Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark (FBL) is published by IMR Press from Volume 26 Issue 5 (2021). Previous articles were published by another publisher on a subscription basis, and they are hosted by IMR Press on imrpress.com as a courtesy and upon agreement with Frontiers in Bioscience.

1 Departamento de Parasitologia, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, CP 04510, Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico

2 Departamento de Farmacologia, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, CP 04510, Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico

3 Laboratorio de Genotoxicología y Mutagenesis Ambiental, Departamento de Ciencias Ambientales, Centro de Ciencias de la Atmosfera, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico CP 04510, Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico

4 Unidad de Investigacion Medica en Enfermedades Infecciosas y Parasitarias, Centro Medico Nacional Siglo XXI, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, 06720, Cd de Mexico, Mexico

5 UIM en Inmunologìa, Hospital de Pediatrìa, CMN S XXI, IMSS, 06720, Cd de Mèxico, Mexico

6 Departamento de Inmunologìa, Instituto de Investigaciones Biomedicas, Universidad Nacional Autònoma de Mèxico, 04510, Cd de Mexico, Mexico

Abstract

Bisphenol A (BPA) is an endocrine-disruptor compound that exhibits estrogenic activity. BPA is used in the production of materials such as polycarbonate plastics, epoxy resins and dental sealants. Whereas, the endocrine modulating activity of BPA and its effects on reproductive health have been widely studied, its effects on the function of the immune system are poorly characterized. This might be attributable to the different BPA doses used in a diversity of animal models. Moreover, most studies of the effect of BPA on the immune response are limited to in vitro and in vivo studies that have focused primarily on the impact of BPA on the number and proportion of immune cell populations, without evaluating its effects on immune function in response to an antigenic challenge or infectious pathogens. In this review, we discuss the current literature on the effects of BPA on the function of immune system that potentially increases the susceptibility to infections by the virtue of acting as a pro-inflammatory molecule. Thus, it appears that BPA, while by such an impact might be useful in the control of certain disease states that are helped by an inflmmatory response, it can worsen the prognosis of diseases that are adversely affected by inflammation.

Keywords

- Review

- Environmental pollution

- Environmental medicine

- Endocrine disruptors

- Bisphenol A

- Immunoregulation

- Infection

- Review

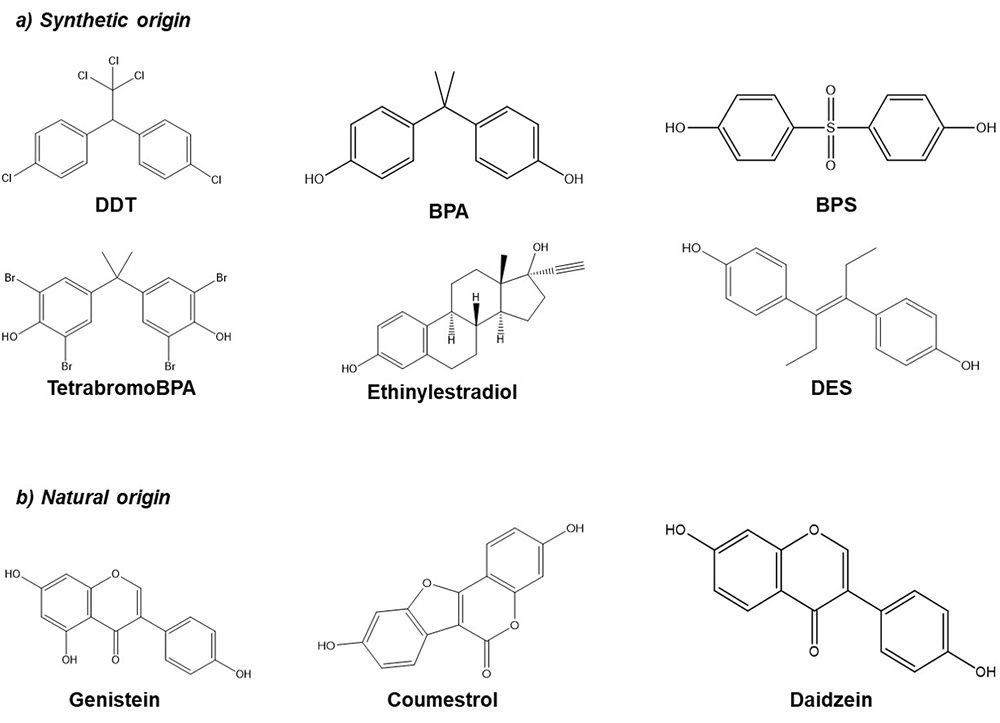

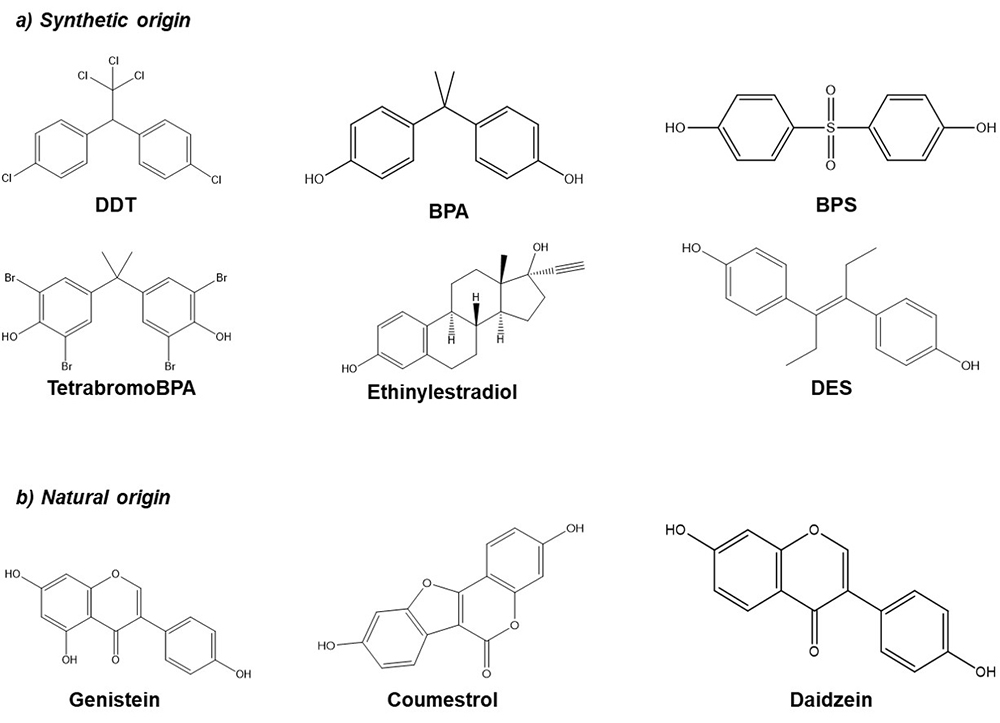

Endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) are substances that exist in the environment as a result of agricultural and industrial activity. Some examples are dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), Bisphenol A (BPA), Bisphenol S (BPS), phthalates, among others, but they also can be found in pharmaceutical products (ethinylestradiol, diethylstilbestrol (DES)) or naturally in different plants such as soybean (phytoestrogens, genistein, daidzein, coumestrol) (Figure 1). EDCs may exhibit estrogenic, anti-estrogenic or anti-androgenic activity. In addition, these compounds are highly lipophilic and can be stored for prolonged periods of time in the adipose tissues. During pregnancy, the fetus can be exposed to these compounds through the placenta and at birth by the lactogenic route (1, 2).

Figure 1

Figure 1Chemical structure of several EDCs. a) Synthetic origin; Dichloro-Diphenyl-Trichloroethane (DDT), Bisphenol A (BPA), Bisphenol S (BPS), Tetrabromo Bisphenol A (TetrabromoBPA), Ethinylestradiol, Diethylstilbestrol (DES). b) Natural origin; Genistein, Coumestrol, Daidzein.

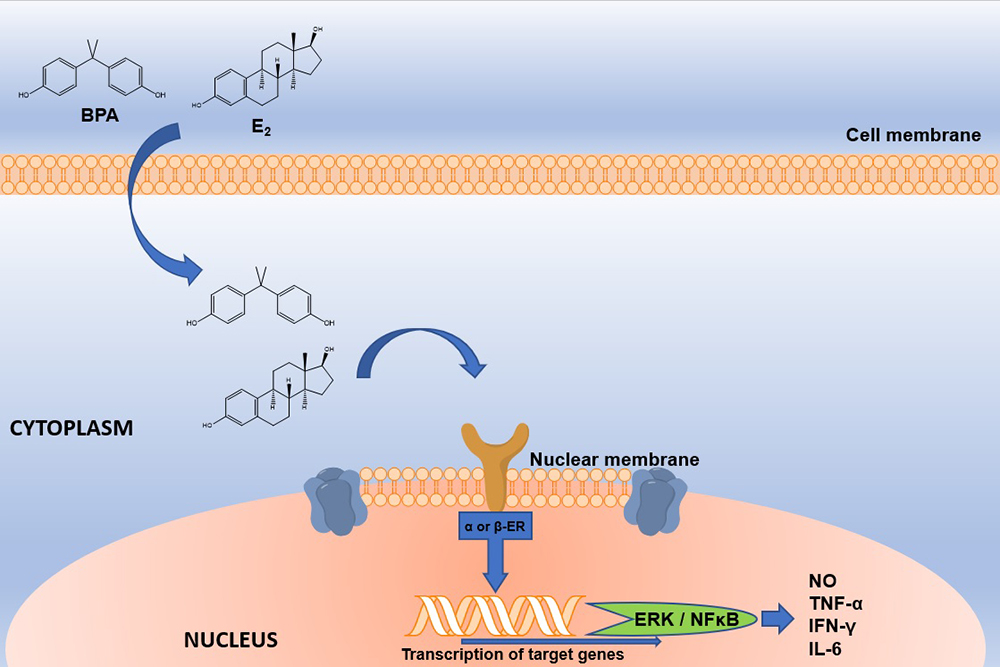

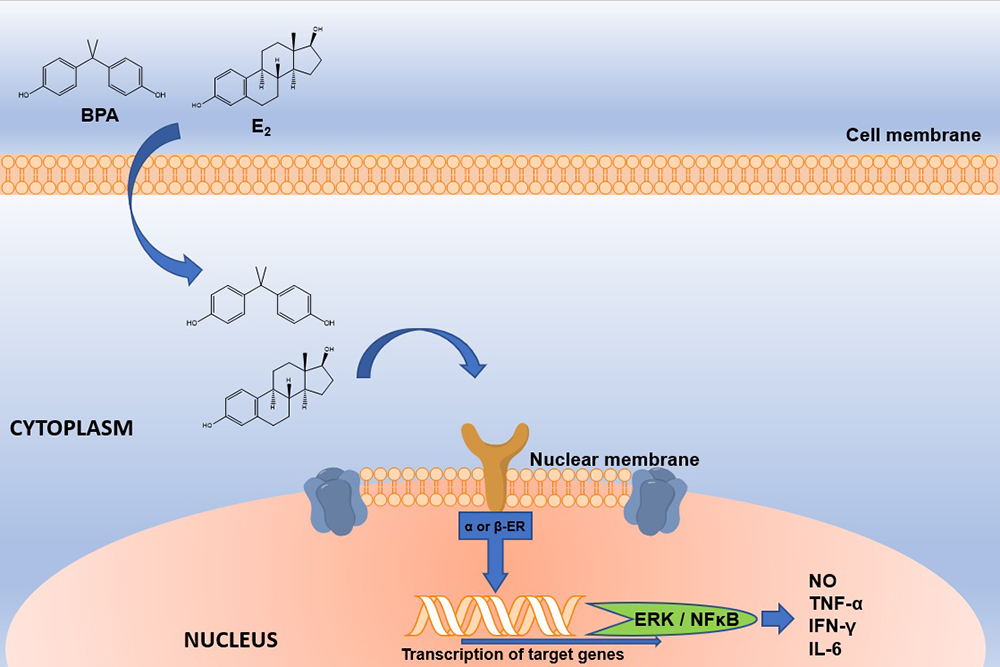

BPA is widely used as a monomer in the production of polycarbonate plastics, epoxy resins and dental sealants (4). This compound can be released easily from these materials due to incomplete polymerization or hydrolysis of the polymers that contain it, which can occur when they are exposed to high temperatures, acidic conditions or enzymatic process. The main BPA exposure source in animals and humans is through out food and beverages that have been in contact with materials manufactured with BPA, which is detached from its matrix and it is ingested orally (5). BPA is classified as an EDC with estrogenic character since it can bind to nuclear estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) and trigger signaling pathways, even when its affinity is lower (<1,000) than the endogenous ligand, 17β-estradiol (Figure 2) (6). In addition, BPA also binds to the estrogen like G-coupled protein receptor (GPER), the estrogen related receptor gamma (ERRγ), the arylhydrocarbon receptor (AhR) (7), the thyroid hormone receptor (ThR) (8), the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) (9), the glucocorticoid receptor and the thyroid hormone receptor (TR) (8–15). Despite the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) calculated that the Tolerable Daily Intake of BPA is 50 μg / kg / day, it has been estimated that exposure to BPA per food package is 0.185 μg / kg / day in adults and up to 2.42 μg / kg / day in children from 1 to 2 months of age (8). Besides, it has been demonstrated that BPA exposure at the tolerable concentrations or below is related to negative effects in the health of both, humans and rodents (13, 16, 17).

Figure 2

Figure 2Schematic representation of E2 and BPA interaction with nuclear ERs. E2 or BPA interacts with nuclear ERs. BPA; Bisphenol A, E2; Estradiol; ERα or β; Estrogen receptor alpha or beta. The interaction between BPA and ER will activate genes such as ERK and NFκB, which will generate the production of proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide. BPA; Bisphenol A, E2; Estradiol, ER; Estrogen Receptor, ERK; extracellular signal-regulated kinases; NFκB; nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, NO; Nitric Oxide.

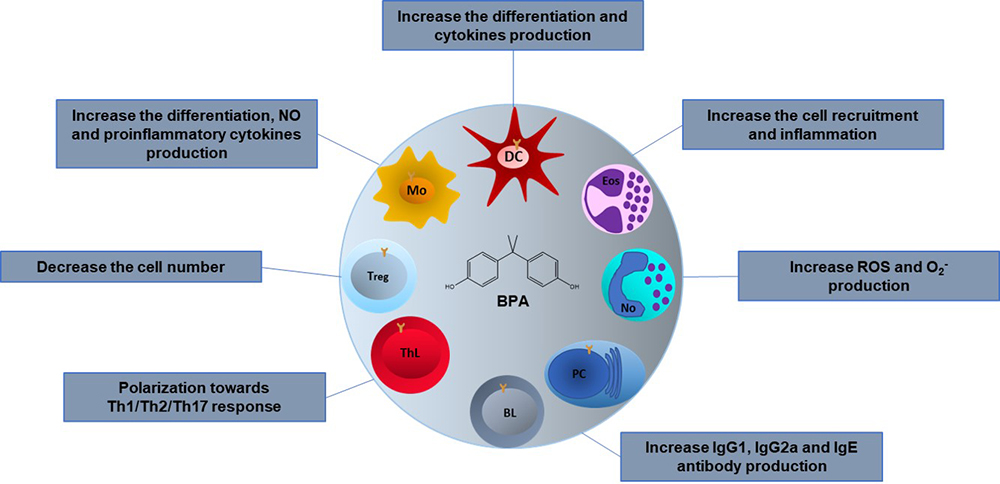

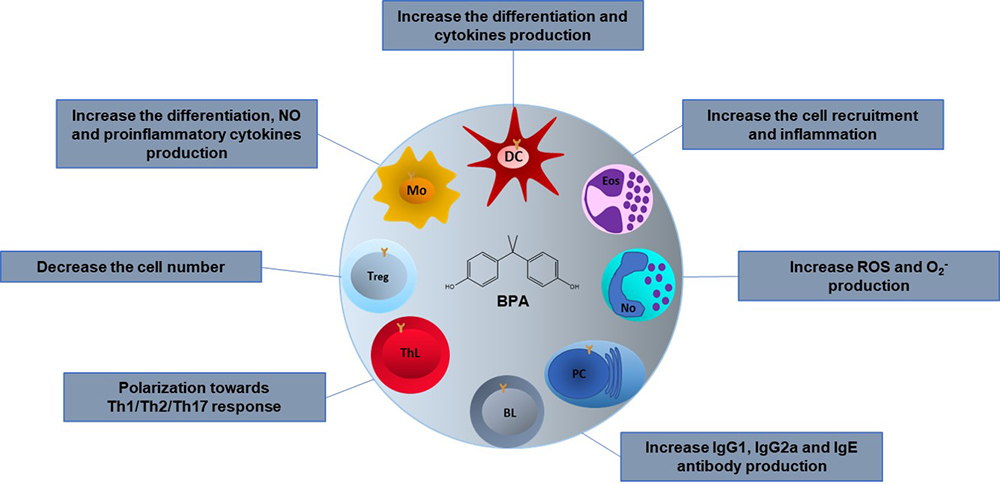

Different BPA effects have been reported on the immune system cells; however, they vary depending on whether they were performed as in vivo or in vitro. In vivo, the effects reported may seem contradictories, but they are not, since the reported effects depend on the animal species used, the dose, the administration route, the sex of the animal, the age, and the animal’s development stage in which BPA is administered. Furthermore, many reports do not consider that the immune response must be studied by challenging the immune components, so there is little information about the BPA effects on the immune response during an infectious process. In the next paragraphs, we summarize the reported BPA effect on all the immune cells reported to date. To make it more comprehensive, we divide them in innate and adaptive immune cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Figure 3Effects of BPA on the cells of the immune system. The BPA effects in different immune cells are variable depending on the type of model, in vivo or in vitro, the animal species used, the dose, the administration route and the stage of development in which it is administered. Mo; Macrophages, DC; Dendritic cells, Eos; Eosinophils, No; Neutrophils, PC; Plasma cells, BL; B lymphocytes, ThL; T helper lymphocytes, Treg; T regulatory lymphocytes

Macrophages are one of the main phagocytic cells that play an important role in the maintenance of organism homeostasis. Furthermore, they express the two ER isoforms (ERα and ERβ) whereby BPA could exert its effects (18, 19). On line with that, different studies have evaluated the BPA stimulatory effects on macrophages. Hong et al. (2004) reported that BPA at a concentration of 43 nM potentiated nitric oxide production (NO) in a murine macrophage cell line (RAW264), after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) exposure; while interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) production was not altered (20). Other experiments developed by Yamashita et al. (2005) described that BPA at a concentration of 0.1 μM stimulated pro-inflammatory cytokines production such as IL-1, IL-6 and IL-12, also BPA treatment increased the co-stimulatory molecule CD86 expression in murine peritoneal macrophages (21). In concordance with this study, mouse peritoneal macrophages under M1 type conditions that were exposed to low concentrations of BPA (> 1 μM) promotes polarization toward M1 subtype by the upregulation of IRF5 expression, as well as TNF-α, IL-6 and MOP-1; while the same BPA exposure to macrophages under M2 type conditions inhibits the M2 subtype polarization by the downregulation of IL-10 and TGF-β (22). In addition, a BPA analog (BPA-glycidyl-methacrylate (BisGMA)) stimulated Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-α) production with a concomitant increase of surface molecules (CD11, CD14, CD40, CD45, CD54 and CD80) expression on a macrophage cell line (RAW264.7). Like BPA, the BisGMA induced the production of IL-1β, IL-6, and NO, as well as the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and raised the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) intra and extracellular in a dose-dependent manner (23).

The increment of IL-6 and TNF-α secretion stimulated by BPA (0.1 μM) was also observed in a human macrophage cell line (THP1), on the contrary, secretion of regulatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β was decreased by BPA treatment. Moreover, the treatment of an ER antagonist (ICI 182,780) reversed this cytokine production pattern, indicating that BPA effects are carried out by its binding to ERs (24). Interestingly, BPA can induce alternative macrophages activation (M2), reducing IL-6, IL-10 and IL-1β production in macrophages derived from human peripheral blood monocytes (PBMCs), stimulated or not with LPS or IL-4. This work also reported that BPA treatment increased the IL-10 and decreased the IL-6 production in macrophages classically activated (M1) (25). Finally, a work of Yang et al. (2015) reported that BPA increased the production of NO and ROS in a dose-dependent manner in carp (Cyprinus carpio) macrophages (26).

On the other hand, inhibitory BPA effects on macrophages function have also been reported. Segura et al. (1999) evaluated the adhesion capacity of the peritoneal macrophages of rats after BPA treatment, this compound (10 nM) inhibited the macrophages adherence but it did not have effect on their viability (27). In another study, Kim and Jeong (2003) evaluated the effect of BPA on the production of NO, TNF-α and iNOS expression in mice peritoneal macrophages. BPA (50 μM) did not affect the NO and TNF-α production. On the contrary, when LPS was used as stimuli, BPA treatment inhibited their production. In addition, BPA decreased the iNOS expression in a dose-effect dependent manner (28). Supporting this fact, Byun et al. (2005) indicated that mice peritoneal macrophages, obtained from mice injected with BPA (500 mg / kg / day) for 5 consecutive days during 4 weeks, and cultured ex vivo with LPS, had a marked reduction in TNF-α and NO production. A similar effect was observed in a macrophage culture treated with BPA (10 and 100 Μm) (29). The BPA cell inhibitory effect was also observed in RAW 264 macrophage cell line, where BPA exposure (100μM) inhibited IFN-β promoter activation after LPS stimulation (30). Moreover, this estrogenic compound also suppressed the NO production and NFƙB activation in the same cell line with the same stimulus. Of note, these effects were blocked by the estrogen receptor antagonist ICI182,780 (31). In line with that, BPA (200 μM) exposure in RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line also shown to inhibit the production of NO and induce apoptosis cell death (32). In summary, BPA alters macrophage functions by decreasing cytokine secretion, activating of M2 phenotype and stimulate the expression of adhesion molecules.

Finally, in a recent study Liu et al (2020), report that BPA (100 μg / L) generates immunotoxicity in macrophages from common carp (Cyprinus carpio), by increasing the expression of long non-coding RNAs (33). This is reflected in the alteration of some signaling pathways related to the immune response, such as: NF-κ B, Toll-like receptor, B-cell receptor and the Jak-STAT signalling pathway (33).

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the par excellence antigen presenting cells; they play a fundamental role in the begining of the immunological response and its polarization and regulation. It has been reported that these cells also express ERα and Erβ (34). Limited studies have investigated the BPA effects on DCs. Guo Y and cols. (2010), reported that treatment of BPA in DCs derived from PBMCs increased the chemokine ligand 1 (CCL1) expression, the IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13 production as well as the expression of the transcription factor GATA3 in the presence of TNF-α (35), demonstrating that the exposure to BPA alters the functions of human DCs by inducing preferentially a Th2 response. Furthermore, BPA affected DCs differentiation by increasing the class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC II) and CD69 expression (36). On the other hand, Švajger et al. (2016), indicated that BPA at a concentration of 50 μM decreased the DCs endocytic capacity as well as the CD1a expression (an important protein mediating antigenic presentation) (37). BPA at low concentrations (1 nM) also increased the DCs density, however, the expression of DCs activation markers (HLA-DR and CD86) was decreased in human DCs derived from PMBCs (38). BPA had no effect neither in cultivated bone marrow precursors or in the proliferation of the DCs, regardles of concentration (39). The works previously described suggest that exposure to BPA affects human DCs function in a concentration dependent manner.

Granulocytes are the most abundant innate immune cells. They are divided into neutrophils, which constitutes between 90 and 95% of their totality, eosinophils from 3 to 5% and basophils less than 1%. In the literature there are few reports about the BPA effect on these cells. In the case of neutrophils, Watanabe et al., (2003) evaluated the effect of BPA on the neutrophilic differentiation induced by dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in a leukemia cell line (HL-60). Tthey reported that low doses of BPA (10-10 and 10-8 M) increased the expression of the CD18 integrin protein, the neutrophilic differentiation as well as superoxide production. Interestingly, the treatment with an estrogen receptor inhibitor (tamoxifen) in these cells, did not suppress the BPA effect, suggesting that all the effects above are mediated by an ER-independent pathway (40). Another BPA-related compound, tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA), also increased the ROS neutrophils production in a dose-dependent manner (41).

BPA exposure has also been found to affect eosinophils, which are key players in allergy and asthma pathogenesis. In vivo experiments, using mouse models of allergic asthma, described that perinatal BPA exposure enhanced eosinophilic inflammation and airway responsiveness (42), suggesting that BPA exposure can affect the disease during critical developmental periods. Similar results were observed when adult mice were sensitized with ovalbumin combined with BPA treatment, where the result of the treatment significantly increased eosinophil recruitment in the alveoli and submucosa of the airways and enhanced eosinophil-produced cytokine and chemokine levels (43). These studies suggest that early or late life exposure to BPA could enhance the severity of immune-mediated diseases such as allergic diseases and asthma.

Mast cells are resident tissue cells that play a key role in inflammatory and allergic processes (44). These cells are characterized by their high content of cytoplasmic granules containing preformed mediators that include the vasoactive amine histamine, proteases, as well as some cytokines (45). Mast cells may be activated by a variety of stimuli through the numerous receptors on their surface. Upon activation, mast cells can release preformed as well as a several distinct newly synthesized mediators (44,45). The most studied mechanism of mast cell activation is the IgE-mediated response, which can be divided into two stages; in the first stage, IgE produced by plasma cells binds to the FcɣRI on the mast cell surface, leading to a sensitized state. Later, upon a second encounter with the antigen, it can bind to the surface-binded IgE, which after crosslink of IgE triggers mast cell degranulation and release of mediators. Though BPA exposure has been linked to allergen sensitization, there is limited information concerning BPA effects on mast cell-response. In a two-generational study, O’Brien reported that perinatal BPA exposure through maternal diet (ranging from 50 ng to 50 mg / Kg diet) caused an increase in mast cell-derived leukotrienes, prostaglandin D2, TNF-α and IL-13, suggesting greater activation of these cells (46). Further studies will be needed to evaluate the role of the BPA exposure on mast cell response and its association to allergic diseases.

T lymphocytes (TL) are cells of the adaptive immune system, they can be divided into cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) or T helper lymphocytes (ThL), which can differentiate into Th1, Th2, Th9, Th17, Th33., based on their secreting cytokines pattern. These cells express different hormone receptors (47), thus sex steroids can regulate the TLs differentiation and their response (48, 49). Some studies have reported that BPA exerts its effects through out the binding to them with a consequent modulation of TL response and polarization (Th1, Th2, and Th17).

In an ex vivo model, Youn et al., (2002) described that BPA induced cell proliferation in Concanavalin A (Con-A)-stimulated splenocytes derived from mice orally exposed to BPA during 4 weeks, with no in ThL, CTL subpopulation percentages. In addition, the IFN-γ and the IL-4 expression was induced and reduced, respectively (50). Moreover, in chicken egg lysozyme (HEL) model, Yoshino et al., (2003) reported that BPA significantly increased the IFN-γ and IL-4 secretion, suggesting that BPA promoted the Th1 response. This cytokine secretion pattern was also reported in prenatally BPA-exposed mice, after being immunized with HEL in the adulthood, however the Th1 cytokine changes observed were greater than the Th2 (51, 52). In accordance with this concept, Alizadeh et al., (2006) reported an increase in IL-12 and IFN-γ production on splenocytes derived from animals exposed to BPA in an OVA-induced allergy model (53). Coupled with this effect, Menard et al., (2014) evaluated the BPA effect on the specific immune response against the OVA antigen, they found that BPA increased the LTh percentages and the IFN-γ secretion (54). It is important to mention that the perinatal BPA exposure (day 9.5 of gestation until weaning), producedchanges in cytokine expression, such as G-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-12p70, IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α and Rantes at serum levels (55). Moreover, this cytokine secretion pattern together with the IL-4 and IL-6 increase was also observed in splenocytes previously stimulated with Con-A. Also, the supernatants of cultured splenocytes were evaluated and the GM-CSF, IFN-γ and IL-17 expression was also increased after LPS stimulus. All the above confirms that BPA impacts on Th1 cytokines with a bias towards a Th17 type response (55).

In mice, BPA exposure administrated in their drinking water during the perinatal period, increased the expression of the transcription factor RORγt, and the cytokines IL-17, IL-21, IL-6 and IL-23 in a dose-dependent manner, in both males and females. (56). This is <in agreement with previously reported data by Holladay et al., 2010. Some studies have reported that BPA was able to generate T cell polarization, directing it to a Th2 response. With respect to this statement, in an in vitro model, lymphocytes exposed to BPA showed an induction of the GATA-3, IL-4 and IL-10 expression and a reduction of the T-box transcription factor (Tbet) expression, suggesting an induction of Th2 polarization (57). Similar effects were reported in activated T lymphocytes with respect to IL-4 expression (58).

Additionally, Miao et al., (2008), using a gestational exposure scheme, reports that exposure to BPA generates a decrease in ERα expression in males, while the expression of this receptor is increased in females and the expression of Th1 cytokines (IL-2, IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α) was decreased in both males and females (59). Sawai et al. (2003) in in vitro experiments on splenocytes stimulated with Con-A, reported that males exposed to BPA, produced on average 40% less IFN-γ while females 28% less compared to controls (60). Regarding on regulatory T cells (Tregs) Ohshima et al., (2007), reported that the perinatal administration of BPAgenerated a decrease in the Tregs number (61).

B lymphocytes (BL) are cells whose importance lies in humoral immunity, since they are able to differentiate into plasmatic cells (PCs), which are responsible for the production of antibodies such as IgA, IgG, IgE, IgD and IgM. In different studies, it has been observed that BPA may modify in a different way the production of antibodies by these cells. Yoshino et al., (2003) using male and female DBA / 1J adult mice, report that BPA generates an increase in the proliferation of splenocytes, in addition to an increase in the production of antibodies in a dose-dependent manner (51). Similarly, in another study, it was reported that gestational exposure to BPA generated increased production of IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies, with predominance of IgG2a antibodies in male offspring (52).

Menard et al. (2014), reported that in female rats exposed perinatally to BPA there is an increase in anti-OVA IgG antibodies during adult life (54). Alizadeh et al. (2006), indicate that exposure toBPA, in female BALB/c mice, generates lower IgE antibody titers and higher levels of IgG2a (53). Similarly, Lee et al. (2003), indicate that there is an increase in IgE in female BALB/c mice exposed to BPA during adult life (58). In another study, using young mice of the strain NZB/NZW (systemic lupus erythematosus murine model), which were exposed to BPA, and later in adult life thethe splenocytes were obtained and stimulated with LPS, there is a decrease in the production of IgG2a in splenocyte culture supernatants (60). Yurino et al. (2004), using BWF1 mice (another model of systemic lupus erythematosus), which were ovariectomized at four weeks of age, and that were subsequently implanted with subcutaneous implants of BPA during four months, reported that the exposure to BPA generates an increase in the production of anti-RBC IgM autoantibodies by B1 cells, as well as ERα expression both in vitro and in vivo (62). Moreover, Goto et al. (2007), administering BPA in the drinking water in male and female mice with transgenic TCR andstimulated with OVA reported an increase in the production of IgG2a and IgA in supernatants of splenocyte cultures from these mice (63). Finally, Midoro-Horiuti et al. (2010), using an asthma model in BALB/c mice, indicated that perinatal exposure of BPA in the drinking water, increases serum levels of anti-OVA IgG (42).

So far, there is only one report about the effects of BPA in the virus infection context. Roy et al. (2012), evaluated the perinatal BPA exposure on the immune response associated with the infection of influenza A virus during adult life on a murine model (Table 1). The report indicated that the perinatal exposure to BPA did not affect the specific adaptive immune response against the influenza virus at the lung. However, this exposure to BPA temporarily reduced the lung inflammation associated to the infection- and also the expression of antiviral genes (IFN-γ and iNOS) in lung tissue: The study concluded that perinatal BPA exposure modulated the innate immune response in the adult mice, but not the adaptive response, which is fundamental for the elimination of the influenza virus (64).

| Pathogen | Mode of administration | Dose | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A | Perinatal | 50 µg/kg/day | Temporary reduction of the degree of pulmonary inflammation | 64 |

| Escherichia coli | Prepuberal | 5 mg/kg/day x 5 days | Increase the number of colonies forming units | 65 |

| Leishmania major | Adult | 5.7, 11.4, 22.8 y 45.6 mg/kg one week before infection | Increase susceptibility in a dose-dependent manner | 68 |

| Leishmania major | Perinatal | 1, 10 y 100 nM | Increase susceptibility in a dose-dependent manner | 68 |

| Trichinella spiralis | Adult | 228 µg/mice | Decreased susceptibility | 69 |

| Nippostrongylus brasiliensis | Perinatal | 5 µg/kg/day | Increase susceptibility | 44 |

| Toxocara canis | Perinatal | 250 μg/kg/day | Increase susceptibility | 72 |

In the context of bacterial infections, BPA exposure, affected the defense against Escherichia coli (E. coli) in young mice (Table 1). BPA decreased the ability of immune cells to eliminate E. coli at 24 hrs post-infection. In addition, BPA induced neutrophil migration to the peritoneal cavity and reduced their phagocytic capacity against the bacteria Coupled with these effects, a reduction in macrophage and lymphocyte populations were also observed (65). Moreover, the analysis of bacteria number in the peritoneal cavity indicated that there was a greater number of Colony Forming Units (CFU) in animals exposed to BPA as compared with untreated group (65).

While not properly an infection, bacterial colonization of the gastrointestinal tract needs to keep a balance between symbiotic, commensal and pathogenic species and maintains a bidirectional relationship with the immune system. In recent years, the microbiome has gained attention, since it has been demonstrated that it can affect not only the intestinal health, but also the metabolism and even neurological phenomena. In that regard, BPA exposure has also been shown to alter the gut microbiome. Lai et al. (2016), found a significant reduction in gut microbiota diversity in mice exposed to BPA through out the diet. Interestingly, this effect is similar to that induced by high fat and high sucrose diets. Furthermore, this altered microbiota was enriched in proteobacteria, which it is a known as a marker of dysbiosis (66). Moreover, another group reported that the BPA effect on microbiome reaches the second generation of bacteria, and that some bacteria -associated disease such as Bacteroides, Mollicutes, Prevotellaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, Akkermansia, Methanobrevibacter and Sutterella increase in proportion in BPA trteated animals (67).

The BPA effect upon immune response against Leishmania major (L. major) infection has been reported. In this context, the prenatal (administration of BPAin the drinking water, two weeks before mating and one-week post-mating,or in the adult lifeone week before to infection with L. major) induced an increase in the inflammation in the food pad of mice in a dose-dependent manner inr L. major infected mice (Table 1). The Treg cells number was also reduced at splenic level in both, mice exposed to BPA at prenatally or in the adult stage. Of note, animals exposed to BPA in the adult stage have an IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 increased level expression after L. major infection. Similar effect was reported in animals exposed to BPA prenataly where an IL-4 and IFN-γ increase was found (68). BPA effect in Trichinella spiralis (T. spiralis) infection has also been reported. The model was performed in mice exposed to a single dose (228 µg per mice) of this compound after 22 hours of T. spiralis infection, then mice were sacrificed at 42 days post infection and the muscle larvae number were counted. The study reported that BPA decreased the larvae number, suggesting that BPA has a protective effect against to this nematode infection (69). Recently, we have demonstrated that neonatal (3 days of age)) male and female syngeneic BALB/c mice exposed to a single dose of BPA, and that further were infected with the human nematode Trichinella spiralis in the adulthood, harbour fewer parasitic loads on the duodenum. Protective effect of BPA was related to an immunomodulatory effect of BPA related to the specific immune response to the helminth (70). Similarly, Nava-Castro et al (2020) demonstrated that neonatal treatment with a single dose of BPA, decreases parasites loads in the adulthood in BalB/c female mice intraperitoneally infected with the helminth parasite Tania crassiceps. Also, in this case, BPA had an specific immunomodulatory effect on the immune response (71). On the contrary, Ménard et al. (2014), using a perinatal administration model (day 15 of pregnancy until day 21 postnatal) of BPA in rats, administered in their drinking water and infecting afterwards with the parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (N. brasiliensis), reported an increase in susceptibility to infection in young female offspring (25 days of age) that were exposed to BPA perinatally (44). Similarly, Del Río et al. (2020), report an increase in susceptibility to Toxocara canis (T. canis) infection in adult male rats exposed perinatally (day 5 of gestation at 21 days postnatal) at a dose of 250 μg / Kg / day of BPA. The increase in larvae number was related to an inadequate polarization of the immune response, where there was an increase in Th1 cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ, while there was a decrease in Th2 cytokines IL-4 and Il-5, as well as specific anti-T. canis IgG antibodies (72).

As for the direct effects exerted by BPA on parasites, Tan et al. (2015), reported that this estrogenic compound increased mortalityof Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), also BPA accelerated its aging process by increasing mitochondrial and cytosolic oxidative stress, as well as ROS generation (73). Other report indicated that BPA exposure at concentrations of 1 to 10 μM on C. elegans embryos decreased the parasites´ oviposition during adult life (74). On the other hand, Zhou et al. (2016), in a multigenerational study using C. elegans as a model, reported that BPA induced physiological changes over the four generations of parasites, depending on the EDC concentration exposure (0.001-10 µM). In the first generation, parasites had a lower growth, moved slowly and produced lower offspring than nematodes that were not exposed to BPA (75). This work also referred that long-term BPA exposure (10 days), generated chronic toxicity affecting physiological indicators as body size, head contractions, body curvature and half-life; coupled with a greater stress response and a decrease in the population size (76).

Endocrine disrupting compounds modulate endogenous steroid responses and cell functions. Although most studies focus on their reproductive effects, their potential effects on immune cells and even more, on the immune response towards pathogens, should draw attention, given the expression of hormonal receptors by immune cells. Despite the fact that a lot of studies have evaluated the BPA effect with different variables such as BPA concentration, type of model, administered BPA dose, life stage or antigenic challenge used, one common element remains: BPA can differentially modulate the immune response. Sometimes, BPA treatment helps the host to defend it self against a pathogen, sometimes BPA treatment it is detrimental and helps the invader. Thus, BPA not always has to be considered an enemy, but a double edge sword, that depending on the context of the However, more studies are needed with the aim to elucidate the possible mechanisms by which this takes place.

Financial support: Grant IN-209719 from Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT), Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) and Grant FC2016-2125 from Fronteras en la Ciencia, Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT), both to Jorge Morales-Montor. Grant IA 206220 to Víctor H del Río Araiza, from PAPIIT, DGAPA, UNAM. Grant IA 202919 to Karen Elizabeth Nava-Castro, also from PAPIIT, DGAPA, UNAM. Carmen T. Gómez de León is a recipient of a Post-Doctoral fellowship from Grant FC2016-2125, Fronteras en la Ciencia, Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT).