1 Institute of Cell Biophysics, Russian Academy of Sciences—a Separate Division of Federal Research Center Pushchino Research Center for Biological Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences (ICB RAS), 142290 Pushchino, Russia

Abstract

Mitochondrial dynamics—the balance between fission, fusion, and mitophagy—are essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis and are increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Here, we investigated the effects of targeted modulation of mitochondrial fission and fusion on mitochondrial morphology and metabolic status in primary hippocampal cultures derived from 5xFAD transgenic mice. Mitochondrial dynamics were modulated using the fission inhibitor Mitochondrial Division Inhibitor 1 (Mdivi-1), the fusion promoter mitochondrial fusion promoter M1 (MFP M1), and exogenous zinc as a fission activator. We evaluated mitochondrial morphology, lipofuscin accumulation, beta-amyloid (Aβ42) levels, and reactive oxygen species (ROS). The general condition of the cultures was assessed morphologically using neuronal and astrocytic markers.

Modulating mitochondrial dynamics altered mitochondrial morphology, decreased Aβ42, lipofuscin, and ROS levels, and improved cellular organization. Treatments with MFP and Mdivi-1 promoted mitochondrial hyperfusion without complete network integration and were associated with reduced astrogliosis and increased neuronal density. In contrast, zinc induced dose-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation and astrocytic clasmatodendrosis, with lower concentrations enhancing Aβ clearance and higher concentrations inducing toxicity.

Mitochondrial fusion and fission significantly influence lipofuscin and amyloid accumulation in 5xFAD cultures, underscoring their potential as therapeutic targets in neurodegenerative diseases. We propose that mitochondrial morphology acts as a key regulator of both cellular homeostasis and disease pathology.

Keywords

- mitochondria

- mitochondrial fusion

- mitochondrial fission

- mitochondrial dynamic

- Alzheimer’s disease

- lipofuscin

- primary cell culture

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has a complex etiology, with mitochondrial dysfunction extensively studied as a potential contributing factor [1]. Mitochondrial dysfunction, particularly related to bioenergetics and its impact on neuronal fate and degeneration, is recognized as one of the most critical factors in the pathogenesis of AD [2].

Mitochondria undergo fusion in response to increased energy demands or fission to isolate and eliminate damaged mitochondria via mitophagy [3]. This sequence of processes is referred to as mitochondrial dynamics, and maintaining a proper balance among fusion, fission, and mitophagy is essential for optimal cellular function [4, 5]. Disruptions in mitochondrial dynamics and clearance can lead to chronic energy dysregulation, contributing to oxidative stress, accumulation of neurotoxic proteins such as beta-amyloid (A

Mitochondria exhibit remarkable variability in shape and structural organization within cells [8]. Each distinct mitochondrial morphology plays a critical role in different cellular processes, reflecting cell-type–specific adaptations in mitochondrial function [9, 10, 11]. Mitochondrial fusion is traditionally associated with enhanced adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production due to increased cristae surface area, greater dimerization of ATP synthase, and more efficient oxidative phosphorylation [12, 13]. However, in most studies, fused mitochondria refer to interconnected mitochondrial networks, rather than to hyperfused megamitochondria, which, although present in primary cultures, are much less common. Notably, giant mitochondria are more frequently described in other tissues [14, 15]. Mitochondrial fission, in contrast, is associated with cellular stress and degeneration [16], and excessive fragmentation has been observed in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and in various model organisms [17, 18, 19, 20].

A

This study investigates the regulation of mitochondrial fusion and fission in primary astrocyte-neuron co-cultures derived from the hippocampi of 5xFAD transgenic mice. These mice serve as a genetic model of AD, mimicking the accumulation of pathological A

This study explores the effects of a Mitochondrial Division Inhibitor 1 (Mdivi-1), a Mitochondrial Fusion Promoter M1 (MFP M1), and a low-concentration zinc chloride solution (Zn) as a fission activator. Mdivi-1 is a cell-permeable quinazolinone compound, recognized as a mitochondrial fission inhibitor targeting the evolutionarily conserved mitochondrial GTPase Dnm1/Drp1 (dynamin-related GTPase/dynamin-like protein 1), a key regulator of mitochondrial fission, and has demonstrated neuroprotective effects in AD models [49, 50, 51, 52]. However, its effects are not entirely straightforward: in addition to inhibiting Drp1, Mdivi-1 may increase ROS production, trigger mitochondrial retrograde signaling, and inhibit mitochondrial complex I [53, 54]. In contrast, MFP M1 is a cell-permeable phenylhydrazone compound [55], that enhances MFN2 (mitofusin-2) expression, a key protein involved in outer mitochondrial membrane fusion. MFP M1 has been shown to reduce brain mitochondrial dysfunction [56], particularly in tauopathy models [57]. In our study, zinc chloride was used to modulate mitochondrial fission. Exogenous zinc colocalizes with mitochondria [58], and its accumulation triggers Drp1-dependent fission through the Zip1 transporter, which interacts with Drp1 [59, 60, 61]. Zinc-induced mitochondrial fission is toxic, often promoting ROS production and mitochondrial fragmentation [62, 63]. Fragmentation amplifies oxidative stress by increasing electron leakage from the respiratory chain, whereas enhanced fusion stabilizes the mitochondrial network and reduces ROS levels.

We also evaluate how these mitochondrial modulators affect ROS levels as part of the broader cellular stress response. Identifying compounds that selectively promote mitochondrial fission remains a challenge. While fission can be physiologically beneficial, it is often observed in pathological contexts—making therapeutic induction of fission a complex process. Moreover, mitochondria may undergo fission in response to a wide range of stressors, further complicating the search for effective, specific fission activators [64, 65, 66, 67]. For example, respiratory chain inhibitors and oxidative phosphorylation uncouplers can cause mitochondrial fragmentation [68, 69].

Our previous study showed that manipulating mitochondrial dynamics can induce pathological features even in healthy cells [70]. Here, we evaluate the astrocyte-to-neuron ratio in our cultures before and after treatment with mitochondrial modulators. In addition, we examine levels of A

The animals used in this study were 5xFAD mice, a double transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurons of 5xFAD mice, both in vivo and in culture, accumulate A

To minimize animal suffering, invasive procedures such as band surgery were avoided. Instead, natural delivery was used, followed by rapid guillotination of newborns in vitro, enabling hippocampal extraction for primary cultures. To reduce intra-litter variation, animals from different litters were used across the experiment. The experimental protocol was approved by the Bioethics Commission of ICB RAS (Approval ID: 1/032023, date: 2023-3-22).

Mixed astro-neuronal cultures were established from 0–1-day-old mice to investigate cellular characteristics in vitro. The hippocampi were mechanically dissociated and treated with a Trypsin-EDTA solution (lot 25200056, Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA). The resulting cell suspension was transferred to wells coated with Poly-D-Lysine (A3890401, Gibco, USA) or to glass slides coated with the same substrate, to ensure adequate adhesion. After attachment, the cultures were maintained with Neurobasal Medium (21103049, Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 2% B-27 (17504044, Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin-Glutamine (10378016, Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA). Cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2, and cultures were harvested for experimentation after 14 days of maturation.

To increase heterogeneity, multiple hippocampi were pooled and mechanically divided into 4–5 fragments, minimizing variability linked to genetic and environmental factors within a single litter. The design aimed to reduce the number of animals used while ensuring sufficient biological replication. On average, each hippocampus yielded three biological replicates.

Mitochondria were visualized by transduction/transfection of cultures with the CellLight BacMam 2.0 Red system (C10600, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). This pre-constructed vector employs BacMam 2.0 technology to introduce a fluorescent protein fused to the E1-alpha-pyruvate dehydrogenase leader sequence. The reagent was applied according to the manufacturer’s protocol and incubated with cells for 16 hours before use.

Mitochondrial morphology was assessed in live, unfixed cell cultures using a Leica DM IL LED microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) with a

Two compounds with different mechanisms were used to modulate mitochondrial dynamics. The first, Mdivi-1 (475856, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), is a cell-permeable quinazolinone compound that reversibly inhibits dynamin-like protein 1 (Drp1), a key fission GTPase. The second substance, MFP M1 (SML0629, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), is a cell-permeable hydrazone that promotes mitochondrial fusion without affecting endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and lysosomes morphology. Substances were applied according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cultures were analyzed at 1 day and 5 days post-treatment with Mdivi-1 (10 µM) and MFP M1 (5 µM). The 1-day point captured early responses (network reorganization, ATP production, oxidative stress), while the 5-day point revealed sustained effects and adaptations.

Since no direct fission activators are commercially available, zinc chloride (Z0152, Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) was used in PBS at high (1 µM) and low (0.1 µM) concentrations. High concentrations caused pronounced mitochondrial and cellular stress; therefore, experiments were limited to 1 day. Low concentrations were used to modulate morphology without acute toxicity, with both 1-day and 5-day assessments performed.

Protein concentrations were normalized using Lowry’s method combined with UV spectroscopy [73]. The absorbance peak of tryptophan-containing proteins at 286 nm was recorded with a spectrophotometer Perkin Elmer MPF-44B (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Calibration curves were generated from known protein standards, plotting concentration against absorbance.

Lipofuscin, an autofluorescent pigment, was quantified spectrofluorimetrically as a marker for cellular metabolic stress. Primary hippocampal cultures were washed three times with PBS, then transferred to 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Samples were agitated for 5 minutes on a cooled shaker, lysed, and frozen for later use. Protein concentrations were normalized to 50 µg per sample. Lipofuscin was detected by its emission peak at ~450 nm upon excitation at 360 nm, measured with a Perkin Elmer MPF-44B spectrofluorimeter (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA), gain

A

Mitochondrial superoxide was measured with MitoSox-red (M36008, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After treatment with test compounds, culture medium was changed, and cultures were incubated with 2.5 µM MitoSox-red for 20 minutes, then washed and analyzed with a fluorimetric plate reader (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA).

For of neurons and astrocytes markers, cell cultures were fixed for 10 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde. Membrane permeability was increased with 0.2% Triton X-100, and nonspecific binding to antigens was blocked in PBST (PBS + 0.1% Tween 20) with 1% BSA, 10% normalized donkey serum (ab7475, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and 5% normalized goat serum (31872, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Cultures were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, followed by fluorescent secondary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS (pH 7.4) for 5 minutes between steps. The following primary and secondary antibodies were used to stain for neurons—Anti-MAP2 (microtubule-associated protein 2) antibody (ab32454, Abcam, Cambridge, UK, 1:200) and corresponding Alexa 594 nm (ab150080, Abcam, Cambridge, UK, 1:400); astrocytes—Anti-GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) antibody (ab4674, Abcam, Cambridge, UK, 1:800); Alexa 488 nm (ab150169, Abcam, Cambridge, UK, 1:1000).

Imaging was acquired with a JuLI Stage fluorescence microscope (NanoEntek, Seoul, South Korea). Background correction was applied with the microscope’s software to ensure uniform illumination and contrast. Images were analyzed in ImageJ software. To quantify neuronal and astrocytic contributions, images were processed with ImageJ algorithms and converted into binary black-and-white format. The total image area was defined as 100%, and the fraction occupied by immunopositive structures was expressed as a percentage of this total.

Image analysis was performed in ImageJ. Statistical analyses were conducted in SigmaPlot 12.5 (Grafiti LLC, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and OriginPro 10.1.0.178 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Data in the text are presented as mean

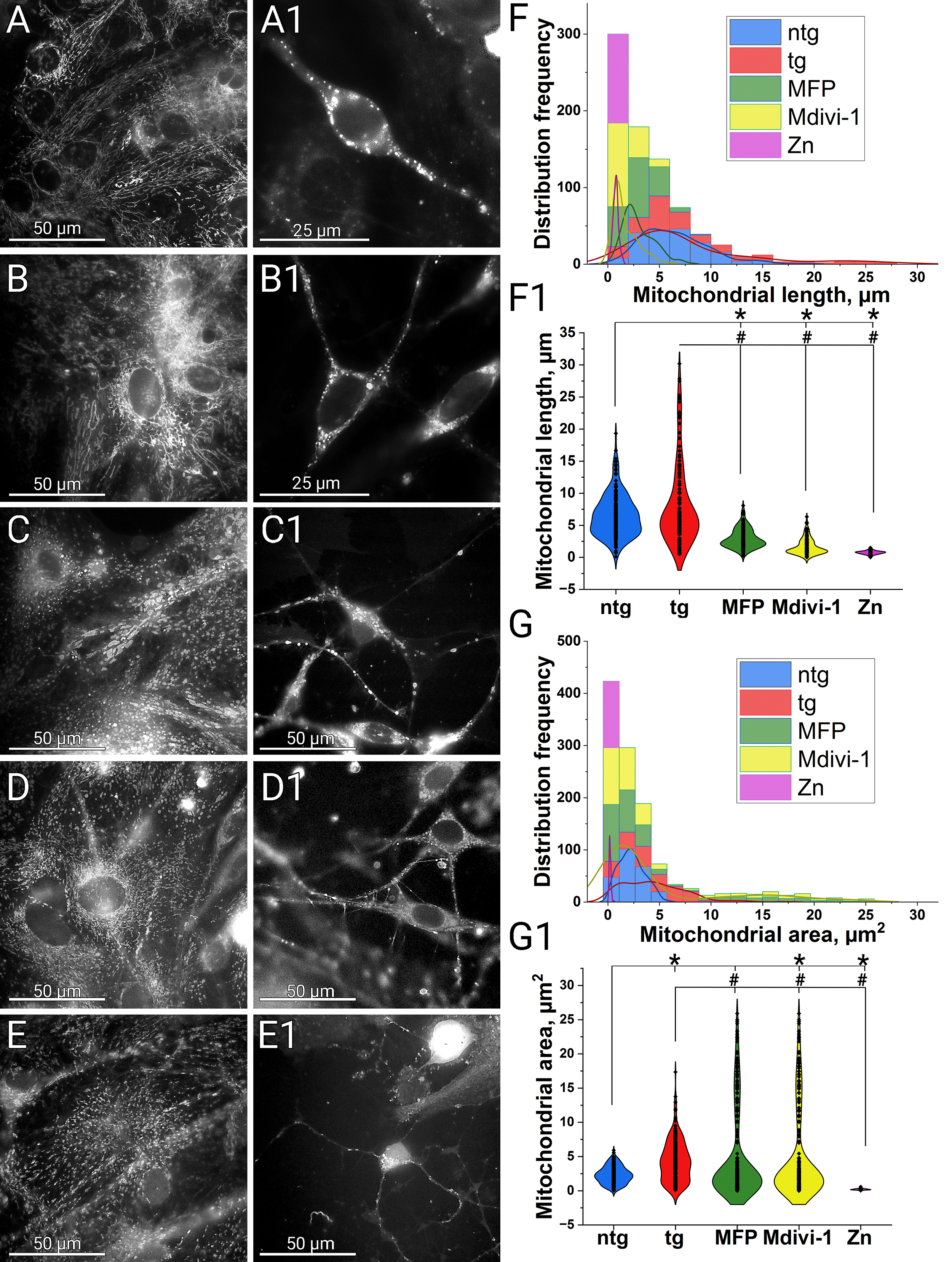

Analysis of mitochondrial morphology revealed that mitochondria in 5xFAD (tg) cultures were, on average, longer, had a larger area, and displayed greater heterogeneity compared to those in non-transgenic (ntg) cultures (Fig. 1). In ntg cultures, mitochondrial lengths were tightly distributed within 6.5

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Modulation of mitochondrial fusion and fission. Comparison of mitochondrial morphology in ntg and 5xFAD cultures and its alteration after treatment with Mdivi-1, MFP M1 and zinc. Mitochondria staining was performed by transfection/transduction with the CellLight BacMam 2.0 system. Mitochondrial morphology was examined on a Leica DM IL LED microscope using a

We next examined whether modulation of fusion and fission could alter these pathological features. Treatment with MFP M1 led to defragmentation of the mitochondrial network, with an average mitochondrial length of 3

We initially expected Mdivi-1 treatment to promote mitochondrial elongation and network formation. However, under our conditions, Mdivi-1 induced mitochondrial network defragmentation in astrocytes, with an average mitochondrial length of 1.6

One possible explanation is that Mdivi-1 is not a strictly selective inhibitor of Drp1 GTPase but also suppresses respiratory chain complex I, an effect independent of Drp1 and not associated with mitochondrial elongation [75]. Consistently, the same authors showed that Mdivi-1 did not alter mitochondrial morphology in COS-7 cells after 24 h and did not prevent staurosporine-induced fragmentation, supporting the view that its effects are not Drp1-specific. Additionally, Mdivi-1 has been shown to reduce mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP synthesis while altering calcium homeostasis [54]. A decline in membrane potential activates the mitochondrial metalloendopeptidase OMA1 (OMA1 protease) [76], which cleaves OPA1 mitochondrial dynamin like GTPase (OPA1) and disrupt inner membrane fusion, potentially driving passive network dispersal despite Drp1 inhibition.

Another possibility involves Drp1-independent fission during mitophagy. Although Drp1 is central to mitochondrial fission, residual fragmentation persists even in its absence, suggesting alternative pathways for mitochondrial division [77, 78]. A Drp1-independent fragmentation pathway has also been described, during mitophagy, in coordination with isolation membrane and autophagosome formation [79]. Although mitophagy was not directly assessed here, the fragmentation observed with Mdivi-1 may reflect adaptive remodeling to facilitate turnover of dysfunctional organelles rather than stress-induced damage. Importantly, because Mdivi-1 does not block fusion, mitochondria can rejoin the network, preserving some plasticity. In parallel, chronic amyloid stress in 5xFAD may enhance actin- and endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-dependent mitochondrial constriction, a pathway independent of Drp1, that involves remodeling of ER-mitochondria contacts and actin polymerization, leading to constriction and fragmentation [80, 81].

Finally, metabolic side effects of Mdivi-1 may indirectly suppress fusion through MFN1/2 degradation, OPA1 proteolysis, altered oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) protein expression, and increased superoxide production [82], collectively favoring fragmented mitochondrial forms. A transient response is also possible, with initial fission inhibition inducing hyperfusion, followed by a compensatory rebound fission as the drug is metabolized or inactivated. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and likely interact to produce the complex phenotype observed.

To further modulate fission, we applied exogenous zinc chloride. At high concentrations, zinc acted primarily as a toxicant, whereas lower concentrations produced morphologically evident fission without immediate neurite damage. Zinc exposure caused nearly complete mitochondrial network fragmentation into small elements that, under our experimental conditions, could not always be reliably dissolved. The average mitochondrial length was 0.7

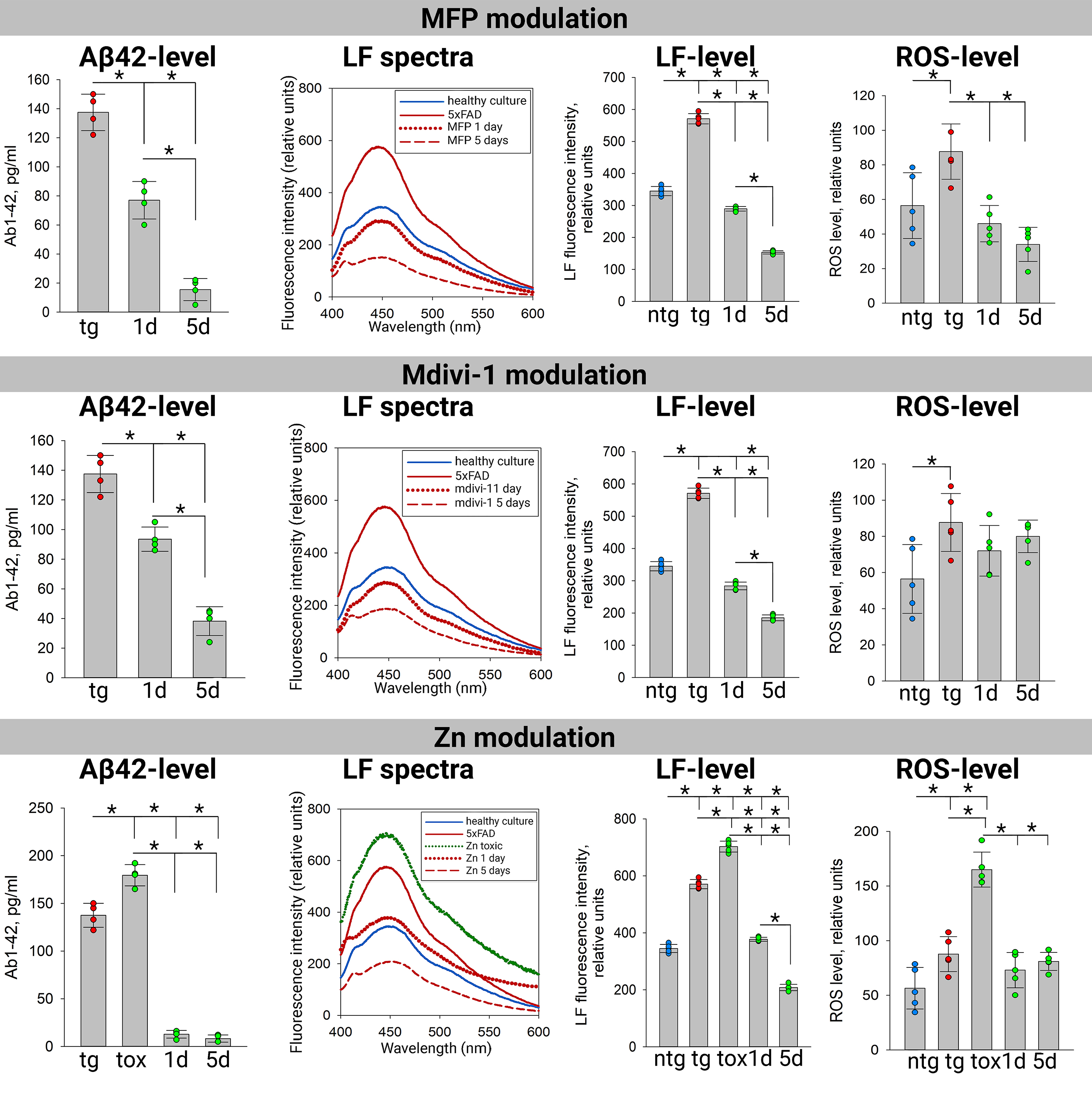

Next, we assessed the levels of lipofuscin, ROS, and A

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Accumulation of beta-amyloid, lipofuscin and ROS in 5xFAD transgenic cultures under the action of mitochondrial dynamics modulators. A

As expected, untreated 5xFAD transgenic cultures exhibited significantly higher lipofuscin accumulation (570.9

In untreated 5xFAD transgenic cultures, A

The role of zinc in AD pathogenesis remains controversial. While some studies suggest therapeutic potential for zinc chelators [88, 89], others report protective effects of Zn-enriched diets [87, 90]. A major mechanism of zinc neurotoxicity is its ability to accelerate A

ROS levels followed a pattern consistent with mitochondrial dysfunction in 5xFAD transgenic cultures, showing a significant increase compared to nontransgenic controls. In nontransgenic cultures (56.4

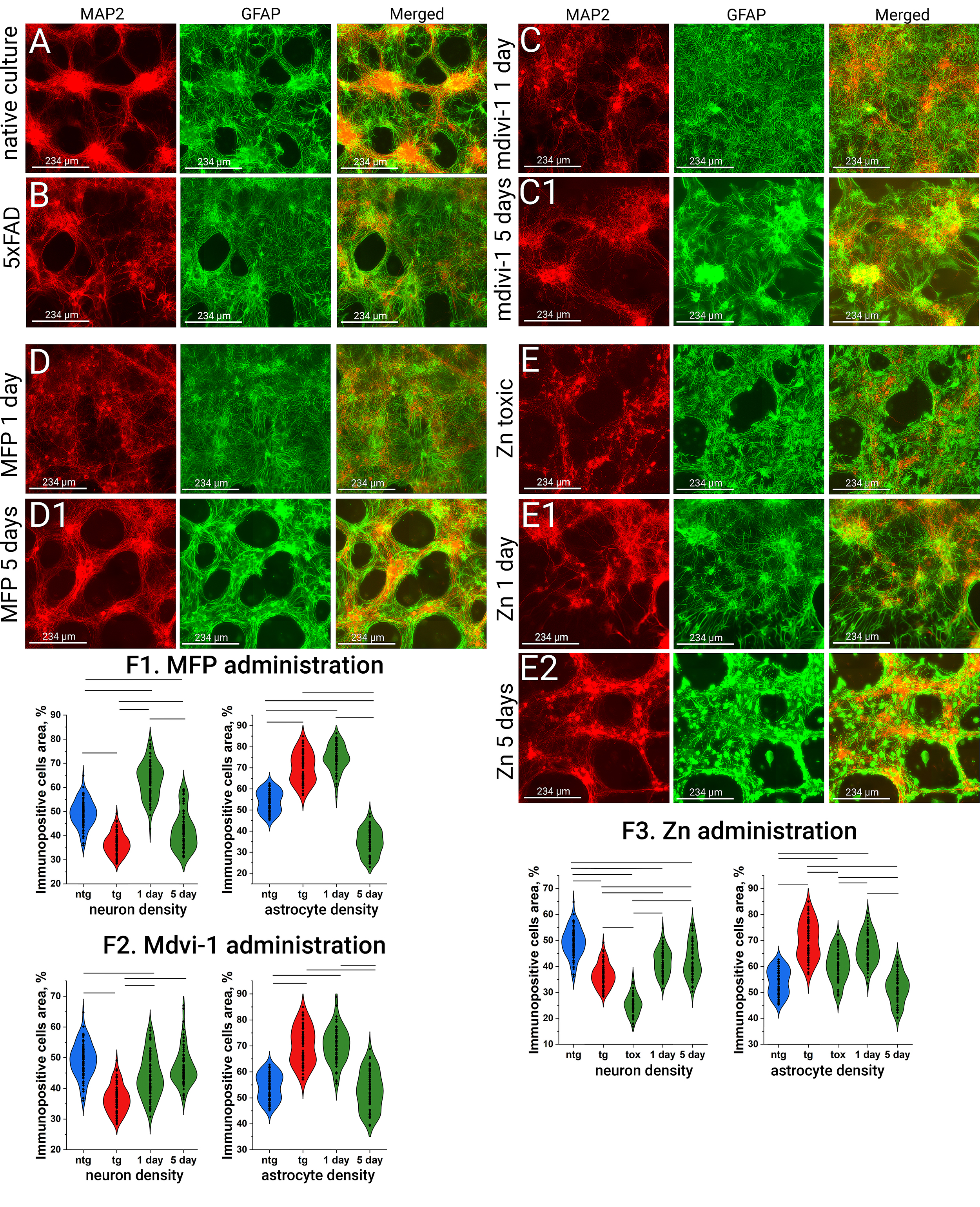

As shown in Fig. 3, transgenic 5xFAD and nontransgenic cultures exhibit distinct morphological characteristics despite being prepared under identical culture conditions. 5xFAD cultures are characterized by pronounced astrogliosis (54.2

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Immunopositivity to the astrocyte marker (GFAP in green) and the neuronal marker (MAP2 in red) in primary neuronal cultures under the administration of fusion and fission activators. (A) Control non transgenic culture. (B) Control transgenic 5xFAD culture. (C,C1) Effect of Mdivi-1 on culture morphology after 1 and 5 days of administration. (D,D1) Effect of MFP M1on culture morphology after 1 and 5 days of administration. (E–E2) Effect of Zn on culture morphology after exposure to a toxic concentration and after 1 and 5 days of recovery. (F1–F3) Neuronal and astrocytic densities (in %) under the effect of MFP M1, Mdivi-1, and Zn, Lines indicate p

Treatment with the mitochondrial fission inhibitor Mdivi-1 led to a significant increase in neuronal density after one day (44.0

Exposure to high concentrations of exogenous zinc, a known mitochondrial fission activator, resulted in marked neurotoxicity. Neuritic degeneration was evident (neuronal density 25.2

In contrast, low-dose zinc exposure produced a markedly different effect. After one day, a modest decrease in astrocytic density was observed (66.7

Although the connection between mitochondrial dynamics and culture architecture appears intuitive, direct evidence has been limited. While theoretical models propose that mitochondrial behavior shapes culture morphology, empirical validation has been lacking. Our findings demonstrate that mitochondrial remodeling influences not only intracellular metabolism [114], but also the structural organization of neuron-astrocyte cultures. The changes in cellular arrangement following manipulation of fusion and fission suggest that mitochondrial dynamics affect intercellular interactions and coordinated behavior within the culture.

Variations and specificity in mitochondrial dynamics may be closely linked to particular cellular functions and requirements, differing across cell types [115]. For instance, studies have shown that mitochondrial dynamics regulate cell morphology in the developing cochlea [116]. Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction has been associated with impaired brain development, depletion of the adult neural stem cell pool, and disruptions in both embryonic and adult neurogenesis [117]. In addition, mitochondrial dynamics are essential for regulating stem cell identity, self-renewal, and fate decisions [118]. Inactivation of the fusion protein OPA1, for example, has been shown to impair both tissue regeneration and stem cell pluripotency [119]. Further studies are needed to determine whether the observed metabolic changes are a direct consequence of mitochondrial remodeling or part of a broader cellular stress response aimed at maintaining homeostasis.

Even if one does not fully embrace the mitochondrial theory of Alzheimer’s disease as the central paradigm, mitochondria undeniably remain among the most critical regulators of cellular health. Their ability to alter phenotype through fission and fusion directly affects cell morphology and structural organization in complex cell communities such as primary cultures of hippocampal cells. In our study, modulation of mitochondrial dynamics significantly influenced the accumulation of lipofuscin, a well-established marker of intracellular stress and aging, as well as A

We propose that mitochondrial morphology acts as a key regulator of both cellular homeostasis and disease pathology. Mitochondrial dynamics thus emerge as promising therapeutic targets in neurodegenerative disease models. Future research should focus on clarifying the interplay between mitochondrial remodeling and protein degradation systems (including autophagy and mitophagy), and how these interactions influence cell survival, neuroinflammation, and disease progression in vivo. A more comprehensive understanding of these mechanisms could facilitate the development of mitochondria-targeted strategies to restore cellular balance and delay the onset or progression of neurodegenerative disorders.

Although Mdivi-1, MFP M1, and Zn were used to selectively modulate mitochondrial fusion and fission, these compounds may exert broader effects on cellular homeostasis. Mdivi-1, as an inhibitor of Drp1, affects not only mitochondrial fission but also peroxisomal dynamics, apoptotic signaling, and calcium homeostasis. Similarly, MFP M1, by enhancing mitochondrial fusion, may alter ER-mitochondria communication, mitophagy efficiency, and oxidative stress levels. Prolonged mitochondrial fusion could impair the clearance of dysfunctional organelles, potentially leading to secondary metabolic disturbances. Zinc, used here as a fission activator, also has well-documented effects on cellular signaling, calcium regulation, and oxidative stress. While low concentration may promote physiological fission and adaptive mitochondrial responses, excessive Zn exposure can disrupt proteostasis, enhance lipid peroxidation, and induce cytotoxicity. Future studies should therefore carefully evaluate the broader metabolic consequences of these interventions, as well as their potential off-target effects on neuronal and astrocytic functions.

Some aspects of our findings would also benefit from a complementary assessment of autophagic and mitophagic activity. The observed changes in mitochondrial morphology, ROS levels, and aggregate accumulation suggest potential alterations in mitochondrial turnover and proteostatic mechanisms; however, direct evaluation of autophagy and mitophagy markers was not included in the current study and should be addressed in future investigations.

Finally, while our in vitro findings provide valuable insights into the mitochondrial dynamics, their direct translation to in vivo conditions remains uncertain. In the brain, mitochondrial homeostasis is influenced by systemic factors, including neuroinflammation, vascular supply, and intercellular metabolic interactions, which cannot be fully replicated in primary cultures. In addition, in vivo pharmacokinetics may alter the efficacy and distribution of mitochondrial modulators. Future studies using whole-animal models will be necessary to assess the systemic impact of mitochondrial dynamics in Alzheimer’s disease.

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ROS, reactive oxygen species; A

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

AC designed the research study. AC and DZ performed the research. AC analyzed the data. AC wrote the manuscript. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The laboratory animals were treated in accordance with the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrates used for experimental and other purposes (Strasbourg, 1986). All animal procedures performed with mice were approved by the Bioethics Commission of the Institute of Cell Biophysics (ICB RAS, Pushchino Research Center for Biological Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences) (Approval ID: 1/032023; Date: 2023-3-22) in accordance with Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament.

The authors acknowledge institutional support from ICB RAS and IBI RAS, which provided the necessary facilities and resources for this study.

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (RSF), project No. 23-25-00485.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT in order to check spelling and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL44648.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.