1 NEC Solution Innovators, Ltd., 136-8627 Tokyo, Japan

Abstract

Saliva is a crucial bodily fluid that protects the oral cavity from infections. The composition of saliva also changes dynamically depending on conditions such as illness, stress, and diet. Thus, the organic substances in saliva, particularly enzymes, proteins, and hormones, reflect overall health status and are increasingly valued as non-invasive diagnostic tools. Aptamers, which are short single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules with high affinity and specificity, have gained attention as novel biomarker detection tools. This study explores the feasibility of employing aptamers as an innovative diagnostic technique for detecting salivary biomarkers. Specifically, we discuss the development and application of aptamers tailored to detect key salivary biomarkers, such as salivary alpha-amylase, secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA), human beta-defensin, C-reactive protein, and lactate dehydrogenase. Our group used base-appended bases to achieve high affinity and stability against targets. For instance, cortisol and sIgA in saliva are useful for assessing chronic stress and fatigue, thereby enabling objective evaluations of diseases. Enhanced techniques for measuring salivary biomarkers promise non-invasive and cost-effective diagnostic methods that can significantly contribute to early infection detection, chronic disease monitoring, and psychological stress assessment. This review underscores the extensive applicability of salivary biomarkers and provides critical insights that could improve future public health and medical care quality.

Keywords

- saliva

- aptamer

- biomarker

- diagnostic method

Saliva is a pivotal bodily fluid in humans, playing a crucial role in protecting the oral cavity from infections and serving as a lubricant that safeguards teeth and regulates enzymatic activity in the mouth. This complex mixture varies dynamically in composition due to factors such as disease, diet, and mental state. Produced primarily by the major salivary glands—parotid, submandibular, and sublingual—as well as minor salivary glands, saliva is typically generated at an average of 0.3–0.4 mL/min in adults, amounting to 500–1500 mL daily [1, 2]. Saliva is composed of 99% water and 0.5% organic and inorganic substances, including hormones, enzymes, and immunoglobulins, in addition to various cellular components. These constituents considerably contribute to oral and systemic health [3]. Major organic components include enzymes (e.g., amylase, lysozyme, peroxidase, lipase), proteins (e.g., cytokines, immunoglobulins, mucins, lactoferrin), and hormones (e.g., cortisol). The major salivary glands, including the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands, are highly permeable and surrounded by capillaries, allowing passive diffusion and active transport of substances between blood and saliva through adjacent acinar cells [4]. Consequently, some salivary components closely correlate with serum concentrations, making them useful for the diagnosis and treatment of diseases. For instance, saliva derived from the parotid gland contains amylase [5] and inflammatory proteins, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-10, IL-1

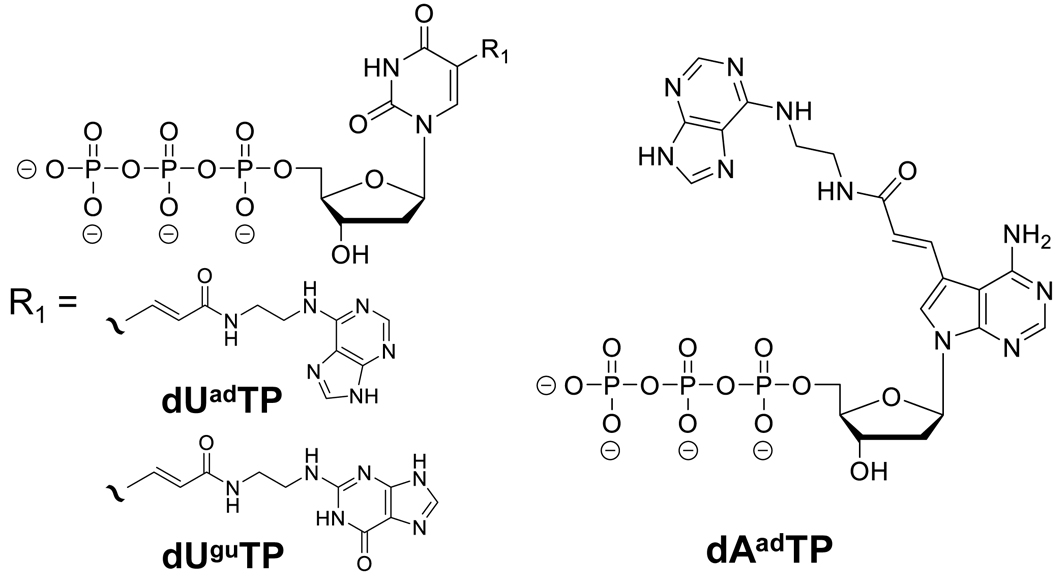

Numerous studies have focused on the applications of aptamers [13, 14, 15, 16]. Compared with antibodies, aptamers have easier chemical modification and more functionalities. Moreover, aptamers can be used as enzyme-like molecules that operate through structural changes owing to their stability at room temperature and resistance to thermal denaturation [17]. When comparing aptamers to antibodies, the advantages include stability and resistance to thermal denaturation, as well as ease of synthesis and modification [13, 18] (Table 1). These characteristics make aptamers attractive as molecular recognition elements for diagnostic agents and sensors, and combining them with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can achieve high detection sensitivity [19]. Despite many successful reports of acquiring aptamers and fabricating aptamer sensors for various targets, few reports of accurately detecting targets in body fluids such as blood are available [20]. Aptamers are selected from libraries containing random sequences and primer regions through Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) [21, 22]. SELEX has seen various adaptations since its development in 1990, including magnetic bead-based SELEX, microarray-based SELEX, nitrocellulose filter-based SELEX, capillary electrophoresis SELEX, and cell SELEX [23]. We employed a magnetic bead-based SELEX method as a means of selecting aptamers for protein markers in saliva, referencing the SOMAMAR development approach by SomaLogic [24]. The selection buffer (SB) used was a HEPES-based buffer (40 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.01% Tween 20). In the first round, a 20 pmol single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) library was mixed with 250 µg of target beads at 25 °C for 15 min, washed with SB, and then eluted with bead-bound ssDNA using 7 M urea. Washing was performed three times in the first and second rounds and five times from the third round onward. The eluted ssDNA was amplified by PCR using a forward primer and a biotin-modified reverse primer, and the amplified dsDNA was used to prepare the ssDNA library for the next round. After eight rounds of selection, the sequences in the library were analyzed by next-generation sequencing, and candidate clones were selected by considering sequence frequency and motif sequences. Binding to the target protein was confirmed using multiple methods, including surface plasmon resonance assay, electrophoretic mobility shift assay, and fluorescence polarization binding assays. However, obtaining high-affinity aptamers for some targets using SELEX with only natural bases is limited by functional and structural constraints. To overcome this issue, several scholars have attempted to develop DNA/RNA aptamers incorporating modified bases. In 2010, slow off-rate modified aptamers (SOMAmers™) with high binding affinities for various protein targets were demonstrated for the first time [25]. Incorporating modified uracil and cytosine bases in addition to natural nucleic acids produces aptamers with high binding affinities and low dissociation rates [26, 27, 28]. Our group has utilized this technology to identify several aptamers that specifically bind to targets from three types of libraries incorporating base-appended base (BAB) modifications: uracil analog adenine derivatives at position 5 (Uad), uracil analog guanine derivatives at position 5 (Ugu), and adenine analog adenine derivatives at position 7 (Aad) (Fig. 1, Ref. [29]).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Chemical structures of adenine derivative at the fifth position of uracil (dU𝐚𝐝TP), guanine derivative at the fifth position of uracil (dU𝐠𝐮TP), and adenine derivative at the seventh position of adenine (dA𝐚𝐝TP) [29].

| Aptamer | Antibody | ||

| Quality and Features | Affinity | 10 pM to 10 µM | 10 pM to 10 µM |

| Specificity | Highly specific | Highly specific | |

| Stability | pH 5 to 9, –80 to 100 °C, liquid or dry | pH 5 to 8, sequence specific, empirically determined, –80 to 4 °C | |

| Size | Small molecules | Relatively large by comparison | |

| Application Characteristics | Synthesis method | Chemical | Biological |

| In vitro SELEX takes only 2–8 weeks | Produced in vivo | ||

| No batch-to-batch variation | More than 6 months | ||

| Batch-to-batch variations | |||

| Modifiability | Easily modified without losing affinity | Modifications often reduce activity | |

| Modifications possible at 5′ end, 3′ end, and internally, well-controlled | Difficult to control; typically conjugated with one type of signaling or binding molecule |

SELEX, Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment.

By leveraging salivary biomarkers, non-invasive diagnostic methods that replace traditional invasive techniques such as blood draws and biopsies can be realized, reducing the burden on patients and improving diagnostic rates, especially in pediatric, older adults, and psychologically burdened patients [30, 31]. Salivary diagnostic techniques are effective for a wide range of diseases, including periodontal disease, dental caries, cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and infections [30, 32, 33]. Moreover, the utilization of salivary components has furthered the diagnosis and evaluation of respiratory diseases, with promising applications in asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pneumonia [31]. Additionally, beyond disease utility, salivary biomarkers can capture early signs of chronic stress leading to psychological disorders. For instance, physicians, caregivers, nurses, social workers, teachers, and other individuals working in emotionally demanding fields are at a higher risk of burnout due to chronic stress [34]. Therefore, profiles of salivary biomarkers could serve as highly sensitive markers for disease evaluation and chronic stress visualization.

In this review, we focus on aptamers as a method for measuring salivary biomarkers. Based on our research techniques and reports from other research institutions, we detail the utility of aptamers in detecting salivary biomarkers.

Saliva is instrumental in diagnosing and prognosing diseases because it contains a variety of proteins that can be used to investigate the effects of acute and chronic stress on physical health [35, 36]. These salivary proteins range from high-molecular-weight glycoproteins to low-molecular-weight proteins and peptides. Proteomics profiling of saliva has identified over 3000 different proteins [37]. Among the 1939 proteins detected in saliva, 597 are also found in plasma, rendering saliva functionally equivalent to serum. Human salivary glands contain numerous peptides and hormones, making saliva an attractive, non-invasive alternative to plasma or serum hormone testing in recent clinical research.

Measuring proteins in saliva allows stress states to be estimated and various systemic and local diseases to be diagnosed rapidly. The stress response of the nervous system involves stimulation of the hypothalamus and brainstem and activation of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, the autonomic nervous system (ANS), and the sympathetic–adrenomedullary system. Stress stimuli activate the HPA axis and ANS, resulting in the production and secretion of specific hormones [38]. These systems work in concert with the immune system and play a key role in the pathogenesis of stress-related diseases [39]. All such compensatory responses of the body are reflected in biomarkers present in blood or saliva. Representative salivary stress biomarkers include salivary alpha-amylase (sAA), secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA), chromogranin A, and cortisol. Here, we introduce the roles of these biomarkers, including reports of aptamers specifically binding to salivary biomarkers identified by our research group (Table 2, Ref. [29, 40, 41, 42]). The salivary biomarkers identified by our research group are proteins classified as markers of stress response, immunity, and inflammation.

| Target | BAB-modified DNA(a) | Length(b) | Kd (nM)(c) | Reference |

| Salivary α-amylase | dUadTP | 50 | 0.45 | [40] |

| Secretory Immunoglobulin A | dUguTP | 41 | 3.7 | [41] |

| Human β-Defensin 4A | dAadTP | 69 | 8.07 | [42] |

| C-Reactive Protein | dUguTP | 48 | 0.0062 | [29] |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase 5 | dAadTP | 44 | 0.24 | [29] |

(a) The three types of libraries incorporate base-appended base (BAB) modifications: adenine derivative at the fifth position of uracil (dUadTP), guanine derivative at the fifth position of uracil (dUguTP), and adenine derivative at the seventh position of adenine (dAadTP). (b) The length of each aptamer is indicated. (c) The dissociation constant (Kd) indicates the binding strength between each aptamer and the target protein.

sAA, a major digestive enzyme in the oral cavity, is responsible for the hydrolysis of starch and glycogen. It also plays a role in immune defense against oral microorganisms. In healthy individuals, sAA concentration is lowest early in the morning and peaks in the late afternoon [43]. sAA secretion is regulated by the sympathetic nervous system and norepinephrine, and its concentration increases in response to acute stress. Additionally, sAA activity increases in patients under chronic stress, making it a reliable and objective biomarker of potential stress [44, 45]. sAA is highly sensitive to changes in body stress mediated through the nervous system [46, 47]. Moreover, its levels significantly increase in patients with diabetes compared with healthy individuals, indicating its use a diagnostic marker for diabetes [48].

Our research group attempted to acquire aptamers with high affinity for sAA. However, we were unable to obtain sAA-binding aptamers from a natural single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) library incorporating BAB modifications. Nevertheless, we successfully acquired high-affinity sAA aptamers by employing a modified DNA library enzymatically synthesized with dUadTP instead of thymidine 5′-triphosphate. The reported sAA aptamers (AMYm1-3) contain 11 modified bases ((E)-5-(2-(N-(2-(N6-adeninyl)ethyl))carbamylvinyl)-uracil) within their sequences. Comparison of AMYm1-3 with sequences where the modified bases are replaced with natural bases (AMYm1-3N) revealed that AMYm1-3 retains a stable secondary structure, demonstrating that the modified bases intrinsically contribute to the enhanced target binding affinity and specificity of the aptamers. Furthermore, the detection capability of AMYm1 for sAA in saliva was validated through multiple analytical methods, including lateral flow assays. Correlation analysis between the lateral flow assay and ELISA for different concentrations of sAA in human saliva revealed a correlation coefficient of 0.942, indicating a very strong positive correlation. Based on these results, the high correlation with ELISA confirmed the utility of AMYm1, facilitating the quantitative detection of sAA in saliva [40].

sIgA in saliva is an antibody found in mucosal areas and acts as the first line of defense protein upon contact with infectious pathogens or allergens [49]. sIgA has been explored as an indicator of immune system function [50]. Recently, a connection has been identified between the activation of the HPA axis due to chronic stress and a decrease in immune system activity, including sIgA [49]. A strong correlation exists between decreased sIgA levels and perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and anxiety [51]. Stress has also been associated with upper respiratory infections, with sIgA suggested as a reliable biomarker for identifying infection risk in athletes [52].

While IgA in serum exists mainly as a monomer, the majority of sIgA in excretory fluids such as saliva exists as a dimer, with a concentration range of 0.6–1.2 µM [50]. Structurally, sIgA differs significantly from IgA found in the serum. sIgA is a dimer and higher-order polymer linked by a J chain and forms a complex with a glycosylated secretory component protein [53]. Interestingly, sIgA has not been reported to bind to nucleic acids other than the hemagglutinin protein of the influenza A virus [54]. Our group has identified an aptamer with high binding specificity for the dimeric form of sIgA present in saliva, which does not bind to IgG or serum IgA. The binding specificity was confirmed by measuring the binding affinities for sIgA, IgG1 kappa, IgG, IgG-Fc, and serum IgA using a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) instrument. The SPR response curves for the interaction between the identified aptamer and sIgA or other types of IgG and serum IgA demonstrated high binding specificity for the dimeric form of sIgA present in saliva. This specific aptamer was selected from an ssDNA library incorporating BAB modifications, which included the introduction of a guanine base at position 5 (Ugu). Natural ssDNA could not bind to sIgA, highlighting the importance of BAB modifications for recognizing sIgA-binding sites [41]. To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to report an aptamer binding to sIgA in human saliva, suggesting its application in a system for the simple measurement of sIgA in saliva.

HBD is primarily expressed in respiratory epithelium [55] and functions as an antimicrobial peptide and a chemoattractant involved in immune inflammatory responses [56]. Serum HBD-2 is being studied as a biomarker for predicting infectious and immune-inflammatory diseases, such as spondyloarthritis [57], dermatophytosis [58], atopic dermatitis [59], and early neurological deterioration after stroke [60]. HBD-2 is also secreted in saliva and has been reported as a marker related to the immunological state of the oral cavity, including defense against infections by periodontal pathogens [61]. Additionally, it has been associated with physical stress [62]. Our group aimed to obtain HBD-2-binding aptamers by using a random ssDNA library incorporating three modified bases: Uad, Ugu, and Aad. Consequently, we successfully obtained clones that strongly bind to HBD-2 from the Aad pool, which included the introduction of the modified nucleoside triphosphate dAadTP into the analog Aad of BAB modifications. While HBD-2-binding clones were also obtained from the Ugu pool, they demonstrated weaker binding than the Aad clones, indicating that Aad was more effective for acquiring HBD-2-binding aptamers [42]. Generally, HBD-2 is measured using the cumbersome and time-consuming ELISA. However, the identified HBD-2-binding aptamers hold potential for developing a simple and convenient measuring method suitable for on-demand monitoring of various conditions, such as those in athletes.

Human C-reactive protein (CRP) is a marker of acute inflammation because its concentration in serum can increase over 1000-fold during severe inflammatory states [63]. CRP is also secreted into saliva, showing a strong correlation with serum CRP levels [64]. Although the concentration of CRP in saliva is approximately 2 ng/mL, which is approximately 1/1600th of the level in serum [65], it is considered useful for the non-invasive evaluation of cardiovascular diseases, oral diseases, and as a marker for pneumonia in infants [66, 67]. Our group explored aptamers that bind to CRP using a ssDNA library incorporating three types of BAB modifications (Uad, Ugu, and Aad). As a result, we obtained several candidate sequences from the Ugu ssDNA library, successfully identifying CRP-Ugu4 with high binding specificity to CRP [29]. Additionally, to enhance target-binding capability and reduce structural instability, we minimized the identified aptamer sequence. The minimized aptamer, which had its 5′ end truncated, demonstrated higher CRP binding affinity than the original CRP-Ugu.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), a detectable enzyme present in the cytoplasm of almost all human cells, is associated with cell necrosis and organ damage as it is released into the bloodstream upon cell death [68]. LDH is a frequently measured enzyme, with subtypes ranging from LDH-1 to LDH-5 [69]. The isoenzymes of LDH activity differ between saliva and blood: LDH-5 is predominant in saliva, while LDH-1 is predominant in blood [70]. Abnormalities in LDH-5 levels in saliva have been associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma, functioning as an indicator for early tumor markers [71]. However, the measurement of LDH is primarily based on activity assays, with diagnostic applications still underdeveloped. Our group identified three candidate aptamers for LDH-5 (Uad1, Ugu3, and Aad1) and successfully identified LDH-Aad1 as a specific aptamer that does not show cross-reactivity with LDH-1 (another LDH isoenzyme). The binding specificity was confirmed by the SPR response curves of the interaction between the candidate aptamers and either LDH-5 or LDH-1. Among the three LDH-5 candidate aptamers, LDH-Aad1 did not show binding to LDH-1. Despite the 75% sequence homology of the LDH-5 amino acid sequence with that of LDH-1, LDH-Aad1 demonstrated very high binding specificity for LDH-5. Additionally, by truncating LDH-Aad1 to 44 bases, we acquired an aptamer with even higher binding affinity for LDH-5 [29]. Despite previous reports on LDH-binding aptamers, the identified sequences and their specific target binding sites had not been elucidated [72]. LDH-5 possesses Rossmann-fold, a substructure that interacts with dinucleotides such as FADH and NADH [73], potentially facilitating the binding to LDH-Uad, LDH-Ugu, and LDH-Aad aptamers with BAB modifications.

The aptamers we identified maintain specificity for LDH-5 and hold potential as tools for the early diagnosis of oral cancer.

Salivary biomarkers are measured not only to detect infections and diseases but also to capture early signs of mental health deterioration due to stress. For instance, salivary stress markers such as cortisol, sAA, and CgA are useful in diagnosing acute and chronic stress, anxiety, and depression [74]. Chronic stress can lead to a wide range of physical and psychological disorders. Whether an experience is perceived as stressful depends on factors such as environment, socioeconomic stability, past personal history, and mental health, making physiological estimation challenging. Continuous responsibilities, anxiety, a sense of hopelessness, and lack of prospects can amplify this experience. Thus, physicians, caregivers, nurses, social workers, teachers, and other individuals working in fields with continuous emotional pressure are considered at high risk [35]. Generally, increased stress load leads to symptoms summarized as burnout. Chronic stress and burnout affect physiological responses, coping, and adaptation to future acute stress events, making their diagnoses increasingly important for health protection [75].

Our research group focused on nurses and conducted a proof-of-concept study on the connection between salivary profiles and early signs of chronic fatigue and turnover intention, highlighting the significance of salivary profiles. Nursing duties involve high physical demands, long working hours (including mandatory overtime), night shifts, and short rest periods between shifts, leading to significant fatigue accumulation and subsequently to chronic fatigue [76]. Chronic fatigue in nurses has been associated with burnout, turnover intention [77], and decreased job performance [78], making its management and prevention crucial. However, fatigue in nurses is usually measured using self-report questionnaires, which lack objectivity and may not be sufficiently accurate [79]. Therefore, establishing an assessment method combining self-report questionnaires and evaluations of objective indicators is necessary to fully understand chronic fatigue in nurses. Our group investigated the association between physiological markers in saliva and chronic fatigue in nurses and found that cortisol and s-IgA levels may be related to chronic fatigue. We further suggested the necessity of measuring cortisol and s-IgA levels in saliva to address fatigue risk effectively [80]. Other research groups have reported that cortisol profiles serve as stress indicators for educators, a profession with high potential stress [81]. Additionally, salivary cortisol, sAA, and CgA are promising tools for exploring COVID-19-related stress [82].

Nursing accounts for over 50% of the global healthcare workforce shortage; thus, detecting early signs of turnover and implementing preventive measures are also crucial. Identifying at-risk nurses is essential to prevent turnover. Cortisol is a physiological marker associated with job stress [83], chronic fatigue [84], and burnout among healthcare workers [85]. Our research group explored the potential of predicting nurses’ intent to stay by combining the physiological marker cortisol in saliva with subjective indicators. Previous studies reported that burnout and other psychological factors only partially explain nurses’ turnover intentions [83, 85]. In our study, we revealed that using cortisol profiles as an objective indicator is associated with the extent of nurses’ reluctance to stay 3 months later [86]. This approach enables the prediction of intent to stay, providing support and an early intervention preparation period for individuals at high risk.

The salivary biomarkers introduced in this review have the potential to function as highly sensitive markers for visualizing chronic stress, chronic fatigue, and immune status. Generally, these biomarkers are measured using antibody-based methods, including ELISA, and are widely utilized in research and treatment. However, ELISA is complex and time consuming, making it challenging for point-of-care use. Additionally, large cohort study requires the development of evaluation systems that can measure multiple markers simultaneously at a low cost [13]. For example, simple methods utilizing amylase activity for measuring sAA concentration have been developed and implemented [87], but they are highly susceptible to pH and salt concentration interference and cannot measure multiple markers simultaneously. Therefore, novel technologies other than ELISA need to be developed urgently for measuring salivary biomarkers.

Aptamers are useful tools that are more resistant to thermal denaturation than antibodies, can be stored at room temperature, and can be synthesized at a low cost. Particularly, the BAB-modified ssDNA introduced in this review has the advantage of high binding affinity to targets. However, obtaining aptamer candidates with high binding affinity to targets requires a large-scale oligonucleotide sequence, and the time and cost for analysis can be substantial. Techniques such as ValFold [88] and fast string-based clustering [89] reported by our group address these challenges, significantly improving the efficiency and accuracy of designing and analyzing aptamers in silico. Assay profiles must be conducted in large cohorts to define the concentration and activity range of individual markers and enhance the value of point-of-care applications. Specifying appropriate sampling times is also an important consideration because some markers exhibit circadian rhythms. From a societal perspective, the measurement of salivary biomarkers is expected to significantly contribute to the prevention, early detection, and management of chronic stress and fatigue. Our group’s proof-of-concept study has shown that salivary cortisol and IgA levels are associated with chronic fatigue, enabling accurate state evaluations using these biomarkers. Furthermore, a recent study has focused on the clinical applications of aptamers in detecting salivary biomarkers for various diseases. For example, an aptamer-based biosensor has been developed for the rapid detection of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) nucleocapsid protein in saliva, achieving high specificity and low detection limits in a short time, which holds promise for practical use in field diagnostics [90]. Aptasensors for detecting carcinoembryonic antigen in saliva have also been developed [91]. These technologies have shown great potential as non-invasive methods for the rapid and accurate detection of diseases such as oral cancer and periodontitis [92]. Such advancements suggest that salivary diagnostics using aptamers could significantly contribute to the early detection and management of diseases across various medical fields. However, these non-invasive diagnostic methods using salivary biomarkers still face several limitations and challenges in their clinical application. Current technologies do not possess sufficient sensitivity and specificity for all applications. Despite advances in molecular technology improving detection capabilities, sensitivity issues in detecting low concentrations of biomarkers in saliva remain [33]. Furthermore, despite the advantages of non-invasive saliva collection methods, skepticism persists among healthcare professionals regarding the clinical utility of salivary diagnostics compared to traditional blood tests [92]. Extensive trials and validation studies in real clinical settings are necessary to establish the reliability of these new diagnostic tools. Future research should focus on refining profiles using these aptamers and establishing protocols for practical patient care and health management. Additionally, expanding cohort studies to include diverse individuals and groups is necessary to confirm the broad applicability of salivary biomarkers. Such studies could contribute to improving public health and healthcare quality.

Salivary biomarkers—particularly detection technologies utilizing aptamers—have potential crucial roles in the future of societal health management. These technologies could significantly contribute to the early detection of infections, monitoring of chronic diseases, and even the assessment of stress and mental health as non-invasive and cost-effective diagnostic methods.

TS designed the study. TS, HM, and YA conducted the research. IS provided significant help and advice on the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors contributed to the manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

NEC Solution Innovators provided support in the form of salaries for Takahiro Shiga, Hirotaka Minagawa, Yu Akiyama, and Ikuo Shiratori.

All authors declare no conflicts of interest. Despite they received sponsorship from NEC Solution Innovators, Ltd., the judgments in data interpretation and writing were not influenced by this relationship.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.