relaxing things on vacation. | –719 | –862 |

| RE6. I use the time to relax on vacation. | –677 | –907 |

| RE7. I take time for leisure on vacation. | –646 | –788 |

| RE8. I learn new things on vacation. | –407 | –860 |

| RE9. I seek out intellectual challenges on vacation. | –224 | –870 |

| RE11. I do something to broaden my horizons on vacation. | –292 | –710 |

| RE12. I feel like I can decide for myself what to do on vacation. | –563 | –674 |

| RE13. I decide my schedule on vacation. | –556 | –742 |

| RE14. I determine for myself how I will spend my time on vacation. | –621 | –610 |

| RE15. I take care of things the way that I want them done on vacation. | –602 | –703 |

| O1. I usually manage one way or another. | –487 | –979 |

| O2. I am friend with myself. | –598 | –998 |

| O3. I feel that I can handle many things at a time. | –428 | –955 |

| O4. I am determined. | –373 | –893 |

| JS1. I am satisfied with my job after the vacation. | –345 | –534 |

| JS2. I love my job after vacation. | –458 | –658 |

| JS3. I enjoy my job after vacation. | –393 | –575 |

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.