1 Department of Hematology, The First Hospital of China Medical University, 110001 Shenyang, Liaoning, China

2 Department of Geriatrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, 110001 Shenyang, Liaoning, China

3 Anhui Province Key Laboratory of Medical Physics and Technology, Institute of Health and Medical Technology, Hefei Institutes of Physical Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 230031 Hefei, Anhui, China

4 Science Island Branch, Graduate School of USTC, 230026 Hefei, Anhui, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technology, also known as single-cell transcriptome sequencing, has become a key tool in biology and medicine, enabling deeper insights into cellular diversity and disease mechanisms. Since 2009 when scRNA-seq technology was first introduced, many technologies have been developed and improved, with a wide range of applications in haematopoietic malignancies, solid tumours, and other fields. These technologies have been used by researchers to map transcriptomes, study intra- and inter-cellular heterogeneity, investigate tumour microenvironments, analyse specific cellular subpopulations, and assist in clinical studies. This review categorises scRNA-seq on the basis of different single-cell amplification techniques, provides an overview of the principles of currently commonly used scRNA-seq techniques, discusses the application of scRNA-seq in the context of haematopoietic malignancies, and will hopefully play a role in the future development of single-cell sequencing technologies.

Keywords

- transcriptomes

- hematopoietic malignancies

- RNA sequencing

Despite substantial progress in cancer treatment, haematologic malignancies remain a major cause of death among middle—aged and elderly people globally. These cancers stem from abnormal proliferation and differentiation of haematopoietic stem or progenitor cells. The resulting heterogeneous malignant cell populations pose significant challenges to diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

While traditional bulk RNA sequencing has played a crucial role in gene expression research, it falls short at fully uncovering the underlying mechanisms of these malignancies. This is because cell populations usually contain different cell types or subtypes, and so cannot be profiled using population-based analysis. In addition, co-expression patterns between genes in cells are lost at certain critical points in sequencing [1]. Furthermore, signals driving tumourigenesis and drug resistance in specific cells may be masked by the average gene expression profiles [2]. Therefore, analysing gene expression at the single-cell level is essential for a comprehensive understanding of gene regulation in cells, and so single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged [3].

RNA sequencing has evolved from traditional bulk RNA sequencing to scRNA-seq and, more recently, to spatial RNA sequencing (spRNAseq) [2]. Bulk RNA-seq quantifies gene expression in cell populations by analysing total RNA from tissues or cells [4]. This technique is invaluable in uncovering biological markers, studying tumour heterogeneity, and investigating the tumour microenvironment (TME) with significant advantages [5], and this technique proves invaluable in uncovering biological markers, studying tumour heterogeneity, and investigating the TME with significant advantages [6].

The emergence and rapid development of single-cell technologies marks a significant advance in cancer research. These innovations allow for a deeper understanding of cellular heterogeneity, facilitate the analysis of the TME, and help to identify secondary cell populations (which were previously challenging to detect and characterise), and extrapolate cell–cell interactions at the single-cell level [7, 8, 9, 10]. In this review, we categorise scRNA-seq techniques based on different amplification methods, outline the key steps involved in these approaches, and delve into the applications of single-cell transcriptomics in haematopoietic malignancies. We also discuss the latest advancements, challenges, and future directions in this exciting field.

Early single-cell sequencing was designed to study a limited number of cells [11, 12]. However, using real-time quantitative PCR experiments on more than 500 cells, Guo et al. [13] discovered that different cell types could be categorised without sorting the cells. This finding not only supported the feasibility of high-throughput cell analysis but also spurred subsequent researchers to advance high-throughput scRNA-seq technologies. Since the 1990s, single-cell amplification techniques have evolved from basic PCR and real-time quantitative in vitro transcription (IVT) to more recent non-targeted single-cell mRNA amplification methods. Building on this progress, Tang et al. [14] developed single-cell transcriptome sequencing technology for the first time in 2009, followed by Islam et al. [15] who pioneered single-cell tagged reverse transcription sequencing (STRT-seq) using barcode labelling. The advent of barcoding was a pivotal moment in single-cell analysis, as it allowed for large-scale parallelisation and significantly reduced sequencing costs [16]. As a result, sequencing just a handful of cells was no longer sufficient to meet the demands of studying complex tissues. High-throughput, high-precision scRNA-seq gradually became the mainstream approach. In 2016, 10X Genomics® and, in 2019, DNBelab C4 further demonstrated that scRNA-seq is progressing towards greater portability and lower costs [17, 18].

Single-cell transcriptomics holds the promise to revolutionise both biological research and clinical practice, enabling unbiased and comprehensive cellular characterisation [19, 20, 21]. However, given that it is not yet possible to sequence RNA directly from individual cells, all current single-cell sequencing methods are invariably DNA-based. This means that RNA must be converted into cDNA first, and then amplified by PCR or IVT. This process brings two significant challenges: minimising RNA loss and ensuring sufficient DNA is available for sequencing after amplification.

The primary distinctions between scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq lie in their sample types, sensitivity, complexity, data handling, and areas of application [4] (Table 1, Ref. [4, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]). Recent studies have demonstrated that combining bulk RNA-seq with scRNA-seq can be more cost-effective and yield more accurate analysis results, and it allows for more effective batch effect studies than using a sequencing method alone. This synergy between scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq holds promise as a key strategy for advancing transcriptome sequencing technologies, offering a new frontier for comprehensive and nuanced gene expression analysis [4, 28].

| scRNA-seq | Bulk RNA-seq | |

| Cost | High | Low |

| Application | Expressions of the genes within each cell | Average gene expressions level |

| Sample requirement | High | Low |

| Sensitivity | High | Low |

| Complexity | High | Low |

| Amount of data obtained [4] | More | Less |

| Sample source [22, 23, 24] | Single cell | Total RNA |

| Sample preparation [25, 26] | Fresh samples preferred | No special requirements |

| Data analysis complexity [27] | High | Low |

| Technical challenges | High | Low |

| Relevance to clinical applications | High | Moderate |

| Sequencing depth | 50,000–1,000,000 reads/cell (6–8G) | 20–50 million reads/sample |

| Cell viability threshold | No special requirements |

scRNA-seq, single-cell RNA sequencing.

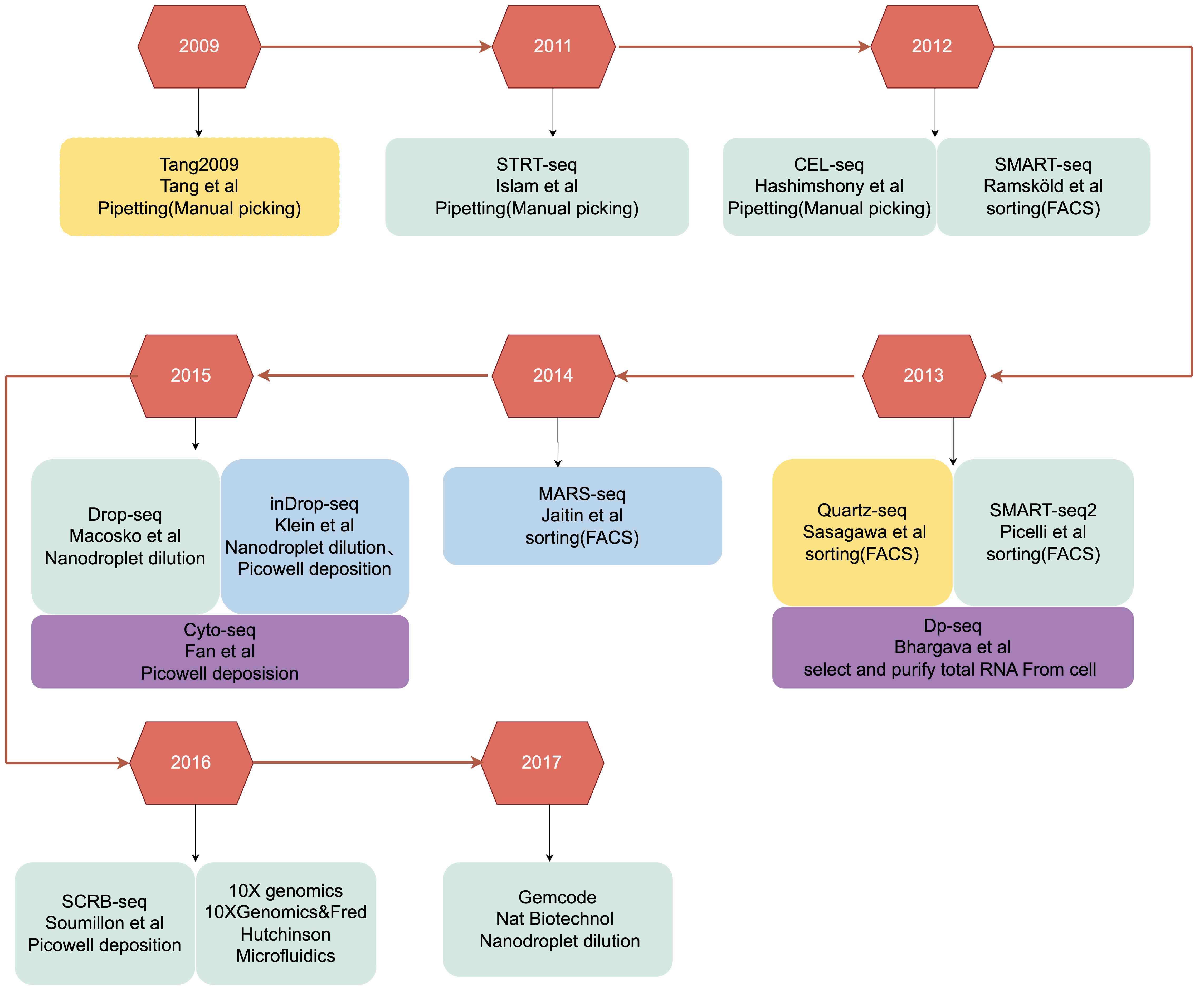

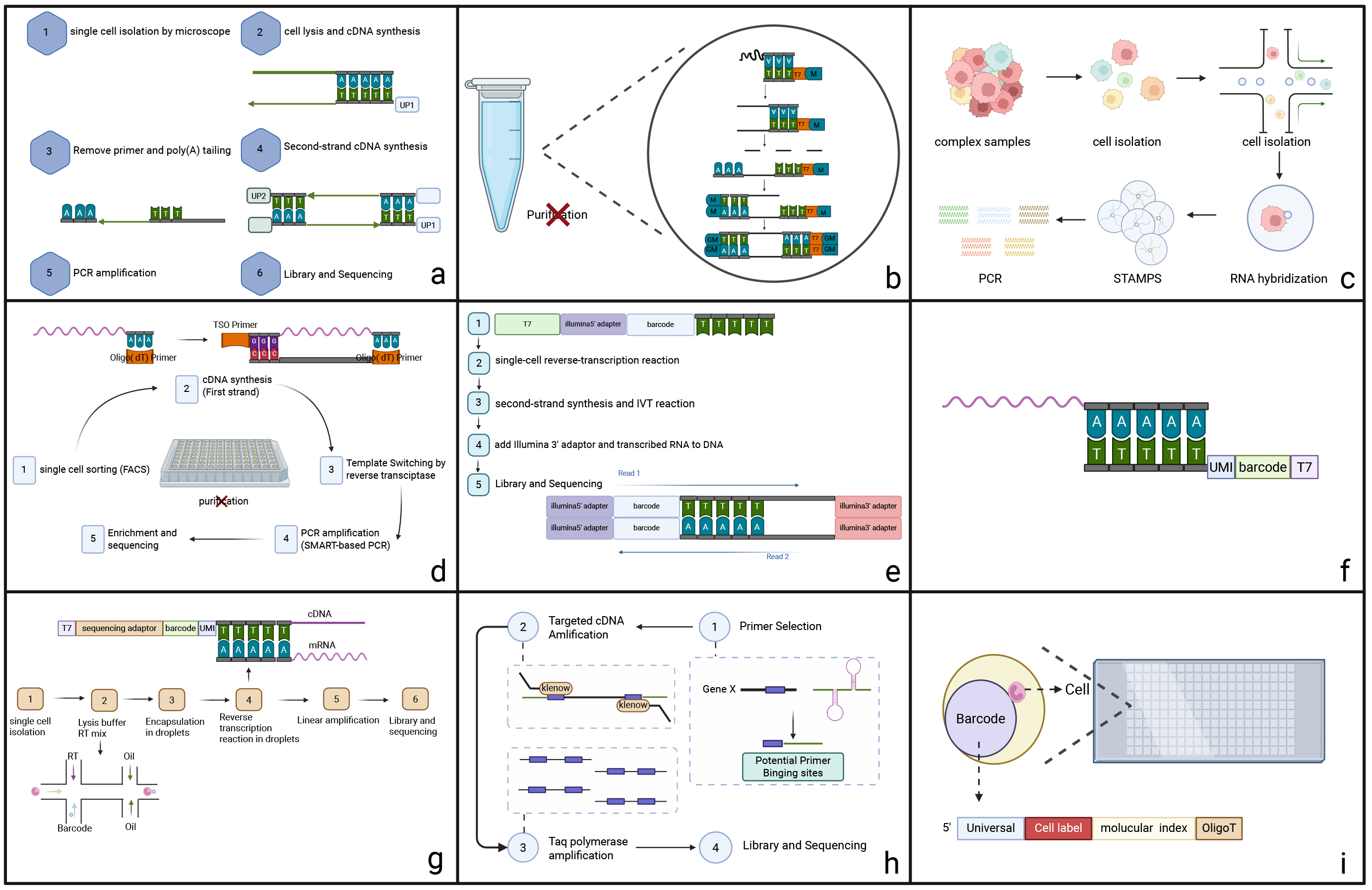

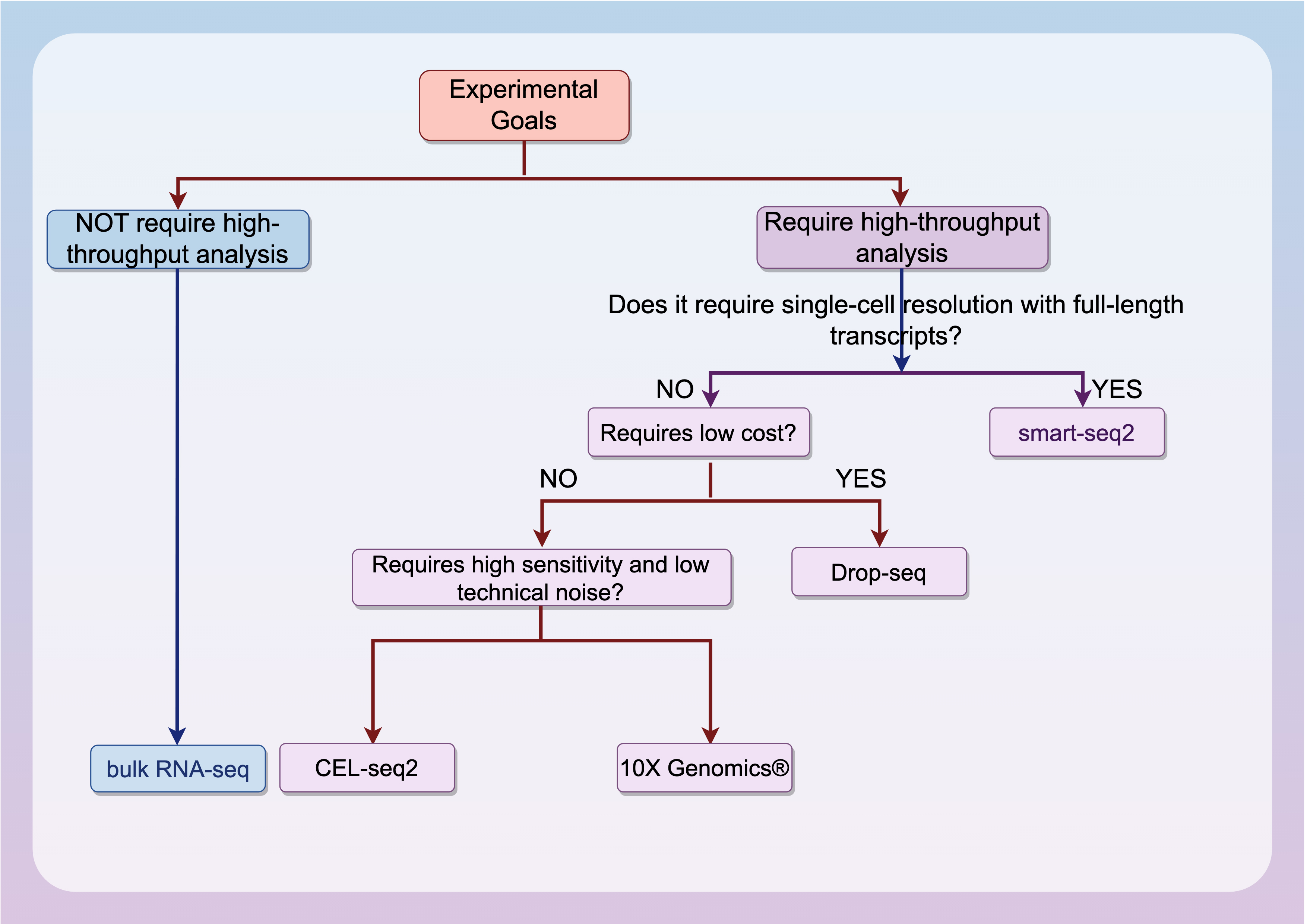

Based on the amplification techniques used, scRNA-seq can be broadly classified into several categories (Fig. 1). In this article, we will focus on one or two representative methods from each category to provide a comprehensive overview of the current approaches (Fig. 2), we also provided a decision diagram to facilitate researchers in selecting appropriate scRNA-seq methods based on their specific needs (Fig. 3). Meanwhile, methods mentioned in this review such as Tang (2009), cell expression by linear amplification and sequencing (CEL-seq), massively parallel single-cell RNA sequencing (MARS-seq), designed primer-based RNA-sequencing (DP-seq), and Cytoplasmic Sequencing (Cyto-seq) still require laboratory-specific protocol optimization and have not been developed into standardized commercial products. In contrast, 10X Genomics® is a mature commercial technology based on the principles of single-cell high-throughput droplet sequencing (Drop-seq)/InDrop, and switching mechanism at 5′-end of the RNA transcript (Smart-seq2) is also a commercially mature technology.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The development of single-cell RNA sequencing. The text from top to bottom introduces the sequencing method, the author or research institution, and the single-cell isolation method. Different colours represent different single-cell amplification methods: yellow, homopolymer tail-based PCR; green, SMART-based PCR; blue, IVT-based linear amplification; and purple, DP-based PCR. STRT-seq, single-cell tagged reverse transcription sequencing; CEL-seq, cell expression by linear amplification and sequencing; SMART-seq, switching mechanism at 5′-end of the RNA transcript; Quatz-seq, Quantitative and Universal RNA-seq Technology for Single-cell; Dp-seq, designed primer-based RNA-sequencing; FACS, Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting; MARS-seq, massively parallel single-cell RNA sequencing; Drop-seq, single-cell high-throughput droplet sequencing; Cyto-seq, Cytoplasmic Sequencing; SCRB-seq, Single-Cell RNA Barcoding and sequencing; IVT, In Vitro Transcription.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Summary of the Brief Principle and Innovative Technologies of scRNA-seq. (a) Tang2009, (b) Quartz-Seq, (c) Drop-seq (single-cell high-throughput droplet sequencing), (d) Smart-seq2 (switching mechanism at 5′-end of the RNA transcript), (e) CEL-seq (cell expression by linear amplification and sequencing), (f) MARS-seq’s three levels of barcoding, (g) InDrop-seq, (h) DP-seq (designed primer-based RNA sequencing), and (i) Cyto-seq (gene expression cytometry RNA sequencing)’s random barcoding of single cells. scRNA-seq, single-cell RNA sequencing.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Decision diagram of the scRNA-seq.

As the pioneering scRNA-seq method, Tang et al. [14] in 2009 (Fig. 2a) manually aspirated and isolated single cells under a microscope, using poly(T) primers with anchoring sequences to generate unbiased cDNAs, and using emulsion PCR to provide a separate PCR space for the samples, allowing low-concentration DNA to be amplified in a large number of PCR cycles. The independent “water-in-oil” amplification environment prevented cross-contamination between samples, allowing for cleaner and more reliable sequencing results. However, due to technical limitations, this method cannot detect mRNAs without poly(A) tails or accurately distinguish between positive and negative transcripts.

Quartz-Seq (Fig. 2b), introduced in 2013 by Sasagawa et al. [29], represents a significant leap forward in whole-transcript amplification (WTA) technology, and more powerful PCR enzymes allows the experiments to be performed in a single PCR tube. The key advantage of Quartz-seq is the use of nucleic acid exonuclease. This combination of Nuclease I, restriction poly-A tailing, and optimised inhibited PCR drastically reduces by-product generation, eliminates purification steps, improves cDNA yield and reproducibility of WTA replicates, and provides high sensitivity and quantitative performance. However, noise and underrepresentation still existed when dealing with specific transcripts.

As sequencing costs continue to drop and procedural steps become more streamlined, scRNA-seq has rapidly emerged as the go-to method for transcriptomics analysis, gradually replacing microarrays. However, traditional single-cell amplification methods relying on the poly(A) tailing reaction face a significant hurdle: they tend to produce excessive by-products and suffer from a high rate of contamination in the junction sequences [14, 29].

In 2015, Drop-seq (Fig. 2c) revolutionized single-cell RNA sequencing by integrating microfluidics with molecular barcoding technology [30]. Macosko et al. [30] designed a microfluidic “co-fluidic” device that encapsulates individual cells and barcoded beads into droplets, generating thousands of single-cell transcriptomes attached to beads (STAMPs) per hour [31]. This approach, as detailed in their study, enables high-throughput indexing of single-cell transcriptomes for parallel sequencing, distinguishing cellular origins through unique molecular barcodes. The main advantages of Drop-seq are its short experimental time and low cost, which enable the generation of a large number of scRNA-seq libraries at a low cost. The experimental cost is approximately $0.10 per cell, making it the most cost-effective single-cell RNA sequencing method at the time [32]. Currently, Drop-seq is widely used for single-cell transcriptome analysis in various fields [33, 34, 35, 36].

Smart-seq2 (2013) (Fig. 2d) represents an advanced iteration of Smart-seq (2012) that offers superior read coverage, sensitivity, and accuracy through the use of template-switching single-cell amplification technology. The incorporation of off-the-shelf reagents has the potential to reduce sequencing costs. Experiments have shown that Smart-seq2 not only increases the average length of cDNAs but also greatly enhances the ability to detect gene expression with greater precision. Additionally, there has been a reduction in the technical difficulty of low- and medium-abundance transcripts, and avoidance of the 3′-bias common to many sequencing methods [32]. However, it is important to note that Smart-seq2 also has limitations, lacking of strand-specificity and the inability to detect nonpolyadenylated RNAs [37]. The success of Smart-seq2 has also helped other single-cell methods that rely on template switching [38]. Smart-seq2 has become a popular choice for use in conjunction with other sequencing methods as a multi-omics tool in clinical or life science research [39, 40, 41]. Smart-seq3 (2020) offers a unique combination of full-length transcriptome coverage with a 5′ unique molecular identifier (UMI) RNA counting strategy, enabling the detection of thousands of additional transcripts for more efficient sequencing [42].

CEL-seq (2012) (Fig. 2e) was a breakthrough in scRNA-seq, as it uses a linear amplification approach to address the challenge of limited RNA content in samples [43]. The technique works by using a round of in vitro transcription to amplify mRNA in a linear fashion by barcoding and mixing samples. The CEL-Seq significantly improves reproducibility, linearity, and sensitivity, detects more genes in a single cell, and reduces sequencing errors. However, it does have some drawbacks, notably a strong 3′-bias and lower sensitivity for detecting low-expression transcripts [44]. The 3′-bias refers to the high proportion of fragments close to the 3′ end of the mRNA in sequencing data, while there is a significant loss of information from the 5′ end. The main reasons for this bias are the dropout of reverse transcriptase and the limitations of in vitro transcription. In hematological tumor research, this may lead to two types of critical errors: Quantitative bias of long genes: For example, the 5′ breakpoint sequence of the Mixed Lineage Leukemia (MLL) fusion gene (full-length ~15 kb), which is common in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), may be missed due to platform preference, leading to misjudgment of fusion events; Limitations in alternative splicing identification: Genes such as BCL2L12 associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia produce pro-apoptotic/anti-apoptotic isoforms through alternative splicing, but 3′-preferential platforms may fail to distinguish key 5′ splicing variants. The currently proposed solutions include: improving reverse transcriptase and adopting full-length sequencing methods (such as Smart-seq3) [42]. An improved version of the method, CEL-Seq2 (2016), offers a threefold increase in sensitivity. This version is not only more cost-effective but also requires less manual handling time, and the introduction of UMI methodology has significantly reduced bias [43, 45].

Massively parallel scRNA-seq (MARS-seq, 2014), modified from CEL-seq, is a fully automated method that uses three levels of barcoding (molecular, cellular, and plate labels) to facilitate molecular counting and highly multiplexed analyses [46] (Fig. 2f), which in combination with unsupervised classification algorithms, allow for the modelling of single-cell transcriptional states of dendritic cells (DCs) and other haematopoietic cells, revealing rich cell type heterogeneity and gene module activity. The advantages of MARS-seq are mainly the low amplification bias and labelling errors, high throughput, and reproducibility, making it particularly suitable for studying haematopoietic stem cells or other complex tissue samples in the haematopoietic system. However, to ensure the analysis of rare subpopulations, at least thousands of cells are required [44].

InDrop-seq (2015) (Fig. 2g) also utilises microfluidics to isolate single cells, and while there is no limit to the number of cells in the sample in principle, the depth and cost of sequencing is compromised when sample cell counts are in the tens of thousands. However, InDrop-seq is more advantageous when analysing very small amounts of tissue samples or when custom protocols are required [47]. InDrop-seq’s main challenges are ensuring that each droplet carries primers that encode a different barcode, and overcoming the limitations of mRNA capture efficiency and the random barcode strategy [48]. InDrop-seq has one of the cleanest noise profiles for its time, but among microfluidics-based scRNA-seq methods, 10X Genomics® (2016) has the best sensitivity and lowest technical noise at the highest overall cost [47].

Designed primer-based RNA sequencing (DP-seq, 2013) (Fig. 2h) [49] uses a defined set of heptamer primers to amplify the majority of expressed transcripts from a limited set of mRNAs, thereby providing a reliable representation of the relative abundance of these transcripts. It is specifically optimised to minimise issues such as primer mis-hybridisation (partial complementarity between primers and non-target sequences leads to incorrect hybridization) and primer dimer formation, making it well suited for detecting a wide array of lowly expressed transcripts. The DP-seq libraries can cover more than 80% of expressed transcripts, though biases remain in the cDNA amplification phase.

Gene expression cytometry (Cyto-seq, 2015) (Fig. 2i) integrates next-generation sequencing with random barcoding of single cells, enabling each mRNA molecule within the cell to be uniquely labelled, allowing routine digital gene expression profiling of thousands of single cells simultaneously without the use of robotics or automation [50]. Cyto-seq is less demanding on cell samples, and can even yield better results in samples with as little as 50% cell viability, which is particularly well-suited to process challenging clinical samples. However, achieving the desired sequencing depth requires a large number of cells, and the associated resource and time demands are relatively high. Consequently, it is mainly used for pre-defined gene analysis to reduce costs [44].

Single-cell RNA sequencing has transformed biological research by facilitating gene expression analysis at the single-cell resolution. This technology offers in-depth understanding of cellular heterogeneity, enabling the identification of rare cell populations, elucidation of cell developmental processes, and exploration of disease etiologies. Nevertheless, scRNA-seq data analysis entails distinct computational challenges, prompting the development of diverse analytical tools [27, 51].

Data Preprocessing Tools: Preprocessing is a crucial first step in scRNA-seq data analysis. Cell Ranger, developed by 10x Genomics, is a widely adopted tool for this task. It demultiplexes raw sequencing reads, aligns them to a reference genome, and counts gene-mapping reads [52]. Another popular choice is Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR), renowned for its fast and accurate read alignment. STAR efficiently handles the large number of short reads from scRNA-seq experiments and generates a gene expression matrix for downstream analysis [53].

Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering Tools: Given the high dimensionality of scRNA-seq data, dimensionality reduction techniques are crucial for data visualization and clustering. t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) are popular methods. In R, Seurat integrates these algorithms. It offers functions for normalization, dimensionality reduction, and cell clustering [54, 55]. In Python, Scanpy efficiently processes large-scale single-cell data, providing tools for clustering and differential expression analysis [56].

Trajectory Inference Tools: To understand the developmental processes or cellular transitions, trajectory inference tools are employed. Monocle, a renowned R-based tool, can order cells along a developmental trajectory by analyzing temporal changes in gene expression [57]. Similarly, Slingshot, also an R-based application, can identify branching trajectories and infer the pseudotime of cells [58]. In the Python ecosystem, Palantir stands out as a powerful trajectory inference tool. It utilizes a graph-based approach to model cell transitions, enabling it to handle complex biological systems effectively [59].

Technical noise: scRNA-seq data suffer from technical noise. Dropout events, where expressed genes go undetected, distort gene expression profiles. Moreover, cell-to-cell variations in sequencing depth and batch effects from experimental differences complicate analysis. Mitigating these requires advanced normalization and correction methods. Selecting the optimal approach for a given dataset remains a key challenge [60, 61].

Computational complexity: analyzing scRNA-seq data often involves handling large datasets with millions of cells. The computational resources required for tasks like data preprocessing, dimensionality reduction, and clustering can be substantial. As the size of scRNA-seq datasets continues to grow, developing more efficient algorithms and scalable computational methods is essential. Moreover, integrating data from multiple sources or modalities, such as combining scRNA-seq with spatial transcriptomics data, further increases the computational complexity [62, 63].

Biological interpretation: interpreting scRNA-seq data within a biological framework presents significant challenges. Cell type and state identification are complicated by cellular heterogeneity and external factors, with current annotation algorithms proving inadequate [64]. Regulatory network inference necessitates data integration but is hindered by technical complexity and gene expression variability. Connecting gene expression changes to biological processes is arduous, and the absence of standardized analysis protocols exacerbates result interpretation [65].

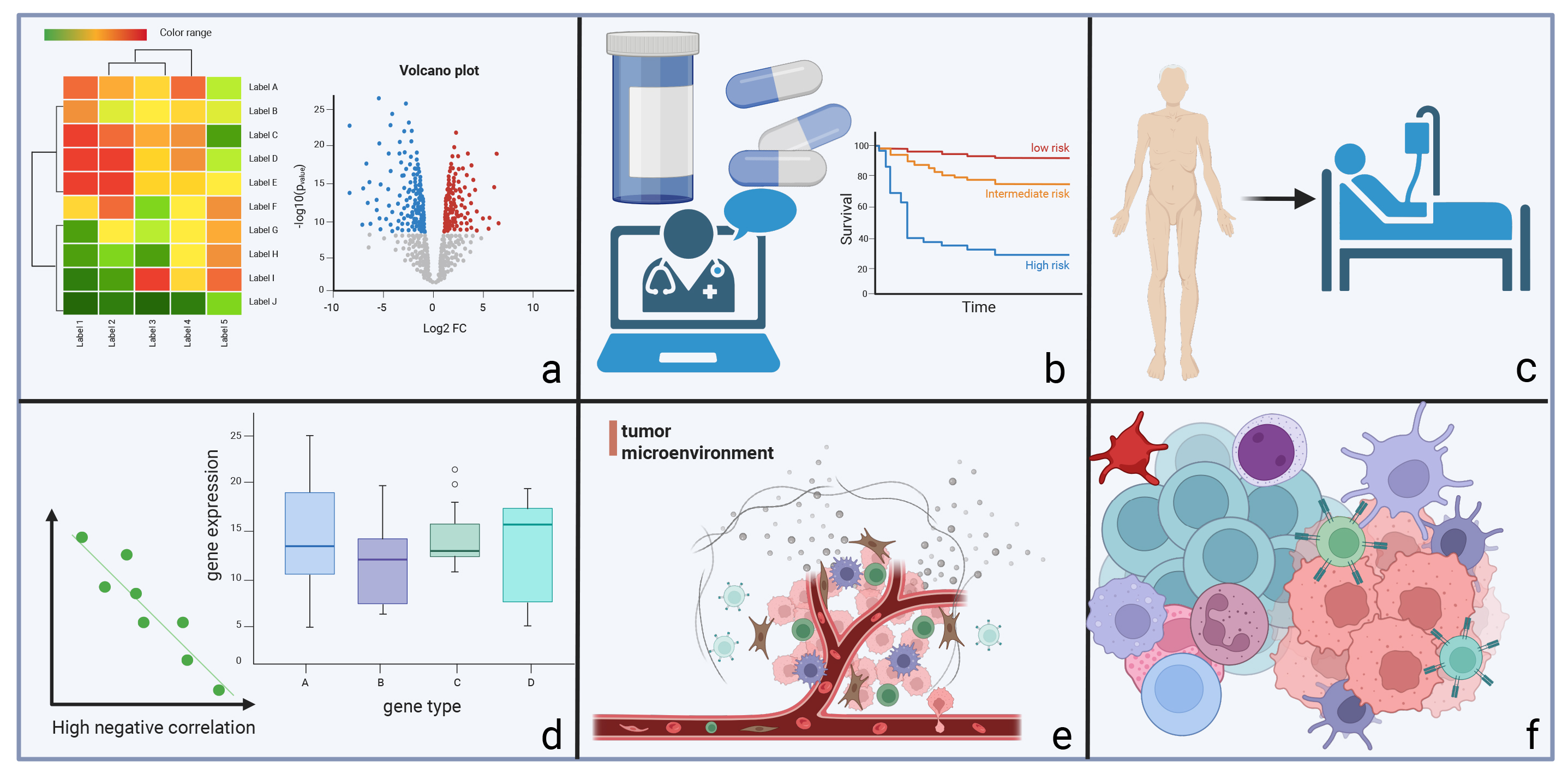

Since its introduction in 2009, scRNA-seq technology has been continuously developed [66], enabling high-throughput transcriptome sequencing analysis of tumour cells at the single-cell level. The application of scRNA-seq in malignant tumours has been widely recognised (Fig. 4) [67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72], and the current applications in haematopoietic malignancies have also attracted considerable attention. Typical applications of scRNA-seq in haematopoietic malignancies include mapping the transcriptome, studying intra- and inter-cellular heterogeneity, investigating the TME, analysing specific cell subpopulations, and supporting clinical research. Examples are given in Table 2 (Ref. [73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80]) for different types of haematopoietic malignancies.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. The main applications of single-cell RNA sequencing in malignant tumours. (a) analysis of tumour and cellular heterogeneity, (b) contribution to the study of clinical diagnosis and treatment, (c) study of disease progression and drug resistance mechanisms, (d) in-depth study of pathogenesis, (e) analysis of the tumour microenvironment, and (f) study of specific types of cell subpopulations.

| Disease Type | Key Techniques & Methods | Core Application Directions | Classic Examples and References |

| Acute Leukaemia | 10X Genomics®, SMART-seq2, Seq-Well, CITE-seq, SMART-seq2&Muta-seq | 1. MRD heterogeneity and immune microenvironment | MRD status and key nodes regulating MRD status after chemotherapy in B-ALL [73] |

| 2. Immune evasion and T-cell function | AML hierarchies relevant to disease progression and immunity [74] | ||

| 3. Stem cell identification and multi-omics integration | |||

| 4. Clinical drug resistance mechanisms | |||

| MDS | 10X Genomics® | 1. Quiescent state of stem cells and immune deficiency | Properties of myelodysplastic syndrome stem cells [75] |

| 2. TLR signaling and inflammatory microenvironment | Bone marrow-confined IL-6 signaling mediates the transformation of MDS into AML [76] | ||

| 3. LncRNA regulation of hematopoiesis | |||

| 4. IL-6-driven disease transformation | |||

| Lymphoma | 10X Genomics®, spatial transcriptomics, CyTOF | 1. Spatial heterogeneity of tumor microenvironment | To reveal the markers of disease progression in primary cutaneous |

| 2. Clonal plasticity and non-malignant cell crosstalk | T-cell lymphoma [77] | ||

| 3. Metabolic reprogramming in drug-resistant clones | Tissue Compartment-Specific | ||

| Plasticity of MF Tumor Cells [78] | |||

| Myeloma | 10X Genomics®, scVDJ-seq, long-read sequencing, MARS-seq | 1. Immune cell defects in pre-malignant stages | Immunologic changes during MM disease progression [79] |

| 2. Clonal evolution and microenvironmental metabolic symbiosis | Clonal diversity and prognostic genes in relapsed MM [80] | ||

| 3. Hypoxia- and metabolism-driven drug resistance |

MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; Smart-seq2, switching Mechanism at 5′ End of RNA Template sequencing 2; MARS-seq, massively parallel single-cell RNA sequencing; MRD, minimal residual disease; TLR, toll-like receptor; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; MM, multiple myeloma.

Minimal residual disease (MRD), the small population of leukaemia cells persisting after complete remission, has phenotypic and genetic similarity to the original tumour cells [81]. The MRD is often considered as associated with cancer dormancy [82], and helps researchers and clinicians to identify the prognostic status of malignant tumours [81, 83]. Traditional MRD detection methods, including flow cytometry and PCR, struggle to capture residual cell heterogeneity. They often miss rare, drug-resistant clones, risking disease burden underestimation. Single-cell RNA sequencing addresses these limitations. Zhang et al. [73] combined it with B-cell receptor sequencing in pediatric B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), revealing MRD cells with stem-like traits and epigenetic plasticity that enable chemoresistance. Targeting their unique signatures is vital for long-term remission. Hunter et al. [84] used the technique to study B-ALL’s immune microenvironment and found MRD presence correlated with immune deficits at diagnosis. Marked by upregulated checkpoint molecules and suppressed cytokines, this state reversed with recombinant IL-12, enhancing T-cell killing of MRD cells. By integrating scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq (Single-Cell Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with sequencing), an HSPC-like blast subpopulation with multipotent potential and MRD relevance has been identified in AML, B-ALL, and T-ALL [85].

The evasion of immune elimination by leukemia cells represents a central mechanism driving disease progression and relapse. This process primarily relies on the systemic remodeling of bone marrow cellular composition and soluble factor networks, which disrupt antigen presentation and immune recognition. Dysregulation of cytotoxic T cell function is also critical for immune evasion [86, 87, 88, 89]. A seminal study by Hunter et al. [84] utilized 10X Genomics® to demonstrate that the activation pathways of T cells and dendritic cells (DCs) are significantly impaired within the TME of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) patients. Notably, IL-2 treatment exacerbated the expression of immune exhaustion-related genes, suggesting that IL-12-mediated immunomodulation may be more effective in reversing immune suppression in B-ALL. Anand et al. [90] employed single-cell RNA sequencing to uncover the dynamic plasticity of early T cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ETP-ALL), where oncogenic transformation co-evolves with immune evasion programs, offering novel therapeutic targets.

Despite significant advancements in understanding solid tumor microenvironments enabled by scRNA-seq [91, 92], the molecular mechanisms of the bone marrow immune microenvironment in acute leukemia remain poorly understood. To address this gap, Witkowski et al. [86] applied CITE-Seq technology to analyze bone marrow mononuclear cells from primary B-ALL patients and healthy donors, generating a comprehensive dynamic atlas of the bone marrow immune microenvironment from diagnosis to relapse. This study identified key immune cell subsets and cytokine networks regulating leukemia cell survival. Anderson et al. [93] further demonstrated in a murine model that the development of normal pro-B and pre-B cells is disrupted at the early stage of B-ALL, highlighting the critical role of the hematopoietic stem cell niche in leukemogenesis. Mumme et al. [94] deepened our understanding of the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment by longitudinally analyzing bone marrow samples from AML patients at diagnosis, remission, and relapse stages. Their study revealed that relapse-associated AML cells highly express fatty acid oxidation genes and identified differentially expressed genes associated with patient survival prognosis [94]. Collectively, these findings underscore the systemic remodeling of the bone marrow microenvironment as a fundamental basis for leukemia immune evasion, providing a theoretical framework for developing microenvironment-targeted combination therapies.

There is a crucial role of T-cells in development of acute leukaemia, and they exhibit anti-leukaemic activity and allow prediction of disease relapse [95, 96]. Tracy et al. [97] employed CITE-Seq to analyze human bone marrow biopsy samples, aiming to elucidate the mechanisms underlying CD4+ T-cell exhaustion-induced disease relapse. The study examined the changes in multiple CD4+ T-cell subpopulations during the onset and treatment of B-ALL and identified unique CD4+ T-cell subpopulations with both cytotoxic and helper functions induced by B-ALL. Notably, helper/cytotoxic-depleted CD4+ T-cell subsets were detected in patients at the early diagnostic stage, indicating that CD4+ T cells are key drivers of the protective anti-leukemia immune response.

To further investigate depleted T-cell subpopulations, Wang et al. [98] performed scRNA-seq on sorted peripheral blood T cells, constructing transcriptome profiles of healthy individuals and B-ALL patients. The study uncovered previously unrecognized T-cell subpopulations and common activation patterns in B-ALL [98]. Two distinct subclusters of depleted T-cell were identified in B-ALL patients, and ten additional subclusters were further characterized, suggesting that highly clonally expanded depleted T-cell clusters may originate from CD8+ effector memory/terminal effector cells. These findings provide new insights into the role of T-cell subpopulations in leukemia immune evasion and lay a theoretical foundation for the development of T-cell function-targeted therapeutic strategies.

Cancer stem cells are pivotal drivers of tumor initiation, progression, recurrence,and drug resistance [99, 100]. However, their accurate characterisation remains challenging due to their low proliferation rates. In acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), leukemia stem cells (LSCs) are central to disease relapse and treatment resistance. Yet, their low abundance in bone marrow samples complicates isolation from healthy hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Velten et al. [101] integrated single-cell transcriptomics with nuclear and mitochondrial somatic mutation profiling, successfully distinguishing HSCs, pre-leukemia stem cells (pre-LSCs), LSCs, and progenitor/primary cell populations. By simultaneously analyzing mutational status and gene expression at the single-cell level, the study identified differentiation defects caused by leukemia mutations and characterise the transcriptomes of leukemia and pre-leukemia stem cells, underscoring the potential of single-cell multi-omics in advancing cancer stem cell research.

Furthermore, the integration of emerging computational technologies has revolutionised the application of scRNA-seq. This approach has significantly enhanced the ability to analyse previously complex and resource-intensive studies, improving efficiency and reducing costs [102, 103, 104]. Galen et al. [74] combined scRNA-seq with genotyping and applied machine learning classifiers to discriminate between malignant and normal cells, identifying six distinct malignant AML cell types. The study elucidated abnormal regulatory programmes in primitive AML cells and revealed a significant correlation between developmental stages and tumor genetics. Notably, it also identified differentiated AML cells with immunosuppressive properties, providing novel insights into AML cell heterogeneity and differentiation states.

Cellular heterogeneity is a fundamental characteristic of both tumor and normal tissues, posing challenges to the elucidation of specific cellular functions and disease features [105, 106]. Single-cell RNA sequencing has uncovered cellular heterogeneity in various solid tumors and plays a pivotal role in hematopoietic system research [107, 108]. Crinier et al. [109] applied scRNA-seq to analyze subsets of NK cells in human bone marrow, revealing significant heterogeneity of NK cells under physiological conditions and at the time of AML diagnosis. This study mapped the transcriptome of bone marrow NK cells for the first time, explored the heterogeneity of NK cell lineages, and identified high sample specificity. However, the inability to clearly define specific NK cell subpopulations highlights future research directions in AML.

Similarly, Mumme et al. [110] utilized scRNA-seq to explore cellular diversity in mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL), identifying distinct transcriptomic profiles between B- and T-lineage cells. They observed transcriptional differences between B-MPAL and T-MPAL, as well as overlapping profiles with B/T-ALL and AML. These insights into cellular heterogeneity are crucial for predicting therapeutic responses, prompting clinicians to consider this variability when formulating treatment strategies.

In clinical trials for acute leukaemia, scRNA-seq has become a powerful tool, with applications extending to clinical efficacy validation, disease relapse monitoring, risk stratification, prognostic marker identification, and treatment safety evaluation. In the context of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) immunotherapy, Zhang et al. [111] and Chen et al. [112] employed scRNA-seq to investigate the safety of CAR-T therapy targeting AML-associated antigens and the dynamics of immune homeostasis at the cellular level. These studies precisely identified potential risks of “on-target, off-tumor toxicity”, providing critical insights for optimizing treatment strategies.

Furthermore, Christopher et al. [113] conducted scRNA-seq on bone marrow samples from AML patients at initial diagnosis and post-transplantation relapse. Their findings revealed that AML relapse may be associated with the development of cells deficient in major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II) gene expression, uncovering a novel immune escape mechanism. This discovery lays a theoretical foundation for developing targeted anti-relapse strategies. Additionally, Xiong et al. [114] analyzed bone marrow and peripheral blood cells from AML patients with t(8;21) chromosomal abnormalities at diagnosis and relapse, identifying thirteen differentially expressed genes associated with cancer progression and prognosis. These genes hold promise as biomarkers for predicting post-transplant relapse, enabling more precise risk assessment and personalized treatment in clinical practice.

In conclusion, Single-cell RNA sequencing has emerged as a transformative force in acute leukemia research and clinical practice. Mechanistically, it enables precise characterization of MRD cells, unveiling their stem-like properties and epigenetic plasticity while elucidating the link between MRD and immune deficiencies. This technology also dissects the intricate mechanisms of immune evasion, including bone marrow microenvironment remodeling and T-cell dysregulation, clarifying the dual roles of T-cell subsets in disease progression and the impact of cellular heterogeneity on treatment responses.

Technologically, integrating single-cell multi-omics with computational approaches facilitates the identification of cancer stem cells and the exploration of abnormal tumor cell regulatory programs. Clinically, single-cell RNA sequencing plays a pivotal role in evaluating the safety of CAR-T therapies, monitoring disease relapse, and discovering prognostic biomarkers. These applications underpin risk stratification and personalized treatment strategies, heralding a new era of precision medicine in acute leukemia management.

Single-cell RNA sequencing has enabled in-depth investigations into the pathogenesis of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Liu et al. [75] performed single-cell RNA sequencing on lineage-negative cells isolated from bone marrow samples of MDS patients and those with secondary acute myeloid leukemia (sAML), comparing the data with single-cell RNA sequencing profiles of bone marrow mononuclear cells from healthy donors in the Gene Expression Omnibus database. This supported the notion that MDS stem cells reside in a relatively quiescent state with impaired immune function, and suggests that abnormal ribosome biogenesis is involved in the mechanism of MDS relapse and transformation to leukaemia based on the downregulation of ribosome gene expression. Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling has been implicated in the pathogenesis of certain hematopoietic malignancies [115], and increased expression of TLR1 and its exclusive coreceptor has been observed in CD2+ cells of MDS patients [116]. To further explore TLR expression in myeloid cell populations, Li et al. [117] conducted scRNA-seq on sorted DCs, monocytes, and macrophages. Their findings revealed that TLR1 and TLR2 stimulation in DCs promotes local secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1

Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) serves as a crucial regulator of cellular differentiation and development, influencing multiple stages of gene regulation and modulating cancer-related energy metabolism [118, 119]. However, the low expression levels of lncRNAs in bulk cell populations limit the sensitivity of traditional RNA sequencing, rendering it difficult to detect lncRNA expression in smaller or more heterogeneous cell groups [120]. Wu et al. [121] applied scRNA-seq to analyze lncRNA expression in aneuploid monocytic cells from patients with MDS. Their findings showed that single-cell analysis enables more effective detection of lncRNA expression compared to bulk population analysis. This approach allowed for a detailed characterization of lncRNA expression patterns in CD34+ cells, revealing stage- and lineage-specific expression profiles. The data further implicated lncRNAs in the regulation of human haematopoiesis and related cellular functions, providing a comprehensive understanding of lncRNA activity during early human haematopoiesis.

The MDS are age-associated myeloid tumours with a one-third likelihood of progression to AML, but the mechanism of disease progression is unclear and may be related to the senescent microenvironment [122, 123]. Mei et al. [76] demonstrated that depletion of IL-6 significantly delayed disease progression in a double-knockout (DKO) mouse model of MDS. Using 10X Genomics® to analyze cells from high-risk MDS patients and aged DKO mice, the study confirmed that IL-6 signaling mediates the transformation of MDS to AML. Notably, the number of primitive monocytes decreased following IL-6 knockout, highlighting the potential of IL-6 as an early diagnostic marker and therapeutic target for MDS progression.

Decitabine is an effective drug for treating high-risk MDS and AML, but its clinically relevant effects in vivo are difficult to reproduce accurately in vitro. To systematically identify the overall genomic and transcriptomic changes induced by decitabine in vivo, Upadhyay et al. [124] evaluated bone marrow samples from patients with MDS and AML during treatment and performed a multi-omics analysis combining whole-genome bisulfite sequencing, bulk RNA sequencing, and scRNA-seq. They found that the repressive state of red lineage-associated transcripts was reversed in the relapsed samples after decitabine treatment, defining the global hypomethylation of decitabine, suggesting that the erythroid-related pathway was associated with MDS progression and proposing a new idea for the mechanism of resistance to decitabine and other demethylating drugs in MDS and AML patients. Recently, Serrano et al. [125] uses single-cell RNA sequencing to uncover aberrant transcriptional signatures in CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells from del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes and the molecular regulatory effects of lenalidomide.

Single-cell RNA sequencing has emerged as a transformative tool in deciphering the mechanisms of MDS. In understanding pathogenesis, studies have confirmed that MDS stem cells exhibit a quiescent state with impaired immunity, while abnormal ribosome biogenesis drives disease progression; activation of TLR1/2 signaling in dendritic cells also contributes to pathology by regulating inflammatory cytokine secretion. Regarding molecular profiling, single-cell sequencing overcomes technical limitations to precisely characterize the stage- and lineage-specific expression patterns of LncRNAs in CD34+ cells, elucidating their regulatory roles in hematopoiesis. For disease progression and drug resistance, research has identified IL-6 signaling as a key mediator of MDS transformation into AML, offering potential for early diagnosis and targeted therapy. Multi-omics analyses further revealed erythroid-related pathways associated with disease progression and provided novel insights into the resistance mechanisms of drugs like decitabine. Collectively, these findings highlight how single-cell RNA sequencing, by dissecting cellular heterogeneity and molecular networks at high resolution, is propelling MDS research towards more precise and mechanistic understanding.

Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, particularly mycosis fungoides (MF), generally has a favorable prognosis, yet 20–30% of patients experience disease progression. To elucidate the mechanisms underlying aggressive disease development, Rindler et al. [77] employed scRNA-seq to compare indolent samples with a long disease history, newly emerged aggressive samples, early-stage MF samples, and healthy skin controls. The study identified a series of significant markers, whose expression was downregulated in different subtypes of malignant MF but upregulated in healthy samples and MF cases without clinical symptoms [77]. These findings led to the proposal of markers for predicting MF progression, which can be utilized for disease progression monitoring and the development of personalized therapies. To better distinguish between benign and malignant T cells in MF, Gaydosik et al. [126] utilized single-cell RNA sequencing to assess the transcriptional profiles of malignant T cell clones and reactive T lymphocytes. Comprehensive data analysis revealed the upregulation of metabolic, cyclic regulation, oxidative stress, and other related pathways, providing new insights into the mechanisms of the pathogenesis and progression of MF.

In the later stages of MF disease, lesions are no longer confined to the skin and may appear in the blood, lymph nodes, or bone marrow. Previous studies have confirmed that changes in the TME may be associated with this disease progression [127]. To further elucidate the characteristics of the MF tumor microenvironment and the interactions within it, Rindler et al. [78] combined scRNA-seq with single-cell variable–diversity–joining sequencing to analyze skin, peripheral blood, and lymph node samples from MF patients. The study evaluated the characteristics of malignant clones in MF cells and their dynamic interactions with the microenvironments of different compartments, enabling reliable tracking of individual T-cell populations in the human body. Findings suggested that the dispersal behavior of tumor cells may reflect the physiological migratory behavior of tissue-resident memory T cells. However, due to the heterogeneity of malignant clones and limited sample size, these results require validation in more patients and MF subtypes.

Subsequent studies have deepened our understanding. Du et al. [128] used single-cell RNA sequencing to redefine the developmental trajectories of T/NK cells and myeloid cells within the CTCL tumor microenvironment, characterizing malignant T-cell subsets and the intercellular communication between malignant and microenvironmental cells. Aoki et al. [129] conducted similar research, analyzing the phenotype of the Hodgkin’s lymphoma-specific immune microenvironment at single-cell resolution for the first time. This approach enabled the identification of new Hodgkin’s lymphoma-associated T-cell subpopulations with distinctive expression profiles. This provided new insights into the biology of the TME. Ye et al. [130] analyzed over 2000 potential cellular interactions using single-cell RNA sequencing, revealing the complex and highly dynamic nature of the tumor microenvironment in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The study suggested that specific cellular interactions can further promote tumor cell proliferation and survival. Li et al. [131] uses single-cell RNA sequencing to discover that malignant cells in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma reshape the cellular landscape and create an immunosuppressive microenvironment, driving disease progression.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a specific type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma with high heterogeneity and a high relapse rate [132]. To explore the characteristics of different cellular subpopulations within MCL, Wang et al. [133] performed scRNA-seq on bone marrow cells from multidrug-resistant MCL patients. The study identified several specific subpopulations and a series of cellular markers associated with immune escape and drug resistance. Validation through dataset integration elucidated the critical roles of these genes in immune evasion and drug resistance mechanisms. Holmes et al. [134] employed CITE-seq to analyze germinal center (GC) B cells, identifying multiple functionally relevant lymphoma cell subpopulations. They explored the developmental dynamics of GCB cells beyond the known dark zone and light zone compartments, modeled the multi-step differentiation process, and constructed a developmental stage atlas for GCB cells. With advancements in single-cell transcriptomic technology, numerous previously undefined subgroups have been reclassified at the single-cell level, leading to the discovery of novel prognostic subgroups in DLBCL.

The current understanding of the biology of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma has focused on the characteristics of the malignant clones [135], leaving limited understanding of the non-malignant populations within its TME. To gain deeper insights into the non-malignant components of the TME, Pritchett et al. [136] combining mass spectrometry cytometry and scRNA-seq to characterise the expanding population in the TME, and found that B cells in the TME were characterised by reduced expression of key markers, including CD73 and CXCR5, described the expansion of different CD8+ T-cell populations, and these cell populations were found to have depleted phenotypes and potential expression profiles with upregulation of XCL2 and XCL1, which can induce dysfunctional, impaired cytotoxicity.

Investigations of the cellular heterogeneity of lymphoma tumour cells have also used scRNA-seq. Gaydosik et al. [137] utilized 10X Genomics® to reveal significant inter- and intra-tumoral gene expression heterogeneity among T lymphocyte subsets in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. They also determined the immune status of the reactive lymphocytes. The results demonstrated that patient samples with effector and depletion programmes exhibited significant heterogeneity, offering invaluable insights into lymphocyte diversity. Borcherding et al. [138] further analyzed cutaneous T-cell lymphoma samples using scRNA-seq, uncovering transcriptome diversity within clonal tumors. This transcriptional heterogeneity enabled 80% accurate prediction of tumor stages, offering precise guidance for clinical treatment. Similarly, Ye et al. [130] employed single-cell RNA sequencing to analyze the transcriptomes of DLBCL samples and control cells, generating comprehensive single-cell transcriptome profiles of DLBCL. The study identified a distinct set of highly expressed genes in different samples. Analysis indicated that individual cells within the samples expressed diverse genetic programmes at varying levels, confirming a high degree of inter- and intra-tumoral heterogeneity in malignant B cells. These findings suggest that intra-tumoral heterogeneity may be a potential mechanism contributing to disease recurrence.

When traditional research methods are difficult to perform, scRNA-seq can be used as an adjunctive technique. Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is a rare type of central nervous system lymphoma. However, the limited accessibility of central nervous system biopsy samples has hampered in-depth investigations of PCNSL. To overcome these challenges and gain comprehensive insights into PCNSL, Heming et al. [139] integrated CITE-seq with spatial transcriptomics of biopsy samples, conducting multi-omics analyses on PCNSL cells derived from biopsy tissues, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid. The study successfully identified multiple cellular subclusters, uncovering the heterogeneous phenotype of malignant B cells in PCNSL. Combined with spatial transcriptomics, it revealed that these malignant B cells exhibit both transcriptional and spatial intra-tumoral heterogeneity. Notably, researchers found that, similar to DLBCL, the intra-tumoral heterogeneity of PCNSL may be associated with drug-resistant relapse. This discovery raises a critical question: Does this potential association exist across all lymphoma subtypes? Answering this question could open new avenues for exploring therapeutic targets in lymphoma research.

With its high-resolution analytical power, single-cell RNA sequencing has systematically advanced lymphoma research across multiple dimensions, including pathogenesis, tumor microenvironment, cellular subpopulations, heterogeneity, and supplementary explorations. In understanding disease mechanisms, studies comparing indolent and aggressive samples have identified markers predicting the progression of MF and revealed the critical roles of metabolic and stress-related pathways. Research on the tumor microenvironment, integrated with multi-omics techniques, has elucidated dynamic interactions between tumor cells and the microenvironment, uncovering the migratory characteristics of specific cell subsets and immune regulatory mechanisms. For cellular subpopulation analysis, single-cell sequencing has successfully identified drug-resistant subpopulations in MCL and characterized non-malignant cells in AITL, providing targets for precision medicine. Additionally, the technology has uncovered intra-tumoral heterogeneity in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and DLBCL, suggesting its association with disease recurrence. In the study of rare PCNSL, single-cell sequencing combined with spatial transcriptomics overcomes sample limitations, revealing the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of malignant B cells and drug resistance mechanisms, thus guiding the search for universal therapeutic targets. Collectively, these findings establish single-cell RNA sequencing as a core tool for deciphering the complex biology of lymphoma, providing critical support for translational research.

Although the precursor stage of multiple myeloma (MM) is relatively easy to detect, no guidelines currently indicate the need for initiating treatment at this stage. However, the precursor state of MM carries a potential risk of progressing to overt MM [140]. To explore molecular characterization for accurate identification and intervention in high-risk preclinical MM, Zavidij et al. [79] used single-cell RNA sequencing to analyze early immune changes during disease progression from precursor stages, including monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smouldering MM, to mature MM, as well as in healthy donors. The researchers observed substantial microenvironmental alterations starting from the MGUS stage, with increased numbers of NK-cells, T-cells, and non-classical monocytes compared to healthy samples. These results provide a comprehensive overview of immune changes involved in preclinical MM progression, offering insights to inform the development of patient stratification strategies based on immune factors. Additionally, Matera et al. [141] proposed potential markers for the early and specific diagnosis of MM through scRNA-seq.

Because MM is a heterogeneous disease with a complex clonal evolution and TME [142], researchers face significant challenges in understanding the polyclonal nature of MM using appropriate techniques. Liang et al. [143] integrated scRNA-seq and single-molecule long-read genome sequencing to analyze bone marrow aspirates from MM patients and healthy controls. The study aimed to explore the clonal evolution of MM, successfully identifying a series of mutation events associated with cellular clonal evolution and constructing a pseudo-temporal clonal evolutionary map of MM malignant cells. Further analysis revealed that the clonal evolution process not only responds to microenvironmental selection but also adapts to environmental changes, reshaping the microenvironment for survival. These adaptations exhibit substantial patient-specificity, likely linked to tumor heterogeneity.

He et al. [80] performed concurrent scRNA-seq and variable diversity junction region-targeted sequencing (scVDJ-seq) on bone marrow samples from newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory MM patients to identify malignant cells and their clonal phenotypes. The study classified malignant plasma cells into eight subclusters, confirming the presence of clonal diversity as most samples harbored multiple clonal phenotypes. It also demonstrated that myeloma cells in diagnostic or recurrent samples were predominantly dominated by a single major clone, consistent with the clonal expansion nature of MM, and detected subclones in certain samples. Differential expression analysis of these subclones identified a series of statistically significant genes, offering new insights into the mechanisms of MM clonal evolution. Cui et al. [144] collected bone marrow samples from MM patients before and after induction therapy for scRNA-seq, exploring the transcriptional dynamics of plasma cells from diagnosis to post-treatment. It revealed that MM cells underwent clonal evolution as early as the post-induction therapy stage, and summarized three patterns of clonal evolution [144].

Resistance mechanisms in relapsed refractory MM can also be studied using scRNA-seq. Cohen et al. [145] conducted a prospective, multicentre, single-arm clinical trial, integrating MARS-seq to explore the molecular dynamics underlying MM drug resistance. The study identified novel molecular resistance pathways in MM, including hypoxia tolerance, protein folding, and mitochondrial respiration. It also characterised highly drug-resistant MM patients and proposed peptidylprolyl isomerase A as a potential therapeutic target. To gain a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving MM resistance, Tirier et al. [146] cperformed scRNA-seq on pre- and post-treatment samples. This approach enabled the identification of tumor cell heterogeneity in drug-resistant MM patients and their differential responses to treatment. Additionally, the study investigated subclonal transcriptional profiles and high-risk chromosomes associated with MM resistance. These findings have significant implications for clinical decision-making in MM management.

As myeloma progresses, dynamic changes occur in the bone marrow microenvironment, with interactions between myeloma cells and their surroundings carrying critical pathophysiological significance [147, 148]. de Jong et al. [149] used 10X Genomics® to analyze the hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic bone marrow microenvironment in MM. They identified spatial co-localization of inflammatory mesenchymal stromal cells with tumor and immune cells, revealing that these stromal cells transcribe genes involved in tumor survival and immune regulation. This highlights an inflammatory stromal cell landscape as a defining feature of the MM tumor microenvironment. Notably, inflammatory changes in the microenvironment persisted after antitumor therapy ceased, providing a direction for further research. Tirier et al. [146] further demonstrated through scRNA-seq that MM drug resistance correlates with alterations in bone marrow microenvironment composition, particularly increased expression of certain inflammatory cytokines. Lv et al. [150] integrated scRNA-seq to map the cellular components of the MM bone marrow microenvironment and characterize immune cell dynamics. They found that the bone marrow immune microenvironment exhibits biological consistency with tumor cell infiltration. Further analysis revealed that aberrant metabolic processes induce immune cell dysfunction in the MM tumor microenvironment, suggesting that correcting metabolic disorders may offer a novel perspective for MM immunotherapy.

Single-cell RNA sequencing has systematically uncovered key biological mechanisms of MM from precursor to advanced stages through high-resolution profiling. For early recognition, studies revealed that immune cell alterations in the bone marrow microenvironment occur as early as the MGUS stage, providing evidence for immune-based risk stratification and identifying early diagnostic markers. In clonal evolution research, single-cell sequencing combined with genomics constructed evolutionary maps of malignant cells, confirming that subclonal diversity under major clone dominance drives MM heterogeneity, with dynamic interactions between clonal evolution and microenvironmental selection. For drug resistance, novel pathways such as hypoxia tolerance and mitochondrial respiration were identified, with Peptidylprolyl cis - trans Isomerase A (PPIA) proposed as a therapeutic target. Resistance was also linked to increased inflammatory cytokines in the bone marrow microenvironment and subclonal transcriptional heterogeneity. Regarding microenvironment mechanisms, single-cell analysis highlighted spatial co-localization of inflammatory mesenchymal stromal cells with tumor/immune cells as a defining feature of the MM microenvironment, while aberrant metabolic processes were shown to induce immune cell dysfunction, sustaining tumor immune evasion. Collectively, these findings establish single-cell RNA sequencing as a pivotal tool for providing full-spectrum evidence from mechanistic insights to clinical translation in MM.

The use of scRNA-seq methods has played an important role in the study of haematopoietic malignancies and changed our fundamental understanding of the blood system [151]. Since its inception, scRNA-seq has revolutionized our understanding of cellular heterogeneity and biological processes. It has helped researchers overcome key challenges, including identifying rare cell types within heterogeneous populations, comparing malignant and non-malignant cells at different differentiation stages, mapping the transcriptome, and tracking the dynamic changes in various cell differentiation processes within the hematopoietic system [152, 153, 154]. In hematopoietic research, scRNA-seq has become a crucial tool for deciphering the complexity of hematopoiesis. Widely applied in acute leukemia studies, scRNA-seq has also shown great potential in MDS research, despite its current limited use. With the emergence of advanced technologies across different fields, scRNA-seq is no longer an isolated research method. Integrated with other single-cell sequencing techniques, it has evolved into a powerful tool within the single-cell multi-omics strategy. This integration reveals the biological characteristics of tumor cells from multiple perspectives, offering new approaches to tumor research [155].

When addressing sample processing for scRNA-seq, the following principles should be observed: Clinical specimens must balance cellular fidelity and practicality, with fresh samples preferably undergoing rapid dissociation and immediate sequencing, whereas cryopreserved samples require optimized freezing/thawing protocols to mitigate cellular damage. Cell enrichment strategies should be tailored to target cell populations, integrating physical separation, marker-based sorting, and functional profiling to enhance single-cell suspension purity. Robust sample processing is foundational for scRNA-seq to resolve clinical heterogeneity, necessitating standardized operating procedures and rigorous quality control to ensure data reliability.

The continuous advancement of scRNA-seq has enabled the use of peripheral blood for single-cell RNA sequencing in disease diagnosis [156, 157]. This breakthrough opens new avenues for studying hematopoietic malignancies where sample collection is challenging. Peripheral blood scRNA-seq analysis holds promise for accurately diagnosing specific lymphomas, reducing missed diagnoses, and supporting personalized treatment based on sequencing results [156, 158, 159].

However, scRNA-seq still faces several challenges. At the experimental level, issues such as cDNA synthesis efficiency (affecting detection sensitivity), amplification bias (compromising quantitative accuracy), high costs (limiting its application), and lack of automated data processing require urgent solutions [19, 160, 161]. High dependence on amplification, low RNA input in sequencing experiments, and random gene expression patterns at the single-cell level often lead to dropout events and discrepancies between technical and biological replicates [162]. In sample processing, dissociating frozen samples usually results in poor-quality single-cell suspensions, posing challenges for sample preservation. Although successful cryopreservation of solution-treated frozen samples has been reported in glomerular single-cell RNA sequencing [163], further experimental validation is needed to confirm its applicability to the hematopoietic system. Nevertheless, scRNA-seq technology and data analysis capabilities continue to improve. Over the past decade, the cost of scRNA-seq has decreased, and with the advent of commercial platforms, high-throughput, low-cost transcriptome analysis of thousands of cells has become possible.

Several key areas of future development and challenges for scRNA-seq merit attention:

(1) Integrating spatial transcriptomics with scRNA-seq can capture both gene expression and spatial location information, essential for understanding cell interactions and tissue functions [164]. Technologies like Slide-seq [165] and Visium [164] can generate spatial transcriptomic data, but fusing this data with scRNA-seq data efficiently remains a challenge. In 2024, Zhang et al. [166] developed the scRICA-seq technology, enabling simultaneous detection of chromatin accessibility, RNA expression, and isoform structures at the single-cell level for multi-omics integration. The same year, Li et al. [167] proposed the scBridge method, accurately integrating scRNA-seq and single-cell chromatin accessibility sequencing (scATAC-seq) data. Multi-omics integration, while offering comprehensive insights into cellular states and regulatory mechanisms, faces challenges due to diverse data types and complex analysis pipelines. Developing advanced computational algorithms and experimental techniques is essential for seamless multi-omics data integration.

(2) Improving the sensitivity and throughput of scRNA-seq is crucial. Higher sensitivity aids in detecting low-abundance transcripts and rare cell populations, while increased throughput enables rapid analysis of large samples. Despite current advancements, such as microfluidic technology and novel library preparation methods, the growing research demands remain unmet. For instance, existing techniques may not fully capture the transcriptome of extremely small clinical samples [168]. In 2023, a team from Zhejiang University developed the snHH-seq method, enhancing sensitivity, coverage, and cell throughput [168]. In 2024, Li et al. [169] reported the UDA-seq technology, increasing the throughput to 100,000 cells per channel, and the FIPRESCI technology further boosted cell throughput by over tenfold while reducing costs [170].

(3) Development of more robust and standardized scRNA-seq data analysis pipelines. Standardizing scRNA-seq data analysis is imperative. Currently, inconsistent preprocessing, clustering, and differential expression analysis methods across laboratories hinder result comparability and reproducibility. Expanding data scales also challenge computational efficiency and accuracy. In 2024, a team from Chongqing Normal University evaluated single-cell/spatial transcriptomics data simulation algorithms, and researchers from Nanjing Agricultural University developed the scFseCluster framework to address common algorithm limitations [171, 172]. Collaborative efforts between academia and industry, along with leveraging artificial intelligence, are needed to establish unified standards and develop automated analysis tools.

(4) Translating scRNA-seq from laboratory research to clinical applications encounters significant barriers. Clinical samples’ complexity requires more stable and reliable scRNA-seq technologies. The lack of unified clinical testing standards and quality control systems undermines result accuracy and consistency. High costs and long detection cycles also impede clinical translation. Extensive clinical studies are necessary to validate scRNA-seq’s clinical utility and establish standardized application protocols.

(5) With the widespread use of scRNA-seq, data privacy and ethical concerns become prominent. The large-scale generation of single-cell data contains sensitive biological information, and data breaches could harm individuals. Technologies like Live-seq, which allows cells to remain viable after sequencing, introduce new privacy protection challenges [173]. Ensuring ethical data use and protecting participant rights during data sharing require robust regulations and secure data handling technologies.

ScRNA-seq presents both opportunities and challenges.To address disease-specific challenges, the integration of emerging technologies holds promise. For instance, spatial transcriptomics can resolve the spatial-temporal dynamics of tumor cells and their microenvironment, addressing the limitation of scRNA-seq in lacking spatial context. Additionally, CRISPR-based scRNA-seq enables high-throughput functional screening at single-cell resolution, facilitating the identification of driver genes in clonal evolution and drug resistance. However, realizing the full potential of scRNA-seq requires coordinated efforts across multiple domains: technological innovation to improve sequencing depth and reduce bias in long transcript or rare cell detection; standardization of data analysis pipelines to ensure reproducibility across studies; clinical integration to develop scRNA-seq-guided diagnostic and therapeutic strategies; combining scRNA-seq with liquid biopsy enables dynamic monitoring of clonal evolution and treatment response and ethical regulation to address challenges in data privacy and clinical utility evaluation.

By synergizing technological advancement with systematic governance, scRNA-seq and its integrated approaches will not only overcome disease-specific hurdles in hematology but also drive transformative breakthroughs in precision medicine for life sciences and clinical practice.

AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell immunotherapy; CEL-seq, cell expression by linear amplification and sequencing; CITE-Seq, cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing; Cyto-seq, gene expression cytometry; DCs, dendritic cells; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; DP-seq, designed primer-based RNA-sequencing; Drop-seq, single-cell high-throughput droplet sequencing; ETP-ALL, early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; GC, germinal centre; HSC, haematopoietic stem cell; IVT, in vitro linear transcription; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; LSC, leukaemia stem cell; MARS-seq, massively parallel single-cell RNA sequencing; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MF, mycosis fungoides; MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; MM, multiple myeloma; MPAL, mixed phenotype acute leukaemia; MRD, minimal residual disease; NK, natural killer; PCNSL, primary central nervous system lymphoma; scRNA-seq, single-cell RNA sequencing; Smart-seq2, switching mechanism at 5′-end of the RNA transcript; STRT-Seq, single-cell labelled reverse transcription sequencing; TLR, toll-like receptor; TME, tumour microenvironment; WTA, whole-transcript amplification.

YG and XW participated in the main writing and initial review of the manuscript. FL and YZ polished and revised the manuscript, and together with YG prepared the figures and tables. XH and SW collected the relevant literature, developed the initial concept of the article together with XW, and checked the figures and tables. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Figs. 1,3 were created by Figdraw (https://www.figdraw.com/static/index.html), Figs. 2,4 were created with BioRender (https://www.biorender.com/); We thank InternationalScience Editing (https://www.internationalscienceediting.com/) for editing this manuscript.

This research was funded by the financial supported by Project supported by the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81900153), the General Program of Basic Scientific Research Project of Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (No. LJKMZ20221177), the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (No. 2022-YGJC-62).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.