1 School of Business, University of Skövde, 541 28 Skövde, Sweden

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to understand how small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) use intuitive decision-making in times of crisis. The study was conducted among retailing SMEs in Sweden. In total, 28 store managers were interviewed in 2021, while the COVID-19 pandemic was still ongoing. Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic forms an important context for this paper. Theoretically, the paper draws on intuitive decision-making, complemented by literature on crisis and organisational resilience (OR). The study finds that intuitive decision-making was common, particularly at the beginning of the pandemic—with store managers employing creative and problem-solving approaches to intuitive decision-making. The study thereby contributes to research on intuitive decision-making in a crisis context as well as to an understanding of the resilience of stores.

Keywords

- resilience

- intuitive decision-making

- SMEs

- Sweden

- COVID-19

Decision-making is a critical area of management research, with an increasing body of work indicating that most decisions are influenced by emotions (e.g., Alvesson and Spicer, 2012). Emotions vary significantly between individuals, cultures, and contexts, such as public versus private settings (Svenson et al, 2023). This paper specifically focuses on intuition, defined as “affectively charged judgments that arise through rapid, nonconscious, and holistic association” (Dane and Pratt, 2007, p. 33). This definition is widely recognized in the field of organizational research (Adinolfi and Loia, 2022).

In the context of family business research, the concept of socioemotional wealth has been introduced (Berrone et al, 2012; Gomez-Mejia et al, 2007), wherein decision-making in family firms is driven by the desire to preserve the socioemotional endowment of the owning family. This motivation can justify riskier decisions, as maintaining ownership of the business helps secure this endowment. Entrepreneurship literature has similarly highlighted the importance of intuition in entrepreneurial decision-making (Pina e Cunha, 2007). Pina e Cunha (2007) distinguishes between rational, intuitive, and improvisational decision-making among entrepreneurs, drawing from Mintzberg and Westley (2001) , who argue that effective decision-making extends beyond rationality to include intuitive and improvisational approaches. Research suggests that intuition is a key factor in entrepreneurial decision-making. For instance, Koudstaal et al (2019) found that entrepreneurs have a stronger belief in intuitive decision-making than managers or employees. However, the same study also noted that entrepreneurs value time for reflection, despite their frequent reliance on intuition. Additionally, Darby et al (2022) report that farmers often rely on a combination of intuitive decision-making and experience, a result of resource constraints. Another study finds that family firms utilize intuitive approaches in succession planning (Bloemen-Bekx et al, 2023). Thus, intuition has gained recognition in research on small businesses and family firms, where limited access to professional and theoretical tools may drive preferences for intuitive marketing strategies (Petrů et al, 2018).

The COVID-19 pandemic provides a unique context in which many firms, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), relied on intuitive decision-making processes, given the absence of crisis plans (Fasth et al, 2022). These firms were compelled to make decisions under significant uncertainty regarding the potential impact and outcomes. Sweden serves as an interesting case study, as the Swedish Public Health Authority, Folkhälsomyndigheten (FHM), adopted a distinct approach to managing the pandemic compared to other European countries (e.g., Anastasiadou et al, 2020; Boers and Henschel, 2022a; Kraus et al, 2020). Swedish authorities issued behavioral recommendations, appealing to individual responsibility to maintain social distancing, which stood in contrast to the stricter measures implemented in other European nations prior to the availability of a vaccine (Tegnell, 2021). Upon the introduction of a vaccine, public authorities strongly encouraged vaccination. A study from France examined the role of intuition in fostering belief in pseudo-scientific treatments for the pandemic (Fuhrer and Cova, 2020). The study found that vaccination attitudes were influenced by cognitive style, with individuals favoring an intuitive cognitive style being more likely to trust vaccine critics and those opposing vaccination. Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic offers a valuable context for examining intuitive decision-making.

The purpose of this study is to explore how SMEs employed intuitive decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings indicate that intuitive decision-making was prevalent during the early stages of the pandemic, characterized by high levels of uncertainty and insecurity in the absence of clear guidance or prior experience. Respondents utilized creative and problem-solving intuition to manage the pandemic’s consequences, thereby contributing to the literature on intuitive decision-making within crisis contexts. Furthermore, intuitive decision-making played a role in enhancing the resilience of the studied businesses.

The study proceeds by developing a theoretical framework, elaborating on the research methods, and presenting empirical findings. These findings are then discussed before concluding with theoretical and practical contributions, as well as recommendations for future research.

In their chronological review of intuition in management research, Akinci and Sadler-Smith (2012) identified Chester Barnard and Herbert Simon as early contributors to the understanding of intuition in managerial decision-making. A key criterion of intuitive decision-making is speed. In addition to intuition, various decision-making styles exist. Svenson et al (2021, p. 223) categorize these styles as intuitive or analytical thinking, heuristics, unconscious thought, and anticipation. Simon (2013; 1987) previously argued that decision-making is not purely rational but is constrained by the cognitive limitations of decision-makers (Acciarini et al, 2021). These cognitive limitations often result in biased decisions (Acciarini et al, 2021; Svenson et al, 2021).

Intuition is recognized as a multidimensional concept that has been studied from various perspectives (Koudstaal et al, 2019; Svenson et al, 2023). It has also been explored within the field of entrepreneurship (Kakkonen, 2005; Koudstaal et al, 2019), which Armstrong et al (2012) suggest requires further research. A widely accepted definition in the management literature is that proposed by Dane and Pratt (see Adinolfi and Loia, 2022). According to Dane and Pratt (2007, p. 33), intuition refers to “affectively charged judgments that arise through rapid, nonconscious, and holistic association”. They argue that intuition helps guide critical managerial decisions within organizational contexts and emphasize the importance of distinguishing between the intuitive process and its outcome. Specifically, the process is nonconscious, meaning it occurs outside of conscious thought (Dane and Pratt, 2007, p. 36). Additional characteristics of intuition include its rapid nature, its reliance on holistic associations, and its production of affectively charged judgments. More recent research has suggested that intuitive decision-making is based on pattern recognition (Svenson et al, 2023). According to Svenson et al (2023, p. 3), “Effectively managing intuition is presumably a base skill for wiser decision outcomes.” This highlights that intuitive decision-making can lead to wise outcomes, though it is not the only potential result. Simon (2013, p. 133) further asserts that intuition involves applying professional judgment to a situation, drawing upon prior experience and training to activate a knowledge base when decisions are made. Similarly, Mintzberg and Westley (2001) argue that rational decision-making is incomplete and must be complemented by intuitive and improvisational approaches for effectiveness. In certain situations, particularly when time is limited, it may be necessary to make quick, intuitive decisions. A crisis, for example, often demands rapid and intuitive decision-making.

Given this, the context in which decisions are made is essential to consider. This study focuses on the decision-making processes of store owners and managers in Sweden during the coronavirus pandemic, a context that can be classified as a crisis (Boers and Henschel, 2021; Boers and Henschel, 2022c). In early 2020, when COVID-19 first emerged in Sweden, FHM issued several recommendations regarding appropriate behavior. Notably, the FHM emphasized individual responsibility while strongly recommending vaccination once the vaccine became available (Raffetti et al, 2022).

Many of the businesses studied in this research can be classified as family firms, where intuitive decision-making is common, especially in the context of succession planning (Bloemen-Bekx et al, 2023). Intuition is viewed as particularly relevant for handling dilemmas or the inherent unpredictability of the succession process. Another study found that farmers use intuitive decision-making when deciding how to store their harvest (Darby et al, 2022). These farms, characterized by their resource constraints and small number of employees, are both SMEs and family-owned businesses. Thus, they embody characteristics common to both types of enterprises, further highlighting the relevance of intuitive decision-making in such contexts.

Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, SMEs have faced significant threats to their survival, particularly if they are unable to manage the crisis effectively. Crisis scenarios, such as the pandemic, are common contexts in which intuitive decision-making is utilized (Okoli and Watt, 2018; Okoli et al, 2023). The retail sector has been especially affected by the pandemic (Akram et al, 2021), with some scholars attributing this to disruptions in supply chains, upon which retail businesses heavily depend (Schleper et al, 2021). In response to these challenges, many firms have developed innovations to cope with the consequences of the crisis (Boers, 2023; Schleper et al, 2021).

The concept of resilience has gained prominence in recent years, particularly as crises increasingly affect organizations worldwide. The coronavirus pandemic, in particular, has been identified as a global crisis impacting enterprises on a large scale (Durst et al, 2021; Kraus et al, 2020). However, the effects of the pandemic on businesses have varied, as countries have adopted different strategies to mitigate the crisis. While some nations implemented strict measures, such as lockdowns and extensive regulations, others adopted more flexible approaches that emphasized individual responsibility, allowing companies to operate with fewer restrictions within a defined framework (Boers and Henschel, 2022a; Boers and Henschel, 2022b).

Resilience in organizations is closely linked to their ability to navigate crises and disruptive changes, and research on organizational resilience has expanded significantly in recent years (Linnenluecke, 2017). Managerial and leadership practices are key determinants of organizational resilience, influencing how effectively a company can respond to external crises (Gibson and Tarrant, 2010; Korber and McNaughton, 2018). For instance, organizations are better equipped to handle crises if their leaders remain attuned to their external environment and the unfolding changes (Gibson and Tarrant, 2010). In this context, decision-making processes undertaken by company leaders play a crucial role, especially when improvisation is required (Darkow, 2019; Rahi, 2019). Moreover, as a crisis evolves, managers must adapt, refine, and transform their leadership styles to navigate the shifting challenges (Vakilzadeh and Haase, 2021).

In situations involving unforeseen events, intuition serves as a valuable resource for decision-making. It is well-established that decision-makers often rely on both intuitive and analytical decision-making processes, which are not necessarily in opposition. Rather, these approaches can complement each other. However, questions remain regarding the sequence in which intuition and analysis should be applied (Okoli and Watt, 2018). In practice, even intuitive decisions often involve some degree of analysis, such as pattern recognition or matching.

The study employs a qualitative research design, as outlined by Eisenhardt and Graebner (2007), which is particularly well-suited for addressing “how” research questions. The focus of this study is on SMEs located in a region in South-West Sweden. Within this region, a municipal training center offers a range of educational opportunities, from individual courses to bachelor’s degree programs. The center collaborates with local businesses, providing students with the opportunity to conduct study-related projects, such as internships. In 2020, the training center issued a call for research projects in connection with its university programs. Specifically, this study follows a case study design, with the participating stores serving as the unit of analysis (Grünbaum, 2007). Qualitative interview studies on intuitive decision-making are relatively rare (Hensman and Sadler-Smith, 2011), likely due to the complex and implicit nature of uncovering intuitive decision-making processes (Guba and Lincoln, 1994; Hensman and Sadler-Smith, 2011; Mikušková, 2017).

Data collection was conducted in 2021, while the coronavirus pandemic was still ongoing in Sweden, which imposed limitations on data-gathering efforts. To adhere to public health restrictions and protect participants, the data collection relied on interviews with store managers (Appendix A), supplemented by additional materials such as annual reports, press releases, and content from company websites. The interviews were conducted via telephone, Skype, or Zoom. A standardized interview template (Appendix B) was used to guide the discussions and ensure consistency, as two researchers conducted the interviews independently. Conducting a study while the phenomenon is still unfolding, as in the case of the pandemic, allows the researchers to avoid the pitfalls of retrospective sense-making (Golden, 1992). The pandemic thus provides a unique context that has affected both individuals and organizations globally.

In collaboration with a contact person at the training center, a list of 82 stores in the region was identified. These stores had previously participated in various activities organized by the center. The training center contacted the stores via email, inviting them to participate in the research project. Ultimately, 28 stores agreed to participate, resulting in a response rate of approximately 34%. The interviews ranged in length from 17 to 70 minutes, with an average duration of about 30 minutes. The respondents were store managers, some of whom were also owners of their respective stores, while others were employed managers. The Table 1 below illustrates the types of managers interviewed in this study.

| Type | Number |

| Employed managers | 8 |

| Owner-managers | 20 |

| Sum | 28 |

Note. Source: The authors.

The majority of the firms involved in this study are classified as SMEs, where the store represents the firm and its operational activities. In contrast, the employed managers work for larger companies with more than 250 employees. However, the specific stores in this study had between 1 and 80 employees. Several of the companies operating these stores could be classified as family firms, which constitute the majority of firms in Sweden, particularly among SMEs (Andersson et al, 2018). All the firms sampled in this study are privately owned. Of the 28 firms, 13 could be categorized as family firms.

The primary focus of the interviews was on the store managers and their approaches to handling and managing the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, the stores, rather than the firms as a whole, were the unit of analysis in this study (Grünbaum, 2007). A detailed overview, including descriptive statistics of all the interviewed stores, can be found in Appendix A.

The pandemic placed significant responsibility on store managers, who were tasked with ensuring that the recommendations from FHM were followed. The FHM was responsible for communicating strategies to limit the transmission of COVID-19. However, Sweden primarily relied on voluntary compliance with these recommendations rather than enforcing mandatory restrictions (Tegnell, 2021). The pandemic represented an extraordinary period, altering behaviors globally. In Sweden, as in many other countries, the primary focus was on protecting vulnerable populations, particularly the elderly (Tegnell, 2021).

Before the development of a vaccine, numerous alternative treatments were proposed in various parts of the world (Fuhrer and Cova, 2020). In the retail sector, specific recommendations were made regarding the number of customers permitted per square meter within stores. A recent study classifies retail store responses to the pandemic as reactive and bottom-up, rather than proactive and top-down (Hultman and Egan-Wyer, 2022). Many retail stores adapted by making physical changes to their environments and introducing new services, such as home delivery.

There are multiple approaches to analyzing qualitative interview data, and it is important to acknowledge the central role of the researcher in this process (Miles et al, 2013). Below, we outline the approach used for this study. It should be noted that in qualitative research, data analysis begins early—starting from the formulation of research questions (Fletcher et al, 2016; Golden-Biddle and Locke, 1997) and continuing through the selection of interview quotes.

All interviews were transcribed, and the transcripts were analyzed by the authors using a thematic coding scheme. The key themes of interest for this paper included intuitive and wise decision-making. As the interviews generally focused on how stores had been impacted by the pandemic, many decision-making scenarios were discussed by the store managers during the interviews.

For the actual data analysis, NVivo software (Lumivero, Denver, CO, USA) was employed (Maher et al, 2018), which allowed for the combination, categorization, searching, and analysis of the qualitative data. Although the data was initially collected with the intention of understanding how store owners and managers handled the pandemic, it became clear through the review and analysis that decision-making, particularly intuitive decision-making, was a relevant aspect. As a result, the data was re-examined from the perspective of decision-making and intuition.

The work of Dane and Pratt (2009) provided inspiration for our analysis, specifically their distinction between problem-solving intuition, moral intuition, and creative intuition. Problem-solving intuition is based on pattern matching, moral intuition relates to ethical or moral content, and creative intuition involves viewing knowledge from new perspectives. All three forms of intuition are rooted in the experience and expertise of the decision-maker. In our analysis, we searched for quotes that illustrated intuitive decision-making, specifically within the context of handling the consequences of the pandemic.

Ultimately, we found evidence of problem-solving and creative intuition in the empirical material, but no clear examples of moral intuition. Table 2 below outlines the analytical procedure used in this study.

| Intuition type | Definition | Illustrative quote | Explanation |

| Problem-solving | Automatic acts of recognition due to pattern matching (Dane and Pratt, 2009, p. 5) | We brought shoes out to customers on the street and they could come early morning or late evening. (store manager 21) | This shoe store manager had to handle customer demands and restrictions from public authorities to continue the business. Therefore, they found solutions to these demands. |

| Moral | Affective, automatic reactions to issues that are viewed as having moral/ethical content (Dane and Pratt, 2009, p. 5) | Not present. | Not relevant. |

| Creative | Feelings that arise when knowledge is combined in novel ways (Dane and Pratt, 2009, p. 5) | We tried to accustom all customer requests. If someone wanted to be alone in the shop, then we booked a time slot for the customer, which we have done a lot. Then we send items to customers for free during the pandemic, or we have delivered the items to the customer’s home and placed them outside the entrance. (store manager 17) | This quote illustrates creative solutions of handling restrictions and customer demands. By offering new ways of shopping, e.g., being alone in the shop, this fashion store found a way of treating their customers during the pandemic. |

Note. Source: The authors.

This section is divided into three parts to illustrate the different phases that store managers experienced during the pandemic, along with the decisions they made during these periods. We argue that these phases represent distinct episodes in which store managers were compelled to make intuitive decisions. Furthermore, these phases, corresponding to different stages of the pandemic, were frequently referenced during the interviews. Throughout these phases, store managers implemented various strategies to preserve the resilience of their stores. Initially, there was widespread uncertainty, as no one fully understood the nature of the pandemic or its potential impact on businesses. Over time, it became evident that the pandemic did not affect all stores equally; some saw a significant surge in demand, while others were more adversely impacted. Despite these differences, many store managers had to rely on intuitive decision-making to navigate the crisis and maintain the resilience of their stores.

A crisis is inherently characterized by uncertainty, which must be addressed by employees, entrepreneurs, and managers alike. This sense of uncertainty was a recurring theme reported by many respondents in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. Particularly at the start of 2020, store managers were uncertain about the nature of the pandemic and its consequences for their businesses, as the following quote illustrates:

…there was no time for preparation. The first day was like…being like an observer, seeing what’s happening. (respondent 12, kitchen store)

The owner-manager of a bicycle store (20) shares his experience:

We have…we had hand sanitizer from the beginning. That, we thought, was important to follow it and keep distance. We kept a bike’s length distance, which is about two meters distance. (respondent 20, bicycle store)

The quote highlights several key points. At the onset of the pandemic in Sweden, FHM held daily press briefings, providing updates on the situation, the spread of the virus, and offering behavioral recommendations. In the early stages, when knowledge about the pandemic was still limited, the emphasis on maintaining physical distance was particularly central. Additionally, guidelines such as staying home when experiencing symptoms and regularly washing hands were prioritized. In response, many stores took measures to secure hand sanitizers for both employees and customers, which was seen as a strategy to enhance their resilience during the crisis.

And then we noticed that people didn’t shop anymore. Well, you didn’t go to stores as before. Instead, people came when they had booked a time for service or one in the family came and bought the item he wanted to buy. It was not entire families that came and had a look as it was before, but now it seems that we are getting back there. (respondent 21, shoe store)

The consequences of the public health recommendations became evident as consumer shopping behaviors changed, presenting significant challenges for many stores.

A notable example is Store 27, which offered face treatments and other personal services and was severely impacted by the initial effects of the pandemic:

Our customers started to cancel their booked treatments. They didn’t want to come. And there we stood with our personnel who didn’t have anything to do. We didn’t get the money that we needed. That was quite desperate and tough then. (respondent 27, beauty store)

In this context, many store managers responded intuitively by asking their employees to take early holidays or go on sick leave at the first sign of possible infection, as this enabled them to receive compensation from the social insurance system. Additionally, the Swedish government introduced financial support for businesses affected by the pandemic’s impact.

One example is a sports retail chain with stores both in Sweden and abroad. In the studied city in South-West Sweden, the chain operated two stores. At the onset of the pandemic, demand for sports items was particularly weak, especially in the early stages. In response, the manager responsible for both stores decided to close the city center location:

We had to close one store, not only due to the pandemic. But it made it easier. We had to adjust for the future…the city store was smaller and we had a little different assortment of products. Here [the bigger store], we have skis, tents, and much more… (store 11, sports store)

Several store managers reported difficulties in understanding and interpreting the restrictions issued by FHM:

Then we got the recommendations from the FHM but no one really knew how to understand them. If you don’t understand…what is it that you should do? Sometimes it felt that no one understood. Then the supermarket group had to sit down together with the industry organisation and the FHM [to discuss]. This can take weeks until we get an answer on how to act. And this is a little difficult, too. (respondent 16, Grocery)

This quote illustrates the high level of uncertainty surrounding how to manage the initial consequences of the pandemic. The interviewed store owners were seeking support and guidance on how to navigate these challenges.

Another store manager (Store 1) describes how they had to develop solutions to meet customer demands while adhering to the general recommendations issued by FHM:

Then we were…yes, we were quite good at adjusting to the demands. We did not have an online store before, but customers who did not want or could not come to shop for their groceries could order their items by email so that we could pick the items and they could pay electronically. (respondent 1, Grocery)

This quote demonstrates an open and solution-oriented approach to handling customer requests. The decision to accept orders by mail was made intuitively, as it provided a practical solution that benefited both customers and the store owners. Regarding deliveries, the store manager (Store 1) further explains:

And then we left the items at the delivery bridge, where customers could pick them up. It is important that all customers feel safe when shopping. We had a lot of these orders. It was about making some changes to accommodate the situation. (respondent 1, Grocery)

The situation being referenced pertains to the COVID-19 pandemic. The store manager (Store 1), who is also the shop owner, viewed this as an opportunity, stating:

Eventually in spring [2021] I decided to get an online store to facilitate both for the customers and us in terms of payments and the like. From May [2021] on you can order all your groceries online. I am probably one of the smallest grocery stores in Sweden, which has an online store, but I think this is the right way to go. Looking at the development of online shopping for groceries, it is growing a lot. (respondent 1, Grocery)

This decision was not the result of extensive planning or careful analysis of customers, markets, and demands. Instead, it highlights the capacity of owner-managers to make intuitive decisions. It stemmed from the experience of the pandemic, where certain vulnerable customers had specific needs. These customers needed to avoid exposure to others to reduce their risk of infection.

As the pandemic progressed and a vaccine became available, the respondents had gained experience and knowledge on how to manage the situation and address its impact on their stores. A store manager (21) reports:

Initially, I had no clue about these furloughs (Sweden introduced a system of furloughs in April 2020, where employers were compensated from the state, when they sent employees in short-term labour of up to 100% due to the consequences of the pandemic.). That was something, Volvo was doing. But what does it mean for our store and how do you handle it? […] There were so many rules, which was impossible to know before. But one has learned a lot. (respondent 21, shoe store)

The quote highlights the challenges that many store managers faced. While they followed the recommendations issued by the FHM, these guidelines were not always clear or straightforward. As a result, store managers had to rely on intuitive decision-making, working with limited information and guidance. The store manager (21) continues:

Everyone was helping. We brought shoes out to customers on the street and they could come early morning or late evening. I think that all store managers in all industries tried to do everything to for their own sake and for their customers’ sake. (respondent 21, shoe store)

This was another measure implemented to limit the spread of the virus and meet customer needs in accordance with current recommendations. The willingness to assist was especially prevalent at the beginning of the pandemic, reflecting the intuitive actions of the store managers involved in this study. However, this intuitive behavior was also influenced by the recommendations of FHM, which emphasized individual responsibility and behavioral patterns:

Everyone has a responsibility to prevent the spread of COVID-19 (https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/the-public-health-agency-of-sweden/communicable-disease-control/covid-19/how-to-protect-yourself-and-others-covid-19-recommendations/ Accessed 29/5/2023) (FHM).

This, along with a continuous emphasis on vaccination against the coronavirus, effectively summarizes the Swedish approach to combating the pandemic. It is also worth noting that the FHM’s announcements became widely followed, as people across Sweden closely monitored the latest updates on the spread of infections and the reporting of casualties. The manager of a small supermarket (2) shares the difficulties he encountered during the pandemic:

You can’t take responsibility for the people. It is difficult to accept that people behave differently, so to speak. (respondent 2, Grocery)

Another store manager (17) from a clothing store highlights the uncertainty and its impact on the store.

It has been a difficult time in that you did not really know how to handle the situation and how you should…should we have open as usual? Should we extend the opening hours so people could spread out and come at different times? Should we reduce the opening hours, so people don’t come to the city? …. But our approach has been to have open as usual, but we have been very observant. (respondent 17, fashion store)

The store manager continues:

We tried to accustom all customer requests. If someone wanted to be alone in the shop, then we booked a time slot for the customer, which we have done a lot. Then we send items to customers for free during the pandemic, or we have delivered the items to the customer’s home and placed them outside the entrance. We have done a lot and emphasised to our customers that we do that. (respondent 17, fashion store)

As the pandemic became a part of daily life, many store owners began to compare their situations with those of other stores in the city and across Sweden. The owner-manager (16) of a supermarket explains:

We benchmark within the supermarket group. We get support from the central organisation, but we have also a group within the organisation of about 12 supermarkets in the region, with which we compare and benchmark. The central organisation has benchmarked with other chains and the Swedish Retail Association. If you compare it with some industry indexes, we performed well. I think that we in smaller cities had it easier than in the big cities and in shopping malls. (respondent 16, grocery store).

As the previous quote suggests, there was significant fluctuation in customer behavior. The owner of a tomato shop (5) recalls:

We sold much more. Due to the pandemic, we had a boom. We increased our sales by 40%. This year [2021] we did not increase more, we are on the same level as last year. (respondent 5, vegetable store)

He continues:

When the pandemic came, people were eager to come to the countryside and shop at smaller places. People didn’t have to do anything as everything was closed.

The owner-manager of a DIY store (14) shared a similar experience:

On the consumer side, it was a total explosion, making our industry opposite to the general trend. Many like us, DIY, commercial gardening stores…everything that had to do with house and home were winners in the pandemic. (respondent 14, construction trade)

Here, we observe a variation between stores from different industries. While some businesses lost much, if not all, of their customer base, others experienced booming demand. Stores in industries where customers vanished were even forced to lay off employees, as the store manager of a beauty salon (26) reports:

We reduced our staff with 40%. They were furloughed by 40%, receiving that part of their salary from the Försäkringskassan [Swedish social insurance agency].

The owner-manager of a supermarket (1) shares his experience:

Yes, those were quick changes. But of course, the entire pandemic was like that. This is not easy either. Infection rates have gone up and done. But that was difficult. (respondent 1, grocery store)

These quotes illustrate how the pandemic initially generated significant uncertainty and insecurity, requiring numerous decisions by store managers. Often, these decisions were made intuitively, as they had no prior experience with a comparable situation. However, as the pandemic became the new normal, managers were able to draw on their accumulated experience, leading to more informed and wiser decisions.

Earlier research has highlighted differences in intuitive decision-making based on an individual’s position within the organizational hierarchy (Clarke and Mackaness, 2001). Additionally, it has been argued that managers of SMEs often employ both intuitive and rational decision-making (Sadler-Smith, 2004). These types of decision-making are frequently used in combination, and some researchers propose that rational and intuitive decision-making lie on opposite ends of a continuum (Armstrong et al, 2012). In crisis situations, intuitive decision-making tends to take precedence, largely due to factors such as time pressure and the experience of decision-makers (Okoli and Watt, 2018).

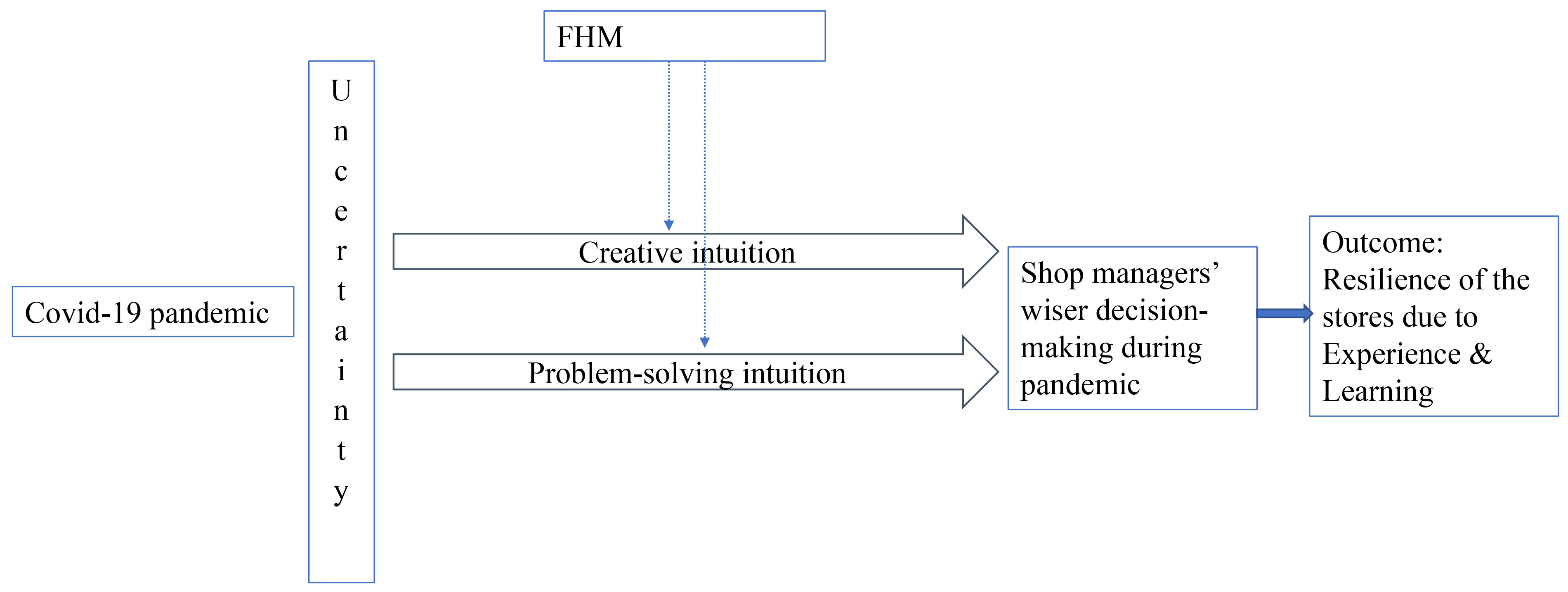

As described in the previous empirical section, the pandemic introduced a high degree of uncertainty, a phenomenon observed not only in Sweden but globally (Okoli et al, 2023). The coronavirus crisis was an entirely new experience for all respondents, particularly in the early stages. During this period, many intuitive decisions made by store managers can be categorized as problem-solving intuition (Dane and Pratt, 2009). This extended to how managers interpreted and implemented the recommendations of FHM. Since intuitive decision-making often involves pattern matching (Okoli and Watt, 2018), several respondents felt lost due to the unprecedented nature of the situation. In crisis contexts, intuitive decision-making tends to dominate (Okoli and Watt, 2018), and many decisions were made based on the intuitive judgments of store managers. These managers relied on both problem-solving and creative intuition, and their intuitive decision-making contributed to the resilience of their stores (see Fig. 1). During this phase, some decisions can be classified as creative intuition, as managers had to synthesize limited knowledge from various sources to inform their choices (Dane and Pratt, 2009).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Intuitive decision-making during pandemic. Source: The authors. FHM, Folkhälsomyndigheten.

Another key issue was how to meet customer demands and requests. Due to the FHM’s rules and recommendations, many stores had to rethink how they served their customers. The FHM’s advice initially focused on maintaining physical distance and protecting vulnerable populations to reduce transmission, followed later by a focus on vaccination (Tegnell, 2021).

Wise decision-making is a significant topic, but what constitutes wisdom or wise decision-making may vary, as it is often contextual (Berardi, 2021). Dane and Pratt (2009) discuss creative intuition, which involves combining existing knowledge in new ways (Miller and Ireland, 2005). In retrospect, it appears that the intuitive decision-making employed during the pandemic contributed to the resilience of the stores, as all of them remain operational. Store managers had to combine their established knowledge—such as their experience in managing the store—with new guidance from authorities, which sometimes challenged their previous ways of operating. Restrictions affecting both personnel and customers had to be implemented by the store managers.

Fig. 1 presents a process-oriented perspective on the factors contributing to wiser decision-making by store managers, which in turn enhances the resilience of the studied stores. While the figure offers a schematic depiction, it highlights key factors influencing wiser decision-making and resilience, including the learning and experience gained during the pandemic, which needed to be adapted to the store’s specific environment. During this time, store managers had to remain receptive to information and recommendations from Swedish authorities, including the FHM, municipalities, and industry associations. This aligns with both creative and problem-solving intuition, which ultimately strengthens resilience, a result of experience and learning.

Rather than planning and meticulously evaluating all decisions, quick decisions were often necessary, including intuitive decision-making (Mintzberg and Westley, 2001; Okoli and Watt, 2018). However, uncertainty does not persist indefinitely. As a study on Swedish SMEs indicates, most did not have crisis plans, and many followed emergent strategies to handle the pandemic. This often involved relying on gut feelings, which can be interpreted as intuitive decision-making (Fasth et al, 2022). Managing unforeseen challenges was difficult, but overcoming them contributed to the resilience of these stores.

Creative and problem-solving intuition guided store managers in interpreting FHM recommendations for their stores. Stores that were part of larger chains received more support from headquarters, but the implementation of recommendations in individual stores still required intuitive decision-making from the store managers.

As illustrated in Fig. 1 and supported by empirical evidence, even intuitive decision-making involves learning processes. Intuition requires experience and learning from past experiences (Dane and Pratt, 2007). Intuitive decision-making complements other decision modes, such as rational and planning-based approaches, which managers typically use in combination. Thus, planning and intuition are not dichotomous but represent opposing poles along a spectrum of decision opportunities (Sadler-Smith, 2004). In this way, intuitive decision-making also contributes to the resilience of SMEs and their managers, particularly during crises (Ishak and Williams, 2018; Okoli and Watt, 2018; Okoli et al, 2023).

Our findings show that SMEs faced particular challenges during the pandemic. We also found that stores belonging to larger retail chains received more support, whereas small, independent stores were left to navigate the crisis on their own. Even those store managers with administrative support faced uncertainty at the beginning of the pandemic, requiring them to rely on intuitive decision-making. Research suggests that intuitive decision-making is common in SMEs (Darby et al, 2022). SMEs are often described as having limited resources and less formal education, leading to more informal decision-making processes (Saiz-Álvarez et al, 2013). The type of decision-making used depends on situational factors as well as the experience and qualifications of the entrepreneur. In crisis situations, as described above, different types of intuitive decision-making, such as creative and problem-solving intuition, are often employed.

What constitutes a wise decision is not always self-evident. Intezari and Pauleen (2018) define wise management decision-making as:

“…an integrated cogni-emotional, reflective process that accounts for internal and external conditions related to the decision, which is made with the well-being of the greatest number of stakeholders in mind.”

This definition emphasizes the importance of reflexivity regarding both content and context. Others have argued that wise decisions involve combining different thinking processes (Svenson et al, 2023), drawing on dual-process thinking that integrates intuition and emotion with analysis and reason, a view supported by more recent research (Okoli and Watt, 2018).

By the second year of the pandemic, many SME managers had gained enough experience to manage the ongoing challenges, despite the pandemic’s persistence. Following the FHM’s recommendations and guidelines became standard practice (Tegnell, 2021), providing a stronger foundation for store managers’ decision-making.

The coronavirus pandemic should be understood as an extreme crisis (Boers and Henschel, 2022a; Boers and Henschel, 2022b). Like other crises, it was unexpected, and many companies and store managers were unprepared, lacking crisis plans (Fasth et al, 2022). Unlike other crises, however, the pandemic was a global phenomenon that lasted for several years. Thus, the transition from intuitive to wise decision-making is not a linear process. Some store managers had prior experience with the financial crisis, which provided a reference point, though the nature and impact of the pandemic were different. Wise decision-making, like intuitive decision-making, is built on prior experience and training (Simon, 2013). Store managers needed to recognize abstract patterns beyond immediate problem-solving.

In the empirical section, we describe the learning process that enabled respondents to improve their decision-making. Since intuitive decision-making is grounded in experience (Sadler-Smith, 2012; Svenson et al, 2023), store managers began reflecting on and refining their decisions. This experience and learning contributed to the resilience of the stores. Surviving the second year of the pandemic can be seen as a prerequisite for wiser decision-making, with resilience emerging as a key factor in navigating the crisis.

This study has demonstrated the importance of managers’ decision-making abilities in providing an effective response to the crisis (Darkow, 2019; Rahi, 2019). Additionally, the interviewed managers exhibited improvisational skills (Darkow, 2019) and developed their decision-making abilities as the crisis unfolded (Vakilzadeh and Haase, 2021), adapting to the changing nature of the pandemic.

The study provides empirical examples of the intuitive decision-making processes employed by store managers during the coronavirus pandemic. We found that respondents frequently utilized intuitive decision-making, with two distinct phases emerging in their decision processes. In these phases, store managers relied on creative and problem-solving intuition. As decision-makers gained experience in managing the pandemic’s effects, their decisions became more standardized and intuitive, as they recognized emerging patterns.

This study presents real-life experiences of store managers in an extreme situation—the COVID-19 pandemic—highlighting that intuitive decision-making is a process, with the actual decisions being outcomes of that process (Dane and Pratt, 2007). The study identifies problem-solving and creative intuitive decision-making as the key forms of intuition used during the pandemic. Since the data was collected while the pandemic was still ongoing, the study avoids the common pitfall of retrospective sense-making, which often affects research conducted after the event has passed (Golden, 1992). Additionally, the study suggests that resilience can be developed during a crisis, with learning rooted in intuitive processes that ultimately lead to wiser decision-making and greater resilience in stores.

For store owners and managers, this study offers valuable reflections on decision-making in extreme situations like the coronavirus pandemic. The findings are applicable to both store owners and employee managers. Reflecting on decision-making has been identified as crucial for making informed choices (Alvesson and Sköldberg, 2000; Alvesson and Spicer, 2012). This study encourages practitioners, such as store managers, to reflect on their roles and decision-making processes, particularly during crises.

Intuitive decision-making remains a significant area for future research (Dane and Pratt, 2007; Svenson et al, 2023). This study focused on retail store managers during the coronavirus pandemic, but crises of various kinds provide relevant contexts for studying intuitive decision-making. Future research could explore this phenomenon in different contexts, such as across countries or industries (Okoli and Watt, 2018; Okoli et al, 2023), and within different types of ownership structures, including publicly-listed companies (Boers and Nordqvist, 2020). Intuitive decision-making is particularly prominent in SMEs, where the entrepreneur, often also the owner-manager, plays a central role in both daily and strategic decisions. Research on intuitive decision-making in public organizations (Svenson et al, 2023) or large organizations could also be valuable, as these organizations tend to emphasize rational decision-making. Questions such as whether there are differences in intuitive decision-making across hierarchical levels or decision types warrant further exploration.

Given the study’s focus on the coronavirus pandemic, future research could investigate current crises, such as the energy or inflation crises, which have a significant impact on SMEs. This would provide an opportunity to assess how learning from the pandemic has influenced intuitive decision-making. Research could also examine which patterns decision-makers use and whether these patterns develop individually or collectively during extreme events like the pandemic. This ties into the broader topic of resilience, which can result from intuition and learning during crises.

Another avenue for future research is the level of analysis. Intuitive decision-making typically concerns managers as both individuals and organizational functions. Therefore, it would be relevant to combine individual-level intuitive decision-making with organizational-level constructs, such as strategic flexibility (Brozović et al, 2023), as managers may need to demonstrate strategic flexibility in certain situations, and the role of intuitive decision-making in this context has not yet been fully explored. Additionally, recent studies suggest examining intuition at the team level, as collective intuition has received limited attention (Akinci and Sadler‐Smith, 2012; Acciarini et al, 2021). This aligns with emerging research on collective decision-making, such as shared leadership (Imam and Zaheer, 2021), particularly in family firms (Neffe et al, 2020). Finally, studying SMEs in crisis through the lens of effectuation—a concept found useful in crisis contexts—presents a promising avenue for future research (Laine and Galkina, 2017; Osiyevskyy et al, 2023).

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality but are available from the [corresponding author/data access committee] on reasonable request.

BB and DB designed the research study. BB and DB performed the research. BB and DB analyzed the data. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The researchers received funding for conducting research by the Sparbanksstiftelsen Varberg “Efterfrågad forskning 2021”.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used [ChatGPT-3.5] in order to [check spelling and grammar]. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

| Company/Store | Type of store/industry | No. of employees | Turnover 2020 in Thousand Swedish Crowns (TSEK) |

| 1 | Grocery | 11 | 44,879 |

| 2 | Grocery | 7 | 26,778 |

| 3 | Paint | 10 | 36,487 (2019) |

| Merger in 2020 | |||

| 4 | Optician | 5 | 8997 |

| 5 | Vegetables | 7 | 8675 |

| 6 | Man’s fashion | 6 | 7590 |

| 7* | Clothes | 42* | 93,592* |

| 8* | Furniture | 678* | 2,448,094* |

| 9 | Fish | 30 | 56,757 |

| 10 | Books | 6 | 12,588 |

| 11* | Sports | 588* | 1,706,701* |

| 12 | Kitchen | 6 | 15,070 |

| 13 | Grocery | 120 | 438,163* |

| 14 | Construction trade | 12 | 84,910* |

| 15 | Household appliances | 13 | 8250 |

| 16 | Grocery | 80 | 209,368 |

| 17 | Woman’s fashion | 9 | 8216 |

| 18 | Fashion | 3 | 7480 |

| 19* | Grocery | 151 | 486,173 |

| 20 | Bicycle | 6 | 21,381 |

| 21 | Shoe | 6 | 8124 |

| 22 | Sport equipment and fashion | 8 | 19,535 |

| 23 | Gardening | 8 | 19,569 |

| 24* | Pet store | 268* | 841,706* |

| 25* | Textiles | 365* | 1,051,357* |

| 26 | Clothing | 4 | 8269 |

| 27 | Beauty | 5 | 6381 |

| 28* | Health | 213 | 479,046* |

Note. * Group level figures (numbers for individual stores not available!).

1. Presentation of researchers and project

2. Can you tell me about the shop/company and your role)?

3. How was your shop/company affected by the coronavirus pandemic?

4. Have you been able to prepare before the crisis? If yes, what did you do and why? If not, why not?

5. Have there been time periods that were easier to handle? Or worse? Why?

6. What helped the most to handle the crisis for the shop/company? Exemplify if necessary!

7. What made it more difficult or hindered you?

8. Referring to the answer in number 5, what contributed to whether it went better or worse? Which factors helped and which made it more difficult during the different periods? Have the factors varied over time?

9. What do you think about the future of the shop/company?

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.