1 Antai College of Economics and Management, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, 200030 Shanghai, China

Abstract

The rapid advancement of smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithms (STARA) has created uncertainties regarding employees’ job security and career prospects. Drawing on challenge–hindrance stressor theory and data from a two-wave survey of 319 corporate employees, this study develops a moderated dual-mediation model to investigate how STARA awareness influences employees’ time banditry behaviour through challenge and threat appraisals. It also examines the moderating role of prevention focus. The findings offer theoretical insights into the mechanisms and boundary conditions through which STARA awareness affects time banditry and provides practical guidance for organisations navigating employee responses during technological transitions.

Keywords

- STARA awareness

- time banditry behaviour

- challenging appraisal

- threatening appraisal

- prevention focus

Technological innovations driven by smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithms (STARA) have recently emerged as the cornerstone of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Tan et al, 2024). Among these, artificial intelligence (AI) demonstrates unparalleled advantages in data processing, precision decision-making, and cost control, thereby enabling its widespread application in diverse corporate production and management processes (Davenport and Ronanki, 2018). These AI-driven advancements have substantially enhanced organisational productivity and market competitiveness, garnering considerable attention across industries for their transformative potential (Morikawa, 2017). Consequently, the deep integration of AI has become a pivotal factor propelling organisational growth.

Despite these compelling benefits, the extensive implementation of AI technologies is not without challenges. Projections indicate that the proliferation of smart technologies, robotics, and algorithms may place approximately 77%, 47%, and 55% of the jobs in China, the United States, and Japan, respectively, at risk of replacement over the next two decades (David, 2017; Frey and Osborne, 2017; Xu and Wang, 2023). Although studies have consistently demonstrated the role of AI in improving organisational efficiency, its potential to displace human jobs has also introduced heightened psychological stress among employees. This perceived threat of job displacement is referred to as STARA awareness, which has emerged as a critical psychological construct in contemporary workplaces (Brougham and Haar, 2018), reflecting concerns and anxiety about job security and career development. As employees grapple with the uncertainties posed by AI, they may develop heightened STARA awareness, which triggers stress experience that affects both their psychological well-being and work behaviour. One notable manifestation of these stressors is time banditry behaviour, wherein employees engage in non-work-related activities during work hours (Bennett and Robinson, 2000). Such behaviour may be prompted by task simplification or shifts in work structures induced by new technologies, potentially undermining organisational performance (Harold et al, 2022).

Although prior studies have explored the influence of AI application on employee attitudes and behaviours (Arias-Pérez and Vélez-Jaramillo, 2022; Brougham and Haar, 2020; Ding, 2021; Ding, 2022; Kong et al, 2021; Li et al, 2019; Liang et al, 2022; Lingmont and Alexiou, 2020), the specific interrelationships among STARA awareness, stress appraisals, and time banditry behaviour remain underexplored. Addressing this gap requires a more nuanced understanding of how employees cognitively appraise these AI-induced pressures and, in turn, how such appraisals translate into behavioural outcomes. Challenge–hindrance stressor theory provides a valuable theoretical framework for understanding the distinct effects of different types of work stress on employee behaviour (LePine et al, 2005). Challenging appraisals are typically derived from tasks that encourage goal achievement, thereby fostering intrinsic motivation and work engagement. In contrast, threatening appraisals arise from burdens and uncertainties that employees perceive as uncontrollable and are strongly associated with negative emotional responses such as anxiety and exhaustion (Podsakoff et al, 2007). Beyond these stress responses, individual differences significantly influence employees’ STARA awareness and related stress experiences. For instance, regulatory focus theory posits that prevention focus, which is a psychological tendency to avoid risks and mitigate threats, becomes particularly salient in high-uncertainty environments (Higgins, 1997). In the realm of AI adoption, these theories together help elucidate why perceived job displacement threats drive certain employees to engage in time banditry behaviour.

Guided by these theoretical frameworks, the present study develops an integrated model to investigate the mechanisms linking STARA awareness and employees’ time banditry behaviour, with particular attention to the mediating role of cognitive stress appraisals and the moderating effect of prevention focus. In turn, it offers both theoretical and practical insights into how organisations can navigate technological transitions while safeguarding employees’ psychological well-being. Ultimately, elucidating the interplay among STARA awareness, stress responses, and adverse work behaviours enables firms to more effectively balance AI-driven innovations with supportive human resource strategies, thereby fostering sustainable growth in an evolving digital landscape.

STARA awareness, introduced by Brougham and Haar (2018), refers to employees’ subjective perceptions of the threats posed by AI technologies to their professional roles and career prospects. It encapsulates employees’ concerns about AI potentially replacing their jobs or negatively affecting their career development. This awareness encompasses not only employees’ basic understanding of AI technologies but also their evaluation of the long-term career risks associated with AI adoption (He et al, 2024).

With the progressive advancement of Industry 4.0, AI technologies have become a central driver of this revolution, rapidly permeating corporate production and management systems (Bankins et al, 2024). Research indicates that the remarkable advantages of AI in enhancing productivity and reducing costs have driven its widespread adoption while simultaneously intensifying employees’ concerns regarding job stability and future career development (Anthony et al, 2023). For instance, Frey and Osborne (2017) projected that more than half of occupations could face the risk of being replaced by AI within the coming two decades, further amplifying employees’ STARA awareness.

Several scholars have examined the psychological and behavioural effects of STARA awareness on employees. Brougham and Haar (2018) found that STARA awareness positively influences depression, cynicism, and turnover intention, while negatively affecting organisational commitment and career satisfaction. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that job insecurity mediates the relationship between STARA awareness and turnover intention, and this relationship is moderated by organisational culture, perceived organisational support, and a competitive climate (Brougham and Haar, 2020; Li et al, 2019; Lingmont and Alexiou, 2020). Furthermore, STARA awareness is closely associated with knowledge-hiding behaviour, job burnout, and job satisfaction (Arias-Pérez and Vélez-Jaramillo, 2022; Kong et al, 2021; Xu and Wang, 2023). In addition, Ding (2021, 2022) proposed a dual nature of STARA awareness, finding that it can enhance job engagement and innovative behaviour through challenging appraisals, while also promoting service innovation through intrinsic motivation (Liang et al, 2022). Collectively, these findings underscore the significant effects of STARA awareness on employees’ mental health and behavioural outcomes.

According to challenge–hindrance stressor theory, individuals determine their coping strategies based on their subjective evaluations of potential stressors (Folkman et al, 1986). Although employees may, to some extent, perceive AI as a controllable challenge and hold a positive attitude towards it, they may also become aware of the potential negative impact of AI applications on their job stability, responsibilities, and career prospects (Raisch and Krakowski, 2021). This uncertainty can diminish the likelihood that employees will evaluate such stressors as challenges. In such cases, employees may find it difficult to perceive the application of AI as an opportunity for personal growth (Mitchell et al, 2019). Employees will be instead more likely to perceive AI applications as reflecting an uncontrollable situation that exceeds their cognitive and coping resources, thereby reducing their challenging appraisal of the stressor (Ito and Brotheridge, 2003).

Conservation of resources (COR) theory further supports this perspective (Hobfoll, 1989). When individuals perceive resource depletion, they are more likely to experience negative psychological and emotional reactions, which, in turn, will hinder positive appraisals of environmental stressors (Morelli and Cunningham, 2012). Employees with heightened STARA awareness may feel that their skills and knowledge are inadequate to address the complexity and demands of AI technologies. This sense of resource depletion and anxiety diminishes their ability to appraise AI as a challenge, leading them to view it instead as an obstacle (Hobfoll, 2011). Furthermore, heightened emotional responses and threat perceptions impair employees’ capacity to adopt a positive perspective, thereby reducing the likelihood that they will perceive AI as an opportunity for growth (Ng and Feldman, 2012).

Therefore, although STARA awareness may stimulate employee motivation for learning and growth to a certain degree, elevated awareness is more likely to result in resource depletion, diminished control, and increased apprehension about the future. Collectively, these negative emotions ultimately lower employees’ challenging appraisals of AI.

Hypothesis 1a: STARA awareness negatively affects challenging appraisals.

Serving as highly efficient and cost-effective tools, AI technologies have been widely adopted across corporate settings while simultaneously raising employees’ concerns about job security (Presbitero and Teng-Calleja, 2023). According to challenge–hindrance stressor theory, when employees encounter external stressors they perceive as threats to their job stability, they conduct an initial subjective appraisal (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). Stressors deemed controllable are classified as challenges, whereas those perceived as uncontrollable and destructive are categorised as threats Specifically, threatening appraisals reflect employee perceptions of the impediments posed by external stressors, which are considered insurmountable through personal effort (Cavanaugh et al, 2000). Employees with heightened STARA awareness perceive AI as potentially replacing their jobs, disrupting established role boundaries, or creating a sense of disorientation, and are more likely to experience uncertainty and anxiety about their career prospects, and such appraisals often involve concerns regarding role ambiguity, job insecurity, and loss of control (Teng et al, 2024).

The rapid advancement of AI technologies introduces significant novelty and unpredictability, making it more difficult for employees to make accurate forecasts of their career trajectories, thus heightening their sense of loss of control over their career development (Brougham and Haar, 2020). In scenarios characterised by high STARA awareness, employees experience pronounced job insecurity, particularly when they perceive their skills as inadequate for adapting to technological advancements. Thus, they will be more inclined to evaluate AI as a threatening stressor (Dekker and Schaufeli, 1995). Specifically, heightened STARA awareness amplifies employee sensitivity to the disruptive and intrusive nature of technological progress. This results in the perception that AI may render existing job tasks obsolete or even lead to job loss, thereby diminishing employees’ sense of control over their future career development (Ashford et al, 1989). The novelty and disruptive attributes of AI further exacerbate role conflicts and anxiety, intensifying employees’ negative outlook on career stability. Ultimately, employees are more likely to perceive AI technologies as hindrances to their career advancement.

Hypothesis 1b: STARA awareness positively affects threatening appraisals.

Challenging and threatening appraisals represent distinct yet interrelated dimensions of cognitive evaluations, reflecting both the opportunities for growth and risks of failure inherent in stressors (Folkman, 1982). This duality underscores the possibility that STARA awareness can simultaneously evoke both types of appraisals depending on employees’ perceived resources and coping capacities (Bakker et al, 2003). From the perspective of the challenge–hindrance stressor framework, employees who perceive sufficient personal or organisational resources will be more likely to appraise STARA awareness as a challenge and interpret AI-induced changes as opportunities for skill development and career advancement. Conversely, when resources are perceived as inadequate, employees will be more inclined to appraise STARA awareness as a threat, which leads to heightened anxiety and resistance to change (LePine et al, 2004). However, these appraisals are not static and interact dynamically over time. COR theory suggests that resource depletion tends to amplify threat appraisals and potentially diminish the positive effects of challenging appraisals. Greater STARA awareness intensifies employees’ concerns regarding resource depletion, making them more likely to appraise AI’s application as a threatening stressor rather than a challenging one (Hobfoll, 2001). This dynamic interaction highlights the intrinsic relationship between challenging and threatening appraisals because shifts in resource availability or coping strategies can cause one appraisal to strengthen or weaken the other (Li et al, 2022). Ultimately, the interaction between challenging and threatening appraisals reveals the dual-faceted nature of STARA awareness. Although it has the potential to elicit adaptive and maladaptive responses simultaneously, the relative dominance of either appraisal is shaped by resource availability, organisational context, and individual characteristics.

In modern work environments, time banditry behaviour has emerged as an organisational management issue, which refers to employees engaging in non-work-related activities during work hours. Such behaviours are often seen as coping strategies for work-related stressors, particularly when employees face seemingly insurmountable threats (Gardner et al, 2005). As STARA awareness increases, employees may experience various stress appraisals resulting from the uncertainties and task simplifications associated with AI adoption, including challenging and threatening appraisals. According to challenge–hindrance stressor theory, when employees appraise stressors as controllable challenges, they are likely to adopt proactive coping strategies. Conversely, when they perceive stressors as uncontrollable threats, employees may resort to avoidance behaviours (LePine et al, 2016).

Challenging appraisals typically elicit positive responses and motivate employees to take proactive measures to overcome challenges, achieve personal growth, and enhance job performance (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004). Employees who make challenging appraisals are more likely to view AI as an opportunity to improve their skills and invest resources to address the stressors they face. According to COR theory, employees are less likely to engage in time banditry behaviour when focusing their resources on overcoming challenging stressors (Hobfoll and Lilly, 1993). Studies suggest that challenging appraisals are positively associated with productive workplace behaviours and fostering self-improvement and goal setting (Drach-Zahavy and Erez, 2002). Therefore, employees facing new challenges often devote their efforts to skill enhancement, thereby reducing the likelihood of time banditry behaviour.

In contrast, threatening appraisals occur when employees perceive stressors as uncontrollable, which hinders goal achievement and results in helplessness and emotional exhaustion (Edmondson and Lei, 2014). In threatening appraisal contexts, employees are more likely to perceive AI as an uncontrollable threat, eliciting negative emotions such as anxiety and frustration, which may drive them to engage in time banditry behaviour as an avoidance strategy. Research has shown that threatening appraisals are closely associated with counterproductive behaviours, absenteeism, and negative workplace attitudes (Bowling and Eschleman, 2010; Fu et al, 2021; Spector and Fox, 2002). And emotional exhaustion and dissatisfaction increase in threatening contexts, prompting employees to choose time banditry behaviour as a coping mechanism.

Hypothesis 2a: Challenging appraisals negatively affects employees’ time banditry behaviour.

Hypothesis 2b: Threatening appraisals positively affects employees’ time banditry behaviour.

In exploring the pathways through which STARA awareness influences employee behaviours, cognitive appraisal theory offers a valuable framework for understanding the mechanisms involved. This theory posits that individuals subjectively evaluate stressors as either challenges or threats, and that these appraisals determine their subsequent coping strategies (Podsakoff et al, 2007). In this study, challenging and threatening appraisals are examined as mediators in the relationship between STARA awareness and time banditry behaviour, which capture employees’ positive and negative responses to disruptions introduced by AI respectively.

Challenging and threatening appraisals significantly impact employee behaviour and psychological states (Lazarus, 1993). Research indicates that challenging appraisals are positively associated with constructive work attitudes, task proficiency, and organisational citizenship behaviours. In contrast, threatening appraisals are closely linked to emotional exhaustion, turnover intention, and counterproductive work behaviour (LePine et al, 2004). By incorporating these appraisals as mediating variables, this study aims to elucidate how different stress evaluations mediate the effects of STARA awareness on time banditry behaviour.

As an external stressor arising from technological advancements, STARA awareness often leads employees to perceive their skills and knowledge as inadequate to adapt to rapid technological changes, thereby undermining their challenging appraisals. According to COR theory, when individuals perceive resource threats, they tend to reduce their positive engagement to avoid further depletion of resources (Penney et al, 2011). Challenging appraisals represent employee perceptions of stressors as opportunities for personal growth; however, as STARA awareness increases, employees may find it increasingly difficult to view AI as a challenge, and decrease their engagement with work tasks in response. Studies have shown that when challenging appraisals decrease, employees are more likely to engage in counterproductive behaviours (Galluch et al, 2015; Kahn, 1990). Ding (2022) observed that employees facing challenging tasks typically choose proactive responses, such as acquiring new skills to overcome obstacles. Thus, with heightened STARA awareness, employees may shift away from challenging appraisals and resort to time banditry behaviour as an avoidance strategy.

Conversely, threatening appraisals occur when employees perceive stressors as uncontrollable and believe that they are incapable of achieving their goals, which results in emotional exhaustion and feelings of helplessness (Gerich, 2017). In the context of threatening appraisals, STARA awareness often raises concerns about career uncertainty and feelings of frustration, leading employees to view AI as an insurmountable threat (Yin et al, 2024). Research suggests that threatening stressors are strongly associated with counterproductive behaviours, absenteeism, and negative workplace attitudes. For instance, threatening appraisals can prompt employees to adopt avoidance strategies such as time banditry behaviour to escape work-related stressors (Henle et al, 2010). This mediating mechanism suggests that threatening appraisals channel the negative effects of STARA awareness into employee behaviour, making employees more likely to engage in time banditry behaviour when confronted with AI disruptions.

In summary, challenging and threatening appraisals exert opposing effects on the pathway between STARA awareness and time banditry behaviour. An increase in STARA awareness may reduce employees’ challenging appraisals, diminishing their active performance, while heightened threatening appraisals could drive employees toward avoidance behaviour.

Hypothesis 3a: Challenging appraisals mediate the relationship between STARA awareness and time banditry behaviour. Higher levels of STARA awareness reduce challenging appraisals, potentially increasing time banditry behaviour.

Hypothesis 3b: Threatening appraisals mediate the relationship between STARA awareness and time banditry behaviour. Higher levels of STARA awareness strengthen threatening appraisals, potentially increasing time banditry behaviour.

Regulatory focus theory suggests that individuals adopt different coping strategies when confronted with stressors (Kark and Van Dijk, 2007). These strategies are based on their regulatory focus, categorised as prevention focus and promotion focus. A prevention focus emphasises avoiding losses and maintaining safety, prompting individuals to adopt conservative strategies in stressful situations. In contrast, a promotion focus prioritises achievement and growth, encouraging individuals to pursue innovative opportunities (Lin and Johnson, 2015).

Although regulatory focus theory encompasses both prevention and promotion orientations, the effects differ across contexts. Brockner and Higgins (2001) noted that prevention and promotion focus are relatively independent and that prevention focus is particularly effective in contexts involving career threats (Brockner and Higgins, 2001). Further research by Lanaj et al (2012) demonstrated that prevention focus effectively guides individuals to avoid losses in high-risk, uncertain environments such as those created by AI (Lanaj et al, 2012). In contrast, a promotion focus is better suited to contexts that provide clear growth opportunities or innovative tasks. Given that STARA awareness predominantly generates perceptions of career insecurity and loss of control, a prevention focus aligns more closely with employees’ psychological needs (Carver and Scheier, 1998). This alignment provides a better explanation of the moderating role of prevention focus in the relationship between STARA awareness and stress appraisal.

STARA awareness and a high prevention focus are more likely to motivate employees to choose strategies aimed at maintaining the status quo and avoiding risks. A high prevention focus can help employees maintain stability under stress, making them more able to manage AI-related demands constructively (Faddegon et al, 2008). This dynamic partially mitigates the negative effect of STARA awareness on challenging appraisals. Specifically, the higher an employee’s prevention focus, the weaker the negative effect of STARA awareness on challenging appraisals, which enables employees to remain engaged in their work despite the challenges posed by AI.

Conversely, risk-avoidance tendencies emphasised by a prevention focus may amplify threatening appraisals triggered by heightened STARA awareness. Employees with a high prevention focus are more likely to perceive AI as a threat, reinforcing their negative evaluations of AI-related stressors (Hobfoll, 2001). This indicates that employees with a strong prevention focus will be inclined to adopt avoidance strategies to maintain safety in stressful contexts, thereby exacerbating the positive relationship between STARA awareness and threatening appraisals. Consequently, when an employee’s prevention focus is high, STARA awareness is more likely to elicit threatening appraisals, thereby intensifying negative perceptions of AI.

Hypothesis 4a: Prevention focus moderates the relationship between STARA awareness and challenging appraisals. Specifically, higher levels of prevention focus weaken the negative correlation between STARA awareness and challenging appraisals.

Hypothesis 4b: Prevention focus moderates the relationship between STARA awareness and threatening appraisals. Specifically, higher levels of prevention focus strengthen the positive correlation between STARA awareness and threatening appraisals.

Individuals with a prevention focus tend to adopt conservative strategies to avoid risks. Thus, under the influence of STARA awareness, a high prevention focus may amplify or mitigate the effects of stress appraisals on employee behaviour (Gorman et al, 2012). Specifically, employees with a strong prevention focus are more likely to exhibit avoidant behaviours in the threatening appraisal pathway, whereas they may show greater stability towards proactive behaviours in the challenging appraisal pathway. When employees face STARA awareness with a heightened prevention focus, their propensity to cope with stress actively is better preserved, thereby diminishing the mediating effects of challenging appraisal. Individuals with a prevention focus are inclined to maintain the status quo and avoid excessive resource investment to address uncontrollable risks (Brockner and Higgins, 2001). Therefore, for employees with a high prevention focus, the negative influence of STARA awareness on challenging appraisal is mitigated, further weakening its mediating effects.

In the threatening appraisal pathway, a high level of prevention focus amplifies the negative responses triggered by STARA awareness, further increasing the likelihood of time banditry behaviour. A prevention focus emphasises safety concerns, making employees more prone to feeling helpless and frustrated when confronted with job uncertainty (Neubert et al, 2008). This psychological state exacerbates the positive impact of STARA awareness on threatening appraisal, further amplifying the negative mediating effect. This implies that employees with a higher prevention focus are more likely to perceive stressors as insurmountable threats under STARA awareness, increasing their reliance on time banditry behaviour as a negative coping mechanism.

In summary, this study proposes that prevention focus moderates the mediating effects of stress appraisals on the relationship between STARA awareness and time banditry behaviour. Specifically, a high prevention focus weakens the mediating effects of challenging appraisal in the STARA awareness pathway while amplifying the mediating effects of threatening appraisal.

Hypothesis 5a: Prevention focus negatively moderates the indirect effect of challenging appraisal on the relationship between STARA awareness and time banditry behaviour; the higher the prevention focus, the weaker the mediating effect of challenging appraisal.

Hypothesis 5b: Prevention focus positively moderates the indirect effect of threatening appraisal on the relationship between STARA awareness and time banditry behaviour; the higher the prevention focus, the stronger the mediating effect of threatening appraisal.

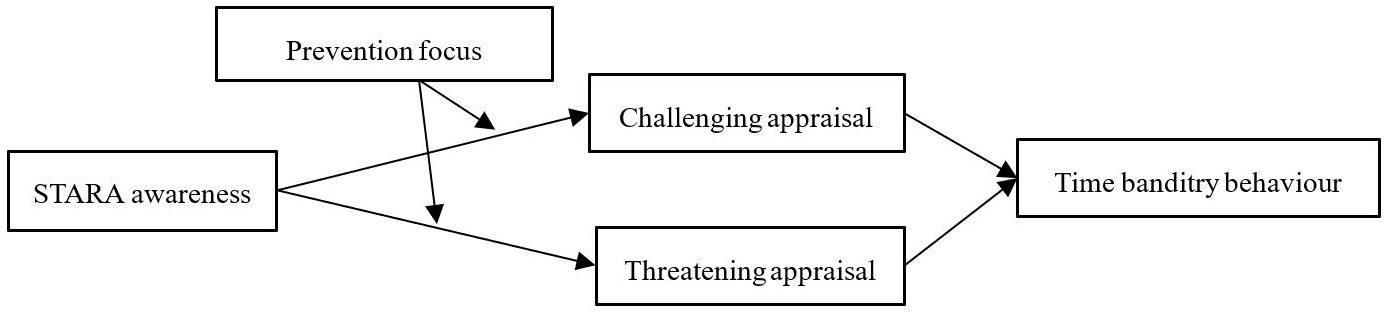

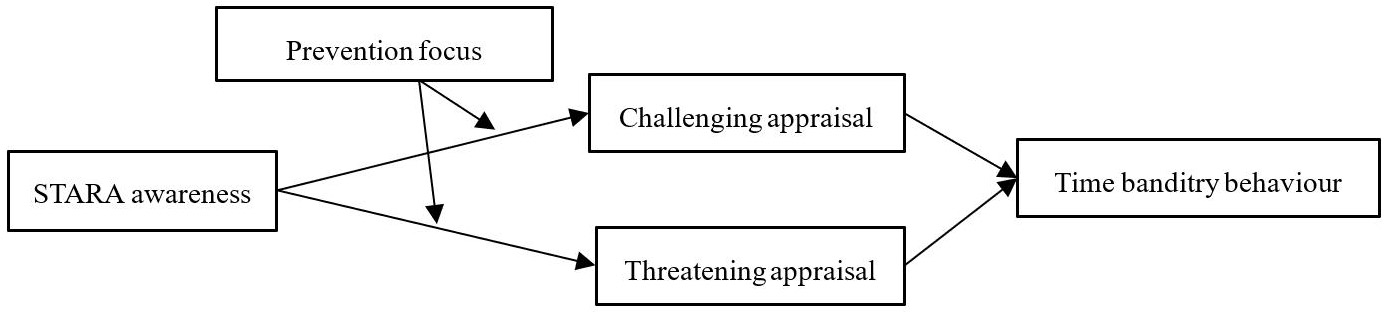

The model used in this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Research model.

This study collected data through the Credamo platform by distributing online surveys to employees working for organisations that apply AI technologies. The participants were drawn from various industries across different regions of the country. To mitigate the adverse effects of common method variance, a longitudinal approach was used to collect data at two timepoints with an interval of two weeks. At the first timepoint (T1), participants provided information on demographic variables, STARA awareness, and the two types of stress appraisals. At the second timepoint (T2), participants reported their time banditry behaviour and prevention focus. To ensure reliable data, the survey emphasised anonymity and confidentiality, stating that the information would be used for this study only.

In the first wave, 537 questionnaires were distributed, of which 482 were valid. In the second wave, 482 follow-up questionnaires were distributed, and 373 valid responses were returned. After excluding questionnaires with abnormal completion times and careless responses, 319 valid paired questionnaires were retained for analysis.

The variables in this study were measured using well-established scales that were either directly adopted or adapted. Following the translation-back translation method, English scales were converted into Chinese versions. Responses were rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

STARA awareness: The independent variable was measured using the four-item scale

developed by Brougham and Haar (2018). A sample item is, ‘I think my job

might be replaced by artificial intelligence’ (Cronbach’s

Challenging appraisal and threatening appraisal: The mediating variables were

measured using scales adapted from Mitchell et al (2019). Specifically,

challenging appraisal was assessed using four items, with a sample item as ‘For

me, the application of AI in work presents an opportunity for a challenge’

(Cronbach’s

Time banditry behaviour: The dependent variable was measured using a three-item

scale by Bennett and Robinson (2000). A sample item is ‘I handle personal

matters during work hours’ (Cronbach’s

Prevention focus: The moderating variable was measured using a nine-item scale

by Neubert et al (2008). A sample item is ‘I do my best to avoid mistakes in

my work’ (Cronbach’s

Control variables: Based on existing research, demographic variables such as

gender, age, education, and job level were included as control variables as they

may influence time banditry behaviour (Martin et al, 2010). Additionally,

job characteristics can influence employees’ psychological states in the

workplace, thereby affecting their time banditry behaviours (Hackman and Oldham, 1975; Harold et al, 2022). Consequently, this study used task

significance to capture job characteristics, adapting the Job Characteristics

Questionnaire developed by Hackman and Oldham (1975), which comprises four

items. A representative item is, ‘My work is meaningful’ (Cronbach’s

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 27.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) with the PROCESS macro (Version 4.2, Andrew F. Hayes, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA) and Mplus (Version 8.10, Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA) software. Mplus was used to conduct confirmatory factor and common method variance analyses. SPSS was employed to perform reliability analysis, descriptive statistics, and correlation analysis and to examine the relationships between variables through hierarchical regression analysis. Finally, the PROCESS macro was used to test the parallel and moderated mediation effects.

The industry distribution of the study sample demonstrated significant diversity, encompassing a range of both traditional and emerging sectors. Specifically, the manufacturing, software and information technology, and education sectors constituted 21.0%, 7.8%, and 8.5% of the sample, respectively. Furthermore, industries such as finance (4.1%), wholesale and retail trade (3.1%), services (2.8%), and accommodation and catering (2.2%) were included to a notable extent.

The final sample included 118 male (37.0%) and 201 female (63.0%) participants. The average age of the participants was 30.66 years (SD = 6.902), with the majority (92.5%) aged between 20 and 40 years and 7.5% aged over 40 years. Regarding educational level, 2.8% had a high school diploma or below, 11.6% had an associate degree, 69.0% held a bachelor degree, and 16.6% held a master degree or higher. In terms of job level, general staff constituted the largest proportion at 47.6%, followed by first-line (24.1%) and middle-level (22.6%) managers, and senior managers accounted for the smallest proportion, comprising only 5.6% of the sample.

To examine the discriminant validity of the scales and evaluate the fit between

the data and the proposed model, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted with

five variables: STARA awareness, challenging appraisal, threatening appraisal,

time-banditry behaviour, and prevention focus. The results presented in Table 1

indicate that the five-factor model demonstrated significantly better fit indices

than competing alternative models (

| Model | df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI | ||

| 5 factors | 716.761 | 242 | — | 0.078 | 0.087 | 0.903 | 0.889 |

| 4 factors | 916.062 | 246 | 199.301 (4)*** | 0.092 | 0.094 | 0.863 | 0.846 |

| 3 factors a | 1208.369 | 249 | 491.608 (7)*** | 0.110 | 0.102 | 0.804 | 0.783 |

| 3 factors b | 2079.664 | 249 | 1362.903 (7)*** | 0.152 | 0.170 | 0.626 | 0.586 |

| 2 factors | 2371.825 | 251 | 1655.064 (9)*** | 0.163 | 0.174 | 0.567 | 0.524 |

| 1 factor | 2608.388 | 252 | 1891.627 (10)*** | 0.171 | 0.178 | 0.519 | 0.473 |

Note: N = 319; ***p

STARA, STARA awareness; PF, Prevention focus; CA, Challenging appraisal; TA, Threatening appraisal; TB, Time banditry behaviour; df, degrees of freedom; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; SRMR, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index.

Five-factor model (STARA, PF, CA, TA, TB), Four-factor model (STARA, PF, CA+TA, TB); Three-factor model a (STARA+CA+TA, PF, TB); Three-factor model b (STARA +PF, CA+TA, TB); Two-factor model (STARA+PF+CA+TA, TB); Single-factor model (STARA+PF+CA+TA+TB).

The means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of the variables

are shown in Table 2. The results indicated that STARA awareness was

significantly negatively correlated with challenging appraisal (r =

–0.464, p

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 1. Gender | — | |||||||||

| 2. Age | –0.050 | — | ||||||||

| 3. Education | 0.068 | –0.023 | — | |||||||

| 4. JL | 0.032 | 0.463** | 0.192** | — | ||||||

| 5. JC | –0.099 | 0.020 | 0.039 | 0.178** | (0.893) | |||||

| 6. STARA | 0.083 | –0.126* | –0.176** | –0.315** | –0.134* | (0.952) | ||||

| 7. CA | –0.126* | 0.099 | 0.083 | 0.189** | 0.340** | –0.464** | (0.806) | |||

| 8. TA | 0.087 | –0.181** | –0.025 | –0.299** | –0.101 | 0.756** | –0.535** | (0.897) | ||

| 9. TB | 0.130* | –0.295** | 0.058 | –0.335** | –0.290** | 0.385** | –0.404** | 0.444** | (0.815) | |

| 10. PF | 0.074 | –0.019 | –0.111* | –0.103 | –0.201** | 0.226** | –0.106 | 0.187** | 0.110* | (0.893) |

| Mean | — | 30.665 | — | — | 5.158 | 3.335 | 5.536 | 2.795 | 2.660 | 5.451 |

| SD | — | 6.902 | — | — | 1.194 | 1.604 | 0.853 | 1.301 | 1.200 | 0.950 |

Note: N = 319, *p

JL, Job level; JC, Job characteristics; PF, Prevention focus; SD, Standard Deviation.

As the data in this study were collected through employee self-reports, precautions were taken to mitigate the influence of common method variance (CMV) (Podsakoff et al, 2003). First, Harman’s single-factor test was employed, and the results indicated that the largest factor explained 30.051% of the variance, which is below the 40% threshold (Harman, 1976). However, owing to the limited sensitivity of this method (Zhou and Long, 2011), a model was constructed that incorporated a common method factor and compared to the five-factor model.

As Table 3 shows, the results revealed that the decreases in RMSEA and SRMR were less than 0.05, whereas the increases in CFI and TLI were less than 0.1 (Hu and Bentler, 1999). This indicated that the model did not improve significantly after the common method factor was included. Therefore, it can be concluded that the common method variance in this study was within an acceptable range and did not substantially affect the data analysis results.

| Model | df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI | ||

| Model without CMV factor | 716.761 | 242 | 2.962 | 0.078 | 0.087 | 0.903 | 0.889 |

| Model with CMV factor | 376.597 | 219 | 1.720 | 0.047 | 0.068 | 0.968 | 0.959 |

| Model changes | –340.164 | –23 | –1.242 | –0.031 | –0.019 | 0.065 | 0.070 |

CMV, common method variance.

First, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to examine the

relationships among STARA awareness, challenging appraisal, threatening

appraisal, and time banditry behaviour. The results are summarised in Table 4.

After controlling for demographic variables, Model 6 indicated that STARA

awareness significantly and positively predicts time banditry behaviour

(

| Variable | Challenging appraisal | Threatening appraisal | Time banditry behaviour | |||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |||

| Control Variables | ||||||||||

| Gender | –0.178 | –0.108 | 0.236 | 0.045 | 0.243 | 0.171 | 0.140 | 0.160 | ||

| Age | 0.005 | 0.005 | –0.009 | –0.010 | –0.030** | –0.031*** | –0.029** | –0.028** | ||

| Education | 0.074 | 0.007 | 0.045 | 0.229** | 0.185* | 0.254** | 0.256** | 0.196* | ||

| Job level | 0.097 | –0.010 | –0.376*** | –0.083 | –0.295*** | –0.185* | –0.188** | –0.164* | ||

| Job characteristics | 0.220*** | 0.199*** | –0.047 | 0.009 | –0.240*** | –0.219*** | –0.161** | –0.221*** | ||

| Independent Variable | ||||||||||

| STARA awareness | –0.223*** | 0.609*** | 0.229*** | 0.164*** | 0.075 | |||||

| Mediating Variables | ||||||||||

| Challenging appraisal | –0.292*** | |||||||||

| Threatening appraisal | 0.253*** | |||||||||

| R2 | 0.147 | 0.299 | 0.103 | 0.593 | 0.218 | 0.300 | 0.330 | 0.331 | ||

| F | 10.746*** | 22.217*** | 7.150*** | 75.916*** | 17.468*** | 22.298*** | 21.906*** | 21.960*** | ||

| 0.153 | 0.491 | 0.082 | 0.030 | 0.031 | ||||||

| 68.061*** | 376.819*** | 36.533*** | 13.985*** | 14.251*** | ||||||

Note: N = 319, *p

Model 7 indicated that challenging appraisal significantly negatively affects

time banditry behaviour (

In Model 7, the regression coefficient effect of STARA awareness on time

banditry behaviour decreased but remained significant (

The PROCESS macro in SPSS was used to test the parallel mediating effects, incorporating both challenging and threatening appraisals into the model. The bootstrap method was employed with 5000 random samples to verify the significance of the two mediation paths. And Table 5 presents the results.

| Model | SE | Bootstrap LLCI | Bootstrap ULCI | |

| Direct effect | 0.065 | 0.055 | –0.043 | 0.173 |

| Indirect effect (Challenging appraisal) | 0.048 | 0.024 | 0.006 | 0.102 |

| Indirect effect (Threatening appraisal) | 0.116 | 0.045 | 0.027 | 0.206 |

| Total effect | 0.230 | 0.038 | 0.155 | 0.304 |

LLCI, Bootstrap Lower-Level Confidence Interval; Bootstrap ULCI, Bootstrap Upper-Level Confidence Interval; SE, Standard Error.

The results indicated that the indirect effect of STARA awareness on time

banditry behaviour through challenging appraisal is

The moderating effect of prevention focus was tested using hierarchical

regression analysis, and the results are shown in Table 6. The results of Model

11 indicated that a prevention focus significantly positively moderates the

relationship between STARA awareness and challenging appraisal (

| Variable | Challenging appraisal | Threatening appraisal | ||||||

| Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 | Model 13 | Model 14 | |||

| Control Variables | ||||||||

| Gender | –0.178 | –0.113 | –0.089 | 0.236 | 0.042 | 0.032 | ||

| Age | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.006 | –0.009 | –0.010 | –0.011 | ||

| Education | 0.074 | 0.012 | 0.021 | 0.045 | 0.233** | 0.229** | ||

| Job level | 0.097 | –0.009 | –0.010 | –0.376*** | –0.083 | –0.083 | ||

| Job characteristics | 0.220*** | 0.206*** | 0.187*** | –0.047 | 0.014 | 0.021 | ||

| Independent Variable | ||||||||

| STARA awareness | –0.228*** | –0.251*** | 0.605*** | 0.614*** | ||||

| Moderating Variable | ||||||||

| Prevention focus | 0.048 | 0.179** | 0.036 | –0.016 | ||||

| Interaction Effects | ||||||||

| STARA awareness * Prevention focus | 0.139*** | –0.054 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.147 | 0.302 | 0.341 | 0.103 | 0.594 | 0.597 | ||

| F | 10.746*** | 19.219*** | 20.077*** | 7.150*** | 65.028*** | 57.332*** | ||

| 0.155 | 0.039 | 0.492 | 0.003 | |||||

| 34.630*** | 18.506*** | 188.327*** | 1.998 | |||||

Note: N = 319, *p

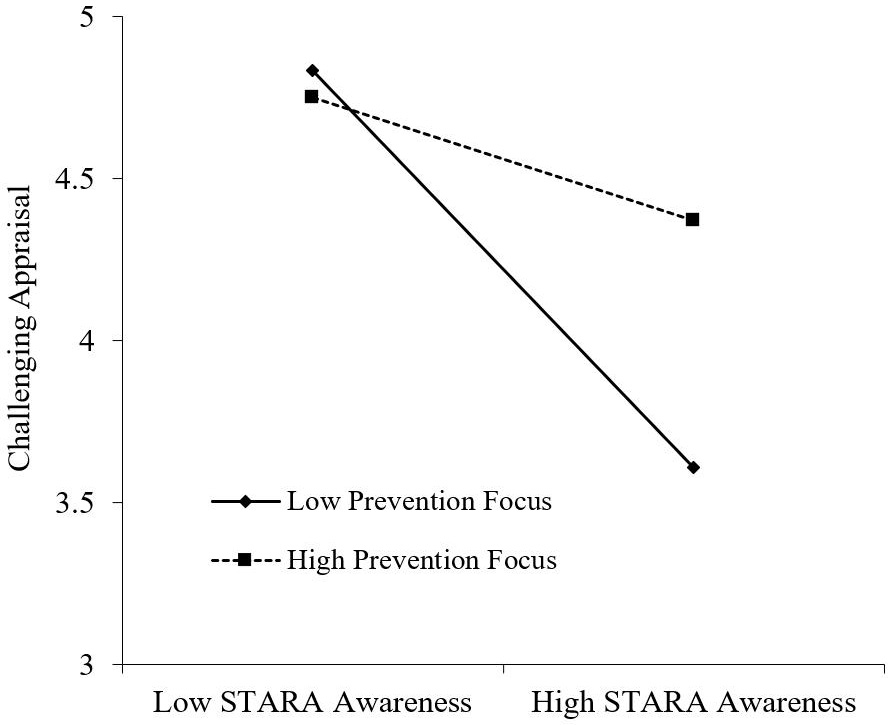

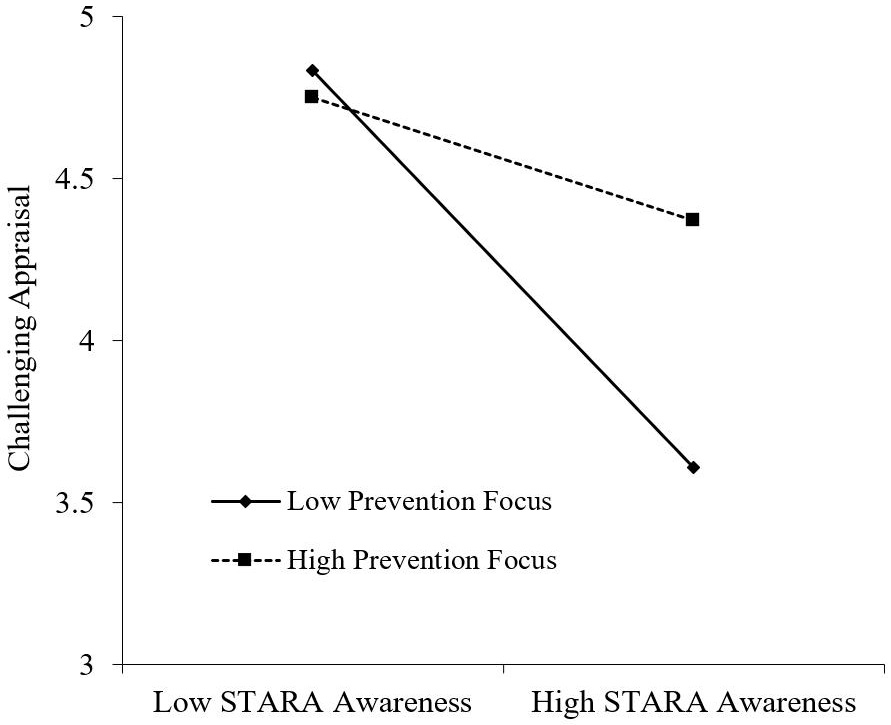

To provide a clearer view of the significance of the moderating effects, a

simple slope analysis was conducted, and the moderating effect diagram was

plotted (Fig. 2). The figure shows that, when employees’ prevention focus is low,

the negative correlation between STARA awareness and challenging appraisal is

stronger (

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Moderating effect test of prevention focus.

To examine the mediating role of challenging appraisal in the relationship between STARA awareness and time banditry behaviour at different levels of prevention focus, the bootstrapping method was used for analysis (Edwards and Lambert, 2007). The results are shown in Table 7.

| Prevention focus | SE | Bootstrap LLCI | Bootstrap ULCI | ||

| The mediating effect of challenging appraisal | Low (M-1SD) | 0.112 | 0.042 | 0.045 | 0.213 |

| Middle (M) | 0.073 | 0.028 | 0.027 | 0.136 | |

| High (M+1SD) | 0.035 | 0.019 | 0.008 | 0.082 | |

| Index | –0.041 | 0.018 | –0.088 | –0.013 | |

At low levels of prevention focus, the indirect effect of STARA awareness on

time banditry behaviour through challenging appraisal was significant

(

Grounded in challenge–hindrance stressor theory, this study investigates the mechanism through which STARA awareness influences employees’ time banditry behaviour via two distinct stress appraisals, challenging appraisal and threatening appraisal, and examines the moderating role of prevention focus. The findings reveal that, first, stress cognitive appraisal acts as a critical mediating mechanism, determining whether STARA awareness functions as a motivator or hindrance to time banditry behaviour. Second, a prevention focus negatively moderates the relationship between STARA awareness and challenging appraisal, thereby weakening its mediating effect. In addition, the non-significance of the threatening appraisal pathway may be attributable to the adaptability of prevention focus, situational differences, the dual nature of STARA awareness, and the influence of cultural and organisational contexts.

To begin with, study extends the theoretical framework of STARA awareness by examining not only its direct impact on employee behaviour but also its dual-path influence through challenging and threatening appraisals. By highlighting the dual attributes of AI’s impact, representing both threats and opportunities, this study broadens the current understanding of STARA awareness and offers a novel theoretical framework for exploring the psychological and behavioural effects of AI technology in diverse organisational contexts.

Moreover, this study enriches challenge–hindrance stressor theory by applying it to the context of AI impact. This theory has been traditionally used in research on stressors in work tasks, and this study demonstrates its applicability to AI technological stressors, revealing how different stressor pathways indirectly influence employee behaviour.

Furthermore, this study incorporates regulatory focus theory into high-uncertainty technological contexts by introducing prevention focus as a moderating variable. This approach deepens the current understanding of how a regulatory focus shapes employee responses to technological challenges. This study’s findings validate the moderating role of prevention focus in the challenging appraisal pathway, expanding its application to employees’ psychological coping mechanisms under technological stress. Simultaneously, the unsupported hypothesis highlights the context-dependent nature of regulatory focus, offering valuable directions for future research on its moderating effects in other environmental settings.

First and foremost, attention should be paid to employees’ STARA awareness, and this awareness should be appropriately guided. Companies must acknowledge the psychological impact of AI applications on employees and mitigate concerns regarding job security through regular communication and training. For example, offering AI-related skills training can help employees adapt to technological changes and reduce negative behaviours associated with hindrance stress.

Furthermore, management should leverage incentive systems to enhance challenging appraisal. This study found that challenging appraisal negatively mediates the relationship between STARA awareness and time banditry behaviour, suggesting that when employees perceive AI as a career development opportunity, their time management and work focus improve. To encourage such perceptions, companies can implement reward systems, provide growth opportunities, and promote positive attitudes towards technological change, thereby reducing negative behaviours among employees.

Management practices should also consider employees’ regulatory focus. This study’s findings highlight that prevention focus moderates the challenging appraisal pathway but not the hindrance appraisal pathway. For employees with a high prevention focus, companies can provide greater security such as clear promotion paths or job stability to reduce their hindrance appraisal of AI. Conversely, for employees with a promotion focus, developmental incentives can further reinforce their acceptance of technological change and strengthen their challenging appraisal.

Finally, organisations should foster a supportive organisational culture, which plays a crucial role in helping employees navigate uncertainty. Managers should cultivate a supportive work environment by providing the necessary resources and establishing counselling mechanisms. These efforts can enhance employees’ job security and work engagement, ultimately reducing time banditry behaviour.

Despite its theoretical and empirical contributions, this study has several limitations that provide directions for future research. First, the data source relied on self-reports from employees, which may have introduced a social desirability bias and common method variance. Although a time-separated longitudinal data collection method was used to mitigate these effects, the potential influence of consistent data sources on the results could not be eliminated. Future studies could address this limitation by employing multisource data collection methods to enhance the validity of the findings.

Second, to maintain the simplicity and focus of the hypothesised model, the potential interaction between challenging and threatening appraisals was not empirically tested. Although theoretical analysis supports the possibility of such an interaction, the lack of empirical evidence limits a comprehensive understanding of their intrinsic relationship. Future research should empirically examine how these two appraisal dimensions interact under varying contextual or moderating conditions, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the multidimensional appraisal mechanisms that individuals use in the face of stressors.

Third, although this study incorporated control variables, such as job level and characteristics, to improve explanatory power, other relevant factors may have been overlooked. For example, organisational culture or additional task characteristics can significantly influence time banditry behaviour and stress appraisals. Future research could expand the range of the control variables and explore their potential moderating or mediating roles in the proposed model. Incorporating a broader set of variables would enhance the robustness of the findings and provide deeper insights into the mechanisms underlying stress appraisal and employee behaviour.

Finally, this study primarily used cross-sectional data, which limits its ability to capture long-term dynamics. Future research could employ longitudinal designs to track the evolution of employees’ STARA Awareness, particularly in the context of rapid technological change. Such studies could examine how employee stress appraisals and behavioural patterns adapt to long-term technological innovation, offering a valuable perspective on the sustained impact of AI on employee behaviour.

STARA, Smart technology, Artificial Intelligence, Robotics, and Algorithms; AI, Artificial Intelligence; COR, Conservation of Resources (Theory); JL, Job Level; JC, Job Characteristics; CA, Challenging Appraisal; HA, Threatening Appraisal; TB, Time Banditry Behavior; PF, Prevention Focus; CFA, Confirmatory Factor Analysis; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; SRMR, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index; M, Means; SD, Standard Deviation; CMV, Common Method Variance;

The authors confirm full ownership and rights to the data used in this study. The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

YL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization. JG: Investigation, Validation, Writing—Review & Editing, Project Administration. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

We sincerely thank all the participants who contributed their time and effort to this study. We are also grateful for the support and encouragement provided by colleagues and peers during the research and writing process. The constructive feedback received during the review process has been invaluable in improving the quality of this manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/JEEMS38820.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.