1 Business Psychology Division, College of Graduate and Professional Studies, The Chicago School, Chicago, IL 60654, USA

Abstract

Trust in corporations is down, information is abundant, and technology is developing faster than ethical review boards can keep pace. Now, more than ever, it falls to business leaders to make decisions that benefit the common good and promotes the health and welfare of all stakeholders (e.g., shareholders, employees, customers). Drawing on historical theories of wisdom introduced by Greek philosophers and further developed by psychologists and economists, practical wisdom can positively impact decision-making in business leadership. This paper presents insights from an experimental study on how nudging for wise reasoning strategies may influence decision-making regarding ill-structured problems for the common good. Study participants (n = 419) reviewed a fictitious ill-structured business problem and made a pre-study yes/no vote. Participants were randomly assigned to either the control group or one of two experimental arms: the nudge perspective (NP) group or the nudge uncertainty (NU) group. The experimental groups were provided with a short wise-reasoning nudge and asked to vote again. The NP group received information providing a new perspective on the problem, and the NU group received a prompt to consider future uncertainty. The control group participants reported the highest confidence in the quality of their decision-making processes and in the wisdom of their decisions but were also significantly more likely to report after the fact that they wish they had considered ethics in their decision.

Keywords

- wisdom

- wise reasoning

- decision-making

- uncertainty

- nudges

The world is in a trust crisis (Edelman, 2022; Edelman, 2023). Fake news, divisive governments, economic anxieties and mass class divides have created a battle for truth. At first glance, the notion of wisdom seems like a quaint relic from bygone eras. In contemporary times of relentless capitalism with high-speed and high-stakes technological innovations, other imperatives seem more pressing: profit, power, and political clout, to name a few. Over time, the emphasis on these short-term outcomes has led to an erosion in the fabric and culture of organizations and even society at large, with pervasive problems in trust at all levels, but particularly in leadership.

The erosion of trust in public institutions due to issues like incompetence, overconfidence, and ethical concerns (Edelman, 2023; Maxwell, 2019a; Sternberg, 2021) has highlighted the critical role trust plays in maintaining a thriving and effective society (Kozinets et al, 2020; Schneier, 2013). In the realm of business, trust stands as one of the most vital forms of capital for effective leadership (Frei and Morriss, 2023). Leaders have higher levels of loyalty and trust when they interact in a wise and mature manner (Lewicki, 2007; Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019). The demand for wise leaders who can navigate complex, morally ambiguous challenges during uncertain times and restore trust is a worldwide imperative.

Globally, leaders face complex, “ill-structured” problems, those with no clear-cut or obvious solutions, threatening humanity (Sternberg et al, 2019; Sternberg, 2021). Ill-structured problems are those that require trade-offs, include incomplete information, or have unclear goals. These problems cannot be resolved with traditional logical analysis. The fallout from multiple wars on global trade and the economy, pandemics, climate change, and data breaches reverberate across the globe, to name a few, are examples of pressing, ill-structured problems with global implications that demand leaders to protect the common good to benefit all stakeholders, not just shareholders (Kessler and Bailey, 2007; Sternberg and Glück, 2022). The world has seen a rise in incivility, proliferation of misinformation, distrust in political institutions, and lack of ethical considerations in today’s use of information and technology (Grossmann et al, 2020a). There is an urgent need for a resurgence in understanding wisdom in corporate and organizational leadership to address the growing complexities and uncertainties in the global environment and, by extension, foster trust in employees, consumers, and other stakeholders (Kessler and Bailey, 2007; Sternberg, 2021). Zacher and Kunzmann (2019) argue psychological research on wisdom has largely neglected the workplace as an important context to study wisdom and encourage more research that investigates how wise individuals can affect positive changes in contemporary organizations.

Wisdom, in the context of the workplace, includes three strategies: (a) the ability to discern complexity considering future uncertainty, (b) perspective-taking, and (c) intellectual humility (Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019); and if one is not trained for wisdom, it has little chance of being expected (Kessler and Bailey, 2007). Cultivating wisdom in individuals offers specific advantages to the workplace. Wisdom helps individuals see problems not in isolation but as multiple contextual layers, increasing awareness of short- and long-term causes and consequences that shift over time. Wisdom includes perspective-taking: understanding problems from different lenses and integrating viewpoints to maximize a common good outcome. Additionally, concomitant with wisdom is an understanding of the limits of one’s knowledge. As Kessler and Bailey (2007) state, “knowledge gives us the means, but wisdom provides the context and direction” (p. xxiii).

Wise leadership in the workplace is “an integrative and holistic characteristic that can lead to better solutions for many, not only one person” (Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019, p. 271). However, empirical research on the positive role of wisdom in solving problems in the workplace and how to foster wisdom for wise outcomes at the individual level is limited (Glück and Weststrate, 2022; Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019). There is an abundance of research on individual wisdom as a personality trait studied by psychologists (Ardelt, 2004; Glück and Weststrate, 2022; Sternberg and Karami, 2021), and another body of literature on organization wisdom studied by academics in business and management science (Cortez and Johnston, 2019; Kessler, 2006). However, there is a gap in research attempting to understand the process of wise reasoning at the individual level in the business environment that contributes to organizational wisdom. Where organizational wisdom studies the collection, transference, and integration of individuals’ wisdom for strategic action (Kessler, 2006), personal wisdom is the integration of cognitive, reflective and affective personality qualities (Ardelt, 2003). This paper describes a study investigating whether wisdom in a business context can be fostered with a short-term intervention termed a “wise-reasoning nudge”.

The notion of wisdom dates back to the earliest documented texts in antiquity, where philosophers and theologians conceived of wisdom as both an intellectual and moral virtue grounded in a deep understanding of life acquired through sound reasoning, judgment, and virtuous habits (Shoup et al, 2022). Prior to Socrates and the Greek Enlightenment, wisdom was defined in terms of making sense of life, understanding the right order of human action, living justly and honestly, and keeping individuals and the state in balance (Edmondson and Woerner, 2019). Throughout history, wisdom has been defined as foundational in supporting the common good in society by individual wise behavior. Researchers use this to build their theoretical frameworks for understanding wisdom. For the purposes of this paper, given Western hegemony in the structure and functioning of corporate organizations, we limit our review of wisdom primarily to the Western canon.

Aristotle was the first to introduce phronesis, or practical wisdom, allowing people to discern the Golden Mean and the right ways to act in each situation within the context of the situation. It is phronesis that facilitates wise reasoning (Grossman et al, 2019; Shoup et al, 2022). Aristotle’s version of practical wisdom is significant in that it stresses how decisions are made within the context of situations, portraying action as a dynamic, complex process (Woerner-Powell and Edmondson, 2019). The action considers the ultimate goal of a person’s life within the context of the community one belongs to. Schwartz and Sharpe (2019) describe wisdom as one’s “true north” compass that serves as a guide to keep one on the right path with purpose. Aristotle’s work has contributed to the application of wisdom in everyday life.

Since the 1970s, psychologists have been endeavoring to define wisdom and, more recently, what wisdom looks like in real-life outcomes among corporate and political leaders, describing it as a multifaceted construct encompassing cognitive, reflective, and affective components (Ardelt, 2003; Clayton, 1976). Wise individuals can balance self-interest with the interests of others and the interests of society in pursuit of a common good (Sternberg, 1998). Rather than looking at wisdom as a transcendent state in older age, some researchers view wisdom as a context-specific trait that can be fostered (Grossmann, 2017b; Santos et al, 2017). Wisdom activates a “pause” button, interjecting decision-making with reflection, asking oneself not how to do something but when and under what circumstances one should do something (Clayton, 1983; Kessler and Bailey, 2007; Liautaud, 2021). Wise individuals possess a sense of mastery in understanding uncertainty, empathizing with others’ perspectives, and navigating emotions through reflection (Glück et al, 2019b) and wise leaders build trust by demonstrating logic, authenticity, and empathy (Frei and Morriss, 2023).

Wise leadership is displayed at the organizational level by fulfilling visions and solving problems by demonstrating creativity, intelligence, and technical expertise, while balancing interests and perspectives to seek a common good outcome (Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019). Across disciplines, the consensus is that individuals who engage wisdom in their decision-making are more likely to arrive at ethical solutions that prioritize the well-being of all stakeholders (Freeman et al, 2007; Karami and Parra-Martinez, 2021). In the business environment, wise leaders are not solely focused on shareholders but consider employees, customers, communities, and society at large in the decision-making process. Examples include global beverage companies creating a positive water balance, manufacturing companies reducing waste in supply chains, and consumable goods companies practicing fair trade and ethical sourcing.

Despite the consensus on the need for wisdom in leadership, scholars have yet to come to a consensus on a definition of wisdom (Glück and Weststrate, 2022; Sternberg and Glück, 2022). This divergence has led to jingle-jangle fallacies, with each researcher defining wisdom from their unique perspective (Grossmann et al, 2020a; Intezari and Pauleen, 2018; Maxwell, 2019b; Sternberg and Glück, 2022; Sternberg et al, 2019; Wolcott, 2020). However, consistent across these disparate definitions of wisdom is a pursuit for the common good, balancing the interests of all stakeholders, with an infusion of morally grounded excellence in social-cognitive processing (Grossmann et al, 2020a; Sternberg and Glück, 2022).

Wisdom distinguishes itself from practical intelligence by its orientation towards maximizing the common good rather than individual well-being (Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019). Few would contest that each of us bears some responsibility for humanity’s well-being. The common good must consider what is best for all those affected by one’s decisions (Sternberg, 2021) and can serve as a compass for good decision-making. Maxwell (2019b) contends that wisdom inquiry should prioritize aiding humanity in resolving its challenges across political, social, industrial, economic, and institutional spheres, facilitating progress toward a better world for all.

Decision-making in pursuit of the common good necessitates balancing what is in the best interest of the self (intrapersonal), others (interpersonal), and larger societal interests (extrapersonal) over the short- and long-term (Sternberg and Karami, 2021; Sternberg, 1998). Even if there is uncertainty around what the common good is, acting wisely at least tries to consider how one’s actions will affect others (Sternberg, 2021). Wise leaders not only need to seek the good, they need to work against the bad (Arthur et al, 2021), that is, what may harm others or operate to their detriment. As operationalized for this paper, the pursuit of the common good demands setting aside self-interests and making decisions that benefit the whole—feats that both require and exemplify wisdom to navigate the path to these ends.

Applying practical wisdom (i.e., wise reasoning strategies) to complex problems has yielded promising results. Research demonstrates that the use of wise reasoning strategies helps foster positive relationships with diverse groups, reduces polarization, and balances intergroup attitudes (Brienza et al, 2021; Santos et al, 2017), arguably serving to meet the common good. Wise reasoning propels people to solve problems with deeper reflection and the ability to see the bigger picture (Brienza et al, 2021). While most research on the application of wise reasoning has focused on social and interpersonal conflicts, the potential of wise reasoning strategies in the realm of business decision-making remains an underexplored topic of inquiry (Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019).

Wise reasoning is a unique decision-making process and an invaluable asset for societies (Grossmann and Dorfman, 2019). It includes dimensions of intellectual humility (Grossmann et al, 2020b), emotional regulation (Ardelt, 2003; Glück and Bluck, 2013; Glück et al, 2019a), perspective-taking, compromise-seeking (Grossmann et al, 2020a; Sternberg and Karami, 2021), and the ability to envision potential paths into the future (Baltes et al, 1995; Sternberg and Karami, 2021; Sternberg, 1998). These metacognitive processing characteristics not only help manage existing conflicts, but can also be used to avoid future conflicts before they arise (Grossmann and Dorfman, 2019). In a study to define wisdom the components to foster wise reasoning, Karami et al. (2020) proposed a wise person has “the ability to effectively choose and apply the appropriate knowledge in varying situations” (p. 246).

Empirical research suggests wise reasoning is malleable across situations people encounter, less a biologically grounded disposition, and more in how one expresses oneself when facing difficult life situations (Glück and Weststrate, 2022; Glück, 2020; Grossman et al, 2019; Grossmann, 2017a; Grossmann et al, 2021; Jeste and Lafee, 2020). Research focused on the process of wise reasoning suggests it is a stable, latent component distinct from intelligence and personality traits and variable even among people nominated as wise (Brienza and Grossmann, 2017; Grossmann and Dorfman, 2019; Santos et al, 2017). As research on wise reasoning evolves, it is shown to be distinct from intelligence and personality traits and appears to be malleable in various contexts and can be fostered.

In the context of decision-making and wise reasoning, Stanovich (2001) proposed a tripartite model of mind that provides a valuable framework for understanding how individuals process information and make decisions. The model distinguishes between the autonomous mind, the algorithmic mind, and the reflective mind—the latter being particularly relevant to this study. The reflective mind encompasses metacognitive processes, and plays a crucial role in how individuals evaluate and revise their beliefs and decisions when presented with new information. This framework aligns closely with the objectives of this study, which examines how nudges can influence decision-making confidence and the application of wise reasoning strategies.

In an era marked by constant change and uncertainty, a critical leadership skill is the capacity to effectively manage change through foresight—a skill particularly valuable in uncertain and volatile times. The future of ethical and robust leadership necessitates a holistic approach to decision-making that invokes wisdom.

The overarching aim of this study was to investigate the potential impact of implementing a nudge designed to promote wise reasoning strategies, notably perspective taking and future uncertainty management, on participants’ decision-making processes and their confidence in their decision-making processes. For the purpose of this paper we use the operating definition of a nudge by Thaler and Sunstein (2021), “any aspect of choice the architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives” (p. 8). Nudges are typically beneficial when decisions are at risk of receiving insufficient attention, when decisions are inherently difficult, or when individuals are faced with situations that are unfamiliar or rare. In this study, the nudges are intended to reframe the business problem, leveraging the power of perspective-taking and future uncertainty considerations to encourage deeper reflection and wiser decision-making. By reframing the business problem through these nudges, we aimed to prompt participants to think beyond immediate gains and consider broader ethical and long-term implications, aligning with the powerful influence of framing nudges as described by Thaler and Sunstein (2021).

Leaders are frequently taught to prioritize confidence over acknowledging fear. Yet, astute leaders recognize the danger of imprudence, whereas imprudent leaders remain untroubled by fear (Solansky, 2014). Since the pioneering work of Tversky and Kahneman (1974) and Loewenstein and Thaler (1989) around decision-making science and the mistakes people make, two trends have appeared in the mainstream: avoiding biases and minimizing noise (i.e., inconsistencies) to make better decisions (Kahneman, 2011; Kahneman et al, 2022; Thaler, 2017). It is imperative to highlight the perils of overconfidence, which, as summarized by Kahneman (2011), represents “…a puzzling limitation of our mind: our excessive confidence in what we believe we know, and our apparent inability to acknowledge the full extent of our ignorance and the uncertainty of the world we live in” (p. 13–14). Optimistic individuals play a significant role in shaping society: they are often entrepreneurs and political and military leaders who reach success by taking risks when faced with challenges (Kahneman, 2011), are visionary, reflective and flexible in their leadership style (Techo, 2021). While confidence and optimism are positives, overconfidence poses challenges.

Sternberg (2019) posits that the antithesis of wisdom in decision-making is foolishness, including unrealistic optimism (“if it’s my idea, it must be good”), and false omniscience (“I know everything I want or need to know”). Paradoxically, high intelligence can become a risk factor for foolishness because “people who are highly intelligent may believe they are immune to foolishness” (p. 7). The concern is that there has been excessive focus on developing intelligence (IQ) and knowledge (domain-specific), which can be competitive and self-serving at the expense of fostering wisdom. Domain-specific intelligence is self-focused with less emphasis on the common good (Sternberg, 2019). While IQ is undeniably important, it offers no guarantee of societal improvement; intelligence can be leveraged toward nefarious ends as much as noble ones (Sternberg, 2019). On the other hand, wisdom encompasses morally grounded excellence in social-cognitive processing by applying meta-cognitive reasoning to problem-solving with a foundational consideration being shared humanity (Grossmann et al, 2020a).

Psychologists refer to cognitive perspective-taking as trying to understand another person’s thoughts, feelings, attitudes, interests, or concerns for a particular situation (Epley et al, 2006). It is the consideration of multiple viewpoints and the synthesis of opposing views that is a requirement of wisdom (Karami et al, 2020). To reach a common good, perspective-taking is not only related to people’s perspectives, but also to ethical and moral ones. For instance, stem cell research holds promise for unlocking critical insights into human development and offers hope for treating diseases like diabetes, spinal cord injuries, and Parkinson’s disease, among others. However, it also raises contentious ethical and political issues, exemplifying an ill-structured problem that demands multiple perspectives but often becomes entangled in disputes concerning human personhood and reproduction (Lo and Parham, 2009).

Perspective-taking enhances wiser decision-making because it transports individuals into alternative narrative worlds (Weststrate, 2019). Perspective-taking can promote experience-taking, which has been linked to more favorable attitudes about marginalized populations (Weststrate, 2019), which businesses often do not consider in their decision-making. Empirical studies have linked perspective-taking to increased levels of empathy and prosocial behavior, potentially encouraging cognitive and behavioral changes toward social equity (Weststrate, 2019).

Wisdom embraces uncertainty by adapting to existing environments, shaping future environments, and creating new ones through goal-directed thoughts, emotions, and actions to confront social challenges. Thus, a wise person embraces uncertainty for future decision-making. When examining the purpose of wisdom and its impact on the common good, it becomes evident that the common good materializes over the long term as well as in the short term (Sternberg and Karami, 2021). Arguably, wisdom almost always considers uncertainty of the future, whether it is short- or long-term thinking.

Wise leaders acknowledge their limitations and the impossibility of knowing everything, including the trajectory of the future, in their decision-making while planning for uncertainty. Short-term thinking can be a significant barrier to wise reasoning. For example, leaders face pressures to net short-term financial results, which is often at odds with holistic and balanced thinking that considers long-term implications (Elangovan and Suddaby, 2019). Capitalism is under scrutiny; globally, people believe CEOs manage companies overly focused on short-term goals for shareholders. Wise leaders demonstrate dialectical thinking by recognizing the ever-changing nature of the world (Kross and Grossmann, 2012), understanding that what is deemed “right”, “correct”, or “appropriate” in one moment may not be in the future as more information becomes available or more perspectives are shared (Sternberg and Glück, 2022).

In a world struggling with uncertainty and a global trust crisis, leaders are challenged to make decisions when presented with ill-structured problems (Brienza et al, 2018; Kozinets et al, 2020; Sternberg and Karami, 2021). Wise leaders can articulate the desired outcomes of their decisions, express a commitment to meeting the needs for whom they are responsible, have the capability to reconcile conflicting perspectives, an inclination to seek input from others, and the capacity to harness emotions in the service of rationality (Schwartz and Sharpe, 2010). This study looked at how to foster wisdom. Specifically, it asked whether nudging for wise reasoning strategies when faced with a complex, ill-structured business problem strengthens wise reasoning.

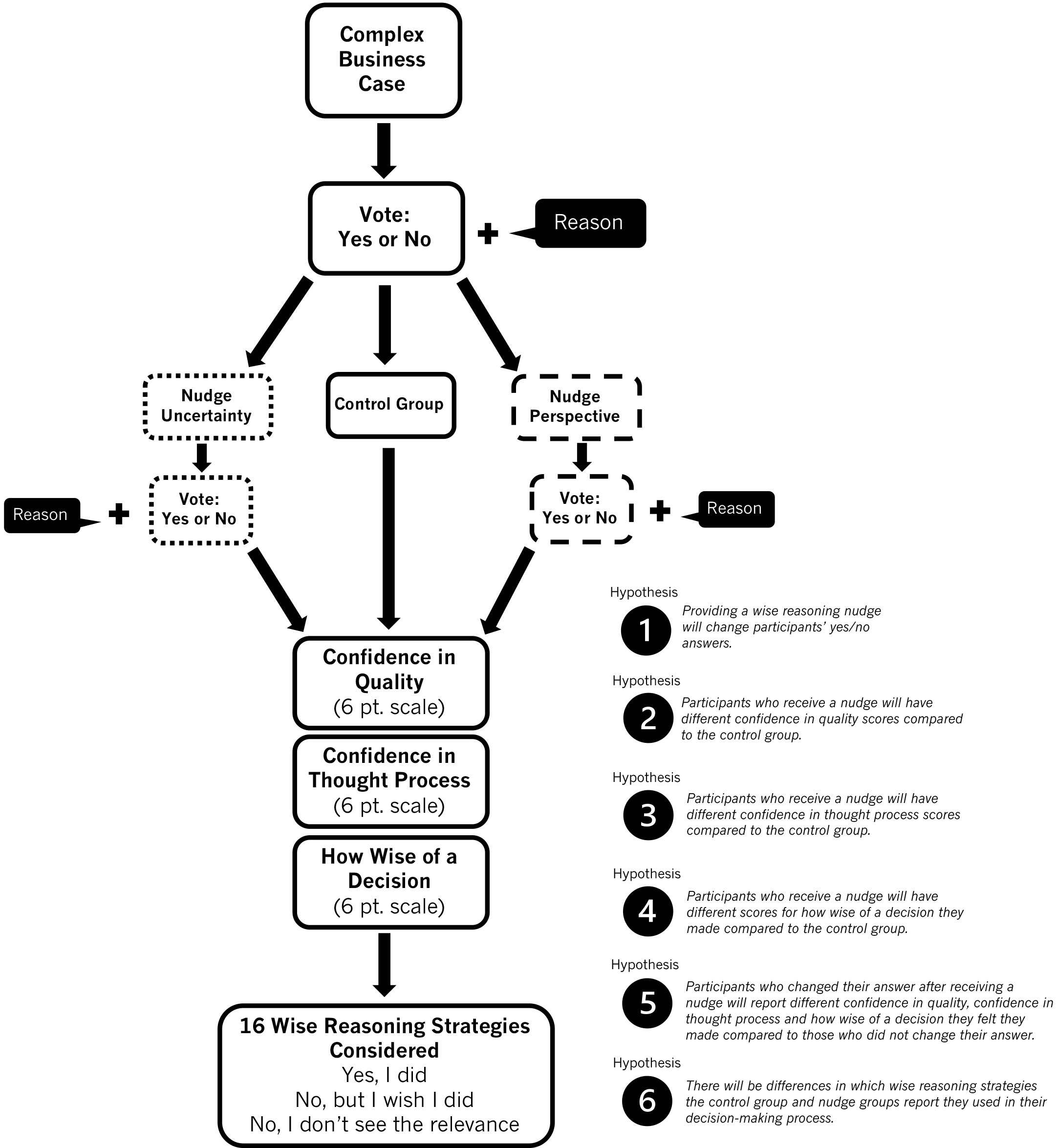

A decision-making experiment for an ill-structured problem using wise reasoning nudges was used to determine whether such nudges can foster wise reasoning. This study aimed to determine the impact of wise reasoning nudges, specifically those for perspective-taking or uncertainty, on individuals’ decision-making processes. We postulated that providing a wise reasoning nudge would alter participants’ pre-post responses, influencing their decision outcomes. Additionally, we investigated the variations in participants’ confidence levels regarding the quality of their decision (CIQ), thought process (CITP), and how wise of a decision they felt they made (HWD) following a wise reasoning nudge. Our hypotheses were that participants exposed to a nudge would exhibit different mean scores in confidence measures compared to the control group.

Moreover, we explored the confidence levels of participants who changed their decisions after receiving a nudge, hypothesizing that those who changed their decisions would report lower mean scores in confidence metrics compared to those who maintained their initial decisions. This hypothesis is based on the expectation that reconsidering one’s initial decision in light of new information would lead to increased uncertainty and self-reflection, resulting in reduced confidence in the decision-making process. Prior research suggests that individuals who engage in self-reflection and reconsider their initial choices in response to new information often experience increased uncertainty and reduced confidence (Loewenstein and Thaler, 1989; Tversky and Kahneman, 1974). Therefore, we expected that the act of changing one’s decision would be associated with a decrease in perceived confidence in the quality of the decision, the thought process, and the wisdom of the decision.

Furthermore, we examined the potential differences in wise reasoning strategies employed by the control group and nudge groups. We hypothesized that participants who received a nudge would report utilizing distinct wise reasoning strategies in their decision-making processes compared to those in the control group. To measure wise reasoning strategies, participants were asked to reflect on their decision-making process and respond to specific questions designed to capture various dimensions of wise reasoning. These questions were informed by established frameworks in the literature on wisdom and decision-making (Brienza et al, 2018; Grossmann et al, 2020b; Sternberg and Karami, 2021).

A survey developed in the Qualtrics online survey platform tool posed a fictitious business case to participants. Survey participants were recruited from Cint, a U.S.-based market research panel sample company that provides respondents for survey sampling to achieve a representative sample of ages, genders, education levels, races, and employment levels. Population size was determined using the statistical software package G*Power (version 3.1.9.6; Faul, Erdfelder, Lang & Buchner, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) (Faul et al, 2007). An a priori power analysis was conducted for an F-test (Analysis of Variance) with three groups, with an alpha level set at 0.05, at 80% power, in order to detect a medium effect size. Based on these parameters, G*Power recommended a minimum sample size of 246 participants. However, to increase the robustness of our findings and within the constraints of our budget, we recruited up to 669 participants, of which 419 were included in the final analysis after excluding low-quality responses. The final sample (n = 419) was comprised of 180 males, 232 females, and seven non-binary individuals. Most were employed (365), and over half (288) held at least a 4-year undergraduate degree. The participants predominately identified as White (326), with some representation of Black (52) and Asian (18) individuals (see Table 1).

| N (419) | Percentage | ||

| Age | |||

| Under 26 (Gen Y) | 28 | 7% | |

| 26 to 41 (Millennials) | 144 | 34% | |

| 42 to 57 (Gen X) | 166 | 40% | |

| 58 to 76 (Baby Boomers) | 79 | 19% | |

| 77 or older (Silent/Post War) | 2 | 0% | |

| Gender | |||

| Males | 180 | 43% | |

| Females | 232 | 55% | |

| Non-Binary/Other | 7 | 2% | |

| Race | |||

| Alaska Native | 2 | 0% | |

| American Indian | 8 | 2% | |

| Asian | 18 | 4% | |

| Black or African American | 52 | 12% | |

| Native Hawaiian | 1 | 0% | |

| Pacific Islander | 1 | 0% | |

| White | 326 | 78% | |

| Other/Prefer not to answer | 30 | 7% | |

| Education Level | |||

| High school graduate | 9 | 2% | |

| Some college but no degree | 12 | 3% | |

| Associate degree in college (2-year) | 110 | 26% | |

| Bachelor’s degree in college (4-year) | 173 | 41% | |

| Post Bachelor’s degree work/certificate | 13 | 3% | |

| Master’s degree | 80 | 19% | |

| Doctoral degree/Professional degree | 22 | 5% | |

| Employment Status | |||

| Working | 365 | 87% | |

| Retired | 32 | 8% | |

| Other/not captured | 22 | 5% | |

| Employment Level | |||

| Entry level and Support | 143 | 34% | |

| Management and Professional | 166 | 40% | |

| Business Leadership | 56 | 13% | |

| Other/not captured | 54 | 13% | |

Participants were asked to read the business case study as if they were personally involved with the company and an urgent decision needed to be made (see Fig. 1). A summary of the business case is as follows:

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Survey Design and Hypotheses for Nudges for Wise Reasoning Strategies.

Smart Toilets, a company offering wellness toilets equipped with bio-medical health-tracking technology, aims to introduce its product at the International Consumer Technology Conference (ICTC). The decision to proceed is critical due to financial constraints and emerging competition. The Smart Toilet promises convenience, cost-effectiveness, and potential health benefits, but the looming risk of patent competition and financial pressure complicates the decision-making process for the board of directors. You sit on the board of directors and need to vote yes or no to move forward with introducing Smart Toilet at the ICTC.

Participants were told there are no right or wrong answers as the purpose of the study is to better understand how individuals make decisions with limited information. The business problem at hand seems straightforward at first glance, revolving around the urgent need to make a go-to-market decision to secure financial gains and maintain a competitive edge in the market. However, this decision is complicated by short-term pressures to drive sales, potentially overshadowing considerations of the long-term risks associated with introducing a novel bio-medical product without a comprehensive understanding of consumer adoption and acceptance. It prompts reflection on the distinction between mere intelligence and true wisdom: while technology enables product creation, the fundamental question remains whether it should indeed be brought to market. See full business case in Appendix A.

After reading the fictitious business case, all participants were asked to vote “yes” or “no” to introduce the new product at the upcoming conference to start taking orders and were asked to explain their answer. All participants were required to provide some explanation for their answer (open-ended response). Participants were then randomly assigned to be in one of three groups: the control group (n = 145), the nudge perspective (NP) group (n = 128), or the nudge uncertainty (NU) group (n = 146). See detail on nudges in Appendix B.

The two experimental nudge groups each received different, additional information intended to probe for wiser reasoning. The NP group read information that added a perspective from a medical professional voicing concerns about the risks of introducing the product as a consumer-friendly product rather than an in-home medical device under medical supervision. The NP nudge was designed to probe for the wise-reasoning strategy of perspective-taking. The NU group read information that included future risk consideration from an attorney suggesting doing pre-mortems on worst-case scenarios of violations of medical privacy. The NU nudge was designed to probe for future uncertainty. The control group did not receive additional information. The two nudge groups voted a second time after reading their respective nudges. If participants changed their answer, they were asked the reason (open-ended response) that made them change their answer. If participants did not change their answer, they were asked why they did not change their answer (open-ended response).

Both nudges invited participants to reflect on considerations about long-term risk, ethical implications, and uncertainty and added a new way to think about the decision in an attempt to increase the use wiser reasoning strategies used by broadening participants’ view beyond the short-term gain (profit) and minimize potential personal interest in the product (i.e., “I would like this product”). The decision-making experiment tested whether confidence in quality of the decision (CIQ), confidence in thought process (CITP), and how wise of a decision (HWD) participants felt they made were influenced by a nudge they received. The experiment also examined which wise reasoning strategies participants reported using in their decision-making process.

All participants (control, NP, and NU) answered how confident they were in the quality of their decision, how confident they were in the thought process they used in their decision, and how wise of a decision they felt they made. A 6-point Likert scale was used where 1 = low confidence/unwise decision and 6 = high confidence/wise decision. A 6-point Likert scale was selected so participants were forced to select a direction and avoid a midpoint. The mean scores for these variables were the primary dependent variables used for this study. Group assignment (control, NP, or NU) was the primary independent variable. In other words, does the group assignment (nudge or no nudge) change participants’ confidence, quality, and perception of how wise of a decision they made?

All participants (control, NP, and NU) were then asked about their consideration of wise-reasoning factors they considered in their decision-making process. Participants selected one of three options for each wise reasoning strategy: “I did consider this”, “I did not consider this, but I wish I had”, or “I did not consider this, and don’t see the relevance”. The following wise-reasoning factors were presented in randomized order:

1. Future implications

2. Uncertainty (e.g., intended usage vs. actual usage)

3. Financial benefits of being first to market

4. Perspective of others (e.g., employees, consumers, medical industry)

5. Financial risks of not moving forward

6. Short-term benefits of moving forward (e.g., financial resources to keep moving forward)

7. Short-term risks (e.g., funding has run out)

8. Long-term benefits (e.g., first to market with new technology)

9. Long-term risks (e.g., going to market too quickly)

10. Personal interest in product (e.g., I would want one)

11. Market opportunity (e.g., urgency around timing)

12. My personal values (e.g., value access to my health data)

13. Unintended negative consequences (e.g., targeted advertisements based on personal health data)

14. Societal benefits (e.g., what is best for the common good)

15. Ethical considerations (e.g., biomedical information shared on app, financial gain and risks)

16. Complexity of the problem (e.g., difficult to make the right decision)

The analysis assessed the change in decision-making between each group, mean scores in CIQ, CITP, and HWD, as well as what wise reasoning strategies each group used in their decision-making process. To test the differences between groups, chi-square analysis, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), and independent sample t-tests were conducted to test the statistical differences between the groups. Bonferroni and Games-Howell were conducted as post hoc comparisons between groups.

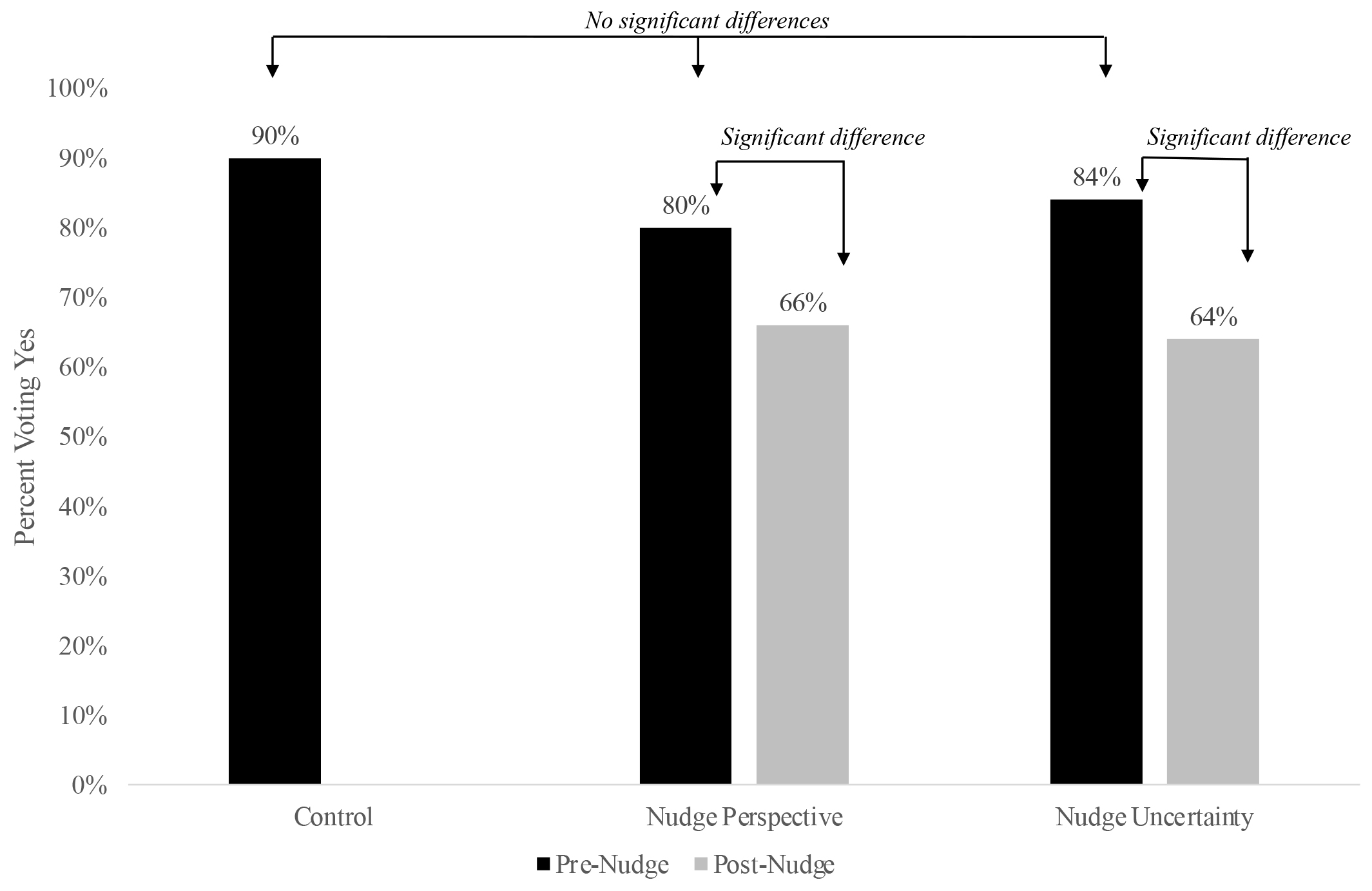

After reviewing the fictitious case prior to the random assignment of groups and exposure to nudges, 85% of the total sample (356) voted to move forward with the business concept, while 15% (63) voted not to move forward. To check for pre-intervention differences, a chi-squared test of independence was used to compare the frequency of initial yes/no decisions by members of each group. Of the control group, 90% voted yes (130), while 10% voted no (15). Of the NP group, 80% voted yes (103), while 20% voted no (25). Of the NU group, 84% voted yes (123), 16% voted no (23).

After the initial yes/no vote, the NP and NU groups were provided additional information (the nudges) and were asked to vote yes/no a second time. For the NP group, 14% changed their yes vote, decreasing from 80% to 66% who voted yes (84) and 34% who voted no (44). For the NU group, initially, 84% voted yes, while after receiving the nudge, 64% voted yes (92), a 20% decrease in yes votes (36%, or 54 now voted no).

A chi-square analysis between the groups (control, NP, and NU) was conducted to detect significant differences between the groups and their pre-nudge yes/no answers. A chi-square test of independence showed that there were no statistically significant differences between the control, NP, and NU groups for their original yes/no decisions,

| Pre-Nudge Vote | Post-Nudge Vote | |||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Control Group | 90% (130) | 10% (15) | - | - |

| Nudge Perspective Group | 80% (103) | 20% (25) | 66% (84) | 34% (44) |

| Nudge Uncertainty Group | 84% (123) | 16% (23) | 64% (92) | 36% (54) |

| Model Chi-Square pre nudge | 4.580 | 0.101 | ||

| Model df | 2 | |||

| McNemar Chi-Square pre/post NP | ||||

| McNemar Chi-Square pre/post NU | ||||

***= p

The results of the directional measures for nominal uncertainty coefficients revealed an approximate significance level of p = 0.101 for both Phi and Cramer’s V.

The number of respondents in each category are in parentheses.

NP, nudge perspective; NU, nudge uncertainty; df, degrees of freedom.

Two McNemar chi-square tests of independence were conducted to test the differences from the paired sample of the before and after yes/no vote for the NP group and for the NU group to detect pre and post differences. The McNemar chi-square test showed that there was a significant difference in decision-making before and after for the NP group, p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Percent Voting “Yes” Pre- and Post-Nudge by Group.

A sample of comments for the reasoning the NP group shared for changing their answers included responses such as:

■ “I agree with the physician. Only with a prescription and under MD care. All these gadgets are not necessarily for affluent consumers.”

■ “I believe this should be for those patients that need this not for the general consumer. I(t) would open up the company for lawsuits.”

■ “The doctor makes a lot of sense. This is something that doesn’t need to be so easily available but also accessible.”

■ “Knowing more info about the product as well as market info has made me change my mind. I would still have reservations about the other risks previously mentioned as well as the health insurance issues.”

■ “If they release it to the public, then people would misuse it and not understand what some things are and maybe it might start some controversy with the product’s effectiveness.”

A sample of the reasoning the NU group shared for changing their answers included responses such as:

■ “This made me reconsider. Perhaps more needs to be known about how to get Heath Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) approved. But also wonder if this is any different than people doing genealogy tests that also link medical information.”

■ “Risk management requirements on personal data need to be demonstrated they are under control.”

■ “Concerns about the end result use of the tests and lack of privacy.”

■ “Privacy concerns are relevant and need to be explored further.”

Participants who changed their yes/no answer in the post-nudge vote appeared to give weight to the information provided in the nudge. The implication is that when participants were provided additional information framed as a wise reasoning nudge, they reconsidered their initial decision and incorporated the new information into their decision-making process. This further implies participants can be nudged to reflect on their decision-making process, thus employing wise reasoning strategies in their decision, which ultimately may lead to better decision-making.

A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relation between wise reasoning strategies considered by each group. The relation between groups was significant for considering uncertainty (e.g., intended usage vs. actual usage)

The results indicate that receiving a wise reasoning nudge may have had an impact on a participant’s decision-making for considering uncertainty (see Table 3). The NP group was the most likely to consider uncertainty of usage based on the doctor’s perspective on how the product could be misused in the consumer market rather than a product for the medical market. The control group was the least likely to consider uncertainty, and roughly one-fourth of the control group reported they did not see the relevance of considering future uncertainty.

| I did consider this | I did not consider this, but I wish I had | I did not consider this, and don’t see the relevance | ||

| Uncertainty (e.g., intended usage vs. actual usage) | Control | 53.10% (77) | 22.10% (32) | 24.80% (36) |

| NP | 70.00% (90) | 18.00% (23) | 11.70% (15) | |

| NU | 64.40% (94) | 19.90% (29) | 15.80% (23) | |

| Model Chi-Square | 11.040* | |||

| Model df | 4 | |||

*= p

The number of respondents in each category are in parentheses.

The nudge to consider the physician’s perspective decreased the consideration of personal interest in the product compared to both the control group and the NU group (see Table 4). Those in the NP group with the nudge from the physician were more likely to report they did not see the relevance of considering their own personal interest in the product post-decision, compared to three-fourths of the control and NU groups who did consider their personal interest in the Smart Toilet. This finding supports previous research that self-distancing from a problem promotes wiser reasoning (Grossmann and Kross, 2014; Kross and Grossmann, 2012).

| I did consider this | I did not consider this, but I wish I had | I did not consider this, and don’t see the relevance | ||

| Personal interest in product (e.g., I would want one) | Control | 74.50% (108) | 6.90% (10) | 18.60% (27) |

| NP | 58.60% (75) | 14.10% (18) | 27.30% (35) | |

| NU | 73.30% (107) | 9.60% (14) | 17.10% (25) | |

| Model Chi-Square | 10.464* | |||

| Model df | 4 | |||

*= p

The number of respondents in each category are in parentheses.

The strongest significant difference in the wise reasoning strategies considered was for the strategy “ethical considerations”. The nudge for uncertainty group (NU) who received additional information from an attorney to consider long-term implications and risks in how the product could be used in the consumer market were more likely to report considering ethics and far less likely to report not seeing the relevance of considering ethics in decision-making (see Table 5). The nudge from the attorney providing warning and context about future uncertainty and how HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) regulations could be violated appears to have influenced the NU group’s consideration of ethics. By comparison, a third of the control group reported they wished they had considered ethics in their decision-making process. The wise reasoning strategy read “ethical considerations (e.g., biomedical information shared on app, financial gain and risks)”, which may have alerted the control group to risks they had not considered when making their decision. This finding may support previous research on activating wisdom-related knowledge. That is, better knowledge exists within the individuals’ repertoire but is not readily accessible in the moment (Staudinger and Baltes, 1996; Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019).

| I did consider this | I did not consider this, but I wish I had | I did not consider this, and don’t see the relevance | ||

| Ethical considerations (e.g., biomedical information shared on app, financial gain and risks) | Control | 57.90% (84) | 31.00% (45) | 11.00% (16) |

| NP | 58.60% (75) | 19.50% (25) | 21.90% (28) | |

| NU | 74.70% (109) | 17.80% (26) | 7.50% (11) | |

| Model Chi-Square | 21.911*** | |||

| Model df | 4 | |||

***= p

The number of respondents in each category are in parentheses.

Finally, the control group and NU group were more likely to consider the financial benefits of being first to market compared to the NP group (see Table 6). The physician’s alert for the NP group may have led them to be less likely to consider feeling rushed to get to market for the financial benefits of being first to market. The physician’s wise reasoning nudge for the NP group may have caused that group to weigh the risks and benefits of being first to market with new technology compared to the control and NU group. These findings suggest providing a new perspective (the physician’s concerns) may have contributed to the “economy of the common good” rather than “money over man” decision-making (Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019, p. 277).

| I did consider this | I did not consider this, but I wish I had | I did not consider this, and don’t see the relevance | ||

| Financial benefits of being first to market | Control | 76.60% (111) | 13.80% (20) | 9.70% (14) |

| NP | 63.30% (81) | 17.20% (22) | 19.50% (25) | |

| NU | 76.00% (111) | 7.50% (11) | 16.40% (24) | |

| Model Chi-Square | 12.040* | |||

| Model df | 4 | |||

*= p

The number of respondents in each category are in parentheses.

This study also investigated the impact of wise reasoning nudges on participants’ confidence levels in decision-making, measuring the differences in participants’ perspectives on their CIQ, CITP, and HWD after receiving a wise reasoning nudge. The authors hypothesized that participants who received a nudge would demonstrate varying mean scores in confidence measures compared to the control group across the dimensions of perceived decision quality, thought process and wisdom in decision-making.

CIQ. A one-way ANOVA was conducted for the dependent variables, with each ANOVA evaluated at an alpha level of .05. Bonferroni and Games-Howell were conducted as post-hoc tests to compare different combinations of the treatment groups. There was a significant difference between the control group, NP group, and NU group for CIQ F(2416) = 5.86, p = 0.003. Subsequent Bonferroni and Games-Howell posthoc tests confirmed that the control group scored significantly higher than the NU group (p

| Total (419) | Control (145) | Nudge Perspective (128) | Nudge Uncertainty (146) | |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | p | |

| Confidence in quality of decision | 4.97 | 0.99 | 5.17 | 0.89 | 4.95 | 1.04 | 4.78 | 1.01 | 5.86 | 0.003** |

| Confidence in thought process | 5.06 | 0.97 | 5.19 | 0.94 | 5.03 | 0.98 | 4.97 | 0.97 | 2.14 | 0.119 |

| How wise of a decision | 4.99 | 0.97 | 5.14 | 0.89 | 4.99 | 0.99 | 4.84 | 1.02 | 3.56 | 0.029* |

NOTE: *= p

CITP. There was not a significant difference between the control group, NP group, and NU group for CITP F(2,416) = 2.14, p = 0.119. The control group, NP, and NU group did not differ significantly in how confident they were in their thought process when making a decision.

HWD. There was a significant difference between the control group, NP group, and NU group for HWD F(2,416) = 3.56, p = 0.029. Subsequent Bonferroni and Games-Howell posthoc tests confirmed that the control group scored significantly higher than the NU group (p

The ANOVA test revealed there were significant differences in the dependent variables CIQ and HWD between the control, NP, and NU groups. Directionally, it appears to reveal receiving a wise reasoning nudge decreases one’s confidence in quality of the decision and decreases how wise of a decision one feels they have made. This was significant for the NU group that received the nudge probing to consider future uncertainty and ethical risks. This implies individuals may associate their confidence in decision-making with how wise of a decision they felt they made. Overall, the wise reasoning nudge that provided information about future uncertainty from an attorney had a stronger effect than the wise reasoning nudge that provided a perspective from a physician. However, both nudges decreased participants’ CIQ and HWD mean scores. These nudges may address what Kahneman (2011) describes as “excessive overconfidence” (p. 14) and the natural inclination to ignore uncertainty and underestimate the role of chance in the future. The nudge for uncertainty may have decreased the decision risk of WYSIATI (what you see is all there is) (Kahneman, 2011).

Independent sample t-tests were conducted for differences in CIQ, CITP, and HWD means scores by gender. Male participants (180) (Mean (M) = 5.11, Standard Deviation (SD) = 0.925) demonstrated higher confidence in the quality of their decision-making than female participants (232) (M = 4.85, SD = 1.03) a significant difference for a one-tailed t-test t(410) = 2.58, p = 0.005, and a significant difference for a two-tailed t-test t(410) = 2.58, p = 0.010. There was not a significant difference between male participants (M = 5.13, SD = 0.918) and female participants (M = 5.00, SD = 0.993) for the confidence in thought progress reported for a two-tailed t-test t(410) = 1.397, p = 0.163. For how wise of a decision they felt they made, male participants (M = 5.08, SD = 0.942) reported higher mean scores than female participants (M = 4.90, SD = 0.982), with a significant difference for a one-tailed t-test t(410) = 1.85, p = 0.033, but not a significant difference for a two-tailed t-test t(410) = 1.85, p = 0.066.

The results on gender differences indicated that men overall reported higher CIQ and HWD compared to females. This implies men start the decision-making process more confident in quality and wise reasoning abilities than women. While this research study was not designed to study the differences between male and female decision-making processes, it supports the gender confidence gap (Guillén et al, 2018; Vajapey et al, 2020) in the literature showing that men tend to demonstrate more confidence in their decisions than women.

A total of 56 (out of 274 total) participants changed their decision after receiving either the NP or NU nudge. Mean scores were compared for the nudge group participants who changed their answer (56) and nudge group participants who did not change their answer (218) for the dependent variables CIQ, CITP, and HWD.

A Mann-Whitney U test was conducted to evaluate if those who received a nudge and changed their answer differed in their mean scores for CIQ, CITP, and HWD. The results of the tests indicate those who changed their post yes/no answer had lower mean scores for CIQ Mann-Whitney U = 4595.0, p

| Measure | M | SD | Mann-Whitney U | p | |

| Did not change answer (218) | CIQ | 4.97 | 0.952 | 4595.0 | 0.003 |

| CITP | 5.06 | 0.953 | 4942.5 | 0.020 | |

| HWD | 4.99 | 0.941 | 4998.0 | 0.028 | |

| Did change answer (56) | CIQ | 4.45** | 1.190 | 4595.0 | 0.003 |

| CITP | 4.73* | 1.018 | 4942.5 | 0.020 | |

| HWD | 4.59* | 1.187 | 4998.0 | 0.028 |

NOTE: *= p

The results indicate that participants who received a nudge and changed their pre-decision for the business problem overall report lower confidence in the quality of their decision, lower confidence in their thought process, and lower perception of how wise of a decision they report they made. Not only did the nudges decrease participants’ confidence in quality and wisdom of their decision, but those who changed their answer after the nudge were even less confident in their decision. Since reflection is considered one of the foundational traits of wisdom (Ardelt, 2003; Glück and Bluck, 2013; Grossmann et al, 2021), our findings indicate those who changed their answer may have reflected on their initial response, thus the different answers.

The purpose of this experimental study was to test nudges for wise reasoning strategies against an ill-structured business problem. The fictitious problem did not have a right or wrong answer, and it included complicated risks and benefits. The authors imagined cases such as DNA testing, stem cell research, and the opioid crisis where the benefits to society need to be weighed against the risks when the future use is uncertain, and the future is almost always uncertain. Company financial gain and rapid consumer adoption may be the first step to determining a go-to-market business strategy, but just because a company can fill a market desire, should it? We argue that long-term perspective-taking and consideration of uncertainty should be a part of decision-making. Our study demonstrated that once participants realized the potential long-term implications of the business problem, a significant number of participants changed their decisions, with a concomitant decrease in their confidence in their decision-making process.

This study tested a fictitious biomedical product for the consumer market with the potential to cost-effectively provide consumers a useful health feedback product based on urine samples. A high percentage of reasons in the open-ended comments in the pre-test for why they voted “yes” were related to personal interest and how consumers would benefit from the product. Looking at open-ended response reasons from the entire sample in the pre-vote prior to the nudges, the few who voted “no” initially (15%) reported reasons related to privacy, invasive nature, and potential for misuse. While this study used open-ended responses as a strategy to encourage reflection and reasoning, the thematic analysis of the responses was beyond the scope of this paper.

The results of this study found that providing wise reasoning nudges, both from the perspective of a physician warning about the risk of putting medical information in consumers’ control for interpretation (i.e., the perspective-taking nudge) and an attorney’s warning to consider long-term implications and risks of a how this product could be misused (i.e., the uncertainty nudge), appear to have caused reflection in participants’ reasoning strategies. Both nudge groups reported lower confidence in the quality of their decision and how wise of a decision they felt they made after the second decision. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that reflection and reconsideration can lead to decreased confidence due to increased awareness of the complexities and uncertainties involved in the decision (Kahneman, 2011). This decrease in confidence among participants who changed their decisions highlights the impact of nudges in promoting deeper reflection and consideration of multiple perspectives. Despite the lower scores for confidence and wise decisions, they were more likely to report using wise reasoning strategies, such as considering future uncertainty and ethics, and less likely to consider their own personal interest and financial benefits of being first to market.

While this study provides valuable insights into the impact of wise reasoning nudges on decision-making processes, there are several limitations to consider. Firstly, the inability to control how long participants spent evaluating the business problem was a limitation. The average time spent taking the survey indicated no significant differences (control group M = 8.28 minutes, SD = 1034.4; NP group M = 10.2 minutes, SD = 652.9; NU group 18.98 minutes, SD = 5040.3), although directionally the NU appeared to have spent longer taking the survey, the differences were not significant. Furthermore, we did not have context around participants’ decision-making authority at their place of employment. One can also argue the reason they changed their decision is due to the set-up in which both nudges came from a position of expertise and authority, a physician and an attorney, respectively. Lastly, because we did not include an existing wisdom assessment, we relied on participants’ self-reported perception of their wise-reasoning abilities. Future research should consider including a situational wise-reasoning assessment (SWIS) (Brienza et al, 2018), and future studies could use more delineated nudge construction for participants’ consideration.

An additional limitation of the study design is the lack of a control group that received irrelevant new information. This raises the question of whether the reflection and subsequent changes in decision-making were triggered solely by the act of reading more information or by the specific content of the nudges. To rule out this potential confound, future studies should include a second control group that receives irrelevant information (e.g., details about the location of the ICTC, the size of the toilet, or color options). Research in the heuristics and biases literature has shown that even useless information can influence human decision-making (Tversky et al, 1982). When processing information, cognitive biases such as: too much information, not enough meaning, needing to decide quickly, and what is pertinent to be remembered can all influence the way information is processed and lead one to favor some information over other information (Behimehr and Jamali, 2020). Including such a control would help to isolate the effect of the nudge content from the mere act of processing additional information.

While our study aimed to assess the impact of wise reasoning strategies on decision-making, we recognize that the use of a hypothetical scenario and a yes/no voting method presents certain limitations. Specifically, the study does not establish a definitive truth for what constitutes better decision-making. The hypothetical nature of the scenario means that we cannot measure the real-world success of the decisions made by participants, nor can we determine whether changing one’s mind leads to better outcomes. We hypothesized that wise reasoning strategies would enhance decision-making by encouraging participants to incorporate new information and reflect more deeply on the decision at hand. However, this study obviously cannot measure the actual success of the decisions or provide a quantitative assessment of decision quality beyond the self-reported confidence and perceived wise reasoning.

Future research should also consider more delineated nudge construction and explore the mechanisms through which nudges operate in decision-making contexts. By addressing these limitations, subsequent studies can provide a more comprehensive understanding of how to effectively promote wise reasoning and improve decision-making processes.

Understanding and defining wisdom dates to earliest recorded history to discern the essence of truth, meaning, and human flourishing (Shoup et al, 2022). One of the earliest documented masterpieces on wisdom literature comes from The Instruction of Amenemope (ca. 1200-1075 B.C.E), where a scribe writes on the themes of modesty, self-control, seeking truth, and not falling prey to pride (Ray, 1995). The scribe’s wisdom teachings from over 3000 years ago are still relevant, with a message of “humility without complacency and ambition without snobbery” (Ray, 1995, p. 11). Wise leaders balance intellectual competence and confidence, short- and long-term decisions, and seek the perspective of others with a common good outcome as the goal. Although wisdom has been a topic of reflection and aspiration for millennia, we are in a particular moment that demands a new kind of wisdom, one that can grapple with broad swaths of humanity, leverage a long vision to the future, and engage a capacity to conceptualize a common good that encompasses the entire world and its descendants.

The world needs more wisdom, and we trust it is available to everyone. Business leaders especially need to adopt wise-reasoning practices when making decisions that impact the common good. In a post-truth world overwhelmed with misinformation and disinformation and technology moving faster than regulating entities can keep up, business leaders have the power to do the right thing. Yet, doing the right thing is not always clear. As our findings pointed out, using wise reasoning strategies, including intellectual humility, perspective-taking, and short- and long-term planning under uncertainty may help leaders make a more balanced decision that considers the common good. Proverbs 28:2 says: “When the country is in chaos, everybody has a plan to fix it—But it takes a leader of real understanding to straighten things out.” As argued in this paper, the world has an urgent need for wise leaders who will transcend self-serving interests for the common good of all stakeholders, including the future generations of humankind.

Data Availability: The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Materials Availability: Materials used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

KC and KH: Both authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, as well as to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Complex Business Case Presented

Smart Toilets

Smart Toilets is a new company that has built the first wellness toilet. The Smart Toilet uses bio-medical health-tracking technology that analyzes a person’s urine by scanning for various nutrition, health, and disease markers. One simply uses the toilet, and the Smart Toilet runs urinalysis diagnostics to check overall health. The Smart Toilet is connected to a smartphone app for users to review their urinalysis results. The app also sends alerts and tips to help people improve their diets and lifestyle for better health.

Urinalysis tests include:

Additional Facts:

A decision needs to be made to move forward with introducing the Smart Toilet at the ICTC. The risk of waiting is the company is running out of seed funding and needs to start generating sales to pay for current operations. There is also recent patent activity revealing of other companies exploring a similar product. You sit on the board of directors and need to vote yes or no to move forward with introducing Smart Toilet at the ICTC.

Nudge Perspective

A doctor also sits on the board of directors with you. She supports the technology specifically because of the benefit for monitoring patients with ongoing medical conditions within the comfort of their own home. She prefers this is introduced as an in-home medical device with doctor’s orders and not a general consumer product. The financial models supported this as a potential channel of market entry, the market supports a higher per-product-cost and subscription rate, but health insurance companies have not approved this as a medical device yet.

She fears the Smart Toilet will become wellness gadget for the affluent, and not the product she had in mind when agreeing to serve on this board. She feels strongly that marketing this as a consumer product will dilute the integrity of Smart Toilet’s bio-medical health tracking. Furthermore, she fears providing urinalysis results with consumers who do not how know to read them is opening the company up for future lawsuits.

Nudge Uncertainty

Prior to the board meeting you explained this opportunity and dilemma to a trusted friend of yours who is an attorney who specializes in corporate law. She asks if the board of directors has considered long-term implications if the results of Smart Toilet’s urinalysis is used against people.

She advises you to think of worst-case scenarios of confidential medical lab results getting into the wrong hands which she anticipates is likely to happen without the same regulations medical labs have around HIPAA.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.