1 Department of Nautical Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Naval Medical University, 200433 Shanghai, China

2 School of Pharmacy, Naval Medical University, 200433 Shanghai, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Previous studies have demonstrated a significant association between neuroinflammation and major depressive disorder (MDD). (6aS,10S,11aR,11bR,11cS)-10-methylamino-dodecahydro-3a,7a-diaza-benzo(de)anthracene-8-thione (MASM), a derivative of matrine, has recently been shown to display anti-inflammatory properties. However, its effects on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced depression and the underlying mechanisms remain unexplored. This study aimed to assess the effects of MASM on depressive-like behaviors induced by LPS and to investigate the potential mechanisms involved.

Following intraperitoneal injection of LPS (0.83 mg/kg), MASM was administered. Depressive-like behaviors were assessed through the forced swim test (FST) and tail suspension test (TST). To further explore the mechanisms, LPS-induced BV2 microglial cell models were established. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to quantify the expression of TNF-α and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), while immunoblotting was performed to assess heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), sirtuin 1 (SIRT-1), p62, and microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3-phosphatidylethanolamine conjugate (LC3-II) expression. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels were evaluated using flow cytometry.

MASM pretreatment markedly ameliorated acute depressive-like behaviors in LPS-treated mice and upregulated HO-1 expression in the hippocampus. In LPS-stimulated BV2 cells, MASM reduced the levels of proinflammatory markers TNF-α and HMGB1. Furthermore, MASM mitigated LPS-induced oxidative stress, as evidenced by increased ATP, HO-1, and SIRT-1 levels, along with decreased ROS levels. MASM also restored autophagic function, demonstrated by increased LC3-II expression and reduced p62 levels.

These findings suggests that MASM alleviates LPS-induced neuroinflammation and acute depressive-like behaviors, possibly by reducing oxidative stress and promoting autophagy.

Keywords

- MASM

- BV2 cell

- microglia

- neuroinflammation

- oxidative stress

- autophagy

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common mood disorder, primarily characterized by persistent low mood, a marked reduction in interest or pleasure in activities, and, in severe cases, may result in suicide [1]. MDD affects millions globally, imposing a substantial burden on both families and society, as well as negatively impacting public health and economic development. Although there have been significant advances in both pharmacological and psychological treatments, the response rate remains limited, with efficacy observed in only 60%–70% of patients [2]. Additionally, the delayed onset of therapeutic effects and adverse side effects, such as nausea, insomnia, and sexual dysfunction [3], limit the clinical utility of conventional antidepressant drugs. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop alternative therapies that are both effective and safe.

Substantial evidence has established a link between depression and chronic inflammation [4]. Overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines is crucial to the initiation and progression of depression [5, 6]. Elevated levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-

Matrine, an active alkaloid compound extracted from Sophora flavescens [14], has been employed in traditional Chinese medicine for its various pharmacological effects, including immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrotic properties [15, 16, 17]. Nonetheless, its clinical application is limited by its low therapeutic effectiveness. To address this limitation, various matrine derivatives have been developed, among which MASM [(6aS,10S,11aR,11bR,11cS)-10-methylamino-dodecahydro-3a,7a-diazabenzo [de] anthracene-8-thione] has demonstrated enhanced anti-inflammatory effects in vitro. Previous studies have underscored the anti-neuroinflammatory potential of MASM [18]. For example, MASM treatment has been shown to inhibit astrocyte reactivity and preserve astrocytic function in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [19]. Furthermore, Xu et al. [20] reported that MASM suppresses LPS-induced inflammation and functional maturation of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. However, the anti-inflammatory effects of MASM within the context of depression and microglial activation have not been investigated. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the antidepressant effects of MASM and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Initially, we established a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced mouse model to assess the effects of MASM on alleviating acute depressive-like behaviors and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) expression in vivo. Subsequently, we investigated the impact of MASM on oxidative stress and autophagy in vitro using LPS-treated microglial BV2 cells. Our findings suggest that MASM may attenuate the LPS-induced neuroinflammatory response and acute depressive-like behaviors by improving oxidative status and enhancing autophagic activity in microglia.

MASM (purity

Thirty male BALB/c mice, aged 7 weeks, were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center at Naval Medical University (Shanghai, China). The mice were housed in groups under standard laboratory conditions, maintained at a constant temperature of 22 °C, with 52% relative humidity, and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved in accordance with the guidelines issued by Naval Medical University.

After a 7-day acclimation period, the mice were randomly assigned to three groups: control group, LPS group, and LPS+MASM group. To induce an acute depressive-like behavior model, LPS (0.83 mg/kg) [21] was administered intraperitoneally at 19:00 on the experimental day. MASM (0.25 mg/kg) was given intraperitoneally 2 hours before the LPS injection. The control group received an intraperitoneal injection of saline. Behavioral assessments, including the tail suspension test (TST), forced swim test (FST), and open field test (OFT), were conducted at 19:00 on the day following LPS administration. After the behavioral tests, the mice were euthanized using tribromoethanol (0.2 mL/10 g), and their hippocampi were rapidly dissected and stored at –80 °C for subsequent analyses.

After 1 day of drug administration, all mice were given a 24-hour rest period. Subsequently, following weighing, behavioral tests were conducted during the dark phase between 19:00 and 22:00.

The Tail Suspension Test is a well-established method for assessing behavioral manifestations of despair and helplessness in murine models [21]. The test was performed using an automated TST device (MED-TSS-MS, MED Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA). Prior to each trial, the inner walls of the chambers were cleaned with 75% ethanol (C069156931, Nanjing Regent, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). The test duration was 6 minutes, consisting of a 1-minute adaptation period followed by a 5-minute testing period. Data were analyzed using Tail Suspension SOF-821 software (MED Associates Inc., St.). Consistent with previous studies, an immobility threshold was set at 0.75, with signals below this threshold considered indicative of immobility. The cumulative duration of immobility was recorded as the primary measure.

The Forced Swimming Test is widely used to evaluate depressive-like behavior in animals [22]. The FST detection system (SuperFst high-throughput FST system, Xinruan, Shanghai, China) analyzed the activity of mice through video recording and grayscale tracking. This system distinguishes between floating, swimming, and struggling behaviors and calculates the total floating time, which is considered as immobility time. Mice were gently placed in a water container filled with water at 25 °C to a depth of approximately 16–18 cm. The total recording time was 6 minutes, and the immobility time during the last 5 minutes was used for analysis.

The Open Field Test assesses autonomous activity and anxiety in animals [23]. The test was conducted in a square, opaque box measuring 42

The BV2 microglial cells were obtained from the China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC, Wuhan, Hubei, China), a certified and reputable cell bank. All cell lines were validated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and confirmed negative for mycoplasma. The cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator (Huachen High Pressuer Vesssel Group Cooperation, Jinan, Shandong, China). Subculturing was conducted at a 1:3 ratio, with only passages up to the sixth used for experiments. The cells were assigned to six groups: control, LPS (model), LPS+MASM (10 µM), LPS+MASM (20 µM), MASM (10 µM), and MASM (20 µM). For the ROS assays, an additional group (LPS+MASM 50 µM) was included. This group was added to evaluate the potential dose-dependent effects of MASM on ROS levels. Cells in all groups were stimulated for 6 hours based on preliminary findings indicating a significant increase in intracellular ROS levels at this time point. BV2 cells were seeded at a density of 1

The intracellular concentration of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was quantified using a commercially available DCFH-DA kit (Cat# S0033S, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Cells were incubated with the DCFH-DA working solution for 30 minutes. Following incubation, the culture medium was aspirated and cells were resuspended in PBS. Subsequently, flow cytometry (CytoFLEX, Beckman Coulter, Pasadena, CA, USA) was employed to measure fluorescence intensity at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm, which served as an indicator of ROS levels.

The levels of TNF-

The hippocampal tissue and BV2 cells were lysed in a lysis buffer and homogenized. Protein concentrations were measured using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (P0010, Beyotime). Equal protein amounts were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel (PG112, epizyem techonology, shanghai, china) for separation and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (FFP39, Beyotime) through electroblotting. After blocking with bovine serum albumin (BSA), the PVDF membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, including anti-HO-1 (1:1000), anti-p62 (1:1000), anti-

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS software version 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and data visualization was performed with GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., Boston, MA, USA). Statistical comparisons were made using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The results are expressed as the mean

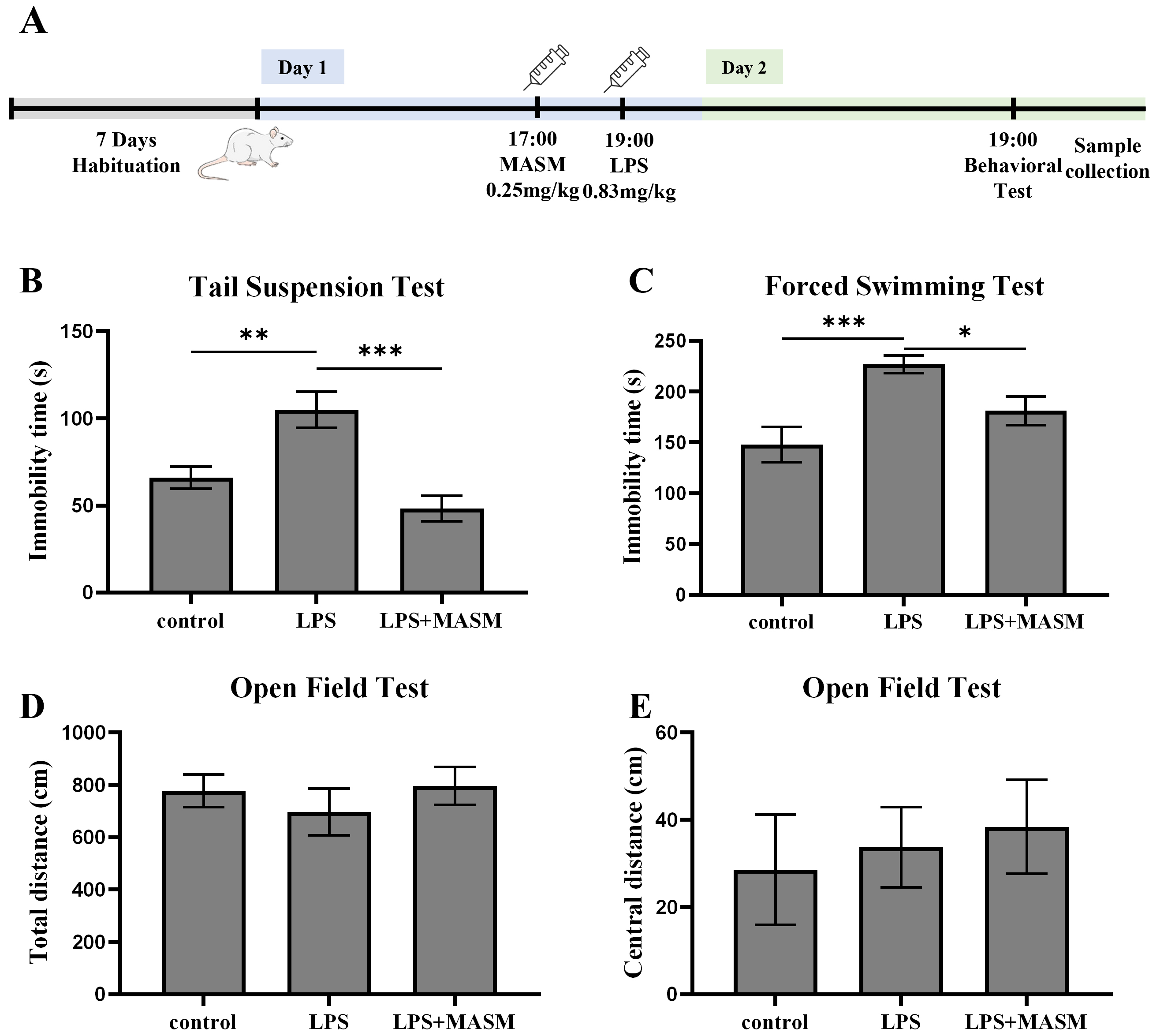

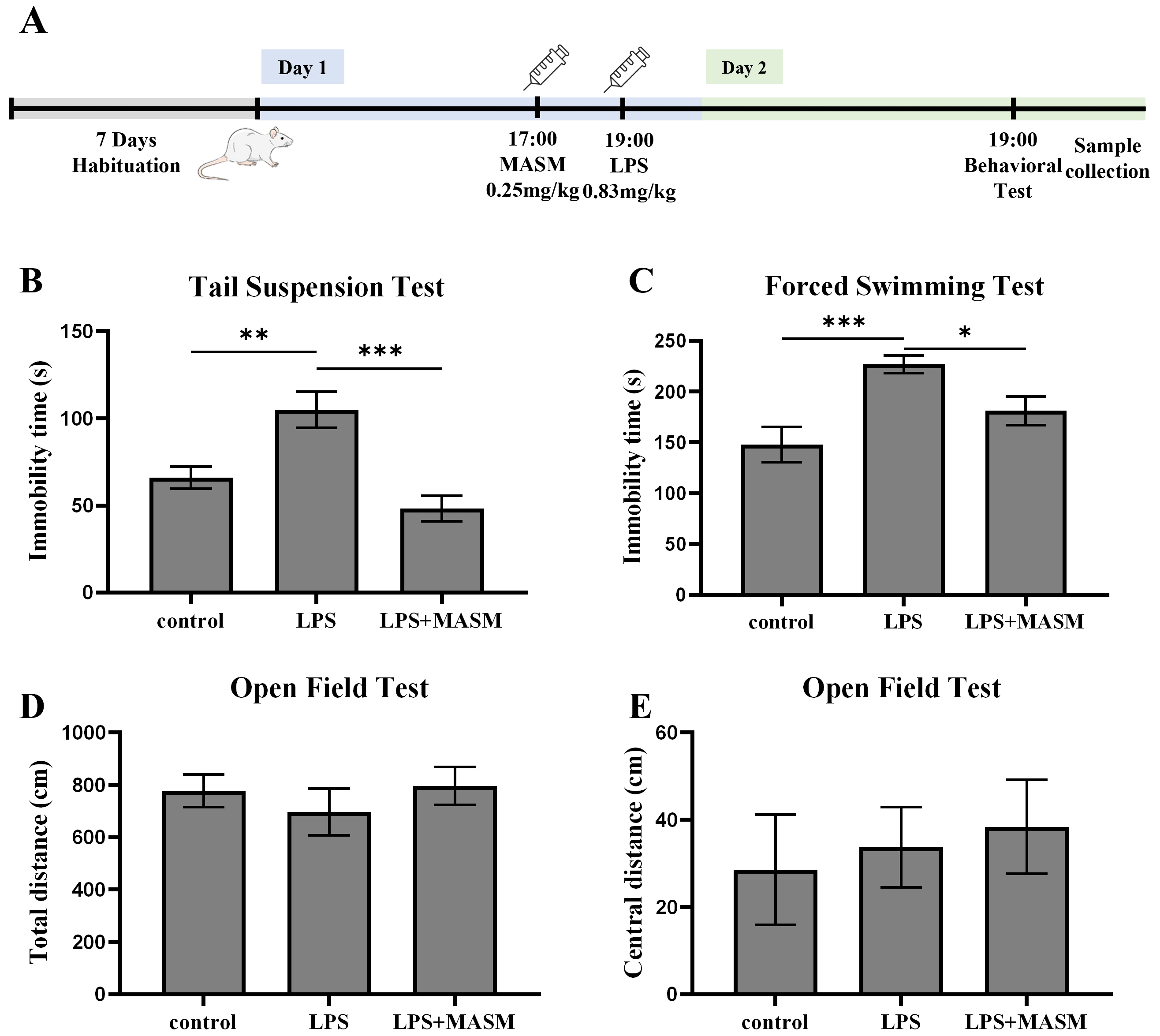

LPS is a widely recognized inflammatory agent commonly used to induce depressive-like behaviors in experimental models. To investigate the potential effects of MASM on LPS-induced depressive-like behaviors in mice, we performed behavioral assessments, including the TST, FST, and OFT, as outlined in Fig. 1A. In both the TST (Fig. 1B) and FST (Fig. 1C), mice treated with LPS showed a marked increase in immobility time compared with the control group, confirming the successful induction of depressive-like behaviors. Notably, MASM treatment significantly reduced the immobility time in LPS-exposed mice, suggesting mitigation of despair-associated behaviors. Next, locomotor activity was evaluated using the OFT (Fig. 1D,E). Although no statistically significant differences were observed in overall locomotor activity among the control, LPS, and LPS+MASM groups, MASM appeared to enhance central excitability in the LPS-treated mice. These findings imply that MASM alleviates LPS-induced depressive-like behaviors.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. MASM mitigates LPS-induced depressive-like behaviors. (A) Experimental procedure timeline. (B) Tail Suspension Test (TST) (one-way ANOVA followed by LSD’s multiple comparison tests, F (2,24) = 12.593, n = 9, p

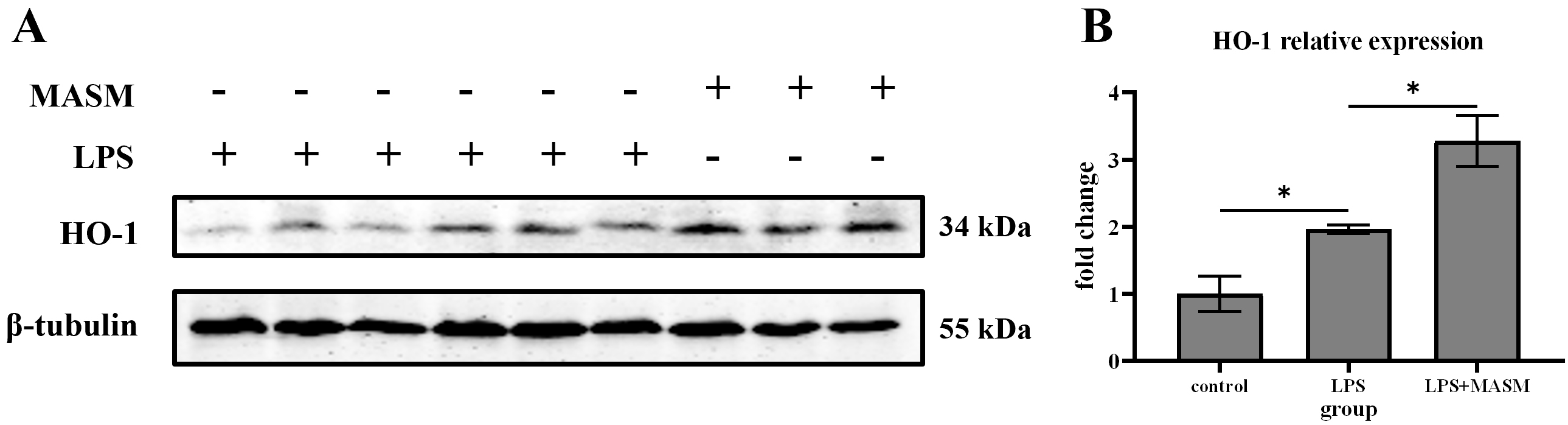

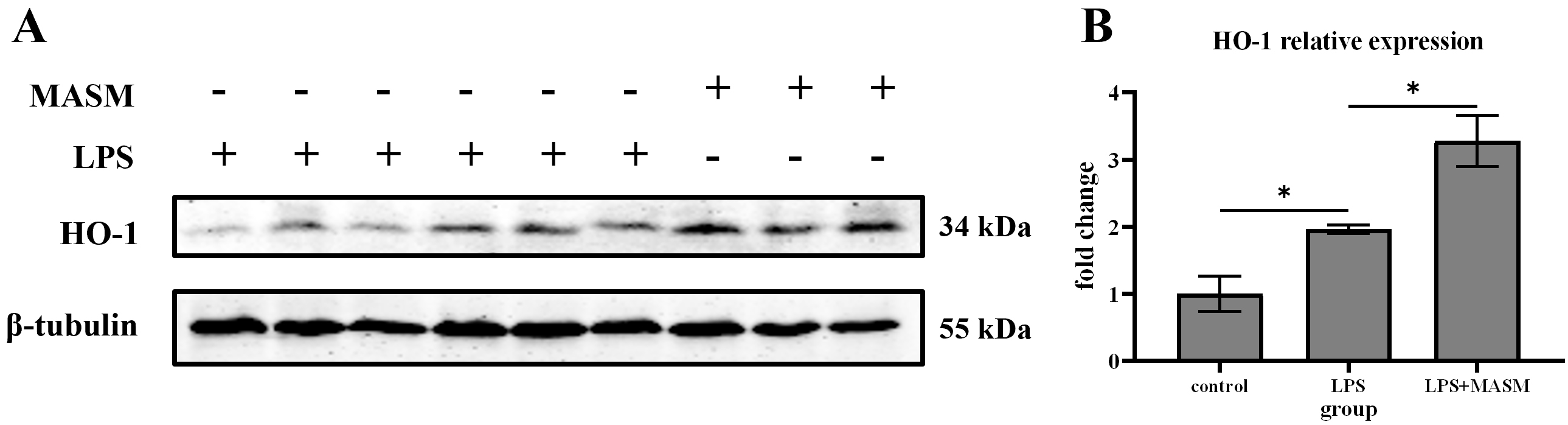

HO-1, an inducible heat shock protein, is well-known for its potent anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic properties. To investigate whether MASM’s effects on depressive-like behaviors are associated with changes in HO-1 expression, we measured HO-1 levels in the hippocampus following LPS administration. Immunoblotting analysis revealed that HO-1 expression was significantly elevated in LPS-treated mice compared with the normal control group. Notably, MASM treatment further increased HO-1 expression in the LPS-treated mice (Fig. 2), suggesting that HO-1 may contribute to the protective effects of MASM against LPS-induced depressive-like behaviors.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. MASM reduces LPS-induced effects on HO-1. (A) Representative blots of HO-1 expression. (B) Representative bar graph of HO-1 expression analysis. Data presented as mean

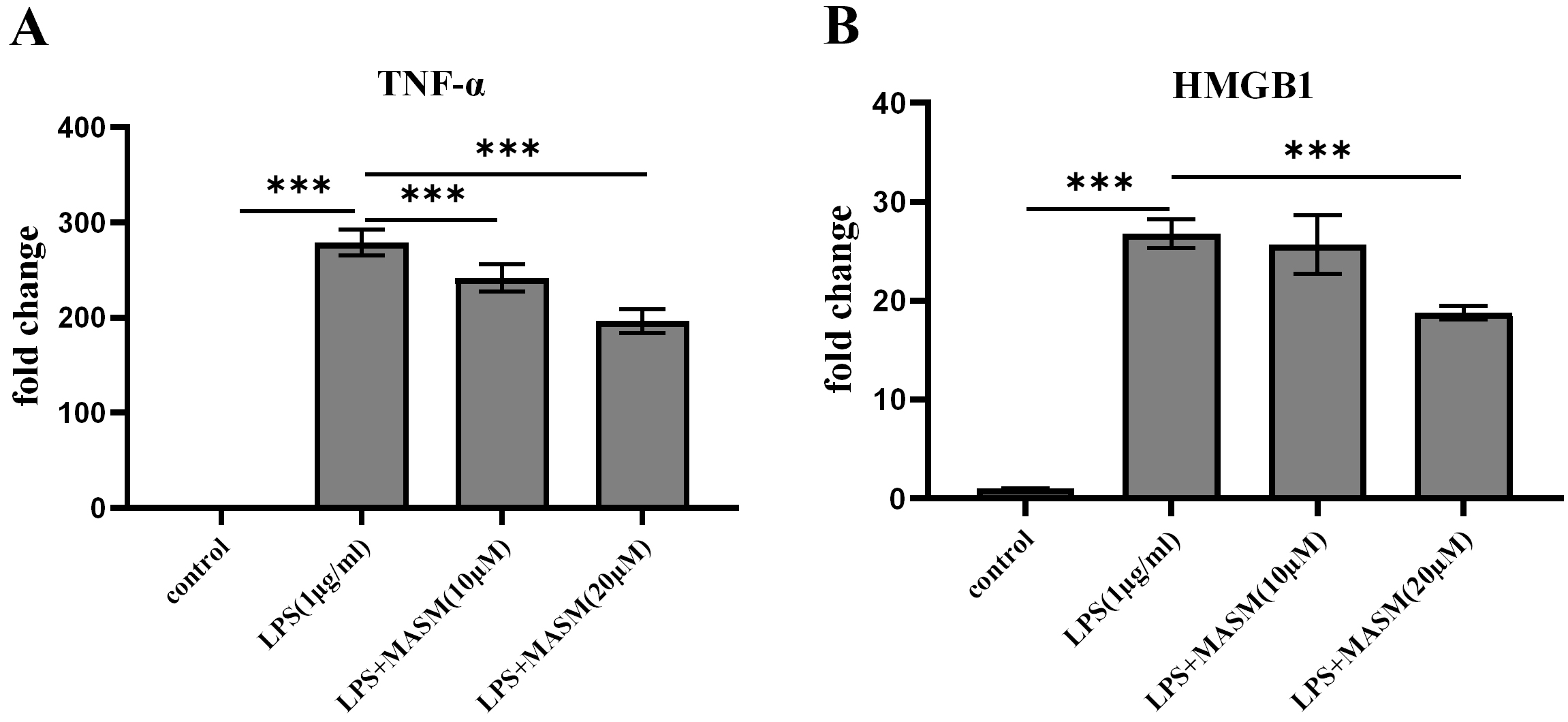

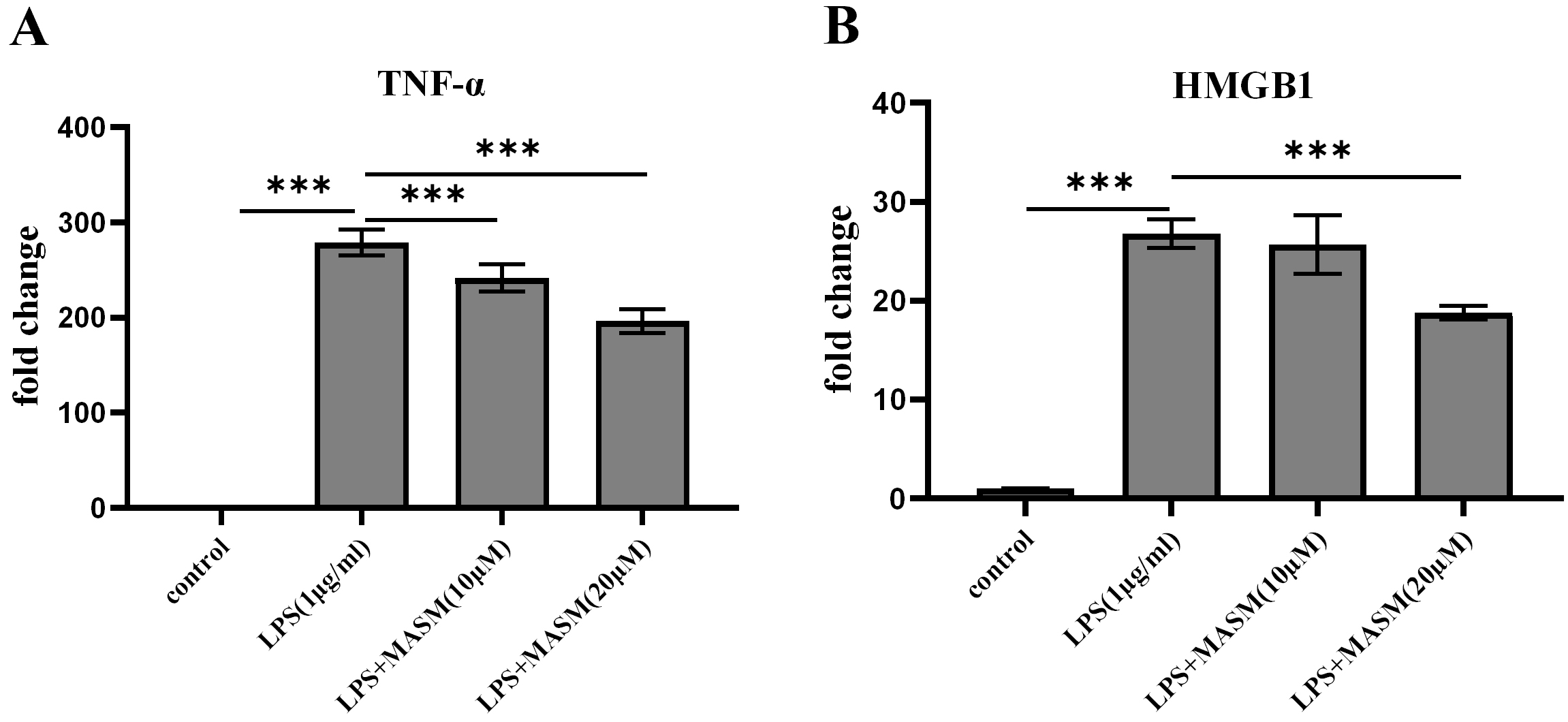

To investigate whether MASM modulates LPS-induced proinflammatory responses, BV2 microglial cells were pretreated with either vehicle (1% DMSO, ST038-100ml, Beyotime) or MASM at concentrations of 10 µM and 20 µM for 24 hours, followed by stimulation with LPS (1 µg/mL) or PBS for an additional 24 hours. We then evaluated the effects of varying MASM concentrations on the levels of proinflammatory markers TNF-

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. MASM lowers LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokine levels in BV2 cells. (A) Level of TNF-

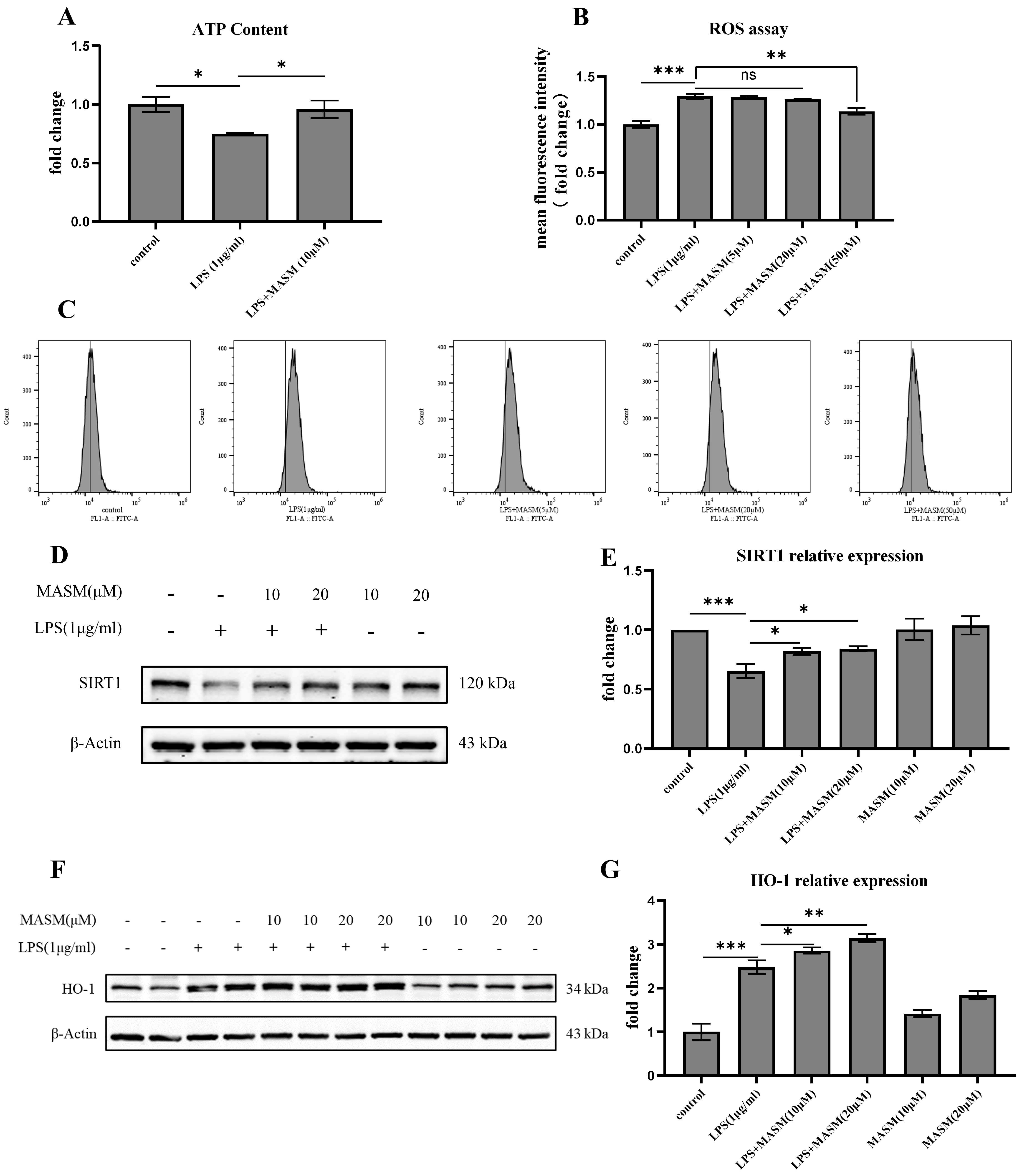

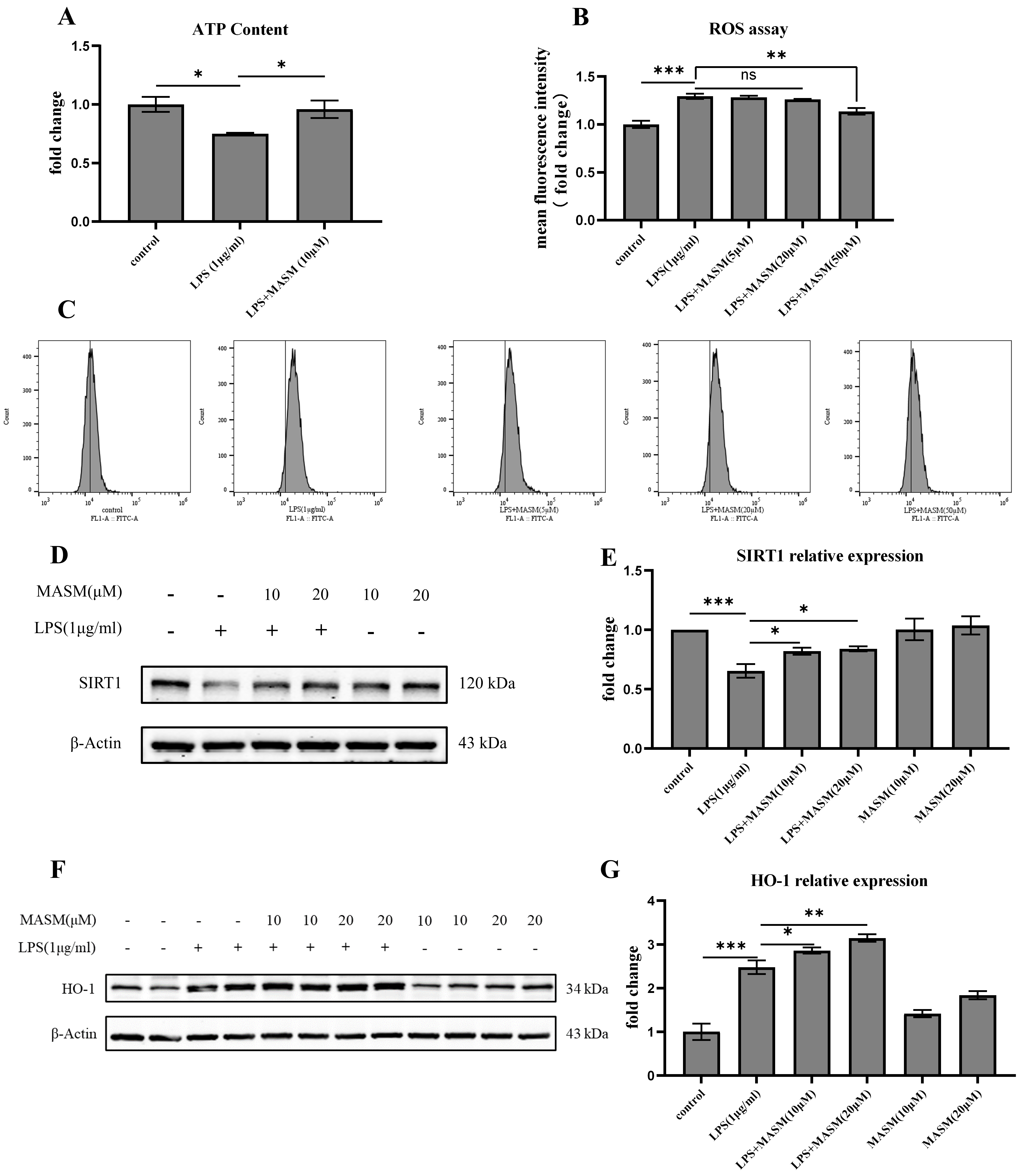

To further investigate the potential antioxidative effects of MASM, we measured and analyzed levels of ATP, ROS, deacetylase SIRT-1, and HO-1 in BV2 cells. LPS (1 µg/mL) treatment led to a significant reduction in ATP levels and an increase in ROS production, indicating oxidative stress in the cells (Fig. 4A–C). MASM treatment at 10 µM effectively reversed the LPS-induced ATP reduction, while MASM at 50 µM significantly decreased ROS levels. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 4D–G, LPS (1 µg/mL) stimulation resulted in a notable decrease in SIRT-1 levels and an increase in HO-1 expression, both of which were ameliorated by MASM treatment at 10 or 20 µM. These findings suggest that MASM may alleviate oxidative stress in microglia induced by LPS.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. MASM reduces LPS-Induced oxidative stress in BV2 cells. (A) Relative concentration of intracellular ATP in BV2 cells treated with MASM (one-way ANOVA followed by LSD’s multiple comparison tests, F(2,6) = 5.685, n = 3, p = 0.041; Control vs LPS, p = 0.020; LPS vs LPS+MASM (10 µM), p = 0.039). (B,C) Flow cytometry analysis of intracellular ROS production in BV2 cells treated with MASM (one-way ANOVA followed by LSD’s multiple comparison tests, F(4,14) = 19.349, n = 3–4, p

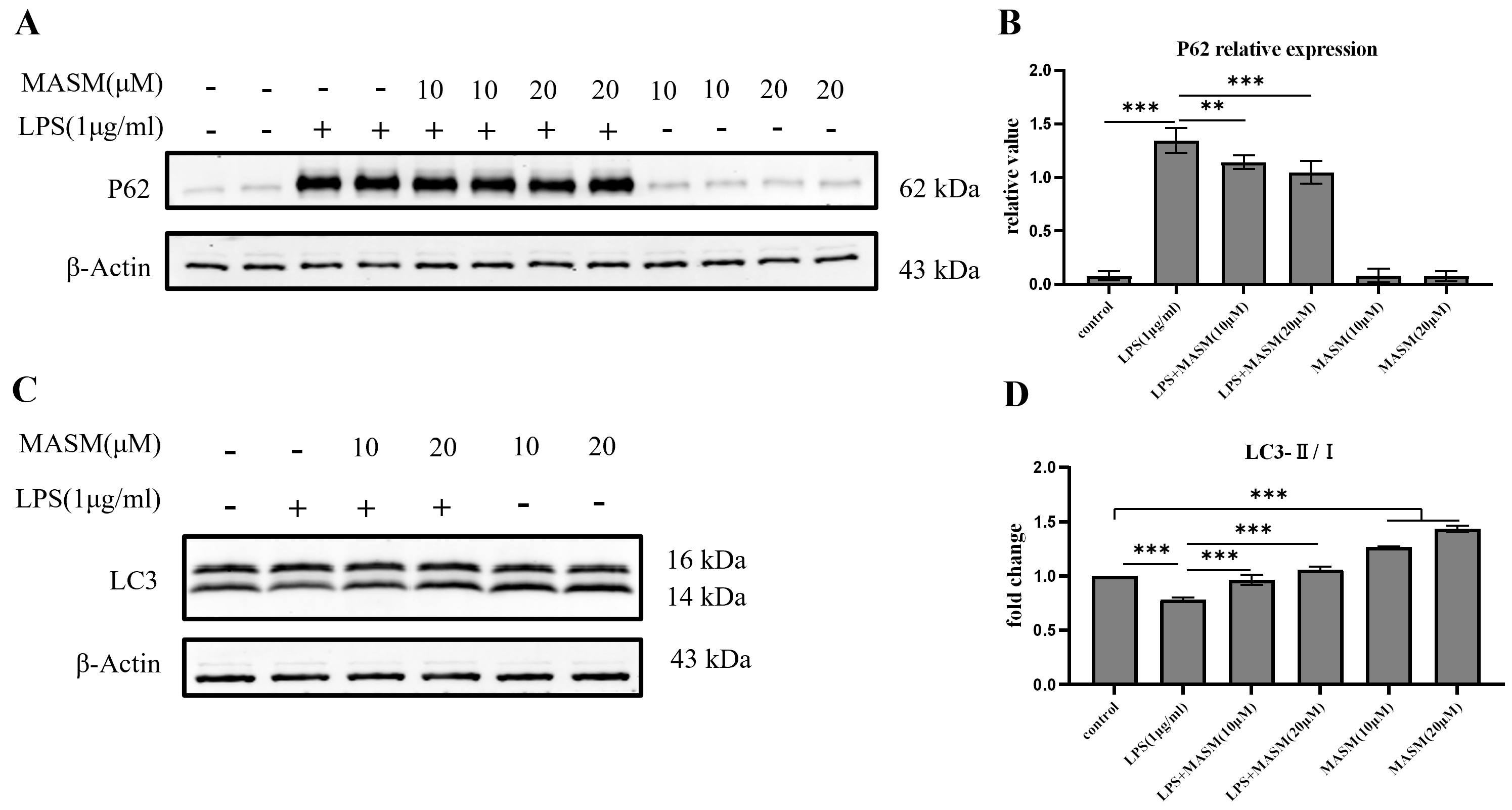

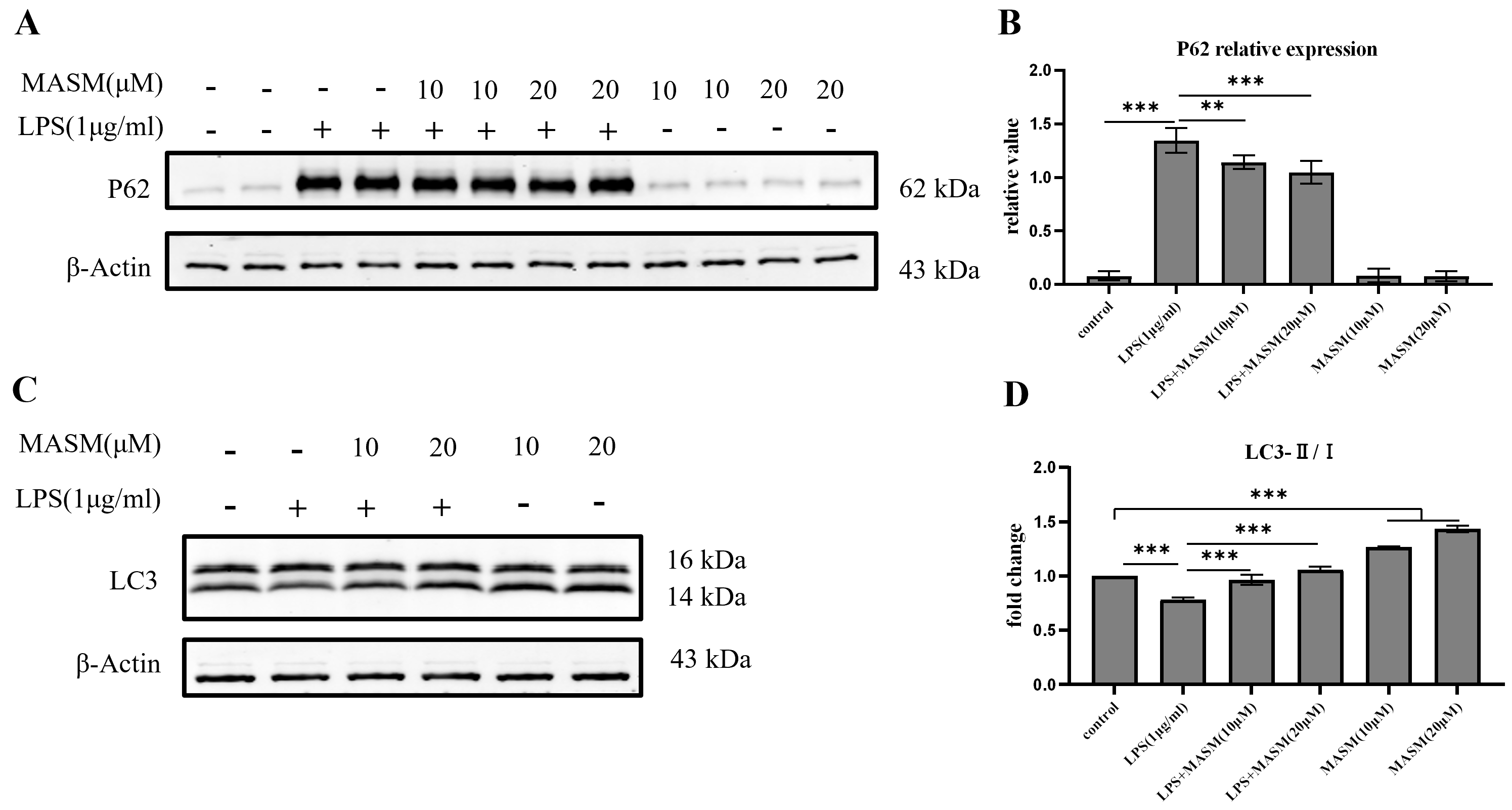

Autophagy plays a crucial role in regulating microglial inflammation. However, it remains unclear whether MASM modulates LPS-induced microglial inflammation through autophagic mechanisms. To explore this, we analyzed the expression of the LC3 and p62, key markers of autophagic activity, using western blotting. Following stimulation with LPS (1 µg/mL), BV2 cells demonstrated a significant reduction in the LC3-II/I ratio and an increase in p62 expression, indicating disrupted autophagic activity. In contrast, pretreatment with MASM at 10 or 20 µM significantly elevated the LC3-II/I ratio and reduced p62 levels (Fig. 5A–D), suggesting a restoration of autophagic function. Under normal culture conditions, MASM treatment significantly increased LC3-II/I expression in BV2 cells, suggesting a potential role of MASM in promoting autophagic flux (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. MASM enhances autophagic flux in BV2 cells. (A) Representative blots showing p62 expression. (B) Representative bar graph of p62 expression analysis (one-way ANOVA followed by LSD’s multiple comparison tests, F(5,18) = 240.792, n = 4, p

The anti-inflammatory properties of MASM in peripheral inflammatory diseases have been extensively researched. Recent research underscores the critical role of neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of depressive disorders. In this study, we investigated the effects of MASM on LPS-induced neuroinflammation and explored the underlying mechanisms involved. First, MASM significantly attenuated LPS-induced depressive-like behaviors by upregulating HO-1 expression. Second, MASM alleviated redox signaling changes, such as alterations in ATP, ROS, HO-1, and SIRT-1 levels, following LPS treatment. Additionally, MASM restored LPS-induced autophagy dysfunction. Collectively, these findings suggest that MASM can prevent neuroinflammation and alleviate depressive-like behaviors by modulating oxidative stress and autophagy.

Previous studies have demonstrated that intraperitoneal LPS administration effectively models neuroinflammation in animals. LPS treatment triggers a central inflammatory response characterized by elevated production of proinflammatory cytokines, microglial activation, and ROS generation, which can lead to depressive-like behaviors [24, 25]. In line with previous findings, our results demonstrate that LPS-induced neuroinflammation results in depressive-like behaviors, as evidenced by increased immobility in the TST and FST. Although no significant differences were observed in OFT between LPS-treated mice and the control group, indicating that mobility dysfunction or anxiety-like behavior in the model mice were not observed. Notably, MASM treatment significantly reduced LPS-induced depressive behaviors in these mice.

It is widely recognized that proinflammatory cytokines contribute to depression, as elevated cytokine levels have been observed in MDD patients [26]. Previous work from our group demonstrated that HMGB1 activates the kynurenine pathway in microglia, disrupting neurotransmitters and triggering depressive-like behaviors. Matrine, a compound with known anti-HMGB1 effects, also exhibits anti-inflammatory properties [27, 28]. In this study, we measured two representative cytokines, HMGB1 and TNF-

HO-1 is a well-known modulator of inflammation, involved in regulating the production of proinflammatory mediators and inhibiting the overproduction of M1 phenotype molecules [30]. In our study, compared with the control group, the LPS-treated group exhibited a significant increase in HO-1 expression, consistent with previous experimental findings [31]. This elevation in HO-1 levels is attributed to its protective role as an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory protein [32, 33]. Our in vivo experiments demonstrated that MASM promotes HO-1 expression, contributing to its antidepressant effects. Therefore, we established a neuroinflammation model in vitro to further investigate the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of MASM.

Additionally, several studies have shown that MDD is accompanied by decreased antioxidant and increased ROS status [34]. Both preclinical and clinical evidence indicate that antidepressants can reduce oxidative stress by scavenging ROS and inhibiting oxidative pathways [35]. HO-1 is widely recognized as a key player in redox-regulated gene expression, responding to agents that generate ROS. In our study, MASM pretreatment significantly reduced oxidative stress in LPS-treated BV2 cells, as evidenced by decreased ROS and ATP levels. Moreover, SIRT-1—an nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide+ (NAD+)-dependent protein deacetylase involved in energy metabolism, stress response, inflammation, and redox homeostasis [36, 37]—was upregulated by MASM compared with LPS-treated cells.

Autophagy dysfunction is a major contributor to oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. LC3-II, a marker of autophagic activity, localizes to autophagic membranes, while p62, an autophagic substrate, monitors autophagic turnover [38]. Our results showed that MASM increased LC3-II expression and decreased p62 levels, indicating a restoration of LPS-induced autophagic flux in BV2 microglial cells. Similarly, MASM reportedly exerts anticancer effects by promoting autophagy and inhibiting oxidative stress [39]. Our findings reveal that MASM plays a critical role in regulating redox homeostasis and autophagy in the context of depression.

Despite these promising findings, there are limitations to our research. Future studies should explore the protective effects of MASM through inhibition of HO-1, using HO-1 inhibitors or gene silencing approaches. Additionally, the role of transcription factor Nrf-2 in MASM-mediated HO-1 upregulation should be investigated to better understand the underlying mechanisms. The present study provides an initial exploration of the autophagy-enhancing effects of MASA, concentrating exclusively on changes in cytoplasmic autophagic flux. The subcellular localization of autophagic processes has not yet been examined in detail. In future studies, we intend to focus on selective autophagy pathways, such as mitophagy, guided by findings from transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Although MASM demonstrates strong anti-inflammatory effects and offers the advantages typical of natural products, such as enhanced bioavailability and low toxicity, it shows significant potential for clinical translation, particularly for patients with high-inflammatory depression. However, we did not explore the optimal effective dosage in vivo or investigate further molecular mechanisms. Therefore, future studies are required to validate MASM’s clinical applicability through additional experiments, including dosage optimization and mechanistic studies, such as examining the causal relationship between oxidative stress and autophagy.

In summary, this study revealed for the first time that MASM significantly alleviates acute depressive-like behaviors, decreases oxidative stress, and promotes autophagy in both an LPS-induced acute depression model and LPS-treated BV2 cells. Furthermore, MASM inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory responses by regulating the expression of HO-1 and SIRT-1. Due to its demonstrated effectiveness and safety, MASM shows potential as a novel therapeutic approach for treating inflammation-related neurological disorders, including MDD.

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

CRL and ZYX conducted the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. LNS, LLW, WFZ, YJL performed the research. LNS and JZ analyzed the data and draw the figures. YXW designed the study and secure funding. YW and YXW conceived the idea and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Naval Medical University. The procedures complied with the Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals of China (2018/3/10).

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Professor Qingjie Zhao from the Department of Pharmacy at Naval Medical University for generously providing the drugs used in this research.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771301).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.