1 Witten Institute for Family Business, University of Witten-Herdecke, 58455 Witten, Germany

2 CERIIM, Excelia Business School, 17000 La Rochelle, France

Abstract

Business families navigate complex social systems, oscillating between conflicting logics and expectations. This often leads to double bind communication, resulting in paradoxes and tensions. This qualitative study seeks to understand how these paradoxes emerge by examining the expectation structures within business families through a social systems-theoretical lens. We explore (1) how families manage the clash of family and business logics in communication, (2) how in-depth interviews reveal origins of paradoxical communication, and (3) how communication patterns and sense-making processes are shaped by different systems logics. Our study offers insights into the intricate relationships and paradoxes faced by business families.

Keywords

- social systems theory

- family business

- paradoxes

- communication

- decision-making

Almost 30 years ago, Charles Handy postulated the age of paradoxes. Paradoxes become even more frequent when resources are short and when pluralism and change occur (Handy, 1994). Given recent societal changes, ecological crises, and digitization challenges, the feeling of paradox has become omnipresent (Schneckenberg et al, 2023; Seidl et al, 2021). In business families, the feeling of paradox has never been absent. In fact, business families have been constantly dealing with the challenge of paradoxes for a considerable time (Combs et al, 2020; Jaskiewicz et al, 2017; Zellweger et al, 2012). The business family itself reveals a paradox, as it can be characterized as contradictory yet interrelated: on the one hand, it can be the greatest resource, or/and on the other hand, it can be the greatest danger for the family business (Ingram et al, 2016; Smith and Lewis, 2011; Suddaby and Jaskiewicz, 2020). The confrontation of family and business reveals the significant paradox of emotional attachment vs. rational calculus–constantly requiring oscillation between family and business logics. Consequently, this challenge causes interrelational frictions in the business family that may result in tensions, paradoxes, and highly emotional conflicts (Cunha et al, 2021a).

The demands for a scientific discourse that addresses relations and interdependency between family and business systems and their different logics have steadily increased recently (Odom et al, 2019; Combs et al, 2020; Kleve et al, 2020b). Despite broad agreement on the relevance of understanding the different social systems and their logics for the actors in family businesses and business families, the exploration of these systems in the communication of business families has yet to be examined thoroughly with empirical data. Moreover, most research has solely focused on quantitative studies or conceptual articles instead of qualitative approaches (Frank et al, 2017). We hence identified an incomplete picture of how different communication codes can be detected in the communication within business families and how they contribute to comprehending paradoxes and their emergence.

We aim to examine these situations of conflict and paradox by differentiating the family and business systems’ logics and their systemic expectation structures. By taking a closer look, we can unfold these paradoxical and ambivalent situations through their systemic communication and contexts. Therefore, the scope is on the family and the business systems, their interaction, and complex communication due to fundamentally different systems logics.

To address the gap, we qualitatively explored the following research questions:

(1) How do business families deal with the confrontation between different systems within their communication?

(2) How can communication be analyzed to enable the comprehension of paradoxical communication?

(3) How can communication patterns, expectation structures, and sense-making be examined through the lens of guiding distinctions (Roth et al, 2025) and functional differentiation based on a Luhmannian systems theory approach?

Our qualitative study provides insights into business families’ communication, showing different communication codes that derive from social systems logics.

Therefore, our study makes several contributions to research and practice. While previous research broadly focused on the theoretical and conceptual exploration of double bind and complex communication, in this study we unravel the communication of business families by differentiating the codification of their language that reveals direct as well as latent sense-making and expectation structures. In particular, we shed light on how different systems refer to systems logics that can be expressed through their communicative actions. For practitioners, we identify key communication codes that help untangle double binds that easily cause conflicts. This may help to structure communication and promote reflection on the communication styles of business family members.

In the following section, we review the literature on systems, double binds, and paradoxical communication in business families. We then introduce our theoretical framework and the foundation of Luhmannian systems theory that will help to understand the complexity of different social systems. Thirdly, we illustrate our methodology, describing our sample and research context for the case study and presenting our data collection and analysis. After that, we will present and discuss our findings. Finally, we conclude with practical contributions, limitations, and avenues for future research.

Business families face the complexity of three systems: family, business, and ownership (Combs et al, 2020; Habbershon et al, 2003; Sharma, 2004). As family businesses are passed down across generations, their structures grow more complex (Gersick et al, 1997; Jaffe, 2020; Kleve et al, 2020a; Zellweger et al, 2012). These families navigate social systems with varying norms and expectations (Arnold et al, 2023; Frank et al, 2017), balancing roles, interests, and logics (Combs et al, 2020). Decision-making in family businesses fosters agility and responsiveness (Baecker, 2001; Irava and Moores, 2010). Relationships within them constitute social capital, which can either strengthen resilience and value (Mokhber et al, 2017; Calabrò et al, 2021; Kraus et al, 2020; Zellweger et al, 2019) or lead to internal governance issues (Steier, 2001). Still, business families are pivotal in guiding governance structures, offering flexibility and rapid decision-making (Calabrò et al, 2021).

When family, business, and ownership systems are involved, decisions may be influenced by personal relationships and distorted communication (Dyer et al, 2009; Von Schlippe and Frank, 2013). This distortion often manifests as “double bind” communication (Litz, 2012), which leads to conflicts and tensions (Bateson et al, 1956; Watzlawick and Beavin, 1967; Sharma et al, 2003; Von Schlippe and Rüsen, 2024; Kleve et al, 2020b). Focusing on family systems can help understand these paradoxical communications (Fletcher et al, 2016; Frank et al, 2023). Systems theory offers a transdisciplinary framework to grasp the business family as a whole, considering both constellations between members and their contexts and environments (Baecker, 2006; Luhmann, 1995).

In business families, roles are assigned to each member regardless of age, with expectations tied not only to family purposes but also to business responsibilities. This introduces complexity as family and business systems interact (Von Schlippe and Frank, 2013). A core challenge is balancing family-first or business-first priorities, leading to the ever-present “double binds” (Litz, 2012; Schad et al, 2016) or “paradoxes of identity” (Cunha et al, 2021b) which arise from conflicting values and goals in perceived overlaps of family and business communication and create dilemmas (Chrisman et al, 2004). Consequently, family businesses face tensions, such as “tradition vs. innovation” and “merit vs. care”, paired with “paradoxes of purpose” and “paradoxes of inclusion”, that complicate decision-making (Cunha et al, 2021b, p. 252). Business family members pursue economic goals, while also striving to maintain personal autonomy and uphold family traditions (Ingram et al, 2016; Jaskiewicz et al, 2015).

Paradoxes consist of contradictory yet interrelated elements, justified by the persistent coexistence of incommensurable logics (Kleve et al, 2020a; Smith and Lewis, 2011). Researchers have identified various paradoxes, including “willingness-ability paradoxes”, the “embeddedness paradox”, or the “Oedipus paradox” (Barrett and Moores, 2020; Chrisman et al, 2015; De Massis et al, 2015; Ingram et al, 2016; Rondi et al, 2021; Suddaby and Jaskiewicz, 2020). These paradoxes influence decision-making and growth in businesses (Cunha and Putnam, 2019). Business family members need to balance factual requirements with the unique social dynamics of their families (Frank et al, 2023).

Recently, organization research has been shifting from an either/or logic to both/and, more/than, and neither/nor approaches, avoiding dualism (Roth et al, 2023; Schneckenberg et al, 2023). Trade-offs, often seen as mutually exclusive, are now viewed more flexibly (Ashforth et al, 2014; Gaim and Wåhlin, 2016; Gaim et al, 2022; Roth et al, 2023; Roth, 2024a). Generative paradoxes reveal that positive outcomes can arise from the interplay of opposing forces (Berti and Cunha, 2023; Putnam et al, 2016). In organizational settings, paradoxes manifest in rules like “Take the initiative/Don’t break the rules”, “Give immediate notice when mistakes occur/You will be punished if you make a mistake”, or “Cooperate/Compete” (Hennestad, 1990, p. 272). Moreover, flexible work arrangements can blur boundaries, creating new tensions (Putnam et al, 2014). Paradoxes such as being simultaneously sexualized and de-sexualized affect female employees (Berti and Simpson, 2021; Gherardi, 1994; Oakley, 2000; Wendt, 1995), and may also impact the other gender(s) similarly.

Exploring paradoxes in business families helps us understand how they manage contradictions and become assets when resolved. Researchers have found that handling these paradoxes drives adaptability, innovation, and problem-solving in family businesses (Erdogan et al, 2020; Filser et al, 2016).

The Luhmannian systems theory will serve to further examine the complex relations and often paradoxical communication within the business family (Kleve et al, 2020b; Luhmann, 1995).

Luhmann (2012) conceives of systems as observers that establish a distinction between themselves and their environment and thus differentiate themselves against their environment by their own observations. Thus, observation involves construction as it defines how the environment is shaped, and how it is differentiated from the system. Understanding systems in this respect means observing distinctions in operation (Roth, 2024b).

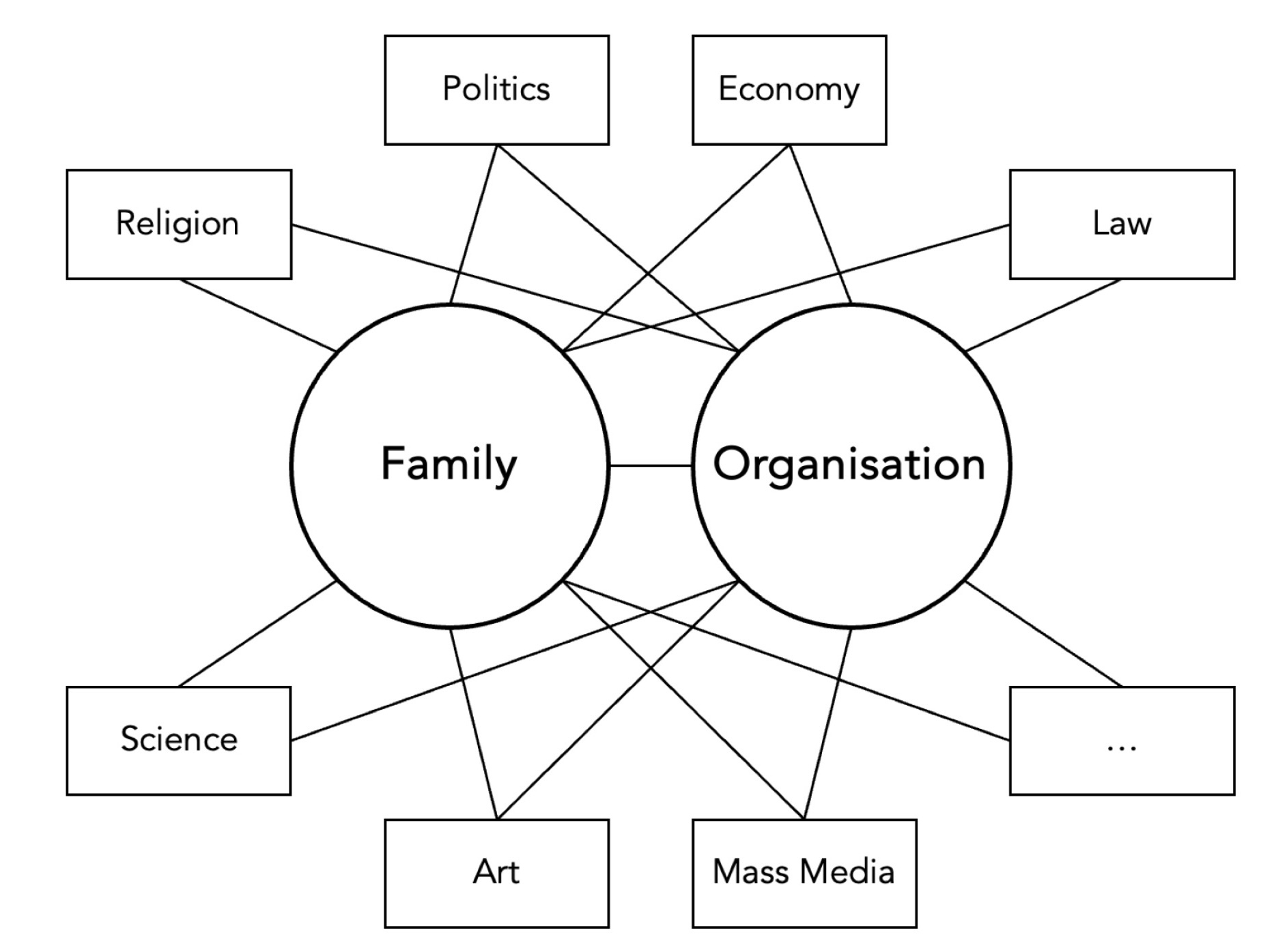

According to Luhmann (2005, 1977), the key distinctions of modern society are based on functional differentiation in modern society (Luhmann, 2005; Luhmann, 1977). This means that modern society is thought to be divided into various “function systems”, each with its unique way of coding communicating. These systems relate to domains such as politics, economy, religion, law, or education (Roth and Schutz, 2015). Like other subsystems of modern society, family businesses and business families must deal with a plurality of goals and expectations associated with the different function systems (Kleve et al, 2020b; Von Schlippe and Frank, 2013).

The main difference then is that businesses are organizations and thus systems of decision communication (Luhmann, 1995; Luhmann, 2018; Nassehi, 2005). Families, by contrast, are characterized by intimacy-related communication (Von Schlippe and Frank, 2013). While organizations only partially include individual persons via membership, families are expected to provide for the total inclusion of the “whole” person; and whereas members of an organization have an exit option, family relationships are interminable as they are defined by descent or adoption. Consequently, these two different types of systems evoke fundamentally different expectations.

For our analysis, it is hence important to keep these differences in mind when navigating the different logics of systems as different as families, organizations, and function systems (see Table 1).

| System | Communication code | Medium |

|---|---|---|

| Organization System | decision/non-decision | alternatives |

| Family System | intimate/indifferent | love |

| Economic System | payment/non-payment | money |

Luhmannian systems theory helps analyze the complex, paradoxical communication within business families (Kleve et al, 2020b; Luhmann, 1995), also providing insight into tensions arising from the differing forms organizational decision communication and family communication based on intimacy (Von Schlippe and Frank, 2013; Roth and Schutz, 2015; Kleve et al, 2020b). With growing interest in systems theory and qualitative research (Floris et al, 2020; Ingram et al, 2016), we used the former perspective for our qualitative analysis. Through semi-structured interviews with “Next-Generation” business family members, we sought to uncover patterns and codes within their communication (Canovi et al, 2023). By gathering personal narratives, we aimed to understand how business family members navigate paradoxes and ambiguous communication (Fivush, 2019; Yin, 2015) resulting from tacit or explicit references to different types of systems, namely organization, family, and function systems such as the economy. This approach also helped to uncover symbolic meanings behind these communications (Berti and Simpson, 2021).

Our research design followed principles of induction and abduction to generate novel findings (Gioia et al, 2013; Timmermans and Tavory, 2012; Weick, 1995). We used both empirical evidence and theory to explore ambiguous communication in business families (Alvesson and Kärreman, 2007). By focusing on communicative nuances, we identified mechanisms for managing paradoxes through a comparative case design (Yin, 2015). Based on prior research, we assume business family members have developed strategies to handle these paradoxes using different systems logics.

The semi-structured interviews, in which three different theme categories served as guidance throughout the interview. The first theme category contained (A) First experiences in the (business) family, including questions about the upbringing and socialization in the family, in the environment the participants were raised, specific roles and role expectations from family members, and first experiences and specific narrations, in which the participants realized that their family could be identified as a “business family member”. During the first interview phase, the interviewers aimed to create a pleasant atmosphere with rather convenient questions to be answered. The second theme category contained (B) Confrontation with the family, the business, and the ownership. This category covered questions belonging to the interplay and encounter of different systems, contexts, and their logics. We asked about the “specialty” of this family type, and to what extent these contexts can perceived as different and if there are specific different components (e.g., events of either family or of the family business, differentiation between roles; who belongs to the business family member as in charge, operational roles, strategical or consulting roles, or only family roles). In this phase, participants have related to different role expectations and responsibilities towards different stakeholders within the family and the business, and the communication with one another. All participants described the perceived distinctions between the family members, their roles, and personalities.

The third category contained (C) Paradoxes and conflicts, including questions about ambiguity, double binds, contradictory logics, and conflicting communication that arises from various interacting systems. In this category, we asked questions about the confrontation with paradoxes and dealing with them (i.e., the communication between the family and business stakeholders, the appearance of different logics, acting as a father or son, or as a business partner). We also asked to what extent the generation plays a role in the conflicts, communication “rules”, “strategies”, or “routines” when paradoxes appear. Further questions referred to different levels and if the participants try to differentiate between personal/familial level or subject level.

We aim to provide in-depth insights into paradoxical communication due to divergent systems logics and expectations in business families. Considering the applied methodology and the theoretical background, Next-Generation business family members will specifically serve as a sample group. We focus on this group, as the Next-Generation of business family members find themselves in a rather transformational phase where additional systems are increasingly coming together on a very “conscious level”. For children mostly, the family system is the most apparent; within functional differentiations in modern society children already become frequently involved with other function systems, for example, the educational system and health system, such as in kindergarten, school, or at doctor’s appointments.

We interviewed eight family members of 23 and 35 years old out of five cases, conducted a group discussion with three other family members, and also conducted interviews with family business experts beforehand (see current sample structure below in Table 2). The face-to-face and video interviews lasted an average of 95 minutes (max. 120 minutes). We recorded and transcribed all interviews for the following data analysis.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Total | |

| Sector | Drilling tools | Machine for coffee industry | Printing | Cosmetics | Automotive tools and machines | |

| Generation | 3rd | 3rd | 5th | 2nd | 2nd | |

| Position of the business family | Father is CEO and running the business | Father is CEO and running the business | Father is CEO and running the business | Mother and sister are CEO and running the business | Father is CEO and running the business | |

| Number of employees | 72 | 1500 | 640 | 12 | 75 | |

| Position in the business family | Successor | Planning to succeed | Planning to succeed | Successor | Successor | |

| Number of participants | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | n = 8 |

The grounded theory method aims to explore phenomena and conceptualize processes and social interactions. Observing patterns and social behavior, we specifically identified expectations, structures, and systemic logics with distinct symbolically generalized media and communication codes. In that sense, we used the interviewees’ stories and spontaneous answers to detect their communication and decision-making processes in an environment with rather divergent logics and paradoxes. The study is centred in an inductive grounded theory approach following Gioia et al (2013). We follow this iterative process of generating as well as evaluating theoretical and empirical insights, which seems fruitful with the exploration of this phenomenon.

In each case, we specifically asked what makes the family a family and/or how they would describe the differences between the different poles of family and business. Moreover, we wanted to know how they experience contradictions, how they would describe them, and how they deal with them.

For our analysis, we followed an interpretive approach as recommended by the grounded theory methodology (Corley and Gioia, 2004; Gioia et al, 2013). Through the analysis, we aimed to identify how systems can be examined within the communication of business family members due to the application of specific codes, and secondly, to unravel the paradoxes, ambivalences, and double binds through these partially divergent systems. In the thematic analysis, we systematically identified communication patterns in textual segments of a specific theme representing higher-level key thematic areas (Flick, 2014). We conducted the three coding stages as an iterative research process by developing salient themes that further result in aggregate theorizing frameworks (Locke et al, 2008).

We initially started with the open-coding phase, where we selected text segments referring to attributes depicting the specific systems of family, organization, business (economic), ownership/(legal), and politics. We searched for any attributes relating to the respective code-specific language, i.e., decision-oriented communication codes (organization), profit-oriented codes (economy), intimacy-oriented (family) codes, or rule-oriented codes (legal system). We aimed to detect the different nuances within the communication codes that would highlight the respective system, and which would, later on, lead us to the paradox and double binds. In-vivo coding helped us to establish a primary coding procedure by profoundly analysing the data collection in each case. We discovered the occurrence of different systems by closely focusing on the exact communication codes hinting at the respective systems. Not only did we pay attention to the participants’ narratives on childhood memories and growing up in a “special” family, but also to the differentiation with other systems and environments of the participants, as well as their “work” positions, role expectations, and family and business structures.

Moreover, we included the participants’ narrations of their goals and purpose, as well as their perception of “being a member” (identity) of a business family. In this stage, we searched for all information relative to any family and business contexts and “business-family” contexts. We thus built an “insider perspective” of authentic lived experiences that reveal the different systems within family businesses (García and Welter, 2013).

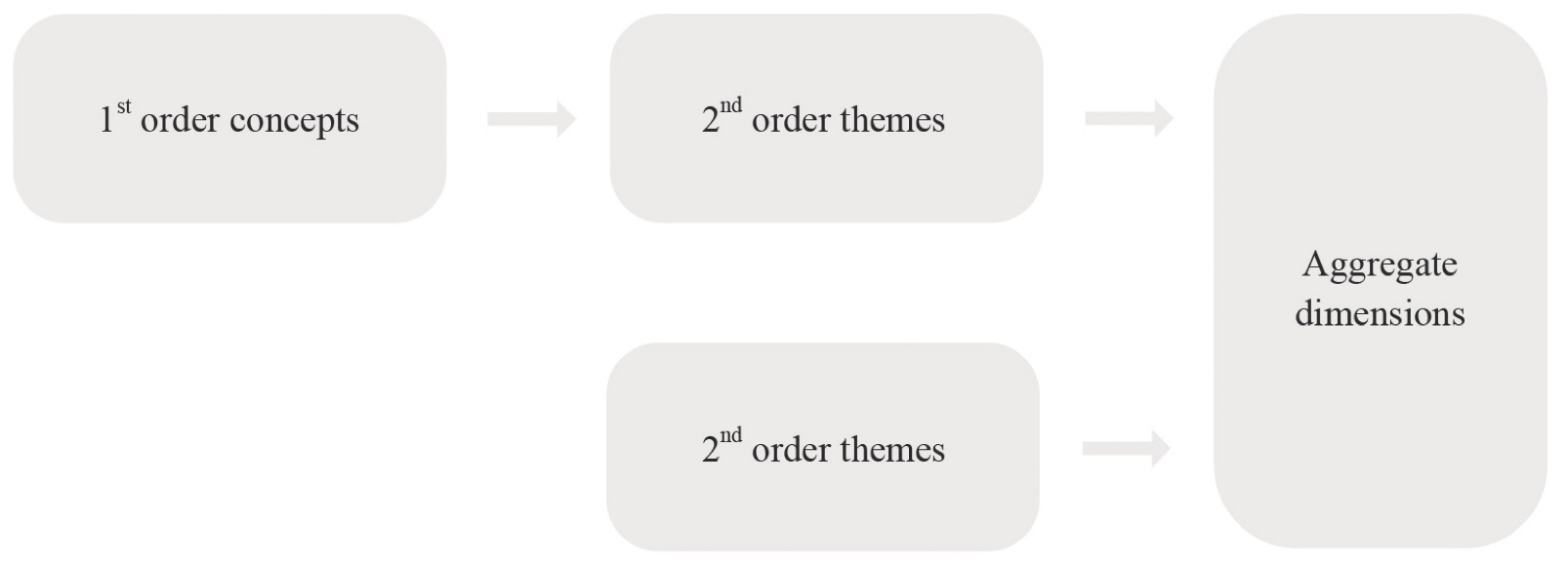

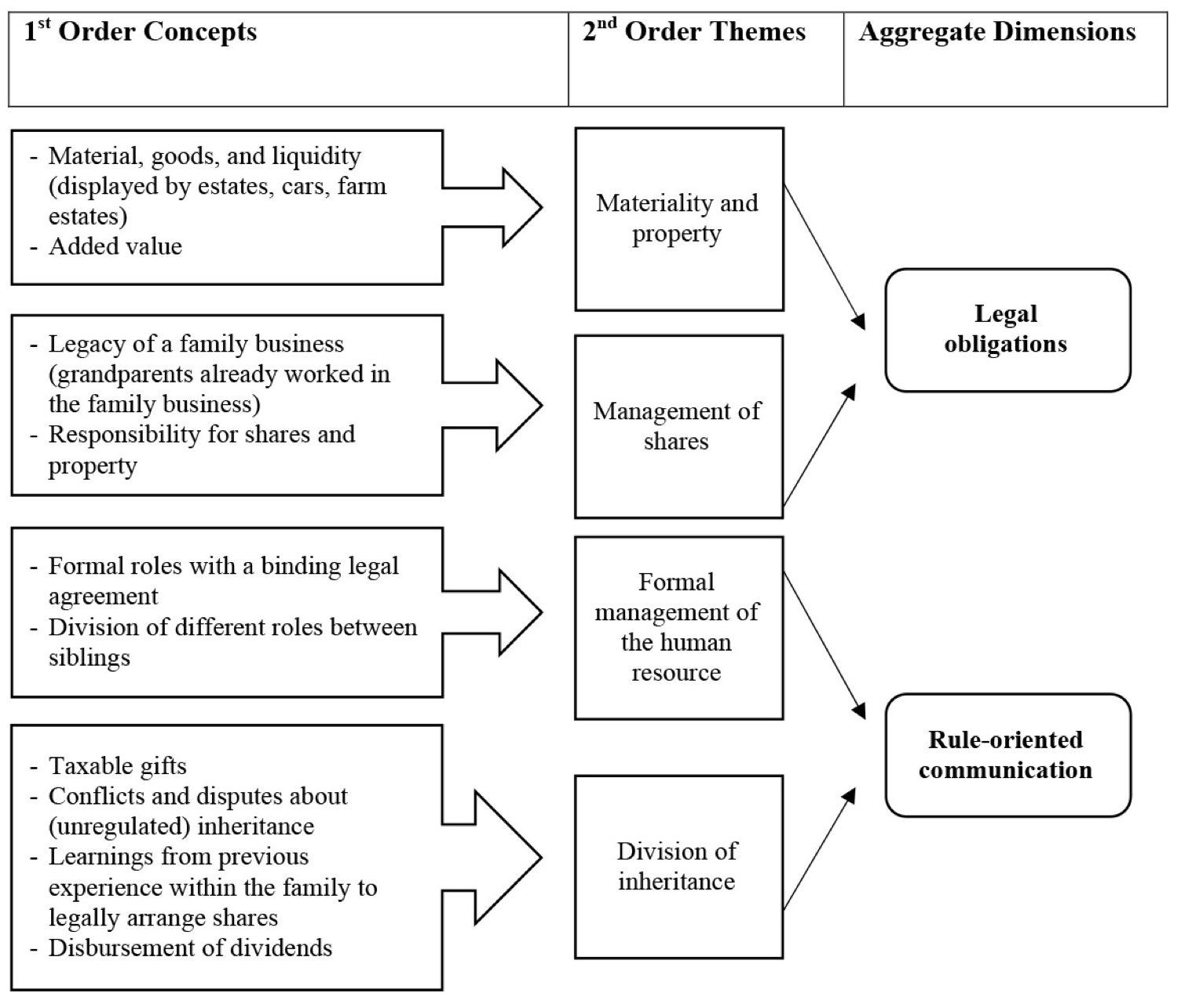

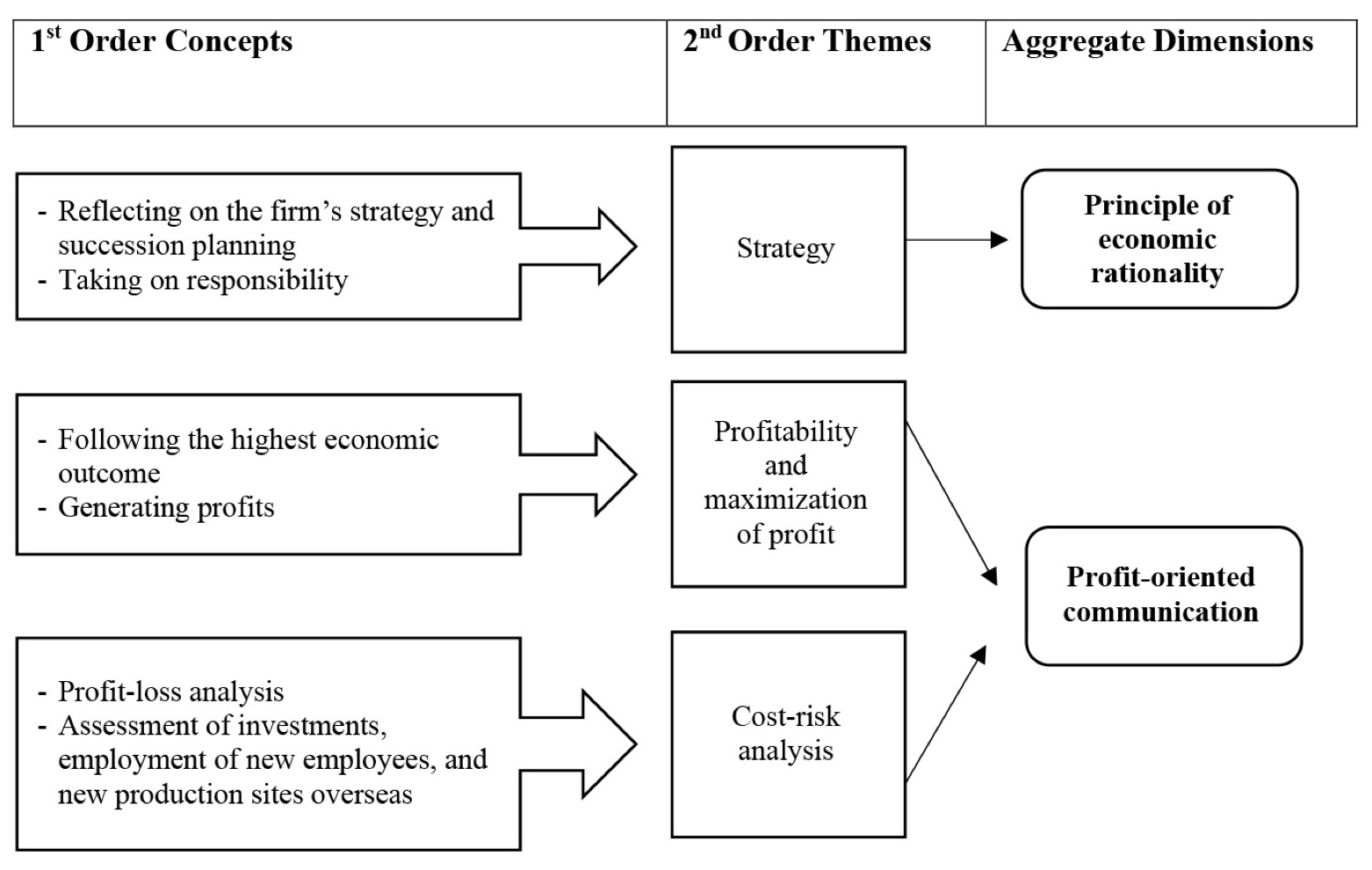

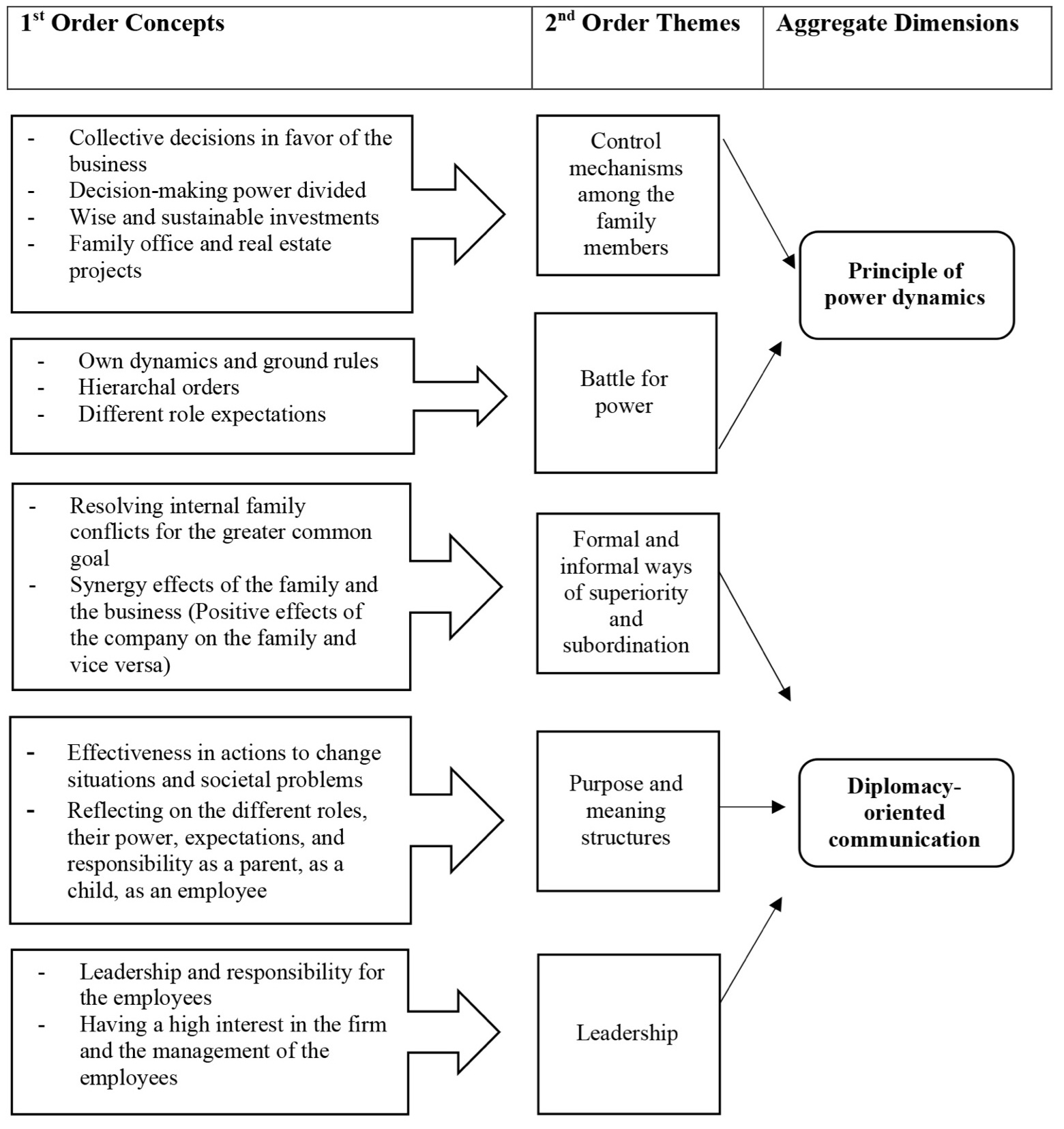

In the second coding stage, we used extant theoretical concepts to inform our coding (Gioia et al, 2013). The data analysis structure is illustrated in Fig. 1, which shows the first-order concepts, second-order themes, and aggregate dimensions(Gioia et al, 2013). It shows the synthesized categories of the first raw analyzed data (first-order concepts), followed by a more differentiated and structured analysis through the second-order themes.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Visualization of the planned data structure.

In the third stage, we synthesized the main themes into aggregate dimensions that reveal the different principles, mechanisms, and media that contribute to structuring the communication of the respective systems.

Drawing on the data analysis, the following section presents our findings relative to the successors’ experiences with managing different systems logics, double binds, and emerging paradoxical communication.

In general, we used inductive qualitative techniques, including multiple readings of the transcripts and listening to the pronunciations and tones of the participants. We inductively developed codes and categories and captured and monitored them within Excel sheets. While iteratively employing our data, we applied cross-reading and cross-coding techniques (Huberman and Miles, 1994).

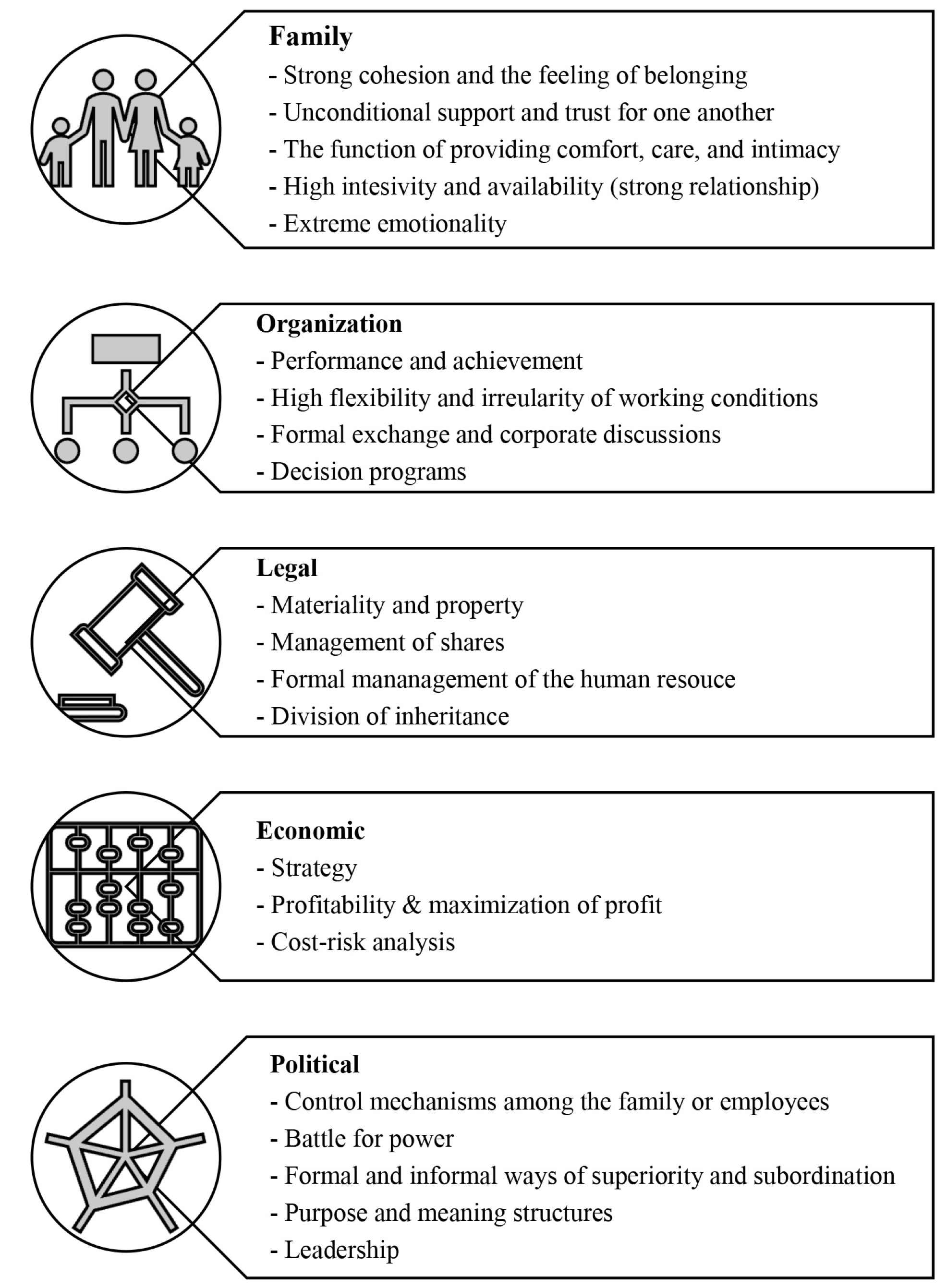

In this section, we present the key findings of our analysis to reveal the different systems’ logics and expectation structures identified in the data collection within the communicative acts. Moreover, we emphasize the latent structures of meaning that underlie social interaction within different social systems. In the following pages, we synthesize our findings, which are categorized by the communication distinctions of the following systems: (a) the family system, (b) the organization system, (c) the legal system, (d) the economic system, (e) the political system.

Please see Table 3 for illustrative quotes related to the specific systems differentiation.

| Differentiation of Systems | ||

| The Family System | 2nd Order Themes | |

| “We are a normal family. We also have normal arguments like everyone else, and normal things.” (T1) | Strong cohesion | |

| “The family as such is something very private, it is the interpersonal without any hidden agenda, or any ulterior motive, or common goal.” (T2) | The feeling of belonging | |

| “You know situations that the other person doesn’t like and where the other person doesn’t feel so comfortable. And you know each other. So, you provide 100% support in a completely different way or you steer it a little in other directions.” (T5) | Unconditional support and trust in one another | |

| “My sister is my best friend and is my contact person and vice versa. That means that if there’s something going on and even if we’ve just somehow managed to shut each other up, but then there’s a situation and you need help, everything else is forgotten.” (T6) | The function of providing comfort, care, and intimacy | |

| “That’s because my little brother and I are two years apart. We are best friends and have always done everything together and will always do things together in the future.” (T4) | High intensity and availability | |

| “We argue about it, of course, and it’s certainly not always on a factual level. I would be lying if I said that was the case.” (T7) | Extreme emotionality | |

| The Organization System | ||

| “My father used to go away a lot, so he was away on business trips for half the year and that showed me that my father does a better job than others.” (T5) | Performance and achievement | |

| “You sometimes have to go to work spontaneously, sometimes it’s longer and sometimes at the weekend.” (T6) | High flexibility and irregularity of working conditions | |

| “We have regular meetings together, so we meet about once a month for family jour fixe, where we talk about company figures or upcoming projects.” (T2) | Formal exchange and corporate discussions | |

| “Now that I think about it, it’s still slightly patriarchal. In other words, the decision, the final say is made by my father, who has overall responsibility for the whole thing.” (T2) | Decision programs | |

| The Legal System | ||

| “We have owned a few properties and at some point, as we got older, we realized that a bit, but it was never made a big deal of, quite the opposite. We didn’t grow up in a rural area in Germany either, and everyone knows a bit about growing up in a village, which is a bit different. Buying a new car might be found out very quickly [by people in a village].” (T6) | Materiality and property | |

| “We have established a foundation, an entrepreneurial foundation, a family foundation that takes the entrepreneurial legacy out of the company, expropriates it and directs it in a civilized manner.” (T2) | Management of shares | |

| “We defined who is part of the corporate family, rules for conflicts, and who can assume corporate responsibility.” (T2) | Formal management of the human resource | |

| “I could become a managing director or a successor in the company, but this ownership obliges me and this responsibility or what my father told me from my grandfather. He said ‘So I’m giving you the responsibility of the employees’, so that’s, of course, more impressions that come from outside and feel the impact.” (T5) | Division of inheritance | |

| “So, the business family is always in the context of the company. That means you have a certain shared responsibility, you have a certain shared tradition, also because the company exists and you continue to run it together.” (T2) | ||

| The Economic System | ||

| “And the aim is of course to make it as sustainable and as long-lasting as possible and to actually leave something behind for future generations.” (T6) | Strategy | |

| “It’s about creating added value.” (T3) | Profitability and maximization of profit | |

| “We created remuneration systems.” (T2) | ||

| “Sometimes that’s a bit of a conflict that you have for yourself (employing someone). You can understand it, you can relate to it and everyone should have the right to feel the same way. But as I said, it’s simply difficult from the employer’s point of view, because, at the end of the day, you still have to work.” (T7) | Cost-risk analysis | |

| The Political System | ||

| “Exactly, the difference is that my father still decides a lot on his own, whereas I think we want to decide together because we also have siblings, of course. I don’t know whether that’s necessarily just because we want to share the responsibility a bit, or whether we also want to listen to the expert knowledge or the opinion of the siblings or the advisors or others.” (T3) | Control mechanisms among the family members | |

| “We have a business family that tried to resolve internal family conflicts in order to pursue the greater common goal. In other words, this company, the business family, can have a positive effect on the emotional family.” (T2) | Battle for power | |

| “Accordingly, the proportion of informal, informal exchanges in the conversations. In other words, my little brother is quite loud. And the loudest one often wins. If he wants to bring things to me and to others, then he brings them in first because he’s louder.” (T3) | Formal and informal ways of superiority and subordination | |

| “Then you get to know the company and realize, OK, this is a family legacy somewhere. My grandparents worked there, my great-grandparents worked there and so on and so forth.” (T2) | Purpose and meaning structures | |

| “You have a personnel responsibility, many who are dependent on a paycheck and many people who have been with the company for a long time and have a family relationship with the company.” (T2) | Leadership | |

Our analysis indicates that the social systems of family, business, and law can be differentiated through their different role expectations, functions, and logic. We analyzed the participants’ answers concerning their different understandings of the systems and the attributes of how the business family members differentiate the respective systems. Our findings suggest business family members differentiate the systems through their distinct logic and function.

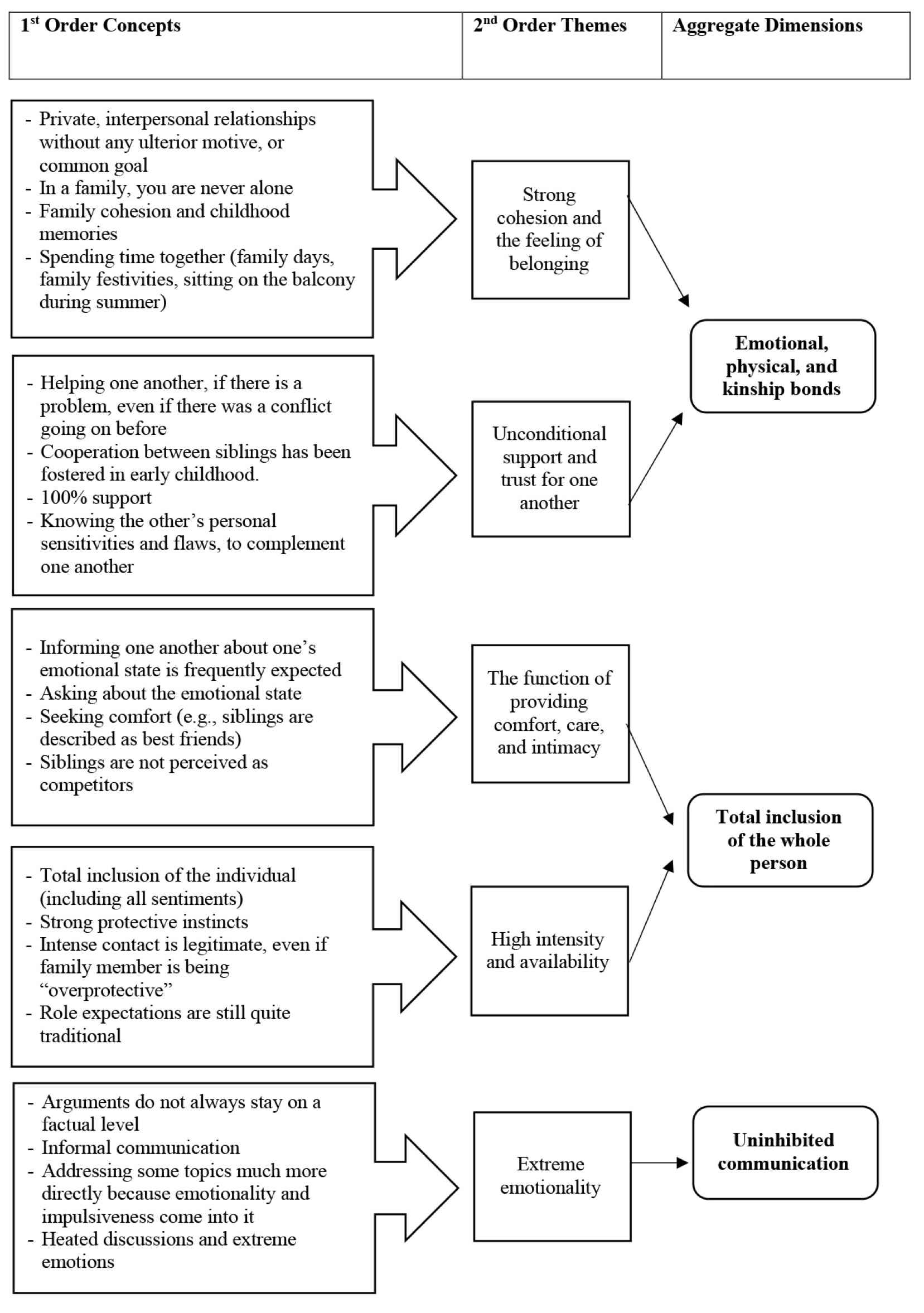

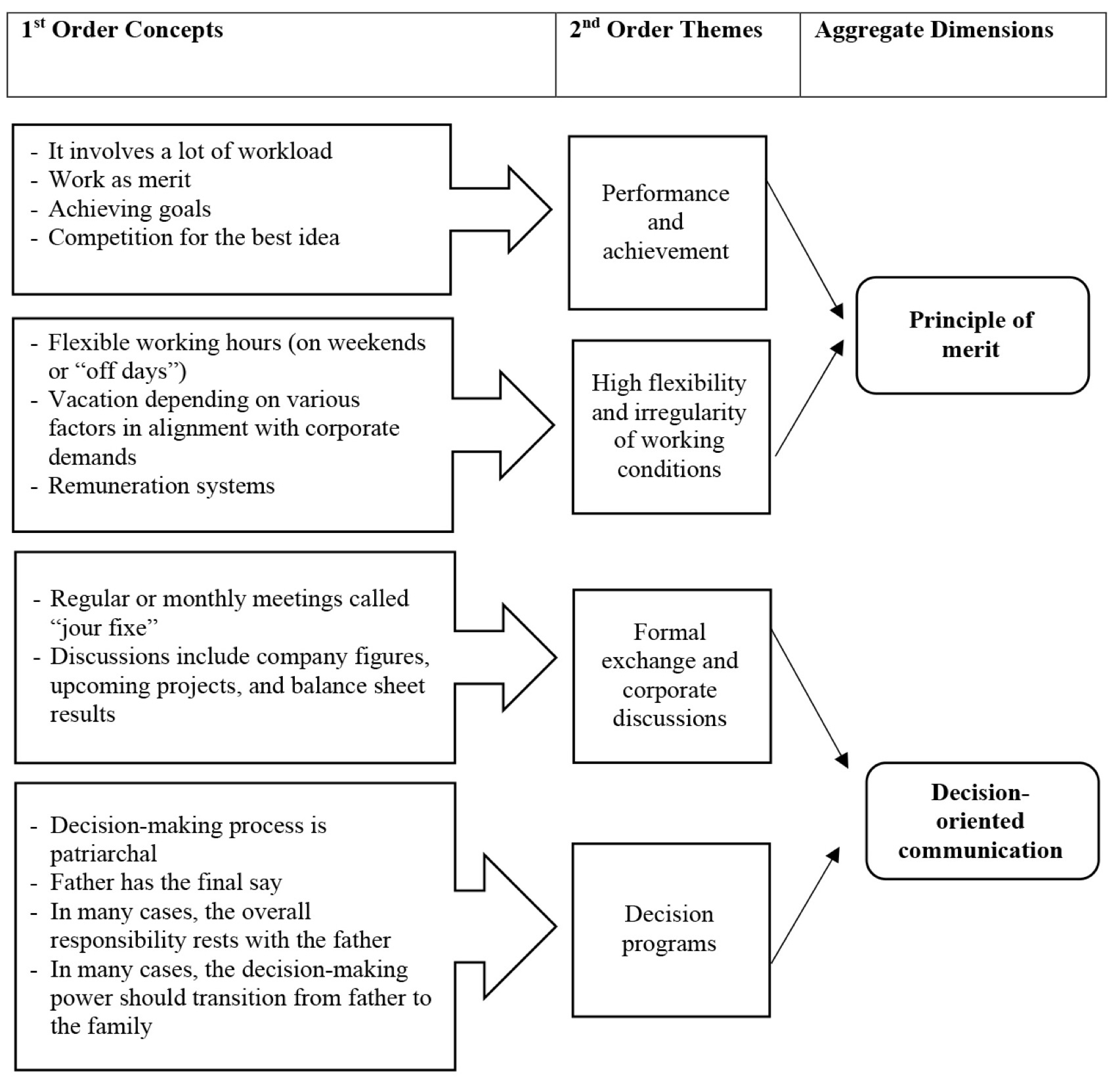

Based on our analysis and the focus on aspects that specifically point to the system’s characteristics, we have developed a framework for revealing the systems’ logics and expectation structures, depicted in Figs. 2,3,4,5,6. Additionally, we have included selected interview quotes that support our analysis and the resulting aspects of the framework.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The Family System – Differentiation of communication logics.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The Organization System – Differentiation of communication logics.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The Legal System – Differentiation of communication logics.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

The Economic System – Differentiation of communication logics.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

The Political System – Differentiation of communication logics.

Based on our analysis, we have identified the aggregate themes that specifically characterize family communication. Analyzing the communication codes centered in intimacy-oriented systems logic, the following aggregate dimensions appeared: (1) Emotional, physical, and kinship bonds, (2) Total inclusion of the whole person, and (3) Uninhibited communication.

Our interviews show that all business family members perceive “the family” as natural and a given. Asking the interviewees about their experiences within their particular type of family–being born into a family that is settled in a family business context–all interviewees have the perception of living a natural family life, as one participant stated:

“We are a normal family. We also have normal arguments like everyone else and do normal things.” (T1)

Most participants told us about a harmonious life and a close family bond since early childhood. Not only the emotional closeness but also the physical closeness characterizes the strong cohesion (second-order theme) in the families. Significantly, the close relationships between the siblings play a central role in the family. When we asked what attributes belong to a family “definition”, one interviewee described it as follows:

“The family as such is something very private; it is the interpersonal without any hidden agenda, or any ulterior motive, or common goal.” (T2)

This quote already hints at the crucial differentiation between the family and the business. It also refers to a family’s primary function, providing the feeling of belonging (second-order theme): “In a family, you are never alone.” (T1)

Moreover, most of the interviewees talked about regular family gatherings and family celebrations, which both involve formal and informal spontaneous gatherings (e.g., birthdays, recent summer vacations, “family days”, “a sibling day”, or “sitting on the balcony enjoying summer nights together”).

In our analysis, the interviewees told many stories–particularly about their siblings – about how they felt they could rely on one another and give as well as receive support, even if there had been an ongoing conflict before. Some of the interviewees highlighted the fact that they do not feel any competition or rivalry.

One emphasized the role of the parents who really “pushed cohesion” instead of “pushing rivalry” while growing up and compared this socialization to that of other school friends. Instead, they root for one another at school sports matches and show support for each other. We synthesized this theme as unconditional support and trust for one another (second-order theme).

One interviewee described not only the unconditional support but also the capability of the siblings to “read the feelings” of one another, where one notices discomfort and acts to harmonize the situation and make the other feel comfortable again.

“You know, situations that the other person doesn’t like and where the other person doesn’t feel so comfortable. And you know each other. So, you provide 100% support in a completely different way, or you steer it a little in other directions.” (T5)

Another interviewee explains that the relationship in the family is highly characterized by trust and refers to the long bond of kinship. This was described as the long period of knowing and living together: “We know one another for so long” that there is a “shared foundation.” (T4)

In another case, the elements of trust and reliability were perceived as ambivalent and not steadily provided, as the parents were often busy.

“There were times when my parents simply didn’t have the capacity to be there for us, but today, I would definitely say I could call them at any time. I’d say it’s one of my privileges in terms of having children anyway; no matter what happens, I can always be at my parents’ house with my partner and one, three, or four children, and they will do everything they can to accommodate us.” (T5)

This perception shows that trust and reliability cannot be seen as a given, even if there is an awareness of belonging to a family. Trust needs to be constantly and steadily built by the actions of the family members to create trustworthiness. This quote also implies financial and social provision.

In another assumption of family characteristics, the feelings of trust and reliability can be understood as a social expectation structure that may be conceptualized in the sense of a “code of ethics”. Among family members, the interviewee describes it as part of the socialization in a family. Therefore, it is socially expected and it is a latent demand of being a parent or a family member to provide care and support within the family:

“So, in terms of socialization, it has to be that way, so you don’t leave siblings or family members behind, so I think it’s subconscious, not that our parents raised us like that, or I don’t know what it’s like with my parents. But something like that, family is important.” (T5)

Unconditional support is very important to family members and can be regarded as one of the most central demands in a family. Hinting at the “subconscious” level could represent the significance of traditional values and socially accepted practices that have been passed on from one generation to another.

Besides support and trust, the interviewees referred to the importance of informing other family members of their emotional state. In order to maintain strong connections within the family, the interviewees described certain practices that refer to emotions and comfort. Therefore, the family members see it as natural to inform one another about their emotional states. By openly discussing how they feel, the family members create an environment where emotions are acknowledged and valued.

“My sister is my best friend and is my contact person and vice versa. That means that if there’s something going on and even if we’ve just somehow managed to shut each other up, but then there’s a situation and you need help, everything else is forgotten.” (T6)

Showing genuine interest in how someone is feeling demonstrates care and concern for well-being. By actively engaging in these intimacy-creating conversations, the family members show that they value each other’s emotions and make them their priority.

“While in the family, an expectation of the family, me personally, well, because I’m further away now, and sometimes I don’t really notice what’s going on. So, there’s a kind of communicative expectation that comes from me at least.” (T2)

One interviewee states that one specific expectation in their family is to actively ask “What’s going on?”. The person does not know whether this expectation only refers to the personal situation or also the physical distance, which requires even more intense communication.

Moreover, all interviewees spoke of their family’s willingness to provide comfort when necessary. They talked about this core function of the family, which is the function of providing comfort, care, and intimacy (second-order theme), and which has been often perceived as an implicitly expected demand in the family.

The analysis also revealed the intensity of the relationship between the family members. Most of the interviewees spoke about positive and strong relationships with their families. The female interviewees in particular had an intimate and a high-quality relationship.

“With her, she is a little bit of an over protector. You haven’t been in touch for three hours. Is everything okay? Yes.” (T6)

As illustrated in the quote above, relationships between family members are characterized by a high demand for the person and an interest in their actions and availability. Compared to other persons and groups, in families, the question of where someone is or what the other is doing is the most central motive. In addition, it can be viewed as the one fundamental question that the other is expected to respond to quickly, promptly, and sincerely. In families, very often, all actions are aligned with the members. Another interviewee also refers to the solid and intimate relationship he has with his brother and mentions that they do everything together and will continue to do things together in the future. It is worth mentioning that this relationship is of course not a romantic relationship; however, it is still characterized by a deep intensity of the relationship and involvement of the person in their life. Another participant also referred to their constant contact and communication with their sister:

“Oh yes, I actually have it when I’m somewhere else. I always have my cell phone with me. Because I just do. That you talk on the phone a lot. My sister and I talk on the phone what feel like 140 times a day, especially during the week.” (T6)

Based on our analysis, the role expectations were still very traditional. All interviewees stated that their father does not embody the role of a caregiver but instead takes on the role of a provider who works a lot and is not often available. However, it was not evaluated as a negative aspect and it didn’t seem to affect the interviewees’ relationships with their fathers. In some cases, they (i.e., the male interviewees) give the impression of a father who is also doing his best, which is appreciated by the offspring:

“And I could never really define what my father does for a living. He’s somehow always gone all day.” (T3)

Although all interviewees talked about their fathers’ frequent absences, it became evident in every case that the family focuses on the children’s happiness instead of prioritizing their career goals.

“The goal of my parents and now also of my father, in this case, is that we somehow live a happy life and do what we can and that you can only be good at what you want to do.” (T3)

Besides this, children can be seen as one of the main priorities for the parents. In one case, it was highlighted that the interviewee went through a difficult time during adolescence.

All these elements have been categorized as high intensity and availability (second-order theme), related to the aggregate dimension of the total inclusion of the whole person.

We have also identified the patterns of very emotional communication that can be differentiated from conversations in other systems. In addition, we identified extreme emotionality as a second-order theme relating to the family system. The great majority talked about emotional rather than rational conversations, particularly during conflicts.

“We argue about it, of course, and it’s certainly not always on a factual level. I would be lying if I said that was the case.” (T7)

Fig. 2 describes the emerging second-order themes as well as the aggregate dimensions resulting from the family system.

Based on our analysis, we have also found patterns that are explicitly related to the organization system, centered in a decision-oriented systems logic. The following aggregate dimensions appeared: (1) Principle of merit and (2) Decision-oriented communication.

All interviewees emphasized the high level of performance and achievement (second-order theme) of their respective working parents/family members. Even from early childhood onwards, the interviewees noticed the high workload of their parents. Almost everyone mentioned that they did not understand what their father’s job was. One put it as follows:

“As I said, I’ve always noticed that Dad isn’t around that much, always comes back relatively late in the evening and then says things that I can’t really relate to or understand.” (T3)

All interviewees talked about their childhood memories. They highlighted that they never knew how to explain their father’s job. Even though they could not specify the job in detail, they felt like there was a high complexity and performance related to it:

“My father used to go away a lot, so he was away on business trips for half the year and that showed me that my father does a better job than others.” (T5)

Besides the workload, the business family members speak of high flexibility and irregularity of working conditions (second-order theme) regarding working in the family business. All interviewees link the capability to be flexible with working long hours in the family business. On the one hand, these flexible working conditions were described as working on weekends and “spontaneously”, and were legitimated by the family business demands. On the other hand, the interviewees perceived these working conditions to be linked to a “good work-life balance” as one participant mentioned:

“My father is quite good at that (Work-Life Balance), he sometimes goes to the office at lunchtime, but he’s also there on Saturdays and Sundays.” (T2)

In general, the interviewees referred to the father’s/mother’s work in the family business as an outstanding achievement, worthy of recognition based on the principle of merit. As an interviewer, it became apparent that all the interviewees were proud of their father’s/mother’s achievements for and contributions to the business.

Furthermore, the communication related to the organization system can be differentiated from the family system communication codes. At first, the interviewees needed help distinguishing between family and organizational communication. When delving into the narratives and talking about everyday experiences and routines, the interviewees discussed regular and monthly meetings, which were both formally and informally demanded. There was an implicit expectation structure communicated by the family “to keep yourself informed of the business”, defined as a “communicative expectation” (T2). In these regular meetings, the business families discuss company figures, upcoming projects, and balance sheets. These patterns could be identified as formal exchange and corporate discussions (second-order theme).

Compared to the conversation focused on family system-related elements, business communication with the father/mother in charge of the family business was perceived as pleasant yet goal-oriented. In particular, the succeeding members discussed much with their father/mother. However, when it came to decision-making, it was still the father/mother’s decision programs (second-order theme).

“As things stand now, my father is the one who gives the input and who ultimately makes the decisions.” (T3)

The interviewees all referred to their father/mother, who has the “overall responsibility for the whole enterprise” (T2). Most of the family businesses were characterized by patriarchal leadership styles, which left all interviewees thoughtful and reflective about their parents’ decision structures. All highlighted their significant codetermination, yet some realized their limited scope of action in the end. As an interviewer, in this context, I noticed that the perceived situations were key aspects within the differentiation of the systems’ logics. Even though all participants felt very much included in the business’ operations and participated in the decision-making, they became aware of the principles of hierarchies and specific decision-making structures.

In this section, we present the communication patterns that we have identified with the legal system’s logic and the aggregated dimensions: (1) Legal obligations and (2) Rule-oriented communication.

Legal-related communication can be identified as a central second-order theme in discussions about materiality and property. In each interview, even though the questions of what ownership entails were not directly posed, every participant discussed the unique emotions associated with “possessing” belongings. They recalled living in “larger homes” and having “new cars” from a young age. Notably, they viewed this as normal rather than extravagant yet acknowledged that growing up surrounded by material wealth set them apart from other children who did not have access to such resources.

In each case, the interviewed individuals clearly distinguished between various locations and properties. They discussed their residences, workplaces, the family business production sites, and countries and regions. Some even mentioned family estates and horse farms where they resided. One interviewee talked about growing up as follows:

“We have owned a few properties and at some point, as we got older, we realized that a bit, but it was never made a big deal of, quite the opposite. We didn’t grow up in a rural area in Germany either, and everyone knows a bit about growing up in a village, which is a bit different. Buying a new car might be found out very quickly [by people in a village].” (T6)

All interviewees highlighted how property and materialistic belongings brought financial stability. This component played a significant role in their childhoods and contributed to their career decisions. They were aware of the privilege associated with their financial situation, which allowed them greater freedom to choose their paths.

“…how privileged I grew up because I never had many of these worries, I never heard my parents arguing about money or anything like that, so I realized that I had to do the right thing.” (T5)

During the interviews, many of the participants described the significance of property and shares, as they aim to successfully manage these and find sustainable ways to invest. Therefore, management of shares was identified as a second-order theme.

An interviewee stresses the sense of responsibility due to the legal power to possess shares and belongings. He also connects the responsibility to the obligation to make informed decisions for the benefit of society. However, another interviewee disagrees with the saying and justifies it with specific character traits depending on the individual, as he explained:

“Property entails responsibility. I think that always depends a bit on the character of the person! I have the feeling that the prevailing opinion, especially in family businesses, is often that ownership is an obligation, but for me, this doesn’t create pressure along the lines of ‘I have to’, but rather ‘I appreciate it’.” (T3)

Furthermore, we identified formal management of the human resource as a second-order theme. The interviewees highlighted the differentiation of social roles linked to formal and binding agreements. Interviewees commented that they have set up different structures and formal agreements as succession processes evolved, and the legacy of the family business passed from second generation to third generation and onwards. In this context, they discuss and set up numerous legal and formal agreements such as remuneration systems, who is part of the business family, and who can provide corporate responsibility. In the arrangement of succession, most interviewees emphasized the possibility of several potential siblings who are formally considered to succeed.

Another second-order theme is the division of inheritance, which is a core element of legal systems logic. In all interviews, the role of inheritance appeared as a major legal communication pattern. Especially during the succession process or change of leadership, legally relevant communication patterns, such as taxable gifts or disbursements of dividends, belong to the legal system.

In this vein, the communication medium of the legal system becomes the most apparent in situations of “regulated” or “unregulated” inheritance. Additionally, experiences among the different family branches and learning from the narrations of prior conflicts and disputes about inheritance affect decision-making. One interviewee describes it as follows:

“But after my grandfather’s death, this war of inheritance got going. We had an aunt who blocked a lot of things, or basically, there were a lot of arguments about who did what, how, and where.” (T2)

In this part, we demonstrate the communication patterns identified with the economic system’s logic and the aggregated dimensions: (1) Principle of economic rationality and (2) Profit-oriented communication.

Actions within the economic system have been perceived as either working operationally or strategically. Most interviewees gained their initial exposure to the family business through internships early in their academic journey. All interviewees emphasized the importance of strategically contributing to decision-making based on their experiences.

“Learning to be more involved, to come up with my own ideas, which were then implemented. Which were incredibly well received. That was great, of course, because at least once you have something like that, it’s a bit like an addiction.” (T6)

Implementing new ideas and reflecting on the firm’s strategy was one major economic communication pattern that appeared as a second-order theme in most of the interviews. Strategic mechanisms have been described as significantly relevant to accomplishing the company’s goals.

Furthermore, we found communication patterns that specifically referred to the profitability and maximization of profit, which is a second-order theme. The successors and potential successors all highlighted the significance of economic outcomes and the business’s goal of generating profits. They not only talked about the situations of economic crises but also mentioned the phases of prosperity and profit maximization of their family business as a central goal.

Another important aspect is the cost-risk analysis as a second-order theme. The interviewees talked about the cost-risk analysis of different investments relating to the recruitment of new employees or the acquisition of products, machines, or new production sites. One described the difficulty of demands while recruiting new employees for a specific position:

“Sometimes that’s a bit of a conflict that you have for yourself. You can understand it, you can relate to it and everyone should have the right to feel the same way. But as I said, it’s simply difficult from the employer’s point of view and then you can influence your state of mind again, because, at the end of the day, you still have to work.” (T7)

The interviewees portrayed their decision-making along economic expectation structures and profitable targets for the firm’s performance and economic prosperity. They clearly distinguished the logic in relation to other logics (i.e., of intimacy and empathy deriving from the family system).

In the following paragraph, we present the communication patterns identified with the political system’s logic and the aggregated dimensions: (1) Principle of power dynamics and (2) Diplomacy-oriented communication.

During the interviews, the system’s logic of politics became relevant for interacting in family businesses and business families. As a second-order theme, we identified control mechanisms among the family members. Besides the tendency of patriarchal leadership styles among the interviewed family businesses, the component of different stakeholders and other central parties were involved. In many interviews, the siblings served as a controlling function not only towards the predecessor’s leadership (mostly the father) but also in the context of all siblings involved in the business family. They kept an eye on employees and external consultants, and specifically evaluated one another’s behavior and performance.

“Exactly, the difference is that my father still decides a lot on his own, whereas I think we should decide together because we also have siblings, of course. I don’t know whether that’s necessarily just because we want to share the responsibility a bit, or whether we also want to listen to the expert knowledge or the opinion of the siblings or the advisors or others.” (T3)

Additionally, the “battle for power” as another second-order theme defined decision-making in the family business and business family and thus led to several conflicts.

“We have a business family that tries to resolve internal family conflicts in order to pursue the greater common goal. In other words, this company, the business family, can have a positive effect on the emotional family.” (T2)

Despite the emotionality and the tendency to argue loudly, there have been some interviewees who have defined themselves as the “louder, emotional ones” and some who have categorized themselves as the “more rational” family members. Especially in comparison to siblings, the description of “being the louder or quieter one” played a big role. We identified formal and informal ways of superiority and subordination as a second-order theme. As stated below, not only are conversations in the family considered rather informal, but the interviewee also differentiates between different dynamics and conflict behaviors:

“Accordingly, the proportion of informal, informal exchanges in the conversations. In other words, my little brother is quite loud. And the loudest one often wins. If he wants to bring things to me and to others, then he brings them in first because he’s louder.” (T3)

Here, the louder one has been perceived as the quicker one that might have the stronger argument. There are different synergy effects that positively or negatively affect dynamics with the members involved.

Moreover, interviewees not only acknowledged their power and their agency within dynamics but also talked about societal challenges and the ecological crisis.

“There are a lot of synergy effects sometimes. It is a family business. (…) By politics, I simply mean the fact that everyone, in every organization, in every relationship, there are always people, dependencies, and relationships. So, there are always some kinds of networks that form politics. And by politics, I simply mean the playing out of one’s relationships. One person likes the other better and the other less. And then you somehow try to make the decision in such a way that he prefers to make positive choices by making fewer decisions. And I simply believe that this plays a role in many things.” (T7)

During the interviews, we could also identify aspects specifically oriented toward specific requirements to govern different interests. Additionally, we identified purpose and meaning structures as a second-order theme. The successors reflected on their different roles, their power, and responsibility within the family business.

All participants were strongly engaged with idealistic structures to lead the business and its employees. Most of the interviewees often have contact with the employees of the firm. Despite not working with the employees directly, all interviewees felt a responsibility towards them, which reflected their leadership style. These aspects could be identified as leadership (second-order theme).

“Personnel responsibility, many who are dependent on a paycheck and many people who have been with the company for a long time and have a familiar relationship with the company.” (T2)

Our findings show several opportunities and challenges in the communication and behavior of business families that can be traced back to different social systems logics. Prior studies have shown that double binds characterize communication in business families and family businesses and have been referred to as different communication manners (Litz, 2012). Business families switch between the logics of corporate and family communication. While researchers and practitioners have explored the paradoxical nature of double bind communication in business families and family businesses, we focused on the examination of the nuances of contradictory communication. The starting point of our research was our three research questions. By responding to the research gaps, we can provide numerous theoretical and practical implications that have emerged from our study. While prior research often focused on conceptual contributions about systems logics in communication surrounding business families and family businesses, we have aimed to contribute to the empirical exploration of paradoxical communication.

Firstly, we specifically analyzed, what different systems–beyond the family and the business systems–occur within the communication that often leads to paradoxes and conflicts. Secondly, by differentiating the specific communicative nuances of our study’s participants, we detected how communication in business families can be differentiated on a deeper, fine-grained level. To discover these nuances, we asked our interviewees not only about the characteristics of these different systems logics but also about how they identify the different communication while switching between various communication codes. Finally, our data revealed different sense-making, expectation structures, and guiding distinctions among the partially divergent systems, which can be integrated into a model (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Overview of the findings with the respective systems.

Mainly, in the narration of contradictory situations, the interviewees talked about the different systems logics and expectation structures, unraveling their respective communication codes and specific systemic media (i.e., love, alternatives, norms, money, and power).

First and foremost, our study shows that many systems are involved in the family business realm. Contrary to the assumption of only business and family systems, the findings highlighted the occurrence of multiple systems. Even though the family and the organization can be viewed as the major systems, the interviewees referred especially to the legal, economic, and political systems. The empirical analysis has shown that it is the structural coupling of multiple systems that comes into play in family businesses and their families. Our findings indicate that paradoxes and contradictions derive from the two major systems of family and business and the above-listed systems. As the interviewees demonstrated their operations amidst a complex environment of different systems logics, it became clear that the perspective of two systems or the three-circle model (Kleve et al, 2023; Tagiuri and Davis, 1992; Tagiuri and Davis, 1996) needs to be extended to multiple systems. Based on our data, we were able to determine the significance of other additional systems, as family businesses and their members need to (re-)act in an increasingly complex environment. Future research may take further systems into account (see Fig. 8).

The business family members deal with the systems by differentiating contexts, logics, and role expectations to reduce complexity and maintain communication among all actors involved. Business families that view succession as a co-evolutionary exchange exhibit connectivity within their communication through strong bonds, providing care, trust, and intimacy (Leiß and Zehrer, 2018). The safety of the relationship stems from the family system, which encompasses the whole person and is based on unconditionality. Time after time, the successors (even when they are still far away from taking over the company) serve as internal advisors. It is clear to see that the more the roles shift from advising to executing and taking on more responsibility in the family business, the more the relationship between the predecessor and the successor becomes confrontational, and this can be identified in their communication (i.e., dynamics of power).

Building on the nature of the family system’s extreme emotions, the interviewees emphasized the advantage of plain sincerity for directly communicating problems and the feeling of being able to say “everything” that would serve the goals of the business system. However, the interviewees also identified that this form of uninhibited communication can be a disadvantage in that hurtful things can be said as family members feel less necessity to be polite with each other (Brundin and Sharma, 2011). Thus, this uninhibited communication carries the dual effects of being both useful and useless as is the greatest challenge to remaining constructive and rational. Our data illuminates the significance of integrating differentiation and boundaries into communication and behavior (Leiß and Zehrer, 2018). There are different approaches to differentiating communication. To distinguish between the logics, the interviewees refer to the respective role expectations they are assigned to. Our patterns of findings also imply that the role of settings, (time) frames, and context may help to sort out the communication code accordingly (Bateson, 1972; Luhmann, 2012). We discovered that business families constantly deal with different systems logics and unwittingly differentiate between the respective communication codes. Especially in the transition phase of succession, swapping the roles of “counseling” to “performing” reveals a new form of power dynamics and stimulates a change in the system(s). This aspect also implies the significance of structurally coupled systems in guaranteeing smooth operations in family businesses.

The interviewed successors differentiated communication through different systems’ communication codes derived from the family, organization, law, economy, and politics systems. Drawing on our findings, Table 4 below synthesizes communication and decodes the specific communication patterns emerging from our interpretive data analysis.

| System | Family | Organization | Legal | Economic | Political |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | Love | Alternatives | Norm | Money | Power |

| Principle | Emotional, physical, and kinship bonds | Merit | Legal obligations | Economic rationality | Power dynamics |

| Communication | Intimacy-oriented | Decision-oriented | Rule-oriented | Profit-oriented | Diplomacy- oriented |

| Mechanisms of inclusion | Total inclusion of the whole person | Partial inclusion | Performance versus audience roles (lay roles) | Performance versus audience roles (lay roles) | Performance versus audience roles (lay roles) |

Communication follows the respective principles that serve as guidance and offer expectation structures to align with decision-making. It is symbolically generalized by its medium, such as alternatives in the organization system. Setting boundaries as well as differentiating roles, expectations, and contexts helps business family members distinguish between the systems (e.g., interviewees talked about family (private) events where they specifically avoided conversations about the family business and vice versa, complementary to the “expectation of the expectation” (Luhmann, 2012).

We can confirm the findings of prior studies about complex systems communication (i.e., (Frank et al, 2017; Von Schlippe and Frank, 2013), and (Kleve et al, 2020b)). However, we extend prior research on communication in business families and family businesses by revealing the management of several additional systems logics in addition to only family and business systems. Accordingly, we propose a differentiated perspective on systems (e.g., exploration of function systems) that helps to understand contradictions and behaviors often leading to paradoxes.

Our contributions add to the growing body of literature on the complex relationships and ambiguous communication in business families that often lead to paradoxes and conflicting decision-making. Communication seems to “happen” automatically. However, there is no guarantee that what is observed is correct and socially accepted. This leads to the observed system remaining opaque to the observer, like a black box. Nevertheless, the effort to comprehend is not futile, as it helps compensate for this lack of transparency. This is where communication plays a crucial role. Communication helps simplify complexity and establish meaning and connectivity in interactions (Luhmann, 1998). In addition, symbolically generalized communication helps us quickly understand meaning structures. In social interaction, we do not have to explain every piece of information again; we intuitively know through the expectation of the specific system’s logic. Therefore, a family matter can be quickly understood through the family’s expectation structure, which involves intimacy, extreme emotions, and a focus on unconditional support. In business families and family businesses, research has shown that different systems often clash. Our study examined and defined the distinct expectation structures in the respective systems of family, organization, law, economy, and politics. We specifically highlight the different symbolically generalized communication and deepen the understanding of this theoretical concept. As stated in the interview, emotions and relationship dynamics in organizations should not be underestimated. Companies and family businesses are not only managed according to economic goals but also consist of strong emotions and relationships between employees.

By identifying the different systems’ communication patterns, our study shed light on the distinction between these systems. Our study offers several practical recommendations for guiding different systems logics within communication. In a complex environment of family businesses, business families aim to reduce complexity by following distinct communication patterns. Therefore, we encourage business families to participate in reflection processes to understand and unravel these divergent logics that often lead to contradictions and highly emotional conflicts. Complementary to the systemic tools of the “expectation carousel” or the “tetralemma”, our study’s insights grasp the complexity by distinct clarification of double bind communication (Arnold et al, 2023; Kleve et al, 2020a; Roth et al, 2023; Von Schlippe, 2022). Our framework is, therefore, valuable for practitioners in the field who help business families set up a governance structure for their families through coaching. Aligning different systems logics for managing paradoxical situations may help with decision-making and drive forward organizational procedures and management operations (Berent-Braun and Uhlaner, 2012). Understanding the different systems of family, organization, law, business, and politics contributes to managing different interests, values, and expectations emerging from various stakeholders in the family business. Moreover, it helps to grasp identity creation and the succession process in business families, whereby traditional perspectives and practices of patriarchal leadership styles by the predecessor often lead to highly emotional conflicts (Brundin and Sharma, 2011). Our framework of decision premises in organizations encourages business families to structure and formalize procedures and determine specific role expectations for all members involved. Business families benefit from distinctively differentiating these systems’ logics for their decision-making ability and sorting out highly complex conflicts through different meaning structures.

We acknowledge that this research has been subject to several limitations, which create opportunities for future research directions. For instance, our data approach may be limited to some extent to external validity (Flick, 2014). While we used an inductive qualitative approach, our findings may need to be more statistically generalizable. Therefore, we encourage scholars to employ a mixed methods approach to validate our framework with quantitative methods (Yin, 2015).

We believe that our sample is rather homogenous, as we only included successors and highly potential successors from business families. Thus, our findings could mirror a picture, in which all participants might cope in a more positive way with their family and the business. As a result, the participants could be rather in consensus than in friction. We, therefore, engage researchers to further explore a broader data set of business family members who have shown more controversies, frictions, and tensions within the family structures and potentially not follow as successors.

Our data set only focused on German business families, so the cultural bias must be considered. Due to the cultural context, business families in other countries might have different socialization and decision-making structures. Consequently, this may lead to different research findings. In addition, future scholars can compare our research findings with these cultural contexts and consider other regions or different global family businesses and business families (Aldrich et al, 2021).

Most interviewees not only experienced the contradictory logics of the traditional identity paradox of family vs. business but were also faced with growing expectations of moral and ecological interests. Whereas dealing with the two/three systems of family, business, and law (ownership) has been tackled for several decades by building governance structures, guiding decisions in the family and business, political, and ecological considerations have become increasingly important (Berent-Braun and Uhlaner, 2012; Danes and Brewton, 2011; Kleve et al, 2023). We only analyzed spoken communication but are conscious of communicative actions via body language (gestures, facial expressions), sign language, and the combination of different international languages–how do different “mother tongues” maintain the connectivity of communication and understand different communication codes when systems meaning structures are not the same?

Other research questions could explore the socialization process: How and when do children learn in business families to differentiate between the systemic communication patterns (Frank et al, 2023; Stamm, 2016)? How can externals (e.g., spouses, employees of the family business, members of the board) who are confronted with different systems, or in the case of the spouse who “enters” the family system, learn to differentiate between these systems’ codes? How do they deal with this double/triple/multiple bind communication?

Additionally, prior studies were restricted to the exploration of only three prevalent systems (family, business, and ownership). As our findings have illustrated, we must extend the systems perspective to multiple (function) systems. Future research avenues with a broader scope could add valuable insights to the increasingly growing complexity that family businesses have been facing of late. Growing business families require more coordination and governance mechanisms, especially concerning their diversity, region, and size. A key question for future research is how business families can align different systems’ logics. Against the backdrop that society is becoming more complex globally and locally, the capacity to react to environmental, ecological, and moral issues for family businesses and business families is crucial (Danes and Brewton, 2011). In this sense, we also highlight the capability of paradoxical mindsets to react towards paradoxes in a flexible, creative manner (Miron-Spektor et al, 2018; Smith and Lewis, 2011).

The communication of business families can be very challenging often due to several logics deriving from different systems. Our article offers a qualitative study based on Luhmannian systems theory (2012; 2018) that sheds light on the complex, paradoxical communication in business families. By distinctively detecting the communication and drawing on the systems’ communication codes and media, we have been able to present a framework that illustrates the profound distinctions between these systems. Our findings highlight the central role of the logic of the specific system that guides communication structures and meaning. We identified five systems that contribute to the complex interactions in the communicative acts of business families. We extended the three-circle model (Tagiuri and Davis, 1992) and the prevalent double bind communication (Litz, 2012). In summary, our framework helps to understand communication more profoundly and unravel contradictory decision-making that often leads to communicative paradoxes in business families and family businesses.

Information about the datasets used and/or analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

TA, SR, and HK designed the research study. TA performed the research. SR and HK provided help and advice in methodology, data curation, formal analysis, and conceptualization. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Given the role as Guest Editor, SR had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and had no access to information regarding its peer-review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to SJ.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.