1 Division of Hematology-Oncology, Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA

Abstract

Cancer continues to be a significant global health issue, influenced by genetic mutations and external factors like carcinogenic exposure, lifestyle choices, and chronic inflammation. The myelocytomatosis (MYC) oncogene family, including c-MYC, MYCN, and MYCL, is essential in the development, progression, and metastasis of various cancers such as breast, colorectal, osteosarcoma, and neuroblastoma. Beyond its well-known roles in cell growth and metabolism, MYC significantly shapes the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) by altering immune cell dynamics, antigen presentation, and checkpoint expression. It contributes to immune evasion by upregulating checkpoints such as programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and cluster of differentiation (CD)47, suppressing antigen-presenting major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, and promoting the recruitment of suppressive immune cells such as regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). While direct targeting of MYC has proven challenging, recent advances in therapeutic strategies, including MYC-MYC-associated factor X (MAX) dimerization inhibitors, bromodomain and extra terminal domain (BET) and cyclin dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors, synthetic lethality approaches, and epigenetic modulators, have shown promising results in preclinical and early clinical settings. This review discusses MYC’s comprehensive impact on TIME and examines the promising therapeutic strategies of MYC inhibition in enhancing the effectiveness of immunotherapies, supported by recent preclinical and clinical findings.

Keywords

- MYC

- tumor immune microenvironment

- immunotherapy

- cancer

- oncogene

In 2022, approximately 20 million new cancer cases and 9.7 million cancer-related deaths were reported globally, with projections indicating a sharp rise to 35 million new cases by 2050 [1]. In the United States alone, the American Cancer Society estimates around 2 million new cancer cases and 600,000 cancer deaths in 2024 [2]. This alarming burden underscores the urgent need for innovative therapeutic strategies to improve patient outcomes and reduce mortality rates. Cancer progression is a multifactorial process involving a complex interplay of genetic mutations and environmental influences. Among these, intrinsic alterations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes are pivotal, as they deregulate fundamental cellular processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, and immune surveillance, thereby driving malignant transformation and disease progression [3, 4]. One of the most critical oncogene families implicated in cancer is the myelocytomatosis (MYC) family, which comprises three closely related members: c-MYC, MYCN, and MYCL [5, 6]. These oncogenes stand out due to their frequent dysregulation and their broad influence on cancer biology across a wide range of malignancies, including neuroblastoma, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, osteosarcoma and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) [7, 8, 9]. MYC proteins are transcription factors that govern vital cellular processes, including metabolism, protein synthesis, and genomic integrity. Their overexpression or amplification is often associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes, poor prognosis, and resistance to conventional therapies [10, 11].

MYC proto-oncogenes are central regulators of fundamental cellular processes, including cell growth, proliferation, metabolism, and differentiation [12, 13, 14]. Dysregulated MYC signaling is a hallmark of many human cancers, driving malignant transformation and tumor progression. Beyond driving intrinsic tumor growth, MYC profoundly influences the tumor microenvironment (TME), particularly the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) [15, 16, 17, 18]. The TME is a dynamic and complex milieu consisting of tumor cells, immune cells (e.g., macrophages, dendritic cells, T cells, B cells, etc.), smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and cancer-associated stromal cells, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. These components collectively shape tumor progression, immune evasion, and therapeutic response [21]. Within this context, MYC-driven tumors exploit the TIME by upregulating immune checkpoint proteins such as programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and cluster of differentiation (CD)47, which suppress antitumor immune responses [17]. In addition, MYC promotes the recruitment of immunosuppressive cells, including regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), while simultaneously downregulating antigen presentation pathways, further facilitating immune evasion [17]. These MYC-induced alterations create an immunosuppressive environment that promotes tumor survival and growth while also limiting the efficacy of immunotherapeutic interventions [24, 25, 26].

While immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapies targeting the programmed death (PD)-1/PD-L1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein (CTLA)-4 pathways have transformed the landscape of cancer treatment, their effectiveness in MYC-overexpressing tumors remains suboptimal due to the immunosuppressive nature of the TIME [27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37]. MYC is a highly attractive therapeutic target in cancer due to its central role in regulating key pathways and several preclinical tumor models have demonstrated that turning off MYC expression leads to tumor regression, providing proof of concept that pharmacological targeting of MYC could effectively inhibit tumor growth [38, 39, 40, 41, 42]. However, direct targeting of MYC with small-molecule inhibitors poses significant challenges. MYC is intrinsically disordered, lacking a well-defined hydrophobic pocket or groove suitable for high-affinity binding by low molecular weight compounds [11, 43]. Unlike other oncogenic drivers, MYC lacks enzymatic activity, making it unsuitable for inhibition by conventional enzyme-targeting drugs. Preclinical studies have shown that MYC inhibition can reprogram the TIME, enhance immune cell infiltration, and restore sensitivity to ICB therapies. Combining MYC inhibition with ICB therapies has emerged as a promising strategy to synergistically boost antitumor immune responses and improve clinical outcomes [38, 44, 45].

This review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of MYC’s role in regulating the TIME, with a focus on its mechanisms of immune evasion, therapeutic resistance, and tumor progression. Additionally, we explore emerging therapeutic strategies targeting MYC, including bromodomain and extra terminal domain (BET) inhibitors, cyclin dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors, synthetic lethality approaches, and epigenetic modulators. By highlighting recent advancements and ongoing challenges, we aim to propose future research directions in this rapidly evolving field of cancer therapy.

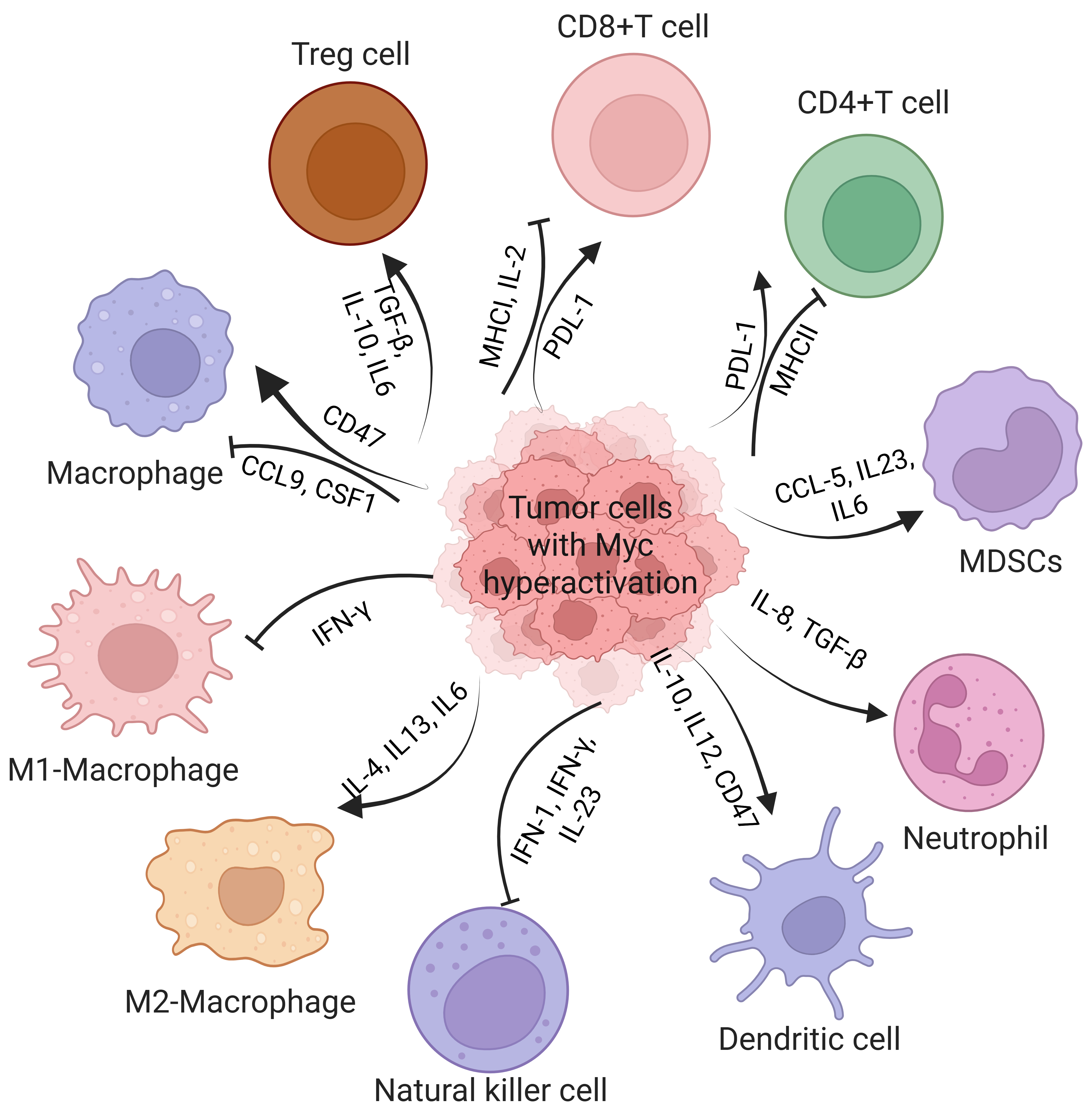

MYC plays a central role in immune evasion by regulating key immune checkpoints, suppressing antigen presentation, and fostering an immunosuppressive TME. In MYC-driven tumors, upregulation of immune checkpoints like PD-L1 and CD47 impairs T cell function and promotes immune tolerance [46]. Fig. 1 illustrates how MYC-driven tumors regulate immune cells in the TME, collectively creating a TIME that resists immune surveillance and therapy.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of how MYC hyperactivation in tumor cells creates an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by altering immune cell function through cytokine signaling and immune checkpoint regulation. MYC-driven tumors upregulate PD-L1 and downregulate MHC-I/II in CD8⁺ and CD4⁺ T cells, leading to T cell dysfunction. They also promote the recruitment of Tregs, MDSCs, and M2 macrophages via cytokines such as IL-10, TGF-

MYC plays a critical role in immune evasion by directly modulating the expression of key immune checkpoint molecules, encompassing both adaptive and innate immune regulators, thereby fostering an immunosuppressive TME. Among the adaptive immune checkpoints, PD-L1 is one of the most critical targets of MYC. By directly binding to the promoter region of PD-L1, MYC drives its transcriptional activation, leading to T cell exhaustion and reduced cytokine production. This mechanism has been observed in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [47, 48, 49]. In oxaliplatin-resistant HCC, MYC enhances PD-L1 expression and recruits polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (PMN-MDSCs) through C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)5 secretion, further amplifying immune suppression and therapeutic resistance. Notably, MYC depletion in preclinical models reduces PD-L1 expression, restores CD8⁺ T cell activity, and sensitizes tumors to chemotherapy [50, 51]. In addition to PD-L1, MYC regulates innate immune checkpoints, particularly CD47, which acts as a “do not eat me” signal by binding to signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRP

Given the central role of MYC in regulating immune checkpoints, combining immune checkpoint blockade with MYC-targeted therapies has emerged as a promising approach. For example, in Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS)-mutated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), silvestrol, a eukaryotic initiation factor 4A (eIF4A) inhibitor that blocks MYC translation, synergized with anti-PD-1 therapy to suppress tumor growth by reducing MYC-driven PD-L1 expression and macrophage recruitment [54]. Additionally, an eIF4A inhibitor enhances the efficacy of KRAS G12C inhibitors in NSCLC by suppressing B-cell lymphoma (BCL)-2 family proteins, with MYC overexpression increasing sensitivity to this combination, highlighting a promising therapeutic strategy for KRAS-mutant NSCLC [55]. Targeting the inhibitor of DNA-binding 1 (ID1)/MYC axis in HCC similarly reduced PD-L1 expression and MDSCs infiltration, enhancing immune responses and improving sensitivity to chemotherapy and checkpoint inhibitors [49]. These findings highlight the potential of combining MYC inhibition with immune checkpoint blockade to enhance therapeutic outcomes across diverse cancer types. The combination of MYC inhibition and immune checkpoint blockade, specifically anti-PD-L1, significantly enhances tumor regression and extends survival in MYC-driven triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [56].

MYC-mediated suppression of antigen presentation is a key mechanism by which tumors evade immune surveillance [57]. MYC represses the expression of critical components of the antigen presentation machinery (APM), such as MHC class I molecules and transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) transporters, through transcriptional regulation and post-translational modifications like small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)ylation [56, 58]. This suppression reduces the tumor’s visibility to cytotoxic T cells, facilitating immune escape. Therapeutically, targeting MYC or its downstream pathways could restore APM function and enhance the efficacy of immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, by increasing tumor immunogenicity and improving T cell-mediated tumor clearance.

MYC-driven tumors employ a critical immune evasion strategy by suppressing the APM, which is essential for cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) to recognize and eliminate tumor cells. The APM involves major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) molecules, which present intracellular peptides, including tumor-derived neoantigens, on the cell surface to CTLs. MYC overexpression consistently downregulates MHC-I and other APM components, impairing antigen presentation and limiting immune detection [57]. In human melanoma and rat neuroblastoma models, MYC-driven MHC-I downregulation correlated with reduced tumor immunogenicity and increased tumor growth [58, 59]. In TNBC, elevated MYC expression was linked to reduced MHC-I levels. However, restoring interferon signaling increased MHC-I expression, reversing MYC-driven immune evasion and promoting tumor regression [56]. In addition to MHC-I suppression, MYC-driven tumors impair the MHC-II pathway, crucial for activating CD4⁺ T helper cells. In BCL, MYC overexpression downregulates MHC-II and associated APM components, limiting CD4⁺ T cell-mediated antitumor responses. Importantly, pharmacological inhibition of MYC restores MHC-II expression and enhances tumor cell recognition by CD4⁺ T cells, demonstrating MYC’s influence on both arms of antigen presentation [57]. MYC also inhibits dendritic cell (DC)-mediated cross-presentation by upregulating immune checkpoint proteins CD47 and PD-L1. CD47 interacts with SIRP

Several mechanisms contribute to MYC-mediated suppression of the APM machinery. In neuroblastoma, MYCN suppresses MHC class I expression by downregulating the p50 subunit of nuclear factor-kappa beta (NF-

Given the central role of MYC in suppressing antigen presentation, several therapeutic strategies have been explored. Recent research highlights the potential of combining PD-L1 and CTLA-4 blockade to recruit pro-inflammatory macrophages expressing CD40 and MHCII, partially reversing MYC-driven APM suppression [47]. Additionally, epigenetic modulators like HDAC inhibitors have shown efficacy in upregulating APM components, restoring immune visibility of MYC-driven tumors [66]. Preclinical studies further suggest that TAK-981, a SUMOylation inhibitor, can enhance antigen presentation by upregulating APM components, thereby sensitizing MYC-driven tumors to immune checkpoint blockade [64]. These approaches demonstrate the potential of targeting APM components to counteract MYC-induced immune suppression and improve therapeutic outcomes.

MYC activation significantly impacts immune cell recruitment and behavior within the TME, influencing various cancer types. In HCC, MYC overexpression drives the secretion of cytokines and chemokines, such as CCL5, which recruit PMN-MDSCs and Tregs, leading to T cell suppression and promoting tumor progression [49]. In osteosarcoma, elevated MYC expression is associated with reduced immune cell infiltration, including macrophages [67]. MYC inhibition using JQ-1 improves T cell recruitment and dendritic cell–T cell interaction, promoting tumor-specific CTL activation and enhancing the response to ICB therapy. Combining JQ-1 with anti-PD-1 therapy has shown promising potential in osteosarcoma treatment [45, 67]. In HCC, genetic alterations involving MYC significantly influence tumor-infiltrating T cells and their response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). ‘Cold’ tumors with MYC alterations show improved sensitivity to anti-PD-1 therapy when combined with sorafenib, emphasizing the need for tailored therapeutic strategies based on genetic context [68]. Kortlever et al. [69] demonstrated that MYC activation in a KRAS-driven lung cancer led to the influx of immunosuppressive macrophages and the exclusion of T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells. Anti-PD-L1 therapy alone failed to induce tumor regression; however, combination therapy with MYC inhibitors restored immune cell infiltration and reduced tumor burden. MYC-driven tumors recruit tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) that express PD-L1, further promoting T cell exhaustion and immune tolerance [17, 70].

These findings collectively highlight MYC’s pivotal role in regulating immune cell infiltration across different cancer types.

Studies have demonstrated that MYC influences cancer development through various mechanisms, including cytokine modulation, immune checkpoint upregulation, and interaction with other oncogenic pathways [71, 72].

MYC-driven immune evasion occurs through multiple pathways, including suppression of immune-related gene expression. MYC facilitates immune evasion in ovarian cancer by downregulating nuclear receptor coactivator (NCOA)4, suppressing ferritin autophagy, and inhibiting ferroptosis. This prevents the release of immune-activating damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) like high mobility group box (HMGB)1, thereby reducing immune cell infiltration and activation in the tumor microenvironment. By limiting immune responses, MYC promotes tumor immune evasion and progression [73]. Similarly, in TNBC, MYC hyperactivation represses stimulator of interferon genes (STING), a critical regulator of innate immunity. Reduced STING expression impairs downstream signaling pathways that produce key T cell chemokines, including CCL5, CXCL10, and CXCL11, thereby reducing the recruitment of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), such as cytotoxic CD8⁺ T cells, and contributing to tumor progression.

MYC collaborates with key oncogenic pathways, including KRAS, wingless-related integration site (WNT), alternate reading frame (ARF), and tumor protein p53 (TP53), to drive cancer progression and immune evasion [72, 74]. These oncogenes function synergistically, with KRAS inducing MYC expression and enhancing the translation of MYC and ARF6 mRNAs, which are tailored for robust expression during heightened energy production. MYC supports tumor metabolism by promoting mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation, while ARF6 protects mitochondria from oxidative damage and facilitates invasion, metastasis, and immune checkpoint activation. This cooperative network is particularly prominent in aggressive cancers like pancreatic cancer and is further exacerbated by TP53 mutations [75]. The cooperation between MYC and oncogenic KRAS establishes a profoundly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by coordinating the transcriptional upregulation of cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-10, transforming growth factor

MYC-driven tumors exhibit altered cytokine expression that promotes immune evasion. MYC hyperactivation reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-2, interferon-gamma (IFN-

Continued research into MYC-driven mechanisms of immune evasion and clinical evaluation of MYC-targeted therapies will be essential for advancing treatment strategies.

MYC is a central regulator of T cell function, dictating metabolic reprogramming, differentiation, and immune checkpoint expression in the tumor microenvironment. Its hyperactivation fuels tumor glycolysis and amino acid consumption, depriving T cells of essential nutrients and driving metabolic exhaustion, impaired proliferation, and diminished effector responses [98]. MYC directly influences T cell fate by controlling amino acid transporter expression, orchestrating metabolic pathways critical for activation and expansion [99]. In highly glycolytic tumors, MYC-driven lactate accumulation enhances PD-1 expression in Tregs, shifting the immune balance toward suppression and undermining immune checkpoint blockade efficacy [100]. Furthermore, MYC upregulates PD-L1 expression in tumors, directly inhibiting T cell activation and promoting immune evasion through PD-1/PD-L1 interactions [101]. By orchestrating both metabolic control and immune suppression, MYC establishes a hostile environment that enforces T cell dysfunction, positioning it as a crucial target for immunotherapeutic strategies aimed at reprogramming T cell responses and enhancing antitumor immunity.

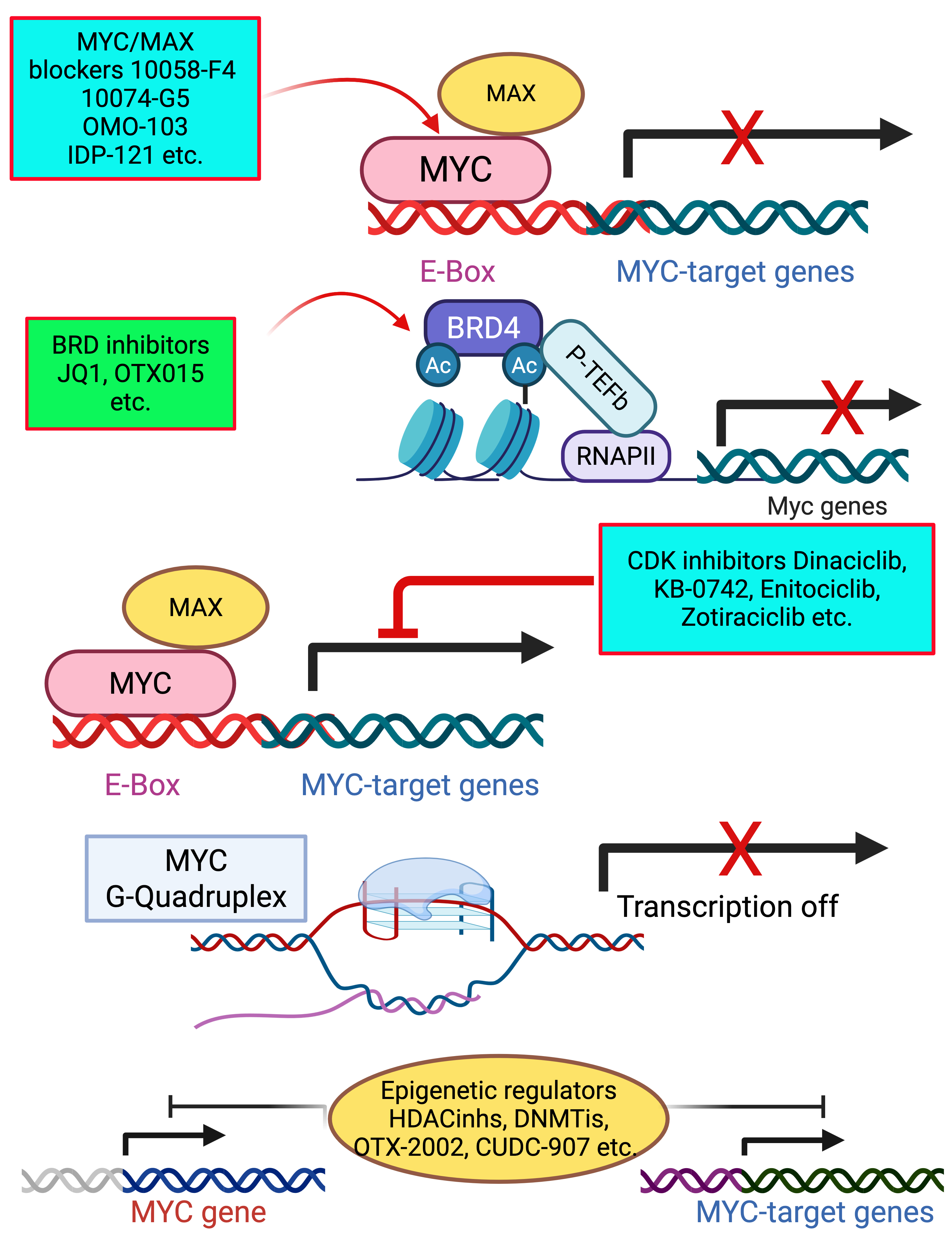

Numerous therapeutic strategies have been developed to target MYC and its associated pathways, including both direct inhibition and indirect approaches [102, 103, 104, 105]. Fig. 2 illustrates an overview of strategies for targeting MYC in cancer therapy.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Overview of strategies for MYC inhibition through different therapeutic strategies. MYC/MAX blockers (10058-F4, 10074-G5) prevent MYC-MAX dimerization, blocking transcription of MYC target genes. BET inhibitors (JQ1, OTX015) disrupt BRD4-mediated transcriptional activation of MYC by preventing RNA polymerase II recruitment. CDK inhibitor (Dinaciclib) suppresses MYC-driven transcription by targeting cyclin-dependent kinases. G-quadruplex stabilizers promote the formation of G-quadruplex structures in the MYC promoter, repressing MYC transcription. These approaches provide potential therapeutic strategies for targeting MYC-driven cancers. BET, bromodomain and extra terminal domain; MAX, MYC-associated factor X; BRD4, bromodomain containing protein 4; CDK, cyclin dependent kinase. Created with Biorender.com.

Direct targeting of MYC focuses on disrupting MYC-MYC-associated factor X (MAX) dimerization using small molecule inhibitors or reducing MYC expression via BET inhibitors. These strategies have shown potential in preclinical models and early clinical trials.

MYC functions as a transcription factor by forming a heterodimer with MAX, a process essential for its transcriptional activity. Small molecule inhibitors that disrupt this dimerization, such as 10058-F4 and 10074-G5, prevent MYC from binding to E-box sequences in target gene promoters, thereby inhibiting its transcriptional activity and tumor growth [106, 107]. Preclinical models have shown promise for these inhibitors in various MYC-driven cancers. IDP discovery pharma (IDP)-121 is a direct MYC inhibitor designed as a stapled peptide that disrupts MYC-MAX interaction by binding to MYC with high affinity (Kd = 400 nM), preventing its transcriptional activity and demonstrating efficacy in hematologic and solid tumors, making it a promising MYC-targeted therapy currently in clinical trials [108]. WBC100 is a direct MYC degrader that selectively targets the nuclear localization signals (NLS)1-Basic-NLS2 region of MYC, inducing its degradation via the E3 ligase C-terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP)-mediated 26S proteasome pathway, leading to apoptosis in MYC-overexpressing cancer cells and demonstrating potent tumor regression in preclinical models [109]. The combination of MYC inhibition by MYCi975 and PD-1 blockade synergistically suppresses tumor progression by remodeling the tumor immune microenvironment [38]. The combination of MYC inhibition and immune checkpoint blockade, specifically anti-PD-L1, significantly enhances tumor regression and extends survival in MYC-driven TNBC. Suppressing MYC increases tumor cell MHC-I expression and immune infiltration, sensitizing tumors to PD-L1 inhibition. Furthermore, the addition of a TLR9 agonist and OX40 agonist to anti-PD-L1 therapy enhances immune activation, leading to complete tumor regression and protection against recurrence, demonstrating a promising strategy to overcome MYC-driven immune evasion [110].

Omomyc, a dominant-negative mutant of MYC, interferes with MYC-MAX dimerization and blocks its transcriptional activity. This peptide has demonstrated efficacy in various preclinical cancer models and is currently being evaluated in clinical trials [111, 112]. Unlike small molecules, Omomyc directly targets MYC, offering a unique therapeutic approach. Omomyc demonstrated a favorable safety profile, with most adverse effects being mild (Grade 1), primarily low-grade infusion-related reactions commonly observed with biologic therapies. Additionally, the drug exhibited appropriate pharmacokinetic (PK) properties at the recommended dose, with minimal to no signs of immunogenicity [112].

Indirect approaches to target MYC aim to disrupt MYC-driven processes by inhibiting transcriptional regulators, exploiting synthetic lethality, using dominant-negative peptides, and employing epigenetic modulators.

BET proteins, particularly bromodomain containing protein 4 (BRD4), are key regulators of MYC transcription. BET inhibitors, such as JQ1 and OTX015, competitively bind to bromodomains on BET proteins, displacing BRD4 from chromatin and leading to decreased MYC expression. In preclinical models, BET inhibitors have demonstrated synergy with immune checkpoint inhibitors, enhancing antitumor immune responses [113, 114, 115]. Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating BET inhibitors in hematologic malignancies and solid tumors, with encouraging early-phase results. The combination of BET inhibitors with the BCL-2 antagonist ABT-199 effectively downregulates MYC and CD47 in Lymphoma, reducing cancer cell proliferation and improved treatment outcomes [116].

MYC expression relies on continuous transcription elongation mediated by CDK9, a component of the positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) complex. CDK9 inhibitors, such as LY2857785, flavopiridol, and dinaciclib, have shown efficacy in reducing MYC expression and inducing apoptosis in MYC-driven tumors [117, 118, 119, 120, 121]. These inhibitors are currently being tested in phase I/II clinical trials, with potential for combination with standard therapies. Enitociclib is an indirect MYC inhibitor that targets CDK9, suppressing RNA polymerase II-mediated transcription, leading to the depletion of MYC and anti-apoptotic myeloid cell leukemia 1 (MCL-1) in MYC+ lymphomas. In preclinical models and patient samples, enitociclib demonstrated tumor growth inhibition, apoptosis activation, and transcriptional downregulation, with clinical activity observed in double-hit diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DH-DLBCL), highlighting its potential as a novel therapeutic approach for MYC-driven lymphomas [122]. Zotiraciclib (TG02) is an indirect MYC inhibitor that suppresses MYC expression by targeting CDK9, leading to depletion of survival proteins like MYC and MCL-1 in glioblastoma. In a Phase Ib trial (EORTC 1608), TG02 showed dose-dependent toxicity, including neutropenia and hepatotoxicity, with limited single-agent efficacy, highlighting the need for further investigation into CDK9 as a therapeutic target in glioblastoma [123]. KB-0742, a potent CDK9 inhibitor, effectively suppresses MYC protein expression and RNA polymerase II activity, leading to significant anti-tumor effects in MYC-overexpressing TNBC models [124]. KB-0742, shows promising clinical activity in MYC-driven and transcriptionally addicted solid tumors by disrupting MYC-dependent transcription, with manageable toxicity and early signs of durable disease control. Ongoing trials support its use in MYC-overexpressing cancers [125].

MYC-driven cancers exhibit specific vulnerabilities, including dependency on certain metabolic pathways and stress response mechanisms. Synthetic lethality-based strategies exploit these vulnerabilities. For example, inhibition of glutaminase (GLS1), an enzyme essential for glutamine metabolism in MYC-overexpressing tumors, creates a metabolic crisis that selectively kills cancer cells [126, 127]. Similarly, targeting DNA damage response pathways with poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in combination with MYC inhibitors has shown promise in preclinical studies [128, 129].

MYC is regulated not only by genetic mutations but also through epigenetic changes, which can modulate its expression at both transcriptional and translational levels. Recent studies demonstrate that targeting MYC’s epigenetic modifiers effectively inhibits cancer cell proliferation, sensitizes chemoresistant cells, and improves patient outcomes [130, 131, 132]. Epigenetic therapies targeting MYC, offer promising strategies for improving cancer immunotherapy. The combination of DNA-demethylating agents (DNMTis) and histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) effectively suppresses MYC signaling and enhances immunotherapy in NSCLC. This strategy increases antigen presentation, activates interferon pathways, and elevates the T cell chemoattractant CCL5. In preclinical models, it reverses tumor immune evasion and reprograms T cells into memory and effector states, providing a promising avenue to improve immune checkpoint therapies [66]. OTX-2002 is an indirect MYC inhibitor that functions as an Epigenomic controller (MYC-EC), downregulating MYC expression pre-transcriptionally via targeted DNA methylation modifications, demonstrating durable MYC suppression, tumor inhibition, and manageable safety profiles in early-phase clinical trials [133, 134]. Fimepinostat is an indirect MYC inhibitor that simultaneously targets HDAC and phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K), leading to MYC downregulation and apoptosis in MYC-driven cancers. Preclinical studies demonstrate its efficacy in DH-DLBCL, nuclear protein in testis (NUT) midline carcinoma (NMC), and other MYC-dependent tumors, with significant tumor suppression observed in xenograft and transgenic models, supporting its potential as a targeted therapy for MYC-driven malignancies [135, 136]. The combination of MYC inhibition with HDAC inhibition demonstrates a promising therapeutic strategy for diffuse midline gliomas (DMG) harboring the H3K27M mutation. Sulfopin, a MYC-targeting peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 inhibitor (PIN1) inhibitor, combined with the HDAC inhibitor Vorinostat, significantly reduces tumor cell viability, downregulates oncogenic pathways like mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), and leads to substantial tumor suppression in patient-derived xenograft models. This dual-targeting approach effectively disrupts the epigenetic and transcriptional dysregulation driving DMG, offering a potential treatment avenue for these highly resistant pediatric brain tumors [137].

G-quadruplexes (G4s) are four-stranded DNA structures in guanine-rich regions, including the MYC promoter, where they act as transcriptional silencers [138, 139, 140]. Small molecules that stabilize MYC G4 structures can inhibit MYC transcription, leading to reduced cancer cell proliferation. Compounds like APTO-253 and automated ligand identification system (ALIS)-identified ligands have shown efficacy in downregulating MYC expression, inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, particularly in leukemia models [141, 142]. In a phase I clinical study, APTO-253 demonstrated anti-leukemic activity by selectively reducing MYC mRNA and protein levels through G-quadruplex (G4) stabilization, while inducing p21 expression, cell-cycle arrest, and apoptosis without causing myelosuppression. Its active form, Fe(253)₃, was shown to stabilize G4 structures in MYC and KIT promoters, supporting its targeted mechanism of action [141]. CX-3543 (Quarfloxin), stabilizes G-quadruplex structures in the MYC promoter, leading to transcriptional repression. Similarly, G-quadruplex conformation-05 (GQC-05) (NSC338258) is a potent and selective stabilizer of the MYC G4, reducing MYC transcription by altering protein binding to the nuclease hypersensitive element III (NHE III) (1) promoter region, providing strong evidence for intracellular G4-mediated transcriptional regulation [143].

Despite the intrinsic challenges in directly targeting MYC, recent advances in inhibition strategies—including dimerization disruption, transcriptional repression, and synthetic lethality—have highlighted significant therapeutic potential. Notably, combination approaches that integrate MYC inhibition with immune checkpoint blockade and metabolic modulators have demonstrated promise in overcoming immune evasion and enhancing treatment outcomes in MYC-driven cancers. Preclinical and early clinical studies support the efficacy of these strategies; however, challenges such as tumor heterogeneity, toxicity, and limited response in solid tumors remain. To address these barriers, future research should prioritize patient stratification using immune gene signature sets to better predict responses and guide treatment. Continued exploration of these combination therapies may ultimately expand the therapeutic landscape for patients with MYC-overexpressing malignancies.

MYC-targeted therapies present significant challenges due to their widespread effects on normal cellular processes, leading to systemic toxicity, metabolic disruption, immune modulation, and therapy resistance. MYC inhibition impacts rapidly proliferating tissues, particularly in the bone marrow and gastrointestinal epithelium, resulting in myelosuppression, anemia, neutropenia, and gastrointestinal toxicity, as observed in clinical trials of OMO-103 [112]. Additionally, MYC plays a pivotal role in cellular metabolism, and its suppression leads to glucose and glutamine metabolism dysregulation, causing hypoglycemia, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and muscle wasting, significantly affecting energy homeostasis [144]. The immune system is also heavily influenced by MYC inhibition, with studies indicating impaired interferon signaling, PD-L1 upregulation, and disrupted T-cell and NK-cell function, which can paradoxically lead to immune evasion and reduced tumor immunogenicity, thereby limiting the effectiveness of immunotherapies [86]. Another major limitation of MYC-targeted therapies is tumor resistance, as cancer cells can activate alternative oncogenic pathways such as rat sarcoma mitogen activated protein kinase (RAS-MAPK) and PI3K-AKT-mTOR, allowing them to bypass MYC inhibition and sustain growth through metabolic reprogramming [130]. Addressing the off-target effects of MYC-targeted therapies requires a multifaceted approach, combining epigenetic modulation, metabolic inhibitors, synthetic lethality, immune-based strategies, precision drug delivery, and protein interaction disruptors. Clinical trials are actively exploring these methods to improve MYC-targeted therapy while minimizing systemic toxicity, ultimately enhancing the safety and efficacy of these promising treatments.

The MYC oncogene plays a central role not only in tumor initiation and progression but also in orchestrating immune evasion within the TIME. MYC-driven tumors employ a range of immunosuppressive strategies, including transcriptional upregulation of immune checkpoints such as PD-L1 and CD47, suppression of antigen presentation machinery (MHC class I and II), modulation of cytokine signaling, and recruitment of immunosuppressive cells such as Tregs and MDSCs. These mechanisms result in impaired T cell activation and infiltration, reduced tumor immunogenicity, and resistance to ICB therapies. Although direct pharmacological inhibition of MYC remains a significant challenge due to its disordered structure and lack of enzymatic activity, several indirect approaches have shown promise. These include CDK9 inhibitors (e.g., KB-0742), which disrupt MYC transcriptional elongation, BET inhibitors (e.g., JQ1), which reduce MYC expression by displacing BRD4 from chromatin, and G-quadruplex stabilizers (e.g., APTO-253), which inhibit MYC transcription by stabilizing secondary DNA structures in its promoter region. These agents not only suppress MYC-driven oncogenic signaling but also contribute to remodeling the TIME by enhancing antigen presentation, restoring interferon signaling, and promoting immune cell infiltration and cytotoxicity. Importantly, combining MYC-targeted therapies with immunotherapies particularly checkpoint inhibitors has demonstrated synergistic anti-tumor effects in preclinical models of MYC-overexpressing cancers such as TNBC, NSCLC, and HCC. Nevertheless, challenges remain, including tumor heterogeneity, compensatory pathway activation, systemic toxicity, and the need for predictive biomarkers to guide patient selection.

Future research should focus on the integration of multi-omics approaches to identify predictive immune-MYC gene signatures, development of rational combination regimens, and implementation of novel delivery platforms to enhance therapeutic specificity. The exploration of rational combination regimens integrating MYC inhibitors with ICB, metabolic inhibitors, epigenetic drugs, or innate immune activators offers a promising path forward. Additionally, advances in drug delivery systems, such as nanoparticle-based carriers, tumor-targeted prodrugs, and proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs), may enhance specificity and minimize systemic toxicity. Continued investigation into the mechanistic underpinnings of MYC’s influence on the TIME, alongside translational and clinical research, will be critical for unlocking the full therapeutic potential of this approach and improving outcomes for patients with MYC-driven cancers.

Conceptualization by JTY and BKN; methodology, BKN; software, BKN; validation, JTY; formal analysis, BKN; investigation, JTY; resources, JTY; data curation, BKN; writing original draft preparation, BKN; writing review and editing, JTY; visualization, JTY; supervision, JTY; project administration, JTY; funding acquisition, JTY. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

JTY was supported by National Institute of Health grants 1R01EB026453, 1R01CA21554, and 1R21CA267914 and the Osteosarcoma Institute.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.