1 Drug Design and Bioinformatics Unit, Medical Biotechnology Department, Biotechnology Research Center, Pasteur Institute of Iran, 13164 Tehran, Iran

Abstract

Network science has emerged as a powerful tool for understanding complex systems, including biological and social networks, and has given rise to the innovative field of network medicine. By leveraging the principles of network science, network medicine seeks to unravel the intricate molecular interactions that drive disease, offering insights beyond what traditional single-parameter analyses can provide. However, despite its potential, network medicine faces significant challenges. The molecular networks it relies on often suffer from limitations such as incomplete data, static representations of dynamic processes, and a lack of experimental validation, which hinder their reliability in addressing multifaceted medical problems. This review critically evaluates these limitations and explores how network science can be refined to better support the goals of precision and personalized medicine. We propose a series of solutions to address these challenges, including the integration of multilayer networks to capture the complexity of biological systems, the continuous feeding of networks with updated, high-quality data, and rigorous experimental validation to ensure the accuracy of network predictions. Additionally, we emphasize the importance of incorporating temporal and spatial dynamics into network models to more accurately reflect the evolving nature of diseases. By providing a comprehensive analysis of the current state of network medicine and identifying key areas for improvement, this review outlines a roadmap for the future of the field. It highlights the critical need to bridge the gap between theoretical network models and their clinical applications, ensuring that the insights gained from network science can be translated into practical tools for disease diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Through these advancements, network medicine holds the potential to revolutionize healthcare, leading to more precise, targeted therapies and ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Keywords

- molecular medicine

- network biology

- precision medicine

- network challenges

Complex networks have become a popular analytical tool for a range of field, it can be a kind of social connections, or systems which related to ecology or transmission of diseases [1]. Represented graphically through nodes and edges, networks provide not only a visual representation of relationships between components, but also offer critical insight into overall network structure and stability [2].

The intricate components of biological systems such as genes, metabolites, and proteins provide an ideal opportunity for the application of graph theory and network science [3]. By studying the interactions and connections within these systems, researchers can gain new insights and address complex problems that may not be solved by studying individual components alone [4]. Taking a network-centric approach to biology may open up new avenues for investigation and offer hope for overcoming the obstacles of reductionist perspective [5]. By viewing biological systems as networks, researchers can potentially gain a deeper understanding of their complexity and pave the way for significant progress in the field.

Ravasz et al. [6] argued that we have seen the emergence of network science. Network medicine aims to combine data obtained from biomedical research with modeling approaches that appropriately fit these data, in order to derive information on disease markers, therapeutic targets, phenotypic genes, interactions between genes, and subtypes of diseases. However, as with any rapidly emerging area of study, challenges such as poorly defined pathways remain [7, 8].

In many applications, Network Medicine tries to exploit cellular and molecular pathways to find the etiologies of diseases. However, since all these pathways are not well defined or are only partially understood, relying solely on them can limit our understanding of disease mechanisms. This incomplete knowledge can hinder the identification of key therapeutic targets and the development of effective treatments, as diseases often arise from complex interactions beyond the molecular level, including environmental, genetic, and epigenetic factors [7].

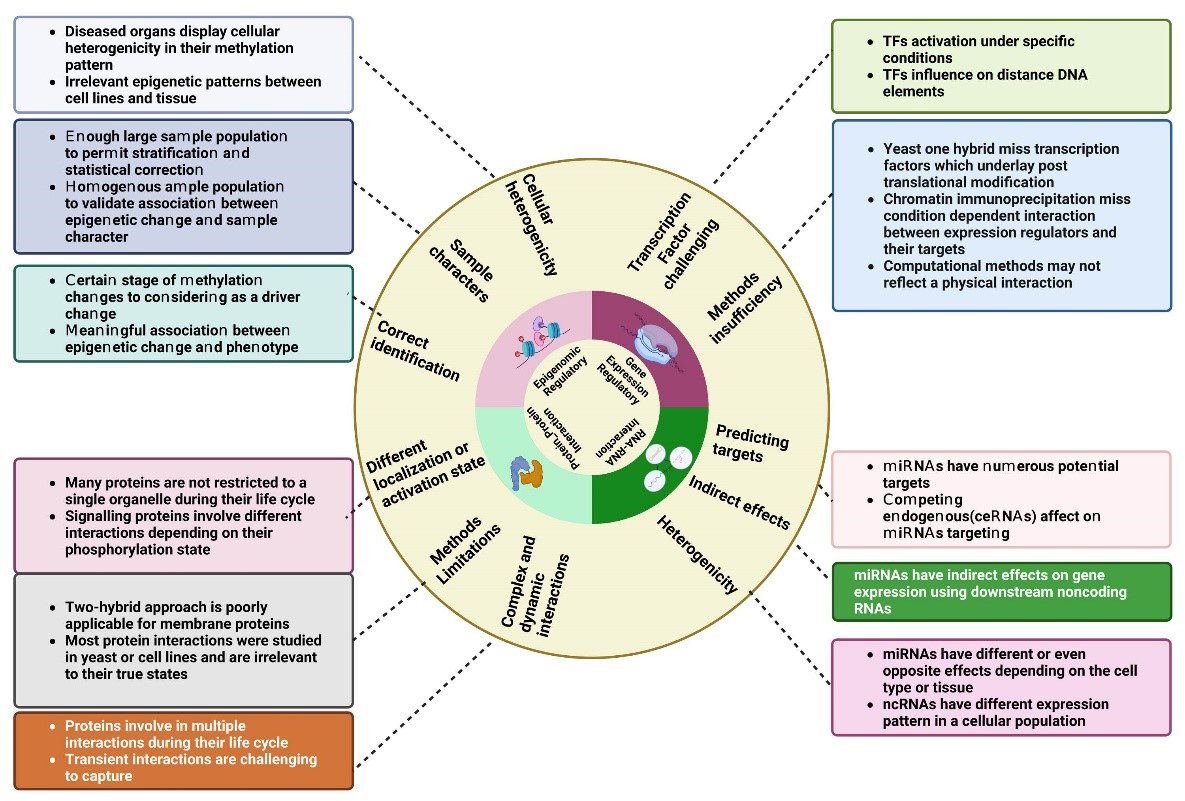

In the following we argue different molecular networks and mentioned their challenges to using them in network medicine (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The figure illustrates four fundamental pillars of network medicine research. Each pillar is accompanied by a set of obstacles that are emblematic of this area of research, represented by outer circle of the figure. On the margins of the circle, each challenge is outlined in detail. TFs: transcription factors; miRNAs: microRNAs. Created with BioRender.com.

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) are key players in biological processes. A significant study showed that PPIs aberration have meaningful association with a range of diseases from cancer to infectious diseases [8]. Therefore, targeting PPIs is an appropriate approach in treating diseases and a proper strategy due to development of effective drugs. Drug discovery faced with challenges due to PPIs modulation in the past few decades [8].

The Integrated Interactions Database (IID) and STRING databases are utilized to construct the Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks [2, 9]. Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) integrates various types of interaction data, including experimentally validated interactions and predicted interactions based on homology, text mining, co-expression, and genomic context. IID, on the other hand, aggregates interactions from curated databases as well as computational predictions. Both databases apply scoring systems to rank interactions, with STRING providing a confidence score based on the evidence type and source reliability [10].

It is important to note the difference between experimentally validated networks, which rely on direct evidence from methods such as yeast two-hybrid assays or co-immunoprecipitation, and predicted networks, which infer interactions based on indirect evidence. While experimentally verified interactions offer higher reliability, they may not capture the full complexity of biological systems. Predicted networks, although sometimes less reliable, can provide broader insights into potential functional associations, especially when experimental data is limited. Thus, the integration of both types of data enhances our ability to map comprehensive PPI networks, but careful consideration must be given to the confidence scores and reliability of each interaction [11, 12].

Proteins have distinct domains and motifs that provide functionality and regulate interactions. Protein interactions are complex and dynamic, with each protein involved in multiple interactions throughout its life cycle. Factors such as localization and activation state influence these interactions. Mapping the human interactome, while a popular idea, is currently more fantasy than reality due to the intricate and ever-changing nature of protein interactions [13, 14, 15].

The Human Reference Interactome (HuRI) is a study that has identified around 53,000 protein-protein interactions, providing a comprehensive framework for examining human cellular functions. However, the Yeast- Two- Hybrid (Y2H) assay utilized in this study has certain limitations that led to the exclusion of several PPIs, as it has low sensitivity and can only detect interactions in half of the proteins tested. Nonetheless, this outcome can help scientists create better strategies to map the interactome further and include the missed proteins. However, post-translational processing of human proteins and interactions that require additional partners may be difficult to detect by Y2H, as well as interaction partners present in alternative splice forms. Therefore, accurately estimating the size of the interactome continues to be a challenge [16, 17, 18].

Gene regulation plays a crucial role in the complex interplay of multiple biological molecules. This relationship involves the coordinated activity of regulatory proteins, including transcription factors, microRNAs, and epigenetic modifiers, that bind to specific regions in the DNA that control the amount of mRNA transcribed and then translated to protein. Despite significant advances, there is still much to learn about gene regulatory networks (GRNs) and their intricate workings [2].

To map out GRNs, several high-throughput techniques have been developed, each with its own strengths and limitations. Common methods include computational inference, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq), and yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assays.

Computational inference uses gene expression data to predict regulatory interactions, often by reverse-engineering the network from expression patterns. This approach is scalable but can suffer from false positives, as it doesn’t guarantee that predicted interactions are physically direct or functional under all conditions. Algorithms such as Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks (ARACNe), GeNe Network Inference with Ensemble of Trees (GENIE3), and Inferelator infer these networks by identifying co-expression motifs or regulatory elements [19, 20]. However, they require validation through experimental methods.

ChIP-seq identifies the binding sites of transcription factors (TFs) on a genome-wide scale by immunoprecipitating TF-DNA complexes. While powerful, this technique can miss condition-dependent interactions, as it captures interactions at a specific time point and often requires sophisticated peak-calling algorithms to identify true binding events. Additionally, databases such as Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE), ModEx and Joint Annotation of Sequence Patterns Analysis and Recognition (JASPAR) store ChIP-seq-derived regulatory interactions, providing valuable resources for Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) construction [21, 22].

Yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assays help identify TFs that bind to specific DNA sequences. However, Y1H may miss TFs that require post-translational modifications or dimerization with other proteins to bind DNA effectively. Moreover, Y1H assays are not yet widely applicable for detecting heterodimeric TF interactions [23]. For post-translational regulation, mass spectrometry-based proteomics can complement Y1H by detecting protein modifications that alter DNA-binding activity [9].

GRNs are often inferred from interaction motifs, including feedforward loops and feedback loops, using computational methods and validated experimentally. Some databases (such as STRING) aggregate experimentally validated interactions and predicted regulatory motifs, which further facilitate the construction of GRNs [24]. Combining these tools ensures a more comprehensive and accurate map of regulatory networks. Despite the power of these approaches, no single method can fully capture the complexity of GRNs, which underscores the need for integrative strategies combining both computational predictions and experimental validations.

Validation experiments come with inherent limitations, and negative results do not necessarily invalidate the original interactions identified in high-throughput study [11]. For example, RNA interference (RNAi), a commonly used gene silencing technique, has known off-target effects that can complicate data interpretation, particularly when applied in complex systems [11]. Additionally, RNAi is not tissue-specific, and certain tissues or cell types may be less responsive to this method.

However, in recent years, RNAi has largely been replaced by the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats-associated System (CRISPR-Cas) system, which provides a more precise and effective tool for genome editing, including the knockout of transcription factors [12]. CRISPR-Cas genome editing allows for permanent gene disruption and can target specific transcription factors with high fidelity, but it also comes with challenges, such as off-target mutations, inefficiencies in some cell types, and difficulties in delivery [25, 26].

When validating Y1H interactions by ChIP, it is important to perform the experiment using samples under conditions where the transcription factor (TF) is active [13]. Some TFs may be functionally dormant until activation by a ligand or signaling pathway, and regulatory effects may only be detectable under activation conditions [14]. It has become clear that many physical interactions do not convey a detectable regulatory consequence on their predicted target genes [15]. Physical interactions between TFs and genomic DNA fragments are often inferred to affect the gene that is in closest linear proximity to the binding event, but this assumption may not necessarily hold for interactions involving more distant DNA elements [13]. Integrating physical and regulatory interaction data with structural genome and DNA looping data will facilitate the further dissection of GRNs.

Recent advancements in RNA biology have greatly expanded our understanding of RNA-mediated regulatory systems, revealing a diverse range of RNA-RNA interactions that are crucial for controlling gene expression and protein output. These networks involve interactions between small RNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs), and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), among others, forming complex regulatory loops. Both miRNAs and lncRNAs contain structural domains that enable them to bind other RNAs through complementary base pairing, creating RNA-RNA hybrids that regulate gene expression in multiple ways, including RNA stability, translation, and splicing [27, 28].

miRNAs typically function by binding to the 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs) of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) to repress their translation or induce degradation. This interaction is highly context-dependent, as miRNA efficacy can vary across different cell types and environmental conditions [16]. The functional outcomes of miRNA activity are also influenced by lncRNAs, which can act as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs). These ceRNAs sequester miRNAs by competing for shared binding sites, thus modulating the repression of their target mRNAs and adding an additional layer of post-transcriptional regulation [17].

Furthermore, understanding the regulatory roles of miRNAs is complicated by their broad range of targets and the challenges of accurate target prediction. Each miRNA has multiple potential mRNA targets, and distinguishing true functional interactions from false positives remains a significant challenge. Advanced computational tools and experimental validation strategies, including cross-linking immunoprecipitation sequencing (CLIP-seq), have improved the identification of miRNA targets, but these methods still have limitations [18].

Additionally, the competitive interaction between miRNAs and ceRNAs introduces another challenge. LncRNAs, circular RNAs, and other RNA species can “sponge” miRNAs, reducing their availability to interact with target mRNAs and thus altering gene expression networks. This ceRNA activity adds complexity to the regulatory landscape, making it difficult to disentangle direct from indirect effects in RNA-RNA networks [19].

Epigenetics refers to a range of mechanisms that influence gene expression patterns without altering the DNA sequence. Two primary components of epigenetic regulation are DNA methylation and modifications to histones, along with chromatin remodeling complexes, microRNAs, and nuclear architecture. These factors determine the organization of a gene’s chromatin and its transcriptional activity. Epigenetic changes are critical for establishing and maintaining cellular differentiation. While certain epigenetic marks are established early in life, they may adapt throughout one’s lifetime in response to intrinsic and external stimuli and potentially lead to the development of diseases and cancer later in life [20].

To obtain meaningful results from epigenomics studies, several parameters must be considered for accuracy. Inadequate hypothesis, convenience-based studies, inappropriate tissue selection, mixed cell samples, and uncontrolled population structure and biological variability can all contribute to unreliable results. Insufficient sample sizes, causation and confounding identification, selection bias, misclassification, and other biases can also impact the validity and reliability of findings. Without independent data validation, any discoveries made in the study may be discredited [21].

It is essential to consider that epigenomic the study can reveal cellular heterogeneity in cell populations with homogenous morphology. This heterogeneity, often due to variations in gene expression or responses to stimuli, can be observed in the context of diseases such as cancer. Frequently, the expression heterogeneity of phenotypically relevant genes is associated with cellular heterogeneity. However, bulk-cell epigenomic methods provide an average profile of histone modifications across many cells and lack the resolution necessary to identify heterogeneity within a population [22].

Considering all challenges from each molecular network construction that can participate in network medicine, some recommendation excite that can improve these molecular networks applications in network medicine (Table 1).

| Recommendation | Description |

| Multilayer network concept | Multilayer networks integrate various types of connections, enabling different forms of interactions between the same set of entities. The integration of non-coding RNAs networks with Protein-Protein Interaction networks using the multilayer concept can significantly improve the predictive power of network medicine. |

| Feeding fresh data | New techniques, tools or methods can uncover new doors leading to deeper knowledge in the field. Network medicine requires frequent data collection abilities using highly sensitive tools to identify and quantify molecules’ concentrations, fluxes, and interactions accurately. |

| Experimental validation | Experimental validation is crucial for the development of network medicine and its application in precision medicine. For example, single cell RNA sequencing shows great potential in network medicine and can be used to analyze pathways, biomarkers, and drug targets in different diseases. |

For a long time, network science primarily focused on systems where all components were treated equally, without accounting for the temporal or contextual aspects of interactions. However, with improved resolution in real datasets, researchers have started recognizing the multiplex nature of real-world systems, as well as the significance of their time-varying and multilayer characteristics. Multilayer networks capture multiple channels of connectivity, allowing for various types of interactions between the same entities. These networks are particularly valuable for studying complex systems that consist of multiple subsystems and layers of connectivity, which are often open, directed, multilevel, and dynamic. The success of complex network theory is reflected in its wide-ranging applications, particularly in biomedicine, where it has made important contributions to understanding real-world challenges [29].

Integrating non-coding RNA (ncRNA) networks with Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks using the multilayer approach can significantly enhance the predictive power of network medicine. This was highlighted in recent research by Gysi and Barabasi [30], who demonstrated that incorporating ncRNAs into PPI networks improves the accuracy of disease module identification and the ability to uncover disease-disease relationships. Including ncRNAs enhances the prediction of comorbidities across various diseases, indicating that non-coding elements play a crucial role in most disease mechanisms. This also presents opportunities for discovering novel drug targets that are more closely aligned with the disease module. The systematic inclusion of non-coding elements offers a deeper understanding of disease progression and may pave the way for advances in precision medicine [31].

In contrast, Zhou et al. [32] show strong associations between symptom similarities in diseases and shared genes or PPIs. They also highlight a clear link between the diversity of clinical symptoms and underlying cellular mechanisms. For example, despite the distinct pathological characteristics of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), both may present common symptoms and share significant genes [33]. But there is differences in miRNA profile in these diseases that missing in this relationship correlation [34]. Maybe this is the reason that make these two inflammatory bowel diseases different from each other and their different response to drug [35] or their risk to surgery that demonstrate their progression [25].

Disease progression is a critical focus in medical research that demands substantial attention. Chronic conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), progress slowly, making it challenging to capture their full trajectory through short-term data collection. In some cases, the progression rate is non-linear, necessitating more rigorous data collection strategies to accurately reflect the progression profile [26].

The multilayer concept can improve the detection of disease progression. For instance, modeling the PPI network of bladder cancer while considering grading in non-invasive bladder cancer [36] yielded different results from modeling without grading [37]. This implies that considering several layers of data can provide more accurate insights into progression, which can help clinicians make more informed decisions. Additionally, developing disease progression models that incorporate more physiological inputs and data from larger populations can enhance the accuracy of data collection. This, in turn, can help researchers gain a deeper understanding of the disease [26].

Science is an ongoing quest for truth, with each representation of reality offering only a partial glimpse of the whole. As science advances, more sophisticated techniques and technologies replace older methods, driving the development of deeper understanding and more accurate representations. Achieving this progress depends on the delicate balance between technological advancements and a clear, guiding vision [38].

In the realm of biological sciences, recent technological innovations have dramatically enhanced our ability to study complex biological systems. A key aspect of these advances is the ability to collect fresh, high-quality data that provide insights into the intricate web of interactions in living organisms. For example, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized the study of molecular networks by enabling comprehensive analyses of DNA, RNA, and epigenetic modifications at an unprecedented scale. NGS has facilitated large-scale gene expression profiling, variant detection, and transcriptional regulatory network inference, making it a cornerstone technology for systems biology [27].

Another powerful tool in this context is single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), which allows researchers to study gene expression at the resolution of individual cells. This technique has opened up new avenues for understanding cellular heterogeneity and mapping gene regulatory networks in complex tissues, particularly in cancer research and developmental biology [28]. The data generated from scRNA-seq are crucial for feeding into network models to uncover how cellular interactions contribute to disease progression.

A recent development in this field is the rise of spatial transcriptomics, which integrates transcriptomic data with spatial information, allowing researchers to study how gene expression varies across different regions of tissue. This technique is particularly valuable for understanding how cells interact within their native environments, adding a new dimension to network study [39].

Network medicine as a new era in medicine science despite significant advancements, is still in its infancy, and a significant progress is expected in different areas in the future. These include developing new theoretical approaches and methods to characterize network topology and understanding the dynamics of motif clusters and their biological functions. To move meaningfully beyond current knowledge, better data collection abilities are required, which will require developing highly sensitive tools to identify and quantify molecules’ concentrations, fluxes, and interactions accurately [3].

Experimental validation is not only a basic requirement but a cornerstone in the development of network medicine, playing a pivotal role in translating theoretical models into practical, clinically actionable insights for precision medicine. While network medicine has made significant strides, with many principles supported by experimental data, the complexity and heterogeneity of biological systems demand continuous refinement and validation to ensure the reliability of these models [40].

One key approach for validating network models is single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), which has proven instrumental in unraveling cell-specific gene expression patterns, uncovering novel biomarkers, and identifying drug targets. For instance, scRNA-seq was utilized in a study on liver cancer, revealing the different molecular pathways active in tumor subpopulations and pinpointing potential therapeutic targets that could not be identified through bulk analysis [41]. By offering a high-resolution view of cellular heterogeneity, scRNA-seq contributes to building more accurate network models and provides experimental evidence for the involvement of distinct cell types in disease pathogenesis.

Moreover, mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics is another crucial experimental validation tool in network medicine, enabling the identification of protein-protein interactions and post-translational modifications that play critical roles in signaling networks. For example, MS has been used to validate the key nodes in cancer signaling networks, such as those involved in drug resistance mechanisms, further reinforcing the utility of network models in precision oncology [15, 42, 43].

Beyond transcriptomics and proteomics, the use of multicellular disease models (MCDMs) provides an avenue for validating network predictions at the tissue level. MCDMs simulate the interactions between different cell types within the disease microenvironment, allowing researchers to experimentally assess the centrality of cell types and prioritize genes based on their network roles. This approach has been used to model diseases such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, where complex intercellular communication plays a vital role in disease progression [44]. MCDMs also allow for testing the effects of therapeutic interventions on multiple cell types simultaneously, providing a more comprehensive validation of network predictions compared to single-cell or single-molecule assays.

Gene knockdown and CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing are also valuable methods for experimentally validating predicted network hubs and critical nodes in disease-related pathways. These techniques enable the functional testing of genes identified as central players in disease networks, allowing researchers to observe the phenotypic consequences of gene disruption and assess their potential as therapeutic targets [12].

Therefore, experimental validation is not merely a rudimentary concept but an essential and evolving process in network medicine. It is the linchpin that ensures the accuracy of network models and their applicability to precision medicine. As these technologies advance, the integration of multi-omics data, including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, into network models will enhance their predictive power, driving more precise diagnostics and therapeutic interventions.

Network medicine provides an innovative approach to understanding complex relationships between diseases and their underlying molecular mechanisms. Non-coding elements, such as ncRNAs, have been demonstrated to play an essential role in disease progression and comorbidity prediction. Incorporating these elements into PPI networks can lead to the identification of more effective drug targets and more precise disease modules. However, experimental validation and continued technological advancements are imperative to ensure the accuracy and validity of network models used in precision medicine.

The multilayer concept and techniques, such as scRNA seq, have demonstrated the potential to unlock new doors in the field of network medicine. By combining diverse layers of data, researchers can gain deeper insights into disease progression and cell types associated with disease. However, there is still much to be done to develop highly sensitive tools to accurately identify and quantify molecules’ concentrations, fluxes, and interactions. Overall, network medicine holds great promise for advancing our understanding of complex interactions in disease and developing more targeted, personalized treatments.

SZ and SS contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SZ and both authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGpt to check spelling and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.