1 Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology at Oklahoma State University-Center for Health Sciences, College of Osteopathic Medicine, Tulsa, OK 74464, USA

2 Department of Physical Sciences, Northeastern State University, Broken Arrow, OK 74014, USA

3 Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, McMurry University, Abilene, TX 79697, USA

4 Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas, Arlington, TX 76019, USA

5 Center for Biotechnology and Genomics, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA

Abstract

Background: Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) is a critical epigenetic regulator involved in chromatin remodeling and transcriptional repression, making it a valuable target for cancer therapy. Selective inhibition of HDAC1 represents a promising approach to cancer treatment, as it modulates gene expression and induces apoptosis in tumor cells.

Methods: Two novel hydroxamate-based HDAC1 inhibitors, compounds 4 and 6, were designed and evaluated using molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and enzymatic inhibition assays. Molecular docking assessed binding interactions, while MD simulations evaluated the stability of the ligand–protein complexes. Enzymatic inhibition assays were used to determine the IC50 values and evaluate the potency of the compounds.

Results: Molecular docking revealed that both compounds exhibited significant interactions with HDAC1, including hydrophobic contacts, hydrogen bonding, and zinc coordination. Compound 4 demonstrated a stronger binding affinity (–6.2 kcal/mol) compared to compound 6 (–5.7 kcal/mol). The MD simulations confirmed that compound 4 exhibited greater stability, with divalent zinc coordination (4.3 Å and 4.8 Å), whereas compound 6 showed weaker monovalent coordination (4.4 Å). Enzymatic assays demonstrated that compound 4 had an IC50 of 2.96 ± 0.4 μM, while compound 6 exhibited an IC50 of 4.76 ± 0.5 μM; thus, compound 4 possesses superior inhibitory potency.

Conclusions: Compound 4 exhibits enhanced binding affinity, stability, and enzymatic inhibition compared to compound 6, suggesting that this compound may serve as a promising lead for the development of selective HDAC1 inhibitors.

Keywords

- histone deacetylase 1

- hydroxamic acids

- molecular dynamics simulation

- enzyme inhibitors

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are key epigenetic regulators that control gene expression by removing acetyl groups not only from histone but also from non-histone proteins. This deacetylation leads to chromatin condensation and transcriptional repression, influencing various biological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [1, 2, 3]. HDACs are broadly classified into four classes based on sequence homology and cofactor dependency: Class I (histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), 2, 3, and 8), Class II (HDAC4, 5, 6, 7, 9, and 10), Class III (sirtuins, which require NAD+ for activity), and Class IV (HDAC11) [4, 5]. Class I HDACs, particularly HDAC1, play a crucial role in chromatin remodeling and oncogenic transformation [6, 7]. HDAC1, a nuclear-localized deacetylase, is an integral component of transcriptional co-repressor complexes such as Sin3, NuRD, and CoREST [8]. It regulates chromatin structure by deacetylating histone tails, thereby repressing gene transcription [9]. Aberrant expression or activity of HDAC1 has been implicated in various cancers, including leukemia, breast cancer, and prostate cancer, where it silences tumor suppressor genes and promotes cell cycle progression [10, 11]. Given its role in tumorigenesis, HDAC1 has emerged as a promising therapeutic target for cancer treatment.

Several HDAC inhibitors (HDACis) have been developed, with five Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs—Vorinostat (SAHA), Romidepsin, Panobinostat, Belinostat, and Pracinostat—primarily used for hematologic malignancies [12, 13]. Recent reviews have particularly highlighted the potential of dual-targeting HDAC inhibitors designed to selectively inhibit specific HDAC isoforms, enhancing therapeutic efficacy while reducing side effects [14]. Additionally, the evolving role of isoform-selective HDAC inhibitors as epigenetic modulators in cancer immunotherapy, especially in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors, has been increasingly recognized [15]. Chidamide, approved in China for peripheral T-cell lymphoma (CHOP) [16], has recently demonstrated promising efficacy in combination with CHOP chemotherapy regimen, which consists of four drugs: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. This combination was tested in patients with previously untreated peripheral T-cell lymphoma of the T follicular helper phenotype (PTCL-TFH) subtype and achieved an overall response rate of 85.7% and a complete response rate of 71.4% [17]. These inhibitors function by chelating the Zn2+ ion within the active site of HDACs, thereby blocking their enzymatic activity and promoting histone acetylation, which can lead to apoptosis and differentiation in cancer cells [18, 19]. HDAC1, a key member of the HDAC family, plays a fundamental role in cancer progression by regulating gene expression in cell cycle control, differentiation, and apoptosis. Aberrant HDAC1 activity has been linked to tumorigenesis, as its overexpression is often associated with aggressive cancer phenotypes and poor prognosis [20, 21]. HDAC inhibitors have demonstrated significant therapeutic potential by targeting HDAC1 and other HDAC isoforms to modulate oncogenic gene expression. However, challenges remain due to the broad-spectrum activity of most approved HDACis, which target multiple HDAC isoforms and lead to off-target effects such as hematological toxicity, fatigue, gastrointestinal disturbances, and cardiotoxicity [20, 21]. Additionally, tumor resistance to HDACis has been reported, likely due to compensatory activation of alternative oncogenic pathways or upregulation of drug efflux mechanisms [22, 23]. A recent study highlights resistance mechanisms involving specific molecular alterations in key pathways, such as the E2F1/Rb/HDAC1 axis, influencing drug efficacy [24]. Additionally, the emerging role of isoform-specific HDAC inhibitors and combination therapies has been suggested to potentially overcome such resistance mechanisms, as evidenced by investigations in hematologic malignancies such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [25]. Given the critical role of HDAC1 in cancer biology, further research into HDAC-targeted therapies is essential for improving clinical outcomes while minimizing adverse effects.

Hydroxamate-based inhibitors have gained prominence due to their strong Zn2+-chelating ability, which enhances their potency as HDAC inhibitors [26]. Structurally, hydroxamate HDACis possess a pharmacophoric framework comprising a Zn2+-binding group (ZBG), a linker, and a surface recognition cap [27]. This configuration allows selective binding to the catalytic pocket of HDAC1 while maintaining specificity [28]. Moreover, hydroxamate inhibitors exhibit favorable pharmacokinetics, making them suitable candidates for drug development [20]. This study aims to explore the inhibitory potential of novel dihydroxamate-based compounds against HDAC1 by evaluating their binding interactions, stability, and enzymatic activity through molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and enzymatic inhibition assays. The findings may identify promising candidates for selective HDAC1 inhibition, contributing to the development of epigenetic cancer therapies.

All reagents, including chemicals and enzymes, were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) or other reputable suppliers, with detailed information provided where applicable. Compounds 4 (N-Hydroxy-3-[6-(hydroxyamino)-6-oxohexyloxy]benzamide) and 6 (N-hydroxy-4-(7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl)-3-methoxybenzamide) were initially dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and subsequently diluted to the required concentrations for enzyme activity assays.

Ligand Preparation: The crystal structure of HDAC1 (PDB ID: 4BKX) served as the receptor template. Avogadro software (version 1.95, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), utilizing the General Amber Force Fields (GAFF), was employed to build and energy-minimize the structures for Compounds 4 and 6 [29]. Docking Setup: Molecular docking of each ligand was conducted with AutoDock Vina (version 1.2.7, La Jolla, CA, USA), allowing full ligand flexibility while keeping the receptor rigid [30]. The docking grid was established around the HDAC1 active site, with center coordinates set (–46.756, 16.290, –7.785). Simplified docking parameters were chosen for clarity. Interaction Analysis: The lowest-energy docking poses for each ligand underwent subsequent molecular dynamics simulations. Protein-ligand interactions derived from both the docking results and the final molecular dynamics structures were analyzed using the Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler (PLIP) online platform [31].

All molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were executed using GROMACS software (version 2021.4, Stockholm, Sweden). The simulations employed the AMBER99SB-ILDN force field, which was further adjusted with recently reported parameters specific for zinc(II)-binding residues [32, 33]. These adjustments were essential for accurately modeling the zinc ion coordination in the active site, enhancing metalloprotein stability during MD runs. The SPC/E water model was utilized for solvation, and ligand topologies compatible with GROMACS were generated using ACPYPE software (version v2022.7.27, Cambridge, UK) [34]. Each simulation system was initially solvated, followed by charge neutralization through the addition of three chloride ions. Subsequently, energy minimization was performed using the steepest descent algorithm for 500,000 steps. Equilibration occurred in two sequential stages: first, a 100-ps NVT ensemble run stabilized the system temperature at approximately 300 K using the leap-frog integrator. This was followed by another 100-ps NPT equilibration, also employing the leap-frog integrator, stabilizing the system’s pressure at roughly 1 bar. During both equilibration phases, positional restraints were applied to the receptor and ligand atoms. Temperature control was maintained by the Berendsen velocity-rescale thermostat, and pressure control utilized the Parrinello-Rahman barostat. The final MD production run lasted 100 ns without positional restraints. Two independent replicates for each HDAC1-inhibitor complex were carried out using distinct initial velocity conditions. These replicates facilitated the identification of consistent dynamical behaviors across systems, enabling selection of the most representative simulation for subsequent inhibitor comparisons and analyses. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) values for ligand trajectories relative to the protein backbone were determined using the RMSD calculation module of GROMACS. Additionally, RMSD values of the protein backbone relative to the complex was performed to provide insight into the protein stability throughout the simulations.

The purified HDAC1 enzyme was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK) and used for

substrate activity assays. The enzyme was added at a final concentration of 10

µg/mL to reaction solutions containing 10 to 500 µM Boc-Lys(Ac)-pNA

(N-Boc-Lysine acetyl-p-nitroaniline, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) in 50 mM TBS buffer (Sigma, St. Louis, MI, USA, pH 7.0). Reactions were

conducted in a 96-well plate with a final volume of 100 µL and incubated at

37 °C for 1 hour. Following incubation, reactions were terminated by

adding 10 µL of color developer (trypsin, Sigma), followed by thorough mixing. The

plate was further incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes, after which

absorbance readings were obtained at 405 nm using a 96-well plate reader (Bio-Tek ELx808, Winooski, VT, USA).

Enzymatic activity was monitored by measuring the increase in absorbance at 405

nm, corresponding to the release of p-nitroaniline (

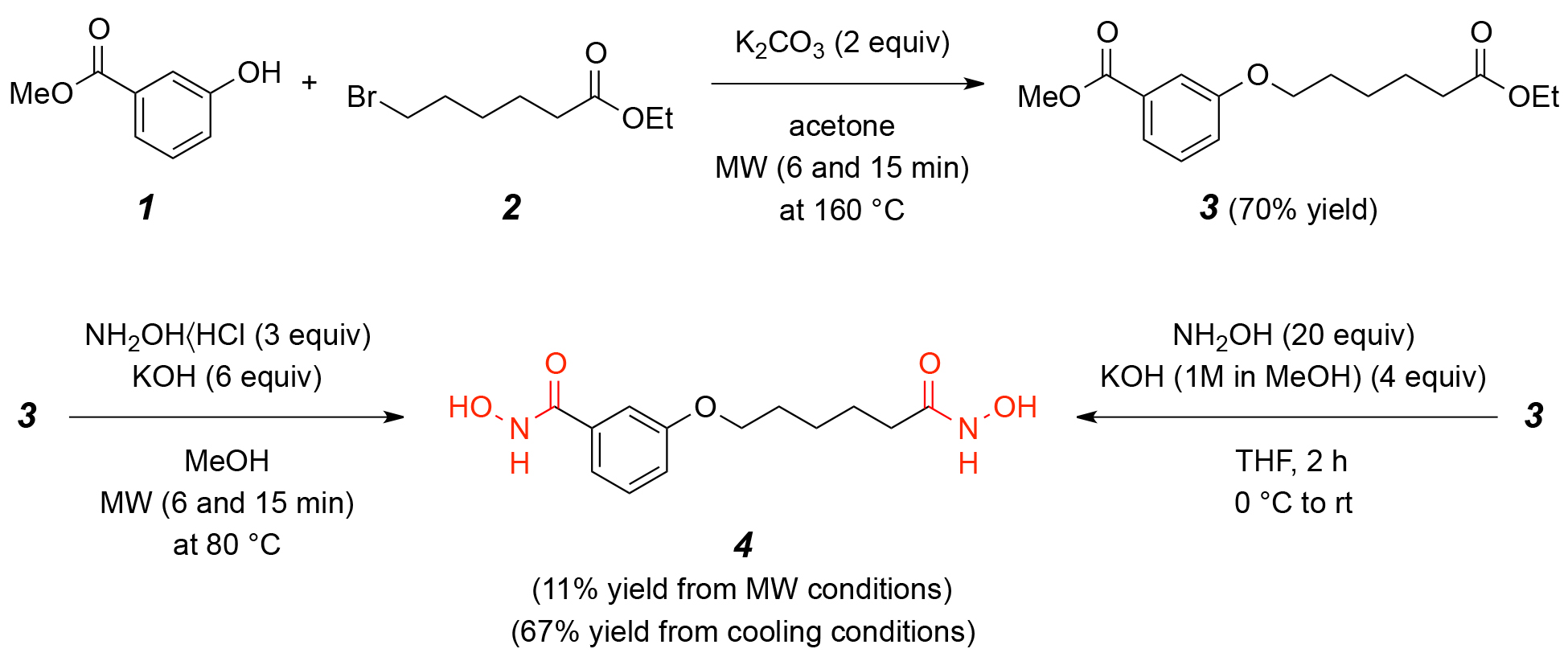

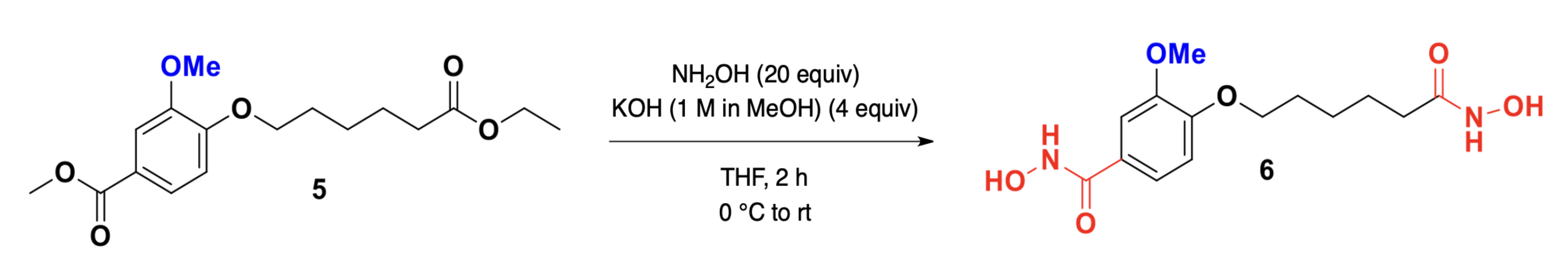

The synthesis of compounds 4 and 6 is essential for developing effective HDAC1 inhibitors, as these compounds contain hydroxamic acid functional groups known to chelate the zinc ion in the active site of HDAC enzymes. The design and synthesis of these molecules aim to optimize their structural features for enhanced binding affinity, stability, and inhibitory potency, as supported by molecular docking and dynamics simulations. Fig. 1 depicts the synthetic pathway for N-Hydroxy-3-[6-(hydroxyamino)-6-oxohexyloxy]benzamide (4). The synthesis begins with 3-hydroxybenzoic acid (1), which undergoes etherification with 6-bromohexanoyl hydroxylamine (2) in the presence of a suitable base, yielding the intermediate 3-(6-bromohexyloxy)benzoic acid (3). Subsequent nucleophilic substitution with hydroxylamine hydrochloride results in the formation of the target compound 4. This reaction sequence involves key transformations, including esterification, halogen displacement, and hydroxylamine incorporation, ensuring the selective introduction of hydroxamic acid functionality. Fig. 2 illustrates the synthetic strategy for N-Hydroxy-4-methoxy-3-[6-(hydroxyamino)-6-oxohexyloxy]benzamide (6). The synthesis commences with 4-methoxy-3-hydroxybenzoic acid (5), which undergoes etherification with 6-bromohexanoyl hydroxylamine under basic conditions to generate 4-methoxy-3-(6-bromohexyloxy)benzoic acid. Subsequent nucleophilic substitution with hydroxylamine hydrochloride affords the final hydroxamic acid derivative 6. By synthesizing and characterizing these compounds, their inhibitory potential against HDAC1 can be experimentally validated, supporting their potential as lead compounds.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The scheme for synthesis of compound 4: N-Hydroxy-3-[6-(hydroxyamino)-6-oxohexyloxy]benzamide. Synthesis of compound 4 via etherification of compound 1 and 2, followed by hydroxylamine substitution to yield N-Hydroxy-3-[6-(hydroxyamino)-6-oxohexyloxy]benzamide. MW, microwave.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The scheme for synthesis of compound 6: N-Hydroxy-4-methoxy-3-[6-(hydroxyamino)-6-oxohexyloxy]benzamide. Synthesis of compound 6 from 4-methoxy-3-hydroxybenzoic acid via etherification and hydroxylamine substitution.

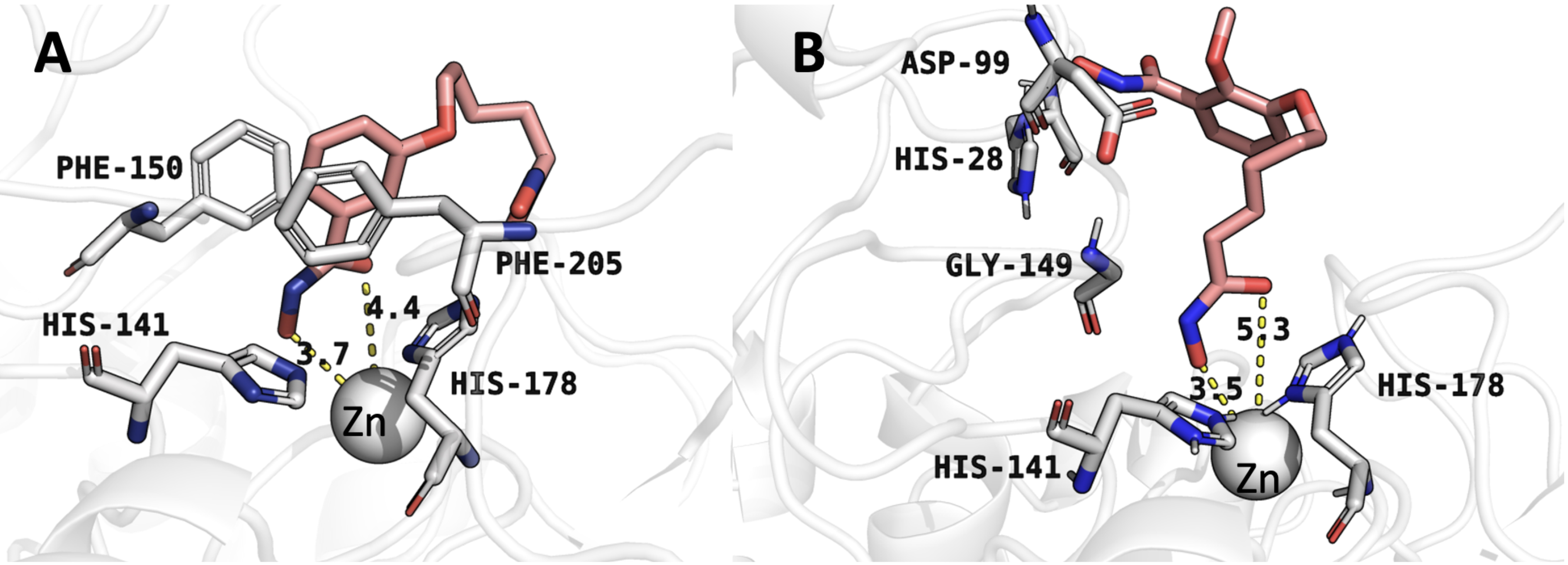

Understanding the molecular interactions of compound 4 with HDAC1 is critical

for elucidating its inhibition mechanism and guiding structure-based drug design.

Molecular docking analysis revealed that compound 4 engages in hydrophobic

interactions, hydrogen bonding, and

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Molecular docking conformations obtained by AutoDock Vina. (A) Binding mode of compound 4 with histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1). (B) Binding mode of compound 6 with HDAC1. Numbers indicate distances (in Å) for critical interactions between the inhibitors and HDAC1 active site residues.

| Inhibitor | Autodock binding affinity (kcal/mol) | End-state free energy of the molecular dynamics (kcal/mol) |

| Compound 4 | –6.2 | –7.7 |

| Compound 6 | –5.7 | –7.3 |

| CI994 | –6.3 | –7.8 |

Molecular docking provides an initial assessment of the binding affinity and

interactions between ligands and target proteins. However, docking alone does not

account for protein flexibility, solvent effects, and the dynamic nature of

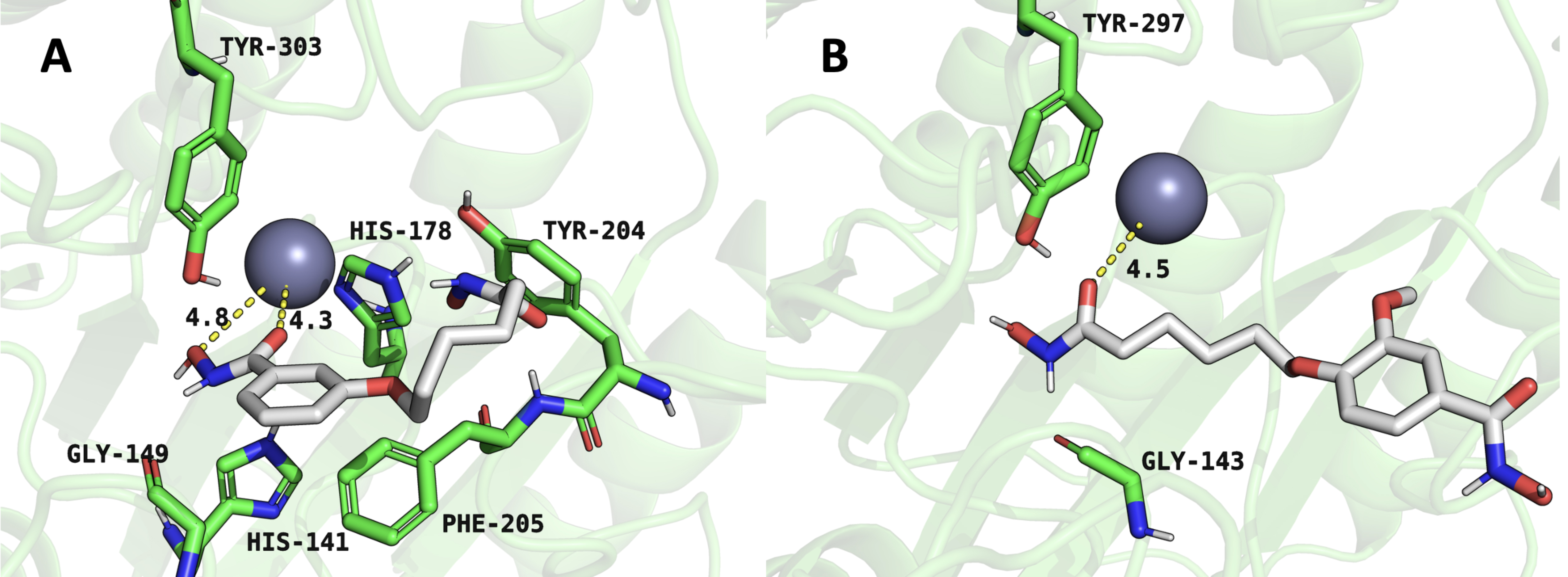

ligand binding. To refine these insights, MD simulations were conducted to

examine the stability, conformational changes, and binding interactions of

compounds 4 and 6 with HDAC1 over time. These simulations help validate docking

results and provide a more realistic representation of molecular interactions

within a biological system. Fig. 4A shows the complex between compound 4 and

HDAC1, where the ligand is stabilized through multiple interactions, including

hydrogen bonding and coordination with a metal ion, likely a zinc ion, given

HDAC1’s known active site structure. Critical residues, including His178, Tyr303,

Tyr204, and Phe205, contribute to the stabilization of the ligand. The hydrogen

bonding network, particularly with Gly143, and

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Representative snapshots from molecular dynamics simulations illustrating inhibitor interactions within the HDAC1 active site. (A) HDAC1-compound 4 complex. (B) HDAC1-compound 6 complex. Structures represent equilibrated conformations after 100 ns simulations.

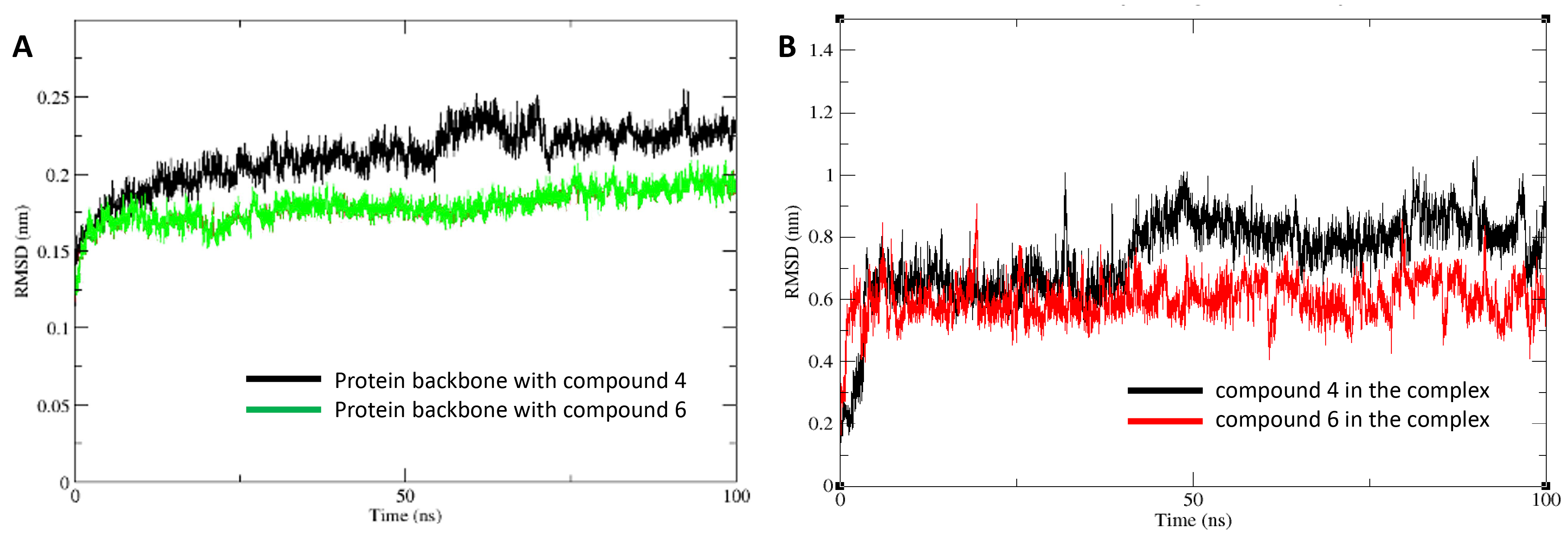

Further confirmation of these stability differences is shown in Fig. 5, which presents the RMSD analysis of the protein-ligand complexes and the ligands themselves. Fig. 5A shows the protein backbone RMSD for the HDAC1:compound 4 complex in black and the HDAC1:compound 6 complex in green. The lower fluctuations in the green curve suggest that compound 6 induces less structural stability in the complex. Fig. 5B shows the RMSD of compound 4 in black and compound 6 in red, plotted as running averages for visual clarity. The greater fluctuations in the red curve indicate that compound 6 experiences more conformational instability, further supporting the observation that compound 4 forms a more stable and favorable interaction with HDAC1.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) analyses from molecular dynamics trajectories. (A) Protein backbone RMSD for HDAC1 bound to compound 4 (black) and compound 6 (green). (B) Ligand RMSDs for compound 4 (black) and compound 6 (red) within the HDAC1 active site. Data are presented as running averages for improved visual clarity. The system reached equilibration after 10 ns.

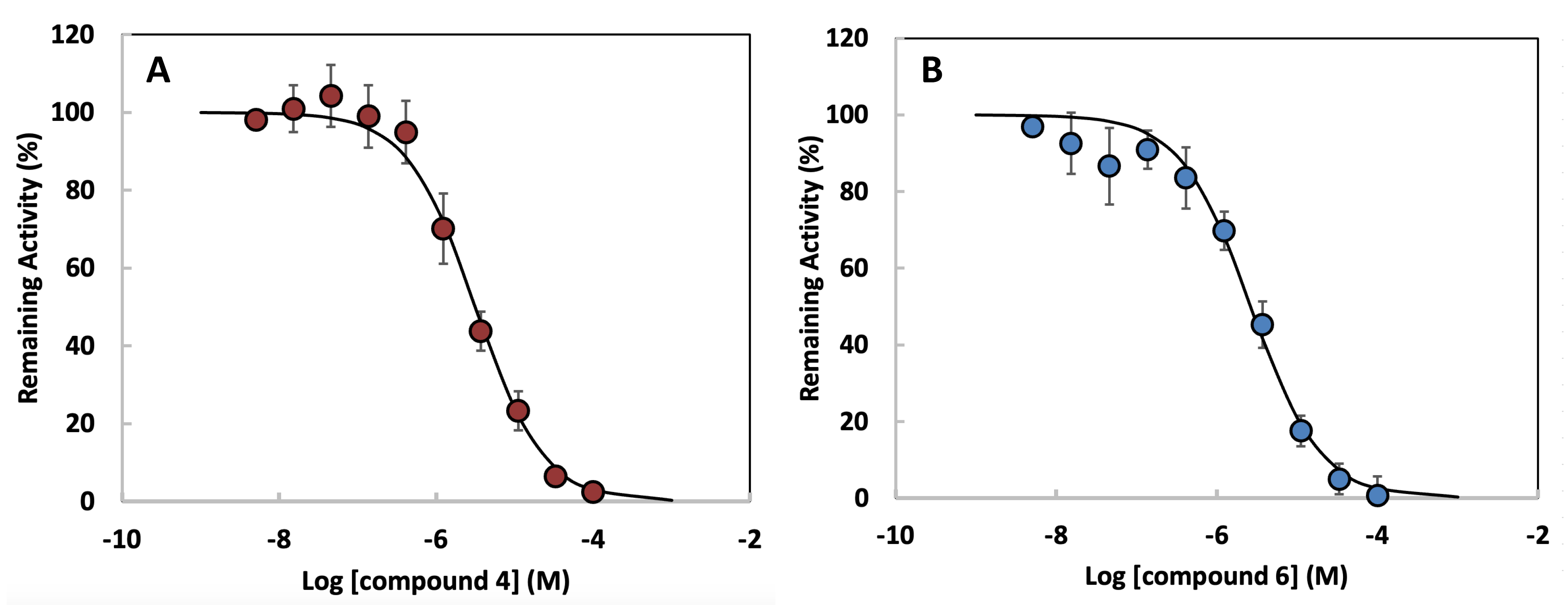

To evaluate the inhibitory effects of compounds 4 and 6 on HDAC1,

concentration-response experiments were conducted. These inhibition tests are

essential to determine the potency of each compound in suppressing HDAC1

activity, which is crucial for validating computational and structural

predictions. The IC50 values obtained provide quantitative insight into the

effectiveness of each compound as an HDAC1 inhibitor. Fig. 6A illustrates the

inhibition profile of compound 4, showing a sigmoidal curve with a steep decline

in remaining HDAC1 activity as the compound concentration increases. The

calculated IC50 value for compound 4 is 2.96

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Concentration-response curves for HDAC1 inhibition by

dihydroxamate derivatives. (A) Compound 4. (B) Compound 6. Data points represent

mean

| Inhibitor | IC50 with HDAC1 |

| Compound 4 | 2.96 µM |

| Compound 6 | 4.76 µM |

HDAC1 plays a crucial role in chromatin remodeling and gene expression regulation, making it a valuable target for cancer therapy. Given the limitations of current HDAC inhibitors, including off-target effects and the emergence of resistance, this study aimed to develop novel hydroxamate-based HDAC1 inhibitors with improved selectivity and potency. Through a combination of molecular docking, MD simulations, and enzymatic inhibition assays, we provide a comprehensive evaluation of two candidate inhibitors, compounds 4 and 6. However, it is important to recognize several limitations in our study upfront. First, the molecular dynamics simulations were conducted in a simplified aqueous environment, which may not fully capture the dynamic complexity of intracellular systems. Second, our enzymatic inhibition assays utilized purified HDAC1, without accounting for factors such as cellular uptake, membrane permeability, or metabolic stability. The absence of cellular assays represents a significant limitation; therefore, findings should be interpreted cautiously until validated in more physiologically relevant systems. We note that HDAC1 features a tetrahedral zinc coordination geometry involving histidine and aspartate residues. The zinc parameters used in this study [20, 28] were originally validated for tetrahedral coordination environments with histidine and cysteine ligands and represent the most current and accurate force field modifications available for metalloprotein simulations. Although the ligand atom types differ slightly, the tetrahedral geometry is maintained, and these parameters were selected as the closest and most appropriate choice for modeling the HDAC1 active site. Nevertheless, coordination geometries were interpreted with caution, recognizing the minor differences in ligand chemistry.

Our approach enabled structural and energetic profiling of inhibitor interactions with HDAC1. Molecular docking revealed that both compounds form critical hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding interactions with the active site of HDAC1. Compound 4 demonstrated stronger binding affinity (–6.2 kcal/mol) than compound 6 (–5.7 kcal/mol), correlating with its enhanced structural fit. MD simulations further substantiated these results, with compound 4 maintaining a more stable binding conformation, as shown by its consistent zinc coordination distances (4.3 and 4.8 Å), compared to the weaker and less stable coordination observed for compound 6 (4.4 Å). RMSD analyses also indicated reduced fluctuations for compound 4, suggesting greater conformational stability within the HDAC1 binding pocket.

To contextualize these findings within the broader landscape of HDAC inhibitors, we included CI-994—a clinically studied HDAC1-selective compound—as a benchmark. CI-994 exhibited comparable binding parameters (AutoDock affinity: –6.3 kcal/mol), closely matching those of compound 4 (–6.2 kcal/mol). This similarity suggests that compound 4 shares structural and energetic properties with known isoform-selective inhibitors, reinforcing its potential as a lead compound with HDAC1-preferential characteristics.

Selectivity toward HDAC1 over other isoforms is a critical factor for reducing off-target toxicity associated with pan-HDAC inhibition. To explore this, we conducted comparative docking simulations of compound 4 with HDAC2 and HDAC8. These studies revealed reduced binding affinities for HDAC2 (–5.4 kcal/mol) and HDAC8 (–5.1 kcal/mol), suggesting a degree of specificity for HDAC1. These results support the structural basis for preferential HDAC1 inhibition and warrant further investigation into isoform selectivity in cellular systems.

Enzymatic inhibition assays further validated the superior potency of compound

4, yielding an IC50 of 2.96 µM compared to 4.76 µM for compound

6. This finding is consistent with prior structure–activity relationships of

hydroxamate-based HDAC inhibitors, where enhanced zinc coordination and hydrogen

bonding networks correlate with stronger inhibition. The differential activity

also points to the importance of the linker and cap group modifications; compound

4’s hydroxyl-substituted aromatic cap likely facilitates more optimal

interactions with key residues such as Phe205 and His178, while the methoxy

substitution in compound 6 may introduce steric hindrance or alter hydrogen

bonding geometry. The observed difference in potency between compounds 4 and 6

was statistically validated by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test

(p

Although these results are promising, the limitations noted earlier highlight the need for additional studies in physiologically relevant conditions. Future investigations will be conducted using cell-based models to comprehensively evaluate the biological activity of compounds 4 and 6. These studies may include apoptosis assays, histone acetylation analysis, gene expression profiling (western blotting, qPCR, and chromatin immunoprecipitation), and cytotoxicity and proliferation assays in HDAC1-overexpressing cancer cell lines. Further characterization through in vivo pharmacokinetic analyses and isoform-wide enzymatic testing will be critical to fully understand the therapeutic potential and selectivity of these candidates.

This study highlights the potential of compound 4 as a highly stable and potent HDAC1 inhibitor, outperforming compound 6 in binding affinity, stability, and enzymatic inhibition. These findings contribute to the ongoing development of selective HDAC inhibitors and provide a foundation for future drug optimization efforts. By refining the structural properties of these compounds, we move closer to developing effective epigenetic therapies with reduced toxicity and enhanced clinical efficacy. However, given the inherent caveats in computational and in vitro studies, further validation through advanced biological models is warranted.

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

JGS, AEH, and MCG: computational and experimental data acquisition, AB, JU, and SD: synthesis and experimental data acquisition, JNT: conceptualization, and review, HS, JJ and SKK: conceptualization, data interpretation, supervision, manuscript writing, and funding acquisition. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We gratefully acknowledge the technical support provided by Northeastern State University. We also appreciate the financial support from the funding agencies. Additionally, we thank Lydia Neff for her valuable review and suggestions on this manuscript.

This study was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number P20GM103447, as well as by the Faculty Research Committee of Northeastern State University (24-01) to SKK. Additionally, funding was provided by the NIH (GM116031) to JJ, and the Welch Robert Foundation, Departmental Grant (Z-0036) to HS.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT to check spelling and grammar throughout the manuscript. After utilizing this tool, the authors thoroughly reviewed and edited the content as necessary, ensuring accuracy and coherence. The authors take full responsibility for the final content of this publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.