1. Introduction

Under normal conditions, serum Na concentrations in the human body are

finely maintained within a narrow range of 135–145 mmol/L despite large

fluctuations in water or salt intake [1]. Nevertheless, hyponatremia and

hypernatremia are relatively common electrolyte disorders [1, 2]. Minor

abnormalities in Na levels are common and rarely of clinical significance;

however, more severe Na disorders are still relatively common and are very

frequently clinically significant [3, 4, 5]. Hypernatremia, which is much less

common than hyponatremia, is generally defined as serum Na levels 145

mmol/L [1]. The degree of hypernatremia is generally considered mild when serum

Na levels are between 145 and 155 mmol/L and severe when serum Na

levels are 155 mmol/L [2]. Somewhat surprisingly, the exact boundaries of what

is considered the normal range of serum Na levels vary from institution to

institution, as do the boundaries between mild and severe hypernatremia [2, 6, 7].

When serum Na levels exceed 190 mmol/L, the hypernatremia becomes extreme

[8, 9]. Case reports have reported Na levels ranging from 207 to 255 mmol/L

[10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15].

It is well known that hypernatremia, especially when acute and severe, can

induce brain shrinkage that may cause vascular rupture and cerebral bleeding,

resulting in permanent neurologic damage or even death [10, 16, 17, 18]. Much less is

known about the effects of acute hypernatremia on the heart and the underlying

mechanisms. Data on the direct effects of acute hypernatremia on individual

membrane currents of cardiac myocytes are lacking. However, some data exist on

the changes in individual membrane currents of cardiac myocytes that are acutely

exposed to hyperosmotic solutions (induced by the addition of sucrose or mannitol

to the extracellular solution rather than hypernatremia). Such exposure is

associated with a rapid shrinkage of the cells through the loss of intracellular

water. This shrinkage occurs within 2–3 minutes and is fully reversible

[19, 20, 21, 22]. By exposing isolated guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes to

hyperosmotic Tyrode’s solution with a 1.5 times normal osmolarity, Ogura

et al. [21] observed decreases in cell volume of 19 2% (mean

standard error of the mean, SEM, n = 8) and of 20% [22]. A reduction of 19

2% (mean SEM, n = 8) was also observed by Missan

et al. [23], who also exposed isolated guinea pig ventricular

cardiomyocytes to hyperosmotic Tyrode’s solution with a 1.5 times normal

osmolarity. In isolated rat ventricular cardiomyocytes, 18% of the

cell volume is osmotically inactive [24]. In the rabbit, this is 34%

[19], and in the guinea pig it is 35% [21]. The decrease in cell

volume, without affecting membrane capacitance [22], may, by itself, affect

membrane currents by increasing the intracellular ion concentrations. However,

cell shrinkage may also have direct functional effects on the proteins embedded

in the cell membrane, including those of ion channels, pumps, and exchangers

[22, 25]. The available data on such direct functional effects of acute exposure

to a hyperosmotic solution on individual ion currents, as obtained in isolated

cardiomyocytes or an expression system, are summarized in Table 1 (Ref.

[20, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]).

Table 1.Effects of an acute exposure to a hyperosmotic solution on

individual cardiac ion currents.

| Current |

Cell preparation |

Hyperosmolarity |

Observation |

Study |

| I |

Guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes |

30% |

No consistent change of I |

Sasaki et al. [26] |

|

Guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes |

50% |

≈28% decrease in amplitude; slightly slowed inactivation |

Ogura et al. [20] |

|

Rat ventricular cardiomyocytes |

30% |

≈27% increase in amplitude; slightly accelerated inactivation |

Luo et al. [27] |

| I |

Guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes |

30% |

≈44% decrease in amplitude |

Sasaki et al. [26] |

|

Guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes |

50% |

≈30% decrease in amplitude |

Ogura et al. [22] |

|

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing I channels |

40% |

≈57% decrease in amplitude; no major effects on voltage dependence |

Yabuuchi et al. [28] |

| I |

Guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes |

50% |

≈50% decrease in amplitude |

Ogura et al. [22] |

|

Guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes |

50% |

“Marked inhibition” |

Missan et al. [23] |

| I |

Guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes |

50% |

No effect on I |

Missan et al. [23] |

| I |

Guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes |

30% |

≈23% increase in amplitude |

Wright et al. [29] |

| I |

Guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes |

50% |

≈40% decrease in amplitude |

Whalley et al. [25] |

|

Guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes |

30% |

≈70% decrease in amplitude, although the decrease was only apparent in 15 of 29 experiments |

Sasaki et al. [26] |

I, L-type Ca current; I, rapid delayed rectifier K

current; I, slow delayed rectifier K current; I, inward

rectifier K current; I, Na–Ca exchange current;

I, Na–K pump current. Hyperosmosis induced by the

addition of sucrose or mannitol to the extracellular solution.

The experimental data in Table 1 are required to construct a model for use in

computer simulations of the effects of acute hypernatremia (and associated

hyperosmosis) on the electrophysiology of single human ventricular

cardiomyocytes, as detailed in the Materials and Methods section below. In the

case of the rapid delayed rectifier K current (I), the slow delayed

rectifier K current (I), and the Na–K pump current

(I), the data from the different studies are largely consistent (Table 1). However, the experimental data for the L-type calcium Ca current

(I) from three studies seem inconsistent, at least at first glance. In

the study by Ogura et al. [20], in which the intracellular Ca

concentration ([Ca]) was only moderately buffered, accompanying

experiments with indo-1-loaded cardiomyocytes suggested that the decrease in

I amplitude was due to a rapid increase in [Ca] rather than

a direct functional effect on the I channels. This is in line with the

observations of Sasaki et al. [26], who observed “no consistent change

in I” when using a pipette solution containing 5.0 mmol/L ethylene glycol-bis (-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) or 10

mmol/L 1,2-bis (2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA), thereby strongly buffering [Ca]. Thus, the findings of

Ogura et al. [20] and Sasaki et al. [26] both suggest that

there is no direct effect from the hyperosmosis (osmolarity 1.5 times normal) on

the amplitude of I and that the apparent discrepancy in their

observations is largely due to the differences in the extent to which

[Ca] was buffered. However, Luo et al. [27], who used a

pipette solution containing 10 mmol/L EGTA, thus also strongly buffering

[Ca], still showed an 27% increase in I

amplitude (osmolarity 1.3 times normal).

In 2011, O’Hara et al. [30] published a comprehensive model of the

electrical activity of a single human ventricular cardiomyocyte, which has often

been considered the “gold standard” for such a model over the past decade [31].

This O’Hara–Rudy dynamic (ORd) cell model has since been widely used in computer

simulations of the electrical activity of a single human ventricular

cardiomyocyte in health and disease. However, starting from the ORd model, both

Tomek et al. [32] and Bartolucci et al. [31] developed novel,

very comprehensive models of the electrical activity of a single human

ventricular cardiomyocyte. These well-documented models were published in 2019

and 2020 and are known as the Tomek–Rodriguez model, following the ORd model

(ToR–ORd model) and the Bartolucci–Passini–Severi model as published in 2020

(BPS2020 model), respectively. Although both models can be considered major

updates of the ORd model, with many highly important improvements, they were

developed along different lines, which makes it useful to run simulations with

both models when, as we did in the present study, performing an in

silico study of the effects of acute hypernatremia on the electrophysiology of

single human ventricular cardiomyocytes.

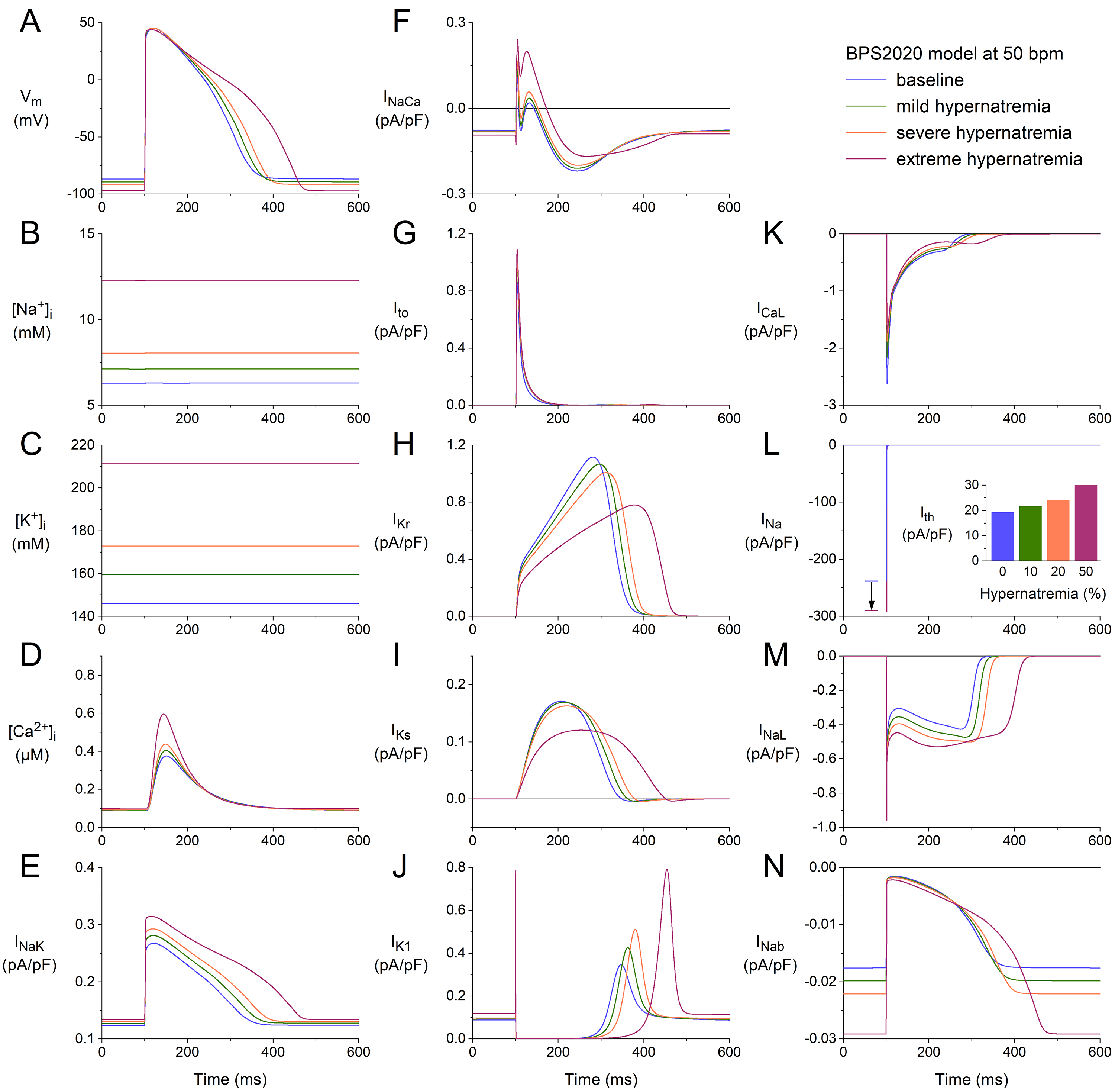

3. Results

First, we carried out computer simulations that examined the effects of

different levels of hypernatremia on the electrical activity of the BPS2020 model

of a single human ventricular cardiomyocyte. APs were elicited at a rate of 50,

75, and 100 per minute, resulting in beating rates of 50, 75, and 100 beats per

minute (bpm), respectively. Hypernatremia was simulated by increasing the

extracellular concentration of sodium chloride by 10, 20, and 50%, corresponding

to mild, severe, and extreme hypernatremia, respectively. Next, these simulations

were repeated with the ToR–ORd model to assess to which extent the observed

effects were model-dependent.

3.1 Effects of Hypernatremia in the BPS2020 Model

Fig. 1A shows APs (membrane potential, V) obtained after a simulated

period of 10 min of stimulation at 50 min under control conditions

(‘baseline’, blue trace) and at 10, 20, and 50% hypernatremia (green, orange,

and purple traces, respectively). Such a 10-minute period is sufficient to obtain

steady-state or quasi-steady-state behavior at each level of hypernatremia and

each stimulation rate tested. Fig. 1B–D shows the associated intracellular

Na, K, and Ca concentrations (denoted by [Na],

[K], and [Ca], respectively). The cell shrinkage that is

caused by the hyperosmosis of the extracellular solution results in increased

levels of both [Na] and [K] (Fig. 1B,C). The diastolic

resting level of [Ca] is hardly affected by the hypernatremia, but

there is an increase in its systolic peak value with increasing levels of

hypernatremia (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Effects of hypernatremia on the electrical activity of a single

human ventricular cardiomyocyte (BPS2020 model) at a beating rate of 50 bpm. (A)

Membrane potential (V). (B) Intracellular Na concentration

([Na]). (C) Intracellular K concentration ([K]).

(D) Intracellular Ca concentration ([Ca]). (E)

Na–K pump current (I). (F) Na–Ca exchange

current (I). (G) Transient outward K current (I). (H) Rapid

delayed rectifier K current (I). (I) Slow delayed rectifier K

current (I). (J) Inward rectifier K current (I). (K) L-type

Cacurrent (I). (L) Fast Na current (I). The vertical

arrow indicates the increase in I amplitude with increasing levels of

hypernatremia. (M) Late Na current (I). (N) Background Na

current (I). Note the differences in current scales. The inset to (L)

shows the threshold stimulus current (I) at the different levels of

hypernatremia. BPS2020, Bartolucci-Passini-Severi model as published in 2020; bpm, beats per minute.

The activity of the Na–K pump is, on the one hand, enhanced by the

increase in [Na], but on the other hand, reduced by the increase in

[K] as well as by the cell shrinkage per se (as observed

experimentally, as described in the Introduction section, and represented in the

model as set out in the Materials and Methods section). The net effect is an

increase in I (Fig. 1E), which is, however, insufficient to keep

[Na] at its baseline level. The activity of the Na–Ca

exchanger is not only enhanced by the increase in [Ca] but also by

the cell shrinkage per se (as observed experimentally, as described in

the Introduction section, and represented in the model as set out in the

Materials and Methods section). The net effect is an increase in I (Fig. 1F). The time course of the transient outward current (I; Fig. 1G), which

is a K current, is only slightly dependent on the level of hypernatremia.

This is because the activation of I is largely determined by the AP

upstroke and early repolarization phases, which do not show a marked change (Fig. 1A). Its amplitude increases with increasing hypernatremia, among other things,

due to the increase in its driving force by the hyperpolarization of the K

equilibrium potential (E) as a result of the increase in [K]

(Fig. 1C). The driving force of I and I is also increased. Yet,

both currents show a decreased amplitude with increasing hypernatremia (Fig. 1H,I). This is largely due to the cell shrinkage-induced decrease in their fully

activated conductance (as observed experimentally, as described in the

Introduction section, and represented in the model as set out in the Materials

and Methods section). I increases with increasing hypernatremia (Fig. 1J),

entirely due to its voltage dependence and the hypernatremia-induced

hyperpolarization of V (Fig. 1A).

I shows a complex dependence on intracellular and extracellular ion

concentrations and voltage. The net effect of the hypernatremia is a decrease in

its amplitude (Fig. 1K). The fast Na current (I), on the other hand,

shows an increase with increasing hypernatremia (Fig. 1L), which is largely due

to the reduction in its steady-state inactivation due to the hyperpolarization of

the resting membrane potential between consecutive APs (Fig. 1A). This increase

per se would result in a faster activation of neighboring cells and an

associated increase in conduction velocity. However, this is counteracted by

reduced excitability, as reflected by the increase in threshold stimulus current

(I; Fig. 1L, inset). The late I (I) also shows an increase

with increasing hypernatremia (Fig. 1M), which is also largely due to the

reduction of its steady-state inactivation due to the hyperpolarization of the

resting membrane potential between consecutive APs (Fig. 1A). The model cell has

several other inward and outward currents, in addition to those shown in Fig. 1E–M. These include the background Na, K, and Ca currents

(I, I, and I, respectively) and the sarcolemmal Ca

pump current (I). As illustrated in Fig. 1N for I, these other

currents also depend on the level of hypernatremia through their dependence on

ion concentrations and voltage. However, as illustrated in Fig. 1N, these

currents are so small that they hardly contribute to the net membrane current.

The net effect of the hypernatremia-induced changes in ion concentrations (Fig. 1B–D) and membrane currents (Fig. 1E–N) is hyperpolarization and prolongation

of the AP (Fig. 1A). The hyperpolarization amounts to 2.5, 4.8, and 10.3 mV under

conditions of mild, severe, and extreme hypernatremia, respectively, whereas the

AP duration (APD) at 90% repolarization (APD) is increased by 7, 14, and

46%, respectively. As a direct effect of the increase in I amplitude

(Fig. 1L), the maximum AP upstroke velocity ((dV/dt)) is increased

by 11, 18, and 23% under conditions of mild, severe, and extreme hypernatremia,

respectively. At the same time, I is increased by 12, 25, and 55%,

respectively (Fig. 1L, inset).

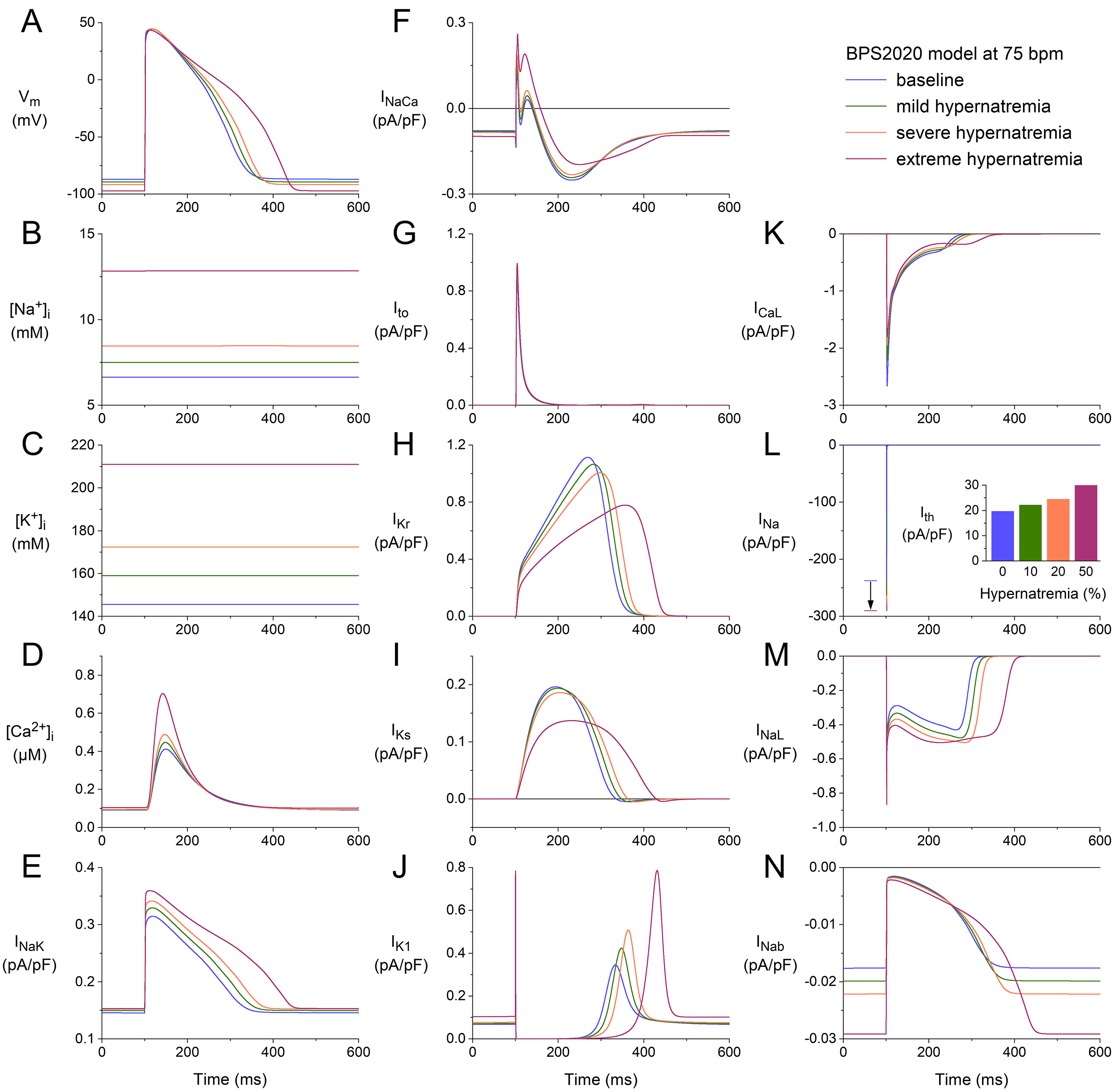

We repeated our simulations with the BPS2020 model at higher stimulation rates

of 75 and 100 min. The results obtained at these two rates (Figs. 2,3) are

qualitatively similar to those obtained at 50 min (Fig. 1). Rate-dependent

quantitative differences with respect to ion concentrations include a higher

level of [Na] (Figs. 2B,3B), higher peak amplitude of

[Ca] (Figs. 2D,3D), and a higher activity of the Na–K

pump (Figs. 2E,3E). Rate-dependent quantitative differences concerning individual

membrane currents include a decrease in I due to the smaller amount of

time available between consecutive APs for its relatively slow recovery from

inactivation and an increase in I due to the smaller amount of time

available between consecutive APs for its relatively slow deactivation. The

hypernatremia-induced AP hyperpolarization and prolongation observed at 50 bpm

(Fig. 1A) were also examined at 75 bpm (Fig. 2A) and 100 bpm (Fig. 3A). The same

holds for the hypernatremia-induced increase in I amplitude (Figs. 2L,3L)

and the associated increase in (dV/dt), and the

hypernatremia-induced increase in I (Fig. 2L, inset; Fig. 3L, inset).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Effects of hypernatremia on the electrical activity of a single

human ventricular cardiomyocyte (BPS2020 model) at a beating rate of 75 bpm. (A)

V. (B) [Na]. (C) [K]. (D) [Ca]. (E)

I. (F) I. (G) I. (H) I. (I) I. (J)

I. (K) I. (L) I. The vertical arrow indicates the increase

in I amplitude with increasing levels of hypernatremia. (M) I. (N)

I. Axis scales are identical to those in Fig. 1. The inset to (L) shows

I at the different levels of hypernatremia. BPS2020, Bartolucci-Passini-Severi model as published in 2020; bpm, beats per minute.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Effects of hypernatremia on the electrical activity of a single

human ventricular cardiomyocyte (BPS2020 model) at a beating rate of 100 bpm.

(A) V. (B) [Na]. (C) [K]. (D) [Ca].

(E) I. (F) I. (G) I. (H) I. (I) I. (J)

I. (K) I. (L) I. The vertical arrow indicates the increase

in I amplitude with increasing levels of hypernatremia. (M) I. (N)

I. Axis scales are identical to those in Figs. 1,2. The inset to (L)

shows I at the different levels of hypernatremia. BPS2020, Bartolucci-Passini-Severi model as published in 2020; bpm, beats per minute.

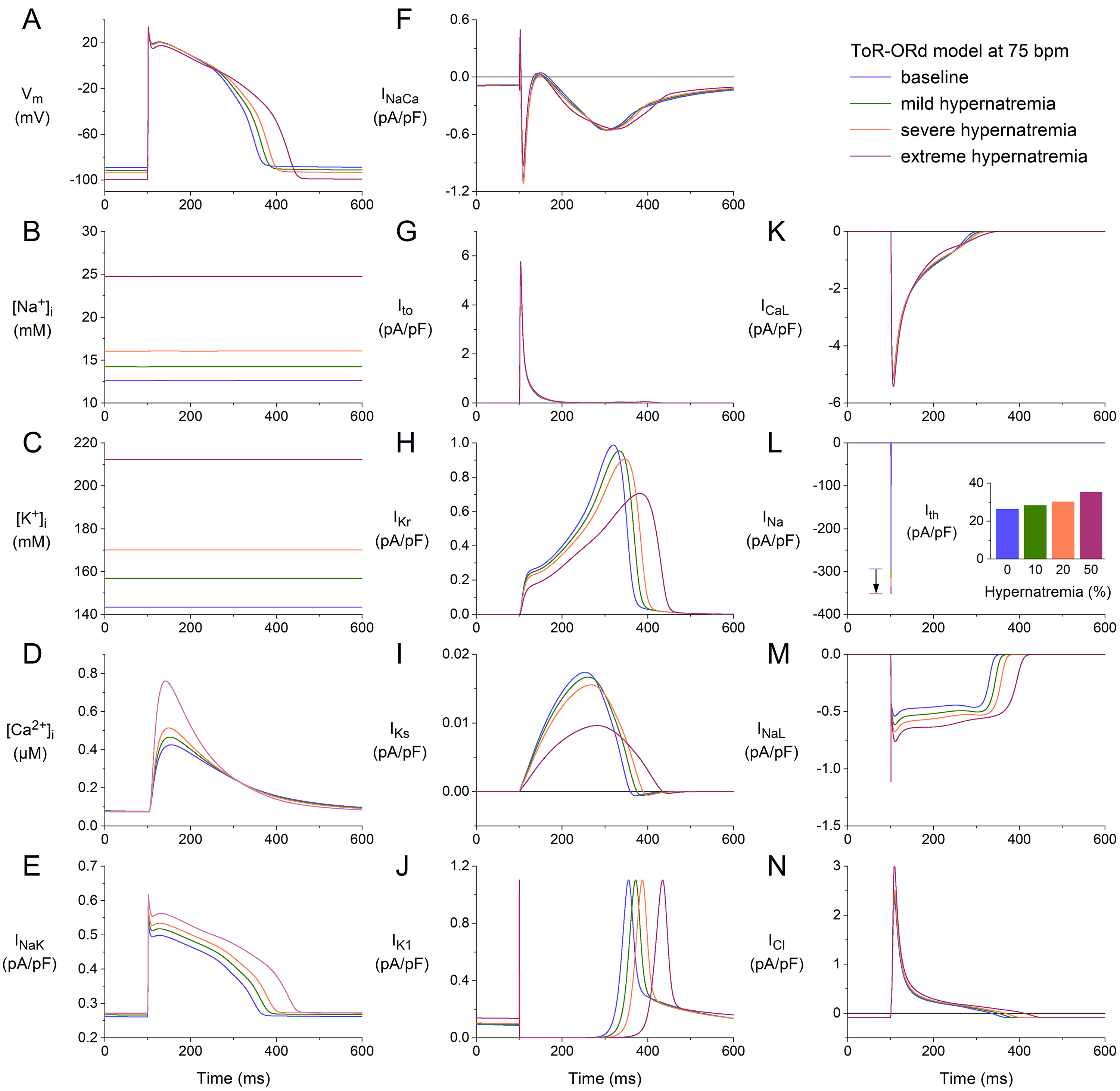

3.2 Effects of Hypernatremia in the ToR–ORd Model

As the Introduction mentions, the ToR–ORd and BPS2020 models can be considered

major updates of the O’Hara et al. [30] “ORd” model. Since the

ToR–ORd and BPS2020 models were developed largely independently and along

different lines, meaning the simulation results obtained with the two models are

not a priori highly similar, we repeated the above simulations using the

ToR–ORd model. This model has default values for the extracellular Na,

K, and Ca concentrations (denoted by [Na],

[K], and [Ca], respectively) of 140, 5.0, and 1.8

mmol/L, respectively, as opposed to 144, 5.4, and 2.7 mmol/L, respectively, in

the BPS2020 model. Furthermore, unlike the BPS2020 model, it includes a Cl

membrane current (I). However, the intracellular Cl concentration

cannot change dynamically, like [Na], [K], and

[Ca] can. The equations describing the time or voltage dependence of

individual membrane currents may differ between the two models. Moreover,

parameters in these equations, such as the fully activated conductance of a

specific current, may vary between the two models so that specific currents can

have larger or smaller amplitudes in the ToR–ORd model than in the BPS2020 model

and, thus, play a more or less important role in the ToR–ORd than in the BPS2020

model.

Fig. 4 shows the results obtained using the ToR–ORd model at a stimulation rate

of 50 min. The format and time scale are identical to those in Figs. 1,2,3.

However, not all of the ordinate scales are identical. Yet, without comparing the

ordinate scales, it is immediately clear that the APs from the ToR–ORd and

BPS2020 models differ in the presence of a notch. When comparing the ordinate

scales of Fig. 4G and Fig. 1G, it is clear that I is approximately five

times as large in the ToR–ORd model as in the BPS2020 model, giving way to a

faster early repolarization and associated AP notch. At the same time, a

comparison of the ordinate scales in Fig. 4I and Fig. 1I identifies that I

is almost one order of magnitude smaller in the ToR–ORd model than in the

BPS2020 model, which is important for our simulations because I is one of

the currents that is reduced by cell shrinkage per se. Other remarkable

differences are the [Na] level, which reaches 23.3 mmol/L in the

ToR–ORd model vs. 12.3 mmol/L in the BPS2020 model (Fig. 4B

vs. Fig. 1B), and the absence of an increase in the amplitude of

I with an increase in the level of hypernatremia (Fig. 4J vs.

Fig. 1J).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Effects of hypernatremia on the electrical activity of a single

human ventricular cardiomyocyte (ToR–ORd model) at a beating rate of 50 bpm.

(A) V. (B) [Na]. (C) [K]. (D) [Ca].

(E) I. (F) I. (G) I. (H) I. (I) I. (J)

I. (K) I. (L) I. The vertical arrow indicates the increase

in I amplitude with increasing levels of hypernatremia. (M) I. (N)

Chloride current (I). Note that the ordinate scales are not identical to

those in Figs. 1,2,3. The inset to (L) shows I at the different levels of

hypernatremia. ToR–ORd, Tomek–Rodriguez model following the O’Hara–Rudy dynamic model; bpm, beats per minute.

Despite the remarkable differences in [Na] level and some of the

individual membrane currents, the net effects of the hypernatremia on the AP

configuration are, at least qualitatively, quite similar to those observed using

the BPS2020 model. The hypernatremia-induced AP hyperpolarization amounts to 2.3,

4.4, and 10.1 mV under conditions of mild, severe, and extreme hypernatremia,

respectively, vs. values of 2.5, 4.8, and 10.3 mV in the BPS2020 model.

The APD was increased by 6, 12, and 30% under mild, severe, and extreme

hypernatremia conditions, whereas this prolongation amounted to 7, 14, and 46%,

respectively, in the BPS2020 model. The (dV/dt) was increased by 7,

11, and 12% under conditions of mild, severe, and extreme hypernatremia,

respectively, whereas this increase amounted to 11, 18, and 23%, respectively,

in the BPS2020 model. I showed an increase of 7, 15, and 34%,

respectively, which was 12, 25, and 55%, respectively, in the BPS2020 model.

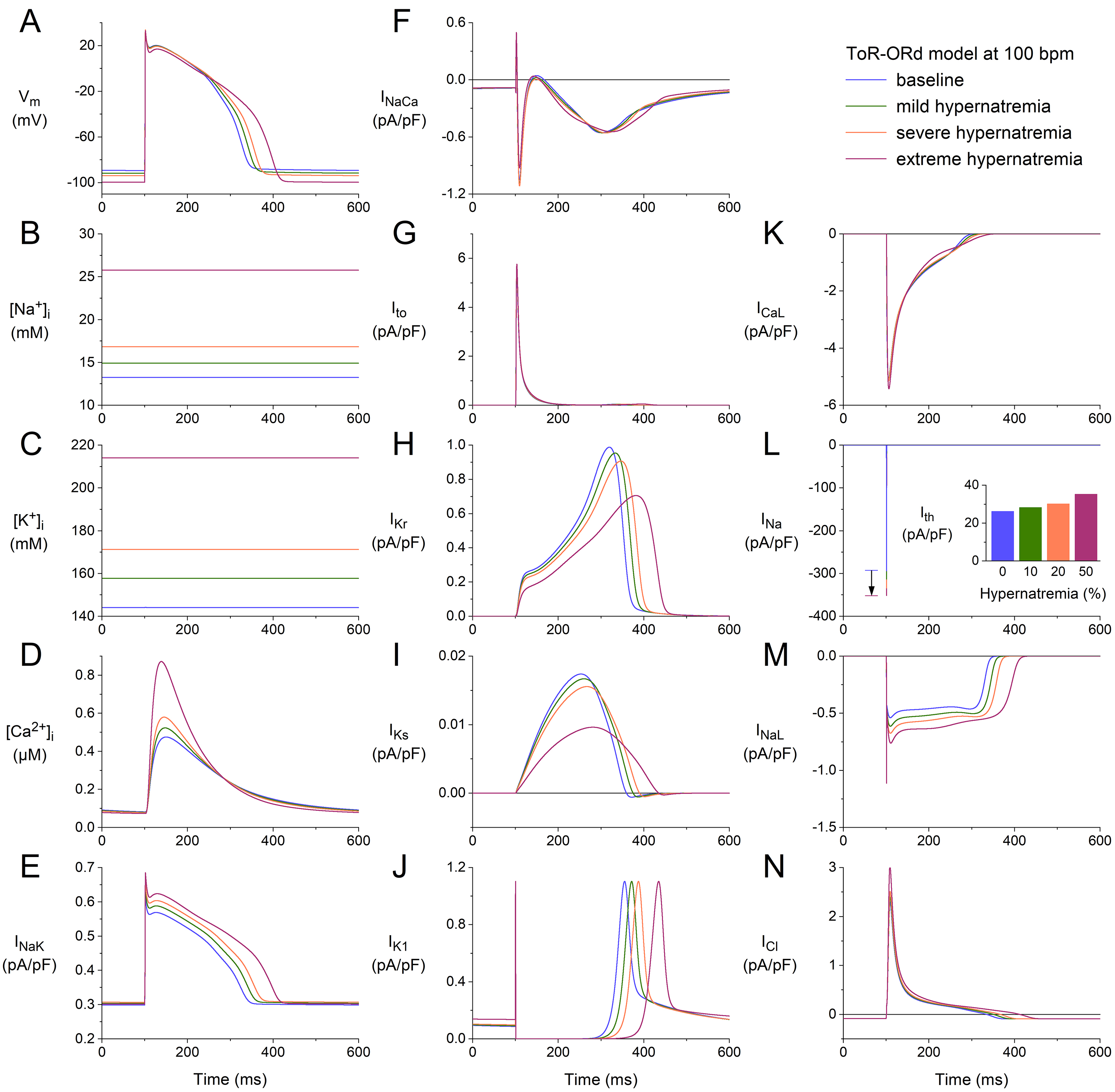

We repeated our simulations using the ToR–ORd model at higher stimulation rates

of 75 and 100 min. The results obtained at these two rates (Figs. 5,6) are

qualitatively similar to those obtained at 50 min (Fig. 4). Rate-dependent

quantitative differences with respect to ion concentrations include a somewhat

higher level of [Na] (Figs. 4B,5B,6B), the substantially higher peak

amplitude of [Ca] (Figs. 4D,5D,6D), and a somewhat higher activity

by the Na–K pump (Figs. 4E,5E,6E). Rate-dependent quantitative

differences with respect to individual membrane currents include a slight

decrease in I, as observed with the BPS2020 model. However, the

rate-dependent increase in I is now only marginal (Figs. 4I,5I,6I). As

mentioned, there is no increase in I with increasing hypernatremia (Figs. 4J,5J,6J), in contrast to the BPS2020 model. This is due to differences in the

current-voltage relationship of this current between the two models. The

hypernatremia-induced AP hyperpolarization and prolongation observed at 50 bpm

(Fig. 4A) were also examined at 75 bpm (Fig. 5A) and 100 bpm (Fig. 6A). The same

holds for the hypernatremia-induced increase in I amplitude (Figs. 5L,6L)

and the associated increase in (dV/dt), and the

hypernatremia-induced increase in I (Fig. 5L, inset; Fig. 6L, inset).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Effects of hypernatremia on the electrical activity of a single

human ventricular cardiomyocyte (ToR–ORd model) at a beating rate of 75 bpm.

(A) V. (B) [Na]. (C) [K]. (D) [Ca].

(E) I. (F) I. (G) I. (H) I. (I) I. (J)

I. (K) I. (L) I. The vertical arrow indicates the increase

in I amplitude with increasing levels of hypernatremia. (M) I. (N)

I. Axis scales are identical to those in Fig. 4. The inset to (L) shows

I at the different levels of hypernatremia. ToR–ORd, Tomek–Rodriguez model following the O’Hara–Rudy dynamic model; bpm, beats per minute.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Effects of hypernatremia on the electrical activity of a single

human ventricular cardiomyocyte (ToR–ORd model) at a beating rate of 100 bpm.

(A) V. (B) [Na]. (C) [K]. (D) [Ca].

(E) I. (F) I. (G) I. (H) I. (I) I. (J)

I. (K) I. (L) I. The vertical arrow indicates the increase

in I amplitude with increasing levels of hypernatremia. (M) I. (N)

I. Axis scales are identical to those in Figs. 4,5. The inset to (L) shows

I at the different levels of hypernatremia. ToR–ORd, Tomek–Rodriguez model following the O’Hara–Rudy dynamic model; bpm, beats per minute.

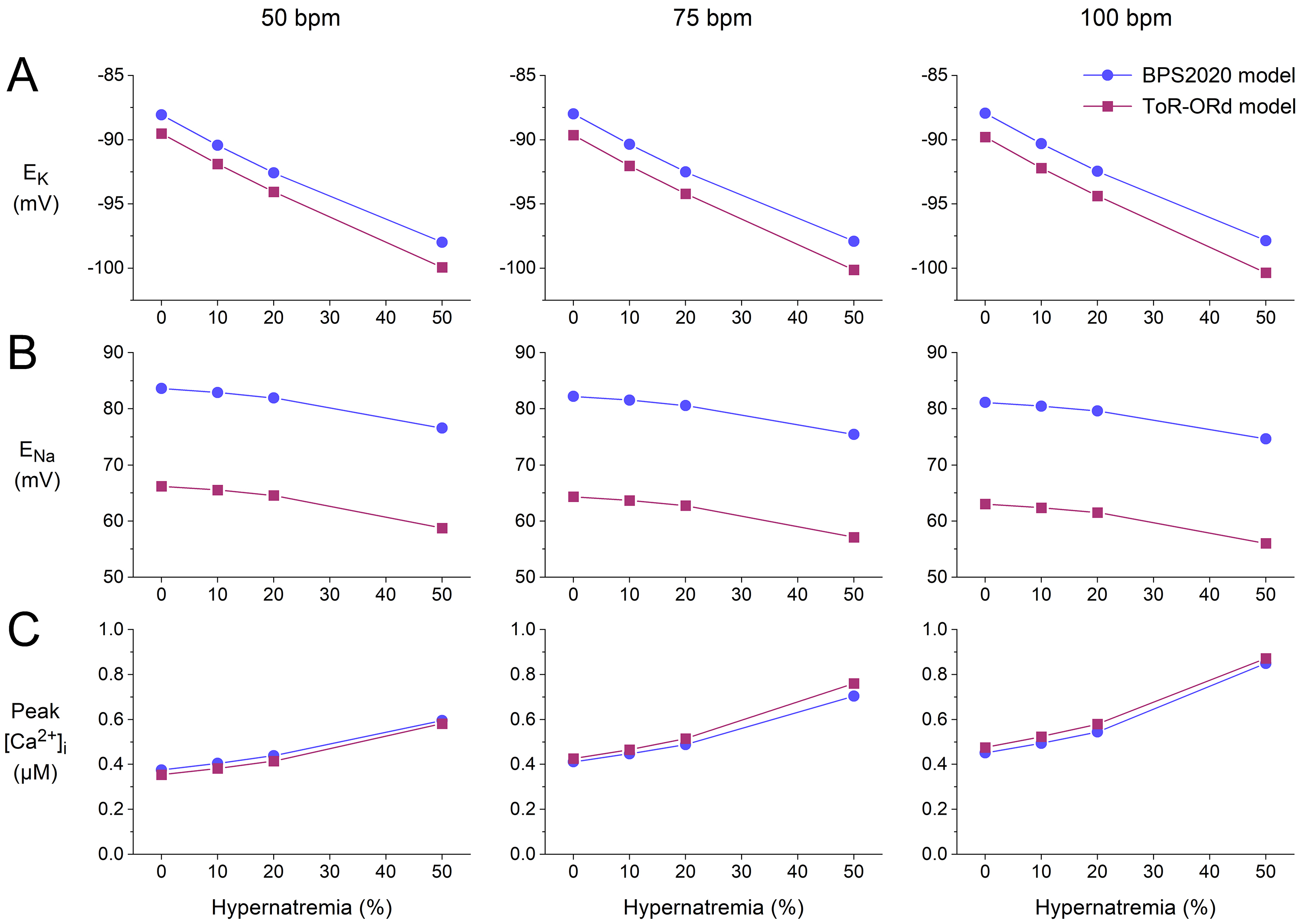

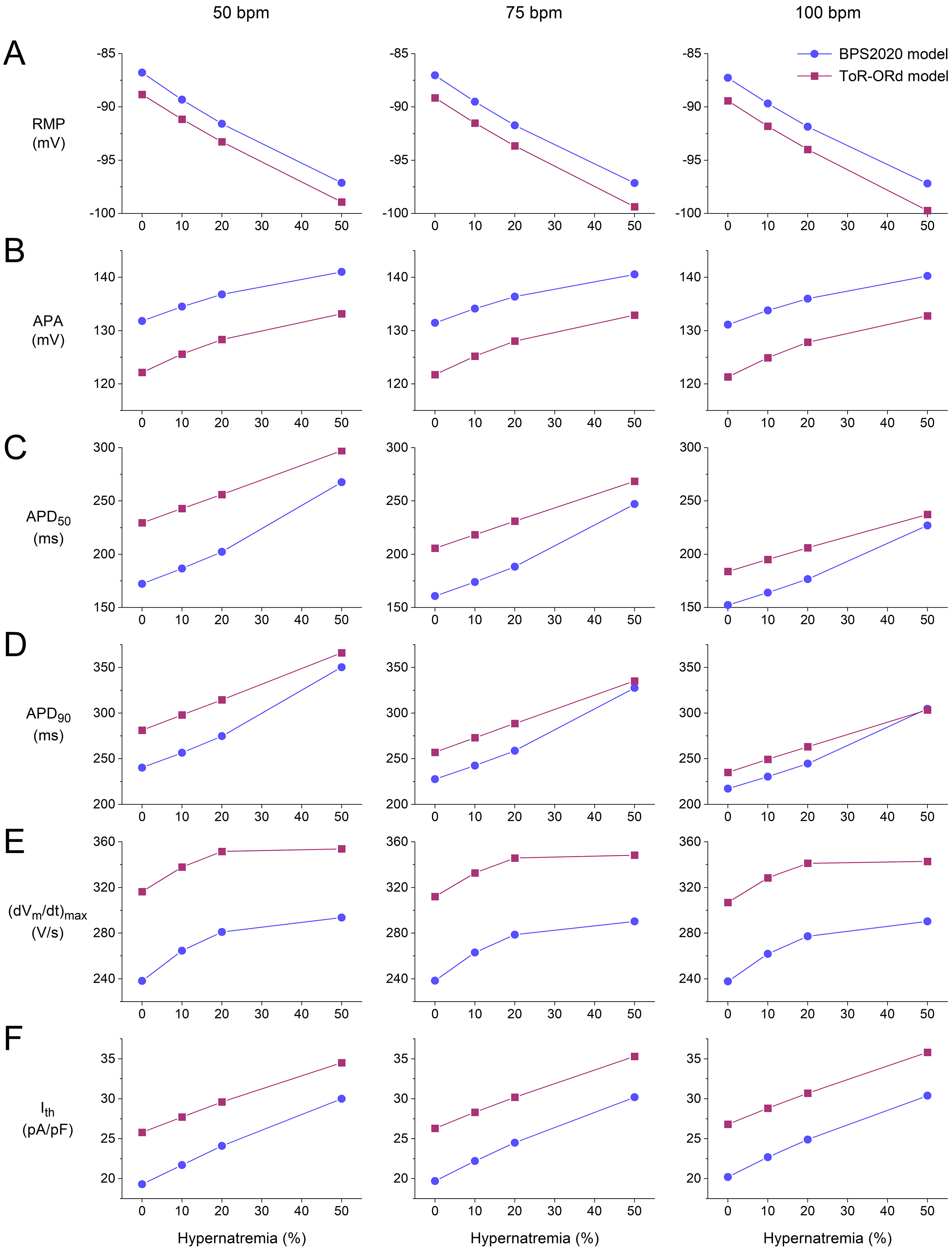

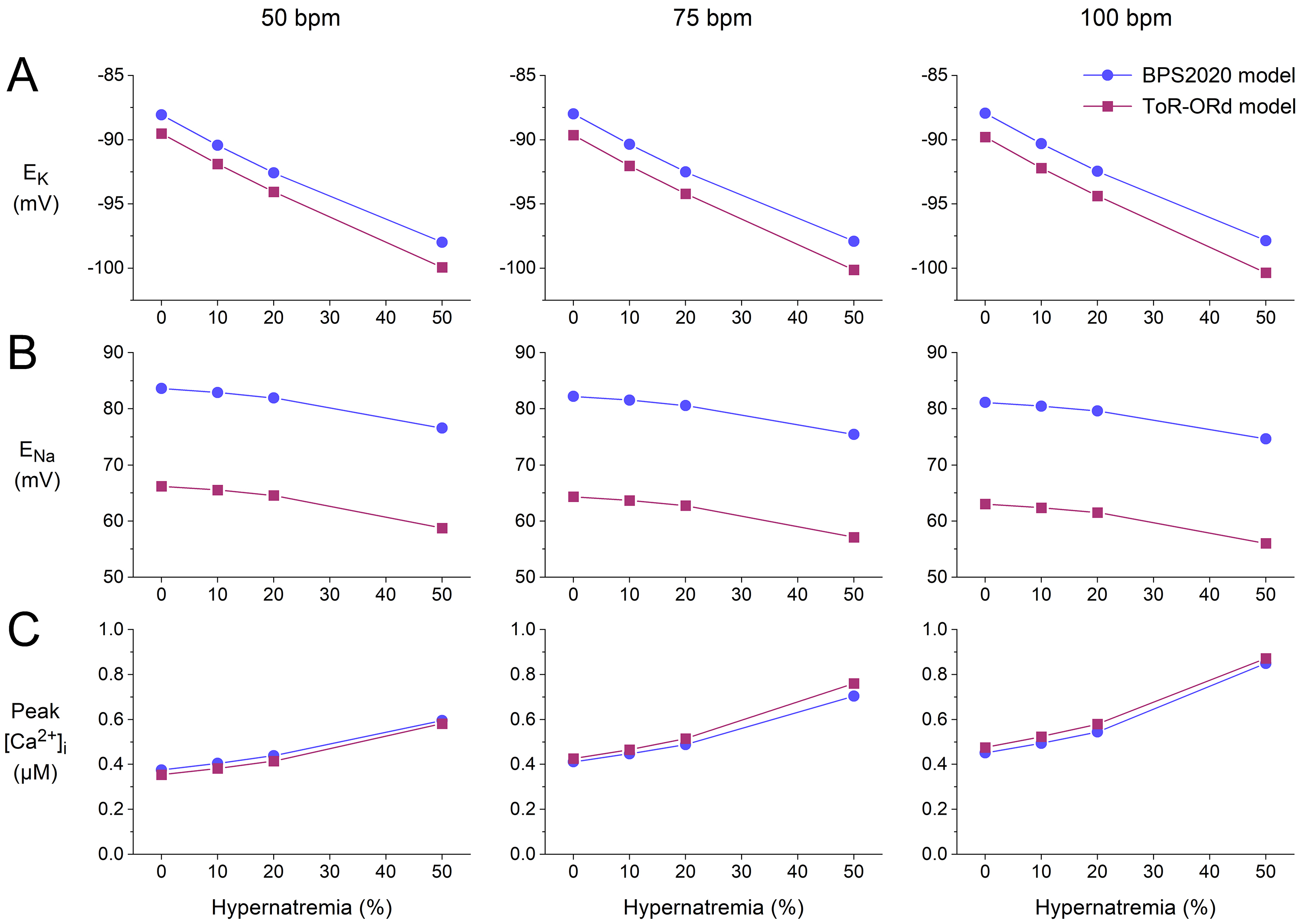

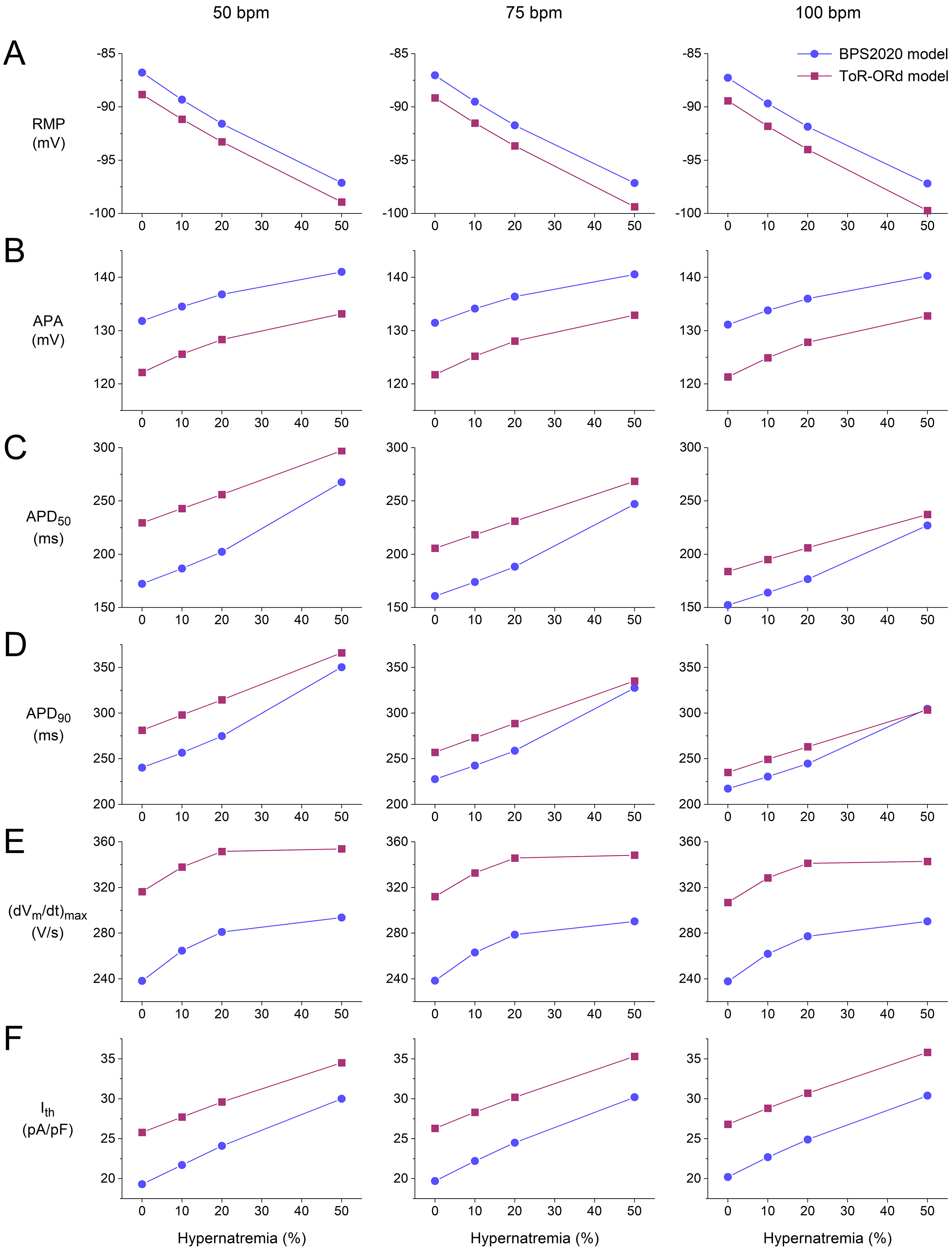

3.3 Summary of the Effects of Hypernatremia

The effects of hypernatremia in the two models of a single human ventricular

cardiomyocyte are summarized in Figs. 7,8.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Effects of hypernatremia on the sodium and potassium equilibrium

potentials and the peak intracellular calcium concentration in the BPS2020 and

ToR–ORd models of a single human ventricular cardiomyocyte. (A) K

equilibrium potential (E) as a function of hypernatremia at stimulation

rates of, from left to right, 50, 75, and 100 min. (B) Na

equilibrium potential (E) as a function of hypernatremia at 50, 75, and

100 min stimulation rates. (C) The peak amplitude of [Ca] as

a function of hypernatremia at 50, 75, and 100 min stimulation rates. Data

from the BPS2020 and ToR–ORd models are shown by filled blue circles and filled

purple squares, respectively. ToR–ORd, Tomek–Rodriguez model following the O’Hara–Rudy dynamic model; BPS2020, Bartolucci-Passini-Severi model as published in 2020; bpm, beats per minute.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Action potential (AP) parameters and threshold stimulus current

of the BPS2020 and ToR–ORd models of a single human ventricular cardiomyocyte.

(A) Resting membrane potential (RMP) as a function of hypernatremia at left to

right, 50, 75, and 100 min stimulation rates. (B) AP amplitude (APA) as a

function of hypernatremia at stimulation rates of 50, 75, and 100 min. (C)

AP duration at 50% repolarization (APD) as a function of hypernatremia at

stimulation rates of 50, 75, and 100 min. (D) AP duration at 90%

repolarization (APD) as a function of hypernatremia at stimulation rates

of 50, 75, and 100 min. (E) Maximum AP upstroke velocity

((dV/dt)) as a function of hypernatremia at stimulation rates of

50, 75, and 100 min. (F) I as a function of hypernatremia at

stimulation rates of 50, 75, and 100 min. Data from the BPS2020 and

ToR–ORd models are shown by filled blue circles and filled purple squares,

respectively. ToR–ORd, Tomek–Rodriguez model following the O’Hara–Rudy dynamic model; BPS2020, Bartolucci-Passini-Severi model as published in 2020; bpm, beats per minute.

In both models, the K and Na equilibrium potentials (E and

E, respectively), as computed from the extracellular and intracellular

K and Na concentrations, show a hyperpolarization, with a similar

dependence on the level of hypernatremia at each of the stimulation rates tested

(Fig. 7A,B). The hyperpolarization of E underlies the hypernatremia-induced

hyperpolarization of the RMP in the two models. The hyperpolarization of E

and E is associated with changes in the driving force of individual

membrane currents, which should be considered when studying the effects of

hypernatremia on these currents, as performed in our simulations. Both models

show a substantial increase in the peak amplitude of [Ca] with

increasing levels of hypernatremia (Fig. 7C). At each of the beating rates

tested, the two models show a highly similar dependence of this [Ca]

peak amplitude on the level of hypernatremia.

Fig. 8 shows how the AP parameters and I of the BPS2020 and ToR–ORd

model cardiomyocytes depend on the level of hypernatremia at each of the

stimulation rates tested. As already noted, the resting membrane potential (RMP) shows a hyperpolarization

that increases with increasing hypernatremia (Fig. 8A). This hyperpolarization is

largely responsible for the observed increase in AP amplitude (APA; Fig. 8B). The

hypernatremia-induced AP prolongation does not only translate into a

hypernatremia-dependent increase in APD (Fig. 8D), as already noted in

Sections 3.1 and 3.2, but also into a hypernatremia-dependent increase in the APD

at 50% repolarization (APD; Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8E demonstrates how (dV/dt) increases with increasing

hypernatremia, reflecting the hypernatremia-induced increase in I

amplitude. This increase was only small between 20 and 50% of the

hypernatremia, particularly in the case of the ToR–ORd model, whereas I

shows an almost linear dependence on the level of hypernatremia over the entire

range of the hypernatremia tested. Consequently, AP conduction will be impaired

at 50% hypernatremia as compared to lower levels of hypernatremia, provided that

this high level of hypernatremia does not affect AP conduction in other ways,

e.g., by cell shrinkage-induced structural perturbations of the nanodomains at

the intercalated disks which are involved in cardiac conduction, and because of

the localization of Na channels in the intercalated disks [35, 36].

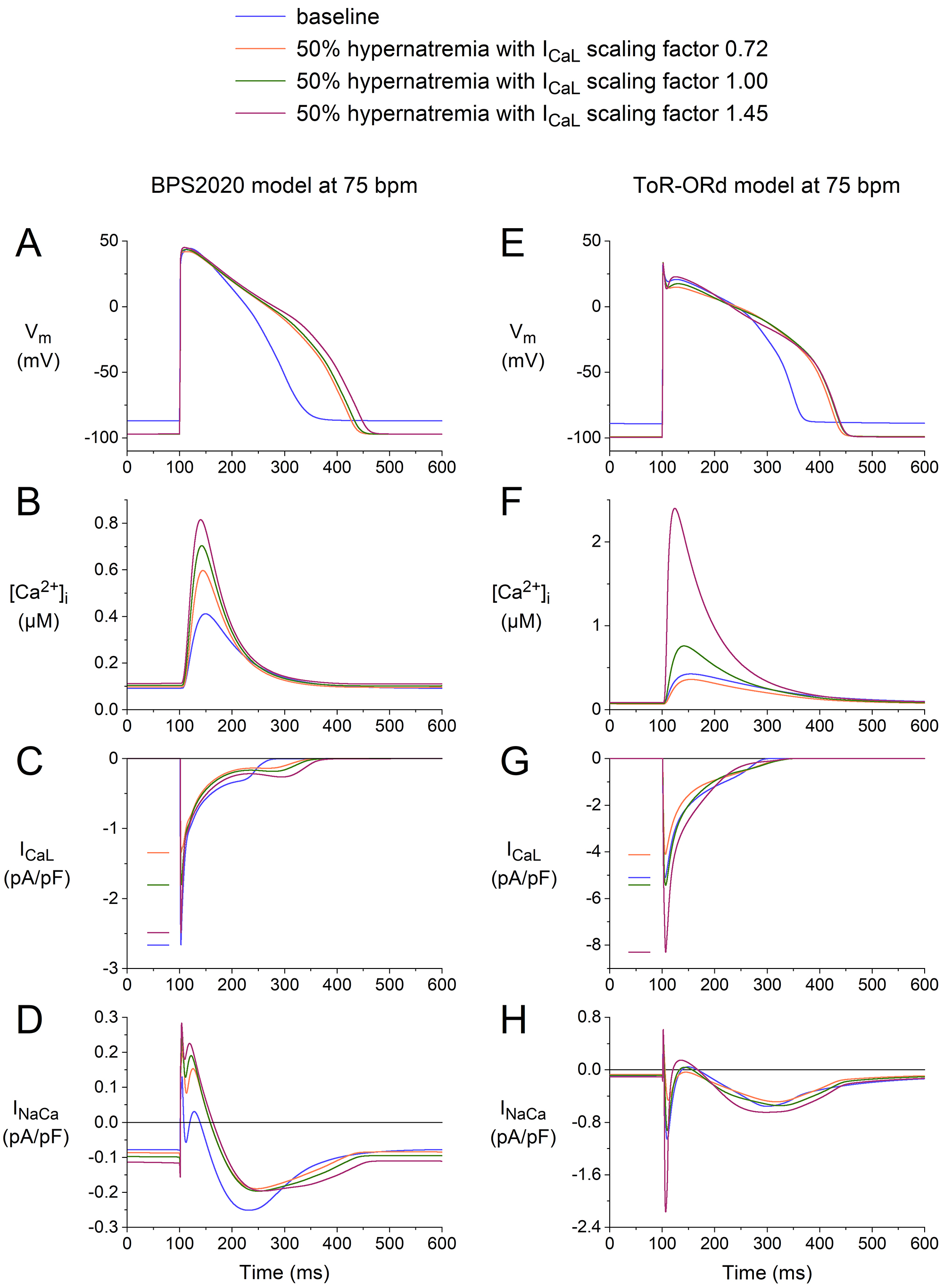

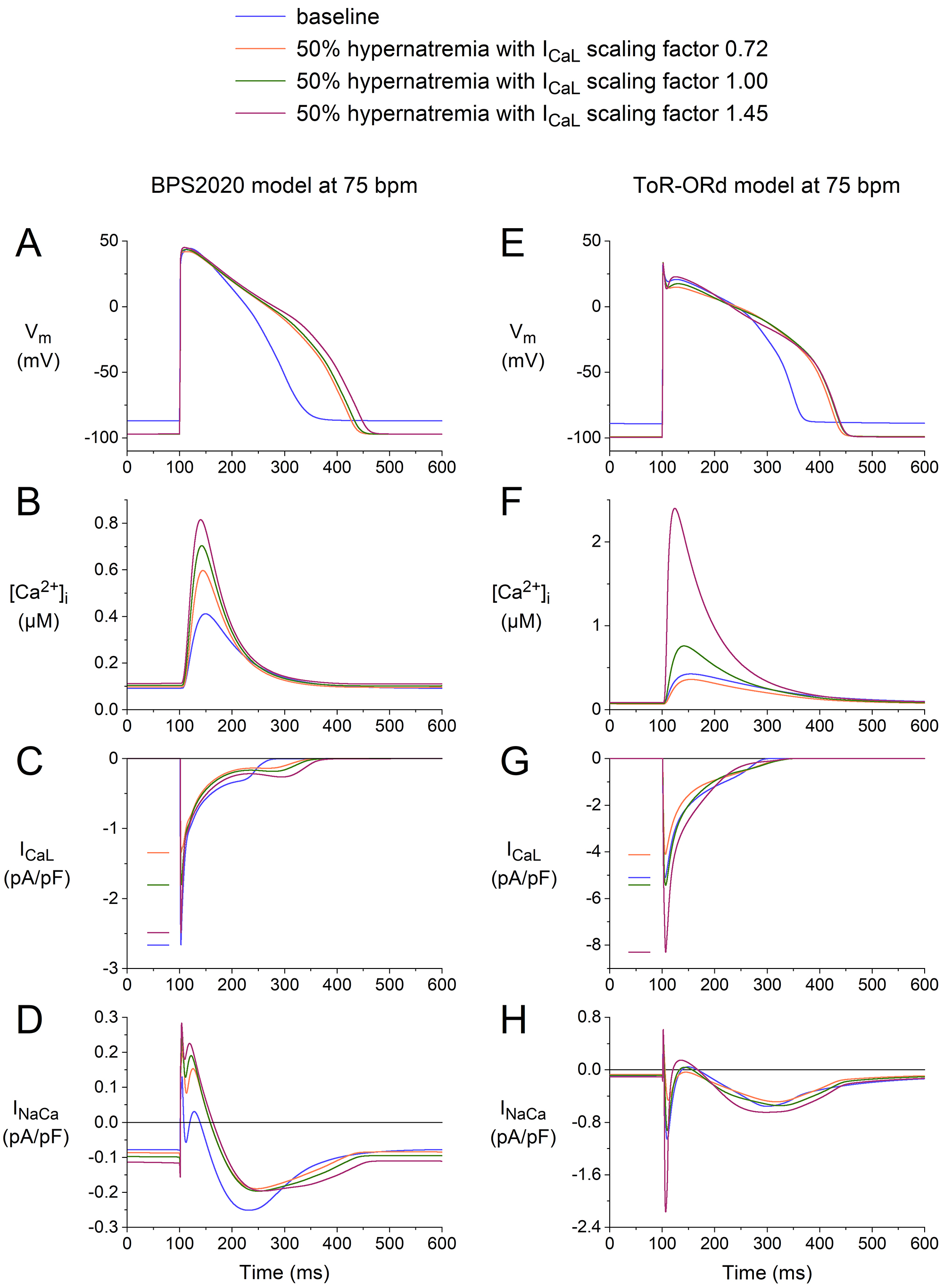

3.4 Effects of Scaling I

As noted in the Introduction, there is an apparent discrepancy in the

experimental data on the effects of acute exposure to a hyperosmotic solution on

I (Table 1). Therefore, we repeated some of our simulations using

I scaling factors other than the factor of 1.00, which was used in the

simulations presented in Figs. 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. We selected the extreme case of 50%

hypernatremia, where the effects are the most pronounced, and simulated both a

decrease in I with a scaling factor of 0.72 and an increase with a

scaling factor of 1.45. These scaling factors were derived from the experimental

data of Ogura et al. [20] and Luo et al. [27], respectively

(Table 1), disregarding our argument in the Introduction that the decrease in

I amplitude in the study of Ogura et al. [20] was due to a rapid

increase in [Ca] rather than a direct functional effect of the

hyperosmosis on the I channels.

The results of our simulations are shown in Fig. 9, focusing on the effects on

I and the associated effects on [Ca] and I. In both

models, increasing the I scaling factor from 1.00 to 1.45 resulted in an

increase in the inward peak of I (Fig. 9C,G), an increase in peak

[Ca] (Fig. 9B,F), and an increase in the activity of the

Na–Ca exchanger (Fig. 9D,H). As might be anticipated, decreasing

the I scaling factor from 1.00 to 0.72 had the opposite effects.

Interestingly, decreasing the I scaling factor from 1.00 to 0.72 still

results in a substantial increase in peak [Ca] as compared to

baseline in the BPS2020 model (Fig. 9B), but not in the ToR–ORd model, where

there is a small decrease (Fig. 9F). Thus, there would be a positive effect on

the contractile apparatus according to the BPS2020 model and a small negative

effect according to the ToR–ORd model. Apparently, the ‘crossover’ from a

positive to a negative effect has a different degree of decrease in the I

scaling factor in the two models. In this regard, it should be noted that an

increase in [Ca] compared to baseline, despite a decrease in the

I scaling factor to 0.72, is largely due to the reduction in cell volume

associated with the hypernatremia. Thus, even a substantially reduced amount of

Ca ions entering the cell or released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum can

still increase [Ca], as in the BPS2020 model, or cause only a small

decrease, as in the ToR–ORd model.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Effects of 50% hypernatremia and different scaling factors for I on the electrical activity of the BPS2020 and ToR–ORd models

for a single human ventricular cardiomyocyte at a beating rate of 75 bpm. (A)

V, (B) [Ca], (C) I, and (D) I in the BPS2020

model. (E) V, (F) [Ca], (G) I, and (H) I in

the ToR–ORd model. Note the differences in the ordinate scales. ToR–ORd, Tomek–Rodriguez model following the O’Hara–Rudy dynamic model; BPS2020, Bartolucci-Passini-Severi model as published in 2020; bpm, beats per minute.

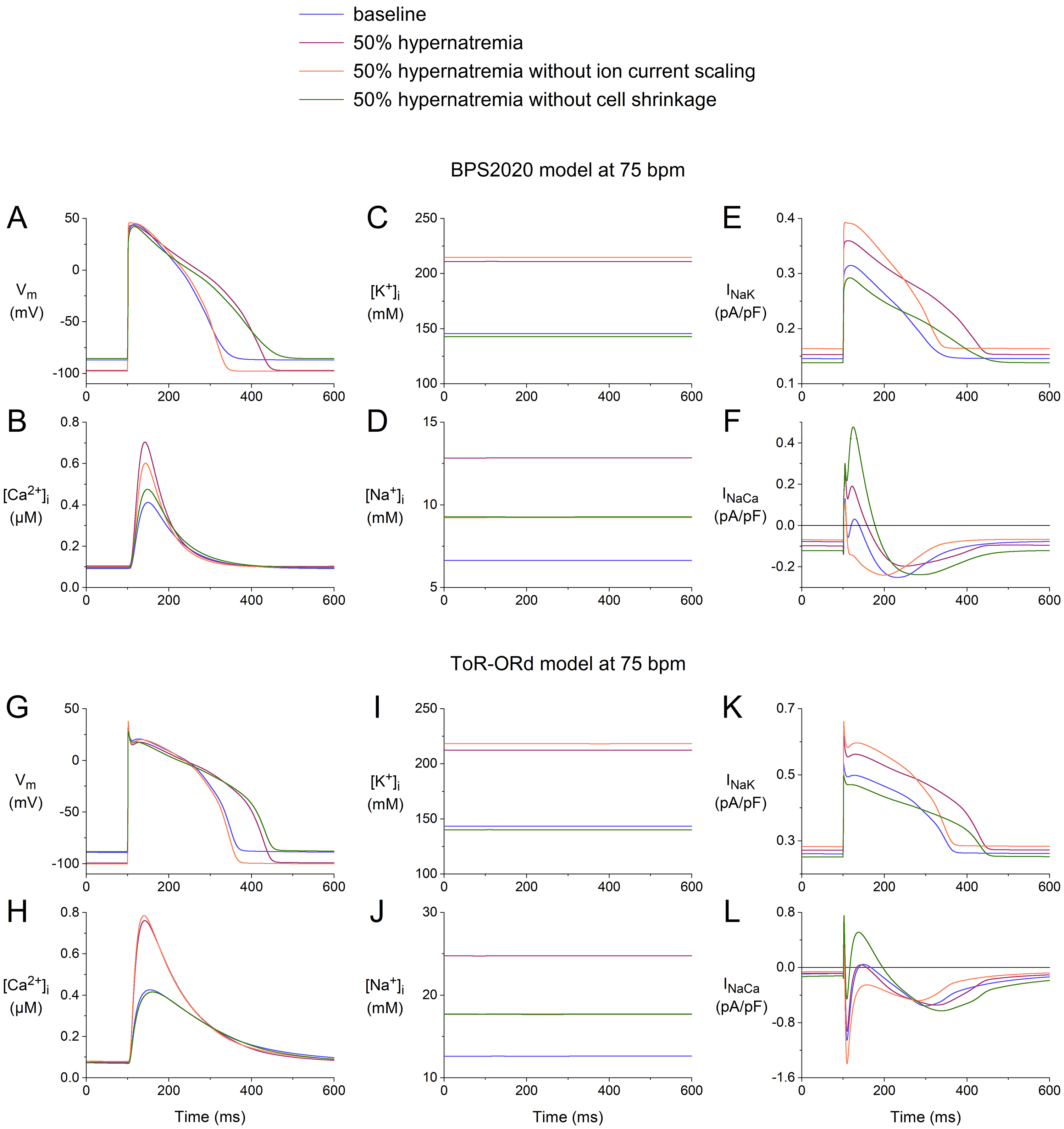

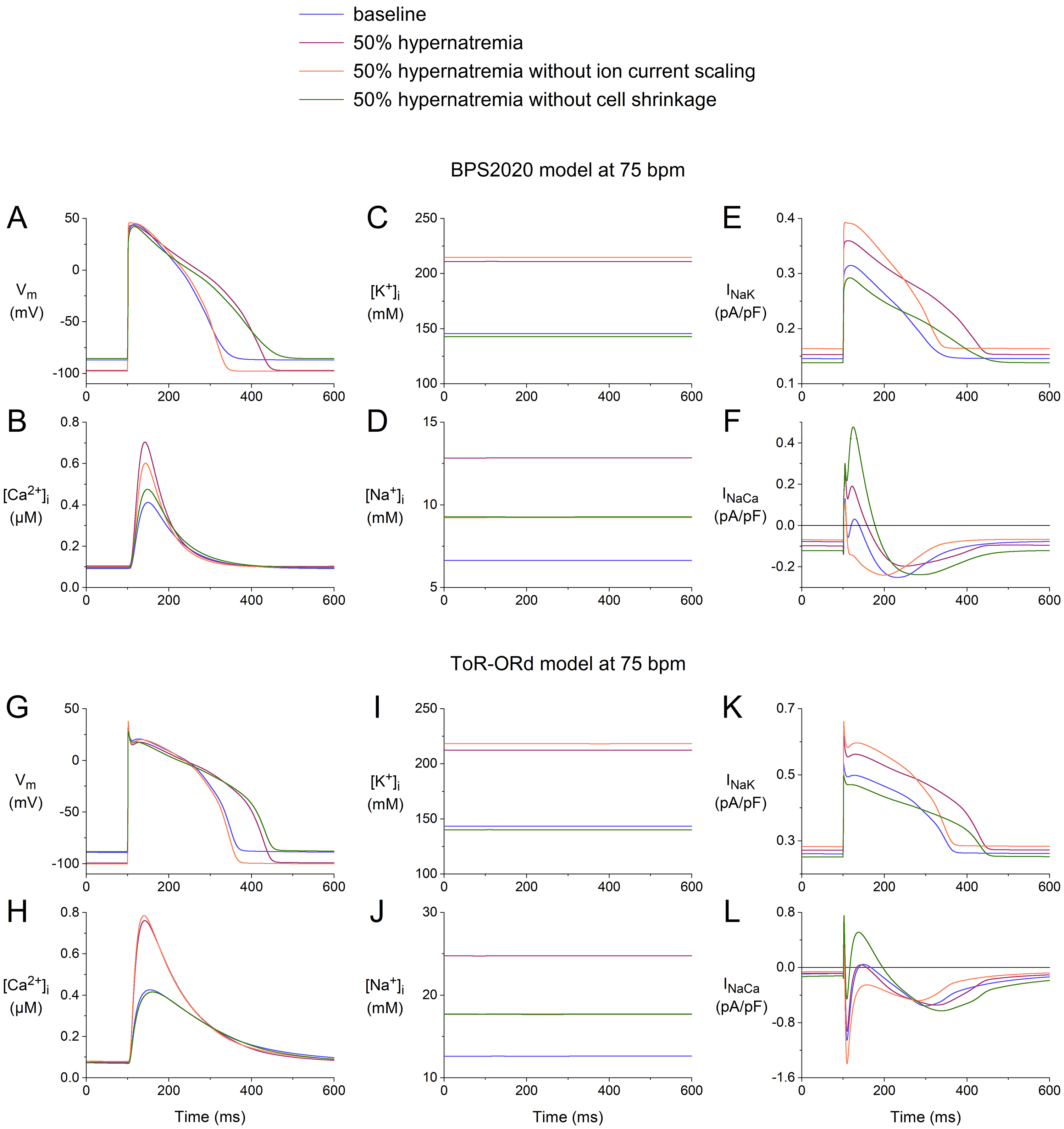

3.5 Effects of Ion Current Scaling vs. Cell Shrinkage

When simulating hypernatremia, we incorporated both the hypernatremia-induced

cell shrinkage and the hypernatremia-induced changes in I, I,

I, and I using the scaling factors listed in Table 2. To test

the effects of cell shrinkage and ion current scaling per se, we

simulated two hypothetical cases of hypernatremia, one in the absence of cell

shrinkage and one in the absence of ion current scaling. As in the simulations

presented in Fig. 9, we selected the extreme 50% level of hypernatremia, where

the effects are the most pronounced. The results of our simulations are shown in

Fig. 10, focusing on [Na], [K], and [Ca],

and the associated I and I.

Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Effects of 50% hypernatremia in the presence and absence of

ion current scaling and the presence and absence of cell shrinkage on the

electrical activity of the BPS2020 and ToR–ORd models for a single human

ventricular cardiomyocyte at a beating rate of 75 bpm. (A) V, (B)

[Ca], (C) [K], (D) [Na], (E) I, and

(F) I in the BPS2020 model. (G) V, (H) [Ca], (I)

[K], (J) [Na], (K) I, and (L) I in the

ToR–ORd model. Note the differences in the ordinate scales. Note also that the

green and orange traces coincidentally overlap almost completely in both (D) and

(J). ToR–ORd, Tomek–Rodriguez model following the O’Hara–Rudy dynamic model; BPS2020, Bartolucci-Passini-Severi model as published in 2020; bpm, beats per minute.

Comparison of the APs obtained under baseline conditions and upon 50%

hypernatremia without ion current scaling with those obtained during 50%

hypernatremia with and without cell shrinkage (Fig. 10A,G) reveals that the

hypernatremia-induced AP prolongation is largely determined by the ion current

scaling, which includes scaling factors of 0.6, 0.5, and 0.333 for each of the

repolarizing currents I, I, and I, respectively (Table 2).

Similarly, a comparison of the intracellular ion concentrations obtained under

the different conditions (Fig. 10B–D,H–J) shows that the changes in

[Ca], [K], and [Na] are largely, but

certainly not completely, determined by the cell shrinkage. In particular, in the

case of [Na] (Fig. 10D,J), the ion current scaling has a strong

effect. For example, in the ToR–ORd model, the hypernatremia induces an increase

in [Na] from its baseline value of 12.6 mmol/L to 24.7 mmol/L in the

presence of the ion current scaling, which is a substantially smaller increase to

17.7 mmol/L in the absence of the ion current scaling (Fig. 10J). This effect is

not highly surprising, given the hypernatremia-induced decrease in I and

increase in I (Table 2), which correspond to a reduced activity of the

Na–K pump and an enhanced activity of the Na–Ca

exchanger, respectively, both of which tend to increase [Na], in the

presence of the ion current scaling. The hypernatremia-induced decrease in

I and increase in I are not immediately apparent from a direct

comparison of the I traces in Fig. 10E,K and the I traces in

Fig. 10F,L. However, it should be noted that I and I depend on

the intracellular ion concentrations, which reached different levels under the

four conditions tested.

4. Discussion

4.1 Effects of Acute Hypernatremia on the Cellular Action Potential

Owing to the many effects of acute hypernatremia and the associated cell

shrinkage and changes in intracellular ion concentrations on individual membrane

currents, it is difficult to predict, if not qualitatively, then at least

quantitatively, how acute hypernatremia will affect the ventricular AP. This is

where comprehensive computer models of the ventricular cardiomyocyte come into

play. With such models, it is possible to determine and understand the effects of

different levels of acute hypernatremia on the individual membrane currents and

their net effects on the ventricular AP. In the present study, we used two

different comprehensive computer models of an isolated human ventricular

cardiomyocyte to assess the effects of mild to extreme hypernatremia on the

electrophysiology of such a cardiomyocyte. We observed a hyperpolarization of the

RMP, a prolongation of the AP, an increase in (dV/dt), and an

increase in I at all levels of hypernatremia. The magnitude of these

effects increased with increasing levels of hypernatremia.

Experimental data on the cardiac effects of acute hypernatremia at the cellular

level are scarce. What we do know from the work of Bou-Abboud and Nattel [37] is

that canine Purkinje fibers show small but statistically highly significant

increases in their APD (+12.0%) and APD (+5.4%) and in their

(dV/dt) (+4.7%) when [Na] is increased from 141 to 161

mmol/L (14% hypernatremia). Our simulation results at 10–20% hypernatremia,

albeit for human ventricular cardiomyocytes rather than canine Purkinje fibers,

correlate well with these experimental observations. More experimental data have

been obtained on the effects of hyperosmotic extracellular solutions on the AP of

cardiac myocytes at the cellular level, although these were obtained with

sucrose-induced hyperosmosis rather than hypernatremia. From the 1997 study by

Ogura et al. [20], we know that guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes,

when stimulated at 1 Hz, show an increase in APD of 10 3% (mean

SEM, n = 4) and 11 2% (n = 5) in 20% and 50%

hyperosmotic solutions, respectively. In a more recent study, also using guinea

pig ventricular cardiomyocytes stimulated at 1 Hz, Ogura et al. [22]

observed a 16.7 2.4% increase in APD (mean SEM,

n = 5) in a 50% hyperosmotic solution as well as a 6.6 0.2 mV

hyperpolarization of the RMP. Qualitatively, such an increase in [K]

is supported by the –2.8 0.3 and –7.3 0.7 mV (mean SEM,

n = 9) hyperpolarizing shifts in the I reversal potential for

30% and 80% hyperosmotic solutions [23]. Although obtained with guinea pig

rather than human ventricular cardiomyocytes and with a sucrose-induced

hyperosmotic extracellular solution rather than a hypernatremic one, these

experimental data on AP prolongation and RMP hyperpolarization correlate well

with our simulation results. One would expect hyperosmosis and hypoosmosis to

have opposite effects on APD, and this is indeed the case. Both Groh et

al. [38] and Kocic et al. [39] found a decrease in APD in guinea

pig ventricular cardiomyocytes upon hypoosmosis.

Ogura et al. [22] attributed the hyperpolarization of the RMP to an

increase in [K] in the osmotically shrunken cardiomyocytes, as also

proposed by Missan et al. [23]. This is supported by our simulation

results, which show an increase in both models. The increase in [K]

is even quantitatively very similar in the two models, which is, however, less

the case for the absolute increase in [Na]. In this regard, we have

to note that there is already a substantial difference in [Na]

between the two models at baseline, in contrast to the baseline level of

[K]. For example, at 75 bpm, [Na] is 12.6 mmol/L in the

ToR–ORd model and 6.6 mmol/L in the BPS2020 model. These values increase to 24.7

and 12.8 mmol/L, respectively, with 50% hypernatremia. Thus, a near doubling of

[Na] can be observed in both models.

4.2 Experimental Data on the Effects of Acute Hypernatremia on

Individual Ion Currents

As mentioned in the Introduction, data on the direct effects of acute

hypernatremia on individual membrane currents of cardiac myocytes are lacking.

Data on changes in individual membrane currents of single cardiac myocytes that

are acutely exposed to hyperosmotic solutions induced by the addition of sucrose

or mannitol rather than hypernatremia are not equivocal, particularly in the case

of I. This is even more the case when data on hypoosmosis are considered.

One would expect hyperosmosis and hypoosmosis to have opposite effects on

individual ion currents, yet this is not always the case. From the data

summarized in Table 1, one would expect an increase in both I and I

upon hypoosmosis, while I is unaffected. Groh et al. [38]

reported no significant changes in I or I in guinea pig ventricular

cardiomyocytes exposed to a 20% hypoosmotic solution, whereas I increased

(as expected) by 40%. Kocic et al. [39] also observed an

increase in I. The application of a 70% hypoosmolar bath solution by

Sasaki et al. [26] increased I (as expected), whereas no

noticeable change in I was observed, which was in agreement with their

observations with a 130% hyperosmolar solution. Furthermore, Rees et

al. [40] provided evidence that cell swelling enhanced I (as expected)

while inhibiting (rather than increasing) I. Thus, these data on I

and I in response to hypoosmosis are entirely consistent with the data in

response to hyperosmosis. However, the data on I are not: I is

either increased, decreased, or unaffected by hypoosmosis.

From the data summarized in Table 1, one would also expect a decrease in

I and an increase in I in response to hypoosmosis. In about half

of their cells, Sasaki et al. [26] observed a large increase in

I upon superfusion with a hypoosmolar bath solution, consistent with

their observations with a 130% hyperosmolar solution. Whalley et al.

[25] also observed stimulation of the Na–K pump during exposure to

hypoosmolar solutions, consistent with their observations with hyperosmolar

solutions. Wright et al. [29] showed a decrease in I in

response to 1.3-fold hypoosmotic treatment, consistent with their observations

with hyperosmolar solutions. Thus, all of these data on I and I

in response to hypoosmosis are consistent with the data in response to

hyperosmosis.

There are also some data on I in response to hypoosmosis. Groh

et al. [38] reported no significant changes in I (measured with

10 mmol/L EGTA in the pipette solution) in guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes

exposed to a 20% hypoosmotic solution. Similarly, Sasaki et al. [26]

observed no apparent change in I (measured with 5.0 mmol/L EGTA or 10

mmol/L BAPTA) upon application of a 70% hypoosmolar bath solution, in agreement

with their observations with a 130% hyperosmolar solution. Thus, these data on

I in response to hypoosmosis support the hyperosmosis data of Ogura

et al. [20] and Sasaki et al. [26] rather than those of Luo

et al. [27].

Unfortunately, experimental data on the effects of hyperosmosis, let alone

hypernatremia, on individual membrane currents are limited to the currents listed

in Tables 1,2. Most importantly, there are no data on the effects of

hyperosmosis on I and I. If such data had been available, we would

have incorporated these into our models. Experimental data on the effects of

hyperosmosis on intercellular coupling are also lacking, making conduction

studies in strand or tissue models uncertain.

4.3 Experimental Data on the Effects of Acute Hypernatremia on the

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

There are not many systematic studies of the effects of acute hypernatremia on

the ECG. In a study of seven anesthetized dogs, Eliakim et al. [41]

regularly observed bradycardia, a decrease in P wave amplitude, an increase in

QRS complex amplitude, and QT prolongation after intravenous administration of

hypertonic saline to induce acute hypernatremia. Gibson et al. [42]

studied ECG changes in 14 anesthetized dogs upon intravenous infusion of sodium

chloride (increase in serum Na levels of 28–56%, averaging 41%) and

consistently observed an increase in the rate-corrected QT interval (3–26%,

averaging 11%) and a decrease in the amplitude of the P wave and the QRS

complex, without QRS prolongation, and with variable minor changes in rate and

negligible changes in PR interval. Importantly, these ECG changes occurred with

only a 5–15% increase in serum Na levels, and only one dog presented an

arrhythmia, which was transient and occurred at the start of the infusion. In a

study of 20 rabbits subjected to extreme acute hypernatremia,

electrocardiographic tracings remained normal until respiratory arrest, “except

in a few instances in which peaked T waves were observed in the terminal stages”

[43]. Overall, these in vivo data from laboratory animals are

inconsistent, except perhaps for increased QT prolongation. The inconsistencies

may be related, at least in part, to the level of hypernatremia and a reduction

in P and QRS amplitude due to alterations in blood conductivity with a

short-circuiting effect on myocardial potentials, as discussed by Gibson

et al. [42], although this cannot fully explain the conflicting data. An

increase in QT prolongation is consistent not only with the increase in APD that

was observed in vitro (see Section 4.1) and that we observed in

silico (Fig. 8C,D) but also with clinical and experimental ECG data in case

reports of the effects of (often extreme) acute hypernatremia, including a

prolonged rate-corrected Q-U interval in a 12-year-old girl [44], QT prolongation

in an 11-year-old girl [9], and QT prolongation in a 29-year-old woman [8].

4.4 Intracellular Ca Concentration And Contractile

(dys)function

Hypernatremia may also lead to left ventricular (LV) contractile dysfunction. In

a prospective cohort study of subarachnoid hemorrhage patients, Fisher et

al. [6] observed that hypernatremia was an independent predictor of a reduced LV

ejection fraction of 50%. In line with this observation, King et al.

[45] demonstrated that elevating [Na] from 145 to 155 mmol/L in

Langendorff-perfused isolated rat heart preparations decreased LV developed

pressure (LVdP). Fisher et al. [6] hypothesized that the elevated

[Na] causes more Ca to exit the cell via the sarcolemmal

Na–Ca exchanger, which then results in reduced levels of

[Ca] available for cardiac myocyte contraction, thus causing a

negative inotropic effect. On the other hand, hypernatremia ranging from 163 to

218 mmol/L in 10 anesthetized dogs resulted in statistically significant

increases in cardiac output, heart rate, and maximum rate of rise in LVdP in the

study by Goodyer et al. [46].

The increase in the systolic peak amplitude of [Ca] that we found

in our simulations is consistent with the findings of Goodyer et al.

[46], especially when we compare the peak amplitude of [Ca] obtained

at 20–50% hypernatremia and a beating rate of 75–100 bpm with the baseline

peak [Ca] at 50 bpm to account for the increase in heart rate that

accompanies the hypernatremia. At 10% hypernatremia, which best reflects mild

hypernatremia, our simulations still predict an increase in peak

[Ca], although less pronounced, which seems to contradict the

observations of Fisher et al. [6] and King et al. [45] that

mild hypernatremia impairs LVdP. This may indicate a shortcoming in our models;

however, it may also point to a negative effect on the contractile apparatus that

requires a higher increase in peak [Ca], as obtained at 20–50%

hypernatremia, to be compensated. Notably, the hypothesis of Fisher et

al. [6] regarding a hypernatremia-induced reduction in the level of

[Ca] available for cardiac myocyte contraction is not supported by

our simulations.

In our simulations, there is an increase in peak [Ca] at all levels

of hypernatremia, yet it is most prominent at 50% hypernatremia. For example, in

the BPS2020 model, with a beating rate of 75 bpm, the peak [Ca] is

0.704 µmol/L at 50% hypernatremia compared to 0.412

µmol/L at baseline (+71%; Fig. 2D). Yet, the associated changes in

I and I do not seem to be large enough to explain this increase

in [Ca] fully. Early in the AP, there is an increase in reverse mode

I, making more Ca ions enter the cell, but on the other hand,

there is a decrease in peak I (Fig. 2F,K). In this regard, it should be

noted that the increase in [Ca] with increasing levels of

hypernatremia is largely due to the associated decrease in cell volume. The free

Ca ions reside in a 32% smaller myoplasmic volume compared to baseline,

which per se results in a 47% increase in [Ca]. Thus, even

a reduced amount of Ca ions entering the cell or released from the

sarcoplasmic reticulum can still increase [Ca].

4.5 Clinical Settings

It should be noted that in all of the above, the focus is on acute

hypernatremia, with the associated abrupt cell shrinkage; however, the more

common hypernatremia in the clinic is a more gradually developing and chronic

hypernatremia. In this context, the changes in intracellular volume and

osmolarity and those in individual membrane currents will be much smaller. It is

likely that, as a consequence, the effects of this type of hypernatremia will be

much less pronounced than in our simulations. Unfortunately, there are no

cellular electrophysiological data on this type of hypernatremia to support this

hypothesis. Furthermore, in the clinical management of the more gradually

developing hypernatremia, it is important to consider not only the absolute level

of the serum Na concentration but also the time of development of the

hypernatremia because too slow or too rapid corrections of the hypernatremia are

both associated with a poor patient prognosis [47, 48].

Another point of attention is the extreme 50% hypernatremia we used in our

simulations. Such a high level of hypernatremia is clinically limited to a few

cases reported worldwide [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] and some of the cases in the commonly

referenced study by Finberg et al. [49], in which they describe the

dramatic mix-up of salt and sugar in the preparation of feedings that were

received by 14 hospitalized infants, six of whom died. The highest level of

Na observed in the latter study was as high as 274 mmol/L (with a non-fatal

outcome).

4.6 Limitations

Our computer simulations were performed using the default versions of the

ToR–ORd and BPS2020 models. It should be noted that both models represent

endocardial cardiomyocytes with their default settings. However, epicardial and

mid-myocardial versions of each model are also available. In both models,

changing the cell type affects the kinetics and the amplitude of I, the

amplitude of I, I, I, I, I, I,

I, and I, and parameters related to the uptake and release of

Ca ions by the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Given the highly similar simulation

data obtained using the two models, despite differences in the amplitude and

kinetics of individual ion currents, it is highly unlikely that substantially

different simulation results will be obtained when repeating our simulations with

the epicardial or mid-myocardial versions of each model.

It should be recognized that experimental data on the effects of acute exposure

to a hyperosmotic solution on individual cardiac ion currents are scarce and

obtained at different levels of hyperosmolarity (Table 1), so we had to estimate

several of the values for use in our simulations (Table 2). We did this using

linear interpolation and extrapolation, which we considered the best possible

option. However, there is no evidence that the observed changes in individual ion

currents are actually linearly dependent on the level of hyperosmolarity over the

range studied.

One might anticipate cell shrinkage to affect the membrane capacitance. However,

Ogura et al. [22] carried out specific experiments on this issue in

which the membrane capacitance of seven guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes was

monitored during sequential superfusion with control, 50% hyperosmotic, and 50%

hypoosmotic solutions (varying sucrose levels). The superfusion with the

anisosmotic solutions caused cell shrinkage and swelling but did not affect the

membrane capacitance. Based on the experimental data of Ogura et al.

[22], we did not change the membrane capacitance in our simulations of

hypernatremia. However, it may well be that human ventricular cardiomyocytes show

a change in membrane capacitance upon acute hypernatremia that we have not

accounted for in our simulations.

It should be noted that our study is limited to the electrophysiological effects

of acute hypernatremia on a single ventricular cardiomyocyte (for which

experimental data on the effects of the hyperosmolarity are available, as

summarized in Table 1). As such, it is difficult to predict the effects of acute

hypernatremia on the tissue or whole-heart level from our simulations. For that,

data are required on the effects of acute hypernatremia on other cell types

(sinoatrial, atrial, atrioventricular, Purkinje) and intercellular coupling.

It can be argued that hypernatremia-induced cell shrinkage affects

stretch-activated ion channels in the cell membrane, thereby affecting the AP and

ion flow across the cell membrane. However, although very comprehensive, the two

models we used do not include stretch-activated channels. To overcome this

limitation, we should have implemented the various stretch-activated ion channels

in the two models and calibrated the resulting extended models to experimental

data, as was recently performed for the ToR–ORd model by Buonocunto et

al. [50].

Both hypoosmotic and hyperosmotic stress can induce the cardiac T-tubules to

seal, which could dramatically alter the Ca handling and AP propagation

[51], although this was not considered in our study. However, this sealing is a

threshold-dependent process, as observed by Uchida et al. [52] in a

study on isolated mouse left ventricular cardiomyocytes. In the case of

hyperosmolarity induced by the addition of extra NaCl to the extracellular

Tyrode’s solution, the threshold for the sealing effect is at a hyperosmolarity

of 65 mOsm/L [52], i.e., at 22% hypernatremia.

This suggests that our simulation results obtained at hypernatremia levels

20% should be considered with some caution regarding the potential role of

T-tubular sealing.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Fig. 9.

Fig. 9. Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.