1 Faculty of Sciences of Nature and Life, University of Mustapha Stambouli, 29000 Mascara, Algeria

2 Research Laboratory on Biological Systems and Geomatics (LRSBG), University Mustapha Stambouli, 29000 Mascara, Algeria

3 Faculty of Sciences of Nature and Life, Ziane Achour University of Djelfa, 17000 Djelfa, Algeria

4 Laboratory of Microbiology Applied to Agri-food, Biomedical and Environment (LAMAABE), Faculty of SNV/STU, University of Tlemcen, 13000 Tlemcen, Algeria

Abstract

This study evaluates the impact of dipping chicken legs in 0.4% Mentha spicata and Rosmarinus officinalis essential oil (EO) emulsions, warmed to the same temperature and for the same duration as the soft scalding process (53 ± 1 °C for 3 min), on the EO’s antimicrobial activity against spoilage bacteria to extend its shelf life. Samples were stored at 4 ± 1 °C under air packaging (AP) and vacuum packaging (VP).

Microbial analysis of Enterobacteriaceae, lactic acid bacteria (LAB), Pseudomonas spp., psychrotrophic bacteria, and H S2-producing bacteria, pH determination, and sensory evaluations of raw and cooked chicken legs were performed on days 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 16 for samples stored under AP and continued on days 20, 24, and 28 for samples stored under VP.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis revealed that carvone 25.36% and eucalyptol 52.09% were the main components in M. spicata and R. officinalis EO, respectively. Warming the EO emulsions increased their antibacterial effect. In addition, vacuum packaging and dipping chicken legs in a warmed emulsion of R. officinalis or M. spicata EO extended the shelf life by 15 and 19 days, respectively. However, under air, dipping chicken legs in both warmed EO emulsions extended the shelf life by 10 days. Furthermore, the sensory shelf lives of raw and cooked chicken legs under air and vacuum generally matched those determined by microbial analysis. M. spicata EO performed better under all conditions.

The use of warmed EO emulsions is considered an inexpensive and effective method of preserving raw and cooked chicken meat. However, the most effective combination for extending the shelf life of chicken legs is warmed M. spicata EO emulsion and vacuum packaging.

Keywords

- chicken legs

- shelf life

- soft scalding

- spoilage bacteria

- warmed emulsion

Meat and meat products have a relatively short shelf life due to their high water activity (aw) and nutrient richness, which create a favorable environment for microbial growth [1]. Producers face a challenge in establishing an appropriate shelf life for meat and poultry products. Shelf life, on the other hand, can be defined as the time it takes for a product to remain suitable for consumption while meeting safety, nutritional, regulatory, and sensory standards [2, 3]. Meat spoilage is defined as an alteration of physicochemical properties that exceeds the acceptable limit and is caused by microbial activity or metabolic processes [4].

Microbial growth is one of the major causes of quality deterioration in meat, so the level of microbial growth is closely related to sensory acceptability and serves as a spoilage indicator [5]. According to Fletcher et al. [6] (2018), meat is considered spoiled when undesirable changes in its sensory properties are detected. It is estimated that more than 20% of the meat produced worldwide is lost or wasted, primarily due to microbial spoilage. However, in the United States, it is estimated that 2 to 4% of processed meat is lost due to spoilage, with a total value of $83,127 million [7]. Another study found that in Canada, red meat accounted for 39.73% of total waste, while poultry waste was estimated to be around 42.74% [8]. Thus, poultry spoilage is an economic burden for both producers and consumers. The development of alternative strategies to extend the shelf life of meat products is a major focus of meat processing research.

Various combinations of modified atmosphere, vacuum packaging (VP), and essential oils (EO) have been used to control spoilage bacteria and increase the shelf life of meat and poultry products [3]. To extend the shelf life of chicken meat, previous research has used EO as emulsions at room temperature in conjunction with vacuum packaging, but in this study, a third combination is added: warming the EO emulsions to the same temperature used in the soft scalding process. This is the process of immersing the carcass in warm water at 53 °C for 3 minutes to effectively remove feathers [9]. It is commonly used because it causes little damage to the bird’s outer layer of skin.

The EO used in this study were derived from Rosmarinus officinalis and Mentha spicata, two aromatic plants grown worldwide for their unique aroma and commercial value. As a result, microbiological analysis, sensory evaluation of raw and cooked chicken legs under air and vacuum packaging, and the effect of warming the EO emulsions on the antimicrobial activity of the EO were used to determine the best combination treatment to extend the shelf life of chicken meat.

Fresh leaves of Rosmarinus officinalis and Mentha spicata were collected from Blida-Djelfa, Algeria (April-May 2023), botanically identified, dried in the dark, and subjected to essential oil extraction following the European Pharmacopoeia method [10]. The extracted essential oils were stored in airtight glass bottles at 4 °C. Their composition was analyzed at PTAPC-CRPC (Laghouat, Algeria) using the Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) QP2020 (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyot, Japan) with a fused Rxi®-5ms capillary column. The analysis involved split-mode injection (1:10), a temperature program from 50 °C to 310 °C, helium as the carrier gas, and electron ionization at 70 eV. EO components were identified by comparing their retention indices and mass spectra to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and Wiley libraries, as well as data from the literature [11].

R. officinalis and M. spicata EO emulsions were created by combining 0.4 mL of each EO with 100 mL of sterile distilled water and 0.2 mL of tween 80 (MERCK, Darmstadt, Germany). The solutions were emulsified separately with a mechanical homogenizer (850 Homogenizer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 4 minutes until the mixture became completely uniform. These emulsions, each containing 10 liters, were immediately used to immerse the chicken legs. The concentrations of EO were determined based on preliminary testing to ensure any negative sensory impacts on chicken meat while maintaining its desirable flavor.

One hundred eighty chicken legs were purchased from a local retail market and delivered to the laboratory in a refrigerated container. Chicken legs were divided into 2 batches according to storage conditions. Samples from the first batch were randomly divided into five groups (control group, group dipped in 0.4% M. spicata EO emulsion at room temperature MNA (M. spicata EO, Not warmed, Air-packed) or warmed to 53

The same preparation method was used for the second batch of samples, except that they were vacuum packed using a vacuum packaging machine (Aukey 75 kpa, Hamburg, Germany) instead of air packed, resulting in the following groups: MNV, MWV, RNV, and RWV. The thickness of the film was 90 µm. All trays were stored at 4

Microbial analyses were performed as described by Alessandroni et al. [12] (2022). Raw chicken meat (10 g) of each sample was aseptically mixed with 90 mL of peptone water (0.1% w/v) (CONDALAB, Madrid, Spain) in a sterile stomacher bag and homogenized using a stomacher at room temperature. Decimal dilutions were performed using the same diluents, and 0.1 mL of each appropriate dilution was poured into plates of selective medium: Pseudomonas spp. growth at 25 °C for 48 hours on Cetrimid, Fucidin, and Cephaloridin (CFC) agar (MERCK, Darmstadt, Germany). Psychrotrophic bacteria were investigated on plat count agar after incubation at 7 °C for 10 days. For H2S-producing bacteria were determined on peptone iron agar (MERCK, Darmstadt, Germany) supplemented after autoclaving L-cysteine [13, 14]. These formed black colonies as a result of the formation of ferrous sulfide.

To determine LAB count and Enterobacteriaceae, 1 mL of the appropriate dilution was plated on Man, Rogosa, Sharpe (MRS) Agar (MERCK, Darmstadt, Germany) and Violet Red Bile Glucose (VRBG) Agar (CONDALAB, Madrid, Spain), respectively, and overlaid with 5–10 mL of the same molten medium. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C for Enterobacteriaceae and stored under anaerobic conditions for 3 days at 25 °C for LAB. Microbiological data are expressed as log10 CFU·g–1. The PH of the homogenate from each sample was determined using a PH meter (OHAUS, ST3100, Parsippany, NJ, USA).

A panel of 6–7 members of Food Hygiene and Quality, Zian Achour University, Algeria, competent in meat evaluation, was invited to evaluate raw and cooked chicken legs. Each group of samples was labeled at random with a three-digit code number and presented in a randomized order. Sensory analysis of raw chicken meat was carried out according to Kreyenschmidt et al. [15] (2010), with a slight modification. Odor (O), color (C) and texture (T) were evaluated using a scoring system ranging from 1 to 4, with 1 corresponding to the highest quality score and 2.5 corresponding to the cut-off score for unacceptability. The weighted Sensory Index (SI) was calculated using the following equation:

Sensory evaluation of cooked chicken meat was assessed according to Patsias et al. [16] (2006). Chicken legs from each group were cooked in a microwave oven (Condor CMW-M2307B, Bordj Bou Arréridj, Algeria) at 700 W for 6 min. An acceptability scale ranging from 5 to 1 was used to assess acceptability as a composite of odor, texture and taste, with 5 corresponding to the most-liked sample and 1 to the least-liked chicken sample. A score of 3 was considered the lower limit of acceptability.

All microbiological experiments were performed in duplicate for each sample. Before analyses, data were checked for normality and homogeneity of variance using the Shapiro-Wilk and Levene tests, respectively. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s post-hoc multiple interval test was performed to evaluate the significant differences (p

The chemical compositions of the EO compounds were determined using GC-MS analysis. Table 1 only shows compounds with a retention rate of more than 0.3%. It can be noted that M. spicata and R. officinalis had 35 and 18 compounds, respectively, that account for 91.82 and 98.39% of their total EO. The main constituents detected in rosemary essential oil were eucalyptol (52.09%), camphor (11.71%),

| No. | Compounds | Rosmarinus officinalis | Mentha spicata | ||

| R. time | Area% | R. time | Area% | ||

| 1 | 8.826 | 10.31 | 8.830 | 1.16 | |

| 2 | Camphene | 9.389 | 3.25 | 9.387 | tr |

| 3 | Sabinene | - | - | 10.427 | 1.10 |

| 4 | 10.512 | 2.62 | 10.555 | 1.81 | |

| 5 | Myrcene | 11.143 | 1.07 | 11.178 | 1.36 |

| 6 | 3-Octanol | - | - | 11.416 | 0.94 |

| 7 | δ-3-Carene | 11.945 | 0.14 | - | - |

| 8 | 12.229 | 0.43 | 12.266 | 0.62 | |

| 9 | o-Cymene | 12.565 | 1.77 | 12.600 | tr |

| 10 | Limonene | - | - | 13.103 | 23.93 |

| 11 | Eucalyptol | 12.896 | 52.09 | - | - |

| 12 | (Z)- | - | - | 13.272 | 0.64 |

| 13 | 14.105 | 0.46 | 14.167 | 0.90 | |

| 14 | Sabinene hydrate | - | - | 14.554 | 1.55 |

| 15 | Linalool | 15.968 | 0.76 | 16.032 | tr |

| 16 | Camphor | 17.985 | 11.71 | - | - |

| 17 | Borneol | 18.991 | 4.26 | 19.125 | 1.31 |

| 18 | Terpinen-4-ol | 19.536 | 0.85 | 19.645 | 1.58 |

| 19 | 20.165 | 3.96 | 20.270 | 0.32 | |

| 20 | Trans-Dihydrocarvone | - | - | 20.576 | 4.20 |

| 21 | Pulegone | - | - | 22.452 | 0.95 |

| 22 | Carvone | 22.594 | tr | 23.168 | 25.36 |

| 23 | Trans-Carvone oxide | - | - | 23.569 | 2.05 |

| 24 | Carvacrol | 24.812 | 0.64 | 25.073 | tr |

| 25 | Dihydrocarvyl acetate | - | - | 26.554 | 0.58 |

| 26 | - | - | 29.080 | 4.00 | |

| 27 | - | - | 29.339 | 1.69 | |

| 28 | (Z) Jasmone | - | - | 29.569 | 0.77 |

| 29 | Carvacrylacetate | 30.350 | 3.60 | 30.571 | 5.09 |

| 30 | 31.750 | 0.47 | 31.861 | 0.43 | |

| 31 | Cis-Muurola-4(15),5-diene | - | - | 32.257 | 1.12 |

| 32 | Germacrene D | - | - | 33.082 | 3.96 |

| 33 | Bicyclogermacrene | - | - | 33.648 | 1.28 |

| 34 | Trans- | - | - | 33.982 | 0.48 |

| 35 | - | - | 34.663 | 0.76 | |

| 36 | Spathulenol | - | - | 36.791 | 0.51 |

| 37 | Caryophyllene oxide | - | - | 37.003 | 0.51 |

| 38 | epi- | - | - | 39.185 | 0.86 |

| Total | 98.39 | 91.82 | |||

R. time, Retention time; tr, Trace; (-), Not detected.

These bioactive compounds, found in essential oils, exhibit various biological activities, such as antimicrobial effects against spoilage and pathogenic bacteria, antioxidant properties that delay lipid oxidation, and consequently, preservative effects, especially in the case of eucalyptol, borneol, camphor, and carvone [19].

Assessments of microbial growth under air (Table 2) and vacuum packaging (Table 3) were carried out by measuring Enterobacteriaceae, LAB, Pseudomonas spp., psychrotrophic bacteria, and H2S-producing bacteria. The growth of spoilage bacteria causes chicken meat deterioration and mainly contributes to a reduction in its shelf life, especially in the control group. At the beginning of storage, the initial count of Enterobacteriaceae, LAB, and H2S-producing bacteria were approximately 3 log10 CFU·g–1, indicating the acceptable microbial quality of chicken meat [20]. However, the initial counts of Pseudomonas spp. and psychrotrophic bacteria were approximately 4 log10 CFU·g–1. During chilled storage at 4

| D0 | D3 | D6 | D9 | D12 | D16 | ||

| Enterobacteriaceae | Control CA | 3.44 | 5.24 | 6.20 | Na | Na | Na |

| MNA | 3.28 | 5.00 | 5.70 | 5.89 | 6.28 | Na | |

| MWA | 3.21 | 4.08 | 4.80 | 5.19 | 5.31 | 5.99 | |

| RNA | 3.34 | 5.04 | 5.47 | 6.09 | Na | Na | |

| RWA | 3.31 | 4.52 | 5.31 | 5.45 | 5.66 | 6.18 | |

| Psychrotrophic bacteria | CA | 4.62 | 5.54 | 7.13 | Na | Na | Na |

| MNA | 4.50 | 5.29 | 5.63 | 6.32 | 6.98 | Na | |

| MWA | 4.51 | 4.91 | 5.17 | 5.82 | 6.56 | 7.12 | |

| RNA | 4.52 | 5.36 | 5.71 | 6.91 | Na | Na | |

| RWA | 4.51 | 4.82 | 4.94 | 5.61 | 6.40 | 7.48 | |

| Pseudomonas spp. | CA | 4.21 | 5.58 | 6.38 | Na | Na | Na |

| MNA | 4.17 | 5.54 | 5.46 | 6.02 | 6.91 | Na | |

| MWA | 4.11 | 4.34 | 4.57 | 4.96 | 5.21 | 6.59 | |

| RNA | 4.15 | 5.58 | 5.49 | 6.31 | Na | Na | |

| RWA | 4.11 | 4.39 | 4.96 | 5.47 | 6.73 | 7.12 | |

| H2S-producing bacteria | CA | 3.13 | 5.58 | 6.21 | Na | Na | Na |

| MNA | 3.03 | 5.43 | 5.47 | 5.90 | 6.73 | Na | |

| MWA | 3.08 | 4.44 | 4.57 | 4.96 | 5.97 | 6.59 | |

| RNA | 3.03 | 5.47 | 5.52 | 6.31 | Na | Na | |

| RWA | 3.11 | 4.56 | 4.96 | 5.47 | 6.08 | 7.12 |

Values are expressed as the mean

D, day; C, Control; A, air; M, M. spicata EO; R, R. officinalis EO; W, warmed emulsion to 53

a, b, c, d indicate significant differences (p

| D0 | D3 | D6 | D9 | D12 | D16 | D20 | D24 | D28 | ||

| Enterobacteriaceae | CV | 3.58 | 5.04 | 5.21 | 6.44 | Na | Na | Na | Na | Na |

| MNV | 3.43 | 4.81 | 4.90 | 5.91 | 6.01 | 6.38 | Na | Na | Na | |

| MWV | 3.45 | 4.48 | 4.37 | 5.29 | 5.49 | 5.71 | 5.82 | 5.97 | 6.27 | |

| RNV | 3.48 | 4.93 | 5.02 | 5.89 | 5.95 | 6.48 | Na | Na | Na | |

| RWV | 3.46 | 4.41 | 4.47 | 5.49 | 5.78 | 5.97 | 6.01 | 6.41 | Na | |

| LAB | CV | 3.48 | 5.29 | 5.75 | 6.33 | Na | Na | Na | Na | Na |

| MNV | 3.43 | 5.24 | 5.43 | 5.89 | 6.03 | 6.39 | Na | Na | Na | |

| MWV | 3.44 | 4.91 | 5.11 | 5.40 | 5.47 | 5.36 | 5.66 | 5.91 | 6.12 | |

| RNV | 3.43 | 5.06 | 5.49 | 5.54 | 5.85 | 6.21 | Na | Na | Na | |

| RWV | 3.43 | 4.77 | 5.11 | 5.58 | 5.39 | 5.97 | 6.09 | 6.33 | Na | |

| H2S-producing bacteria | CV | 3.13 | 5.14 | 5.15 | 6.24 | Na | Na | Na | Na | Na |

| MNV | 3.03 | 4.90 | 4.99 | 5.90 | 6.01 | 6.28 | Na | Na | Na | |

| MWV | 3.10 | 4.37 | 4.44 | 5.19 | 5.82 | 5.91 | 5.95 | 6.10 | 6.71 | |

| RNV | 3.13 | 4.81 | 4.91 | 5.93 | 6.09 | 6.48 | Na | Na | Na | |

| RWV | 3.01 | 4.37 | 4.48 | 5.49 | 5.80 | 6.01 | 6.08 | 6.91 | Na |

Values are expressed as the mean

D, day; C, Control; V, vacuum; M, M. spicata EO; R, R. officinalis EO; W, warmed emulsion to 53

a, b, c, d indicate significant differences (p

At each sampling day, all microbial counts of treated chicken legs were significantly lower than those of control groups throughout the entire storage period (p

Most of the psychrotrophic bacteria found on the carcass immediately after processing are not of intestinal origin but originate from the feathers and feet of the live bird, the processing plant water supply, cooling tanks and processing equipment [21]. However, under vacuum packaging, spoilage bacteria in the control group under vacuum (CV) exceeded the acceptable limit by day 9, indicating rapid microbial proliferation in the absence of antimicrobial intervention. In contrast, treated chicken leg groups experienced delayed bacterial spoilage, with RNV and MNV thresholds reached on day 16, RWV on day 24, and MWV on day 28. These variations highlight the antimicrobial properties of M. Spicata and R. officinalis essential oils. The longer shelf life observed in MWV (19 days) and RWV (15 days) indicates that the combination of VP and warmed EO emulsions, particularly spearmint, had a strong antimicrobial effect. Additionally, it can be noted that VP itself plays a crucial role by creating an anaerobic environment that suppresses the growth of aerobic spoilage bacteria and limits lipid oxidation [22].

H2S-producing bacteria play an important role in fish and meat spoilage. Bonilla et al. [14] (2007) reported that the end of the shelf life of raw cod fillets was defined as the point at which the H2S-producing bacteria count reached approximately 7 log10 CFU·g–1. However, these bacteria are primarily represented by Shewanella putrefaciens, which produces off-odors resembling ammonia [21]. However, the main microorganism responsible for the deterioration of fresh meat is Pseudomonas. On the other hand, LAB is the most common spoilage microorganism in vacuum-packed meats [23].

Table 4 shows pH changes in chilled chicken legs under AP and VP conditions. The initial pH values for all chicken sample groups ranged from 6.96 to 7.03.

| D0 | D3 | D6 | D9 | D12 | D16 | D20 | D24 | D28 | ||

| Under vacuum | CV | 7.02 | 6.96 | 7.04 | 7.01 | 7.08 | 7.32 | Na | Na | Na |

| MNV | 6.96 | 7.00 | 7.01 | 6.96 | 7.08 | 7.24 | 7.31 | Na | Na | |

| MWV | 6.97 | 6.99 | 7.10 | 6.95 | 7.13 | 7.16 | 7.26 | 7.30 | 7.32 | |

| RNV | 7.03 | 7.01 | 7.00 | 7.03 | 7.17 | 7.32 | 7.32 | Na | Na | |

| RWV | 6.96 | 7.02 | 7.09 | 6.99 | 7.09 | 7.24 | 7.27 | 7.32 | Na | |

| Under air | CA | 7.03 | 7.02 | 6.94 | 7.13 | Na | Na | Na | Na | Na |

| MNA | 6.97 | 6.99 | 7.11 | 7.03 | 7.31 | Na | Na | Na | Na | |

| MWA | 6.97 | 7.02 | 6.95 | 6.98 | 7.23 | 7.33 | Na | Na | Na | |

| RNA | 6.97 | 7.06 | 7.11 | 7.02 | 7.32 | Na | Na | Na | Na | |

| RWA | 6.98 | 7.06 | 7.01 | 7.02 | 7.30 | 7.33 | Na | Na | Na |

Values are expressed as the mean

D, day; C, Control; V, vacuum; A, air; M, M. spicata EO; R, R. officinalis EO; W, warmed emulsion to 53

a, b, c indicate significant differences (p

During AP storage, pH values increased almost to the end of the shelf life, reaching 7.13 for the control group and ranging from 7.31 to 7.33 for the treated groups. The pH values in VP meats initially decreased slightly due to the activity of LAB, which characterizes the natural microflora. These bacteria produce organic acids as part of their metabolism, resulting in a slight pH decrease. pH values rose to 7.30 in the control group and from 7.31 to 7.32 at the end of shelf life. Warmed EO emulsions typically resulted in lower pH values (p

The spoilage threshold for chicken legs was determined using microbial counts and pH changes. Specifically, spoilage was considered to have occurred when Enterobacteriaceae, LAB, H2S-producing bacteria, Pseudomonas spp., and psychrotrophic bacteria exceeded 6 to 7 log10 CFU·g–1, which are associated with significant deterioration in meat quality. Furthermore, an increase in pH above 7.3 in most cases indicated advanced protein degradation and increased bacterial metabolic activity, which contributed to undesirable sensory changes, such as the development of off-odors. These combined indicators provide reliable criteria for determining the end of chicken meat’s shelf life under various storage conditions.

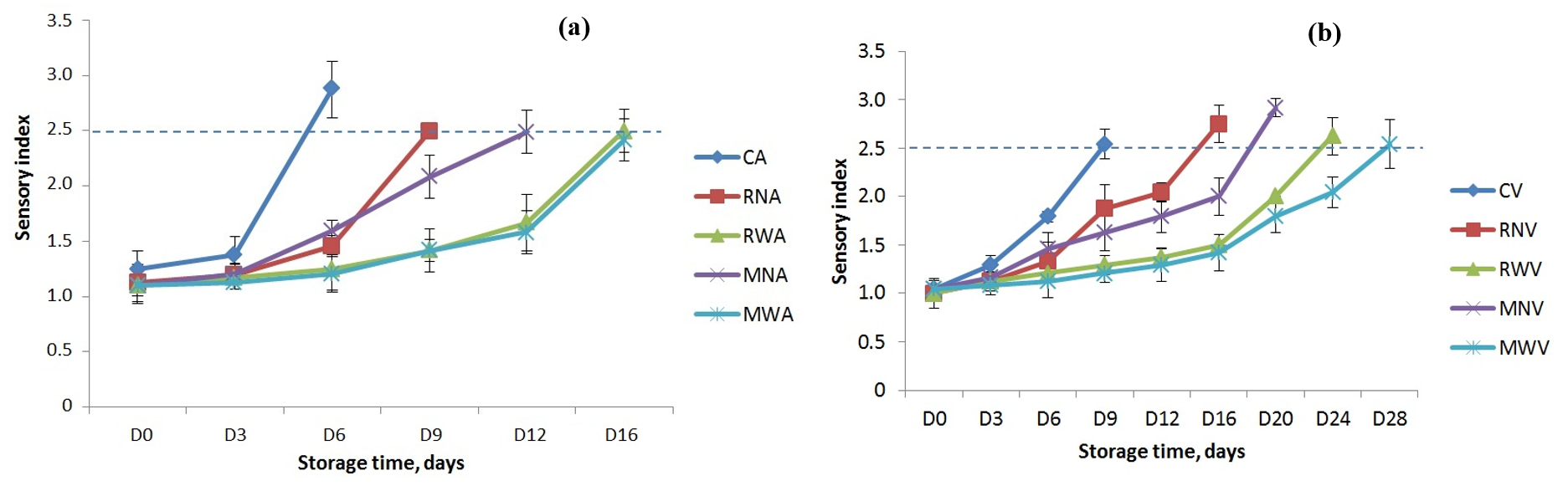

Fig. 1a,b show the sensory index quality of raw chicken legs stored at 4

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Sensory assessment of raw chicken legs with different dipping treatments stored at 4

According to Russell et al. [21] (1995), eviscerated fresh carcasses have an average shelf life of 6 to 8 days when stored at 4.4 °C. Dipping chicken legs in a 0.4% M. spicata or R. officinalis EO emulsion warmed to 53

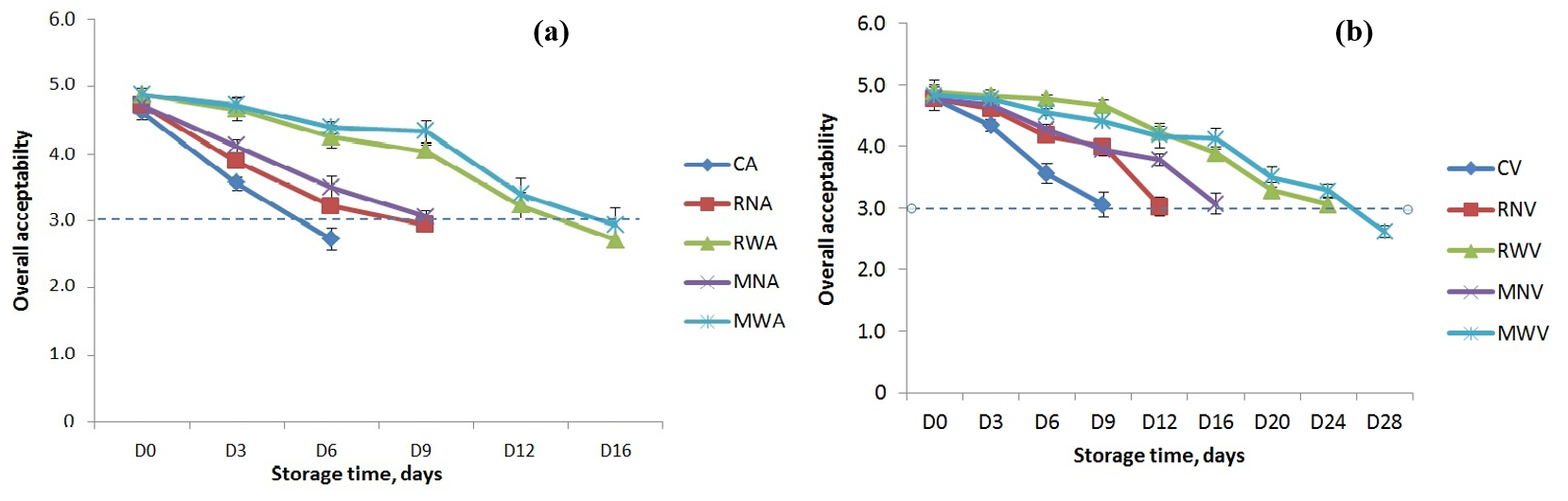

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Change in overall acceptability score of cooked chicken legs with different dipping treatments stored at 4

Significant differences (p

In this study, both EO emulsions demonstrated antimicrobial activity under all conditions. This effect is due to R. officinalis EO’s high concentration of oxygenated monoterpenes, particularly eucalyptol and camphor, which demonstrated antibacterial properties by increasing membrane permeability and disrupting bacterial metabolism [26].

A previous study found that adding rosemary essential oil (0.2% v/w) to vacuum-packed precooked chicken meat reduced spoilage bacteria but only extended the shelf life by 7 days [27]. Under various conditions, spearmint EO outperforms rosemary EO in terms of antimicrobial activity despite the latter’s high eucalyptol content (52.09%). Similarly, in food science, Burt [19] (2004) reviewed and ranked the antibacterial effects of essential oils, with mint outperforming rosemary. This finding could be explained by the stability of M. spicata EO, which retained its activity at 80 °C and was effective for up to 24 months when stored at room temperature [28].

Furthermore, its bioactive compounds, particularly carvone, are now important in the agri-food chain due to their inhibitory effect on various microorganisms that cause food spoilage; however, the mechanism of action is not fully understood. Some authors have reported that it works by influencing the metabolic energy status of the microbial cell [28]. Additionally, carvone exhibits antimicrobial activity by disrupting bacterial cell membranes and interfering with key enzymatic functions, leading to impaired cellular homeostasis [19]. Another hypothesis to explain the higher activity of M. spicata EO compared to R. officinalis used in this study to immerse chicken legs is that spearmint’s antibacterial activity is strongly related to food characteristics, which increase in low-fat products [28]; chicken meat is known for its low-fat content.

Additionally, M. spicata EO and sodium chloride have a synergistic effect. When salt is added to chicken meat, the antimicrobial activity of this essential oil may increase dramatically. The current findings are consistent with previous research, which found that adding 0.5% M. spicata to raw minced camel meat stored at 4 °C extended the shelf life to 12 days while decreasing total mesophilic, psychrotrophic bacteria, Pseudomonas spp., and Enterobacteriaceae counts by about 1–2 log CFU/g in treated samples compared to the control [29]. In another study, authors found that edible films enriched with 2% M. spicata EO used for cheese coating improved shelf life and had antimicrobial activity against pathogenic bacteria [30]. However, another study used a lower concentration of M. spicata EO than ours and found the same results in extending the shelf life of vacuum-packed chicken thighs by 16 days, but only with 0.2% spearmint EO [31].

In this study, the chicken legs were immersed in EO emulsions warmed to the same temperature and duration as soft scalding, which involves immersing the carcass in warm water at 53 °C for 3 minutes to effectively remove feathers. This aids in the release of feather quills from feather follicles located within the skin. As a result, warmed EO emulsions perform better than room-temperature emulsions. This finding could be explained by the penetration of EO emulsions into the skin’s dilated pores, which host a variety of bacteria. Chicken legs stored in air or vacuum were found to be better preserved with warmed EO emulsions of M. spicata and R. officinalis at 0.4% while maintaining acceptable sensory and microbial quality during chilled storage. As expected, the ideal treatment for preserving raw and cooked chicken legs was MWV.

Dipping chicken meat in warmed emulsions of Mentha spicata and Rosmarinus officinalis essential oils (0.4%) was found to be an effective strategy for increasing shelf life under both aerobic and vacuum packaging conditions. Warming the EO emulsions significantly increased their antibacterial activity. Notably, chicken legs immersed in warmed emulsions of R. officinalis or M. spicata and vacuum-packed had a shelf life of 15 and 19 days longer, respectively, than the control group. This finding demonstrates the ability of this natural preservation method to inhibit spoilage bacteria while preserving the sensory properties of the meat. Furthermore, the shelf lives determined by sensory tests were generally consistent with those discovered through microbial analysis.

In addition to their antimicrobial effects, the potential antioxidant properties of warmed essential oils necessitate further research to comprehensively elucidate their function in meat preservation. Moreover, subsequent investigations should concentrate on enhancing the utilization of essential oils in meat products, especially regarding potential interactions between the bioactive compounds of essential oils and meat constituents that may affect their effectiveness and sensory attributes. Evaluating consumer acceptability and regulatory considerations of essential oil-based treatments will be vital for their effective integration into the food industry.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the formats specified on the journal’s website. Additional data may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ZM and TL designed and performed the study. KG contributed to the interpretation of results and critically revised the manuscript. AB and RNB provided help and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We thank the Microbiology Station team of the Laboratory of Quality Control and Repression of Frauds, Djelfa, Algeria, for their support.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.