1 Department of Oncology, Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 430030 Wuhan, Hubei, China

Abstract

To evaluate cysteine dioxygenase 1 (CDO1) gene promoter methylation in circulating tumor DNA as a biomarker for the early diagnosis of lung cancer.

Data up to June 5, 2025, across electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure) were searched. The quality assessment tool for diagnostic accuracy studies-2 (QUADAS-2) checklist was used to assess the risk of bias in the incorporated studies. A random-effects model was employed to generate summary statistics for diagnostic accuracy, which included pooled sensitivity and specificity estimates, the diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), and a summary receiver operating characteristic curve. An exploration of heterogeneity sources was undertaken using meta-regression, followed by a sensitivity analysis to test the consistency of the results. Finally, Deek’s funnel plot was generated to estimate publication bias, and the clinical feasibility was evaluated using Fagan’s nomogram.

Seven relevant studies were included in this meta-analysis. No major concerns regarding the quality risk of the included studies were observed. The pooled diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, and DOR values of the CDO1 promoter methylation for lung cancer were 0.63 (95% CI: 0.60–0.67), 0.78 (95% CI: 0.74–0.82), and 5.96 (95% CI: 4.06–8.74), respectively, and the area under curve was 0.7423. Statistical heterogeneity was observed in sensitivity (I2 = 73%, p < 0.1), specificity (I2 = 79.5%, p < 0.1), and DOR (I2 = 42.9%, p < 0.1); however, variables such as the region, sample source, sample size, and detection method did not significantly affect heterogeneity (p > 0.05). The results were robust as the DOR was not overly influenced by the deletion of any single study. No publication bias was observed in this study (p = 0.74). Additionally, under a pre-test probability of 20%, the positive post-test probability of CDO1 promoter methylation in lung cancer was predicted to be 42%. PROSPERO CRD420251131665, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251131665.

The detection of CDO1 promoter methylation in biofluids represents a promising tool for the early diagnosis of lung cancer. Future studies should focus on improving detection methodologies and investigating combinational strategies with high accuracy.

Keywords

- lung cancer

- circulating tumor DNA

- methylation

- cysteine dioxygenase 1

Despite decades of advancement in treatment, lung and bronchus cancer remains the principal cause of cancer mortality [1, 2, 3]. Improving the efficacy of the early detection of lung cancer is critical for improving the clinical outcomes of patients. Although screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) leads to a significant relative reduction (20.0%) in lung cancer-related death (95% CI, 6.8 to 26.7; p = 0.004), the failure to accurately distinguish malignant and benign lung nodules through LCDT remains a major challenge [4, 5]. Moreover, tissue biopsy continues to be the gold standard for tumor diagnosis owing to its remarkable consistency and high accuracy of results; however, it is limited by its invasive properties, tumor spatial heterogeneity, and inability to achieve continuous monitoring [6]. In recent years, the development of liquid biopsy has revolutionized the early detection, recurrence prediction, and treatment outcome monitoring of lung cancer [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. Compared with tissue biopsy, liquid biopsy presents a non-invasive as well as quick and continuous detection method that focuses on detecting molecular markers such as circulating tumor cells, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), and tumor-derived extracellular vesicles in plasma and other biofluids including urine, bronchial washing fluid, ascites, pleural fluid, and sputum [10, 12]. The genetic information carried by ctDNA broadly indicates that in the tumor tissue, including somatic variants, methylation status, and microsatellite instability [13]. Furthermore, owing to the relative short fragment length and short half-life, ctDNA are less affected by intratumor heterogeneity and serve as a real-time tumor biomarker, allowing for dynamic monitoring of tumor progression [6].

Aberrant DNA methylation is an early tumorigenic event associated with poor therapeutic outcomes, making it a viable target for both early cancer detection and prognostic assessment [14, 15]. For example, the detection of Septin9 DNA methylation in plasma (Epi proColon) is used for the early screening of colorectal cancer, while its sensitivity and specificity still need to be improved [16, 17]. Although methylation markers including short stature homeobox gene 2 (SHOX2) and Ras association domain family 1A (RASSF1A) have shown promising diagnostic value for lung cancer, their accuracy is still under clinical evaluation [18]. Therefore, other methylation markers need to be uncovered. The tumor suppressor gene cysteine dioxygenase type 1 (CDO1) has garnered considerable attention in recent years as a potential ctDNA methylation marker across human cancers [19, 20, 21]. CDO1 is a crucial enzyme catalyzing cysteine oxidation, causing the reduction of antioxidant glutathione and synthesis of taurine. Consequently, CDO1 is fundamentally involved in facilitating both ferroptosis and apoptotic cell death in malignant cells [22]. Genetic and epigenetic alterations, particularly promoter methylation, have been identified across cancers [22]. Early in 2012, CDO1 was identified as one of the hypermethylated and downregulated genes in human lung squamous cell carcinoma via whole-genome analysis [23]. CDO1 promoter methylation, either alone or in combination with other targets, demonstrates promising diagnostic prospects in lung cancer [24, 25, 26].

In light of the correlation observed for CDO1 promoter methylation in lung cancer, we aim to explore the feasibility of non-invasive CDO1promoter methylation detection for the early diagnosis of lung cancer by systematically reviewing the published data.

We conducted this meta-analysis in accordance with preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies (PRISMA-DTA) [27]. The research protocol has been registered on PROSPERO with registration number CRD420251131665, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251131665. Two researchers independently searched online databases containing data up to June 5, 2025, including PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Embase (https://www.embase.com), Web of Science (https://www.webofscience.com/), and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) (https://www.cnki.net/). The key terms used in the search strategies were (“CDO1” OR “Cysteine Dioxygenase 1”) AND (“Lung Neoplasm” OR “Lung Cancer” OR “Pulmonary Neoplasm”) (Supplementary Table 1).

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

(1) Population (P): The subjects of the included studies should be patients diagnosed with lung cancer.

(2) Intervention (I): The performance of CDO1 ctDNA methylation for the early detection of lung cancer should have been evaluated.

(3) Comparison (C) and Outcome (O): Studies should include adequate data to obtain the true positive (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN), and false negative (FN) values for analysis of the sensitivity and specificity of CDO1 promoter methylation in lung cancer screening.

(4) Study design (S): Eligible studies for inclusion incorporate both retrospective and prospective researches.

Studies were excluded based on the following criteria:

(1) P: Studies based on other types of cancer.

(2) I: Studies that did not assess CDO1 promoter methylation for lung cancer detection, along with review articles, meta-analyses, patents, and reports based solely on cell lines or animal models. Studies using samples acquired from tissue were also excluded.

(3) C and O: Publications lacking sufficient data for analysis.

We employed the Quality Assessment Tool for Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool to assess the risk of bias in the studies included in our analysis [28]. The evaluation of bias risk was conducted independently by two reviewers following four key points including patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. The results were presented as “high risk”, “low risk”, or “unclear risk”. Finally, the two reviewers revised the results and resolved the conflicts. Review Manager 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) was utilized for visualization using the assessment.

Following a full-text review, we extracted the following data: (1) the first author’s last name and year of publication were extracted as study ID; (2) countries where the studies were carried out; (3) the sample size; (4) the TP, FP, FN, and TN were directly extracted or calculated; (5) tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stages and pathological subtypes of patients, (6) sample sources, such as plasma, urine, and sputum; and (7) detection methods. Two referees reviewed the studies independently, and any disagreements that arose between the referees were settled via a consensus-based discussion.

The data were analyzed using Meta-DiSc1.4 (Clinical Biostatistics Unit, Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain) and Stata 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) statistical software. The diagnostic accuracy of CDO1 promoter methylation for lung cancer was pooled using sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic odd ratio (DOR), and the summary receiver operating characteristic curve (sROC). We defined high heterogeneity as an I2 value greater than 50% or a p-value below 0.10, calculating it with Chi-squared and I2 statistics. Data with high heterogeneity were pooled using the random-effect model; otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used. Meta-regression analysis was performed to explore the sources of heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis was conducted using the leave-one-out method. The assessment for publication bias was performed by utilizing Deek’s funnel plot, and the feasibility of CDO1 methylation clinical application was evaluated using Fagan’s nomogram. We defined a p-value of less than 0.05 as indicative of statistical significance.

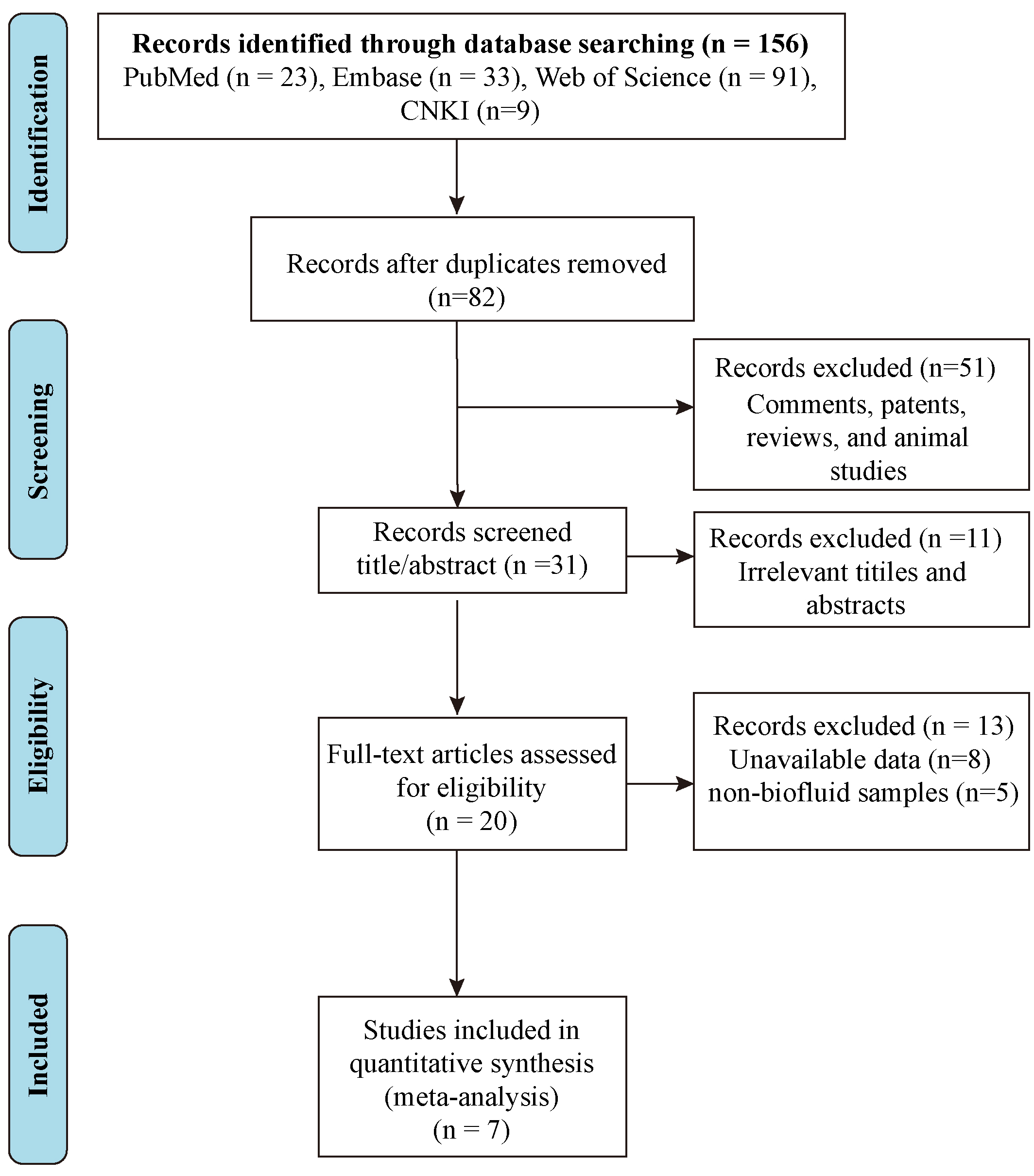

In total, 156 studies pertaining to CDO1 gene methylation in the context of lung cancer were initially identified from the electronic database. Following the exclusion of 74 duplicate records and 51 other types of publications (including comments, patents, reviews, and animal studies), the titles and abstracts of 31 publications were reviewed. Subsequently, 11 studies were excluded for failing to satisfy the predetermined inclusion criteria and the full texts of 20 articles were assessed for eligibility. Finally, after eliminating 13 studies for which data were unavailable or which were based on other sample sources, 7 relevant publications were selected for meta-analysis [26, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34] (Fig. 1). The main characteristics of the seven studies are presented in Table 1 (Ref. [26, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]). In five studies, plasma was used for the detection of CDO1 promoter methylation, and urine and sputum were applied in the other three studies. With the exception of the investigations by Wang et al. [34] and Chen et al. [33], which employed quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), the remaining five studies utilized quantitative methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (qMSP) to assess CDO1 promoter methylation status in biofluids [26, 29, 30, 31, 32].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of literature retrieval according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. CNKI, China National Knowledge Infrastructure.

| Author (year) | Country | TNM stage | Pathological subtype | Sample source | Sample size (Case/Control) | Cancer | Control | Detection method | |||

| LUSC | LUAD | SCLC | Others | (M+/M–) | (M+/M–) | ||||||

| Wever et al. (2022) [32] | The Netherlands | I–III | 16 | 27 | / | 1 | Urine | 44/50 | 30/14 | 17/33 | qMSP |

| Wang et al. (2020) [34] | China | I–IV | 29 | 112 | 14 | 23 | Plasma | 178/173 | 93/85 | 37/136 | qPCR |

| Liu et al. (2020) [30] | USA | I–IV | 9 | 65 | / | / | Plasma | 74/25 | 56/18 | 11/14 | qMSP |

| Urine | 71/27 | 51/20 | 10/17 | ||||||||

| Chen et al. (2020) [29] | China | I | 22 | 139 | / | 2 | Plasma | 163/83 | 103/60 | 14/69 | qMSP |

| Chen et al. (2017) [33] | China | I | 35 | / | / | / | Plasma | 35/20 | 18/17 | 1/19 | qPCR |

| Hulbert et al. (2017) [26] | USA | I–II | 26 | 121 | / | 3 | Sputum | 90/24 | 70/20 | 20/16 | qMSP |

| Plasma | 125/50 | 81/37 | 13/37 | ||||||||

| Park et al. (2024) [31] | Korea | I–IV | 42 | 53 | 26 | 4 | Bronchial washing fluid | 125/62 | 72/53 | 2/60 | qMSP |

LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; qMSP, quantitative methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

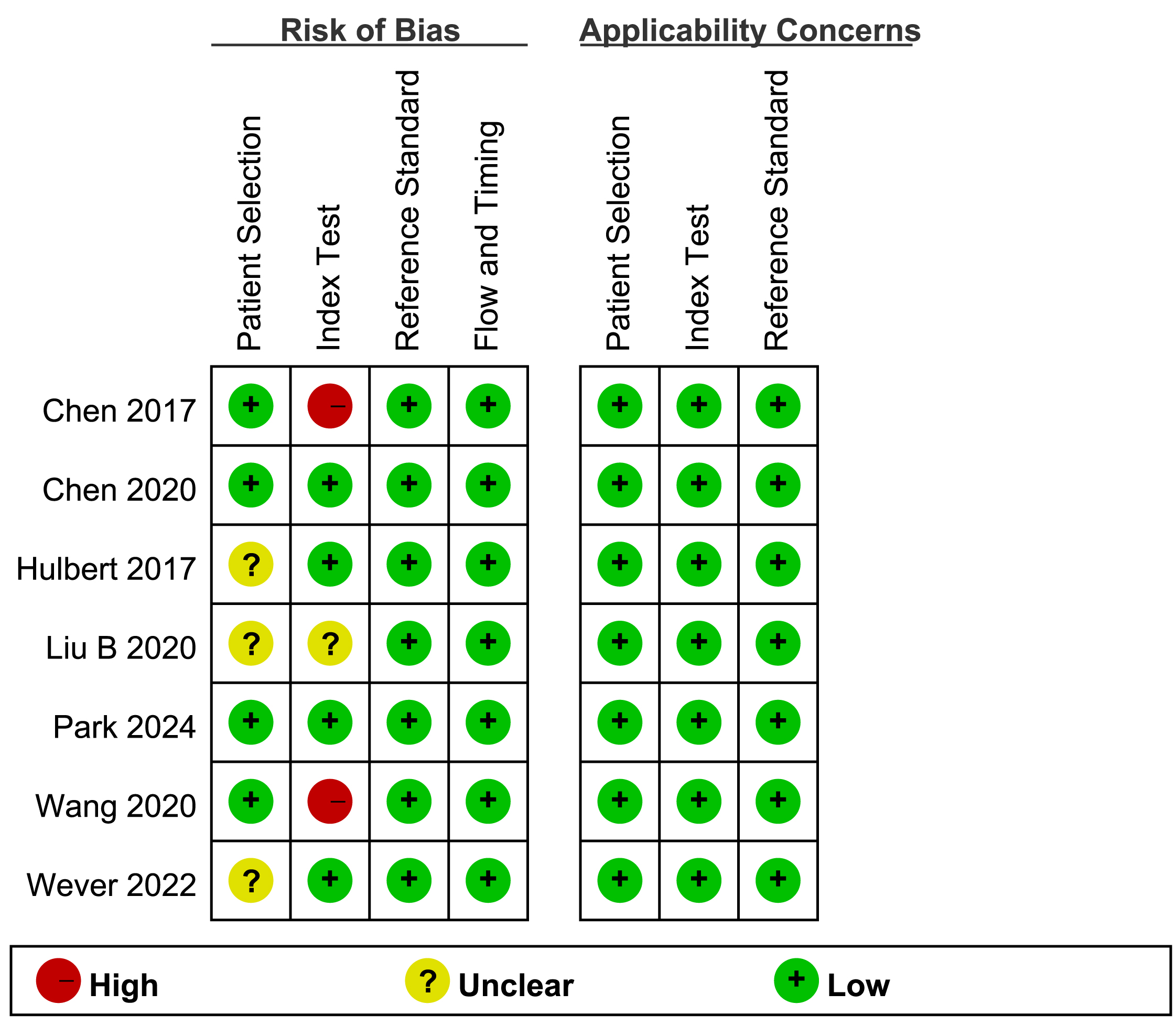

Quality assessment was performed using QUADAS-2 tool and the results are shown in Fig. 2. The risk of bias of the included studies was evaluated through patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. Regarding the patient selection, three studies were assessed as “unclear” owing to lack of information on whether they enrolled consecutive patients and whether they avoided a case-control design. In the assessment of the index test, two studies received a “high risk” rating because their results were interpreted with prior knowledge of the reference standard’s outcomes. The risk of bias was deemed “unclear” for one study, as the publication omitted details on whether the index test was interpreted independently of the reference standard. For the reference standard and flow and timing, all studies were assessed as “low risk”. In summary, no major concerns regarding quality risk of the included studies were observed.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Risk of bias and applicability concerns of included studies (QUADAS-2). QUADAS-2, Quality Assessment Tool for Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2.

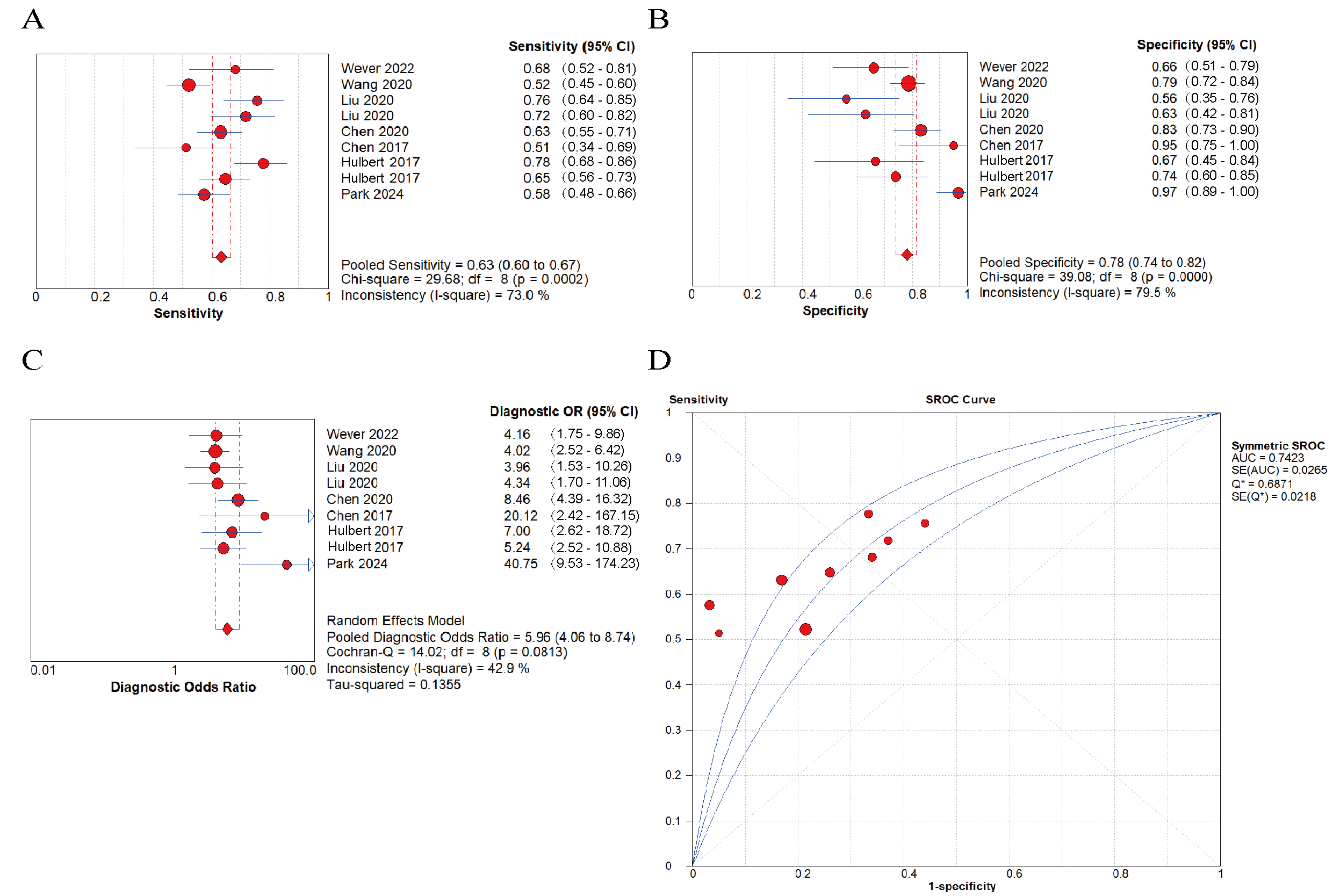

Chi-squared and I-squared statistic algorithms showed significant statistical heterogeneity in sensitivity (I2 = 73%, p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Diagnostic performance of cysteine dioxygenase 1 (CDO1) promoter methylation using biofluids for the early detection of lung cancer. (A) pooled sensitivity; (B) pooled specificity; (C) pooled diagnostic odds ratio (DOR); (D) summary receiver operating characteristic curve (sROC) with the Q*-index.

The pooled diagnostic performance of CDO1 promoter methylation for the early identification of lung cancer demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.63 (95% CI: 0.60–0.67) and a specificity of 0.78 (95% CI: 0.74–0.82) (Fig. 3). The pooled DOR was 5.96 (95% CI: 4.06–8.74) (Fig. 3), suggesting that a population bearing CDO1 promoter methylation had 5.96 times higher detection risk than the general population. In addition, the area under curve (AUC) was 0.7423 (Fig. 3), indicating that CDO1 promoter methylation in biofluids had prediction potential for lung cancer.

Moreover, we conducted a comparative analysis of CDO1 and other gene methylation tests including tachykinin-1 (TAC1), sex determining region Y-box 17 (SOX17), and homeobox A9 (HOXA9) to detect lung cancer. The results showed that the pooled sensitivity of CDO1 promoter methylation was lower than those of TAC1 (0.69 vs 0.74), SOX17 (0.67 vs 0.72), HOXA9 (0.69 vs 0.71), and multi-gene panels (0.67 vs 0.91) (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, the pooled specificity of CDO1 promoter methylation was higher than those of TAC1 (0.72 vs 0.71), HOXA9 (0.73 vs 0.52), and multi-gene panels (0.74 vs 0.57), but lower than that of SOX17 (0.75 vs 0.86) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

To analyze the heterogeneity sources, a meta-regression was conducted and variables included region (Asian countries/Western countries), sample source (plasma/other biofluids), sample size (

| Meta-Regression (Inverse Variance weights) | |||||

| Variables | Coeff. | Std. Err. | p-value | RDOR | [95% CI] |

| Region | 0.804 | 0.7287 | 0.3505 | 2.23 | (0.22; 22.71) |

| Sample source | –0.471 | 0.5512 | 0.4556 | 0.62 | (0.11; 3.61) |

| Sample size | –0.043 | 0.6757 | 0.9538 | 0.96 | (0.11; 8.23) |

| Detection method | 1.028 | 0.6871 | 0.2314 | 2.80 | (0.31; 24.91) |

Tau-squared estimate = 0.1738 (Convergence is achieved after 14 iterations), restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation. RDOR, relative diagnostic odds ratio.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis with the leave-one-out approach, whereby each study was iteratively removed, to assess the impact of individual studies on the meta-analytic results. As shown in Table 3 (Ref. [26, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]), the pooled DOR and 95% CI were recalculated after each exclusion. The results demonstrated that the pooled DOR remained largely unchanged regardless of the study being omitted, indicating that the overall findings were not overly influenced by any single study and that the conclusions are robust.

| Author (year) | DOR | 95% CI |

| Wever et al. (2022) [32] | 7.588 | 4.410–13.056 |

| Wang et al. (2020) [34] | 7.885 | 4.502–13.811 |

| Liu et al. (2020) [30] | 8.424 | 4.585–15.481 |

| Chen et al. (2020) [29] | 7.121 | 4.017–12.623 |

| Chen et al. (2017) [33] | 6.612 | 4.054–10.782 |

| Hulbert et al. (2017) [26] | 5.964 | 3.660–9.720 |

| Park et al. (2024) [31] | 5.800 | 3.855–8.725 |

| Combined | 6.930 | 4.280–11.210 |

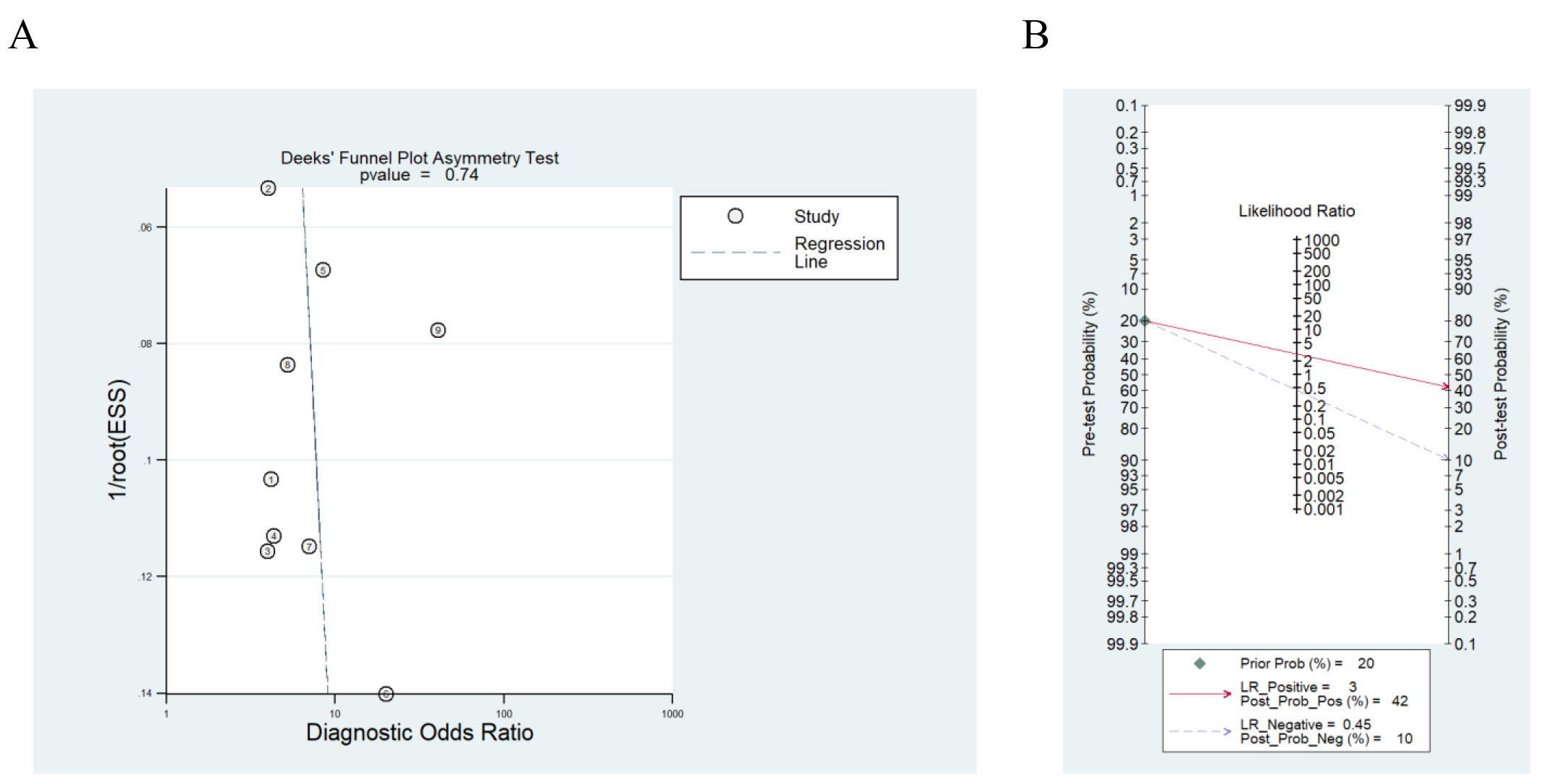

The results from Deek’s funnel plot revealed an absence of significant publication bias in the present meta-analysis (p = 0.74) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Potential clinical application of CDO1 promoter methylation. (A) Deek’s funnel plot in evaluation the publication bias. (B) Fagan’s nomogram of CDO1 gene methylation as a biomarker for lung cancer diagnosis.

Additionally, to evaluate the clinical feasibility of CDO1 promoter methylation, we performed Fagan’s nomogram. The result indicated that under a pre-test probability of 20% (according to the incidence rate of lung cancer among malignancies in China [35]), the positive post-test probability of lung cancer was 42% and the negative post-test yielded a 10% probability (Fig. 4B). It could be illustrated that with a preset predicted incidence rate of 20%, the probability of lung cancer reached 42% when CDO1 promoter methylation was detected. Conversely, in cases where CDO1 promoter methylation was not observed, the posttest probability was only 10% (Fig. 4B). The findings suggested that CDO1 promoter methylation had limited clinical applicability, as its detection positivity was associated with only a modest increase in the positive probability of lung cancer.

Recent investigative efforts have increasingly demonstrated that investigating efficient ctDNA methylation biomarkers for cancer detection have been carried out [14, 36, 37]. Methylation biomarkers such as RASSF1A and SHOX2 [38], adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) [39], O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) [40], and CDO1 [24, 25, 26] were demonstrated to be effective in the early detection of lung cancer; however, further verification of their accuracy is needed.

In our study, seven relevant studies were finally included for analysis of the diagnostic value of CDO1 promoter methylation in lung cancer detection. The quality assessment indicated that no major concerns regarding quality risk of the included studies were observed. We observed significant statistical heterogeneity in sensitivity (I2 = 73%, p

We also performed a comparative analysis of CDO1 and other gene methylation tests that were detected in the included studies. The pooled sensitivity of CDO1 promoter methylation was lower than those of TAC1 (0.69 vs 0.74), SOX17 (0.67 vs 0.72) and HOXA9 (0.69 vs 0.71), while the pooled specificity of CDO1 was higher than those of TAC1 (0.72 vs 0.71) and HOXA9 (0.73 vs 0.52). As multi-gene panels showed significantly higher detection efficiency than individual genes [26, 29, 30], we also compared the diagnostic efficacy between CDO1 and multi-gene panels. The results suggested that the pooled sensitivity of multi-gene panels was higher than that of CDO1 alone (0.91 vs 0.67), while the pooled specificity of multi-gene panels was lower than that of CDO1 alone (0.57 vs 0.74). The results indicated that DNA methylation sites and multi-gene panels with high diagnostic efficacy and consistency still need to be investigated.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this meta-analysis. (1) The included publications exhibited significant statistical heterogeneity. The included studies exhibited substantial heterogeneity in patient cohorts, specimen types, and methylation detection methods. Although a random-effects model was applied for statistical adjustment, variations in thresholds and protocols may still compromise clinical applicability. (2) The result may be uncertain owing to the small sample size. (3) The number of available publications was limited; further investigations are urgently needed. (4) Only English and Chinese publications were included, and the failure to cover regional databases and unpublished studies may introduce selection bias.

In conclusion, CDO1 promoter methylation using biofluids showed diagnostic potential for lung cancer diagnosis as a non-invasive method. Future studies should address improving detection methodologies and investigating combinational strategies with high accuracy.

The datasets generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

XY and QC proposed the idea. YY and ZX extracted the data, performed quality assessment and statistical analysis. YY, ZX, and FL organized the tables and figures, wrote, and revised the manuscript. YJ provided methodology and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers: 82003310 and 82472969) and National Major Science and Technology Project for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer, Cardio-cerebrovascular, Respiratory, and Metabolic Diseases (Directed Project, 2024) (Grant number: 2024ZD0519700, subproject number: 2024ZD0519702).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL43987.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.