1 Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Affiliated People’s Hospital of Jiangsu University, 212001 Zhenjiang, Jiangsu, China

2 Zhenjiang School of Clinical Medicine With Nanjing Medical University, 212001 Zhenjiang, Jiangsu, China

3 Department of Infectious Disease, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, 210029 Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Notch1 signaling regulates innate immune-mediated inflammation in acute liver injury (ALI). However, the precise mechanism by which Notch1 governs macrophage polarization during ALI remains poorly understood.

Wild-type (WT) mice received DAPT (10 mg/kg) prior to acetaminophen (APAP)-induced ALI. In parallel, bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) were pretreated with either the β-catenin inhibitor XAV939 or the activator SKL2001, exposed to DAPT, and then challenged with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Liver injury and inflammation were evaluated by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, quantitative real-time PCR (RT-PCR), and western blotting.

Unexpectedly, DAPT treatment exacerbated APAP-induced liver injury (AILI), resulting in more severe hepatocellular damage and inflammation than in controls. DAPT-treated macrophages exhibited enhanced pro-inflammatory cytokines expression and a shift toward an M1-like phenotype. Mechanistically, the β-catenin/glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β) signaling pathway emerged as a pivotal regulator of macrophage polarization.

Notch1 inhibition unexpectedly worsens AILI by amplifying macrophage-driven pro-inflammatory responses via β-catenin signaling. These findings highlight the Notch1–β-catenin axis as a key regulator of hepatic macrophage function and a potential therapeutic target for sterile liver inflammation.

Keywords

- APAP

- β-catenin

- DAPT

- macrophage

- Notch1

- liver inflammation

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) represents the predominant cause of acute liver failure (ALF) in Western countries [1], with nearly half of cases (approximately 46%) arise from acetaminophen (APAP) overdose in the United States [2, 3]. The hepatotoxicity effects of APAP arise from its metabolite NAPQI (N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine), which exhausts glutathione, impairs mitochondrial function, and triggers DNA injury [4]. The resulting hepatocyte damage provokes a robust sterile inflammatory response, largely orchestrated by hepatic macrophages and neutrophils through recognizing damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which further aggravate liver injury [4].

The evolutionarily conserved Notch signaling pathway is elemental for tissue homeostasis, stem cell maintenance, and regulation of crucial cellular processes such as proliferation, survival, apoptosis, and differentiation [5, 6]. Dysregulation of Notch signaling has been implicated in diverse hepatic pathologies, including fibrosis and acute liver injury, where it influences hepatocyte function and immune cell behavior [7, 8, 9]. Notch1, in particular, has been shown to regulate the innate immune-mediated liver injury induced by APAP or hepatic ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) in our previous [4, 10, 11]. Notably, Notch1 signaling influences macrophage polarization in a context-dependent manner [12]. Pharmacologic or genetic inhibition of Notch1 can attenuate M1-driven fibroblast activation and fibroblast-induced M1 polarization [13], while also affecting M2 differentiation [14]. Nevertheless, the precise mechanisms by which Notch1 governs macrophage polarization during APAP-induced liver injury remain unclear.

Crosstalk between Notch1 and

In this study, we demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition of Notch1 unexpectedly exacerbates APAP-induced liver injury (AILI) by driving macrophages toward a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype via

Wild-type (WT) mice (C57BL/6, male, 8 weeks) were obtained from the Animal Core Facility of Nanjing Medical University (Nanjing, China). Mice were kept in SPF conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Nanjing Medical University (IACUC-2206039) and conducted in accordance with NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

ALI was conducted by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of APAP (400 mg/kg, 1003009, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) [4]. In the treatment group, mice were administered the DAPT (10 mg/kg, D5942, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), the

Blood samples were centrifuged to obtain serum. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were measured using a commercial assay kit (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME, USA) from serum, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Liver samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h, embedded in paraffin, and then sectioned at 5 µm. The slides were stained with Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological evaluation. Macrophage infiltrations were detected by immunohistochemistry using a CD11b monoclonal antibody (1:100, MCA711, Bio-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA) and visualize with the ABC Kit (Vector, PK-7200). CD11b-positive cells were quantified in 10 randomly selected high-power fields (HPFs) by a blinded observer.

Frozen liver sections (5 µm) or cultured cells were fixed in formalin, blocked with 5% BSA, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, including rabbit anti-iNOS (1:100, 13120, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), rabbit anti-CD206 (1:100, 24595, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and mouse anti-CD163 (1:100, sc-58965, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA). Samples were then incubated with Cy™5- or AlexFluor488-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:250, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h and nuclei were counterstaining with DAPI (sc-24941, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA). Images were captured using a LEICA DMI3000B microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and analyzed with ImageJ, version 2.9/1.53t (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Hepatic cell death was detected using the Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay with the Klenow-FragEL DNA Detection Kit (QIA33, EMD Chemicals or MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), following manufacturer’s instructions [15]. Positive cells were quantified in 10 randomly selected HPFs.

Total RNA (2.5 µg) was reverse using the SuperScript™ III Reverse Transcriptase System (18080051, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) [4]. RT-qPCR was performed using the Platinum SYBR Green qPCR Kit (11736059, Invitrogen) under the following conditions: 50 °C for 2 minutes, 95 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 30 seconds. Primer sequences are provided in Table 1.

| Target genes | Forward primers | Reverse primers |

| m | 5′-GTGACGTTGACATCCGTAAAGA-3′ | 5′-GCCGGACTCATCGTACTCC-3′ |

| mTnf- | 5′-ACGGCATGGATCTCAAAGAC-3′ | 5′-AGATAGCAAATCGGCTGACG-3′ |

| mIL-6 | 5′-GCTACCAAACTGGATATAATCAGGA-3′ | 5′-CCAGGTAGCTATGGTACTCCAGAA-3′ |

| mMcp-1 | 5′-TGCTTCTGGGCCTGCTGTTC-3′ | 5′-ACCTGCTGCTGGTGATCCTCT-3′ |

| mArg-1 | 5′-GACACCCATCCTATCACCGC-3′ | 5′-GCGGCTGTGCATCATACAAC-3′ |

| mIL-10 | 5′-GCCAGTACAGCCGGGAAGAC-3′ | 5′-GCCGATGATCTCTCTCAAGTGAT-3′ |

Proteins (30 µg/sample) from liver tissue or cultured cells were separated using 12% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) and probed with antibodies against monoclonal anti-rabbit STAT1 (1:1000, 14994, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), phos (p)-STAT1 (1:1000, 9167, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), STAT6 (1:1000, 5397, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), phos-STAT6 (1:1000, 56554, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), NICD (1:1000, 3608, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA),

BMMs were extracted from the femurs and tibias of WT mice and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, GIBCO, Waltham, MA, USA, 11995-065) containing 10% FBS (GIBCO, FBS-500) and 15% L929-conditioned medium [4]. In certain experiments, BMMs were pre-treated with a

Data are expressed as mean

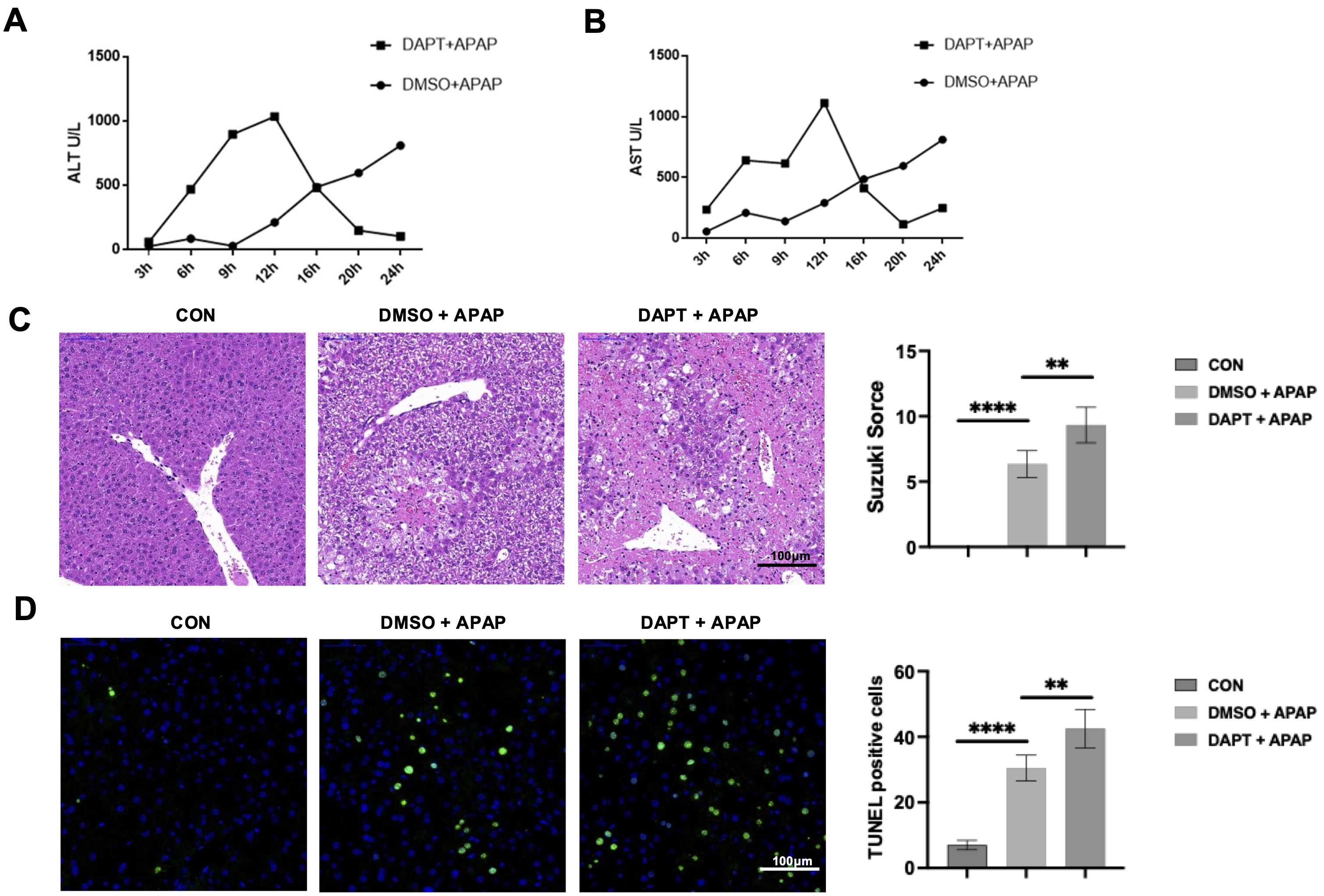

We firstly employed a mouse model of AILI to investigate Notch1-mediated hepatic injury. Mice pretreated with the

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Inhibition of Notch1 signaling exacerbates acetaminophen (APAP)-induced liver injury. Mice received a tail vein injection of the Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or

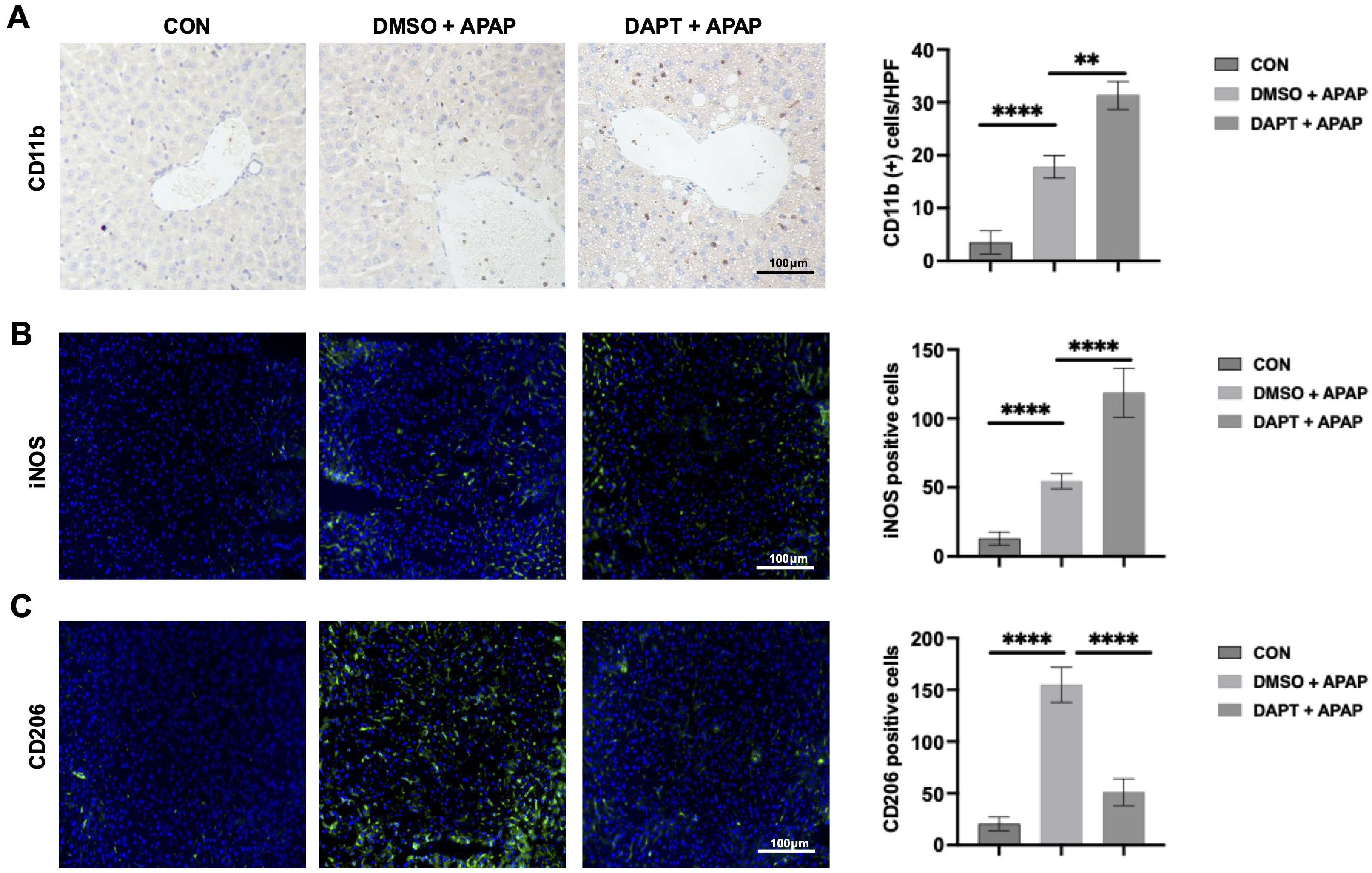

We next evaluated the impact of Notch1 inhibition on macrophage accumulation during AILI. Immunohistochemical staining for CD11b showed marked macrophage infiltration in APAP-injured livers, with DAPT treatment further increasing CD11b+ macrophage accumulation, especially in the portal regions (Fig. 2A). Immunofluorescence further analysis revealed a higher abundance of iNOS⁺ macrophages (M1-like) (Fig. 2B) accompanied by a reduction of CD206⁺ macrophages (M2-like) (Fig. 2C) in the DAPT-treated group relative to controls. This suggests that Notch1 signaling normally restrains macrophage recruitment while favoring M2 polarization during AILI.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Inhibition of Notch1 signaling increases hepatic macrophage infiltration and polarization. (A) Immunohistochemical staining and 1uantification of CD11b+ macrophages in liver tissue 12 hours after APAP-challenged. (n = 6/group). Scale bar, 100 µm. (B) Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS⁺) macrophages (n = 6/group). Scale bar, 100 µm. (C) Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of CD206⁺ macrophages (n = 6/group). Scale bar, 100 µm. **p

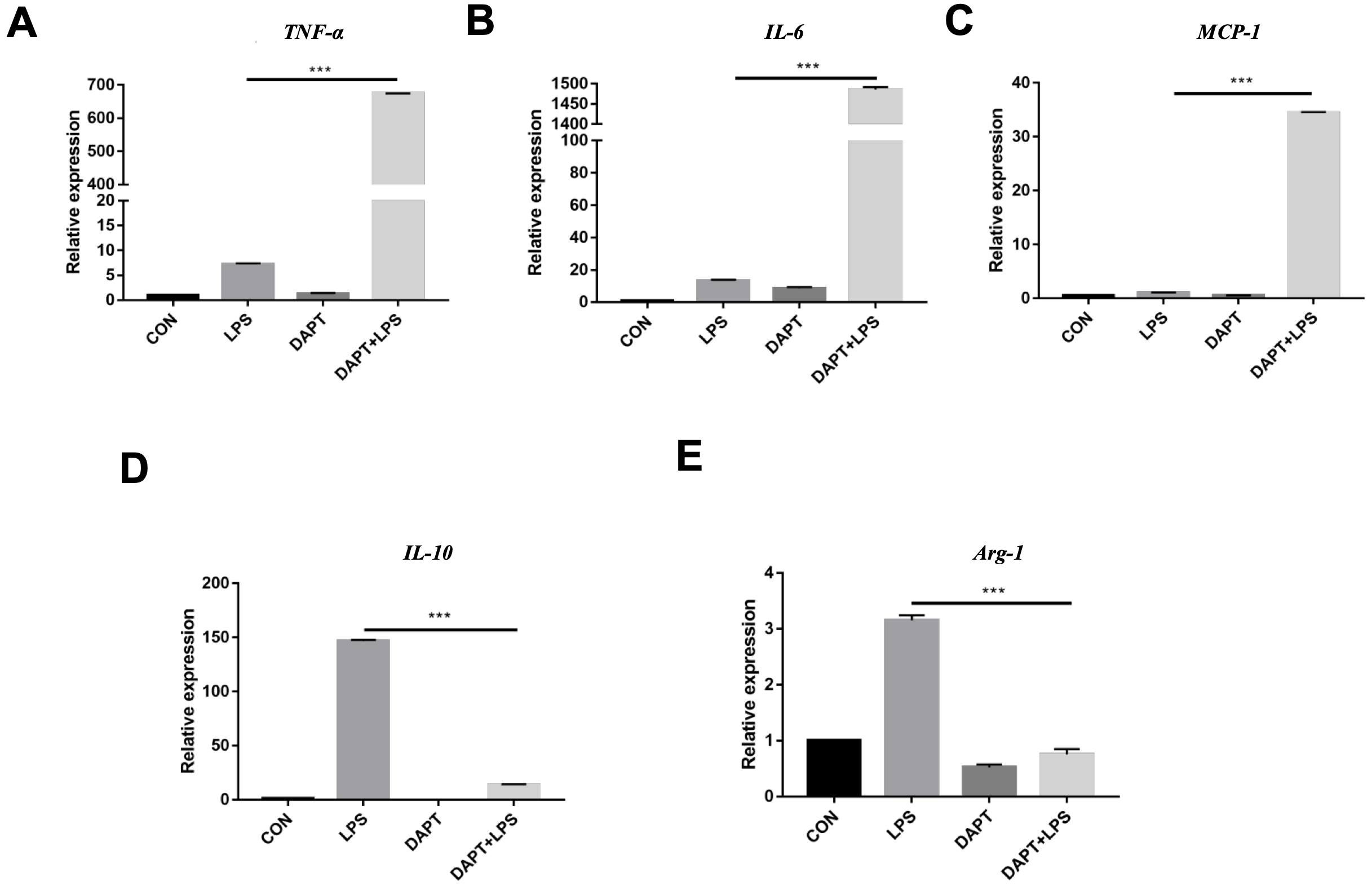

We then used BMMs were challenged with LPS with or without DAPT to assess whether blockade of Notch1 influences macrophage activation. Compared with LPS controls, DAPT-treated BMMs exhibited significantly higher mRNA levels of the pro-inflammatory mediators TNF-

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Inhibition of Notch1 signaling promotes a pro-inflammatory cytokine profile. (A–C) Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis of TNF-

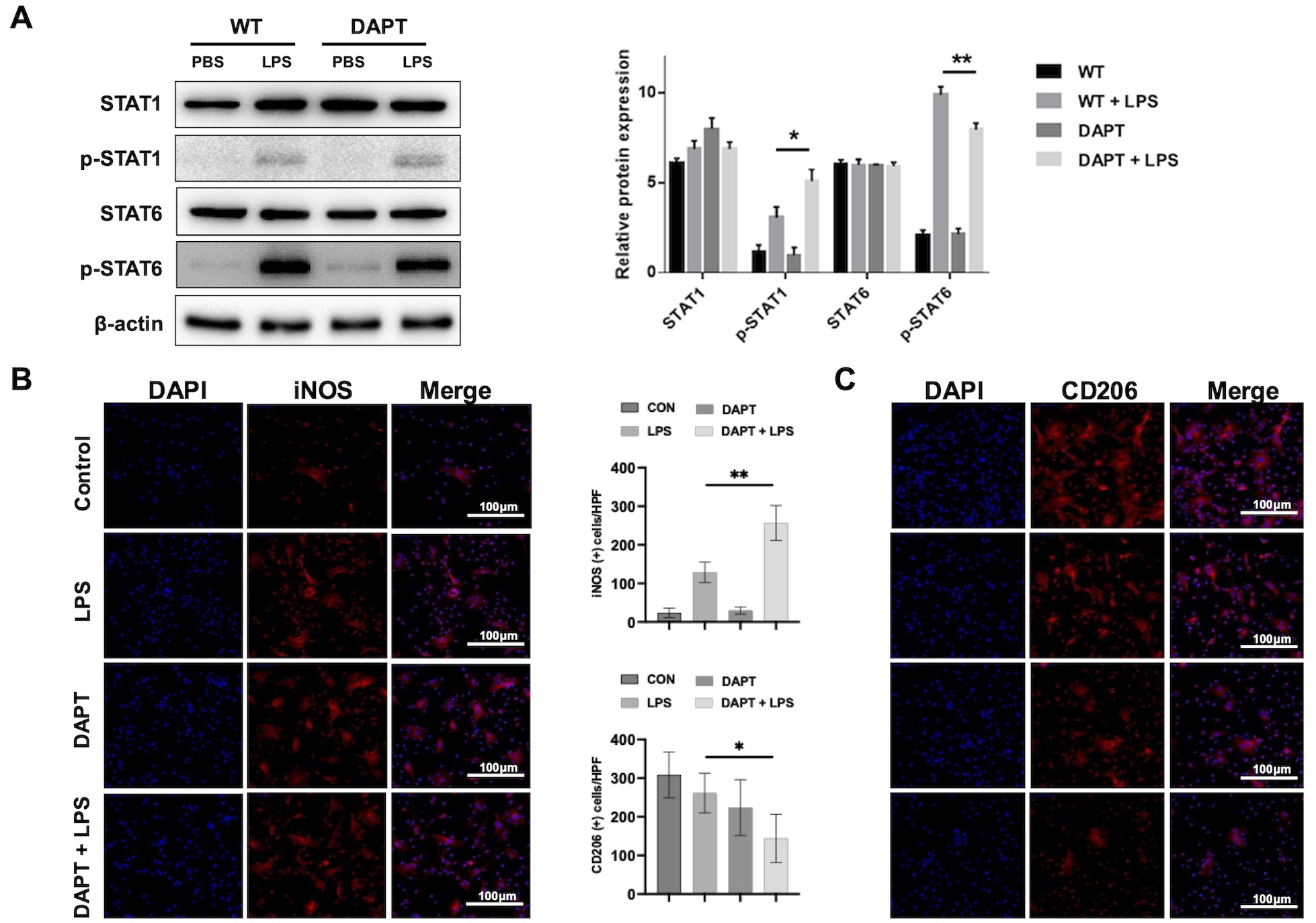

To further explore whether BMMs differentiate into the M1 pro-inflammatory phenotype, we then measured the expression of specific biomarkers associated with M1 and M2 macrophage polarization. Western blot analysis revealed that DAPT treatment increased p-STAT1 (M1-associated) while decreasing p-STAT6 (M2-associated) [20] levels in BMMs after LPS stimulation (Fig. 4A). Immunofluorescence revealed a higher proportion of iNOS+ macrophages (Fig. 4B) and a decrease in CD206+ macrophages (Fig. 4C) in DAPT-treated group. Together, these results suggest that Notch1 promotes M2 polarization while restraining M1 activation.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Notch1 blockade promotes M1 polarization and suppresses M2 polarization. (A) Western blot and densitometric analysis of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1)/phos-STAT1, and STAT6/phos-STAT6 in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-challenged BMMs with or without DAPT precondition. (B) Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of iNOS⁺ macrophages (n = 6/group). Scale bar, 100 µm. (C) Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of CD206⁺ macrophages (n = 6/group). Scale bar, 100 µm. *p

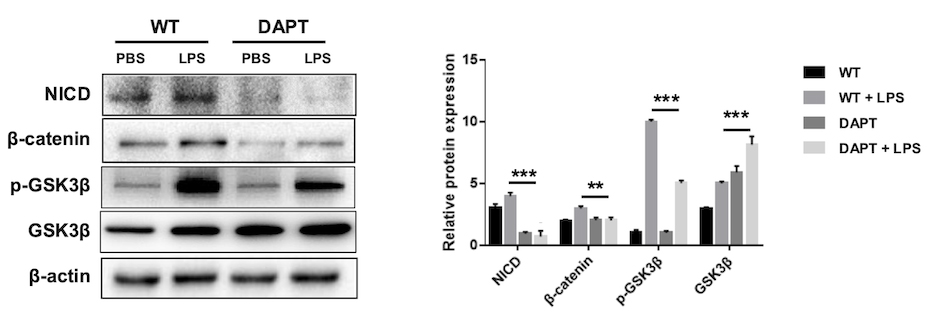

To investigate the underlying mechanism, we examined

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Notch1 inhibition suppresses

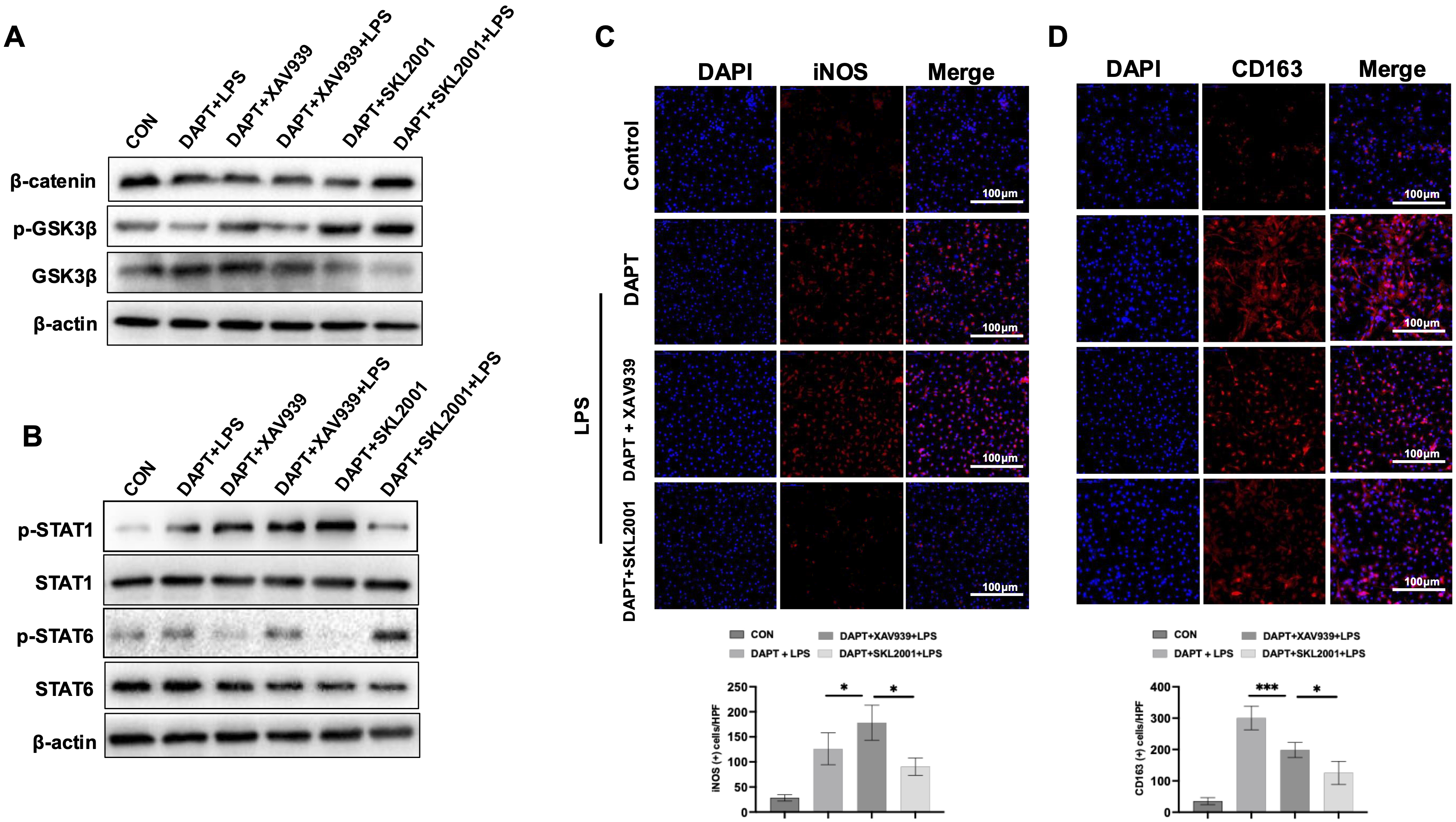

To confirm whether

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. The innate immune response is a critical driver of AILI [2, 4]. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that toxic metabolites of APAP initially induce necrosis and apoptosis of hepatocytes [21, 22], which subsequently activate innate immunity and stimulate macrophages to release pro-inflammatory cytokines. The upregulation of these inflammatory factors further exacerbates liver damage [23]. Given their pivotal role in mediating inflammatory injury, macrophages have been recognized as potential therapeutic targets in DILI. Herein, we identify the Notch1-

Notch signaling is well-established mediator in liver pathology. It is activated in liver fibrosis and is found to be abnormally elevated in patients with fibrotic disease. Inhibiting this pathway can suppress the progression of fibrosis [24, 25]. Our previous study demonstrated that Notch1 ablation exacerbated liver injury, a phenomenon linked to the activation of either NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) [10] or stimulator of interferon genes (STING) signaling [4] in macrophage. Collectively, these findings support a role for Notch1 signaling in controlling macrophage activation during acute hepatic inflammation.

Macrophages exhibit remarkable plasticity, polarizing toward pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory phenotypes, contributing to diverse immune responses [26]. For example, Notch1 deletion has been reported to attenuate both M1-driven fibroblast activation and fibroblast-induced M1 polarization, while also limiting macrophage activation toward the M2 phenotype [13]. Conversely, some studies report that Notch1 inhibition can promote M2 polarization in injured livers [27]. In alcoholic liver disease, myeloid Notch1 knockout prevents macrophage infiltration and leads to M1 phenotype [28]. This suggests that Notch1-mediated macrophage function is highly dependent on the specific stress or disease environment. Nonetheless, whether pharmacologic Notch1 inhibition affects macrophage polarization in AILI has not been thoroughly investigated.

Our results demonstrated a marked increase hepatic macrophages following APAP treatment. Furthermore, with numbers further elevated in the DAPT-treated group. Previous studies have demonstrated that the resident macrophage Kupffer cells (KCs), which originate from specific progenitor cells in the yolk sac during embryonic development. These KCs maintain their population through self-renewal and are not dependent on monocyte-derived macrophages for replenishment [29]. During acute liver injury, activated KCs release inflammatory cytokines that recruit peripheral monocytes to the liver [30]. In our study, CD11b staining confirmed a marked increase in macrophages in injured liver. In the fulminant hepatitis mouse model, there was a significant depletion of KCs in the later stages, but an initial pro-inflammatory M1 polarization of macrophages was evident early on. Following the depletion of KCs, a large influx of peripheral monocytes into the liver was observed. These monocytes initially adopted a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype but transitioned to an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype in the later stages, promoting tissue repair and suppressing inflammation [31]. In the APAP mouse model, both macrophages are mainly distributed in the portal area [32]. In this study, Western blot and immunofluorescence analysis of BMMs treated with DAPT revealed increased M1 markers and decreased M2 markers, indicating that DAPT promotes M1 polarization. Correspondingly, DAPT-treated macrophages express higher levels of pro-inflammatory genes, such as TNF-

The

Undeniably, this study is subject to certain limitations. First, our findings are derived from murine models of APAP-induced liver injury, which may not entirely reflect the complexity of human DILI. Second, while our study focused on the Notch1-

In this study, we demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition of Notch1 in AILI promotes macrophage infiltration, drives toward a M1 phenotype, and exacerbates liver injury. This effect occurs, at least in part, due to suppression of

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Material. All data is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

TY, PS and JL conceived and designed the study. PS, JJD, YYS and XW performed the animal experiments. PS, JJD, JYZ, and JLZ performed the experiments in vitro. TY and LFJ analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. JL and LFJ modified the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Nanjing Medical University (IACUC-2206039) and conducted in accordance with NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82400678), the Scientific research project of Health Commission of Jiangsu, China (No. M2024034), LiGan Research Funds iGandan (No. F-1082025-LG024).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL43853.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.