1 The Intensive Care Unit, The First Dongguan Affiliated Hospital, Guangdong Medical University, 523710 Dongguan, Guangdong, China

2 The Intensive Care Unit, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University, 524003 Zhanjiang, Guangdong, China

3 Jieyang Medical Research Center, Jieyang People’s Hospital, 522099 Jieyang, Guangdong, China

4 The Intensive Care Unit, Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University, 524013 Zhanjiang, Guangdong, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Excessive inflammatory responses in sepsis result in multiorgan dysfunction, with the majority of these responses being modulated by the activity of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 10 (ADAM10). Due to the widespread distribution of ADAM10 and its numerous substrates, therapies targeting ADAM10 will have a range of physiological effects, including modulating inflammation, but may also cause toxic side effects. Precise therapeutic targets for regulating ADAM10 in specific diseases are needed. In several studies, tetraspanin family members have been identified as regulators of specific proteins, including ADAM10. In various cell types, the identical tetraspanin exhibits distinct effects on the regulation of ADAM10, indicating that tetraspanins possess cell-specific roles in modulating ADAM10. Furthermore, the interaction of diverse tetraspanins with ADAM10 results in the cleavage of various substrates. In this review, we provide a summary of the diverse tetraspanins that are currently recognized to interact with ADAM10 to identify potential new targets for regulating ADAM10 in sepsis.

Keywords

- sepsis

- ADAM10 protein

- tetraspanins

- inflammation

Sepsis, defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection, has high morbidity and mortality rates [1, 2]. Global epidemiological data from 2017 indicate that sepsis resulted in an estimated 48.9 million incident cases and 11.0 million attributable deaths, constituting 19.7% of worldwide mortality during this period [3]. Sepsis is also associated with frequent hospital readmissions following discharge. Within the US healthcare system, sepsis and other infectious complications are leading causes of 30-day hospital readmissions, with mean expenditures reaching $16,852 per readmission episode. In China, epidemiological studies show that sepsis affects approximately 20% of ICU-admitted patients, correlating with 90-day mortality rates as high as 35.5% [4, 5]. Thus, sepsis imposes a significant burden on both the medical system and society.

Extensive efforts have been made by health care professionals and researchers to elucidate the pathophysiology of sepsis and to develop effective therapeutic strategies to mitigate its progression. Sepsis pathogenesis involves multifactorial dysregulation encompassing infection-triggered inflammatory cascades, immune dysfunction, coagulopathy, and tissue damage. Central to this process is a dysregulated hyperinflammatory response characterized by excessive proinflammatory mediator release and profound autoimmune injury, culminating in multiorgan dysfunction syndrome [6]. During the inflammatory response, increased cleavage and release of the extracellular domains of inflammatory cytokines on the surface of various cells, such as macrophages and endothelial cells, leads to elevated liberation of soluble mediators including tumor necrosis factor-

ADAM10 is a type I transmembrane protein with a complex protein structure consisting of different parts. These parts include (1) an N-terminal signal peptide responsible for regulating the secretion of inactive ADAM10; (2) a prodomain that inhibits the enzyme activity of ADAM10; (3) a metalloproteinase domain that serves as the primary site of sheddase activity; (4) a disintegrin domain and cysteine-rich region that are associated with substrate specificity; and (5) transmembrane domains and cytoplasmic tails that facilitate the formation of homologous dimers of ADAM10 on the cell membrane [10, 11, 12]. ADAM10 can be widely found in the cells of various organs, it can regulate signaling in the affected cell or neighboring cells either directly through the modulation of cell surface receptors or indirectly through the release of soluble mediators from membrane-bound precursors, as extracellular domain shedding of transmembrane proteins mediated by ADAM10 occurs [13]. Building upon our prior research, we have established that ADAM10, functioning as a pivotal “multitasker” protease due to its diverse array of substrates, critically modulates vascular inflammatory homeostasis while simultaneously driving pathogenic mechanisms in acute inflammation. This dualistic involvement—safeguarding vascular integrity under physiological conditions yet contributing to dysregulated inflammation during acute insults—underscores ADAM10’s central role in the complex pathophysiology of sepsis. Consequently, the strategic modulation of ADAM10 activity and its post-translational processing of key membrane-bound targets represents a compelling therapeutic avenue for sepsis intervention [9]. However, given the wide distribution of ADAM10 and the diversity of its substrates, dysregulation of the expression or activity of this enzyme can lead to various pathological consequences. For instance, elevated ADAM10 levels, frequently observed in certain malignancies and inflammatory conditions, can drive pathological processes, including tumor cell proliferation and the amplification of inflammatory cascades. Conversely, diminished ADAM10 function, particularly within the central nervous system, compromises the generation of neuroprotective soluble amyloid precursor protein

Several studies have found that specific members of the tetraspanin family regulate the activities of various ADAM proteins, particularly ADAM10. These studies also revealed that a large proportion of ADAM10 molecules on the cell membrane interact with tetraspanins [15, 16]. Tetraspanins are a family of ubiquitously expressed and evolutionarily conserved proteins in multicellular organisms, and there are 33 identified members [17, 18] with different distributions in different cells and tissues [19, 20, 21]. On the basis of their amino acid sequences, these members can be classified into different subfamilies, such as the TspanC8 subfamily and the Tspan8 subfamily [22, 23, 24, 25]. By interacting with other tetraspanins and a variety of interacting partners, facilitated by gangliosides, palmitoylation, and cholesterol, tetraspanins form wide-ranging complexes of fewer than 10 transmembrane proteins ranging in size from 100 to 200 nm known as the tetraspanin web [17, 26, 27]. These tetraspanin webs facilitate the lateral assembly of integrins, immunoreceptors, and signaling effectors into functional clusters, thereby modulating critical vascular processes, including leukocyte adhesion, paracellular permeability, and angiogenic signaling cascades. The spatial organization within the tetraspanin web enables bidirectional regulation of signal transduction—enhancing agonist sensitivity through co-receptor recruitment while simultaneously constraining excessive activation via intramembrane compartmentalization. This sophisticated architecture underpins endothelial barrier homeostasis and inflammatory responses, positioning tetraspanins as pivotal coordinators of vascular pathophysiology [19]. Cellular exosomes containing tetraspanins such as CD63 and CD81 can deliver their contents (e.g., microRNAs (miRNAs)) to specific target cells and participate in intercellular communication [28]. This enables them to assume diverse roles in response to various pathogenic infections, such as bacteria and viruses [21, 28].

Critically, members of the TspanC8 tetraspanin subfamily exhibit cell type-dependent specificity in modulating ADAM10 function, profoundly influencing its substrate selectivity, subcellular localization, and catalytic efficiency. This regulatory heterogeneity is exemplified by Tspan15, which acts as a key molecular chaperone, directing ADAM10 trafficking and stabilizing its active conformation within distinct plasma membrane microdomains. Consequently, Tspan15 expression dictates divergent outcomes in ADAM10-dependent ectodomain shedding: in neuronal contexts, it enhances

ADAM10, a member of the ADAM family, is a zinc-dependent metalloprotease found in most tissue cells and immune cells. It can impact cell signaling by cleaving the extracellular domains of proteins, affecting cell functions such as adhesion, growth, and migration [14].

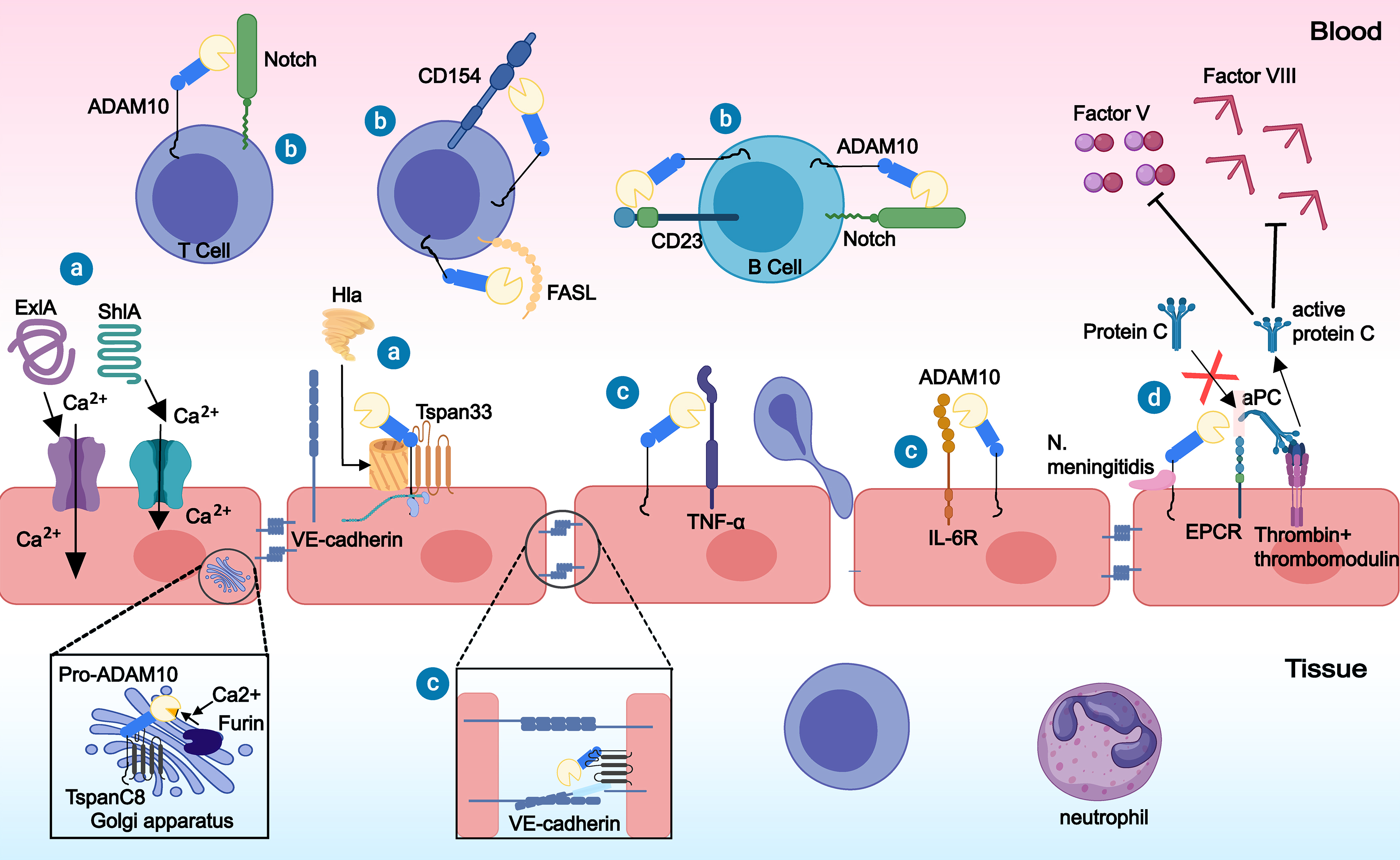

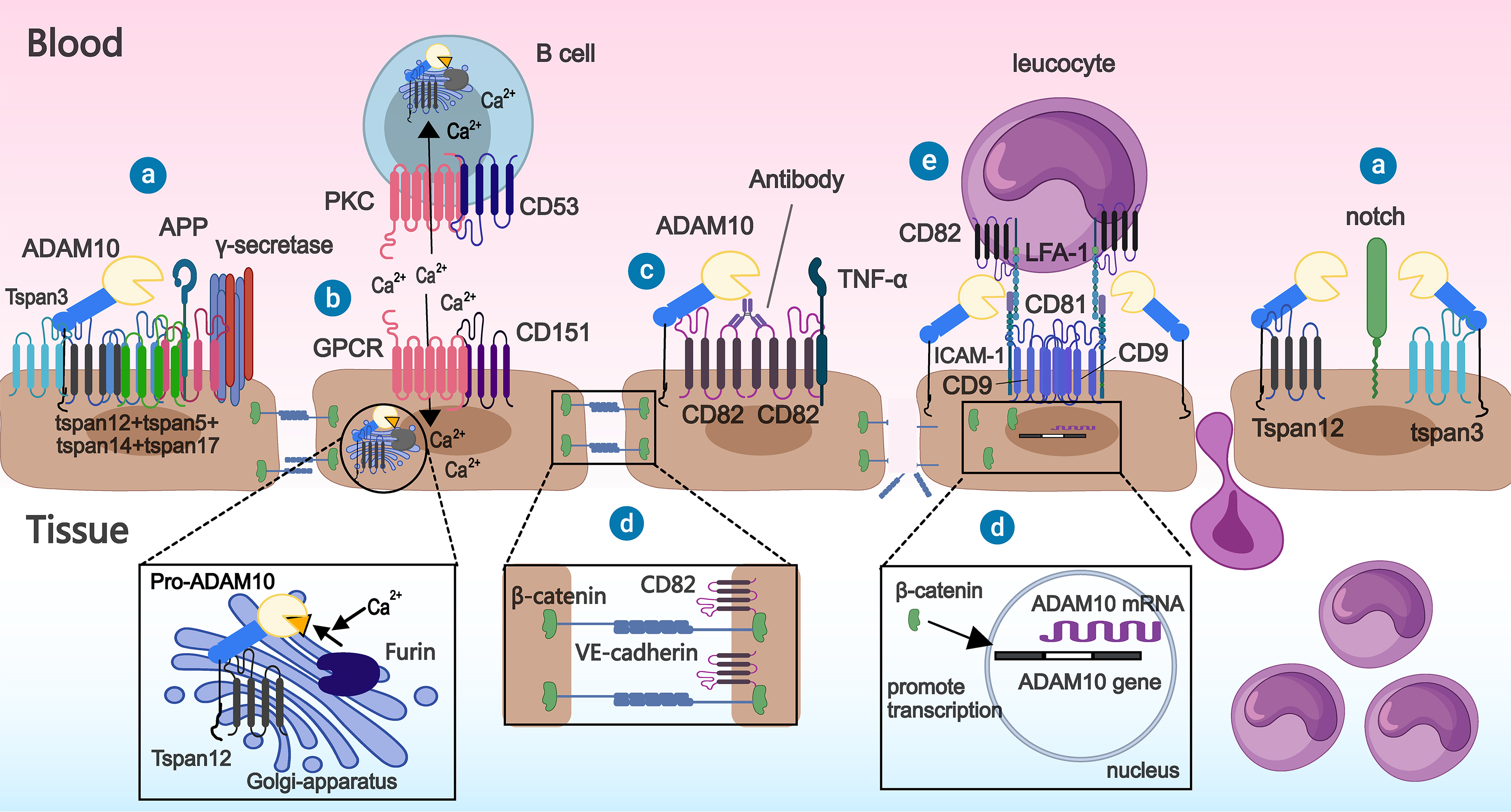

Several studies have shown that ADAM10 plays a key role in sepsis (Fig. 1). Our team identified ADAM10 as a risk gene for sepsis and showed that upregulation of the ADAM10 gene promotes the inflammatory response and endothelial damage in sepsis, ultimately leading to the deterioration of sepsis patients and poor prognosis [31, 32]. By cleaving the Notch receptors Fas ligand (FASL), CD154, and CD23, ADAM10 can regulate the growth and development as well as the activation and differentiation of T and B cells [33]. ADAM10 also promotes the cleavage of Notch receptors on the surface of macrophages and induces macrophage polarization to the macrophage phenotype M1 (M1 phenotype), which in turn results in the release of large amounts of inflammatory factors [33]. Furthermore, ADAM10 promotes the regulation of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The role of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 10 (ADAM10) in sepsis. ⓐ Bacterial toxins such as Serratia marcescens hemolysin (ShlA), Pseudomonas aeruginosa PFT exolysin (ExlA), and

Pathogenic infection is the initiating factor of sepsis. Through the action of ADAM10, various bacterial toxins can exacerbate endothelial damage during sepsis [39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44]. ADAM10, a binding receptor for

The human ADAM10 gene comprises 16 exons. Many transcription factors, such as retinoic acid, sirtuin, melatonin, SRY-Box transcription Factor 2 (SOX-2), and early growth response 1 (EGR1), regulate the transcription of the ADAM10 gene. After being transcribed to mature mRNA, posttranslational modifications can alter the RNA structure of ADAM10 and RNA binding proteins, thus impacting ADAM10 protein expression [31, 45]. By binding to the 3′UTR of the ADAM10 gene, miRNAs affect ADAM10 expression at the posttranscriptional level [45, 46]. In addition to regulating chromatin structure and transcript splicing, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) can also serve as decoys for other transcripts or regulate protein recruitment [46]. Translated in the cytoplasm by the ribosomal machinery, the full-length form of ADAM10, consisting of 748 amino acids, is not catalytically active. The 195-amino acid prestructural domain of ADAM10 maintains the protein in a dormant state, which permits its proper folding and transport. Upon reaching the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the C-terminal retention motif of ADAM10 hinders the export of the protein from the ER. Tetraspanins are required to transport ADAM10 out of the ER, as shown by Dornier et al. (2012) [22]. Tetraspanins transport ADAM10 to the Golgi, where preprotein convertases remove the prestructural domain to activate it. Subsequently, ADAM10 is cooperatively transported by tetraspanins to various cellular compartments or ultimately anchored to the cell membrane to execute its physiological function [14, 47]. Therefore, tetraspanins are indispensable for the function of ADAM10.

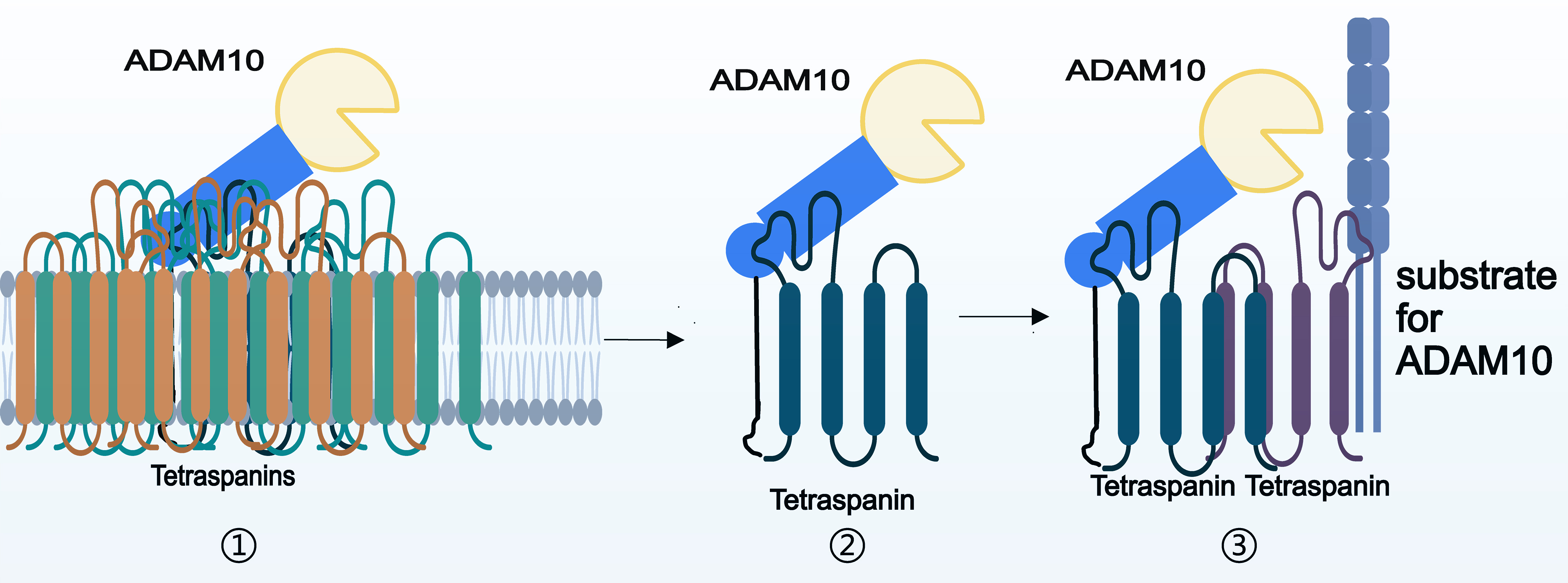

Tetraspanin family members typically consist of four transmembrane domains, two extracellular domains (comprising a larger loop and a smaller loop), and three intracellular domains (including a short loop and N-terminal and C-terminal regions) [24]. The interaction of these proteins with their interaction partners appears to be facilitated primarily by their large extracellular loops [48, 49], which demonstrate remarkable stability even in the presence of strong detergents [50]. Homotypic or heterotypic tetraspanin proteins may also utilize weaker interactions that are susceptible to disruption by common detergents to form sheets. Additionally, the palmitoylation of tetraspanins, along with the presence of cholesterol, gangliosides, and other factors, enhances cohesion within tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Basis of the interaction between ADAM10 and tetraspanins. ① Multiple tetraspanins incorporate ADAM10 into tetraspanin-enriched domains by interacting with each other. ② Tetraspanins interact directly with ADAM10 by binding to it through a large extracellular loop. ③ Tetraspanins indirectly interacts with ADAM10 by interacting with other tetraspanins.

Considering the intricate interactions within the tetraspanin web, it is hypothesized that the molecule exerting the most significant regulatory influence on ADAM10 activity is likely the one with which it is most directly associated. Therefore, elucidating the spatial proximity of interactions between tetraspanins and ADAM10 could facilitate the identification of molecules capable of precisely regulating ADAM10 in the context of sepsis. The association of various tetraspanins to ADAM10 has been validated through immunoprecipitation, and these tetraspanins can be categorized into two groups on the basis of the impact of detergents of varying strengths on them [22]: tetraspanins that can directly interact with ADAM10 in the presence of potent detergents and tetraspanins that can only indirectly interact with ADAM10 in the presence of weaker detergents. It appears that only the interactions between ADAM10 and the six members of the subfamily TspanC8 (tspan5, pspan10, pspan14, tpan15, pspan17, and tpan33), which are the best known cellular regulators of ADAM10, are resistant to stronger detergents, while the interactions between the remaining tetraspanins and ADAM10 are generally weak and susceptible to standard detergents [22, 50].

Immunoprecipitation is a classic and well-established method for studying protein interactions. However, variations in the composition and concentration of the detergents utilized by researchers for immunoprecipitation (Table 1, Ref. [22, 28, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75]) present challenges in accurately determining the nature of interactions through this method; for instance, Brij97 and 3-[(3-Chloamidopropyl)dimethyl-ammonium]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), which have weak effects, and concentrations of detergents lower than the standard ones are sometimes used for immunoprecipitation. Additionally, the majority of researchers have not employed experimental techniques other than coprecipitation to elucidate the mechanism of interaction among interacting proteins. Arduise et al. (2008) [16] used fluorescence staining to observe the colocalization of tetraspanins with ADAM10 and its substrates on the cell membrane after antibody stimulation. However, it is well known that fluorescence colocalization analysis is predicated on the spatial distribution of fluorescence tags attached to distinct proteins. It is widely acknowledged that the colocalization of distinct fluorescent signals is indicative of spatial proximity between the corresponding proteins and suggests the potential for interaction but does not provide conclusive evidence of such interactions. Thus, it has not yet been determined whether the association between tetraspanins and ADAM10 is indirect or direct, necessitating additional research to confirm this relationship. In a recent study, Lipper et al. (2022) [76] reported a new method for validating a protein-protein interaction between ADAM10 and Tspan15 and determining the structural basis for this direct interaction by using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM).

| Tetraspanin | Aliases | Effects on ADAM10 | Interaction with ADAM10ⓐ | Detergent(s) used for Co-IP | Reference |

| Tspan5 | TM4SF9, NET-4 | ADAM10 trafficking, maturation, substrate selectivity, endocytosis & half-life | Direct | 1% digitonin | [22, 52, 53] |

| Tspan-10 | OCSP | ADAM10 trafficking & subcellular distribution | Direct | 1% digitonin | [22, 59] |

| Tspan-14 | TM4SF14, DC-TM4F2 | ADAM10 trafficking, maturation & substrate selectivity | Direct | 1% digitonin/1% Triton X-100 | [22, 51, 59] |

| Tspan-15 | NET-7, TM4SF15 | ADAM10 trafficking, maturation, substrate selectivity & half-life | Direct | 1% digitonin/1% Triton X-100 | [22, 52, 55, 57, 59] |

| Tspan-17 | FBX23, FBXO23, TM4SF17 | ADAM10 trafficking, Maturation & substrate selectivity | Direct | 1% digitonin | [22, 53] |

| Tspan-33 | PEN | ADAM10 trafficking, maturation & substrate selectivity | Direct | 1% digitonin/1% Triton X-100 | [22, 54, 56, 57, 58, 59] |

| CD81 | TAPA1, Tspan28 | ADAM10 activity | Indirect | 1% digitonin | [22] |

| CD151 | GP27, SFA-1, PETA-3 | ADAM10 maturation & activity (maybe) | Indirect | 1% digitonin/1% Brij97 & 1% Triton X-100 | [22, 59, 69] |

| Tspan-12 | EVR5, NET2, TM4SF12 | ADAM10 maturation & substrate selectivity | Indirect | 0.5% Brij97/1% digitonin | [22, 61, 73, 74] |

| CD9 | P24, 5H9 Antigen, MIC3, TSPAN29, GIG2 | ADAM10 trafficking & activity | To be determined | 1% digitonin/0.1% Triton X-100/0.2% NP-40 | [22, 63, 64] |

| CD82 | KAI1, Tspan27 | ADAM10 activity; ADAM10 gene transcription (maybe) | To be determined | 1% Brij97 | [28, 67, 68] |

| CD53 | Tspan25, MOX44 | ADAM10 activity (maybe) | To be determined | 1% Brij97 | [28, 70, 71, 72] |

| Tspan3 | TM4-A, TM4SF8 | ADAM10 substrate selectivity & activity | To be determined | 0.5% NP-40 | [60, 75] |

| Tspan2 | NET3, TSN2 | ADAM10 gene transcription (maybe) | To be determined | 0.5% CHAPS | [62, 65, 66, 67] |

ⓐWe conducted a review of the cell lysis detergents utilized in the literature, and found that 1% digitonin and 1% Triton X-100 were the strongest concentrations and detergents used. Consequently, these detergents and concentrations were utilized as standards for assessing the direct interactions between tetraspanins and ADAM10.

For tetraspanins, where direct binding has been confirmed through immunoprecipitation experiments utilizing strong detergents, it has been determined that they possess ADAM10-specific binding sites located on their large extracellular loops [51, 76]. The domains through which these proteins interact with ADAM10 vary significantly and include disintegrin, cysteine-rich, and stalk domains [51]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that tetraspanins are involved in the cleavage of the extracellular structural domains of various substrates by ADAM10 [29, 47, 51, 77, 78]. Lipper et al. (2023) [79] recently elucidated the molecular mechanism underlying the interaction between ADAM10 and its classical interaction partner Tspan15. The interaction between Tspan15 and ADAM10 disrupts the autoinhibition of the enzyme activity of ADAM10, leading to the localization of the enzyme’s active center near the plasma membrane. Being fixed near the plasma membrane influences the preferential cleavage site of ADAM10 for its substrate [79]. This discovery confirms a previously hypothesized explanation for the substrate specificity of ADAM10 bound to various tetraspanins, suggesting that distinct tetratransmembrane proteins bind to ADAM10 and position their active sites at varying distances from the plasma membrane to facilitate the cleavage of diverse substrates.

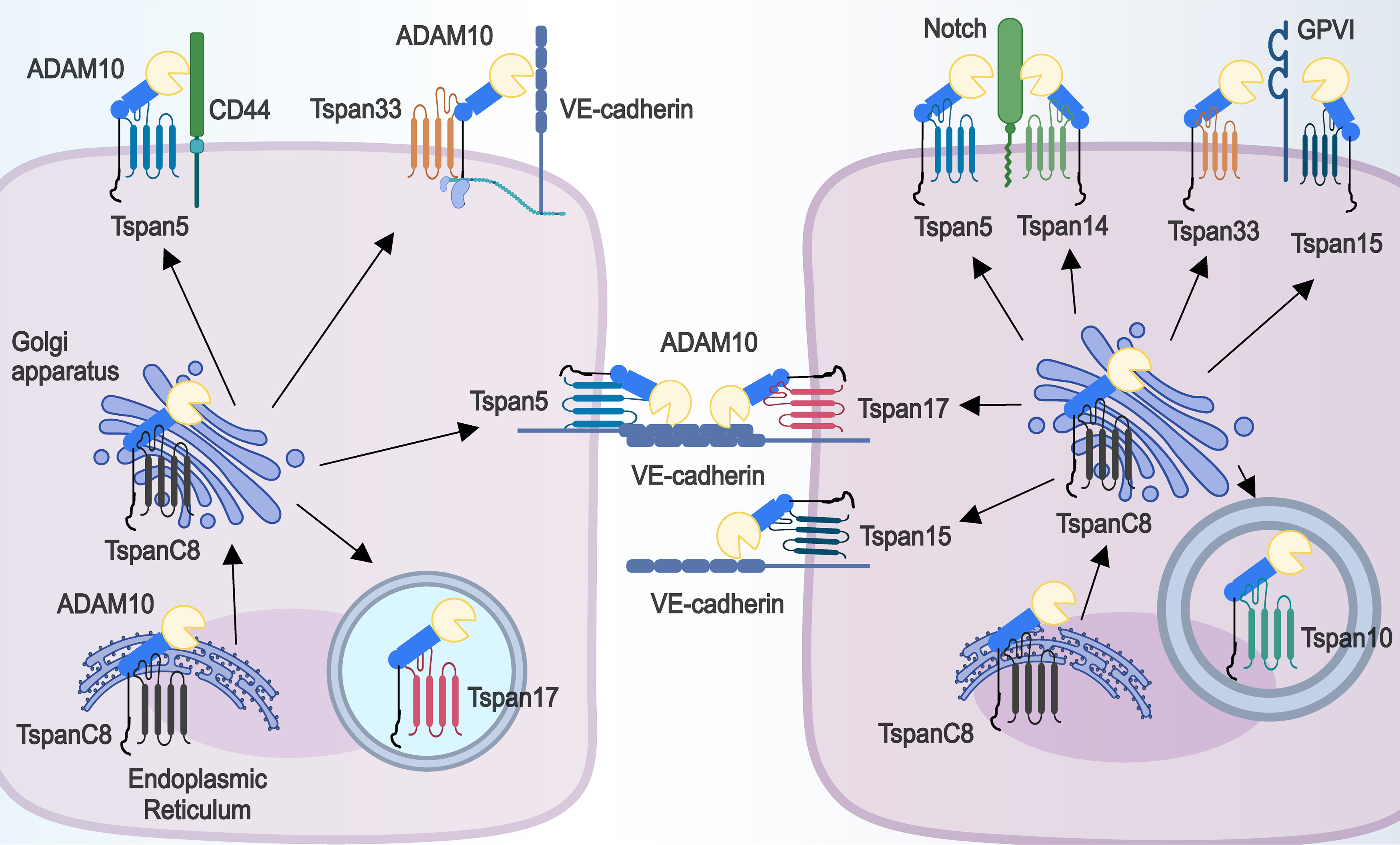

The six tetraspanins tspan5, tspan10, tspan14, tspan15, tspan17, and tspan33, are collectively referred to as the tspanC8 subfamily because of the eight cysteines in their large extracellular structural domains. All members of the TspanC8 subfamily are known to interact with ADAM10 directly, facilitating its trafficking from the ER and increasing its cellular localization and expression levels, either intracellularly or at the plasma membrane [22, 52]. Consequently, the interactions between these tetraspanins and ADAM10 may have implications for disease pathology [80, 81, 82] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. TspanC8 subfamily members can directly affect the subcellular localization and substrate selectivity of ADAM10. Each TspanC8 member binds directly to ADAM10, assists in the transport of ADAM10 out of the ER, and facilitates the distribution of ADAM10 either intracellularly (Tspan10 and Tspan17) or at the cell membrane (Tspan5, Tspan14, Tspan17, Tspan15, and Tspan33). At the plasma membrane, Tspan5, Tspan14, Tspan15 and Tspan33 bind to the tetraspanin web in different ways and affect ADAM10 cleavage of various substrates (e.g., CD44, VE-cadherin, Notch, Glycoprotein VI (GPVI)).

Tspan5, a highly conserved tetraspanin, has an identical protein sequence in humans, mice, and rats. Tspan5 is linked with ADAM10 in human cell lines and major mouse tissues like the brain, lung, kidney, and intestine. Saint-Pol et al. (2017) [83] have found that two TspanC8-specific motifs in tspan5’s large extracellular domain are crucial for interacting with ADAM10 and exiting the endoplasmic reticulum. Tspan5 facilitates the clustering of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules on the cell surface, thereby promoting CD8+ T-cell activation [84]. This may help alleviate immunosuppression in patients with sepsis, as Lu et al. (2024) [85] have found that the activation of immune cells, including CD8+ T-cells, is suppressed in patients with early-stage sepsis. Tspan5 also reduces VE-cadherin expression on vascular endothelial cell membranes, thereby promoting the transendothelial migration of T lymphocytes during inflammation [53].

Tspan5 facilitates ADAM10-mediated cleavage of the extracellular domain of CD44 on cell membranes, potentially leading to cell migration and disruption of intercellular adhesion junctions [29, 38, 86]. Researchers have identified 35 signature genes that predict mortality from sepsis, including CD44 [87]. In endothelial cells, stimulation with dengue virus nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) decreases CD44 expression, which leads to impaired vessel integrity [88]. These findings indicate that tspan5 may influence sepsis by regulating CD44.

Sepsis is highly influenced by Notch signaling. Inactivation or deletion of Notch1 leads to impaired T-cell development and reduced lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated B-cell antibody secretion [89]. Through the Notch pathway, Notch ligands activate cellular immune responses, leading to the release of proinflammatory cytokines [90]. The stimulation of LPS triggers the activation of the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and Notch signaling pathways in cardiac tissues, which in turn amplifies the inflammatory response in the hearts of septic rats, ultimately causes cardiac dysfunction and myocardial damage [91]. In a cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-induced sepsis mouse model, Notch2 is involved in angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) system activation and angiotensin II release and causes vascular endothelial injury via angiotensin II-induced ROS production [92]. Modulation of Notch receptors could represent a new therapeutic strategy for sepsis. Coincidentally, tspan5 activates Notch signaling by enhancing the enzyme-mediated maturation of ADAM10 and the cleavage of the Notch1 receptor by the

The tspan15 protein, which is expressed in various tissue types, is perhaps the tetratransmembrane partner that is functionally most closely related to ADAM10 [93]. ADAM10 is the main interacting protein of tspan15 and can affect its glycosylation. Furthermore, the majority of endogenous tspan15 molecules must complex with ADAM10 to be expressed on the cell membrane [77]. Moreover, Tspan15 is essential for the cleavage of specific substrates by ADAM10 at the cell membrane and contributes to the stable expression of ADAM10 on the cell membrane surface [29, 30, 52, 54, 77].

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) in patients with complex cases of pneumococcal pneumonia (empyema) revealed an association between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the Tspan15 gene and the disease. Decreased levels of tspan15 gene expression were observed in the tissues of Streptococcus. pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae)-infected humans and mice compared to those of healthy controls [55]. Koo CZ et al. (2022) [54] reported that Tspan15 promotes the ADAM10-mediated cleavage of the extracellular domain of GPVI on the platelet membrane to a greater extent than other tspanC8 members to play a role in the inflammatory response. While inhibition of the NF-

The impact of tspan15 on substrate cleavage by ADAM10 varies depending on the cell type: tspan15 expression in U2OS-N1 cells results in a significant decrease in ligand-induced Notch signaling [29], whereas in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) cells, tspan15 activates Notch1 by facilitating the translocation of activated mADAM10 from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane [98]. In HEK-293T cells, VE-cadherin serves as a cleavage substrate for the Tspan15/ADAM10 complex, and the regulatory effect of this complex on VE-cadherin levels on endothelial cells is less pronounced than that of complexes composed of other tspanC8 proteins and ADAM10 [53, 77]. These findings further suggest that tspan15 may play different regulatory roles in ADAM10-associated inflammatory responses in different tissues and organs and even in different cell types in sepsis.

Tspan33 is found in various human tissues, particularly in the kidneys, and activated B cells in the blood. It is considered a key indicator of B-cell activation [99]. It has been reported that tspan33 plays a role in various cellular functions of B lymphocytes, including plasma membrane protrusion formation, adhesion, phagocytosis, and cell motility. Overexpression or partial loss of TSPAN33 induces morphological changes and cell adhesion defects and thus affects the immune function of B cells in sepsis [100, 101].

One of the most common organs affected by sepsis is the kidney, and even a single episode of septic acute kidney injury (AKI) is associated with an increased risk of subsequent chronic kidney disease [102, 103]. A study conducted by Ghasemi et al. (2022) [104] identified Tspan33 as a potential causative gene for chronic kidney disease. The important role of ADAM10, a tspan33 interaction—partner, in renal physiopathology has long been recognized [105]. Perhaps in the near future, there will be evidence suggesting a role for tspan33 and ADAM10 in septic kidney injury.

Tspan33 is one of the only identified tspanC8 subfamily members that can play a role in inflammation by mediating ADAM10 cleavage of the extracellular domain of Glycoprotein VI (GPVI) on the platelet membrane [54]. In contrast to tspan15, which is localized at the lateral junctions of the cell membrane, tspan33 mediates the aggregation of ADAM10 at the apical junctions of the cell membrane through the formation of complexes with proteins such as PLEKHA7 [56]. This coordination promotes cell death during Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) infection by facilitating the formation of stable

In HUVECs and mouse megakaryocytes, tspan14 is the predominantly expressed TspanC8 protein. Knockdown of tspan14 significantly reduces the surface expression and activity of ADAM10 in these cells [59]. In human platelets, tspan14 acts differently from tspan15/tspan33 by inhibiting the cleavage of GPVI by ADAM10 [51]. S. aureus is known to cause various infections and produces the pore-forming toxin alpha-hemolysin (

ADAM10 plays a crucial role in mediating Notch signaling, which in turn influences inflammatory responses [111]. Dornier et al. (2012) [22] were the first to identify the role of human tspan14 in positively regulating ligand-induced ADAM10-dependent Notch1 signaling. Saint-Pol et al. (2017) [83] subsequently demonstrated that tspan14 and tspan5 can functionally compensate for each other in Notch signaling. In addition, some researchers have suggested that there may be a causal relationship between the regulation of the ADAM10 and Notch-1 proteins by tspan14 and the expression of Matrix metalloproteinases 2 (MMP2) and MMP9, as they reported that the silencing of tspan14 was accompanied by elevated expression of MMPs; however, this hypothesis needs to be further validated [112]. In Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection-induced gastritis and in LPS- and IFN-

Compared with other members of the tspan subfamily, such as tspan14, tspan15, and tspan33, tspan17 has only a moderate effect on ADAM10 expression at the cell membrane surface. Additionally, tspan17 appears to be responsible for the localization of ADAM10 in tspan17-positive/CD63-positive intracellular compartments [22]. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that tspan17 is currently the only identified tetraspanin besides tspan5 capable of facilitating the inflammatory factor-stimulated transendothelial migration of T lymphocytes through ADAM10 [53].

The inflammatory response is one of the important pathogenetic mechanisms of sepsis. Despite the high degree of identity between human tspan17 and tspan5 revealed by protein sequence analyses and the demonstrated role of tspan17 in cell migration, VE-cadherin remains the only identified substrate for the Tspan17/ADAM10 complex [53]. ADAM10 is known to play an important role in inflammation [9], and the role of ADAM10 in inflammation may be affected by the inhibition of tspan17, an interaction partner of ADAM10.

Tspan10 is the only member of the TspanC8 subfamily with a limited association with ADAM10 in terms of cell surface expression and protein maturation. Similar to tspan17, tspan10 is capable of transporting ADAM10 to intracellular compartments, suggesting its potential role in facilitating the transport of ADAM10 out of the ER [22, 59]. Despite its typically low expression levels in cells, deletion of tspan10 leads to attenuation of ADAM10 maturation and Notch activation [47, 82].

There is limited research on how members of the TspanC8 subfamily regulate ADAM10 in infectious diseases, and the role of tspan10 in this context has not been studied. Matthews et al. (2018) [116] suggested that the TspanC8/ADAM10 complex may play a significant role in the development and function of leukocytes; however, additional research is necessary to substantiate this claim. Although several cleavage substrates of the TspanC8/ADAM10 complex have been elucidated, further investigation is needed to ascertain the potential involvement of most inflammatory factors, such as TNF-

Research on the regulation of ADAM10 by non-TspanC8 subfamily tetraspanins is limited. Arduise et al. (2008) [16] and Dornier et al. (2012) [22] utilized immunoprecipitation to identify interactions between ADAM10 and several non-TspanC8 subfamily proteins [60, 61, 62]. However, further investigations into the functional relationships between non-TspanC8 subfamily members and ADAM10 in various diseases are lacking. Explorations of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains couldn’t confirm if there are other molecules between these proteins and ADAM10. However, studies have identified a connection between non-TspanC8 members and ADAM10 in certain diseases [26, 60, 63, 64]. The potential involvement of TspanC8 subfamily members and other unidentified proteins in mediating this interaction warrants further investigation in the future.

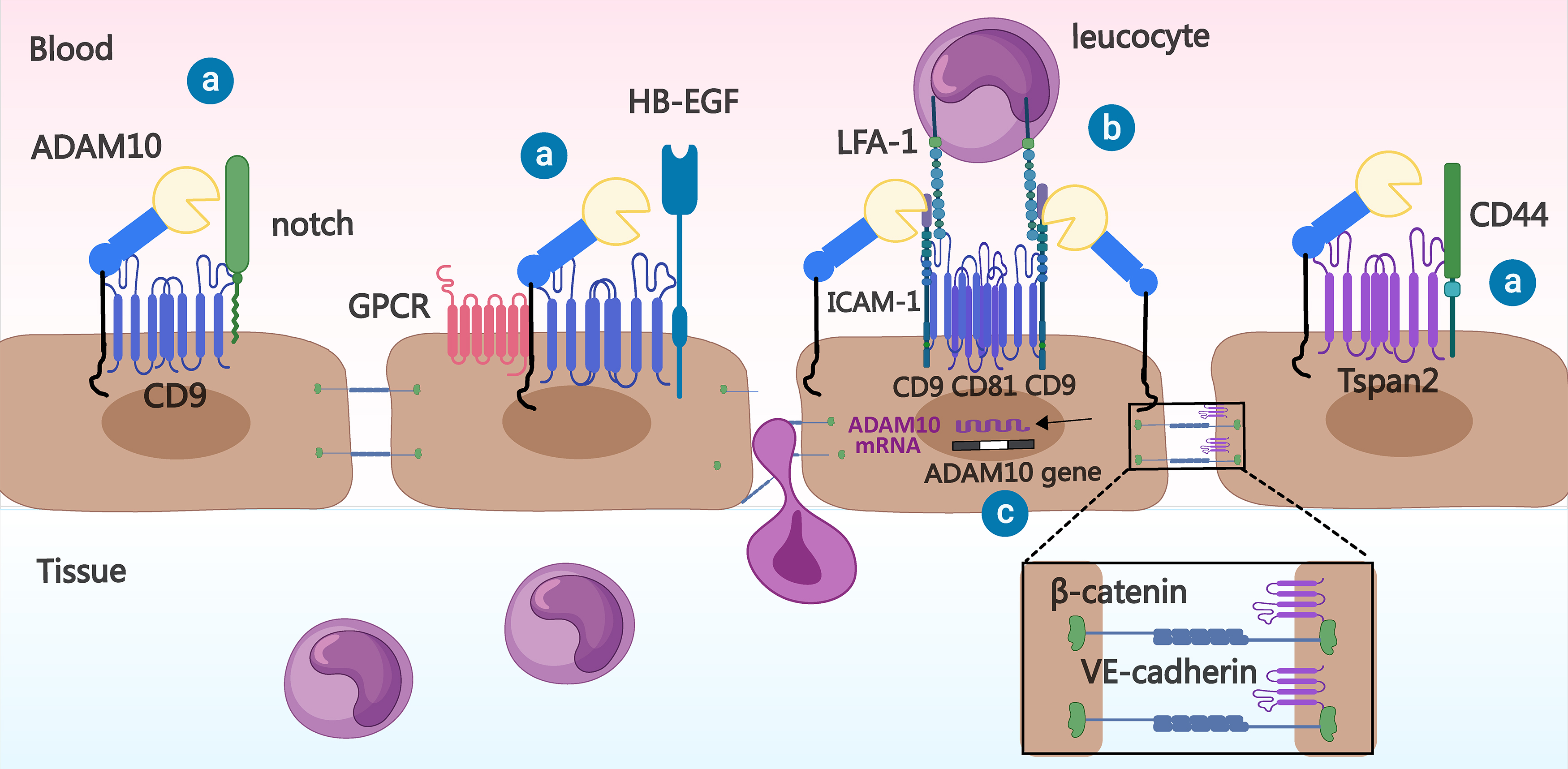

Hemler ME (2001) [23] revealed the sequence homology of four proteins, tspan8, CD9, CD81 and tspan2, which were collectively referred to as the tspan8 subfamily by Müller M et al. (2022) [24]. They found that these proteins can enhance the release of TNF-

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Relationship between Tspan8 subfamily members and ADAM10 in inflammation. ⓐ Tspan8 family members bind to ADAM10 and may help it process substrates (e.g., Notch, Heparin Binding EGF Like Growth Factor (HB-EGF), and CD44). ⓑ CD9 and CD81 on the vascular endothelial cell membrane can promote leukocyte adhesion to the vascular endothelial cell surface by recruiting cell adhesion molecules, such as Intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), whereas ADAM10 has a hydrolytic effect on the extracellular domain of ICAM-1. ⓒ Tspan2 prevents

This protein is likely one of the most studied tetraspanins in the development of inflammation, and multiple studies have shown that CD9 is critical for controlling inflammation, reviewed in [117]. Research on the connection between CD9 and ADAM10 started in 2002 when Yan et al. [118] discovered that G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) activation increases the interaction of KUZ (ADAM10) and its substrate Heparin Binding EGF Like Growth Factor (HB-EGF) with CD9. It appears that CD9 regulates ADAM10 by promoting its protease activity; however, Cécile Arduise et al. (2008) [16] reported that an anti-CD9 antibody promotes the cleavage of substrates by ADAM10. Lu et al. (2020) [63] have found that antibodies against CD9 disrupt the association between CD9 and ADAM10. These findings suggest that the actual regulatory effect of CD9 on ADAM10 may be negative.

The regulatory relationship between ADAM10 and CD9 in sepsis remains unclear. When CD9 is knocked out, there is a significant increase in proinflammatory signaling and proinflammatory cytokine levels in the lungs of the mice. In addition, loss of CD9 function increases TNF-

Previous reviews have summarized the effects of CD81 on adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1 and integrins during leukocyte migration across the vascular endothelium and on leukocyte recruitment [122]. In the context of viral, bacterial, or Plasmodium infection, CD81 may function as an entry factor in the host organism [28]. Mo et al. (2024) [123] conducted a study using single-cell sequencing and transcriptome sequencing and identified seven key genes linked to sepsis development; specifically, they found that the expression of CD81 was negatively correlated with the expression of sepsis-related genes such as IL-10 and TLR4. Another study conducted by Chen et al. (2022) [124] on differentially expressed genes in sepsis and sepsis-induced ARDS revealed downregulation of CD81 expression in the latter. Subsequent cellular experiments demonstrated that CD81 overexpression mitigates LPS-induced injury in A549 cells and decreases the levels of proinflammatory cytokines in LPS-stimulated Jurkat cells [124].

In contrast to the extensive research on infection, investigations of the interaction between CD81 and ADAM10 are relatively limited. Arduise et al. (2008) [16], who first identified this interaction, reported that antibodies targeting CD81 increase the cleavage of the extracellular domains of pro-EGF and TNF-

In 2014, Otsubo C et al. [62] identified a connection between tspan2 and ADAM10 via immunoprecipitation and reported that tspan2 binds to CD44 and enhances its ability to scavenge ROS. We know that ADAM10 promotes the development of inflammatory responses by cleaving the extracellular domain of CD44. Otsubo and colleagues [62] proposed that the knockdown of tspan2 has a minimal effect on the cleavage of the CD44 extracellular domain and that the release of the CD44 extracellular domain remains unaffected by the ectopic expression of tspan2. However, the specific role of the interaction between ADAM10 and tspan2 in disease development was not investigated.

Both the Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK) and

In addition to the members of the two subfamilies mentioned above, several other tetraspanins have now been found to be associated with ADAM10, and they have not been assigned to specific subfamilies. Here, we explore their possible roles in sepsis together with the link to ADAM10 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Interactions between tetraspanins other than TspanC8 and members of the Tspan8 subfamily and ADAM10. ⓐ Tspan3 and tspan12 promote the extracellular domain cleavage of substrates (amyloid precursor protein (APP), notch) by ADAM10 on the cell membrane. ⓑ CD53 and CD151 can bind to other transmembrane proteins, respectively, and promote processing of ADAM10 precursors by Furin by increasing the inward flow of extracellular calcium ions, resulting in increased ADAM10 expression. Additionally, tspan12 can also bind to pro-ADAM10, thereby assisting the latter’s exit from the endoplasmic reticulum. ⓒ Enhanced hydrolysis of the extracellular domain of ADAM10 towards its substrate (TNF-

In inflammation, proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-

Antibodies targeting CD82 have been shown to induce the redistribution of ADAM10 on the cell membrane, leading to an increase in ADAM10-dependent TNF-

CD151 is widely expressed in various cell types, and studies have shown that it can directly influence leukocyte migration. CD151 on endothelial cell membranes recruits the vascular cell adhesion molecule VCAM-1 in the early stages of inflammation, which promotes leukocyte adhesion to vascular endothelial cells and facilitates subsequent leukocyte efflux into blood vessels [148]. However, cell adhesion is also promoted during infection by certain pathogens. E. coli, Neisseria meningitidis (N. meningitidis), and S. pneumoniae require CD9, CD63, and CD151 for adherence to and invasion of host cells [135]. HPV16 and Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) also require CD151-mediated endocytosis for the infection and invasion of cells [149, 150]. CD151 is considered a promising target for treating influenza and other viral infections because of its important role in viral infection-related signaling [151].

Research on the relationship between CD151 and ADAM10 is limited. However, the potential connection between these proteins in sepsis can be inferred from existing findings. Hypoxia contributes to deterioration in sepsis [152]. Hypoxia induces an increase in ADAM10 expression and inhibits CD151 expression [153, 154]. Intracellular Ca2+ flux is increased in sepsis models, promoting the activation of ADAM10 [69, 154]. Coincidentally, CD151 can regulate intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis [155]. The activation of the Wnt signaling pathway plays a significant role in sepsis [156]. Wnt signaling has been shown to potentially play a role in recruiting epigenetic complexes to facilitate the activation of ADAM gene transcription [66]. Deletion of the CD151 gene coincidentally leads to hyperactivation of the typical Wnt/

CD53 is expressed at lower levels in endothelial cells than other tetraspanins [19]. It is predominantly expressed in immune cells and bone marrow cells and plays a crucial role in the immune system by regulating immune cell development, adhesion, migration, and signaling [168, 169, 170, 171, 172]. This implies that it may play a nonsignificant role in immune dysfunction in sepsis. Studies have shown that the CD53 gene is upregulated in macrophages stimulated by LPS and that in humans, CD53 deficiency predisposes individuals to multiple recurrent infections [170, 173]. The expression of CD53 on monocyte subpopulations is negatively correlated with the viral load in untreated HIV-1-infected individuals [174]. CD53 gene expression is increased in the blood of patients with active tuberculosis (TB) compared with that of healthy controls and patients with latent TB [175]. Cytokine production and inflammatory signaling pathways are hyperactivated in response to inflammatory stimuli when CD53 is knocked down in human THP-1 monocytes [70]. These results suggest an important role for CD53 in infectious diseases and even sepsis.

Few studies have reported the association between CD53 and ADAM10 in inflammation or sepsis, but by reviewing the literature, we found that they may be linked. ADAM10, which plays an important role in sepsis, likewise plays a role in immunomodulation. For example, both ADAM10 deficiency and overexpression affect B-cell development and activation. Soluble CD23 released by ADAM10 cleavage induces macrophages to release proinflammatory cytokines. Notably, ADAM10 expressed on platelets plays a key role in regulating the immune response, reviewed in [176]. In immune cells, CD53 promotes BCR-dependent protein kinase C (PKC) signaling by recruiting PKC to the plasma membrane, enabling it to phosphorylate substrates [71]. Interestingly, PKC activation is one of the prerequisites for the activation of ADAM10 protease activity on the cell surface [72]. In addition, TNF-

Tspan12 is widely expressed in most human tissues and organs and most highly expressed in the digestive, genitourinary, and cardiovascular systems [181]. Xu et al. (2009) [61] utilized mass spectrometry to confirm the interaction between ADAM10 and tspan12 in various cells and reported a reduction in mature ADAM10 expression in cells lacking endogenous tspan12. Chen et al. (2015) [73] reported that the knockdown of tspan12 and tspan17 on CHO cell membranes reduces the formation of the ADAM10-

Although no association between tspan12 and ADAM10 has been found in sepsis, relevant studies have provided some evidence of such an association. Tspan12 expression is significantly downregulated in the inflamed esophageal endothelium. TSPAN12 gene silencing disrupts endothelial integrity and increases endothelial cell permeability. TNF-

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells and play a crucial role in triggering T-cell-mediated immune responses. In 2001, Tokoro et al. (2001) [187] reported that tspan3 on mouse dendritic cells is involved in T-cell initiation. Seipold et al. (2017) [60] reported that tspan3 can act synergistically with other tetraspanins to stabilize ADAM10 and

Despite the fact that there have been no studies on the effect of tspan3 on ADAM10 in sepsis, it can be hypothesized from the relevant literature that the two are linked in inflammatory diseases. First, both tspan3 and ADAM10 were found to contribute to coronavirus invasion [188, 189]. Second, DCs expressing tspan3 require ADAM10-mediated Notch signaling to produce cytokines that stimulate TH2 immune responses, and tspan3 can interact with claudin 11 (Cldn-11) to modulate ADAM10-mediated Notch signaling [75, 111]. Although the evidence is scarce, these clues suggest a possible synergistic effect of tspan3 with ADAM10 in sepsis.

The transformative integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in biomedical research has revolutionized the deconvolution of intricate protein interactomes, especially within inflammation-driven pathologies. The Tspan15-ADAM10 axis emerges as a sepsis regulator: Tspan15 directs ADAM10 to the cell membrane surface, selectively cleaving VE-cadherin, disrupting intercellular adhesion junctions, and exacerbating endothelial dysfunction [77, 190]. Structural insights into Tspan15-ADAM10 complexes offer a 3D topological framework for graph neural networks to simulate sepsis-related perturbations, predicting off-target substrate cleavage (e.g., APP, Notch) and cytokine storms [76].

Current limitations in characterizing ADAM10-tetraspanin interactions present prime targets for AI: (1) Structural Prediction: Deep learning (AlphaFold Multimer) enables de novo modeling of ternary complexes, resolving cryptic binding interfaces in sepsis-relevant TspanC8 members (e.g., Tspan15/33) [76]; (2) Multiomics Integration: Integration of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data with AI algorithms offers unprecedented opportunities to decode cell type-specific ADAM10-tetraspanin interactions. Xu et al. (2024) [191] demonstrated how machine learning applied to sepsis scRNA-seq data can identify critical hub genes within specific immune subsets. Extending this approach to analyze co-expression patterns of ADAM10 and tetraspanins across septic microenvironments could uncover context-dependent regulatory logic. Such analyses may resolve why identical tetraspanins exert opposing effects on ADAM10 substrate selectivity in different cell types [29, 58, 77]; (3) Therapeutic Design: Generative adversarial networks simulate tetraspanin web reorganization under toxin exposure, predicting allosteric nanobody sites. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) can predict the allosteric interface in the Tspan15-ADAM10 complex structure resolved by cryo-EM [76], perform mutation analysis in a virtual environment, and identify evolutionarily conserved residues (such as Glu94 and Trp145) as key contact sites for developing single-domain antibodies. By simulating toxin induction, reinforcement learning can optimize specific peptide segments targeting the tetraspanin web, selectively inhibiting toxin-enhanced ADAM10 activation [192].

ADAM10 plays a critical role in inflammation-related diseases, including sepsis, and is undoubtedly a key target for sepsis treatment. Owing to the wide range of actions of ADAM10, interventions that nonspecifically target ADAM10 inevitably cause some harm while also modulating inflammation. We need to find targets that regulate ADAM10 more specifically in certain diseases. Few studies and reviews available so far have discussed the association and role between ADAM10 and tetraspanins in the context of sepsis. In this paper, we explore the regulation and activation of ADAM10 by tetraspanins, as well as the potential implications of the interactions between ADAM10 and tetraspanins in the context of sepsis (Table 2, Ref. [22, 29, 51, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 62, 64, 70, 71, 74, 75, 77, 80, 82, 83, 84, 97, 98, 99, 110, 112, 117, 120, 122, 124, 135, 136, 138, 139, 140, 141, 144, 148, 149, 150, 152, 155, 157, 164, 165, 170, 181, 182]). The modulation of tetraspanins represents a promising approach for selectively targeting ADAM10 activity in sepsis and potentially minimizing the off-target effects associated with global ADAM10 inhibition.

| Tetraspanin | Possible vascular effects related to ADAM10 | Possible links to sepsis | Reference |

| Tspan5 | [22, 53, 80, 84] | ||

| Tspan10 | - | [82] | |

| Tspan14 | [51, 83, 110, 112] | ||

| Tspan15 | Affects Notch signaling | [29, 54, 55, 77, 97, 98] | |

| Tspan17 | [53] | ||

| Tspan33 | Marker of B-cell activation | [29, 54, 56, 57, 58, 99] | |

| Affects Notch signaling | |||

| CD9 | [64, 74, 117, 120, 122, 138, 139, 182] | ||

| CD81 | [122, 124] | ||

| Tspan2 | [62, 152] | ||

| Tspan12 | [74, 181] | ||

| Tspan3 | Regulation of Notch signaling | [75] | |

| CD82 | Marker of T-cell activation | [122, 135, 136, 140, 141, 144, 164] | |

| CD151 | [122, 135, 148, 149, 150, 155, 157, 164, 165] | ||

| CD53 | [70, 71, 170] | ||

| production | |||

Research on ADAM10 interaction partners has focused predominantly on various members of the tspanC8 subfamily. This is likely because these proteins were identified as some of few interaction partners capable of directly binding ADAM10 even in the presence of the strong detergents used in immunoprecipitation. Nevertheless, there is inconsistency in the literature because researchers use different detergents with varying compositions at different concentrations. The ability of fluorescence colocalization analysis to confirm direct protein interactions is limited. With the exception of tetraspanins that have been subjected to coprecipitation experiments following cleavage with strong detergents such as 1% digitonin and/or 1% Triton X-100, as well as tetraspanins for which the type of interaction with ADAM10 have been verified via cryo-EM, we are not able to confirm whether other tetraspanins interact with ADAM10 directly or indirectly. Additional research is required to confirm the nature of these interactions. For example, techniques such as fluorescence in situ hybridization and fluorescence energy resonance transfer are promising tools for studying protein interactions and can be used to unambiguously identify tetraspanins that bind directly or indirectly to ADAM10.

Research investigating the interaction between tetraspanin and ADAM10 in the pathogenesis of sepsis is currently lacking. ADAM10 cleaves inflammatory factors such as TNF-

Tetraspanins regulate their interaction partners mainly in locally formed nanodomains (i.e., tetraspanin-enriched microdomains). Therefore, the interactions among different proteins within these microdomains play crucial roles in regulating the activity of ADAM10. After confirming interactions between tetraspanins and ADAM10, we should investigate how multiple tetraspanins in tetraspanin-enriched microdomains work together to regulate ADAM10. Elucidating this mechanism may provide insight for the more precise regulation of ADAM10 activity for the treatment of sepsis.

In addition, single-cell RNA sequencing has been used to reveal cellular transcriptomic changes in sepsis-associated injuries [123, 193, 194]. To definitively establish the cell-specific roles of tetraspanins in regulating ADAM10 during sepsis, future studies should prioritize scRNA-seq of clinical samples, with a targeted analysis of ADAM10-tetraspanin co-expression across relevant cell types (e.g., endothelial cells, macrophages, T and B lymphocytes). Integration with spatial transcriptomics could further map these interactions within tissue microenvironments affected by sepsis, such as the lung and kidney. Such approaches would validate hypothesized cell-contextual mechanisms and identify novel therapeutic targets tailored to specific cellular compartments [193, 194]. Given the current understanding of the direct interactions between members of the TspanC8 subfamily and ADAM10, studying the pathophysiological changes associated with these proteins in sepsis holds promise. In conclusion, future research should focus on identifying the specific substrates cleaved by different tetraspanin/ADAM10 complexes in sepsis to aid the development of precision targeted therapies.

ADAM10, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; AKI, acute kidney injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; APP, amyloid precursor protein; AI, artificial intelligence; BCR, B-cell receptor; CHAPS, 3-[(3-Chloamidopropyl)dimethyl-ammonium]-1-propanesulfonate; CX3CL1, C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1; CXCL16, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 16; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; CLP, cecal ligation and puncture; Cldn-11, claudin 11; DLL1, deita-like protein 1; E. Coli, Escherichia coli; cryo-EM, cryo-electron microscopy; DCs, dendritic cells; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EPS8, Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Pathway Substrate 8; EGR1, Early Growth Response 1; EoE, Eosinophilic esophagitis; E. tenella, Eimeria tenella; FASL, Fas ligand; HA, hyaluronic acid; GANs, generative adversarial networks; GWAS, genome-wide association studies; EPCR, endothelial cell protein C receptor; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; GPVI, Glycoprotein VI; GRB2, growth factor receptor-bound protein 2; HTLV-1, Human T-lymphotropic virus 1; HB-EGF, Heparin Binding EGF Like Growth Factor; IL-10, Interleukin-10; HPV16, human papilloma virus 16; HCMV, Human cytomegalovirus; H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; ICAM-1, Intercellular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1; ICC, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; IgAN, Immunoglobulin A nephropathy; IL-6, Interleukin-6; IL-1

Conceptualization, JH and YS; Writing–original draft, MY and YL; Literature search, MY, YL, YH, SL, YQ, and LL; Writing–review & editing, JH and YS; Supervision, JH and YS; Funding acquisition, JH and YS. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (82072151, 82302446), Regional Joint Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023A1515140177, 2024A1515012890), Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University Clinical Research Program (LCYJ2019A002) and Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhanjiang) (ZJW-2019-007).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.