Frontiers in Bioscience-Scholar (FBS) is published by IMR Press from Volume 13 Issue 1 (2021). Previous articles were published by another publisher on a subscription basis, and they are hosted by IMR Press on imrpress.com as a courtesy and upon agreement with Frontiers in Bioscience.

1 Laboratorio de Neuroproteccion, Facultad de Farmacia, Universidad Autonoma del Estado de Morelos, Av. Universidad 1001, Col. Chamilpa, Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico

2 Departamento de Neuroquimica, Instituto Nacional de Neurologia y Neurocirugia, M.V.S., Av. Insurgentes Sur 3877, La Fama, Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico

3 Laboratorio de Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas, Instituto Nacional de Neurologia y Neurocirugia, M.V.S., Av. Insurgentes Sur 3877, La Fama, Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico

4 Laboratorio de Fitoquimica, UBIPRO, Facultad de Estudios Superiores-Iztacala, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Av. De los Barrios 1, Col. Los Reyes Ixtacala, Tlanepantla, Edo. de Mexico, Mexico

Abstract

Parkinson’s disease is considered to be due to an increase in the catabolism of dopamine by the action of monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzymes which leads to an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and loss of dopaminergic neurons. Here, in a model of neurotoxicity inducible by 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), we tested the effect of hydroxytyrosol (HTy), a potent antioxidant, on generation of ROS. Five minutes after a single intravenous administration of 1.5 mg/Kg of Hty, Wistar rats received an intrastriatal micro-injection of 10 micrograms of MPP+ while control animals received saline solution. Six days later, all animals were treated with apomorphine (1 mg/Kg), subcutaneously and ipsilateral rotations were assessed within an hour. Then, the rats were sacrificed, striatal tissues were removed and their catecholamines and MAO-A and B activities were quantitated. Pretreatment with HTy significantly diminished the number of ipsilateral rotations. This recovery correlated with significant preservation of striatal dopamine and significant inhibition of of the MAO activity. These results are consistent with the inhibitory effect of HTy on the MAO isoforms and form a basis for the neuroprotective mechanism of this phenylpropanoid in MPP+ induced Parkinson’s disease.

Keywords

- Hydroxytyrosol

- MPP+

- Parkinson's disease

- Monoamine oxidase

- Neuroprotection

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a chronic, progressive and complex neurodegenerative disorder. After Alzheimer´s disease, PD is the second most common neurological disease which after age 65, affects 1% of the population World-wide (1). PD is characterized by degeneration of the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) with a decrease in the level of striatal dopamine (DA) (2). There is still no effective pharmacological treatment for reversing or halting the progress of the neurodegeneration.

In support of an environmental cause of the disease, organic molecules such as MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) and its metabolite MPP+ (1-methyl-4-phenylpyridine) have been shown to cause the degeneration of nigroestriatal dopaminergic neurons with extreme specificity (3). An alternative hypothesis posits that the disease is caused by loss of dopaminergic neurons by the increase in the catabolism of DA, producing endogenous neurotoxins, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) that, by virtue of generation of free radicals, damage dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway (4-5). ROS can be generated from DA, preferentially by the type B of monoamine oxidase (MAO), a main intracellular catabolic enzyme for dopamine in the SNc (6). The neuronal and extra-neuronal sources of MAO B have been shown to be elevated in PD (7). For this reason, the current clinical therapies of PD are based on the use of MAO-B inhibitors, that have traditionally been derived from natural resources. These include selegiline (deprenil) and rasagiline, drugs that exhibit potent neuroprotective effects in vitro and in vivo (8-9). By molecular docking technique as well as by vitro and in vivo experiments, it has been shown that flavonoids, xanthones, tannins, proanthocyanidins, iridoid glucosides, curcumin, alkaloids and cannabinoids, all exert inhibitory activity on MAO-B. These natural compounds have a half maximal Inhibitory concentration 50 (IC50), higher for the MAO-B (0.8-154 μM) than MAO-A (37.6-800 μM) isoform (10). One model of PD is inducible in mice by the neurotoxin, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP). Using this model, the neuroprotective efficacy of polyphenolic compounds, such as curcumin and its metabolite tetrahydrocurcumin has been attributed to its action on MAO-B (11).

In models of oxidative stress in rodents, the neuroprotective effect of the methanolic extract of Buddleja cordata and extra virgin olive oil have all been attributed to the antioxidant property of 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl ethanol known as hydoxytyrosol (HTy), or polyphenols that exist in these sources (12-13). HTy is a phenylpropanoid found in diverse vegetable species, either in an isolated form or chemically bound through ester bonds to sugars, forming acteoside, verbascoside and oleuropein compounds (12-13). Several in vitro studies including neuronal cells exposed to H2O2 or ferrous salts and sodium nitroprusside have demonstrated that the HTy is a potent antioxidant (14-16). This compound is rapidly absorbed in animals and humans when administrated by the oral route (17-19). HTy has been shown to be neuroprotective both in hypoxia-reoxygenation and Huntington's disease animal models (20-21). At a dose of 2.5 mg/Kg administered for 14 days, the toxic effect of 3-nitropropionic acid was preventable in rats by the antioxidant effect of HTy on striatal tissues (21). This treatment also led to a significant decrease of the lipid peroxide levels and an increase of the reduced glutathione (GSH) (21). An in vitro study using mitochondria from rat brain tissue showed that the HTy is a potent inhibitor of MAO-B with an IC50 of 16.3 μM (22).

Given that there has been no in vivo experimental evidence for the neuroprotective effect of HTy, in the present study, the effect of HTy on MAO isoforms, were characterized in the rat brain striatum in a rat MPP+ oxidative model of PD. We also assessed the behavioral impact and catecholamines levels and identified the IC50 of MAO-A and B in vitro in cells that were derived from the same brain region.

Experiments were performed using male NIH strain Wistar rats (220–250 g). Animals were maintained under standard conditions (12:12 light–dark cycles, 23 ± 2℃ and 40% relative humidity). They were fed standard (Purina™) chow diet and were provided free access to water. All animals were treated humanely to minimize discomfort in accordance with the ethical principles and regulations specified by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery and the standards of the National Institutes of Health of Mexico.

Animals were pretreated with HTy before MPP+ administration. Animals were randomly allocated to either one of the following experimental groups (n=5-7): Control Group (C), rats treated with saline solution (1 mL, i.v.) and 8 μL of 0.6% intrastriatal saline solution. The HTy experimental animals received HTy (1.5 mg/Kg, i.v.) and 8 μL of 0.6% intrastriatal saline solution. The MPP+ group (MPP+), animals were treated with saline solution (1.5 mg/Kg i.v.) and MPP+ (10 μg/8 μL saline solution). In the HTy + MPP+ group, rats were administered with HTy (1.5 mg/Kg i.v.) plus MPP+ (10 μg/8 μL saline solution). HTy was dissolved in saline solution and a single intravenous dose (1.5 mg/Kg) (18) was administered five minutes before intrastriatal MPP+ stereotaxic injection. The 3-hydroxytyrosol was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (México).

All animals were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine combination (50 mg/Kg/4 mg/Kg, intraperitoneally). After 15 minutes, a single intravenous dose of HTy or saline solution was administered to animals. Five minutes later, rats were infused for 5 min with a single intrastriatal stereotaxic microinjection of 10 μg of MPP+ dissolved in 8 μL of sterile saline and were injected at the stereotaxic coordinates: 0.5 mm anterior to bregma, -3.0 mm lateral to bregma and -4.5 mm ventral to the dura in the right striatum (23). The control animals were administered with 8 μL of saline solution. All rats were killed by decapitation at different times after MPP+ administration and the striatum of the right hemisphere was dissected out and stored at -70ºC until the performance of neurochemical measurements.

Six days after the intrastriatal MPP+ injection, animals of the four experimental groups were treated subcutaneously with apomorphine at a dose of 1 mg/kg. Rats were placed individually in rectangular acrylic boxes for 1 h to count ipsilateral rotations. The results are expressed as the total number of ipsilateral rotations over a 1-hour period (turns/h) (24).

Striatal DA, DOPAC (3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacatic acid) and HVA (Homovanillic acid) contents were assessed by HPLC coupled to electrochemical detection (25). Seven days after the MPP+ injection, the striatum was dissected out and sonicated into a perchloric acid-sodium metabisulfite solution (1 M, 0.1 % w/v). The homogenate was centrifuged at 14,000 x g for 10 min at 4ºC and the supernatant was analyzed. Data were collected and processed by interpolation into a standard curve. The results are expressed as µg of catecholamine per gram of wet tissue weight.

Activites of striatal MAO were assayed in vivo and in vitro using a method described by Morinan and Garratt (26). Corpora striata from animals with experimental treatments (in vivo experiments) or without any previous treatment (in vitro experiments) were homogenized in 2.5 mL of phosphate buffer. Three aliquots of 250 µL were removed from the diluted homogenates. 250 µL of phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) was added to two of the aliquots. To the third aliquot, 250 µL of 4 μM deprenyl (MAO-B inhibitor) or 4 μM clorgyline (MAO-A inhibitor) was added. After incubation at 37°C for 10 min, aliquots were added to 500 µL of kynuramine (50 µM, MAO substrate) and the reaction was stopped by adding 1 mL of 10% w/v trichloroacetic acid only to one aliquot. Then, following an additional incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the reactions were stopped by adding 1 mL of 10% w/v trichloroacetic acid to the second and third aliquot. After cooling and centrifugation (12,000 rpm, 10 min), an aliquot of 1 mL of the supernatant was added to 1 mL of 1 N aqueous NaOH. Fluorescence was then measured at 315 nm excitation and 380 nm emission using a Perkin-Elmer LS50B Luminescence spectrophotometer. In each experiment, calibration curves were constructed by measuring the fluorescence intensity of 4-hydroxyquinoline (4-HOQ) standards. 4-HOQ is the product of MAO activity on kynuramine. MAO activity was expressed as nmol of 4-HOQ formed/1 h incubation per g of tissue wet weight. Specific MAO inhibitor (deprenyl or clorgyline) were used to measure these MAO isoforms. The IC50 of HTy for both MAO isoforms were calculated with inhibition curves from the in vitro assay.

The experimental behavioral assessment data were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by multiple comparisons using the Mann-Whitney U-test. The results of the striatal catecholamines content and MAO activities were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by a Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 software.Values of P < 0.05 were considered to be of statistical significance.

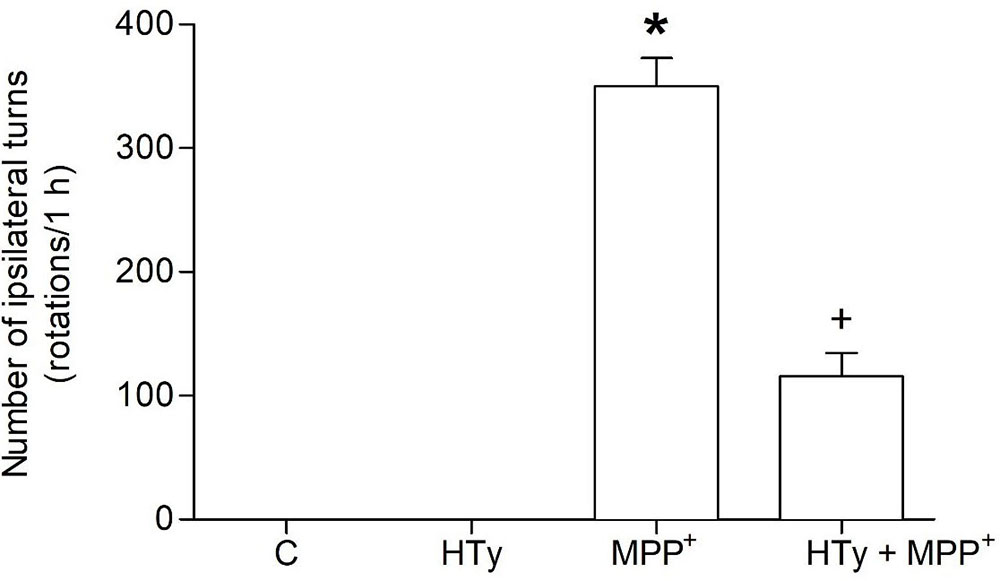

Behavioral assessment was carried out to evaluate the neuroprotective effect of the intravenous pretreatment with HTy (1.5 mg/kg) against long-term MPP+-induced neurotoxic effect. As compared to the C or HTy-alone groups, MPP+ administration produced a marked increase on circling behavior (350 ± 22 rotations/h) after apomorphine administration (see Figure 1). The HTy pretreatment significantly prevented (p = 0.004) the effect of apomorphine-induced circling-behavior in the animals that received MPP+ (HTy + MPP+ group). The number of ipsilateral turns was reduced by 65 % (123 ± 15 rotations/h), when compared against rats that were treated only with the neurotoxin (MPP+ group).

Figure 1

Figure 1Effect of hydroxytyrosol on apomorphine-induced rotations in the rat MPP+ model. Rats were pretreated with HT (1.5 mg/kg), fifteen minutes after, were infused with MPP+ and six days later, the animals were treated with apomorphine and ipsilateral rotations were recorded for 1 h. C, control; HT, hydroxytyrosol; MPP+, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium; HT + MPP+. Data are the mean ± SEM. n = 7 rats per group. *Statistically different versus all other groups. +Statistically different versus MPP+ group. P < 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Mann-Whitney’s U-test.

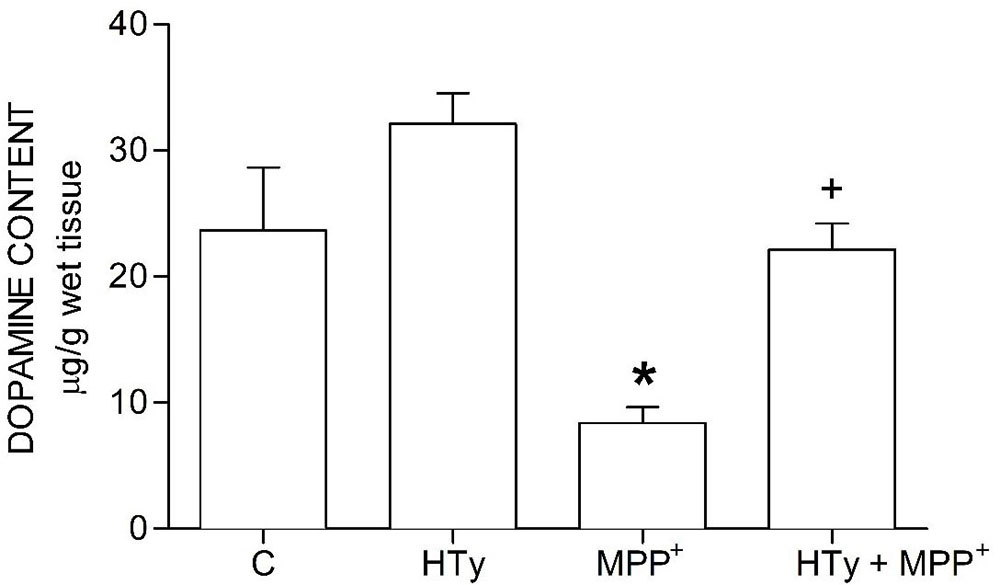

The neuroprotective effect of HTy reducde MPP+-induced striatal dopamine depletion (Figure 2). HTy, administered at 1.5 mg/kg to control rats did cause any change in dopamine content (29.58 ± 1.5 µg/g wet tissue), as compared to the values of the control group (23.66 ± 4.9 µg/g wet tissue). However, animals that were treated with MPP+ showed a significant reduction (70 %) (8.31 ± 1.2 µg/g wet tissue) of striatal dopamine (p = 0.001), as compared to control values. Administration of HTy to MPP+-infused rats (HTy + MPP+ group) fully restored dopamine values to the levels that were observedin the control group (20.27 ± 1.9 µg/g wet tissue) (P=0.007, vs MPP+ group). After treatment with HTy, the striatal dopamine content was 45 % higher than the values obtaomed in the MPP+-only group.

Figure 2

Figure 2Effect of hydroxytyrosol on striatal dopamine content in a rat MPP+ model. C, control; HT, hydroxytyrosol; MPP+, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium; HT + MPP+. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM for n = 7 rats per group. *Statistically different from all other groups. +Statistically different from MPP+ group and HT group. P< 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test.

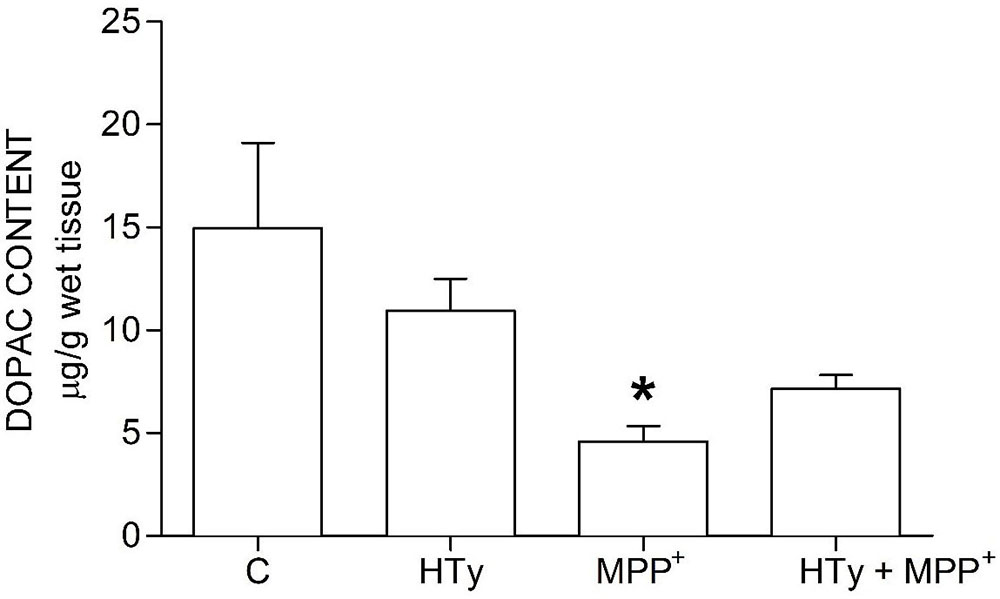

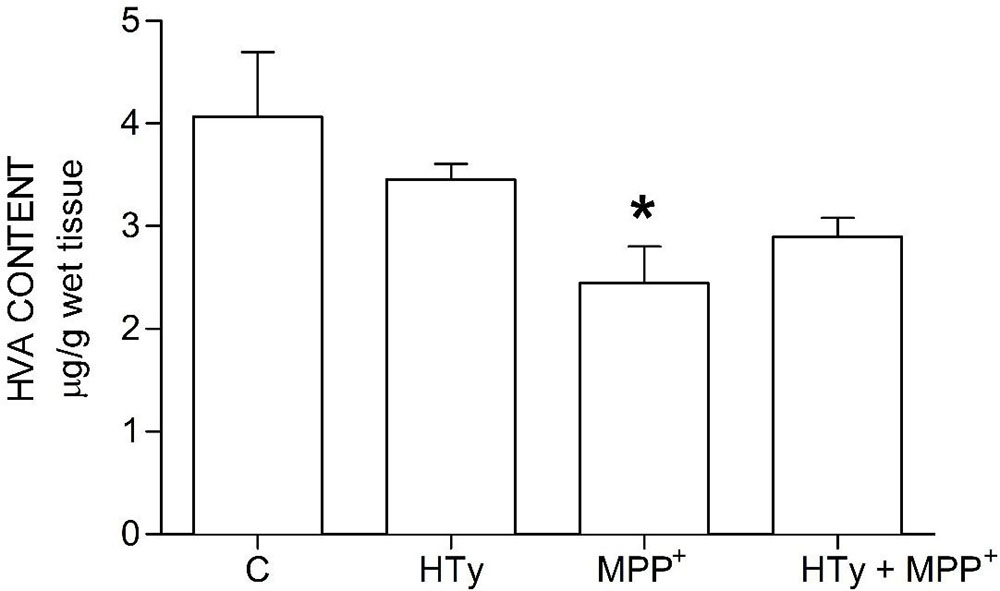

Animals injected with MPP+ (M group) showed a statistically significant decrease (p < 0.05) of striatal DOPAC as compared to the control group (C) (-70%) and hydroxytyrosol group (HTy group) (-50%) (Figure 3). Rats pretreated with hydroxytyrosol plus MPP+ (HTy + MPP+ group) also significantly maintained (p < 0.05) striatal DOPAC levels (-30%) as compared to the control group (C) values. In contradistinction, striatal HVA levels decreased (p < 0.05) by MPP+ administration (Figure 4), as compared to HTy group. However, the HTy pre-treatment did not prevent this effect, and striatal HVA levels were similar to those of the HTy + MPP+ group.

Figure 3

Figure 3Hydroxytyrosol pretreatment effect on DOPAC levels in the MPP+ model in rat. This chart illustrates DOPAC levels detected in the right striatum of each treatment group; C, control group; HT, Hydroxytyrosol group; MPP+, 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine group; HT + MPP+ group. Data are the mean ± SEM, n = 7 rats per group. *Statistically different from Control group. P< 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test.

Figure 4

Figure 4Hydroxytyrosol pretreatment effect on HVA levels in the MPP+ model in rat. This chart illustrates HVA levels detected in the right striatum of each treatment group; C, control group; HT, hydroxytyrosol group; MPP+, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine group; HT + MPP+ group. Data are the mean ± SEM, n = 7 rats per group. *Statistically different from HT group. P< 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test.

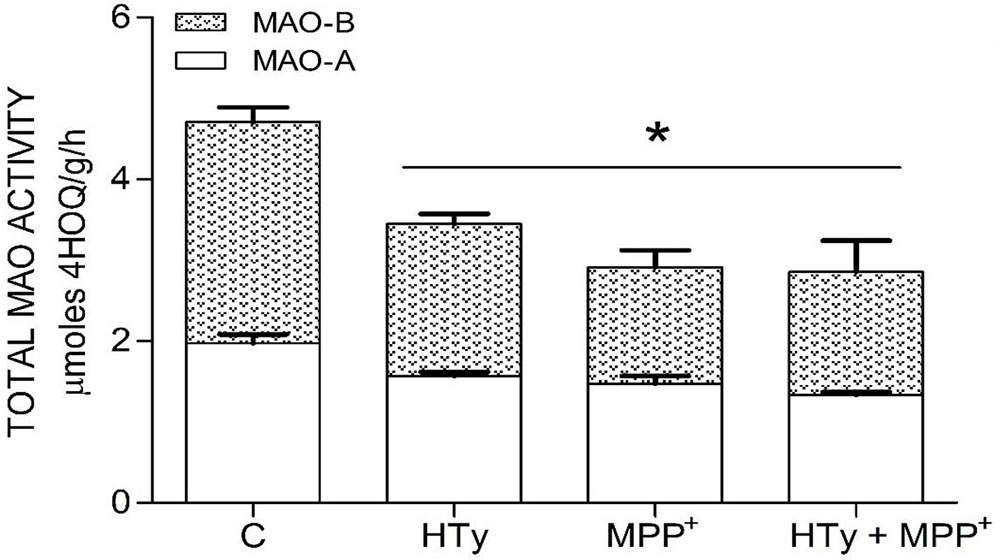

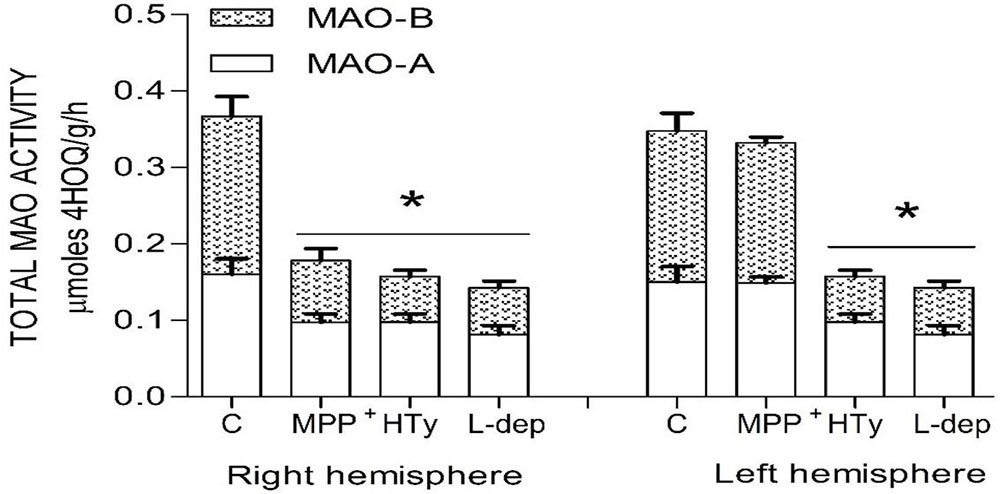

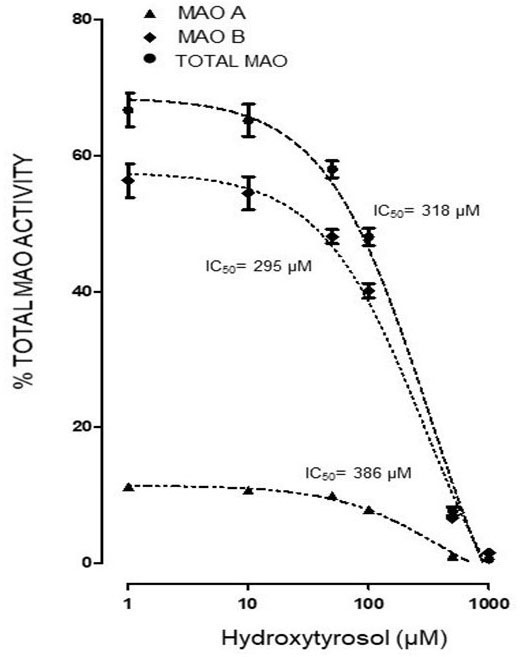

Both the administration of HTy (-30%) and intra-striatal administration of MPP+ (-38%) significantly decreased MAO activity (p<0.05), as compared to control group values (Figure 5). While, pretreatment with HTy led to a 40% reduction in the total activity of the MAO when animals were treated with HTy plus MPP+ (2.87 μmoles 4HOQ/g/h). This inhibition was significant (p<0.05) when compared to the values obtained in the control group (4.71 μmoles 4HOQ/g h). Meanwhile, MAO activity in the contralateral hemisphere (left hemisphere) of the same animal that was not treated MPP+, showed no change in the level of either MAO isoforms (Figure 6). While MAO-B isoform activity was reduced by 70%, both the systemic administration (i.v.) of HTy or L-deprenyl (1 mg/Kg, i.p.) produced a significant inhibition (p<0.05) of MAO-A isoform by 40% and 50%, respectively. The inhibitory effect of HTy on MAO isoforms was quantitated by in vitro kinetic studies with rat striatal tissue (animals without any chemical treatment). These analyses showed the inhibitory concentration of the HTy to be 50 (IC50) of 386 μM for isoform A and 295 μM for B (Figure 7).

Figure 5

Figure 5Inhibitor Effect of hydroxytyrosol on MAO isoforms in the striatum of rats administrated with MPP+. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of 7 animals per group. C, control; HT, hydroxytyrosol (1.5 mg/Kg); MPP+, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion (10 μg/8 μL S.S.); HT + MPP+. *Statistically different from the control group. P< 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test.

Figure 6

Figure 6Total MAO activity in both rat brain striatum 2 h after a single ipsilateral striatum injection of MPP+ or treatment with hydroxytyrosol or L-deprenyl. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of 5 animals per group. C, control group; MPP+, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion (10 μg/8 μL S.S.); HT, hydroxytyrosol (1.5 mg/Kg, i.v.). L-DEP, L-deprenyl (2 mg/Kg i.p.). *Statistically different from The control group. P< 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test.

Figure 7

Figure 7In vitro determination of half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of HT on MAO isoforms of rat striatum. Each value represents the mean ± ES of 3-5 assays. One hundred twenty five µL of rat striatum homogenate (Without pharmacological treatment) were incubated with 125 µL of TH (1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 µM) and 4 µM deprenyl as MAO-B specific inhibitor. ●IC50 318, ▲386, ♦295

The results of the present study provide the first direct in vivo evidence of inhibition of MAO isoforms and neuroprotective effect of HTy in the MPP+ model of Parkinson's disease in rats. Recently, in a model of oxidative stress induced by MPP+ in rats, our group demonstrated the neuroprotective and antioxidant effects of the methanolic extract of the Buddleja cordata plant that has a significant amounts of HTy (12). The HTy of B. cordata is chemically bound through ester bonds to sugars, that form a verbascoside or acteoside (23%, methanolic extract) (12). The oral administration of this natural extract generates bioavailable HTy from verbascoside under conditions of acidic pH exists in stomach. This form of the HTy is subsequentaly activated by microbial esterases in the intestine (27). High absorption of this extract easily allows the metabolite to enter the bloodstream and pass the Blood-Brain-Barrier (BBB) to enter the brain (28-29). The neuroprotective effect of the methanolic extract dervied from B. cordata is likely attributable to HTy, rather than to the phenolic compound that was identified chromatographically in striatal tissue from rats pretreated with the methanolic extract (12).

Using a model of hypoxia-reoxygenation in rats, the neuroprotective effect of HTy has also been reported after administration of either 0.25 or 0.5 mL/Kg of olive oil extract for 30 days or 5 or 10 mg/kg for 7 days (20, 30). The neuroprotective effect of HTy has also been demonstrated in a rat model of Huntington's disease by an oral administration of 2.5mg / kg for 14 days (21). This treatment also reduced striatal lipid peroxide formation by 58.5%, and of GSH by 39%. In nitroprusside-induced oxidative stress, extracts that allowed administration of HTy at a dose of 100 mg/kg for 12 days decreased lipid peroxidation (MDA) by 95%. In addition, HTy (24 μM) reduced the cytotoxicity of pro-oxidants on brain cells (DBC) by 40-50% and significantly decreased the cytotoxicity induced by both stressors, as measured by the preservation of mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP levels (31). It has been previously shown, that 5 minutes after an intravenous administration of 1.5 mg/Kg of or after intra-peritoneal injection of 20 and 40 mg/Kg or after intraperitoneal injection of 20 and 40 mg/Kg, 14C labeled HTy can easily pass the BBB (18, 29). In the present study, an intravenous dose of 1.5 mg / Kg of HTy, prior to the injection of the MPP+, led to a decrease in the ipsilateral rotations (70%) and the preservation of striatal dopamine levels (78%).

The biological effects of HTy have been attributed to its ability to donate electrons from the hydroxyl groups in the ortho position and the subsequent formation of stable intramolecular hydrogen bridges with the phenoxylic radicals, as well as the catechol ring of its chemical structure that favors a metal-chelating effect (32-35). As shown in the present study, additional mode of action for HTy involves an inhibitory effect that HTy exerts on enzymes which are involved in the catabolism of catecholamines, specifically MAO-B. Catabolism of dopamine by the action of MAO produces hydrogen peroxide as a by-product, that in turn, may serve as a substrate for production of the cytotoxic hydroxyl radical by Fenton`s chemistry (36). As HTy inhibits MAO at similar concentrations as those employed in the present study, this action may be important in reducing formation of hydroxyl radicals in vivo. As has been reported for other polyphenolic compounds derived from vegetable species, the preservation of the dopamine levels by HTy, might be due to its inhibitory effect on MAO isoforms, mainly MAO-B (12). This enzymatic inhibition suggests a decrease in the catabolism of DA, as well as a decreased generation of ROS (5). Clinical studies have reported an increase in the oxidation of DA by MAO-B in the brain of patients with Parkinson's disease and such an effect might lead to the inhibition of both the exogenous neurotoxins such as MPP+ as well as endogenous neurotoxins such as H2O2 (14). Studies using isolated mitochondria from rat brain tissue have confirmed the inhibitory effect of HTy on MAO-B, reporting an IC50 of 16.3 μM, a level which is 11.9 times lower than the IC50 that was obtained in this study (194 μM).

In conclusion, we demonstrated that, at the same dose, HTy inhibits striatal MPP+ neurotoxicity and exerts neuroprotective effect on both isoforms of MAO. Given that the adult human brain has high levels of MAO-B protein, these findings suggest that natural substrates thtat contain a high level of HTy should protect the degeneration of the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) in PD (37).

This project has been supported partially by SEP/ CONACYT 257092. Pérez-Barrón is grateful to CONACYT for the scholarship grants (349836).

HT

Hydroxytyrosol

1-Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium

Parkinson disease

1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

Monoamine oxidase

Monoamine oxidase A

Monoamine oxidase B

Dopamine

3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacatic acid

Homovanillic acid

Glutathione