1 Children’s Cancer Institute, Lowy Cancer Research Centre, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2031, Australia

2 School of Clinical Medicine, UNSW Medicine & Health, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia

3 UNSW Centre for Childhood Cancer Research, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2031, Australia

Abstract

Oncogenic FGFR4 signalling represents an attractive therapeutic target across multiple cancers, yet treatment resistance almost uniformly occurs. A critical mechanism steering resistance is a rapid and complex reprogramming of kinase signalling networks, called the adaptive bypass response. Capturing this dynamic rewiring to pinpoint, on a molecular level, the right combinatorial drug for the right FGFR4-driven cancer patient at the right time, will be key to achieving sustained tumour responses. But how can one accurately capture this process across different cancer types exhibiting contrasting levels of FGFR4 signalling pathway components and network behaviours? A recent study by Shin et al. delivers a technically elegant and biologically grounded exploration of the adaptive signalling landscape to tackle this, revealing cell context-dependent combinatorial strategies.

Keywords

- cancer

- FGFR4

- molecular targeted therapy

- signal transduction

- precision medicine

- drug resistance

- drug combination

Aberrant signalling of the Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK) FGFR4 is an emerging therapeutic target across various cancers. Mechanisms driving pathway dysregulation are diverse, and include FGFR4 activating mutations, amplification and overexpression in breast cancer (BC), and ligand/receptor co-expression, such as FGF19/FGFR4 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and FGF8/FGFR4 in a subset of rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) [1, 2, 3, 4]. FGFR4-specific kinase inhibitors have shown encouraging efficacy in preclinical and early clinical settings, yet, as with any kinase inhibitor, intrinsic and acquired resistance remain a major barrier to durable outcomes. An important mechanism steering resistance is the dynamic adaptive bypass response, which involves rapid reprogramming of kinase signalling networks upon drug exposure that enable tumour cells to circumvent drug target inhibition. Understanding the mechanism, molecules and biology driving this initial resistance and identifying matched rational drug combinations to overcome it, will be key to achieving durable responses. Capturing this process is however complicated, not in the least due to the complexity of positive and negative feedback loops, and the vast molecular heterogeneity across the different FGFR4-driven cancers. Thus, for FGFR4-targeted therapies, how can one accurately capture and understand these complex resistance dynamics across different FGFR4-driven cancers, to ultimately determine which targeted drug combination is expected to work best for which patient? A recent study from Shin et al. [5] elegantly addresses this problem by integrating computational network modelling with experimental validation, offering a framework to predict resistance dynamics and tailor combinatorial strategies accordingly. This Opinion Article aims to both discuss the scientific and methodological achievements of this study, and place their findings into the broader context of FGFR4 resistance mechanisms.

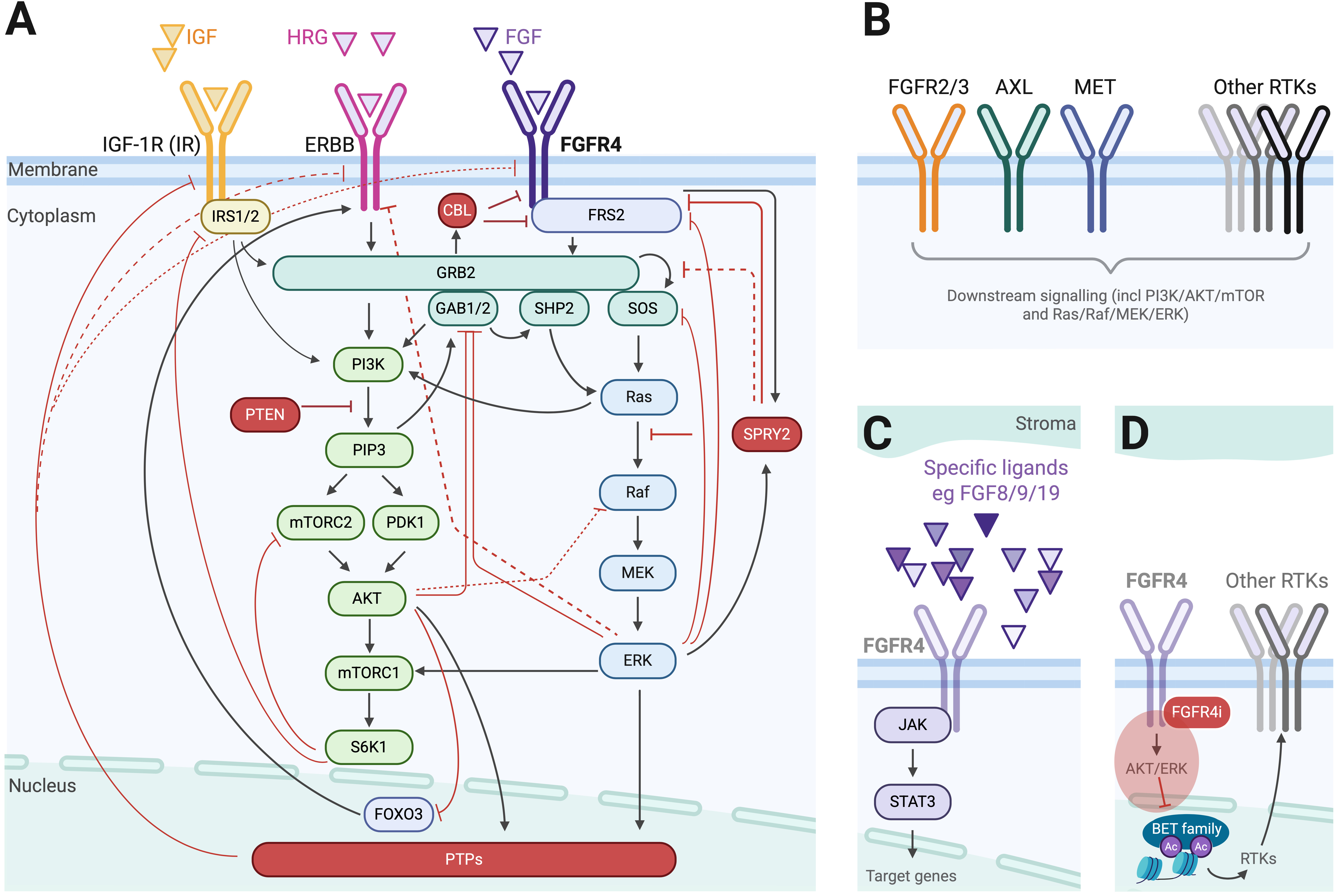

To elucidate mechanisms of rapid adaptive resistance to FGFR4-inhibitors across cancer types, Shin et al. [5] first developed a mechanistic mathematical model of the FGFR4 signalling network. At its core, the model centres on FGFR4 and its downstream signalling cascades via FRS2-, PI3K/AKT/mTOR- and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK-pathways. To account for pathway convergence from other RTKs, it also incorporates IGF1R/IR and ErbB family receptors. Key negative feedback regulators, such as CBL, SPRY2, and protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) activity, are also integrated in the model (Fig. 1A, Ref. [5]). This model was iteratively refined using experimental data from MDA-MB-453 triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells harbouring an activating FGFR4 mutation. Model calibration was guided by cell viability assays and Western blot data capturing key kinases’ temporal responses to FGFR4 inhibition alone and in combination with predicted synergistic or non-synergistic agents. Upon successful prediction and experimental validation in this model, the authors expanded their framework using protein expression profiles from 350 cancer cell lines in the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) [6]. This enabled simulation of context-specific adaptive responses to FGFR4 inhibition across diverse tumour types. Model outputs stratified cancer cell lines into four distinct categories based on AKT and/or ERK pathway reactivation (“rebound”) dynamics following FGFR4 inhibition. Functional validation confirmed AKT-mediated resistance in the FGFR4 mutationally-driven TNBC model, and ERK-mediated resistance in an FGF19-amplified HCC cell line, Hep3B. These findings support rational combination strategies, pairing FGFR4-inhibitors with AKT- or ERK-inhibitors, tailored to the network dynamics of each tumour.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The FGFR4 signalling network and molecular mediators of resistance to FGFR4 inhibition. (A) The FGFR4 signalling network utilized by Shin et al. [5] as the basis for their mathematical model. Red molecules and lines represent negative pathway modulators; black arrows represent pathway stimulation. PTPs, protein tyrosine phosphatases. (B) Illustration of alternate molecular mediators driving FGFR4-inhibitor resistance not captured in the published model, focussing on receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). (C) Illustration of alternate molecular mediators driving FGFR4-inhibitor resistance not captured in the published model, illustrating extracellular ligand- and intracellular STAT3-signalling. (D) Illustration of how inhibition of FGFR4-signalling with an FGFR4-inhibitor (FGFR4i, shown in red) is hypothesized to relieve transcriptional repression of other RTKs via nuclear BET/epigenetic-signalling. Created in BioRender. Fleuren, E. (2025) https://BioRender.com/vwaokpc.

This study represents a novel integration of mechanistic modelling, in silico drug combination screening, and experimental validation to comprehensively interrogate adaptive resistance mechanisms within the FGFR4 signalling network. Its iterative model-experiment cycle enables unbiased predictions of non-obvious drug combinations: a substantial advantage over more intuitive approaches. A key study implication is that FGFR4-targeted drug combinations that may work for one patient or one cancer type, may not work for another, based on the dynamic behaviour of the associated FGFR4 network. What would be worthy of further exploration, is examine how many CCLE cell lines could be considered FGFR4-driven (e.g., by harbouring FGFR4 activating mutations or FGFR4 and/or ligand overexpression), and how these would map specifically onto the model’s rebound categories. For instance, when considering FGFR4 protein expression alone, only 12 lines exhibit a normalized score

Another intriguing finding emerged from TNBC cells, where co-inhibition of FGFR4- with AKT-inhibitors proved more effective than co-treatment with PI3K-inhibitors, despite both targeting the same signalling axis. This divergence is particularly noteworthy given AKT-, PI3K-, or mTOR-inhibitors are often used interchangeably, in clinical practice often guided by drug accessibility or anticipated toxicity rather than a mechanistic rationale, and often favouring mTOR-inhibitors in that respect [7]. By leveraging a systems-level approach, the authors further elucidated that the observed differential efficacy stemmed from the network’s negative feedback architecture. Specifically, negative regulators such as CBL, SPRY2, and PTPs played a pivotal role in modulating AKT reactivation dynamics following FGFR4 inhibition. These insights underscore the importance of interrogating full network behaviours, involving both positive and negative regulators, rather than solely relying on static analysis of canonical pathway nodes.

A notable strength of the study is its integration of large-scale proteomics data to inform combinatorial drug decision-making, for which biomarkers are notoriously difficult to pinpoint. While genomics has traditionally dominated biomarker discovery, genomics-based predictive biomarkers for FGFR4-inhibitor efficacy such as FGFR4 mutations or FGF-ligand expression do not fully capture the molecular context of tumours, nor account for dynamic changes in protein expression. Proteomics offers a more comprehensive view of the proteome, complementary to genomics, enabling the identification of additional or more nuanced markers of response and resistance. As precision medicine platforms increasingly incorporate proteomic data, including tumour microenvironmental components, the integration of such profiles into predictive models is expected to enhance the identification of optimal combinatorial therapies and improve patient outcomes [8].

Shin et al.’s framework [5] distinguishes itself from earlier models through its breadth and depth, incorporating both canonical effectors and less commonly modelled components such as tumour suppressor genes and phosphatases. But does it capture all potential molecular effect modulators? While the model is comprehensive and offers valuable insights, it is inherently shaped by its scope. If model complexity would allow, and appreciating the trade-offs with identifiability and predictive power, the model could benefit from some refinements and expansions, as detailed below.

At its core, the model centres on FGFR4 and its major downstream signalling cascades, supported by both literature and iterative experimental validation in a TNBC cell line (Fig. 1A). While the authors included two additional RTK families, namely IGF1R/IR and ErbB, this largely reflects relevance to TNBC. Given the diversity of RTK expression across tumour types, incorporating additional RTKs where feasible might improve applicability across cancers, and reveal alternate resistance mediators to further guide combination strategies (Fig. 1B). FGFR3 can for example compensate for FGFR4 inhibition in HCC, and the RTKs MET and AXL confer resistance to various (receptor tyrosine) kinase inhibitors across different cancer types, including those sensitive to FGFR4 inhibition [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. As the model, in addition to AKT-targeting, also predicted and validated ErbB-targeting to be of synergistic relevance in TNBC, a similar rebound might exist with other RTKs in other cancer types. Another pathway worthy of exploration is the JAK/STAT-pathway, as recent studies highlighted STAT3 activation in response to FGFR4 blockade (Fig. 1C) [15].

Additionally, in an ideal scenario, this and many other predictive models would benefit from capturing extracellular features, such as ligand-level dynamics and other tumour microenvironment (TME) features. The TME is however notoriously difficult to model and challenging to experimentally validate. Although ligands for IGF1R, FGFR4 and ErbB are for example broadly depicted in the model figures, it is unclear how differential protein expression of such ligands will affect the system. While Hep3B cells used in this study overexpress FGF19, and two rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines (Rh41 and Rh30) included in CCLE are known to overexpress FGF8, neither FGF19, nor FGF8, is listed in the CCLE protein dataset [6]. Furthermore, in HCC models, including Hep3B, stroma-derived FGF9 promotes tumorigenicity and resistance to the multi-kinase inhibitor sorafenib, and pro-tumorigenic effects of FGF9 could only be abrogated by an FGFR1/2/3-inhibitor, but not through FGFR4-inhibition. FGFR2 was suggested as a potential mediator in this response (Fig. 1B,C) [16]. Another study in HCC cells illustrates how exogeneous EGF supplementation resulted in FGFR4-inhibitor resistance, which was effectively reverted by EGFR- (and SHP2)-inhibitors [17].

By examining kinase network remodelling within hours after drug exposure, Shin et al. [5] demonstrated that cancer context-dependent co-targets exist for FGFR4-mediated therapies. But will these novel combinations be the key to eliciting durable tumour responses in patients with FGFR4-driven cancers?As the authors acknowledge, it remains critical to evaluate the long-term efficacy and durability of such combinations in models that better recapitulate the clinical setting. Will the proposed combinatorial strategies elicit sustained tumour control, or will resistance eventually re-emerge via alternative pathways? Unless the combination effectively eradicates all cancer cells, surviving cell populations, even under combination treatment pressure, may undergo further adaptive rewiring. Taking TNBC with AKT rebound and accordingly co-targeted with AKT- and FGFR4-inhibitors as an example, activation of alternative RTKs or bypassing the PI3K–AKT axis through reactivation of MAPK-signalling might occur in the longer term [18]. A particularly compelling feature of the novel framework is that it could, in principle, capture this next layer of network dynamics and work beyond predicting synergistic drug pairs. Redeploying the model to map adaptive reprogramming under combination therapy might reveal additional targets for triplet or higher-order drug combinations. The prospect of transforming the model to a dynamic platform, with scope to deliver adaptable, evolution-informed sequential therapeutic strategies over time, significantly extends its future impact. One point of caution however is that not all high(er)-level combinations might be feasible. An interesting alternate approach suggested in the literature to bypass this, involves blocking the adaptive response itself via transcriptional repression at the epigenetic level. In HER2-amplified cell lines treated with lapatinib for example, targeting BET-family bromodomain mediators inhibited lapatinib-induced kinome reprogramming [19, 20], and a similar effect was reported in melanoma, where targeting BRD/BET-proteins inhibited the adaptive kinome upregulation and enhanced effects of BRAF/MEK-inhibitors [21]. While a similar approach might enhance efficacy of FGFR4-inhibitors (Fig. 1D), an important point of caution is that BRD/BET-inhibitors can, particularly when used in drug combinations, result in significant toxicity [22]. Thus, while rationally-selected kinase inhibitor combinations might still provoke adaptive signalling responses, selectively targeting critical nodes, even if this necessitates a triplet regimen, remains the favourable approach.

While tumour heterogeneity and the TME are hard to capture in current systems, these will be essential for predicting clinical efficacy. Future work incorporating longitudinal sampling, functional profiling of resistant clones, and more clinically-relevant models will be important in truly determining the therapeutic promise of these combinations. It will also be of interest to explore how the new modelling approach could be applied to new FGFR4-based therapy combinations, such as the combination of FGFR4-inhibitors with the immune checkpoint inhibitors pembrolizumab (NCT04699643) and spartalizumab (NCT02325739), since these approaches have shown promising efficacy in FGFR4-driven cancers, including HCC [23, 24].

Shin et al.’s study [5] exemplifies how coupling computational modelling with experimental validation can decode the complexity of FGFR4 signalling, reveal context-specific resistance mechanisms and identify rational, personalised combination strategies to overcome FGFR4-inhibitor resistance. The ability to predict and validate synergistic drug combinations based on computational modelling of early signalling network dynamics, incorporating non-intuitive behaviour, represents a major advantage over earlier studies. While the model omits elements like the TME and broad RTK coverage, it lays a strong foundation for future explorations. As clinical proteomics data become increasingly available, this framework offers an exciting opportunity to tailor therapies across heterogeneous and adaptive tumour landscapes. It highlights the potential of signalling network modelling as a powerful addition to the precision oncology toolbox; one that anticipates tumour evolution and informs rational and adaptable therapeutic strategies accordingly.

EDGF confirms responsibility for all aspects of this manuscript; from its conception, literature review, manuscript writing, results presentation, figure construction, and revising the final version. EDGF contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. EDGF read and approved the final manuscript. EDGF participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

EDGF is supported through a Col Reynolds Mid-Career Discover Fellowship from The Kids’ Cancer Project.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.