1 Department of Agricultural Management and Leadership, Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences (MATE), H-2100 Gödöllő, Hungary

2 Department of Economics and International Economics, Ludovika University of Public Service, H-1083 Budapest, Hungary

3 Department of Economics and Management, Kodolányi János University, H-1117 Budapest, Hungary

4 Department of Human Resource Management, University of Graz, A-8010 Graz, Austria

5 Department of International Management, Johannes Kepler University Linz, A-4040 Linz, Austria

6 Savaria Department of Business Economics, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, H-1088 Budapest, Hungary

7 Department of Management, J. Selye University, SK-94501 Komárno, Slovakia

8 Department of Economics and Business Administration in Hungarian Language, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Babeș-Bolyai University, 400591 Cluj-Napoca, Romania

9 Department of Corporate Leadership and Marketing, Széchenyi István University, H- 9026 Győr, Hungary

10 Department of Management and Organization, University of Sarajevo, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Hercegovina

Abstract

This study addresses changes in human resource management (HRM) practices of six Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries during the COVID-19 pandemic by highlighting similarities and differences across the countries. We indicated the growing significance of the human factor while also pointing out significant differences between organisations and contexts. COVID-19 intensified changes affecting individuals, organizations and society–especially in the field of HR which may signal a paradigm shift in HR operations.

Keywords

- human resource management (HRM)

- pandemic

- crisis management

- human factor

- Central and Eastern Europe (CEE)

- organisational culture

The recent COVID-19 pandemic led to various changes in the world of work. The pandemic has influenced and transformed the composition and importance of human resource management (HRM) tasks strategically, tactically and operationally (Komm et al, 2021). Throughout the pandemic years, experience and understanding of novel HRM problems and their solutions has gradually changed (Ancillo et al, 2023). Recent studies have demonstrated that caring HRM practices (Bešić et al, 2024), which increased well-being, security measures, and shared administration (combining administrative activities into a centralised ‘hub’), were the most frequently implemented strategies to address the pandemic’s challenges (Chen, 2021; Hamouche, 2021).

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has also had a negative impact on human resources (Dániel et al, 2021), causing labour market inequalities and conflicts of interest (Butterick and Charlwood, 2021). Previously less frequently used solutions (working from home, reduced working hours, digital communication) have come to the fore (Lennert, 2020; Lipták, 2021). Work style (Agrawal et al, 2020), communication (Collings et al, 2021a) and the attitude of HRM professionals to employees have changed (Newman et al, 2023). Therefore, the pandemic has accelerated the transformation of theory and practice (Swoboda, 2020). It has become clear that the convergence of strategic and operational functions will pave the way for the future direction of HRM development (Collings et al, 2021a; Collings et al, 2021b).

Following the aftermath of COVID-19, HRM has strengthened its position in organisational hierarchical systems in both the public and private sectors (Harbert, 2021). The pandemic also underscored that technology had emerged as a crucial and integral element in the realms of management and HRM functions (Fernández et al, 2023). Many of the developments in the working environment, including working from home and remote working, are set to continue after COVID-19 (Sanz, 2022; Stolz, 2024).

Several studies have examined the similarities and differences in HRM responses during the COVID-19 pandemic, with some focusing on larger groups across various country contexts (Mayrhofer et al, 2021, 2023). These studies span multiple countries, as seen in the works of Arosha et al (2021), Bednarikova and Kostalova (2022), Gajewska (2023), PWC (2023), and Hirsch et al (2023). Other authors (Budhwar and Cumming, 2020) believe that the COVID-19 crisis brought to the fore the international nature of the problem area and the interconnectedness of the entire world. Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that due to the above-mentioned points, different countries utilized numerous legal, administrative, educational and other governmental solutions to achieve similar desired results (Babbar and Gupta, 2021; UN, 2022).

Still, it is unclear how the changes in HRM have unfolded in different contexts throughout the pandemic and what this means for the further development of HRM as a corporate function.

This article explores how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected HRM and presents the steps that organisations have taken to address the impact of the pandemic in six countries in Central and Central-Eastern Europe (CE and CEE), namely Austria (AT), Bosnia and Herzegovina (BA), Bulgaria (BG), Hungary (HU), Romania (RO), and Slovakia (SK). While the countries in the region differ significantly (PWC, 2023), they represent important examples in a region with differing economic developments and can thus show how HRM has changed due to the pandemic in high-, middle- and low-income countries in Europe. A case in point is the implementation of caring HRM practices (Bešić et al, 2024) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which was reinforced to tackle the challenges posed by the pandemic. In the following section we have also attempted to address the contextual nature of HRM in greater detail with regard to previous crises and the effects of the pandemic on HRM in the region.

Numerous publications provide the theoretical underpinnings of HR’s contextual influence (Becker and Huselid, 2006; Boxall and Purcell, 2016; Ulrich, 1997).

In this article, we first address the changes in HRM during the pandemic before explaining our methodology, results and discussion. We show that HRM has changed across the regions, albeit in different ways. Our findings highlight that a significant part of the responding organisations regarded COVID-19 as an opportunity.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the HRM function had undergone changes in the past few years. Human resource management draws from a broad perspective of social sciences, especially behavioural ones such as psychology, sociology, and economics. The social sciences, and HRM within it, are characterized by a paradigmatic division (Primecz, 2008). Examining trends in HRM reveals a shift from previous administration-productivity-collective bargaining orientated approaches (Barney, 1991; Hernaus et al, 2019), to a focus on attracting, managing, nurturing and retaining talent as the most critical issues (Cayrat and Boxall, 2023). As a result, new paradigms emerge, and new rules of the game have to be reinvented.

Traditional HRM primarily created the organization’s administration policy (Ahammad, 2017). In contrast, current HRM must focus on employee development (Ulrich and Brockbank, 2015), respond to their needs, and act as a bridge between employers and employees (Adamovic, 2017). The role of HRM in the current scenario has increased in value, particularly in employee engagement, development, and talent retention (Bock, 2015; Randstad, 2024). As a result of the changed environment and conditions, a shift in the centre of gravity is taking place in HRM. In fact, HRM is no longer merely a function, but a strategic partner in value creation and addition (Jo et al, 2023).

The classic form of strategic HRM was based on the assumption that HRM practices applied within companies were relatively homogeneous (Huselid, 1995). Lepak and Snell (1999) were among the first to differentiate strategic HRM practices for different employee groups. The pandemic highlighted the importance of the role of employees (Haque, 2023). Inadequate corporate responses may have harmed them. The pandemic also showed the importance of customers as organisations and as stakeholders (Hea and Harris, 2020)—this is often taken for granted in management research, but rarely in HRM research (Ulrich et al, 2012). Ongoing research has shown the positive impact of HRM’s recognized unique operational competencies (Caligiuri et al, 2020; Tomčíková et al, 2021), such as short-term austerity measures (Collings et al, 2021b) as opposed to certain perceived strategic orientations to help organisations navigate the Great Recession (Teague, 2012).

The impact of COVID-19 on HRM has emphasized the need for more flexibility and communication in the workplace (Collings et al, 2021a). COVID-19 accelerated the adoption of fully digital methods to recreate the best aspects of in-person learning through live video and social sharing. Remote work also spread due to personal distancing (Lennert, 2020; Lipták, 2021) and HRM professionals had to help employees in adjusting to working from home (Karácsony, 2021b; Newman et al, 2023). As never before, organisations had to care about the mental health of their employees (HRForecast, 2021). There is no doubt that COVID-19 has caused significant changes in working patterns at different levels of organisations (Roy, 2024).

The COVID-19 pandemic does not only highlight a shift in the understanding of the work context and tensions among shareholders’ and stakeholders’ views but also shows the need for balancing the operational and strategic role of HRM (Collings et al, 2021a). In addition, the relationship between labour markets and COVID-19 seems obvious.

Crises like the pandemic create not only problems but also new exploitable opportunities (Swoboda, 2020). While the pandemic has undoubtedly created many difficulties for organisations, for example disrupting supply chains (GFK, 2024), it has also presented organisations with unique opportunities to reshape their HRM. Studies have shown that the pandemic has not only accelerated digital transformation and remote work but has also put the well-being of employees’ centre stage, prompting many companies to reassess and change their HRM (Szyjewski, 2020; Carnevale and Hatak, 2020; Bešić et al, 2022, 2024). One such instance is from Carnevale and Hatak (2020) who noted that the pandemic has led to more flexible work options and to better employee support systems. Bešić et al (2022) found that even in transition economies that are generally slower at adopting digital trends, the pandemic has led to accelerated digitalisation in HRM and remote work options, but also online recruiting and training. These changes might position companies in a favourable position long-term in the digital work environment (Regulating, 2021). Similarly, Bešić et al (2024) and Caligiuri et al (2020) highlighted the role of the pandemic in fostering employee wellbeing and care by HR departments, which leads to a more holistic view of HRM with the aim of promoting productivity, well-being and retention of employees post-COVID.

HR departments in CEE had to handle employee health and well-being swiftly in order to adjust to remote work and navigate challenging regulatory situations. The crisis sped up the digital change and increased worker flexibility, but also revealed deficiencies in digital skills, mental health assistance, and youth employment. In our example region, our aim was to understand how the pandemic upended HRM in countries that are geographically close and representative of different stages of economic development. Due to variations in the degree of economic development within the observed region and the degree of centralization of the (former) political and economic system, differences can be observed in the development of HRM practices in various CEE countries (Erutku and Valtee, 1997; Stankiew, 2015; Iwasaki, 2020; Karácsony and Pásztó, 2021a). Furthermore, we show below that HRM has changed across the regions, albeit in different ways.

We gathered data through a questionnaire-based survey conducted in six countries (Kovalcsik et al, 2021). The sample includes 955 respondents, which equals the number of participating organizations (companies and institutions). The participating organizations were represented by first line managers or HR managers.

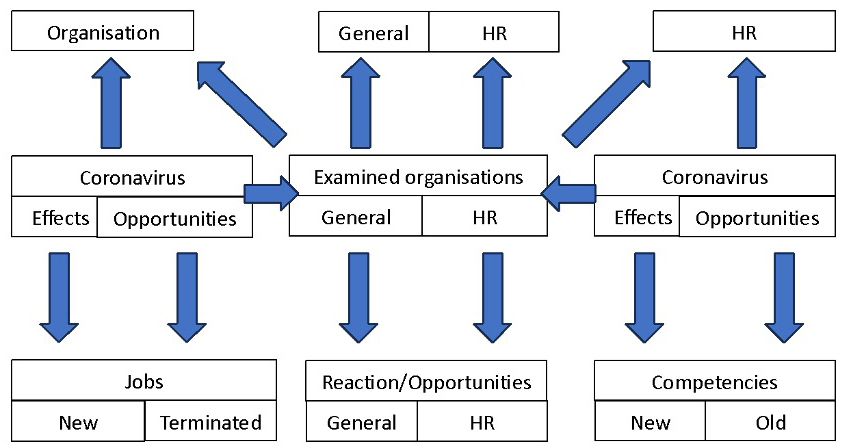

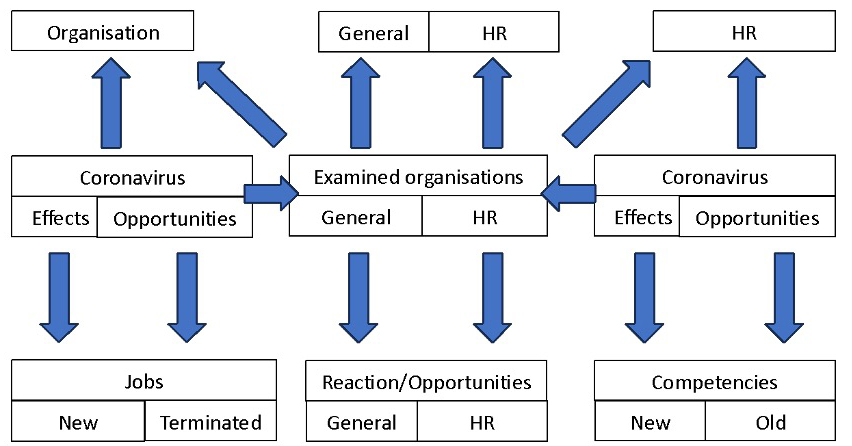

Fig. 1 summarizes our research model where we show the relationships between the organisational level in general and the HR-specific effects. We examined companies in general (effects of pandemics, business prospects, future expectations, corporate reactions to the crisis) and focused on HRM (crisis management, changes in the importance of competencies). Therefore, we also researched whether the respondents have seen an opportunity in the crisis (Sawada, 2021).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

COVID-HRM research model.

We collected the respondents’ experiences, opinions and expectations in each case, as follows:

• the current and expected effects of the pandemic on the CEE economies and organisations,

• the general and HRM crisis management measures that are most characteristic of the examined organisations,

• initiated (implemented or planned) changes in the HRM field in the surveyed organisations as a result of the crisis,

• strengthening/weakening HRM functions,

• the development and opportunities created by the coronavirus crisis at the examined organisation and its HRM organisation,

• jobs and competencies positively and/or negatively affected by the effects of the crisis,

• characteristics of the investigated organisation, the responding HRM area and the responding person.

The outcomes of the descriptive statistics guided the selection of applied methods. The descriptive statistics are described at the beginning of the Results and Discussion section. Among the national sub-samples, the number of items for the Bosnian and Austrian respondents did not reach one hundred, so we could not automatically state normal distribution according to the central limit theorem (Polya, 1920).

The composition of the sample shows that the majority of the organisations across all countries were small and medium-sized enterprises (Table 1).

| No. of employees | AT | BG | BA | HU | RO | SK | |

| 0 | 0 | 3.9 | 0 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 6.4 | 3.3 |

| 1–9 | 2.8 | 23.3 | 7.9 | 23.4 | 33 | 44.6 | 28.4 |

| 10–49 | 4.2 | 21.4 | 21.1 | 23.7 | 27.2 | 24.9 | 22.9 |

| 50–249 | 22.2 | 26.2 | 31.6 | 20.5 | 19.4 | 12 | 19.4 |

| 70.9 | 25.2 | 39.5 | 30.2 | 17.5 | 12 | 32.5 | |

| Total | 100 | ||||||

AT, Austria; BA, Bosnia and Herzegovina; BG, Bulgaria; HU, Hungary; RO, Romania; SK, Slovakia.

The distribution of the ownership of respondents is illustrated in Table 2.

| Ownership | AT | BG | BA | HU | RO | SK | |

| State or local authority-owned | 15.3 | 19.2 | 34.2 | 20.8 | 6.3 | 14.2 | 16.1 |

| National private | 56.9 | 42.3 | 34.2 | 48.4 | 72.3 | 64.4 | 56.8 |

| Foreign or joint stock | 22.2 | 32.7 | 28.9 | 26.6 | 18.9 | 18.9 | 23.5 |

| Non-profit organisation | 1.4 | 5.8 | 2.6 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.3 |

| Other | 4.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| Total | 100 | ||||||

The proportion of the latter shows a mixed picture in each country: in Austria 68%, Bosnia and Hercegovina 61%, Bulgaria 59%, but only 19% in Slovakia.

More than half (54%) of the respondents with an HRM department or HRM position reported an increase in the number of tasks. Only 22% of the respondents felt this way in Slovakia compared to 81% in Austria. In the other countries, between 53% and 63% of organisations reported an increased amount of HRM work (Table 3).

| AT | BG | BA | HU | RO | SK | ||

| Decreased | 1.4 | 2.4 | 7.9 | 3.4 | 2.2 | 8.5 | 4.0 |

| Unchanged | 18.1 | 34.5 | 39.5 | 40.2 | 38.7 | 69.5 | 42.0 |

| Increased | 80.6 | 63.1 | 52.6 | 56.4 | 59.1 | 22.0 | 54.1 |

| Total | 100 | ||||||

In addition to the increase in the amount of HRM tasks (Table 4), the majority of respondents also reported a further increase in the importance of professional HRM work; overall, 57% of the respondents said that this was to a medium or significant degree whilst 21% of the participants did not find this to be at all significant.

| AT | BG | BA | HU | RO | SK | ||

| 1* | 4.2 | 10.6 | 5.4 | 29.7 | 14.6 | 26.8 | 20.7 |

| 2 | 2.8 | 24.0 | 13.5 | 20.3 | 22.1 | 30.8 | 22.0 |

| 3 | 44.4 | 21.2 | 27.0 | 24.3 | 31.7 | 27.2 | 27.8 |

| 4* | 48.6 | 44.2 | 54.1 | 25.7 | 31.7 | 15.2 | 29.4 |

*1: not typical; 4: absolutely typical.

There was—not surprisingly—a significant, moderately strong relationship between the existence of the HRM department/job and the (decreasing, unchanged or increasing) expectations related to its efficiency and the perception of the increasing importance of professional HRM work (Chi-square test sig = 0.000; Cramer’s V = 0.322).

Where there was no HRM department or job, 44% did not consider it to be a further increase in the importance of professional HRM work. In cases that HRM effectiveness had increased, 88% said there was either a moderate (31%) or high (57%) further increase in the importance of HRM work, and only 2% did not find any.

Similarly, there was a significant relationship between judging the increase in the amount of HRM tasks and the importance of professional HRM work (Chi-square test sig = 0.000; Cramer’s V = 0.287). 52% of those who reported an increased number of tasks also reported a significant increase in the importance of HRM work, and only 2% said that this was not the case. Finally, there was a significant relationship between the existence of an HRM department/job and the expectations related to its efficiency (decreasing, unchanged, or increasing), as well as the change in the amount of HRM tasks (Chi-square test sig = 0.000; Cramer’s V = 0.576). In 75% of the cases where the amount of HRM tasks increased, expectations for efficiency had also increased.

At the time of the initial closures and disease prevention, government

assistance and human resource management came to play a prominent role. In the

following phase, all prevention practices remained a priority, but the role of

government assistance decreased (Lai and Wong, 2020). During the pandemic,

the dependence of wages on individual performance decreased, half of the

organisations suspended training and almost a third of the organisations also

suspended recruitment. At the same time, one-third of organisations increased

hiring and online communication; moreover, information sharing between

organisational units became a feature (Gunnigle et al, 2020). Most of the

organisations surveyed did not exhibit any measures aimed at reducing labour

demand or working hours (Table 5). Only “headcount stops” were used with a

significant proportion (48%), while only 39% of the respondents employed a

“reduction in working hours”. Both were most used in Austria and Bosnia and

Herzegovina and least implemented in Hungary. These were 65%, 76%, and 39% of

the respondents for “downtime”, and 59%, 84%, and 29% for “reduction in

working hours”, respectively. However, “permission to work from home” was

typical with nearly three-quarters (71%) of all organisations, which used it to

some extent. All Austrian organisations surveyed used this option. While Bulgaria

(94%), Bosnia and Herzegovina (90%), and Hungary (75%) had a very high rate of

use, the Slovak employers had the lowest rates. Two-thirds of the respondents

(66%) opted for “elaborating and revising their replacement and substitution

plans”, with the largest share coming from Austria (79%) and the smallest from

Slovakia (57%). Overall, it was not surprising that the two most frequent

measures were “new occupational health and safety measures” (86%) and

“enabling/directing home offices” (71%). These were followed by “supporting

personal development” (68%), “elaborating/replanning of replacement and

substitution plans” (66%), and “addressing employees’ social problems”

(64%). For all measures, there was a significant difference (Chi-square test

sig. = 0.000) between countries with the strongest difference (Cramer’s V

| HRM measures | Somewhat typical (%) | Cramer’s V | |||||||

| AT | BG | BA | HU | RO | SK | ||||

| No tasks | 43.9 | 37.9 | 67.6 | 30.5 | 43.8 | 55.0 | 42.5 | 0.000 | 0.179 |

| Hiring freeze | 64.7 | 45.5 | 75.7 | 38.5 | 47.5 | 52.7 | 48.0 | 0.000 | 0.136 |

| Staff reduction, downsizing | 35.3 | 26.7 | 16.2 | 22.0 | 26.3 | 30.3 | 26.1 | 0.000 | 0.139 |

| Downsizing of temporary staff | 21.9 | 28.0 | 32.4 | 21.2 | 24.5 | 28.0 | 24.8 | 0.001 | 0.120 |

| Reducing labour requirements by automation/technical solution | 43.9 | 64.0 | 50.0 | 25.7 | 37.4 | 35.5 | 36.5 | 0.000 | 0.238 |

| Reducing labour requirements by trainings and development | 45.5 | 63.0 | 60.0 | 24.4 | 49.0 | 31.2 | 38.4 | 0.000 | 0.252 |

| Reduction of working hours | 58.8 | 35.0 | 83.8 | 28.9 | 43.4 | 37.0 | 39.0 | 0.000 | 0.170 |

| Enabling/directing home offices | 100.0 | 94.2 | 89.5 | 75.1 | 60.2 | 53.4 | 71.4 | 0.000 | 0.253 |

| Elaboration/replanning of replacement and substitution plans | 79.0 | 67.7 | 71.4 | 65.1 | 71.9 | 56.5 | 66.0 | 0.000 | 0.133 |

| Pay freeze | 20.9 | 38.0 | 27.8 | 19.5 | 31.8 | 29.2 | 26.9 | 0.000 | 0.147 |

| Pay cut | 7.5 | 17.0 | 30.6 | 12.5 | 21.9 | 28.9 | 19.2 | 0.000 | 0.143 |

| Reducing fringe benefits | 31.3 | 36.3 | 50.0 | 17.2 | 41.7 | 37.0 | 31.5 | 0.000 | 0.185 |

| Addressing employees’ social problems | 84.8 | 74.3 | 75.0 | 68.1 | 58.9 | 48.4 | 63.7 | 0.000 | 0.224 |

| New occupational health and safety measures | 94.3 | 92.2 | 94.7 | 85.3 | 91.0 | 75.6 | 86.1 | 0.000 | 0.213 |

| Reducing the risks of the pandemic through training | 79.4 | 68.3 | 89.2 | 41.6 | 72.6 | 54.8 | 58.9 | 0.000 | 0.230 |

| Supporting personal development | 78.5 | 77.0 | 79.4 | 57.3 | 80.8 | 60.9 | 67.7 | 0.000 | 0.226 |

| Revision of the benchmarking scheme | 40.6 | 60.7 | 64.7 | 42.1 | 62.0 | 53.1 | 51.7 | 0.000 | 0.168 |

| Revision of the incentive scheme | 32.8 | 61.0 | 82.9 | 41.6 | 64.8 | 53.3 | 52.5 | 0.000 | 0.198 |

| Revision of equality strategy/plans | 30.2 | 58.0 | 54.5 | 29.6 | 49.0 | 47.4 | 42.0 | 0.000 | 0.189 |

Although the literature on the pandemic, especially during the period of lockdowns, primarily dealt with the ways and consequences of distancing, there were already studies during the first wave that saw opportunity in the crisis (Yan, 2020). At that time, digitalization and the development of online technology (Hirsch et al, 2023) were still in the focus of opportunities. Most organisations saw the crisis as an opportunity to bring about positive change, and they observed potential growth in many areas of HRM because of the new situation. Some 10% of the organisations (wX = 9.7%) surveyed said they did not see the pandemic crisis as an opportunity to make a positive difference at all, while 19% did (wX = 19.2%). Together, values 5–7 were reported by more than half of the organisations (57%) with an average of 4.61 responses; however, high standard deviations indicate a division in the treatment of the question. Austrian and Bulgarian organisations were the most optimistic with more than a quarter of respondents fully agreeing that the pandemic was a positive option for them with averages above 5 and a greater agreement of respondents (lower standard deviation). The Slovak organisations were the most pessimistic with an average of just over 4 with a large variance of responses, and only 15% of respondents fully agreed that a crisis could be an opportunity for their organisation (Table 6). There is a significant relationship between country affiliation and the assessment of potential development opportunities (Welch sig. = 0.000; Kruskal Wallis sig. = 0.000; Chi-square test sig. = 0.003).

| Scale | AT | BG | BA | HU | RO | SK | w | ||

| Distribution (in %) | Scale | 1* | 4.2 | 6.8 | 10.5 | 7.6 | 10.4 | 14.5 | 9.7 |

| 2 | 1.4 | 4.9 | 7.9 | 8.3 | 6.5 | 9.7 | 7.3 | ||

| 3 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 13.0 | 9.3 | 7.0 | 11.5 | 8.4 | ||

| 4 | 15.5 | 14.6 | 21.1 | 16.2 | 18.9 | 18.9 | 17.5 | ||

| 5 | 25.4 | 28.2 | 15.8 | 20.5 | 17.9 | 18.9 | 20.5 | ||

| 6 | 22.5 | 13.6 | 10.5 | 18.2 | 23.9 | 11.9 | 17.4 | ||

| 7* | 28.2 | 28.2 | 21.1 | 19.9 | 15.4 | 14.5 | 19.2 | ||

| Total | 100.0 | ||||||||

| 5.37 | 5.06 | 4.39 | 4.68 | 4.61 | 4.12 | 4.61 | |||

| Σ | 1.524 | 1.765 | 1.953 | 1.839 | 1.855 | 1.946 | 1.873 | ||

*1: not at all; 7: maximum.

From an HRM point of view (Table 7), most organisations saw potential development opportunities primarily in the areas of internal communication (53%), atypical employment/home office (47%) and occupational health and safety (50%), although there were significant differences between countries. This was particularly noticeable in the field of atypical employment; while 88% of Austrian respondents saw development opportunities in this area; this was only the case for 30% of the Slovaks, 40% of the Romanians, and 46% of the Hungarians. In the field of occupational health and safety, differences were smaller. It was quite pronounced everywhere while the smallest differences were in the assessment of internal communication. In addition to these, relatively many companies saw potential development opportunities in the area of job analysis and planning (41%), personnel planning, succession planning (30%), and performance management (30%).

| No. | HRM areas | AT | BG | BA | HU | RO | SK | |

| 1 | Staff planning | 30.6 | 20.2 | 34.2 | 31.4 | 28.2 | 35.2 | 30.4 |

| 2 | Job analysis | 29.2 | 61.5 | 60.5 | 37.9 | 34.0 | 43.3 | 41.2 |

| 3 | Recruitment | 40.3 | 36.5 | 23.7 | 27.1 | 34.0 | 18.0 | 28.3 |

| 4 | Home office | 88.9 | 68.3 | 63.2 | 46.4 | 39.8 | 29.6 | 47.1 |

| 5 | Performance management | 22.2 | 36.5 | 26.3 | 27.1 | 35.9 | 29.2 | 30.1 |

| 6 | Incentive management | 16.7 | 32.7 | 23.7 | 25.8 | 35.9 | 24.0 | 27.5 |

| 7 | Social assistance | 51.4 | 48.1 | 34.2 | 29.7 | 14.1 | 22.7 | 28.5 |

| 8 | Human resource development | 41.7 | 33.7 | 36.8 | 23.9 | 25.2 | 28.3 | 28.2 |

| 9 | Labour relations | 12.5 | 39.4 | 28.9 | 15.0 | 37.9 | 18.5 | 23.8 |

| 10 | Occupational health and safety | 61.1 | 46.2 | 71.1 | 45.4 | 51.9 | 48.5 | 49.8 |

| 11 | Career planning | 5.6 | 26.0 | 2.6 | 13.1 | 13.1 | 12.4 | 13.3 |

| 12 | Internal communication | 62.5 | 63.5 | 42.1 | 59.2 | 50.5 | 42.9 | 53.4 |

| 13 | Retention management | 12.5 | 29.8 | 39.5 | 27.5 | 37.9 | 5.2 | 23.9 |

| 14 | Generation management | 12.5 | 19.2 | 13.2 | 6.9 | 8.3 | 15.0 | 11.2 |

| 15 | Equal opportunities | 16.7 | 14.4 | 13.2 | 9.8 | 22.8 | 9.9 | 13.8 |

| 16 | Diversity | 18.1 | 18.3 | 13.2 | 5.6 | 14.6 | 10.7 | 11.4 |

| 17 | Miscellaneous | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.9 |

We noted in the literature review that some authors wrote about the

strengthening of human-centric HRM (Konyu-Fogel, 2016; Mike et al, 2019; Collings et al, 2021a; Collings et al, 2021b). Our own results confirm these

observations. Based on the overall average of the measures listed in Table 7 (

While staff reductions and downsizing, which were implemented almost automatically during previous crises, point directly to ignoring social issues, they also signal a shift in perspective. It is also an innovative measure because it indicates the strengthening of long-term strategic thinking. Instead of an immediate answer, it is more of an investment in the future: it increases employee engagement and loyalty and preserves hard-to-replace knowledge capital. The change is also confirmed by the fact that the “Pay freeze”, “Pay cut”, “Staff reduction, downsizing”, “Downsizing of temporary staff” measures are only applied by one-quarter or one fifth of the responding companies. It is also human-centric that the ratio of “Reducing labour requirements by trainings and development” (38.4) is higher than the ratio of “Reducing labour requirements by automation/technical solution” (36.5). It also highlights the importance of employee retention.

The study looked into how the COVID-19 pandemic affected human resource management in six Central and Eastern European countries and whether it contributed to a paradigm shift in HRM. Our research shows that organisations finally implemented long-delayed initiatives. Respondents either started using remote work practices that had previously been neglected more frequently or initiated health and occupational safety initiatives. As a result, the pandemic prompted the development of innovative management techniques (Hamouche, 2021; Newman et al, 2023).

We analysed the strategic evolution of HRM following the pandemic, the growing importance of the human component, and how businesses might view such a crisis as an opportunity.

In our article, we dealt with, among others, the paradigm shift related to HRM. As we highlighted in the introduction, following Kuhn (1962), we believe that the development of certain scientific fields does not progress as a linear accumulation of new knowledge, but undergoes periodic revolutions called “paradigm shifts”. The process already started before the pandemic (Brammer et al, 2019; Srinivasa Rao et al, 2018). Overall, it can be said that in advanced and innovative organisations, HRM has left behind the previously typical and well-known HRM development phases (administrator, collective agreement conciliator, strategic partner, consultant, competency developer, etc.) (Ulrich et al, 2009). The pandemic years ushered in the “well-being”- “well-work” development phase of human resource management. Moreover, our research has clearly highlighted that at the beginning of COVID-19 this pandemic accelerated, not disrupted, HR trends (Sheedy, 2020). Remote and contingent work, which had already been implemented and had spread in previous years, is still widely used (Gartner, 2021).

Prior to the pandemic, several HR transformations were already underway across different sectors. These included flexible working arrangements, well-being programmes, remote work options, digitalization, and a shift in employer-employee relationships. These pre-existing changes influenced how organisations responded to the radical impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, including widespread use of remote work (Gigauri, 2020; Massimino, 2023). According to some scholars COVID-19 marked an important “inflection point” that led to “the revaluation of the priorities of individuals, organizations and society as a whole” (Lazarova et al, 2023). Other researchers associate the paradigm shift with the significant development of digitalization (Leonardi and Treem, 2020) and the impact of FDI on HR practices in South Asian countries (Rowley et al, 2017; Chen et al, 2022) and Central European (Lewis, 2005).

As previously stated, COVID-19 significantly accelerated and transformed the various areas of HR including technology, employee expectations, flexible adaptability, hybrid working, acceptance of others, and diversity. However, we must also acknowledge that the pandemic’s duration and extent of the changes it revealed were not yet sufficient to warrant a complete and true paradigm shift. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the paradigm shift has started. While our article examines these COVID-19 driven changes, further theoretical and empirical research is needed to ascertain whether they represent a true HR paradigm shift.

The research confirms that contextual mediations (Mayrhofer et al, 2023), such as organisational characteristics or digital transformation, etc., play a crucial role in understanding the paradigm shift in HR following the COVID-19 pandemic (Obrenovic et al, 2020). This has led to a redefinition of the strategic role of HR in the post-pandemic business environment. Li et al (2024)’s study pointed out that following the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a significant shift from general labour shortages to specific talent shortages and geographical disparities in local labour markets, which may have also affected the regional distribution of the workforce.

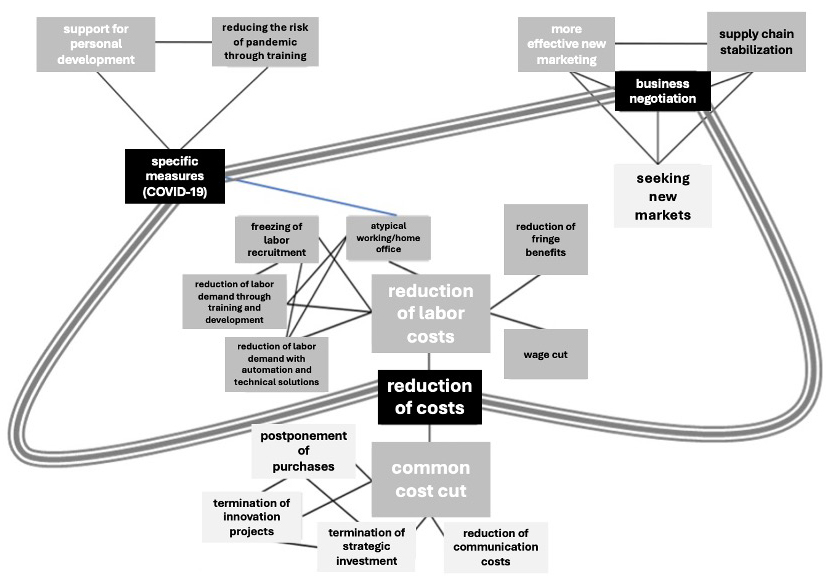

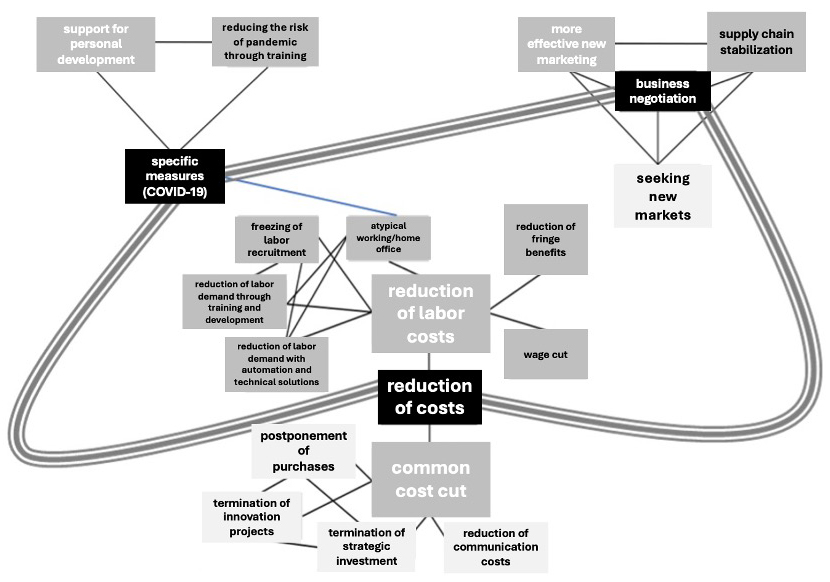

The authors used a correlation test to examine the relationships between the HRM measures included in the questionnaire. The result was then plotted graphically. The correlations marked with black lines in the figure are all significant relationships of medium strength.

In Fig. 2, the crisis management measures are organised around three nodes: (1) cost reduction; (2) renewed business strategy; (3) crisis-specific measures. The first two are standard business practices, whilst the third addresses specific crises. During a business strategy reorganisation, companies seek new markets and strengthen marketing and reliability. Stabilising supply chains ensures the availability of necessary materials.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Correlation map of HR measures. Note: Triple lines represent correlations between crisis management focuses, whereas single lines indicate correlations between crisis management measures. All correlations are significant relationships of medium strength.

Cost reduction occurs in two main areas: general and labour costs. General cost reduction includes delaying purchases, halting innovation, ending strategic investments, and reducing communication costs. Labour costs can be cut by reducing wages and benefits, or by downsizing. Automation and retraining can help, and working from home reduces expenses.

Crisis-specific measures address the unique aspects of a crisis. For instance, COVID-19 led to increased employee protection and reliance on home offices, which also cut costs. These measures are often connected to cost reduction and business strategy renewal. Furthermore, increased efficiency leads to lower costs.

Our empirical findings indicate that the HR strategy stance is also enhanced if the organization has its own HR department or HR specialist (Minbaeva and Navrbjerg, 2023). This finding is in line with the global research results of Cranet conducted in 2021–2022 (Cranet, 2023). In addition, more than half of the surveyed organisations treated the crisis as an opportunity rather than a risk.

We believe that due to the essential differences that can be experienced in different regions of the world, in different capitalistic countries and also in the validity of the perspective system of the stakeholders, different HRM approaches and practices have emerged. Moreover, these are further coloured by the institutional and cultural characteristics of each country (Diamond, 2019). These characteristics also explain the contextual nature of HRM, i.e., its dependency on environmental conditions (Karoliny and Szabó-Bálint, 2022; Parry et al, 2020; Torrington et al, 2020).

While our study spans six nations and offers regional data, we identify limitations and implications.

The goal of our study was to create a constantly expanding international network that examines the impact of crises with a focus on HRM, and to formulate forecasts and advice. However, other nations must be taken into account to provide a more comprehensive perspective. The focus on Central and Eastern European countries may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions, such as Western Europe, North America, or Asia, where the unique socio-political and economic conditions of these regions could influence HRM responses differently. While the study focuses on HRM changes, it may not have accounted for other important factors, such as cultural differences that could have influenced the HRM responses. Future research could compare HRM responses across a wider range of regions or countries, both within and outside Europe, to identify common patterns or unique challenges faced by different regions in managing HR during a crisis.

Thanks to the large number of participating organisations, our sample is consistent with general trends in the sector and ownership distribution ratios. It is worth noting that key stakeholders (businesses and institutions) were involved in the majority of our research sectors. Still, it would have been intriguing to observe how employees, rather than just company representatives, felt about a paradigm shift. Future studies could include such employee perceptions and experiences of HRM changes to better understand how the perceived opportunity or challenge varies from the organizational perspective.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

JP, ZSK: conceptualization, theoretical framework development; AT, BK: statistical analysis, data collection; ÉIK: statistical analysis; KS: literature review; CH, AB, BP, ZS: managerial implications, discussion structuring; KK, GSS: policy recommendations, sustainable business practices; ZR: language and formatting, final manuscript review.

The researchers thank all organizations participating in the research for providing data.

The Austrian team would like to acknowledge the financial support provided by the Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research (BMBWF) via the OEAD-WTZ HU07/2022 programme. The Hungarian team is thankful for the financial support received under research project number 2021-1.2.4-TÉT-2021-00006 from National Research, Development and Innovation Office in Hungary.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. JP serves as editorial board member of this journal. JP declares that he was not involved in the processing of this article and has no access to information regarding its processing.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.