1 Department of Midwifery, Assosa University, Assosa, Ethiopia

2 Department of Public Health, Bako Health Center, Oromia, Ethiopia

3 Department of Nursing, Assosa University, Assosa, Ethiopia

4 Department of Public Health, Ambo University, Oromia, Ethiopia

Abstract

Food safety practices cannot be overstated since these practices directly impact public health by preventing food-borne illnesses. Despite global advancements, gaps persist in local food safety practices, particularly in under-resourced regions where knowledge, training, and infrastructure may be limited. This study aimed to assess food safety practices and determinant factors among food handlers in food establishments in Bako town in 2023.

A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted from August 19 to September 16, 2023, involving 325 randomly selected food handlers who participated in face-to-face interviews using pre-tested structured questionnaires and observational checklists. The collected data were coded and entered into Epi Data version 3.1, then exported to SPSS version 25 for further analysis.

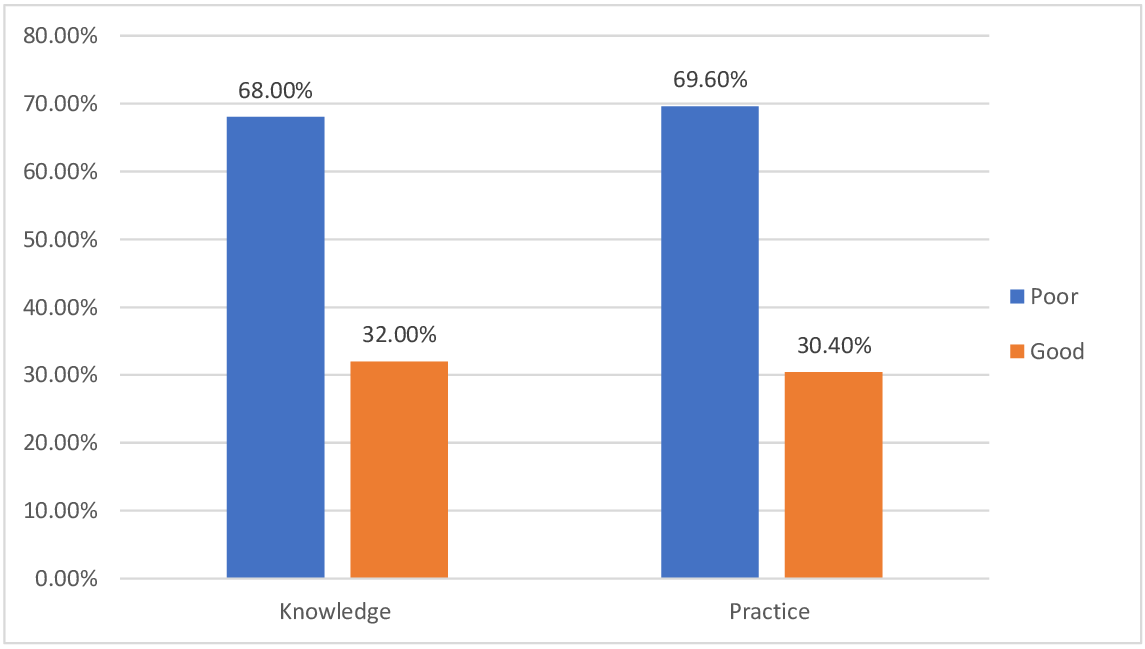

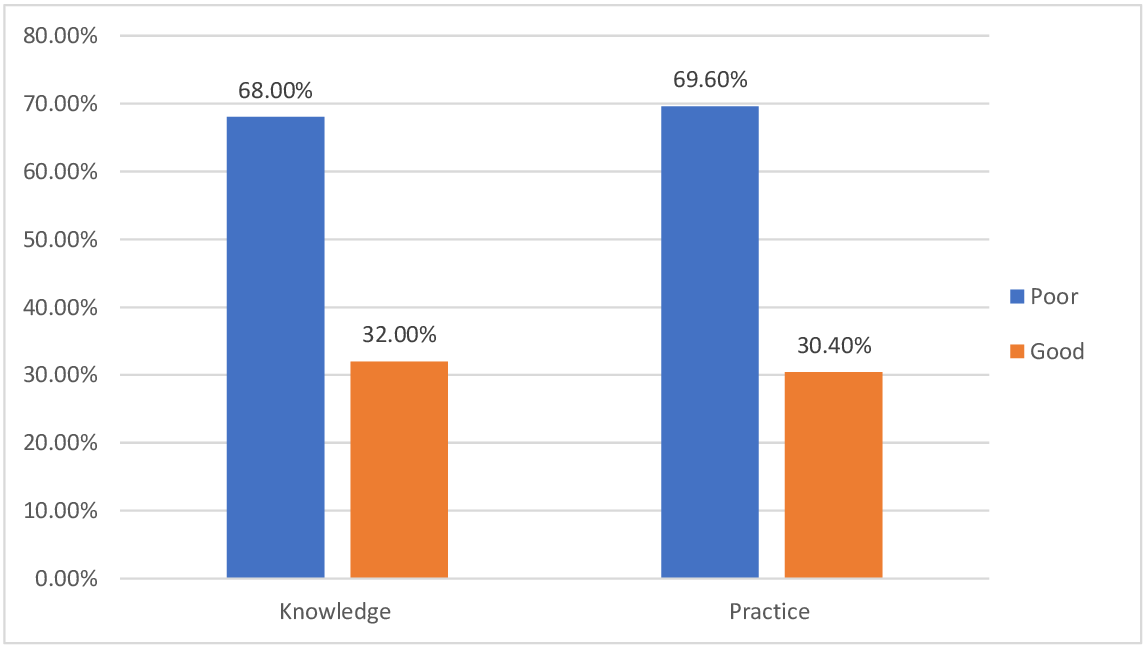

A total of 319 food handlers participated, yielding a response rate of 98.2%. The findings indicated that only 30.4% of food handlers demonstrated good food handling practices. Key factors associated with improved practices included a strong knowledge of food safety, prior training in food safety protocols, and a positive attitude toward food safety.

This study highlights the critical need to enhance the knowledge of food handlers by providing on food handling protocols and fostering positive attitudes among food handlers toward food safety practices. Recommendations include implementing targeted interventions within food safety practices by focusing on education, training, and attitude development via collaboration with local authorities and different stakeholders in the town.

Keywords

- food handling practices

- food handlers

- food safety

- food establishments

- hygiene practices

- sanitation practices

Maintaining proper food safety standards throughout the stages of production, processing, and preparation is essential to prevent contamination and minimize the risk of foodborne diseases, which pose a significant threat to public health. In Ethiopia, the definition of food encompasses all substances intended for human consumption. Prioritizing food safety is a crucial step towards enhancing overall human well-being and quality of life [1, 2, 3].

The rapid expansion of restaurants globally, fueled by factors such as urbanization, industrialization, tourism, and globalization, has heightened food safety risks throughout the food supply chain, necessitating increased vigilance from all parties involved. Foodborne illnesses represent a significant threat to public health worldwide, particularly in developing countries, where a substantial proportion of diarrheal diseases, up to 70%, are attributed to contaminated food. This contamination often arises from inadequate hygiene practices, insufficient regulatory standards, ineffective oversight, and low levels of education among food workers [4, 5, 6, 7, 8].

Ensuring food safety and hygiene is crucial for protecting the health of consumers. Organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Union (EU) stress the importance of reevaluating community strategies related to food and water safety based on scientific evidence to combat foodborne illnesses. These diseases impact millions each year in the United States and disproportionately affect developing countries, often resulting from inadequate hygiene practices during the preparation, handling, and storage of food [9, 10, 11, 12].

Food-safety-related illnesses and deaths remain a significant threat to public health in Sub-Saharan Africa [13]. In Ethiopia, the government recognizes that communicable diseases like diarrhea and parasitic infections, which are largely attributed to inadequate food safety practices, are major contributors to hospital admissions and outpatient visits. Additionally, numerous reported cases of foodborne viral diseases in the catering industry have been traced back to infected food handlers [14]. The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted the WHO to emphasize the importance of respiratory hygiene, physical distancing, handwashing, and personal protective equipment (PPE) as key preventive measures [14].

The WHO advocates for the “Five Keys to Safer Food” as essential measures to prevent foodborne illnesses. These key practices include ensuring cleanliness, keeping raw and cooked foods separate, cooking food thoroughly, maintaining safe temperatures for food storage, and using safe water and quality raw materials [15, 16]. Although food preparation techniques can differ depending on the type of food and the environment, following these five fundamental principles is essential for maintaining food safety. This is particularly important in facilities that cater to large groups of customers, as even a small mistake could affect a significant number of individuals [17].

Ethiopia’s food systems are under pressure due to resource limitations, urban expansion, and a growing population. Research indicates that only 20% to 70% of food establishments implement safe handling practices, which include maintaining cleanliness in the environment, ensuring food handlers are clean and properly trained, providing sanitary facilities, disposing of waste correctly, obtaining legal licenses, and practicing good personal hygiene [18, 19]. Additional crucial factors that influence food safety include household cleanliness, access to sanitation facilities, procedures for food handling, preparation, and storage, as well as the condition of kitchen equipment and the skills and habits of food service workers [20].

To effectively safeguard human health, food safety regulations must be grounded in scientific evidence; however, strategies that work well in affluent countries may not be suitable for developing nations with varied food systems and regulatory frameworks. In Ethiopia, dining at hotels, restaurants, and local eateries is prevalent, where large volumes of food are prepared, handled, and served rapidly, creating contamination risks that are frequently associated with food handlers [21]. Although many studies have been conducted, researchers in Ethiopia have not yet explored the factors contributing to the inconsistent implementation of safe food-handling practices within the commercial sector. There is a need for more flexible models to effectively ensure food safety in environments that are high-risk, costly, and have weak enforcement of regulations [22].

Maintaining food safety is critical in reducing mortality and morbidity associated with foodborne diseases. However, improper food handling practices can still lead to severe consequences, including loss of life. This study aimed to assess food safety practices and associated factors among food handlers in food establishments in Bako Town, West Shawa Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia.

Bako Tibe Woreda, situated 251 kilometers from Finfinnee, the capital of Ethiopia, in the West Shoa zone of Oromia, was the focus of this study conducted from August 19 to September 16, 2023. The Woreda has a population of 196,418, evenly split between males and females, distributed across 32 Kebeles (28 rural and 4 urban), with 40,920 households and 28,703 children under the age of five. The healthcare infrastructure includes one district hospital, five health centers, and 28 health posts. According to data from the Bako Trading Office, 78 food and beverage establishments were identified in Bako town. An institution-based cross-sectional study design was utilized, with the source population comprising all food handlers employed in the food and drinking establishments of Bako Town. The study population consisted of selected handlers who met the inclusion criteria, excluding those providing temporary services, street food vendors, and handlers of canned or packaged foods.

The sample size for this study was calculated using a single population proportion formula, incorporating a 5% margin of error and a 72.6% prevalence of poor food hygiene practices identified in a prior study conducted in Addis Ababa [18]. This calculation yielded a sample size of 306. Furthermore, sample size estimates were made for two significant associated factors: inadequate knowledge (288 participants) and insufficient food hygiene training (309 participants), based on findings from earlier research. The larger sample size of 309 was chosen, and after factoring in a 5% non-response rate, the final sample size was adjusted to 325. In the study area, there are 86 licensed food establishments. Consisting of 71 restaurants and 15 hotels. For this study, 63 restaurants and 12 hotels were chosen. The estimated total food handlers in 63 restaurants was 315, and 72 food handlers were in 15 hotels. Then, based on the proportional allocation, 265 were selected from the restaurants and 60 from hotels, resulting in a total sample size of 325.

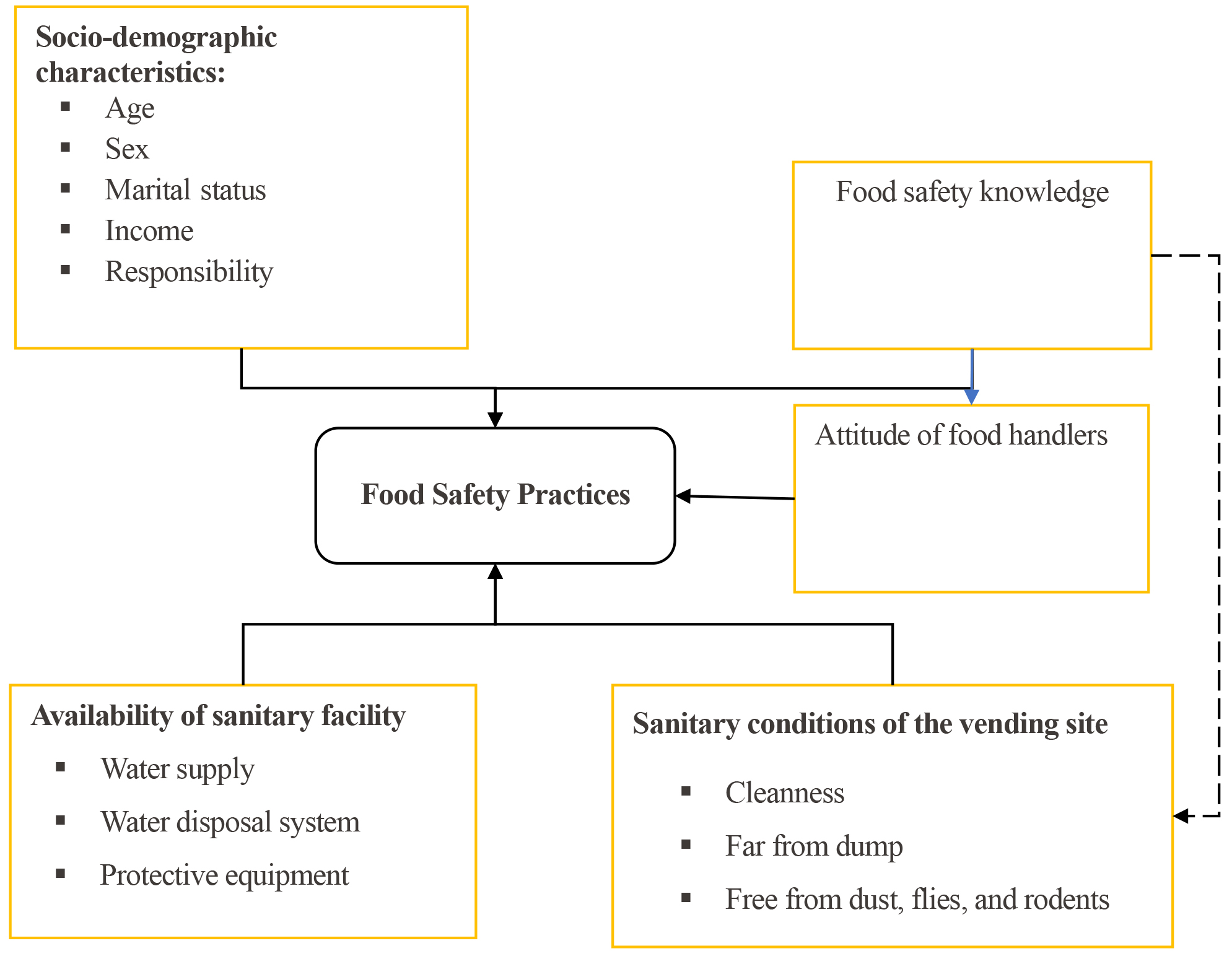

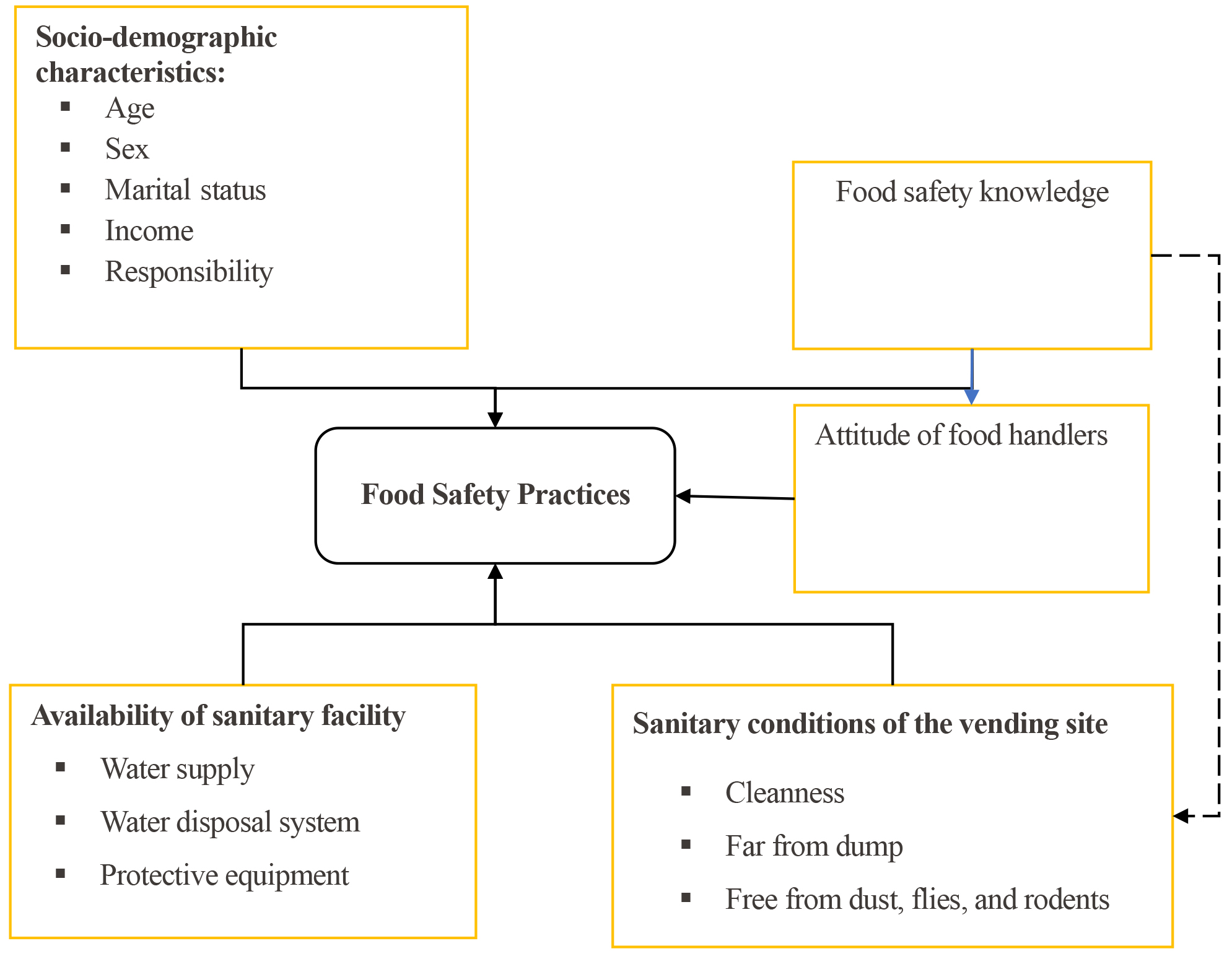

In this study, the dependent variable was food safety practices. The independent variables encompassed sociodemographic factors, including age, gender, marital status, income, and responsibility. Additionally, the study examined the handlers’ knowledge of food safety practices and the Attitude of food handlers on food safety practices. Availability of sanitary facilities like water supply, disposal system, and protective equipment. Sanitary conditions of the vending site, like cleanness, distance from dump sites, and free from dust, flies, and rodents.

A food handler is defined as an individual employed in a restaurant or bar who manages food or interacts with any utensils or equipment that may potentially come into contact with food [23]. Food handling practices were evaluated through a set of 15 yes/no questions along with a 16-item observational checklist. Participants who scored below 70% were classified as having poor food-handling practices, while those who achieved a score of 70% or above were deemed to have good practices [24]. Food handling knowledge was assessed using a set of 25 questions. Participants who scored 70% or higher were categorized as having good knowledge, while those who scored below 70% were considered to have poor knowledge [24]. Attitudes regarding food handling were measured using eight Likert scale questions that were converted into a dichotomous format. Participants who scored 80% or higher were classified as having positive attitudes, while those with scores below 80% were regarded as having negative attitudes [24].

A pre-tested structured questionnaire was administered through in-person interviews in Ejaji town. The questionnaire was constructed using insights derived from previous research [18, 23, 25, 26]. The data collection tools included a questionnaire and an observation checklist designed to gather information on food handlers’ practices and the cleanliness of food establishments. The questionnaire was translated between Afaan Oromo and English to ensure consistency and was administered by five bachelor’s degree (BSc) holders in nursing or food science who had prior experience in data collection. These individuals were supervised by two BSc health officers after undergoing two days of intensive training. The questionnaire comprised three sections. The first section evaluated the sociodemographic characteristics of food handlers. Food handling practices were assessed through 15 questions and 16 observational checklists, totaling 31 items, with participants scoring 70% or higher classified as having good practices. Knowledge was evaluated using 25 questions, where a score of 70% or above indicated good knowledge. Lastly, attitudes were assessed with 8 questions, with scores of 80% or higher considered indicative of a positive attitude.

The questionnaire was initially modified from existing published articles [6, 19, 27, 28], and subsequently translated into Afan Oromo, followed by a back-translation into English to ensure accuracy. Data collectors and supervisors participated in a one-day training session focused on the tools and procedures for data collection. A week before the actual data collection, the questionnaire was pre-tested with 5% of the study participants. The supervisor was responsible for overseeing the entire data collection process and ensuring the completeness of the collected information.

Initially, the collected data were reviewed, coded, and entered into Epi-data version 3.1, Manufacturer: The EpiData Association (Odense, Denmark) after which it was exported to SPSS version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) for analysis. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the variables in terms of frequencies and proportions. A binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify independent variables related to food safety practices. In the bivariate analysis using this model, variables with a p-value of less than 0.25 were selected as candidates for the final model. For the multivariable analysis, all candidate variables were included in a multivariable binary logistic regression model to assess the effects of independent variables on the outcome variable. The finding of Hosmer and Lemeshow’s test for model fitness is insignificant (the p-value of the test was 0.140), indicating the model fits the data. Variance inflation factor (VIF) was done, and the presence of multicollinearity was detected. Independent variables were considered statistically significant determinants of the outcome variable if they had a p-value of 0.05, a 95% confidence interval (CI), and an adjusted odds ratio (AOR). The findings were ultimately presented in both text and tables.

A total of 319 food handlers took part in this study, yielding a response rate of 98.2%. The largest age group among the participants was 21 to 30 years, comprising 144 individuals (45.1%). Additionally, more than half of the participants, 185 (58%), were female. Among the total respondents, 172 (53.9%) were married. However, only 56 participants (17.6%) reported having received training in food handling practices (see Table 1).

| Variables | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Age | 28 | 8.8 | |

| 21–30 | 144 | 45.1 | |

| 31–40 | 105 | 32.9 | |

| 42 | 13.2 | ||

| Sex | Male | 134 | 42 |

| Female | 185 | 58 | |

| Marital status | Single | 115 | 36.1 |

| Married | 172 | 53.9 | |

| Divorced | 32 | 10 | |

| Responsibility | Main chief | 105 | 32.9 |

| Assistant chief | 79 | 24.8 | |

| Waiters | 135 | 42.3 | |

| Monthly income | 50 | 15.7 | |

| 7.63–15.26 USD | 90 | 28.2 | |

| 15.27–22.90 USD | 31 | 9.7 | |

| 148 | 46.4 | ||

| Training | Yes | 56 | 17.6 |

| No | 263 | 82.4 | |

| Knowledge | Good | 102 | 32 |

| Poor | 217 | 68 | |

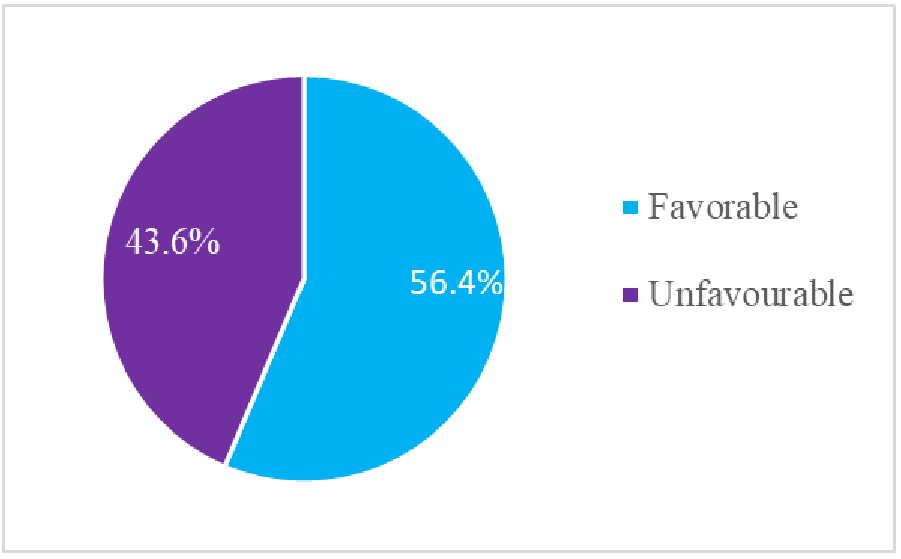

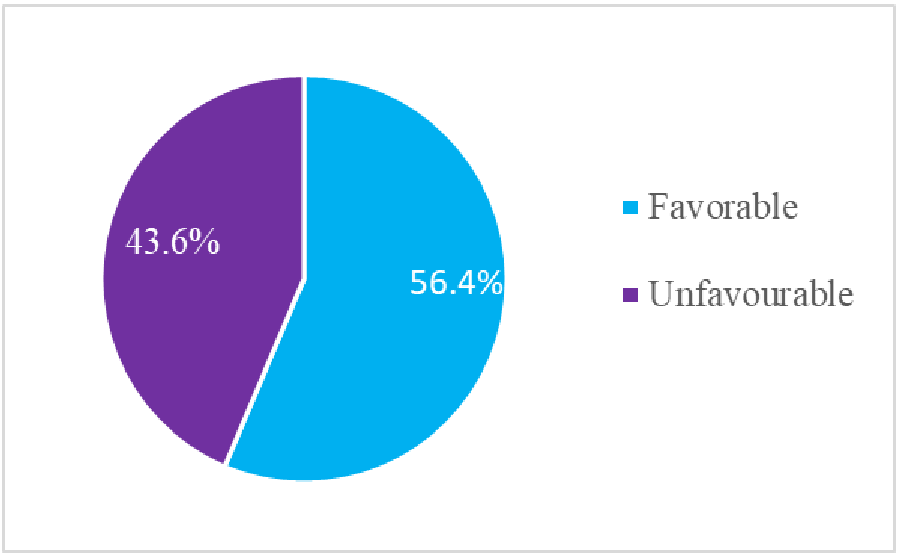

| Attitude | Favorable | 180 | 56.4 |

| Unfavorable | 139 | 43.6 |

The questionnaire designed to evaluate food handling practices revealed that only 16.6% of food handlers wash their hands after handling unwrapped raw foods, and just 54 participants (16.9%) disinfect their cutting boards after each use (see Table 2). According to the observational checklist, 247 food handlers (77.4%) were found to wear jewelry while preparing food, 219 (68.7%) used the same cutting board for both raw and cooked foods without cleaning it, and only 79 individuals (24.8%) reported using soap or detergents when washing their hands (see Table 3).

| Questions for Food Handling Practice | |||

| Questions | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Wash hands after touching unwrapped raw foods | Yes | 53 | 16.6 |

| No | 266 | 83.4 | |

| Wash your hands before touching cooked Foods | Yes | 56 | 17.6 |

| No | 263 | 82.4 | |

| Use separate utensils for raw and cooked foods | Yes | 47 | 14.7 |

| No | 272 | 85.3 | |

| Thaw frozen foods at room temperature | Yes | 35 | 11 |

| No | 284 | 89 | |

| Check the expiry dates of all products | Yes | 172 | 53 |

| No | 147 | 47 | |

| Use a thermometer to check the temperature | Yes | 18 | 5.6 |

| No | 301 | 94.4 | |

| Use gloves when serving unwrapped food | Yes | 25 | 7.8 |

| No | 294 | 92.2 | |

| Wash your hands before using gloves | Yes | 25 | 7.8 |

| No | 25 | 92.2 | |

| Wash your hands after using gloves | Yes | 2 | 0.6 |

| No | 317 | 99.4 | |

| Medical checkup | Yes | 1 | 0.3 |

| No | 318 | 99.7 | |

| Get sick leave for any sickness | Yes | 1 | 0.3 |

| No | 318 | 99.7 | |

| Wear a hair restraint when | Yes | 59 | 18.5 |

| No | 260 | 81.5 | |

| Wear jewelry when serving food | Yes | 306 | 95.9 |

| No | 13 | 4.1 | |

| Disinfect cutting boards after each use | Yes | 54 | 16.9 |

| No | 265 | 83.1 | |

| Sanitize utensils after washing them | Yes | 45 | 14.1 |

| No | 274 | 85.9 | |

| Observation of Food hygiene practice of food handlers | |||

| Questions | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Having long nails | Yes | 298 | 6.6 |

| No | 21 | 93.4 | |

| Wearing clean uniforms | Yes | 234 | 73.4 |

| No | 85 | 26.6 | |

| Wearing hair restraints | Yes | 226 | 70.8 |

| No | 93 | 29.2 | |

| Having a jeweler while handling foods | Yes | 247 | 77.4 |

| No | 72 | 22.6 | |

| Sneezing/coughing over uncovered food | Yes | 290 | 90.9 |

| No | 29 | 9.1 | |

| Washing hands after/before handling food | Yes | 207 | 64.9 |

| No | 112 | 35.1 | |

| Working while having any discharge | Yes | 283 | 88.7 |

| No | 36 | 11.3 | |

| Working while having cut or any skin problem | Yes | 26 | 8.2 |

| No | 293 | 91.8 | |

| The same board for raw & cooked food without cleaning | Yes | 219 | 68.7 |

| No | 100 | 31.3 | |

| Functional water supply for food handlers & customers | Yes | 216 | 67.7 |

| No | 103 | 32.3 | |

| Practice a compartment dishwashing system | Yes | 217 | 68 |

| No | 102 | 32 | |

| Separate dressing rooms available for food handlers | Yes | 221 | 69.3 |

| No | 98 | 30.7 | |

| Soap or detergents available for hand washing | Yes | 79 | 24.8 |

| No | 240 | 75.2 | |

| Food hygiene guidelines available for food handlers | Yes | 55 | 17.2 |

| No | 264 | 82.8 | |

| Availability of Insects/rodents | Yes | 235 | 73.7 |

| No | 84 | 26.3 | |

| Supervision by owner/supervisor | Yes | 226 | 70.8 |

| No | 93 | 29.2 | |

This study found that an estimated 32.0% of participants had a good knowledge of food safety practices, while 30.4% (95% CI = 25.4–35.8) exhibited good practices related to food safety (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, respectively). Furthermore, approximately 56.4% of the participants held a positive attitude toward food handling (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework of a study done on food safety practices and associated factors among food handlers in food establishments (Source: Adapted after reviewing different kinds of literature).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Knowledge and practice of study participants about food safety in Bako Town, Wes Shoa Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 319).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Attitude of study participants about food handling in Bako Town, Wes Shoa Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 319).

In the bivariable logistic regression analysis, six variables were identified as being associated with food handling practices, each with a p-value of less than 0.25. These variables included income, age, knowledge, attitude, participation in training, and responsibility. However, in the multivariable logistic regression, only three variables showed significant associations with food safety practices at the 0.05 significance level: knowledge (AOR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.25–3.40), participation in training (AOR = 3.08, 95% CI: 1.70–5.57), and attitudes toward food safety practices (AOR = 2.83, 95% CI: 1.68–4.77). Participants with good knowledge were found to be twice as likely to engage in good food safety practices compared to those with poor knowledge (AOR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.25–3.40). Additionally, those who had received training were four times more likely to practice good food safety than those who had not attended any training (AOR = 4.26, 95% CI: 2.10–8.63). Furthermore, participants with positive attitudes toward food safety were nearly three times more likely to exhibit good food handling practices compared to those with negative attitudes (AOR = 2.83, 95% CI: 1.68–4.77) (see Table 4). The multi-variable logistic regression analysis revealed that knowledge, training, and attitudes were the key factors significantly associated with food safety practices findings show that the need for targeted interventions focusing on enhancing knowledge, providing comprehensive training, and fostering positive attitudes to improve food safety practices and reduce public health risks associated with poor food safety practices.

| Variable | Categories | Food Safety Practice | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Good (%) | Poor (%) | |||||

| Monthly income | 29 (32.2) | 61 (67.8) | 0.66 (0.32, 1.34) | 0.71 (0.32, 1.56) | 0.392 | |

| 7.63–15.26 USD | 11 (35.5) | 20 (64.5) | 0.76 (0.30, 1.92) | 1.30 (0.41, 4.16) | 0.658 | |

| 15.27–22.90 USD | 36 (24.3) | 112 (75.7) | 0.44 (0.23, 0.87) | 0.58 (0.18, 1.87) | 0.364 | |

| 21 (42.0) | 29 (58.0) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Age | 7 (25.0) | 21 (75.0) | 1.07 (0.35, 3.24) | 2.00 (0.73, 5.23) | 0.180 | |

| 21–30 | 56 (38.9) | 88 (61.1) | 2.04 (0.93, 4.47) | 1.13 (0.37, 3.46) | 0.836 | |

| 31–40 | 24 (22.9) | 81 (77.1) | 0.95 (0.41, 2.20) | 1.07 (0.29, 3.94) | 0.921 | |

| 10 (23.8) | 32 (76.8) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Good knowledge | Good | 42 (41.2) | 60 (58.8) | 2.06 (1.25, 3.40) | 2.13 (1.21, 3.76) | 0.009* |

| Poor | 55 (25.3) | 162 (74.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Training | Yes | 29 (51.8) | 27 (48.2) | 3.08 (1.70, 5.57) | 4.26 (2.10, 8.63) | 0.000* |

| No | 68 (25.9) | 195 (74.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Attitude | Unfavorable | 26 (18.7) | 113 (81.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Favorable | 71 (39.4) | 109 (60.6) | 2.83 (1.68, 4.77) | 3.18 (1.79, 5.64) | 0.000* | |

| Responsibility | Assistant chief | 22 (27.2) | 59 (72.8) | 0.91 (0.48, 1.75) | 0.80 (0.36, 1.78) | 0.584 |

| Waiters | 49 (36.3) | 86 (63.7) | 1.53 (0.84, 2.79) | 1.34 (0.49, 3.69) | 0.571 | |

| Main chief | 26 (25.2) | 77 (74.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

Where: * Variables significantly associated in multivariable logistic regression with p-value

This study aimed to evaluate food safety practices and the factors associated with them among food handlers in food establishments located in Bako Town, West Shoa zone. The findings revealed that the prevalence of good food handling practices was 30.4% (95% CI = 25.4–35.8). This prevalence was low as compared to the finding of a study conducted in Ireland which was 67% [29] and Nigeria, where the good practice was 92.1% [30]. The reason for the observed discrepancy might be the difference in the socioeconomic status of study participants and the levels of hotels and restaurants. In addition, this observed prevalence is lower as compared to the previously conducted systematic review and meta-analysis in Ethiopia, which was 48.36% [31]. The difference in findings may be attributed to variations in the study participants. Additionally, this prevalence is lower than that reported in a study conducted in northwest Ethiopia, which found a prevalence of 40.1% [24]. The possible reason for the observed prevalence might be differences in the study area and the socio-economic status of the participants. In addition, this prevalence was lower compared to the study done in Woldia Town, which was 46.5% [29], Metu town 55.1% [32], Gondar City 49.0% [19], Fitche town 50.5% [26], and Debra Markos 54% [27]. The reason for the difference would be the difference in the study population, study area, and sampling technique.

It was found that participants with good knowledge were twice as likely to engage in good food safety practices compared to those with poor knowledge (AOR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.25–3.40). This result aligns with findings from studies conducted in Mettu, Ethiopia [32], Fitche town [26], Bole, Addis Ababa [18], and Debra Markos [27]. The possible reason for this higher food safety practice among those with good knowledge might be that good knowledge has a positive effect on attitude, which in turn could have improved the practice. Therefore, improving food safety knowledge for those who have poor practices could improve food safety in the study area. To improve food safety practices, mandatory training programs for food handlers, focusing on enhancing knowledge and practical skills. In addition, awareness creation should be necessary to foster positive attitudes towards food safety. This initiative can be supported by strengthening regulatory monitoring and engaging local stakeholders.

Participants who had received training were four times more likely to engage in good food safety practices compared to those who had not attended any training (AOR = 4.26, 95% CI: 2.10–8.63). This finding aligns with results from a study conducted in Debra Markos [27], Gondar City [19], Beshoftu town [6], and SNNPR, Ethiopia [28]. The possible justification for this could be better awareness, experience sharing from experts, and motivation or improved attitude during the training. Therefore, identifying skill gaps among study participants and providing necessary training could improve the food handling practice in the study area [33]. This improved food handling practice could reduce the burden of feco-orally transmitted and other communicable diseases.

Participants with positive attitudes toward food safety were nearly three times more likely to engage in good food handling practices compared to those with negative attitudes (AOR = 2.83, 95% CI: 1.68–4.77). This finding is consistent with results from a study conducted in Debra Markos [27], Bole, Addis Ababa [18], California [6], and Ethiopia [7].

The prevalence of good food safety practices among handlers was relatively low. The key determinants identified were good knowledge, participation in training, and positive attitudes. To address this issue, a multifaceted approach is necessary, including prioritizing educational and training programs to enhance knowledge, launching awareness campaigns emphasizing food safety principles, strengthening policies and regulations with regular monitoring, implementing incentive programs, and collaborating with stakeholders to develop targeted interventions. The municipality and health department should provide periodic training, awareness, and support to local establishments, as investing in handlers’ knowledge could help reduce feco-orally transmitted diseases, a leading cause of health facility visits. Future researchers should conduct additional studies to address limitations and expand insights.

AOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; FBDs, Food-Borne Diseases; PPE, Personal Protective Equipment; WHO, World Health Organization.

The data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

DT & TB conceptualization, and designed the study. DT & TB performed the research. ND and AT provided help and advice throughout the study. TB & DT analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All procedures were conducted according to applicable guidelines and regulations. An ethical clearance letter was obtained from our institution (approval number Ref.NO./Lakk.Ambo. RVU/4267/2015). Before data collection, all participants or their families/legal guardians were informed about the study’s purpose and their right to participate voluntarily, from all study participants verbal informed consent was obtained with ethical approval. Confidentiality was upheld throughout all phases of the research, ensuring that the names of study subjects and any personal identifiers were not used during data collection. The collected data were stored on a secure, password-protected computer.

We extend our gratitude to the study participants for their willingness to provide samples and necessary information, as well as for their cooperation throughout the data collection process.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.