1 Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, University of Naples “Federico II”, 80131 Naples, Italy

Abstract

The deiodinase enzymes are the gatekeepers of the peripheral Thyroid Hormone (TH) metabolism since they catalyze the activation of the prohormone Thyroxine (T4) into the active Triiodothyronine (T3), as well as their inactivation into metabolically inactive forms. Type I and Type II Deiodinases, Type I Deiodinase (D1) and D2, respectively, catalyze the T4-to-T3 conversion, while Type III Deiodinase, D3, terminates the THs action converting T4 into reverse T3 (rT3) and T3 into T2. Deiodinases are sensitive rate-limiting components within the hormonal axis and their enzymatic dysregulation is a common occurrence in several pathological conditions, including cancer. As a result, these enzymes are a potential source of interest for the development of pharmacological compounds exhibiting modulatory effects. The current arsenal of inhibitors for these enzymes is still limited. To date, a significant challenge in the development of deiodinases’ inhibitors is the achievement of enzyme selectivity and tissue specificity without disrupting TH regulation in the surrounding healthy tissues. Furthermore, deiodinases were shown to be potent regulators of the neoplastic processes, and their expression is altered in tumors, predisposing to increased aggressiveness and progression toward metastasis. However, especially in the cancer context, this design is complicated by the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of deiodinases expression, expressed as inter-tumoral variability across different cancer types, intra-tumoral variability among distinct tumor regions or cell populations within the same tumor type, and dynamic changes over time. Nevertheless, deiodinases’ inhibitors hold promise as a novel class of cancer therapeutics. Here, we proposed an overview of the actual knowledge of deiodinases’ inhibitors, highlighting their potentials and limitations. Future research should focus on identifying the most effective inhibitors, refining delivery mechanisms, and optimizing treatment regimens to minimize side effects while maximizing therapeutic efficacy.

Keywords

- Thyroid Hormones

- deiodinases

- deiodinases’s inhibitors

The thyroid is an essential component of the endocrine system that manages various bodily functions such as metabolism, growth, and development through the production of Thyroid Hormones (THs). The two main hormones it secretes are Thyroxine (T4) and Triiodothyronine (T3) both of which are subject to central and peripheral regulation mechanisms [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. The central regulation of THs production is orchestrated by the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis, a sophisticated neuroendocrine network that maintains metabolic homeostasis through a variety of hormonal feedback loops [6, 7]. Beyond the central regulation, a peripheral regulation of THs occur in target tissues, aligning TH activity with tissue-specific demands, independently of the HPT axis and circulating hormone levels [8]. This local regulation allows tissues to fine-tune THs action according to their metabolic and developmental needs, ensuring organ-specific homeostasis. The main well-characterized peripheral regulatory mechanisms involve (i) the Thyroid Hormone Receptors (TRs), namely TR

In the context of TH signaling, existing literature makes a distinction between different ways for THs signaling. This complex mode of operation has often led to ambiguities in the classification. Recognizing this, Flamant et al. [21] proposed a more nuanced nomenclature, delineating four distinct types of TH signaling pathways to provide greater clarity and foster advancements in research. The refined classification includes:

(i) Type 1: the classical pathway where liganded TRs directly bind to DNA at Thyroid Hormone Response Elements (TREs), modulating gene transcription.

(ⅱ) Type 2: liganded TRs influence gene expression indirectly by tethering to other DNA-bound transcription factors, without directly binding to TREs.

(ⅲ) Type 3: unliganded TRs repress gene transcription by recruiting corepressor complexes to TREs, thereby inhibiting gene expression in the absence of hormone.

(ⅳ) Type 4: non-genomic actions where THs interact with receptors located in the cytoplasm or at the plasma membrane, activating various intracellular signaling cascades independent of direct gene transcription.

It is generally assumed that THs exert many of their biological effects through canonical Type 1-to-Type 3 pathways, also referred as genomic pathways, which involve direct regulation of gene expression via nuclear receptors [21, 22]. However, beyond the canonical genomic pathways, THs act also through alternative non-genomic routes, including membrane-mediated effects with emerging relevance in pathological contexts such as cancer [4, 21, 23, 24]. Although “canonical” implies direct nuclear action, many responses attributed to Type 4 pathways may involve cross-talk with cytoplasmic signaling cascades, blurring the line between nuclear and non-nuclear effects. This conventional dichotomy different pathways has proven insufficient to encapsulate the complexity of TH actions.

While peripheral regulation provides an elegant and flexible system to tailor TH action to local needs, it also complicates the assessment and treatment of thyroid-related disorders, since serum T3 and T4 levels may not accurately reflect tissue-specific TH status. This raises important clinical implications: therapeutic strategies targeting deiodinases or transporters might be necessary in specific contexts, moving beyond traditional systemic hormone replacement. The manipulation of deiodinases’ activity, particularly using selective inhibitors, has become an intriguing and increasingly relevant research area of interest in clinical application. Deiodinases’ inhibitors have been studied across a broad spectrum of medical fields, primarily in the context of thyroid function regulation, but their implications extend to a variety of medical conditions and research areas, including cancer, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular and neurological conditions and Thyroid Hormone Resistance syndrome [25, 26, 27, 28]. In certain medical conditions, the use of deiodinases’ inhibitors has gained attention as possible therapeutic options, primarily due to their ability to modify TH activity by blocking enzyme function, but their potential applications in clinical settings must be critically examined, making a careful and thoughtful evaluation of their benefits and risks.

Recognized deiodinases’ inhibitors include Iopanoic Acid (IOP), Propylthiouracil (PTU), and Amiodarone [29, 30, 31]. Methimazole (MMI), on the other hand, while not being a deiodinases’ inhibitor, represents a potent anti-thyroid compound as it inhibits TH synthesis by interfering with the iodination of tyrosine residues in thyroglobulin, a mechanism well established in both clinical and experimental studies [32, 33].

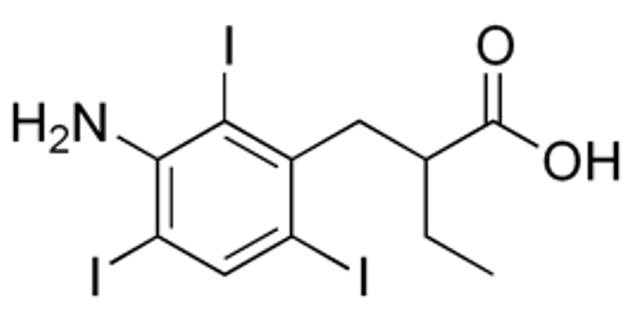

Iopanoic acid is a iodine-containing radiocontrast agent that has been widely studied for its competitive inhibitory effects on both D1 and D2 interfering with their catalytic activity [31, 34]. By binding to the enzyme’s active site, IOP prevents the deiodination of T4 leading to decreased peripheral T4-to-T3 conversion and increased serum levels of T4 and rT3. Although IOP was historically used in the treatment of thyrotoxicosis to rapidly reduce serum T3 levels, due to its adverse effects and the availability of safer alternatives, it is no longer commonly used in clinical practice but remains useful in experimental models for transient inhibition of TH activation [35].

PTU and Methimazole, both thionamide drugs, are well-known for their role in treating hyperthyroidism, particularly conditions like Graves’ disease. PTU, for instance, has been historically favored for its potent and selective inhibition of D1 activity which, mediating the T4-to-T3 conversion, lowers circulating T3 levels [36, 37, 38]. While effective for treating hyperthyroidism, PTU is associated with significant side effects, such as liver toxicity and agranulocytosis, which have limited its clinical use in favor of MMI [39, 40, 41, 42, 43]. As antithyroid medication used to treat hyperthyroidism, the Methimazole’ primary action is carried out on the inhibition of Thyroid Peroxidase (TPO), the enzyme responsible for the incorporation of iodine into thyroglobulin and the synthesis of THs. Thus, while it is generally preferred over PTU due to its lower risk of liver toxicity, the use of MMI in pregnancy is carefully considered, due to its capability to cross the placental barrier, posing risks of neurodevelopmental interference and teratogenic effects, including congenital malformations [44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50].

Amiodarone, on the other hand, is an antiarrhythmic drug able to interfere with TH metabolism with a complex and multifaceted mechanism of action due to its unspecific ability to interfere with the activity of all three deiodinases. Amiodarone is known to strongly inhibit D1 in the liver, decreasing circulating levels of T3 and leading to a condition known as low T3 syndrome, whose effects are especially notable in the liver, where D1 activity is crucial for regulating THs levels and ensuring proper metabolic function [51]. Amiodarone also inhibits D2, responsible for T4-to-T3 conversion in tissues such as the pituitary gland and brain [52]. This further contributes to decreased local T3 levels, which can interfere with the feedback mechanisms in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis, affecting TSH secretion [53]. Finally, Amiodarone may also inhibit D3, increasing the rT3 levels, further complicating THs dynamics [54]. Overall, Amiodarone’s function as a deiodinases’ inhibitor has profound dangerous consequences: while being highly effective in controlling cardiac arrhythmias, its impact on TH metabolism can lead to significant and sometimes severe thyroid dysfunction, as well as amiodarone-induced hypothyroidism and amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism, both of which are linked to alterations in TH signaling due to the unspecific deiodinases’ inhibition.

Critically, the use of PTU and MMI as anti-thyroid compounds in clinical practice highlights the challenges and risks of interfering with TH metabolism [55]. While they offer valuable therapeutic effects in the management of specific thyroid conditions, their use as deiodinases’ inhibitors requires a clinically careful and risk-aware approach to ensure the short-term benefits outweigh the long-term possible drawbacks.

Last but not least, Propranolol, a non-selective

Deiodinases critically modulate intracellular TH signaling, thereby influencing cell proliferation, metabolism, and survival. Dysregulation of deiodinases has been observed in a range of malignancies and is increasingly recognized as a contributor to tumor growth and progression. Several studies have demonstrated that altered expression of D2 and D3 contributes to tumor progression and aggressiveness by reshaping local TH signaling.

While D3 expression is highly prominent during embryonic development, its presence in adult tissues is not negligible. In fact, several adult cell types, including parenchymal, epithelial, and immune cells, retain or modulate D3 expression in response to metabolic, physiological, and pathophysiological stimuli [57, 58]. Notably, D3 is constitutively expressed in the adult human brain, where it plays a critical role in maintaining local THs homeostasis essential for proper neuronal function [59, 60, 61, 62]. Furthermore, D3 expression is essential for female reproductive function, especially in the ovary and placenta, where it regulates the fine balance of THs during pregnancy [63, 64, 65]. Similarly, activated immune cells modulate D3 activity as part of their adaptive response to inflammation and cellular stress [66, 67]. Beyond these physiological roles, aberrant overexpression of D3 has been reported in specific cancer types, such as Basal Cell Carcinoma [68, 69, 70, 71], colorectal cancer [72] and infantile hemangiomas [73, 74], where it contributes to a localized hypothyroid state that promotes tumorigenesis.

Although D2 is generally associated with differentiation and energy expenditure [75, 76], its upregulation in follicular, anaplastic and medullary thyroid cancer [77, 78], pituitary tumors and brain gliomas [79, 80], skin cancer [81], endometrial cancer [82], supports the idea that D2 may, in specific contexts, promote oncogenic programs by increasing intracellular T3 availability.

Research is exploring the potential of deiodinases’ inhibitors in cancer therapy, a field of broad interest due to the often-aberrant expression of deiodinases in many human tumors [83, 84]. Some studies suggest that inhibiting deiodinases could help slow the growth of certain cancer cells by affecting their metabolism and TH regulation [85, 86]. In this context, selective D2 and D3 inhibitors are currently a focus of ongoing research due to their potential to target specific metabolic changes in cancer cells. Different cancer types exhibit a higher D2 activity compared to the non-tumoral counterpart, leading to enhanced intratumoral T3 levels, which can both affect tumor growth and promote metastasis [81, 82, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92]. For instance, in high D2 expressing tumors, the use of D2 selective inhibitors focused on the specific blockage of D2 activity, would be an ideal therapeutic approach. By blocking, or at least reducing, the intratumoral T4-to-T3 conversion, D2 inhibition could lower the amount of active hormone in tumor tissues. As a result, this hormonal reduction may help slow down tumor cell growth and induce cancer cell death. Otherwise, in high D3 levels tumors, where the D3 selective inhibition could reduce the catabolism of T3 to inactive forms, thus maintaining higher levels of T3 and promoting apoptosis in cancer cells [68, 69].

Non-selective deiodinase inhibitors, while effective in blocking deiodinases’ activity, may have off-target effects and disrupt normal thyroid function, leading to multiple side effects. Therefore, selective deiodinases’ inhibitors are of particular interest in cancer therapy. Since D2 overexpression has been associated with tumor progression and resistance to treatment in several cancers [81, 89, 90], D2 inhibition holds promise in restoring a physiological TH signaling and potentially arrest tumor growth and progression toward invasiveness. However, selective D2 inhibitors are still under active investigation, and as of now, there are no established compounds in clinical use for cancer treatment.

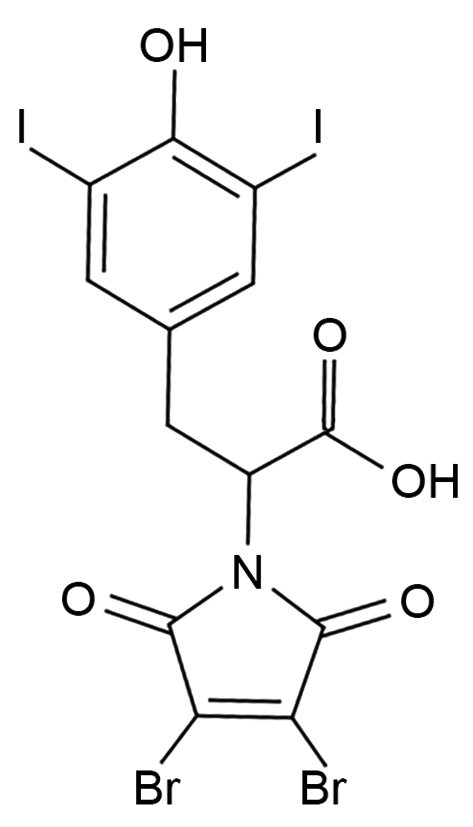

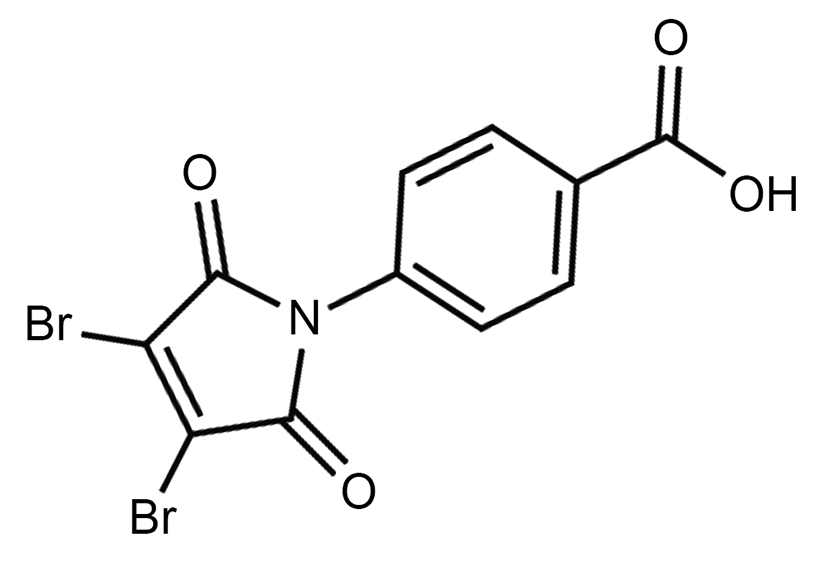

This also applies to D3, whose inhibitors remain in the research phase. Although no D3 inhibitors have yet reached clinical application, some promising molecules have been explored in preclinical studies. For instance, Moskovich et al. [93] developed new anti-D3 compounds based on a dibromomaleic anhydride (DBRMD) core structure and demonstrated their efficacy in in vitro and in vivo experimental settings, using ovarian cancer cell lines and xenograft mouse models, respectively. Two notable compounds, PBENZ-DBRMD and ITYR-DBRMD, were validated as effective D3 inhibitors in ovarian cancer context. In detail, these compounds, by binding to the D3 active site, prevent the enzyme from converting active hormones into their inactive forms. This inhibition leads to an increase in active THs levels within the tumor microenvironment, inducing on one hand the growth arrest of ovarian cancer cells and on the other the activation of tumor-suppressive pathways, such as apoptotic pathways [93].

Although both in vitro and in vivo preclinical studies have demonstrated encouraging effects for the newly identified D3 inhibitors in ovarian cancer therapy, clinical validation remains pending. Much of the research is still in the early stages, and more clinical trials are needed to assess the safety, efficacy, and potential side effects of D2 and D3 inhibitors in humans.

Despite the biological relevance of deiodinases in TH homeostasis, the discovery of specific inhibitors for this class of enzymes remains remarkably slow due to several factors, such as (i) methodological limitations (lack of rationally designed chemical libraries targeting selenoenzymes), (ii) structural knowledge gaps (absence of high-resolution crystallographic structures of deiodinases, hindering structure-based drug design approaches) and (iii) predominant focus on non-specific environmental endocrine disruptors or T3/T4 analogues rather than true enzymatic inhibitors.

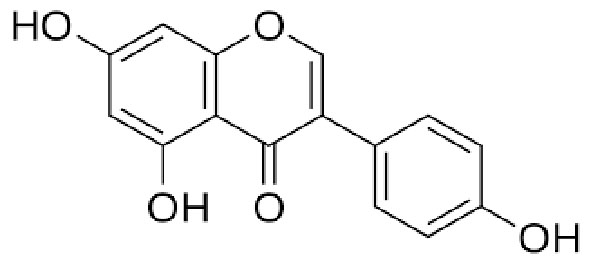

Although it is an area of great interest, the identification of deiodinases’ inhibitors has been hindered by the lack of reliable and non-radioactive screening methods. Conventional approaches often involve radioactive substrates, which are not ideal due to concerns over safety, cost, and the environmental impact. Therefore, the development of non-radioactive, high-throughput screening methods has been a major step forward in this research area, as it allows for more efficient, safe, and sustainable discovery of potential deiodinase inhibitors. A notable study by Renko et al. [94] provided an accurate and efficient proof-of-concept method of screening large compound libraries for potential deiodinases’ inhibitors, by using a modified assay system that leverages alternative technologies like fluorescent or colorimetric detection. More specifically, the researchers developed a non-radioactive screening method utilizing the Sandell-Kolthoff reaction to detect iodide release from substrate molecules and employing recombinant human deiodinases, enabling the assessment of D1, D2, and D3 activities confirmed via Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). This development marks a significant improvement over previous methods, enabling researchers to explore a wider variety of compounds and potential inhibitors, facilitating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents for thyroid disorders. The authors identified Genistein and Xanthohumol as potent inhibitors of deiodinases in vitro, suggesting that these molecules, interfering with the enzymes’s active site or altering the enzymes’ conformation, may influence TH metabolism. In detail, while Genistein, a naturally occurring isoflavone, was identified as a specific inhibitor of DIO1, Xanthohumol, a prenylated flavonoid found in hops, was found to potently inhibit all three deiodinase isoenzymes [94]. This study is part of a broader effort to identify and develop inhibitors of iodothyronine deiodinases. Indeed, Jennifer H Olker et al. [95], developed a comprehensive in vitro screening of over 1800 chemicals from the from the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA)’s ToxCast phase 1_v2, phase 2, and e1k libraries to identify inhibitors of human iodothyronine deiodinases. After an initial screening (single concentration dose experiments), a quarter of all chemicals exhibited

Another significant limitation lies in the widespread use of chemical libraries, such as in the ToxCast Phase 1 screening, that were not designed to target the unique structural features of selenoproteins like D1, often yielding weak, non-selective inhibitors with limited therapeutic potential [96]. Furthermore, as shown in a recent study by Sigmund J Degitz et al. [97], much of the current research is skewed toward identifying environmental disruptors rather than rationally designed inhibitory molecules. While valuable for toxicology, these approaches provide little mechanistic insight into selective enzyme inhibition. Additionally, studies on TH analogues tend to prioritize nuclear receptor modulation over enzymatic inhibition, reflecting a long-standing bias in thyroid pharmacology [98]. Finally, although certain inorganic substances, such as gold ions and nanoparticles, can inhibit deiodinase activity in vitro, these effects are generally mediated through redox interference with the enzyme’s selenocysteine-containing active site, an interaction that lacks specificity and raises concerns regarding cytotoxicity and clinical translation [99].

Recent advances have aimed to overcome longstanding methodological barriers in the discovery of isoenzyme-selective deiodinase inhibitors. A notable contribution in this regard is the development of a non-radioactive high-throughput screening platform for DIO1 inhibitors, which allowed the identification of highly potent and selective molecules with submicromolar IC50 values against D1 while sparing D2 and D3 activities. This method, relying on colorimetric detection of iodide release, significantly improves safety, scalability, and throughput over traditional radiolabeled assays, and represents a promising tool for early-phase compound prioritization [100].

Complementary to this, a comprehensive bioactivity data integration approach has been proposed to prioritize chemicals identified as potential in vitro deiodinase inhibitors, evaluating their relevance in the context of in vivo TH disruption. This prioritization strategy incorporates toxicokinetic modeling and high-throughput toxicology data to inform risk-based chemical assessment, providing a framework to translate in vitro inhibitory potential to realistic biological exposures [101].

In parallel, in recent years, scientists have explored the possibility of using existing drugs as potential D2 inhibitors. A study by Sagliocchi et al. [102], through an in silico docking screening of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs, identified the Cefuroxime, a second-generation cephalosporin antibiotic, as a potential D2 inhibitor. Experimental in vitro and in vivo validations demonstrated Cefuroxime specificity in the inhibition of D2 enzymatic activity without affecting D1 and D3 enzymes, and the ability of lowering THs levels in a tissue-specific manner, without altering overall THs levels. Despite these remarkable findings, the clinical application of Cefuroxime as a specific D2 inhibitor remains speculative at this point. Much more investigations are needed to fully understand the extent and significance of Cefuroxime’s inhibition of D2 and its broader effects on thyroid function. For instance, research is needed to examine long-term effects of Cefuroxime on TH metabolism, particularly in patients with preexisting thyroid conditions or those undergoing prolonged treatment.

In conclusion, considering the possible wide application of deiodinases’ inhibitors in different therapeutic areas (Table 1, Ref. [31, 55, 56, 93, 94, 95, 103, 104, 105]), there is an urgent need to identify and develop more specific deiodinase inhibitors that can selectively target the various isoforms of deiodinases without affecting other metabolic pathways. Such advancements would allow for more precise regulation of THs levels, overcoming the implications linked to the lack of specificity and potentially leading to better therapeutic outcomes with reduced side effects. To date the development of more selective and tissue-specific inhibitors remains a significant challenge. Identifying new, highly specific deiodinases’ inhibitors could significantly improve treatment options for thyroid-related disorders and contribute to a more personalized approach to managing endocrine diseases. Chemical structures were drawn using ChemDraw (PerkinElmer) software.

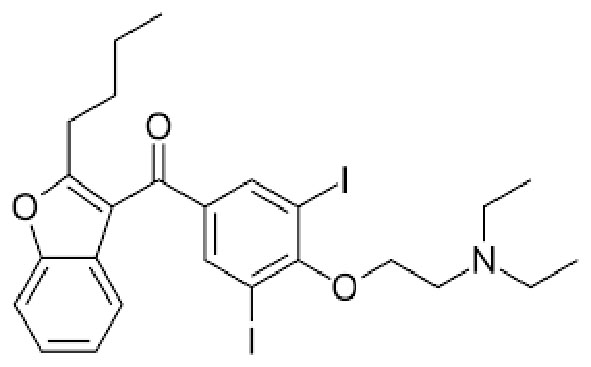

| Structure | Compound | |

| Name | AMIODARONE |

| International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) | (2-{4-[(2-butyl-1-benzofuran-3-yl)carbonyl]-2,6-diiodophenoxy}ethyl)diethylamine | |

| Formula | C25H29I2NO3 | |

| Chemical Abstracts Service number (CAS) number | 19774-82-4 | |

| Specificity | Type I Deiodinase (D1), Type II Deiodinase (D2) and Type III Deiodinase (D3) | |

| Hamilton D Sr et al. [103], Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2020 “Amiodarone: A Comprehensive Guide for Clinicians” doi: 10.1007/s40256-020-00401-5. PMID: 32166725 | ||

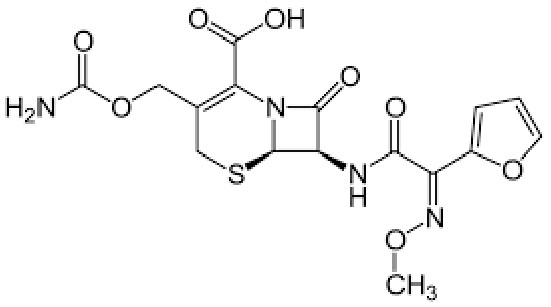

| Name | CEFUROXIME |

| IUPAC | (6R,7R)-3-(carbamoyloxymethyl)-7-[[(2Z)-2-(furan-2-yl)-2-methoxyiminoacetyl]amino]-8-oxo-5-thia-1-azabicyclo[4.2.0]oct-2-ene-2-carboxylic acid | |

| Formula | C16H16N4O8S | |

| CAS number | 55268-75-2 | |

| Specificity | Type II Deiodinase (D2) | |

| Scott LJ et al. [104], Drugs. 2001 “Cefuroxime axetil: an updated review of its use in the management of bacterial infections” doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161100-00008. PMID: 11558834. | ||

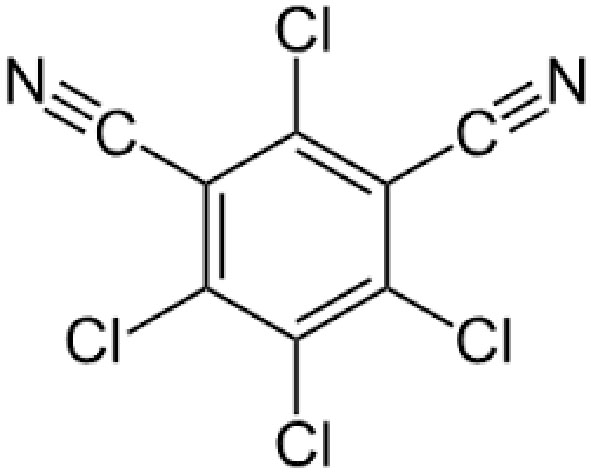

| Name | CHLOROTHALONIL |

| IUPAC | 2,4,5,6-tetrachlorobenzene-1,3-dicarbonitrile | |

| Formula | C8Cl4N2 | |

| CAS number | 1897-45-6 | |

| Specificity | Type III Deiodinase (D3) | |

| Olker JH. et al. [95], Toxicol Sci. 2019 “Screening the ToxCast Phase 1, Phase 2, and e1k Chemical Libraries for Inhibitors of Iodothyronine Deiodinases” doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfy302. PMID: 30561685. | ||

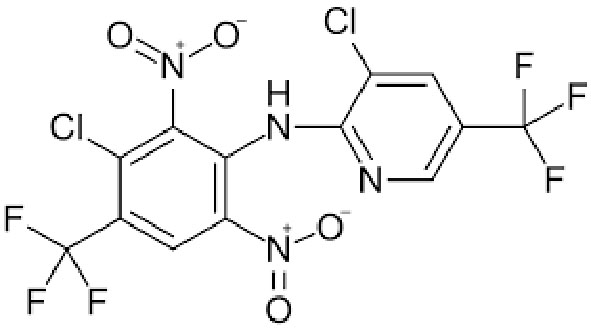

| Name | FLUAZINAM |

| IUPAC | 3-chloro-N-[3-chloro-2,6-dinitro-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-5-(trifluoromethyl)pyridin-2-amine | |

| Formula | C13H4Cl2F6N4O4 | |

| CAS number | 79622-59-6 | |

| Specificity | Type II Deiodinase (D2) | |

| Olker JH. et al. [95], Toxicol Sci. 2019 “Screening the ToxCast Phase 1, Phase 2, and e1k Chemical Libraries for Inhibitors of Iodothyronine Deiodinases” doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfy302. PMID: 30561685. | ||

| Name | GENISTEIN |

| IUPAC | 5-hydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-7-[(2S,4S,5S)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]oxychromen-4-one | |

| Formula | C21H20O10 | |

| CAS number | 446-72-0 | |

| Specificity | Type I Deiodinase (D1) | |

| Sharifi-Rad J. et al. [105], Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021 “Genistein: An Integrative Overview of Its Mode of Action, Pharmacological Properties, and Health Benefits” doi: 10.1155/2021/3268136. PMID: 34336089. | ||

| Name | IOPANOIC ACID |

| IUPAC | 2-[(3-amino-2,4,6-triiodophenyl)methyl]butanoic acid | |

| Formula | C11H12I3NO2 | |

| CAS number | 96-83-3 | |

| Specificity | Type I Deiodinase (D1) and Type II Deiodinase (D2) | |

| Renko, K., et al. [31], Endocrinology. 2012 “Identification of iopanoic acid as substrate of type 1 deiodinase by a novel nonradioactive iodide-release assay”. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1863. PMID: 22434082. | ||

| Name | ITYR-DBRMD |

| IUPAC | –– | |

| Formula | C13H7Br2I2NO5 | |

| CAS number | 1809339-61-4 | |

| Specificity | Type III Deiodinase (D3) | |

| Moskovich D. et al. [93], Oncogene. 2023 “Targeting the DIO3 enzyme using first-in-class inhibitors effectively suppresses tumor growth: a new paradigm in ovarian cancer treatment” doi: 10.1038/s41388-023-02629-2. PMID: 34556811. | ||

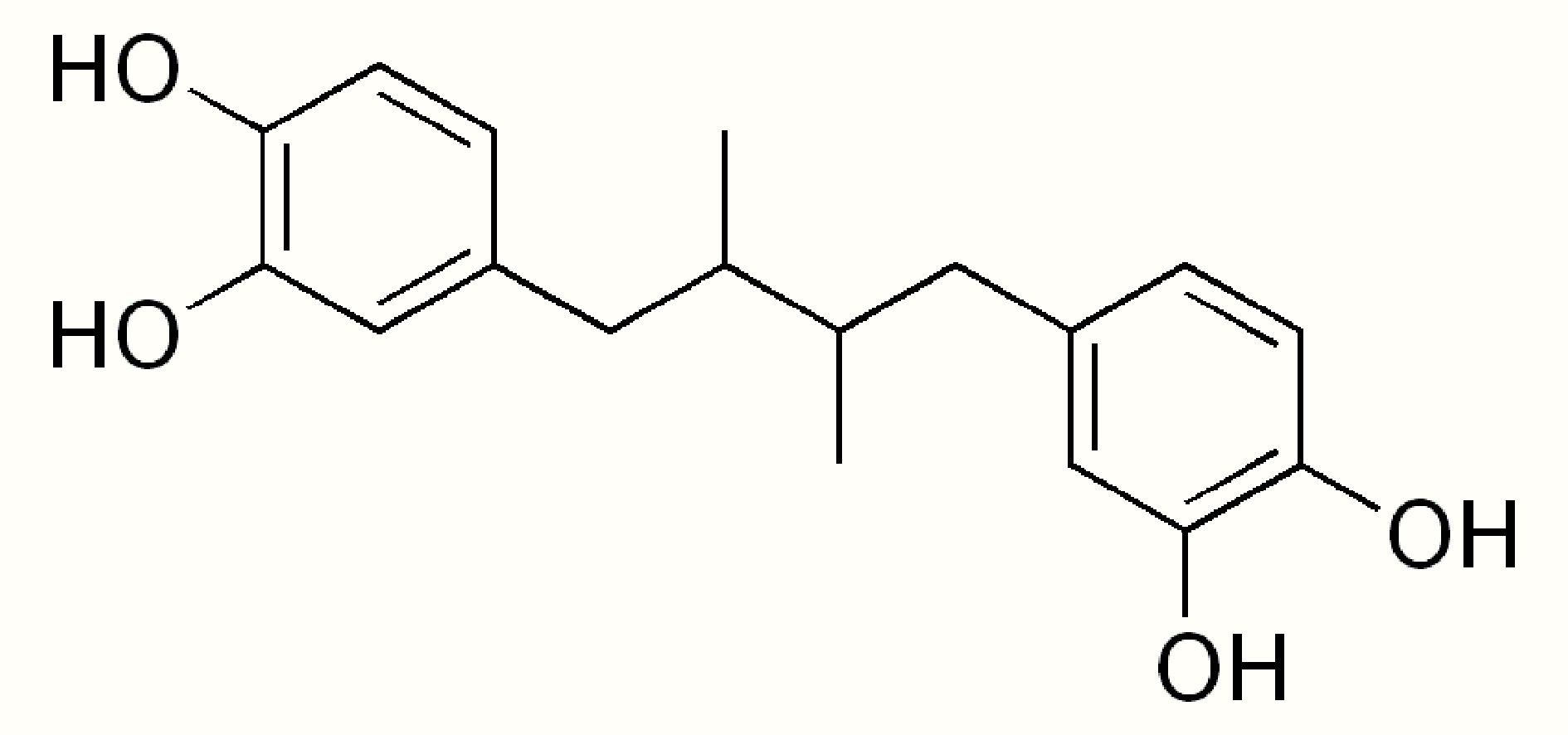

| Name | NORDIHYDROGUAIARETIC ACID |

| IUPAC | 4-[4-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-2,3-dimethylbutyl]benzene-1,2-diol | |

| Formula | C18H22O4 | |

| CAS number | 500-38-9 | |

| Specificity | Type III Deiodinase (D3) | |

| Yu W. et al. [55], Endocr Pract. 2020 “Side effects of PTU and MMI in the treatment of hyperthyroidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis” doi: 10.4158/EP-2019-0221. PMID: 31652102. | ||

| Name | PBENZ-DBRMD |

| IUPAC | 4-(3,4-dibromo-2,5-dioxopyrrol-1-yl)benzoic acid | |

| Formula | C11H5Br2NO4 | |

| CAS number | 1454662-41-9 | |

| Specificity | Type III Deiodinase (D3) | |

| Wiersinga, W.M. [56], Thyroid, 1991. “Propranolol and thyroid hormone metabolism”. doi: 10.1089/thy.1991.1.273. PMID: 1688102 | ||

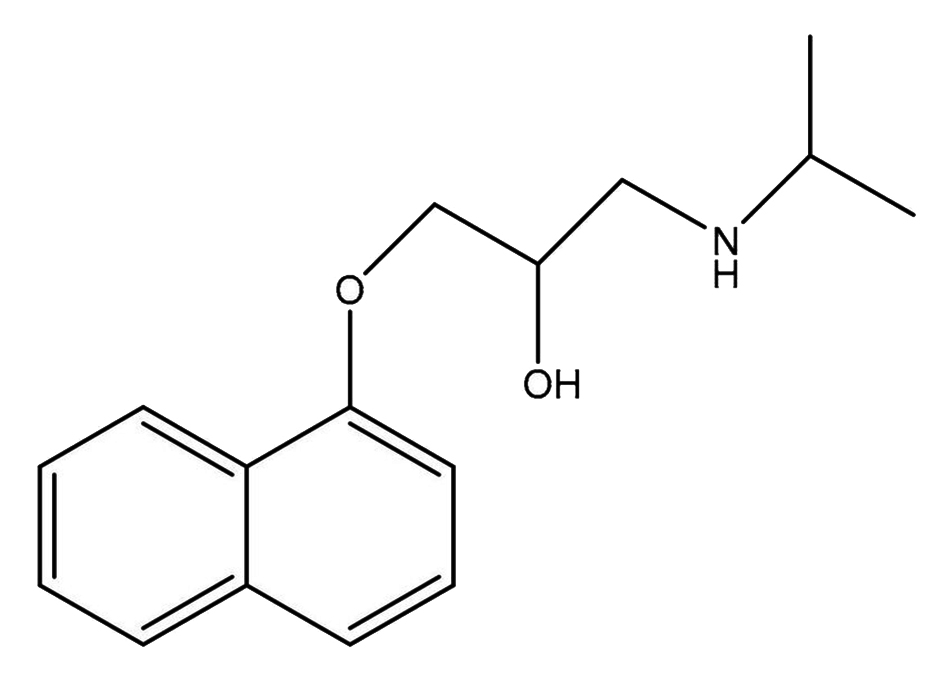

| Name | PROPRANOLOL |

| IUPAC | 1-naphthalen-1-yloxy-3-(propan-2-ylamino)propan-2-ol | |

| Formula | C16H21NO2 | |

| CAS number | 525-66-6 | |

| Specificity | Type I Deiodinase (D1) | |

| Renko K. et al. [94], Thyroid. 2015 “An Improved Nonradioactive Screening Method Identifies Genistein and Xanthohumol as Potent Inhibitors of Iodothyronine Deiodinases” doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0058. PMID: 25962824. | ||

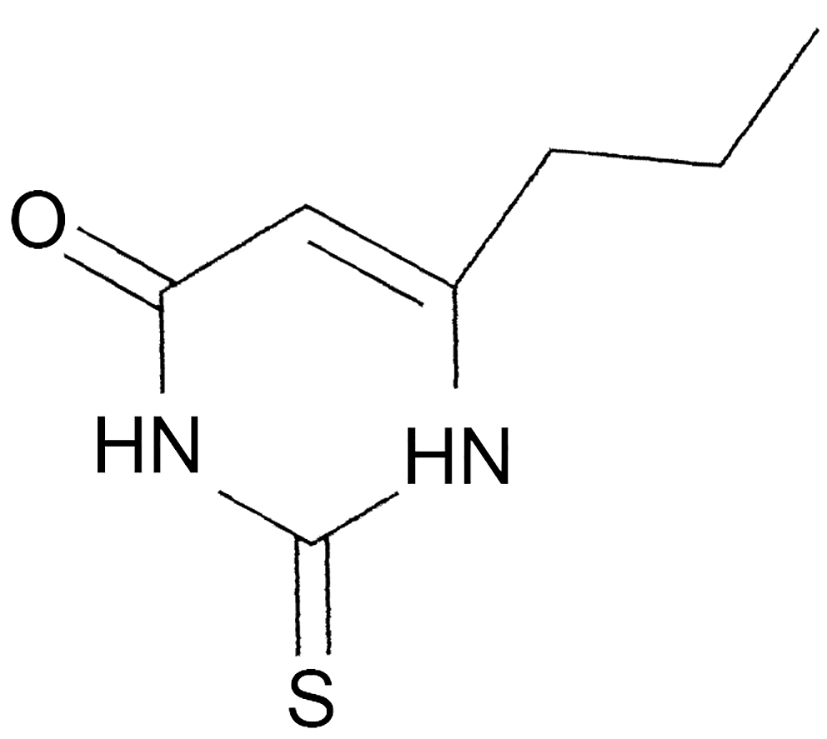

| Name | PROPYLTHIOURACIL |

| IUPAC | 2,3-dihydro-6-propyl-2-tioxopirimidin-4 (1H)-one | |

| Formula | C7H10N2OS | |

| CAS number | 51-52-5 | |

| Specificity | Type I Deiodinase (D1) | |

| Olker JH. et al. [95], Toxicol Sci. 2019 “Screening the ToxCast Phase 1, Phase 2, and e1k Chemical Libraries for Inhibitors of Iodothyronine Deiodinases” doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfy302. PMID: 30561685. | ||

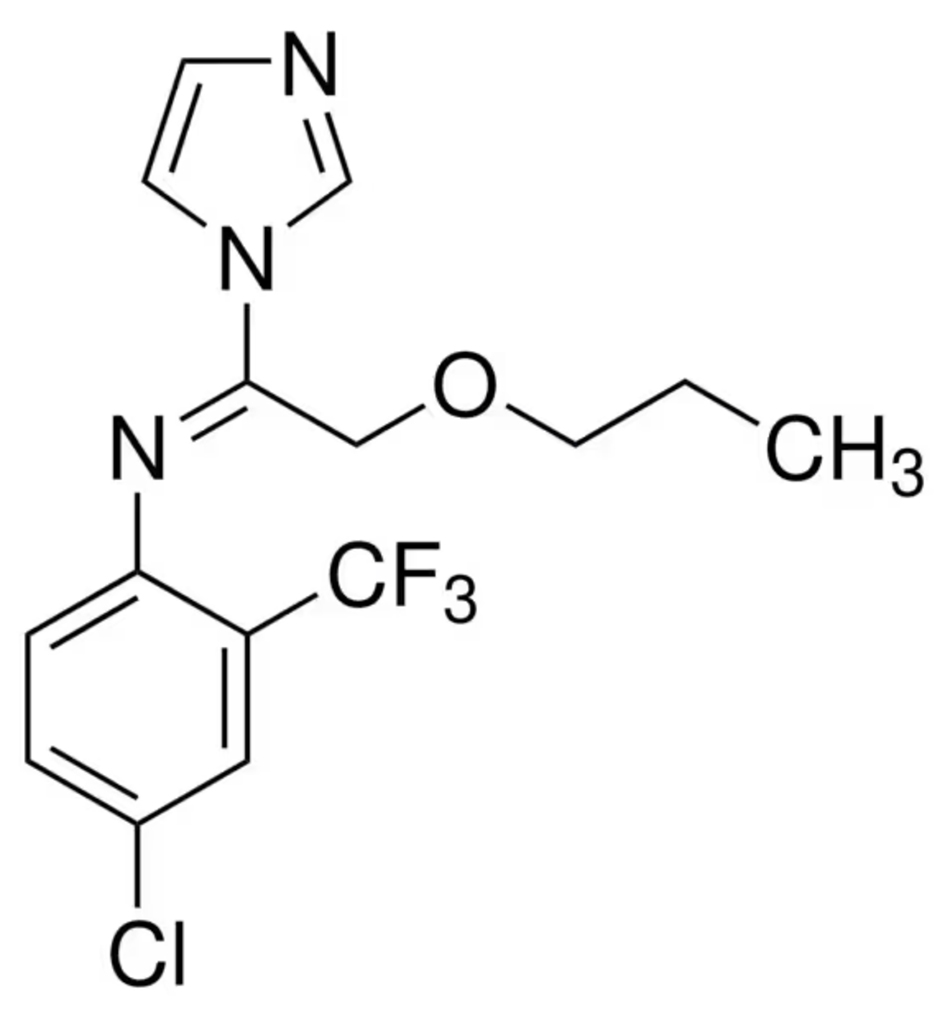

| Name | TRIFLUMIZOLE |

| IUPAC | (E)-4-chloro- | |

| Formula | C15H15ClF3N3O | |

| CAS number | 68694-11-1 | |

| Specificity | Type II Deiodinase (D2) | |

| Olker JH. et al. [95], Toxicol Sci. 2019 “Screening the ToxCast Phase 1, Phase 2, and e1k Chemical Libraries for Inhibitors of Iodothyronine Deiodinases” doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfy302. PMID: 30561685. | ||

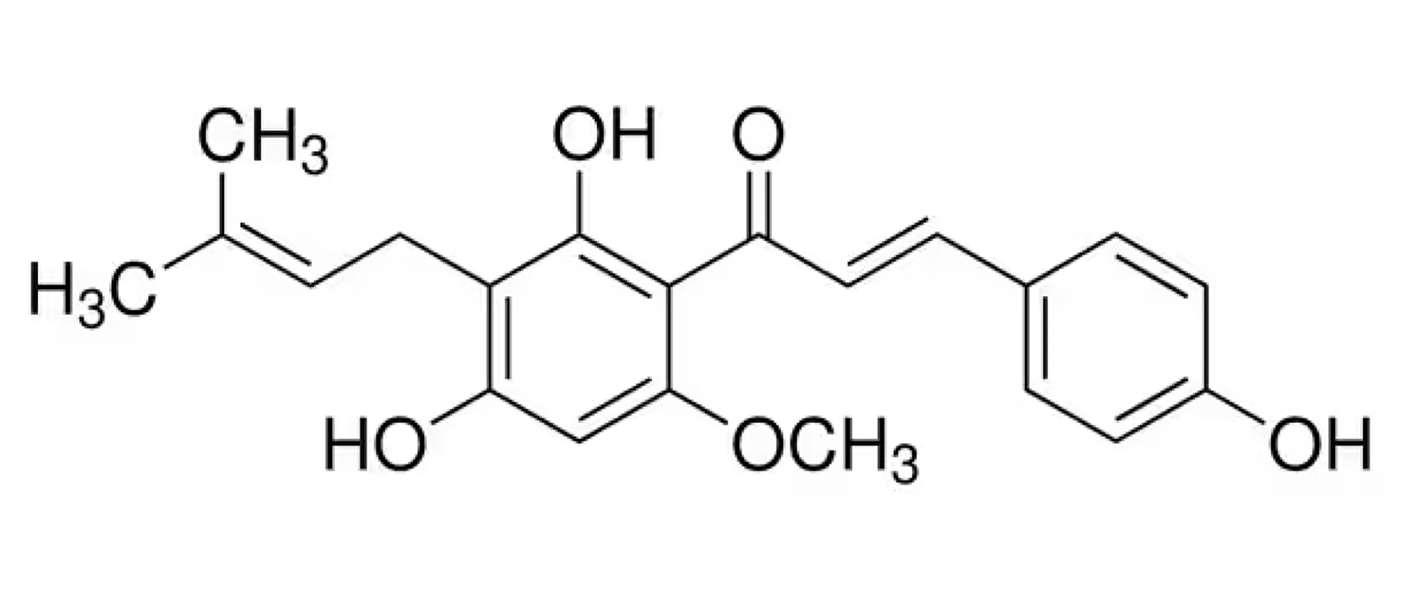

| Name | XANTHOHUMOL |

| IUPAC | 1-(2,4-Dihydroxy-6-methoxy-3-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)phenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one | |

| Formula | C21H22O5 | |

| CAS number | 6754-58-1 | |

| Specificity | Type I Deiodinase (D1), Type II Deiodinase (D2) and Type III Deiodinase (D3) | |

| Renko K. et al. [94], Thyroid. 2015 “An Improved Nonradioactive Screening Method Identifies Genistein and Xanthohumol as Potent Inhibitors of Iodothyronine Deiodinases” doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0058. PMID: 25962824. | ||

THs, Thyroid Hormones; T4, Thyroxine; T3, Triiodothyronine; rT3, reverse T3; IOP, Iopanoic Acid; PTU, Propylthiouracil; MMI, Methimazole; TPO, Thyroid Peroxidase; TSH, Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone; HPT, Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid; LC-MS/MS, Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry; DBRMD, dibromomaleic anhydride; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; IUPAC, International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry; CAS number, Chemical Abstracts Service number.

MD and AN conceived and executed the idea for this manuscript and finalized it. LA, CM and AGC substantially contributed to drafting different sections of the manuscript, literature search, coordinated with others. AN designed figures and organized the table. LA, CM, AGC, MD and AN critically reviewed the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research was supported by grants awarded to Monica Dentice (M.D.) from AIRC Foundation for Cancer Research in Italy awarded to Monica Dentice (M.D.) (IG 29242) and Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca – MIUR (PRIN-2022 Grant, Project Code 2022HB54P9), and a grant awarded to Caterina Miro (C.M.) from AIRC Foundation for Cancer Research in Italy (MFAG 30433). The authors gratefully acknowledge AIRC Foundation for Cancer Research in Italy for supporting Annarita Nappi (A.N.) by an AIRC Fellowship for Italy Post Doc grant – (project code 31215).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.