1 Departamento de Psicología Social y de las Organizaciones, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), 28040 Madrid, Spain

2 Departamento de Microbiología, Universidad de Málaga, 29071 Málaga, Spain

Abstract

As organisms age, the gut microbiome experiences pronounced shifts in both its composition and function, resulting in a state of dysbiosis. In order to mitigate the detrimental consequences of aging and promote healthier aging trajectories, it has been suggested that the modulation of the gut microbiome through the implementation of fecal microbiota transplantation may constitute a promising strategy to enhance healthspan and delay age-related decline. This narrative review examines the role of the gut microbiome in aging, with a specific focus on the therapeutic potential of fecal microbiota transplantation in promoting healthy aging. In older adults, the presence of gut microbiome dysbiosis has been linked to a heightened susceptibility to various age-related disorders, as well as to oxidative stress, diminished bioavailability of essential nutrients, persistent systemic inflammation, and insulin resistance. Preclinical studies have evidenced that the administration of fecal microbiota transplantation from young donors to aged recipients can effectively restore the donor’s gut microbiome, thereby enhancing the overall health of the host. In clinical studies, the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in restoring a healthy gut microbiome has been demonstrated in the treatment of numerous conditions, including not only chronic gastrointestinal disorders but also a range of extra-intestinal disorders and symptoms. However, several factors limit its widespread clinical use, including mechanisms of action, treatment costs, application timing and route, efficacy, tolerability, and safety. Therefore, fecal microbiota transplantation shows promise as a microbial approach for addressing aging-related effects, but its full viability and effectiveness are still under investigation, requiring further development and optimization to reach a more refined stage of therapeutic application.

Keywords

- fecal microbiota transplantation

- healthy aging

- gut microbiome

- older adults

- personalized medicine

Aging is characterized by a progressive decline in functional capacity, driven by a broad spectrum of cellular, molecular, and structural alterations. These cumulative changes compromise the ability of the organism to maintain homeostasis, heighten vulnerability to various pathologies, and impair numerous physiological processes. Notable consequences include diminished organ functionality, reduced resilience to stress, and the gradual destabilization of the internal environment [1]. In addition, aging represents the predominant risk factor for human mortality, largely due to its association with functional deterioration, increased frailty, and a higher propensity for developing chronic illnesses [2]. In response to these challenges, intervention strategies for healthy aging have emerged to preserve functional capacity throughout life by targeting physical and cognitive domains alongside environmental and social determinants of well-being [3]. Within this context, microbiota-based therapeutic approaches targeting older adults with complex clinical conditions, such as neurodegenerative diseases, have gained attention as innovative tools to address age-related decline [4].

As organisms age, the gut microbiome (GM) experiences pronounced shifts in both its composition and function, resulting in a state of dysbiosis. This process is influenced by intrinsic factors, including genome instability, mitochondrial dysfunction, and epigenetic alterations, as well as by external factors such as environmental exposures, dietary influences, and diseases [1, 2]. The concept of the GM as a “second genome” underscores its integral role in human health, given its involvement in diverse metabolic, immunological, and physiological processes. These include digestion of foods, synthesis of vitamins and hormones, modulation of immune responses, prevention of external microbial pathogens from invading and colonizing the host, and preservation of intestinal barrier integrity [5]. Building on the aforementioned, growing evidence demonstrates that dysbiosis of the GM exerts a clinical impact on the pathogenesis of several age-related diseases, including neurodegenerative conditions [2]. In light of this, personalized medicine based on remodeling the GM appears to be a novel and impactful avenue for addressing age-related chronic disorders.

In order to mitigate the detrimental consequences of aging and promote healthier aging trajectories, several authors have suggested that the modulation of the GM through the implementation of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) may constitute a promising strategy to enhance healthspan and delay age-related decline [1, 5, 6, 7]. FMT involves the transfer of fecal microbial communities from healthy individuals to recipients with a disrupted GM, aiming to restore microbial diversity and balance within the GM [7]. FMT has been utilized as a therapeutic tool for (i) a variety of chronic and recurrent microbial infections, including antibiotic-refractory Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI), Helicobacter pylori infection, multidrug-resistant microorganism infections, and fungal and viral infections; (ii) various gastrointestinal disorders, including Crohn’s disease, constipation, ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, irritable bowel syndrome, colon cancer, and chronic pouchitis; (iii) several metabolic and autoimmune diseases, such as refractory melanoma, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes type 2, fibromyalgia, and cardiovascular inflammation; and (iv) neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and multiple sclerosis (MS) [4, 8]. Nevertheless, FMT currently poses notable challenges, particularly due to the complexity of GM transfer in comparison to oral microbial communities, as well as to the uneven spatial distribution of microorganisms within the gastrointestinal tract of the host [5, 9]. To address these challenges, repeated administrations of microbial formulations are frequently required during prolonged periods to facilitate the colonization of donor microbiota within the recipient’s gut ecosystem using a washed microbiota transplantation through transendoscopic enteral tubing [10]. Given the growing interest in the gut-brain-aging axis and the emerging use of FMT as a feasible intervention, this narrative review examines the role of the GM in aging, with a specific focus on the therapeutic potential of FMT in promoting healthy aging.

Aging individuals with good health exhibit a distinct GM composition and diversity compared to young adults, characterized by a decrease in both the Bacillota/Bacteroidota ratio and microbial diversity, alongside an increase in the abundance of pathobionts [2]. The reduction of bacterial diversity is reflected in a lower production of beneficial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and a decrease in the abundance of the following bacterial genera: Bifidobacterium (phylum Actinomycetota), Bacteroides and Prevotella (phylum Bacteroidota), and Clostridium, Coprococcus, Eubacterium, Faecalibacterium, Lactobacillus, and Roseburia (phylum Bacillota). Conversely, with aging, there is an increase in the prevalence of opportunistic pathogenic microorganisms and other commensal bacteria that release pro-inflammatory cytokines. These bacteria include the genera Eggerthella (phylum Actinomycetota), Alistipes, Butyricimonas, Odoribacter, Parabacteroides, and Paraprevotella (phylum Bacteroidota), Anaerotruncus, Butyricicoccus, Butyrivibrio, Coprobacillus, Peptoniphilus, Ruminococcus, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus (phylum Bacillota), Bilophila and Desulfovibrio (phylum Thermodesulfobacteriota), Fusobacterium (phylum Fusobacteriota), Akkermansia (phylum Verrucomicrobiota), and Helicobacter (phylum Pseudomonadota) [2, 11].

Ghosh et al. [11] have proposed that the GM may function as a modulatory target in the aging process, and three major groups of taxa exhibiting consistent patterns of alterations were identified, with either an increase or decrease in abundance in older individuals, as well as changes in abundance associated with unhealthy aging. The first group comprises taxa typically decreased with advancing age, particularly under conditions of unhealthy aging. This group includes Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, Coprococcus, Eubacterium, Bifidobacterium, and Prevotella. The second group consists of pathobionts whose abundance tends to increase with aging and is particularly pronounced in age-related dysbiosis. Genera in this group include Eggerthella, Bilophila, Desulfovibrio, Fusobacterium, Anaerotruncus, Streptococcus, and Escherichia. The third group encompasses genera that increase with age but are depleted in cases of unhealthy aging, such as Akkermansia, Odoribacter, Butyricimonas, Butyrivibrio, Barnesiella, and Oscillospira. Despite these classifications, the composition of the GM in elderly individuals remains a topic of debate. Such discrepancies are often attributed to differences in geography, diet, cultural habits, environmental exposures, and analytical methodologies used across studies [2]. For example, in Western populations characterized by high intake of fats and proteins, the Bacteroides enterotype is most commonly observed. In contrast, the Prevotella enterotype is predominant in populations with fiber-rich diets. The GM of Europeans and North Americans is typically enriched in the phyla Bacillota, Actinomycetota, Verrucomicrobiota, and Bacteroidota. In comparison, African populations exhibit higher microbial diversity, with notable representation of Actinomycetota, Bacteroidota, Bacillota, Pseudomonadota, and Spirochaetota [2]. In East Asian populations, the dominant phyla reported include Bacillota, Bacteroidota, Pseudomonadota, and Actinomycetota, with four enterotypes frequently identified: Prevotella, Bacteroides, Escherichia, and a composite enterotype comprising Ruminococcus, Bifidobacterium, and Blautia [12].

The process of aging is accompanied by a gradual disruption of the physiological

equilibrium between the host and the GM. This disruption involves alterations in

GM abundance, diversity, functional capacity, and host immune response. These

factors are interconnected and collectively contribute to the dysbiosis

associated with aging. However, it remains to be elucidated whether these

microbial shifts are a cause or a consequence of this imbalance. The emergence of

an age-related GM profile is shaped in part by chronic, low-grade systemic

inflammation, known as inflammaging, which arises from the persistent

overstimulation of the innate immune system throughout the lifespan [13]. This

pro-inflammatory environment contributes to the epithelial barrier dysfunction

frequently observed in older individuals, driven by increased antigenic exposure

and heightened immune activation [5]. In turn, this results in epithelial cell

damage and dysregulation of intercellular junctions. Barrier-disrupting

cytokines, including Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-

Immune remodeling associated with immunosenescence has also been interpreted as an adaptive mechanism that may favor successful aging through the regulation of inflammatory responses and the establishment of a functional balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators [14]. According to Santoro et al. [15], the GM may support healthy aging by employing several mechanisms that neutralize inflammaging. Microbial diversity, in particular, is regarded as a pivotal marker of host health, as reductions in GM diversity have been linked to numerous pathological states, such as microbial infections, autoimmune diseases, and metabolic dysregulation [16].

In older adults, the presence of GM dysbiosis has been linked to a heightened susceptibility to various age-related disorders, including atherosclerosis, gastrointestinal pathologies, metabolic syndrome, neurodegenerative conditions, type 2 diabetes, cachexia, and cancer [2, 17]. In addition, age-related shifts in GM composition may also adversely impact musculoskeletal health by contributing to oxidative stress, diminished bioavailability of essential nutrients, persistent systemic inflammation, and insulin resistance [18, 19].

Frailty is a complex geriatric condition characterized by heightened susceptibility to several negative health outcomes, including impaired physical performance, diminished muscle strength, persistent fatigue, and unintended weight loss. This syndrome is associated with a decline in quality of life and autonomy, as well as elevated risks of hospitalization and mortality among older adults [20]. One of the most prominent alterations in the GM of frail individuals is a marked reduction in microbial diversity. This loss is attributed to multiple contributing factors, such as poor dietary intake, reduced mobility, institutionalization, increased antibiotic exposure, changes in medication regimens, compromised intestinal barrier integrity, and dysregulated immune responses [21, 22]. Microbiome analyses have revealed that frailty is characterized by a notable depletion of specific microbial taxa. These include families such as Lachnospiraceae, Barnesiellaceae, Gemellaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, and Christensenellaceae, along with genera including Slackia (phylum Actinomycetota), Paraprevotella and Prevotella (phylum Bacteroidota), Acidaminococcus, Coprococcus, Faecalibacterium, Fusicatenibacter, Gemella, Lachnoclostridium, Lactobacillus, and Roseburia (phylum Bacillota), as well as Azospira and Sutterella (phylum Pseudomonadota) [2, 23]. In contrast, the GM profile of frail elderly individuals shows enrichment in several microbial groups. These include members of the families Enterobacteriaceae, Eubacteriaceae, Bifidobacteriaceae, Atopobiaceae, Mogibacteriaceae, Micrococcaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, Ruminococcaceae, Veillonellaceae, and Coriobacteriaceae. Furthermore, increased abundance has been observed in genera such as Actinomyces, Bifidobacterium, Eggerthella, and Rothia (phylum Actinomycetota), Parabacteroides (phylum Bacteroidota), Acetanaerobacterium, Anaerotruncus, Catenibacterium, Clostridium, Coprobacillus, Dialister, Lachnoanaerobaculum, Megasphaera, Ruminococcus, and Veillonella (phylum Bacillota), Erwinia (phylum Pseudomonadota), and Pyramidobacter (phylum Synergistota) [2, 23].

The imbalance in these bacterial genera has been shown to result in elevated

systemic concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-

It is well known that aging constitutes a significant risk factor for a variety

of neurodegenerative diseases, such as subjective cognitive decline, mild

cognitive impairment, AD, PD, MS, and delirium. A correlation has been

demonstrated between changes in the diversity and richness of GM and the

progression of neurodegenerative conditions, particularly with regard to

diminished cognitive function [26]. The GM plays a regulatory role in

inflammaging, which underlies various age-related adverse states, including

neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration [27]. The GM has been shown to modulate

innate immunity and trigger inflammatory responses, which encompass both gut

inflammation and the increased circulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Gut

bacteria produce significant amounts of byproducts, including lipoproteins and

lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which influence signaling pathways implicated in the

release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [2, 28]. Elevated levels of LPS have been

shown to be associated with increased expression of TLR4 on the surface of M1

macrophages, thereby activating the myeloid differentiation protein-88 signaling

pathway and promoting the nuclear translocation of factor

Evidence supports the association between AD and a state of dysbiosis within the GM [29]. In this regard, three primary mechanisms have been proposed to explain the connection between the GM and the pathogenesis of AD: (i) induction of CNS inflammation and cerebrovascular damage through microbial-derived metabolites and amyloid-like compounds; (ii) disruption of autophagy-dependent pathways responsible for protein clearance, resulting from GM dysregulation; and (iii) modulation of central neurotransmitter levels via vagal afferent signaling influenced by GM activity [31]. A recent comprehensive review has examined GM alterations linked to neurodegenerative diseases [2], reporting a relative decrease in the abundance of the following genera in patients with AD compared to healthy controls: Adlercreutzia (phylum Actinomycetota), Butyricicoccus, Clostridium, Coprococcus, Dialister, Eubacterium, Faecalibacterium, Lachnospira, Romboutsia, Roseburia, and Turicibacter (phylum Bacillota), Gemmiger (phylum Pseudomonadota), and Bilophila (phylum Thermodesulfobacteriota). On the contrary, it has been reported a relative increase in the abundance of the genera Bifidobacterium (phylum Actinomycetota), Alistipes and Bacteroides (phylum Bacteroidota), Anaerostipes, Blautia, Gemella, Phascolarctobacterium, Ruminococcus, and Subdoligranulum (phylum Bacillota), Escherichia/Shigella (phylum Pseudomonadota), and Akkermansia (phylum Verrucomicrobiota) in patients with AD compared to healthy controls.

Despite the evidence from multiple studies indicating that dysbiosis of the GM is a significant factor in the development of PD [32], alterations in the fecal microbiota specifically associated with cognitive impairment in PD remain as a relatively understudied area. A recent review study [2] established that there is an alteration of the GM in individuals with PD, which is marked by a decrease of the genera Brevibacterium (phylum Actinomycetota), Bacteroides and Prevotella (phylum Bacteroidota), Blautia, Butyrivibrio, Clostridium, Coprococcus, Eubacterium, Faecalibacterium, and Roseburia (phylum Bacillota). Conversely, the GM of individuals with PD has been shown to increase in the abundance of several genera, including Bifidobacterium (phylum Actinomycetota), Alistipes, Barnesiella, Butyricimonas and Odoribacter (phylum Bacteroidota), Anaerotruncus, Christensenella, Lactobacillus, and Oscillospira (phylum Bacillota), as well as Akkermansia (phylum Verrucomicrobiota).

As indicated by the existing literature, greater concentrations of circulating LPS and branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) have been identified in the blood of older adults. Elderly individuals also exhibit GM dysbiosis, compromised intestinal mucosal barrier function, and diminished synthesis of SCFAs and secondary bile acids. These factors contribute to the development of insulin resistance and reduced muscle protein synthesis, resulting in heightened muscle protein breakdown [33].

An expanding body of evidence indicates that alterations in the GM composition take place with age, affecting the abundance and diversity of both beneficial and harmful bacterial species. These microbial shifts have been demonstrated to affect the production of a series of microbial metabolites that directly impact several physiological and immune host functions [6]. Since GM dysbiosis has been associated with a range of age-related conditions [2, 34], interventions designed to restore gut microbial homeostasis hold considerable potential in promoting healthy aging [11]. Although the history of FMT is extensive [8], this approach did not gain substantial attention in contemporary medicine until 2013, following the publication of the first randomized controlled trial demonstrating its efficacy in treating recurrent CDI [35]. In fact, the efficacy of FMT in restoring a healthy GM has been shown in the treatment of numerous conditions, including not only chronic gastrointestinal disorders but also a range of extra-intestinal disorders and symptoms [5, 34, 36].

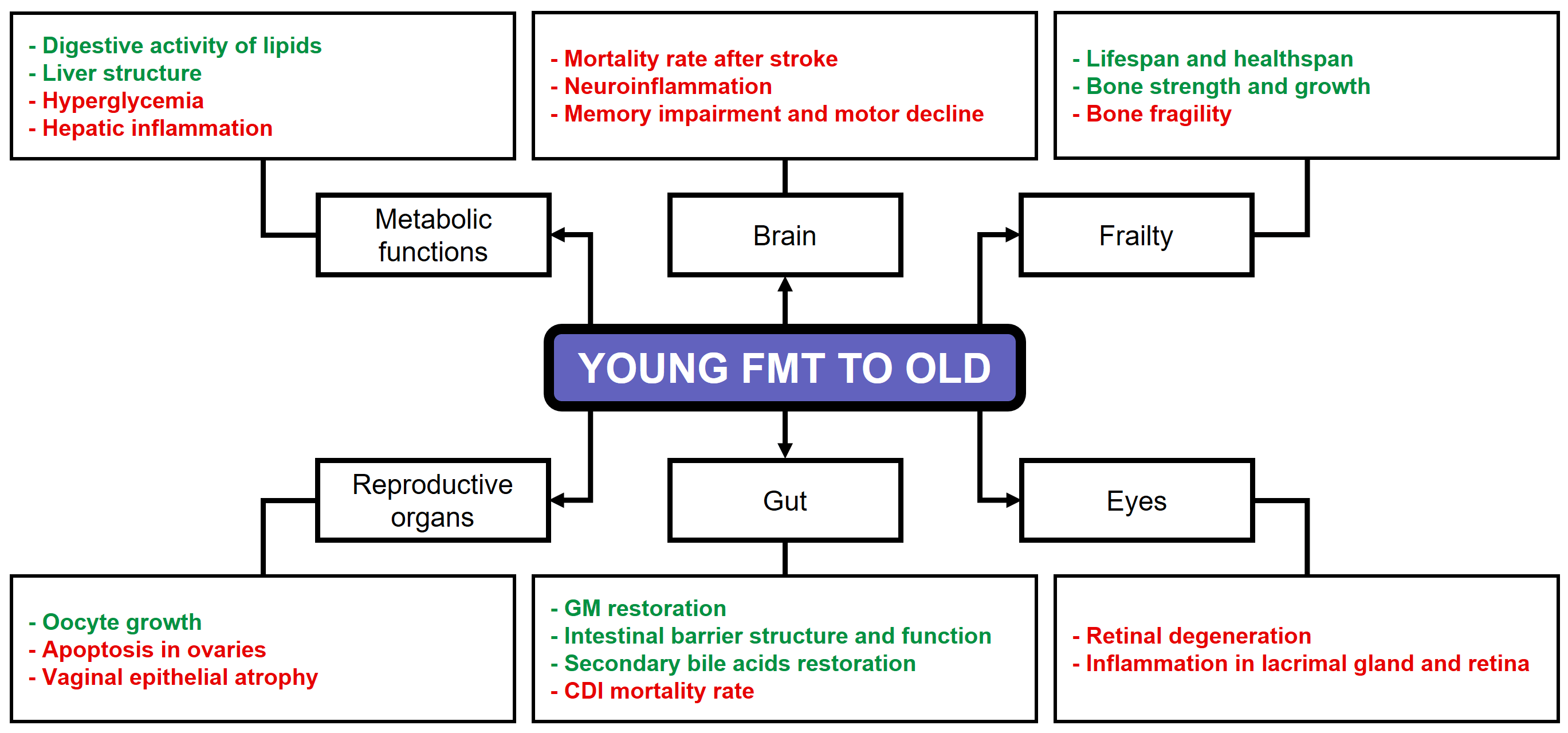

Several preclinical studies have evidenced that the administration of FMT from young donors to aged recipients can effectively restore the donor’s GM, thereby enhancing the overall health of the host and mitigating age-related sarcopenia [37, 38]. Parker et al. [39] noted that aged mice receiving FMT from young mice exhibited a substantial decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and an increase in neuroprotective cytokine expression within the retina. In addition, microbiota-derived metabolites linked to healthy aging were detected in the aged recipient mice, accompanied by a significant and beneficial metabolic shift towards pathways involving lipid and vitamin metabolism. As Boehme et al. [40] demonstrated, the FMT of younger animals has been shown to modulate age-induced changes in the immune system of the hippocampus and to influence the metabolome of this brain region. Amino acid metabolism and aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, which are pivotal for healthy cognition and brain function, were among the pathways restored by enriched metabolites. As a result, the aged recipient mice exhibited enhancements in long-term spatial memory, learning process, and a reduction in anxiety-like behaviors. In a separate study, FMT from young to older mice led to the rejuvenation of aged hematopoietic stem cells, which was achieved through the effective suppression of inflammation, likely facilitated by a microbial intervention involving tryptophan-associated metabolites [41]. Liao et al. [7] conducted a review of the beneficial effects of the FMT from young subjects to older individuals, concluding that this GM transfer improved aspects and functions associated with lifespan, brain, bone, reproductive organs, eyes, gut, and infectious and metabolic diseases. Fig. 1 illustrates several beneficial effects of FMT from young to old subjects [7].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Beneficial effects of FMT from young to old subjects. Green text: increase. Red text: decrease. FMT, fecal microbiota transplantation; GM, Gut microbiome; CDI, Clostridium difficile infection. Reproduced from Liao et al. [7].

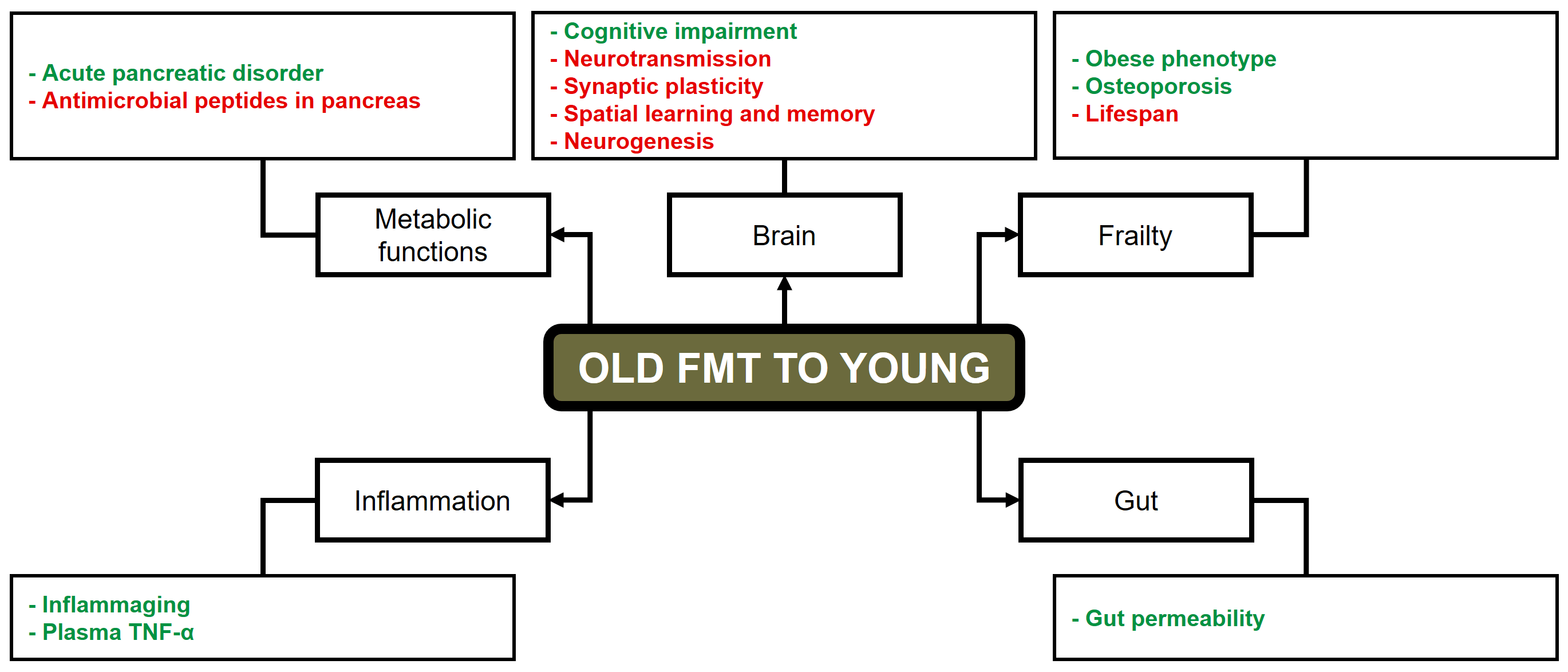

In contrast to the effects observed with the transplantation of young feces, the

transfer of aged microbiota into young animals has been shown to accelerate the

development of age-related diseases, resulting in obesity and other aging-related

phenotypes in young recipients [42]. In a germ-free mouse model, FMT from aged

donors led to an increase of systemic inflammation, as evidenced by the induction

of differential regulation in T cell differentiation, B-cell development, and a

substantial augmentation in TNF-

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Detrimental effects of FMT from old to young subjects. Green text: increase. Red text: decrease. FMT, fecal microbiota transplantation; TNF, Tumor necrosis factor. Reproduced from Liao et al. [7].

Despite the fact that a considerable number of experiments involving FMT have been conducted in animal models, only a limited number of FMT studies have been carried out in human subjects over the past five years.

Jørgensen et al. [47] performed a study involving the treatment of 4 frail elderly patients with CDI using donor fecal material administered either via nasojejunal tube or in encapsulated form. All participants aged over 80 years experienced a clinical improvement following a single FMT at week 8, marked by an enhancement in mobility and arousal levels, as well as a restoration of normal bowel function. Despite the absence of adverse events related to FMT, 2 patients received antibiotics and subsequently experienced CDI recurrence. Both patients received a second FMT via capsules, which resulted in the resolution of their symptoms. Another patient with recurrent CDI declined additional FMT due to concerns about a potential relapse. Consequently, long-term vancomycin therapy was initiated.

Doll et al. [48] found improvements in 2 patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) following the administration of oral frozen FMT capsules. In both cases, the patients exhibited a reduction in depressive symptoms 4 weeks after the transplantation and beneficial outcomes persisted for up to 8 weeks in 1 patient. Furthermore, substantial improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms were noted, along with alterations in the GM of the patients. Specifically, patient 1 exhibited an augmentation of amplicon sequence variants (ASV) from the genera Alistipes, Coprococcus, Oscillibacter, Clostridium IV, and the families Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae. In contrast, ASV from the genera Alistipes, Victivallis, Prevotella, Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, Blautia, and Ruminococcus, as well as from the family Lachnospiraceae, exhibited a decrease in abundance post-FMT. Patient 2 showed an increase in the abundance of ASV from the families Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae, and from the genera Ruminococcus, Alistipes, Bifidobacterium, and Oscillibacter, as well as from the species Flavonifractor plautii.

Ng et al. [49] conducted a study on microbiota engraftment after FMT alone and in combination with a lifestyle intervention (LSI) in 61 obese individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The available evidence suggests that the combination of LSI and FMT results in increased levels of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus in comparison with FMT administered as a standalone intervention. In addition, this combination has been observed to result in a decrease of total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, along with a reduction in liver stiffness, as evidenced by assessments conducted at week 24 in comparison with the baseline measurement.

Another study showed that FMT alleviated CDI symptoms and enhanced cognitive function in 10 elderly patients suffering from both CDI and dementia, compared to those who did not undergo FMT [26]. The FMT treatment resulted in modifications to the GM composition, notably an enrichment of members from the phylum Bacteroidota and of the genera Alistipes, Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Blautia, Barmesiella, Longicatena, and Odoribacter. In contrast, subsequent to the administration of FMT, a decline in the proportions of members belonging to the phylum Pseudomonadota (genera Hafnia, Klebsiella, and Sutterella) was documented among the recipients. Moreover, a substantial discrepancy was observed in the alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism pathways following FMT.

Hazan [50] described a case report of an 82-year-old patient with recurrent CDI and AD. The patient was hospitalized due to a pneumonia caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and subsequently underwent FMT using donor stool provided by the patient’s 85-year-old wife. Two months after treatment, the patient exhibited a resolution of his CDI symptoms, accompanied by an enhancement in his cognitive function. Half a year following the FMT the patient indicated a significant enhancement in mood, increased interactive behavior, and a greater display of expressive affect.

FMT has also been employed as a potential treatment for PD in older adults. Xue et al. [51] assessed the efficacy and safety of this procedure on 15 individuals with PD. Of the participants, 10 received FMT through colonoscopy, while the remaining 5 received FMT through nasal-jejunal tube. The colonic FMT group demonstrated a higher level of significant improvement in motor and non-motor symptoms, accompanied by acceptable safety when compared to nasal-jejunal FMT group, which had no significant therapeutic effect. Among the 15 patients with PD, 33.3% of the cases exhibited adverse events such as abdominal pain, flatulence, and diarrhea.

Later, Segal et al. [52] investigated the efficacy and safety of FMT for the treatment of motor and non-motor symptoms in 6 subjects with PD. The findings suggest that the administration of donor FMT through colonoscopy was a safe procedure that resulted in the amelioration of motor and non-motor symptoms linked to PD, including constipation at the 6-month follow-up period.

Al et al. [53] conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial enrolling

9 patients diagnosed with MS. The participants received monthly FMT

administrations over a period of up to 6 months to evaluate the safety and

tolerability of the procedure in MS, as well as to assess its potential efficacy

in improving abnormal gut permeability. The authors established that FMT was safe

for this patient cohort, with no adverse events reported. In addition, 2 patients

who presented with elevated small intestinal permeability at baseline showed

improvement to normal levels following FMT. However, no significant changes in

bacterial

Cheng et al. [54] conducted a study in which oral FMT was used for ameliorating the clinical symptoms of 27 patients diagnosed with PD. No severe adverse effects were reported in the subsequent 12-week follow-up period. Patients who received the FMT treatment exhibited substantial improvements in autonomic symptoms related to PD compared with the placebo group. Moreover, FMT improved gastrointestinal disorders with a positive correlation observed between improved gastrointestinal performance and the presence of Clostridiales bacterium 42_27, Eubacterium eligens, uncultured Blautia sp., Eubacterium ventriosum, Clostridioides difficile, Roseburia hominis, and uncultured Clostridium sp. in the GM following the treatment.

Aging is characterized by a complex and interconnected set of factors, including chronic inflammation, deficits in macroautophagy or nutrient uptake regulation, epigenetic modifications, genomic instability, GM dysbiosis, impaired intercellular communication, loss of proteostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, stem cell depletion, and telomere attrition [55]. In addition, emerging evidence highlights the degradation of the extracellular matrix [56] and the compromised integrity of physiological barriers [57]. Proteomic changes associated with aging have been linked to various age-related markers across biological, physical, and cognitive domains, such as telomere length, frailty index scores, and reaction time performance [58].

Cao et al. [59] identified three primary aging metrics. The first is the CI-PF index, which refers to the concurrent presence of both cognitive impairment and physical frailty in non-demented older adults. The second metric is the frailty index, which aggregates deficits across various domains, including cognitive and physical function, producing a score that reflects the risk of multiple outcomes such as hospitalization and mortality. The third is the motoric cognitive risk syndrome, defined by the simultaneous occurrence of subjective cognitive complaints and slowed gait. Despite their conceptual similarities, these metrics differ significantly in their operational definitions and characteristics. However, these differences have yet to be formally assessed, limiting their applicability in both research and clinical settings. Furthermore, numerous studies have shown that comorbidity in cognitively intact older adults is linked to an increased risk of functional decline, marked by the inability to perform daily activities independently. Higher comorbidity burdens, as measured by comorbidity indices, are also associated with a decline in functional autonomy among individuals with cognitive impairment [60].

As humans age, an array of biological changes unfolds, influencing a range of systems within the organism. In this respect, aging constitutes the primary risk factor for mortality in humans, driven by functional decline, increased frailty, and heightened susceptibility to chronic diseases. This process involves physiological changes in the brain, gastrointestinal disruption, and immune response alterations, many of which are influenced by the gut-brain axis [2]. Dysbiosis, marked by a loss of beneficial bacteria and overgrowth of pathogens, along with changes in metabolic activity and bacterial distribution, is a key feature of aging. As a result, the GM plays a crucial role in aging, contributing to the development of metabolic disorders and age-related diseases [61]. Thus, personalized medicine targeting GM dysbiosis offers a promising approach for managing age-related conditions [62].

The use of FMT to modulate the microbiota of the elderly has gained increasing attention, forming the focus of this review. FMT involves transferring the entire microbial community from a donor’s stool into the recipient’s intestines to normalize or alter their GM composition and function. Initially developed for treating recurrent CDI [33], FMT is now being explored in diverse therapeutic fields, including extra-intestinal conditions such as neurological and mental disorders [34]. Despite significant progress in animal models, translating these findings to humans remains challenging due to differences in microbial complexity and composition between species [63]. While preclinical results are promising, Novelle et al. [5] note that most clinical trials focus on cancer, and gaps remain in applying FMT as an anti-aging therapy.

FMT exerts therapeutic benefits through various mechanisms, such as restoring microbial diversity, modulating immune responses, promoting SCFA production, and enhancing intestinal barrier integrity. Recent studies are investigating the gut-brain axis, the role of specific microbial strains, and the potential applications of FMT beyond gastrointestinal disorders [64, 65]. In addition, nanotechnology-based strategies are being explored to improve the precision and effectiveness of FMT, with the aim of targeting specific gut regions or co-delivering therapeutic agents alongside the fecal material [66]. Furthermore, in vitro fermentation systems offer a controlled setting to examine microbial interactions and metabolism, which may expedite the development of novel FMT therapies [67].

Although FMT seems to be a valuable therapeutic approach, several factors limit its widespread clinical use. These include a lack of consensus on its definition, mechanisms of action, treatment costs, application timing and route, efficacy, tolerability, and safety. To successfully implement FMT for various diseases, it is essential to identify the optimal procedures and microbial factors that determine efficacy for each specific condition. Key areas that require further exploration include criteria for donor-recipient compatibility and preconditioning protocols for both donors and recipients. These factors are critical for ensuring the successful engraftment of donor strains and the overall effectiveness of FMT in clinical practice. The application of analytical models and artificial intelligence tools to large-scale datasets offers a promising strategy for identifying the precise factors that influence FMT outcomes [68].

A close review of the existing literature highlights several critical aspects of FMT that need to be thoroughly investigated before its widespread use in clinical practice can be justified. Central to the success of FMT is the careful selection of an appropriate donor. While autologous FMT is often ideal due to superior compatibility, it is not always feasible, making stool donors a necessity in many cases. Prior to FMT, rigorous screening of the donor’s GM for potentially pathogenic organisms is essential to ensure the safety of the procedure [69]. Research has focused on identifying the characteristics of donors whose stool samples are most likely to result in successful microbial engraftment. Donors with high taxonomic diversity and specific bacterial families are proposed to contribute to disease-specific restoration of gut homeostasis in recipients [70]. Recently, the concept of “super-donors” has emerged, referring to individuals whose fecal microbiota leads to notably higher success rates in FMT compared to standard donors [70]. Beyond donor selection, recipient factors such as genetics, diet, and lifestyle are also likely to influence the long-term success and maintenance of FMT [71].

The administration of FMT has been achieved through various methods, including upper endoscopy, nasogastric/nasoduodenal tube insertion, enemas, colonoscopy, or oral capsules. While several meta-analyses have assessed the efficacy of these delivery routes, only a limited number of studies have directly compared them [72]. Among these methods, FMT capsules have shown promising results in treating a range of pathological conditions. The lyophilized formulation of encapsulated FMT has been proven to be stable over the long term, thereby supporting its potential for sustained microbiome modulation [73]. A metagenomic meta-analysis of 24 studies demonstrated that FMT using combined delivery routes was more likely to result in successful microbial engraftment compared to single-route administration [74]. This indirect finding highlights the potential benefits of combination FMT and suggests it may be a valuable area for further investigation in future research.

Borrego-Ruiz and Borrego [8, 34] highlight the lack of standardization in current FMT protocols due to variability in pretreatment, GM analysis, administration route and dose, fecal infusion selection, and donor criteria. To address these issues, they suggest enhancing fecal bank quality and quantity, citing examples like OpenBiome and the Netherlands Donor Feces Bank, and promoting their operation both nationally and internationally. Another significant challenge in human FMT research is the study design, particularly the lack of control groups and standardized procedures. Implementing double-blind interventions with control groups would mitigate potential publication bias, especially in case reports. Regarding FMT efficacy, the variability in disease severity, particularly in brain disorders, poses a challenge. Longitudinal studies may be more suitable for evaluating outcomes in neurodegenerative diseases such as AD or PD. Furthermore, microbiota analysis results are highly heterogeneous due to differences in sample collection, DNA extraction, sequencing methods, and confounding factors such as medications, diet, and age [75]. Lastly, the mechanisms behind FMT’s efficacy remain unclear, as the treatment contains a complex mixture of viable and inactivated bacteria, other microorganisms (e.g., virome, mycobiome), and microbial metabolites (e.g., bile acids, SCFAs, proteins). Thus, it is still unknown which components are essential for its therapeutic effect.

Although FMT holds potential as an intervention for promoting healthy aging, its feasibility, limitations, and ethical implications require thorough evaluation. While FMT shows promise in restoring a healthy GM, which is closely linked to various aspects of aging, several practical and ethical challenges persist, particularly concerning donor selection, safety, and long-term effects. In terms of feasibility, several key points need to be considered [5, 76]: (i) the increasing use of oral capsules for FMT could alleviate safety concerns associated with more invasive procedures; (ii) FMT has the potential to restore a balanced GM, which is essential for overall health and may reduce the risk of age-related diseases; and (iii) research suggests that FMT may have positive impacts on frailty, cognitive function, cardiovascular health, physical performance, and even telomere length, which are factors critical to healthy aging. However, the limitations of FMT include [76, 77, 78]: (i) the need for more rigorous clinical trials to validate the efficacy and long-term outcomes of FMT for healthy aging; (ii) the variability in FMT protocols, such as pre-treatment, administration route, and follow-up procedures, all of which could influence results; (iii) the possibility that FMT effects on the GM may be temporary, necessitating repeat treatments; (iv) the risk of pathogen transmission, stool toxicity, and difficulties in reproducing positive outcomes; and (v) the scalability of FMT for widespread use, particularly for healthy individuals. The most pressing ethical concerns include [77, 79, 80, 81]: (i) the challenge of identifying and selecting suitable healthy donors, raising questions about donor health and informed consent; (ii) despite its general safety, FMT poses risks, and long-term safety data, particularly for healthy aging, remains insufficient; (iii) defining what constitutes a “suitable healthy donor” and ensuring donor safety and well-being; (iv) the importance of ensuring equitable access to FMT for individuals across different socioeconomic and geographical backgrounds; (v) the need to prevent the commercialization of FMT in ways that could exploit patients or donors; and (vi) the potential public health implications, such as the risk of antibiotic resistance or unforeseen consequences, that require careful consideration.

FMT is generally considered a safe procedure, with the majority of short-term risks linked to the method of administration, particularly endoscopic procedures, rather than to the FMT itself [82]. Common adverse effects are typically mild and transient, and may include symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, bloating, flatulence, and constipation [75]. While the transfer of live microorganisms to individuals with underlying health conditions may pose higher risks, increasing evidence suggests that FMT is well tolerated in higher-risk populations, such as immunosuppressed patients, without a significant increase in side effects [83]. Many potential risks can be minimized through rigorous donor selection and screening procedures. However, there have been notable instances where lapses in this process led to patient harm, including drug-resistant E. coli bacteremia [84]. According to Park and Seo [85], adverse events associated with FMT are influenced by factors such as stool bank practices, delivery routes, and the success of donor microbial engraftment. The long-term consequences of donor microbial engraftment may include a range of health issues, such as increased susceptibility to infections, obesity, immune-mediated disorders, and inflammatory bowel disease [86, 87].

To mitigate the risk of sepsis and eliminate potential pathobionts from donor stool, several studies have employed antibiotic treatments on the fecal matter [84]. However, this strategy is not without notable drawbacks [88]: (i) if the donor stool contains a pathogen with intrinsic or acquired antibiotic resistance to the drugs used, this approach could inadvertently increase the risk of transmission and infection by diminishing competition from other bacterial strains; (ii) the use of antibiotics may also raise the likelihood of de novo antibiotic resistance emerging within both commensal and pathogenic bacterial populations; and (iii) antibiotic treatment could lead to a reduction in overall bacterial diversity, potentially disrupting the microbial balance in the donor’s gut and promoting the unpredictable expansion of other bacteria [88].

Regarding the immune consequences of FMT, only a limited number of studies have

investigated this aspect. One study examined the effects of FMT on the immune

system in mice treated for eight weeks with a combination of five antibiotics,

followed by FMT to resolve the dysbiosis induced by the antibiotic exposure. The

depletion of microbiota caused by the antibiotic treatment resulted in a

reduction of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in both the gut and lymphoid

nodes. In addition, there was a decrease in T cells with a memory/effector

phenotype (CD44hi), Tregs, and co-stimulatory molecules in dendritic cells

[89]. The study also found that IFN-

Currently, healthy aging represents a significant goal for society, and several non-pharmacological strategies appear to be particularly suitable for its promotion. These strategies often emphasize healthy lifestyle habits, including dietary patterns, physical and cognitive stimulation within social contexts [3], as well as therapies based on microbial interventions, such as the administration of probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and FMT [4]. Among these, FMT holds particular promise, as its full viability and effectiveness are still under investigation, requiring further development and optimization to reach a more refined stage of therapeutic application. In this respect, recent advancements in FMT technology have led to innovative approaches for treating recurrent CDI, such as Washed Microbiota Transplantation (WMT) [91] and spore transplantation [92]. For future FMT treatments to succeed, it is crucial to implement rigorous screening of healthy donors, establish standardized and personalized laboratory and clinical protocols, and test whether high-quality fecal microbiota may act as an anti-aging agent.

In order to contextualize the potential role of FMT as a strategy to promote healthy aging, it is useful to consider how it compares to other commonly proposed interventions for modulating the GM, such as probiotics, dietary modification, and physical exercise. Although these approaches differ markedly in their complexity, invasiveness, and mechanism of action, all influence GM composition and function, which is increasingly recognized as relevant to age-associated physiological changes. FMT, by directly transferring a complete and mature microbial ecosystem, is hypothesized to exert broader and more immediate effects than targeted interventions such as probiotics or diet. However, it also presents significant ethical, safety, and logistical challenges that limit its routine clinical application. In contrast, probiotics, diet, and physical exercise are generally accessible, better tolerated, and widely studied in aging populations, although their effects on the GM tend to be more gradual and potentially less pronounced. Notably, clinical evidence supporting the use of these strategies in the context of aging remains variable and methodologically heterogeneous, and comparative trials are lacking. Thus, the selection of one approach over another may ultimately depend on specific clinical goals, risk profiles, and individual patient characteristics. Given the distinct advantages and limitations associated with each method, future research should aim to establish clearer criteria for intervention choice, as well as explore the possibility of combined or sequential applications.

Finally, FMT impacts aging-related phenotypes through modulation of the gut-brain and gut-liver axes. Data from single-cell sequencing and metabolomics highlight specific microbial and metabolic alterations linked to aging, as well as how FMT can reverse these changes, influencing pathways such as lipid and amino acid metabolism, and neurotransmitter production. Single-cell sequencing offers a high-resolution view of the GM, identifying cell-to-cell variability and revealing specific bacterial populations affected by aging and FMT [93]. Metabolomics further uncovers microbial metabolites that change with aging and how FMT restores them, including SCFAs, bile acids, and amino acid-derived metabolites, all of which play pivotal roles in biological processes [94]. These analyses demonstrate that FMT can modulate the levels of microbial metabolites influencing brain function. For example, increased bile acids in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease activate inflammatory pathways in microglia, disrupting neuronal function. FMT has been shown to restore these metabolic balances, alleviating adverse effects on brain health [95]. By understanding the microbial and metabolic shifts associated with aging, researchers can refine FMT protocols or develop other microbiome-based therapies to promote healthy aging [96].

The use of FMT to restructure the recipient’s GM with donor fecal samples has been applied to treat various chronic conditions in older adults, including microbial infections, metabolic disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases. The selection of an appropriate GM donor is pivotal for the efficacy and safety of FMT, with young donors showing the most beneficial outcomes. Recent studies suggest that modulation of the GM has the potential to enhance human health, mitigate the negative effects of aging, and promote longevity. Therefore, evidence supports the role of GM in facilitating healthy aging.

This review highlights recent studies demonstrating the benefits of FMT in extending lifespan and improving physiological and neurological functions. Given these findings, FMT as a personalized medicine approach shows promise as a therapeutic option for addressing aging-related effects. Nevertheless, other therapeutic modalities, such as biotherapeutic products, phagetherapy, SER-109 (purified ethanol-treated feces from the Bacillota phylum), and the CRISPR/Cas system, should also be considered for future applications.

AB-R and JJB conceptualized the research study, wrote the original draft, conducted the investigation, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Both authors participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work, no artificial intelligence tools were used.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.