- Academic Editor

Background: Considering the possibility of surgical

intervention affecting the survival benefit of elderly patients, the relationship

between lymph node dissection and the survival of elderly patients with stage I

ovarian cancer (OC) was retrospectively analyzed. Methods: This was a

retrospective cohort study using the database in Surveillance, Epidemiology and

End Results (SEER) which was queried to identify 8191 women with stage I OC

treated with surgery from 1975 to 2016. Frequencies and percentages were

presented to describe the categorical data. Pearson

Ovarian Cancer (OC) is the most lethal gynecological malignancy [1], and has the highest mortality rate among female reproductive tract malignancies [2]. Early diagnosis and staging determine the prognosis of the disease. The proportion of patients with early-stage ovarian cancer is increasing as diagnostic and treatment technologies continue to improve. As life expectancy continues to increase, this results in an increase in the proportion of elderly patients with OC. Advances in the treatment of ovarian cancer, such as advanced surgical procedures, intravenous chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel, and abdominal chemotherapy, have led to an increase in 5-year survival rates from 34.8% in 1975 to 44.6% in 2011 [3]. However, the treatment progress of ovarian cancer is still significantly worse than that of other types of solid tumors [4]. Greater than 10 years ago, an analysis of the European research on adjuvant chemotherapy for ovarian malignant tumors demonstrated that the surgical staging of patients with early ovarian malignant tumors improved tumor-free survival and overall survival [5]. This finding has led to national and international guidelines for the treatment of early ovarian malignancies recommending surgical staging [6, 7], including hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, cytological examination, peritoneal biopsy, and pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy. The purpose of definitive surgery is to completely remove the tumor, determine the pathological diagnosis and staging of ovarian cancer, determine the histological subtype and grade of the disease, and determine the risk factors, in order to select the appropriate follow-up treatment (including chemotherapy and treatment duration, etc.). Based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, this study evaluated the clinicopathological features and prognostic factors of early ovarian cancer and to provide new ideas for the therapeutic benefits of lymph node dissection in the clinical diagnosis and treatment of early ovarian cancer in women over age 70.

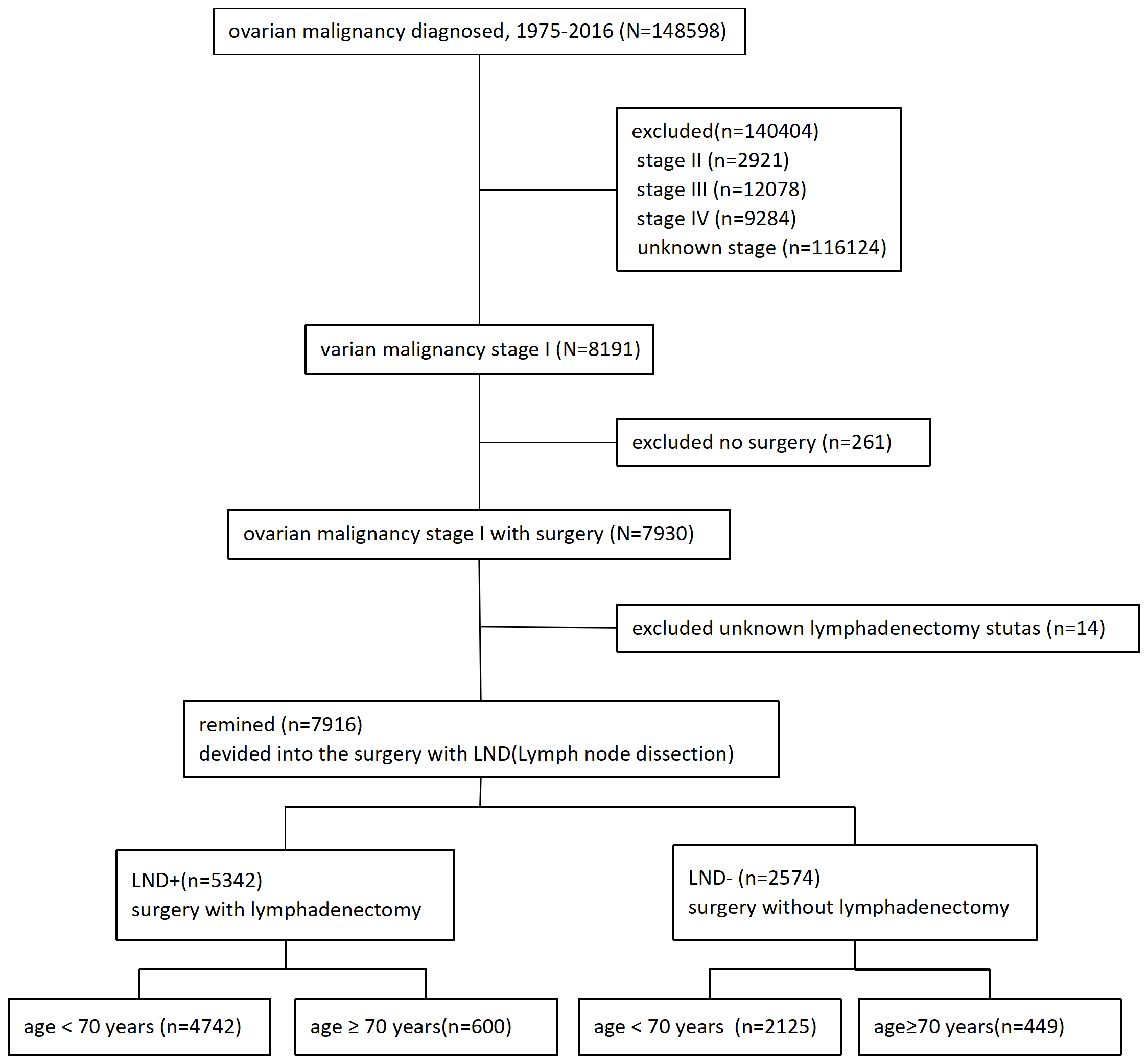

Ovarian cancer cases were identified through the SEER program of the National Cancer Institute, which included data of 27.8% of the US population from 11 states and 7 areas. The information was accessed from the SEER database, and the requirement for informed consent was exempted by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board. Data were extracted from the SEER18 Regs Research Data as well as Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases (1975–2016) using SEER*STat 8.3.6 (http://www.seer.cancer.gov). The inclusion criteria for the SEER 18 registries included: (1) the pathological diagnosis was primary ovarian cancer; (2) the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), stage T1 ovarian cancer; (3) surgical treatment of the primary lesion; (4) clear follow-up data. The exclusion criteria for the SEER 18 registries included: (1) unilateral and bilateral tumor unknown; (2) unknown SEER stage; (3) survival status of the patient unknown; (4) unknown survival time; (5) unknown tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage; (6) unknown lymph node dissection; and (7) multiple primary tumors. According to inclusion and exclusion criteria, 7916 patients were finally included, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Selection criteria. Stage I ovarian cancer treated by surgery. LND, lymph node dissection.

Demographic characteristics included age at diagnosis, specific year, race, place of SEER registration, and marital status. The pathological features of the tumor, including the location of the primary tumor, histological grade, lymph node metastasis and lymph node resection are shown in Table 1. The tumor stage was determined by the 7th edition AJCC ovarian cancer TNM stage. Histological classification was based on the World Health Organization (WHO) standards for ovarian cancer, and histological classification included Grade Ⅰ, Grade Ⅱ, Grade III, and Grade IV. According to the extent of surgical intervention, the patients were divided into lymph node resection group and lymph node preservation group. The follow-up period was extended to 31 December 2019. The main outcome measures included overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS). OS time is defined as the time interval from the time of pathological diagnosis of the patient to the time of death. CSS time was defined as the time interval from when a patient was pathologically diagnosed with ovarian cancer to the time the patient died of ovarian cancer.

| Demographic | Value (%) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 5289 (66.81) | ||

| 61–69 | 1578 (19.93) | |

| 70–79 | 727 (9.18) | |

| 322 (4.07) | ||

| Race | ||

| White | 6270 (79.21) | |

| Black | 595 (7.52) | |

| Other | 976 (12.33) | |

| Unknown | 75 (0.94) | |

| SEER registry | ||

| Midwest | 410 (5.18) | |

| Northeast | 1345 (16.99) | |

| South | 1914 (24.18) | |

| West | 4247 (53.65) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 3883 (49.05) | |

| Single | 3655 (46.17) | |

| Unknown | 378 (4.78) | |

| Laterality | ||

| Right | 3631 (45.87) | |

| Left | 3594 (45.40) | |

| Bilateral | 639 (8.07) | |

| Unknown | 52 (0.66) | |

| Tumor grade | ||

| Grade I | 1730 (21.85) | |

| Grade II | 1722 (21.75) | |

| Grade III | 1500 (18.95) | |

| Grade IV | 877 (11.08) | |

| Unknown | 2087 (26.36) | |

| Lymph node detection | ||

| No nodes were examined | 2553 (32.25) | |

| Nodes were examined | 5217 (65.90) | |

| Undefined | 146 (1.84) | |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||

| All nodes examined are negative | 5347 (67.55) | |

| No nodes were examined | 2552 (32.24) | |

| Undefined | 17 (0.21) | |

| LND | ||

| LND+ | 5342 (67.48) | |

| LND− | 2574 (32.52) | |

SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results; LND+, lymph node dissection; LND–, no lymph node dissection.

SPSS for Windows version 25.0 (IBM SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for

statistical analysis and chi-square test was used to compare the characteristic

distribution of baseline data. The influencing factors of lymph node metastasis

were analyzed by logistic regression. Survival information and survival curves

were obtained by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Univariate and multivariate Cox

regression models were used to analyze the independent prognostic factors. All

statistical analyses were the two-side test, and p

Baseline data of all patients are shown in Table 2. A total of 7916 patients were included according to the inclusion criteria, among whom intraoperative lymph node dissection was performed at the same time: 1135 patients (71.9%) aged 61–69, 456 patients (62.7%) aged 70–79, and 144 patients (44.7%) aged 80 years or older. Among the patients who underwent surgery, there was a difference in overall survival when lymph node dissection was performed in patients older than 70 years.

| Characteristics | LND+ | LND– | Adjusted OR | Upper limit | Lower limit | p | |

| 95% CI | |||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 3607 (68.2) | 1682 (31.8) | 1 | |||||

| 61–69 | 1135 (71.9) | 443 (28.1) | 0.911 | 0.801 | 1.035 | 0.153 | |

| 70–79 | 456 (62.7) | 271 (37.3) | 1.369 | 1.153 | 1.609 | ||

| 144 (44.7) | 178 (55.3) | 2.779 | 2.19 | 3.526 | |||

| Race | |||||||

| White | 4338 (69.2) | 1932 (30.8) | 1 | ||||

| Black | 294 (49.4) | 301 (50.6) | 2.057 | 1.721 | 2.458 | ||

| Other | 665 (68.1) | 311 (31.9) | 1.083 | 0.931 | 1.259 | 0.303 | |

| Unknown | 45 (60.0) | 30 (40.0) | 1.569 | 0.974 | 2.526 | 0.064 | |

| SEER registry | |||||||

| Midwest | 287 (70.0) | 123 (30.0) | 1 | ||||

| Northeast | 968 (72.0) | 377 (28.0) | 0.864 | 0.672 | 1.111 | 0.255 | |

| South | 1217 (63.6) | 697 (36.4) | 1.339 | 1.054 | 1.702 | 0.017 | |

| West | 2870 (67.6) | 1377 (32.4) | 1.204 | 0.958 | 1.515 | 0.112 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 2769(71.3) | 1114 (28.7) | 1 | ||||

| Single | 2314 (63.3) | 1341 (36.7) | 1.256 | 1.135 | 1.39 | ||

| Unknown | 259 (68.5) | 119 (31.5) | 1.062 | 0.838 | 1.345 | 0.618 | |

| Laterality | |||||||

| Right | 2459 (67.7) | 1172 (32.3) | 1 | 0.471 | |||

| Left | 2400 (66.8) | 1194 (33.2) | 1.05 | 0.949 | 1.161 | 0.349 | |

| Bilateral | 454 (71.0) | 185 (29.0) | 0.965 | 0.797 | 1.168 | 0.713 | |

| Unknown | 29 (55.8) | 23 (44.2) | 1.412 | 0.794 | 2.511 | 0.24 | |

| Tumor grade | |||||||

| Grade I | 1165 (67.3) | 565 (32.7) | 1 | ||||

| Grade II | 1244 (72.2) | 478 (27.8) | 0.773 | 0.666 | 0.896 | 0.001 | |

| Grade III | 1078 (71.9) | 422 (28.1) | 0.768 | 0.657 | 0.897 | 0.001 | |

| Grade IV | 668 (76.2) | 209 (23.8) | 0.598 | 0.494 | 0.724 | ||

| Unknown | 1187 (56.9) | 900 (43.1) | 1.534 | 1.34 | 1.757 | ||

| Survival | |||||||

| Alive | 4902 (68.4) | 2264 (31.6) | 1 | ||||

| Dead | 440 (58.7) | 310 (41.3) | 1.393 | 1.183 | 1.64 | ||

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis: Fig. 2A showed that there was no significant correlation between intraoperative lymph node dissection and specific survival (CSS) in stage I ovarian cancer patients over age 70 (p = 0.190). Fig. 2B showed that there was a significant correlation between intraoperative lymph node dissection and OS in stage I ovarian cancer patients over age 70 (p = 0.002).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing the CSS (A) and OS (B) analysis of patients over 70 years of age with intraoperative lymph node dissection. CSS, cancer-specific survival; OS, overall survival.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using Cox proportional

hazard method. Univariate analysis showed that age

| Characteristic | Overall survival | Cause specific survival | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 61–69 | 0.189 | 0.151–0.235 | 1.251 | 0.973–1.609 | 0.08 | ||

| 70–79 | 0.301 | 0.235–0.386 | 1.944 | 1.457–2.593 | |||

| 0.519 | 0.401–0.674 | 2.392 | 1.605–3.564 | ||||

| Race | |||||||

| White | 0.095 | 0.004 | |||||

| Black | 1.356 | 1.066–1.724 | 0.013 | 1.746 | 1.291–2.362 | ||

| Other | 0.987 | 0.787–1.237 | 0.908 | 1.103 | 0.815–1.492 | 0.527 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0–1.143 × 10 |

0.871 | 0 | 0–6.118 × 10 |

0.906 | |

| SEER registry | |||||||

| Midwest | 0.003 | 0.078 | |||||

| Northeast | 1.652 | 1.069–2.554 | 0.024 | 1.582 | 0.853–2.935 | 0.146 | |

| South | 2.03 | 1.332–3.095 | 0.001 | 2.027 | 1.116–3.681 | 0.02 | |

| West | 1.64 | 1.086–2.478 | 0.019 | 1.851 | 1.035–3.311 | 0.038 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | |||||||

| Single | 1.465 | 1.265–1.698 | 1.445 | 1.182–1.768 | |||

| Unknown | 0.899 | 0.607–1.333 | 0.597 | 0.616 | 0.325–1.165 | 0.136 | |

| Laterality | |||||||

| Right | 0.05 | 0.001 | |||||

| Left | 1.036 | 0.889–1.206 | 0.653 | 1.19 | 0.961–1.471 | 0.111 | |

| Bilateral | 1.405 | 1.103–1.789 | 0.006 | 1.912 | 1.401–2.61 | ||

| Unknown | 1.023 | 0.423–2.475 | 0.959 | 1.289 | 0.411–4.039 | 0.664 | |

| Tumor grade | |||||||

| Grade I | |||||||

| Grade II | 1.346 | 1.046–1.731 | 0.021 | 1.807 | 1.223–2.671 | 0.003 | |

| Grade III | 2.3 | 1.819–2.908 | 3.558 | 2.479–5.106 | |||

| Grade IV | 2.575 | 1.985–3.341 | 4.141 | 2.812–6.098 | |||

| Unknown | 1.371 | 1.075–1.749 | 0.011 | 1.986 | 1.365–2.89 | ||

| LND | |||||||

| LND+ | |||||||

| LND– | 1.592 | 1.377–1.842 | 1.241 | 1.01–1.526 | 0.04 | ||

| Multivariate Analysis | |||||||

| Characteristic | Overall survival | Cause specific survival | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 61–69 | 1.547 | 1.283–1.864 | 1.186 | 0.919–1.529 | 0.19 | ||

| 70–79 | 2.581 | 2.107–3.162 | 1.831 | 1.369–2.448 | |||

| 4.167 | 3.304–5.255 | 1.901 | 1.261–2.865 | 0.002 | |||

| Race | |||||||

| White | 0.129 | 0.006 | |||||

| Black | 1.346 | 1.047–1.729 | 0.02 | 1.764 | 1.284–2.423 | ||

| Other | 1.087 | 0.863–1.37 | 0.478 | 1.093 | 0.803–1.487 | 0.573 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0–1.143 × 10 |

0.897 | 0 | 0–2.04 × 10 |

0.911 | |

| SEER registry | |||||||

| Midwest | 0.002 | 0.142 | |||||

| Northeast | 1.623 | 1.049–2.512 | 0.001 | 1.599 | 0.861–2.97 | 0.137 | |

| South | 1.856 | 1.215–2.836 | 0.61 | 1.872 | 1.028–3.411 | 0.04 | |

| West | 1.651 | 1.091–2.498 | 0.034 | 1.875 | 1.046–3.36 | 0.035 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 0.03 | 0.002 | |||||

| Single | 1.301 | 1.116–1.517 | 0.004 | 1.367 | 1.11–1.683 | 0.003 | |

| Unknown | 0.902 | 0.607–1.341 | 0.018 | 0.634 | 0.334–1.205 | 0.164 | |

| Laterality | |||||||

| Right | 0.02 | ||||||

| Left | 1.011 | 0.868–1.178 | 0.042 | 1.16 | 0.937–1.437 | 0.172 | |

| Bilateral | 1.255 | 0.982–1.603 | 1.654 | 1.206–2.268 | 0.002 | ||

| Unknown | 0.979 | 0.404–2.375 | 1.162 | 0.369–3.654 | 0.798 | ||

| Tumor grade | |||||||

| Grade I | 0.025 | ||||||

| Grade II | 1.3 | 1.009–1.674 | 0.318 | 1.791 | 1.21–2.649 | 0.004 | |

| Grade III | 2.087 | 1.647–2.645 | 0.889 | 3.346 | 2.324–4.818 | ||

| Grade IV | 2.361 | 1.814–3.074 | 0.069 | 3.951 | 2.672–5.844 | ||

| Unknown | 1.323 | 1.036–1.69 | 0.963 | 1.933 | 1.326–2.818 | 0.001 | |

| LND | |||||||

| LND+ | 1.441 | 1.239–1.677 | 1.197 | 0.965–1.484 | 0.102 | ||

| LND– | |||||||

HR, hazard ratio.

In the treatment of early ovarian cancer, the initial staging operation is very

important [8]. In clinical practice, whether the surgical scope of early ovarian

cancer requires systematic lymph node dissection has been a controversial issue

[9]. According to statistics, the lymph node positive rate of early ovarian

cancer is approximately 13%–20% [10]. In the current guidelines for ovarian

cancer, the mainstream view is to recommend intraoperative lymph node dissection

for early stage patients. In a retrospective analysis of over 6000 patients, Chan

et al. [11] concluded that lymph node dissection improved the 5-year

survival rate of Federation International of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)

Stage I patients from 87.0% to 92.6% (p

There are some limitations to this study. First, this study was a retrospective clinical study over a large time span. The improvement in surgical instruments and better trained surgeons have affect the survival benefits to patients. This study was based on the prognosis of ovarian cancer in the United States, which may be different from the real situation of ovarian cancer in China. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a multi-center with a large-sample size on the Chinese population in order to obtain results applicable to Chinese women.

In our study, lymph node dissection was found to be an independent predictor of improved long-term OS in patients with stage I ovarian cancer, with a significant benefit in older women. Therefore, we need to carefully consider the choice of surgical methods in order to obtain a more beneficial prognosis.

CI, confidence interval; EC, endometrial cancer; HR, hazard ratio; LND+, lymph node dissection; LND–, no lymph node dissection; OR, odds ratio; OS, overall survival; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute.

GH and CC designed the research study. GH and GZ performed the research. All authors analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The SEER data are public and free of charge so no ethical review and individual consent are required.

Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.