- Academic Editor

Background: Unwanted pregnancies cause some type of stress in women, which negatively impacts their way of life. It is important to recognize this type of stress and consider potential interventions. We aimed to comprehend the factors influencing married and parous women’s fertility decisions facing pregnant unintentionally, to provide a reference point for health care, and policy development. Methods: 44 married and parous women with unintended pregnancies who visited a tertiary hospital in Suzhou from May 2021 to July 2021 were chosen using a combination of purposive and theoretical sampling techniques for semi-structured, open-ended interviews. The Lazarus stress-coping model was used to construct the central theme of the analysis, which was “stress-coping style for fertility decision-making among married and parous women with unwanted pregnancy”. The model is divided into three stages: identifying re-fertility stressors, assessing re-fertility coping skills, and making decisions. Results: It takes the combined efforts of society, healthcare, families, and couples to ensure that married and parous women feel secure about having another child. Social support, medical care, and family sharing are all significant factors in the decision to have a child with an unwanted pregnancy. Conclusions: To increase people’s internal motivation to have more children and to support balanced population development, we must first create a healthy and favorable environment for fertility in society.

An unwanted pregnancy, also known as unintended pregnancy, is a pregnancy that occurs when a woman does not want to have a child and is caused by a lack of contraception or contraceptive failure [1, 2]. The previous study [3] showed that women with unwanted pregnancies are at 1.459 to 2.690 times higher risk of stress than those women with wanted pregnancies. Folkman et al. [4] has raised the Stress and Coping Model theory, stating that stressors act on individuals in relative ways to cope with stress through primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, and reappraisal. Fertility decision-making, which is a choice made by a family or individual regarding whether to have children or not, is the result of a married and parous woman’s reaction to an unwanted pregnancy. It involves the transition from fertility intention to behavior [5]. For women with unwanted pregnancies, the outcomes include pregnancy termination and pregnancy continuation [6, 7]. Pregnancy termination by induced abortion has immediate and long-term physiological and negative effects on women, imperils fertility, and is a serious phenomenon among married and parous women in China [8, 9]. According to the seventh census, China’s total fertility rate has dropped to 1.3, which is significantly lower than the population replacement level of 2.1. This will cause a growing number of social issues, including population decline, workforce decline, and economic downturn. Even though China has adopted the three-child limit, the lax fertility regulations have not led to a rise in fertility, and other factors besides the three-child limit also play a role [10]. Therefore, it is important to focus on the ways married and parous women cope with unwanted pregnancy stress and to explore the factors influencing their fertility decision. Pregnancy and childbirth are regarded as joyful and happy life events that typically elicit positive emotions. Pregnancy itself, however, has the potential to be a stressful and challenging life event in certain situations. According to psychological research on pregnancy, long-term stress has negative effects on both the physical and mental health of the mother and child and increases the risk of preterm birth [11, 12, 13, 14]. The susceptibility of pregnant women to stress may be increased by conditions like emotional instability, a lack of safety assurances, future uncertainty, a bad relationship with or weak support from a partner, single status, low education level, financial hardship, early maternal age, having many children in the home, and a death of a sufficient social support network [15, 16, 17]. These stressors may have a cumulative effect or act separately, exceeding pregnant women’s capacity for adaptation. Therefore, the father’s acknowledgement of paternity will also significantly lessen stress among unmarried women. One of the most trying long-term experiences a woman can go through is getting pregnant unexpectedly or unintentionally, especially if she is not married [18, 19, 20].

In this study, married women who have already had children are asked to describe how they deal with the stress of an unplanned pregnancy. The factors influencing their decision to become pregnant are also examined, and a model of stress-coping based on the Lazarus stress-coping model is developed for married women who have already had children.

Married, fertile women with unintended pregnancies who visited a tertiary

hospital in Suzhou from May 2021 to July 2021 were chosen as the study

population, using the purposive sampling method and theoretical sampling method.

Inclusion criteria: (1) women who had performed an abortion at family planning

clinics, or women who had undergone antenatal check-ups at obstetric clinics; (2)

intrauterine pregnancy indicated by ultrasound; (3) unwanted pregnancy; able to

communicate and exchange effectively; (4) informed consent and voluntary

participation in this study. Exclusion criteria: (1) unmarried or married women

who have no born children; (2) those with psychiatric disorders or a history of

psychosis; (3) those who chose to terminate their pregnancy due to various

medical conditions that made it inadvisable to continue the pregnancy, and/or the

examination revealed an abnormal embryo; (4) those whose interview data

collection was incomplete and who could not be interviewed again. According to

the principle of maximum differentiation in qualitative research, the sample was

selected with due consideration of characteristics such as age, education level,

occupation, and reproductive history. The sample size was based on data

saturation and no new information emerged. A total of 44 married and parous, but

unwanted pregnant women, aged 23–40 (33.00

| No. | Age (years) | Occupation | Education level | Sex and age of current children | Number of previous abortions | Marital status | Fertility decision-making |

| N1 | 34 | Freelance | University | Son (11 years old), daughter (4 years old) | 3 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N2 | 35 | Nurse | University | Daughter (10 years old) | 3 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N3 | 31 | Electronics R&D | University | Son (3 years old) | 1 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N4 | 30 | Telecommunications staff | University | Son (7 years old) | 2 | Remarriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N5 | 31 | Staff | Junior High School | Son (9 years old) | 2 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N6 | 30 | Temporary worker | Lower Secondary | Son (14 months) | 0 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N7 | 23 | Full-time mother | Junior High School | Son (4 years old), Son (2 years old) | 1 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N8 | 31 | Teacher | University | Daughter (4 years old) | 1 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N9 | 31 | Staff | University | Son (2 years old) | 1 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N10 | 34 | Police | University | Son (8 years old) | 0 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N11 | 40 | Staff | University | Daughter (16 years old), Daughter (7 years old) | 2 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N12 | 34 | Roadside assistance | Secondary School | Son (8 years old) | 1 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N13 | 36 | Worker | Junior High School | Son (16 years old) | 0 | Remarriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N14 | 35 | Freelance | Secondary School | Daughter (15 years old) | 1 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N15 | 31 | Media | University | Son (3 years old) | 0 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N16 | 27 | Trainee doctor | University | Son (20 months) | 0 | First Marriage | Continuation of pregnancy |

| N17 | 30 | Nurse | Tertiary | Son (2 years old) | 0 | First Marriage | Continuation of pregnancy |

| N18 | 39 | Staff | Tertiary | Daughter (13 years old) | 1 | First Marriage | Continuation of pregnancy |

| N19 | 37 | Staff | University | Son (8 years old) | 0 | First Marriage | Continuation of pregnancy |

| N20 | 38 | Freelance | High School | Daughter (6 years old) | 0 | Remarriage | Continuation of pregnancy |

| N21 | 38 | Full-time wife | University | Daughter (11 years old) | 2 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N22 | 25 | Freelance | Lower Secondary | Son (5 years old), Daughter (2 years old) | 2 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N23 | 39 | Teacher | University | Son (8 years old) | 0 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N24 | 31 | Temporary worker | High School | Son (4 years old) | 1 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N25 | 35 | Housewife/Shopkeeper | High School | Daughter (5 years old), Son (2.5 years old) | 0 | First Marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N26 | 32 | Own business | University | Daughter (2 years old) | 0 | First Marriage | Continuation of pregnancy |

| N27 | 27 | Medical Technician | University | Son (2 years old) | 1 | First Marriage | Continuation of pregnancy |

| N28 | 35 | Nurse | University | Son (5 years old), Daughter (2 years old) | 2 | Remarriage | Termination pregnancy |

| N29 | 30 | Freelancer | University | Daughter | 1 | First marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N30 | 28 | Housewife | High school | Son (3 years old) | 0 | First marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N31 | 35 | Health technician | University | Son (4 years old) | 1 | First marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N32 | 29 | Teacher | University | Daughter (3 years old) | 0 | First marriage | Continuation of pregnancy |

| N33 | 34 | Receptionist | High school | Daughter (4 years), Son (2 years old) | 2 | First marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N34 | 28 | Marketing | High school | Son (3 years old) | 0 | First marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N35 | 32 | Shop keeper | Primary school | Son (4 years old) | 1 | First marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N36 | 37 | Nurse | University | Son (5 years old) | 0 | First marriage | Continuation of pregnancy |

| N37 | 27 | Odd job | Primary school | Daughter (3 years old) | 1 | First marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N38 | 30 | Teacher | University | Son (3 years old) | 1 | First marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N39 | 28 | Housewife | Middle school | Son (2 years old) | 2 | First marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N40 | 33 | Freelancer | High school | Daughter (3 years old) | 1 | First marriage | Continuation of pregnancy |

| N41 | 30 | Online tutor | University | Son (4 years old) | 1 | Remarriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N42 | 34 | Banker | University | Daughter (3 years old) | 1 | First marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

| N43 | 25 | Student | University | Daughter (1.5 years old) | 0 | First marriage | Continuation of pregnancy |

| N44 | 28 | Freelancer | High school | Son (3 years old) | 1 | First marriage | Termination of pregnancy |

R&D, research and development.

Beginning with a review of both local and international literature, the researcher created an interview outline. The subject group conducted pre-interviews with two patients and then consulted two clinical nursing experts to modify and finalize the interview content as follows. This was done after discussion and modification with two experts: (1) How did you make the decision whether to keep the baby or not when you were informed of an unwanted pregnancy? (2) How did you feel about unwanted pregnancies? (3) What perceptions or practices of people around you (e.g., family, friends) influenced your decision to have a baby or not? (4) What other factors influenced your decision?

In this study, interviews were conducted by trained interviewers with married and parous women with unwanted pregnancies. The purpose, specific process and format of the interview were made clear to the interviewees before the interview, the principles of informed consent and confidentiality were followed, and an informed consent form was signed. The interview was conducted in a semi-structured, open-ended manner in a quiet environment to understand the real thoughts of the interviewees and to ensure that each question in the outline was answered fully and honestly without deviating from the topic. Interviews were conducted with attention to voice, intonation, pauses, facial expressions and body language, and were limited to 20–30 min. Brief written, and audio recordings were made of the interview content. These recordings have been approved by the Ethical committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, China.

The Glaser Root Theory research method was used to analyze the data. The audio data or transcripts were transcribed verbatim within 24 hours of the interviews and coded at 3 levels. In open coding, the information was broken down and codes were sought from it to extract and develop categories through comparison. In spindle coding, the interrelationships between the taxa in which thematic clues were found are identified and verified in the material. In selective coding, the core genera are honed, and as many connections as possible are made between the core and individual genera.

The 14 categories were examined, coded, and grouped into the central theme of “stress-coping style for fertility decision making among married and parous women with unwanted pregnancy” using the theoretical coding strategy of “cause, process, outcome” from the conventional “Glaserian roots theory” (See Fig. 1). The model of stress-coping among married and parous women with unwanted pregnancies was based on the Lazarus stress-coping model, which consists of three stages and 11 causes. After the emergence of unwanted pregnancy, married and parous women have the stages of identifying the stressors of reproduction, evaluating their ability to cope with reproduction and making decisions about reproduction, which are interpenetrating and cyclical. They are all important factors that influence married and parous women’s decision to have another child.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Stress-coping style for fertility decision-making among married and parous women with unwanted pregnancy.

There is a consensus that pregnancy in women over a certain age not only poses a risk to their health but also increases the likelihood of fetal malformations. N4: “I feel that having a baby at 30 is a little too old (…) and I feel that it is better to have a baby at a younger age. I was 23 when I gave birth to my son, (it was) a caesarean section. I sat up at once after the operation. The woman close to my bedside was around her thirties, whose recovery was not satisfactory. (Termination of pregnancy)”. Moreover, due to lack of planning, women with unwanted pregnancies may use medication before and after pregnancy. Because they are not informed about the effects of medication on the health of the fetus, this causes women to worry about the physical health and mental development of the fetus. N8: “I wanted to have a baby, but I had no choice. I had just had the COVID-19 vaccine and I am afraid to have a baby, which is too close to pregnancy, and it doesn’t guarantee the health of the fetus. If something goes wrong later, it will ruin the whole family and it is not acceptable”. Furthermore, the high level of concern for eugenics has led to concerns about the health of the fetus, directly leading to the termination of pregnancy for married women who have had children.

Pregnancy and childbirth are unique experiences in a woman’s life. Both vomiting and labor pains can be unbearable, and married and parous women fear going through them again. N12: “When I had my son, I threw up after every meal with no exception, which condition had persisted for 7 months, including the operating table. (Termination of pregnancy)”. N6: “The pressure of childbirth was a bit too much; I was a bit scared. When I entered the labor ward, no one cared about me. I just had painful contractions, and even the uterine orifice was opened with ten fingers dilation. While the medical staff told me to make an effort, I pause just one moment. Let me make an effort. I can’t give birth if I didn’t make an effort. I felt quite helpless. (Termination of pregnancy)”. As age progresses, the risk of pregnancy complications gradually increases. It leads to more fears of continuing pregnancy for married and parous women of unwanted pregnancies.

As society develops and greater emphasis is placed on education, a new generation of child-rearing concepts has emerged, in which having a child is no longer just about being well-fed and clothed. Indeed, this is about being able to provide good living conditions for the child, and holistically raising a child has become a social norm, resulting in more time and experience spent on child-rearing. N21, N24, N27: “For the sake of economy, money is mostly spent on her, as we have only one child. (Termination of pregnancy)”. N8: “We have no more enthusiasm for it (rearing another child), which is the main problem for us. The school fees are expensive, which is already costly. However, there are also too many tutorials and extra classes for all children. It prompted us to pay more for my child. (Termination of pregnancy)”. N6: “We need to make sure that the child has good conditions before we can have another baby. At least we can improve a little bit, that is to say, if (the child is) sick or needs something, it will not be worse than other children! (Termination of pregnancy)”. Women who have already had a boy, are afraid of having another boy and have a preference for a girl. In fact, the pressure to have a boy is not so much about the costs of education and upbringing, but about the unwritten conditions for entering into marriage when the son becomes an adult. Despite their desire to have a “son and a daughter”, women prefer to terminate a pregnancy if they are unsure of the sex of the child. N3: “A son and a daughter are the best condition. However, with one son and one daughter, it’s so hard to raise. I have many friends who have two sons, it’s horrible! (Termination of pregnancy)”. N6: “I don’t want to have another boy, the point is that two boys are too much of a burden, you can see that he will get married (later), you need to buy a house (for him in the future before he gets married)! (Termination of pregnancy)”.

In marriage and family, women take on multiple roles. Due to gender differences, women must devote more time to child-rearing and family care. When they suddenly learn of pregnancy, they need to add the role of a pregnant woman and nursing mother to their already balanced roles. N15, N28: “I have a job, and babysitting is not my full-time job. If I have another baby, I might have to waste two years, at least two years of stopping. I mean I can’t work that hard. (Termination of pregnancy)”. N10, N31, N34: “I just don’t want to have another baby, I already have a lot of things to do when I have one, and if I have another one, I have to start all over again, which is too much trouble. (Termination of pregnancy)”. N3: “If I have another baby, it’s better to change my job, because we are exposed to electronics and experiments, and we are afraid that it will be bad for our fetus. (Termination of pregnancy)”. N2: “I’m too busy at work, I’ve just been promoted to the position of management and it’s quite difficult to take a break all of a sudden. (Termination of pregnancy)”. Several other patients also reported the same conflicts.

Having a child requires a significant financial and time commitment, and when women find it difficult to have another child, they would turn to the support system of a co-parenting family first. N9, N33: “If there was one thing worry-free in terms of finances and having someone to take care of the baby, to share it, I would choose to have it. (Termination of pregnancy)”. From the biological, psychological, and social medical model, strong family support can spare women the worries of having another child. N19: “Bringing up a child needs a lot of time. At least someone has to be with the child, it even can’t be settle with one person alone to take care of the child. Luckily my mother is still young and can still give me a hand. (Termination of pregnancy)”. N17: “Now my mother-in-law (helps me) takes care of my son, and when my mother-in-law goes back (to her own house), my mother comes to help me. So, I don’t even have to worry about taking care of the baby. (Continuation of pregnancy)”. However, when the parents help to care for the baby, they would lack leisure time. Two generations have different ideas of education which would bring many problems for us. N15: “My mother-in-law is quite playful and can’t devote herself to babysitting because she would go out to play for a while whenever she finds the opportunity. (Termination of pregnancy)”. N9: “I had already told her that the child was hot, but she still tried to put the quilt on the child, and I had no experience of taking care of children at that time, leading to measles in the child for the puerperium. She is stubborn and we cannot live together. (The pregnancy was terminated)”.

Childbearing is something that husband and wife have to face together. Married and parous women with unwanted pregnancies began to recall their husband’s involvement in the past child-rearing process. Widowhood parenting is the biggest pain point in childbirth, and married women with children will not choose to have other baby if they feel they need to do it alone. N5: “I don’t want to have any more children, it’s too stressful to bring up children, I brought up my first (child) all by myself, I had no one to help me. My husband worked, he went out early (in the morning) and came back late (at night). (Termination of pregnancy)”. N15: “Men are all the same, we can’t count on them (to help bring up children together), so I can’t continue the pregnancy now. (Termination of pregnancy)”. Men’s directly expressed attitudes towards having more children were also a crucial influence on fertility decisions. N23: “My husband told me that he did not want to have any more children (Termination of pregnancy)”. N7: “My husband is very unsupportive and now if I have the child then I have to bear all the hardships by myself. (Termination of pregnancy)”.

Married and parous women with unwanted pregnancies have specific views and opinions on fertility, and their cultural backgrounds and past experiences can influence fertility decision-making. For historical reasons of the One-Child Policy, the separated Two-Children Policy and the comprehensive Two-Children Policy, individuals and families have developed the mind of having fewer children [10]. N1: “It’s impossible to have another baby because I already have two babies, so I can’t have any more. If the baby is born, she would belong to the population of extra-birth. How could the subsequent problems be solved? (Termination of pregnancy) ”. N11: “I had an unplanned pregnancy two or three years after I had my first child, and I couldn’t have another one even if I wanted to, as it was not the period of the Two-Children Policy. (Termination of pregnancy)”. The national fertility policy was once a legal red line to prevent too many newborns and excessive procreation. Although China has now implemented the three-child policy, the gradual liberalization of the fertility policy has not yet played a substantial role in promoting birth. N22: “Nowadays, the normal family will not have any more children after having two, what is the use of having so many children? Anyway, I won’t have any more. (Termination of pregnancy)”.

Women’s views on childbearing are influenced by the views of their relatives and friends and are a combination of various views. N7: “My friends told me, ‘You have two (children), it’s hard enough bringing them up. Don’t have any more’. (Terminating the pregnancy)”. N18: “My friend is pitiful for me, and advised me not to even think about having a second child because it’s too hard to carry a child for everyday life. (Terminating the pregnancy)”. For women who already had children, the acceptance of the upcoming baby by their existing children is also an important factor in shaping women’s fertility decisions [21]. Pregnancies are terminated for fear of causing mental unwellness due to the child’s psychological inability to accept the new birth. N2: “I wanted to have another baby, but my daughter refused to. She said ‘I’m unhappy if you have [the baby]!’ And bad emotions show up. She thought, ‘No one can steal mommy and daddy from me.’ (Termination of pregnancy)”.

The central question on the minds of married and parous women with an unwanted pregnancy is the meaning of having another child, i.e. “What is the purpose of having a child?”. The traditional view of childbearing as an obligation and the pursuit of a male child persisted. However, some did not care about the sex of the child, indeed simply loved it. N16: “I had not thought I would have a baby so soon, so it would be good to finish the task of having babies early. (Continued pregnancy)”. N20: “Because we have a daughter, I want to have another (child) and see if I can have a boy (laughs sheepishly). (Continued pregnancy)”. N18: “It’s good to have another (little child). It’s cute, it’s good to have a child for the company at my age. (Continued pregnancy)”. For women who have already had children, the meaning of having another child is mainly from the perspective of having a partner for the first child. N16: “It’s a good idea to have two children with a partner for each other. Two children are just right, regardless of gender, I feel that to be born a boy or a girl is the same in the current social environment. (Continued pregnancy)”.

Some married and parous women have plans to have another child before the unwanted pregnancy, but the planned time is later than that actual pregnancy, and pregnancy termination by induced abortion becomes a method of birth interval. A second pregnancy within a short period after a woman gave birth can not only affect her health but can also cause poor fetal growth and development. Pregnancy consumes energy and makes women take less care of their existing children, which can lead to guilt for the young existing child. N15: “The plan was to have a second child, but (I) didn’t (think about having) one so soon, I wanted to have another two years later. (Termination of pregnancy)”. N16: “I feel a burden in my heart because my child is still so young, who I may not be able to take care of as I am pregnant, and it made me feel guilty. (Continuing the pregnancy)”.

The grandparents in the family are the main caregivers, but the long hours of care can be too much for them. Married and parous women know how hard it is to bring up children and do not want to add the burden of their elders by having more children. N12: “When I had the first baby, I resigned to babysit which was also helped by my mother-in-law. But my mother-in-law is not in the best of her health and it’s not easy for her to bring up my son. (Termination of pregnancy)”. The growth of children is also accompanied by the gradual ageing of grandparents, who will face the problem of old age. Married women who have had children are also aware of the fact that their parents will need to be taken care of. N10: “My parents are healthy now and will need to be taken care of in the future. But if we have another baby, we will have no more time and energy to care for both patients and children. (Termination of pregnancy)”. N15: “My mother just had a hysterectomy not long ago and she is not in a good health condition. So, in fact, she is not in a good health condition to take care of a child, because the baby has to be carried in arms until it is one-year old, which cannot be settled by my mother. (Termination of pregnancy)”. The details of other patients are given in Table 1 and summary of responses to interview is shown in Fig. 2.

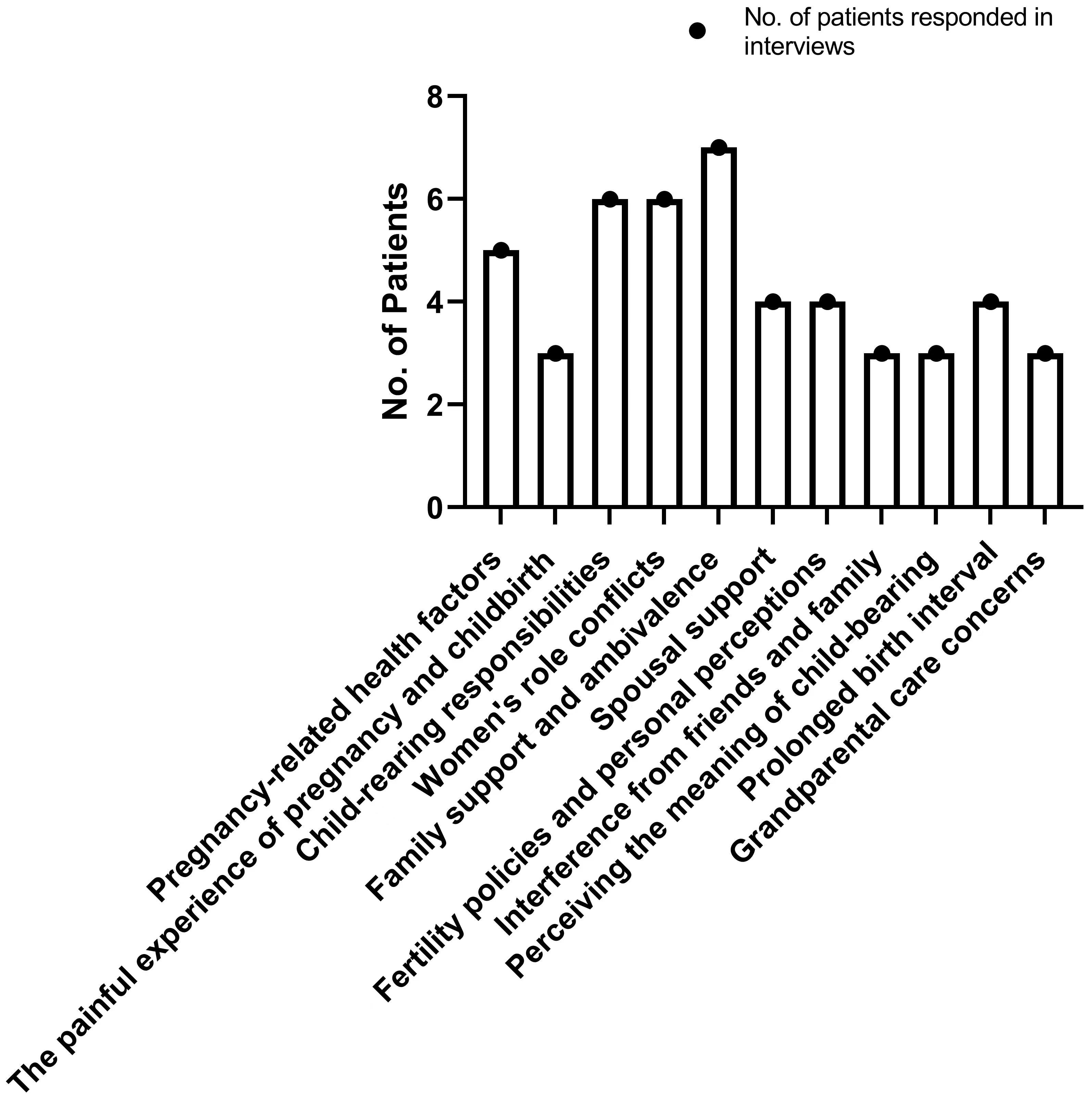

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.The graph represents general overview and summary of patients interviewed in this study. Number of patients are mentioned along with stress responses to fertility.

Based on the Lazarus Stress Coping Model [22], this study uses a rooted theory research approach to explore the inner experiences of married and parous women’s unwanted pregnancy coping process through semi-structured interviews, three-level coding, and constant comparison, rooted in the current socio-cultural context of China, to construct a stress-coping model. Maslow identified the need for security as the second level of need after physiological needs, which refers to the need to feel safe by wanting to be protected and free from threats [23]. Married and parous women with unwanted pregnancies go through the stages of identifying the stressors of reproduction, evaluating their ability to cope with it, and making decisions about reproduction. The fertility decision for married and parous women is a complex and risky budgetary process of weighing up the pros and cons. Unwanted pregnancies are like life going off track, and when women feel that their security of life is threatened, they would terminate the pregnancy to bring their lives back under control. The theoretical model developed in this study will provide a theoretical basis for coping with the stress of unwanted pregnancies among married and parous women. In the further intervention study on promoting the continuation of unwanted pregnancies among married and pregnant women, fertility policy is only one factor, while we also need to consider other aspects, such as fetal health, economic factors, and social support.

The complexity of factors influencing fertility decision-making among married and parous women with an unwanted pregnancy and the difficulty and deliberation of the fertility decision-making process are similar to those of Brauer et al. [24]. Whether the pregnancy continues or not, women are eager to make the right choice about their unwanted fertility decision, and it is a positive coping and help-seeking process. Any form of contraception has the probability to fail, and abortion restrictions do not reduce the number of abortions, but only increase the rate of unsafe abortion [25]. Trying to control the rate of unwanted pregnancy terminations cannot rely on a tightening of pregnancy termination by induced abortion. It has been pointed out that a relaxed fertility policy will not necessarily usher in an increase in fertility [26], but that fertility policy acts as a red line for fertility, and that the country needs to continue to relax its fertility policy to meet the varying demands of fertility intentions.

Women give high priority to eugenics. Lacking pre-pregnancy preparation, women with unwanted pregnancies suspect that they have been exposed to drugs that have teratogenic effects on fetal growth and development before pregnancy. Previous study states [27] that the high perception of teratogenic risk among pregnant women may cause terminations of pregnancies. The physiological and psychological stress of unwanted pregnancies among married and parous women is more evident and requires more attention from healthcare professionals, especially in the face of public health emergencies, who should respond promptly to the effects on the pregnant woman and the fetus and provide the right answers [28, 29]. The health care system should be able to provide the right answers and responses. To promote the development of “precision medicine”, to increase the number of eugenic counselling services for women with unwanted pregnancies, and to increase the detection and prevention of birth defects by “precision medicine”.

With the development of the market economy, and under the influence of the single-child policy for more than 30 years, people’s fertility attitudes changed, and the traditional fertility concepts of “more children, more happiness” and “preference for sons” no longer occupy the main position. As Feng XT [30] points out, urban women’s main reason for having a second child is to give birth to a child and give the child a companion under the comprehensive Two-Children Policy. The decision to have children is not only a quantitative one, but also a gendered one, with women seeking to have two children, which is consistent with national fertility data, but with the ‘fear of two boys’ caused by misconceptions about marriage, which in turn becomes a disincentive for married and parous women to continue unwanted pregnancies. This is consistent with national fertility data [31, 32]. The social chaos of high bride prices and the need to have a house to get married should be abandoned. The role of media should be fulfilled, such as film and television works. Social image publicity and guidance of advocating early childbearing of appropriate age should be promoted in a way that contemporary women like to accept. The publicity of the benefits of having brothers and sisters for children should be encouraged, guiding the society with the correct understanding of childbearing and a positive view of childbearing.

Focusing on women’s experience of pregnancy and childbirth, promoting the implementation of labor analgesia, reducing the discomfort of pregnancy and childbirth, and increasing women’s willingness to have children again [29, 33]. The work-family conflict is a challenge for women in the workplace, especially for women who have unwanted pregnancies. Modern women are increasingly concerned with realizing their values. We should also work to develop family-friendly workplaces and implement a special initiative to provide inclusive childcare services to optimize the maternity environment so that women can return to work without fear. Post-abortion care services are attempting to be improved, and humanistic care is being increased. Besides, women with unwanted pregnancies are also provided with psychological comfort and guidance to ease their psychological burden. Abortion is a risk factor for secondary infertility, and as the number of abortions increases, so does the risk factor for secondary infertility and the time required to treat it [34, 35]. The risk of secondary infertility and the time required to treat it increases with the number of abortions. The high rate of unwanted pregnancies within two years of delivery among married and parous women in China, whether ending in termination or continuation of the pregnancy, will have a negative outcome for the mother or the fetus [36, 37, 38]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to provide scientific family planning services to women who do not plan to have children within two years. By promoting contraceptive information and education, and implementing long-lasting reversible contraception, to protect women’s reproductive health and achieve the preservation of reproductive function.

As married and parous women with unwanted pregnancies are more concerned about the burden of raising and educating their children, we need to build a comprehensive childcare service system to promote a virtuous cycle of family childcare. Despite the full implementation of the Two-Children Policy and the introduction of the Three-Children Policy, many families still do not put the birth of a second child on their agenda due to the high cost of childcare [39]. This is a very important issue. We need to rationalize the market price of childcare, optimize maternity healthcare, increase maternity allowances, and consider special tax deductions for child education and upbringing expenses to reduce the financial burden of childcare. According to research by Ren et al. [40], the quality of marriage can increase women’s willingness to have children, and couples can increase their emotional interaction and communication by caring for their children together, which helps to improve their relationship. Therefore, it is important to encourage men to participate in the childcare process to increase the overall responsibility of couples for childbirth in the family [41, 42]. The study also suggests that support from within the family and society can be effective in reducing the pressure on women to make fertility decisions. Married and parous women’s unwanted fertility decisions are less influenced by the traditional ‘heirloom’ mentality and tend to be more rational. As Tang MJ’s research [43] shows, caregiving issues directly influence fertility decisions. In the context of smaller and more mobile families, there is a shortage of qualified caregivers, and continuing a pregnancy to have another child means doubling the task of childcare. However, health factors and the ageing of grandparents make them incapable of caring for children in the future, and they may even become the ones who need to be cared for, deterring women from taking the risk of continuing a pregnancy. According to Xu et al. [44], while we encouraged retired elder members to share the burden of childcare, it is also important to respect their lifestyles and emotional needs to promote a virtuous cycle of childcare. Some women with one childbearing financial problem and worry about expenses and they want to have another child however their stress of expenses retract them to have more children. On the other hand, some women have 2 children, and they also want to have more, but governmental policy is a big step to bear another child while several women having two child make it difficult for them to spare enough time for further extending the family. There is still a need to carry out such studies with large number of patients, which could possibly further enrich the underlying outcomes and parameters, as our study is limited to small number of patients. The increase in the number of social care and childcare institutions and the construction of a childcare service system with Chinese characteristics allow the elderly to have a sense of security and a sense of care, enriching the social support system and alleviating families’ concerns about having children again and the burden of care.

The factors influencing the decision whether to have a child or not with unwanted pregnancy among married and parous women are complex, and are not only related to fertility policies, but also social support, medical care, family sharing and other forces, requiring the joint efforts of society, medical care, families, and couples to ensure that married and parous women feel secure in having another child. The current study’s limitation is the small number of patients we included. By creating a healthy and positive fertility environment for society, the internal drive to have more children can be enhanced, thereby reducing the rate of unwanted pregnancy termination among married and parous women, and promoting balanced population development.

The data used to support this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conceptualization, WS; Formal analysis, YZ, AJ and JC; Funding acquisition, JZhou; Investigation, JZhou; Methodology, YZ, AJ and WS; Project administration, WS; Resources, WS; Software, JZhu and JC; Validation, YZ, JZhu, JZhou, YL and WS; Writing – original draft, YZ, AJ, JZhu and WS; Writing – review & editing, YZ, JZhou, JC, YL and WS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University [Approval No. (2021) Research Approval No. 007]. Written and informed consent was obtained from all participants of this study.

Not applicable.

This project was funded by: Suzhou Science and Technology Plan Project, Mechanism of SIK2 Phosphorylation of MYPT1 Regulating Metastasis in Ovarian Cancer (No. SYS2020106).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.