1 CERIIM, Excelia Business School La Rochelle, 17000 La Rochelle, France

2 Next Society Institute, Kazimieras Simonavičius University, 02189 Vilniaus, Lithuania

3 Educational Resource Centre, UCL University College, 5220 Odense, Denmark

4 Department of Social Sciences and Business, Roskilde University, 4000 Roskilde, Denmark

5 Brazilian School of Public and Business Administration, Fundação Getulio Vargas, 22231 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Abstract

This article examines the role of guiding distinctions in management and organisation research. Drawing on social systems theory in the tradition of Niklas Luhmann, it highlights how distinctions such as shareholder/stakeholder, purpose/profit, and economy/society/environment not only shape theoretical discourse but also act as pivotal frameworks for addressing empirical challenges. The analysis distinguishes between true and false distinctions and proposes a typology that categorises different types of false distinctions. By engaging with the contributions to this special issue, the study explores the impact false distinction might have for theory development in management and organisation research. The article argues for rethinking guiding distinctions as a means of bridging theoretical stasis and empirical dynamism in the digital era, also offering a research agenda that integrates past, present, and emerging distinctions to foster digitally attuned management and organisational theories.

Keywords

- digital transformation

- purpose

- stakeholders

- false distinctions

- management and organisation theory

Also known as “primary distinctions” (Luhmann, 1998), the concept of “guiding distinctions” (Andersen, 2003; Jönhill, 2012; Knudsen, 2006; Luhmann, 1998; Luhmann and Rasch, 2002; Luhmann, 2013a; Roth, 2019, 2023a) pertains to distinctions that drive public discourses in general and shape theory-building and empirical research in particular. Examples of such distinctions in the field of management and organisation research include, inter alia, economy/society, structure/agency, resource/market, strategy/culture, shareholder/stakeholder, 1st/2nd/3rd/4th industrial revolution, or economy/society/environment.

A focus on these guiding distinctions is not only of general relevance as a mode of reflection on past, present, and future trends in management and organisation research, but also specifically as a means to address the challenges of the ongoing digital transformation of management and organisation research and theory. This article proposes that guiding distinctions serve as a conceptual lens for critically examining the ways in which digital transformation influences not only empirical research practices but also the theoretical foundations and epistemological underpinnings of the field. Such an approach allows for an integrated perspective on how core distinctions shape the interpretation and generation of knowledge in an increasingly digitized scholarly landscape.

Information and communication technology and the increasing availability of digital data are dramatically changing the processes of research and knowledge production in management and organisation research. New technologies enable unprecedented levels of data collection, analysis, and dissemination, fundamentally transforming the methodological toolkit available to scholars (Neisig, 2017, 2024a; Roth et al, 2017). Yet, while the pace, scale, and scope of methodological innovation in management and organisation research are impressive, theory development has not kept pace with these advancements (Roth, 2023a; Roth et al, 2019; Valentinov et al, 2023). This mismatch presents a significant challenge, as digital methods do not only provide ever-larger datasets for the testing of established theories but also demand the exploration of new theoretical frameworks capable of capturing the unique dynamics of the digital era (Kitchin, 2014).

To address this theoretical lag, this introductory article argues for the importance of rethinking guiding distinctions in light of the digital transformation. The translation of analogue distinctions, including gradients and continuums, into digital, binary guiding distinctions holds the potential to uncover novel pathways for theory development. This perspective encourages scholars to critically evaluate and adapt existing theoretical paradigms, ensuring that they remain relevant and responsive to the evolving landscape of digital research. By focusing on the interplay between digital tools, guiding distinctions, and theoretical innovation, this study contributes to a broader understanding of how the digital era reshapes the epistemological and methodological contours of management and organisation research.

In this context, the article aims to achieve three objectives. First, it provides a conceptual framework for understanding guiding distinctions as a critical element in theory-building not least within the digital transformation of management and organisation research. Second, it draws on the six contributions to the present special issue of management revue. Socio-Economic Studies to illustrate the implications of these distinctions for methodological innovation and theory development, also emphasising their role in bridging the gap between empirical advances and theoretical stasis. Finally, it proposes a research agenda for advancing digital theorising by identifying and combining past, present and future guiding distinctions into the study of contemporary challenges in management and organisation. By doing so, this introductory article seeks to inspire a more dynamic and reflexive engagement with the possibilities and limitations of binary and non-binary distinctions for research on management and organisation within the context of a digitally transforming society.

Various guiding distinctions that have shaped discourses in management and organisation research.

One recent example is related to the concept of organisational purpose, which has gained traction in various fields such as economics, management, or strategy (George et al, 2023; Mayer, 2021; Morrison and Mota, 2023; Ocasio et al, 2023). Consequently, purpose is a recurring topic at annual meetings of the Academy of Management (Friedland and Jain, 2022) and international conferences on management and organisation. Most recently, purpose featured prominently in the theme of the European Academy of Management Conference 2025, which is “Managing with purpose”.

Commonly defined in opposition to profit as the pursuit of “a concrete goal of objective (…) that reached beyond profit maximization” (Henderson and Van der Steen, 2015, p. 327), that is, of operations that advance public goods (Henderson, 2024) or address issues of societal relevance (Donaldson and Walsh, 2015). Purpose versus profit clearly acts as a distinction that guides discourses in management and organisation research for example along the question whether profit maximisation must be consider the sole purpose of business (Friedman, 1970; Jensen, 2002) or if further purposes can be added on as additional purposes on top of profit maximation, which however remains a business’ ultimate purpose (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 1994; George et al, 2023; Mayer, 2021). Yet other researchers have made the case for the existence of organisations in which profit and one additional purpose can be of equal importance to so-called “dual purpose” organisations (Arya et al, 2019; Battilana et al, 2019, 2022). Another set of scholars adopt an “open purpose” view, according to which organisations may have varying purposes as they shape and adapt to changing organisational environments (Basu, 2017; Clegg et al, 2021; Henderson, 2024; Joly, 2021; Morrison and Mota, 2023). The latter perspective aligns well with the idea that all organizations are, in principle, multifunctional (Neisig, 2024a; Roth et al, 2017, 2018, 2020) and, therefore, not, by default, tightly coupled to one of the function systems of society such as economy, politics, law, science, or education, though they may well choose to be more or less tightly coupled to one or a set of these function systems.

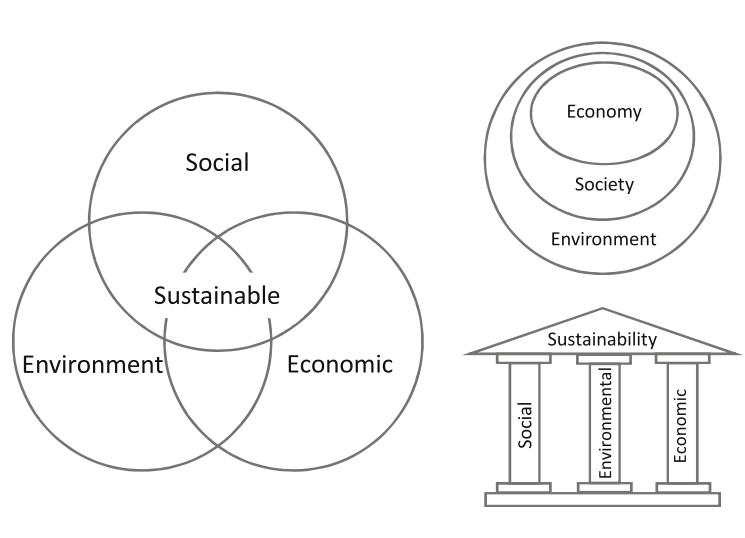

Accordingly, recent years, if not decades, have seen growing expectations towards business organisations to complement their economy-orientation to address an increasing number of predominantly political and natural scientific issues, an attitude prominently represented in the variants of the classical triple-bottom-line model depicted in Fig. 1.

The prominent idea that organisations should pursue “social” goals (Valentinov et al, 2021), as typically defined by political actors, and address “environmental” issues, which are usually identified by natural scientists, in addition to the economic purpose of profit is a case in point that guiding distinctions are not limited to ostensibly binary distinctions such as profit versus purpose, but are also extended to three-pronged distinctions such as economy/society/environment.

Moreover, the concept of purpose not only explains why organizations come into existence and function in specific ways as they aim to achieve growing and increasingly diverse sets of objectives or goals (Morrison and Mota, 2023; Valentinov, 2024), but also how organisations establish a distinct identity for themselves and others, whether it be for internal stakeholders like employees, or external audiences like customers (Battilana et al, 2019; Chua et al, 2024; Neisig, 2024b), as they adapt to dynamic social and natural environments (Valentinov and Iliopoulos, 2024; Valentinov, 2022).

These short elaborations on popular guiding distinctions of management and organisation research aim to demonstrate not only the general relevance of guiding distinctions to our fields but also provide examples of how these distinctions are interlinked, thus illustrating that discourses in these as much as in other fields of research are formed by and as architectures of guiding distinctions (Roth, 2023a; Roth et al, 2025a; Roth et al, 2025b).

The theme of the Luhmann Conference 2024 at the Inter-University Centre Dubrovnik was “Guiding distinctions. Observed with social systems theory”. The present selection of contributions to the special issue of management revue. Socio-Economic Studies, dedicated to “The guiding distinctions of management and organisation research”, complements the special issue of Current Sociology on “Guiding distinctions of social theory. Analogue guidelines or digital transformers” (Roth et al, 2025b). Whereas the latter special issue is devoted to the role guiding distinctions play in social theorising more broadly, contributions to the present special zoom in on guiding distinctions such as family versus business, inclusion versus exclusion, organisation versus interaction, black versus white, or leadership versus followership, specifically as they pertain to organisational and management challenges.

The article Double binds in dialogue: Unraveling paradoxical communication in business families and family businesses by Arnold et al (2025) examine the dynamics of paradoxical communication within business families. The authors use social systems theory in the tradition of Luhmann (2012, 2013b) to explore the interplay of family and business logics. Through qualitative interviews with next-generation business family members, the authors identify double-bind situations emerging from conflicting emotional and rational expectations inherent in family system and business system communication. The guiding distinction between “intimacy versus rationality” underpins the analysis, demonstrating how tensions between the code of love and the logics of economic, legal, or political decision-making manifest in both family and business communication. The study’s major contribution lies in applying systems theory to empirical data, offering practical insights into managing paradoxical communication by recognizing and addressing tensions between different systemic codes. The originality of this paper is its operationalization of Luhmannian theory to untangle latent communication patterns, providing actionable strategies for practitioners to alleviate tensions in family businesses and business families alike.

In Regulation as Distinction – A Generalized Approach to Leadership Based on Social Systems Theory, Fritzsche (2025) draws on Luhmannian social systems theory to reposition the traditional distinction between leadership and followership. Fritzsche tacitly follows George Spencer Brown’s distinction between distinction and indication as he defines regulation as a guiding distinction-in-operation that distinguishes between insides and outsides and, thus, contributes to the self-maintenance of autopoietic systems, including organisations. In contrast to traditional hierarchical views, leadership is conceptualized as a regulatory mechanism emergent from autopoietic dynamics. Major contributions of Fritzche’s article include a theoretical expansion of leadership as a universal, context-agnostic phenomenon emerging across a diverse nexus of organizational settings. The originality of his study lies in framing leadership styles as manifestations of regulatory distinctions, providing a broader, systemic understanding of leadership in the age of digital transformation.

Focusing on generative AI, Kim (2025)’s article Self-Programming Dynamics: Exploring Generative AI-User Interactions through Luhmann’s Systems Theory suggests that users and AI systems co-evolve through self-programming operations stimulated by the mutual irritation. Utilizing Niklas Luhmann’s concepts of self-programming and structural coupling, the research highlights the recursive feedback loop wherein AI adapts to user inputs while users refine their prompts and engagement strategies. The guiding distinction of specificity versus generality frames his discussion of the tension in AI-mediated interactions, in the context of which he also challenges a number of prominent guiding distinctions prevailing the contemporary AI discourses such as developer versus end-user or user and generative AI. This paper’s contribution to the special issue lies in extending systems theory to digital-human interactions, thus also illustrating the co-creation of meaning in technological environments. The originality of Kim’s contribution is rooted in his application of Niklas Luhmann’s theory to AI, thereby revealing paradoxes that shape adaptive and generative processes in digital contexts.

Neisig (2025)’s article From Neglect to Resonance? - The Twin Transition and Luhmann’s Legacy builds on Luhmann (1997)’s idea of the function systems’ lacking sensitivity to ecological issues as well as on Valentinov (2013, 2014, 2017)’s complexity-sustainability trade off to analyse the European Union’s “Twin Transition”—a policy programme focused on the convergence of the digital and the green transformations. Neisig argues that while new semantics and technologies enhance systemic responsiveness, particularly small and medium enterprises (SMEs) face systematic barriers to the implementation of more diverse semantic reservoirs and the resulting multidimensional worldview due to resource constraints. The guiding distinction between inclusion and exclusion reveals how functional systems selectively resonate with ecological concerns. The paper contributes by integrating Valentinov’s reading of Niklas Luhmann’s work on ecological communication with contemporary sustainability discourses, also proposing engaged scholarship and digital platforms as adequate intervention strategies. The originality of Neisig’s article lies in connecting ideas of regional polycentric networks to the concept of systemic resonance, thus offering a practical model for fostering SME participation in sustainable transitions.

In his article What is in organisation? Contents of a self-contained container, Roth (2025) challenges the perceived dichotomy between organizations as containers of communication and as communicative constructs. Drawing on Niklas Luhmann’s concept of autopoiesis and George Spencer Brown’s Laws of Form, Roth introduces “continence” as a dynamic and multidimensional concept to propose a framework where organizations can be observed to both constitute of and contain communication. The guiding distinctions between inside and outside and decision and non-decision are reframed to illustrate how organizations can be communicative systems that contain their communicative environment without being constituted by it. The paper’s contribution lies in resolving and theoretical impasse in organizational studies, providing a nuanced perspective that synthesizes containment with communicative processes. The originality of the study is its innovative re-conceptualization of the container metaphor, thus advancing a multiversal view of organizational boundaries.

In Reframing race beyond black and white: the case of Pardos in Brazil and the global challenge of rigid racial classifications - a systems approach, Sales and Carvalho (2025) examine Brazil’s racial dynamics through the lens of Niklas Luhmann’s social systems theory, thus extending the narrow black/white distinction that marginalises Pardos (that is, mixed-race individuals). By analysing affirmative action policies and drawing parallels with multiracial experiences globally, the study reveals how rigid classifications perpetuate systemic exclusions. The guiding distinctions of black versus white and inclusion and exclusion are combined to revert the invisibilisation of multiracial identities in organisational contexts. Major contributions of Sales and Carvalho (2025)’s article lie in a decolonial reframing of racial classifications, advocating for multidimensional frameworks that honour Brazil’s racial continuum as well as in its application of systems theory to racial discourse, whereby the authors also highlight how flexible distinctions can foster inclusivity and equality in diverse societies.

In reviewing the six contributions to this special issue of management revue. Socio-Economic Studies, it is evident that they are united not only by a common paradigmatic approach and a dedicated focus on guiding distinctions as they relate to management and organisation, but by a shared interest in explorations of paradoxes or inter-systemic tensions. In fact, all articles address at least one paradox or tension arising from systemic interactions. These include emotional versus rational communication (Arnold et al, 2025), regulatory dynamics resulting from leadership-followership tensions (Fritzsche, 2025), AI’s yet-to-be-defined balance between specificity and generality (Kim, 2025), perceived trade-offs in sustainability transitions (Neisig, 2025), communicative versus container views of organizations (Roth, 2024), and the organised marginalisation of multiracial identities based on binary frameworks that may be overcome binary extensions of those frameworks (Sales and Carvalho, 2025). Another common theme pursued by at least half of the present contributions are matters of systemic responsiveness to environmental challenges pertaining not only to environments in terms of various aspects of nature (as explored by Neisig, 2025), but also with regard to a social systems’ social environments (as studied by Arnold et al, 2025 or Sales and Carvalho, 2025, see also Roth et al, 2020; Roth and Valentinov, 2020). In this regard, the contributions to this special issue also resonate with or revisit topics discussed at the Luhmann Conference 2023, whose theme was “Environments. Observed with social systems theory”, and which resulted in an eponymous special issue of Systems Research and Behavioral Science (Roth et al, 2025a).

In this sense, the contributions to this special issue highlight the importance and utility guiding distinctions and systems theory for addressing complex organizational and management issues particularly with regard to an organisation’s social and natural environments.

In the related special issue of Current Sociology on “Guiding distinctions of social theory. Analogue guidelines or digital transformers?” (Roth et al, 2025b), Roth et al (2025c) make a case not only for the general importance of guiding distinctions for theorising across our fields of research, but also for the need to distinguish between true and false distinctions. Based on Roth (2024), the argument is as follows: If we cannot observe without drawing a distinction (Spencer Brown, 1979, p. 1, Luhmann, 1995, p. 172), and if the basic operation of scientific observation is the distinction between true and false observations (Luhmann and Behnke, 1994; Roth, 2024), then it follows that scientific observation involves the distinction between true and false distinctions.

To distinguish between true and false distinctions, Roth et al (2025c) draw on George Spencer Brown (1979, p. 1) definition according to which “distinction is perfect continence”, which implies “That a true distinction divides the entire frame of reference into two mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive parts. The paradox of scientific observation then lies in the fact that, by definition, all distinctions are true because they perfectly divide their reference frame—otherwise, they wouldn’t be considered distinctions at all. However, in scientific observation, we are required to differentiate between true and false distinctions. Therefore, some distinctions that are technically true must be regarded as false.” (Roth et al, 2025c)

According to Roth (2024, p. 263) the solution to this paradox is then “To argue that distinctions are, by default, neither true nor false and can, therefore, be both true and false at the same time. Consider the distinction between 0 and 1, for example. If we consider 0 and 1 to be two elements of the number range, then the distinction between these two numbers is false in that the two distinguished elements are obviously not jointly exhaustive, and therefore do not match the above requirement of perfect continence. Yet, if these two numbers represent two values of a binary code system, then their distinction is clearly a true one as it splits the entire frame of reference into two mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive sides. The crux of the matter is hence not whether or what distinctions are essentially true or false, but rather what follows if we take a distinction for a true or false one.”

If as true we may define those distinctions that are both mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive, then it follows that we may distinguish three types of false distinctions as presented in Table 1.

| Mutually exclusive | Jointly Exhaustive | Examples | |

| True distinctions | 1 | 1 | system/environment, life/death, |

| False distinctions (Type 1) | 1 | 0 | economy/religion, post-/modernity |

| False distinctions (Type 2) | 0 | 1 | economy/society, |

| theory/practice | |||

| False distinctions (Type 3) | 0 | 0 | property/access |

| male/female |

In line with Table 1, false distinctions of type 1 are those distinctions that split their frame of reference into two mutually exclusive, yet not jointly exhaustive categories. The example of modernity versus post-modernity is a case in point if we also take the existence of a pre-modern period into account. By contrast, false distinctions of type 2 distinguish jointly exhaustive, yet not mutually exclusive side. For example, this is the case if we distinguish between theory and practice while also insisting that theory is a form of practice itself. Finally, type 3 false distinctions draw dividing lines between concepts that are neither mutually exclusive nor jointly exhaustive. One prominent example would be the male/female distinction if we accept that there may be persons or animals who or that are both male and female or neither male nor female.

When applying the distinction between true and false distinctions to prominent guiding distinctions of management and organisation theory, we may find that a considerable number of these distinctions qualify as one of the above three types of false distinctions.

The distinction between shareholders and stakeholders clearly represents a false distinction of type 2 if we accept the common understanding that shareholders are stakeholders, too. Moreover, various scholars highlight the significance of involving various (non-shareholder) stakeholders in a broad range of decision-making processes. Yet, while this approach involves recruiting participants from diverse sectors and backgrounds through open calls for participation (Gegenhuber and Mair, 2024) to ensure that a broad range of perspectives are considered, established stakeholder management tools remain biased to stakeholders from the political (governmental, non-governmental, civil society, etc.) and economic domains (customers, investors, suppliers, etc.) (Roth, 2023a, p. 457). Consequently, arguments of “Both the advocates of stakeholder management and the defenders against stakeholder intrusions are based on age-old social theories or discursive distinctions. One of the most influential of these distinctions is probably the ‘Economy and Society’ perspective developed in Max Weber’s (…) eponymous work, which has for over hundred years now a) categorically separated economy and society and b) over-identified society with nation states and thus with segments of a global political system” (Roth, 2023b).

In other words, the type 2 false distinction between shareholders and stakeholder is regularly discussed against the background of another false distinction, either of type 1 or type 2. The former is the case if we argue that the distinction between economy and politics does not encompass the entire frame of reference, which also includes other function systems such as science, religion, or education. The latter applies if we consider the economy a subsystem rather than an extra-social opponent of society.

In a similar vein, the purpose/profit distinction also re-emerges as a false distinction, not only because profit may be considered a purpose as well (Van der Linden and Freeman, 2017), but also because purpose is far too often associated with “social” goals that actually constitute political one. The ubiquitous United Nations Sustainable Development Goals are a case in point.

One of the most ironic discoveries of a distinctionist approach to management and organisation research is that it is particularly false distinctions that act as guiding distinctions. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that false distinctions play a key role “in the design, maintenance and perpetuation of discourses, strategies and paradoxes nurtured, dreaded or simply co-performed in management and organization theory and practice” (Roth, 2023a, p. 452). This is especially true whenever false distinctions are unconsciously or strategically used to design dilemmas or tensions. In this sense, we may even speak of entire fields of research whose existence is predicated on false distinctions. One such example is the family/business distinction that features prominently in Arnold et al (2025)’s contribution to this special issue and acts as the guiding distinction of the field of family business research. Another example is the field of leadership research explored in Fritzsche (2025)’s contribution, if we assume that the tacit guiding distinction of this field is indeed leadership versus followership (Clausen, 2024) and agree with Sales et al (2024) that persons can be both leaders and followers, or neither, respectively.

The case is even clearer for environmental management, ecological economics, sustainability research, and other fields where the economy/society/environment distinction plays a critical role. In fact, this distinction is a prime example of a false distinction precisely because it is demonstrably more than one.

Consequently, the way to manage false distinctions is to realise that every false distinction is a conglomerate of more than one distinction and can therefore be translated into two or more true ones. While the procedural dimension of such translations has been detailed elsewhere (Roth, 2023a, 2019), the epistemological dimension of these procedures pertains to the circumstance that they amount to the translations of literally analogue, juxtaposed distinctions into binary ones. In this sense, the translation of false distinction into true ones—rather than the use of computers for the development of models based on traditional, analogue distinction—represents the core technique of a digital transformation of research in management and organisation.

Against this background, the systematic identification of guiding distinction and their guided qualification as true or false constitutes a critical update for management and organisation theories attuned to a digitally transforming society.

Future avenues of such digitally transformed and transforming research on management and organisation may therefore include questions of the following non-exclusive type:

What have been the most influential guiding distinctions in the

history of management and organisation research? What are the particularly

influential guiding distinctions today? What emerging or yet-unknown guiding

distinctions might shape the future of theory and research in these fields? Are extant guiding distinctions in management and organisation

theories suitable for digital theorising and research? If not, how can prominent

analogue distinctions be translated into digital ones? Are there analogue concepts of management and organisation that

cannot or should not be translated into digital ones? Is it necessary or important to defend and protect the analogue

“lifeworld” (of theorising) from its translation into digital systems

(theories)? What prospects exist—or are conceivable—for trans-paradigmatic

digital theory platforms or theoretical operation systems capable of processing

all pertinent guiding distinctions?

Ironically, the development of sophisticated answers to these and similar questions, and most notably the identification of guiding distinctions, will remain a privilege of “wetware” computers for quite some time. In fact, computer and Internet technology, including our digital Geminis such as ChatGPT, CoPilot, and others still appear to be unable to assist us in the automated identification of distinctions in large text corpora.

It is not without irony that the identification of distinctions poses such a challenge to the distinction-based machines we refer to as computers.

Not applicable.

The first draft of the manuscript was written by SR. LC, MN, and AS contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Given the role as Guest Editor, SR, LC, MN, and AS had no involvement in decision of this article. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to SJ.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.