1 Endocrinology and Nutrition Department, University and Politecnic Hospital La Fe (Valencia), 46026 Valencia, Spain

2 Joint Research Unit on Endocrinology, Nutrition and Clinical Dietetics, Health Research Institute La Fe, 46026 Valencia, Spain

3 Pediatric Endocrinology Unit, University and Politecnic Hospital La Fe (Valencia), 46026 Valencia, Spain

4 Nuclear Medicine Department, University and Politecnic Hospital La Fe (Valencia), 46026 Valencia, Spain

5 Medical Oncology Department, University and Politecnic Hospital La Fe (Valencia), 46026 Valencia, Spain

6 Department of Medicine, University of Valencia, 46010 Valencia, Spain

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Inhibitors of DNA-binding (Id) proteins constitute a family of repressor factors that modulate a multitude of cellular processes and have been linked to tumor aggressiveness, resistance to chemotherapy, angiogenesis, and worse prognosis in numerous malignancies. This review explores the role of Id proteins in the pathogenesis of neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs). The findings revealed that this family of proteins shows significant overexpression in tumors such as small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), neuroendocrine prostate carcinoma (NEPC), and medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC), although the role of epigenetics in regulating Id proteins within NENs remains poorly understood, with most evidence limited to NEPC. These results underscore the potential of Id proteins not only as diagnostic biomarkers and promising therapeutic targets for the management of NENs, but also highlight the need for further research to better understand their epigenetic regulation and broader role in these tumors.

Keywords

- Id

- Id protein

- cancer

- neuroendocrine neoplasm

- epigenetics

Inhibitors of DNA-binding (Id) proteins represent a family of crucial transcriptional regulators involved in numerous biological processes [1]. These proteins, characterized by their ability to interfere with the binding of specific transcription factors to DNA, play a key role in cell cycle regulation, differentiation, and apoptosis.

Among the diverse cancer types where Id proteins are implicated, neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) stand out as a heterogeneous group of malignancies originating in the diffuse endocrine cell system. Gastroenteropancreatic NENs (GEP-NENs) have the highest incidence, followed by bronchopulmonary neoplasms (BP-NENs), with approximately 3.56 new cases per 100,000 and 1.49/100,000 respectively [2]. These tumors display considerable heterogeneity in their biological behavior, ranging from well-differentiated, slow-growing forms to poorly differentiated, aggressive variants [3]. This diversity is driven, in part, by complex molecular mechanisms, including genetic and epigenetic alterations, which influence tumor progression, therapeutic resistance, and clinical outcomes.

Despite advances in the understanding of NENs, the involvement of Id proteins in their development remains poorly characterized. Given the established significance of Id proteins in other cancers, it is critical to investigate their contribution to the molecular mechanisms underlying NENs, including the potential role of epigenetic regulation, as such an exploration could reveal novel opportunities for the development of targeted diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. This research focuses on evaluating the role of Id proteins in the development of NENs, providing a basis for future explorations to better understand these molecular interactions and their clinical implications.

Inhibitors of DNA binding proteins represent a family of small size proteins (13–18 kDa) characterized by the presence of highly preserved helix-loop-helix (HLH) domain and their implication in gene expression by interacting with several proteins and transcription factors [4]. This peculiar structure is the key for understanding their main functions and their involvement in various cell growth and differentiation pathways.

Id proteins are not the only ones within the HLH superfamily. Among the seven subtypes described (I–VII), Id proteins belong to class V, which are characterized by lacking basic amino acids [5]. This leads to the impossibility of binding directly to specific regions of the DNA. Therefore, their binding targets are mainly other HLH proteins, especially class I–IV, which do have basic amino acids (bHLH) and can bind directly to DNA. Within the Id proteins family, four subtypes (Id1-4) are currently distinguished. Although they have a high structural homology, they share different and sometimes even antagonistic functions. In fact, Id1-3 are usually recognized as tumor promoters, whereas Id4 appears to be tumor suppressor, being this, due probably to the presence of polyalanine segments in the N-terminal region of Id4 [6].

Id proteins, which were discovered in 1990, are encoded by four different genes located on separated chromosomes [7, 8]. From among the multiple factors that modulate their expression the role of the members of the transforming growth factor-

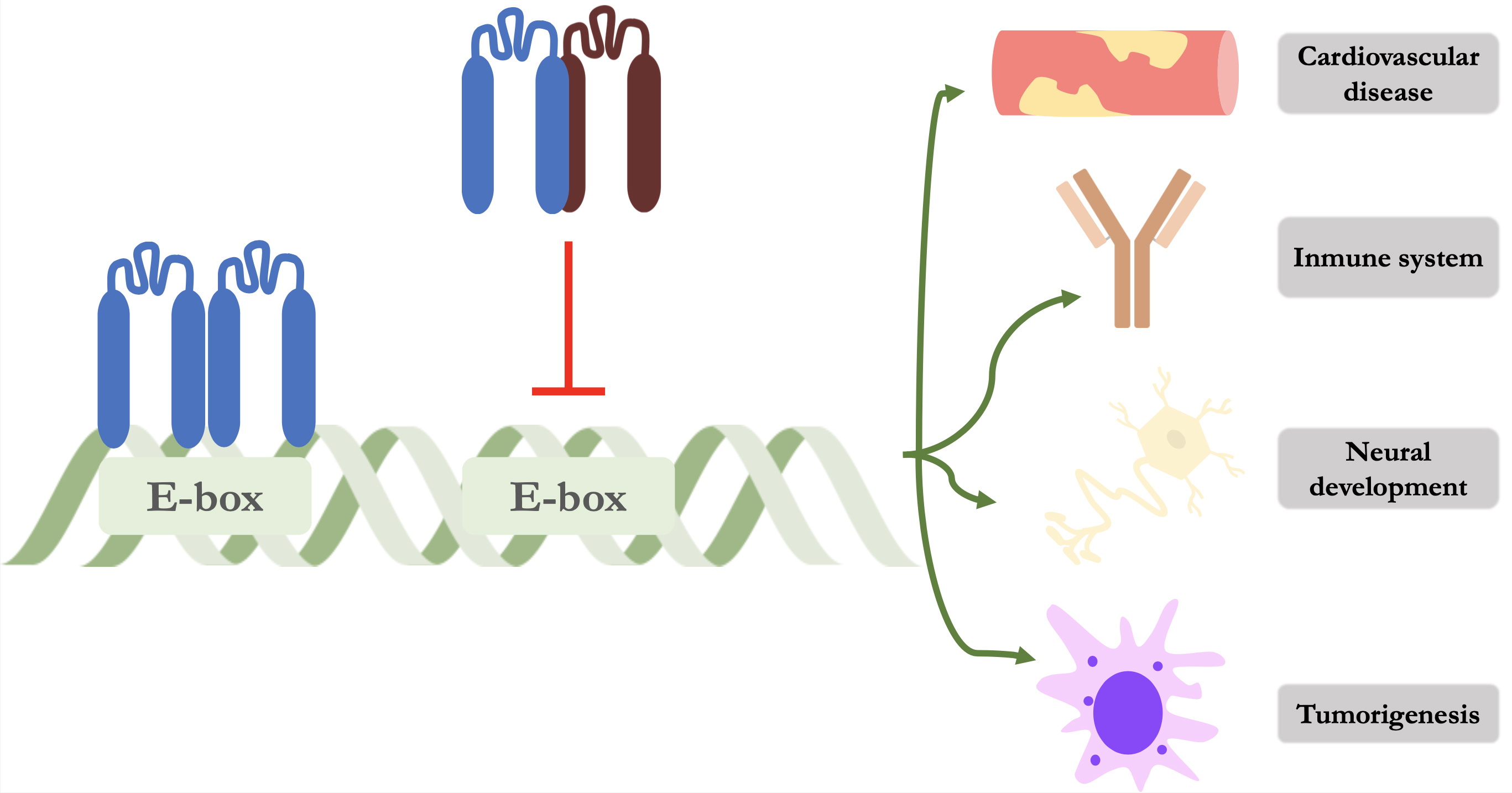

Id proteins perform their function of modulating gene expression through binding to other proteins, as they cannot bind to DNA due to the absence of a basic region adjacent to the HLH motif (Fig. 1). The main targets for binding are HLH proteins, specifically class I and II proteins [15]. E proteins (mainly E2A, HeLa E-Box binding factor (HEB) and E2-2) are representative of class I HLHs and the formation of these heterodimers prevent their physiological binding to specific recognition sites known as E-box and N-box [16]. By the formation of this heterodimer, Id proteins prevent binding and therefore repress gene transcription that regulate various cellular processes such as angiogenesis, neurogenesis, myelopoiesis, regulation of the immune system, cell growth and tumorigenesis. Class II of HLH proteins are mainly composed of myogenic (MyoD) and neural (NeuroD/Beta2) regulatory factors [17].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the mechanism of action of Id proteins. The left-hand side shows an E protein forming a homodimer and binding to its promoter region on DNA. On the right, an Id protein (dark red) is shown forming a heterodimer and preventing its binding and thus repressing gene transcription of various cellular processes. Id, inhibitor of DNA binding protein.

On the other hand, the Id family not only establishes its functions by binding to HLH proteins, but also has the capacity to interact with different proteins and transcription factors [18]. A key target is the retinoblastoma protein (Rb), the inhibition of which mediates much of the effects on cell proliferation [19, 20]. Other examples include paired-box (PAX) transcription factors, caveolin-1 transmembrane protein, Von-Hippel Lindau (VHL) syndrome-associated protein or the estrogen receptor beta-1 [21, 22, 23, 24].

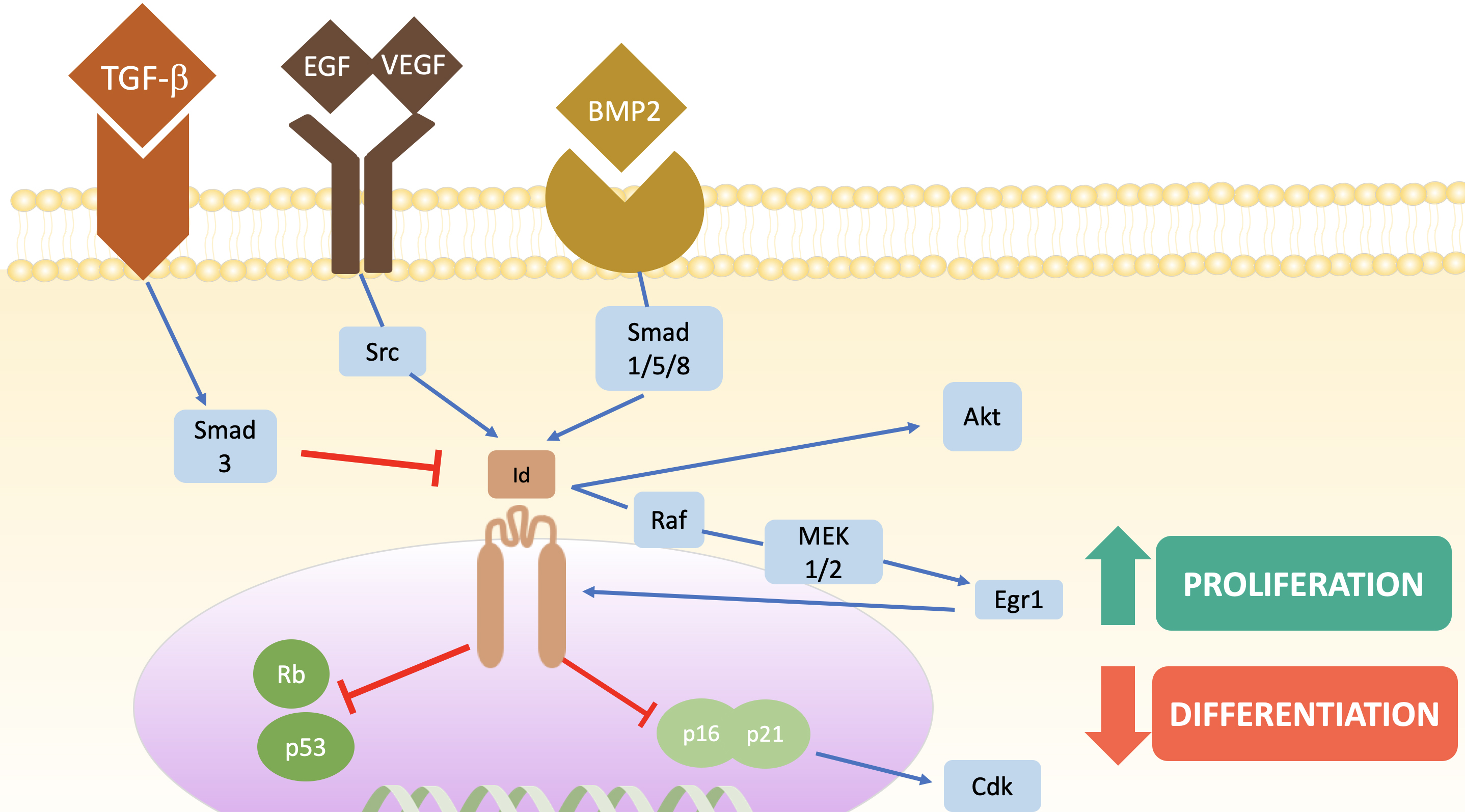

As Id proteins have multitude of interactions, the intracellular signaling mechanisms are complex (Fig. 2). Different stimuli at transmembrane receptors lead to a different signaling cascades. Binding of BMP2 or growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or epidermal growth factor (EGF) leads to an increase in Id1 transcription via Smad1/5/8 and Src proto-oncogene (Src) tyrosine kinase respectively while TGB-

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Regulation of Id proteins and their main stimulation pathways. Blue arrows mean activation while red arrows represent metabolic pathway inhibition. Note that Egr1 establishes a positive feedback system, as it ultimately favours the transcription of Id proteins. TGF-

Within Id proteins, Id1 is mainly involved in the processes of endothelization and vascular proliferation due to its inhibition of the E2-2 protein, which is responsible for inhibiting endothelial cell proliferation through a decrease in the concentration of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) [29, 30, 31]. It has also been linked to the development of atherosclerotic plaque and has been suggested as a possible therapeutic target [32, 33]. Furthermore, alterations in Id proteins can lead to severe cardiac abnormalities, such as valvular defects in double/triple knockout mice or arrhythmias, both ventricular and atrial, in those with loss of Id2 function [34, 35, 36, 37].

The relationship between the immune response and the Id family has also been extensively studied. While Sanjurjo et al. [38] showed the role of Id3 in M2 macrophague polarization, Deng et al. [39] demonstrated that Id3 promotes antitumour response by increasing phagocytosis of Kupfer cells by preventing the binding of transcription factors such as E2A and ELK to the signal regulatory protein-alpha locus (SIRP

The Id family of proteins has been closely linked to neuronal development. Among the four members, Id2 and Id4 have been most closely linked to nervous system physiology. Indeed, they are key in the processes of oligodendrogenesis, proliferation and differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) [45, 46]. These effects of Id2 are mediated through inactivation of Rb or its interaction with oligodendrocyte lineage transcription factor (OLIG). Id2 is in turn regulated by multiple signals, such as BMP2 or the Wnt/catenin pathway [47]. It has even been hypothesized that targeting their signaling could be of use in white matter damage as it has been shown in animal models to accelerate axonal regeneration and promote neuromuscular reinnervation [48, 49]. Although these are the main processes in which the intervention of the Id proteins family has been studied, various aspects such as reproductive function, ocular disease, adipogenesis or disruption of the endocrine system are also the subject of study [50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56].

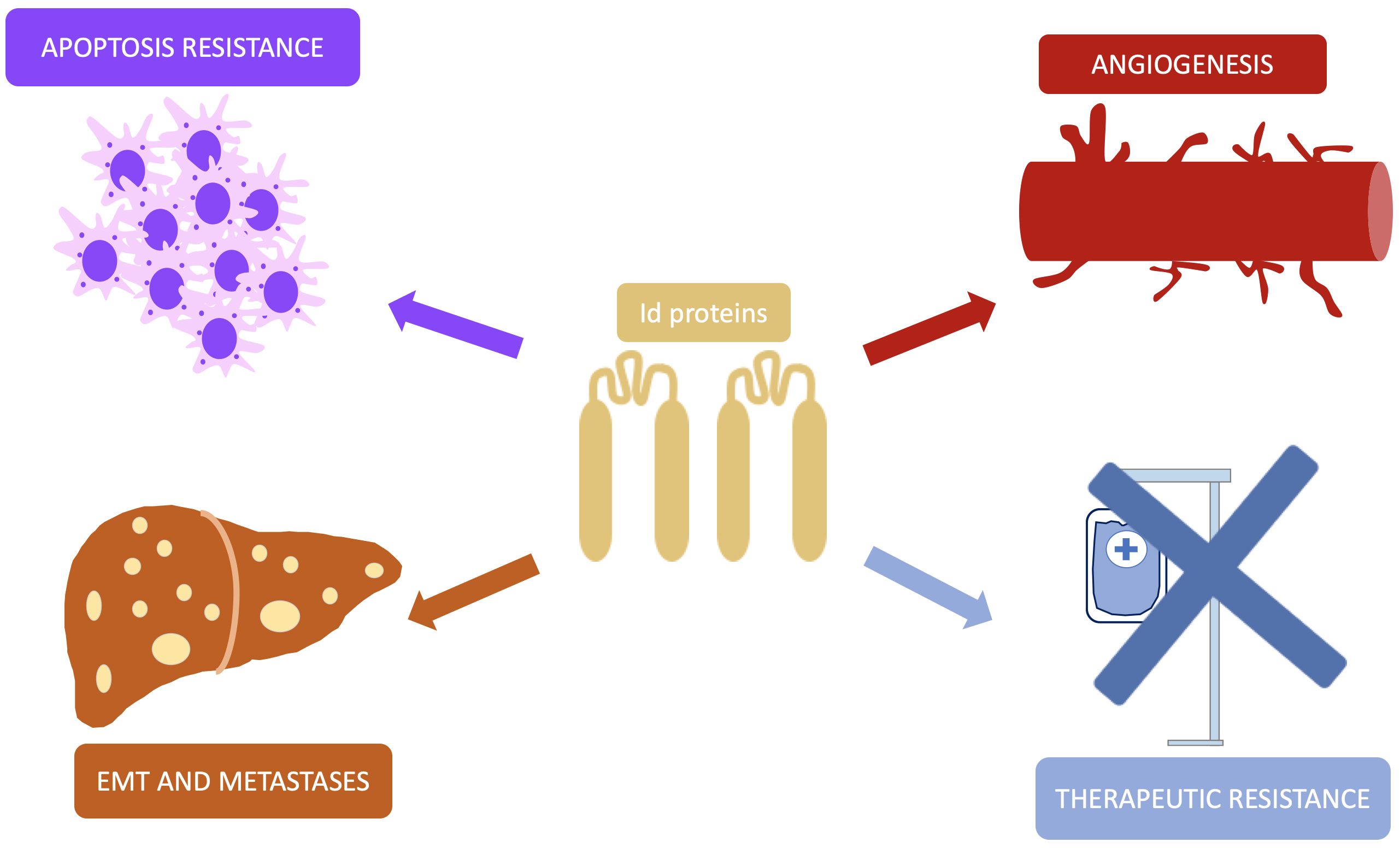

Although they do not fit the strict definition of oncogene, Id proteins are intimately involved in cell proliferation and differentiation, which therefore plays pivotal role in the tumorigenesis and development of malignant neoplasms. As previously discussed, loss of function of suppressors such as p53 or Rb allows cells to bypass their inhibitory signal, leave the quiescent state and initiate a continuous proliferative process. Nevertheless, not only are Id proteins related to the insensitivity to growth inhibitory signals but also this family of transcription factors are involved in more neoplastic processes (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Pathways of Id proteins involvement in carcinogenesis. This simplified representation shows the different pathways by which Id promotes the development and progression of malignant neoplasms. Id, inhibitor of DNA-binding; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

Angiogenesis is another mainstay on which malignant tumors are built, being a key step in metastatic disease. Within this process, VEGF emerges as the most relevant molecule, and its regulation is closely linked to the increase in hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1

Id1 also actively participates in the mobilization and recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells from the bone marrow, an essential step for tumor neovascularization [61]. Moreover, these proteins not only promote the formation of new vessels, but also repress angiogenesis inhibitory factors, such as thrombospondin, promoting a vascular microenvironment that favors tumor growth [62]. On the other hand, Id1 potentiates the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukine-8 (IL-8) and chemokine growth-regulated protein alpha (GRO-

Resistance to conventional treatments is a major problem, as different types of cancer have developed strategies to counteract their cytotoxic effects. Among the cell subtypes within a neoplasm, tumor cells with stem-cell characteristics are a major focus of resistance because of their self-renewal skills and are favoured by the presence of Id proteins together with signal transducer and activator of transcription type 3 (STAT3) [65]. For example, Id1 together with c-Jun proto-oncogene (c-Jun) has been linked to resistance to etoposide-induced DNA damage in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma while in prostate carcinoma it is associated with resistance to taxane-induced damage due to Akt overexpression [24, 66]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, Id1 activates the p16/IL6 axis, favoring resistance to sorafenib, and stimulates the pentose phosphate pathway, promoting chemoresistance to oxaliplatin [67, 68]. What is more, Id1 overexpression induces resistance to 5-Fluorouracil through activation of E2F1-dependent thymidylate synthase in colorectal cancer, whereas its inhibition restores sensitivity to treatment. These findings underscore the multifaceted role of Id1 in the regulation of therapeutic resistance [69].

Avoidance of pro-apoptotic signals is one of the significant mechanisms for tumor cell survival and the Id family has also been involved at this level [70]. In fact, suppression of apoptosis has been demonstrated in small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) and prostate adenocarcinoma being the latter mediated through an increased nuclear factor kappa

Multiple alterations are necessary for tissue invasion and the development of metastasis, such as overcoming cellular adhesion, eliminating the extracellular matrix and being able to settle in a distant organ. This process is known as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and involves several molecules including Id1 and E47 [76, 77, 78]. This fact has clinical implications, such as the Id1-induced resistance to osimertinib in non-SCLC through an increase in EMT [79]. In addition, BMP4 and T-box transcription factor 3 (TBX3) are responsible for the increase in Id1 overexpression, EMT and metastatic disease in both gastric and cervical cancer respectively [80, 81]. Id1 has also been identified as a critical regulator of breast cancer stem cell-like properties and metastatic colonization. Under the control of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-

As previously described, Id proteins play multiple roles in tumor development, acting as key regulators in various biological processes. These proteins are part of complex signaling cascades, interacting with multiple molecular pathways that contribute to cancer progression. Moreover, their activity is tightly regulated by epigenetic mechanisms, while they themselves influence and are modulated by these processes, establishing a bidirectional relationship that highlights their importance in the regulation of the tumor environment.

It has been shown that Id1 potentiates the E3 ligase activity of RING1b through Mel-18 and Bmi-1 proteins, which represent epigenetic repressor proteins that are part of Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1), establishing a connection between Id1 and Polycomb-mediated epigenetic regulation [83]. It has also been described that inhibition of Id1 promoter methylation by demethylating agents, such as 5-AZA-2′-deoxycytidine, can increase its expression and, consequently, improve sensitivity to treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma [84]. Along the same lines, the BMP9-ID1 pathway has been implicated in the reduction of N6-methyladenosine methylation in CyclinD1, favoring cell proliferation in this type of cancer [85]. On the other hand, Id4 presents an apparently contradictory role: in glioblastoma, its epigenetic silencing seems to be associated with a better prognosis due to the inhibition of angiogenesis whereas its methylation pattern positions it as a potential tumor suppressor in leukemia [86, 87].

Recent research has revealed significant interactions between Id proteins and histone modifications in various oncological contexts. Tamari et al. [88] demonstrated that polyamine efflux suppresses the activity of histone lysine demethylases, resulting in an accumulation of repressor epigenetic marks and increased Id1 expression in cancer stem cells. In addition, Zhang et al. [89] identified that targeted inhibition of lysine-specific demethylase 6 (KDM6) eradicates tumor-initiating cells in colorectal cancer through enhancer reprogramming, involving key genes such as Id1. On the other hand, it has also been observed that the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A induces Id1 expression and promotes apoptosis in human acute myeloid leukemic cells, indicating that histone acetylation can activate Id1 expression and trigger cell death in certain tumor contexts [90].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as important regulators of Id proteins, modulating their expression in different types of cancer and affecting both progression and therapeutic response. In colorrectal cancer, miRNA-885-3p blocks BMP/Smad/Id1 signaling by upregulating BMP receptor type 1A (BMPR1A), thereby suppressing angiogenesis and slowing tumor growth, while the miRNA-371~373 cluster represses metastatic initiation by inhibiting the TGF receptor type 2 (TGFBR2)/Id1 axis, highlighting their role as tumor suppressors [91, 92]. In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, circ-ATIC acts by sequestering miRNA-326, allowing Id1 overexpression and favoring tumor progression [93]. On the other hand, in papillary thyroid carcinoma, the long non-coding RNA NEAT1 captures miRNA-524-5p, reducing its regulatory capacity over Id1 and promoting tumor development [94]. The influence of miRNAs has also been related to EMT, such as the inhibitory influence of miRNA-29b in ovarian carcinoma and of miRNA-381 in lung cancer, resulting in both cases in reduced cell migration and invasiveness when these molecules were applied [95, 96]. Finally, in the context of hematological malignancies, downregulation of miRNA-29b and subsequent overexpression of Id1 have been found to be involved in decitabine resistance, suggesting a direct connection between this pathway and therapeutic resistance [97]. These findings underscore the complexity of the interaction between miRNAs and Id proteins, highlighting their relevance in the regulation of tumor progression and their potential as therapeutic targets.

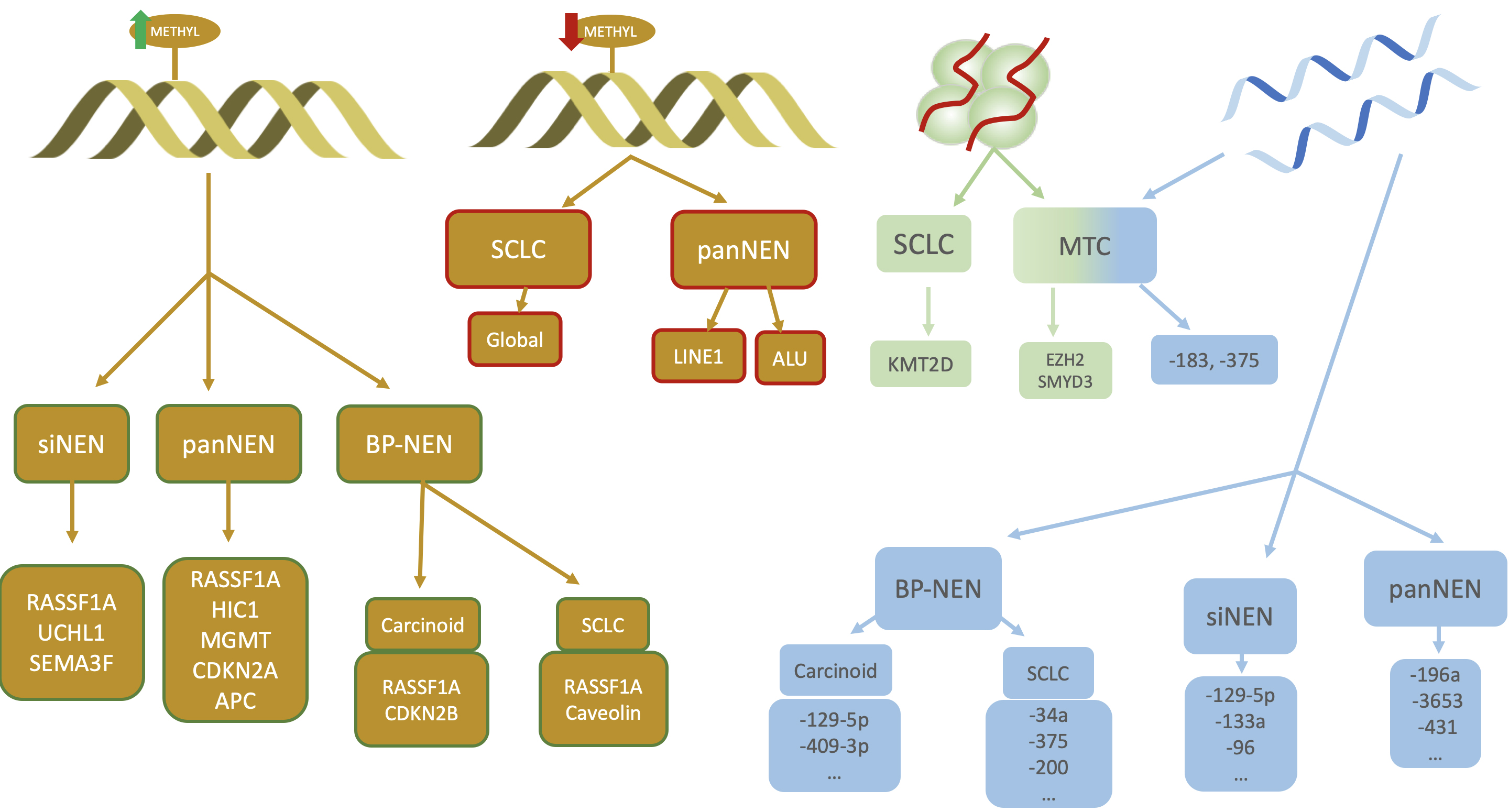

Most cases of NENs occur sporadically but it is estimated that around 5% may occur in the context of a germline genetic mutation and are part of familial predisposing syndromes such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), type 4 (MEN4), Von-Hippel-Lindau, Tuberous Sclerosis or Neurofibromatosis type 1 syndrome [98, 99, 100, 101]. On the other hand, it is now widely recognised that epigenetic mechanisms are fundamental in the regulation of gene expression and the development of neoplasms [102]. Of course, NENs are no exception to this axiom and several regulatory processes at this level can be identified, which vary significantly depending on the location of the primary tumor (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Different epigenetic mechanisms involved in NENs. From left to right: hypermethylation, hypomethylation, histone modifications and miRNAs. Primary tumour and genes involved in hypermethylation are shown in yellow squares with green lines while those related to hypomethylation have red lines. Note the importance of RASSF1A in all NENs regardless of their location. siNEN, small intestine neuroendocrine neoplasm; panNEN, pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm; BP-NEN, bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumour; SCLC, small cell lung carcinoma; MTC, medullary thyroid carcinoma; RASSF1A, Ras association domain family member 1A; SEMA3F, semaphorin 3; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; CDKN2A, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A; MGMT, O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase; LINE1, long interspersed element 1; ALU, Arthrobacter luteus; KMT2D, lysine methyltransferase 2D; CDKN2B, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B; METHYL, methylation; EZH2, enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit; SMYD3, SET and MYND domain containing 3; UCHL1, ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1; HIC1, HIC ZBTB transcriptional repressor 1.

In small intestine NENs (siNENs), higher hypermethylation of Ras association domain family member 1A (RASSF1A) promoter has been identified in metastases compared to the primary tumour, conferring a worse prognosis [103]. This finding is also present in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (panNENs), where the degree of hypermethylation is even more pronounced and potentially more significant [104]. In addition, lower levels of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL1), which acts as a p53 stabilizer, were observed in metastatic siNENs due to a hypermethylation in its promoter [105]. A relationship was also discovered between lower levels of semaphorin 3 (SEMA3F), methylation of its promoter, increased proliferation and tumour stage [106]. It seems that semaphoring 3 is somehow linked to the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and its downregulation is associated with hypermethylation of its promoter gene SEMA3F.

Regarding panNENs, different mechanisms are described in the literature such as the aforementioned hypermethylation and downregulated expression of RASSF1A (up to 80% of panNENs), which is facilitated by death domain-associated protein (DAXX) and is related to apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by its interaction with a broad spectrum of proteins like including rat sarcoma virus (Ras) or c-Jun [107, 108, 109, 110]. Another that appears to down-regulate the cell cycle is Hypermethylated in cancer 1 (HIC1) protein, which is frequently repressed because of its frequent (93%) hypermethylation in panNENs [111]. Further examples of tumour suppressors with lower activity in these neoplasms are adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), with findings of hypermethylation in 20–48%, being linked the latter to metastatic disease and worse prognosis [104, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115]. Other physiological processes in which increased hypermethylation can be found are DNA damage repair by the enzyme O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), extracellular matrix degradation by metalloproteinases or angiogenesis [116, 117, 118, 119].

In relation to lung carcinoids, there is no large detailed study of the role of DNA methylation [120]. Although some alterations have been reported in the methylation profile, few have been confirmed. Among the identified alterations, RASSF1A appears to be the promoter with the highest frequency of methylation whereas CDKN2B promoter appeared methylated in 15% of cases [121, 122]. Although lower expression of MEN1 gene was associated to poorer prognosis in carcinoids, it seems that its hypermethylation was not the underlying mechanism [123]. With regard to small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), selective hypermethylations of RASSF1A and caveolin-1 are present in up to 60% of cases [124, 125]. Another protein whose function is altered due to hypermethylation is enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit (EZH2), a chromatin modifier that is involved in smoke damage mechanisms [126, 127].

Although less frequent, DNA hypomethylation also plays a role in NENs development. Indeed, hypomethylation in long interspersed element 1 (LINE1) and Arthrobacter luteus (ALU) homolog genes, confer a lower survival and a higher tumour stage in panNENs [117, 128]. Furthermore, global hypomethylation has been described as a characteristic finding of SCLC [124, 125].

Histones play a crucial role in gene expression by regulating chromatin structure and accessibility, thus influencing transcriptional activity [129]. In this regard, it is essential to highlight the lysine methyltransferase 2D gene (KMT2D), responsible for regulating the methylation of histone 3 lysine 4 and CREB-binding protein (CREBBP), whose inactivation is associated with increased tumour growth in SCLC [130, 131]. In addition, overexpression of histone methyltransferases EZH2 and SET and MYND domain containing 3 (SMYD3) has been described in metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) [132].

The role of miRNAs is fundamental in epigenetics, as they direct gene silencing by RNA interference, influencing chromatin modifications and maintaining genome stability [133]. In relation to siNENs, differential expression in miRNA between primary tumours and metastasic disease (for example, miRNA-129-5-p, -133a, -96, -183 or -204) has been described, but no other clinical implications are known for the moment [134]. Regarding miRNAs, a relationship between miRNA-196a and the mitotic index, Ki-67, lower disease-free survival and worse prognosis has been found, as well as between miRNA-3653 and the risk of metastasis, probably mediated by the interaction with alpha-thalassemia mental retardation X-linked (ATRX) protein [135, 136]. In addition, miRNA-431 is also associated with metastasis, and appears to act through the degradation of disabled homolog 2-interacting protein (DAB2IP), inducing activation of the Ras/Erk pathway [137].

There has also been found that miRNA-129-5p, -409-3p, -409-5p, -185 and -497 are overexpressed in typical carcinoids compared to atypical neoplasm [138]. In reference to SCLC, the role of miR-34a as a tumour suppressor could be highlighted and its absence carries a worse prognosis [139]. In addition, miRNA-375 and miRNA-200 (includes miR-200a, miR-200b and miR-200c), are related to metastatic disease and chemotherapy resistance respectively [140, 141].

Overexpression of miRNA-183 and miRNA-375 has been observed in sporadic cases of MTC compared to hereditary cases and is associated with a more aggressive behavior. Therefore, miRNA-375 may be associated with tumour stage, calcitonin levels and disease progression [142].

Since Id proteins are an additional pathway in the vast compendium of processes involved in the development of carcinogenesis, it was decided to investigate their role in NENs development. Notably, evidence on the main epigenetic mechanisms involving Id proteins in NENs is particularly scarce, with the knowledge largely restricted to neuroendocrine prostate carcinoma (NEPC). In terms of molecular pathways and signaling mechanisms (excluding epigenetics), evidence on the role of Id proteins in NENs is notably limited for gastroenteropancreatic (GEP)-NENs. Although the gastroenteropancreatic site is the most frequent location of NENs, there is a paucity of research exploring the influence that Id proteins may have in such cases. Indeed, the only published information on GEP-NENs comes from a single article related to panNENs [143]. Overall, most of the literature discussing the molecular pathways involving Id proteins in NENs focuses on BP-NENs, MTC and NEPC.

GEP-NENs are governed by a specific anatomopathological classification, where tumour grade is an important prognostic factor [144]. Within G3 tumours, well-differentiated or poorly differentiated tumours, also known as neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC), can be distinguished with differences in management and survival [144, 145]. In relation to pan-NENs, such is the difference that it is hypothesized whether there are differences in the cell lineage of origin, with NECs starting from an undifferentiated primitive stem cell and without clear neuroendocrine differentiation [146]. By studying a mouse model of islet cell carcinoma, Hunter et al. [143] discovered a tumour subtype with absent beta-cell marker expression and high mitotic grade that they called poorly differentiated invasive carcinoma (PDIC) and showed a high similarity to poorly differentiated human panNEN. In their work, they found that although both PDIC and well-differentiated insulinoma expressed neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin, only PDIC cells had a high staining intensity for Id1, showing the latter positivity for beta cell markers such as insulin or MafA. Therefore, when considering the similarity between PDIC and poorly differentiated panNENs, it could be intuited that Id1 is also highly expressed in the latter, although the reality is that neither histological nor molecular studies are available for panNENs.

Unlike GEP-NENs, the involvement of the Id family has been studied in BP-NENs in several studies. Increased expression of Id1, Id2 and Id3 was found in SCLC cell lines while an increased expression of all four subtypes in human tumour samples was detected [147]. Their cellular location showed significant differences, as a higher nuclear positivity of Id3 and Id4 was detected whereas the distribution of Id1 and Id2 resulted mainly cytoplasmic. In fact, the cytoplasmic expression of Id2 was positively correlated with patient survival, with a 3-month survival when Id2 was weakly expressed compared to 10 months when Id2 expression was strong. Although it may be contradictory, it is hypothesized that a higher cytoplasmic level translates into a leakage of Id2 from the nucleus and therefore less availability of this protein to inhibit tumour suppressors. In relation to other hystological types, Zhang et al. [148] demonstrated that SCLC shows an upregulation of Id2 and Id4, whereas lung squamous cell carcinoma exhibits lower Id2 expression. What is more, the study of Id2 target genes led to a second conclusion: Id2 plays different roles depending on the tumour lineage. Such is the case that in SCLC up-regulates genes involved in mitochondrial function and ATP production, whereas in squamous cell carcinoma Id2 stimulates T cell activity and leukocyte chemotaxis. These findings seem to explain the high growth and proliferation rate of SCLC as well as the ability to evade the immune response in the latter. The biological relevance of increased expression of Id family members in SCLC is that these cells show an increased proliferative state reminiscent of stem-cell like. Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) appears to be responsible for this, as it favours the BMP2-Smad1/5/8-Id1 cellular pathway through its ability to inhibit neuroblastoma suppressor of tumorigenicity 1 (NBL1), whose function is to antagonize the TGF-

Thyroid cancer is the most frequent endocrine neoplasm and Id proteins inhibitors have been studied in this type of tumour [151, 152]. However, most of the evidence comes from differentiated thyroid cancer. An upregulation of Id1 in malignant versus benign thyroid pathology has been shown and anaplastic carcinoma showed the highest Id1 expression from among them [153]. In papillary thyroid carcinoma, strong immunostaining of Id1 was detected but no correlation with tumor size, lymph node metastasis or tumor stage stage was found [154]. In addition, Id2 has recently been shown to play an influential role in proliferative capacity, stemness, EMT and metastasis development. These effects are presumed to be mediated by the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway [155]. In relation to tumour lineage of neuroendocrine origin, Kebebew et al. [156] found moderate-to-high immunostaining in patients with MTC in sporadic, familial MTC or MEN2A associated disease compared to normal tissue, which showed faint-to-absent intensity (p = 0.002). Additionally, they also characterized its gene expression in human cell cultures, finding a fourfold higher expression of the Id1 RNA transcript when cultured with growth factors, while lower gene expression was identified when inoculated with a redifferentiating agent.

Although an uncommon NEN, mechanisms involving the Id protein family have been described in NEPC. It is a rare entity, with an incidence of 35 per 10,000 per year and accounts for 1–2% of malignant tumours of the prostate gland [157, 158]. However, there is increasing interest in this neoplasm because of its different prognostic and treatment behavior compared to prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) [159, 160]. The origin of this neoplasm is not completely understood. Initially, it was thought that NEPC arises from prostatic neuroendocrine cells (1% of epithelial prostate cells) from the beginning of its development but evidence suggests that it derives from a castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) that has enhanced mechanisms to change its lineage, transdifferentiate from PRAD and express neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD56, neuron-specific enolase (NSE) or insulinoma-associated protein 1 [161, 162, 163]. A novel classification for these neoplasms was proposed in 2014 and in the latest 2022 WHO Classification of Urinary and Male Genital Tumors it has been recognised as treatment-related NEPC (t-NEPC) [164, 165]. Firstly, Bishop et al. [166] studied the changes in protein synthesis and gene expression that occur in enzalutamide-resistant cancer cells that allow them to dedifferentiate and acquire a subsequent neuroendocrine phenotype. Among the many findings, an Id2 upregulation was found in those with neuroendocrine differentiation in comparison to absent expression in CRPC cells [166]. At an epigenetic level, Zhang et al. [167] recently demonstrated an increased level of Id2 transcripts in neuroendocrine cells compared to those with androgen receptors and also found intense Id2 positivity by immunofluorescence in the former with a weak signal for adenocarcinoma cells. They also identified an increased acetylation of histone 3 in lysine residue at N-terminal position 27 (H3K27) in NEPC cells, which may explain why the Id2 gene is more active in the neuroendocrine lineage. Furthermore, the increased acetylation at H3K27 appears to drive the downstream effects of Id2, including the greatest increase in IFI6 and IFI27 gene expression—both involved in apoptosis—a decrease in HOXB13, an androgen co-stimulatory factor, and an upregulation of the IL-6/Jak/Stat3 pathway, which is associated with stemness. With other members of the Id family, a relationship with histone modifications has also been observed. The MYST/Esa1-associated factor 6 (MEAF6), a component of the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex, plays a key role in promoting gene transcription through the acetylation of histones H4 and H2A, leading to the upregulation of Id1 and Id3 [168]. These proteins, in turn, mediate the proliferative effects associated with MEAF6. However, they seem to only increase NEPC progression, rather than favoring the transdifferentiation process.

Id protein family are essential transcription factors for the development of diverse types of neoplasms due to their perpetuating effects on the stem-cell state, tumor proliferation as well as their inhibitory effects on differentiation. NENs are no exception to this and are also regulated by these molecules. However, it may be striking that GEP-NENs have little evidence in this regard, despite being the most prevalent type. Among them, Id1 and Id2 have been most frequently linked to molecular processes in NENs, highlighting its prominent role in this context.

Selective targeting of Id proteins, particularly Id1, has shown promising results in reducing tumor proliferation and enhancing chemotherapy sensitivity in other cancer types. Within the field of NENs, inhibitors of the BMP receptor have demonstrated potential therapeutic benefits in SCLC. These findings pave the way for further exploration of Id proteins as actionable targets in NENs.

Additionally, epigenetic regulation is abundant within NENs and plays a pivotal role in their biology. However, when it comes to the involvement of Id proteins in these epigenetic mechanisms, most of the evidence stems from studies on NEPC. This reinforces the need for continued research, particularly in an era where understanding intracellular signaling pathways and epigenetic modulation holds the key to developing effective targeted therapies to challenge cancer.

DP, MG, PA, SW, AH, JT: conceptualization, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, visualization, writing, review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.