1 Department of Cardiology, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Peking Union Medical College & Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, 100037 Beijing, China

2 Department of Cardiology, Dongguan Cardiovascular Research Institute, Dongguan Songshan Lake Central Hospital, Guangdong Medical University, 523770 Dongguan, Guangdong, China

3 Fuwai Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, 510000 Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Despite the administration of timely reperfusion treatment, patients with acute myocardial infarction have a high mortality rate and poor prognosis. The potential impact of intraluminal imaging guidance, such as optical coherence tomography (OCT), on improving patient outcomes has yet to be conclusively studied. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective cohort study to compare OCT-guided primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) versus angiography-guided for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

This study enrolled 1396 patients with STEMI who underwent PCI, including 553 patients who underwent OCT-guided PCI and 843 patients who underwent angiography-guided PCI. The clinical outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, admission due to heart failure, stroke, and unplanned revascularization at the 4-year follow-up.

The prevalence of major adverse cardiovascular events in OCT-guided group was not significantly lower compared to those without OCT guidance after adjustment (unadjusted hazard ratio (HR), 1.582; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.300–1.924; p < 0.001; adjusted HR, 1.095; adjusted 95% CI, 0.883–1.358; p = 0.409). The prevalence of cardiovascular death was significantly lower in patients with OCT guidance compared to those without before and after adjustment (unadjusted HR, 3.303; 95% CI, 2.142–5.093; p < 0.001; adjusted HR, 2.025; adjusted 95% CI, 1.225–3.136; p = 0.004).

OCT-guided primary PCI used to treat STEMI was associated with reduced long-term cardiovascular death.

Keywords

- optical coherence tomography

- ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- outcomes

- angiography

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is an intravascular imaging modality based on infrared light imaging [1], which has greater resolution than intravascular ultrasound, providing more advantages for evaluating plaque morphology and the immediate effect of stent deployment [2]. Compared with coronary angiography-guided percutaneous coronary intervention, OCT-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) results in a larger minimum stent area and reduces the incidence of coronary dissection and stent malposition [3]. OCT provides clearer images of plaque characteristics than other intravascular modalities, such as intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). However, both OCT- and IVUS-guided PCI can improve patient prognoses compared with coronary angiography [4, 5]. OCT-guided PCI offers no significant improvement over IVUS-guided PCI in decreasing the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) at 1 year [6], including in guiding interventions for complex coronary lesions [7]. However, the incidence of major procedural complications is significantly lower among patients undergoing OCT-guided treatment than those undergoing IVUS-guided treatment [6].

Nevertheless, the impact of OCT guidance on the long-term prognosis of patients remains controversial among different studies. Previous clinical investigations have demonstrated that using OCT in PCI significantly reduces MACEs, cardiovascular death, and revascularization [8], especially in complex coronary artery disease [4, 9]. However, using OCT-guided PCI for non-complex lesions did not significantly differ from using angiography guidance in clinical outcomes at 12 months [3]. However, more dedicated studies are needed to confirm the superiority of OCT over coronary angiography. Therefore, this study explored whether OCT examination can improve the prognosis of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients. In this study, long-term clinical outcomes were compared between patients who received PCI treatment under OCT guidance and those who received PCI treatment under angiography guidance in a retrospective cohort.

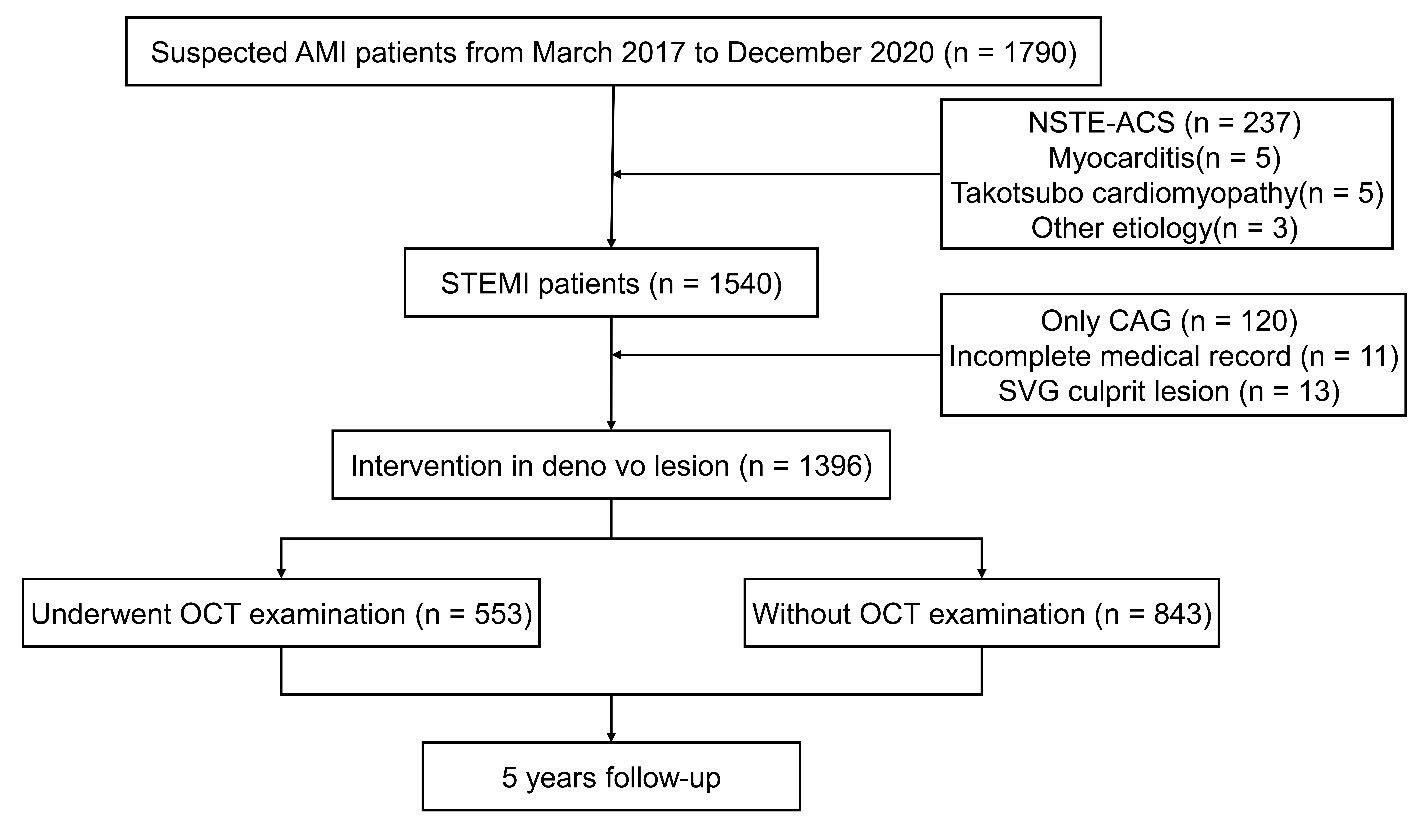

This retrospective study consecutively enrolled 1790 suspected acute myocardial

infarction (AMI) patients from March 2017 to December 2020 at Fuwai Hospital

(Beijing). Patients aged 18 years or older who underwent emergent coronary

angiography due to an AMI diagnosis (symptom onset

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; NSTE-ACS, non ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; CAG, coronary angiography; SVG, saphenous vein graft; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

Patients were administered 300 mg of aspirin, 180 mg of ticagrelor, 600 mg of clopidogrel, and 100 IU/kg heparin before the interventional procedure. The percutaneous coronary intervention was performed via radial or femoral access. The decision to conduct an OCT examination before or after stenting depended on the judgment of the operator and the condition of the patient. Thrombus aspiration reduced the thrombus burden and restored antegrade coronary flow. After antegrade blood flow was restored, OCT images of the culprit lesions were acquired using the frequency domain ILUMIEN OPTIS OCT system and a dragonfly catheter (St. Jude Medical, Westford, MA, USA), according to a previously described intracoronary imaging technique [11]. Three independent investigators analyzed all anonymized OCT images and other data using a St Jude OCT Offline Review Workstation. The definitions of pre- and post-interventional OCT characteristics are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Continuous data are presented as the mean

The baseline characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1. Patients in the group without OCT guidance were more likely to be older, and this group had a greater proportion of patients with previous myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and chronic kidney disease. These patients also had higher creatinine, NT-proBNP, and Killip II–IV levels and lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) levels. The OCT-guided group had a greater proportion of anterior wall myocardial infarction, larger implanted stents, and higher application rates of aspirin, statin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB) use than the group without OCT guidance.

| Variables | Total (n = 1396) | OCT guidance | p-value | |||

| With (n = 553) | Without (n = 843) | |||||

| Demographic data | ||||||

| Age (years) | 60.2 |

58.2 |

61.6 |

|||

| Males | 1134 (81.2%) | 464 (83.9%) | 670 (79.5%) | 0.038 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9 |

26.0 |

25.8 |

0.316 | ||

| Risk factors | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 459 (32.9%) | 163 (29.5%) | 296 (35.1%) | 0.028 | ||

| Hypertension | 888 (63.6%) | 333 (60.2%) | 555 (65.8%) | 0.033 | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 1249 (89.5%) | 499 (90.2%) | 750 (89.0%) | 0.451 | ||

| Ischemic stroke | 188 (13.5%) | 57 (10.3%) | 131 (15.6%) | 0.005 | ||

| Previous MI | 217 (15.5%) | 55 (9.9%) | 162 (19.2%) | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | 98 (7.0%) | 19 (3.4%) | 79 (9.4%) | |||

| Smoker | 1003 (72.2%) | 410 (74.4%) | 593 (70.7%) | 0.129 | ||

| Clinical indicator | ||||||

| Killip II–IV level | 191 (13.7%) | 44 (8.0%) | 147 (17.4%) | |||

| LVEF (%) | 53.3 |

54.5 |

52.5 |

|||

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 6.2 (2.2–11.0) | 5.9 (2.4–10.8) | 6.6 (2.1–11.1) | 0.260 | ||

| Creatinine (mmol/L) | 89.6 |

84.6 |

92.8 |

|||

| HbA1c (%) | 6.7 |

6.6 |

6.7 |

0.278 | ||

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.4 (1.0–2.1) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 0.099 | ||

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.7 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

0.889 | ||

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.165 | ||

| c-TnI (ng/mL) | 1.0 (0.1–5.3) | 0.9 (0.1–4.7) | 1.1 (0.1–6.0) | 0.013 | ||

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 262.4 (65.8–922.6) | 191.7 (50.4–579.1) | 311.7 (87.4–1265.3) | |||

| Anterior wall infarction | 639 (45.8%) | 275 (79.4%) | 364 (43.2%) | 0.016 | ||

| Angiographic data | ||||||

| Culprit lesion | 0.003 | |||||

| LM | 9 (0.6%) | 0 (0) | 9 (1.1%) | |||

| LAD | 639 (45.8%) | 275 (49.7%) | 364 (43.2%) | |||

| LCX | 181 (13.0%) | 57 (10.3%) | 124 (14.7%) | |||

| RCA | 567 (40.9%) | 221 (40.0%) | 346 (41.0%) | |||

| AHA lesion type | 0.063 | |||||

| A | 30 (2.1%) | 8 (1.4%) | 22 (2.6%) | |||

| B1 | 144 (10.3%) | 51 (9.2%) | 93 (11.0%) | |||

| B2 | 277 (19.8%) | 98 (17.7%) | 179 (21.2%) | |||

| C | 945 (67.7%) | 396 (71.6%) | 549 (65.1%) | |||

| Lesion length | 23.0 (16.0–32.0) | 25.0 (18.0–34.0) | 22.0 (15.0–30.0) | |||

| Lesion diameters | 3.0 (2.5–3.5) | 3.0 (2.8–3.5) | 2.8 (2.5–3.3) | |||

| Stenosis (%) | 96.8 |

96.7 |

96.9 |

0.642 | ||

| Pre-intervention TIMI 0 | 888 (63.6%) | 356 (64.4%) | 532 (63.1%) | 0.630 | ||

| Multivessel lesion | 1039 (74.4%) | 400 (72.3%) | 639 (75.8%) | 0.146 | ||

| Stent diameters | 3.1 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

|||

| Stent length | 30.4 |

31.7 |

29.4 |

0.010 | ||

| Thrombus aspiration | 538 (38.5%) | 297 (53.7%) | 241 (26.8%) | |||

| Pre-dilatation | 1274 (91.3%) | 480 (86.8%) | 794 (94.2%) | |||

| Post-dilatation | 1160 (83.1%) | 504 (91.1%) | 656 (77.8%) | |||

| Post-intervention TIMI | ||||||

| 0 | 20 (1.4%) | 0 (0) | 20 (2.4%) | |||

| 1 | 8 (0.6%) | 0 (0) | 8 (0.9%) | |||

| 2 | 26 (1.9%) | 4 (0.7%) | 22 (2.6%) | |||

| 3 | 1342 (96.1%) | 549 (99.3%) | 793 (94.1%) | |||

| Discharge medication | ||||||

| Aspirin | 1330 (95.3%) | 537 (97.1%) | 793 (94.1%) | 0.009 | ||

| Ticagrelor | 693 (49.6%) | 293 (53.0%) | 400 (47.4%) | 0.043 | ||

| Clopidogrel | 683 (48.9%) | 258 (46.7%) | 425 (50.4%) | 0.169 | ||

| ACEI/ARB | 1003 (71.8%) | 419 (75.8%) | 584 (69.3%) | 0.008 | ||

| 1205 (86.3%) | 492 (89.0%) | 713 (84.6%) | 0.020 | |||

| Statin | 1320 (94.6%) | 536 (96.9%) | 784 (93.0%) | 0.002 | ||

Continuous data are presented as the mean

The OCT characteristics are shown in Supplementary Table 1. A total of 538 (97.3%) patients underwent pre-interventional OCT examinations, while 275 (49.7%) underwent post-interventional OCT examinations. Among the patients with pre-intervention OCT images, 191 (35.5%) were diagnosed with plaque rupture, 173 (32.2%) with plaque erosion, and 18 (3.3%) with calcified nodules. Twelve (2.2%) patients were categorized as having coronary spasms, embolism, or severe stenosis. Forty-one (7.6%) patients were diagnosed with stent thrombosis. However, the plaque phenotypes of 103 (19.1%) patients remained undetermined because massive thrombi overlapped with the underlying plaque. Among the 275 patients who underwent post-intervention OCT, 151 (54.9%) exhibited plaque prolapse, and 113 (41.1%) had stent malapposition; these patients underwent post-dilatation. Additionally, stent edge dissection was found in 38 patients (13.8%).

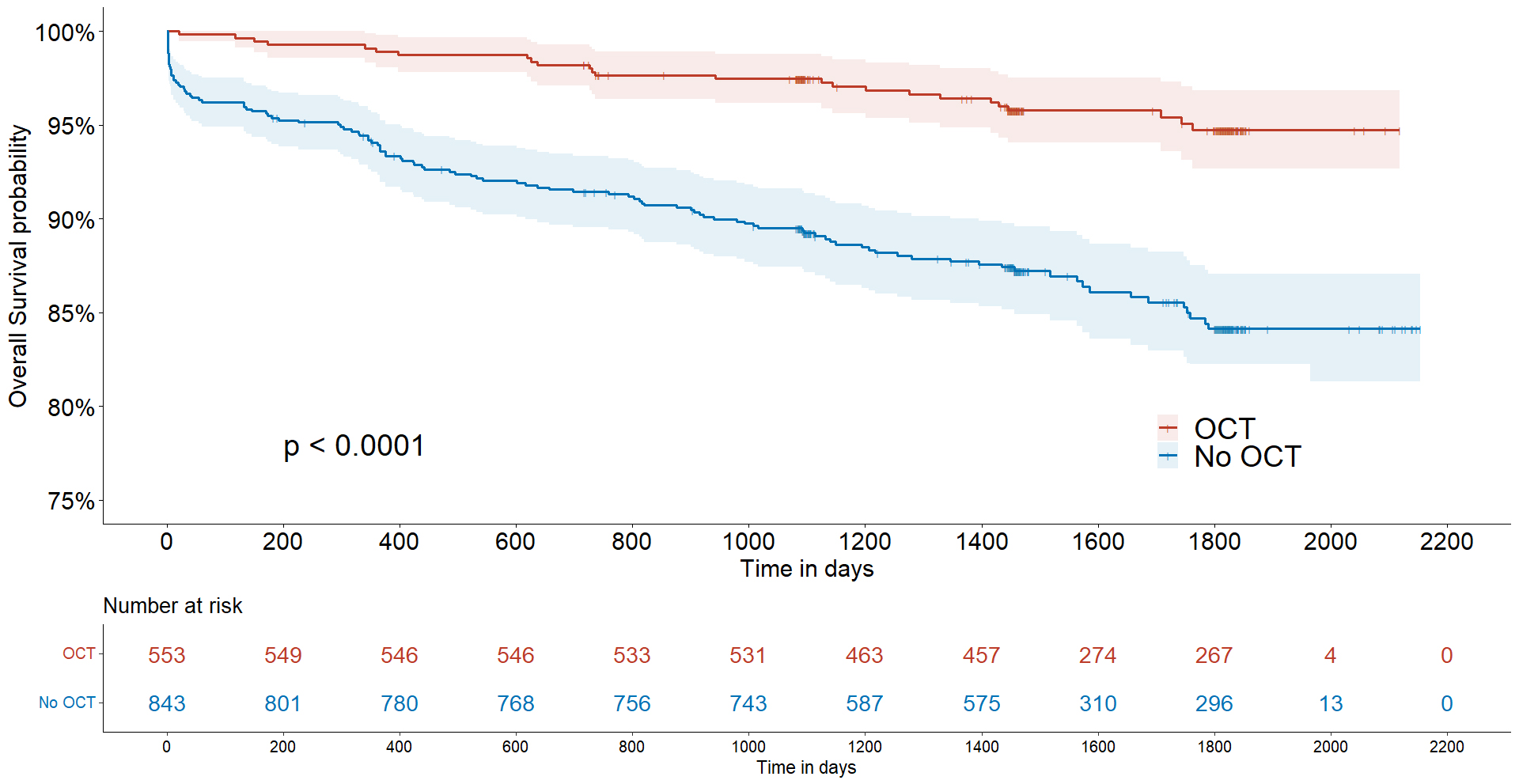

During follow-up, the prevalence of MACEs, including cardiovascular death,

myocardial infarction, admission due to heart failure, stroke, and unplanned

revascularization, was significantly lower in patients with OCT guidance compared

to those without OCT guidance (hazard ratio (HR): 1.582; 95% confidence interval

(CI): 1.300–1.924; p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves in patients with and without OCT guidance. OCT, optical coherence tomography.

| Endpoint | Unadjusted (95% CI)* | p-value | Model 1 (95% CI)* | p-value | Model 2 (95% CI)* | p-value | Model 3 (95% CI)* | p-value | |

| MACEs composite | 1.582 (1.300–1.924) | 1.514 (1.243–1.844) | 1.412 (1.156–1.724) | 1.095 (0.883–1.358) | 0.409 | ||||

| Death | 3.303 (2.142–5.093) | 2.588 (1.670–4.010) | 2.372 (1.525–3.691) | 2.025 (1.225–3.136) | 0.004 | ||||

| MI | 1.254 (0.761–2.067) | 0.374 | 1.202 (0.727–1.989) | 0.473 | 1.049 (0.630–1.747) | 0.853 | 0.989 (0.575–1.702) | 0.969 | |

| HF | 1.994 (1.030–3.863) | 0.041 | 1.914 (0.985–3.720) | 0.055 | 1.735 (0.883–3.411) | 0.110 | 1.305 (0.630–2.704) | 0.473 | |

| Stroke | 1.326 (0.821–2.142) | 0.248 | 1.285 (0.794–2.082) | 0.308 | 1.145 (0.702–1.865) | 0.588 | 0.985 (0.587–1.650) | 0.953 | |

| Revascularization | 1.224 (0.943–1.589) | 0.129 | 1.227 (0.943–1.595) | 0.127 | 1.139 (0.873–1.487) | 0.337 | 1.079 (0.814–1.430) | 0.596 | |

Model 1: adjusted for age and sex; Model 2: adjusted for all factors in model 1 plus diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, previous myocardial infarction, chronic kidney disease; Model 3: adjusted for all factors in model 2 plus Killip level, creatine, c-TnI, NT-proBNP, lesion diameter and length, AHA lesion types, thrombus aspiration, left ventricle ejection fraction, and anterior wall infarction. * Hazard ratio (with OCT guidance vs. without OCT guidance). MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; OCT, optical coherence tomography; MI, myocardial infarction; HF, heart failure; c-TnI, cardiac troponin I; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; AHA, American Heart Association.

In this retrospective cohort study, we first demonstrated that patients with STEMI who underwent OCT-guided primary PCI experienced better clinical outcomes, particularly a lower incidence of cardiovascular death, than those who did not receive OCT guidance. These findings provide evidence supporting the superiority of intravascular imaging in treating critical coronary patients.

Compared with intravascular ultrasound, OCT is a more recent imaging modality characterized by superior resolution and greater accuracy in differentiating and characterizing plaque phenotypes, thereby providing more precise stratification and treatment [12]. Moreover, intravascular imaging guidance of coronary stent implantation with either OCT or intravascular ultrasound enhances the safety and effectiveness of PCI [8, 13]. Furthermore, OCT imaging has been shown to be safe, with a previous study revealing that OCT did not increase periprocedural complications, type 4a myocardial infarction, or acute kidney injury [14]. However, the impact of OCT examination on the long-term clinical outcomes of patients through the guidance of interventional treatment remains limited [6]. A prospective cohort study including 214 patients who underwent OCT-guided primary PCI revealed no significant reduction in clinical events with or without OCT guidance at 1 year [15]. A recent prospective, randomized, single-anonymized trial with 1233 patients assigned to undergo OCT-guided PCI demonstrated no apparent difference in the percentage of patients with target-vessel failure at 2 years [4]. However, in patients with complex coronary artery lesions, intravascular OCT-guided PCI was associated with a lower risk of death from cardiac disorders, target vessel-related myocardial infarction, or clinically driven target vessel revascularization compared to angiography-guided PCI [16]. Moreover, comparisons of clinical outcomes demonstrated that OCT-guided PCI was non-inferior to IVUS [13, 17, 18]. In another comparative study, OCT-guided PCI of non-complex lesions did not significantly differ from IVUS or angiography guidance regarding clinical outcomes at 12 months [3]. A recent meta-analysis indicated that the estimated absolute effects of intravascular imaging-guided PCI were closely related to baseline risk, which is determined mainly by the severity and complexity of coronary artery disease [9]; however, studies on the long-term clinical outcomes of patients with STEMI who undergo OCT-guided primary PCI are lacking.

In the present study, patients at high risk were not selected for OCT examination, which was performed by an interventional operator who considered factors such as hypotension, malignant arrhythmia, or poor vessel condition. Indeed, a higher Killip level, lower LVEF, and poorer renal function were significantly more common in patients without OCT detection. Moreover, patients in the OCT-guided group had significantly larger culprit lesions, including both length and diameter, than those without OCT guidance. However, the degree of stenosis, rate of thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) 0, and number of multivessel lesions were not significantly different between the two groups. However, after adjusting for these risk factors, the mortality rate for patients in the OCT-guided group remained lower than those without OCT guidance, suggesting that OCT guidance might benefit some patients. Interestingly, the length and diameter of stent implantation in the group with OCT examination were greater than those without OCT examination. This suggests that OCT guidance allowed for a more thorough evaluation of the lesional area, significantly improving stent expansion and coronary lesion coverage. OCT-optimized stent deployment significantly reduced the short-term in-segment area of stenosis [19]. The iSIGHT randomized trial revealed that stent expansion with OCT guidance was superior to an optimized angiographic strategy [17]. The principal mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of OCT guidance have been explored, including a greater minimal stent area, freedom from major edge dissections, and untreated focal reference segment disease [18]. Nevertheless, this research did not investigate the mechanism underlying the superiority of OCT-guided primary PCI in patients with STEMI, which requires further investigation.

A previous study demonstrated that pre-interventional OCT examination allows for developing a strategy by differentiating the plaque phenotype in patients with STEMI [12]. Moreover, pre- and post-interventional OCT guidance of PCI contributed to more precise treatment of culprit lesions [4]. The mechanisms in our study that supported improved prognoses in OCT-guided patients included plaque characterization, more accurate stent implantation, and remediation of immediate post-stenting complications. Intervention operators can obtain more useful information from OCT to guide stenting and postoperative antithrombotic therapy. However, our retrospective study could not differentiate the individual contributions of these factors, which need to be verified by randomized controlled trial in the future.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective, single-center cohort study with a moderate sample size. Second, some patients in the angiography group who could not undergo OCT examination due to high risk may have introduced selection bias. Third, some patients with multivessel lesions in our study underwent staged PCI with or without OCT guidance after discharge; however, this information was missing, meaning bias cannot be excluded. Fourth, most OCT images in this study were obtained from patients with large vessels—with diameters larger than 3 mm. Therefore, the effectiveness of OCT in relatively small vessels remains limited. Fifth, because the LVEF of patients was relatively high, the rate of recurrent myocardial infarction was low, which may be biased. Sixth, all patients underwent OCT examination only in their culprit lesion; thus, the plaque characteristics in their non-culprit lesion were unclear. Finally, the mechanism underlying the superiority of OCT-guided primary PCI was not investigated in detail. Hence, further large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate the impact of OCT guidance on clinical endpoints.

Our retrospective study provided evidence that OCT-guided primary PCI in patients with STEMI was associated with a significant reduction in long-term mortality compared with patients without OCT guidance; however, further confirmation of these data is required from prospective randomized studies.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

JNL, HBY and HJZ designed the research study. XLW and RZC performed the research. PZ and CL collected the data. YC and LS analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuwai Hospital (No. 2017-866) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided signed informed consent.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by the Fund of “Sanming” Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (number: SZSM201911017) and the Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund (number: SZXK001).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.rcm2512444.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.