1 Norwegian College of Fishery Science, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, 9019 Tromsø, Norway

2 Department of Business Administration, Başkent University, 06790 Etimesgut, Türkiye

3 Corvinus Institute for Advanced Studies, Corvinus University of Budapest, 1093 Budapest, Hungary

4 Department of Philosophy, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, 9019 Tromsø, Norway

5 Department of Trade and Social Work, Ostfalia University of Applied Sciences, 29556 Suderburg, Germany

Abstract

There are several well-established concepts that explain decision-making. The sociology of wise practice suggests that thinking preferences like the use of intuition form a cornerstone of administrators’ virtuous practice and phronesis is a likely candidate to explain this behaviour. This study uses conceptual and theoretical resources from behavioural sciences, management science, as well as philosophy to account for individual level differences in employees’ thinking preferences in administrative professions. The analysis empirically investigates the behavioural dimension of the preference for intuition versus the preference for deliberation by examining three different intuitive markers present among individuals who nonetheless prefer to use deliberation. We explore possible explanations for the differences and similarities within our global sample of 2227 workplace respondents who conceptually represent phronetic practitioners. The results show that many phronetic practitioners prefer the intuitive marker of unconscious thought in addition to deliberation.

Keywords

- intuition

- deliberation

- decision style

- virtue

- wisdom

- phronesis

- Aristotle

- emotion

Members of any organization, at any level, employ some degree of discretion in their work; this use of discretion is not only unavoidable but crucial (Freiling, 2004; Freiling et al, 2008; Vickers, 1984; Wangrow et al, 2015). Judgments and wise decisions are now considered to be one of the most crucial aspects of leaders’ responsibilities (Nonaka et al, 2014; Wright, 2022). The term ‘phronesis’, or ‘practical wisdom’ integrates the thinking processes of intuition and deliberation (Svenson et al, 2025; Svenson et al, 2024, Svenson et al, 2023b). Hence the focus of this article is on how judgment and practical wisdom can be pinpointed in decision-making characteristics at the workplace during the year 2020 of the global pandemic. More specifically, we want to find out which intuitive markers surface among practitioners with a preference for deliberation.

The findings can pave the way for a better understanding of the contextual integrative potential of phronesis (Svenson et al, 2023b). While previous studies rely primarily on direct observations and a small research design (Goodsir, 2018; Massingham, 2019; Oktaviani et al, 2016; Rooney, 2013; Shotter and Tsoukas, 2014), mainly using qualitative methods, we use a large survey design using quantitative methods. In what follows, we will first lay out the conceptual landscape for our investigation before turning to methodological considerations, our statistical findings, and their discussion.

For Aristotle, practical knowledge and moral virtues go together: it is impossible to be practically wise without being morally good (Van de Ven and Johnson, 2006). Eikeland (2008, p. 53) remarks that phronesis, commonly translated as ‘practical wisdom’ is ‘both an intellectual virtue and an ethical virtue’; phronesis includes being wise, aware of the situation, and open to dialogue and to the other (Contu, 2023). Moberg (2007, p. 536) sums up the idea like this: “I define practical wisdom as a disposition toward cleverness in crafting morally excellent responses to, or in anticipation of challenging particularities.”

This gives many the idea to associate practical wisdom (phronesis) with ethical decision-making and to apply this also to the management context. Some limitations, however, must be kept in mind. In particular, the subject of practical wisdom is how to live well; this is why phronesis is often translated as ‘prudence’ in English (Provis, 2010 p. 9). There is no overt ethical (moral) dimension, as one might notice. This is because living well and doing the right thing are the same thing for Aristotle: the (personal) good and the (morally) right are congruent with each other. It is important to note, specifically in the business context, that this need not be accepted: one can discuss ethical decision-making without holding that a wise decision must also be the morally right one and vice versa. In other words, a business decision can be prudent but not ethical, it can be ethical but not prudent and it can be both at the same time. For example, the concept of wisdom, its nature, and its extension (what it includes) are much discussed issues in philosophy (see Ryan (2023) for an overview). That is, unless one agrees with Aristotle, practical wisdom can bifurcate into a prudential and moral segment along more or less how we tend to think about these matters in modern times: that morality can conflict with self-interest and vice versa. In this paper, we are interested in practical wisdom as ethical wisdom leaving its possible conflict with prudence out of the picture. This raises the question how much business ethics wants to endorse the full package of standard virtue ethics. To mention one further matter that would then have to be sorted out, practical wisdom is a so-called organizing virtue in standard virtue ethics: it rules over other virtues. How exactly this happens is little discussed in the management literature (cf. Moberg, 2007, p. 544 on the ‘unity of virtues’ thesis). Again, we intend to sidestep these controversial and complex matters in the article.

Our starting point then, is the concept of practical wisdom and we first query what, on the conceptual level, wise decisions consist of. Secondly, we query the empirical support for such an account of wise decision-making. For, once we manage to break down practical wisdom into operationalizable elements—further constitutive concepts—we can also study wise decision-making empirically. Where to begin? Judged from the extant business management literature (e.g., Sadler-Smith, 2012), we get roughly the following picture. On the conscious, inferential, non-emotional side there are the deliberative cognitive processes of analysis and reflection in structures provided by principles and frameworks; on the unconscious, non-inferential, affective side there are the intuitive cognitive processes of holistic pattern recognition in complex situations (Provis, 2017, p. 11; Shotter and Tsoukas, 2014, p. 387). There is here, of course, a clear connection to the dual process (cognition) theory of decision-making. We shall say more about this in the next section.

The next question is on which side wisdom lies: the deliberative or the intuitive? Historically, the deliberative side was influential (corresponding to so-called rationalist approaches in philosophy), but recently the intuitive side seems to have become more prominent (philosophically this can be taken to correspond to both the rationalist and the sentimentalist approaches depending on how one understands intuition). Within the field of business ethics and beyond, several scholars now associate practical wisdom closely with affective and emotional thinking processes (Massingham, 2019). This intuitive fast thinking style is then taken to wrestle with an analytic or deliberative slow thinking style (Kahneman, 2011).

Researchers reconstructing the cognitive processes that foster practical wisdom take recourse to intuition when they aim to describe what virtuous practice or practical wisdom means from a practitioner’s point of view (Bachmann et al, 2018). The business administration literature that looks at wise practice often shines a light on skillful actors that use their intuition. For example, Shotter and Tsoukas (2014) describe phronesis thus: “Phronetic practitioners, therefore, are those people who have developed a refined capacity to intuitively grasp the most salient features of an ambiguous situation and to craft a particular path of response, in their search for a way out of their difficulties, while driven by the pursuit of what is good for their practice.” It must be said, though, that in philosophy at least, there is no established orthodoxy regarding a connection between virtuous practice (cognition) and intuition, although there appear to be parallels between the two on certain accounts of intuition and virtue, respectively (Zagzebski, 2003; Kauppinen, 2013). There is a ‘subjective’ quality of what it means to be wise (Nonaka et al, 2014, p. 370).

At the same time, there are also critics of affective and emotional thinking processes (McMahon and Good, 2016), associating fast intuitive thinking with a reduced probability of ethical behaviour (Street et al, 2001). In fact, Warner and colleagues (2024) reviewed the literature highlighting that there are roughly as many articles associating ethicality with intuition, as there are articles associating ethicality with deliberation (Julmi, 2024). A possible explanation for this indeterminateness is that people have different conceptions of what it means to use intuition (and, relatedly, what in fact intuition is). In fact, in philosophy, it is rarely questioned that intuitions would provide us with ethical knowledge. When this is questioned it is done so on ontological grounds: on the ground, typically, that intuitions are no different from ordinary cognitions (such as belief), so there is no reason to rely on them specifically. Such ontological disputes are, however, not suitable for discussion in this paper. Similarly, it is not obvious why one must decide between deliberation and intuition in constituting practical wisdom; why this is an either/or question. It seems to us (and to others, cf. Provis (2010); Sadler-Smith (2012)) that deliberation and intuiting can go hand in hand, they can complement each other’s functions. Our contribution can thus further the sociology of wisdom, which also surfaces in management practice.

To sum up, we accept that practical wisdom or phronesis is closely tied up with the concepts of intuition and deliberation. Of the two, our particular interest in this paper lies with the former. We also think that most skepticism and occasional misuse of intuition have to do with a mistaken understanding (conceptualization) of them. We intend to correct this, to the extent that we need to for the purposes of this paper. The studies cited above unearth a research program favouring additional attention to intuition. However, their work is only loosely connected to extant work in multidisciplinary research on intuition. Such work explains phronesis from within practice (e.g., Van Steden, 2020). The most prominent concepts in the psychology of managerial decision-making, namely intuition and deliberation, feature only indirectly in several studies on phronesis. Authors such as Shotter and Tsoukas (2014) implicitly link phronesis to discretion and attach great importance to taking time to make a good decision. There is a lack of depth in the concept of time as it relates to management discretion. It is mostly conceived as an inert idea, but something that varies over time as people gain more experience (Wangrow et al, 2015). To address these gaps, we highlight conscious intuitive markers (those of which decision-makers are aware) to better understand the temporal dimension under wise decision-making.

In the next section, the well-established approaches that supplement intuition and deliberation are briefly laid out, before the paper continues to introduce the methodological approach.

Many people have tried to explain what intuition is. Well-known literature that has been cited over 2000 times defines intuitions as “affectively charged judgments that arise through rapid, non-conscious and holistic associations” (Dane and Pratt, 2007, p. 33). In philosophy, the study of intuitions has a long history and focuses on many issues. One can ask the questions what it is exactly that we intuit (things in the world or propositions that represent them?); what intuitions are (what kind of ‘things’ are they?); and how are they best characterized (what are their most important features?). To establish a connection, it seems that the business management literature, as seen from a philosophical point of view, takes intuitions to be a form of non-sensory perception (‘pattern recognition’, e.g., Provis, 2010) that is affectively charged (i.e., bound up with emotions), often quick (immediate), spontaneous, non-inferential, and unconscious. To this, philosophers would add that intuitions have a certain kind of phenomenology (they feel in a particular way), that they are stable (not flicker but endure over time), and that they intrinsically (by themselves) motivate. Not nearly every philosopher would accept this account of intuitions, but at least some would accept many or most of these characteristics (Bruder and Tanyi, 2014). It should be noted though that for the purposes of this article only some of these features or markers will be important, as we shall explain below. (Ideally, a more comprehensive method—perhaps a form of triangulation—could be used to properly identify intuitions but such a complex endeavour goes beyond the scope of this paper, which is only intended to constitute the first step on the road.)

Another way to approach the question is to relate the concept of intuition to theories in the experimental psychology and neuroscience literature. Overall, most scholars from different disciplines have endorsed intuition from a dual process perspective as a recent review of the business ethics literature shows (Warner et al, 2024). Is it possible to isolate phronesis amidst established measures of intuition and deliberation? We argue that it is and that we can explain aspects of decision-making behaviour that hitherto have not been isolated satisfactorily.

The so-called dual-process theory (Epstein, 1994; Kahneman, 2011; Sloman, 1996) holds that there are two types of cognitive processes underlying people’s judgments, decisions, and problem solving. Accordingly, both processes compete for guiding decision makers (Hodgkinson and Sadler-Smith, 2018). Still, while people use both thinking processes, they are assumed to display a preference for one (of the two) thinking styles (Betsch, 2004). Like Sadler-Smith and Burke-Smalley (2015), who bring up ‘cognitive versatility’ to describe the capability of using both processes, we consider it a conceptual merit to account for people displaying both high intuition and high deliberation, as this would allow a peek at decision-makers who are able to skillfully use both thinking processes through meta-cognition or phronesis. Nevertheless, our focus will be on the intuitive side where we aim to isolate a set of features that we think characterize intuitions. For simplicity’s sake and for easy future reference, let us call these Marker 1 (‘emotional marker’), Marker 2 (‘temporality marker’), and Marker 3 (‘consciousness marker’) respectively. We propose to account for these markers based on prior works on the emotional (Betsch, 2004), fast (Gigerenzer and Todd, 1999), and unconscious (Dijksterhuis and Nordgren, 2006) aspects of intuitions. The sheer complexity of tasks can induce individuals to think quickly or slowly. Marker 1 can also be understood as affective thinking (Betsch, 2004) in the dual-process theory. Unconscious thinking (Dijksterhuis and Nordgren, 2006; Dijksterhuis et al, 2006) our Marker 3, which is even ‘slower’ than conventional deliberation, and quick heuristics (Gigerenzer and Selten, 2002; Gigerenzer and Todd, 1999; Gigerenzer et al, 2011; Gigerenzer, 2015; Gigerenzer, 2021) our Marker 2 above, account for thinking fast and slow.

Our aim is to bridge what is referred to as “intuitive practice” outside of academia with theoretical investigations into the nature of intuition. For example, take people who like to wait until the last minute to make a choice. This also includes people who think intuitively but do other things (distraction) before they need to decide (Dijksterhuis and Nordgren, 2006). Even if a person has the right knowledge and skills and knows when to use them, that’s not enough if they don’t want to use them (Bensley, 2020, pp. 75–76).

Gigerenzer and Todd (1999) suggest that the person making the decision chooses heuristics, which are simplified ‘rules of thumb’ that people use when they don’t know what to do, e.g., due to cognition-related information overload. This marker is also called ‘quick intuition’ or fast and frugal heuristics (Svenson et al, 2023a). This is done while adapting to the environment and the situation. This choice, for example from a specific domain of work, shows that people make decisions by recognizing patterns. In different parts of daily life, people who study intuition have observed that deliberate analysis doesn’t always lead to a better decision and there is evidence that the intuitive choice is better than the deliberative choice when the choice is more complicated (Dijksterhuis et al, 2006). Sometimes, these observations of everyday life don’t hold up to the scrutiny of the scientific method, though. Therefore, intuition research is always struggling with claims of knowledge from both highly regarded studies and studies that haven’t been proven scientifically (Dörfler and Bas, 2020). More recent research updates the theory of Ap Dijksterhuis (Dijksterhuis and Strick, 2016) suggesting that conscious thought and unconscious thought appear to alternate, as do the conscious and unconscious components of real-life decision-making. Unconscious information processing is linked to taking time before deciding, such as to sleep on it or to distract oneself to avoid consciously thinking about it.

As we noted, we focus on the intuitive side of reasoning. In the dual-process paradigm, this makes our work on the three markers largely focus on so-called System 1 processes. These processes are automatic, fast, and unconscious, and are referred to as heuristic and intuitive. Whereas System 2 processes are slower, conscious, and are referred to as rational, analytical, and deliberative. Default-interventionist explanations of dual processes imply that System 1 processing consists of snap decisions most of the time, with occasional overrides from System 2 (Kruglanski, 2013). The unconscious markers of intuitions (Dijksterhuis and Nordgren, 2006) that surface under distracted attention add a further layer to System 1 processes. Markers 1–3 are thus generally associated with System 1 processes in psychology. We do not have a problem with this, but two important points need to be kept in mind.

First, as many emphasize both in philosophy (Kauppinen, 2013, p. 372) and in business ethics (Provis, 2017), intuitions often only arise after intensive inquiry, reflection, and scrutiny. In other words, System 2 processes are often necessary for the emergence and use of intuitions in System 1 processes. From the philosophy side, this is because what is crucial about intuitions is not so much the fastness and immediacy of their occurrence, but that they are not the results of inferential justificatory chains among (the propositional content of) one’s beliefs and cognitions more generally. Consequently, an intuition can emerge also at the end of a long reflective inquiry—inferential structures do not coincide with the length and depth of our thinking processes. Given the circumstances of business decisions, often heavily reliant on experience, reflection, and analysis, this might even be more so in business administration. Second, on a more general note, some of the leading advocates of dual-process approaches to moral psychology do not (any longer) think that the simple System 1 vs. System 2 distinction reflects what is happening in the moral mind-brain (Cushman, 2013; Huebner, 2015). In fact, prominent dual-process researchers have long admitted the heterogeneity within each ‘system’ and the failure to map all the proposed attributes of particular mental processes (including our proposed markers of intuitions) onto the two systems (Evans, 2011). While the dual-process approach offers a useful distinction for the start of a scientific inquiry into morality, it may be holding up our understanding and theoretical explanation of our moral psychology. In short, we can accept that our investigation focuses on System 1 processes if the above are kept in mind.

After decades of study in various branches of psychology, the general consensus seems to be that unconscious processes have a significant impact on behaviour (Pratt and Crosina, 2016) and that effects on organizations cannot be ignored (Vince, 2019). To contribute to the empirical discussion on phronesis, this article investigates a global sample of professionals whom we call ‘deliberators’. We agree with Ackerman and Morsanyi (2023) that it is important to control for individual differences among practitioners. The research design takes the preference for deliberation in our sample of respondents for granted to probe which intuitive markers appear in most of them. In other words, we take it for granted that these people are fond of analysing, focusing attention on consciously using rational or critical thinking. Then this article further investigates which of the mentioned intuitive markers appear in these people’s decision-making preferences. This procedure offers to explicate the cognition of practical wisdom at the workplace. In this way, the article can shine a light on the decision-making style present among managers with a preference for deliberation to determine which intuitive marker characterizes most of them, when they intuit. Phronetic practitioners are those that use both deliberation and intuition (investigated via Markers 1–3) when weighing their options. Through this, we contribute a depiction of practitioners’ phronesis—respondents preferring both deliberation as well as intuition—as it is conceived of in everyday organizational settings. Reviews of the literature show that intuition comes in several guises (Svenson et al, 2023a). Through testing how far the decision-making style of managers with a thinking preference for deliberation also displays markers of intuitive decision-making, the article addresses an important lacuna. The paper therewith adds a missing quantitative sample in work on wisdom in organizational settings.

It is assumed that a sizable group of managers with a preference for deliberation also prefers intuition. When we find out which marker of intuition this group of deliberators prefers, we can explain how phronesis materializes in the minds of managers. We have a match for phronetic practitioners when respondents score high on deliberation and high on intuition. We may then consider these people to possess phronesis.

The data was gathered beginning in March 2020 and ending in August of that year via an online survey on intuition (Launer and Svenson, 2023) and digital trust (Marcial and Launer, 2021). After being invited, participants completed the survey online. A participant recruitment agency sent out invitations to two countries (the United States of America and Slovakia). The first and fourth author, along with their respective professional and personal networks, used social media to spread invitations for a snowball sample in other countries. It is hard to say what the overall response rate was because it is not known how many people could have answered the questionnaire (i.e., how many people had been reached by the two recruitment methods employed when combined). Among all the people who started the survey, about half sent in a fully filled-out survey. These data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The final sample for this study consisted of 2227 individuals working in different industries from more than 30 countries. Prior research suggests that different cultures share certain common ideas about what constitutes wisdom, while also privileging some aspects of wisdom over others (Dewangan and Ghosh, 2022). Our survey was translated into different languages and checked for accuracy by native speakers from the respective countries. Gender distributed as male (57%), female (34%), and non-binary (8%). Age ranged from 18 years old or younger (1%), 19–28 years old (14%), 29–38 years old (19%), 39–48 years old (37%), 49–58 years old (28%), and 59 years old or older (2%).

To measure the preference for deliberation and intuition (PID) in decision-making the PID-inventory by Betsch (2004, 2008) was used. 13 self-disclosure items were inspired by the original inventory and translated into the respective national language. The PID is a valid and reliable test of decision-making preference consisting of two scales: one measuring the preference for deliberative decision-making (5 items, e.g., “I tend to be a rational thinker.”; Cronbach’s Alpha 0.90) and a second scale measuring the preference for intuitive thinking (6 items, e.g. “I am an intuitive individual.”; Cronbach’s Alpha 0.85). Items were assessed on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), such that higher scores indicate higher agreement to the decision-making style.

To measure the intuitive markers of heuristics (Marker 2) and unconscious thinking (Marker 3), scales were developed based on the works of Gigerenzer (2015) and Dijksterhuis (2006). Pre-test data from June through November 2019 were used to calculate internal consistency. Tests were conducted in China, Japan, South Korea, Paraguay, Russia, Brazil, Thailand, the United States, and the United Kingdom (Marcial and Launer, 2021). The intuitive markers of fast heuristics, slow unconscious thoughts, and emotional intuition were proven to be valid, reliable, and independent variables (Launer and Svenson, 2023). We have made sure that the newly developed scales have a satisfactory empirical fit.

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to determine the significant differences between groups of respondents reporting a higher level (mean is above 3.67 or higher, 75th percentage) and respondents reporting a lower level (mean is above 2.33 or lower, 25th percentage) preference for deliberative (rational or critical) thinking.

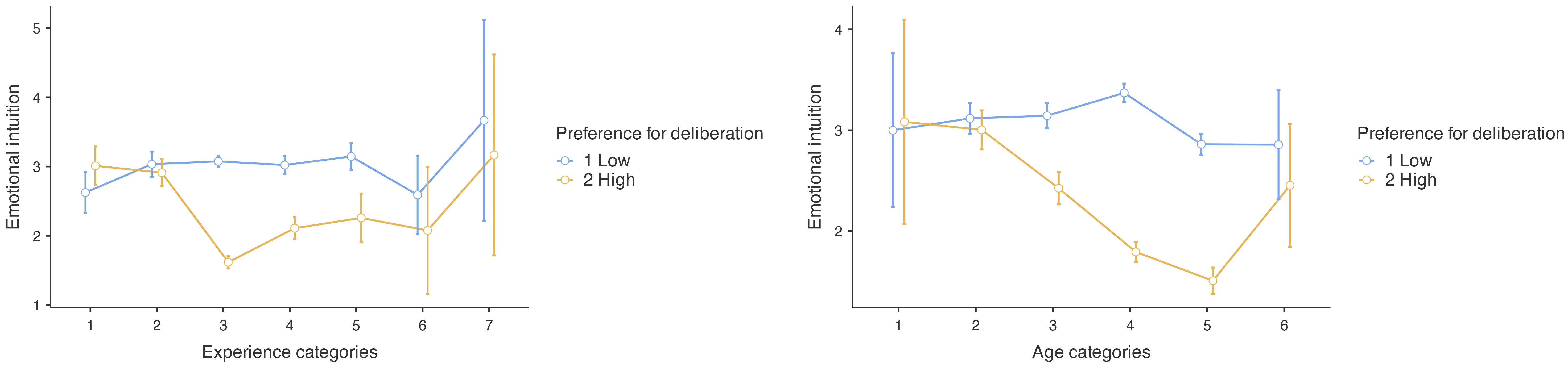

Generally lower-level deliberative, sometimes also referred to as ‘rational’ or ‘critical’ thinkers prefer more emotional intuition than higher-level ones in all experience and age levels (Fig. 1). Particularly, there are statistically significant differences regarding work experience for respondents reporting the value 3 (4–10 years) and 4 (11–20 years) in the rational groups, and in the age groups for respondents reporting the value 3 (29–38 years old), 4 (39–48 years old), and 5 (49–58 years old). Lower-level deliberators prefer significantly more emotional intuition than those respondents reporting higher scores in the preference for deliberation, when they have between 4–10 years and 11–20 years of work experience (only for level 3 and 4 experience groups), and when the ages are between 29 to 58 years old.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Preference for emotional intuition of respondents with low (1) and high (2) preference for deliberation.

Findings on emotional intuition seem to confirm that more work experience (value 4) and older age corresponds to a more pronounced use of intuition. Since those respondents reporting higher scores in the preference for deliberation (preferring ‘rational’ thinking) only display a preference for emotional intuition with less work experience (but not for level 3 and 4 experience groups) and younger, we may document that the more work experience respondents have and the older they are, the more they use emotional intuition, our Marker 1.

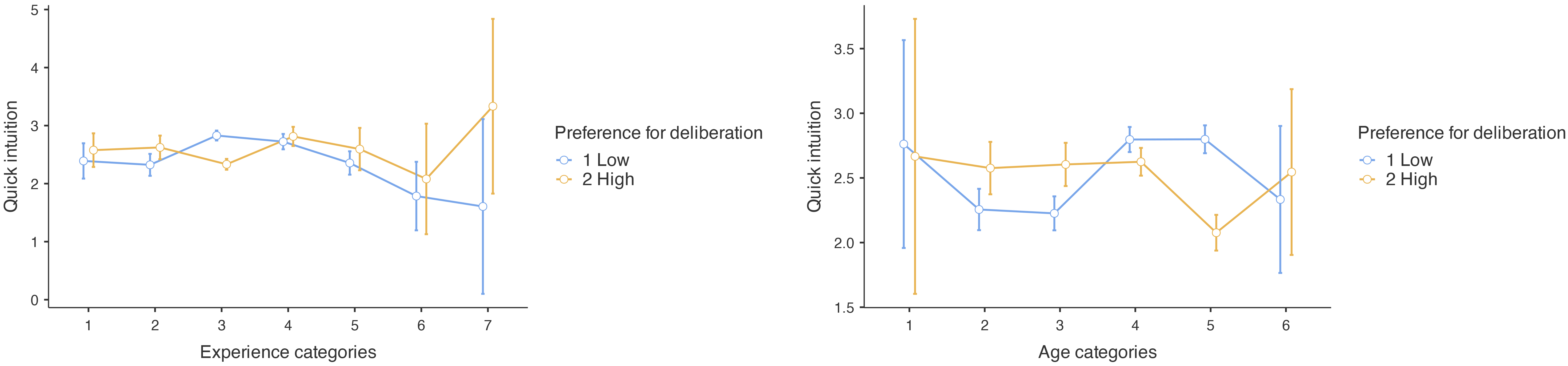

Generally, there are moderate differences between higher-level deliberators and lower-level ones in almost all work experience and age levels (Fig. 2). Particularly, there is a statistically significant difference in experience just for respondents reporting the value 3 (4–10 years of work experience) in the rational groups and age for reporting the values 2 (19–28 years old), 3 (29–38 years old), and 5 (49–58 years old). Lower-level deliberators prefer significantly more Quick intuition than higher-level ones (only for respondents reporting the value 3 for work experience and 5 for the age groups). Higher-level deliberators prefer significantly more Quick intuition (our Marker 2) than lower-level ones (only for respondents reporting the values 2 and 3 for the age groups).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Preference for quick intuition of respondents with low (1) and high (2) preference for deliberation.

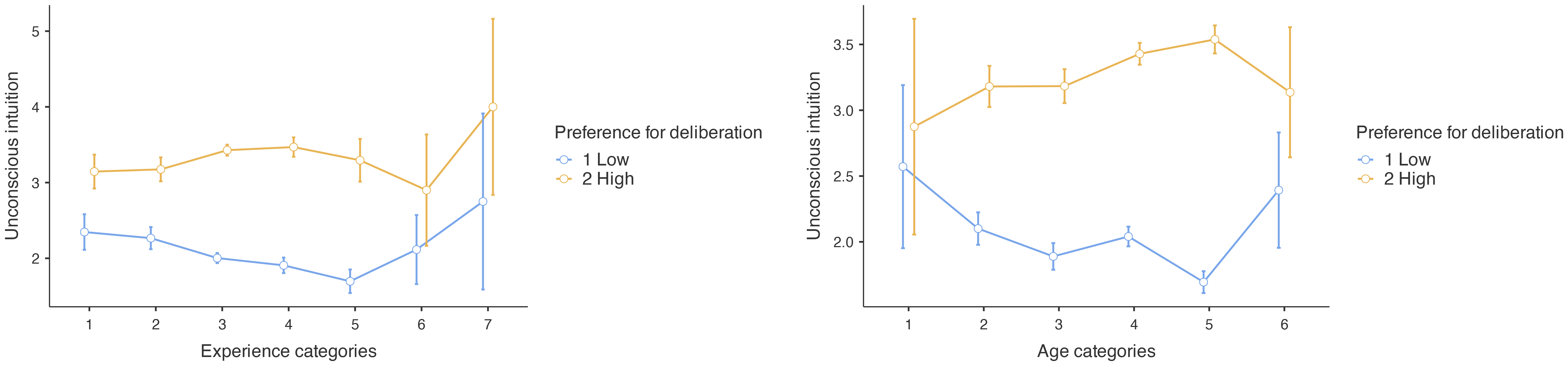

Generally, higher-level deliberators prefer more unconscious intuition than those with a lower level in almost all experience and age levels (Fig. 3). Particularly, there are statistically significant differences for respondents reporting the value 3 (4–10 years of work experience), 4 (11–20 years of work experience) and 5 (21–30 years of work experience) and age groups for 2 (19–28 years old), 3 (29–38 years old), 4 (39–48 years old), and 5 (49–58 years old) in the rational groups. Higher-level deliberators prefer significantly more unconscious intuition (our Marker 3) than lower ones (only for level 3, 4, and 5 work experience groups and for level 2, 3, 4, and 5 age groups).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Preference for unconscious intuition of respondents with low (1) and high (2) preference for deliberation.

People may not even be aware that they are making conscious decisions. The human brain is capable of unconscious thinking (Dijksterhuis and Nordgren, 2006; Dijksterhuis et al, 2006; Zhong et al, 2008) and there exists a substantial body of research indicating that solutions occasionally manifest abruptly in the cognitive processes of decision-makers (Billett, 2004).

Our assumption that managers with a preference for deliberation can successfully accommodate intuitive techniques is consistent with the dual-process understanding of information processing that dominates cognitive psychology (Epstein, 1994; Evans, 2011; Sloman, 1996). Nevertheless, whereas in this tradition intuition is subordinate to reason and only serves as an input for deliberative decision-making processes, our take on phronesis, building, among others, on Sadler-Smith (2012) offers a different, more balanced integrative solution where both mechanisms contribute equally to wise decision-processes, therewith also supporting earlier contributions in organization studies (e.g., Calabretta et al, 2017). Our results contribute to focusing on the temporal dimension that is associated with wise decision-making (Shotter and Tsoukas, 2014). In our alternate account of tracing the cognitive processes behind phronesis, we have had the opportunity to preliminarily rule out that intuitive markers are only ‘biasing’ heuristics. Our findings resonate with De Neys (2023), who also conceptualized that System 1 thinking generates different types of intuitions (see also Svenson et al, 2023a), which we referred to as intuitive markers. We were able to discern a more complete account of intuition and deliberation for the sake of phronesis that people in the real world live by.

Note that our approach here is descriptive. A descriptive claim is advanced by us about which (multiple) thinking preferences people prefer. Like Haidt (2001, p. 815) wrote, it must be stressed that this is “not a normative or prescriptive claim, about how moral judgments ought to be made.” The thinking preferences that virtuous practitioners display are pointed out in this article: wise decision-making involves extra time.

Organizations need to grapple with how they want to enable their managers to use intuition in order to exercise wise practice. When practitioners of administration intend to follow virtue ethics, provisions must be installed making sure, that people are aware of consciously using their intuition in the first place.

In a review of factors influencing ethical decision-making, Casali and Perano (2021) have noted that more research on cognitive moral development is needed. The ability of a reasoner to switch between intuitive and conscious processing has been the subject of heated discussions (De Neys, 2023). The goal of this article has been to contribute to this discussion by showing, relying on empirical research, the intuitive marker most often used by phronetic practitioners. Our findings suggest that taking extra time to rely on unconscious thought is a viable way for many deliberators to make decisions.

Aristotle’s virtue ethics remains an inspiration for many scholars of administration. Building on virtue ethics approaches in management, support for the use of intuition and deliberation is observable. Rather than conceptualizing only the use of intuition and only the use of deliberation as a path toward wise practice, the interplay of these two processes promises virtue to bring about phronesis. The theoretical contributions to virtue ethics take this duality into account (Rooney and McKenna, 2008; Van Steden, 2020), but there has been little empirical work highlighting it until now.

By testing the assumptions of earlier works in business ethics, the results suggest that there is no one best solution through decision-making, but that it is much more about the interaction of the two processes, and that temporality matters, for phronesis to emerge. This supports conceptions that see these dual processes of cognition as competing for a path of action (Hodgkinson and Sadler-Smith, 2018; Sadler-Smith, 2012). The article theoretically contributes to the sociology of wisdom (Rooney et al, 2021) by highlighting how temporality impinges on managers’ thinking preferences. The findings also imply that wisdom research must care for raising awareness about how decisions are enmeshed with everyday administrative practice.

The research object intuition is intangible, for the practitioner using intuition appears to be hard to access. Raising awareness about their freedom of choice when it comes to decision-making can be a first step towards improving administrators’ use of intuition to encourage wise practice proactively for building integrity. Since the intuitive marker of temporality was used especially often by the respondents in our sample, we recommend practitioners to allow for time, when decisions that are likely to require phronesis need to be made.

The results of hasty decisions made by overconfident leaders can be disastrous. Collective well-being can be attained through slow, deliberate acts and phronesis-based decisions (Contu, 2023). Training and education programs could be improved with a better understanding of phronesis and the factors that lead to its development (Goodsir, 2018).

The authors are aware that there are scales that measure how well someone makes ethical decisions. Scales like these have been criticized in the social sciences because they always lead survey respondents to give answers that are socially desirable (Krumpal, 2013). Work done in the past shows that some of these dangers can be avoided with an instrument that looks at decision-making in general rather than ethical decision-making. It is also important to note that the scales are all based on what professionals say about themselves. This means that the way professionals make decisions in real life has not been measured, which is due to the limited representativeness of our sample.

When and how are decisions made consciously, rather than just knowing (from within) what to do in each situation? It is a first cautious approach to the subject of research, which is otherwise researched using mainly qualitative methods. To use intuition more actively to foster phronesis is to perceive freedom to act more consciously, becoming more conscious of the discretion to act. This line of research could then be connected to work on managerial characteristics featuring as antecedents to managerial discretion (Wangrow et al, 2015).

When the use of discretion is connected to exercising phronesis pressing issues in administrators’ everyday work can be solved in a more satisfactory manner. Common dual-process accounts of decision-making rarely account for qualitative differences among intuitive responses, which are part of phronesis. Phronesis may account for instances in which decision-makers skillfully combine intuition and deliberation. This study finds that people with a preference for deliberation also use different intuitive markers tied to emotion, temporality, and consciousness. Overall, based on our results we can assume that intuitive markers facilitate the exercise of phronesis. An alignment between deliberation and intuition is essential for attaining complex virtues (Epstein and Pacini, 1999). To strike the ideal equilibrium and engage in wise decision-making, one must engage in acts of self-awareness and judgment that draw on both explicit and tacit kinds of knowing, reflexive self-knowledge, and the use of both deliberation and intuition (Hodgkinson and Sadler-Smith, 2018). Our article has found empirical support for the cognitive complexity of practical wisdom in the workplace. Managers with a preference for deliberation tend to be most inclined towards the intuitive marker of unconscious thinking when they rely on their intuition (see Fig. 2). The results emphasize the cognitive process, not the outcome of making wiser decisions, and build on prior research in experimental settings (Nordgren et al, 2011) as well as in leadership conceptions of mindfulness (Rooney et al, 2021). Through this, we contribute a depiction of phronesis as it is conceived of in the everyday of decision-makers.

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

FS, AT, FÇ and MAL designed the research study. FS, AT and FÇ contributed to writing the original draft, review, and editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Attila Tanyi has presented parts of this paper at Corvinus University, Budapest (Hungary) and would like to thank the audience for their valuable feedback. He would also like to thank the Institute of Advanced Study at the Central European University (CEU IAS) as well as the Centre for Advanced Study at the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters (CAS) in Oslo for their support. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Project “Digital Trust and Teamwork” (ZW6-85007939) by Markus Launer at Ostfalia University of Applied Sciences.

Given his role as the Guest Editor, Frithiof Svenson had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Simon Jebsen.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.