1 Department of Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary & Liver Transplant Surgery, Digestive Diseases and Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA

2 Department of Inflammation & Immunity, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA

3 Department of Gastroenterology, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Digestive Diseases and Surgery Institute, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Similar to many other cancer types, liver malignancies pose the common challenges of late detection of primary tumors and recurrences. Liquid biopsies, which assess the presence of circulating tumor DNA, have emerged as a novel, non-invasive clinical tool for diagnostic and surveillance purposes. This review represents an introductory and comprehensive overview of the current circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) literature relevant to primary and secondary liver malignancies. Herein, we highlight key findings, landmark discoveries, challenges, and future directions.

Keywords

- circulating tumor DNA

- ctDNA

- liquid biopsy

- liver cancer

- liver malignancy

Liver-related malignancies comprise the sixth most common cause of cancer and third leading cause of cancer death [1]. Primary liver cancers include hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (85–90% of cases) and cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) (10–15% of cases) [1]. Secondary liver malignancies include metastases arising from the lung, colorectum, pancreas, stomach, breast, and cecum [2]. Approximately 5% of cancer patients present with synchronous liver metastases, with the most common primary site being breast cancer for young females and colorectal cancer for young males [3]. For older patients, lung, pancreatic, and colorectal cancers are the most common primary sites, although a greater percentage of primary esophageal, stomach, small intestine, melanoma, and bladder cancers start to emerge with age [3].

Common to all liver malignancies is a worse prognosis associated with late stage of disease. The one-year survival of patients with liver metastases from any primary cancer is lower (15.1%) than those with non-hepatic metastases (24%) [3]. Advanced disease is multi-factorial due to limited sensitivity and specificity of biomarkers, more aggressive tumor biology, and lack of early, specific symptoms [4]. Current methods of liver cancer detection include radiologic imaging, tissue sampling, and traditional serum biomarkers [5]. However, radiologic imaging is limited in patients with small nodules and early microscopic lesions [6]. Tissue sampling requires invasive biopsy procedures and may yield insufficient tissue for diagnosis and high false negative rates [7, 8]. Traditional serum biomarkers, such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) are limited in their sensitivity and specificity [9, 10].

To address these limitations, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has become of interest due to its non-invasive nature through liquid biopsy and its ability to provide insight into the nature of individual patient tumor biology [11]. One meta-analysis revealed a high overall sensitivity (72.2%) and specificity (82.3%) along with diagnostic odds ratio (18.53) and area under the curve (AUC) (0.88) for ctDNA in HCC, displaying its potential as a diagnostic marker [12]. This tool, now FDA-approved for monitoring minimal residual disease for colorectal liver metastasis, holds significant potential as a surveillance and prognostic tool for liver malignancies. In terms of prognosis, patients with detectable ctDNA following curative-intent local therapy for colorectal cancer with liver metastasis have been shown to have significantly higher potential for recurrence and shorter overall survival (OS) compared to those without detectable ctDNA [13].

This comprehensive narrative review serves as an introduction to ctDNA and the landscape of ctDNA literature within primary and secondary liver cancers. First, the concept of ctDNA as a biomarker is introduced, followed by summaries of key studies on clinical utility and mutational profiles by cancer subtype. Lastly, insight into challenges and limitations of current studies involving ctDNA is provided, along with commentary on future directions for research and clinical applications. Detailed descriptions of the methodologies are not included in the present review due to heterogeneity in ctDNA detection methods; however, readers are encouraged to refer to cited materials for further information.

ctDNA refers to genomic material released by tumor cells into the patient’s systemic circulation. An early study in 1977 showed the presence of cell-free DNA from peripheral blood of cancer patients, but further characterization was limited by technology at the time [14]. Recent advancements in genetic amplification technology have allowed deeper investigation into this genomic material, identifying single-nucleotide changes [15], methylation patterns [16, 17, 18], and viral sequences [19] derived from or reflective of the original tumor.

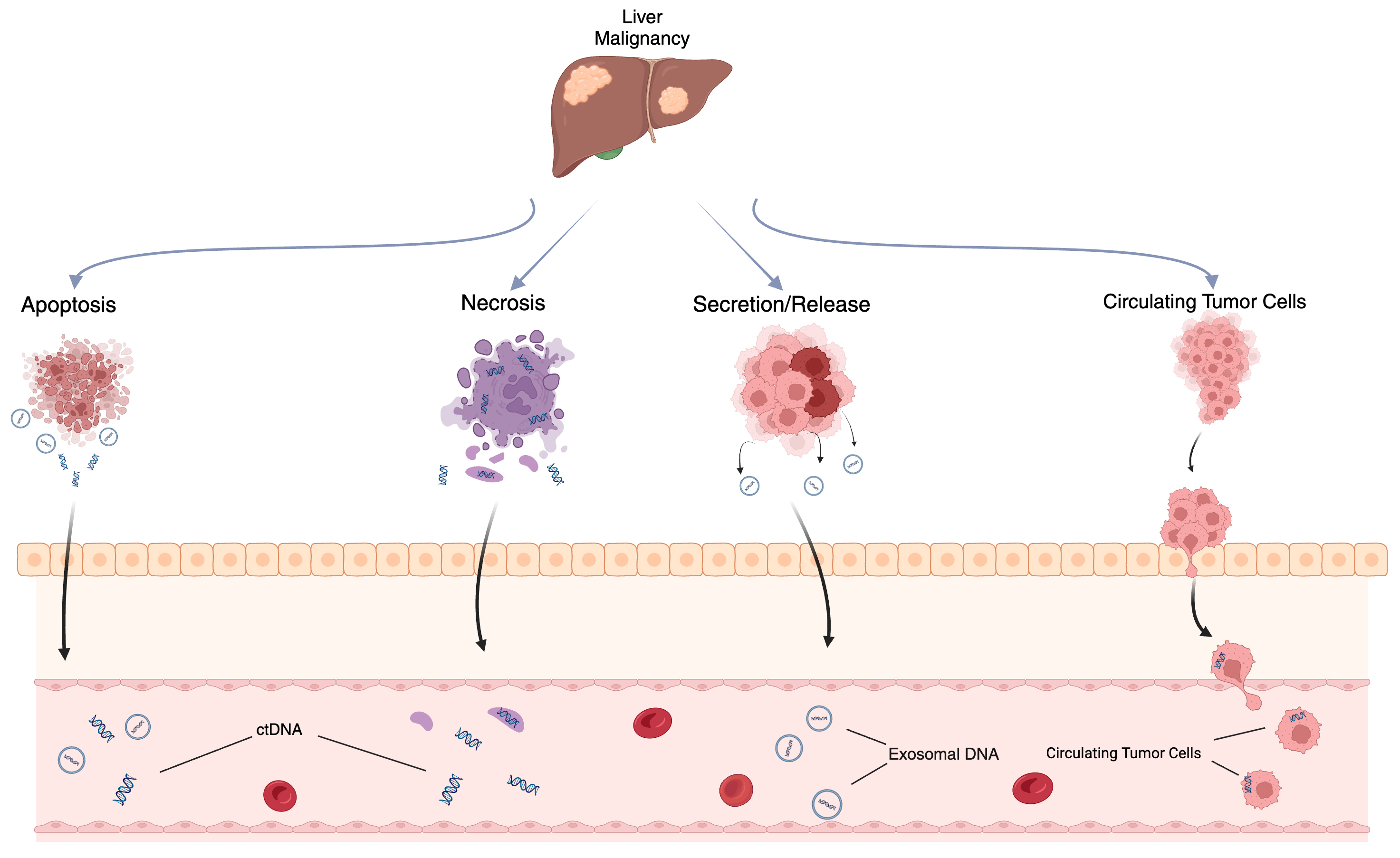

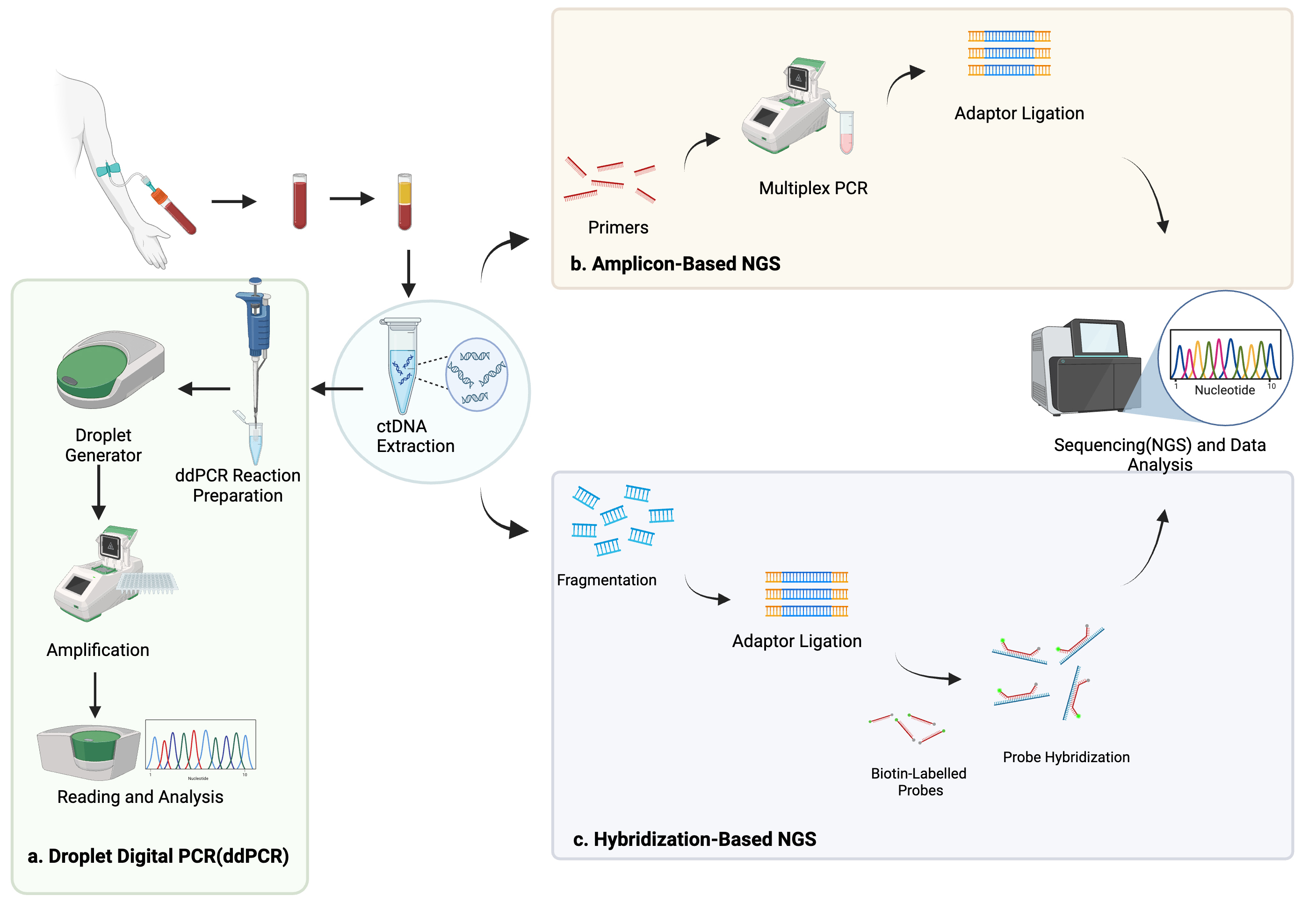

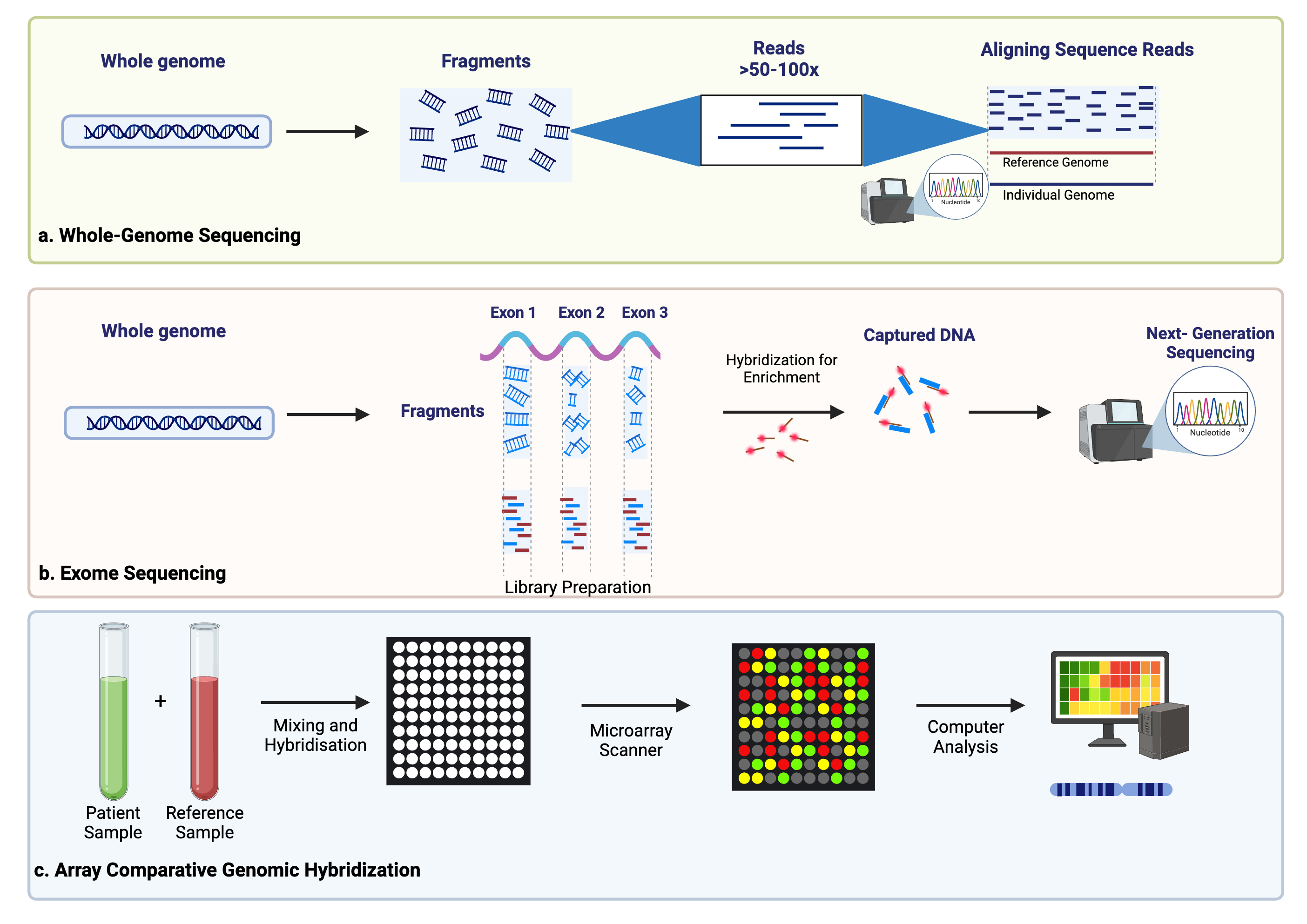

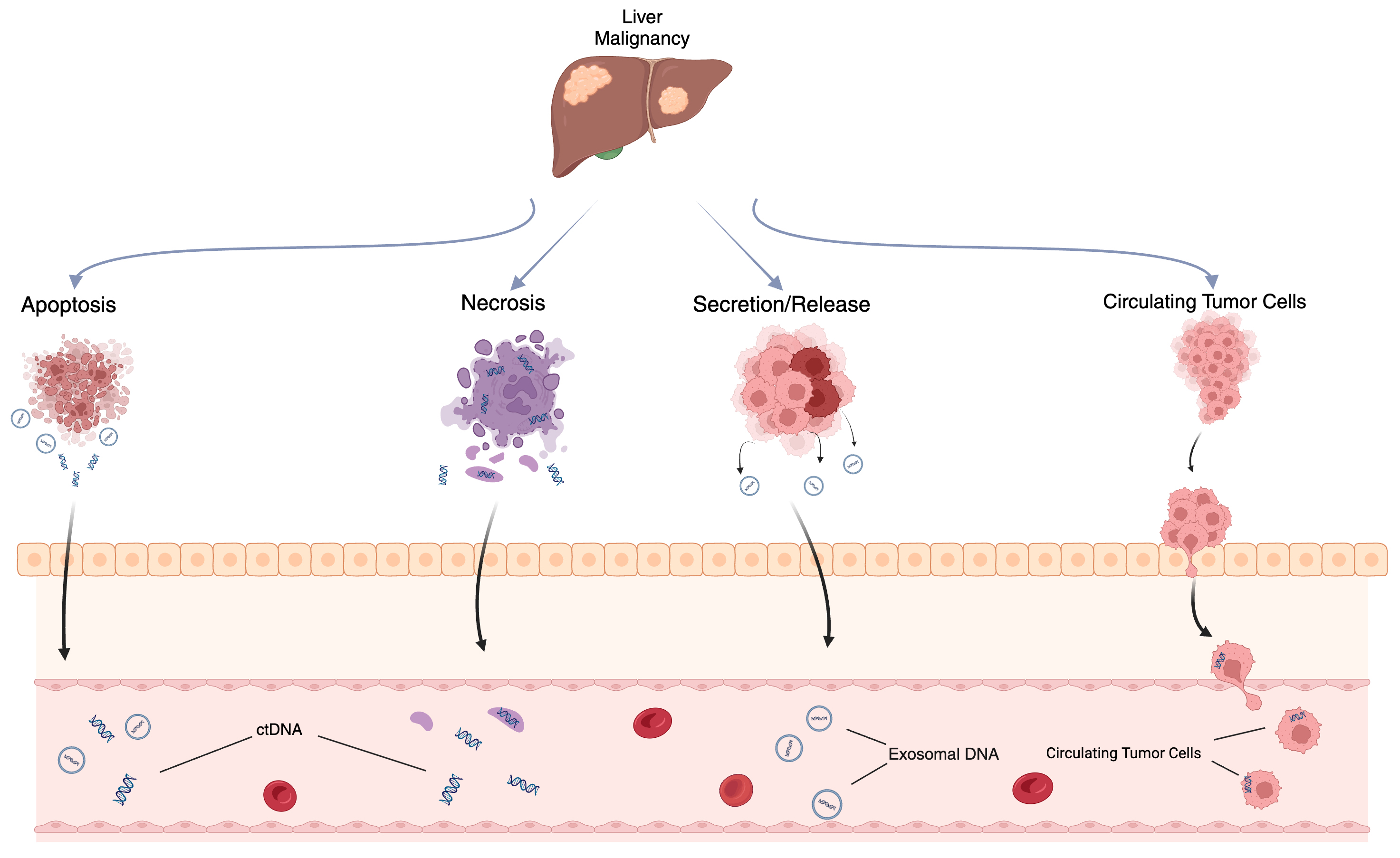

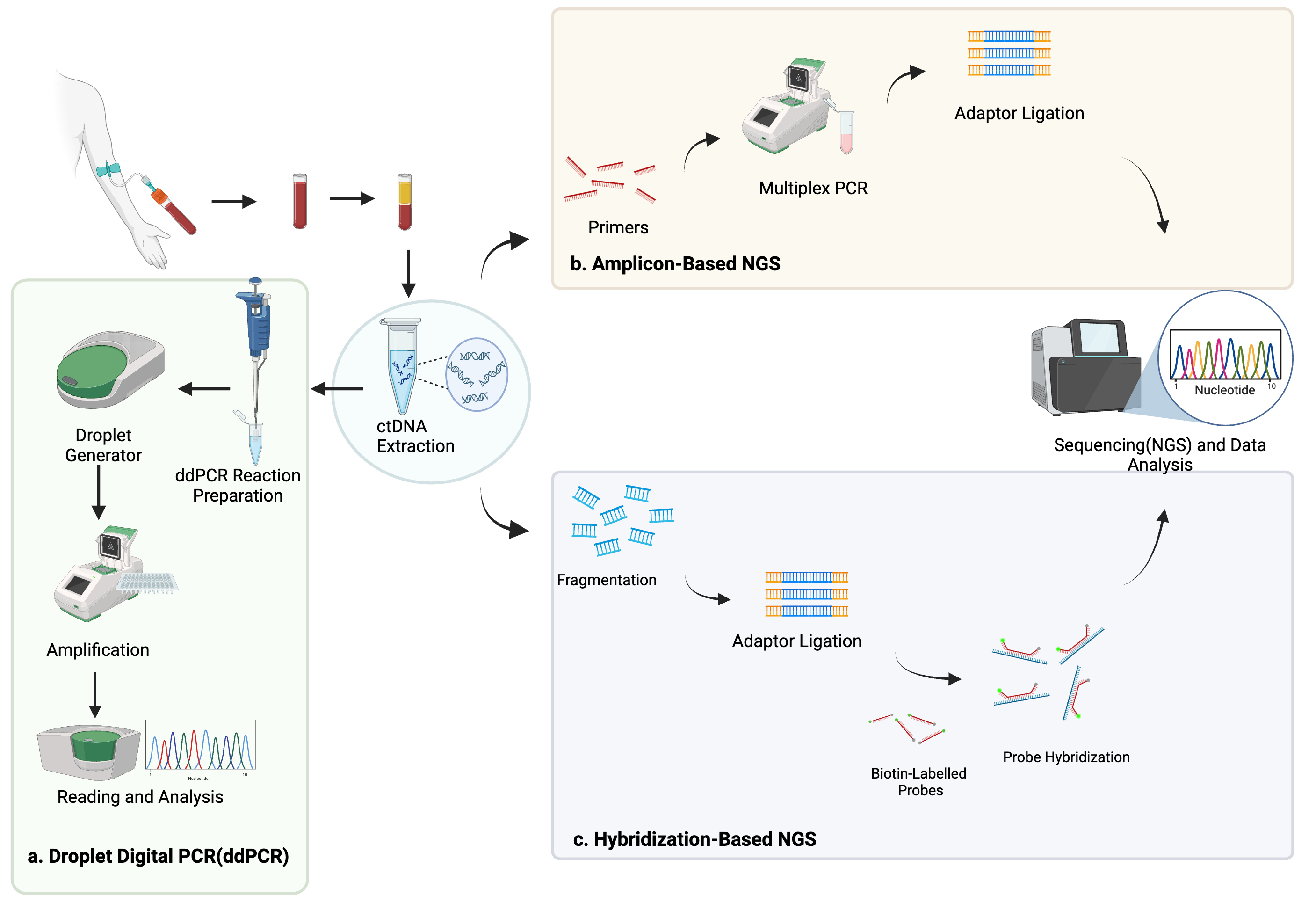

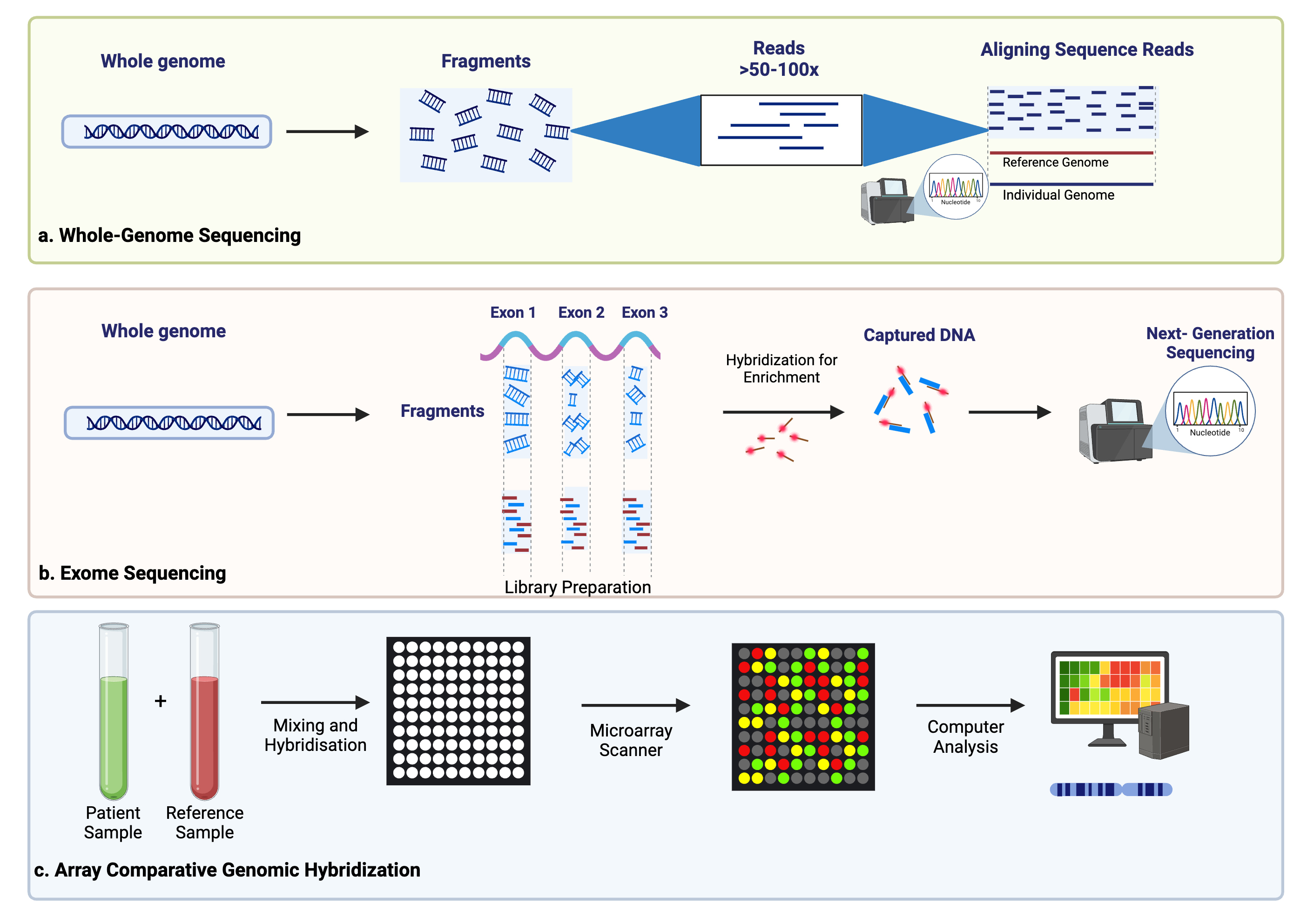

ctDNA is thought to originate from several sources, including apoptotic or necrotic tumor cells, live tumor cells, and circulating tumor cells (Fig. 1) [20, 21]. Due to its relatively short half-life of up to two hours, ctDNA reflects the tumor biology in a dynamic fashion [22]. Methods of detection include droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), personalized amplicon-based NGS, personalized hybridization-based next-generation sequencing (NGS), whole-genome sequencing, exome sequencing, or array comparative genomic hybridization (Figs. 2,3) [23, 24]. Detection and analytic methods can be performed in tumor-informed, which decreases risk of false positive results, or tumor-uninformed fashions, which can allow for detection of clonal evolution and tumor resistance.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Methods of ctDNA detection including droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (a), amplicon-based next-generation sequencing (NGS) (b), and hybridization-based NGS (c). Created using BioRender.com.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Additional methods of ctDNA detection including whole-genome sequencing (a), exome sequencing (b), and array comparative genome hybridization (c). Created using BioRender.com.

HCC is the sixth most common cancer worldwide and third leading cause of cancer-related deaths [1]. The standard diagnostic method consists of radiologic imaging (e.g., computer tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) and detection of elevated alpha-fetal protein (AFP) levels. Despite a high specificity for early HCC, AFP has limited and variable sensitivity [25, 26]. In contrast, ctDNA has a reported sensitivity of 100% (42/42) and specificity of 97.4% (75/77) for detecting recurrence in patients with HCC following surgery and adjuvant therapy [27]. Recently published clinical trial results also show the ability of a liquid biopsy-based DNA methylation signature to detect HCC with 84.5% sensitivity, 95% specificity, and 0.94 AUC [18]. Further information regarding this trial, along with other completed and recruiting clinical trials for primary and secondary liver malignancies, is summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [18, 28, 29, 30, 31]) and Table 2 respectively.

| NCT | Study Title | Study Type | Liver Cancer Type | Intervention | Sample Population | Study Dates | Outcome Measures | Sponsor | Associated Publication |

| NCT03483922 | HCC Screening Using DNA Methylation Changes in ctDNA | Observational (Case-control) | HCC | Diagnostic Test: ctDNA methylation in and it’s Correlation with Development and prediction of HCC | 402 participants from Dhaka area-49 healthy controls, 51 chronic HBV patients, 302 HCC patients | August 20, 2018–June 1, 2020 | Primary: Normalized median methylation values for HCC detection and specificity Results: Using 4 CpG sites validated in TCGA HCC data, HCC detection sensitivity was 84.5% and specificity was 95% with an AUC of 0.94. |

HKGepitherapeutics | [18] |

| NCT02973204 | Circulating Tumor Cells and Tumor DNA in HCC and NET | Observational | HCC | Drug: Sorafeniib, everolimus, lanreotide Procedure: Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) |

Planned: 40 patients with newly diagnosed NET (of unknown primary), 30 pancreatic NET treated for known residual disease, 30 HCC patients treated with RFA or liver resection Actual enrollment: 167 |

November 2016–January 2020 | Primary: Concordance between biopsy and plasma ctDNA mutations (ddPCR). Secondary: Detection and quantification of CTC, correlation between ctDNA and CTCs in terms of mutations, treatment response, survival. |

University of Aarhus | N/A |

| NCT05823584 | Cell-free DNA From Junction of Hepatitis B Virus Integration in HCC Patients for Monitoring Post-resection Recurrence | Observational | HCC | Surgery: Resection or liver transplant | 207 | December 22, 2019–December 31, 2023 | Primary: Pre-operative sensitivity of vh-DNA with AFP as biomarker for HCC recurrence. | TCM Biotech International Corp. | N/A |

| Secondary: Sensitivity and specificity of vh-DNA with AFP-L3/PIVKA-II/TERTp C228T as biomarker for recurrence, clonality of recurrent HCC | |||||||||

| NCT05540925 | Vascular Invasion Signatures in cfDNA Support Re-staging of Liver Cancer | Observational | HCC (early-stage) | Procedure: Liver resection | 286 | June 2016–December 2017 | Primary: Recurrence free survival, overall survival stratified by risk for MVI as determined from nomogram derived from sequencing data of cfDNA (high risk |

Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital | N/A |

| Secondary: Local recurrence. | |||||||||

| NCT03071458 | Mutational Landscape in Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Observational | HCC | Procedure: Liver transplant, radiofrequency ablation, resection | 808 Total: 224 tumor, 224 non-tumor from LT 129 HCC, 129 non-tumor from RFA 342 HCC, 342 non-tumor from liver resection 40 HCC, 35 non-tumor from biopsies of advanced HCC |

January 2008–May 2015 | Primary: Identification of the main genetic driver and transcriptomic subgroups among a large panel of HCC. Secondary: Detection of ctDNA in patients with early and advanced HCC, review of genetic drivers and oncognic pathways with IHC, validation of tumor analyses using clinical data, pathological and IHC features, molecular classification and genetic alterations. |

Institut National de la Santé Et de la Recherche Médicale, France | N/A |

| NCT03893695 | Combination of GT90001 and Nivolumab in Patients With Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) | Interventional | HCC (Advanced or metastatic, failed first-line and/or second-line systemic therapy) | Drug: GT90001 (anti-ALK1 mAb) and Nivolumab | 20 | May 25 2019–September 27 2022 | Primary outcome: Dose-limiting toxicity. | Suzhou Kintor Pharmaceutical Inc | [30] |

| Secondary outcomes: Overall response rate, duration of response, disease control rate, time to response, progression-free survival, pharmacokinetics, ctDNA. | |||||||||

| NCT06404593 | Dynamic ctDNA Detection for Guiding Adjuvant Therapy and Recurrence Monitoring After Curative Resection of Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases: A Prospective Study | Observational | CRLM | Diagnostic test: Blood sampling pre-operatively and post-operatively (serial) for ctDNA | 270 | June 18, 2019–December 31, 2023 | Primary outcomes: Progression-free survival, overall survival. | Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute | N/A |

| NCT01749332 | A Pilot Study of Perihepatic Phlebotomy During Hepatic Resections | Observational | CRLM | Other: Perihepatic Phlebotomy-Perioperative and postoperative draw from peripheral, portal, and hepatic veins | 117 | December 2012–2019 | Primary: ctDNA differences between perihepatic and peripheral ctDNA Secondary: Correlation of peripheatpic and peripheral ctDNA mutation with recurrence and survival patterns. Results: Detection of peripheral ctDNA mutant TP63 was associated with worse 2-year DSS (mt+ 79% vs. mt− 90%, p = 0.024). Most commonly mutated genes were TP53 (mtTP53, 47.5%) and APC (mtAPC, 50.8%). Substantial to almost-perfect agreement was seen between ctDNA from PERIPH and PV (mtTP53: 89.8%, |

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center | [29] |

| ACTRN12615000381583 | Circulating Tumour DNA Analysis Informing Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Stage II Colon Cancer (DYNAMIC) | Interventional | CRLM (stage II) | ctDNA-guided management vs. Standard clinicopathologic management of adjuvant therapy | 455 randomized, 302 ctDNA-guided management, 153 standard management | August 10 2015–July 25 2019 | Results: ctDNA-guided management was noninferior to standard management for 2-year recurrence free survival (93.5% vs. 92.4% respectively; absolute difference, 1.1 percentage points; 95% CI, –4.1 to 6.2 [noninferiority margin, –8.5 percentage points]). | National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) | [28] |

| NCT03415126 | A Study of ASN007 in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors | Interventional | Metastatic BRAF mutated melanoma, metastatic NRAS and HRAS mutated solid tumors, metastatic KRAS mutated CRC, metastasis KRAS mutated NSCLC, metastatic PDAC | Drug: ASN007 (ERK1/2 inhibitor) | 49 | January 19, 2018–June 30, 2020 | Primary: maximum tolerable dose, overall response rate. Secondary: Pharmacokinetic AUC, maximum plasma concentration, terminal elimination rate, change in baseline phosphorylated ribosomal S6 kinase in tumor biopsies, change in amount of ctDNA. |

Asana BioSciences | [31] |

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CRLM, colorectal liver metastases; CI, confidence interval; CRC, colorectal cancer; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-related kinase1/2; NCT, National Clinical Trial; HBV, hepatitis B virus; TCGA, the cancer genome atlas; AUC, area under the curve; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; CTC, circulating tumor cell; cfDNA, cell-free DNA; vh-DNA, virus-host chimera DNA; AFP-L3/PIVKA-II/TERTp, alpha-fetoprotein-L3/protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II/telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter; MVI, microvascular invasion; IHC, immunohistochemistry; TP53, tumor protein 53; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; PERIPH, peripheral; PV, portal vein; HV, hepatic vein; NRAS, neuroblastoma ras viral oncogene homolog; HRAS, Harvey rat sarcoma virus; KRAS, Kirsten rat sarcoma virus.

| NCT | Study Title | Study Type | Liver Cancer Type | Intervention | Sample Size | Study Dates | Outcome Measures | Sponsor |

| NCT06178809 | Clinical Research on Dynamic Monitoring MRD Via Plasma ctDNA After Systemic Therapy of Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Observational | HCC | Surgery and systemic treatment | 475 | December 25, 2023–December 2025 | Primary: Accuracy of detection of plasma ctDNA mutation and methylation in predicting disease-free survival (DFS) or progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with primary hepatocellular carcinoma after treatment | Singlera Genomics Inc. |

| Secondary: Advance time of ctDNA dynamic detection compared with AFP+ imaging in monitoring of primary hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence or progression | ||||||||

| NCT06157060 | Prediction of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence After Curative Treatment by Longitudinal Monitoring MRD Based on ctDNA | Observational | HCC | Surgical resection | 255 | November 20, 2023–December 30, 2026 | Primary: 2-year recurrence-free survival rate Secondary: Correlation between ctDNA-MRD status dynamic changes and relapsADe |

Zhujiang Hospital |

| NCT05981066 | A Clinical Study of mRNA Vaccine (ABOR2014/IPM511) in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Interventional | HCC | ABOR2014/IPM511 mRNA vaccine | 48 | July 10, 2023–December 31, 2025 | Primary: Incidence and severity of adverse events, Clinically significant abnormal changes in vital signs or laboratory tests | Peking Union Medical College Hospital |

| Secondary: Maximum Plasma Concentration [Cmax] and Half-time of Plasma Concentration [T1/2] of IPM511, Antigen-specific T-cell responses in peripheral blood, Change of Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) status, ORR, DoR, PFS, OS | ||||||||

| NCT05669339 | AD HOC Trial: Artificial Intelligence-Based Drug Dosing In Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Interventional | HCC | Drugs: Irinotecan, Sonidegib, and Sorafenib | 12 | September 2024–April 2026 | Primary: Maximally tolerated dose | University of Florida |

| Secondary: ORR, Change in AFP, AFP-L3, DGC, and TGF-B | ||||||||

| Drug efficacy will be measured by changes in ctDNA. | ||||||||

| NCT05626985 | Refinement and Validation of a Diagnostic Model (GAMAD) for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Observational | HCC | Treatment per NCCN guidelines | 2000 | October 19, 2022–December 2024 | Primary: GAMAD calculator model | Singlera Genomics Inc |

| Secondary: GALAD calculator score, Circulating tumor DNA methylation | ||||||||

| NCT05390112 | Cohort Study of Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Circulating Tumor DNA Monitoring of Chemoembolization (Mona-Lisa) | Observational | HCC | TACE | 167 | May 20, 2021–December 31, 2024 | Primary: Radiological response at 1 month according to mRECIST and ctDNA detection | University Hospital, Rouen |

| Secondary: PFS, OS | ||||||||

| NCT04134559 | Checkpoint Inhibition In Pediatric Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Interventional | HCC | Pembrolizumab | 18 | November 1, 2020–January 1, 2025 | Primary: Immune-related best overall response (irBOR) Secondary: Expression levels of infiltrating immune cells and markers of checkpoint inhibition on pre-treatment specimens, PFS, Percent change immune cell phenotype, cytokines, and circulating tumor DNA, Number of Participants with DLT, DNA sequencing of specimens |

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute |

| NCT03839706 | Relationship Between 18FDG PET/MRI Patterns and ctDNA to Predict HCC Recurrence After Liver Transplantation (PETMRIinHCC) | Interventional | HCC | Liver transplantation | 20 | August 22, 2018–September 2024 | Primary: 18F-FDG PET/MRI results to identify aggressive HCC behavior and recurrence post transplant | University Health Network, Toronto |

| Secondary: 18F-FDG PET/MRI to predict HCC’s poor tumoral differentiation, 18F-FDG PET/MRI are relation to circulating tumor DNA in plasma | ||||||||

| NCT06028724 | A Study on the Prevalence of Clinically Useful Mutations in Solid Tumor Characterized by Next Generation Sequencing Methods on Liquid Biopsy Analysis (POPCORN) | Observational | Advanced HCC or cholangiocarcinoma | Not specified | 782 | May 26, 2023–May 31, 2030 | Primary: Real world prevalence of clinically useful mutations in solid tumors | Centro di Riferimento Oncologico - Aviano |

| Secondary: To identify emerging gene alterations associated with PFS or OS, To describe changes in ctDNA associated biomarkers during treatment, To evaluate the association between somatic genetic alterations and pattern of metastasis, To evaluate the association between somatic genetic alterations and the histopathological features of the tumor, To evaluate the association between somatic genetic alterations and pattern of metastasis, To evaluate the association between somatic genetic alterations and the clinical characteristic of the enrolled patients | ||||||||

| NCT06541652 | A French Multicenter Observational Retrospective Study of Rare Primary Liver Cancers (FFCD-2205) | Observational | Hepatocholangiocarcinoma, fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma or hepatic angiosarcoma | Diagnostic: Blood sample | 150 | March 26, 2024–February 2031 | Primary: Description of the clinical, histological and radiological characteristics of various rare primary liver cancers (ctDNA included) | Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive |

| Secondary: Recurrence-free survival, Progression-free survival, Overall survival | ||||||||

| NCT06391749 | Clinical Validation of an MCED Test in Symptomatic Populations (K-ACCELERATE) | Observational | Benign primary liver cancer | Not specified | 1000 | May 2024–November 2025 | Primary: Evaluate the performance of the SPOT-MAS test to detect cancer in symptomatic individuals | Gene Solutions |

| Secondary: Feasibility of using SPOT-MAS as a triage test to assist in decision-making for follow-up high-resolution imaging or tissue biopsy procedures | ||||||||

| NCT02838836 | Tumor Cell and DNA Detection in the Blood, Urine and Bone Marrow of Patients With Solid Cancers | Observational | Primary liver cancer | Surgical resection | 620 | July 1, 2016–December 1, 2026 | Primary: CTC/DTC numbers measured in blood, urine and bone marrow samples will be correlated with patient outcome | University of Missouri-Columbia |

| Secondary: CTC/DTC numbers measured in blood, urine and bone marrow samples will be correlated with patient outcome | ||||||||

| NCT05633342 | Project CADENCE (CAncer Detected Early caN be CurEd) | Observational | Any liver cancer | Prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy | 15,000 | July 7, 2022–May 2025 | Primary: To discover novel intracellular RNA and methylated DNA cancer biomarkers in fresh frozen tumor tissues | MiRXES Pte Ltd. |

| Secondary: To select the best-performing multi-omic single-cancer, biomarker panels for each of the cancer types, and develop the corresponding Single-Cancer Early detection Algorithms (SCEAs), To discover and validate novel cell-free RNA and methylated cell-free DNA cancer biomarkers in the peripheral blood of cancer patients, To develop the best-performing multi-omic multi-cancer biomarker panel by integration and/or optimization of single-cancer panels and develop the corresponding Multi-Cancer Early detection Algorithm (MCEA), To develop in vitro diagnostic assay(s) for the Multi-Cancer Screening Test (MCST) and if appropriate Single-Cancer Screening Tests (SCSTs), To evaluate the clinical performance (AUC, sensitivity, specificity, tissue of origin) of the MCST and if appropriate SCSTs to discriminate cancer cases from control groups |

ORR, objective response rate; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; DGC, des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin; TGF-B, transforming growth factor beta; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; GALAD, (Gener+age+AFP-L3+AFP+DCP); TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; DLT, dose-limiting toxicity; 18F-FDG PET/MRI, 18F-fluorodexoyglucose positron emission tomography magnetic resonance imaging; SPOT-MAS, screening for the presence of tumor by methylation and size; DTC, disseminated tumor cell; MRD, molecular residual disease; DoR, duration of response.

Several studies have explored the clinical utility of ctDNA in HCC. In 2020,

Wang et al. [32] found a higher cancer detection rate using

pre-operative plasma ctDNA (70.4%, n = 57/81) with a panel of 4 mutations

(TP53 (c.747G

Characteristics provided by ctDNA testing, such as extent of tumor mutational burden (TMB), have also been shown to correlate with survival. Wehrle et al. (2024) [36] demonstrated an association between TMB on post-operative ctDNA and shorter recurrence-free survival (RFS) in 48 patients with HCC following surgical resection. With immunotherapy emerging as a treatment option for HCC as suggested by the Imbrave50 trial results, this may suggest a role for adjuvant immunotherapy in this patient population. Similarly, preliminary data from Marron et al. (2023) [37] shows the ability of post-operative ctDNA in detecting disease relapse and shorter recurrence-free survival for patients undergoing neoadjuvant and adjuvant cemiplimab (anti-PD-1) and surgical resection.

For patients with unresectable HCC, ctDNA also plays a role in predicting

treatment response. Preliminary results from a personalized, tumor-informed assay

show a prolonged PFS in patients whose ctDNA became undetectable following

treatment [38]. In another study, 3/4 (75%) patients undergoing immunotherapy

and locoregional therapy changed from detectable to non-detectable TMB on their

ctDNA following curative-intent hepatectomy [39]. CtDNA can also provide insight

into the mutational landscape driving resistance to systemic therapies in

advanced HCC. For example, von Felden et al. (2021) [40] conducted

targeted sequencing of 25 genes and ddPCR of the TERT promoter on plasma

ctDNA, and found that patients with mutations in the PI3K/MTOR pathway exhibited

significantly shorter PFS (2.1 vs. 3.7 months, p

Other studies have used ctDNA to investigate mutational pathways driving HCC tumorigenesis. For example, Ikeda et al. (2018) [41] performed ctDNA and tissue NGS testing on 26 patients with HCC and identified common mutations of TP53 (50%), CTNNB1 (100%), and ARID1A (90%). An et al. (2019) [33] assessed the presence of nine presumptive driver genes for HCC (TP53, AXIN1, CTNNB1, CDKN2A, ARIN1A, ARID2, SMARCA4, KEAP1 and NFE2L2) and found 37 driver events in 88.5% cases (23/26). On an epigenetic level, aberrant promoter methylation of tumor suppressor genes p16, GSTP1, and RASSF1A have been noted in both the plasma and tumor tissue of patients with HCC [42, 43, 44, 45, 46]. More specifically, p16 methylation was noted in 73% (16/22) HCC tissues and 81% (13/16) HCC plasma/serum samples, while being absent in the plasma/serum of healthy patients and patients with chronic hepatitis/cirrhosis [43]. Hypermethylation of GSTP1, which encodes glutathione S-transferase, was observed in 88.5% (23/26) of HCC tumor tissue and 50% (16/32) patients with HCC, while none of the normal peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples from healthy patients (n = 12) had aberrant GSTP1 methylation [45]. For RASSF1A, aberrant promoter methylation was detected in 92.5% (37/40) of HCC tissues and 42.5% (17/40) of paired plasma, while being associated with HCC tumor size of at least 4 centimeters (p = 0.035) [46]. Hypomethylation of serum LINE-1 has also been shown to be a significant and independent prognostic marker of overall survival for patients with HCC [47]. Additionally, the average level of serum LINE-1 hypomethylation differed significantly among patients who were healthy and those with HCC, cirrhosis, or hepatitis B virus [47]. Thus, specific genetic and epigenetic changes within HCC tumors may be detectable peripherally from patient plasma/serum, establishing another method of clinical diagnosis.

Finally, we hypothesize potential utility of ctDNA in transplant selection

criteria. Studies have demonstrated generally equivalent outcomes across the many

currently described selection criteria, indicating the current spectrum of

biomarkers are ineffective at advancing our discriminatory capability [48, 49, 50].

In contrast, ctDNA status has been shown to be associated with shorter RFS and

higher recurrence rate based on serial ctDNA testing [51]. In a study by Huang

et al. (2024) [51] featuring 74 patients undergoing liver transplant for

cancer, patients with plasma ctDNA detected postoperatively had a shorter RFS of

17.2 months (vs. 19.2 months, p = 0.010) and higher recurrence rate

(46.2% vs. 21.3%, p

CCA accounts for 10–15% of primary liver cancers. In the U.S., Australia, and Europe, CCA affects 0.3–3.5 individuals per 100,000 people, but can also reach incidences of 85 cases per 100,000 people in areas such as northeastern Thailand, where liver fluke infection is more common [52]. 5-year overall survival rates for CCA are only about 15–20%, even after curative-intent surgery and adjuvant therapy [53]. Timely diagnosis of CCA is challenging due to limited samples obtained during biopsy, equivocal results of diagnostic testing and radiologic imaging, and lack of specific tumor markers [54]. Therefore, many patients have advanced or systemic disease at time of diagnosis, precluding surgical resection, which is considered the gold-standard therapy [55]. CA19-9 is a traditional serum biomarker used in diagnosing and monitoring CCA. However, its poor sensitivity and specificity, high false positive rate, and unreliable nature in patients with benign conditions including primary sclerosing cholangitis render it a suboptimal biomarker [56, 57].

In terms of clinical utility, ctDNA has been shown to predict survival in

patients with CCA. A study by Uson Junior et al. (2022) [58] featured

patients with metastatic intrahepatic CCA, extrahepatic CCA, and gallbladder

cancer who underwent ctDNA testing prior to initiation of first-line treatment

with platinum-based chemotherapy. After adjusting for cancer subtype, metastatic

site, largest tumor size, age, sex, and CA19-9 levels, each 1% increase in ctDNA

level was associated with HR of 13.1 in OS [58]. Additionally, when stratifying

dominant clonal allele frequency (DCAF) from ctDNA by quartile (ctDNA

More recently, preliminary results from the STAMP (adjuvant gemcitabine plus cisplatin (GemCis) versus capecitabine (CAP) in node-positive extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CCA)) trial show feasibility of ctDNA monitoring prior to and during adjuvant chemotherapy, with improved RFS in patients who remained ctDNA negative on adjuvant chemotherapy relative to patients who were ctDNA positive [60]. The utility of tumor-informed ctDNA testing-based minimal residual disease detection in CCA was also recently exemplified in a case study published by Yu et al. [61]. In this case, tumor-informed ctDNA testing identified high levels of microsatellite instability and tumor mutational burden, leading to early treatment with pembrolizumab and a DFS within the study follow up period of two years.

Given the wide genetic heterogeneity of CCA, investigation of tumor mutational profiles with ctDNA is valuable. One multi-institutional study of 1671 patients with advanced biliary tract cancer showed fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) fusions, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mutations, and BRAF V600E mutations to be clonal alterations, likely representing early oncogenic drivers [62]. A smaller scale study of 71 patients with CCA showed alterations in TP53 (38%), KRAS (28%), and PIK3CA (14%) as the most common [63]. Another study surveying the mutational landscape of biliary tract cancers using ctDNA among 124 patients identified TP53 and KRAS as the most common alterations in all subtypes of disease, followed by FGFR2 for the intrahepatic subtype, ARID1A for the extrahepatic subtype, and CDK6, APC, and SMAD4 for the gallbladder subtype [64]. Interestingly, the spectrum of detectable alterations on ctDNA can vary based on age, as patients with early-onset biliary tract cancer (or less than 50 years of age) were shown to have higher rates of FGFR2 fusions or single-nucleotide variations (21%) compared to those greater than 50 years of age (2%, p = 0.2). Conversely, older patients had higher rates of TP53 mutations (67%) compared to early-onset cancer patients (35%, p = 0.6) [64].

Matching systemic therapy regimens based on ctDNA molecular testing may lead to improved treatment outcomes. For example, a study featuring 80 patients who underwent systemic treatment for biliary tract cancers showed significantly prolonged PFS (HR = 0.60 [0.37–0.99], p = 0.047) and higher rates of disease control (61% vs. 35%, p = 0.04) for patients whose therapy were molecularly matched to ctDNA and/or tissue-DNA genomic profiling compared to those with unmatched regimens [63]. Following targeted inhibitor treatment, serial ctDNA measurements can also provide insight into mechanisms of acquired resistance. For example, Varghese et al. (2021) [65] and Goyal et al. (2017) [66] have shown acquisition of new mutations for patients with metastatic iCCA on FGFR-targeting treatments, while Cleary et al. (2022) [67] has shown identification of secondary IDH1 and acquired IDH2 mutations following treatment with ivosidenib. Given that resistance may occur due to clonal evolution as well, single site biopsy results may not be reliable in capturing polyclonal states as ctDNA.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most lethal cancer worldwide and the most common cause of liver metastasis for young males [1, 3]. About 30–50% of patients with CRC experience liver metastasis, with a 10-year survival of only 5% [68]. Traditional biomarkers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), are limited by low sensitivity and specificity in detecting CRLM [69]. In contrast, ctDNA has been shown to have high sensitivity rates across all stages of CRC [70].

Recently, the landmark DYNAMIC trial showed that ctDNA-guided management was

noninferior to standard management for adjuvant therapy following curative-intent

surgery for stage II CRC with respect to two and five-year RFS (Table 1)

[28, 71, 72]. For example, five-year RFS was 88% for the ctDNA-guided group, which

was similar to 87% in the standard management group (difference 1.1%, 95% CI:

–5.8%–8%) [72]. Five-year OS was also similar between the two groups (93.8%

vs. 93.3% for ctDNA vs. standard, HR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.47–2.37, p =

0.887) [72]. Long-term follow-up of these trials showed the significance of ctDNA

clearance at time of adjuvant therapy completion, as patients with ctDNA

clearance had a much higher RFS (85.2%) compared to those with ctDNA persistence

(20%) (HR: 15.4, 95% CI: 3.91–61.0, p

Similarly, a study featuring 48 patients with CRLM with paired pre- and post-hepatectomy ctDNA showed that negativity of ctDNA following hepatectomy, whether ctDNA+/– or ctDNA–/–, is associated with improved RFS compared to ctDNA+/+, after adjusting for prehepatectomy chemotherapy, synchronous disease, and presence of 2+ CRLM (ctDNA+/–: HR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.08–0.53; ctDNA–/–: HR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.08–0.56) [74]. These findings have led to a single-institution, risk-stratified, prospective trial evaluating ctDNA-directed chemotherapy for patients with following hepatectomy for CRLM (NCT05062317) (Table 3). Likewise, another study by Wehrle et al. (2023) [75] showed an association with positive postoperative ctDNA and increased likelihood of disease recurrence (p = 0.090). A study by Bolhuis et al. (2021) [76] showed early evidence for this relationship—detectable postoperative ctDNA was associated with shorter median RFS (4.8 vs. 12.1 months) and lack of response on pathology. Overall, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Wullaert et al. (2023) [13] summarized supporting evidence for ctDNA as a prognostic marker, as the presence of ctDNA following surgery had a hazard ratio of 3.12 (2.27–4.28, 95% CI) for recurrence and 5.04 (2.53–10.04, 95% CI) for overall survival.

| NCT | Study Title | Study Type | Liver Cancer Type | Intervention | Sample Size | Study Dates | Outcome Measures | Sponsor |

| NCT06300463 | Platform Study of Immunotherapy Combinations in Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases | Interventional | CRLM | Three arms: | 24 | March 26, 2024–March 2027 | Primary: Mean CD8: Treg ratio, as determined by flow cytometry of tumor tissue, at time of surgical resection in each treatment arm | Weill Medical College of Cornell University |

| (1) Botensilimab + Balstilimab | ||||||||

| (2) Botensilimab + Balstilimab + AGEN1423 | Secondary: Number of Treatment-Related Adverse Events (TRAEs) as assessed by CTCAE v5.0 per treatment arm, Pathological Response Rate Per Arm, Radiographic Response Rate Per Arm, Number of Participants Per Arm with ctDNA Clearance | |||||||

| (3) Botensilimab + Balstilimab + Radiation | ||||||||

| NCT06225843 | Sotevtamab (AB-16B5) Combined With FOLFOX as Neoadjuvant Treatment Prior to Resection of Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastasis (EGIA-003) | Interventional | CRLM | Drugs: Sotevtamab and FOLFOX | 17 | February 15, 2024–June 2025 | Primary: Rubbia-Brandt score at surgery, Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events | Alethia Biotherapeutics |

| Secondary: Objective Response Rate (ORR), Quantity of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), Sotevtamab concentrations in plasma, Presence of ADA (anti-sotevtamab antibodies) | ||||||||

| NCT06199232 | Targeted Treatment Plus Tislelizumab and HAIC for Advanced CRCLM Failed From Standard Systemic Treatment | Interventional | CRLM (who underwent ctDNA genotyping) | Drugs: HAIC+ Targeted therapy + PD-1 inhibitor | 47 | January 23, 2024–January 23, 2027 | Primary: PFS rate at 6 months | Peking University |

| Secondary: PFS, OS, Intrahepatic PFS, ORR, DCR, Number of patients with treatment-related adverse events | ||||||||

| NCT06111105 | GUIDE.MRD-01-CRC: Clinical Validation and Benchmarking of Top Performing ctDNA Diagnostics - Colorectal Cancer | Observational | CRLM | Curative-intent resection and candidate for adjuvant chemotherapy | 590 | August 1, 2023–July 31, 2030 | Primary: Collection of clinical plasma samples at relevant time points for ctDNA diagnostics | Claus Lindbjerg Andersen |

| Secondary: 3-year recurrence-free survival, Lead time between ctDNA detection and clinical recurrence, Prognostic value of ctDNA analysis at relevant time points | ||||||||

| NCT05815082 | ctDNA-guided Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Liver Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer | Interventional | CRLM (patients with post-operative ctDNA negative only) | Two arms: (1) Surveillance (2) FOLFOX chemotherapy regimen, single-agent 5-FU/LV, capecitabine, or combination with targeted therapy |

490 | March 20, 2023–February 20, 2033 | Primary: 3-year progression-free survival, 5-year progression-free survival Secondary: 3-year overall survival, Complications |

Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University |

| NCT05797077 | Postoperation Maintenance Therapy for Resectable Liver Metastases of Colorectal Cancer Guided by ctDNA | Interventional | CRLM (patients with post-operative ctDNA positive only) | Two arms: (1) Colorectal resection surgery + FOLFOX chemotherapy regimen + Capecitabine maintenance (2) Colorectal resection surgery + FOLFOX chemotherapy regimen |

346 | February 20, 2023–February 20, 2031 | Primary: 3-years Progression Free Survival, 5-years Progression Free Survival Secondary: 3-years overall survival, 5-years overall survival, Complications |

Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University |

| NCT05787197 | ctDNA in CRC Patients Undergoing Curative-intent Surgery for Liver Metastases (CLIMES) | Observational | CRLM | Curative-intent surgical resection + chemotherapy | 232 | January 9, 2024–June 30, 2027 | Primary: Disease-free survival (DFS) Secondary: Number of event-free survival (EFS) in patients who undergo curative-intent resection of CRLM, Overall survival (OS) n patients who undergo curative-intent resection of CRLM, Time to surgical failure (TSF) in patients who undergo curative-intent resection of CRLM, Prognostic value of ctDNA, Prognostic factor(s) for disease recurrence and survival, Association between ctDNA and clinical features |

GERCOR - Multidisciplinary Oncology Cooperative Group |

| NCT05755672 | On-treatment Biomarkers in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer for Life (On-CALL) | Observational | CRLM | Treatment with curative intent: Chemotherapy and/or resection | 100 | March 1, 2023–March 2033 | Primary: Follow-up examination of tumor remission, progression or recurrence from histological samples (tumor tissue targeted deep sequencing) and ctDNA analysis Secondary: Quality of life changes (EORTC-QLQ-C30 and EORTC-QLQ-CR29) prior to and after neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant treatment. |

Region Skane |

| NCT05677113 | A Study of QBECO Versus Placebo in the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer That Has Spread to the Liver (PERIOP-06) | Interventional | CRLM | Two arms: (1) QBECO (2) Placebo |

115 | August 30, 2023–February 1, 2030 | Primary: 2-year Progression-Free Survival (PFS) rate Secondary: Clearance of ctDNA, Side-effect profile of QBECO, Quality of recovery, Five-year overall survival |

Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre |

| NCT05579340 | Postoperative Exercise Training and Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastasis (mCRC-POET) | Interventional | CRLM | Surgical resection, adjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy, and exercise training | 66 | April 2023–April 2025 | Primary: Change in peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak) Secondary: 3-years recurrence-free survival, 3-years overall survival, Changes in Aerobic Capacity, Changes in Muscle strength, Changes in Functional performance, Changes in Body composition and anthropometrics, Changes in Systolic/Diastolic Blood pressure, Changes in Heart rate, Changes in Blood biochemistry, Changes in Cytokine levels in blood, Changes in Immune cells in blood, Changes in Osteonectin, Changes in Patient-reported symptomatic adverse events, Changes in Health-related quality of life, Changes in Depression, Changes in Anxiety, Changes in Physical activity, Changes in Circulating tumor DNA, Changes in DNA methylation, Changes in treatment tolerance, Postoperative hospital admissions, Postoperative complications |

Rigshospitalet, Denmark |

| NCT05398380 | Liver Transplantation for Non-resectable Colorectal Liver Metastases: Translational Research | Interventional | CRLM | Liver transplantation | 35 | January 1, 2022–December 31, 2026 | Primary: Five years overall survival Secondary: 1 and 3 year overall survival, 1, 3, and 5 year recurrence free survival, Number of patients that drop-out of the study prior to receive intervention, Patterns of cancer recurrence after liver transplantation, Changes in quality of life assessed by EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire Other: Percentage of intratumoral genetic heterogeneity of metastatic liver via scRNA-sequencing, percentage of patients with ctDNA (pre-chemotherapy, pre-transplantation, every 3 months after transplantation) |

Hospital Vall d’Hebron |

| NCT05240950 | Anti-CEA CAR-T Cells to Treat Colorectal Liver Metastases | Interventional | CRLM | Anti-CEA CAR-T Cells | 18 | August 25, 2022–December 25, 2026 | Primary: Incidence and severity of adverse events, recurrence by ctDNA MRD detection or imaging diagnosis, 2-year RFS rate based on imaging Secondary: Pharmacokinetics (PK) indicator (Cmax or AUC) |

Changhai Hospital |

| NCT05068531 | Early Detection of Treatment Failure in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients (eDetect-mCRC) | Observational | CRLM | Resection + FOLFOX-based preoperative neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy | 100 | September 1, 2022–October 2026 | Primary: Radiological response to pre-operative chemotherapy, Biochemical response to pre-operative chemotherapy, Pathological response to pre-operative chemotherapy, Tumor response to pre-operative chemotherapy, Histopathologic growth pattern, Post-operative minimal residual disease, Time to radiological recurrence, Time to biochemical recurrence, Time to tumor recurrence as assessed by detection or change in level of circulating tumor DNA Secondary: Incidence and grade of FOLFOX-induced neuropathy, Incidence of allergic reaction to oxaliplatin, Incidence of hospitalization for febrile neutropenia, Ninety-day post-surgical complications, Disease-specific survival |

Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal |

| NCT05062317 | ctDNA-Directed Post-Hepatectomy Chemotherapy for Patients With Resectable Colorectal Liver Metastases | Interventional | CRLM | Two arms: (1) Capecitabine or 5-fluorouracil (2) FOLFOX (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin) or FOLFIRI (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and irinotecan) with or without bevacizumab |

120 | April 26, 2022–February 28, 2026 | Primary: 1-year RFS rate following liver resection of CRLM with curative intent among ctDNA negative patients who receive risk-stratified post-operative chemotherapy. Secondary: RFS following liver resection of CRLM in ctDNA positive patients, OS following liver resection among ctDNA negative and positive patients, proportion of ctDNA negative at 1-year post-resection, survival of ctDNA negative patients undergoing ctDNA-guided postoperative chemotherapy to historical controls, proportion of patients in each arm who change chemotherapy in response to ctDNA measurement, delineation of pattern of disease recurrence, ctDNA sensitivity and specifcity for predicting disease recurrence, evaluation of MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI-GI) during course of postoperative therapy, evaluation and correlation of patient molecular subtypes and characterization of tumor biologic factors associated with ctDNA detection, surgery-related adverse events up to 90 days post-operatively, chemo-related adverse events up to 30 days following last dose of chemotherapy. |

M.D. Anderson Cancer Center |

| NCT03223779 | Study of TAS-102 Plus Radiation Therapy for the Treatment of the Liver in Patients With Hepatic Metastases From Colorectal Cancer | Interventional | CRLM | TAS-102 + Radiation | 56 | October 13, 2017–January 2025 | Primary: Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD), Duration of Local Control Secondary: Toxicity associated with TAS-102 combined with SBRT, PFS, OS, Association between KRAS or BRAF mutation status with local control, Serial ctDNA measurements |

Massachusetts General Hospital |

| NCT06227728 | Analysis of PD-L1, TMB, MSI and ctDNA Dynamics to Predict and Monitor Response to Immunotherapy in Metastatic Cancer | Observational | Stage IV cancer with known metastases (lung, colorectal, breast, gastric, etc.) | Drugs: Immune checkpoint inhibitors | 50 | March 22, 2024–December 31, 2026 | Relationship between ctDNA dynamics and clinical response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), Compare and combine ctDNA dynamics and RECIST1.1 to predict clinical response in case of pseudoprogression, Investigate the prognostic value of ctDNA clearance with PFS and OS, Compare the prognostic values of PD-L1, TMB and MSI in predicting clinical response to ICI, best indicator(s) for ICI response | Gene Solutions |

TMB, tumor mutational burden; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; FOLFOX, folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin; HAIC, hepatic artery infusion pump; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; scRNA, small conditional RNA; FOLFIRI, fluorouracil, leucovorin, fluorouracil, irinotecan; TAS, trifluridine/tipiracil; SBRT, sterotactic body radiation therapy; MSI, microsatellite instability; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor.

There are ongoing studies assessing selection criteria for liver transplant for colorectal liver metastasis based on novel pre-transplant protocols, including suggestions that ctDNA may help assess disease burden prior to transplantation [77, 78, 79]. This suggestion has not yet been validated but is of interest in guiding patient selection in this relatively novel disease approach.

In terms of mutational landscape, ctDNA can also provide insight into mutations or genetic alterations driving CRLM. In the same study of 51 CRLM patients by Wehrle et al. (2023) [75], the most common mutations detected on ctDNA in the were TP53 (57%), APC (53%), KRAS, (37%) and EGFR (24%). Another study by Shi et al. (2022) [80] similarly found KRAS, APC, and TP53 to be the most commonly altered genes among 41 patients with metastatic CRC. Such patterns are in line with mutational profile analyses conducted on tissue for CRLM [81, 82]. Additionally, alterations on ctDNA have been shown to be associated with therapeutic response, as patients with low-KRAS mutational burden had improved response rates, PFS, and OS within the Shi et al. (2022) study [80]. On an epigenetic level, methylation status of certain gene promoters have also been used for diagnostic, prognostic, and monitoring purposes. A few examples of commercially available tests that detect altered promoter methylation patterns include the Epi proColon (SEPT9) [83], ColoDefense (SEPT9, SDC2) [84], SpecColon (SFRP2, SDC2) [85], and TriMeth (C9orf50, KCNQ5, CLIP4) [86]. Compared to standard diagnostic tumor biomarkers (e.g., CEA, CA19-9), methylation markers SEPT9, DCC, BOLL, and SFRP2 were shown to have a stronger correlation with tumor volume and operability [87].

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is an aggressive solid tumor with poor prognosis and high recurrence rates. It is the sixth leading cause of cancer mortality in both sexes, accounting for 5% of all cancer deaths globally [1]. A significant challenge in improving outcomes in PDAC is early detection of primary tumors and metastases. One study investigating ctDNA via ddPCR found higher rates of ctDNA detection in patients with occult metastases (41% vs. 14.6%, p = 0.001) compared to patients without occult metastases [88]. In fact, ctDNA was determined to be an independent predictor of occult metastases (OR: 3.113, p = 0.039) with a sensitivity of 66.7% and specificity of 81.6% [88].

In terms of survival, ctDNA has been found to be independently associated with

worse OS and PFS on multivariable analysis of 104 patients with advanced

pancreatic cancer and liver metastasis (HR = 3.1, 95% CI = 1.9–5.0, p

For clinical management, ctDNA-guided treatment is now being explored following upfront resection of PDAC in the AGITG DYNAMIC-Pancreas trial. Preliminary results show association of ctDNA with earlier recurrence, as patients with positive ctDNA 5 weeks following tumor resection had a lower median RFS compared to ctDNA negative patients (13 vs. 22 months, HR: 0.52, p = 0.003) [94].

Regarding mutational landscape, ctDNA whole exome sequencing has been used to identify unique molecular profiles in patients with aggressive pancreatic cancer and those with liver metastasis. In particular, enrichment of somatic mutations in KRAS, LAMA1, FGFR1, and IFF01 in tumor cells and mutations pertaining to the adaptive immune response (HLA-H, HLA-DRB1, TRBV6-7) have been noted on ctDNA for pancreatic cancer with liver metastasis [95]. Concurrent KRAS copy number gains and somatic mutations on ctDNA have also been associated with extremely poor overall survival for patient with PDAC and metastatic liver lesions [96].

Lung cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and primary cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide (18.7%) [1]. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 85% of lung cancer cases [97]. Approximately 15% of patients with NSCLC have metastasis to the liver, which is associated with the worst prognosis and resistance to targeted therapy against epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [98, 99]. According to the National Cancer Comprehensive Network (NCCN) guidelines, ctDNA testing is warranted for patients with advanced NSCLC who are deemed medically unfit for invasive tissue sampling, have insufficient tissue sample for analysis, or uncertain timing of tissue acquisition. Sensitivity and specificity of ctDNA for NSCLC are 70–94% and 90% respectively [100, 101, 102].

Noninvasive versus Invasive Lung Evaluation (NSCLC) features the most extensive collection of ctDNA related studies. In the

NILE trial, ctDNA was shown to have a 100% positive predictive value and greater

than 98.2% concordance with tissue for FDA-approved targets (e.g.,

EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF) in 34 patients with

ctDNA testing prior to treatment of metastatic NSCLC [103]. Additionally, ctDNA

was shown to be noninferior compared to standard-of-care tissue genotyping for

identifying guideline-recommended biomarkers while decreasing median turnaround

time (9 vs. 15 days, p

A few studies have investigated the use of ctDNA specifically in the context of liver metastasis for lung cancer. One study noted that concordance of therapeutically targetable mutations on ctDNA with tissue-based genotyping results was highest for patients with liver metastases (100%, 13/13) compared to patients with metastatic disease to other sites (46.2% concordance), indicating promising potential for the clinical applicability of ctDNA-guided treatment for this patient population [107]. When surveying the mutational landscape of 115 patients with NSCLC and liver metastasis, Zhao et al. (2024) [108] identified TP53 and EGFR as the most frequently altered genes on ctDNA. This is consistent with findings from Jiang et al. (2021) [109], who found TP53 and EGFR to be the most commonly mutated genes for lung adenocarcinoma with liver metastasis. Interestingly, this group also noted higher similarity in mutational and copy number between paired primary lesions and metastases in patients with liver metastases compared to those with brain metastases, indicating a more linear progression model for hepatic metastatic lesion development [109]. Another study by Lam et al. (2021) [110] found that visceral metastasis (hepatic, adrenal, renal, or splenic) was associated with increased ctDNA VAF and greater tumor burden. Their discussion highlights a hypothesis regarding decreased clearance of ctDNA in hepatic metastasis specifically, potentially leading to high ctDNA VAF [110].

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in female patients globally, with the liver being third most common site of metastasis [1, 111]. Several studies have explored the utility of ctDNA in the context of breast cancer at various stages of treatment. For example, a study following 283 patients with a tumor-informed approach found that ctDNA positivity was a notable adverse prognostic factor for distant RFS for both triple negative (TNBC) and hormone receptor (HR)-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative cancer subtypes [112]. Interestingly, ctDNA concentration was found to be strongly associated with pathologic complete response and residual cancer burden in TNBC specifically [112]. The I-SPY2 trial results also support the use of ctDNA as a tool for guiding de-escalation of therapy, as early ctDNA clearance at 3 weeks following treatment initiation predicted good outcomes [113]. Another multicenter trial (plasmaMATCH) showed a high sensitivity of digital PCR ctDNA testing (93%) and high concordance rate with targeted sequencing (96–99%) [114]. Among 1044 patients, 533 (51.1%) were identified to have potentially targetable mutations (e.g., PIK3CA, ESR1, HER2, AKT1, PTEN). Additionally, patients who underwent ctDNA guided treatment (neratininb for HER2 mutant and capivasertib for AKT1 mutation) were found to have comparable durable responses to those who received treatments based on tissue testing [114].

For liver metastasis specifically, one multicenter study featuring 223

metastatic breast cancer patients (NCT05079074), of which 30.9% (72/233) had

liver metastasis, demonstrated prolonged PFS for patients with no alterations

detected on pre-treatment ctDNA compared to patients with at least 1–2 or 3–4

alterations on ctDNA (6.63 vs. 5.70 vs. 4.90 months respectively, p

Evaluation of ctDNA has also been used to study tumoral genetics and resistance patterns in breast cancer. One study surveying the ctDNA mutational landscape in Chinese women with breast cancer found the most prevalent mutated genes to be PIK3CA (24%), TP53 (43%), and ERBB2 (14%) [117]. They also identified significant associations between cfDNA yield and cancer stage (p = 0.033, r = 0.9) [117]. A proof-of-concept study featuring a ER+/HER2+ patient with mixed invasive ductal-lobular carcinoma showed the ability of ctDNA to capture mutations present in the primary tumor and/or liver metastasis, while primary tumor biopsy sites failed to reliably identify all mutations in the metastasis [118]. Another study evaluating paired plasma and tissue samples from 40 HR+ early-stage breast cancer patients found a broader mutation spectrum with ctDNA compared to tissue DNA, while maintaining dependable assessments of microsatellite instability, tumor mutational burden, loss of heterogeneity, and homologous recombination deficiency [119]. Significantly, ctDNA was able to detect mutations in ESR1 early—potentially identifying patients who are at risk for resistance to endocrine therapy—along with mutations in DNA damage response and proliferative signaling pathways [118]. For example, one patient who had tumor recurrence and liver metastasis had mutations in PIK3CA, ESR1, and TP53 [119]. A separate study with whole genome sequencing from ctDNA in two HR+/HER2- breast cancer patients with liver metastasis identified similar driver mutations (e.g., PIK3CA, ESR1) and convergent evolution for drug resistant mutants following endocrine therapy [120].

Several challenges remain for the use of ctDNA in clinical practice. Firstly, concordance between ctDNA and tissue-based DNA have shown varying rates based on cancer and platform type [29]. When possible, exploration of paired tissue sequencing may provide insight into the presence of tumor-based mutations, while also elucidating ctDNA specific mutations. Additionally, the differences in sequencing methods among commercial and research platforms for ctDNA detection and sequencing may impede comprehensive interpretation of results. Furthermore, certain somatic alterations, such as detection of fusions, are still not as accurately captured on ctDNA compared to primary tissue biopsy sequencing [121]. In the clinic, timing and administration of ctDNA testing may be logistically difficult to obtain both pre- and post-operative testing results for each patient. Furthermore, managing cost of the commercially available assays is necessary to ensure equitable access to cancer care. Given the expanding nature of this field, initial studies have featured smaller sample sizes for feasibility testing and retrospective experimental designs, leading to limitations in drawing reliable conclusions. Thus, increased recruitment, prospective studies, and incorporation into clinical trials may improve our knowledge and understanding of ctDNA and its results. Additionally, although advantages of ctDNA testing include its non-invasive nature, rapid result times, and potential for treatment de-escalation, the impact of liquid biopsy with respect to patient quality-of-life remains to be explored and will likely require investigation based on specific cancer type.

Despite these challenges, the future clinical applications of ctDNA are promising. For diagnostic purposes, ctDNA may be helpful in cancer types for which adequate tissue sampling is difficult to obtain. As prospective studies evolve for primary liver malignancies, ctDNA can be used to select neoadjuvant therapy regimens for high-risk patients and guide de-escalation of therapy by monitoring minimal residual disease. Such changes can significantly impact patient care by decreasing time to treatment, minimizing unnecessary toxicity, and tailoring targeted therapy. ctDNA-guided de-escalation of adjuvant therapy or post-treatment surveillance can also reduce overall cost of care [122, 123]. Additionally, ctDNA may identify unique, novel mutations for targeted therapy development and allow for serial monitoring of clonal evolution of tumors and development of resistance mechanisms in a dynamic manner [66, 124]. Particularly for immunotherapy, several parameters (e.g., microsatellite instability, high tumor mutational burden) are identifiable from ctDNA and can provide personalized predictive value for the benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors, as shown in the KEYNOTE 158, MYSTIC phase III, and OAK (atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer) clinical trials [125, 126, 127, 128]. On a larger scale, with a refined understanding of ctDNA results, liquid biopsy may even be considered for screening purposes, although associated ethical and cost-related challenges may arise.

For research, several avenues remain to be explored for the use of ctDNA within liver cancer. In addition to delineating mutational profiles on ctDNA, epigenomic analysis of tumor-specific methylation patterns has been preliminarily explored and warrants further investigation [129]. As highlighted above, the utility of ctDNA within patients receiving liver transplant for liver cancer also requires further investigation to ensure unwanted sources of cfDNA are not introduced by the donor organ during data acquisition and interpretation. Combining the use of ctDNA with established serum tumor biomarkers and other liver-specific factors is also an open area for investigation for clinical research for patients with cancer and those undergoing liver transplant. On a mechanistic level, research into the exact origins and biologic basis of circulating tumor cells and ctDNA may be helpful in elucidating the mismatch between ctDNA mutational profiles and tumor tissue profiles. The sensitivity and specificity of ctDNA in early-stage malignancies, including primary liver cancers, remains limited due to smaller amounts of ctDNA shedding [22, 130]. For example, large-scale ctDNA profiling of 236 HCC patients with staging data revealed a lower sensitivity for ctDNA detection for stage I-III cancers (68%, 95% CI: 62.6%–73.4%) compared to stage IV cancers (86.3%, 95% CI: 83.6%–89%) [130]. Although strides are being made to detect alterations in ctDNA for early stage cancers [22, 101, 131], further research is needed to optimize detection of localized cancers at such timepoints for diagnostic purposes. Lastly, for studies evaluating ctDNA in other primary cancer types (e.g., colorectal, pancreas, lung, breast), including subgroup analyses based on metastatic site is crucial to broadening our knowledge of the mutational landscape and tumor biology in secondary liver malignancies.

Circulating tumor DNA has several advantages for liver malignancies in the modern era, such as its non-invasive nature, quick turnaround time with results, detection of actionable mutations, and monitoring of minimal residual disease. Information generated from this tool can guide treatment decisions, such as de-escalation of therapy, initiation of targeted therapy, or treatment switches, thereby facilitating precision oncology. Barriers and challenges to consider when implementing ctDNA testing in the clinical setting include evaluating concordance with patient tumor tissue, deciding on the use of tumor-informed versus uninformed approaches, and timing of pre- and post-treatment ctDNA. As liquid biopsy platforms evolve, ctDNA will become a clinically significant tool in guiding neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy agents and timelines, while shifting diagnostic and surveillance guidelines. Future studies involving liver cancers should include larger scale studies with paired tissue sampling, while prospective clinical trials can consider integrating serial ctDNA measurements into treatment arms and subgroup analyses based on metastatic site to evaluate its full utility.

The study was conceptualized and conducted under the direction of FA and DCHK. Literature review and analysis was performed by HH and CJW. Manuscript drafting was performed by HH and CJW. NT, KS, CJ, SS, RP, JME, MWL, KH, AS, and CM contributed substantially to the acquisition of references for the work. Figures were created by KS, CJ, SS, HH, CJW, and OFK. Tables were created by HH, CJW, and PK. Critical manuscript review was performed by all authors. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We express our gratitude and appreciation for the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.