†These authors contributed equally.

Academic Editors: Michael H. Dahan and Bo Sun Joo

Background: The present study focuses on examining the association between attachment pattern, anxiety and perceived infertility-related difficulties of women with fertility concerns. Also, the study explores the moderating role of attachment in the relationship between infertility duration and perceived difficulties, but also in the relationship between anxiety and infertility difficulties. Methods: Our study is a descriptive, correlational one. Quantitative data was used, employing transversal and quantitative analysis, thus proving the study to be an experimental one. Survey data was obtained from a total of 240 women with fertility problems (N = 240), aged between 22 and 46 years old (M = 32.71, SD = 4.85). Results: Results show that participants with a pattern of secure attachment had obtained lower scores on state anxiety, trait anxiety and the difficulties scale compared to those with an avoidant one. Also, women that had undergone repeated in vitro fertilization procedures had significantly higher avoidant attachment scores than those that had undergone a single treatment procedure. Another important result is that avoidant attachment moderates the relationship between trait-anxiety and the global difficulties perceived by infertile women. Conclusions: The results of the study show that women can be deeply affected by failed fertilization attempts and repeated miscarriages; as a consequence, they might feel powerless because they cannot become mothers, which leads, over time, to feelings of anxiety, depression, especially when they do not benefit from social support and have not developed resilience mechanisms.

Worldwide, many couples struggle to have a child; in some cultures it is regarded as an important factor in marital life and, consequently, infertility is considered a major life stressor. Infertility is described as the inability to conceive after having unprotected intercourse after at least one year [1].

Researchers discovered that psychological distress is common in couples with fertility problems, the most frequent being anxiety and depression [2, 3, 4].

The psychological wellbeing of infertile couples is a medical issue that is gaining popularity nowadays. Both partners are important, and more effort should be spent in reducing gender-specific differences [5].

The integration of scientific knowledge with gender-specific determinants has brought out some crucial points of intervention: the need to implement information interventions on preventable causes of infertility; customize diagnostic pathways to identify specific causes of male infertility to cure it rather than bypass its effects; analyse the couple simultaneously; and use assisted reproductive technology according to the criterion of graduality. Including the gender dimension throughout the diagnostic-therapeutic journey of infertile couples helps eliminate gender bias, indicating how to design equitable access to infertility diagnosis and treatment [6].

Burgio et al. [7] realised a systematic review and the analysis of the results presented in the studies identified nine main topics falling within psychological and social variables implicated in infertility. The first ones included anxiety, depression, stress, and coping strategies; the last ones included maternal-infant attachment, parental role, QOL, and family functioning. Finally, the pregnancy rate was studied as a measure of intervention efficacy.

Studies have shown that women have higher rates of stress levels associated with infertility compared to men, more than half regarding infertility as one of the most stressful experiences [3, 8].

Benyamini et al. [9] described five factors related to difficulties experienced by women, by taking into account the type and area of impact: impact on self and spouse, uncertainty and lack of control, family and social pressures, treatment-induced problems and treatment-related procedures.

Impact on self and spouse takes into account the lack of spontaneity in the sexual relationship of the couple, the worry that the medical treatment will cause physical effects at some point, the impact of the fertility issue on the way not only women see themselves, but also on the way both partners view themselves.

Uncertainty and lack of control refers to the lack of control over their life, uncertainty with regards to the future and their monthly anticipation of the results of their treatment.

Family and social pressures involve the questions and social pressure about childbearing, including the questions and family pressure about this issue.

Treatment-induced problems describe the physical discomfort and pain involved in the treatment, while the economic strain and treatment-related procedures include the bureaucratic procedures related to the medical services, the changes in functioning at work, also the relationship with the medical staff.

Various studies view infertility as a stressful experience that can activate attachment models [10]. A person’s attachment pattern is thought to affect the way they respond to emotional suffering [11]. In the last 30 years, attachment theory became an important conceptual framework for understanding human relationships. According to this theory, early experiences with a responsive or unresponsive caregiver give a positive or a negative model regarding caring and attending to the needs of other people [12].

Researchers have studied how attachment impacts the perception of people about their romantic partners [13]. Furthermore, research repeatedly confirmed that two relatively unrelated patterns, namely avoidant attachment and anxious attachment, showcase individual differences in romantic attachment among adults [14].

So far little attention has been paid to exploring the role of attachment patterns of couples that struggle with infertility. In addition, attachment patterns can influence the well-being of people involved in assisted reproductive procedures.

Anxious attachment involves fear of rejection or abandonment, need for approval from others and emotional stress when the partner is not available. The interpersonal pattern of people with anxious attachment consists of attempts to control their anxiety by reducing emotional distance and needing constant reassurance of support and love from others.

Avoidant attachment involves fear of codependence and intimacy, an excessive need of self-confidence and reluctance to self-disclose. With regards to their interpersonal pattern, they consider that others are not trustworthy enough to care for them without causing them pain. As a consequence, they avoid having relationships with others in order to maintain control and their independence [15]. Studies show that infertile people with a secure attachment have lower levels of stress, a better mood and higher marital satisfaction compared to infertile people with anxious or avoidant attachment.

Amir et al. [16] suggested that a secure attachment (low levels of anxiety and avoidant attachment) is a moderator for psychological well-being and an important resource for people involved in a fertilization procedure. Moreover, the results of the study undertook by Bayley et al. [17] showed that anxious attachment in both men and women correlated with fertilization related stress, and Van den Broeck et al. [18] found that anxious attachment predicts emotional stress in couples that begin their first assisted reproductive treatment.

The present study focused on examining the association between attachment pattern, anxiety and perceived infertility-related difficulties in women with fertility concerns. Therefore, our specific aims were:

(1) to explore if there are differences between participants with different attachment patterns in terms of anxiety and difficulty scale scores;

(2) to investigate if women who have repeated fertilization procedures have higher scores on anxious and avoidant attachment patterns than those who have not started yet treatment or are at the beginning of it;

(3) to investigate if anxious/avoidant attachment moderates between infertility duration and perceived global difficulties;

(4) to explore if anxious/avoidant attachment moderates between state/trait-anxiety and perceived global difficulties.

According to the stated objectives, we have formulated the following hypotheses:

H1: There are differences between participants with different attachment patterns in terms of anxiety and difficulty scale scores.

H2: Participants who repeat fertilization procedures have higher scores on anxious and avoidant attachment patterns than those who have not yet started treatment or are at the beginning of it.

H3: Attachment pattern moderates the relationship between the duration of infertility and the perception of global difficulties.

H4: Attachment pattern moderates the relationship between anxiety as a condition/ anxiety as a trait and the perception of global difficulties.

The present study is a descriptive, correlational one. The study is a non-experimental one, because quantitative data was used, employing transversal and quantitative analysis.

The dependent variables are the scores obtained by participants at the difficulties, anxiety and attachment pattern questionnaires, while the independent variable is the duration of infertility. Age, gender, marital status, infertility type, stage of treatment and education level represent covariables.

This study started in October 2019, after receiving approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Bucharest. It lasted until December 2019 and the ethical principles of anonymity and confidentiality were respected; in addition, every participant was informed about the purpose of the study, data collection and their rights, while expressing their consent to be involved in the study before receiving the questionnaires.

A number of 240 Romanian infertile women from different cities responded to announcements posted on social media, which invited them to take part in scientific studies that aimed to make psychological evaluations of infertile women. The questionnaires were administered online through the Google Form platform. Among the criteria for inclusion in the study were the age of at least 18 years at the time of evaluation and medical diagnosis of infertility.

Every participant completed various scales and questionnaires:

(a) The Difficulties Experienced Scale [9] comprises 22 items, scored on a

5-point Likert scale (from 1-Total disagreement, to 5-Total agreement). The

questionnaire comprises 5 subscales: “Uncertainty and lack of control” (6

items), “Family and social pressures” (5 items), “Impact on self and spouse”

(6 items), “Problems induced by treatment” (2 items), “Procedures related to

treatment” (3 items). The fidelity coefficients for the present study are the

following:

(b) State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-Form Y) [19]. Anxiety Scale (STAI-Form Y) is a frequently used questionnaire for measuring anxiety status. The items of the STAI instrument (40 items) are grouped on two scales: the State-Anxiety (S-Anxiety: assesses current anxiety (subjective feelings of tension, mistrust, nervousness and worry). Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 (Not at all anxiety-free) to 4 (Very high anxiety), and ten items require reverse scoring) and the Trait-Anxiety (T-Anxiety, which measures anxiety as a general trait, refers to the general tendency to feel anxiety in threatening situations from the environment. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 (Almost never-lack of anxiety) to 4 (Almost always-high anxiety); out of all the items, nine require reverse scoring).

The Cronbach alpha internal consistency coefficient for the current study is 0.94 for the State Anxiety and 0.78 for the Trait Anxiety.

(c) The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale-Short Form (ECR-S) [20], which measures maladaptive attachment in adults that are involved in a romantic relationship and includes 12 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1-Strong disagreement, to 7-Strong agreement). The results consist of two scores for the two separate factors: anxious attachment (6 items, of which one item requires reverse scoring) and avoidant attachment (6 items, three of which require reverse scoring). The minimum score for each subscale is 6, and the maximum score is 42. The coefficient of internal consistency for this study is 0.74, and for each subscale: 0.62 (Anxious attachment) and 0.70 (Avoidant attachment).

In addition, the participants also offered information about infertility (duration, cause of infertility, type, being involved in fertilization procedures—if so, they mentioned the number of fertilizations), and socio-demographic details related to age, marital status, education level.

For data processing and analysis program IBM SPSS Statistics (Romania for Windows, version 25, Bucharest, Romania) were used. The distributions of the quantitative variables were not Gaussian, so we applied only non-parametric tests.

For the first two objectives, we applied the Kruskal Wallis test and Bonferroni correction post-hoc tests and we summarized the results as a median score (minimum value–maximum value).

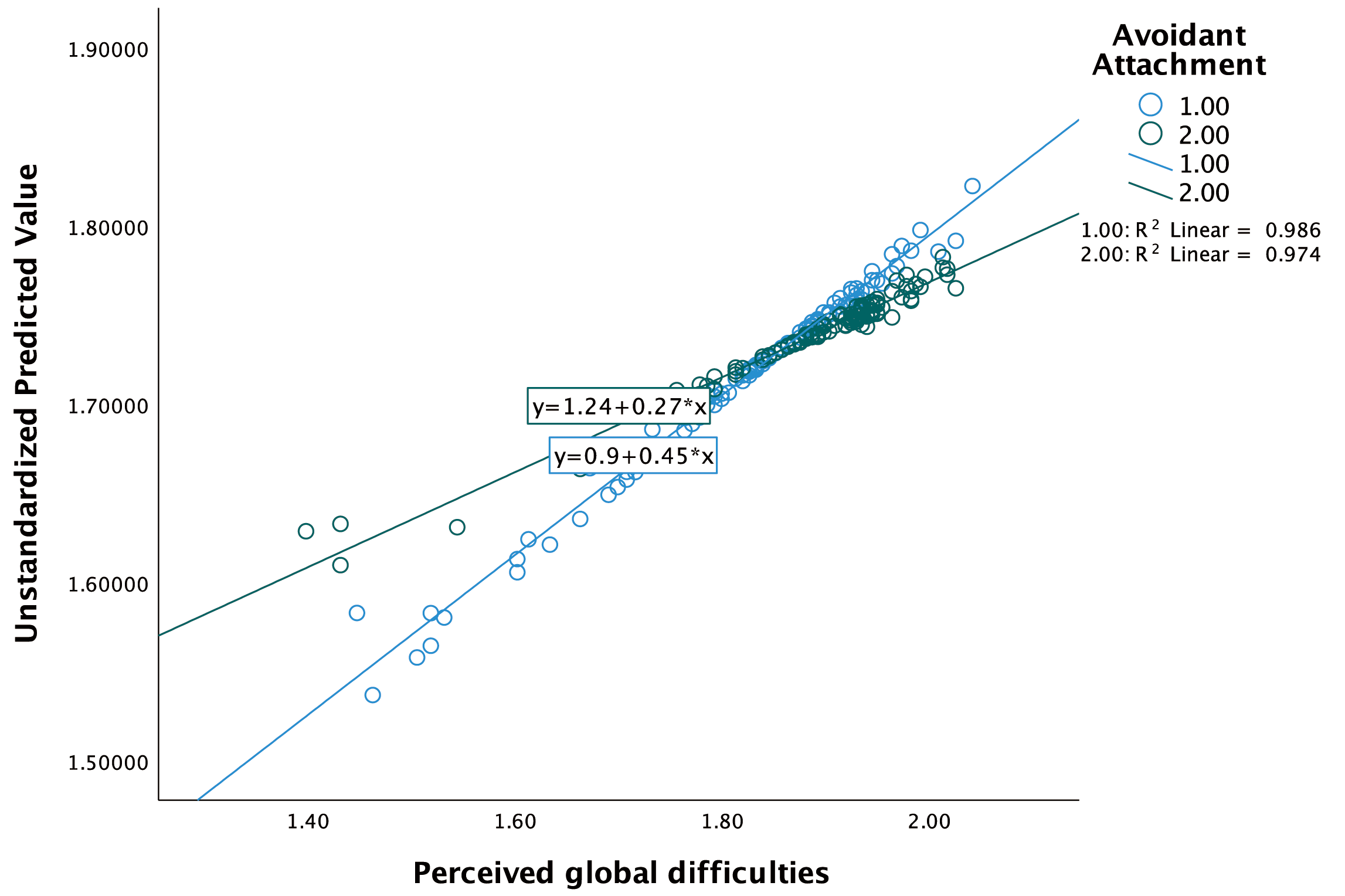

For the Moderation analysis linear regression analysis was used with trait-anxiety as dependent variable and covariates perceived global difficulties and interaction between perceived global difficulties and avoidant attachment. In order to visualize the moderation effect, scatter dot plot graph was computed by transforming the continuous avoidant attachment variable into a binary variable, having mean as threshold.

Survey data were obtained from a total of 240 women with fertility problems (N = 240). Women are between 22 and 46 years old (M = 32.71, SD = 4.85).

With regards to the independent variable—the duration of infertility, 43 participants (17.9%) stated that they face fertility problems for less than 2 years, 104 participants (43.3%) have difficulty conceiving a child for 2–5 years, and 93 participants (38.8%) face an infertility duration of more than 5 years. Concerning the type of infertility, in 158 cases (65.8%) the infertility is primary, and in 82 cases (34.2%), the infertility is secondary. The cause of infertility is female in 88 cases (36.7%), male in 41 cases (17.1%), both male and female in 60 cases (25%) and unexplained in 51 cases (21.3%). Regarding IVF treatment, 101 (42.1%) participants have not yet had treatment for their fertility problem, 40 (16.7%) have received only one treatment so far, and 99 participants (41.3%) have received more fertilization treatments (Table 1).

| N = 240 | |||

| Age, years (mean) | 33 (SD = 4.8) | ||

| Frequency | Percentage | ||

| Education | |||

| Elementary school | 7 | 2.9% | |

| High school | 30 | 12.6% | |

| Post-secondary school | 26 | 10.8% | |

| Without bachelor’s degree | 7 | 2.9% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 110 | 45.8% | |

| Postgraduate degree | 60 | 25% | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 214 | 88.8% | |

| Live with a partner | 25 | 10.4% | |

| Preferred not to answer this question | 1 | 0.8% | |

The Kruskal Wallis test and post-hoc tests with Bonferroni corrections were

used; the results showed statistically significant differences (p

In addition, there are significant differences between groups regarding the

scores on the global difficulties scale (the Kruskall-Wallis test was used,

p

The Kruskall-Wallis test was used (p = 0.114), revealing no statistically significant differences concerning anxious attachment pattern and repeated treatment.

On the other side, there were differences concerning avoidant attachment pattern on patients that had repeated fertilization procedures (test K-Wallis, p = 0.02). Post-hoc analysis revealed that patients that had undergone repeated in vitro fertilization procedures—median 1.11 (0.78–1.53) (p = 0.033) had significantly higher avoidant attachment scores than those that had undergone a single treatment procedure—median 0.90 (0.78–1.43).

To test the third hypothesis that aims to investigate if anxious/avoidant attachment moderates between infertility duration and perceived global difficulties, a series of moderation models were tested. The R square value for the interaction models was statistically insignificant. These results indicate that attachment pattern does not moderate the relationship between infertility duration and perceived difficulties.

The last hypothesis aims to investigate if anxious/avoidant attachment moderates between state/trait-anxiety and perceived global difficulties. A number of moderation models were tested for the relationship between state/trait anxiety and the perceived global difficulties with attachment pattern. Only the following model was statistically significant (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Moderation model: Avoidant attachment as moderator in the relationship between trait anxiety and the perceived global difficulties.

Avoidant attachment moderates the relationship between trait-anxiety and the global difficulties perceived by infertile women. A hierarchical regression was performed on trait-anxiety with perceived global difficulties and avoidant attachment in block 1, and the interaction variable in block 2. The R square value for the interaction model was 0.27 statistically significant (Beta = –011; F (2.237) = 45.491; p = 0.013).

To find out how the moderation effect manifests itself, it was analyzed the level of trait-anxiety in relation to the upper and lower values of the avoidant attachment, as well as the scatter-plot graph (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Scatter-plot graph on the moderation effect formatting.

Thus, the moderation effect for the tested model is manifested by enhancing the relationship between trait-anxiety and perceived global difficulties, when the avoidant attachment has higher values.

The present study focused on examining the association between attachment pattern, state anxiety, trait anxiety and perceived infertility-related difficulties in women with infertility diagnostic.

The results of the study show that participants with a pattern of secure attachment had obtained lower scores on state anxiety, trait anxiety and the difficulties scale compared to those with an avoidant one. For example, Elyasi et al. [21] showed that secure attachment pattern can effectively boost the ability to accommodate with stressful conditions such as infertility. This can explain the lower level of distress in infertile couples with a secure attachment pattern. These findings are in line with the results of Donarelli et al. [22], suggesting that infertile women that have high levels of attachment avoidance feel higher infertility related stress, including from a social and relational perspective.

Also, women that had undergone repeated in vitro fertilization procedures had significantly higher avoidant attachment scores than those that had undergone a single treatment procedure. Donarelli et al. [23], found that the patterns of attachment (i.e., anxiety and avoidance) significantly correlated with infertility-specific distress. There had been significant relationships between anxiety and infertility-specific distress and avoidant attachment pattern.

Women can be deeply affected by failed fertilization attempts and repeated miscarriages; as a result, they feel increasingly powerless in the face of reality: not being able to conceive and they keep thinking about their projected child, which leads, over time, to feelings of anxiety, depression, especially when they do not benefit from social support and resilience mechanisms. “The denial of multiple and repeated failures illustrates a complex combination of several unprocessed losses, for which those individuals did not mourn” [24] (page 15). The same author is of the opinion that repeated treatment and non-acceptance of fertilization failures highlight dynamic phenomena of compulsion at repetition. Denying failures to conceive can persist, becoming a long process with unfinished mourning. Past experiences, from childhood or from couple relationships can affect the ability of these women to form secure attachments. Also, their anxiety and ambivalence about motherhood can cause them to postpone the decision to have a child, an option that is detrimental to them once the fertile age range is exceeded.

The results showed that the attachment pattern does not have a moderating effect on the relationship between the duration of infertility and the perception of difficulties, but it has an effect on the relationship between trait anxiety and the perception of difficulties. Previous studies [16] also stated that there are differences between people with different patterns of attachment in terms of adapting to stressful situations, because infertility can be experienced as a state that profoundly changes the infertile person in many ways: cognitive, social and emotional. Renzi et al. [25] presented that several investigations showed that a diagnosis of infertility can lead to emotional distress, anxiety and depression which occur more frequently and with more severity in women with insecure attachment pattern. Moreover, the pandemic Covid19 was a supplementary risk factor leading to emotional distress, anxiety and depression in infertile couples or pregnant women [26, 27, 28].

As the present study is cross-sectional, it is impossible to say whether a secure attachment pattern leads to adjustment and also protects against anxiety and difficulties. Further longitudinal studies should examine these issues. Other limitation is due to the application of self-assessment scales and to the nature of convenience research group. Thus, there is a risk that the data reported by participants will be affected by their capacity for self-knowledge and their tendency towards social desirability. The participants were also volunteers. Because no data are available for women who did not participate, we cannot determine whether they differ from those who participated in the study. Therefore, a limitation of the study is that the research group may be somewhat different from the general population of infertile women.

Despite limitations, the findings expand knowledge in the area of attachment, anxiety and perceived infertility-related difficulties. The present study has numerous strengths that should be considered, including: (a) the examination of anxiety symptoms and difficulties according to certain demographic and clinical characteristics, such as level of education, marital status, infertility type, stage of treatment and duration of infertility; (b) the evaluation carried out in several cities of Romania, unlike other studies that include participants from a single fertility clinic.

Finally, the results of the study have important practical implications for the clinical intervention and psychological counseling of women diagnosed with infertility. Thus, the results of this study allow the development of complex evaluation programs, therapeutic intervention and evaluation instruments specific in the context of infertility. They also lead to the generation of new research ideas, which can be extended to a larger group of participants.

In conclusion, the current findings support the idea that there are significant associations between attachment patterns, anxiety and the difficulties of infertile women in Romania. These results stimulate further research on the psychosocial variables associated with the concept of infertility, to deepen the understanding of the difficulties of women who face this diagnosis and/or are being treated. This study also provides the necessary support for future studies in which the attachment patterns may be predictors of emotional disturbances at different stages of infertility treatment.

Conceptualization—DAI and AEB; methodology—CIP; software—PB; validation—AMP, CG and NG; formal analysis—PB; investigation—NG; resources—DAI; data curation—AEB; writing-original draft preparation—DAI, CG and NG; writing-review and editing—AMP; visualization—CIP; supervision—GP; project administration—NG; software, visualization, writing-review and editing—AB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Bucharest (No 88/24/10/2019). Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients was approved by all authors.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. AMP and NG are serving as one of the Guest editors of this journal. We declare that AMP and NG had no involvement in the peer review of this article and have no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to MHD.

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.