1 Cancer Research Center, Capital Medical University Affiliated Beijing Chest Hospital, 101149 Beijing, China

Abstract

The tyrosine kinase signaling pathway is an important pathway for cell signal transduction, and is involved in regulating cell proliferation, cell cycle, apoptosis and other essential biological functions. Gene mutations involved in the tyrosine kinase signaling pathway often lead to the development of cancers. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) are well known receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), which belong to the ERBB family and have high mutation frequency in cancers. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) targeting EGFR and HER2 have been widely used in the clinical treatment of lung and breast cancers. However, after a period of treatment, patients will inevitably develop resistance to TKI. The insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor family, like the ERBB receptor family, belongs to the receptor tyrosine kinase superfamily, which also conducts an important cell signal transduction function. There is an overlap between IGF signaling and EGFR signaling in biological functions and downstream signals. In this review, we summarize the current state of knowledge of how IGF signaling interacts with EGFR signaling can influence cell resistance to EGFR/HER2-TKI. We also summarize the current drugs designed for targeting IGF signaling pathways and their research progress, including clinical trials and preclinical studies. Altogether, we aimed to discuss the future therapeutic strategies and application prospects of IGF signaling pathway targeted therapy.

Keywords

- insulin-like growth factor

- tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- drug resistance

- cancer

- EGFR

- HER2

Cancer is one of the major challenges to human health. Female breast cancer has the highest incidence (accounting for 11.7% of de novo tumors), followed by lung cancer (11.4%), which is the leading cause of cancer death (accounting for 18.0% of total cancer deaths) [1]. Thanks to the progress of life science research, we now have had a deep understanding of the mechanism of cancer, such as intracellular signal transduction, cell cycle regulation and apoptosis induction. It has been found that tyrosine kinases play a significant role in tumorigenesis and development [2]. Mutations in some genes can lead to sustained activation of tyrosine kinases, which results in uncontrolled cell growth. These genes, which can cause cells to become immortalized or cancerous, are called tumor driven genes [3]. Tyrosine kinase has become an important therapeutic target in the treatment of cancer. The increased use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), which are often small molecule inhibitors targeting tyrosine kinases, are a prelude to targeted therapy for cancer treatment, and have the potential to effectively prolong the survival of cancer patients [4]. A retrospective study analyzed the median survival (95% CI) of patients with lung adenocarcinoma, and found that the median survival of patients with tumor driven genes mutation who received targeted drug therapy was 3.49 months (3.02–4.33), which was significantly higher than that of patients with tumor driven genes mutation but receiving conventional treatment (surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy) (2.38 months (1.81–2.93)) and patients without tumor driven genes mutation and receiving conventional treatment (2.08 (1.84–2.46)) [5]. Another study suggested that 60%–80% of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with imatinib achieved clinical benefits lasting more than a decade [6]. Although the use of targeted kinase inhibitors has brought significant benefits to many cancer patients, it is disappointing to note that these drugs are not curative and most only delay tumor progression, because acquired resistance ultimately develops in most patients with advanced metastatic disease [7]. Solving the problem of drug resistance and enhancing drug sensitivity are the key to improving the therapeutic effect and the prognosis of cancer patients.

In this review, we introduce two representative TKIs, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-TKIs and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-TKIs, for the treatment of lung and breast cancer. We describe the clinical application of EGFR-TKI and HER2-TKI in these cancers, the current results of these therapies, and the status of the development of drug resistance for these TKIs. The mechanism of TKI resistance is complicated, and several studies have found that the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling pathway plays a crucial role in TKI resistance [8, 9, 10]. In this review, we describe the relationship between the IGF pathway and acquired resistance to TKIs.

Protein kinase/phosphatase-regulated signaling pathways are involved in the occurrence and development of almost all types of cancer and have become one of the most important drug targets in the 21st century [4]. The tyrosine residues of the receptor protein are phosphorylated and interact with downstream signaling molecules to activate the Ras/Raf/MAPK or PI3K/Akt signaling pathways and regulate the survival, proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells. Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), which have become the key targets for cancer treatment, are composed of multiple receptor families, including the ERBB receptor family (such as EGFR, HER2), the IGF receptor family (such as IGF-1R, InsR), the VEGF receptor family, the FGF receptor family, the c-MET receptor, and the ALK receptor. Since the end of 2022, 78 small molecule protein kinases-targeted inhibitors have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), of which 18 inhibitors target non-receptor tyrosine kinases and 38 inhibitors target receptor tyrosine kinases (Table 1, Ref. [11, 12]). The main targets of TKIs include EGFR/HER, VEGFR, ALK, MET, JAK, FGFR, ABL, KIT [12], among which the most widely and successfully used are EGFR and HER2. EGFR and HER2 are members of the transmembrane RTKs ERBB family.

| Drug | Primary targets |

The type of target/drugs |

Year approved | Therapeutic indications |

| Abemaciclib | CDK4/6 | CMGC | 2017 | Combination therapy with an aromatase inhibitor or with fulvestrant or as a monotherapy for breast cancers |

| Abrocitinib | JAK | TK | 2022 | Atopic dermatitis |

| Acalabrutinib | BTK | TK | 2017 | Mantle cell lymphomas, CLL, SLL |

| Afatinib | EGFR/HER | TK | 2013 | NSCLC |

| Alectinib | ALK | TK | 2015 | ALK-positive metastatic NSCLC that progressed on or is intolerant to crizotinib |

| Alpelisib | PI3K | LK | 2019 | Combination therapy with fulvestrant for advanced or metastatic breast cancer with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative (HR+/HER2-) and PIK3CA-mutation, in postmenopausal women or men |

| Amivantamab-vmjw | EGFR/MET | ADCs | 2021 | NSCLC with EGFR exon 20 insertion mutation |

| Asciminib | ABL | TK | 2021 | Ph+ CML in chronic phase (CP), previously treated with 2 or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) |

| Avapritinib | KIT | TK | 2020 | GIST with PDGFR |

| Axitinib | VEGFR | TK | 2012 | RCC |

| Baricitinib | JAK | TK | 2017 | Extensive alopecia |

| Binimetinib | MEK1/2 | STE | 2018 | Combination therapy with encorafenib for BRAF V600E/K melanomas |

| Bosutinib | ABL | TK | 2012 | Newly diagnosed chronic phase Ph+ CML |

| Brigatinib | ALK | TK | 2017 | ALK-positive metastatic NSCLC that have progressed or are intolerant to crizotinib |

| Cabozantinib | RET | TK | 2012 | Medullary thyroid cancers, RCC, HCC |

| Capmatinib | MET | TK | 2020 | NSCLC with MET exon 14 skipping |

| Ceritinib | ALK | TK | 2014 | ALK-positive metastatic NSCLC that progressed on or is intolerant to crizotinib |

| Cetuximab | EGFR/HER | mAb | 2004 | EGFR-expressing metastatic colorectal carcinoma intolerant to irinotecan-based chemotherapy |

| Cobimetinib | MEK1/2 | STE | 2015 | BRAF V600E/K melanomas in combination with vemurafenib |

| Copanlisib | PI3K | LK | 2017 | Adult patients with recurrent marginal zone lymphoma who have received at least two-line treatment |

| Crizotinib | ALK | TK | 2011 | Locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC with ALK-positive |

| Dabrafenib | BRAF | TKL | 2013 | BRAF V600E/K melanomas, BRAF V600E NSCLC, BRAF V600E anaplastic thyroid cancers |

| Dacomitinib | EGFR/HER | TK | 2018 | EGFR-mutant NSCLC |

| Dasatinib | ABL | TK | 2006 | CML |

| Deucravacitinib | TYK2 | TK | 2022 | Adult patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis suitable for systemic therapy or phototherapy |

| Duvelisib | PI3K | LK | 2018 | SLL, CLL, FL |

| Encorafenib | BRAF | TKL | 2018 | Combination therapy with binimetinib for BRAF V600E/K melanomas |

| Entrectinib | TRK | TK | 2019 | Solid tumors with NTRK fusion proteins, ROS1-positive NSCLC |

| Erdafitinib | FGFR | TK | 2019 | Urothelial bladder cancers |

| Erlotinib | EGFR/HER | TK | 2004 | NSCLC, pancreatic cancers |

| Everolimus | mTOR | AK | 2009 | HER2-negative breast cancers, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, RCC, angiomyolipomas, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas |

| Fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan-nxki | HER2 | ADCs | 2022 | Unresectable or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with HER2 mutation |

| Fedratinib | JAK | TK | 2019 | Myelofibrosis |

| Fostamatinib | SYK | TK | 2018 | Immunothrombocytopenia |

| Futibatinib | FGFR | TK | 2022 | Locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with FGFR2 gene rearrangement/fusion |

| Gefitinib | EGFR/HER | TK | 2003 | NSCLC |

| Gilteritinib | FLT3 | TK | 2018 | AML |

| Ibrutinib | BTK | TK | 2013 | CLL, mantle cell lymphomas, marginal zone lymphomas, graft vs. host disease, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia |

| Idelalisib | PI3K | LK | 2014 | SLL, CLL, FL |

| Imatinib | ABL | TK | 2001 | Ph+ CML or ALL, aggressive systemic mastocytosis, chronic eosinophilic leukemias, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, hypereosinophilic syndrome, GIST, myelodysplastic/ myeloproliferative disease |

| Infigratinib | FGFR | TK | 2021 | Cholangiocarcinomas with FGFR2 fusion proteins |

| Lapatinib | EGFR/HER | TK | 2007 | In combination with letrozole for post-menopausal women with HR-positive metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses the HER2 receptor |

| Larotrectinib | TRK | TK | 2018 | Solid tumors with NTRK fusion proteins |

| Lenvatinib | VEGFR | TK | 2015 | Differentiated thyroid cancers |

| Lorlatinib | ALK | TK | 2018 | ALK-positive metastatic NSCLC that has progressed on crizotinib and at least one other ALK inhibitor or alectinib/ceritinib as the first ALK inhibitor therapy |

| Margetuximab | HER2 | mAb | 2020 | Metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer |

| Midostaurin | FLT3 | TK | 2017 | AML, mastocytosis, mast cell leukemias |

| Mobocertinib | EGFR/HER | TK | 2021 | NSCLC for EGFR-positive exon 21 insertions |

| Necitumumab | EGFR/HER | mAb | 2015 | Combined with gemcitabine and cisplatin for the first-line treatment of metastatic squamous NSCLC |

| Neratinib | EGFR/HER | TK | 2017 | HER2-positive breast cancers |

| Netarsudil | ROCK1/2 | AGC | 2017 | Glaucoma |

| Nilotinib | ABL | TK | 2007 | Ph+ CML |

| Nintedanib | VEGFR | TK | 2014 | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| Olaratumab | PDGFR- |

mAb | 2016 | Combined with doxorubicin for adult soft tissue sarcomas |

| Osimertinib | EGFR/HER | TK | 2015 | Metastatic EGFR T790M mutation-positive NSCLC that progressed on or after EGFR TKI therapy |

| Pacritinib | JAK | TK | 2022 | Myelofibrosis |

| Palbociclib | CDK4/6 | CMGC | 2015 | In combination with letrozole for postmenopausal women with ER-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer for metastatic disease |

| Panitumumab | EGFR/HER | mAb | 2006 | EGFR-expressing metastatic colorectal carcinoma |

| Pazopanib | VEGFR | TK | 2009 | RCC, soft tissue sarcomas |

| Pemigatinib | FGFR | TK | 2020 | Advanced cholangiocarcinoma with a FGFR2 fusion or rearrangement |

| Pertuzumab | HER2 | mAb | 2012 | In combination with trastuzumab and docetaxel for neoadjuvant treatment of HER2-positive locally advanced inflammatory or early-stage breast cancer |

| Pexidartinib | CSF1R | TK | 2019 | Tenosynovial giant cell tumors |

| Ponatinib | ABL | TK | 2012 | Ph+ CML or ALL |

| Pralsetinib | RET | TK | 2020 | RET-fusion NSCLC, medullary thyroid cancer, thyroid cancer |

| Ramucirumab | VEGFR | mAb | 2014 | Gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma, metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer |

| Regorafenib | BRAF | TKL | 2012 | Colorectal cancers |

| Ribociclib | CDK4/6 | CMGC | 2017 | Combination therapy with an aromatase inhibitor for breast cancers |

| Ripretinib | KIT | TK | 2020 | Fourth-line treatment for GIST |

| Ruxolitinib | JAK | TK | 2011 | Myelofibrosis, polycythemia vera, atopic dermatitis |

| Selpercatinib | RET | TK | 2020 | Metastatic RET fusion-positive NSCLC, thyroid cancers, RET mutant medullary thyroid cancers |

| Selumetinib | MEK1/2 | STE | 2020 | Neurofibromatosis type I |

| Sirolimus | mTOR | AK | 1999 | Kidney transplants, lymphangioleiomyomatosis |

| Sorafenib | BRAF | TKL | 2005 | HCC, RCC, thyroid cancer (differentiated) |

| Sunitinib | VEGFR | TK | 2006 | GIST, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, RCC |

| Temsirolimus | mTOR | AK | 2007 | RCC |

| Tepotinib | MET | TK | 2021 | NSCLC with MET mutations |

| Tirbanibulin | SRC | TK | 2020 | Actinic keratosis |

| Tivozanib | VEGFR | TK | 2021 | Third-line treatment of RCC |

| Tofacitinib | JAK | TK | 2012 | Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis |

| Trametinib | MEK1/2 | STE | 2013 | In combination with dabrafenib for unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations |

| Trastuzumab | HER2 | mAb | 1998 | HER2-positive breast cancer |

| Trastuzumab–deruxtecan | HER2 | ADCs | 2019 | HER2 low expression metastatic breast cancer |

| Trastuzumab–emtansine | HER2 | ADCs | 2013 | HER2 positive breast cancer |

| Trilaciclib | CDK4/6 | CMGC | 2021 | Chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression |

| Tucatinib | EGFR/HER | TK | 2020 | Combination second-line treatment for HER2-positive breast cancers |

| Umbralisib | PI3K/CK1 | LK/CK | 2021 | Marginal zone lymphoma, FL |

| Upadacitinib | JAK | TK | 2019 | Second-line treatment for rheumatoid arthritis |

| Vandetanib | VEGFR | TK | 2011 | Medullary thyroid cancers |

| Vemurafenib | BRAF | TKL | 2011 | BRAF V600E melanomas |

| Zanubrutinib | BTK | TK | 2019 | Mantle cell lymphomas |

The ERBB family, also known as the EGF receptor family or Type I receptor family, is a transmembrane RTKs family, whose members include ERBB1 (EGFR/HER-1), ERBB2 (Neu/HER-2), ERBB3 (HER-3) and ERBB4 (HER-4) [13]. ERBB receptors are activated after homodimerization or heterodimerization, which sequentially activates intracellular signaling cascades. There are two main downstream pathways, the RAS-RAF-MEK-MAPK pathway and the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway [14]. The former controls gene transcription, cell cycle progression and cell proliferation, while the latter activates anti-apoptotic and pro-survival signaling cascades [15]. About 20% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients have EGFR activating mutations. The main subtype includes exon 19 deletion (Ex19del) and exon 21 L858R mutation [16]. HER2 mutations are found in approximately 25–30% of tumors in invasive breast cancer [17]. Mutations in the EGFR and HER2 genes lead to persistent activation of the ERBB signaling pathway, resulting in uncontrolled cell growth, immortalization of cells and transformation into cancer cells. Using targeted drugs to specifically inhibit abnormally expressed genes can effectively inhibit the process of tumor growth, metastasis and invasion, and have the potential to treat several malignancies. To accomplish this, scientists have designed a variety of small molecule inhibitors targeting EGFR and HER2. In this review, we will introduce the clinical application of EGFR-TKI and HER2-TKI in the treatment of lung and breast cancers.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, with more

than half (57%) of lung cancer patients having metastases at the time of

diagnosis, with only a 5% 5-year survival rate [18]. NSCLC is the most dominant

subtype of lung cancer, accounting for 85% of all lung cancer cases [19].

EGFR is one of the most common driven gene in NSCLC. The proportion of

EGFR activation mutation in NSCLC patients is about 20% [16]. Females

(69.7%), non-smokers (66.6%), and patients with adenocarcinoma (80.9%), have a

higher frequency of EGFR mutations (p

From the history of multigenerational EGFR-TKIs development, it can be learnt that simply optimizing TKIs to improve the efficacy of targeted drugs may not be the best way to manage drug resistance, as the newly occurred mutations may be endless. Alternative approaches to managing patient resistance should be considered, such as combining immunotherapy or chemotherapy, using downstream signaling pathway inhibitors or targeting non-target-dependent resistance mechanisms.

According to the latest statistics, the morbidity of breast cancer is now the highest of all cancers and exceeds that of lung cancer [1]. Breast cancer can be divided into separate tumor subtypes according to the expression of prognostic factors such as estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2, which are closely relevant to treatment strategies [31]. ER-positive tumor patients mainly receive endocrine therapy; HER2-positive tumors can be treated with antibodies or small molecule inhibitors targeting HER2; while patients with triple-negative tumors generally receive chemotherapy [32]. HER2 (ERBB2/Neu) is one of the most typical oncogenes involved in the occurrence of breast cancer. HER2-positive breast cancer, characterized by HER2 protein overexpression or gene amplification, has been found in approximately 25% to 30% of invasive breast cancers, and is especially associated with a poor prognosis [17]. Unlike other members of the ERBB family, HER2 lacks natural ligands in vivo, and HER2 exerts its biological effects primarily by forming dimers with itself or other growth factor receptors [14]. The main dimerizing chaperones include EGFR/HER1, HER3, IGF-1R, IGF-2R, and c-MET [33]. Similar to EGFR, HER2 has ATP-dependent tyrosine kinase domains and extracellular domains, enabling it to be targeted with small molecule inhibitors or monoclonal antibodies (mAb).

There are several HER2-targeting drugs now used in clinical practice. Trastuzumab (Herceptin), a humanized mAb targeting the extracellular subdomain IV of HER2 [34], which induces antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), is widely used as a targeted therapy in patients with HER2 overexpression. Lapatinib, a small molecule inhibitor that targets both EGFR and HER2, has been approved for HER2-positive breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab with disease progression [35]. Pertuzumab is a second-generation recombinant humanized mAb, which can bind to the extracellular dimerization domain II of HER2, thereby preventing HER2 from forming heterodimer with HER1, HER3, HER4, and IGF-1R, consequently inhibiting cell proliferation [36]. In addition, trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) is an antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) that combines the anti-HER2 effect of trastuzumab with the cytotoxicity of the anti-microtubule agent DM1 in order to selectively introduce potent cytotoxic agents into HER2-overexpressing cells by binding to HER2 [37].

The application of TKIs has brought great hope to a large number of patients suffering from lung, breast, and colorectal cancers, leukemia and other tumors; however, most patients will inevitably develop drug resistance after the use of targeted drugs. NSCLC patients treated with EGFR-TKIs develop drug resistance in an average of 6 to 13 months [38]. The majority of patients who achieve an initial response to trastuzumab-based regimens develop resistance within 1 year [39]. A comprehensive understanding of the resistance mechanisms of TKIs will contribute to the development of a new generation of targeted drugs and follow-up therapy, which has the potential to effectively prolong patient survival. The resistance mechanisms of TKIs are complicated and varied, and are divided into target-dependent resistance mechanisms and non-target-dependent resistance mechanisms. The former is usually induced by a secondary mutation in the ATP-binding pocket of the receptor kinase, which alters its molecular conformation and declines its combination with TKI [40]. Similar to the development of the third generation EGFR-TKI, this type of drug resistance can be effectively improved by changing the chemical conformation of pharmaceutical molecules. Non-target-dependent drug resistance mechanisms are more complex and diverse, including compensation of other signaling pathways, sustained activation of downstream pathways, and phenotypic transformation [40, 41]. For example, in spite of the capacity of EGFR-TKIs that can still inhibit the phosphorylation of mutant EGFR, drug-resistant cells maintain activation of survival and proliferation signals through other pathways.

Several studies have shown that the activation of the IGF signaling pathway can impact the sensitivity of cells to TKIs. Choi et al. [42] found that inhibition of IGF-1R enhanced the growth inhibition and pro-apoptotic effects of gefitinib on H1650 cells. Increased phosphorylation of IGF-1R and AKT was found in hepatocellular carcinoma cells after gefitinib treatment [43]. The expression of IGF-1 was also significantly increased in erlotinib-resistant glioblastoma cell lines, but not in sensitive cell lines [44]. Seropositivity of IGF-1 was found to be an independent adverse prognostic factor in NSCLC patients treated with gefitinib [45]. The specificity of predicting gefitinib resistance with high levels of total IGF-1R was 76%, and the positive predictive value was 81%. The specificity of predicting gefitinib resistance with high levels of phosphorylated IGF-1R was 100%, the sensitivity was 41%, the positive predictive value was 100%, and the negative predictive value was 23%, implying that the expression of IGF-1R can be used as a biomarker to predict the emerging resistance of NSCLC to gefitinib [46]. These findings suggest that the use of TKIs may promote the activation of the IGF pathway, and the activation of the IGF pathway is involved in the resistance of cells to TKIs.

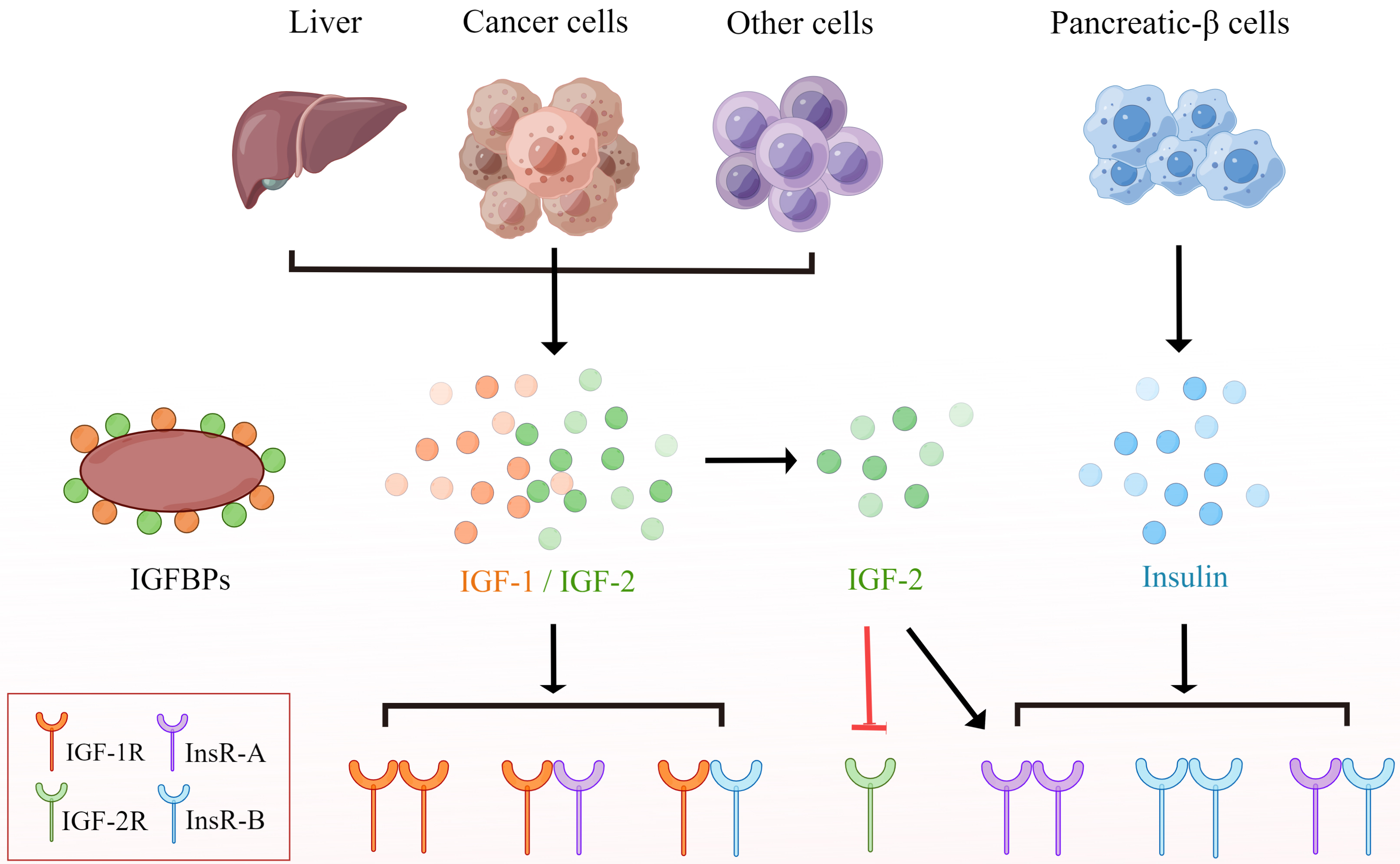

The IGF pathway is an intricate network, mainly consisting of the following three components: three ligands, insulin, IGF-1, IGF-2; three cell surface receptors, IGF-1R, IGF-2R, insulin receptor (InsR); and six high-affinity insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBPs) [47]. IGFs are synthesized in the liver prevailingly, and the level of IGFs is regulated by IGFBPs principally [8, 48]. There are 6 types of IGFBPs with high affinity in vivo, which bind to 98% of circulating IGF-1 and act as carrier proteins to regulate the transport of IGF-1 and prolong its relatively short half-life [49, 50]. InsR, IGF-1R and IGR-2R are all transmembrane dimer receptors. IGF-1R and InsR belong to RTKs family. Since they are of the same domain, IGF-1R and InsR usually exist on the cell surface in the form of a homodimer or heterodimer [51]. Similarly, the extracellular domain structure of EGFR, which belongs to RTKs as well, is similar to that of IGF-1R [52], suggesting the possibility of IGF-1R/EGFR heterodimer formation [53]. The prime activating ligands of IGF-1R are IGF-1 and IGF-2. After combining with the ligands, IGF-1R activates its tyrosine kinase activity, phosphorylates some insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins, and then triggers multiple downstream signaling pathways, including the RAS-RAF-MEK-MAPK pathway, the PI3K-AK-mTOR pathway, TAK/STAT and Src pathways, which are closely associated with the proliferation, invasion, metastasis, epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) and drug resistance of tumor cells [8, 54]. There are two subtypes of InsR, InsR-A and InsR-B, which differ in their ligand binding and signal transduction properties. InsR-A is associated with the mitotic pathway and binds to IGF-2 and insulin, mainly expressed in cancer and fetal cells; while InsR-B only combines with insulin at physiological concentrations, and mainly regulates glucose homeostasis, leading to major metabolic effects, that are prevailingly expressed in metabolic tissues [55, 56]. Unlike IGF-1R and InsR, due to the loss of intracellular domain, IGF-2R lacks kinase activity, which removes IGF-2 mainly through receptor-mediated endocytosis and lysosomal degradation, preventing it from activating InsR and IGF-1R, thereby disrupting IGF-2 signal transduction [57, 58] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.IGF, insulin and their receptors. IGF is secreted by liver

cells, tumor cells or other cells, while insulin is secreted by islet-

IGFBPs, a type of circulating protein with sophisticated functions, are considered to be a carrier protein regulating the activity of IGFs and can be used as a serum bank for IGFs [9]. In addition to binding IGF through common IGF binding domains, several IGFBPs can also combine with specific membrane receptors and attach to the cell surface or extracellular matrix, ultimately performing a variety of intricate functions through IGF-dependent or IGF-independent mechanisms, including cell proliferation, movement, and tissue remodeling [49, 59, 60]. IGFBP2 is the second most abundant IGFBP in the circulation. Several studies have shown that IGFBP2 is overexpressed in various tumors [60, 61, 62, 63, 64]. However, another study demonstrated that the expression of IGFBP2 and IGFBP4 in PC-9DR2 cell lines with dual resistance to MET-TKI and gefitinib is deceased [65], indicating that the role of IGFBP2 is complicated. IGFBP3 is the staple IGF carrier protein in serum [66], with both stimulating and inhibiting effects on the biological activity of IGF, but little is known about these biological switches. IGFBP3 has long been considered a strong negative regulator of IGF-1R activity [67]. Studies have shown that deficiency of IGFBP3 expression results in resistance to osimertinib in NSCLC [68]. In contrast, other studies have demonstrated that enhancive expression of IGFBP3 results in resistance to afatinib in lung adenocarcinoma [66]. The increase of IGFBP3 and IGFBP5 was also found to contribute to the resistance of neuroblastomas to TKI [69]. Therefore, the effect of IGFBP3 on TKIs resistance is complicated. The function of IGFBP7, similar to that of IGFBP2 or IGFBP3, is complex. Studies have found that IGFBP7 can compete with IGFs to combine with IGF-1R, thereby inhibiting the activation of IGF-1R [70]. Another study found that the content of IGFBP7 is reduced in half of metastatic breast cancers, and the abnormal activation of IGFBP7 can inhibit the activation of the MAPK pathway [35], implying that IGFBP7 may negatively regulate the IGF pathway. On the contrary, overexpression of IGFBP7 has been shown to prevent tumor cell apoptosis, resulting in EGFR-TKIs resistance in lung cancer cells [71]. These findings demonstrate that IGFBPs have dual effects on tumor development, drug resistance of TKIs, and activation of the IGF pathway. The relevant biological switch is still unclear, and future studies need to further explore the mechanism. A variety of IGFBPs with similar structure and function have been shown in separate studies to be involved in regulating cell sensitivity to EGFR-TKI along. It is not clear whether their relationship is independent, synergistic, or antagonistic in this context. Therefore, we need more systematic and comprehensive research.

The IGF pathway is involved in various processes of tumor growth, such as tumor proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and EMT [8]. Nuclear IGF-IR can also regulate gene expression [9], which is related to the involvement of the IGF pathway in resistance to chemotherapy, radiotherapy and targeted therapy. In this section, we discuss the mechanism of the IGF pathway to acquired resistance to TKIs from three aspects: (1) The IGF pathway is involved in the activation of the EGFR compensatory signaling pathway. Although EGFR-TKIs can still inhibit the phosphorylation of mutant EGFR, drug-resistant cells maintain activation of downstream signaling pathways through other pathways. (2) The IGF pathway promotes the activation of EMT and integrin pathways, which in turn promotes tumor growth, metastasis and drug resistance, leading to tumor progression. (3) Activation of the IGF pathway can inhibit apoptosis or cell cycle arrest caused by targeted drugs, leading to sustained growth of tumor cells and resistance to TKIs.

When the dominant pathway is blocked, cancer cells are able to activate alternative signaling pathways to maintain cell survival and proliferation [72]. Key downstream signaling pathways shared by many receptor and non-receptor tyrosine kinases such as ERK or AKT, can be activated by a variety of RTKs. As a result, when the EGFR pathway is blocked by TKIs, other RTKs, including the IGF signaling pathway, are alternatively upregulated, which directly activate downstream ERK or AKT signaling pathways to compensate for the lack of EGFR signal transduction function. The resistance to TKIs mediated by this process is independent of EGFR [73]. For example, a study has shown that the IGF pathway can activate AKT and phosphorylate PRAS40 (an AKT substrate, 40 kD and rich in proline) to stop its inhibition of mTOR, and then enhance mTOR signaling [27], resulting in continued cell proliferation and resistance to EGFR-TKIs [74]. Another study also found that the increased expression of IGFBP3 can enhance the expression of MET and phosphorylation of ERK by activating the IGF-1R pathway, which causes afatinib resistance in lung adenocarcinoma [66].

In addition, some tyrosine kinases can also be activated by a portion of overexpressed RTKs. It has been shown that overexpression of IGF-1R, EGFR, HER2 and HER3 can activate Src, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, which has been verified to be a key mediator of trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer [75, 76]. In conclusion, IGF-1R can induce trastuzumab resistance in HER2+ breast cancer by enhancing Src kinase activity [17].

In addition to its IGF-dependent mechanisms, IGFBPs can perform diversified

functions through non-IGF-dependent mechanisms [49, 59]. IGFBP3 has been shown to

activate the TGF-

IGF-1R can interact with the receptors of the ERBB family, and EGFR and IGF-1R can form heterodimers due to their similar extracellular domain structure [52]. Studies have shown that gefitinib [79] and erlotinib [80] can induce a direct interaction between IGF-1R and EGFR, which promotes the formation of the IGF-1R/EGFR heterodimer, thereby activating the IGF-1R pathway, causing an increase in the expression of survivin, and ultimately, resulting in acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs. Closer binding of heterodimers results in stronger recovery of downstream signaling pathways, which negatively affects the efficacy of inhibitors [53]. The basal level of IGF-1R expression is important for initiating the formation of this heterodimer [79]. A study also found that IGF-2 is overexpressed in Herceptin-resistant breast cancer cells [81]. As a result, a large number of IGF-2 binds to IGF-1R to facilitate IGF-1R phosphorylation and activation, resulting in changes in its configuration, which promotes the interaction between activated IGF-1R and HER2 to form a heterodimer on the surface of the cell and accelerate its phosphorylation, activate its tyrosine kinase activity and downstream signaling pathways, and ultimately affect the sensitivity of cells to trastuzumab. Similarly, the heterodimerization also leads to gefitinib resistance in colon cancer cells [82]. Other than heterodimer, HER2/HER3/IGF-1R can also form heterotrimer [83], resulting in enhanced activity of downstream PI3K/Akt, Src kinase and other signaling pathways.

It has been demonstrated that EMT is closely related to tumor metastasis and

drug resistance [84]. The IGF system can regulate the EMT process [85]. Several

studies have verified that activation of the IGF pathway may facilitate drug

resistance by promoting EMT. For example, a study found that in PC-9/GR

(gefitinib resistance) cells and H460/ER (erlotinib resistance) cells, IGF-1R can

upregulate the expression of Snail by activating the ERK/AKT pathway (Snail is

the main regulator of EMT [85]), which promotes the transport of

IGFBP2 has been found to be involved in integrin pathways [91, 92]. Integrins mediate cell adhesion and transmit mechanical and chemical signals to the interior of the cell to drive multiple stem cell functions, including tumor initiation, epithelial plasticity, metastatic reactivation, and resistance to therapies targeting oncogene and immune checkpoint. In tumor tissues, various mechanisms can deregulate integrin signaling, allowing tumor cells to proliferate unchecked, invade across tissue boundaries, and survive in heterogeneous microenvironments [93]. IGFBP2 contains Gly-Arg-Asp (RGD) and heparin-binding sequences, which directly bind integrins and extracellular matrix to trigger biological behaviors independent of IGFs, that promote tumor progression through activation of integrin pathways [94, 95]. Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is an important member of integrin-mediated signal transduction [96]. A study has shown that overexpression of IGFBP2 promotes FAK phosphorylation, leading to dasatinib resistance in NSCLC cells [60].

Evidence accumulated in recent years indicates that, in addition to typical

cell-surface localization pattern and ligand-activated mechanism of action,

IGF-1R is present in the cell nucleus of both normal and cancer cells [97, 98, 99].

Nuclear translocation of IGF-1R is attained via proteosomal, lysosomal and

endocytic pathways, and importin-

In addition to the nuclear IGF-1R pathway, IGF-1R on the cell surface can also activate the AKT-dependent survival pathway through the classic ligand-activated mechanism of action, and participate in the resistance of tumor cells to EGFR-TKIs [102]. It is known that p27 is a cell cycle regulator and it can induce cell cycle arrest by impairing the ability of cyclin E to promote G1-S phase transition, which is mainly regulated by the amount of nuclear p27. It has been shown that TKIs can induce cell cycle arrest by promoting the expression of nuclear p27, thus preventing the continuous proliferation of tumor cells [103]. The IGF pathway can activate AKT, which phosphorylates p27 at T157, resulting in cytoplasmic isolation of p27 and a significant decrease in the number of nuclear p27, ultimately contributing to continued cell proliferation and EGFR-TKIs resistance [104]. Furthermore, PRAS40, a substrate of AKT, can be phosphorylated as a result of the activation of AKT by the activated IGF pathway, and that phosphorylated PRAS40 can interact with forkhead box O3 (FOXO3a) to decrease the transcription of apoptotic genes [28], ultimately leading to continued cell proliferation and EGFR-TKIs resistance [74].

It has also been demonstrated that the overexpressed IGFBP7 can inhibit the activity of pro-apoptotic protein caspase and the expression of B-cell lymphoma-2-like 11 (BIM), thus restraining the apoptosis of tumor cells, and finally, leading to the resistance of EGFR-TKIs in lung cancer [71].

The above reported drug resistance mechanisms are related to the role of the IGF pathway in promoting tumorigenesis and development, promoting EMT, and regulating gene expression with atypical functions of nuclear IGF-1R, which belong to the non-target-dependent resistance mechanism of TKIs. Whether the IGF pathway can regulate the expression of target genes through other mechanisms, and then lead to cell resistance to TKIs through a target-dependent mechanism is still unknown. In addition, the mechanism by which the expression levels of various molecules in the IGF pathway are altered in tumor tissues is another topic worthy of discussion. Since the IGF pathway molecules can regulate the resistance of cells to TKIs in different mechanisms, future studies can focus on whether the factors or diseases that affect the expression levels of IGFBPs and IGF-1/2 in vivo will affect the therapeutic effect of TKIs, so as to help better guide medication and predict efficacy.

The activation of the IGF signaling pathway is related to the acquired resistance to TKIs in cells. As a result, the combination of IGF pathway inhibitors and TKIs has emerged as an effective strategy to prevent drug resistance. A number of studies have demonstrated that blocking the IGF pathway can reverse the resistance of TKIs. Jung-Min Choi et al. [105] demonstrated that in EI24-mediated PC9 resistance to gefitinib, the efficacy of EGFR-TKI could be improved by co-inhibiting the IGF-1R pathway by using the IGF-1R small molecule inhibitor PQ-401 or AG-1024. They also found that AG-1024 enhanced the growth inhibition and pro-apoptotic effect of gefitinib in drug-resistant H1650 cells [42]. In addition, Juan Zhou et al. [86] found that the IC50 of gefitinib and erlotinib in PC-9 derived gefitinib resistant cells and H460 derived erlotinib resistant cells were significantly reduced after silencing IGF-1R expression by siRNA, suggesting that IGF-1R plays an important role in restoring the sensitivity of cells to gefitinib or erlotinib. Browne et al. [106] observed that in trastuzumab-resistant or sensitive HER2+ breast cancer cells (BT474, BT474/Tr, SKBR3, SKBR3/Tr), the efficacy of trastuzumab was improved by using siRNA or IGF-1R TKI NVP-AEW541 to inhibit the expression of IGF-1R. These studies suggest that blocking the IGF pathway may improve the efficacy of TKIs in drug-resistant cells. However, in vivo evidence for this conclusion is lacking. Relevant animal experiments can be designed for future research, including using IGF inhibitors.

These studies have demonstrated that the IGF signaling pathway affects drug resistance of tumor cells. There are three major strategies to design drugs that block the IGF signaling pathway for clinical anti-tumor treatment: receptor blocking, kinase inhibition, and ligand isolation (Table 2, Ref. [107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146]) [147]. Among them, mAb is the most commonly used strategy for receptor blocking in clinical studies. The ideal IGF-1R antagonist mAb, with strong specificity in epitope recognition, does not bind to InsR, which avoids side effects such as insulin resistance and hyperglycemia caused by targeting InsR-B. Nevertheless, IGF-1R mAb does not block the activation of InsR-A [148]. InsR-A is capable of binding to IGF-2 to activate downstream signaling pathways, which is a potential cause of drug resistance to IGF-1R mAb. Currently, commonly used IGF-1R mAbs are: cixutumumab (IMC-A12) and ganitumab (AMG-479). Inhibition of tyrosine kinases is another therapeutic strategy targeting the IGF pathway. Since the major sequences of kinase domains of the IGF system receptors are similar, and the sequences of their ATP-binding pocket are almost absolutely conformed [149], kinase inhibitors can theoretically inhibit virtually all IGF receptors. This suggests the possibility of synthesizing drugs that target both the IGF pathway and the EGFR pathway. Such drugs include linsitinib (OSI-906) and BMS-754807. OSI-906 is a dual IGF-1R/InsR inhibitor. Since kinase inhibitors may impair the action of InsR-B, they may cause adverse effects on normal metabolism. The third strategy is ligand isolation using anti-ligand mAb or recombinant IGFBPs, such as dusigitumab (MEDI-573), and xentuzumab (BI 836845). Compared with the other two anti-IGF pathway strategies, ligand isolation does not result in severe metabolic disorders in preclinical animal models [150].

| Drug type | Compound | Preclinical studies |

| Monoclonal antibodies | Cixutumumab (IMC-A12) | [107, 108, 109] |

| Ganitumab (AMG-479) | [110, 111, 112, 113] | |

| Figitumumab (CP-751871) | [114, 115, 116, 117] | |

| Dalotuzumab (MK-0646) | [118] | |

| Teprotumumab (R1507) | [119, 120] | |

| Small molecule inhibitors | Linsitinib (OSI-906) | [121, 122, 123, 124] |

| BMS-754807 | [122, 125, 126, 127] | |

| Picropodophyllin (AXL1717) | [128, 129, 130, 131] | |

| NT157 | [132, 133] | |

| AG-1024 | [134] | |

| NVP-AEW541 | [135, 136, 137] | |

| NVP-ADW742 | [138, 139, 140] | |

| GSK1904529A | [141, 142, 143] | |

| Ligand neutralization | Dusigitumab (MEDI-573) | [144] |

| Xentuzumab (BI 836845) | [145, 146] |

Many clinical trials have begun to evaluate the efficacy of drugs targeting the

IGF pathway (Table 3, Ref. [151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173]). Several clinical trials using combined

therapy with cetuximab in the treatment of lung or breast cancer have shown no

significant clinical benefit. Notably, combined treatment significantly increases

the incidence of adverse hyperglycemic reactions (NCT01232452, NCT00870870,

NCT00955305, NCT00684983). Another clinical trial demonstrated that the survival

rate of patients with recurrent small cell lung cancer treated with linsitinib

(OSI-906) alone was significantly lower than that treated with the

chemotherapeutic drug topotecan (NCT01533181) [174]. Furthermore, other clinical

studies on OSI-906 have not yet resulted in satisfactory outcomes

[151, 152, 175, 176]. A clinical trial on the combination of xentuzumab, a dual

anti-IGF-1/2 neutralizing antibody, in breast cancer patients showed that the

combination of xentuzumab on the basis of everolimus or exemestane did not

improve the PFS of the overall population, resulting in an early cessation of the

trial (NCT03659136) [153]. Therefore, IGF-1R mAb treatment is largely ineffective

in unselected cancer patients. A few clinical trials have suggested that IGF-1R

targeted therapy may be beneficial only in specific cancer patients [154, 177].

Several preclinical studies suggested potential predictive biomarkers, such as

BRCA1,

| Drugs | Combination | Cancer type | Phase | Participants | Results |

Ref. or trial ID |

| Dalotuzumab | Irinotecan, cetuximab | Chemorefractory, KRAS exon 2 mutant colorectal cancer | II/III | 69 | ORR, 5.6%. Median PFS, OS were not statistically significantly different with dalotuzumab alone or placebo. | [155] |

| Dalotuzumab | Erlotinib | Refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer | I/II | I 20 | II, ORR, 2.7%. No significant difference in PFS, OS, compared to erlotinib. | [156] |

| II 75 | ||||||

| Dalotuzumab | Pemetrexed, cisplatin | Untreated non-squamous lung cancer stage IV | II | 26 | PR, 25%. SD, 33.33%. PD, 33.33%. | [157] |

| NCT00799240 | ||||||

| Dusigitumab | None | Advanced solid tumors | I | 43 | CR, 0. PR, 0. SD, 33.33%. | [158] |

| Figitumumab | Erlotinib | Stage IIIB/IV or recurrent disease with nonadenocarcinoma histology | II | 583 | OS, 5.7 months. Median PFS, 6.2 months. No improvement, compared to erlotinib. | [159] |

| NCT00673049 | ||||||

| Figitumumab | Paclitaxel, carboplatin | Stage IIIB/IV or recurrent NSCLC disease with nonadenocarcinoma histology | III | 681 | OS, 8.6 months. Median PFS, 4.7 months. ORR, 33%. No improvement, compared to paclitaxel, plus carboplatin. | [160] |

| Figitumumab | Docetaxel or prednisone | Progressing castration-resistant prostate cancer | II | 204 | Median PFS was 4.9 months, with HR = 1.44 (95% CI, 1.06–1.96), compared to docetaxel/prednisone alone. | [161] |

| Ganitumab | None | Metastatic progressive carcinoid or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors | II | 60 | Median PFS, 6.3 months (95% CI, 4.2–12.6). OS at 12 months was 66% (95% CI, 52–77%). | [162] |

| Ganitumab | Gemcitabine | Previously untreated metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma | II | 125 | OS at 6 months was 57% (95% CI, 41–70%). | [163] |

| Teprotumumab | Erlotinib | Progressing advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | II | 172 | 12-week PFS rates were 39%, 37%, and 44%, and median OS was 8.1, 8.1, and 12.1 months for the three groups (erlotinib plus placebo, or R1507 weekly, or R1507 every 3 weeks), respectively. | [154] |

| Teprotumumab | None | Recurrent or refractory soft tissue sarcomas | II | 163 | ORR, 2.5% (95% CI, 0.7–6.2%). Median PFS, 5.7 weeks. Median OS, 11 months. | [164] |

| Teprotumumab | None | Refractory or recurrent Ewing sarcomas | II | 115 | CR or PR, 10% (95% CI, 4.9–16.5%). Median OS, 7.6 months (95% CI, 6–9.7 months). | [165] |

| Xentuzumab | Afatinib | Previously treated EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC | I | 32 | ORR, 0. Median SD, 2.3 months (95% CI, 0.8–10.9 months). | [166] |

| NCT02191891 | ||||||

| Xentuzumab | Everolimus, exemestane | Hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative locally advanced and/or metastatic breast cancer | Ib/II | II 140 | Median PFS, 7.3 months, with HR = 0.21 (95% CI, 0.05–0.98, p = 0.0293), compared to everolimus plus exemestane. | [153] |

| I, NCT02123823 | ||||||

| II, NCT03659136 | ||||||

| Linsitinib | None | Locally advanced or metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma | III | 139 | Median OS, 323 days (95% CI, 256–507 days). No significant difference, compared to placebo. | [151] |

| NCT00924989 | ||||||

| Linsitinib | None | Wild type gastrointestinal stromal tumors | II | 20 | ORR, 0. CBR at 9 months was 40%. 9 months PFS, 52%. 9 months OS, 80%. | [152] |

| Picropodophyllin | None | Advanced solid tumors | Ia/b | Ia 20 | For 15 NSCLC patients, the median PFS was 31 weeks and the OS was 60 weeks. | [172] |

| Ib 39 | NCT01062620 | |||||

| Picropodophyllin | None | Previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC | II | 99 | 12-weeks PFS, 29%, ORR, 0. Estimated median OS, 38.7 weeks. No improvement, compared to docetaxel. | [167] |

| Cixutumumab | Capecitabine, lapatinib | HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer previously treated with trastuzumab | II | 68 | Median PFS, 5.0 months. Median OS, 21.9 months. No improvement, compared to capecitabine plus lapatinib. | [168] |

| NCT00684983 | ||||||

| Cixutumumab | Bevacizumab | Stage IV or recurrent non-squamous, NSCLC | II | 175 | Median PFS, 7.0 months. ORR, 58.7%. Median OS, 16.1 months. The addition of cixutumumab increased toxicity without improving efficacy. | [169] |

| NCT00955305 | ||||||

| Cixutumumab | Doxorubicin | Advanced soft tissue sarcoma | I | 30 | Estimated PFS, 5.3 months (95% CI, 3.0–6.3 months). | [173] |

| NCT00720174 | ||||||

| Cixutumumab | Androgen deprivation (AD) | New metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer | II | 210 | NO statistical difference between AD and AD plus Cixutumumab in OS or PFS. | [171] |

| Cixutumumab | Cetuximab | Recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | II | 91 | Median PFS, 2.0 months. CBR, 15.3%. No improvement, compared to cetuximab alone. | [170] |

Though the anticancer efficacy of the drugs targeting the IGF pathway is promising in preclinical models, the results of clinical trials have been disappointing. Up to now, there has not been any anti-IGF-1R mAb approved as a cancer drug treatment by the FDA. The following three issues need to be addressed when considering targeting the IGF pathway as a therapeutic strategy. (1) The poor response of selective IGF-1R targeting drugs may be primarily due to the compensation of the activated InsR pathway or the reduction of cellular IGF-1R [51]. As a consequence, inhibition of InsR appears to be imperative, and future research will focus on developing InsR inhibitors that target cancer cells. (2) There is a lack of predictive biomarkers to select patients who will benefit from targeted therapy. Therefore, a large number of marker studies are needed to confirm the appropriate screening method for selecting patients suitable for IGF pathway-targeted therapy. (3) Drugs can cause adverse effects on normal metabolism by impairing the physiological action of InsR, leading to side effects such as metabolic disorders and hyperglycemia. Therefore, when targeting IGF-1R or InsR to treat cancers, alterations in InsR-B function should be avoided. When these issues are resolved, targeting InsR-A may become a promising strategy to exert antitumor effects without causing severe metabolic side effects.

TKIs can interfere with the signal transduction of tumor cells, and inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells and neovascularization, with little effect on normal cells [2], making it a promising clinical therapy for cancer patients. A growing number of TKI are being approved by the FDA to treat tumors. The most widely and successful used TKIs are EGFR-TKIs and HER2-TKIs, which are mainly used in the targeted therapy of lung and breast cancers. Although the application of TKIs has brought great hope to a large number of patients, most will inevitably develop drug resistance. The resistance mechanisms of TKIs are complicated, which can be divided into target-dependent resistance mechanisms and non-target-dependent resistance mechanisms. It has been shown that the activation of the IGF signaling pathway can impact the sensitivity of cells to TKIs. The IGF pathway contributes to acquired resistance to TKIs primarily by promoting the activation of compensatory signaling pathways, promoting the activation of EMT and integrin pathways, and regulating the cell cycle and apoptosis. A variety of drugs targeting the IGF pathway have been designed for cancer therapy. Although the anticancer efficacy of the drugs targeting the IGF pathway is promising in preclinical models, the results of clinical trials have been disappointing, limiting the current clinical application of IGF pathway inhibitors.

In order to address drug resistance to EGFR-TKIs caused by the IGF signaling pathway, simultaneously targeting the IGF pathway and EGFR may be an effective strategy. One option is to combine drugs to augment the response time of targeted agents, such as the combination of IGF pathway inhibitors and TKIs for cancer treatment. In addition, single-molecule drugs that inhibit multiple correlative kinases can be developed, such as small molecule inhibitors that target both the IGF and EGFR pathways, to improve efficacy and reduce toxicity. This will require more in-depth basic and clinical research studies.

YP wrote the original draft, draw the figures, and acquired, initially analyzed, and visualized data from the reviewed literature. JT edited the review, conceptualized and interpreted the data from the reviewed literature. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The author thanks current members of the laboratory for their valuable contributions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.