1 Department of Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Surgery, Guangzhou First People's Hospital, 510000 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, 510060 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

3 Department of Hepatic Surgery, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, 510060 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Background: The tumour mutation burden (TMB) is a valuable indicator of

the accumulation of somatic mutations, and is thought to be associated with the

biological behaviour and prognosis of tumours. However, the related genetic

mechanism for these association is still unclear. The aim of the present study

was to identify the key gene(s) associated with TMB in hepatocellular carcinoma

(HCC) and to investigate its biological functions, downstream transcription

factors, and mechanism of action. Methods: Patients in The Cancer Genome

Atlas-Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA-LIHC) database were classified

according to TMB signature-related genes. Key genes related to the TMB signature

and tumour prognosis were identified. Immunohistochemistry and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) were then

used to assess gene expression in clinical HCC tissues and HCC cells. Cells with

altered gene expression were evaluated for the effect on cell proliferation and

apoptosis, both in vitro and in vivo. Three independent

databases and cell sequencing data were used to identify the mechanisms involved

and the downstream transcription factors. The mechanism was also

studied by altering the expression of downstream transcription factors in

vitro. Result: The integrated cluster (IC) 2 group, characterized by 99

TMB signature-related genes, showed a significant different TMB score compared to

the IC1 group (p

Keywords

- tumour mutational burden

- RCAN2

- EHF

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- apoptosis

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer type worldwide and has the third highest mortality rate [1, 2]. Due to its insidious onset, a large number of patients are diagnosed with advanced HCC and systemic treatment is the main option for these patients [3]. However, a subset of patients still experiences tumour progression following the systemic treatment. Therefore, enhancing therapeutic efficacy remains the primary focus of clinical investigations.

Currently, some scholars have classified HCC into different subtypes based on gene expression, such as the Hoshida classification and the Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule (EpCAM) subtype [4, 5]. In addition, some researchers try to explore the changes of HCC biofunction caused by these mutations by detecting peripheral circulating tumour cells and so on [6]. However, there is currently no widely recognized classification method based on gene expression for HCC. Somatic mutation is an important factor in the efficacy of systemic treatment, and the accumulation of mutations can increase the heterogeneity and malignancy of tumours [7]. In HCC, tumour suppressor genes such as Tumour protein p53 (TP53) and Catenin beta 1 (CTNNB1) are commonly mutated genes [8, 9, 10]. The tumour mutation burden (TMB) represents the cumulative number of somatic gene mutations within a tumour, and always be served as one of the crucial metrics for assessing somatic mutational accumulation [11]. In malignancies such as lung cancer, its level has been substantiated to be intricately associated with the prognosis of immunotherapy [12]. However, the mechanism between TMB and prognosis remains unclear, and exploring the underlying mechanism is the research direction that interests us.

RCAN2 is one of the regulators of the calcineurin (RCAN) protein family and participates in phosphorylation by inhibiting the activation of calcineurin [13, 14]. However, the biological functions of RCAN2 are unclear in different tumours. In gastric carcinoma, RCAN2 stimulates cell growth and invasion activity but suppresses cell proliferation in CRC with KRAS-mutation [15, 16]. Our previous study demonstrated that RCAN2 expression was significantly different in HCC groups with different single nucleotide variants (SNV) levels and was associated with a favourable prognosis in HCC [17]. Thus, elucidating the underlying mechanism by which RCAN2 influences the survival of HCC cells holds significant implications for understanding the prognostic role of TMB in HCC.

Apoptosis is a prevalent form of programmed cell death, primarily triggered by

oxidative damage, calcium homeostasis imbalance, and mitochondrial impairment

[18, 19]. It is characterized by the activation of specific caspase and

mitochondrial control pathways. Under normal circumstances, tumour cells disrupt

the apoptosis signalling during their occurrence and progression, resulting in

reduced apoptotic response in tumour cells and enhanced growth and proliferation

[20]. Previous studies have demonstrated that

immune cells can secrete tumour necrosis

factor-

Hence, in this study, we regrouped patients into distinct cohorts based on the expression levels of TMB-related genes. By screening differentially expressed genes in various groups, we identified prognostic genes that are related to TMB. And then, RCAN2 was screened out for further mechanistic study. We validated the biofunction of RCAN2 in vitro and in vivo, and explored the underlying mechanisms through cross-validation in multiple independent databases. Finally, we elucidated the possible molecular pathways underlying the impact of RCAN2 on HCC apoptosis. It may provide a new perspective and target for systemic treatment in advanced HCC.

Externally validated datasets were generated from The Cancer Genome Atlas-Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA-LIHC) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) and the Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo, ID: GSE76427 and GSE64041) [25]. SHI-sequencing data and MHCC-LM3 cell sequencing data used in this study can be accessed from Supplementary Material and used after the consent of the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

All clinical samples of HCC tissues and matched adjacent normal liver tissues were obtained from patients at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center between 2015 and 2018. These were used for high-throughput sequencing, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), western blot, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) analyses. All clinical samples and data were accessed after obtaining approval of the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen university Cancer Center (No. 202011). Written informed consents from patients were waived due to the retrospective nature of our study.

Hep-3B cells were purchased from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell

Cultures (https://www.cellbank.org.cn/). MHCC-LM3 cells were obtained from the

Liver Cancer Institute, Fudan University (Shanghai, China). All cells were grown in Dulbecco’s

modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco, New York, NY, USA) with high glucose and

supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) in a 37 °C

incubator with 5% CO

Cell lines were authenticated by the Genomics Unit at TSINGKE, using Short Tandem Repeat profiling with a commercial kit from NUHIGHbio (Cat No: NH9347, NUHIGHbio, Suzhou, China). Mycoplasma test was performed in all cell lines every other week using the MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The mycoplasma test is negative.

The full-length sequence of RCAN2 was cloned into the lentiviral expression vector pReceiver-Lv105 (GeneCopoeia, Guangzhou, China) to construct the pReceiver-Lv105-RCAN2 recombinant plasmid. Target sequences were synthesized and inserted into the shRNA expression vector psi-LVRU6GP (GeneCopoeia) in order to construct shRNA of RCAN2. The shRNA of ETS homologous factor (EHF) was constructed by the vector pLenti-U6 (OBIO, Shanghai, China) and the shRNA with a nontargeting sequence was used as a negative control.

Virus packaging in HEK 293T cells was performed by co-transfection of

recombinant plasmid with Opti-MEM (Gibco) and Lenti-Pac HIV Expression Packaging

Kit (GeneCopoeia). Viral particles were harvested and used to transduce HCC cells

after 48 h of transfection. HCC cells (1

Total RNA from clinical tissues and HCC cells was isolated and purified with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for later sequencing. High-throughput sequencing of samples was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform (GENEWIZ, Suzhou, China). Sequencing reads were then cleaned and processed by hisat2, fastqc, samtools and subread.

Total RNA was extracted from cells and tissues using TRIzol reagent

(Invitrogen). ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix (TOYOBO, Shanghai, China) was used

to perform reverse transcription, and qPCR was then performed using the

THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR Mix (TOYOBO). The specific reaction conditions were as

follows: 95 °C for 15 s followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s

and 60 °C for 30 s.

| Gene symbol | Species | Primer | Sequence (5 |

| RCAN2 | Human | Forward | CAGCCCGAGCTAGGATAGAG |

| Reverse | CTGGCGTGGCATCGTTGAT | ||

| EHF | Human | Forward | CAGTGCAGTAGTGACCTGTTC |

| Reverse | CTGTGCTACCATAGTTGGTGTC | ||

| Human | Forward | CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC | |

| Reverse | CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT |

Total protein from clinical tissues and HCC cells was extracted using the RIPA buffer Kit (KeyGEN BioTECH Corporation, Nanjing, China). The protein concentration was determined using the Pierce Rapid Gold BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and then with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1–2 hours. Antibodies against RCAN2, caspase-3, caspase-8, caspase-9 and DR5 were purchased from Proteintech (http://www.ptgcn.com/). The antibody against EHF was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (https://www.thermofisher.cn/), while all other antibodies were purchased from CST (https://www.cellsignal.cn/).

In vitro, the proliferation rate of HCC cells was measured using the

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Hep-3B and MHCC-LM3 cells were seeded into 96-well

plates at 2

Tissue microarrays were constructed by Guangzhou Yuebin Biotech Laboratory (Guangzhou, China). Slides with tissue microarray sections were incubated overnight (8–12 h) at 4 °C with the antibody to RCAN2 (1:250). The reaction time with chromogenic reagent was 30 s. After IHC staining, all slides were scanned using a Vectra 2 scanning system (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and analysed by IHC scores with the Inform analysis system (Perkin Elmer). The median IHC score was used as the cut-off value, with patients categorized into high- and low-expression groups.

Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) staining assay (4A Biotech Corporation, Beijing, China) and Annexin V-PE/7-AAD staining assay (YEASEN, Shanghai, China) were used to detect cells in early and late apoptotic stages with the image-flow cytometry assay. The transfected cells were harvested and washed in cold PBS and resuspended in 500 µL solution with 5 µL Annexin V-PE and 10 µL 7-AAD. For the detection of MHCC-LM3 apoptotic cells following recovery of EHF expression, cells were incubated in 500 µL solution with 5 µL Annexin V-FITC and 10 µL PI. After incubation for 10–15 min at 15–25 °C, the cells were evaluated in a CytoFLEX S machine (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and analysed with CytExpert software (v 2.4.0.28, Beckman Coulter) for automated image-flow cytometry. A total of 20,000 cells were analysed per sample. Data were later analysed using Flowjo software (v10.5.3, BD Biosciences, Sussex, NJ, USA).

Four- to six-week-old male BALB/c nude mice were used for xenograft experiments.

For the subcutaneous HCC implantation model, 3

Differences between variables were assessed by Wilcoxon analysis, Mann-Whitney

test or two-tailed Student’s t test. Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank

tests were used to compare survival between groups. Multivariate Cox analysis was

performed to identify independent factors of prognosis. Data are presented as the

mean

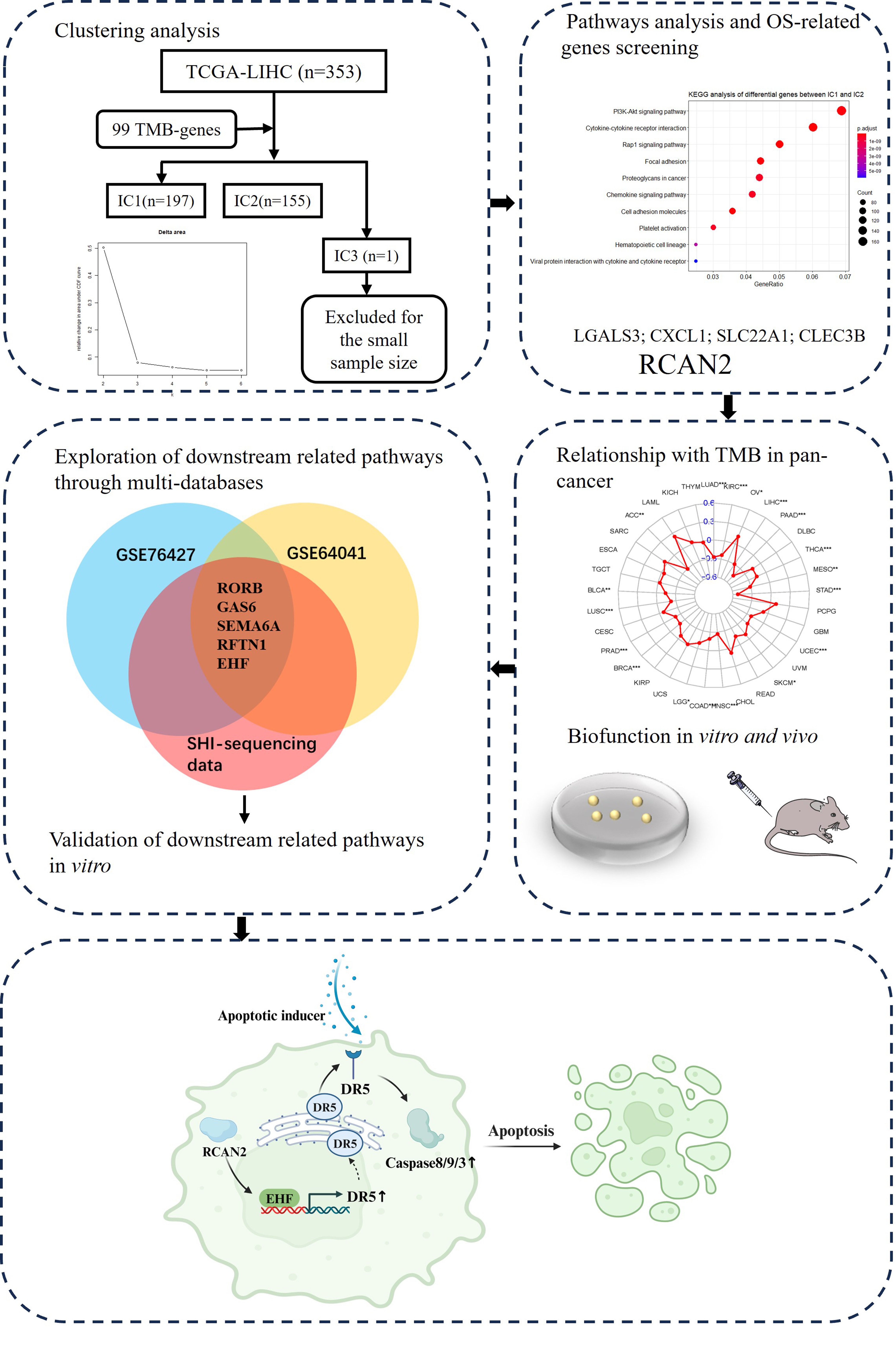

The workflow for this study is shown in Fig. 1. The TCGA-LIHC database was used

to examine the correlation between gene expression and TMB. This resulted in the

identification of 99 TMB signature-related genes when using the thresholds of

p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Workflow chart for the study. OS, overall survival; TMB, tumour mutation burden; TCGA-LIHC, The Cancer Genome Atlas-Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma; IC, integrated cluster.

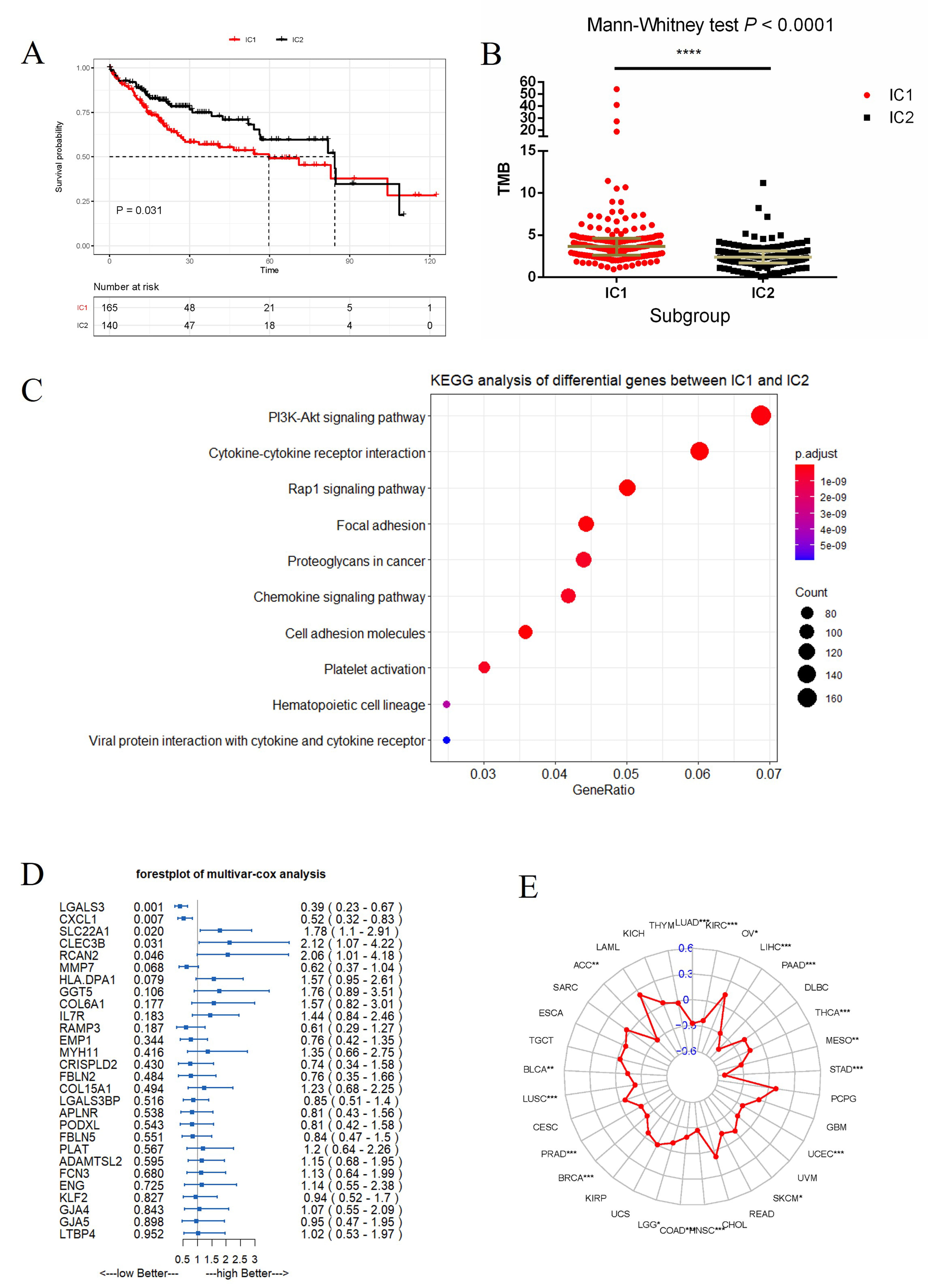

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Differences between IC1 and IC2 and the screening of key

prognostic genes related to TMB. (A,B) Differences in overall survival and TMB

between IC1 and IC2 (****p

Next, the differentially expressed genes (n = 5443) selected above were studied by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis of biological function. This revealed that PI3K-Akt signalling was the top enrichment pathway (Fig. 2C), and suggests that phosphorylation-related pathways may underlie the phenotypic differences between IC1 and IC2. Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to identify 5 key genes related to prognosis: Galectin 3 (LGALS3), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1), Solute carrier family 22 member 1 (SLC22A1), C-type lectin domain family 3 member B (CLEC3B) and RCAN2 (Fig. 2D). RCAN2 is a member of the regulator of calcineurin family that controls various cellular functions by affecting calcineurin activity. It was therefore selected for subsequent in vitro and in vivo studies.

The correlation coefficient between RCAN2 and TMB was calculated for multiple cancer types in the TCGA database. RCAN2 expression was found to correlate with TMB in 18 of 33 cancer types examined (Fig. 2E, Supplementary Table 1). In the large majority of these cancer types (17/18), a significant inverse correlation was observed between RCAN2 expression and TMB. This result suggests that accumulation of mutations reduces RCAN2 expression in tumours, thereby affecting prognosis.

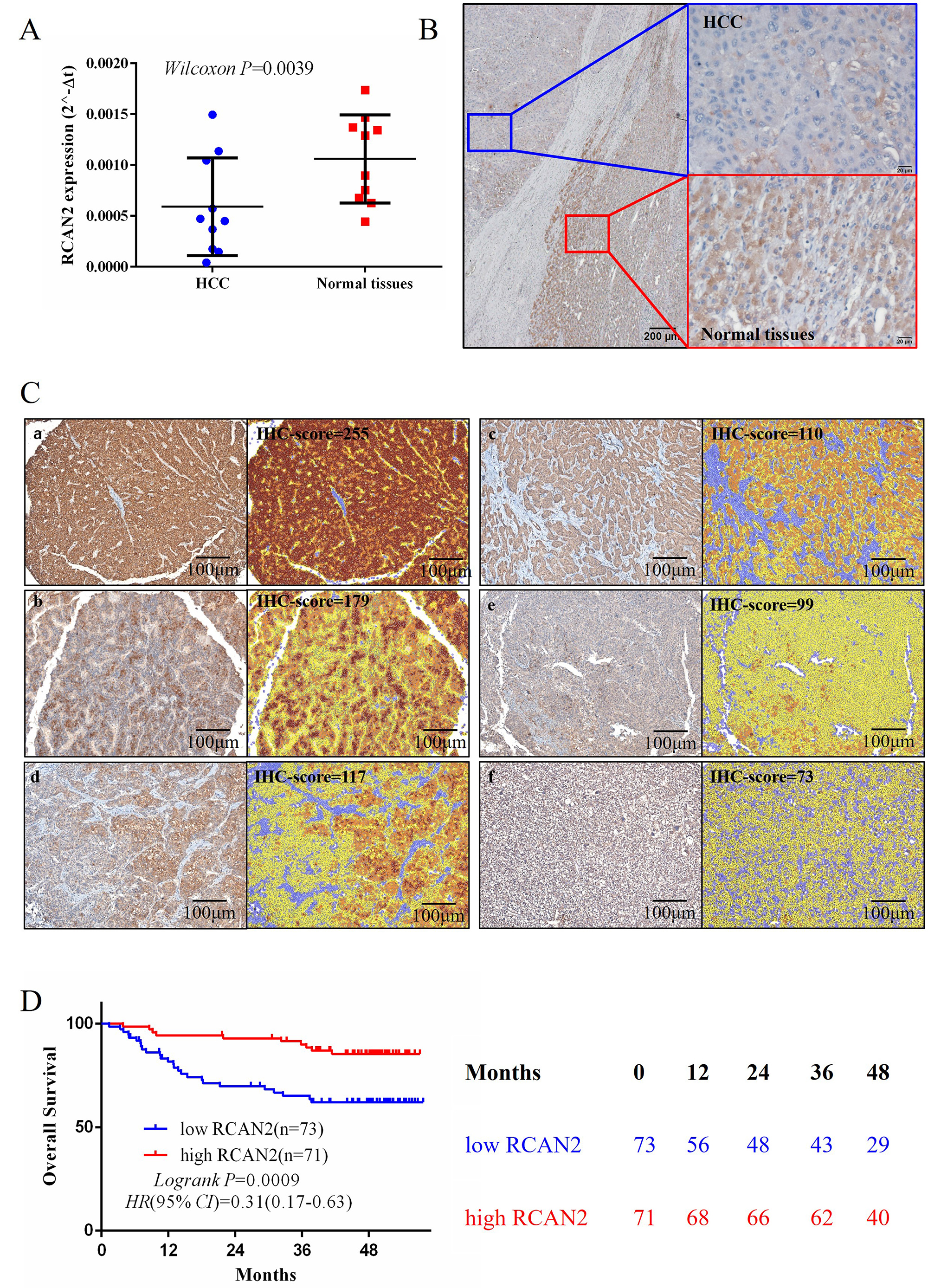

RCAN2 mRNA was extracted from 10 clinical samples, including HCC and adjacent normal tissues, and the level of RCAN2 was measured by qPCR. Corresponding tissues were used to validate RCAN2 protein expression by IHC staining. The results of these assays showed that the RCAN2 mRNA and protein expression were lower in HCC than in adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 3A,B).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.The RCAN2 expression in clinical HCC tissues and its correlationship of overall survival. (A,B) Comparison of RCAN2 mRNA and protein expression between HCC and normal tissues (scale bar = 200 µm). (C,D) IHC staining of RCAN2 expression in clinical HCC tissues, and the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of patients grouped according to their IHC score. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IHC, immunohistochemistry (scale bar = 100 µm).

To investigate the relationship between RCAN2 protein expression and the prognosis of HCC, surgical specimens were collected from 144 HCC patients for IHC staining. RCAN2 protein expression in each specimen was analysed and recorded as the IHC score using the Inform analysis system (Perkin Elmer, USA). Patients were subsequently divided into high-RCAN2 and low-RCAN2 groups according to the median IHC score of 120. The overall survival of the high-RCAN2 group was significantly better than the low-RCAN2 group (log-rank p = 0.0009, Fig. 3C,D).

The basic levels of mRNA and protein expression of RCAN2 in tumour cells and normal hepatocytes HL-7702 are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Based on the above results, we selected Hep-3B with a high mRNA expression level and LM3 with a low of mRNA expression level for our study.

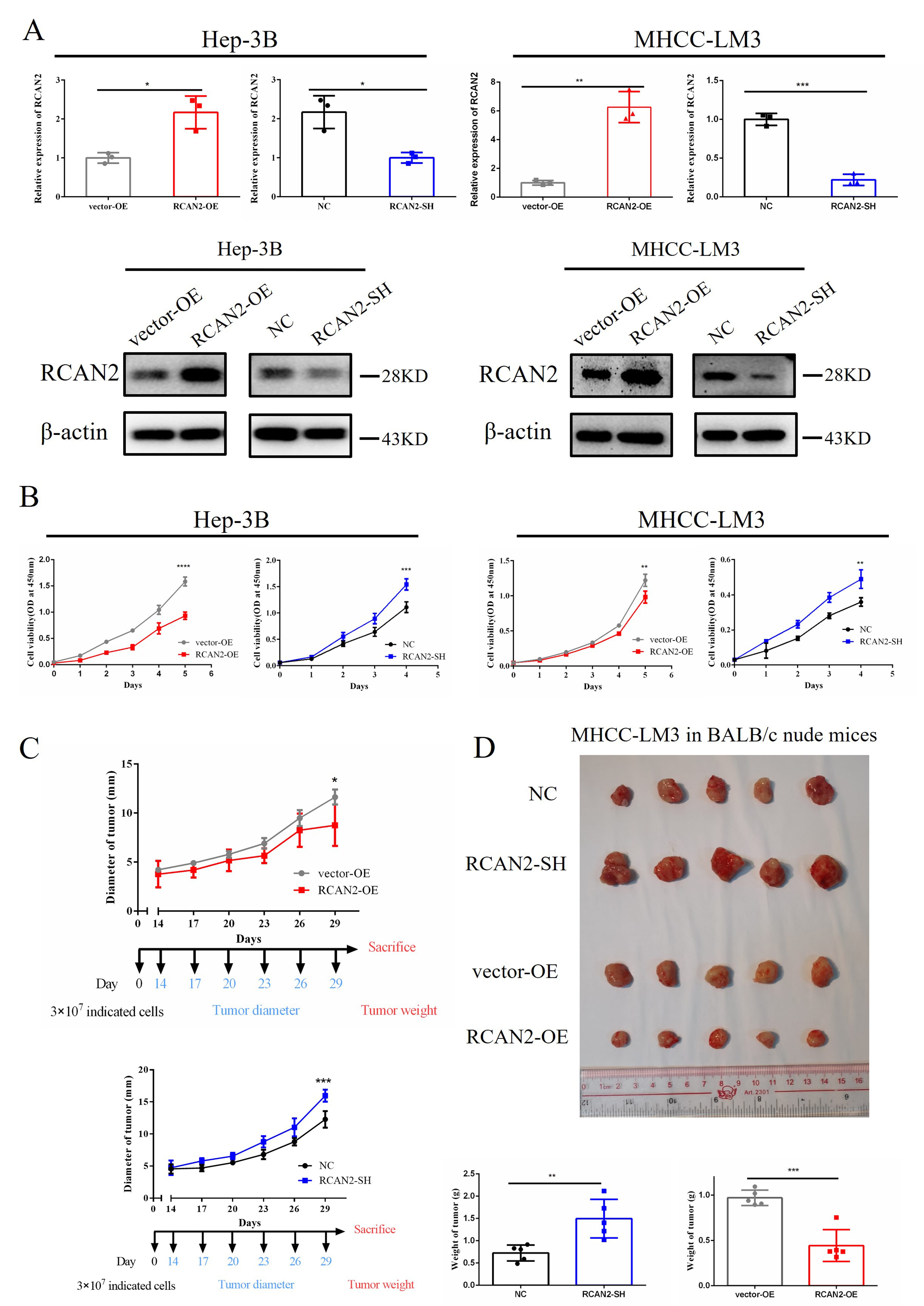

To explore the mechanism by which RCAN2 expression might impact the prognosis of HCC, the RCAN2-OE and RCAN2-SH plasmids were transfected into HCC cells (Hep-3B and MHCC-LM3). The expression of RCAN2 in these cells was then evaluated using qPCR and western blot analysis (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Overexpression of RCAN2 inhibits the growth of

HCC in vitro and in vivo, whereas HCC cells with RCAN2 knockdown show

enhanced proliferation. (A) RCAN2 mRNA and protein expression in Hep-3B

and MHCC-LM3 cells with altered RCAN2 expression. (B) Overexpression of

RCAN2 inhibits the in vitro proliferation of Hep-3B and

MHCC-LM3 cells, whereas HCC cells with RCAN2 knockdown show enhanced

proliferation. HCC cell proliferation was assessed by CCK-8 assay. (C,D)

Overexpression of RCAN2 inhibits the in vivo proliferation of

MHCC-LM3 cells, whereas HCC cells with RCAN2 knockdown show enhanced

proliferation. Cell proliferation was assessed by measurement of the tumour

diameter and weight (*p

The proliferation rate of HCC cells was assessed using the CCK-8 assay to determine cell viability at different time points. HCC cells that overexpressed RCAN2 showed a reduced proliferation rate, whereas HCC cells with RCAN2 knockdown showed enhanced proliferation (Fig. 4B). These findings suggest that upregulation of RCAN2 can effectively inhibit the proliferation of HCC cells in vitro.

The biological function of RCAN2 in BALB/c nude mice was also investigated using MHCC-LM3 cells with altered RCAN2 expression. Following subcutaneous injection of cells, the tumour diameter and weight were measured to evaluate tumour growth (Fig. 4C,D). Mice injected with cells overexpressing RCAN2 (RCAN2-OE) showed significantly smaller diameter (p = 0.021) and weight (p = 0.0003) compared to mice injected with cells overexpressing vector only (vector-OE). In addition, mice injected with cells that were knocked down for RCAN2 (RCAN2-SH) showed significantly greater tumour diameter (p = 0.008) and weight (p = 0.0063) than the negative control (NC) group. These findings suggest that RCAN2 has a significant biological role in HCC, and that its overexpression can effectively suppress both the in vitro and in vivo growth of HCC.

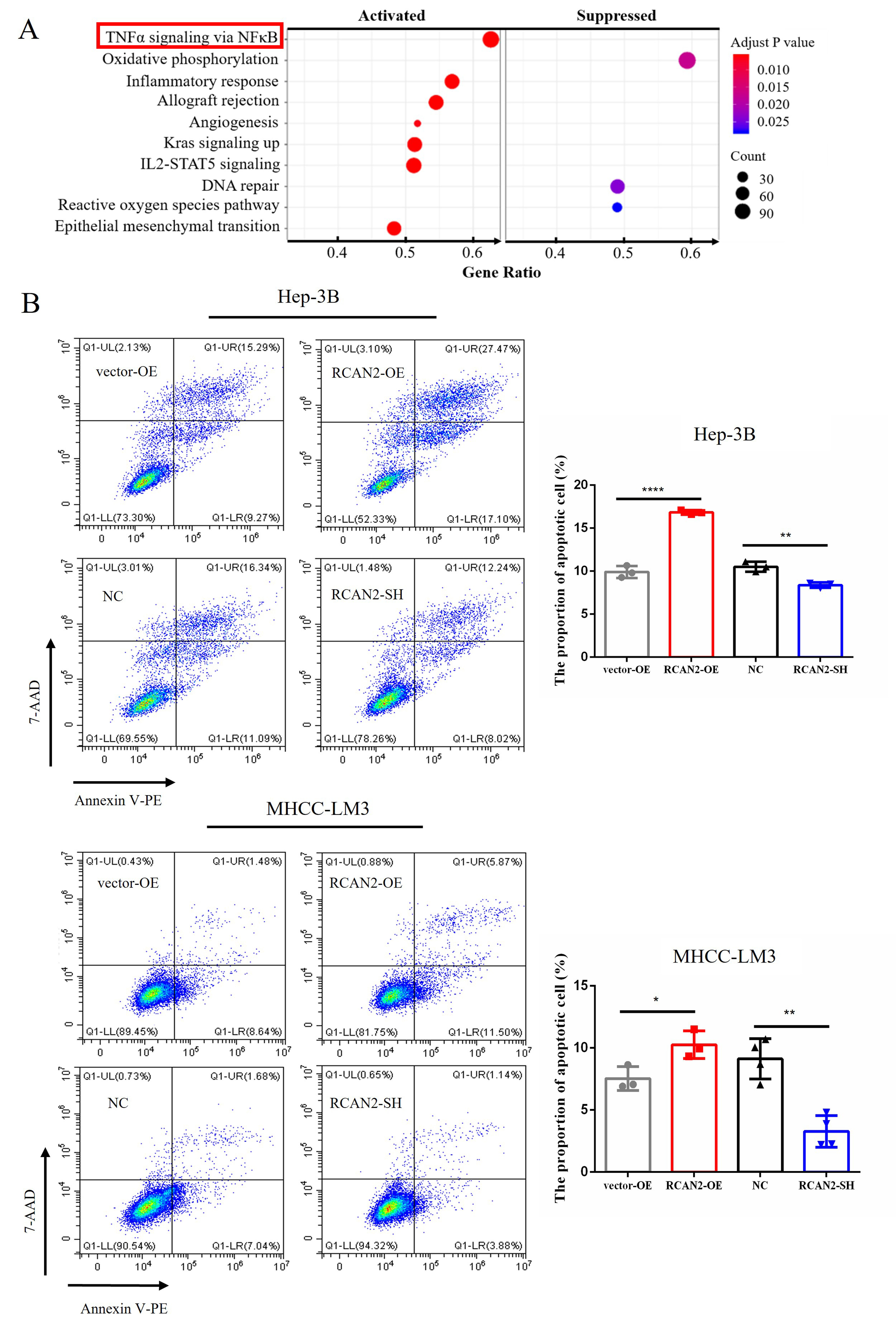

To explore the mechanism by which RCAN2 regulates the proliferation of

HCC, we screened for genes related to RCAN2 in the TCGA-LIHC database.

All genes were ordered by their R value and analysed through GSEA analysis. The

top three signalling pathways found to be associated with RCAN2

expression were TNF-

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.The pathway enrichment analysis of RCAN2 in

TCGA-LIHC database and the different proportions of apoptotic cells in different

HCC groups with altered RCAN2 expressions. (A) Pathway enrichment

analysis of the differentially expressed gene between RCAN2-high and

RCAN2-low group in TCGA-LIHC database. (B) After 12 h treatment of

transfected cells with recombinant human TNF-

Based on the results of GSEA analysis, flow cytometry was employed to evaluate

apoptosis in cells with altered RCAN2 expression. Concentration of 10

ng/mL TNF-

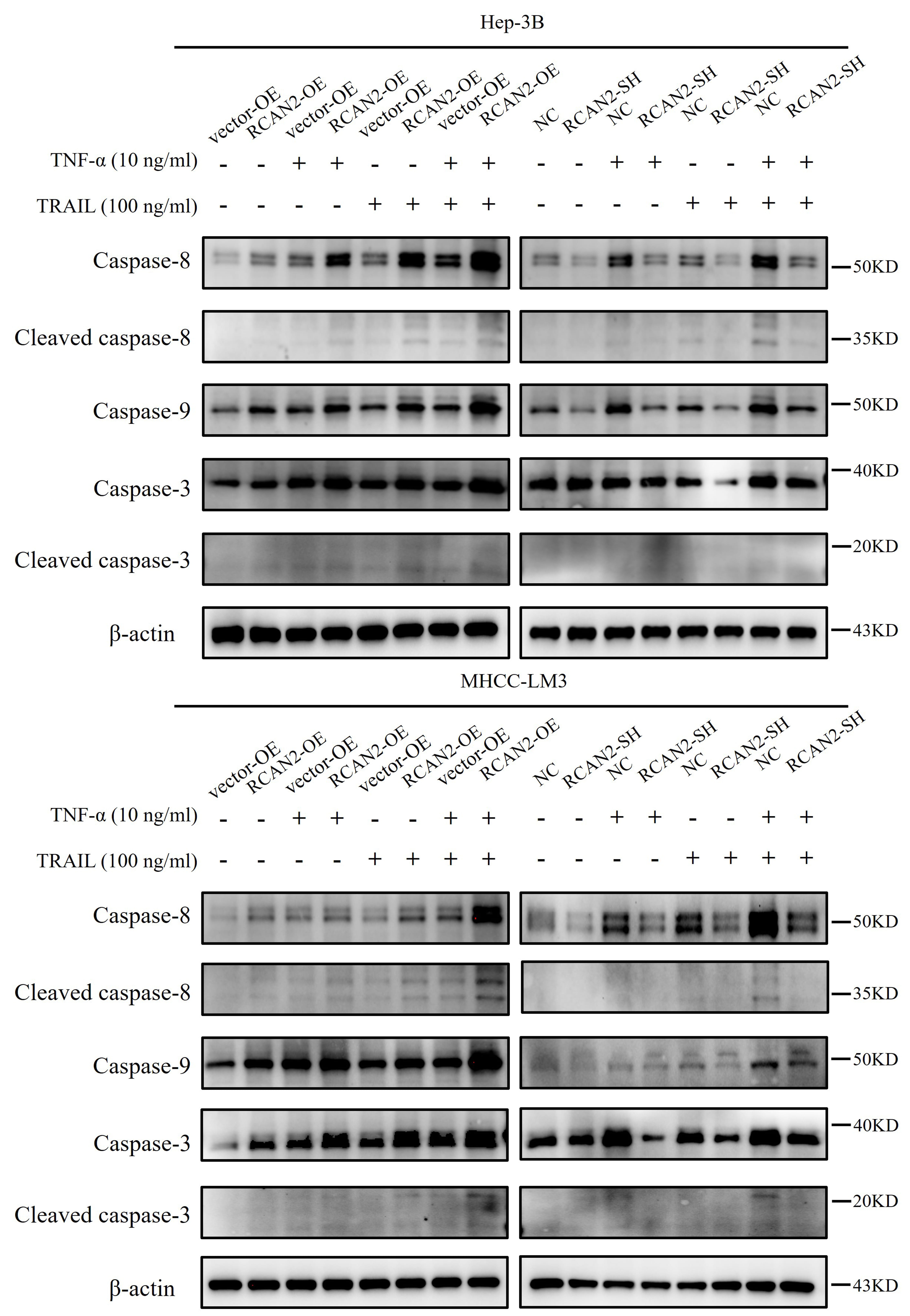

Under different incubation conditions with various apoptotic inducers, changes were also observed in the expression of apoptosis-related proteins, including caspase-8, cleaved caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 6). It showed that external apoptotic inducers could improve the expression of executive proteins in the apoptotic pathway in HCC cells with RCAN2 overexpression, including caspase-8, cleaved caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-3. Meanwhile, apoptosis-related proteins were down-regulated in RCAN2-SH group. Of note, caspase-9 is implicated in the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, suggesting that RCAN2 may modulate the apoptosis of HCC cells via the mitochondrial pathway of extrinsic apoptosis.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

The protein expression of caspase-8, caspase-9 and caspase-3 in

HCC cells cultured with or without 10 ng/mL TNF-

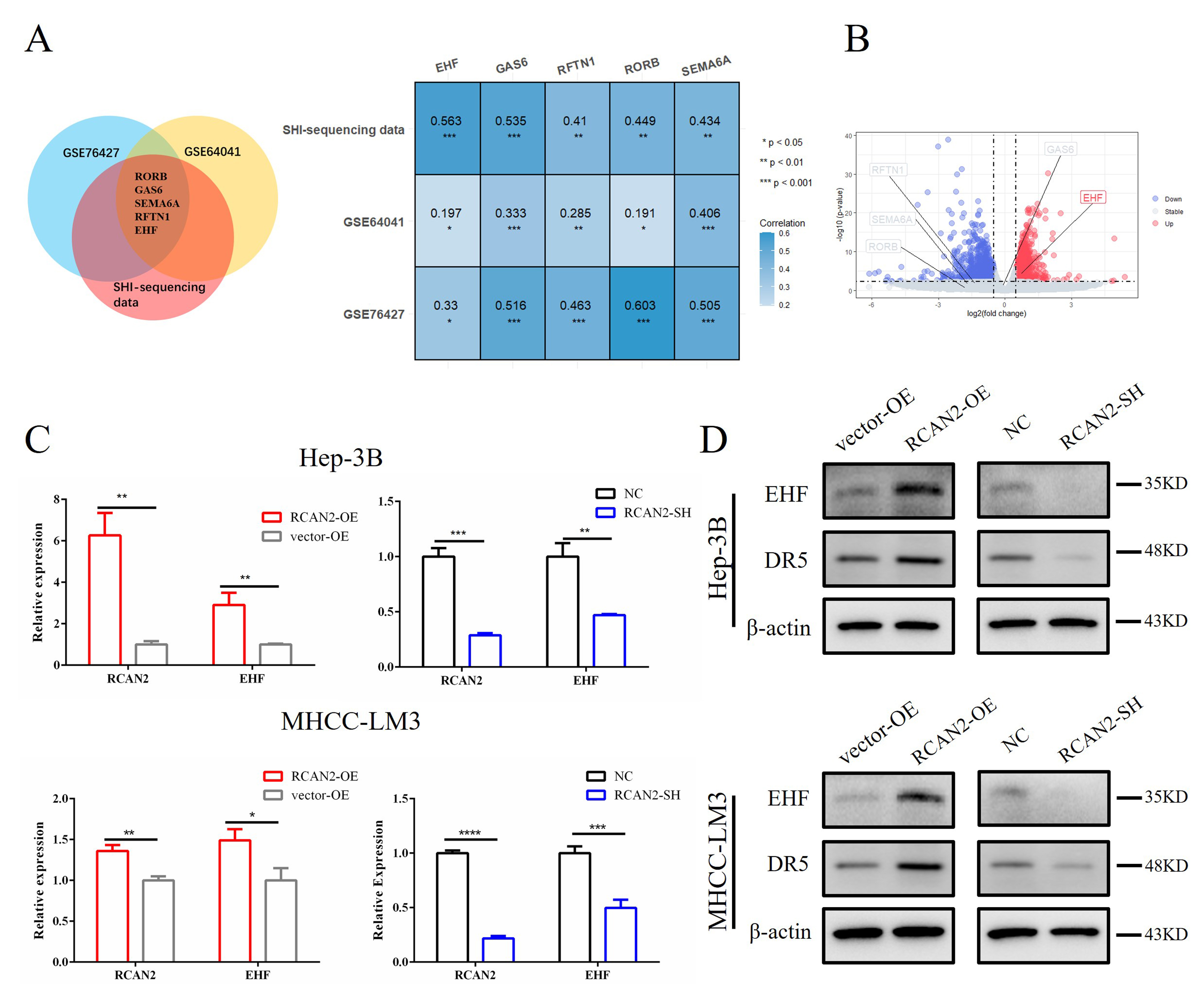

To explore the mechanism by which RCAN2 regulates apoptosis in HCC, we

screened genes related to RCAN2 in three independent databases (GSE76427, GSE6404

and SHI-sequencing data) using a threshold of p

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.Expression of EHF was positively correlated

with RCAN2 in three independent databases and validation in HCC cells

with altered RCAN2 expression. (A) Correlation of five genes that

collectively met the threshold in three independent databases (GSE64041, GSE76427

and SHI-sequencing data; *p

The relationship between five key genes and RCAN2 was validated in the MHCC-LM3 cell sequencing dataset. Compared with the RCAN2-SH group, the expression of EHF in the NC group was significantly upregulated, while the expression of the other four genes was not significantly different (Fig. 7B). Because of the positive correlation between RCAN2 and EHF in multiple independent databases, EHF was selected for subsequent mechanism verification.

We also detected the correlation in mRNA and protein expression between RCAN2 and EHF was examined in vitro. In transfected HEP-3B and MHCC-LM3 cells, the changes in EHF mRNA and protein expression mirrored those of RCAN2, as determined by qPCR and western blot (Fig. 7C,D). This result suggests that overexpression or knockdown of RCAN2 can upregulate or inhibit the expression of EHF (Fig. 7D), and corroborates a previous study that found EHF acts as an upstream transcription factor which regulates the expression of DR5 [28].

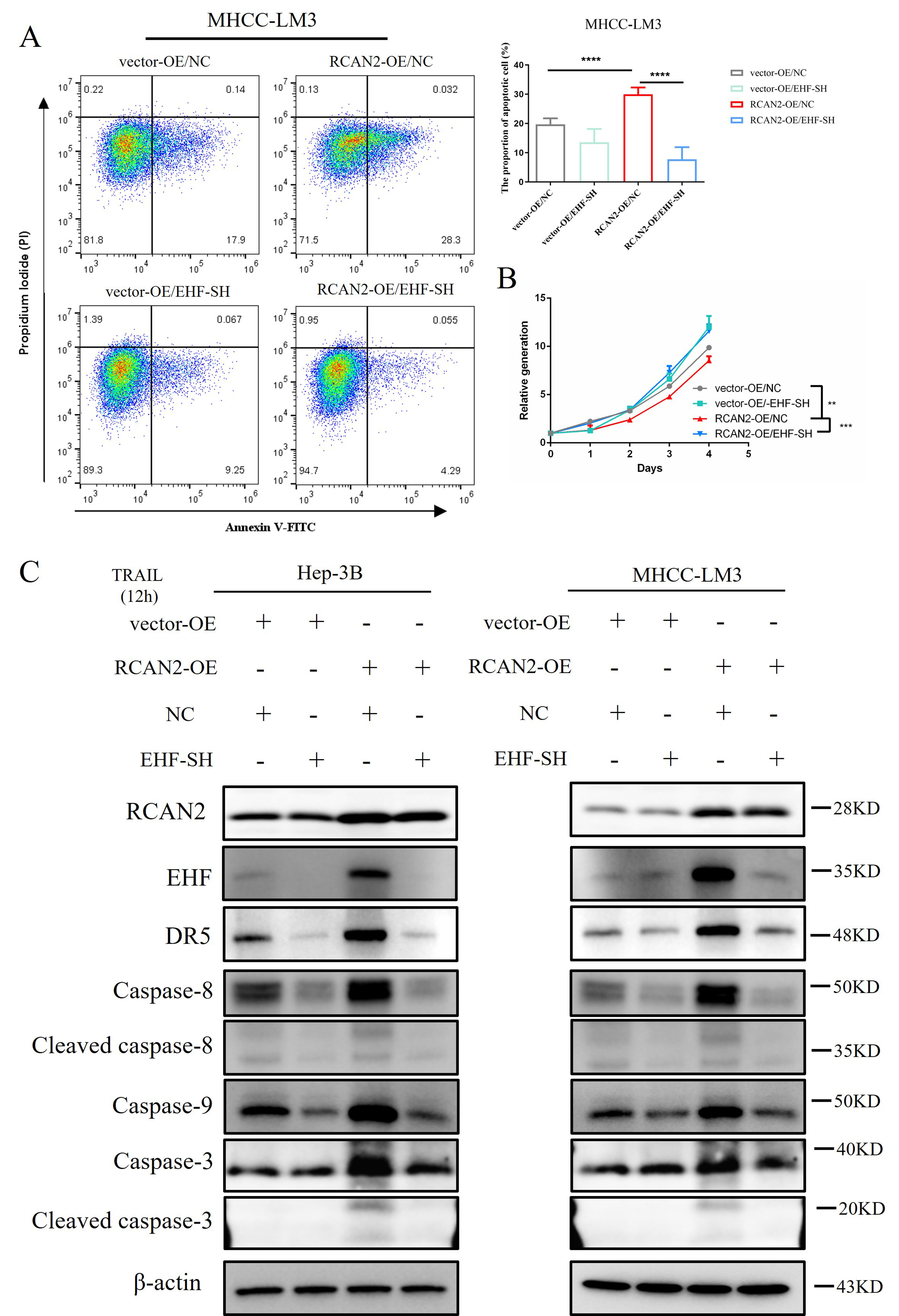

It is unclear RCAN2 promotes the apoptosis of HCC cells by regulating the expression of EHF. To address this, we transfected an EHF-SH plasmid into MHCC-LM3 cells with RCAN2-OE, as well as the corresponding control cells. Cell proliferation and apoptosis were measured by CCK-8 kit and image-flow cytometry assay, respectively. The proportion of apoptotic cells in the image-flow cytometry assay was reduced after the recovery of EHF expression (Fig. 8A). Moreover, the proliferation rate of HCC cells also increased after the recovery of EHF expression (Fig. 8B). At day 4, the cell proliferation rate of the RCAN2-OE/NC group was lower than that of the vector-OE/NC group (p = 0.004). When the expression of EHF was knocked down, the proliferation rate of cells improved significantly (RCAN2-OE/EHF-SH group vs. RCAN2-OE/NC group, p = 0.0003).

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.The proportion of apoptotic cells, cell proliferation,

DR5 protein expression and caspase-8/9/3 protein expressions in HCC

cells with altered RCAN2 expression, and with or without recovery of

EHF expression. (A) After 12 h treatment of transfected HCC cells with

recombinant human TRAIL protein, the proportion of apoptotic cells was

assessed by image-flow cytometry assay (****p

After 12 h treatment of HCC cells with recombinant TRAIL, the expression levels of caspase-8, cleaved caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-3 were evaluated to assess apoptosis. It showed that the protein expression of DR5, caspase-8, cleaved caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-3 were downregulated after the recovery of EHF expression (Fig. 8C). This result suggests that knockdown of EHF can reverse the effect of RCAN2 upregulation on the apoptosis of HCC cells, thereby restoring cell proliferation. Based on these preliminary observations, we propose that RCAN2 can promote extrinsic apoptosis of HCC cells by upregulating the expression of EHF and DR5, thus inducing apoptosis through the caspase-8/9/3 pathway.

Abnormal proliferation in hepatocytes is always accompanied by somatic mutations of some important anti-tumour genes such as TP53, CTNNB1 and so on [8, 9, 10]. These processes of gene mutation and inactivation are considered important characteristics in the development of HCC [7, 29]. The accumulation of mutations in tumours is associated with poor prognosis due to more malignant cellular behaviour [30, 31]. The cellular behaviour is frequently characterized by an augmented rate of proliferation or an enhanced invasive capacity, and clinically manifested by accelerated rates of tumour progression or distant metastasis. It finally results in the limited response to systemic therapy [32, 33]. TMB is one of the crucial metrics for assessing the mutational load in tumours and has been proven to be correlated with the efficacy of systemic therapy in many tumour types [11]. To improve the treatment of advance HCC, it is therefore important to explore the molecular mechanism that link TMB with prognosis.

Previous studies have shown that different levels of effector protein phosphorylation can lead to different phenotypes, including chemoresistance and proliferation, in many cancer types [34, 35, 36, 37]. Bioinformatics analyses conducted in the present study resulted in similar findings: Different tumour subgroups related to TMB show significant survival differences. Differences in the PI3K-Akt signalling pathway may be responsible for this effect on prognosis. Genes that regulate phosphorylation may therefore play an important role in determining the prognosis of different TMB subgroups in HCC.

Previous studies have shown that RCAN2 participates in phosphorylation by inhibiting the activation of calcineurin [13, 14]. In our study, RCAN2 was one of the significantly different genes between IC1 and IC2 clustered by TMB signature-related genes. And it was also identified as the genes related to overall survival in the TCGA-LIHC database. In addition, RCAN2 showed a negative correlation with TMB in the pan-cancer analysis, suggesting that inhibition of RCAN2 expression may be a common phenomenon in many cancer types with accumulation of somatic mutations. Thus, RCAN2 may be a key biomarker in determining the overall survival of cancer patients, and it is important for enhancing the HCC treatment efficacy to explore the underlying mechanism of RCAN2 influencing the prognosis of HCC.

However, the biological functions of RCAN2 appear to vary in different tumour types. In gastric carcinoma, RCAN2 stimulates cell growth and invasion by upregulating the phosphorylation of AKT and ERK [15]. Moreover, RCAN2 can suppress cell proliferation in KRAS-mutated colorectal cancer (CRC) by inhibiting the calcineurin-NFAT signalling pathway [16]. The present study found that high RCAN2 expression was associated with better overall survival in HCC. Furthermore, RCAN2 performed relevant biological functions by affecting apoptosis in vitro.

EHF is one of the ETS transcription factors that regulates expression of the downstream gene DR5 by binding to the ETS sequence in the promoter, thereby affecting tumour cell proliferation [28]. Through experiments involving the recovery of EHF expression, we demonstrated that RCAN2 regulated extrinsic apoptosis through the EHF/DR5 pathway. Although the specific mechanism for this is still unclear, calcineurin and oxidative phosphorylation may play important roles in the process. When HCC cells are stimulated by external apoptotic inducers, the apoptotic signalling can mediate activation of apoptotic proteins such as caspase8/9/3 through up-regulation of DR5, eventually leading to cell apoptosis.

A shortcoming of this study was that the specific model of molecular interaction

between RCAN2 and EHF remains unclear. In addition, the change

of NF

RCAN2 expression is a biomarker of prognosis in HCC and is negatively correlated with TMB. It has been demonstrated that RCAN2 regulated extrinsic apoptosis through EHF/DR5 pathway in our study. When HCC cells are stimulated by external apoptotic inducers, the apoptotic signalling can mediate activation of apoptotic proteins such as caspase8/9/3 through up-regulation of DR5, ultimately leading to cells apoptosis. This study provides a potential new target for the treatment of advanced HCC with high TMB.

HCC, Hepatocellular carcinoma; TP53, Tumour protein p53; CTNNB1, Catenin beta 1; TMB, Tumour mutational burden; TCGA-LIHC, The Cancer Genome Atlas-Liver hepatocellular carcinoma; qPCR, Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; IHC, immunohistochemistry; EHF, ETS homologous factor; IC, Integrated cluster; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; LGALS3, Galectin 3; CXCL1, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1; SLC22A1, Solute carrier family 22 member 1; CLEC3B, C-type lectin domain family 3 member B; OE, Overexpression of gene; vector-OE, plasmid with overexpression vector; SH, Knocking down of gene; NC, Negative control; CCK8, Cell counting kit-8; GSEA, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; DR5, Death receptor 5, also called TNFRSF10B, TNF receptor superfamily member 10b; EHF, ETS homologous factor; RCAN2, Regulator of calcineurin 2.

The externally validated datasets were generated from The Cancer Genome Atlas-Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA-LIHC) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) and Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo, ID: GSE76427 and GSE64041) [14]. The data generated and/or analyzed during the current study can be accessed and used after the consent of the corresponding author upon reasonable request by email.

SZ, MKH, and YJX designed the research and reviewed and revised the manuscript; MS and WLG revised the design of the research and the manuscript. YJX, ZCL and AK performed the data analysis and experiments and drafted the manuscript; YJX, HL, YH, YYL and JFW and ZFW generated the figures. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen university Cancer Center (No. 202011) and written informed consents from patients were waived due to the retrospective nature of our study. The animal study was approved by the Animal Care Review Committee of the Sun Yat-sen University (L025501202107011).

We appreciate Xuan-Jia Lin for helping to review the manuscript and give some advice on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Doctoral Project Initiation in Guangzhou First People’s Hospital [No. BA000000001246], Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou [No. 2024A04J4011], National Key Research and Development Program of China [No. 2023YFA0915703], National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 82272890, No. 82203126, and No. 82102985], and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [No. 2023TQ0390].

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.