1 Department of Pathology, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA

2 Cancer Science Institute, National University of Singapore, 117599 Singapore, Singapore

3 Harvard Stem Cell Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA

4 Molecular Genetics & Epigenetics Program, University of Virginia Comprehensive Cancer Center, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA

†These authors contributed equally.

§These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

The ETS transcription factor PU.1 plays an essential role in blood cell development. Its precise expression pattern is governed by cis-regulatory elements (CRE) acting at the chromatin level. CREs mediate the fine-tuning of graded levels of PU.1, deviations of which can cause acute myeloid leukemia. In this review, we perform an in-depth analysis of the regulation of PU.1 expression in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. We elaborate on the role of trans-acting factors and the biomolecular interplays in mediating local chromatin dynamics. Moreover, we discuss the current understanding of CRE bifunctionality exhibiting enhancer or silencer activities in different blood cell lineages and future directions toward gene-specific chromatin-targeted therapeutic development.

Keywords

- chromatin signature

- enhancer

- silencer

- cis-regulatory elements

- ncRNAs

- AML

- myeloid development

The purine-rich box1 (PU.1) gene locus, also known as spleen focus-forming virus (SFFV) proviral integration site 1 (SPI1), was first discovered as the integration target of the SFFV retrovirus that causes Friend erythroblastic tumors in 1988 [1]. Thirteen years later, the SFFV insertional site was found to occur within one of the most critical cis-regulatory elements (CREs), the upstream regulatory element (URE) [2, 3]. The URE exhibits cell context-dependent gene regulatory effects, functioning as either an enhancer or silencer to direct the unique expression pattern critical for PU.1 programming in blood development [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Significant progress has been made in understanding the URE-mediated chromatin architecture regulation and the repertoire of CREs involved in normal and malignant hematopoiesis.

In light of recent studies demonstrating the role of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) as enhancer regulators of PU.1 and in celebration of the 40th anniversary of the discovery of the first mammalian enhancer in SV40 [9, 10], we dedicate this review to the discussion of CRE-mediated PU.1 expression in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. To that end, we elaborate on the unique expression pattern of PU.1, which dictates its biological roles. The previous literature will then be summarized to demonstrate that the PU.1 promoter is essential but insufficient for its cell-type-specific expression. We further analyze the role of the URE and additional CREs in PU.1 expression in normal and malignant myeloid cell development. The roles of chromatin structure and architecture, as well as transcription factors (TFs) and ncRNAs acting as cell-type–specific regulators, will be discussed. Finally, we will address how genetic abnormalities affect the regulatory functions of the URE, provide perspective on potential approaches for therapeutic targeting of the URE, and address questions that warrant further studies in the future.

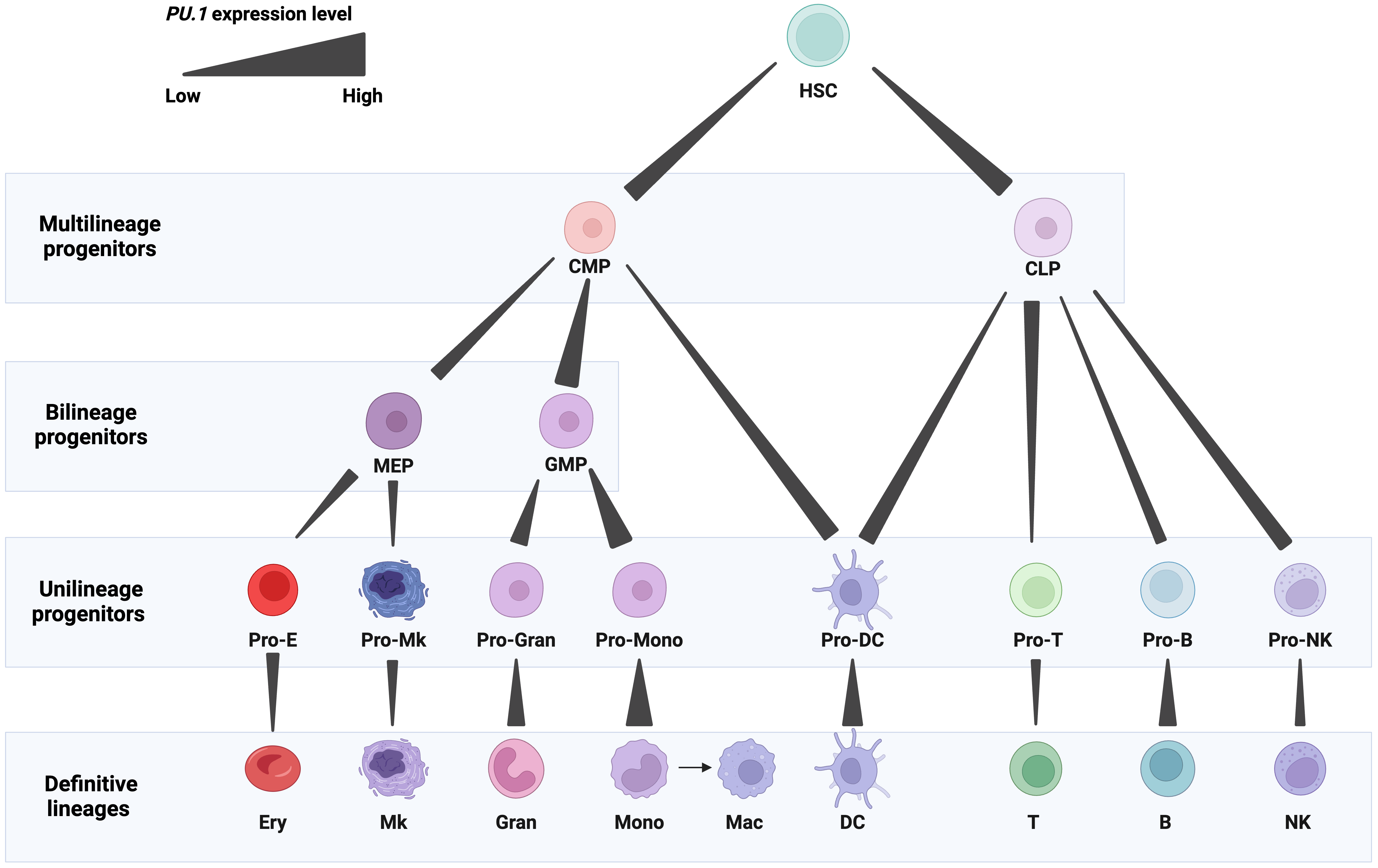

A member of the ETS-domain TF family, PU.1 plays a critical role in programming the development of several mammalian lineages. Precise spatiotemporal control of PU.1 expression is crucial for the normal generation of blood cells. PU.1 is detectable in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), and common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) [6, 11, 12]. In definitive blood cell lineages, PU.1 is expressed in diverse patterns (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Expression patterns of PU.1 in blood cell lineages. PU.1 levels are represented by gradient bars. Abbreviations: HSCs, hematopoietic stem cells; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; MEP, megakaryocytic-erythroid progenitor; GMP, granulocyte-monocyte progenitor; Pro-E, erythrocyte progenitor; Pro-Mk, megakaryocyte progenitor; Pro-Gran, granulocyte progenitor; Pro-Mono, monocyte progenitor; Pro-DC, dendritic cell progenitor; Pro-T, T cell progenitor; Pro-B, B cell progenitor; Pro-NK, natural killer cell progenitor; Ery, erythrocyte; Mk, megakaryocyte; Gran, granulocyte; Mono, monocyte; Mac, macrophage; DC, dendritic cell; T, T cell; B, B cell; NK, natural killer cell. Figures were created with BioRender.com.

High PU.1 expression is required for myelomonocytic cells, and its expression is the highest in monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs). It is essential for the development of these cells, and its high amplitude expression plays both an early role in the emergence of GMPs and a later role in the terminal differentiation of monocytes and macrophages [13, 14, 15, 16]. High PU.1 levels play a critical role in the production of macrophages, displaying an early role in the development of a multipotential myeloid precursor and a later role in the development of monocytes/macrophages as disruption of PU.1 in mice caused a complete loss of macrophages [6, 17, 18] (Fig. 1).

Low PU.1 expression is needed for granulocytic and B cells [5, 11, 19]. PU.1 is expressed in precursor and mature B cells [20]. Graded PU.1 levels are needed at different stages of B cell development. As B cells mature, PU.1 expression progressively increases, although not to the same degree as in macrophages [11]. PU.1 activates the proximal promoter of the early B cell factor 1 (EBF1) gene, which regulates the specification of the B cell fate [21]. The balance between PU.1, EBF1, and other TFs, such as E2A and Pax5, orchestrate B cell differentiation [22]. Overexpression of PU.1 in CLPs inhibited B cell development [18]. Nevertheless, deletion of PU.1 in mice resulted in a defect in the generation of progenitors of both lineages [13, 23] (Fig. 1).

PU.1 expression is reduced stepwise during early erythroid and T cell differentiation, an adjustment required for normal development of both lineages. Its expression is relatively high in CLPs and early thymic progenitors (ETPs) but fully extinguished in mature T cells [6, 24]. PU.1 downregulation occurs in the thymus during the transition between the double negative (DN) and double positive (DP) developmental stages. This downregulation is specifically required for the progression of normal T differentiation [25]. For instance, the deletion of PU.1 blocks the differentiation of uncommitted thymocyte progenitors in the fetal thymus [24]. On the other hand, PU.1 expression reduced thymocyte expansion and blocked development at the pro-T cell stage [25]. Notably, PU.1 is expressed and regulates the function of subpopulations of Th2 cells, mature T helper cells involved in humoral immunity. PU.1 interferes with GATA-3 transcriptional activities, establishes a defined cytokine profile, and contributes towards establishing the spectrum of cytokine production in these cells [26]. It is required for IL-9 expression in IL-9-producing Th2 cells (Th9), which are critical in mediating inflammation [25, 27]. Similarly, low levels of PU.1 promote the proliferation of early erythroid progenitors, yet complete suppression is required for their terminal differentiation [28, 29, 30, 31, 32]. PU.1 suppresses the differentiation of erythroid cells by upregulating the key cell cycle regulator Cdk6 expression, thereby promoting cell proliferation [29]. The inhibition of erythroid differentiation is also dictated by the antagonistic effect of PU.1 and GATA-1. PU.1 binds and inhibits GATA-1 from inducing erythroid differentiation. In turn, GATA-1 inhibits the myeloid transcriptional activity of PU.1. This molecular antagonism determines whether the CMP commits toward either a myeloid or erythroid lineage [33, 34]. Knockout of Pu.1 in mice causes a delay in T cell development and impairment in erythroblast maturation, with normal development of megakaryocyte and erythroid progenitors [13, 14].

PU.1 also regulates natural killer (NK) cell differentiation and homeostasis by promoting the production of bone marrow NK cell precursors, splenic mature NK cells, and NK cell proliferation in response to IL-2 and IL-12. Additionally, it induces the expression of the receptors for stem cell factor and interleukin (IL)-7 and the expression of inhibitory and activating members of the Ly49 family [35].

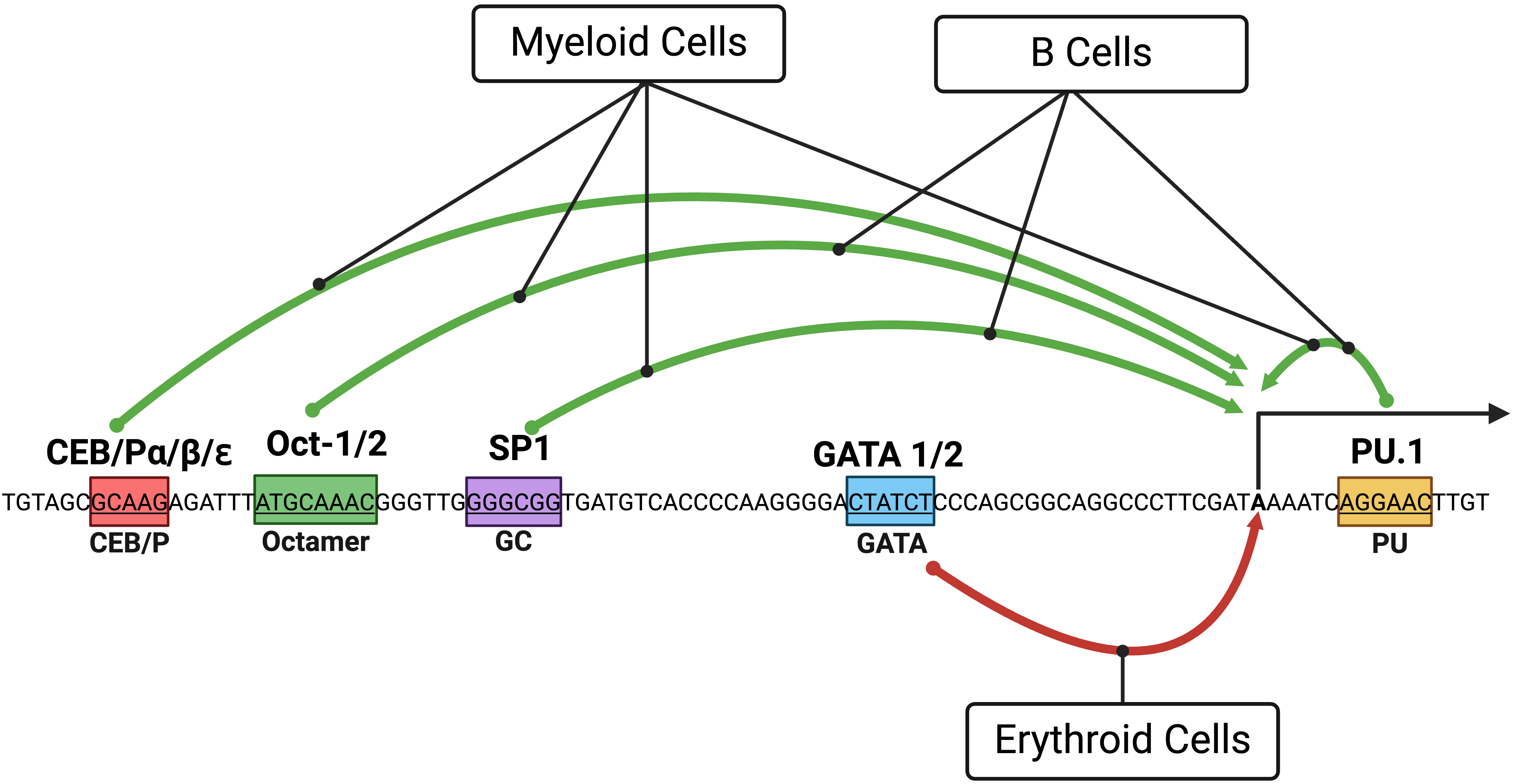

The dynamic expression pattern of PU.1 during hematopoietic development was originally thought to be directed by its promoter. The murine and human PU.1 promoters activate reporter genes in myeloid and B cells but not in T cells [36, 37]. This tissue-specificity is dictated by a core promoter region of ~120 base pairs that span a PU.1 transcription start site populated with TF binding motifs [36, 37] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.A diagram showing the PU.1 core promoter and the effects of transcription factors (TFs)

on blood cell lineages. Green and red arrows depict the induction and inhibition

of PU.1 expression, respectively. Boxes with colors represent binding

sites of TFs involved in regulating PU.1. Distances of TF binding sites

from the start site of the human PU.1 transcript NM_001080547 are

shown. Binding sites were originally studied in the murine Pu.1 promoter

, SP1, Oct1/2, and GATA-1 and human PU.1 promoter

for Oct1/2 and C/EBP

In myeloid cells, a repertoire of TFs contributes to the induction of

PU.1 promoter activity. The PU.1 protein is involved in positive

feedback regulation of the PU.1 gene through a binding site downstream

of the transcription start site [36, 37]. C/EBP family members (C/EBP

In B cells, the PU.1 protein also engages in positive feedback regulation of the PU.1 gene [37, 40]. In contrast to myeloid cells, B cells depend on Oct proteins for transactivating the PU.1 promoter, corresponding with their robust expression of Oct2 and BOB1/OBF-1 [37, 40]. As in myeloid cells, Sp1 plays only a modest role in transactivating PU.1 promoter activity in B cells [40] (Fig. 2).

In erythroid cells, GATA TFs (GATA-1 and GATA-2) bind a GATA site within the core promoter region to inhibit PU.1 expression, a finding validated in several erythroblastic cell lines [33, 41].

It is worth mentioning that many of the assays for promoter activity employed transfection of episomal reporters and that the observed effects could not be recapitulated in the chromatin context with stable expression and chromatin integration [3, 4, 42]. This indicates the presence of regulatory elements within the genome that dictate PU.1 promoter activities in different blood cell lineages.

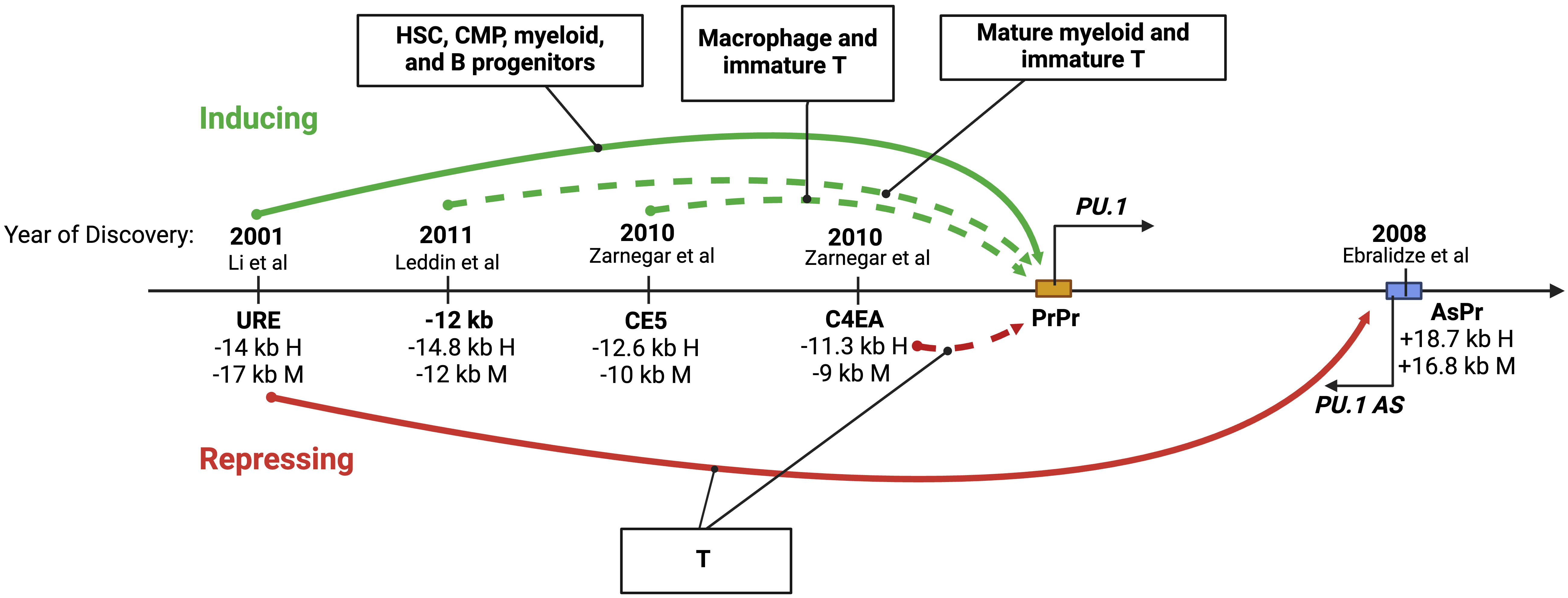

As the promoter is crucial but insufficient for driving PU.1 expression, studies over the past twenty years have identified multiple CREs that exert long-range control over the transcription of PU.1 in blood cell lineages (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.The role of distant regulatory elements within the PU.1 locus. A diagram showing upstream cis-regulatory elements (CREs) involved in long-range control and cell type-specific expression of PU.1. The solid and dotted arrows indicate studies with and without in vivo experiments in genetic mouse models, respectively. Distances in kilobases (kb) of each CRE from the PU.1 transcription start site (TSS) in human (H) and murine (M) genes are shown. The years and citations when the elements were first described are also shown. Figures were created with BioRender.com.

The URE was the first to be described [3] and remains the most well-defined CRE of PU.1. This regulatory element is highly conserved in mammalian species. It resides at –17 kb and –14 kb from the TSS in humans and murine animals, respectively [2, 3, 43]. Various in vivo experiments indicate that the URE functions as a critical enhancer of PU.1 at several cellular stages of blood cell development, spanning multipotent, bipotent, and unipotent hematopoietic progenitors and mature blood cells. More specifically, it acts within HSCs, CMPs, progenitors of myeloid cells, and mature neutrophils [5, 6, 7]. Enhancer activity of the URE in HSCs and myeloid cells has also been demonstrated by multiple techniques, including episomal and stable genomic integration approaches [2, 3, 4, 8] (Fig. 3). Moreover, chromatin architecture assays, to be discussed below, confirm a physical interaction between the URE and the PU.1 promoter. The URE might also function as an enhancer in B and erythroid progenitors as its deletion reduces PU.1 expression and cell proliferation in these cells [6, 44]. However, molecular evidence of enhancer activity in B and erythroid progenitors remains to be documented.

In contrast to its role in myeloid and B lineages, the URE functions as a silencer in T cells. Its deletion increases PU.1 levels in immature thymocytes, including ETPs and intermediate double negative T cells (DN1 and DN3); however, it has no effect in mature T cells in which PU.1 is known to be silent [6]. In addition to binding the PU.1 promoter, the URE interacts with a +18.7 kb conserved element within the PU.1 gene body, referred to as AsPr (or H3) that carries a promoter for a PU.1 antisense ncRNA (PU.1 asRNA) [45, 46] (Fig. 3). Notably, assays with episomal reporters using a pro-T-like cell line fail to recapitulate the repressive effect of the URE on the PU.1 promoter [8], highlighting the importance of both chromatin context and of using primary cells versus cell lines [6, 8]. Nevertheless, understanding how the URE functions as a silencer in progenitor T cells may require the development of a cell culture system amenable to mechanistic studies.

In addition to the URE, several less-well-defined regulatory elements have been described (Fig. 3). The –14.8 kb element (murine –12 kb) synergizes with the URE to mediate high expression of PU.1 exclusively in mature myeloid cells. This element also contributes to high-level PU.1 promoter activity ex vivo, both transiently [8] and within chromatin (stable genomic integration) in RAW264.7 macrophages but not Namalwa B cells [42]. This element also induces transient Pu.1 promoter activity in the immature murine T cell line Adh.2C2 [8]. Another putative enhancer, the –12.6 kb element (murine –10 kb, or CE5), induces transient Pu.1 promoter activity in macrophage (RAW264.7) and T (Adh.2C2) cell lines [8]. The –11.3 kb element (murine –9 kb, or C4EA) has been implicated as a silencer of PU.1 in T progenitors as it inhibits PU.1 promoter activity in the context of chromatin in the immature T cell line Adh.2C2 [8]. For most of these upstream elements, direct targeting of endogenous sequences, as has been performed for the URE in cell lines and mouse models, is required to understand their contributions to the physiologic expression patterns of PU.1 further.

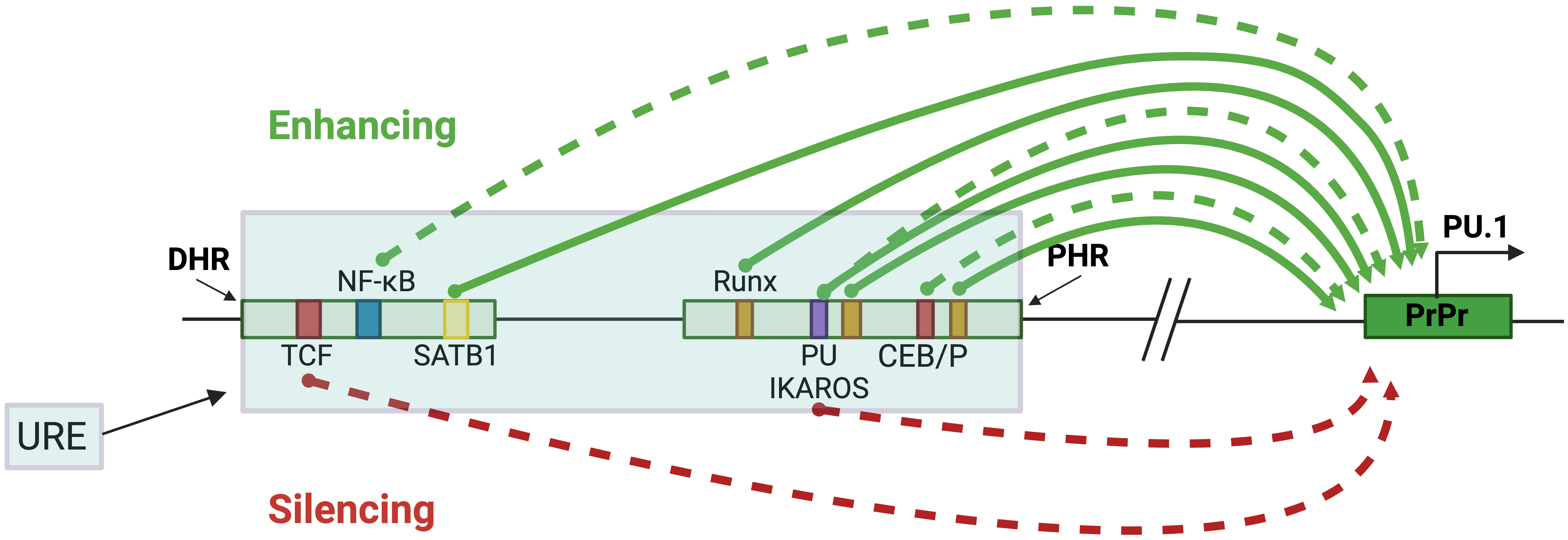

Multiple lines of evidence from genetic mouse models support the essential contribution of TFs, including lineage-determining TFs, to the opposing functions of the URE in different cell lineages. This CRE comprises two highly conserved ~300 bp homology regions called the distal homology region (DHR or H1) and the proximal homology region (PHR or H2) [2]. The PU.1 protein contributes to a positive autoregulatory loop through its binding site within the PHR region [2, 4] (Fig. 4 and Table 1 (Ref. [2, 4, 6, 39, 43, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52])). Point mutations that abrogate PU.1 binding to its binding site reduce the activity of an integrated reporter gene in myelomonocytic cell lines. In mice, the role of PU.1 binding in this positive feedback loop seems limited to HSCs and progenitor cells, as targeted disruption of the binding site reduced PU.1 expression in HSCs but not in mature macrophages [47]. RUNX1, a known regulator of PU.1, binds three conserved sites within the PHR region of the URE and induces PU.1 promoter activity in the context of chromatin. Mice with mutations disrupting these sites show a strong reduction in PU.1 in HSCs, myeloid, and B cells [4, 47]. Additionally, SATB homeobox 1 (SATB1) induces PU.1 expression in GMP and megakaryocytic-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) in mice and exerts its inducing effect by binding to an AT-rich motif at the DHR region of the URE [48].

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.URE-mediated PU.1 regulation in blood cell lineages. The blue-shaded box represents the URE, containing the PHR and DHR, which are represented by smaller, separated boxes. Their distances from the TSS are 17.2 kb and 16.48 kb, respectively. The green arrows represent induction, and the red represents inhibition. The solid and dotted arrows indicate studies with or without in vivo analyses in genetic mouse models. The colored boxes represent specific TF binding sites that regulate PU.1, and the PrPr box represents the proximal promoter. Figures were created with BioRender.com.

| Transcription factor | Binding sequence | Binding element | Blood lineage | Reference |

| TCF | CTTTGAT | DHR | Progenitor T | [6] |

| NF- |

CGGGCCTCCCC | DHR | Myeloid | [43] |

| SATB1 | TATTA | DHR | GMP, MEP | [48, 49] |

| RUNX1 | TGTGGT | PHR | HSC, myeloid, B | [4, 47] |

| PU.1 | TTCCT | PHR | HSC, progenitors | [2, 4, 47] |

| IKAROS | TTCCT | PHR | Pre-B | [50, 51] |

| CEBP/ |

CTTGC | DHR, PHR | Myeloid | [39, 52] |

An increasing number of studies also indicate a role for other TFs in the URE

activities. For example, the myeloid TF C/EBP

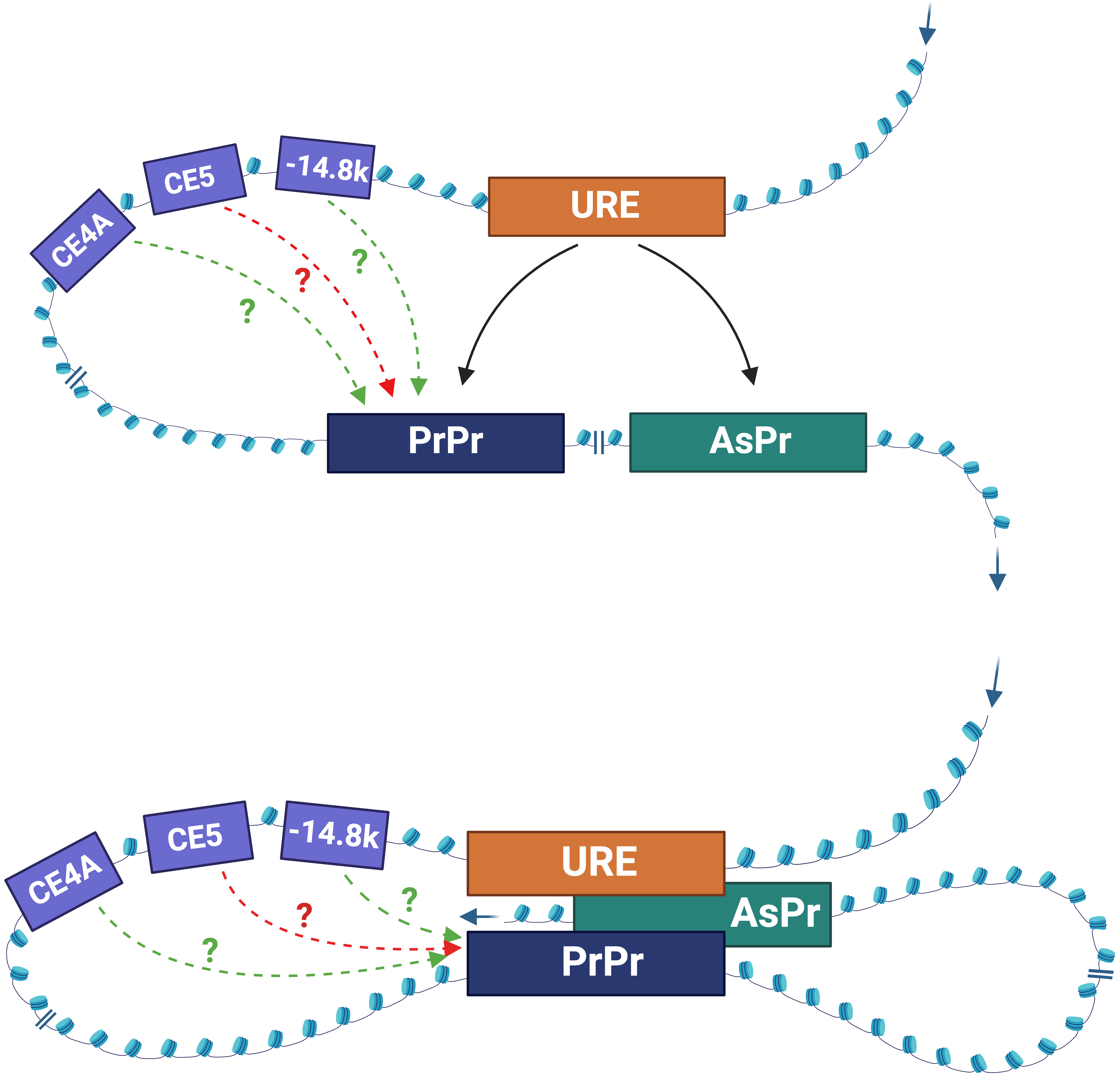

The URE is bifunctional, acting as an enhancer in myeloid cells and a silencer in T cells [5, 6, 7, 44]. How the URE communicates with the gene promoter represents a long-standing question in the enhancer research field. Histone modifications marking active enhancers, such as histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac), H3K4 monomethylation (H3K4me1), and histone H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4Me3) [53, 54], are present within the URE in myeloid cells [55, 56, 57]. Although silencers can be identified by the histone 3 lysine 27 tri-methylation (H3K27Me3) repressive and the histone 3 lysine 9 tri-methylation (H3K9Me3) heterochromatin marks [58, 59, 60], the role of these epigenetic signatures on silencer activity of the URE in T cells have yet to be investigated. Moreover, chromatin is accessible at the URE in myeloid cells [3, 8, 55, 56]. Yet, a comprehensive understanding of chromatin signatures within the URE among blood lineages remains to be achieved. Nevertheless, current evidence supports the role of physical interaction between the URE and the PrPr in the context of 3D chromatin architecture. This interaction has been demonstrated using the chromosome conformation capture (3C) assay, which measures the frequency of contacts between chromatin elements in several cell types. These include primary HSCs, marrow progenitors, macrophages [48], and myeloid cell lines [45, 46, 55, 57]. To add to the complexity and dynamic of PU.1-specific chromatin architecture, the URE was also found to interact with the AsPr residing within intron 3 in the PU.1 gene [46]. Subsequent studies have suggested that the URE is capable of switching its docking between the PrPr and the AsPr, depending on blood cell type [45] (Fig. 5). For instance, it interacts with the PrPr to induce PU.1 mRNA transcription in myeloid cells or with the AsPr to induce PU.1 asRNA transcription in T cells [45]. It is also possible that the URE simultaneously interacts with the PrPr and the AsPr in a shared topologically associating domain (TAD) [46, 57], which may include additional distal CREs (Fig. 5). However, the role of such interactions and additional elements in determining chromatin architecture and promoter interactions remains to be determined. Due to experimental limitations with current chromatin architecture assays, which require large-scale bulk populations or provide low resolution to kilobase interactions [61, 62], it is not clear if the URE–PrPr and URE–AsPr interactions occur via the meet-by-choice model or the meet-all-at-once model (Fig. 5) in individual cells at different stages of blood cell development. Nevertheless, with the pace of advancement in single-cell technologies, answering this question may become feasible in the near future.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.The models of URE-mediated 3D chromatin interactions. Meet-by-choice model (top panel). URE interacts with either the PrPr (myeloid cells) or the AsPr (T cells). Meet-all-at-once model (bottom panel). The URE, the PrPr, and AsPr interact simultaneously. CE4A, CE5A, –14.8k: less known regulatory elements. Solid arrow: interpretation with experimental evidence. Dot arrows: hypothetical interactions; green: induction; red: inhibition. Figures were created with BioRender.com.

As transcriptional activity indicated by the occupancy of polymerase II is often present at the URE [55, 56], a role for the interplay between locally originated ncRNAs and occupied TFs in URE-mediated chromatin architecture seems likely. There is evidence of the coordination between these two types of biomolecules in mediating the formation of the URE–PrPr chromatin loop. Specifically, the myeloid-specific ncRNA LOUP binds to RUNX1 molecules that occupy both the enhancer and the promoter to coordinate enhancer and promoter communications [55]. Unlike most enhancer RNAs, which are short, bidirectional, and unpolyadenylated (2D-enhancer RNAs) [63, 64], LOUP is a 1D-enhancer RNA that is unidirectional and polyadenylated. The ncRNA emanates from within the URE and extends toward the PU.1 promoter [55]. The binding of RUNX1 to all three Runx binding sites at the URE (Fig. 4) is required for chromosomal interaction between the URE and the PU.1 promoter in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells as well as myeloid cells [55, 65]. In addition, the PU.1 protein, through binding to its target site within the URE, promotes the URE–PrPr interaction that induces PU.1 transcription in HSCs and myeloid progenitors [47]. Intriguingly, this autoregulatory role of PU.1 via the URE appears to be limited to immature myeloid cells, as the PU.1 protein does not affect the stability of the URE–PrPr interaction loop in differentiated macrophages [47, 57]. Whether the binding of PU.1 to its own promoter (Fig. 2) plays a direct role in chromatin architecture modulation remains to be explored. It is likely that PU.1, RUNX1, and other TFs that bind URE and/or PrPr act in concert with ncRNAs to mediate the URE–PrPr interaction.

URE-mediated fine-tuning of graded levels of PU.1 is crucial in generating blood cell lineages. Disturbances in URE function are associated with blood malignancies. Several genetic mouse models with targeted disruption of the URE have offered insights into the role of this important CRE. Mice with isolated, biallelic loss of the URE exhibit ~80% reduction in PU.1 expression in bone marrow and develop a multilineage differentiation block, which includes accumulations of immature myeloid cells in bone marrow and spleen, T lymphoblasts in the thymus, and stimulated proliferation of B1 cells in peripheral blood. The mice developed B1 cell proliferative syndrome, T cell lymphomas, and AML [5, 6]. Interestingly, mice with uniallelic URE loss and a DNA mismatch repair-deficient background resembling the mutations acquired in aging human individuals exhibit a 35% reduction in PU.1 expression and acquire myeloid-biased preleukemic stem cells. The mice develop myelodysplastic syndromes with subsequent transformation into AML [7]. Thus, differential PU.1 dosage mediated by changes in the URE status and additional genetic changes determine pathways for leukemogenesis and lymphomagenesis.

The URE also undergoes functional disruption by trans-acting factors acting in

trans to regulate PU.1 expression in hematologic malignancies. Several

leukemia-associated fusion proteins derived from chromosomal translocations alter

its activity. In t(8;21) AML cells expressing the oncogenic fusion protein

RUNX1-ETO, chromosomal interaction between the URE and the PU.1 promoter

is abolished [45]. The RUNX1-ETO protein restricts chromatin accessibility at the

URE through local histone deacetylation and inhibits expression of the enhancer

lncRNA LOUP, which plays an essential role in the URE–PrPr interaction

and PU.1 expression [55]. In addition, RUNX1-ETO shifts the interaction

with the URE from the PrPr to the promoter of a PU.1 asRNA (AsPr),

resulting in antisense transcription and a myeloid differentiation blockade [45, 46]. In inv(16) AML cells expressing the oncogenic fusion protein

CBF

In addition to experimentally generated point mutations [4, 47, 52], naturally occurring genetic alterations within the URE can affect TF recruitment. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at the URE that occurs more frequently in patients with AML with complex karyotype prevents SATB1 binding, decreasing its enhancer activity and reducing PU.1 expression in myeloid progenitors [48]. In mice, the spleen focus forming virus (SFFV), which integrates into the URE in a site flanking the two conserved H1 and H2 regions, is implicated in causing Friend virus-induced erythroleukemia [1, 2, 67]. Thus, disruption of URE function either through the URE sequence or trans-acting factors may represent a driving force in myeloid malignancy.

Approaches to restore normal URE-mediated chromatin architecture have become feasible and could offer therapeutic utility in myeloid malignancies. For example, PU.1 expression can be induced in leukemic cells by endogenous activation of enhancer RNA using a CRISPR activation platform, in which dCAS9 is fused to the VP64 transcriptional activating domain and targeted to the promoter region of the enhancer RNA upstream of the URE [55]. Transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) fused to VP64 have been used to target the PHR region of the URE that contains the PU.1 binding site [68]. Since TFs, particularly ones with tumor-suppressing functions, harbor inherent challenges for direct therapeutic targeting [69], induction of endogenous PU.1 by CRISPR activation and TALEs holds considerable promise. However, much research and development in this space is needed. For instance, can these platforms be modified for cell type selection, i.e., to be selectively targeted in myeloid and lymphoid cells? Additionally, among PU.1 CREs, which one could be targeted and for which tumor type? Further development of tools to modulate URE-mediated PU.1 expression and renormalize chromatin architecture will likely lead to novel treatments for myeloid malignancies.

Since the discovery of the first and most important CRE of PU.1, the URE, studies over the past two decades have provided a wealth of knowledge regarding the role of CREs in the long-range transcriptional regulation of PU.1 during normal and malignant hematopoiesis. The URE and other CREs act in concert with the PU.1 promoter to mediate their regulatory function via chromatin loops that drive cell-type specific PU.1 expression. Biomolecules such as TFs and ncRNAs cooperate in assembling these complex and dynamic chromatin structures (Table 2). Genomic abnormalities that alter these biomolecules and the CREs themselves can affect functional chromatin architecture and thereby contribute to disease pathogenesis.

| Cell lineage | PU. 1 expression | ||

| CREs | URE | HSC, CMP, myeloid and B progenitors | Induction |

| T cells | Repression | ||

| –12 kb | Mature myeloid, immature T cells | Induction | |

| CE5 | Macrophage, immature T cells | ||

| CE4A | T cells | Repression | |

| URE-regulating TFs | RUNX1 | HSC, myeloid and B cells | Induction |

| PU.1 | HSC, progenitors | ||

| SATB1 | GMP, MEP | ||

| NF- |

Myeloid cells | ||

| CEBP/ | |||

| TCF | T progenitor | Repression | |

| IKAROS | B progenitor | ||

| PU.1 promoter-regulating TFs | C/EBP |

Myeloid cells | Induction |

| SP1 | |||

| Oct-1/2 | Myeloid, B cells | ||

| PU.1 | |||

| GATA1/2 | Erythroid cells | Repression | |

| ncRNAs | LOUP | Myeloid cells | Induction |

| PU.1 asRNA | T cells | Repression |

A deeper examination of CRE-mediated PU.1 regulation in normal development and disease is merited as many important questions remain. For instance, mechanisms for the dynamic switching by the URE between docking on the PU.1 promoter and the PU.1 asRNA promoter during differentiation represent an important gap in the field. More studies are also needed to understand chromatin signatures underlying the bifunctionality of the URE as an enhancer or a silencer in different blood cell lineages. PU.1 CREs other than the URE must also be further characterized for their contributions to chromatin architecture regulation. As multiple chromosomal translocations are present in hematologic malignancies, it is anticipated that multiple protein fusions could alter the URE functions in leukemia. Rapidly evolving single-cell genomic and epigenomic technologies hold promise in addressing these questions. Accordingly, this will broaden our basic understanding of mammalian gene regulation by cis-acting elements, which comprise up to 10% of the human genome [70]. As strategies to target the URE have shown feasibility [55, 68], further progress could yield clinical tools to modulate CRE-mediated gene expression and normalize chromatin architecture, expanding the therapeutic repertoire for various blood diseases.

Manuscript draft and data accurual: EAK, AKB, and BQT; Figures and Tables: EAK, AKB, EO, and BQT; Idea conception: BQT, ANG, and DGT. Critical review and revision: EAK, AKB, ANG, DGT, and BQT. All authors reviewer and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript.

Not applicable.

We thank Barbara Dziegielewska and members of the Trinh lab for assistance and helpful suggestions. Figures were created with BioRender.com.

This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [grant number: 1P01HL131477-6 A1] to DGT, the National Cancer Institute [grant number: NCI K01 CA222707], and the American Cancer Society [grant number: 134088-IRG-19-143-33-IRG] to BQT.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.