1 Department of Food Hygiene and Technology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Harran University, 63000 Şanlıurfa, Türkiye

2 Department of Genetics, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Harran University, 63000 Şanlıurfa, Türkiye

3 Department of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, 17100 Çanakkale, Türkiye

Abstract

Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) is the causative agent of paratuberculosis, also known as Johne’s disease, in ruminants and is associated with Crohn’s disease in humans. Due to its resistance to pasteurization, MAP can be transmitted through contaminated milk and milk products, posing a food safety risk.

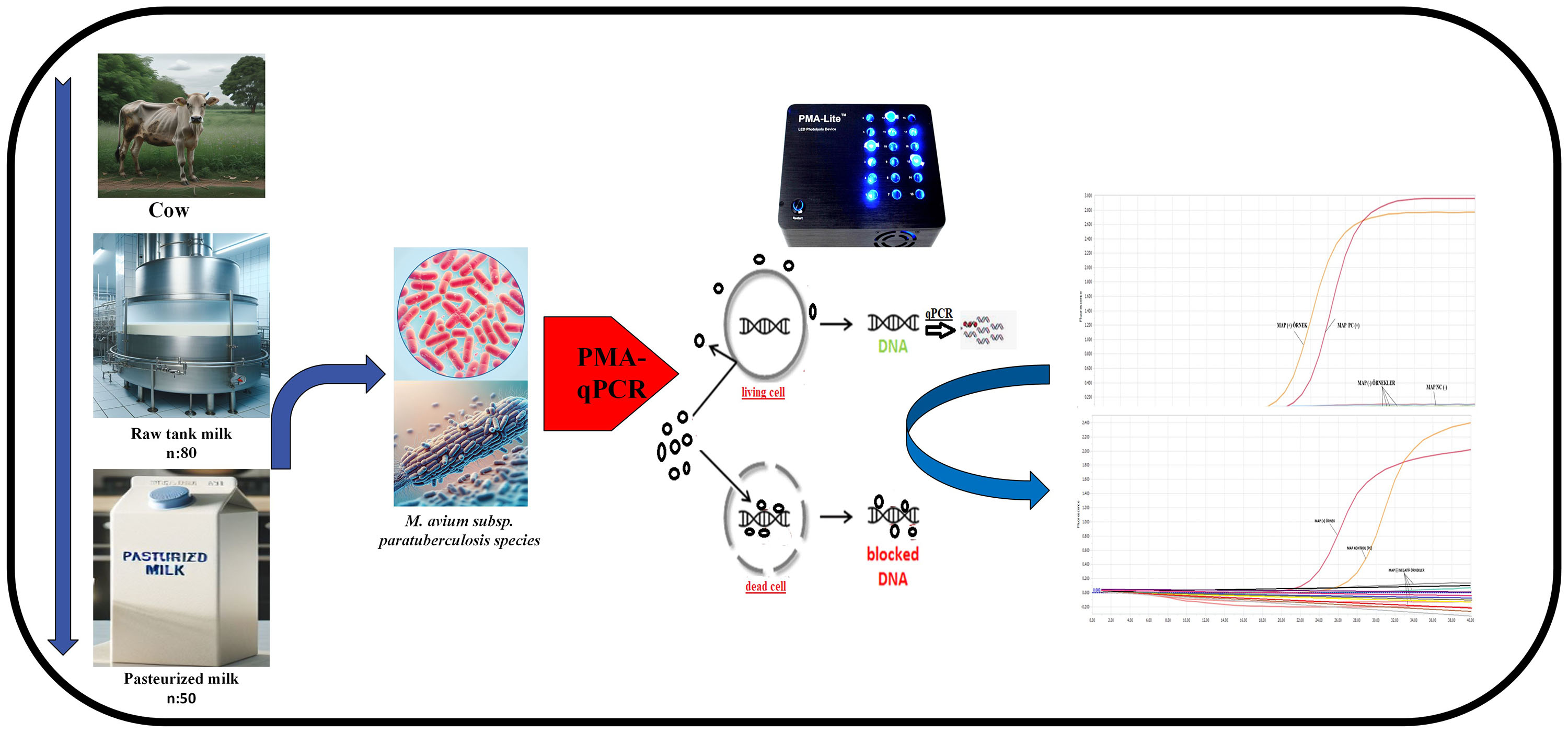

This study aimed to detect and assess the viability of MAP in retail pasteurized and raw tank cow milk in Şanlıurfa, Turkey, using the propidium monoazide (PMA)-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) method. A total of 130 milk samples (50 pasteurized and 80 raw tank cow milk) were collected from local shops and dairies. Samples were tested for the presence of MAP, and viable bacteria were further quantified using PMA-qPCR.

MAP was not detected in any of the pasteurized milk samples. One (1.42%) raw milk sample tested positive for MAP, but further PMA-qPCR analysis indicated that the bacteria were not viable.

The PMA-qPCR method can effectively determine the viability of MAP in milk. Raw bulk milk was found to be at risk of MAP contamination; thus, it is recommended that raw milk be consumed with caution, ensuring proper hygiene and storage, and ideally, should not be consumed raw due to potential public health risks.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis

- MAP

- PMA-qPCR

- propidium monoazide

- milk

The Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) is a slow-growing, acid-fast bacterium that is the causative agent of Johne’s disease, a chronic granulomatous enteritis primarily affecting the intestines of ruminants, especially cattle [1]. Meanwhile, Johne’s disease causes significant health problems in dairy cows, including weight loss, reduced milk production, and diarrhoea, and in some cases death [2]. Moreover, the economic impact of the disease on the dairy industry is significant, with costs associated with animal care, culling, and lost productivity [3]. However, in addition to its veterinary importance, MAP has attracted attention for its potential zoonotic impact. Indeed, MAP has been implicated in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease, a chronic inflammatory condition of the human gastrointestinal tract. Although research on the direct link between MAP and Crohn’s disease remains inconclusive, the presence of MAP in milk has raised concerns about the risk of human exposure through dairy consumption [4, 5].

Since MAP is shed in the milk and faeces of infected animals, dairy products, particularly raw milk, represent a potential route of transmission. As dairy products are widely consumed globally, the detection of MAP in milk is critical for assessing food safety and public health risks [6]. This bacterium can be present in both clinical and subclinical infections in dairy cows, complicating the detection of these infections. While the clinical signs of Johne’s disease are often visible, subclinical infections in which the animals show no outward signs or symptoms can still result in the shedding of MAP into milk products, representing a silent but significant source of contamination [7].

Additionally, the detection of MAP in milk is challenging due to its slow growth and low numbers. Traditional methods, such as bacterial culturing, remain the gold standard for identifying viable MAP; however, these methods are time-consuming and labor-intensive, requiring weeks to months for results. Therefore, molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have recently been developed to detect MAP DNA more quickly and with greater sensitivity [8]. Furthermore, PCR methods, including quantitative PCR (qPCR), offer significant advantages over culturing, as these methods promote the detection of MAP in a matter of hours or days [9]. However, these methods only detect the presence of MAP DNA and cannot distinguish between viable and dead cells, limiting their ability to assess the potential risk of infection.

To overcome this limitation, the use of propidium monoazide (PMA) in combination with qPCR has gained prominence. PMA is a dye that selectively binds to DNA from dead cells, preventing amplification during the PCR process [10]. Thus, by applying PMA before DNA extraction, it is possible to exclude DNA from non-viable cells, allowing a more accurate assessment of the presence of live MAP bacteria in milk. This approach, known as propidium monoazide quantitative PCR (PMA-qPCR), has proven to be a valuable tool for determining the viability of MAP in various food matrices, including milk [11].

Several studies worldwide have reported the detection of MAP in both raw and pasteurized milk, although these results vary considerably in terms of prevalence rates [12, 13, 14]. Some studies have found MAP in raw milk at relatively low rates [6], while others have reported contamination in pasteurized milk [15], despite pasteurization being intended to kill harmful bacteria. The presence of MAP in pasteurized milk can be attributed to various factors, including inadequate pasteurization, contamination during post-pasteurization handling, or the persistence of MAP in certain milk components [16].

This study specifically aimed to determine not only the prevalence but also the viability of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (MAP) in both raw and pasteurized milk samples collected from Şanlıurfa, a region in southeastern Turkey, where data on MAP contamination are currently limited. A total of 130 milk samples (80 raw and 50 pasteurized) were analysed using PMA-qPCR, a technique capable of distinguishing between DNA from viable and non-viable cells. The primary innovation of this study lies in its application of PMA-qPCR as a non-culture-based viability assay for MAP detection in milk. This approach remains underutilized in the context of Turkish dairy surveillance. Hence, by implementing this technique, this study not only provides region-specific epidemiological data but also introduces a more accurate and rapid method for assessing public health risks related to MAP in dairy products. These findings are expected to contribute to the development of more targeted control strategies and inform national food safety protocols aimed at mitigating potential zoonotic transmission and exposure to MAP through dairy consumption.

A total of 130 full-fat milk samples were collected from cow dairies and local markets in Şanlıurfa, Turkey, between September 2023 and January 2024. Of these, 50 samples were from pasteurized milk and 80 samples were from raw milk. Pasteurized milk samples were purchased directly from the supplier in their original packaging. When collecting pasteurized milk, the date of pasteurization was considered, and samples with a short remaining shelf-life were excluded from the study. All pasteurized milk samples were produced using the same processing conditions (72 °C for 15 seconds) in accordance with standard high-temperature short-time (HTST) pasteurization procedures. Raw tank milk samples were collected in 50 mL sterile Falcon tubes after thoroughly mixing the milk in the tank. For the raw milk samples, only milk freshly collected on the same day and stored in refrigerated tanks was selected. The milk samples were transported under cold chain conditions to the Food Hygiene and Technology Laboratory of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Harran University, where immediate analysis was performed. During the study, the milk samples were kept at 4 °C. Before sampling, the packaging or Falcon tubes were thoroughly mixed to ensure uniformity.

The first step was to extract the DNA from the milk samples. Real-time PCR was then performed to identify positive samples. Positive samples were treated with PMA before DNA extraction, followed by qPCR to determine the quantity and viability of MAP bacteria.

Before starting the study, 400 µL of the milk samples were bead-beaten and whipped for 5 minutes to extract DNA from MAP cells [17]. Then, DNA was extracted from the milk samples using the QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The method was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with some modifications [18]. Before implementing the kit protocol, samples were incubated at 95 °C in a dry heat block for 45 minutes. Tubes were vortexed every five minutes during incubation. After incubation, the tubes were placed in a horizontal vortex and mixed at maximum speed for 30 minutes. The remaining steps were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The extracted DNA was stored at –20 °C until used for qPCR analysis.

The SybrGreen Master Mix (10 µL), forward primer (500 nM, 1 µL), reverse primer (500 nM, 1 µL), DNA (5 µL), and ddH2O (3 µL) mixture was prepared according to the commercial FastStart Essential SybrGreen Master Mix kit (Roche, Hilden, Germany) [19]. After the isolated DNA samples and Mix Real Time PCR mixes were combined on appropriate 96-well plates, denaturation was performed at 95 °C for 6 minutes, amplification was performed at 95 °C for 10 seconds, 58 °C for 30 seconds, 72 °C for 1 second and 40 cycles and 40 °C for 10 seconds and loaded onto the Real Time PCR device (LightCycler96, Roche, Hilden, Germany).

The primers (forward: 5′–ATCTGGACAATGACGGTTACGGAG–3′ and reverse: 5′–ATCGCTGCGCGTCGTCGTT–3′) were used to amplify the IS900 gene region in MAP (NCBI: XCJ76353.1). To determine the viability of MAP in positive samples, the samples were first treated with PMA prior to DNA extraction. After the extraction process, qPCR was performed. The cycle threshold (Ct) values were calculated for each positive sample, including the positive control M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis ATCC 1698.

PMA (Biotium, USA), purchased in lyophilized form, was dissolved in 20% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) to prepare a 20 mM stock solution. Then, 400 µL of the sample and 1 µL of the 20 mM PMA stock solution were added to transparent 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes and vortexed. After incubation at room temperature in the dark for 5 min, the sample was exposed to 800 W halogen light for 3 min using a PMA-Lite device (PT-HISA, China) [20, 21]. The treated samples were then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 5000 g. Afterward, the samples were stored at –80 °C until DNA extraction was performed.

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the positivity, negativity, and viability status of the milk samples. The results are expressed as percentages. A t-test was used to compare pasteurized and raw tank milk samples. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Out of the 130 milk samples analyzed, MAP DNA was detected in only one raw tank milk sample, representing 1.25% (1/80) of the raw milk samples and 0.77% (1/130) of all milk samples tested. None of the pasteurized milk samples (0/50) were positive for MAP DNA, indicating a 0% detection rate in the processed milk samples. The test result details are summarized in Table 1.

| Samples | Number of samples | Positive | Negative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw tank milk | 80 | 1 (1.42%) | 79 (98.58%) |

| Retail pasteurized milk | 50 | - | 50 (100%) |

| Total | 130 | 1 (0.77%) | 129 (99.23%) |

Notably, the presence of non-viable MAP was confirmed by PMA-qPCR in the only MAP-positive raw milk sample. After PMA treatment and qPCR amplification, the Ct value did not show significant amplification, indicating that the detected MAP cells were non-viable. This result is consistent with the principle of PMA treatment, which inhibits amplification of DNA from dead cells, confirming that although MAP DNA was present, the bacterium was no longer infectious or alive.

The amplification curve of the positive sample showed a typically delayed Ct value before PMA treatment. However, no amplification curve was observed after PMA treatment, further supporting the conclusion that the bacterium was not viable. Figs. 1,2 show the raw PCR result and the PMA-qPCR analysis of the positive raw milk sample, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Samples and controls in the real-time PCR analysis of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Propidium monoazide-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PMA-qPCR) results of the positive raw milk sample for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (MAP).

Statistical analysis showed no significant difference (p

Paratuberculosis (Johne’s disease) causes chronic, degenerative, granulomatous enteritis, primarily in the intestines of infected ruminants. Both clinical and subclinical cases of paratuberculosis in dairy cows contribute to foodborne contamination through their milk and faeces [22]. In the present study, 0.77% (1/130) of all milk samples and 1.25% (1/80) of raw milk samples tested positive for MAP, confirming that milk sold in Turkey, particularly raw milk, may be contaminated with this bacterium. Similar studies conducted in other regions of Turkey have also reported contamination of milk with MAP. Öztürk Kalın et al. [23] investigated MAP in 200 raw milk samples sold on the street in Kayseri using direct microscopy, culture, and serological methods and found MAP in only one sample (0.5%). Çetinkaya et al. [24] reported that 25 out of 500 milk samples tested positive for MAP using a PCR method combined with the IS900 sequence, corresponding to a 5% prevalence. Gümüşsoy et al. [25] detected MAP DNA in 13.61% of milk samples from 147 cows with chronic diarrhoea in Kayseri using PCR. Studies from other countries also report MAP contamination in milk and milk products. Gerrard et al. [14] reported that 10.3% of 368 pasteurized milk samples sold at retail outlets in the UK tested positive for MAP using Phage -PCR. Albuquerque et al. [12] found MAP DNA in 16.5% of 121 dairy milk samples in Pernambuco, Brazil, using conventional PCR and in 28.1% using qPCR from herds considered MAP-positive. Ahmed et al. [1] reported that 6% of 50 raw milk samples from Mosul, Iraq, from cows considered weak and unresponsive to antibiotic treatment, were positive for MAP using direct amplification PCR. Cirone et al. [13] found that 1.56% of 384 retail milk and milk products in Argentina were MAP positive using IS900-related PCR. When evaluating the results of previous studies, it is clear that milk from cows, both in Turkey and worldwide, has tested positive for MAP, albeit at low rates. Therefore, the results of this study are consistent with previous reports in the literature. The detection of a MAP-positive milk sample in Şanlıurfa, Turkey, may reflect the regional prevalence of the pathogen. In support of these findings, a study by Çelik and Yaşar Tel [26] reported that 21 (4.51%) of 465 serum samples from healthy cattle in Şanlıurfa were positive for MAP antibodies, and a further 16 (3.4%) were classified as suspicious. These findings suggest a potential risk from the presence of MAP in milk and milk products in this region.

Given the health risks associated with MAP, in particular its potential to cause Crohn’s disease in humans, a need exists for rapid and sensitive tests to detect the presence and viability of this bacterium in milk. Bacterial culturing remains the gold standard (reference method) for confirming the viability of MAP in a sample. However, MAP can be detected much more quickly and with approximately 10 times greater sensitivity using qPCR [12]. Nonetheless, qPCR is not sufficient to determine whether the bacterium is alive. Thus, PMA-qPCR is used to overcome this limitation and determine whether the MAP bacterium in a sample is alive or dead. PMA treatment is used to block DNA from dead cells through binding to the DNA of non-viable cells with damaged membranes, rendering the DNA insoluble and leading to its loss during DNA extraction [27]. Ricchi et al. [28] experimentally prepared milk mixtures containing different percentages of live and dead cells and analyzed them using PMA-qPCR, confirming that this method can be used to detect the viability of MAP in milk directly. Hanifian [29] reported in their study on the ripening process of Lighvan cheese that culturing and PMA-qPCR results were parallel in determining the viability of MAP. In addition, Hanifian [29] emphasized that PMA-qPCR could be a reliable approach for monitoring changes in MAP load, as culture detection of MAP is considered the reference method. In the present study, the viability of the bacteria in a positive milk sample was quickly and reliably analysed using the PMA-qPCR method, and it was found that the bacteria were not viable. Therefore, the presence and viability of MAP in dairy products can indeed be determined using this method.

The use of high-temperature short-time (HTST) treatment at 72 °C for 15 seconds is well known for eliminating pathogenic bacteria in milk, reducing spoilage organisms, and extending the shelf life of pasteurized milk. However, significant evidence exists suggesting that HTST pasteurization does not consistently produce heat-treated milk free from viable MAP cells [14, 30, 31, 32]. However, MAP was not detected in pasteurized milk in the present study. This may be explained by the limited number of commercial companies selling pasteurized milk in Şanlıurfa, as well as the absence of infected cows on the farms from which the analyzed pasteurized milk samples were obtained. Additionally, the small volume of milk used for the analysis may have affected the results. Indeed, it has been emphasized that MAP is not evenly distributed in food matrices such as milk and dairy products, and it has been suggested that larger sample volumes are necessary for reliable MAP detection [13, 22]. The varying sensitivities of the methods used to detect MAP in milk samples may also contribute to discrepancies between study findings. It has been noted that commercially pasteurized milk produced from hygienically obtained raw milk using HTST (72 °C, 15 s) may contain low concentrations of viable MAP, and that these concentrations are often below the detection limits of traditional cultural methods [33]. For example, Albuquerque et al. [12] reported that MAP DNA was detected in 20 samples (16.5%) using conventional PCR and in 34 samples (28.1%) using qPCR, attributing the difference to the varying sensitivities of the methods. Although the absence of MAP in the current study may imply the effectiveness of pasteurization, this finding should be interpreted with caution. Moreover, the efficacy of pasteurization in eliminating MAP remains a topic of controversy. Several studies have demonstrated that MAP can survive standard pasteurization processes, particularly when present in high concentrations or in clumps that may shield the bacteria from heat exposure [22]. Moreover, it has been suggested that sublethal heat treatment may not completely inactivate MAP; however, this treatment may instead render MAP viable but non-culturable (VBNC), potentially complicating detection and raising concerns about residual infectivity [34]. Therefore, the lack of MAP detection in this study does not conclusively confirm the complete inactivation of MAP by pasteurization, and further research involving larger sample volumes, more sensitive detection methods, and assessment of bacterial viability is warranted.

In parallel with the results of the present study, previous studies have reported the detection of MAP in raw milk at varying levels [1, 12, 17, 23, 35]. Furthermore, studies have shown that MAP in raw milk samples was viable [6, 14, 22, 36]. However, in the current study, when the viability of the positive samples was analysed using PMA-qPCR, the bacterium was found to be non-viable. The low bacterial concentration and potential competitive interactions with other microbiota present in milk may explain the absence of live MAP in raw milk samples. Previous studies have shown that antimicrobial compounds produced by lactic acid bacteria, such as nisin, can alter the intracellular environment of MAP and reduce its viability [37, 38]. Additionally, residual decontamination agents or stress-inducing conditions during milk collection and storage may further impact bacterial survival [39]. Moreover, the genetic differences between MAP strains detected in various studies, as well as the varying sensitivities of the methods used, may also influence the detection of viable MAP in raw milk. It has been reported that there are significant differences in the survival rates of MAP strains from sheep and goats [29]. In addition, the sensitivity of the method used has been found to influence the detection of MAP [12]. The PMA-PCR method used in this study has different detection limits depending on the foodborne pathogen, milk matrix, and the level of human manipulation [40].

This study highlights the presence of MAP in raw milk, with 1.25% (1/80) of raw milk samples testing positive. The use of PMA-qPCR enabled the differentiation between viable and non-viable MAP cells, a significant advantage over conventional PCR methods that detect DNA from both live and dead cells. Although the MAP bacteria identified in the positive sample were confirmed to be non-viable, these results suggest that raw milk, even if it contains non-viable MAP, still poses a potential risk of contamination. These results also underscore the importance of implementing enhanced hygiene practices in milk production and storage to minimize the risk of contamination. Veterinarians in this region must consider the presence of MAP when developing control strategies for Johne’s disease. Implementing such measures will not only help control the disease in livestock but will also protect public health by reducing the risk of MAP transmission through milk.

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

MEA: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. SKA: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; visualization. AY: Formal analysis; writing—original draft. SA: Formal analysis; writing—original draft. HD: Conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; visualization. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We express our gratitude to the Scientific Research Unit of Harran University.

This study was supported by the Scientific Research Unit of Harran University under project number 23017.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

In this study, Microsoft Copilot AI tools were used to create the graphical abstract. All visuals were originally created for this work and do not infringe on any third-party copyrights. The AI tools were used for support purposes only, and all content (text and visuals) remains the sole responsibility of the author(s).

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.