1 Research Institute of Innovative Medical Science and Department of Medical Chemistry and Biochemistry, Medical Faculty, Medical University-Sofia, 1431 Sofia, Bulgaria

2 Department of Pharmacology, Pharmacotherapy and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical University-Sofia, 1000 Sofia, Bulgaria

Abstract

Despite the enormous theoretical progress, there is currently no effective treatment for the cytokine storm (CS) in COVID-19 and Influenza, which is due to hyperactivation of NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome (NLRP3-I). According to our research, the only way to prevent or interrupt the CS is to administer high but safe doses of colchicine, which inhibits NLRP3-I/CS.

Keywords

- COVID-19

- influenza

- NLRP3 inflammasome

- cytokine storm

- colchicine doses

- colchicine toxicity

Over 5.2 million publications, clinical cases, and tens of thousands of preclinical and/or randomized clinical trials, observational studies, small randomized non-controlled trials, and retrospective cohort studies are trying to solve the problem of preventing and treating COVID-19. Over 700 medications are proposed with anti-SARS-CoV-2 effect [1], but they cannot solve the problem of prophylaxis, effectively treating the disease, and preventing post-COVID-19 symptoms [2]. In our opinion, at the moment, the only drug that can interrupt COVID-19 cytokine storm (CS) by inhibiting the NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome (NLRP3-I) is colchicine.

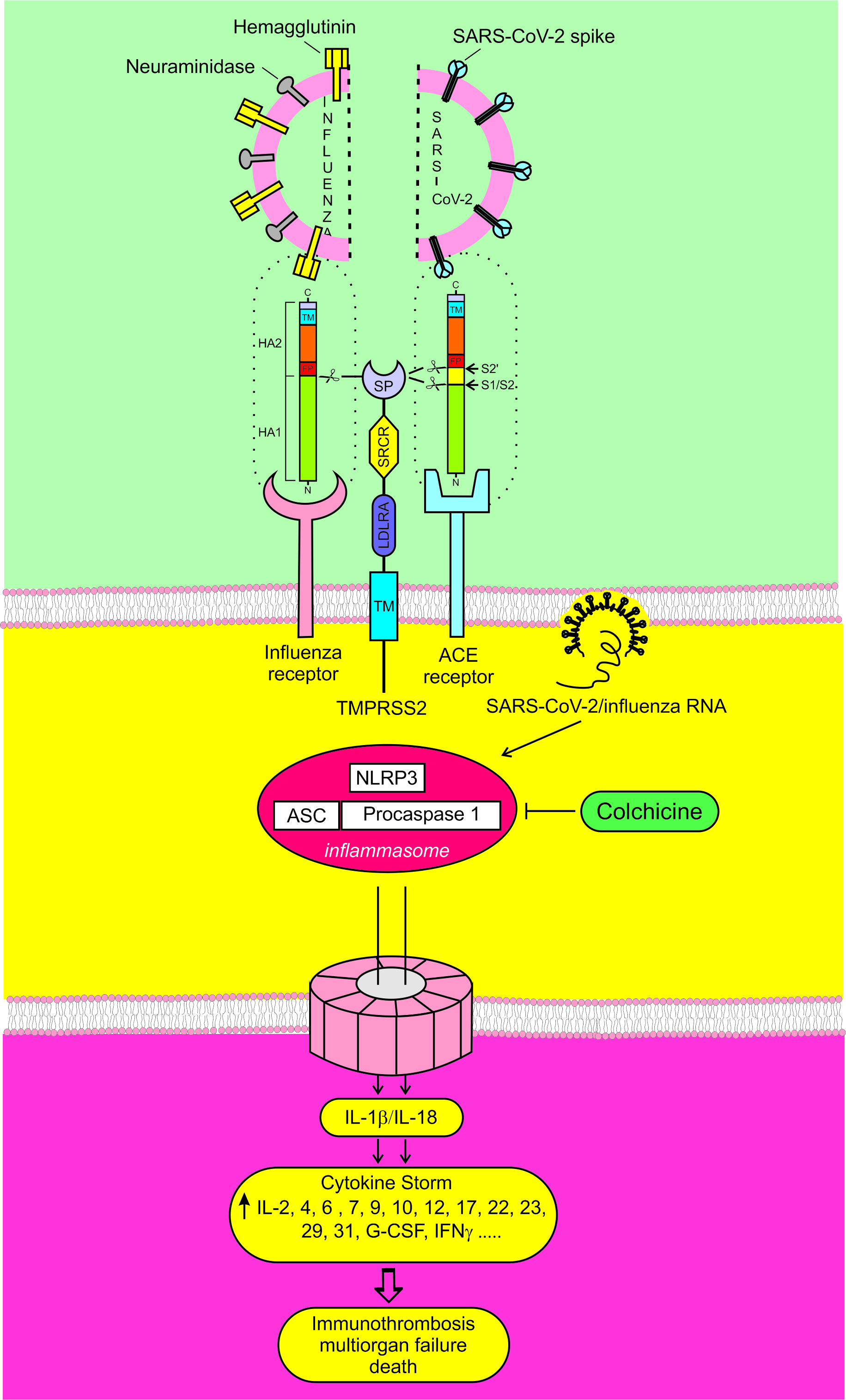

There are three main battlefields in the fight against COVID-19 (Fig. 1). The first is at the cell plasma membrane, where the primary goal is to stop SARS-CoV-2 before it can enter the host cell. At this stage, vaccines and artificial monoclonal antibodies have been used to neutralize SARS-CoV-2, and Transmembrane Protease Serine S1 subtype 2 (TMPRSS2) inhibitors to block its passage through the plasma membrane. If the virus succeeds in bypassing this barrier, the second battlefield is inside the cell. In this scenario, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends three viral replication inhibitors. Yet, the challenge is not only to halt viral replication but also to neutralize the hyperactivated NLRP3-I, which is the cause of the CS and is closely associated with the coagulopathy seen in severe COVID-19 cases [3, 4]. The third battlefield lies outside the infected cells, where the focus turns to controlling the systemic consequences of NLRP3-I hyperactivation, namely hypercytokinemia and microthrombosis. For this, WHO recommends antibodies against interleukin receptors and a Janus kinase 1/2 (JAK1/2) inhibitor.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The three main battlefields in the fight against COVID-19. To enter the cell, the hemagglutinin of the influenza virus and the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 must be cut by a protease. TMPRSS2 is the major hemagglutinin and spike protein-activating protease. Influenza and SARS-CoV-2 viruses can directly or indirectly activate NLRP3-I. If hyperactivated, NLRP3-I can cause CS, multi-organ failure, and death. TMPRSS2, Transmembrane Protease Serine S1 subtype 2; NLRP3-I, NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome; CS, cytokine storm.

If the first battle is won, there will be no second or third. If viral replication is neutralized, it remains uncertain whether the hyperactivated NLRP3-I will, in turn, be inhibited, as there is no direct link between these processes [5, 6, 7]. Only by neutralizing NLRP3-I hyperactivation can phase 3 be prevented. The battle in phase 3 becomes largely futile due to hyperactive NLRP3-I, which continuously generates newer and newer cytokines [8].

Our therapeutic strategy is based on the preventive inhibition of the virus entry into the cell with the TMPRSS2 inhibitor bromhexine (BRH) and the inhibition of NLRP3-I with higher doses of colchicine [8, 9, 10].

The main cause of life-threatening complications in COVID-19 is the hyperactivation of NLRP3-I, causing CS. The CS may lead to real disasters as Sepsis, Respiratory failure (ARDS, Pneumonia, Hyaluronan storm), Heart failure (Acute cardiac injury, Arrhythmias, Heart inflammation, Venous thromboembolism), Septic shock, Immunothrombosis, Acute kidney injury, Secondary infection, Liver injury (elevated liver enzymes), Neurologic manifestations (seizure, stroke, encephalitis, and Guillain–Barré syndrome (which includes loss of motor functions) etc. [11, 12, 13].

Therefore, controlling the hyperactive NLRP3-I should be the primary therapeutic goal in severe COVID-19. When the NLRP3-I is blocked promptly, the need for antivirals, anticoagulants, cytokine blockers, or JAK1/2 inhibitors becomes reduced or even eliminated [2, 10]. Furthermore, if prolonged prophylaxis with the TMPRSS2 inhibitor BRH is carried out, inhibiting viral replication and NLRP3-I might become unnecessary altogether [2].

Interestingly, the mechanisms of penetration and complications in COVID-19 and Influenza are analogous (Fig. 1) [2].

There is strong evidence for a common immunopathogenic mechanism linking hyperactivated NLRP3-I, leading to CS and organ failure in influenza coronavirus infections responsible for past epidemics and pandemics. For example, the highly pathogenic avian H5N1 virus Vietnam/1203/04 causes increased levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-

In Influenza A asymptomatic subjects, both NLRP3-I and the IL-1

Thus, a wide range of viruses can activate NLRP3-I, including Influenza, SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV, Parainfluenza, Adenovirus, Bocavirus, Metapneumovirus, Respiratory syncytial virus, Rhinovirus, Measles virus, Hepatitis C virus, Dengue virus, Myxoma virus, Varicella-zoster virus, Herpes simplex 1, Modified Vaccinia Ankara virus, HIV-1 [19, 21, 22]. This raises the question of whether colchicine could be used to prevent complications arising from these viral infections.

Among the many candidates successfully inhibiting NLRP3-1 in vitro, none is effective in vivo [8, 9]. One excellent candidate for inhibiting NLRP3-I is colchicine, one of the world’s oldest anti-inflammatory drugs [8, 23, 24]. It is currently approved for the treatment of acute gout, familial Mediterranean fever, Behçet’s disease, pericarditis, and several other inflammatory conditions [25].

Colchicine exerts both anti-inflammatory and antiviral properties. It inhibits NLRP3-I activation, neutrophil chemotaxis, adhesion, and mobilization; reduces TNF-

On these grounds, more than 50 studies, including observational investigations, randomized clinical trials, small non-controlled randomized trials, and other research, have evaluated colchicine for COVID-19 treatment. Unfortunately, these efforts have almost exclusively employed low doses and yielded highly contradictory results [9]. In previous publications, we have repeatedly pointed out the flawed approach adopted in the vast majority of these trials. Low doses of colchicine are insufficient to effectively inhibit NLRP3-I, which is a prerequisite for achieving meaningful therapeutic benefit, and helps explain the inconsistent findings [2, 8, 9, 25]. This underlines the rationale for exploring higher colchicine doses for the treatment of COVID-19, summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [3, 4, 8, 12, 13, 23, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33]).

| Reasons | References |

| Colchicine is an affordable, low-cost drug, known to mankind for at least 3575 years | [8, 23] |

| COVID-19 complications are due to CS and the coagulopathy, generated by the hyperactivation of NLRP3-I | [3, 4] |

| The main generator of CS are the myeloid cells, showing robust NLRP3-I expression | [12, 27] |

| Colchicine inhibits NLRP3-I at micromolar concentrations | [28] |

| Colchicine accumulates in myeloid cells, reaching much higher concentrations compared to plasma | [29, 30] |

| Colchicine has been used in high doses in the past for treating gout without life-threatening effects, and in doses below 0.1 mg/kg, it is completely safe | [26, 31] |

| Colchicine has antiviral effects | [13, 32] |

| Colchicine is not an immunosuppressant | [33] |

It has long been known that when colchicine is administered, the drug disappears quickly from the blood and in a short time accumulates and is retained in the leukocytes, where it stays long enough to exert its anti-inflammatory effect [29, 30, 34].

These inhibitory effects require colchicine binding to intracellular tubulin, inhibiting microtubule polymerization and subsequent signaling pathways necessary for NLRP3-I assembly, and hence, the attainment of sufficient intracellular levels is a central prerequisite for activity [29, 30]. On these grounds, the intracellular colchicine concentrations, rather than its amount in the plasma, should be considered as determining predictors of response. Understanding how colchicine is sequestered within leukocytes at therapeutic high doses is central to optimizing dosing and avoiding toxicity. Multiple pharmacokinetic studies have shown that, despite the low nanomolar levels, the drug is capable of significantly accumulating inside polymorphonuclear cells and monocytes, attaining intracellular levels to orders of magnitude higher than the corresponding plasma levels [13, 29, 30, 34, 35]. Data from two exemplary studies are summarized in Table 2 (Ref. [29, 30]).

| Pharmacokinetic parameters | Colchicine dose | ||||||

| 0.25 mg | 0.5 mg | 1 mg | |||||

| Single | Multiple | Single | Multiple | Single | Multiple | ||

| Plasma | |||||||

| Tmax (hr) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | - | |

| Cmax or Css (ng/mL) | 0.87 | 1.14 | 2.69 | 2.57 | 5.50 | 0.7–1.4 | |

| Cmax or Css (nmol/L)a | 2.18 | 2.85 | 6.73 | 6.43 | 13.77 | 1.75–3.50 | |

| t1/2 (hr) | 24.52 | 23.23 | 29.02 | 23.91 | 13.50 | 49 | |

| PNC | |||||||

| Tmax (hr) | 8 | 24 | 8 | 24 | 48.00 | - | |

| Cmax or Css (ng/1 | 5.20 | 9.66 | 13.05 | 30.84 | 31.00 | 20–53 | |

| Cmax or Css (nmol/L)a | 26 | 48.4 | 65.3 | 154.3 | 155.2 | 100.2–399.4 | |

| t1/2 (hr) | 20.21 | 39.92 | 46.05 | 41.90 | 41.00 | 41.00 | |

| MNC | |||||||

| Tmax (hr) | 12 | 24 | 8 | 24 | 48.00 | - | |

| Cmax (ng/1 | 11.85 | 10.58 | 28.35 | 32.13 | 25.80 | 9–24 | |

| Cmax or Css (nmol/L)a | 59.3 | 50.97 | 141.95 | 160.87 | 129.18 | 45.0–120.17 | |

| t1/2 (hr) | 9.13 | 18.32 | 18.87 | 20.06 | 35.00 | 46.00 | |

a roughly estimated assuming a mean cellular volume of 500 fL and 0.5 mL for 109 cells.

WBC, white blood cells; PNC, polymorphonuclear cells; MNC, mononuclear cells.

Notably, a recent pharmacokinetic study using state-of-the-art analytical techniques showed that even very low doses of colchicine produce substantial intracellular concentrations. After multiple administrations of 0.25 mg/day, the intracellular concentrations approached 50 nmol/L, and after 0.5 mg, they exceeded 100 nmol/L—markedly surpassing the corresponding plasma levels in healthy Japanese individuals [30]. Consistently, repeated 1 mg daily doses yield steady state concentrations of 100–400 nmol/L in polymorphonuclear cells, compared to only 1.75–3.5 nmol/L in plasma [29].

In vitro experimental evidence shows that colchicine inhibits NLRP3-I activation, reducing cytokine release and other downstream events at micromolar concentrations [28, 36, 37], questioning the feasibility of the standard doses of the drug in COVID-19. The rationale of the colchicine-based treatment protocol, successfully applied in four clinical centers in Bulgaria, is based on the application of high doses, including a maximum of 5 mg during the first day, followed by 2.5 mg daily thereafter [2, 8, 38]. Even though dose increase beyond 1 mg could be associated with a nonlinear rise in intracellular concentrations due to tubulin-binding sites and transporters within leukocytes being saturable, the significantly higher dose intensity and the previously mentioned propensity of the drug to accumulate in white blood cells is expected to allow reaching or exceeding the range for effective NLRP3-I inhibition, which is the central paradigm of our treatment strategy.

Colchicine is given at different doses for different diseases [8]. Interestingly, in Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF), if there is no response to standard dosing, the “the maximum tolerated dose” is recommended [39]. Our unofficial observations suggest this can reach values of 10–12 mg in some cases!

With these arguments in mind, we investigated the effect of higher doses of colchicine in both inpatients and outpatients. In studies enrolling a total of 795 inpatients treated with high doses of colchicine, mortality was reduced by 2- to 7-fold, showing a clear dose-dependent effect (RR = 0.282; 95% CI = 0.125–0.638; p = 0.0024) [38]. Among outpatients, high-dose colchicine treatment practically prevented hospitalizations and showed an inverse relationship with hospitalization rates [10]. The maximum loading dose we have used—up to 5 mg of colchicine (0.045 mg/kg)—has proven completely safe [2, 8, 19]. We have also published a series of clinical cases demonstrating the life-saving effects of high-dose colchicine [2, 8].

Several case reports from our group describing accidental high-dose exposures provide additional support for the high-dose colchicine approach. One 32-year-old patient with COVID-19 bilateral pneumonia and pericardial effusion accidentally took 15 mg of colchicine within 10 hours. Aside from a transient diarrhea, no severe toxicity was observed. Remarkably, the patient experienced full resolution of both pulmonary and cardiac inflammation without further treatment and was discharged on day 9. Other cases involving accidental doses of 12.5 mg also resulted in complete recovery [8]. While anecdotal, these findings offer compelling evidence that high-dose colchicine can exert potent anti-inflammatory effects in COVID-19, presumably by attaining significant intracellular levels in the target WBC populations to effectively inhibit NLRP3-I.

RECOVERY trial, the largest randomized controlled study worldwide, “found no evidence of a benefit from colchicine” for the treatment of COVID-19 [40], and the co-chief investigator, Prof. Sir Martin Landray, concluded: “We do large randomised trials to establish whether a drug that seems promising in theory has real benefits for patients in practice. Unfortunately, colchicine is not one of those” [41]. Based on that, the WHO issued a “strong recommendation against” the use of colchicine for this purpose (https://www.bmj.com/content/370/bmj.m3379).

It is important to note, however, that these conclusions apply to low-dose colchicine. Whether a cohort treated with higher-than-standard doses of colchicine might have yielded different results—an area that RECOVERY failed to address—remains an open question. Some of the considerations supporting this approach are summarized in Table 1.

Although the RECOVERY-based guidelines have undoubtedly influenced therapy across the globe, it is also to be questioning whether omitting colchicine may have prevented saving millions of lives. These are tough questions that require close scrutiny (Table 3, Ref. [24]).

| Why were only low colchicine doses used in the colchicine trials? |

| Why are the recommended low doses of colchicine treating gout automatically and uncritically extrapolated to COVID-19? |

| Why wasn’t the 2010 gout clinical trial repeated with low and high doses of colchicine [24] in COVID-19 as well? |

| Why was the misleading conclusion about the ineffectiveness of colchicine allowed, without emphasizing that it only concerned low doses? |

| Which is preferable: alive with diarrhea or dead without diarrhea? |

As we noted earlier, authors using slightly higher doses of colchicine found positive trends [38]. For example, in the RECOVERY trial, the dose of colchicine for 5 days was 5.5 mg [40], while at 7.5–8 mg for the same period, Lopes et al. [42] reported “reduction of the length of both, supplemental oxygen therapy and hospitalisation”. They later concluded that these effects were due to inhibition of NLRP3-I by colchicine [43]. Similar results point to increasing colchicine doses within reasonable limits to more successfully inhibit hyperactivated NLRP3-I, a hallmark of severe COVID-19.

Given colchicine’s known narrow therapeutic index, the use of higher doses unavoidably raises a safety concern. To address this, we reviewed reports of colchicine-associated mortality in the literature from 1947 up to the present. Based on this overview, we consider that doses of less than 0.1 mg/kg are completely safe, and those ranging from 0.1–0.2 mg/kg may lead to intoxication in some cases, but not to a lethal outcome. Colchicine has repeatedly been administered as so-called loading “overdoses” of 3 to 6.7 mg without any life-threatening effect. Our maximum loading dose of 5 mg (ca. 0.045 mg/kg) falls within this range. The most common colchicine-attributable side effects are gastrointestinal, particularly transient diarrhea, which we find an acceptable low price to pay for a lifesaving treatment [8, 9, 26, 31, 38].

Colchicine, administered in high doses, is a cheap, accessible, and effective drug for preventing the complications of COVID-19 and probably other infectious diseases associated with NLRP3-I hyperactivation.

VM had substatntial contribution to conceptualized the paper, designed the analysis of the study and wrote the rest of the text and compiled Fig. 1. GM wrote the part concerning the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, intracellular accumulation of colchicine, the pharmacokinetic data analysis, and compiled Table 1. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who worked with high doses of colchicine and especially to Dr. Tsanko Mondeshki. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

The work was funded by Project BG-RRP-2.004-0004-C01 financed by Bulgarian National Science Fund. The research is financed by the Bulgarian National Plan for Recovery and Resilience.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.