1 Beijing Key Laboratory of Mental Disorders, National Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders & National Center for Mental Disorders, Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University, 100088 Beijing, China

2 Department of Psychiatry, The Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, 510370 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

3 Advanced Innovation Center for Human Brain Protection, Capital Medical University, 100088 Beijing, China

4 Peking University Huilongguan Clinical Medical School, Beijing Huilongguan Hospital, 100096 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

This study investigated the association between brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene polymorphisms and antidepressant response in patients with first-episode late-life depression (LLD).

A total of 72 patients with first-episode LLD were recruited and 57 completed an 8-week course of antidepressant treatment. Participants were assessed at baseline and post-treatment using the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17) and the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS). Serum BDNF levels were measured via Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and BDNF gene polymorphisms were genotyped using the Agena® MassARRAY system.

After 8 weeks, 17 of the 57 patients with LLD showed effective treatment response (effective group), while 40 were classified as ineffective. Significant post-treatment improvements were observed across the cohort in HAMD-17 and RBANS scores, and serum BDNF levels compared with baseline (p < 0.05). However, the effective and ineffective groups did not have significantly different RBANS scores or serum BDNF levels (p > 0.05). Binary logistic regression identified male sex (OR = 10.094, p = 0.007) and BDNF gene polymorphism (OR = 6.559, p = 0.003) as predictors of treatment efficacy.

Antidepressant treatment for 8 weeks altered serum BDNF levels in patients with LLD, with male patients carrying the Val/Val genotype potentially responded better to conventional antidepressants. The small sample size may limit the generalizability of these findings.

The study was registered at https://www.chictr.org.cn (registration number: ChiCTR1900024445).

Keywords

- antidepressants

- depression

- mood disorders

1. After 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment, Han Chinese patients with first-episode LLD exhibited significant improvements in depressive symptoms, increased serum BDNF levels, and enhanced cognitive function.

2. This study found no significant correlation between changes in depressive symptoms and alterations in serum BDNF levels or RBANS scores.

3. Male patients with LLD who possess the Val/Val genotype potentially respond better to conventional antidepressant therapy.

Late-life depression (LLD), affecting individuals aged 60 years and older, is prevalent in approximately 10–15% of community-dwelling older people [1, 2]. This prevalence rate increases in those with concomitant physical conditions, leading to diminished quality of life, impaired social functioning, and a heavier burden on caregivers [3, 4]. Apart from typical depressive symptoms, it often manifests with cognitive impairments, severely affecting treatment efficacy, social functioning, and overall quality of life. Besides typical depressive symptoms, cognitive impairments are common in LLD, severely impacting treatment outcomes, social functioning, and overall quality of life. The prognosis for LLD is worse than that for younger adults [5, 6]. Follow-up studies indicate that 44% of patients with LLD experience a fluctuating course of remission and relapse, 32% progress to chronic depression, and only 23% achieve favorable outcomes [7]. While continuation of antidepressant therapy has similar efficacy in older and younger adults [8], over half of the patients with LLD in remission relapse, primarily within 2 years [9]. Consequently, identifying objective markers for treatment response and prognosis in older patients is critical to guiding more effective interventions.

Emerging research suggests that alterations in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) are associated with depression onset [10, 11]. BDNF, a critical neurotrophic factor in the brain, supports neuron survival, differentiation, and growth. It plays a protective role, promoting neuronal repair and regeneration after injury [12]. The BDNF gene, located on the short arm (p13 region) of chromosome 11, includes several polymorphic sites, with the G196A polymorphism drawing particular attention [13]. This polymorphism occurs within a functional coding region, where a guanine (G) nucleotide is replaced by adenine (A). This substitution changes the BDNF precursor peptide, where valine (Val) is replaced by methionine (Met) at position 66, resulting in the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism [14, 15]. Although this substitution does not alter the function of mature BDNF protein, it disrupts the intracellular processing and secretion of BDNF precursors. The presence of the Met allele interferes with normal maturation and secretion of BDNF, potentially influencing the onset, progression, and outcome of depressive disorders [16, 17].

The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism is associated with brain structure and mood disorders [18, 19]. Research suggests that the Met allele increases vulnerability to dysfunctions in the uncinate fasciculus, a neural tract involved in negative emotional processing, memory deficits, and self-awareness issues [20]. Aguilera et al. [21] found that individuals with the Val66Met polymorphism are more susceptible to depression, with Met allele carriers experiencing depressive episodes at an early age than those with the Val/Val genotype. Moreover, the Met allele has been associated with a higher risk of suicide in female patients, indicating its potential role as a predisposing factor for depression [22, 23]. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism is linked to antidepressant efficacy [24, 25, 26]. Studies, including those by Alexopoulos et al. [24], reported that older patients with the Met allele showed improved therapeutic outcomes after 12 weeks of treatment with escitalopram at 10 mg/day compared to those with other genotypes. Another study found an 82% higher remission rate in Met allele carriers after 6 months of antidepressant treatment than in Val/Val carriers [25]. A meta-analysis of Asian populations similarly concluded that Val/Met carriers responded better to antidepressants than Val/Val carriers [26]. In contrast, a prior study within the Caucasian population did not identify a significant association between the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and remission rates [27]. Thus, racial factors may need to be considered when addressing this issue.

People with major depressive disorder (MDD) have lower peripheral and central BDNF levels compared to non-depressed individuals [28]. Moreover, increased serum BDNF levels following antidepressant therapy correlate with symptom improvement [29]. Elevated BDNF levels are observed in responders and those who achieve remission, while levels remain stable in non-responders [30]. However, the relationship between serum BDNF levels and antidepressant efficacy in LLD remains contentious, potentially due to genetic polymorphisms across different populations [31]. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism affects the presentation, progression, and prognosis of depression [32]. Serum BDNF levels were hypothesized to be associated with antidepressant efficacy in patients with LLD, and the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism influences this response. An open, prospective trial was conducted to verify this hypothesis by assessing the post-treatment changes in BDNF levels in patients with first-episode LLD. The association between the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and the efficacy and cognitive impact of antidepressant treatment in patients with LLD after 8 weeks was aimed to be determined.

Patients were recruited from Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China, between April 2020 and August 2022. The inclusion criteria were: first-episode patients diagnosed with depressive episodes, following the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5); age of onset

All participants underwent clinical assessments and neurocognitive tests at baseline and after 8 weeks of treatment. As per the Chinese guidelines for the prevention and treatment of depressive disorders, treatment involved either escitalopram (5–15 mg/day, H. Lundbeck A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark) or sertraline (25–150 mg/day, Pfizer Inc., New York City, NY, USA), with dosages within the safe and effective range [35]. Patients experiencing severe sleep disturbances, anxiety, or agitation may receive short-term treatment with benzodiazepines. Throughout the 8-week treatment period, none of the patients underwent physical therapies such as electroconvulsive therapy or transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy.

Treatment efficacy is frequently assessed clinically by response (a

Neurocognitive function was assessed using the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) [37], which includes 12 tasks covering five cognitive domains: (a) Immediate Memory, including verbal learning and story memory. (b) Visuospatial/Constructional, involving figure copy and line orientation tasks. (c) Language, with picture naming and semantic fluency tasks. (d) Attention, comprising digit span and coding tasks. (e) Delayed Memory, encompassing verbal (recall and recognition), story, and visual memory tasks. The MMSE was employed for inclusion and exclusion criteria. The RBANS total score, derived from summing the five index scores, typically ranges from 90 to 109, with lower scores indicating diminished cognitive function. A prior study indicated that except for the Delayed Memory Index, the proportion of variance accounted for by age is too small to merit clinical adjustment of index scores in a nondemented geriatric sample [38]. In addition, the RBANS is simple to administer and normally takes approximately 20 minutes. In short, the application of RBANS to assess the cognitive function of patients with LLD is feasible, and aligns with the findings of prior studies [35, 39].

Two professional psychiatrists assessed all scales. Before the start of the research, all participants underwent rigorous and comprehensive consistency training. The entire process adhered strictly to the experimental protocol. Researchers meticulously completed the case report forms, maintained accurate records, and refrained from making unauthorized changes. After each visit and evaluation, original data were promptly verified and reviewed to address any issues, ensuring the experimental data’s authenticity, accuracy, and completeness.

Serum BDNF concentrations were measured before and after 8 weeks of treatment to evaluate BDNF levels in patients. Eligible participants who provided informed consent had 4 mL of venous blood collected from the forearm: 2 mL in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 2 mL in heparin, and were immediately placed on ice. Blood for BDNF assays was collected in serum separator tubes, allowed to clot at room temperature for 1 h, and then subjected to platelet activation for 1 h at 4 °C. The blood was centrifuged at 2000 g for 20 min, and the serum was separated and stored at –80 °C until analysis. Serum BDNF levels were measured using an Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) with a BDNF sandwich ELISA kit (DuoSet; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). All the samples were tested in duplicate. The procedure involved diluting capture antibodies (provided by the manufacturer) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (DuoSet; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), adding them to each well, and incubating overnight at room temperature. Plates were washed four times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, blocked with 1% ovine Serum Albumin (BSA) (DuoSet; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 1 hour, and washed again four times with PBS and 0.05% Tween 20. Detection antibodies (provided by the manufacturer) were added and incubated for 2 hours. After washing, the plates were incubated with streptavidin-HRP (DuoSet) and developed with TMB chromogenic substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories [KPL], Milford, MA, USA) for 15 minutes in the dark. The reaction was stopped with 1 M phosphoric acid, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a plate reader (Infinite M1000 PRO; Tecan Trading AG, Männedorf, Zurich, Switzerland).

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral whole blood samples using the G-DEX™ II Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Intron Biotechnology, Seoul, South Korea), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Primer extension products generated from genomic DNA were assessed using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry-based chip technology to analyze the BDNF (Val66Met) gene polymorphism. Data were processed with MassArray Typer 4.1 software (Agena Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), facilitating SNP typing by evaluating molecular size differences. The upstream primer for BDNF Val66Met polymorphism is 5′-ACTCTGGAGACGTGATGG-3′, and the downstream primer is 5′-ACTACTGAGCATCACCCTGGA-3′. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 62 °C for 30 seconds, extension at 72 °C for 30 seconds, a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 minutes, and maintenance at 4 °C. PCR products were digested with the restriction enzyme Eco72I (New England Biolabs [NEB], Ipswich, MA, USA) at 37 °C, and gel electrophoresis was used to detect the 196G (Val, 99- and 72-bp fragments) and 196A (Met, 171-bp fragment) alleles. Based on the digestion pattern, genotypes were classified as Val/Val, Val/Met, or Met/Met.

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22.0 (IBM SPSS Corp.; Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of data distribution was assessed via skewness and kurtosis. Continuous variables such as age and disease duration were presented as mean

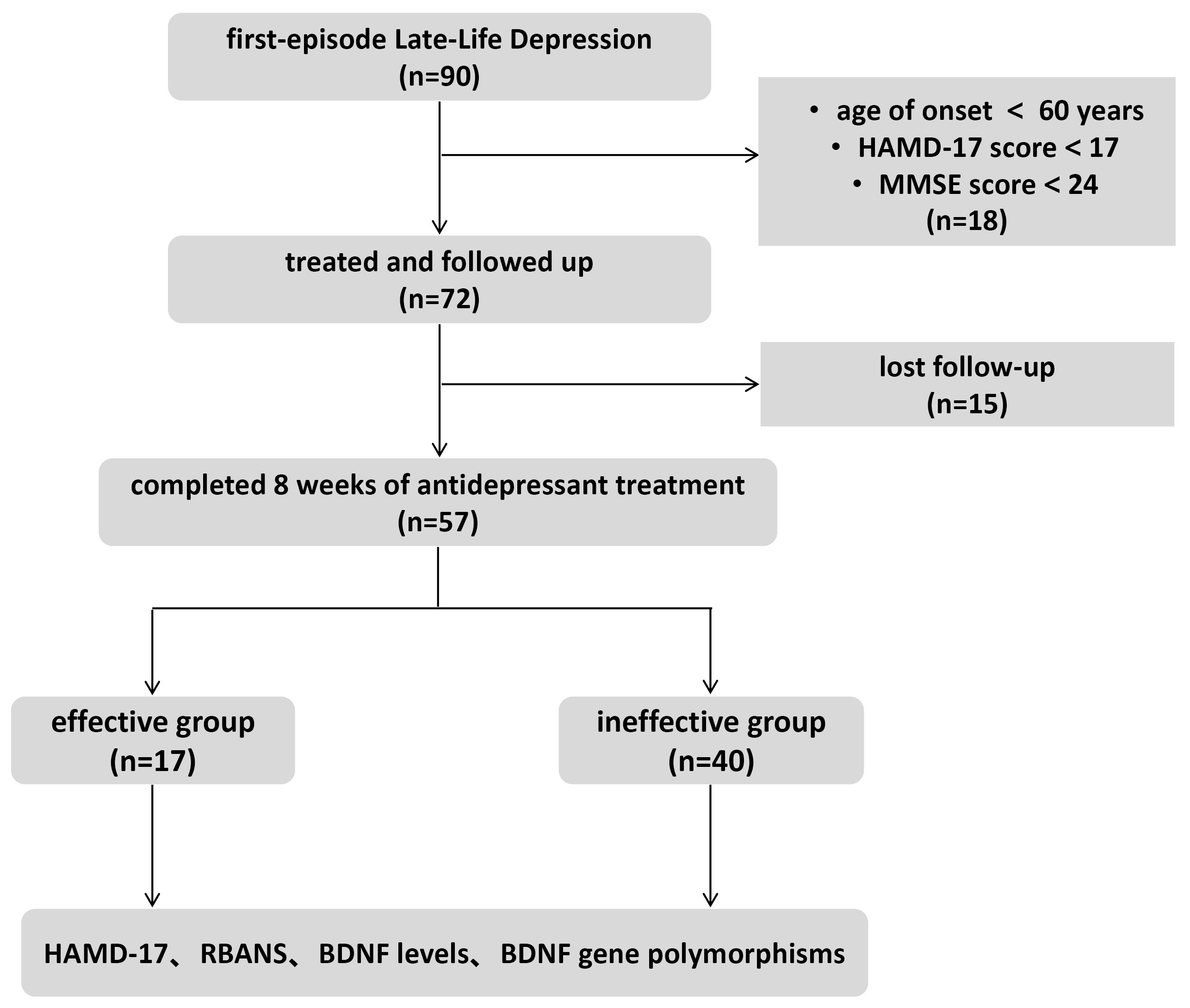

Initially, 90 patients were screened for the study, of whom 72 met the inclusion criteria. However, 15 patients withdrew before completing the 8-week treatment and follow-up assessments, leaving 57 patients in the final cohort (Fig. 1). The average age of participants was 68.8

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Enrollment flow chart. HAMD-17, 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor.

| Variable | Mean | Total patients (n = 57) | T/ | p | ||

| Effective group (n = 17) | Ineffective group (n = 40) | |||||

| Age (years) | 68.8 | 70.4 | 68.1 | 1.710 | 0.093 | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.525 | 1.290 | ||||

| Married (Living with spouse) | 23 (40.4) | 6 (26.1) | 17 (72.9) | |||

| Married (Living alone) | 24 (42.1) | 9 (52.9) | 15 (37.5) | |||

| Widowed | 10 (17.5) | 2 (11.8) | 8 (20.0) | |||

| Sex, n (%) | 4.191 | 0.041* | ||||

| Female | 38 (66.7) | 8 (21.1) | 30 (78.9) | |||

| Male | 19 (33.3) | 9 (47.4) | 10 (52.6) | |||

| Education, n (%) | 0.007 | 0.934 | ||||

| Junior high school and below | 34 (59.6) | 10 (29.4) | 24 (70.6) | |||

| High school and above | 23 (40.4) | 7 (30.4) | 16 (69.6) | |||

| Occupation, n (%) | 0.068 | 0.794 | ||||

| Informal | 35 (61.4) | 10 (28.6) | 25 (71.4) | |||

| Formal | 22 (38.6) | 7 (31.8) | 15 (68.2) | |||

| Disease duration (months) | 18.4 | 1.417 | 0.234 | |||

| 27 (47.4) | 6 (22.2) | 21 (77.8) | ||||

| 30 (52.6) | 11 (36.7) | 19 (63.3) | ||||

| BDNF gene polymorphism | 8.644 | 0.013* | ||||

| Met/Met | 15 (26.3) | 2 (13.3) | 13 (86.7) | |||

| Met/Val | 29 (50.9) | 7 (24.1) | 22 (75.9) | |||

| Val/Val | 13 (22.8) | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | |||

*p

Before treatment, the HAMD-17 score averaged 21.8

| Project | Before treatment | After treatment | t | p |

| HAMD-17 | 21.80 | 8.60 | 15.522 | 0.001* |

| RBANS | 146.70 | 155.4 | –2.287 | |

| Serum BDNF levels (ng/mL) | 31.50 | 38.46 | –4.461 | 0.026* |

*p

At baseline, the total RBANS score for the effective group was 148.20

| Changes of RBANS | Effective group | Ineffective group | t | p |

| Total score | 9.76 | 8.28 | 0.346 | 0.419 |

| Immediate memory | 3.00 | 1.65 | 0.760 | 0.450 |

| Delayed memory | 4.59 | 2.88 | 1.065 | 0.292 |

| Spatial construction | 0.12 | 0.78 | 0.348 | 0.729 |

| Language function | 1.71 | 1.93 | 0.158 | 0.875 |

| Attention | 2.29 | 2.00 | –0.113 | 0.911 |

At the end of the eighth week of treatment, BDNF levels were evaluated in both groups. In the effective group, the change in BDNF levels from baseline was 9626.39

| Group | Difference | Difference 95% CI | t | p |

| Ineffective group | 5833.13 | –3793.26 (–3805.75~–3780.78) | –0.57 | 0.573 |

| Effective group | 9626.39 |

| Group | Before treatment | After treatment | t | p |

| Ineffective group | 32,907.85 | 38,740.98 | –1.47 | 0.150 |

| Effective group | 28,176.70 | 37,803.09 | –2.29 | 0.036* |

| t | 1.08 | 0.17 | - | - |

| p | 0.286 | 0.863 | - | - |

*p

Treatment efficacy was analyzed as the dependent variable in a logistic regression model, incorporating age, sex, BDNF gene polymorphism, and changes in RBANS scores and BDNF levels. The analysis revealed that treatment efficacy was significantly associated with sex and the BDNF gene polymorphism Val/Val (Table 6).

| Project | Wald | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Age | 1.603 | 1.115 | 0.942–1.319 | 0.205 |

| Sex | 7.171 | 10.094 | 1.859–54.820 | 0.007* |

| Changes of RBANS | 0.121 | 0.991 | 0.943–1.042 | 0.728 |

| Changes of BDNF levels | 0.258 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.611 |

| BDNF gene polymorphism | 9.002 | 6.559 | 1.920–22.408 | 0.003* |

*p

This study explored the impact of an 8-week antidepressant treatment on serum BDNF levels in older patients experiencing first-episode major depression. It also examined the association between BDNF Val66Met gene polymorphism, treatment efficacy, and cognitive function. The results revealed that after 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment, Han Chinese patients with first-episode LLD exhibited significant improvements in depressive symptoms, increased serum BDNF levels, and enhanced cognitive function. The effective and ineffective groups found no significant differences in RBANS scores or serum BDNF levels. Binary logistic regression identified male sex and BDNF gene polymorphism as predictors of treatment efficacy.

BDNF, a protein distributed throughout the central nervous system, plays a vital role by interacting with the tyrosine kinase receptor B (TrkB), which supports neurogenesis, neuronal survival, differentiation, and plasticity [40]. Decreased serum BDNF levels are associated with a higher risk of depression, and antidepressant treatment can modulate these levels, thereby exerting antidepressant effects [41, 42, 43]. Our study found lower serum BDNF concentrations in patients with LLD, which increased considerably after 8 weeks of treatment. Similarly, Wolkowitz et al. [44] found lower baseline BDNF levels in depressed participants, which significantly increased after 8 weeks of treatment with escitalopram or sertraline, regardless of depression severity. A study involving 40 patients with LLD treated with paroxetine revealed lower baseline BDNF levels compared to the general population, normalizing after effective treatment, with minimal changes in the ineffective treatment group [45]. This observation suggests a potential link between increased serum BDNF levels and improved depressive symptoms. A meta-analysis indicated that various antidepressants have differing effects on BDNF levels [46], with sertraline showing a superior early increase in BDNF concentrations compared to other drugs (such as venlafaxine, paroxetine, or escitalopram) [46], This result underscores the value of further examining the relationship between BDNF and antidepressant pharmacology in peripheral blood. Despite the significant increase in BDNF levels and reduction in HAMD-17 scores observed in our study, no direct correlation was identified between BDNF level changes and treatment efficacy. Previous studies have reported increased BDNF levels in treatment responders or remitters but not in non-responders [30]. However, in this study, no significant differences in BDNF level changes were observed between the effective and ineffective treatment groups, which may be attributed to the small sample size.

Research on BDNF genetic polymorphisms, particularly Val66Met, often yields conflicting results. Aldoghachi et al. [47] examined three BDNF gene variants (rs6265, rs1048218, rs1048220) in 300 Malaysian participants with depression. The homozygous Met/Met genotype of rs6265 increased depression risk by 1.75 times compared to the Val/Val genotype. Similar findings were reported by Ribeiro et al. [48] in Caucasians and a study in Taiwan [49], both indicating an increased depression risk associated with the Met/Met genotype. However, Terracciano et al. [50] reported lower serum BDNF levels in depressed patients compared to non-depressed controls, with no significant association between BDNF Val66Met genotype and depression risk or serum BDNF levels. These results suggest that lower serum BDNF levels correlate with depression; the BDNF Val66Met genotype may not significantly influence this relationship.

Depression is associated with structural brain abnormalities in regions such as the prefrontal cortex, cingulate cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala [51]. Fractional anisotropy (FA), a measure of neuronal fiber integrity, reflects these structural changes [52]. Studies have explored genetic and environmental factors influencing FA and depression. For instance, BDNF Val66Met gene variations affect the integrity of the uncinate fasciculus (UF), with depressed individuals carrying the Met allele showing lower FA in the UF [20, 53]. Furthermore, the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism moderates the correlation between FA in the UF and depression severity [54]. Tatham et al. [55] demonstrated that antidepressant effects on the left UF related to BDNF genotype, with Val/Val carriers frequently exhibiting better FA and treatment response. These findings suggest that genetic influences on brain connectivity may influence antidepressant outcomes. Moreover, psychosocial factors, such as childhood adversity, significantly impact neural structure and interact with the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism [56, 57]. Jaworska et al. [58] reported no effect of the BDNF Val66Met variant on cortical thickness or hippocampal volume, aligning with other studies. However, Cao et al. [59] reported reduced hippocampal volume in Met allele carriers, consistent with previous research. Despite ongoing debate, it is clear that BDNF influences the structure of various brain regions, underscoring the need for further investigation into its role in the central nervous system.

The relationship between BDNF and antidepressant response is complex. Depression involves multiple neurobiological pathways, including the dopaminergic, noradrenergic, glutamatergic, and serotonergic systems, as well as inflammatory markers [60]. BDNF is crucial in mediating neuronal changes that contribute to symptom improvement during antidepressant treatment. Increased serum BDNF levels are frequently observed in patients undergoing treatment, suggesting that BDNF may serve as a potential biomarker for Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) response, given its involvement in the serotonin system [61]. However, there are conflicting reports on the long-term impact of antidepressant use on serum BDNF levels. Branchi [62] proposes that BDNF may only be one component of the broader, multifaceted effects of antidepressants, which may enhance brain plasticity rather than directly improve mood.

Depression is known to be nearly twice as prevalent in women as in men [63], and symptomatic profiles differ significantly between the sexes [64]. However, findings on sex differences in treatment response are less consistent, with many studies reporting no significant variation between men and women. Wilson et al. [65] assessed the role of sex in the relationship between acute functional connectivity changes (measured by functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging [fMRI]) and treatment response in LLD. Their findings indicated differences in one-day connectivity changes between remitters and non-remitters in men but not women. Our study suggests that male patients with LLD may benefit more from an 8-week antidepressant treatment. Further research should focus on segmenting male patients to enhance personalized and precise treatment strategies.

This study has several limitations. First, the absence of a healthy control group limits the ability to fully understand variations in BDNF levels among older patients with depression. Specifically, whether post-treatment BDNF levels differ from those of healthy controls remains unexplored. Second, the absence of a single medication and the small sample size may affect the interpretation of clinical significance. Third, the short observational period of only 8 weeks restricted data collection on long-term cognitive function and BDNF level changes, thereby hindering the observation of short- and long-term treatment effects. Lastly, our findings are based on strong antidepressant responses, defining treatment effectiveness as a 75% reduction in the HAMD-17 score is unusual and may lack clinical clarity, affecting comparability and generalizability of the findings.

In conclusion, antidepressant treatment for 8 weeks altered serum BDNF levels in patients with LLD, with male patients carrying the Val/Val genotype potentially responding better to conventional antidepressants.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Concept – XC, HW, JZ, WP, CL, LR; Design – XC, HW, WP, CL, LR; Supervision – WZ, WP, CL, LR; Data Collection and/or Processing – WZ, DZ; Analysis and/ or Interpretation – XC, DZ, JZ, FB; Literature Search – CL, LR; Writing – XC, HW, JZ, LR; Critical Review – HW, DZ FB, WZ, WP, CL. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University (Approval number. [2019] Scientific Research No. [40] - 201963FS-2). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment. The trial was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR1900024445).

We thank Bullet Edits Limited for the linguistic editing and proofreading of the manuscript. In addition, we are very grateful for the support and cooperation from the participants.

This study was supported by the Research and translational application of clinical characteristic diagnosis and treatment techniques in the capita of China (Z191100006619105).

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Wei Zheng is serving as one of the Editors in Chief of this journal. Chaomeng Liu is serving as one of the Editorial Board members of this journal. We declare that Wei Zheng and Chaomeng Liu had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Francesco Bartoli.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.