1 Norwegian College of Fishery Science, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, 9019 Tromsø, Norway

2 Faculty of Technology, University of Applied Sciences Emden/Leer, 26723 Emden, Germany

Abstract

The marine ecosystem faces constant threats from climate change, overexploitation, pollution, and other stresses. Global harvesting knowledge, which can enhance production and environmental stewardship, is abundant in the expanding aquaculture industry. Some technological tools fail to consider the complex and dynamic factors that influence decisions in the maritime realm, thereby overlooking local ecological knowledge. This study offers a novel perspective by focusing on human cognition. Complex challenges require wise decisions amid uncertainty about the future. However, people often dismiss intuition as an appropriate basis for decision-making. Intuition provides access to important tacit knowledge that enables investigation and implementation of more resilient decisions. The article urges fish farmers and researchers to pay greater attention to intuition because it is an immediate and significant component of decision-making. It further explores how emerging technologies, such as AI, could support intuition, addressing potential benefits, challenges, and strategies for integrating intuition into mainstream aquaculture practices. This article is the first to synthesize different cognitive perspectives on decision-making within aquaculture. Further empirical studies of these interactions will open promising pathways for future interdisciplinary research.

Keywords

- fish farmer decision-making

- aquaculture management

- marine resources

- tacit knowledge

- holistic decisions

- intuition

Aquaculture is the world’s fastest-growing food industry (Joffre et al, 2017). As the sector has grown, so too have the methods used to lessen social and environmental consequences of aquaculture (Mizuta et al, 2023). Fish farmers are under growing scrutiny to make management choices that conform to the triple bottom line, making them profitable, sustainable, or even ecologically wise. In this novel approach, we combine knowledge from cognitive psychology of decision-making and virtue ethics with the practice field of aquaculture. This study inquires: How can the cognitive processes of both intuition and deliberation be leveraged more effectively, contributing to wiser decisions in aquaculture?

Decision-making in the face of uncertainty involves the identification of plausible, alternative socioecological futures in the medium to long term (Kelly et al, 2022). Humans’ capacity for deliberation aids in exploring and weighing possible choices. Alternatively, the use of intuition can provide a more immediate response to decision problems. Occasionally, more analytical rational processes of deliberation can be barred through intuitive responses (Evans, 2011; Pennycook et al, 2015; Svenson et al, 2023b). It is uncertain whether intuition, deliberation, or a combination dominate practitioners’ everyday practice. Humans’ psychological make-up is one of the factors that determines individuals’ capacity to anticipate what will happen in the ocean of the future (Kelly et al, 2022), as well as in their day-to-day operations. To work towards wise socioecological decisions, humans need to avoid pitfalls that stem from an overreliance on either deliberation or intuition. Over the past decades a development from local ecological knowledge (LEK) to globalised harvesting knowledge (GHK) occurred, as harvesters become less reliant on the socioecological linkages that have historically sustained traditional species and stocks (Murray et al, 2006). The increasing advances in technology prompted some to diagnose a cyborgization of fisherman’s craft (Johnsen et al, 2009a; Johnsen et al, 2009b). We need to learn if and how (future) technological instruments, such as artificial intelligence (AI), can aid either inferential or holistic intuition for sustainable aquaculture of future oceans. Prior works looking into fisheries management suggested that cognitive biases limit the implementation of new socio-ecological knowledge and that behavioural science knowledge can aid in more nuanced approaches to bring about wise decisions (Fulton, 2021). Because all information is filtered by preferences for certain information, these biases have an impact on aquaculture decision-making. Biases can impede the adoption of new information or oppose change, especially when it contradicts one’s preexisting beliefs (Kahneman, 2011).

There is a diversity of aquaculture practices around the globe, such as freshwater versus marine, nearshore versus offshore, small-scale versus large-scale, and fed versus extractive aquaculture (Costa-Pierce et al, 2022). Aquaculture in traditional societies has a history stretching back more than a thousand years (Beveridge and Little, 2002), while industrialised salmon farming in the global north is more recent.

Aquaculture managers primarily rely on (local) experience-based knowledge, while a range of technological systems, also known as globalised harvesting knowledge, supplement human cognition. Whether one considers those who feed the fish (today, operating feeding robots) to be fish farmers, or those who tend to the day-to-day technical operations, the fish health scientist, or the biomass controller, it is difficult to pin down who exactly is a fish farmer in this context. Therefore, we can conceptualise fish farming as a multi-actor field of practice. These technological systems can support decisions across the entire value chain, with “intuition” remaining an important factor. Tacit knowledge often underlies intuitive decisions and gut feeling, and both are based on practical experience and literal/theoretical embodied knowledge (Brockmann and Anthony, 1998; Curry and Kirwan, 2014; Hadjimichael et al, 2024). Our article’s contributions are a clear identification of the gap in both fish farmers and researchers’ knowledge about intuition and its significance during decision-making. Future empirical studies of technology tools, such as AI and its interactions with management decision-making in aquaculture, provide a salient pathway for transformations towards sustainability.

Rational planning tools cannot account for what cannot be known (Dörfler and Bas, 2020). Some indigenous communities devote significant time and effort to contemplating and organising for the future (Foley et al, 2020), hardly using Western science-based knowledge. Conversely, in numerous coastal communities in Norway, aquaculture managers argue that government bodies have assumed responsibility for future organising (Sandersen et al, 2020), resulting in an undervaluation of the individual-level thought processes and ideals involved in management decisions (Fulton, 2021). Authors like Jentoft (2006) suggest that social science can add more of a reflexive, deliberative, and wise value-rational conduct to aquaculture and fisheries. However, there appears to be a lack of studies that leverage the intuition of fish farmers for wise socioecological futures. Against the multiple challenges facing the industry, ignoring the LEK, e.g., intuition based on experience, and the results of behavioural research, e.g., allowing cognitive biases, would be fatal. Fish biomass estimates are often based on below 2% of the fish population in recirculating aquaculture systems (Yogev et al, 2020). This may lead to greater biases than indicated by the confidence interval, which, if prevalent, will likely cause overfeeding or underfeeding, both of which carry adverse economic and environmental repercussions (Yogev et al, 2020). But to only rely on GHK, e.g., operating only on deliberately rational approaches, would also limit the solution space unnecessarily.

How, then, do fish farmers use intuition to make management decisions, especially ones that consider ecological and social impacts far into the future? To our knowledge, there have been no reviews on the use of intuition in aquaculture management. In a different natural resource-based industry, von Diest et al (2020) provide an indicative overview on the use of intuition for agricultural application, involving several themes. Authors like von Diest et al (2020) suggest that Western science (much like GHK) can learn a lot about the use of intuition from indigenous and traditional LEK, also understood as tacit knowledge. In their review, von Diest et al (2020) stress the need to think again about using analysis to help farmers make decisions, as well as the role of human growth and nature connection in developing intuition. We are building on and extending these issues for the maritime realm, focusing on the expanding aquaculture industry in the global North. Bush and Marschke (2014) proposed integrating findings and approaches from agricultural changes to understand the effects of social-ecological transitions in the aquaculture industry. However, their focus was on the system level, whereas our contribution concentrates on the individual’s cognitive processes. In this article, we suggest that future theorization to advance social-ecological transitions in coastal areas (Stone-Jovicich et al, 2018) should integrate the intuition concept into aquaculture decision-making. Every day, any thinking human being makes use of the cognitive processes we discuss in this position paper. Our contribution highlights both the value-added and the pitfalls that stem from humans’ cognitive limitations, using aquaculture as a practice field. As a result, we account for both potential fallacies and the flourishing of human capacities in aquaculture management, an approach that is unprecedented in this practice field.

Fish farmers’ hands-on experience with marine ecosystems provides a source of applied ecological knowledge. This knowledge base complements knowledge gained through scientific inquiry and leads to context-specific understanding using local resources rather than universally applicable solutions (Osmundsen et al, 2017; Wiber et al, 2012). The combination of these two types of knowledge fosters the interplay between rational scientific and intuitive knowledge (Dreyfus and Dreyfus, 2005) and may be the answer to the multiple challenges facing marine businesses today. Our article’s contributions provide an improved understanding of the cognitive processes behind the interconnected nature of intuition and deliberation in marine businesses, as technology and GHK become increasingly deeply enmeshed with ecological subsystems. Along with GHK, the use of AI tools has become more prevalent, and we discuss potential interactions with intuition.

The United Nations’ Ocean Decade Objectives project a myriad of meanings onto the marine environment, of which we only select a few: When society recognizes and appreciates the ocean’s importance to human well-being and sustainable development, it becomes a source of inspiration and engagement. There is also talk of a food-secure and environmentally-sound ocean economy that relies on a productive marine environment and a foreseen sea where people are aware of and prepared for oceanic shifts (Davies and Vauzelle, 2023).

Against these abundant aspirations, it is important to investigate the transition processes from LEK to GHK, now increasingly supplemented through the application of AI in the name of sustainable aquaculture. On-farm experimentation and learning have always been essential for enhancing productivity and have generated knowledge that is frequently characterised as tacit and local, due primarily to the uncertainty and context specificity of the knowledge (Tveteras, 2002). Tacit knowledge involves perspective, personal ideas, values, and intrinsic knowing and can be both consciously and unconsciously known. We can trace it back to learned behaviours such as adhering to established norms and etiquette. Such synthetic knowledge dominates the aquaculture industry, emphasizing learning through hands-on experience and interaction, unlike other industries primarily dominated by analytical forms of knowledge (Aslesen and Isaksen, 2007). Learning in biotechnology and information technology businesses relies more on knowledge infrastructure and new scientific or technologically codified information (Asheim and Coenen, 2005).

Aslesen and Isaksen (2007) further suggest that aquaculture businesses typically base their activities, as well as their development and gradual advancement, almost exclusively on practical skills. The knowledge base underlying innovation activities is largely tacit, as most of the learning occurs through doing and interaction among peers. In general, these businesses invest little in research and development but place a strong emphasis on resolving specific operational problems (Aslesen and Isaksen, 2007). Iversen and Hydle (2023) suggest that this has changed over the past few decades. Reviews of innovation in the aquaculture sector suggest that there is as yet limited integration of systemic approaches to further understand the multi-dimensional and multi-level interplays in complex aquaculture systems (Joffre et al, 2017). Accordingly, we can state that a specific type of intuition is of enormous importance in companies in the aquaculture sector because knowledge based on practical skills is paramount. Okoli and Watt (2018) suggest that people learn constantly without understanding when, how, or where, but apply their knowledge to address future issues in creative ways. Pretz et al (2014, p. 454) further state that holistic intuitions “integrate diverse sources of information in a Gestalt-like, non-analytical manner; inferential intuitions are based on previously analytical processes that have become automatic; and affective intuitions are based on feelings”. This fits well with the idea that intuition isn’t always clear, measurable, or transferable in the field of knowledge management (Oğuz and Elif Şengün, 2011), especially when it comes to the mental rules that people use to make decisions. However, intuition and tacit knowledge formation hardly feature in the marine research literature; for example, a review of the aquaculture innovation literature does not treat these issues (Joffre et al, 2017).

Betsch (2008, p. 4) describes the relationship between learned knowledge and intuitive decisions thus:

The input to this process is mostly provided by knowledge stored in long-term memory that has been primarily acquired via associative learning. The input is processed automatically and without conscious awareness. The output of the process is a feeling that can serve as a basis for judgments and decisions (p. 4).

In the words of Simon (1987), pattern identification that builds on prior experience is the most important step in intuitive decision-making because it provides professionals with ready access to their tacit knowledge base. Lindblom (1959) also coined the term ‘muddling through’ to describe this approach to decision-making. It stands to reason that the ability to control one’s intuition is foundational to making better choices. In general, many academics have supported intuition from a dual-process theory perspective. Judgments, decisions, and problem solving are said to include two distinct “dual” types of cognitive processes: an intuitive fast thinking mode and a deliberate slower thinking mode associated with rational analysis (see, e.g., Epstein (1994); Evans et al (2015)). Both intuition and deliberation processes are used, although people typically show a preference for one over the other (Betsch, 2004). There has also been extensive discussion about a third unconscious thinking mode that can solve deliberation tasks while we are asleep (Dijksterhuis and Strick, 2016). For an overview of different kinds of intuition, see Svenson et al (2023b).

Recent research adds to the dual process view by suggesting that using both processes equally may lead to wisdom, or making wise decisions, in the same way that virtue ethics does (Sadler-Smith, 2012). This line of research has been picked up to look into the problems that human organisation causes for the environment (Glynn et al, 2022; Jentoft, 2006; Sadler-Smith and Akstinaite, 2022). Our guiding theory is the dual process perspective of human cognition, and we suggest applying it to the socioecological challenges of aquaculture practice. Building on this discourse, a wise resource harvester would be an aquaculture practitioner who employs both cognitive processes, intuition, and deliberation, along with a blend of LEK and GHK, to restore the socioecological relationships traditionally associated with species and stocks. Only the combination of both thinking processes—intuition and deliberation—seems to promise wise decisions.

This literature overview evaluates the current state of knowledge, identifying gaps in research and highlighting future research avenues (Snyder, 2019). Using the search terms outlined below, we searched the scholarly database Web of Science to assess the extent of prior research on the role of intuition in aquaculture decision-making. The process for analysing and synthesizing the findings was guided by the pertinent conceptual framework of intuition research (see above). Paul and colleagues (2021) suggest that a field may be relatively new or lack interest among researchers if there are fewer than 40 articles for review; in this case, they recommend that researchers consider writing a position paper to encourage further study in the field (MacInnis, 2011). We argue that our field for review is relatively new and follow the recommendation to write a position paper. We integrate different fields of knowledge, working towards wise socio-ecological decision-making.

The following search words were used:

fish farming AND intuition AND aquaculture: 1 result;

fish farming AND tacit knowledge AND aquaculture: no results;

tacit knowledge AND aquaculture: 3 results;

intuition AND aquaculture: 5 results, including one double;

intuition AND fishermen: 2 results;

intuition AND marine resource management: 1 result.

After having found very few results (and before screening them for relevance), we carried out an additional Google Scholar search to corroborate these findings to check for content not available in controlled databases (Halevi et al, 2017). There are some limitations to this approach, including the possibility of incorporating less rigorous or peer-reviewed sources into the results. This approach has some limitations, such as the potential for less rigorous or peer-reviewed sources to be included in the results. However, we applied this search to make sure we are not missing innovative works. Regarding the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we often excluded works in which authors claimed that certain results were intuitively plausible, as this interpretation of intuition does not align with the framework adopted in this study. Consequently, such results were not referenced and were excluded from consideration. The explicit inclusion criteria (Snyder, 2019) included any approach that utilised a behavioural science approach to decision-making, any approach that explored the use of artificial intelligence to support decision-making in aquaculture, or articles that employed intuition or deliberation as a metaphor for decision-making. We did not limit the search too greatly (Snyder, 2019), so that we provide a useful overview of the literature.

From 43 results, we filtered the following 10 additional results after removing duplicates. The literature search sought to answer the question: How is intuition currently understood in the aquaculture literature? Our first objective is to describe how dual-process theory approaches to decision-making relate to the specific context of aquaculture management, which we lay out in the section “Intuitive awareness and local ecological knowledge”. The subsequent three sections provide a synthesis of deliberation, intuition, and artificial intelligence methods that assist fish farmers in decision-making.

We conceptually structure our review article (Torraco, 2005) using dual process theory approaches to wisdom in decision-making, which is our guiding theory. We combine this research with the analytical frameworks found in marine social science and agriculture (harvesting natural resources) to help us understand intuition better when it comes to aquaculture decision-making. According to our literature search, the following section illustrates the current state of intuitive awareness and ecological knowledge.

As an example for LEK, Garavito-Bermúdez and Boonstra (2023) suggest that: When fishing, you’re pretty much always on your own in terms of making judgments (paraphrased by a respondent fisherman) (Garavito-Bermúdez and Boonstra, 2023). Engaging in conversations with indigenous and traditional ecological understandings is vital for managing food production landscapes (Silvano et al, 2023), and many traditional and indigenous societies around the world have established a highly integrated, holistic, intuitive awareness of the complex environmental systems in which they live (Santiago-Vera et al, 2021). The use of indigenous and traditional ecological understanding (Foley et al, 2020) has been acknowledged, but not infrequently pegged in competition with Western science-based knowledge (Piczak et al, 2022), also known as GHK (Murray et al, 2006). These different types of knowledge interact in the decision-making process. When a practitioner with extensive LEK applies GHK in a solution space, it could potentially result in a “knowledge action gap” because it doesn’t make intuitive sense to him or her. Therefore, people might refrain from acting based on their human intuition.

We agree with von Diest et al (2020) that tapping into intuition and, by extension, tacit forms of knowledge may lead to better decision-making in natural resource-based industries. Knowledge management in modern aquaculture also acknowledges the potential of tacit knowledge but notes that it appears out of touch with the advancement of technology (Mustafa et al, 2015), so that these different types of knowledge are potentially conflicting in the decision-making process. However, in recent years, tacit knowledge has gained attention as an important factor in running aquaculture operations (Pache et al, 2022). Fish farmers in natural resource-based societies use tacit knowledge to enhance the resilience of their aquatic ecosystems against changing climatic conditions (Galappaththi et al, 2019; Lebel, 2013; Schlingmann et al, 2021). Decision-makers in fishery contexts, particularly those in areas with rapidly-changing climatic circumstances, must take into account resilience (the ability to remain functional under stress) as a key criterion of health and adaptability in aquatic systems (Bricknell et al, 2021; Galappaththi et al, 2019). The intertwining of resilience and aquatic system health makes it significant for decision-makers to rely on their intuition to strengthen resilience (Lakra and Krishnani, 2022). Apart from acquiring intuitive expertise through extended training (Dreyfus and Dreyfus, 2005), one can also acquire it from one’s immediate work environment, which includes elements such as language, culture, and tradition (Hogarth, 2010), and through ample socialising and risky discovery training (Scheffer et al, 2015). To this point, the discussion on the aquaculture industry suggests that tacit learning’s development and outcome contribute to a more holistic, pragmatic knowledge base. Aquaculture methods have also been enhanced and developed by externalising the tacit knowledge embedded in traditional and indigenous ecological knowledge systems (Devi et al, 2014).

Eight articles from our initial search directly addressed the development and application of analytical decision support systems in advanced economies. O’Donncha and Grant (2019) show how Internet of Things (IoT) technology is enabling precision aquaculture, optimising fish health, growth, and economic returns while reducing risks to the environment. Until now, farmers have made decisions based on their observation, interpretation, experience, and intuition. However, the development of real-time sensor technologies provides the opportunity to allow real-time decisions based on artificial intelligence insights and IoT connectivity, replacing ad-hoc decisions based on heuristics and intuition.

Ballester-Moltó et al (2016) confirm that fish farmers have a gut feeling about food residue production parameters in comparison to the available food in open water.

When designing data science applications for aquaculture, Costa and Rihtar (2016) refer to intuition as a relevant criterion, which requires coordination with the expertise of fish farmers, their procedures, and the current technologies used. For example, it is about considering multiple interpolations to account for the values that differentiate fish farms and play an important role in their decision-making in fish production.

Saad et al (2022) suggest that an increasingly important issue for many sectors is making data understandable to workers with varied levels of training and expertise as digitalization spreads across the value chain. The graph database approach facilitates data comprehension and may serve as a foundation for the development of more user-friendly and effective aquaculture ecosystem application technologies (Saad et al, 2022). In the area of visualisation techniques, Zheng et al (2023) take the discussion about intuition in another direction, integrating patterns of fish schools moving around inside the production facility into an intuitive pattern for the fish farmer to observe. Tschirren et al (2021) present software that facilitates the standardised, straightforward collection of important, achievable, and trustworthy parameters from which the model derives intuitive fish welfare ratings in aquaculture. According to Wada and Hatanaka (2011), previous technology did not allow for a reliable determination of the temperature distribution below the water surface before fishermen combined their experience and intuition to form their actions regarding water temperature.

The literature on artificial intelligence applications to aquaculture either posits intuition as the opposite of rational models or only features intuition as a characteristic of, for example, user interface design (Gladju et al, 2022; Zhou et al, 2018). The dynamic nature, institutional complexity, and uncertainty in the field of aquaculture led Osmundsen et al (2017) to derive an overall approach to the administration and management of aquaculture based on a case from Norway. The elements of this good governance approach for the aquaculture sector seek to build competencies, emphasise the importance of collaboration and adaptability, and finally aim for flexibility and cost-effectiveness. The approach acknowledges that fish farmers see their experience and intuition as important tools in managing their fish farm.

Meijboom and Bovenkerk (2013) work in another direction, looking at how likely the use of intuition in moral decision-making around fish welfare is. The article by Pigeon and Létourneau (2014), using the example of the public debate in relation to the development of the aquaculture industry in Canada, points out that both ecocentrism and biocentrism are important “as paradigms of environmental ethics”. Using the term “ecocentric intuition”, they refer to people’s moral intuition regarding environmental problems that affect ecosystem functions such as biodiversity, ecosystem health, and other holistic phenomena. Because ecocentrism implies a real paradigm shift, biocentrism remains an important practical method for asserting ethical positions regarding environmental concerns in public debates. Against this backdrop, “biocentric solutions” offer a good opportunity to connect society with the environment, change it, and participate in its unfolding.

In the article “The Old Fisherman’s Mistake”, Rovelli (2022) tells the story of an old fisherman who loved the sunset. The sunset had a profound impact on his life until he learned a more accurate narrative: the sun never truly dips into the ocean, but it consistently shines. The sunset is a collection of the consequences of Earth’s rotation, which takes us out of the illuminated part of the globe. But sunsets are not “illusory”. They exist even after an accurate explanation, and they play exactly the role that sunsets have always played. What is illusory is that a sunset is literally the sun dipping into the waves. This new knowledge must not cause the old fisherman to lose his mind, but rather to acknowledge and deal with the inadequacy of some of our old concepts and the intuitions that underlie them.

Furthermore, when it comes to the success of aquaculture operations, knowledge of the physiology, ecology, and behaviour of the cultured aquatic species has traditionally taken a back seat to the intuition of the farm manager (Lee, 2000). However, in roadmaps about the future of sustainable aquaculture, intuition for improved decision-making does not feature (Osmundsen et al, 2020). Yet, future behaviour predictions are essential for planning and management purposes, requiring not only information, system understanding, and experience but also intuition (Boschetti et al, 2020). Shainee et al (2013) adopt an academic design approach, leading one to anticipate their consideration of farmers’ intuitive knowledge; however, they only take into account the creative intuition of the designer. Although many academic sources referenced above acknowledge the importance of intuition for aquaculture practitioners, a conceptual base is lacking. We fill this conceptual gap in research by combining knowledge from various academic disciplines in a novel way.

The benefits of using different types of intuition in management are gaining more attention (for an overview, see, Svenson et al, 2023b). The industry, to some extent, accepts the benefits of intuition in aquaculture, but research has not fully embraced them. This article provides a clear message for researchers: they should focus more on the high level of intuitive processing that current industry practitioners exhibit. Berkes (2012) discovered that successful Inuit fishers and hunters heavily relied on their developed intuitive capacity when making decisions in ecosystem-based fisheries. Berkes (2012) suggests that intuition has advantages, since there comes a point beyond which accuracy and importance (or relevance) become practically mutually exclusive features (Zadeh, 1973, p. 28) due to the increasing complexity of the system to be handled. This argument resonates with work in management studies around simple heuristics that help people to make smart decisions (Gigerenzer, 2021). Some recent work in the field of fisheries addresses human cognitive biases that can result from an overreliance on intuition (Fulton, 2021). To our knowledge, there currently is no aquaculture model to explain intuition by considering the impact of a wide range of influencing variables, such as experience, feedback, repetition, training, mentoring, reflection, self-critique, intelligence, personality, goals, risk attitude, observation, and anticipation skills, like there is for agriculture (Nuthall and Old, 2018). Recent work shows that farmers have a high propensity to use intuition (Svenson et al, 2024). An analogy to research on agriculture entrepreneurs suggests that self-employed decision-makers, such as entrepreneurs, tend to rely on hunches due to a natural trust in instinct and inspiration, which lessens their reliance on deliberation (Koudstaal et al, 2019). In studies on computers in the workplace a connection has been found between the propensity to use intuition and higher confidence towards technology usage (Svenson et al, 2020; Svenson et al, 2023a). Because of their experience and ability to predict future events, entrepreneurs’ confidence in their gut grows (Nuthall and Old, 2018).

Fish farmers frequently stress the importance of intuition in maintaining farm health (Darapaneni et al, 2022), making a case for local ecological knowledge. Bremer et al (2017) and Ritzema (2013) both portray fishermen as actors, utilising tacit knowledge, but they do not specifically address the use of intuition. The article by Drew et al (2021) treats tacit knowledge of fishermen to some extent but relates it mainly to their mental models but not their decision-making. The current state of the art in the fish farming industry relies on human intervention and observation, as well as interpretation and making decisions based on experience (Føre et al, 2018; Osmundsen et al, 2017), but research that explicitly accounts for intuition is lacking. To assist operator decisions, algorithms can be implemented to extract pertinent information from datasets (e.g., fish movement inside the cages) that depict various scenarios, hence simplifying the operator’s decision-making process by guiding them toward the most advantageous options (Biazi and Marques, 2023). Future research should investigate which insights and intuitions AI systems in aquaculture can evoke in individual users, to determine its actual effect on decision-making.

Organic production in aquaculture is a growing and not yet mature field with few works (Lagutkina et al, 2022). For a recent overview, see Mizuta et al (2023), which includes an overview of organic aquaculture, also known as regenerative aquaculture. However, while biodynamic certification for farms only regulates physical practice requirements (von Diest, 2019), the theory behind biodynamics, drawing on an analogy to agricultural research, provides systematic guidelines for self-observation and the development of intuition (von Diest et al, 2020). Biodynamic aquaculture businesses might be the first to consciously attend to the further conscious development of intuition. Hogarth et al (2015) suggest that there are kind and wicked learning environments for training intuition. A “kind” learning environment is one where practitioners gain immediate feedback for decisions, as is the case in aquaculture. For example, suboptimal growth of fish or death. Here there is a clear link to the literature on organisational learning that regards intuitions as the cornerstone of new knowledge generation in corporations (Woolhouse and Bayne, 2000). Kind learning environments support the development of intuition. Across Europe the development path for aquaculture operations displays large differences, while there has been growth in Norway and Denmark, aquaculture production stagnates in Germany (Lasner and Gimpel, 2024). Apart from institutional differences, future research should try to determine if the propensity to use intuition vis-a-vis analytics in aquaculture decision-making differs across country contexts.

All key decisions in modern fish aquaculture are made by humans, who employ their knowledge and interpretation of the data they collect from observing the fish and other activities within the cages, as well as protocols, legislation, and suggestions for farm management (Føre et al, 2018). Making the “right” decision is a complex task that is difficult to assign to computer-based systems without running the risk of unforeseen and potentially undesirable side effects (for example, suboptimal feeding due to limited data on fish responses), so this is likely to remain the case for fish farming operations for the foreseeable future (Føre et al, 2018). This is an example, in which AI can support human intuition through providing estimations of biomass or the visualisation of fish movements. Based on this AI input humans can use their intuition for decision-making. So far, there is no suitable literature on fish farmers’ gut feelings that help to determine the optimal feeding interval.

Fish live in complex relationships with other organisms in the marine ecosystem. If we catch large quantities of fish, we change the entire living environment and influence the network of relationships. The situation becomes complex due to the inherent time-based dynamic of the system, which is characterised by constant changes in the structure or arrangement of its elements and their relationships (Gelpke, 2013). To sustain fish stocks in the long term and manage fisheries accordingly, it is therefore necessary to consider the complexity of the marine system. The complexity arises due to intricate biological mechanisms and processes, as well as fluid dynamics and various chemical agent uses, so that using autonomous AI systems to make decisions would seem too far-fetched at this stage of technological advancement.

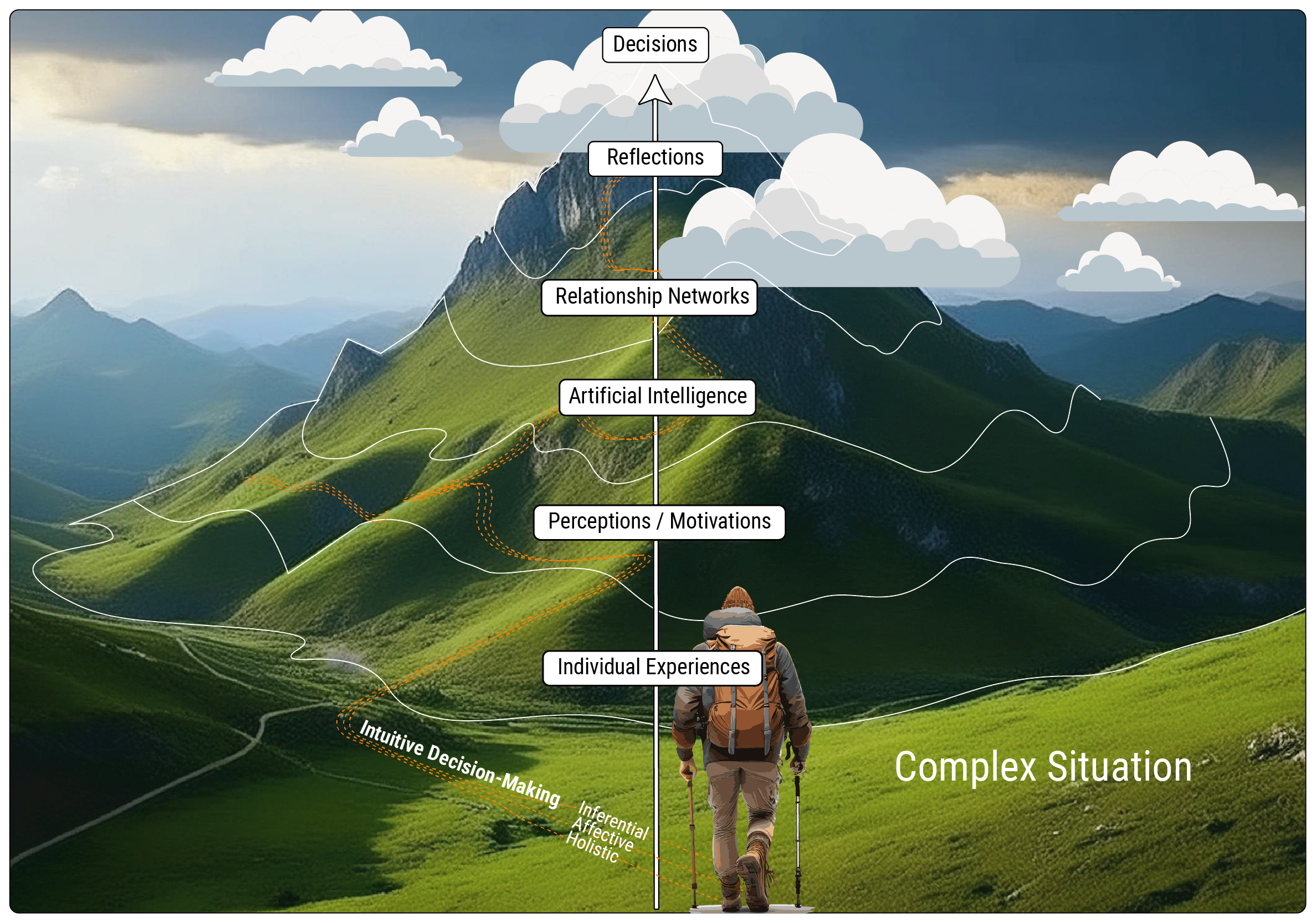

Because people’s local use and values create social complexity, it’s important to come up with hybrid decision support solutions that combine human and artificial processing when making moral, legal, and cultural decisions. For example, when dealing with global climate change and more local and regional environmental issues. Fig. 1 conceptualises the process of intuitive decision-making in complex solution spaces as a journey into an uncertain future. The overview of the interrelationships of the decision elements has been lost, just like in the marine system. This journey requires preparation and many iterative steps to approach the “final” decision. In the example of a complex solution space, ambiguities initially confront the traveller with a complex situation, leading to different perceptions and interpretations (Okoli and Watt, 2018; Scherm et al, 2016). The traveller is unable to make a decision in this solution space immediately due to his lack of knowledge on how to solve the problem within it. Therefore, his actions and their outcomes are unpredictable, necessitating the development of the solution first. Reasonable decisions combine the functional and temporal relationships in the marine ecosystem with the perspectives of the people involved. A solution space is complex primarily because decision-making is not predictable. For Bennet and Bennet (2008), such situations are “most likely unique and unprecedented, difficult to define or bound, and have no clear set of alternatives” (p. 5). Pretz (2011) distinguishes between three types of intuition when making decisions. Holistic intuition is based on the rapid and unconscious integration of various types of information perceived in the environment. In high-complexity solution spaces, holistic processing outperforms analytical processing and is also accessible to non-experts. Affective intuitions stand for decisions that are primarily based on emotions, e.g., when we can decide with certainty or confidence. Finally, inferential intuition is characterised by the judgement of experts. Experts can detect patterns in complex situations and recall patterns stored in memory. Chess experts, for example, have a powerful repertoire of patterns that they have acquired over several years of serious play. This enables them to recognize advantageous moves without having to calculate all possible eventualities (Chase and Simon, 1973). Simon (1987) defined intuition as the recognition of patterns stored in memory, to which Kahneman and Klein (2009) also refer. Simon views intuition as solely reproductive, as it repeats successful patterns instinctively. However, intuitive decisions also have productive aspects when proven patterns are usefully combined and applied appropriately to the context, for example in negotiations (Okoli and Watt, 2018; Scherm et al, 2016). Intuitive decisions therefore move between (reproductive) routine and (productive) improvisation. The input for the journey on which we intuitively decide in a thinking process is experiential knowledge that we have acquired through associative learning, and that is visualised in the figure with a backpack. The output is ultimately the emotion, in the figure the cloud-covered peak, based on which a decision is made. To be able to decide intuitively, we therefore need the ability to learn and evaluate (Balasubramanian et al, 2022). When learning and making decisions, how we process information initially depends on our values, which have something to do with our individual experiences. Furthermore, information processing changes with the context. We gain new perspectives, are remotivated, or perceive new clues. Intuitive decisions become more reliable when the environment provides valid clues and the people making the decisions can learn from the clues. On the way to the summit, we can accumulate knowledge when we collaborate with artificial intelligence or interact in a network of personal relationships. Finally, we can consider the consequences of our decision and improve our decision because we reflect on past actions.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Decision-making in the complex solution space. (author: M. Blattmeier; visualization: E. Wolters-Schaer).

In the digital age, intuitive decisions in complex situations can also be made in collaboration with artificial intelligence. We can understand artificial intelligence as a technological principle that aims to mimic human intelligence across various applications. Data, processing power, and algorithms are the three basic components that computer scientists use to develop systems with artificial intelligence (Leonardi and Neeley, 2022). Because algorithms recognize patterns in large data sets, they enable machine learning. While supervised learning trains machines with known patterns and a specific target, unsupervised learning allows the machine to recognize patterns independently. This enables users to uncover correlations that would not previously have been possible (Moring, 2023a). In reinforced learning, the algorithm does not receive a description of patterns but rather learns from positive or negative feedback that we humans provide. In deep learning, humans do not need to intervene in the learning process because the machine collects information with a neural network, develops concepts with a hierarchical character from this, and links these with new information again and again. In this way, the machine can evaluate, make predictions or recommendations (Balasubramanian et al, 2022; Eriksson et al, 2020), and ultimately take on tasks that are basically a collection of decisions.

If systems with artificial intelligence work by recognizing patterns just like human intuition, then systems with artificial intelligence should also be able to make intuitive decisions. Simon (1997, p. 167) asserts that intuition is no longer exclusive to humans, stating, “When we see someone coming down the street, we may not know who it is at first, but if it’s a friend, we are likely to know it long before we know how we knew it”. If that’s the definition of intuition, then we can also assert that computers possess it. However, the processes of artificial intelligence and human intuition differ: Firstly, systems with artificial intelligence are oriented towards a mathematical optimum. Human intuition, however, looks for sustainable solutions—not necessarily mathematically perfect solutions—to a problem in a specific context and based on individual experience. Secondly, artificial intelligence systems perform better the more information they have access to, but this improvement is limited to a specific task. We humans, on the other hand, feel overwhelmed by an increasing flood of information but can deal with many different tasks (Moring, 2023a). AI can surely also be used to solve multiple tasks, however this might not be desirable due to statistical biases (Biazi and Marques, 2023). When an AI is applied to a task, human intelligence evolves on its own because people have different perspectives on the activity. This is why, particularly in complex settings, humans should retain decision making authority since they can think in bigger contexts, “loops, and cycles” (Moring, 2023a). Thirdly, our intuitive decisions allow us to be creative in a unique way. Human intuition, on the other hand, is not based on numerical calculations but rather on unconscious processes. Humans base their accumulated experience on emotions, searching for other perspectives in a new environment that they perceive in a multi-layered way. In summary, human intuition is particularly suitable for volatile environments (Moring, 2023a; Pretz, 2008). On the other hand, in stable environments, algorithms can maximize their potential because they are faster, more reliable, and produce more computationally optimal results. Even in complex situations, statistical analyses maintain consistency, remain unaffected by subjective impressions, and identify weak but valid indications (Kahneman and Klein, 2009).

“A calculation is not a decision”, emphasise Meckel and Steinacker (2024, p. 281) and point out that we not only have to decide on the environmental conditions for artificial intelligence outlined in the previous section but also on how we want to use artificial intelligence. Artificial intelligence can influence inferential intuition by providing data-driven insights, as suggested by the visualisation of fish school movements (Zheng et al, 2023). In this way, AI can play a role in supporting intuition. Such AI-powered predictive analytics tools can highlight upcoming risks or opportunities that a human might miss (Gandomi and Haider, 2015). Shrestha et al (2019) suggest that it can also be beneficial to combine inferential and holistic intuition using hybrid AI systems. These systems can leverage the strengths of both types of intuition to provide more accurate and comprehensive insights. Artificial intelligence can assist us in making decisions, take over, and ultimately replace us (Quaquebeke and Gerpott, 2023). Accidents in the testing of autonomous vehicles remind us that a decision always needs a decision-maker, either AI or human. There are three possibilities for this (Meckel and Steinacker, 2024): In the “human in the loop” model, humans make decisions with the assistance of AI. Humans can also limit themselves to monitoring artificial intelligence judgments and intervening, if necessary, as in the “human on the loop” model. After all, when machines navigate themselves in the “human out of the loop” model (with a range of ethical and social implications), humans become irrelevant. Regardless of whether it is artificial intelligence or humans making the decisions, it will presumably always be humans who must take legal responsibility. Because of the quality of the calculations, it can be difficult for humans to deviate from the results of artificial intelligence in their decisions. On the other hand, it is convenient to hand over responsibility to intelligent machines. Humans need to understand that developing feelings for “artificial intelligence”, for which there is currently no repertoire, can influence or disrupt their intuitive decision-making, resulting in a one-sided relationship with a computer (Weber-Guskar, 2024).

Designing future socioecological scenarios against present-day challenges has implicated the study of virtue (Jentoft, 2006). The distinction between System 1 (intuition and affect) and System 2 (analysis and reason) in the psychology of decision-making provides a model for uncovering people’s reasoning (Sadler-Smith, 2012, p. 373). Both reasoning systems are important to bring about wise decisions (Sadler-Smith, 2012). However, there are very few studies (Costa-Pierce, 2021; Groesbeck et al, 2014) that focus on the state of wise practice in the aquaculture business.

Recently, dual-process theories of cognition have linked the interaction between System 1 and System 2 (Sadler-Smith, 2012) to the need for us to adopt a more enlightened approach to dealing with the environment. The academic fields of management and organisation studies, as well as decision makers from different countries and continents, have come to realise the significance of the relationship between the two modes of thought for wise practice (Dewangan and Ghosh, 2022).

When practitioners define virtuous practice or practical wisdom, they often use the term “intuition”, a term that has been used by researchers recreating the cognitive mechanisms that generate such wisdom (Jeste et al, 2019). Any business sphere can benefit from exemplifying virtues. When catastrophe happens, like anthropogenic climate change, wide-spread pollution, or overfishing, the need for virtues becomes more apparent (Sadler-Smith and Akstinaite, 2022). There is a requirement for prudent judgment across all industries (McKenna et al, 2009). This suggests that the aquaculture discourse can gain from the expansion of wisdom research (Jentoft, 2006), which is flourishing in the field of business ethics (Bachmann et al, 2018; Rooney et al, 2021). Aristotle’s ethical theory exemplifies phronesis through excellence in both general practice (Jentoft, 2006; Kristjánsson, 2022) and ecological practice (Xiang, 2016). Consequently, the academic literature has advocated for eco-centric (Purser et al, 1995) and/or climate-resilient (Linnenluecke and Griffiths, 2015) organizations (Küpers, 2020). Several authors have started to discuss what organizing in the Anthropocene entails (Heikkurinen et al, 2016; Wright et al, 2018). To bring about wise practice in aquaculture businesses, dual process theory-inspired virtue ethics approaches suggest first and foremost focusing on individuals’ decision-making (Sadler-Smith, 2012) and then on collective decision-making (Kristjánsson, 2022; Sadler-Smith and Akstinaite, 2022). During this difficult transition to organizing more sustainably, it is important to create conducive environments and foster positive relationships. Experiential activities that promote reflection and contemplation may result in the generation of fresh insights and intuitions (Sadler-Smith and Shefy, 2007). Such changes allow for the growth of eco-friendly, sustainable practices in the workplace (Küpers, 2020). This resonates with the kind learning environment of an organisation required for fostering human intuition (Hogarth, 2001; Hogarth et al, 2015). From the viewpoint of stakeholders, a sustainable capability approach accords due credit to plants, sea and tank fish, and other forms of ecological life (Driscoll and Starik, 2004; Haigh and Griffiths, 2009). Marine science, however, cautions that the situation is likely to be even more complex. There is a struggle between prioritising the environment (Oceans as natural capital) and prioritising people (Oceans as livelihoods), as well as between prioritising business (Oceans as a profitable venture) and prioritising technology (Oceans as an engine of innovation) (Boschetti et al, 2020). In line with empirical studies (Douglas and Wildavsky, 1982; Douglas, 1978), this conflict is universal. When people disagree, it’s because they have different ideas about how power should be distributed in society. These ideas are linked to how to manage the environment (Price et al, 2014), which in turn is linked to how to balance the environmental, social, and economic aspects of sustainable development (Boschetti et al, 2020). Küpers (2020) expresses a degree of confidence in resolving these difficulties but emphasises the need to alter routine path-dependent practices. This requires identifying opportunities to disrupt, reorient, and/or redirect these practices towards more sustainable forms of realisation (Hargreaves, 2011). However, Fulton (2021) uncovered psychological barriers among decision-makers in marine resource management, which likely stem from cognitive bias within individual organisations and challenging (unkind) learning environments (Hogarth et al, 2015). Learning occurs frequently, but often does not aim to challenge the status quo (Blackman et al, 2004). Instead, it can result in organisational traps (Argyris, 2010) that stem from cognitive biases. Documented in the socioecological sphere of the marine environment, these traps are indicative of cognitive fallacies and a lack of wisdom. The findings by Björkvik et al (2020) show that falling into a socioecological trap is a path-dependent phenomenon. Again, the implications of this discovery for management are that escaping the socioecological trap will grow progressively more difficult over time, as already indicated by Fulton (2021) and noted by organisational scholars (Sydow et al, 2020).

In these situations, cognitive biases affect not just an individual but also a collective hubris that permeates organisations and institutions (Sadler-Smith and Akstinaite, 2022). The ongoing overfishing and extinction of species exemplifies collective hubris in fisheries (Kurien, 2014), and, by analogy, an overconfidence in rational technical approaches in aquaculture may foster problematic environmental impacts. Such an overconfidence bias can make it difficult to integrate intuitive expertise and local ecological knowledge. Sadler-Smith and Akstinaite (2022) further draw on Bordoni (2019), who labels this as humanity’s arrogant propensity to push boundaries in the name of “progress”, even though this often has negative consequences due to people’s apathy and avarice. This aligns with the findings of Johnsen et al (2009a), as well as Johnsen et al (2009b), which suggest that an excessive dependence on global knowledge and adherence to “rational” science can override actions based on socioecological wisdom. For instance, Haynes et al (2015) discovered a link between greed and hubris in business settings, which, when combined, negatively impacts environmental, social, and governance issues by encouraging risky behaviour among entrepreneurs. Many people agree that minimising losses through cost-effective production is the best way to mitigate risk; Ahsan and Roth’s work (2010), for instance, suggests that these connections also apply to aquaculture economics, which relies on global harvesting knowledge while neglecting local ecological knowledge.

People are paying more attention to whether fish farmers are making wise and sustainable management decisions. This brings up a broader point, which is that addressing the problem of sustainability requires both compliance and control (e.g., through governance and risk assessment, as well as changes to the market rules) and moral character (Sadler-Smith and Akstinaite, 2022). When we pay more attention to the use of intuition and deliberation in aquaculture, we can tap into the relevant virtue of practical wisdom.

We propose that people’s use of intuition can be trained to further help prudential administration (see, e.g., management education that can be applied to the management of fish farms, Sadler-Smith and Shefy, 2007). Specific training methods include meditation, body scans or going outside (Daudén Roquet and Sas, 2020; Sadler-Smith and Shefy, 2007). One way to foster growth in moral and professional excellence is to increase understanding of the relationship between System 1 and System 2 thinking. Communities built via such efforts can better put virtue ethics into practice (Koehn, 2020) and make holistic decisions in complex contexts. We suggest that training people to use intuition can enhance the prudential management of fish farms. One way to foster growth in moral and professional excellence is to gain a better understanding of the relationship between System 1 and System 2 thinking. Communities formed through such efforts can better put virtue ethics into practice (Koehn, 2020) and make holistic decisions in complex contexts. To train human intuition, you must make it a more deliberate process. The first step in training intuition as a competence is to learn to distinguish intuitions from emotions (Moring, 2023b). When using System 2 thinking to make decisions, we first assess the situation, weigh up the alternatives, question them, and consider the potential risks. Sometimes the perceived risks are too great to make decisions or act, even though we know what to do. To overcome the “knowledge action gap”, we need to recognize it as such and practice dealing with it differently. It’s important to put the hindering rationale (e.g., an external judgement) into context so we can make our own decision. A wide variety of training courses have been developed for this purpose, in which the focus is on calming down, engaging with the unconscious, and experiencing one’s own body (Sadler-Smith and Shefy, 2007; Vaughan, 1979). Intuition should be experienced, practised, and tested in training. It is particularly important to distinguish intuition from fears and hopes that prevent us from making decisions. Moring (2023b) suggests that training in nature outside of the built environment is particularly suitable for this. Natural environments offer a change of perspective; do not demand optimal solutions and do not ask for justifications. You could compare perceiving one’s own intuition to experiencing stage fright before a performance. We cannot simply turn off the attraction of intuition, which leaves us with no other choice. We know it; the essentials of our thinking become clear, and that is the difference between fears and hopes. When people develop this perception of intuition, they can use this capability in every new situation. Since the publication of “The Awakening Intuition” by the psychologist F.E. Vaughan (1979), who aimed to promote awareness of intuitive powers through exercises, many training courses have been generated. For example, Betsch and Haberstroh (2005) offer a model in “The Routines of Decision Making” that can be utilised to combine intuitive behaviour and rational thinking for decision-making. The goal of the six-step procedure is to first provide intuitive solutions and then enhance them with solutions derived from rational processes. They hope to remind people of their previous learning and life experiences while also demonstrating the power of intuition. R.M. Hogarth (2010) defines seven principles that facilitate the enhancement of human intuition. He stresses the importance of feedback: “Clearly, the key to developing ‘good’ intuitions is to be in a decision making environment that provides accurate and timely feedback.” Moring (2023a) eventually finds that developing intuition necessitates a fine sense of perception. He distinguishes it from the “understanding of historical civilizations that everything is connected and everything is in a common movement”. His training includes the following elements: Getting to know your fears, desires, and intuitions; Recognizing unconscious knowledge; Coming to rest; Questioning the body; Practising frequently; Practising connectivity.

To fully realise the potential of AI-supported intuition, it is essential to invest in training and education programs that teach individuals how to effectively use AI tools and interpret their outputs. This includes developing skills in data analysis, machine learning, and critical thinking, as well as understanding the limitations and biases of AI systems. By equipping individuals with these skills and knowledge, organisations can ensure that they can use AI effectively to support both inferential and holistic intuition.

After analysing how people make decisions in practice (Lebel et al, 2021), it is important to consider the perceived discretion of decision-makers (Wangrow et al, 2015) when designing training sessions with practitioners. To self-report one’s own discretion to act, is to ask oneself: am I consciously choosing one amongst several alternatives, when taking a decision, or am I simply “doing” what the practice field requires me to do? This perceived discretion to act can differ considerably across industry sectors (Svenson et al, 2023a; Svenson et al, 2023b; Svenson et al, 2023c; Svenson et al, 2024) and country contexts (Svenson et al, 2025). To foster wise practice, businesses must equip their employees with the tools of intuition and reflection. While specialised fields widely recognize intuitive reasoning, its acceptance as a foundation for decision-making (Svenson et al, 2023c) is not universal. When aquaculture organisations plan to follow virtue ethics, they must ensure that people can use their intuition as a resource. Moore (2012) provides an empirical example, and Sadler-Smith (2012) and Moore (2008) emphasise the benefits of participation in communities of practice to affect actors’ moral development. Mental simulation can hone expertise and intuition, preparing people to effectively respond to novel and complex situations (Steffen et al, 2020).

We need more empirical studies using qualitative research methodologies, given the scarcity of literature on intuition in aquaculture (and fisheries). Given the more developed interest in the subject of intuition in agriculture, an integrative literature review or a systematic literature review might highlight additional requirements for studies of decision-making in marine management contexts. This article used knowledge concepts from marine social science, and future research should integrate knowledge concepts from information systems research (Harfouche et al, 2023) with an empirical study of day-to-day decision-making in aquaculture. The ethical and social implications of relying on AI in complex decision-making contexts, as well as its potential role in supporting intuition, warrant further investigation. This should be grounded in an AI ethic that claims, “Artificial intelligence cannot and will not replace human decision-making, judgement, intuition or ethical choices” (IBM, in Krüger, 2021, p. 443). The purpose of AI should be to enhance human capabilities rather than replace them, as AI has no subjective experience and consciousness. An AI is incapable of comprehending human experience and the sensations associated with intuitive decision-making. In terms of intuitive decision-making, it can enhance our ability to understand our emotions more accurately. Intuition training necessitates the capacity to differentiate intuition from emotions, particularly when intense emotions, such as fear, can obscure the subtle voice of intuition (Moring, 2023b). AI could monitor physiological changes, such as in athletes, to determine or target mood states that encourage intuitive decision-making (Weber-Guskar, 2024). The findings on System 1 and System 2 thinking can be applied in practice, such as in the development of training programs or decision support tools for aquaculture managers. Action research methodologies (Hadjimichael et al, 2024) can be used to get at the meaning aquaculture decision-makers ascribe to their actions. Through such studies, wise practice (Rooney and McKenna, 2008) in aquaculture could be exemplified.

In the preceding sections, we have put the results of the literature review in the context of dual-process theories of cognition, artificial intelligence, and virtue ethics. The contributions of the article (Snyder, 2019) lay out several avenues for future research, which may find inspiration in our work. Many people favour rational scientific models, but they fail to adequately depict the complexity of the issues involved in aquaculture management. To make sound judgments, managers need access to timely and reliable projections of complex circumstances, and technology will continue to play a major role here. Due to the time and accuracy constraints of cognitive analysis, fish farmers frequently must rely on gut instinct. Intuition can access implicit information, which is not easily transferable, and provide insight into more comprehensive solutions.

Existing research suggests that many fish farmers use intuition, which has major benefits. We recommend focusing more on assisting fish farmers in refining their intuition with the objective to enhance farmers’ current analytical methods, not replace them. We have also attempted to highlight the implications of using both intuition and deliberation to improve the aquaculture industry’s moral development. Furthermore, we have highlighted the possible role of AI applications to foster different types of intuition to make wise decisions. The process of developing one’s intuition promises a deeper connection to the natural world. A recent study using intuitive inquiry seems to confirm this. The study examined women’s transforming experiences during long distance running in nature detailing its effect on embodiment and psychospiritual development (Ludwig, 2019). Future research should try to trace these effects with aquaculture practitioners. The assumption that fish farmers could benefit from the ability and propensity to make use of the untapped, free resource of their intuition for ecologically coherent management decisions has been suggested in research on ecology and society (Folke et al, 2010; Scheffer et al, 2015) and holds further potential for adaptation in aquaculture decision-making.

The data that supports the results and analysis refers to the literature cited.

FS and MB made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. FS was responsible for data acquisition, while both FS and MB conducted the data analysis and interpretation. The manuscript was jointly drafted and critically revised by FS and MB. Both authors approved the final version for publication and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the research.

The authors like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. The first author thanks Jahn-Petter Johnsen and Svein Jentoft at the Norwegian College of Fishery Science, UiT The Arctic University of Norway for helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

Given his role as a Guest Editor of the MREV Special Issue, FS had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and had no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to SJ.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.