1 Department of Cardiology, The Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University, 314000 Jiaxing, Zhejiang, China

2 Rhine-nahr-palatinate Heart and Vascular Center, 55543 Bad Kreuznach, Germany

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury represents the major obstacle to achieving successful therapeutic outcomes in acute myocardial infarction patients. Fat mass and obesity-associated protein (Fto), an N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA demethylase, has been shown to protect cardiomyocytes against oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion-mediated injury by regulating annexin A1 (Anxa1) expression in vitro. The present study aims to confirm the cardioprotective role of the Fto/Anxa1 axis using in vivo myocardial I/R injury models.

Wild-type (WT) and Anxa1 knockout (KO) mice underwent 30-min left coronary artery ligation and 2-h reperfusion after intramyocardial delivery of recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 encoding Fto (adFto) or a control vector (adnull). The effects of Fto overexpression on cardiac function, fibrosis, apoptosis, and inflammatory response were examined using echocardiography, Masson’s trichrome staining, western blot analysis, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and immunohistochemical staining. m6A-RNA immunoprecipitation-quantitative polymerase chain reaction quantified Anxa1 mRNA methylation.

Fto overexpression by adFto significantly improved cardiac function, reduced serum creatine kinase-myocardial band and troponin T levels, and alleviated cardiac fibrosis in I/R-injured WT mice. Mechanistically, Fto weakened I/R-induced global m6A levels and decreased m6A enrichment on Anxa1 mRNA, thereby enhancing Anxa1 expression. In Anxa1 KO mice, adFto did not confer functional or molecular benefit.

Fto enhances Anxa1 and mitigates myocardial I/R injury with suppression of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-, leucine-rich repeat-, and pyrin domain- containing receptor 3 (Nlrp3)-inflammasome signaling in vivo, identifying the Fto-Anxa1 axis as a mechanistic contributor and potential therapeutic target.

Keywords

- myocardial reperfusion injury

- annexin A1

- RNA methylation

- demethylation

- inflammasomes

Acute myocardial infarction (MI), resulting from acute coronary artery occlusion, represents a leading cause of mortality among cardiovascular disease patients [1]. Although timely reperfusion remains the most effective clinical strategy for myocardial salvage, revascularization paradoxically triggers myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, contributing to approximately 50% of the final infarct size [2]. Current therapeutic strategies for myocardial I/R injury primarily encompass non-pharmacological interventions, pharmacological therapies, and administration of human-induced pluripotent stem cells, yet clinical trials have demonstrated suboptimal outcomes [3, 4]. Consequently, elucidating the molecular pathways governing myocardial I/R injury progression and identifying novel therapeutic targets for effective clinical interventions are imperative.

Dynamic RNA epigenetic modifications, especially the reversible N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methylation, are increasingly recognized as pivotal regulators in cardiovascular pathophysiology [5]. m6A is installed by the Methyltransferase-like (Mettl)3-Mettl14 complex and removed by the demethylase Fat mass and obesity-associated protein (Fto), enabling rapid remodeling of mRNA fate in response to stress [6, 7]. During acute stress, m6A landscapes are reprogrammed to control the translation and stability of selective transcripts, thereby modulating adaptive responses [8]. In the heart, abrupt I/R and chronic comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension represent prototypical stress contexts in which such post-transcriptional control becomes crucial. As a critical m6A demethylase, Fto is implicated in the pathogenesis of various cardiovascular disorders [9]. Yang et al. [10] revealed that Fto alleviates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by activating the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (P21)/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway via m6A demethylation of tumor protein p53 or P21/Nrf2. Moreover, Fto mitigates myocardial I/R injury by inhibiting nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-, leucine-rich repeat-, and pyrin domain- containing receptor 3 (Nlrp3)-mediated pyroptosis via regulating casitas B lineage lymphoma mRNA stability and its dependent

As an endogenous anti-inflammatory molecule, Annexin A1 (Anxa1) plays a pivotal role in modulating inflammatory responses and cell survival [14]. Available evidence suggested that Anxa1 is closely associated with myocardial I/R injury. Recombinant Anxa1 reduces infarct size by 50% [15], and administration of Anxa1-derived peptide Ac2-26 shrinks infarct size and reduces myeloperoxidase and interleukin (IL)-1

The study focused on verifying the epigenetic regulatory mechanism of the Fto/Anxa1/Nlrp3 axis in myocardial I/R injury in animal models, thereby providing potential therapeutic targets for novel interventions.

All experimental procedures involving animals were undertaken in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines and received approval from the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jiaxing University Medical College (Approval No. JUMC2021-095). Wild type (WT) C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old; Cyagen, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China) and Anxa1 knockout (KO) mice with a C57BL/6 background (6–8 weeks old; Cyagen, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China) were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility under controlled conditions: relative humidity 40–70%, ambient temperature of 20–25 °C, 12-h light/dark cycle, and free access to food/water. Euthanasia was induced by placing animals in a chamber pre-filled with 100% medical-grade CO2 at a flow rate displacing 30–70% of the chamber volume per minute. After

Following standard procedures, mice underwent a transient left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery occlusion to induce cardiac I/R injury. Under general anesthesia (2% isoflurane), mice underwent endotracheal intubation with mechanical ventilation support. A 5-mm left thoracotomy between the 4th and 5th intercostal spaces was performed to expose the cardiac apex. A silk suture (8-0) was positioned 2–3 mm distal to the LAD origin, adjacent to the junction of the left atrial appendage and pulmonary artery. Coronary occlusion was achieved by tightening the suture loop, with successful ischemia induction confirmed by ST-segment elevation on continuous electrocardiogram monitoring and pallor of the distal myocardium. Following 30 min of ischemia, reperfusion (2 h) was initiated by suture release, evidenced by myocardial blush restoration. Postoperatively, mice were allowed to recover from anesthesia on a warm pad with ad libitum access to water and moistened chow. Sham-operated mice underwent identical procedures except for coronary occlusion (no LAD ligation).

WT mice were randomized into 3 groups in part I (sham, MI + adnull, and MI + adFto; n = 6). WT and Anxa1 KO mice were respectively randomized into 3 groups in part II (sham, MI + adnull, and MI + adFto; n = 6). Fto overexpression was achieved in MI mice via intramyocardial injection of a recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 vector (AVV9) encoding Fto (adFto). Both adFto and a control vector (adnull) were purchased from Genechem (Shanghai, China). To ensure sufficient protein overexpression during cardiac I/R injury, intramyocardial delivery of ad vectors (adFto/adnull, 1

Cardiac functional evaluation was performed using a transthoracic echocardiography (RMV-707B; VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada) with a Vevo 2100 high-resolution imaging system (FujiFilm VisualSonics, Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada) equipped with a 40-MHz single-element transducer. Following anesthesia induction via 2% isoflurane, mice were maintained under 0.8–1.5% vaporized isoflurane through a gas anesthesia system. M-mode acquisitions were obtained from parasternal long-axis views at papillary muscle level, with 3 consecutive cardiac cycles recorded for offline analysis. Left ventricular functional indices, including ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening (FS).

Serum samples were obtained through retro-orbital venous plexus puncture under isoflurane anesthesia (2%–3% for induction and 1%–2% for maintenance). Whole blood was processed by centrifugation (3000

Total RNA isolation from heart tissues was conducted with TRIeasyTM total RNA extraction reagent (#10606ES60; Yeasen, Shanghai, China) following standard protocols. First-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was subsequently performed using Hifair® II 1st strand cDNA synthesis kit (#11119ES60; Yeasen, Shanghai, China). Quantitative PCR amplification was achieved with Hieff® qPCR SYBR green master mix (high Rox plus; #11203ES08; Yeasen). Gene expression was quantified using the 2-ΔΔCT method, normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) expression [21]. Amplification by quantitative PCR employed the subsequent primer sets: Gapdh, Forward-5′-CATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGACTG-3′, Reverse-5′-ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAG-3′; Anxa1, Forward-5′-TGTATCCTCGGATGTTGCTGCC-3′, Reverse-5′- CCATTCTCCTGTAAGTACGCGG-3′.

Cardiac tissue homogenization was performed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (#G2002; Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei, China) supplemented with phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (1 mM; #G2008; Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei, China). Prior to electrophoresis, the protein concentration in each sample was measured with a commercial bicinchoninic acid assay kit (#G2026; Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei, China). Equal amounts of lysates were resolved through 10–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, followed by blocking with 5% skim milk/Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20. The membranes were immuno-detected with primary antibodies against Fto, Anxa1, B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2), Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC), cleaved-Caspase 1 (cle-Caspase 1), pro-Caspase 1, Nlrp3, gasdermin D-N-terminal domain (N-Gsdmd), gasdermin D (Gsdmd), and Gapdh. Information on all antibodies is displayed in Supplementary Table 1. After TBST washing, the membranes were probed with a secondary antibody at ambient temperature for 60 min. Protein signals were developed using an enhanced ECL chemiluminescent substrate kit (#36222ES76; Yeasen). Immunoreactive bands were quantified densitometrically using ImageJ software (1.54p; NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), with Gapdh serving as the loading control.

The cardiac tissues were cut into small pieces, homogenized, and centrifuged to get the supernatants (5 min, 5000

Cardiac tissues were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (#E672002; Sangon, Shanghai, China), followed by embedding into paraffin and sectioning at 4 µm intervals. Subsequently, the sections underwent deparaffinization, dehydration via xylene, and ethanol gradient immersion, followed by Masson’s trichrome staining according to standard procedures. Collagen fiber content was analyzed according to the following equation: Collagen fiber (%) = (blue area pixels/total area pixels)

Total RNA samples prepared with TRIzol extraction reagent were subjected to m6A quantification via the m6A RNA methylation quantification kit (#P-9005; Epigentek, Flushing, NY, USA). RNA aliquots (200 ng/sample) were sequentially incubated with capture antibody, detection antibody, enhancer solution, and chromogenic substrate in 96-well plates. Absorbance values at 450 nm were measured with a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), where experimental values were derived from established standard curve calculations.

Total RNA from left ventricles was extracted with TRIzol and treated with DNase I. m6A RNA immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed using an anti-m6A antibody with species-matched IgG as a negative control according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Information on all antibodies is displayed in Supplementary Table 1. After IP, RNA was purified, reverse-transcribed, and qPCR was carried out for Anxa1. Enrichment was quantified as % input and as fold over IgG.

Paraffin-embedded cardiac tissues were sectioned into 4 µm sections for IHC analysis with a 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) detection system. Endogenous peroxidase was inactivated by sequential deparaffinization, rehydration, and 15-min incubation in 3% H2O2-methanol solution, followed by 20-min antigen retrieval at 95 °C. Tissue sections were treated overnight at 4 °C with anti-Nlrp3 primary antibody (#D261589; at 1:25 dilution; Sangon, Shanghai, China), followed by 30-min incubation with a secondary antibody (#D110073; at 1:1000 dilution; Sangon, Shanghai, China). Reaction products were visualized after counterstaining with the ultra-sensitive horseradish the catalase DAB color kit (#C510023; Sangon, Shanghai, China). Images were captured at 100

Experimental results are presented as mean

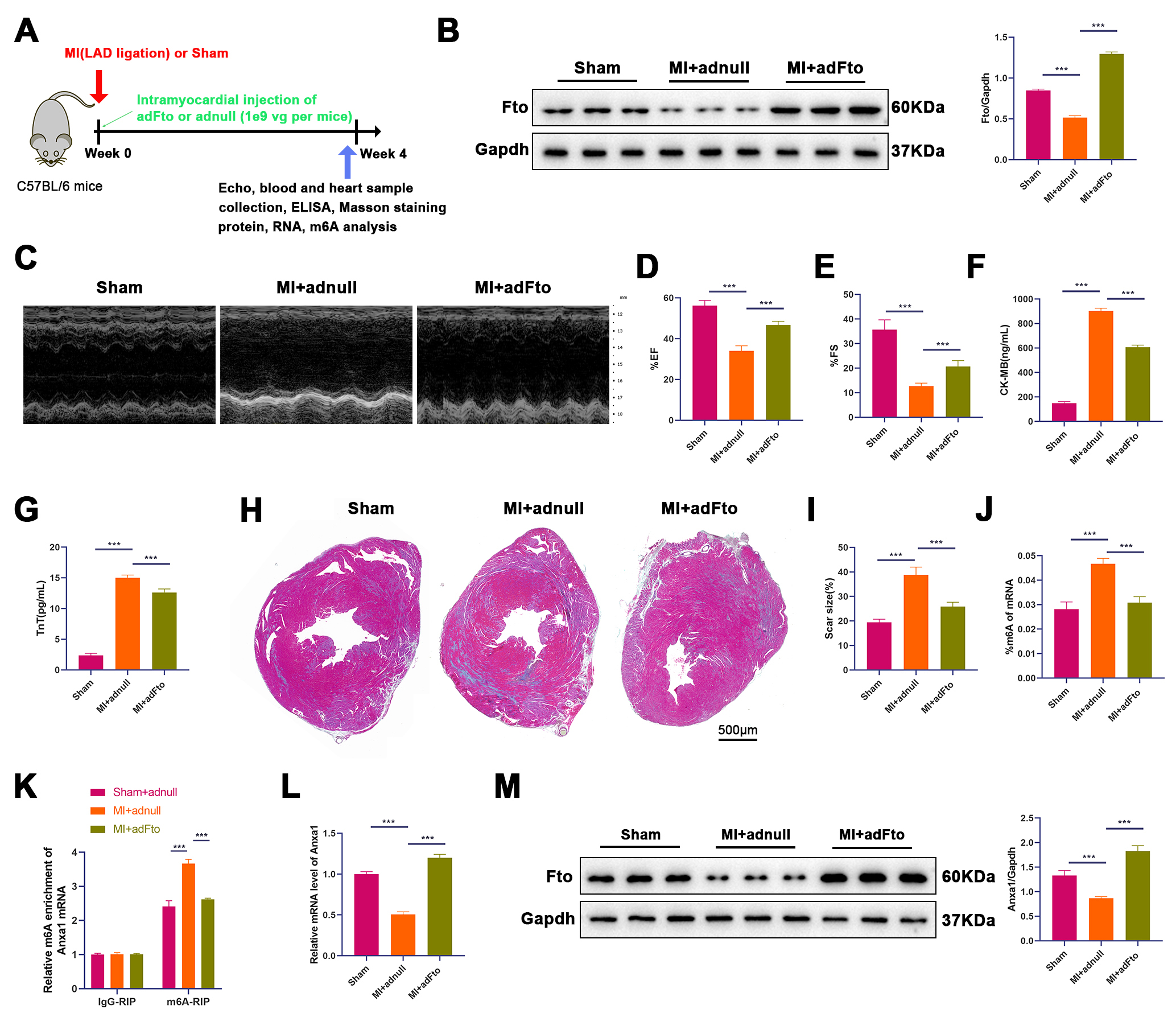

To verify that Fto-mediated m6A demethylation of Anxa1 mitigates cardiac I/R injury in vivo, we injected adFto or adnull intramyocardially in mice, followed by performing the MI surgery and reperfusion (Fig. 1A). Changes in Fto protein levels were detected in heart samples. As expected, MI mouse-derived heart samples possessed lower Fto protein levels than those from sham mice, and administration of adFto increased Fto protein levels in heart samples from MI mice (Fig. 1B). Cardiac function was assessed by Echo, as displayed in Fig. 1C. We observed significant reductions in both EF (56.17% vs. 34.00%, p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Fto overexpression alleviates cardiac I/R injury and enhances Anxa1 expression in mouse models. (A) Experimental strategy in mouse models with MI. Mice underwent LAD occlusion for 30 min after intramyocardial injection of adFto or adnull (1

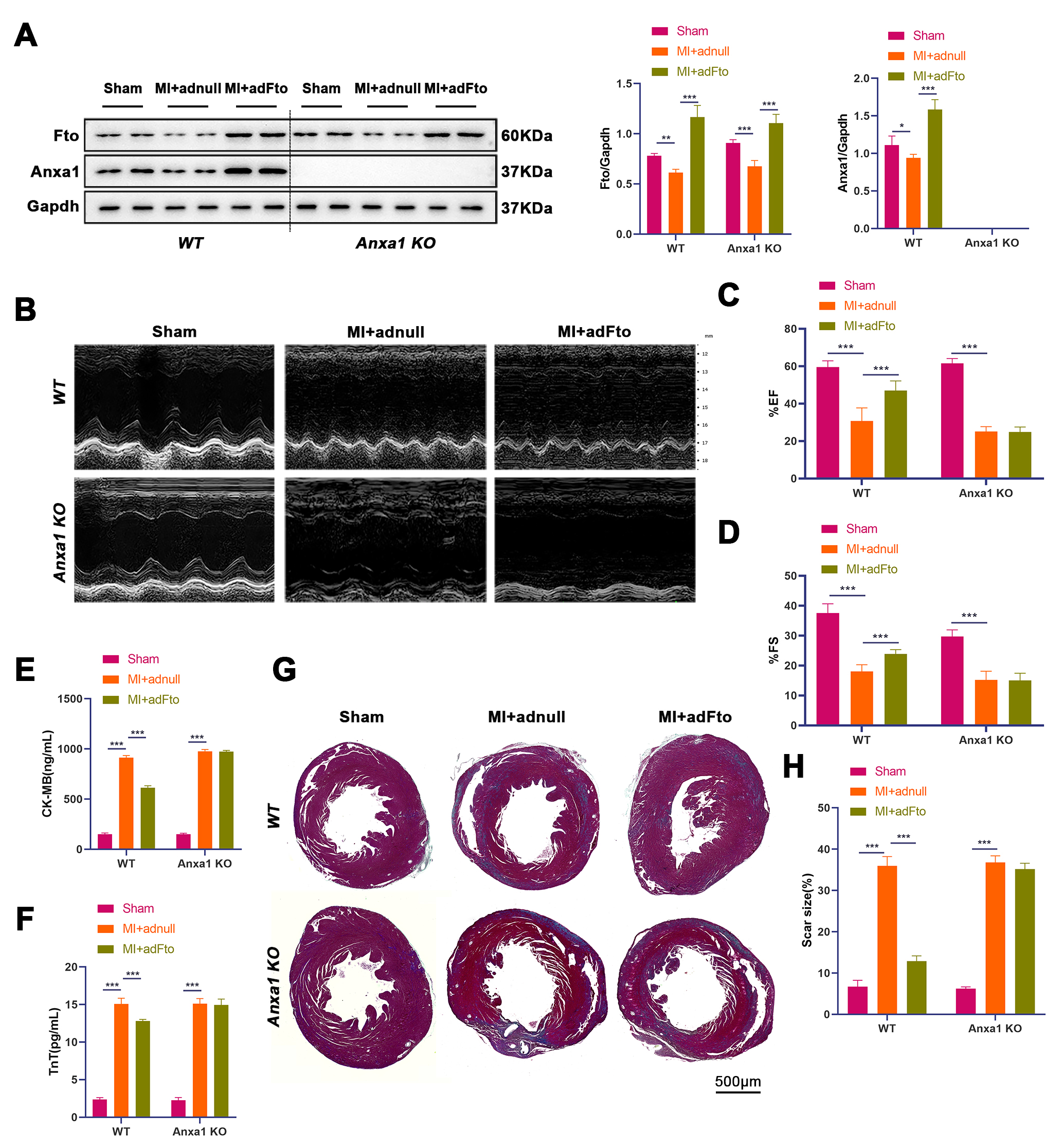

To identify that Fto exerts cardioprotective effects by up-regulating Anxa1, we constructed MI models after adFto or adnull administration using WT or Anxa1 KO mice, followed by reperfusion. Briefly, a 2

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Fto mediates Anxa1 expression against cardiac I/R injury. After intramyocardial injection of adFto or adnull (1

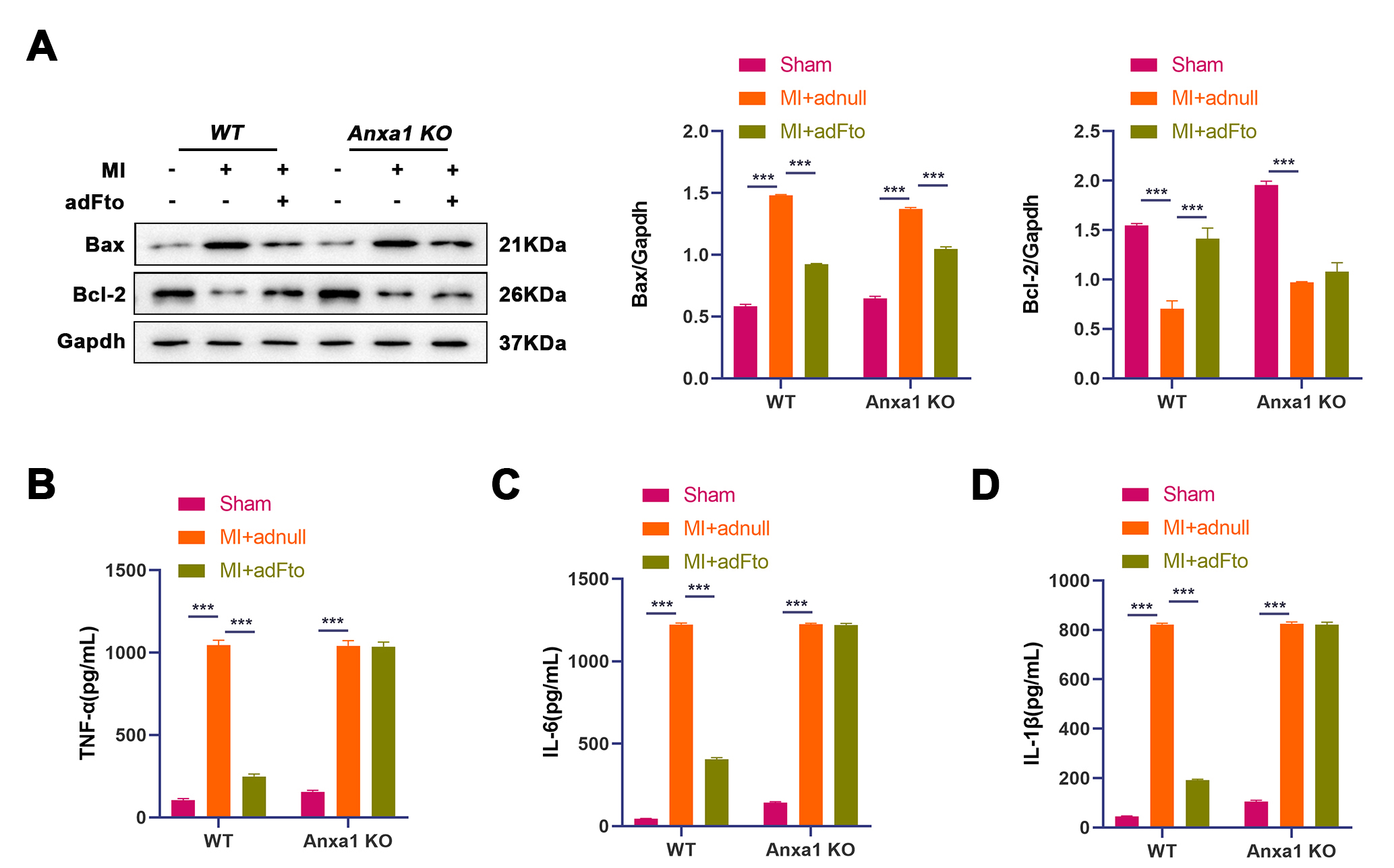

Given the pathological significance of apoptosis and inflammation in cardiac I/R injury after MI, we proceeded to analyze whether Fto exerts its effects on cardiac tissue apoptosis and inflammation via Anxa1. The results showed that cardiac samples from WT and Anxa1 KO mice exhibited higher Bax protein levels and lower Bcl-2 protein levels after MI (p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Fto reduces cardiac apoptosis and inflammation via elevating Anxa1 expression post-MI. (A) Protein levels of Bax and Bcl-2 in heart samples were detected by western blot (n = 3). (B–D) The levels of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-

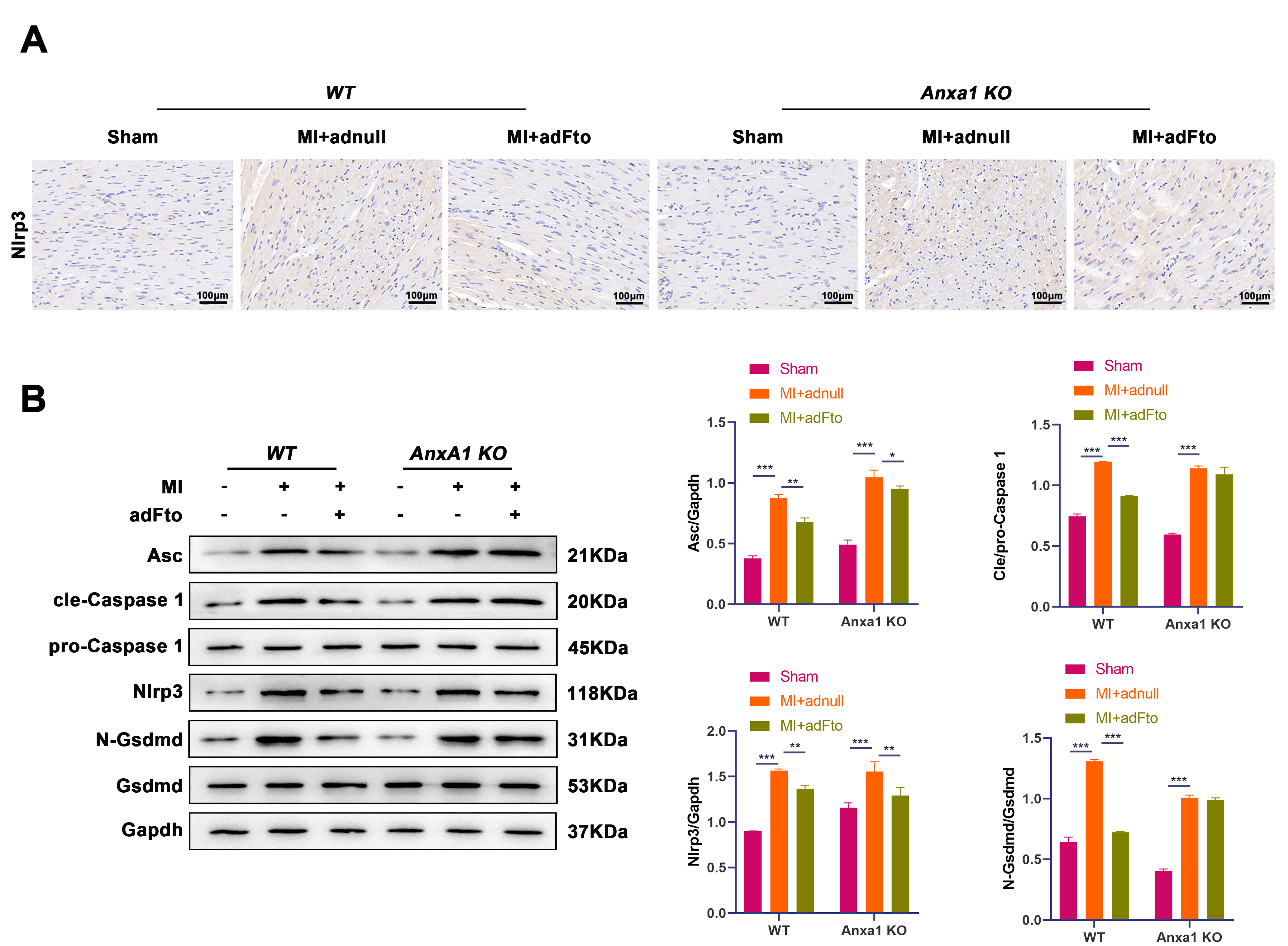

To verify the effect of the Fto/Anxa1 axis on cardiac Nlrp3 activation and pyroptosis, we detected NLRP3 protein levels by IHC staining. As shown in Fig. 4A, Nlrp3 protein levels were higher in WT and Anxa1 KO mouse-derived heart samples post-MI, yet Fto overexpression reduced Nlrp3 protein levels in WT mice but not in Anxa1 KO mice. Additionally, higher protein levels of ASC, cleaved caspase-1/pro caspase-1 ratio, Nlrp3, and N-Gsdmd/Gsdmd were observed in heart samples of WT and Anxa1 KO mice with MI (p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Fto represses Nlrp3-mediated pyroptosis in the heart following MI through Anxa1. (A) IHC staining was conducted to detect Nlrp3 protein levels in heart samples from different groups. Scale bar: 100 µm. (B) Protein levels of ASC, cleaved caspase-1/pro caspase-1 ratio, Nlrp3, and N-Gsdmd/Gsdmd in heart samples were evaluated by western blot. Data are shown as mean

The present study first demonstrated in vivo that Anxa1 demethylation mediated by Fto-dependent demethylation of Anxa1 is associated with attenuation of Nlrp3 inflammasome activity and protection against myocardial I/R injury. These findings corroborate our previous in vitro observations and extend them to an intact physiological context, highlighting RNA methylation as a viable target for cardio-protection. From a translational standpoint, our findings align with broader cardioprotective and remodeling strategies; for instance, sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors have been linked to progenitor-cell modulation and favorable remodeling, offering convergent avenues to augment myocardial repair [22].

Currently, LAD ligation is an established method for establishing animal models of acute MI both at home and abroad. Among the various animal species used for modeling myocardial I/R injury, mice have become the most frequently employed due to their low cost and the availability of transgenic and knockout strains [23]. It has been demonstrated that irreversible myocardial damage occurs when ligation exceeds 30 min, while reperfusion for 1 to 24 h met the modelling criteria [24]. This study applied WT and Anxa1 KO mice with a C57BL/6 background to construct cardiac I/R injury models, with ligation for 30 min and reperfusion for 2 h.

Fto, a key demethylase in the m6A system, plays a protective role in protecting against cardiac I/R injury. A prior study reported that Fto mRNA and protein levels were decreased significantly in ischemic aged hearts, indicating age-related differences in m6A regulation during cardiac I/R injury [25]. It was reported that down-regulation of Fto results in decreased Myc expression, enabling enhanced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and oxidative stress in hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R)-induced cell models [26]. Ke et al. [27] demonstrated that Fto overexpression attenuates H/R-induced cardiomyocyte injury by suppressing cardiomyocyte apoptosis and inflammatory responses via removing the methylation modification of Yap1 mRNA. Consistent with previous studies [13, 27], our findings also demonstrated that Fto ameliorated cardiac I/R injury, as evidenced by elevated left ventricular FS and EF values, reduced serum TnT and CK-MB levels, and improved cardiac fibrosis following Fto overexpression. These findings emphasize the crucial role of Fto in protecting against cardiac injury.

Anxa1 exhibits cardioprotective effects in cardiac injury. Singh et al. [28] suggested that Anxa1 KO mice exhibit higher blood pressure than normal mice regardless of age, accompanied by cardiac dysfunction and cardiac hypertrophy, emphasizing the key role of Anxa1 in regulating blood pressure, cardiovascular function and cardiac aging. Qi et al. [29] discovered that the activation of the Anxa1/G-protein coupled receptor formyl peptide receptor 2 axis can restrain neutrophil extracellular traps, thereby alleviating MI in rat models. F-box-only protein 32 exacerbates cardiac injury via mediating Anxa1 ubiquitination and repressing the phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling [30]. Anxa1 small peptide prevents cardiomyocyte injury evoked by lipopolysaccharide via inhibition of ferroptosis-induced cell death, relying on sirtuin 3-dependent p53 deacetylation [31]. Here, we observed that exogenous expression of Fto weakened the increase in m6A levels in MI mouse-derived heart tissues, along with a significant elevation in Anxa1 mRNA and protein levels, implying that Fto may improve cardiac I/R injury by mediating Anxa1 expression in mouse models. As in WT mice, Anxa1 KO mice subjected to MI possessed a marked decrease in EF and FS values, a sharp rise in serum CK-MB and cTnT levels, and an obvious elevation in collagen fibers, whereas Fto overexpression improved these parameters in WT mice but was ineffective in Anxa1-knockout mice, manifesting that Fto may protect against cardiac I/R injury post-MI by increasing Anxa1 expression.

Mechanistically, myocardial I/R injury is characterized by a complex interplay of cardiomyocyte apoptosis, inflammatory cascade responses, and Nlrp3 inflammasome activation [32]. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis arises due to hypoxia, metabolic disturbances, and oxidative stress during myocardial I/R injury [33]. The release of cellular contents activates the immune system, triggering an inflammatory cascade that releases pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the experiments were performed in young and healthy mice, which do not fully capture the molecular complexity and comorbid heterogeneity present in clinical MI, where conditions such as diabetes and hypertension are prevalent. Second, the study used a fixed ischemia duration, a prespecified acute 2-h reperfusion window, and a single adFto dose; accordingly, it does not establish temporal dynamics or dose–response relationships. Third, the specific m6A site of Fto-mediated Anxa1 demethylation has not been clarified. Future studies will extend the reperfusion window (e.g., 24–72 h and 7–28 d) and perform dose-ranging to delineate the time course and exposure–response characteristics of the Fto–Anxa1 axis and its relation to Nlrp3 signaling, and identify the key m6A modification sites on Anxa1 mRNA and evaluate the robustness of the Fto/Anxa1 regulatory axis in db/db mice or aging models to enhance translational relevance.

Fto-mediated demethylation of Anxa1 alleviates myocardial I/R injury with Nlrp3 inflammasome suppression. Taken together, these in vivo data position the Fto-Anxa1 axis as a major mechanistic contributor to protection against I/R and a promising target for future intervention.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

CJH, HJY and HLH designed experiments. HJY, LJX and HZ carried out experiments, analyzed experimental results. CJH and HJY wrote the manuscript. HLH revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All experimental procedures involving animals were undertaken in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines and received approval from the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jiaxing University Medical College (Approval No. JUMC2021-095).

Not applicable.

This work was supported by Jiaxing Science and Technology Program (2023AY40029); Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LQ23H020001; National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82300363); Zhejiang Province Clinical Key Specialty Construction Project (2024-ZJZK-001) and Jiaxing Clinical Key Specialty Construction Project (2023-JXZK-001).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL42765.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.