1 School of Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, TX 79430, USA

2 Cancer Center, School of Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, TX 79430, USA

3 Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, TX 79430, USA

4 Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, TX 79430, USA

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Overexpression of the MYC oncogene, encoding c-MYC protein, contributes to the pathogenesis and drug resistance of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and many other hematopoietic malignancies. Although standard chemotherapy has predominated in AML therapy over the past five decades, the clinical outcomes and patient response to treatment remain suboptimal. Deeper insight into the molecular basis of this disease should facilitate the development of novel therapeutics targeting specific molecules and pathways that are dysregulated in AML, including fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) gene mutation and cluster of differentiation 33 (CD33) protein expression. Elevated expression of c-MYC is one of the molecular features of AML that determines the clinical prognosis in patients. Increased expression of c-MYC is also one of the cytogenetic characteristics of drug resistance in AML. However, direct targeting of c-MYC has been challenging due to its lack of binding sites for small molecules. In this review, we focused on the mechanisms involving the bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) and cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) proteins, phosphoinositide-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) and Janus kinase-signal transduction and activation of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathways, as well as various inflammatory cytokines, as an indirect means of regulating MYC overexpression in AML. Furthermore, we highlight Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs for AML, and the results of preclinical and clinical studies on novel agents that have been or are currently being tested for efficacy and tolerability in AML therapy. Overall, this review summarizes our current knowledge of the molecular processes that promote leukemogenesis, as well as the various agents that intervene in specific pathways and directly or indirectly modulate c-MYC to disrupt AML pathogenesis and drug resistance.

Keywords

- MYC

- acute myelogenous leukemia

- signaling pathway

- cytokine

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most prevalent cause of leukemia-related

mortality in adults. It is an aggressive hematopoietic malignancy characterized

by abnormal proliferation of myeloid stem cells in the bone marrow and blood [1].

Most AML patients receive chemotherapy, but the prognosis is highly variable. The

5-year survival rate after chemotherapy for AML was reported as 65 to 70% for

children aged

c-MYC is a transcription factor that plays an integral role in numerous pathways

including cell proliferation, inhibition of apoptosis, protein biosynthesis, and

metabolic transformation [6]. Moreover, c-MYC overexpression promotes

leukemogenesis and drug resistance, suggesting it may be a promising therapeutic

target in AML [7] and in solid tumors [8, 9, 10]. However, there are structural

limitations to the direct targeting of c-Myc. The c-MYC protein lacks specific

binding sites for small molecules and its location in the nucleus renders it

inaccessible to monoclonal antibodies [11]. Among the clinicopathologic features

associated with AML, genomic amplification of MYC occurs in

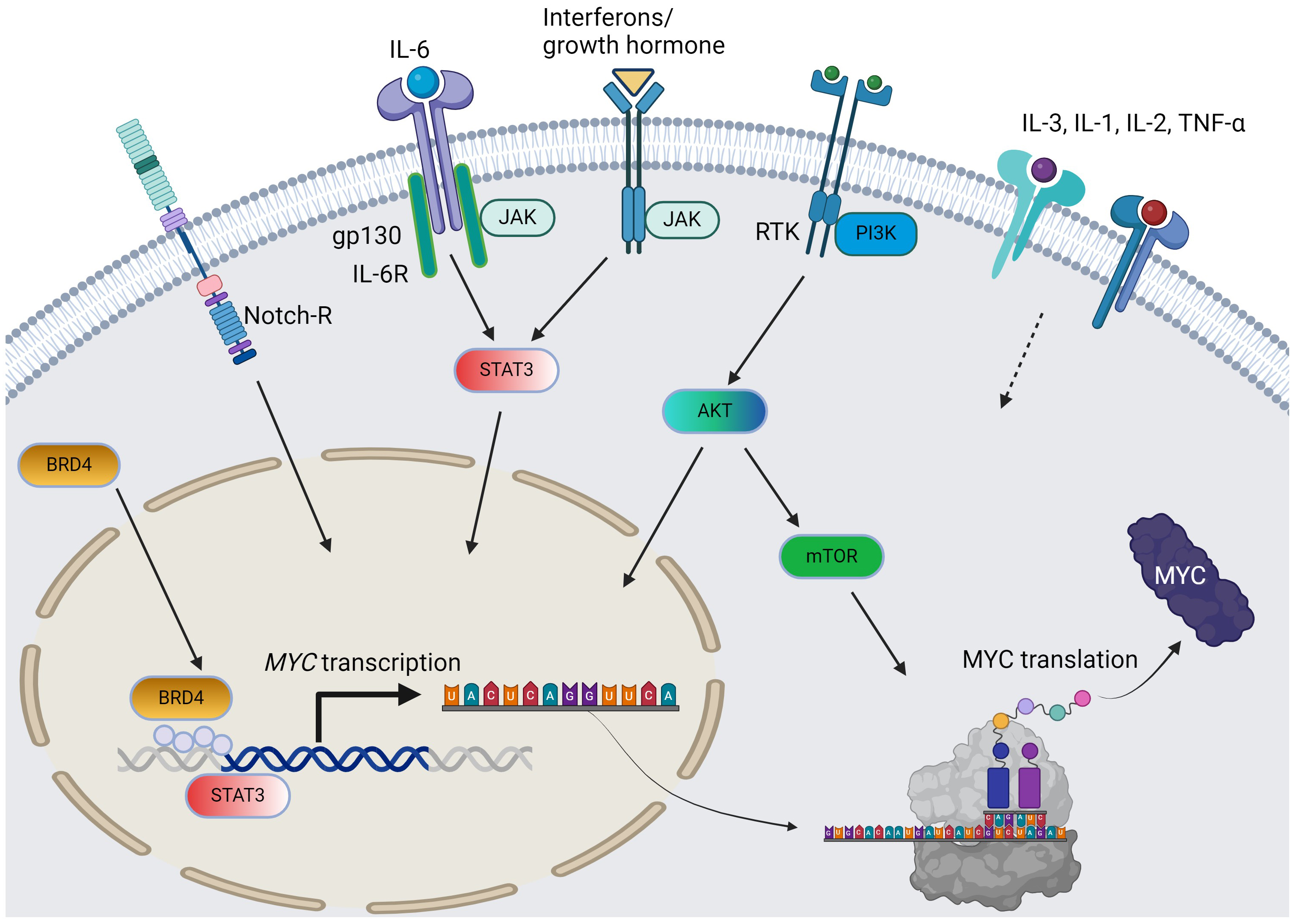

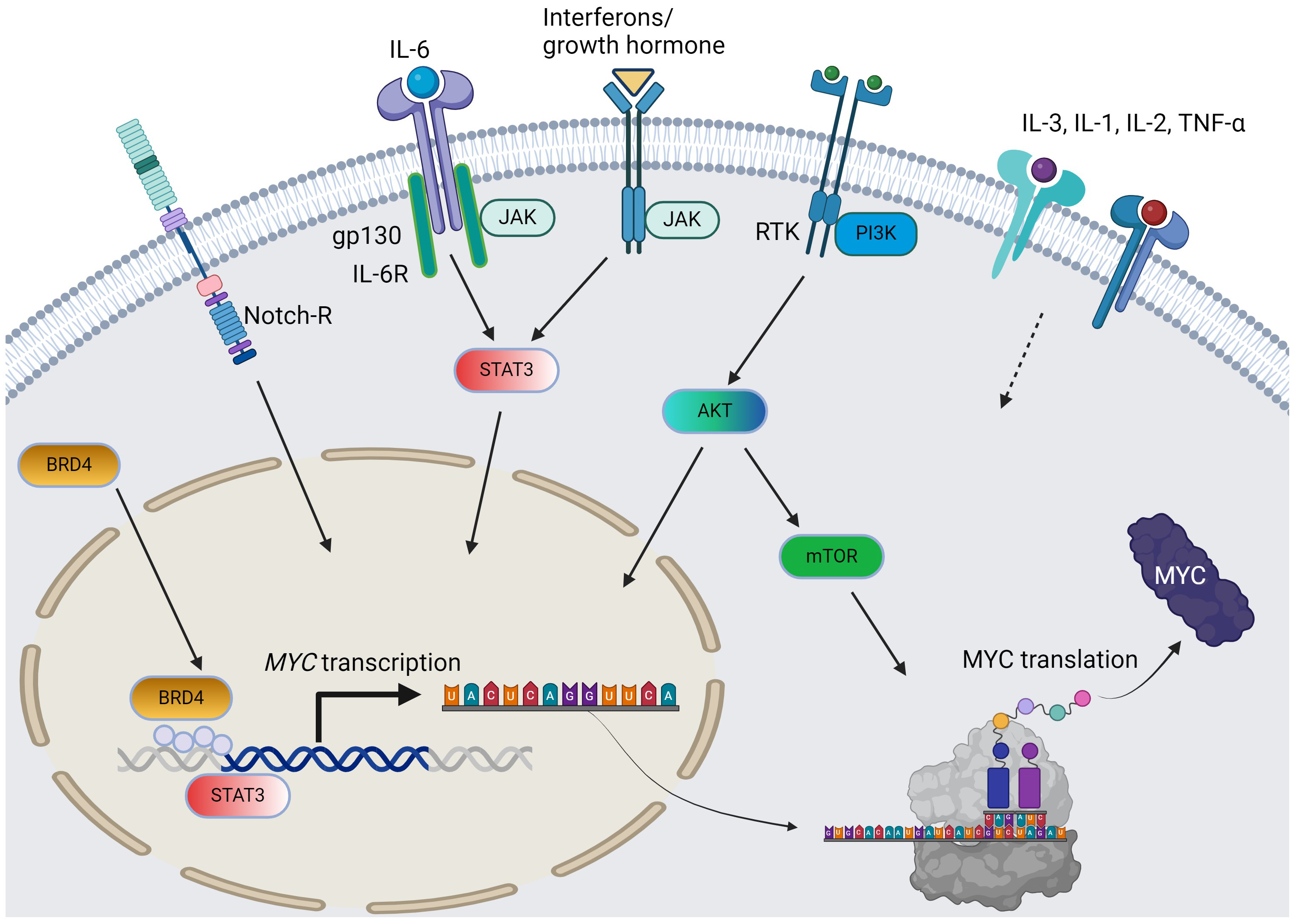

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The pathways and cytokines affecting MYC transcription and translation in AML. Solid arrow = positive regulation by known mechanisms; dotted arrow = positive regulation with unclear mechanisms; curved arrows: c-MYC protein synthesis from MYC gene. For simplicity, the JAK/STAT pathway does not distinguish per isoforms. AML, acute myeloid leukemia; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; BRD4, bromodomain-containing protein-4; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; JAK/STAT, Janus kinase-signal transduction and activation of transcription; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; AKT, protein kinase B; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin. The figure was generated using BioRender.

During status quo, the heterogeneity and poor prognosis of AML necessitates novel approaches other than conventional chemotherapy, especially given the encouraging outcomes from targeted treatment. The purpose of this review is to describe investigational agents or Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs that target molecular and signaling pathways and inflammatory responses in which MYC amplification plays a role. Furthermore, we suggest novel treatment possibilities for AML with high c-MYC expression that could potentially overcome drug resistance. Rather than reviewing genetic and molecular mechanisms of drug resistance to conventional/investigational agents, this review will assess drugs that are already approved or under investigation for the inhibition of pathways associated with high c-MYC expression in AML. Some of the agents demonstrated promising activity in AML. The efficacy of therapeutic agents from preclinical and clinical studies targeting pathways contributing to c-MYC overexpression will be evaluated.

c-MYC associates with a host of cofactors to exert its effects on target genes. To begin transcription, c-MYC often dimerizes with another family member called Max to initiate binding to the promoter region [15]. While this association seemingly offers a point for intervention, efforts to engineer small molecules to deter this dimerization have encountered hurdles in real-world applications. The small molecule 10058-F4 was developed to inhibit c-MYC and Myc-Associated Protein X (MAX) dimerization and was shown to increase the sensitivity of AML cells to cytotoxic drugs [16]. However, the results of these in vitro studies failed to be replicated in vivo because of low bioavailability and poor pharmacokinetics [17]. Due to its complicated downstream regulation of numerous cellular and metabolic functions [18], the suppression of c-MYC expression rather than its downstream signaling pathways may result in stronger moderation of oncogenic activity. The inhibition of several pathways in MYC gene transcription and translation has been studied, including the bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET), cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9), PI3K, and JAK/STAT pathways. The results of studies using pharmacological modulation of these pathways in AML are summarized below. Table 1 (Ref. [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47]) lists clinical trials of molecular and signaling transduction inhibitors in AML therapy.

| Agent | Target | Combination | Disease | Phase | Reference |

| Birabresib (OTX015) | BET protein | - | AML, DLBCL, MM, ALL | I (NCT01713582) | [19] |

| Mivebresib (ABBV-075) | BET protein | Venetoclax | AML, SCLC, NSCLC, MM, NHL | I (NCT02391480) | [20] |

| CP-0610 | BET protein | Ruxolitinib | AML, MF, MDS, MPN | I/II (NCT02158858) | [21] |

| ABBV-744 | BET protein | - | AML | I (NCT03360006) | [22] |

| JQ-1 | BET protein | - | AML cell lines | preclinical | [23] |

| Alvocidib (DSP-2033) | CDK9 | Cytarabine, Daunorubicin, Mitoxantrone | AML | I/II (NCT03563560) | [24] |

| Voruciclib | CDK9 | - | AML, CLL, DLBCL, MCL | I (NCT03547115) | [25] |

| Atuveciclib (BAY 1143572) | CDK9 | - | Leukemia | I (NCT02345382) | [26] |

| Dinaciclib (SCH 727965) | CDK9 | Gemtuzumab, Ozogamicin | AML, ALL | II (NCT00798213) | [27] |

| TG02 | CDK9 | Carfilzomib, Dexamethasone | AML, ALL, MDS, MM | I (NCT01204164) | [28] |

| CDKI-73 (LS-007) | CDK9 | ABT-199 | AML, ALL, CLL cell lines | Preclinical | [29] |

| Buparlisib (BKM120) | PI3K | - | Leukemia | I (NCT01396499) | [30] |

| Dactolisib (BEZ235) | PI3K/mTOR | - | AML, ALL, CML | I (NCT01756118) | [31] |

| Idelalisib (CAL-101) | PI3K | - | AML, NHL, CLL, MM | I (NCT00710528) | [32] |

| Gedatolisib (PKI-587) | PI3K/mTOR | - | AML, therapy-related AML and MDS | II (NCT02438761) | [33] |

| MK-2206 | AKT | - | AML | II (NCT01253447) | [34] |

| Afuresertib (GSK21110183) | AKT | - | AML, CLL, MM, NHL, CML | I/II (NCT00881946) | [35] |

| Everolimus (RAD001) | mTORC1 | Daunorubicin, Cytarabine | AML | Ib (NCT00544999) | [36] |

| Sirolimus | mTORC1 | MEC (mixoxanthrone/etoposide/cytarabine) | AML | pilot (NCT01184898) | [37] |

| CUDC-907 | PI3K, HDAC | - | DLBCL | II (NCT02674750) | [38] |

| Ruxolitinib | JAK1/2 | Decitabine, Venetoclax | AML, MPN, MDS | I/II (NCT02257138); I/II (NCT03874052) | [39, 40] |

| Fedratinib | JAK2, FLT3 | Decitabine, Ruxolitinib | AML, MPN | II (NCT04282187) | [41] |

| Pacritinib | JAK2, FLT3 | Cytarabine, daunorubicin, decitabine | FLT3-mutated AML | I (NCT02323607) | [42] |

| Lestaurtinib (CEP- 701) | JAK2, FLT3 | MEC | FLT3-mutated AML | II (NCT00079482) | [43] |

| Napabucasin (BBI608) | STAT3 | Dexamethasone, bortezomib, imatinib, ibrutinib | AML, CML, CLL, MDS, MM | I (NCT02352558) | [44] |

| OPB-51602 (SB1518) | STAT3 SH2 domain | Decitabine/venetoclax | AML, ALL, NHL, CML, MM | I/II (NCT00719836) | [45] |

| AZD9150 | STAT3 ASO | - | AML, DLBCL, NHL, MDS | preclinical | [46] |

| BP-1-107/BP-1-108 | STAT5 SH2 domain | - | AML cell lines | preclinical | [47] |

| SF-1-087/SF-1-088 | STAT5 SH2 domain | - | AML cell lines | preclinical | [47] |

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FLT3, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MF, myelofibrosis; MM, multiple myeloma; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; BET, bromodomain and extra-terminal; CDK9, cyclin-dependent kinase 9; PI3K/mTOR, phosphoinositide-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin; HDAC, histidine deacetylase; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; STAT3, signal transduction and activation of transcription 3; ASO, antisense nucleotide; MCL, Mantle cell leukemia; SH2, Src Homology 2.

Bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) proteins are promising targets in AML therapy. The BET protein family performs a vast range of cellular functions and plays a critical role in the transcriptional regulation of numerous oncogenes, including MYC [48]. Bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) from the BET protein family interacts with the promoter region to support MYC transcription and to induce tumorigenesis and downstream inflammatory cascades. Furthermore, BRD4 contributes significantly to AML maintenance via MYC activation and aberrant transcriptional elongation [49]. Hence, these findings highlight the relevance of targeting the BET family as a possible strategy to inhibit c-MYC expression.

Small molecule BET inhibitors such as JQ-1 have demonstrated strong anti-leukemic effects in AML cell lines in vitro, as well as in vivo cell-line xenograft studies [23]. Mechanistically, JQ-1 was shown to displace BRD2 and BRD4 from the MYC promoter region, thereby downregulating MYC expression [50]. Moreover, the sensitivity of AML cell lines to JQ-1 was deemed to be independent of the mechanism for MYC overexpression [23]. This suggests possible therapeutic efficacy for JQ-1 in AML treatment, regardless of the genetic basis underlying MYC overexpression. Because of the possible application of BET protein inhibitors in many hematologic malignancies, these have undergone rapid development, with several agents overcoming the solubility issues of JQ-1 and progressing to clinical trials for AML. Birabresib, the first BET inhibitor to undergo phase I clinical trials, was well tolerated without serious toxicities, and showed clinical activity in AML patients who failed or were unable to receive standard induction chemotherapy [51]. Mivebresib (ABBV-075) showed synergy with venetoclax, an inhibitor of B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), in targeting AML progenitor cells in vitro and promoting anti-leukemic effects [52]. A phase I trial of mivebresib in AML showed a tolerable safety profile and anti-tumor effects as monotherapy, and in combination therapy with venetoclax in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) AML [53]. CPI0610 is another BET inhibitor that displayed clinical activity in AML through the reduction of c-MYC expression. It also showed anti-tumor effects in a xenograft study [54], and is currently undergoing evaluation in a phase II trial for AML [55]. ABBV-744 was evaluated for the treatment of AML cell lines that had acquired resistance to venetoclax. This combination was trialed on the basis that venetoclax upregulated the expression of anti-apoptotic MCL1, and that ABBV-744 inhibits the transcription of MCL1 [56]. ABBV-744 was tested in AML xenograft models and showed comparable anti-leukemic effects to mivebresib, but with an improved therapeutic index. Furthermore, the combination of ABBV-744 and venetoclax showed enhanced anti-tumor effects compared to monotherapy [57]. However, a phase I clinical trial of ABBV-744 in patients with R/R AML (NCT03360006) was terminated for non-drug-related reasons [22].

The therapeutic effects of BET protein inhibitors in preclinical and clinical trials of AML may corroborate the feasibility of targeting c-MYC expression by modulating the transcriptional activation of MYC. Although further clinical trials are required, the promising outcomes for BET inhibitors in monotherapy and combination therapy confirm the approach of inhibiting signal transduction in the continually evolving landscape of AML treatment.

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) associate with cyclins to form complexes that play important roles in cell proliferation, replication, differentiation, apoptosis, and DNA repair [58]. Within the CDK family, cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) is a critical transcriptional regulator that is recruited by BDR4 to promote the expression of c-MYC [59]. Numerous studies have described how dysregulation of the CDK9 pathway is involved in the development of various hematologic malignancies [60]. This dysregulation stimulates cell proliferation, as well as the synthesis of anti-apoptotic factors that are essential for tumor cell survival. According to the HemaExplorer database of mRNA gene expression profiles [61], the CDK9 mRNA level in AML cell lines is significantly higher relative to its expression in healthy myeloid precursor cells. This highlights the therapeutic potential of CDK9 inhibitors in treating AML and other hematologic cancers. CDK9 is therefore considered to be an attractive target as it provides a mechanistic basis for the indirect inhibition of c-MYC expression, ultimately inducing anti-tumor effects in AML [62]. At the molecular level, CDK9 inhibitors competitively inhibit the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding site, which is a conserved region common to the CDK family. Consequently, CDK9 inhibitors also exert varying inhibitory effects on other CDKs due to their lack of specificity [63]. Moreover, CDK9 inhibitors elicit multiple effects in AML cells, such as decreased RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) phosphorylation, promotion of apoptosis, reduced expression of c-MYC, cyclin D1 and MCL-1, and the suppression of tumor growth, resulting in prolonged survival in animal models [59].

Alvocidib was the first and most extensively studied CDK inhibitor to progress through clinical trials. The mechanism of action of Alvocidib is via inhibition of the CDK9/positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) complex, which normally stimulates transcription elongation [64]. Alvocidib decreased the levels of cyclin D1, MCL-1, and BCL-2 in AML patient samples [65]. In a phase II clinical study of adult AML patients with poor prognosis, alvocidib demonstrated synergy with standard therapy comprising 7+3 cytarabine (Ara-C, continuous infusion for 7 days) and mitoxantrone (FLAM, short infusions of an anthracycline on each of the first 3 days). The complete response (CR) rate of 75% achieved for newly diagnosed secondary AML, and first relapse after short CR, were significantly higher than those of standard 7+3 therapy [66]. Although promising, the administration of alvocidib is somewhat limited by toxicity. The initial dose of alvocidib caused tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) in 28% of AML patients [67], indicating that careful measures must be taken for safety and prophylaxis. Current investigations are aimed at identifying specific biomarkers that could be used to stratify subsets of AML patients according to their likelihood of response to alvocidib [65]. Voruciclib is another CDK9 inhibitor that has been shown to decrease the level of c-MYC expression in AML patient samples and cell lines. In preclinical studies, voruciclib demonstrated synergy with venetoclax by enhancing the anti-tumor activity of venetoclax via its inhibition of c-MYC [68]. Additionally, voruciclib reduced the expression of MCL-1, thereby inhibiting the anti-apoptotic effects and venetoclax resistance conferred by MCL-1 [68]. Currently, voruciclib is being tested in a phase I clinical trial for safety and tolerability in the treatment of AML and B-cell malignancies (NCT03547115).

Atuveciclib (BAY 1143572) exhibited strong anti-CDK9 activity in preclinical studies by suppressing cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis in 7 different AML cell lines [69]. Based on the results of these studies, a phase I trial has been completed, and a phase II trial was recommended for advanced acute leukemias [69] (NCT02345382), with the results yet to be reported. Dinaciclib (SCH 727965) is an inhibitor of various CDKs, and notably CDK9. Dinaciclib induced cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and anti-tumor activity in numerous AML cell lines and mouse models [70]. The anti-tumor effects were tested in a phase II randomized trial, where dinaciclib and gemtuzumab were combined to treat R/R AML. These agents were found to promote anti-tumor activity, but the effects were transient and resulted in toxicities such as fatigue and TLS [71]. The CDK9 inhibitor TG02 demonstrated strong anti-CDK activity when administered orally [72]. TG02 promoted anti-tumor activity and apoptosis in numerous leukemia cell lines, and induced tumor regression and prolonged survival in AML murine models [72]. Phase I trials that assessed the safety of TG02 in the treatment of AML and other advanced hematological malignancies have been completed (NCT01204164), with the results yet to be reported.

The development of CDK9 inhibitors has shown rapid progress. Numerous agents have demonstrated potency in downregulating c-MYC expression, thereby inducing anti-proliferative effects in AML. Additionally, other agents such as CDKI-73 (LS-007) have shown promise in preclinical trials involving AML cell lines [29]. Although CDK9 inhibitors appear to have a promising future, a key limitation is their lack of selectivity for CDK9. Since the majority of agents also target other CDKs, this can result in undesirable side effects and suboptimal clinical efficacy [59]. Further studies are needed to determine the optimal dosing and pharmacokinetic profile of CDK9 inhibitors [59].

The phosphoinositide-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3k-Akt-mTOR) signaling cascade has been thoroughly studied as one of the pathways contributing to the upregulation of c-MYC expression in AML [73]. In addition to leukemogenesis, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is involved in metabolic alterations and plays a major role in glucose metabolism by promoting glycolysis [74]. An aberrant metabolic state is a key hallmark of malignant cells [75], which often display upregulated metabolism and increased glucose consumption to meet the higher energy demands. Consequently, tumor cells can exploit this pathway for faster proliferation, as evidenced by 60–80% of AML cases showing PI3K/AKT/mTOR hyperactivation and poor survival [76]. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR cascade has thus emerged as a therapeutic target in AML and other hematologic malignancies. Currently, various small-molecule inhibitors are under investigation with the aim of targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in the treatment of AML.

Buparlisib (BKM 120) is a pan-PI3K inhibitor that suppresses cell proliferation and reduces metabolic activity in AML by inhibiting the action of AKT [77]. Buparlisib has demonstrated effectiveness and prolonged survival in mice models, and has been evaluated in a phase I clinical study involving patients with R/R AML [78]. Although it impeded PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling and downregulated its downstream products, there was no improvement in clinical response in patients [78]. The dual PI3K and mTOR inhibitor dactolisib (BEZ235) has been assessed for its clinical efficacy. Several in vitro studies reported that dactolisib showed cytotoxicity and had the ability to enhance chemosensitivity and promote autophagy [79, 80]. However, phase I/II trials found that administration of dactolisib produced only a slight clinical response with poor tolerance, eventually leading to discontinuation [81]. Gedatolisib (PKI-587) is another dual inhibitor of PI3K and mTOR currently undergoing development. In preclinical studies, gedatolisib showed anti-neoplastic activity in solid tumor xenograft models and suppression of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, as indicated by reduced p-AKT expression [82]. The efficacy and safety of gedatolisib in treating AML was evaluated in a phase II study (NCT02438761), but this was terminated because no objective clinical response was observed. The PI3K inhibitor idelalisib has been evaluated for the treatment of various hematologic malignancies in clinical trials. Phase I trials showed that idelalisib produced strong responses and tolerability in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) [83] and in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) [84]. However, its efficacy in the treatment of AML has not yet been reported. The pan-AKT inhibitor MK-2206 was evaluated for the treatment of hematological malignancies and solid tumors in preclinical and clinical trials. Preclinical studies reported that MK-2206 inhibited the phosphorylation of AKT, thereby promoting apoptosis and anti-proliferative effects in patient samples and AML cell lines [85]. The clinical efficacy of MK-2206 was also analyzed in a phase II study of 18 patients with R/R AML [86]. Only one patient achieved complete remission, and the study was terminated for the other 17 patients due to severe disease progression. Afuresertib (GSK2110183; LAE002) is another pan-AKT inhibitor that underwent clinical trials for the treatment of blood malignancies and solid tumors [87]. In preclinical studies, afuresertib was found to suppress the phosphorylation of various AKT substrates and to induce cell-cycle arrest in the G1 phase. A phase I study conducted in two parts evaluated the clinical efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of afuresertib in various hematologic malignancies, including CLL, chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), multiple myeloma (MM), NHL, Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL), and AML [88]. Clinical response was observed mostly in the MM patients, with no response observed in the 9 AML patients.

Since the use of PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors as monotherapy has yet to produce strong and reliable clinical responses, these inhibitors were tested in combination with other targeted therapies in an effort to improve clinical outcomes and reduce toxicity. Described below are the drugs tested as single agents in AML, as well as in combination with other agents.

Uprosertib (GSK2141795), a pan-AKT inhibitor, has been clinically evaluated in monotherapy and in combination with trametinib, a MEK inhibitor that is indicated in melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer with V600E BRAF mutation as a combination with dabrafenib, for solid and hematologic cancers [89]. A phase II trial was conducted to assess the clinical efficacy of uprosertib with trametinib in 23 patients with de novo AML [90]. Analysis by Reverse Phase Protein Array (RPPA) revealed this drug combination did not significantly inhibit PI3K/AKT/mTOR or mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling. Furthermore, none of the patients achieved remission, and the study was terminated due to gastrointestinal toxicity and disease progression. Though not effective in clinical trials, other targeted or epigenetic therapies could be used together with this dual inhibition therapy to overcome compensatory signaling.

Everolimus (RAD001) is a rapamycin derivative that allosterically inhibits

mTORC1 activity in various cancer types. Currently, the FDA has approved

everolimus for the treatment of specific subtypes of lung and gastrointestinal

tumors [91]. A phase Ib trial evaluated the combination of everolimus with

chemotherapy (daunorubicin + cytarabine) for their clinical efficacy and

tolerability in AML patients aged

Another development is the application of PI3K inhibitors in combination with all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) for the treatment of a subset of AML. Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) comprises 5% of AML cases and is effectively cured by ATRA therapy [98]. However, the efficacy of ATRA in non-APL AML is limited due to acquired resistance. Combination studies of ATRA with the PI3K/mTOR inhibitor dactolisib in AML showed that the two agents triggered cell cycle arrest in G1 and loss of cell viability [98]. Furthermore, c-MYC protein levels were downregulated to a greater extent with combined treatment compared to ATRA alone [98]. Thus, inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway can enhance the efficacy of ATRA and overcome resistance. Although further studies are needed, the reduction in c-MYC levels demonstrates the therapeutic potential of PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors in combination therapy for AML.

Janus kinase signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) signaling coordinates a vast range of biological functions, including cellular proliferation, inflammation, and apoptosis [99]. The pathway operates by transducing the signal from an extracellular ligand (e.g., cytokines, growth factors) to trigger an intracellular signaling cascade [99]. Binding of the ligand causes a conformational change in the ligand receptor, which phosphorylates and activates JAKs associated with the receptor. The activated JAKs phosphorylate tyrosine residues in the receptor, forming a binding site for STAT proteins to be phosphorylated by JAKs. Finally, the activated STATs migrate to the nucleus to regulate transcription [99].

JAK-STAT signaling coordinates the survival and proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC). Dysregulation of JAK-STAT is associated with the overexpression of c-MYC, and can induce tumorigenesis and inflammatory diseases [100]. Aberrant signaling of upstream JAKs can promote the constitutive activation of downstream STATs. This is linked to the pathogenesis of AML and to poor outcomes, likely due to the constitutive activation of multiple survival pathways [101]. For instance, JAK2V617F is a point mutation that increases the activity of JAK2 and its affiliated STATs [102]. JAK2V617F is the main driving mutation present in the majority of secondary AML cases that are caused by myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) [103]. Additionally, a STRING protein-protein interaction analysis revealed that signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and STAT5 had the greatest connections to mutational drivers of de novo AML [104]. Constitutive activation of STATs can be induced by various cytokine factors and also mutations in FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) [105]. Mechanistically, FLT3 activates STAT5 to promote cellular proliferation and survival in myeloid and lymphoid development [106]. Moreover, FLT3 mutations are the most common genetic aberration in AML patients with a normal karyotype. These studies not only emphasize the importance of abnormal JAK-STAT signaling in the pathogenesis of AML, but also underscore the clinical potential of inhibiting STATs and their upstream JAKs in AML therapy.

Ruxolitinib is a JAK1/2 inhibitor that has shown efficacy in the treatment of MPNs [107], which can evolve into secondary AML. However, the heterogeneity of AML cohorts renders ruxolitinib ineffective as a monotherapy, suggesting that its efficacy needs to be enhanced by combining it with other agents [108]. The combination of ruxolitinib and decitabine, a DNA methylation inhibitor, has proven to be effective in AML mouse models [109]. Furthermore, ruxolitinib and decitabine elicited a 30–42% CR and complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery in phase I/II trials of post-MPN AML patients [110]. Despite the promising CR, the overall survival rates continue to be poor and further trial results are expected [110]. In addition, the combination of ruxolitinib with venetoclax has shown potential in mouse models and patient samples, since ruxolitinib can counteract the resistance to venetoclax caused by stromal cells [111]. Fedratinib is a JAK inhibitor that specifically targets JAK2 and FLT3 and has received FDA approval for the treatment of MPN [112]. Like ruxolitinib, fedratinib is currently being tested in combination with decitabine in phase II trials, with the results still pending. Fedratinib displayed anti-leukemic effects when applied as a monotherapy in xenograft models, as well as in combination with cytarabine [113]. Pacritinib is a multi-kinase inhibitor that displays high specificity for JAK2 and other kinases [114]. By inhibiting both JAK2 and FLT3, pacritinib helps to overcome resistance against FLT3 inhibitors and effectively suppresses the proliferation of FLT3-mutated AML cell lines [115]. Furthermore, combined therapy of pacritinib with standard chemotherapy demonstrated strong efficacy and tolerability in FLT3-mutated AML patients [116]. Similar to pacritinib, lestaurtinib is a potent multi-kinase inhibitor that targets JAK2 and FLT3 [117]. The combination of lestaurtinib and chemotherapy showed efficacy in both in vivo and in vitro studies [118], with FLT-mutated AML cells found to be highly sensitive to the combined therapy. However, this combination produced only a transient response in patients during a clinical trial [119].

JAK inhibition therefore appears to be more effective for the treatment of various AML subtypes when carried out in combination with chemotherapy and other agents. As shown in studies of FLT3-mutated AML, patients experience better treatment responses from multi-kinase inhibitors that affect pathways in addition to JAK-STAT. This highlights the importance of finding and testing novel therapies that synergize with JAK inhibitors in the treatment of AML.

While the development of JAK inhibitors has undergone great progress, other mechanisms of STAT activation exist independently of JAK-mediated phosphorylation. Therefore, direct inhibitors of downstream STATs may also serve as potential candidates for AML therapy. Constitutive activation of STAT3 or STAT5 was found in the majority of AML bone marrow and blood samples, implicating both as essential factors in AML [120, 121]. The current status and efficacy of STAT3 and STAT5 inhibitors in AML will be summarized below.

STAT3 plays a critical role in myeloid cell proliferation and leukemogenesis due to its regulatory effects on target genes such as CCND1 (for cyclin D1), MYC, and BCL2 (for BCL-2) [122]. In addition, constitutively activated STAT3 is associated with inhibition of apoptosis, adverse patient outcomes, and lower survival rates among AML patients [121]. These studies highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting upregulated STAT3 in AML.

Napabucasin (BBI608) is a small molecule inhibitor of STAT3-mediated transcription. The anti-leukemic properties of BBI608 have been demonstrated in preclinical studies and in phase I/II/III clinical trials as a single agent, as well as in combination with chemotherapy in solid tumors [123]. Administration of BBI608 resulted in a significant decrease in tumor burden in an AML xenograft model using the human AML cell line MOLM-13 [124]. Moreover, the combination of BBI608 with venetoclax produced elevated cytotoxicity in Kasumi-1 AML cell lines that were resistant to BBI608 monotherapy. Further clinical studies are necessary to substantiate the promising initial results of BBI608 in the context of AML. OPB-51602 is another small molecule inhibitor that has been evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of AML and other hematologic malignancies. Studies have shown that OPB-51602 binds competitively to specific STAT3 phosphorylation sites [125] and hinders STAT3 mitochondrial activity [126]. In a phase I trial, no significant treatment response was reported in a cohort of 20 patients, with the exception of two AML patients and one myeloma patient [127]. These suboptimal results likely stemmed from the lack of standard dosing and scheduling due to the heterogeneity of the patient cohort. Thus, further investigations of OPB-51602 are required to demonstrate consistency and efficacy in a clinical context.

The notion of targeting STAT3 expression in AML has led to the development of other strategies, such as the use of antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) inhibitors that are designed for a specific target gene. The STAT3 ASO AZD9150 was shown to decrease STAT3 expression in numerous human cancer cell lines [46]. Recent studies on AZD9150 showed that it stimulated cell differentiation in primary AML samples [128], suggesting it has potential in AML treatment. However, the efficacy of AZD9150 is currently limited to preclinical studies, and it has yet to show strong responses in clinical phases. Although the majority of development with STAT inhibitors has involved STAT3, several STAT5 inhibitors have achieved significant clinical success. Midostaurin and gilteritinib have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of FLT3-mutated AML due to their upstream effects on FLT3 kinase [129]. However, the development of resistance to FLT3 inhibition is still a problem that must be overcome.

Several other STAT5 inhibitors have also shown promise in preclinical studies. BP-107, BP-108, SF-1-087, and SF-1-088 demonstrated high specificity for the inhibition of STAT5-mediated phosphorylation [47]. Moreover, a study of several AML cell lines indicated that suppression of STAT5 caused the downregulation of target genes, including MYC, CCDN1, and MCL1 [47]. Further studies are necessary to substantiate the clinical efficacy of these STAT5 inhibitors.

Cytokines play a critical role in the disease progression of AML. The regulation

of cytokines determines the leukemia microenvironment and is a hallmark of AML.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1

| Agent | Target | Combination | Disease | Phase | Ref. |

| F16IL-2 | IL-2 | BI 836858 | AML | I (NCT03207191) | [130] |

| rhIL-2 | IL-2 | - | AML | I (NCT02781467) | [131] |

| RFUSIN2-AML1 | IL-2/CD80 | - | AML | I (NCT00718250) | [132] |

| Aldesleukin | IL-2 | - | Leukemia | I (NCT00009698) | [133] |

| IL-3 CAR T cell therapy | IL-3 | - | AML | I (NCT04599543) | [134] |

| CSL362 | IL-3R |

- | AML | I (NCT01632852) | [135] |

| DT388IL3 | IL-3 | - | Leukemia, MDS, BPDCN | I/II (NCT00397579) | [136] |

| Toclizumab | IL-6 | Idarubicin, cytarabine | AML | I (NCT04547062) | [137] |

| CYT107 | IL-7 | - | AML, CML, MDS, MPN, Cord blood transplant recipient | I (NCT03941769) | [138] |

| Biological IL-12 | IL-12 | - | AML | I (NCT02483312) | [139] |

| rhIL-15 | IL-15 | - | AML, MDS | I (NCT01385423) | [140] |

| N-803 (ALT803) | IL-15 | - | AML, MDS | II (NCT02989844) | [141] |

| GTB-3550 Tri-Specific Killer Engager phase 1&2 | IL-15/CD16/CD33 | - | AML, MDS, Mast cell leukemia, systemic mastocytosis | I/II (NCT03214666) | [142] |

| RTX-240 | IL-15TP, 4-1BBL | Pembrolizumab | AML, solid tumors | I/II (NCT04372706) | [143] |

| CAR.70/IL15-transduced CB- NK cells | IL-15 | - | AML, MDS, B-cell lymphoma | I/II (NCT05092451) | [144] |

| mbIL21-expanded Haploidentical NK Cells | IL-21 | - | AML, allogenic stem cell transplant recipient | I (NCT04220684) | [145] |

| IFN- |

IFN- |

- | AML, MDS, allogenic stem cell transplant recipient | I (NCT04628338) | [146] |

| IFN- |

IFN- |

- | AML | - (NCT03121079) | [147] |

| Peg-IFN- |

IFN- |

- | AML | I/II (NCT02328755) | [148] |

rhIL-2, recombinant human interleukin-2; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CAR T cell, Chimeric antigen receptor T cell; BPDCN, blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm. -: not applicable.

Interleukin (IL)-1 is secreted predominantly by macrophages and is a major

pro-inflammatory cytokine associated with the progression of AML. Several kinases

and proteins are associated with IL-1, each of which contributes to the

microenvironment of AML. IL-1

Another potential target that is highly expressed in AML is the IL-1 receptor

accessory protein (IL1RAP), a co-receptor in the IL-1R signaling pathway.

Knockdown of IL1RAP resulted in increased death of AML cells, thus highlighting

the clinical significance of targeting this accessory protein [152]. A recent

study also demonstrated that gene editing of IL1RAP via CRISPR-Cas9 impaired

leukemic stem cell functions that play critical roles in the proliferation,

relapse, and poor prognosis of AML [153]. Overall, IL-1

IL-2 is secreted by T helper cells and induces the proliferation of T cells, while maintaining and expanding regulatory T cells [158]. The interaction between helper T cells and foreign particles presented by antigen-presenting cells (APC) upregulates the expression of IL-2 and IL-2R [159], subsequently resulting in T cell proliferation and differentiation. The AML cell environment is associated with decreased IL-2 secretion, which contributes to poor clinical outcomes in AML patients. In the presence of primary AML cells, T cell proliferation is suppressed by inhibition of G1 to S phase cell cycle progression, even though the expression of IL-2 receptors is unaffected [160].

The T cell receptor (TCR) signal strength and the level of IL-2 signal increase

the expression of c-MYC proteins in T cells [161, 162]. Although the effect of

IL-2 on the expression of c-MYC proteins has been studied in lymphocytes, its

effect on MYC induction in AML remains to be established. The affinity

of IL-2 receptors for IL-2 serves as a prognostic factor in AML and is determined

by the combination of three IL-2 receptor subunits: IL-2R

IL-3 is produced by Type 1 helper (Th1) and Type 2 helper (Th2) cells and

stimulates the differentiation of bone marrow precursor cells, thus contributing

to the homeostasis of leukocytes. IL-3R

Although IL-2R

In IL-3-dependent hematopoietic cells, the IL-3 signaling pathway induces

MYC transcription without being notably affected by the nuclear

factor-

IL-4 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine produced by Th2 cells and that functions to stimulate T cell differentiation into Th2 cells, enhance class switching to IgE, and provide humoral immunity against helminth and allergic inflammatory diseases [175, 176]. Besides its immunological functions, IL-4 serves as a specific diagnostic marker for monocytic AML [177], suggesting it may also be a useful target against AML. IL-4 acts via the STAT6 pathway instead of the common apoptotic regulator p53. It is therefore more effective at inhibiting the growth of primitive AML than other negative regulators, such as CCL4, FGF9, WNT3a, IL-11, IL-15, and CXCL16 [178]. In another study, IL-4 showed moderate effect on normal human bone marrow [178]. Similar findings were also observed in a recent study using in vivo AML mice models. IL-4 treatment reduced the pathogenicity of AML by increasing the production of cyclopentenone prostaglandin, which is known to suppress leukemia, by upregulating hematopoietic-PGD2 synthase [179]. Although the effect of IL-4 on the expression of c-MYC in AML cells has not been thoroughly explored, it is well-documented in macrophages. Multiple studies have suggested that MAPKs play a role in the IL-4 signaling pathway in macrophages. The ERK5 (Extracellular signal regulated kinase 5) member of the MAPK subfamily promotes the differentiation of IL-4-induced, alternatively activated (M2) macrophages via c-MYC expression [180, 181]. Furthermore, a combined effect of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling and its substrate c-MYC was reported for the cell migration ability of IL-4-induced M2 macrophages [182]. Although several studies have demonstrated that IL-4 induces c-MYC expression in macrophages, more research is required to clarify the role of IL-4 in relation to c-MYC expression in AML.

IL-6 is produced by macrophages in response to infection and tissue injury and

stimulates the production of acute phase proteins such as CRP, hepcidin, and

fibrinogen, thereby contributing to hematopoiesis and immune reactions [183]. In

addition to its immune activities, IL-6 is also a potential target for

intervention. A recent clinical trial demonstrated the efficacy of Ziltivekimab,

an IL-6 ligand monoclonal antibody, in reducing various inflammatory biomarkers

associated with atherosclerosis [184]. Similarly, IL-6, along with IL-1 and

TNF-

IL-6 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), monocytes and macrophages is

negatively associated with the expression of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase

Receptor O (PTPRO), which is a negative regulator of JAK2/STAT3 involved in tumor

development [190]. In addition to their previous finding that IL-6 enhances PD-L1

expression, these authors also found that PTPRO downregulates PD-L1 by

suppressing the JAK2/STAT1 and JAK2/STAT3/c-MYC axes. PD-L1-positive tumor cells

can ultimately lead to the functional exhaustion of T cells, as observed in

various malignancies [190]. In breast cancer (BC) cells, IL-6 promotes the

expression of PIM1 via activation of STAT3. PIM plays a vital role in the

epithelial-mesenchymal-transition (EMT) and stemness of BC cells [191]. The

synergism between PIM and c-MYC in tumorigenesis can also be observed in BC. This

may serve as a guide for further investigation of PIM, a downstream substrate of

IL-6, and c-MYC as possible therapeutic targets [191]. Furthermore, a recent

study found that knockdown of karyopherin

IL-7 is a cytokine from the IL-2 superfamily that plays an essential role in the

proliferation and differentiation of B cells and T cells. Moreover, it can exert

anti-tumor effects by enhancing the CD8 response, as well as pro-tumor effects

(depending on the cellular context) via the regulation of apoptosis [193, 194, 195, 196].

IL-7 is crucial in the pathophysiology of AML due to its role in T cell

homeostasis and because T cell immunodeficiency is a common feature of AML [197].

In a clinical study, the methylation level of the IL-7 gene in the

peripheral blood of an AML patient was elevated (72.7%) compared to that of

healthy patients (3.3%), suggesting that epigenetic suppression of IL-7 may be

important in the pathogenesis of AML [198]. Furthermore, IL-7 is superior to IL-2

in enhancing the survival of T cells, and the induction of IL-7 along with other

cytokines promotes T cell activation and proliferation in AML patients by

upregulating the expression of TCR

IL-8 (CXCL8) is secreted by macrophages and is a major chemotactic cytokine that attracts neutrophils to the area of inflammation, thus mediating the acute inflammatory response [205, 206]. Similar to other pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-8 is known to be a critical mediator in AML pathophysiology. It exerts its biological activities, such as those observed in AML pathogenesis, via binding to CXCR1 or CXCR2 receptors, indicating the involvement of IL-8 overexpression in AML [207]. Further studies revealed upregulation of CXCR2 (relative to CXCR1) through the MAPK/PI3K pathway, suggesting that CXCR2 could be used as a prognostic biomarker and potential therapeutic target along with IL-8 [207]. Other studies have also confirmed that IL-8 is a prognostic factor in AML [206]. Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells (BM-MSCs) also promote cell survival and proliferation by creating a favorable microenvironment for AML cells without direct contact.

Another study revealed that IL-8 was upregulated in the microenvironment via

induction of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) through CD74 on BM-MSCs

[208]. Moreover, the MIF-PKC

Although a relationship between c-MYC and the production of IL-8 has been

demonstrated, this finding needs to be validated and reproduced in AML cells. For

example, in malignant pleural mesothelioma initiating cells (MPM-ICs),

chemoresistance is conferred by ABCB5, which is up-regulated via the production

of IL-8 and IL-1

In addition to the aforementioned cytokines, there have also been attempts to

identify other associations between cytokines and c-Myc. IL-5 induces c-MYC

expression via the activation of JAK1 and JAK2, which trigger the MYC

promoter in hematopoietic TF

AML is a highly heterogenous disease characterized by low survival rates and suboptimal outcomes after clinical treatment. Drug resistance appears to be the key reason for treatment failure in AML. The poor prognosis warrants the development of novel therapies targeting specific pathways and immune response molecules that underlie the progression of this disease. AML pathogenesis involves interconnections between numerous metabolic pathways, signaling cascades, and cytokine responses. These pathways and gene alterations are well-known mechanisms of drug resistance in AML. One of the clinicopathologic features common to these processes is the overexpression of MYC, a critical oncogene implicated in numerous cellular and metabolic functions.

The recent success of a novel treatment with an IDH inhibitor has provided further insight into targeted therapy in AML. A majority of AML patients carry mutations that constitutively activate signal transduction pathways, resulting in cell survival advantages and drug resistance. These signaling pathways involve c-MYC overexpression as a mediator of the downstream activation. Thus, the targeting of signaling pathways and inflammatory responses associated with c-MYC overexpression provides a mechanistic basis for the development of new AML therapies. The various molecular targets and signaling pathways involving c-MYC in AML include BET proteins, CDK9 proteins, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, and the JAK/STAT pathway. Furthermore, the major cytokines that induce inflammatory responses and immune cell proliferation in AML include (but are not limited to) IL-1, IL-2, IL-4, IL-7 and IL-8. This review has highlighted the current anti-AML drugs approved by the FDA, as well as those undergoing preclinical and clinical studies in monotherapy and combination trials. Importantly, the results of these studies hold the promise of better patient outcomes in response to targeted AML therapy in the years ahead.

KG and HAM collected and reviewed published manuscripts and other materials for the review. They wrote the draft of the review manuscript. MHK developed the concept and the structure of the review and revised the draft of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was funded by National Cancer Institute, NIH (R01 CA168699 to MHK), and by Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (individual investigator awards RP170470 & RP130547 to MHK).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.