1 Department of Zoology, Dr. Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya Sagar, 470003 Sagar, Madhya Pradesh, India

2 Department of Emergency Medicine, Sanjay Gandhi Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, 226014 Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

3 Department of Physiology, Johann-Friedrich-Blumenbach-Institute for Zoology and Anthropology, Faculty of Biology Georg August University Göttingen, Göttingen and Goettingen Research Campus, D-38524 Sassenburg, Germany

4 Department of Zoology, Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gorakhpur University, 273009 Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, India

5 Department of Biotechnology & Bioinformatics, JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research, 570015 Mysuru, Karnataka, India

6 Indian Scientific Education and Technology Foundation, 226001 Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

7 NIMS Institute of Allied Medical Science, National Institute of Medical Sciences (NIMS), 303121 Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

8 Department of Zoology, Bar. Ramrao Deshmukh Arts, Smt. Indiraji Kapadia Commerce & Nya. Krishnarao Deshmukh Science College, 444701 Amravati, Maharashtra, India

9 Department of Chemistry Poona College, Savitribai Phule Pune University, 411007 Pune, Maharashtra, India

10 Department of Medical Laboratories, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Qassim University, 51452 Buraydah, Saudi Arabia

11 Department of Family & Community Medicine, College of Medicine, Imam Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, 13313 Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

12 Department of Clinical Laboratory Sciences, The Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, Taif University, 21944 Taif, Saudi Arabia

13 Centre of Biomedical Sciences Research (CBSR), Deanship of Scientific Research, Taif University, 21944 Taif, Saudi Arabia

14 Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, 11942 Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent cause of dementia and a significant contributor to health issues and mortality among older individuals. This condition involves a progressive deterioration in cognitive function and the onset of dementia. Recent advancements suggest that the development of AD is more intricate than its underlying brain abnormalities alone. In addition, Alzheimer’s disease, metabolic syndrome, and oxidative stress are all intricately linked to one another. Increased concentrations of circulating lipids and disturbances in glucose homeostasis contribute to the intensification of lipid oxidation, leading to a gradual depletion of the body’s antioxidant defenses. This heightened oxidative metabolism adversely impacts cell integrity, resulting in neuronal damage. Pathways commonly acknowledged as contributors to AD pathogenesis include alterations in synaptic plasticity, disorganization of neurons, and cell death. Abnormal metabolism of some membrane proteins is thought to cause the creation of amyloid (Aβ) oligomers, which are extremely hazardous to neurotransmission pathways, especially those involving acetylcholine. The interaction between Aβ oligomers and these neurotransmitter systems is thought to induce cellular dysfunction, an imbalance in neurotransmitter signaling, and, ultimately, the manifestation of neurological symptoms. Antioxidants have a significant impact on human health since they may improve the aging process by combating free radicals. Neurodegenerative diseases are currently incurable; however, they may be effectively managed. An appealing alternative is the utilization of natural antioxidants, such as polyphenols, through diet or dietary supplements, which offer numerous advantages. Within this framework, we have extensively examined the importance of oxidative stress in the advancement of Alzheimer’s disease, as well as the potential influence of antioxidants in mitigating its effects.

Keywords

- Alzheimer’s disease

- amyloid-beta

- amyloid plaques

- reactive oxygen species

- antioxidants

- tau protein

The unique histopathologic abnormalities known as tangles and plaques in the brain of a young persons with mental retardation were first described by Alois Alzheimer around the start of the 20th century. Impaired cognitive skills, including memory problems in the elderly, have been identified as aging symptoms and are hence referred to as “senile dementia”, a disorder whose frequency and incidence increase exponentially with population aging. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is currently recognized as the prevailing class of dementia, therefore rendering it a matter of significant public health importance [1]. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, predominantly affecting the older population and is associated with various health complications and increased death rates. The pursuit of a natural intervention to modify the progression of this disease is of significant interest, given its irreversible nature and profound detrimental effects on individuals affected by it [2]. AD is a neurological condition that impairs cognitive abilities. It is brought on by extracellular amyloid beta buildup that manifests as senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. The two types of Alzheimer’s disease that are presently identified are early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD) and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) [3]. People under 65 who do not have senile dementia are impacted by EOAD. A considerably more prevalent variation of AD is LOAD. Patients over 65 with known comorbidities often experience it. Individuals who have encountered depression exhibit a twofold increased likelihood of getting dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in comparison to those who have not experienced depression. The malfunction of specific neurotransmitter systems is implicated in the occurrence of neurodegenerative changes [4]. Early signs of AD already show abnormalities in the serotonin pathway. There is growing scientific evidence linking dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and up to 50% of AD patients may have symptoms of depression. Based on epidemiological research, the presence of depression has the potential to serve as a predictive factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and this assertion is substantiated by a meta-analysis, which revealed that patients who experience concurrent depression have earlier onset ages for Alzheimer’s disease. Additionally, because of the increased production of comparable pro-inflammatory cytokines, depression and AD both contribute to inflammation in the central nervous system [5]. Currently, this pathogenicity impacts around 44 million persons globally. The prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) and their associated pathological conditions is a significant concern within the current healthcare system. For international scientists, AD represents one of the most difficult pathological frameworks because of its complexity. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common kind of dementia seen in older adults, accounting for around 60 to 80 percent of all documented cases [6]. It’s vital to note that increasing losses of neurons, brain activity, and cognitive abilities are hallmarks of AD. An array of risk elements, which includes obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, air pollution, smoking and hypercholesterolemia, exert a substantial impact on the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and the design of approaches for preventive measures against this ailment [7]. Nutritional components and physical activity have been demonstrated to be effective variables that aid in its prevention. The amyloid-beta cascade theory, the tau protein hypothesis, the cholinergic hypothesis, and the oxidative hypothesis are all notable hypotheses on Alzheimer’s disease. These hypotheses may provide light on the underlying causes of the illness. Oxidative stress is a shared element in the development of neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and multiple sclerosis [8].

The onset of Alzheimer’s disease results in a significant decline in cognitive functioning, which has a significant negative impact on social and vocational activities. This is one of the most significant pathological burdens on individuals. Over 46 million individuals worldwide suffer from dementia, costing an estimated 818 billion in US dollars in 2015 and projected to reach 1 trillion dollars in 2018. The World Health Organisation has prioritised public health in light of the substantial economic and societal costs associated with Alzheimer’s disease [9]. The appearance of extracellular amyloid-beta (A

Numerous research studies have demonstrated that astrocytes influence the intercellular connection between glial cells and neurons, as well as between glial cells and blood vessels, hence contributing to the deterioration of cellular and functional characteristics associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [14, 15]. Astrocytes are crucial resident cells within the central nervous system (CNS) involved in several physiological functions. Astrocytes, like neurons, are a diverse group of cells that display many physical and functional characteristics [14, 15]. AD is distinguished by several notable attributes, like creation, aggregation and accumulation of A

The original source of the amyloid plaques is the amyloid precursor protein (APP). The alpha-, beta-, and gamma secretase enzymes are in charge of cleaving APP. The non-harmful pathway involves the enzymatic decomposition of the APP by alpha- and gamma-secretase at critical junctures, which favor the generation of soluble APP and limit the formation of toxic Ab by beta-secretase [19]. The pathogenic pathway involves the enzyme beta-secretase (BACE-1), which initiates the cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) molecule at the N-terminus of the A chain. The primary secretase involved in the metabolism of APP is BACE-1, an aspartyl protease embedded in the cell membrane. Secrease then digests the last piece of APP that is attached to the neuronal cell membrane [20]. Further cleavages result in the liberation of A

The pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is also associated with detrimental changes in the cholinergic system, characterized by the employment of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) to convert the neurotransmitter acetylcholine into choline and the acetate anion [23]. AChE has a CAS, or catalytic site, and a PAS, or peripheral anionic binding site. Acetylcholine is thought to first bind to the PAS before quickly diffusing to the CAS. Extensive cholinesterase enzyme, butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE), exhibits increased activity as the AD state worsens while AChE activity declines. The accumulation of the Abeta peptide is related to increased BuChE activity. Cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) are used to increase cholinergic neurotransmission, which is the basis of the current medication for AD patients [24]. Amyloid plaques exhibited elevated levels of Cu, Fe, and Zn when subjected to certain physical techniques, namely scanning transmission ion microscopy, Rutherford backscattering spectrometry, and particle-induced X-ray emission, with meticulous attention to detail [25]. As a result, it was discovered that the amounts of copper, zinc, and iron were approximately triple that in the surrounding tissues. An accurate evaluation of redox-active transition metals, namely iron (Fe) and copper (Cu), together with the redox-inactive metal zinc (Zn), has identified a crucial new element linked to Alzheimer’s disease (AD): The occurrence of oxidative stress induced by metallic elements [26, 27]. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors, including donepezil (administered at dosages ranging from 5 to 10 mg per day), rivastigmine (often prescribed at dosages ranging from 1.5 to 6 mg per day), and galantamine (suggested at dosages ranging from 16 to 24 mg per day), have been authorized as pharmacological interventions for the clinical management of Alzheimer’s disease [24]. Furthermore, memantine, an infrequently employed noncompetitive antagonist of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor, is suggested for administration at a dosage range of 5–20 mg/day [28]. These medications, while offering some relief, come with several unwanted side effects, including diarrhea, nausea, bradycardia, and potential liver toxicity. Furthermore, their primary limitation lies in their ability to only provide temporary symptom improvement without halting or altering the course of the disease. Despite amyloid

The pivotal event triggering the onset of Alzheimer’s disease is the enzymatic generation of the neurotoxic A

On a global scale, the World Alzheimer Report from 2015 reported that 46.8 million individuals were living with dementia, and this number is projected to nearly quadruple every 20 years [47]. Dementia affects approximately 5–8% of people over the age of 65, 15% of individuals over 75, and 25–50% of those over 85. In terms of regional distribution, Asia has the highest incidence with 22.9 million cases, followed by Europe with 10.5 million, and the Americas with 9.4 million [48]. It is worth noting that AD constitutes a substantial proportion of dementia cases, ranging from 50 to 75 percent. AD sufferers see a gradual deterioration in cognitive ability in comparison to persons who do not have the disorder. This decline is closely linked to a significant reduction in brain volume observed in AD patients. More specifically, the hippocampus experiences atrophy due to the loss of neurons and the deterioration of synapses [49], this brain region is responsible for spatial orientation and memory. The risk of developing AD rises up to 50% in individuals aged over 85, highlighting age as the most significant risk factor. Women have a higher likelihood of developing AD than men, possibly due to their longer life expectancy and the potential impact of reduced estrogen levels during menopause, which may increase the risk of AD. Extensive research is currently focused on a neurological disorder known as AD [50]. This condition has gained notoriety due to its increasing prevalence, particularly among older individuals, with the likelihood of developing it rising significantly with age. In fact, the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease may approach 50% for individuals older than 90 years, and a European study revealed a 7.2% incidence rate among the population aged over 65 [51]. Initial indications of Alzheimer’s disease often include deficits in short-term memory, difficulties in visuospatial perception and impairments in language and executive function. The disease can be diagnosed by observing a decline in cognitive abilities. One cost-effective diagnostic tool for this purpose is the Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) test, which is considered a preferred choice in many healthcare systems over expensive laboratory tests relying on biochemical markers. Despite its simplicity, the MMSE test proves to be a robust tool for detecting the disease in its initial stages [52].

Oxidative stress is a condition characterized by the accumulation of reactive oxygen or nitrogen species to a level where the body can no longer effectively neutralize them. The connection between Alzheimer’s disease and oxidative stress is under extensive investigation, and it appears to hold promise as a potential target for therapeutic intervention [53]. The relationship between Alzheimer’s disease and oxidative stress has undergone thorough investigation and appears to hold significant potential as a therapeutic target. This work examines the existing body of knowledge regarding oxidative stress in AD and the broad implications of using medicine to target the molecular mechanisms and mediators of the pathways implicated in oxidative stress and damage [54].

There is a great amount of research suggesting that oxidative and nitrosative stress significantly contribute to the progression of AD, resulting in the impairment of vital cellular elements like nucleic acids, lipids and proteins [55]. Oxidative stress (OS) occurs when the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) exceeds the cellular antioxidant defense system capacity. Likewise, OS arises as a result of the buildup of oxidized or impaired macromolecules that are insufficiently eliminated and replenished. The assemblage of antioxidant enzymes, comprising superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), glutaredoxins, thioredoxins and catalase (CAT), in conjunction with non-enzymatic antioxidant compounds, forms a fundamental defensive mechanism within the cellular environment [56]. Within the framework of AD, there is a decline or deterioration in the operation of antioxidant enzymes, as evidenced by a decrease in their particular activity. Indeed, several investigations have verified that dysfunction in mitochondria, principally caused by the production of ROS, plays a substantial role in the pathogenesis of AD [57]. The presence of A

Apart from these commonly observed protein modification markers, protein oxidation and nitrosylation can lead to S-nitrosylation and methionine oxidation (sulfoxidation). S-nitrosylation is a chemical reaction involving the cysteine group and N2O3, resulting in the formation of S-nitrosothiol (SNO). The control of SNO levels is quite complex, including the actions of nitrosylases and denitrosylases, which add or eliminate the NO modification, but also a homeostatic system of nitrosylated proteins. SNO modification plays a critical role in intracellular signaling based on redox reactions, and alterations in the SNO profile have been observed in Alzheimer’s disease [59]. Over the course of more than thirty years of research, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted approval for only five prescription drugs for Alzheimer’s disease, and none of these medications target amyloid or tau. While these treatments do not provide a cure or a halt to the disease’s progression, they are employed to address dementia-related symptoms such as memory loss and confusion. Galantamine, rivastigmine, and donepezil are administered to mild to moderate Alzheimer’s patients, while memantine and memantine/donepezil are given to moderate to severe patients [60].

Regrettably, more than 200 phase II/III clinical trials assessing over 100 potential medications have experienced significant failures, resulting in substantial financial costs and decades of research efforts. Several methodological factors pertaining to the design of clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have been related to these disappointments, including issues like inadequate dosing, insufficient bioavailability, challenges in patient recruitment/selection and compliance, inconsistencies in cognitive assessment methods, inappropriate timing of interventions, and difficulties in evaluating target engagement [61]. These issues raise questions about whether the current drugs are appropriately targeting the underlying pathological elements or if a multi-target approach is needed to bring about actual changes in the disease rather than just symptom alleviation. Several therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer’s disease are currently in their preliminary or theoretical phases, undergoing experimentation in controlled laboratory settings or animal subjects, while others are now undergoing evaluation in clinical trials [62].

Currently, AD affects approximately 24 million individuals worldwide [63]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results often provide support for the clinical assessment of probable AD. However, a more precise pre-mortem diagnosis can be achieved through a positron emission tomography (PET) scan that examines amyloid

Oxidative stress occurs when the creation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) exceeds the cell’s ability to neutralize them via its antioxidant defense systems. The major defense against oxidative stress within the cell consists of antioxidant enzymes, including SOD, GPx, glutaredoxins, thioredoxins and CAT [66]. Furthermore, the defense mechanism is augmented by non-enzymatic antioxidant substances, including vitamin E, vitamin C, vitamin A, uric acid, and carotenoids. The brain is highly vulnerable to oxidative imbalances due to several contributing variables. The entity in question exhibits a notable requirement for energy, consumes a considerable quantity of oxygen, contains a profusion of readily peroxidizable polyunsaturated fatty acids, possesses a substantial amount of iron that assists as a potent catalyst for ROS, and has a comparatively restricted availability of antioxidant enzymes. Due to this confluence of elements, the brain is exceptionally susceptible to oxidative stress. Damage to numerous brain components, including membranes such as plasma and mitochondrial membranes and structural and enzymatic proteins, can result from oxidative stress [67]. Oxidative events have the potential to cause long-lasting changes in the tertiary structure and execution of proteins, as well as damage to nucleic acids. Moreover, the existence of A oligomers in the brain might worsen the situation by infiltrating membrane bilayers, leading to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the deterioration of intracellular proteins and nucleic acids. One of the very reactive byproducts of lipid peroxidation is 4-hydroxy-2-trans-nonenal (HNE), which is primarily produced in the brain by the peroxidation of arachidonic acid. Arachidonic acid is a prevalent omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) present in neuronal membranes [68]. HNE has the ability to affect ATP synthase, which is the last part of the electron transport chain (ETC) that is responsible for producing ATP in mitochondria. Despite the existence of antioxidants that function to protect the cell from the detrimental effects, a tiny quantity of superoxide anion (

While nuclear factors-activated-

To put it differently, oxidative stress is responsible for at least some of the toxicity associated with A

ROS and RNS are generated as a result of regular metabolic processes or in response to cellular stressors, and they gradually build up in the body [87]. Extended exposure to ROS, in addition to its cumulative effect, results in cellular harm and hindered regeneration, which are strongly linked to age-related degenerative illnesses. The aged population is more vulnerable to degenerative illnesses due to elevated levels of pro-oxidant damage and a decline in antioxidant defence systems [88]. Neurons are highly active cells with a substantial oxygen demand, accounting for approximately a quarter of the body’s total oxygen consumption [89]. Consequently, neuronal cells generate significant amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), rendering them susceptible to free radical attacks. Neurons have relatively lower quantities of antioxidant defence molecules, such as glutathione (GSH), and a larger quantity of readily oxidizable polyunsaturated fatty acids, as compared to other types of cells. The existence of antioxidant enzymes, specifically hemeoxygenase (HO)-1 and superoxide dismutase (SOD)-1, within senile plaques provides significant evidence for the role of oxidative stress in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease [90]. Notably, it has been shown that oxidative stress is an early occurrence in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Elevated production and accumulation of ROS lead to increased levels of oxidized proteins, lipids, and DNA, which have been associated with Alzheimer’s disease [67]. ROS molecules have been demonstrated to augment the synthesis, aberrant folding, and accumulation (crosslinking) of amyloid beta. Amyloid beta peptides typically consist of 40–42 amino acid chains with the sequence: DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQKLVFFAEDVGSNKGAIIGLMVGGVVIA. The peptides mentioned are generated by proteolysis of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) as a consequence of cleavage by beta and gamma proteases, frequently as a result of hereditary abnormalities in the APP gene. Methionine, which is located at position 35 in the Amyloid beta protein sequence, is an amino acid residue highly susceptible to oxidation. ROS can oxidize methionine side chains under physiological conditions, leading to the presence of oxidized forms of methionine in Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue [91]. Methionine can be oxidized either by the addition of two electrons to form methionine sulfoxide or by the loss of one electron, resulting in a sulfuranyl free radical. The oxidative changes have the potential to induce harm to neighbouring neuronal proteins and lipids [92].

AD is linked with the occurrence of lipid oxidation in the brain tissue, which is a degenerative characteristic [93]. The brain contains highly susceptible polyunsaturated fatty acids, including arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acids, which are prone to oxidation. Lipid peroxidation causes the degradation of neuronal membranes and produces several secondary substances including 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, acrolein, isoprostanes, and neuroprostanes. A specific investigation found elevated levels of the lipid peroxidation biomarker called thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) in the synaptosomal membrane portion of neurons impacted by Alzheimer’s disease [94]. Alzheimer’s disease is linked to oxidative damage of DNA, along with the oxidation of amyloid beta and lipid peroxidation. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can damage DNA by causing uncontrolled alterations to nucleic acid bases [95]. Hydroxyl radicals have the ability to alter guanine nucleotides, resulting in the creation of 8-hydroxy guanine. This altered guanine has a propensity to form base pairs with adenine rather than cytosine. The oxidation of thiamine may lead to the creation of hydrogen bonds between 5-hydroxymethyluracil and adenine, enabling their coupling. In addition, reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and peroxynitrous acid have the ability to interact with nucleic acid bases, resulting in oxidative deamination by substituting NH2 groups with OH groups. The uncontrolled process can convert adenine, cytosine, and guanine into hypoxanthine, uracil, and xanthine, respectively. Hypoxanthine and uracil can both create erroneous base pairs with cytosine and adenine. The occurrence of oxidised DNA bases in the brains of individuals with AD, such as 8-hydroxyadenine, 8-hydroxyguanine, thymine glycol, Fapy-guanine, 5-hydroxyluracil, and Fapy-adenine, strongly emphasises the important contribution of DNA damage to the development of AD [96]. Researchers have discovered a much greater quantity of damaged DNA in neurons that have been exposed to A

ROS are endogenously generated as a result of normal metabolic processes within cells in living organisms [100]. ROS play a crucial role in preserving cellular balance and are implicated in several physiological processes, such as immunological responses and inflammation. The overproduction of ROS may be harmful, leading to oxidative harm to cell components, particularly the delicate mitochondrial structures that are highly susceptible to ROS-induced injury [101]. Given its substantial oxygen demand for proper functioning, the brain is particularly susceptible to the deleterious effects of ROS. In addition, the brain contains a limited number of enzymes and other antioxidant molecules, a substantial amount of iron (a potent catalyst for reactive oxygen species), and peroxidation-sensitive polyunsaturated fatty acids. Therefore, oxidative stress plays a substantial role in the advancement of neurodegenerative diseases, including AD. The biomolecules that experience the highest levels of oxidation in AD are the ones present in neuronal membranes, such as lipids, fatty acids and proteins. Changes in biomarker levels can function as prognostic indicators of AD, where oxidative stress is a pivotal contributor to its development and progression [102]. ROS are amphiphilic compounds distinguished by their unpaired electron that gives them their exceptionally high reactivity and short lifetime. Upon oxidation of biomolecules, the resultant species exhibit enhanced stability compared to the initial molecules and can serve as indicators of oxidative damage. Nucleic acids, proteins, and oxidised lipids are a few examples of these biomarkers. Biomarkers may also consist of variations in the concentrations of antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase, in addition to other antioxidant compounds. Due to their properties, antioxidant molecules hold promise in preventing and treating disorders related to oxidative stress, including neurodegenerative diseases [103]. Antioxidants consist primarily of compounds that possess the capacity to scavenge free radicals, thereby preventing the chain reaction of the radical propagation and reinstating the stability of the molecules involved.

Iron is a vital constituent of the human body, and its iron (II) forms, such as iron (II) ions or iron (II)L complexes (where L is a coordinated ligand), can engage in chemical processes referred to as Fenton or Fenton-like reactions. These reactions involve the combination of iron with H2O2 to produce hydroxyl radicals (

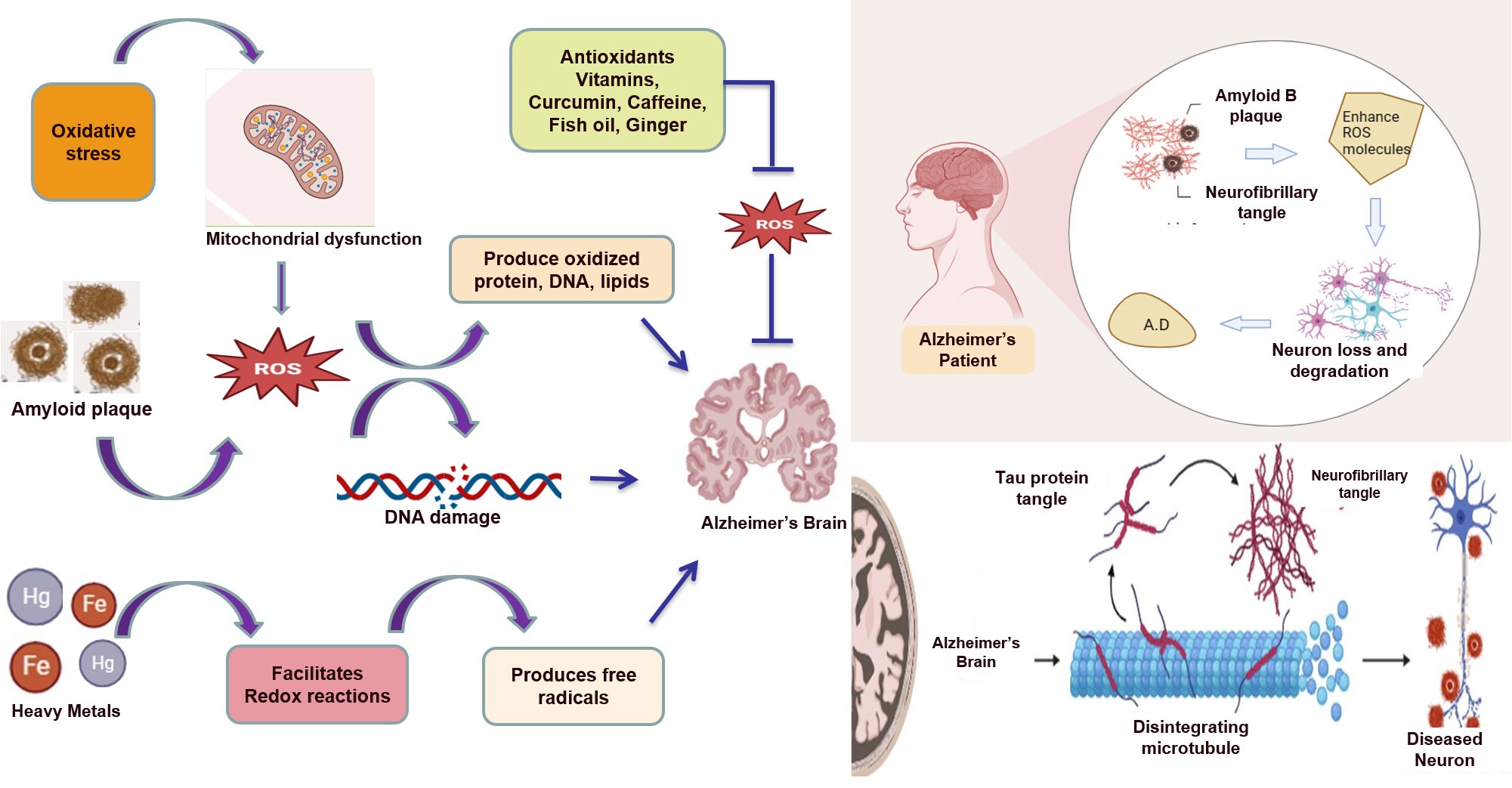

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Amyloid beta plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and heavy metals all contribute to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and, ultimately, Alzheimer’s disease. Antioxidants can inhibit the formation of ROS and protect against neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease.

Increased concentrations of redox-active iron have been suggested as possible catalysts for the clumping together of amyloid-

The regulation of these secondary systems is predominantly carried out by Kelch-like erythroid-derived cap‘n’collar homolog (ECH)-associated protein 1 (Keap1) and NF-E2-related factor 2. Keap1 typically acts as an actin-binding protein that keeps Nrf2 in the cytoplasm. It functions as a protein that binds to a substrate and facilitates its interaction with the Cullin3-containing E3-ligase complex [108]. This intricate molecule specifically targets Nrf2 for the process of ubiquitination and subsequent destruction by the proteasome. Crucially, Keap1 is responsive to changes in redox state and can be altered by different oxidising agents and electrophiles. Oxidative stress (OS) hinders the breakdown of Nrf2 by Keap1, resulting in the buildup of Nrf2 in the nucleus [109]. Within the nucleus, Nrf2 combines with a small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (Maf) protein to create heterodimers, which then attach to antioxidant response elements (AREs). This relationship is responsible for the stimulation of the synthesis of phase II antioxidant enzymes, which include glutamate-cysteine ligase, glutathione S transferases (GSTs), NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (Nqo1) and heme oxygenase 1 (Hmox1). In addition, Nrf2 is involved in maintaining cellular proteostasis via controlling the expression of molecular chaperones and different subunits of the proteasome [110]. Aside from antioxidant enzymes, the cellular components are shielded from reactive oxygen species (ROS) by small molecules and non-enzymatic antioxidants, such as natural flavonoids, vitamins, thiol antioxidants and carotenoids. Antioxidants play a crucial role in protecting cellular components against oxidative injury [111]. While adequate level of ROS are critical for the proper functioning of physiological systems, elevated levels have been associated with oxidative damage to various cellular components and compartments. The oxidative damage manifests as structural and functional anomalies in macromolecules, specifically lipids and proteins, distributed throughout many brain areas. For instance, elevated levels of oxidative stress linked to cell membranes have been identified in brain tissue from individuals with AD. The elevated levels of oxidative stress detected are correlated with the buildup of cholesterol and ceramides in clustered microdomains within samples of brain tissue affected by AD [112]. Notably, antioxidants like vitamin E and ceramide inhibitors have been shown to prevent the formation of these microdomains. The formation of such microdomains has been extensively studied, with one significant finding being that the aggregation of extracellular A beta at the cell membrane leads to oxidative damage associated with the membrane. The oxidative stress occurring at the membrane level is distinguished by the process of lipid peroxidation, which leads to the formation of the neurotoxic compound known as 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE). Hydroxynonenal (HNE) has been identified in the first phases of AD advancement and exhibits a clear correlation with the extent of neuronal damage and degeneration [113]. Furthermore, it has been observed that oxidative stress has the ability to stimulate pathways that are associated with the pathogenesis of AD. An example of this is the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) p38 in response to oxidative stress induced by A beta. One of the many roles of p38 is to stimulate the phosphorylation of tau in primary neuronal models. This process can be blocked by administering a p38 inhibitor or vitamin E before the therapy [114]. The veracity of these findings has been validated in vivo by the utilisation of an APP/PS1 transgenic mice model for AD. Oxidative stress associated with Alzheimer’s disease leads to significant deterioration of nucleic acids through oxidation. This damage leads to alterations in the structure of DNA. Mitochondrial DNA and RNA have also been found to be oxidized in various diseases, not just Alzheimer’s disease [113]. One specific aspect of DNA/RNA oxidation is the conversion of guanosine to 8-hydroxyguanosine (8-oxoG). Autopsy study of brain tissues from Alzheimer’s disease patients have revealed high levels of 8-oxoG in neurons in regions such as the hippocampus, subiculum, entorhinal cortex, and various neocortical areas [115]. Furthermore, RNA oxidation in the frontoparietal cortex, hippocampus, cortical neurons, and white matter of aged rats has increased significantly. These findings indicate that the damage caused by oxidative stress to DNA and RNA adds to the progress of neurological disorders and the ageing process. Additionally, both amyloid beta (A

Nitric oxide synthase catalyses the conversion of arginine to citrulline, resulting in the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO). NO has the tendency to interact with O2, resulting in the formation of peroxynitrite (ONOO). In the presence of reduced transition metals (Fe+2/+3), H2O2 is converted into the harmful hydroxyl radical (HO) through Fenton and/or Haber-Weiss reactions [124]. The HO radical has the potential to cause oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, DNA, and carbohydrates. Impairment of the electron transport chain (ETC) results in the failure of the antioxidant system to counteract reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing an elevation in ROS generation and subsequent neuronal damage. The coexistence of okadaic acid and oxidative stress in AD results in an upregulation of tau protein phosphorylation and neuronal demise. It is important to mention that ROS and RNS can exert either harmful or advantageous impacts on biological systems [125].

Antioxidants are like protective substances that help reduce the damage caused by oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is when harmful molecules in our body cause damage and induce degeneration. Antioxidants work in two ways: Primary antioxidants and secondary antioxidants. Primary ones fight against harmful molecules and stop them from causing damage, while secondary ones help other antioxidants work better. These antioxidants are important because they can help prevent health problems like Alzheimer’s disease [73]. Our body has a natural defense system against these harmful molecules, and we can also get antioxidants from the food we eat. There are two types of antioxidant systems: one that our body makes on its own, and another that comes from the food we eat. Some important antioxidants in our body include glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and vitamin C. They help get rid of harmful molecules and keep our cells healthy [126]. The impact of nutrition on both cognitive and physical well-being is generally recognised. Multiple studies have demonstrated that dietary sources have a substantial impact in addressing AD [90, 99, 127]. Natural dietary antioxidants such as Vitamin C, E, carotenoids, flavonoids, polyphenols, and other compounds are part of this category. Furthermore, both literary sources and empirical research suggest that a suitable diet incorporating vitamins, proteins, and minerals can successfully supplement the medicine used in the treatment of AD. In addition, apple cider has been demonstrated to augment the activity of SOD, CAT and GPx in order to diminish lipid peroxidation, according to stated sources [128].

Dietary potassium plays an important role in diminishing reactive oxygen species (ROS), modifying the pattern of A

Resveratrol, a kind of caloric restriction mimetic, has been proven to decrease oxidative stress in neurons in both, in in vivo rodent and in vitro neuronal cell models. It has also been shown to alleviate cognitive loss in persons diagnosed with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [131]. Nevertheless, the potential therapeutic impacts of these mimetics on the process of brain ageing have not been sufficiently investigated. The majority of persons find it difficult to adhere to long-term caloric restriction, and the effects of this restriction on cognitive ageing have not been thoroughly investigated. Clinical trials investigating caloric restriction frequently encounter constraints regarding the length of time and the degree of caloric restriction. Moreover, investigations employing caloric restriction mimetics have shown inconclusive outcomes [132]. In contrast, long-term exercise appears to be a more feasible approach to stimulate brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) production and create lifelong hormetic conditions compared to calorie restriction [133]. Clinical research on the long-term effects of exercise is becoming more prevalent, which is an encouraging development. Nevertheless, there is a requirement for comprehensive and extensive exercise intervention studies that address both the typical deterioration in cognitive function associated with ageing and the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Several clinical studies often employ small and homogeneous sample sets to investigate the effects of exercise over very brief periods [133, 134]. Therefore, it is essential for investigations to broaden the scope, diversity, and duration of their exercise interventions. This may involve comparing individuals who have exercised throughout their lifetimes with those who have been inactive in their older age. It is crucial for clinical studies to not only assess cognitive indicators but also to examine oxidative stress markers in order to gain a better understanding of their role in the cognitive benefits induced by exercise. Research has demonstrated that engaging in exercise over an extended period of time can decrease the detrimental consequences of oxidative stress, promote the return of antioxidant activity, decrease the presence of disease indicators, and improve the brain’s ability to withstand toxic substances. Among the known treatments, long-term physical exercise holds the greatest potential for reducing oxidative stress while supporting the optimal balance of stressors required for optimal brain function [22].

In addition to their antioxidant properties, natural substances have shown other crucial attributes in countering the advancement of AD through anti-inflammatory responses, warding off A

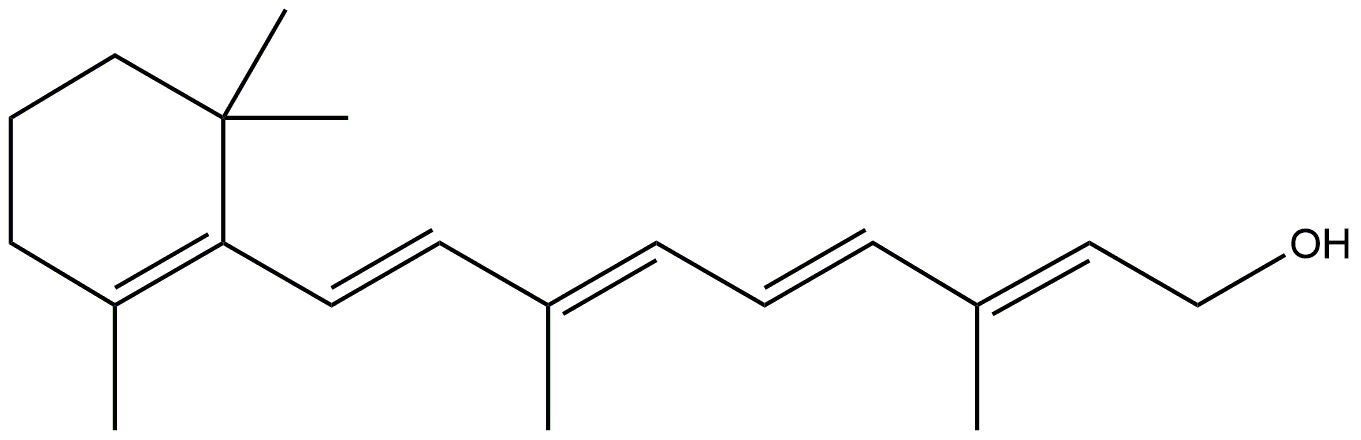

Vitamin A and its related compounds, known as retinoids, play important roles in various essential processes in the brain. These processes include the development of brain cells, the release of chemical messengers between nerve cells, and the strengthening of long-term memory [138]. Additionally, they have properties that protect against cell damage from harmful molecules called free radicals. Moreover, vitamin A and its derivatives can influence how genes work by interacting with specific receptors called retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs), which act like switches for gene activity. AD patients have a significant reduction in blood levels of beta-carotene and vitamin A. Interestingly, higher levels of beta-carotene in the blood are linked to better cognitive abilities in older individuals. The production of retinoid acid, a type of vitamin A, is reduced in response to A

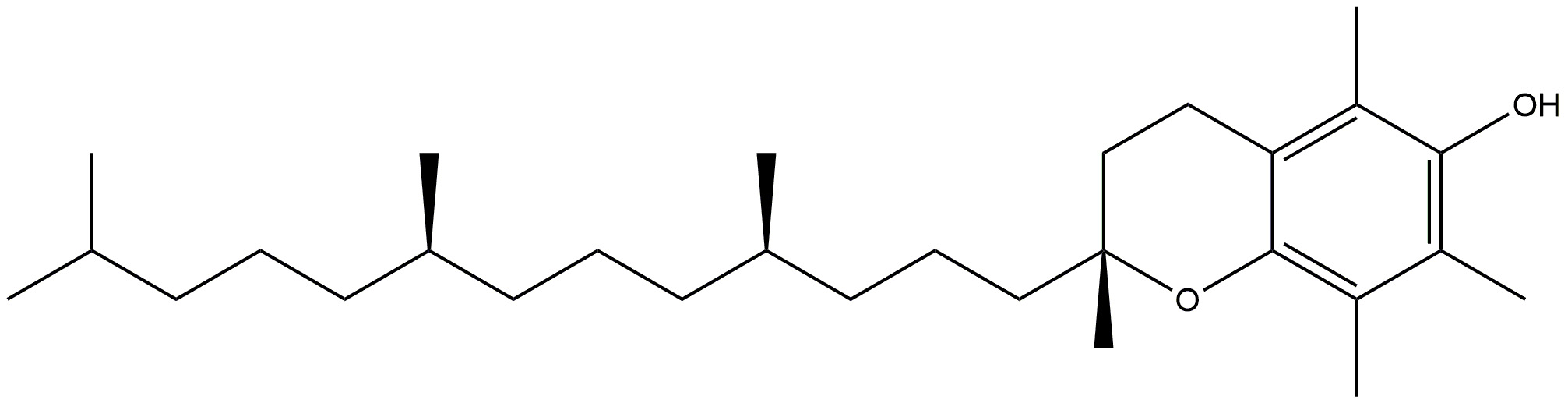

Vitamin E, a lipid-soluble antioxidant, has a crucial function in protecting the human body from oxidative harm. Vitamin E is available in eight distinct natural forms, which are categorised into four tocopherols and four tocotrienols. These forms are represented by the Greek letters

Multi discriminant analysis (MDA) was used by researchers to evaluate the extent of oxidative stress and quantify the activity of the antioxidant enzyme SOD. As expected, injecting A

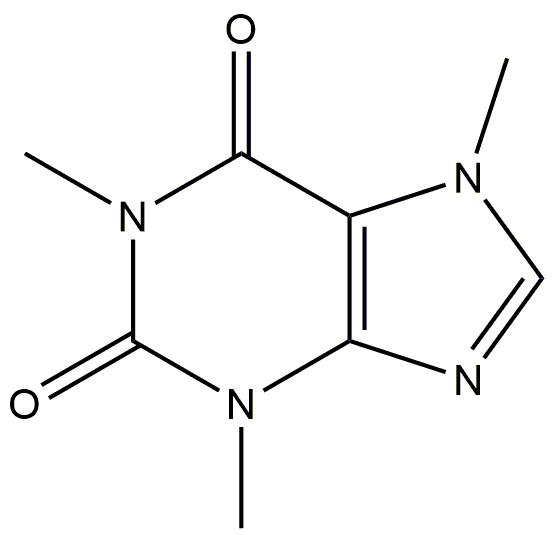

Caffeine, a commonly ingested alkaloid, has been discovered to hinder the accumulation of A

An additional noteworthy mechanism through which caffeine functions is through its ability to augment the expression of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf-2). The role of Nrf-2, a transcription factor that possesses a leucine zipper-rich basic motif, in mitigating oxidative stress has garnered considerable attention. Studies over the past decade have highlighted its significance in resisting oxidative damage, as observed in Nrf2 knockout mice that are more susceptible to various pathologies linked to oxidative stress [108, 110, 169]. Some components of decaffeinated coffee have shown potential benefits in neurodegenerative diseases. Nevertheless, there was no discernible safeguarding impact of decaffeinated coffee on the cognitive performance of elderly subjects. The available evidence from human studies is insufficient to definitively establish the effect of caffeine on the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. However, a substantial amount of data from various experimental investigations is increasingly showing the impact of caffeine on cognition and the progression of AD [161, 163, 167].

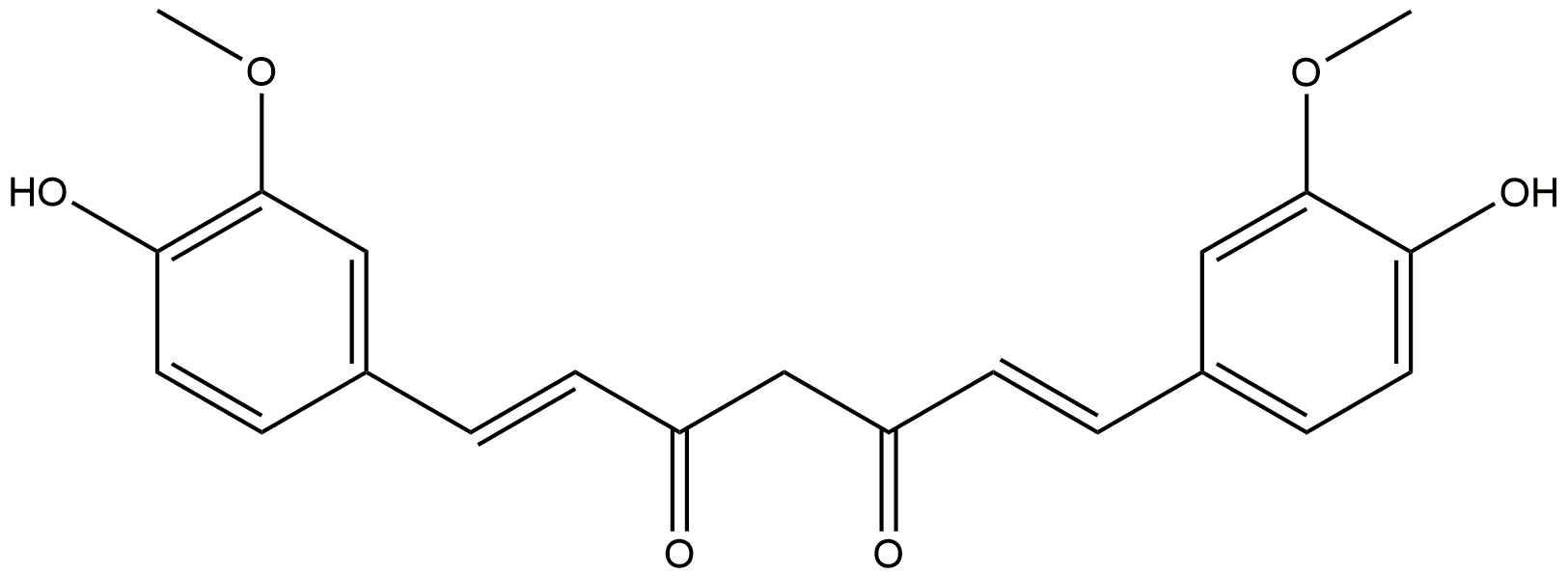

Curcumin, the principal component of turmeric spice, was discovered roughly two centuries ago. The substance is obtained from the dehydrated underground stems of the Curcuma longa L. plant, which is a member of the Zingiberaceae family. Traditional medicine has employed curcumin to address various ailments, ranging from skin issues, rheumatism, and wounds to conditions like diarrhea, urinary problems, constipation, and inflammation [170]. Furthermore, it has been employed as a dietary supplement and dye in drinks. Curcumin, an aromatic phenolic compound derived from volatile oils, is known for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant attributes. However, its effectiveness is constrained by challenges like poor absorption, rapid metabolism, limited blood-brain barrier penetration, and poor oral bioavailability. Despite demonstrating therapeutic potential, curcumin’s benefits have been more evident in animal studies than in human trials. This discrepancy can be attributed to factors such as the inadequate absorption and metabolism of curcumin in the human body [170, 171]. Notably, its low oral bioavailability results in low serum levels after ingestion, potentially leading to insufficient concentrations in the brain. Efforts are being made to overcome this issue by developing novel curcumin formulations, including curcumin-piperidine complexes, curcumin-phospholipid combinations, and polymeric micellar curcumin, to enhance its effectiveness and bioavailability [172]. AD symptoms typically manifest long after the onset of the disease and due to its pharmacodynamic nature, curcumin functions more as a neuroprotective agent than a direct treatment. The mechanisms underlying curcumin’s potential role in AD treatment involve inhibiting the formation and aggregation of amyloid-beta (A

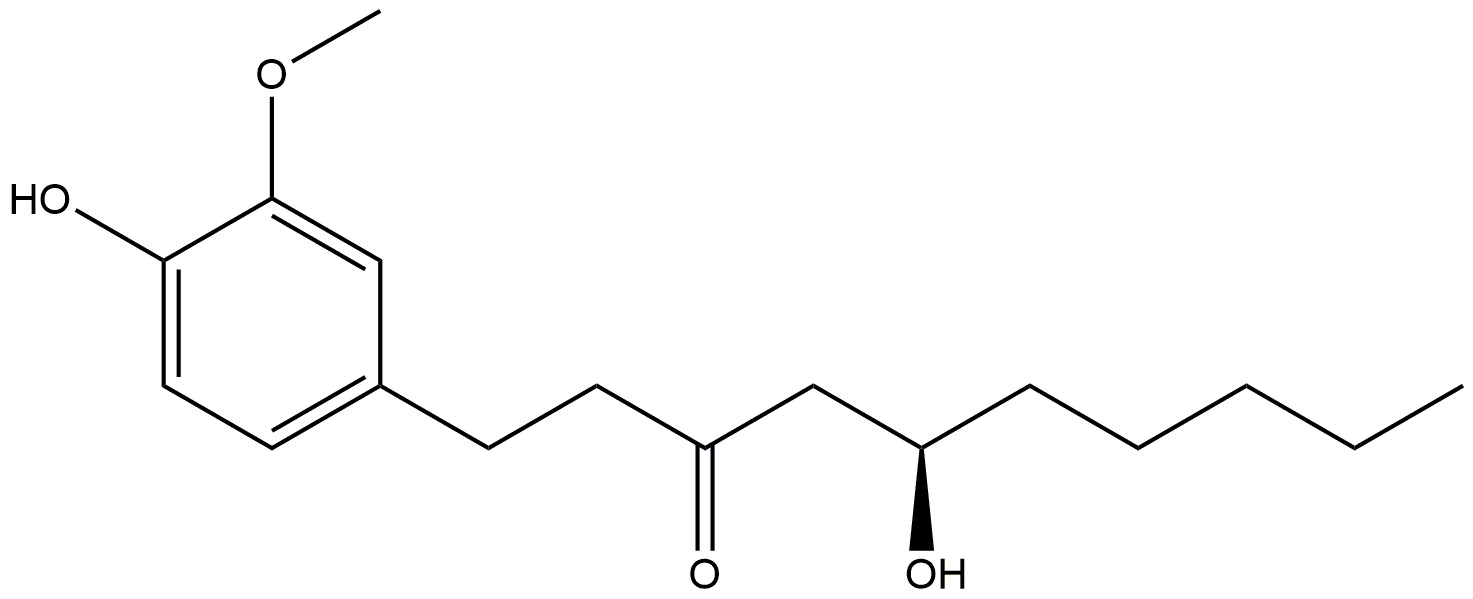

Ginger, specifically Zingiber officinale has been used to help with memory issues in AD. Ginger has some qualities that make it potentially useful for Alzheimer’s [174]. It can reduce inflammation and fight harmful molecules in the body. Studies have shown that ginger can boost a substance called nerve growth factor (NGF), which is important for memory [175, 176]. In mice, ginger increased NGF levels in the brain, leading to the growth of connections between brain cells [175]. Additionally, ginger seems to block some chemicals that cause inflammation in cells. Animal studies also suggest that ginger can affect certain genes related to inflammation in a good way. Ginger compounds can even cross the protective barrier around the brain, which means they might be able to help with brain diseases like Alzheimer’s. Ginger might not only be helpful for Alzheimer’s but also for other nervous system problems like brain tumors, strokes, nerve damage, depression, and sleep troubles [174, 175, 177, 178]. It is considered safe by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and can be used as a natural supplement to help with brain disorders. However, there aren’t many studies in humans yet, and some of the research involves mixtures of herbs, including ginger. Still, there’s promise in using ginger to improve memory and cognitive abilities. The active compounds found in ginger may play a role in controlling various aspects of Alzheimer’s disease, such as the response to external stimuli, response to oxidative stress, reactivity to toxic chemicals, lipid metabolism and atherosclerosis, and diabetic cardiomyopathy. In one study, people who took ginger extracts showed better thinking skills, especially at higher doses of 800 mg per day [178].

Several clinical investigations have demonstrated favourable results in elderly adults with moderate cognitive impairment when they receive supplementation of long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) [179]. It’s certainly promising to see evidence of a link between higher PUFA levels and improved cognitive performance in older individuals. This aligns with a growing body of research suggesting potential benefits of PUFAs for brain health. Higher concentrations of EPA + DHA have also been linked with a decreased likelihood of developing dementia [180]. In a meta-analysis, the consumption of these fatty acids was shown to have a positive impact. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are mostly incorporated into phospholipids, sphingolipids, and plasmalogens. They have a significant impact on the physical characteristics of cell membranes, including fluidity, shape, thickness, and permeability. Additionally, they influence the functioning of transmembrane proteins [181]. Research has shown that adding fish oil to the diet can be advantageous for persons suffering from most likely Alzheimer’s disease. Supplementing with this substance decreases the amount of lipoperoxides and breakdown products of nitric oxide in the blood, while hovering the ratio of reduced glutathione to oxidised glutathione. The concurrent decrease in the omega-6/omega-3 ratio in erythrocytes alongside increased GSH/GSSG and improved cognitive function adds another layer of complexity and intrigue to this puzzle. It has been observed that patients who maintain a consistent intake of DHA and EPA, both types of PUFAs, experience reduced oxidation of plasma proteins and lipids. This favourable result is significant due to the increased production of ROS linked to AD, which negatively impacts mitochondrial activity, metal equilibrium, and the degradation of antioxidant defences [182]. These factors directly affect neurotransmission and synaptic activity, which eventually leads to cognitive impairment. The production and accumulation of tau proteins that are hyperphosphorylated and amyloid are influenced by the aberrant cellular metabolism seen in AD. These factors can independently itensify mitochondrial dysfunction and further amplify ROS production, thereby maintaining a detrimental cycle that harms cognitive function (Table 1, Ref. [131, 147, 158, 172, 178, 183, 184]). The ingestion of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in individuals with AD was found to reduce the oxidation of proteins and lipids. This reduction is associated with an increase in catalase activity [183].

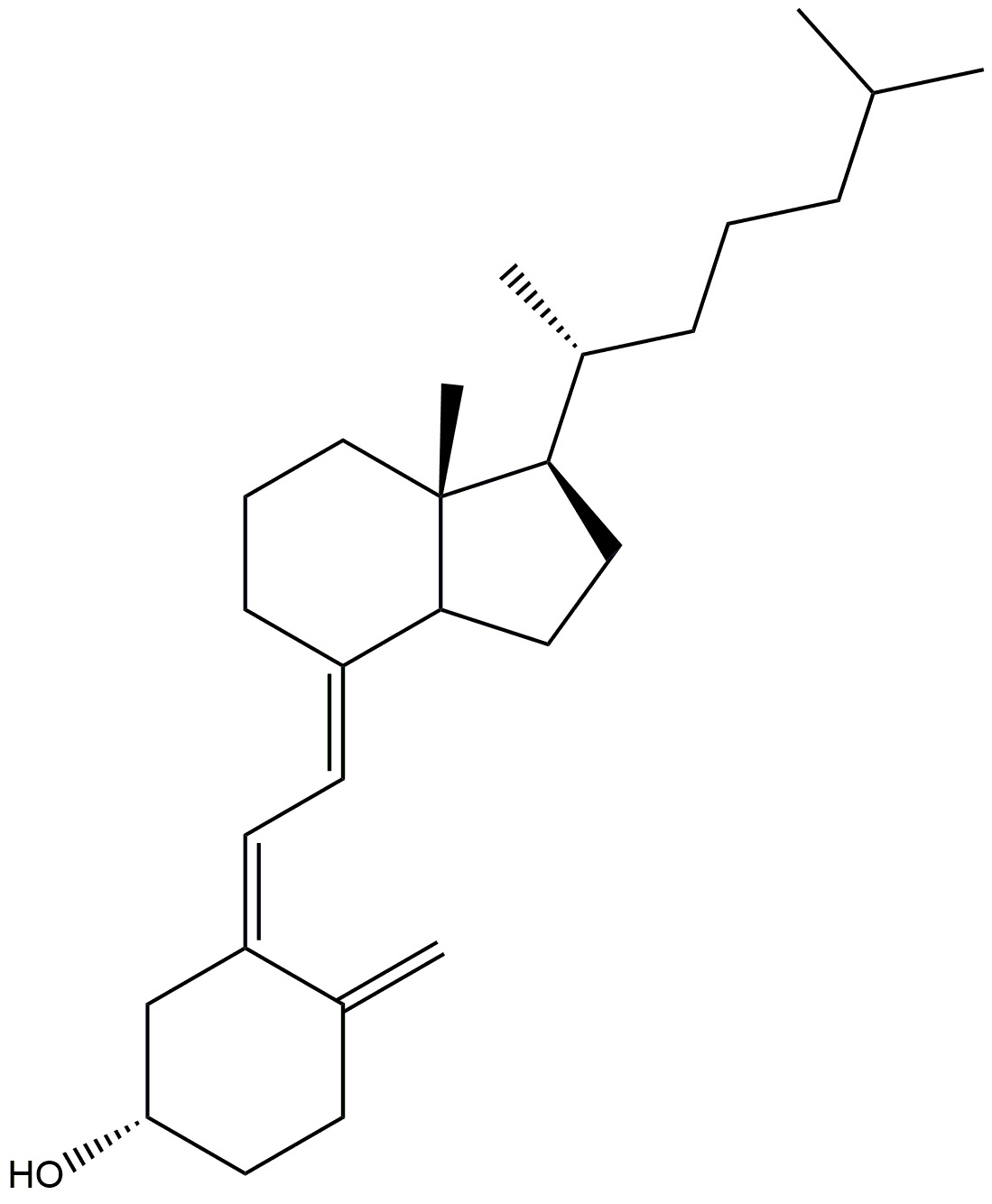

| Antioxidants | Structure | Functions | References |

| Vitamin A |  | Development of brain cells. | [147] |

| Strengthen of long term memory. | |||

| Protects brain from free radicals. | |||

| Shows therapeutic efficacy via its anti-amyloid/Tau, antioxidant, and pro-cholinergic effects. | |||

| Vitamin E |  | Fights against peroxyl radicals. | [131] |

| Vitamin E prevents the development of hyperphosphorylated tau, a well recognised indicator of Alzheimer’s disease, via inhibiting p38MAPK. | |||

| Vitamin D3 |  | Prevents neurodegeneration. | [158] |

| Adequate amount helps to slow down ageing process. | |||

| It induces phagocytosis to remove amyloid plaques and lowers primary cortical neurone cytotoxicity, apoptosis, and inflammatory responses. | |||

| Caffeine |  | Exerts its neuroprotective effects by binding to A2A receptors, that are triggered by the endogenous nucleoside adenosine. | [184] |

| Curcumin |  | It is anti-inflammatory. | [172] |

| It increases the phagocytosis of amyloid-beta, effectively clearing them from the brains of patients with AD. | |||

| Ginger |  | Reduces inflammation. | [178] |

| Shows anti-amyloidogenic potential, and cholinesterase inhibition. | |||

| Fish oil | Shows protection against beta-amyloid production, deposition in plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer’s disease. | [183] |

MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; AD, Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an intricate ailment characterised by the buildup of neurotoxic variants of the A

AChE, acetylcholinesterase; Ars, adenosine receptors; ATP, adenosine triphosphate;

RAN, MNM, IAM, RB, FMA, MA, MAM, ASA, WFA, AH, TG, BP, MPS, GTS and SKS have significantly contributed to the idea and design of the project. MAM, ASA, WFA, AH and TG performed the literature review and wrote sections (1-3). MNM designed the diagram and the illustrations. RAN, GTS and IAM designed the structures and their illustrations. RB, FMA, MA wrote section “4”. BP, MPS, and SKS critically authored and reviewed the texts for significant intellectual substance and approved the final version. All authors have adequately contributed to the work to assume public responsibility for relevant sections of the material and have consented to be responsible for all facets of the work, ensuring that inquiries about its accuracy or integrity are addressed. All authors made contributions to the manuscript’s editorial revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.