1 Laboratory for Oxidative Stress (LabOS), Division of Molecular Medicine, Rudjer Boskovic Institute, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia

2 Uniss PhD School, School of the University of Sassari, 07100 Sassari, Italy

Abstract

The oxidation of lipids, notably of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), under oxidative stress is a self-catalyzed chain reaction that generates reactive aldehydes, among which 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) is considered to act as a second messenger of free radicals. The pleiotropic effects of 4-HNE, which include the regulation of cellular antioxidant capacities, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, are concentration-dependent as they depend on cell type. Therefore, 4-HNE has important roles in various pathophysiological processes and the pathogenesis of acute and chronic diseases, especially degenerative and malignant diseases. Before 4-HNE was recognized as a signaling molecule, it was known to be the cytotoxic mediator of oxidative stress, acting even if lipid peroxidation was not present, because it remains bound to proteins, changing their structure and function. Research in this field has revealed several novel modes of activities of 4-HNE associated with cell death, including not only apoptosis/programmed cell death and necrosis but also ferroptosis, autophagy, pyroptosis, necroptosis, parthanatos, oxeiptosis and cuproptosis. This review shortly summarizes these findings, aiming to encourage further research in the field that might open new ways to use 4-HNE as the bioactive factor for targeted cell death, in particular cancer cells.

Keywords

- oxidative stress

- cell death

- apoptosis

- necrosis

- ferroptosis

Initially thought to be detrimental by-products of metabolism, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are now recognized as important regulators of diverse cellular functions and processes via redox signaling [1, 2]. The imbalance in the production of ROS and antioxidants, which favors prooxidants, causes oxidative stress. Antioxidant defenses include both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants. The thioredoxin system, the glutathione (GSH) system, peroxiredoxin, superoxide dismutase, and catalase are the main endogenous antioxidant defenses [3]. The nuclear factor, erythroid-derived 2-like 2 (Nrf2), which is endogenously inhibited by Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), regulates the expression of a multitude of antioxidants and is essential for maintaining redox homeostasis. Under low oxidative stress, Keap1 dissociates from Nrf2, promoting the expression of antioxidant genes [3]. Excessive ROS damage macromolecules, including lipids, thus triggering lipid peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) [4]. Lipid peroxidation of n-6 PUFAs produces the bioactive aldehyde 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), which can have either direct or indirect effects on cellular signaling pathways and functions. The 4-HNE directly interferes with normal cellular processes, enzymatic functions, and functions of organelles [5, 6, 7]. The presence of a carbonyl group at the C1 position, a hydroxyl group, and an

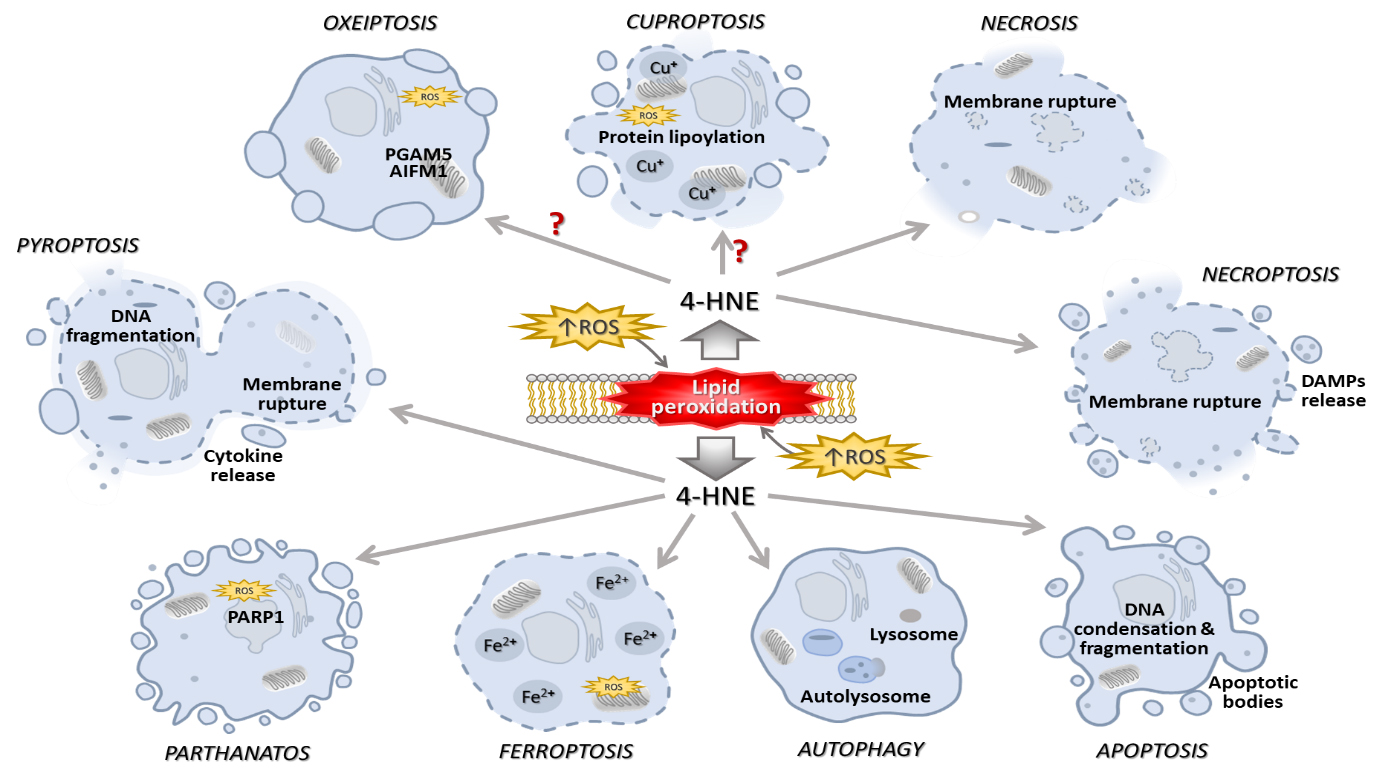

The most important biological process that occurs in response to harmful events is death, which may be regulated or uncontrolled. Except for necrosis, which is an acute, irreversible, and unspecific process of cellular death, there are several distinct cell death mechanisms, besides apoptosis, all of which are tightly regulated by intracellular signaling pathways. Some scientists subdivide programmed cell death into non-lytic forms, such as apoptosis, in which membrane integrity is maintained, and lytic forms, such as pyroptosis, necroptosis, and ferroptosis, in which membrane integrity is not maintained and which lead to cell disintegration. Apoptosis is a homeostatic process that keeps cell populations in tissues stable and occurs naturally during development and aging. In immunological responses or when cells are damaged by different noxious pathogens, diseases, or harmful substances, apoptosis also takes place as a protective mechanism [31]. To date, 4-HNE is known to be involved in a variety of cell death mechanisms (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Elevated ROS levels trigger lipid peroxidation, resulting in 4-HNE formation that may, depending on its concentration and macromolecular targets, be implicated in the diverse types of cell death. The figures are drawn in PowerPoint (Microsoft Office 2019, Redmond, WA, USA). Abbreviations: ROS, reactive oxygen species; 4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; PGAM5, phosphoglycerate mutase 5; AIFM1, apoptosis inducing factor mitochondria associated 1; PARP1, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1.

Although the focus of this review will be on the roles of 4-HNE in apoptosis, its involvement in other mechanisms of cell death will also be discussed.

Various mechanisms and phenotypes of regulated cell death are now known, while apoptosis was the first type of regulated cell death discovered. 4-HNE has been shown to play a role in apoptosis as well as in other forms of regulated cell death. The following is, therefore, an overview of the known mechanisms and involvement of 4-HNE in apoptosis, ferroptosis, autophagy, pyroptosis, necroptosis, parthanatos, oxeiptosis, and cuproptosis.

Apoptosis, a programmed cell death, is a regulated process of intracellular, biochemical, and morphological changes that lead to cell death [32]. Apoptosis is tightly regulated by pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins, and the genes required for appropriate apoptosis are evolutionarily conserved from nematodes to Homo sapiens [33]. Two major signaling pathways can trigger apoptosis: the extrinsic, often referred to as the “death receptor pathway”, and the intrinsic, also known as the “mitochondrial pathway”.

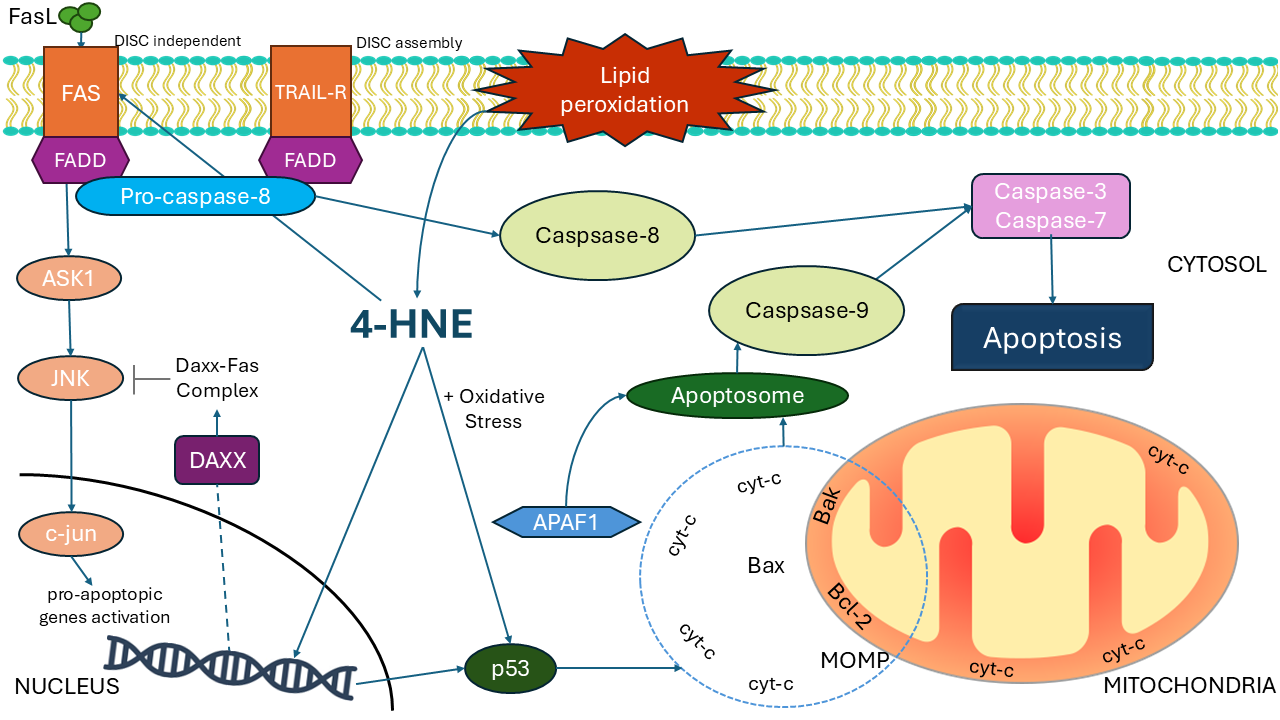

Transmembrane receptor-mediated interactions are part of the death receptor pathway, also called the extrinsic mechanism of apoptosis. Ligand-receptor complexes are formed when different chemicals bind to their respective death receptors. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)/TNF-receptor 1 (TNF-R1), Fas ligand (FasL)/Fas receptor (FasR), and TNF-related inducing apoptotic ligand (TRAIL)/TRAIL-receptor 1 are some of these complexes. The adaptor molecule FAS-associated death domain protein (FADD) identifies ligand-receptor complexes and binds to the receptors via death domains. When caspase-8 is activated, it separates from the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) formed from the adaptor and bound caspase-8. This triggers a series of caspases that further promote apoptosis [34].

The binding of FasL to its receptor FasR is an example of 4-HNE-mediated apoptosis. The 4-HNE-induced apoptosis is accompanied by the activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and caspase-3 [35]. While it was shown that 4-HNE activates JNK, caspase-3, and apoptosis in human lens epithelial cells HLE B-3 and induces Fas expression in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, there are findings indicating that 4-HNE-mediated regulation of Fas is a generalized phenomenon, not strictly limited to the specific cell type [36]. It appears that 4-HNE activates the Fas signaling pathway primarily through a DISC-independent mechanism that does not involve FADD or caspase-8. This is supported by the discovery that 4-HNE can induce Fas-dependent apoptosis in Jurkat cells lacking pro-caspase-8. In vitro, the death receptor Fas, which has an extracellular domain with many cysteines, has been shown to form adducts with 4-HNE [37]. In the absence of DISC involvement, 4-HNE-induced Fas activation triggers downstream signaling via apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1), JNK, and caspase-3. After JNK phosphorylation, the c-jun transcription factor translocates to the nucleus and regulates the expression of pro-apoptotic genes. 4-HNE also activates a negative feedback loop via death domain-associated protein (Daxx), a nuclear protein involved in stress responses. 4-HNE also triggers the induction of Daxx and facilitates its release from the nucleus to the cytosol, where it cooperates with Fas to inhibit downstream pro-apoptotic signaling and modulate apoptosis. Depletion of Daxx further amplifies the activation of JNK and caspase-3, intensifying 4-HNE-induced apoptosis [37]. 4-HNE promotes the expression of both Daxx and Fas [38] and can promote the export of Daxx from the nucleus to the cytoplasm by forming covalent bonds with it through histidine residues. The ASK1-JNK signaling pathway and activation of apoptosis can be affected by the Fas-Daxx binding. While the pathway regulated by Fas-ASK1 and JNK is important and causes major damage under oxidative stress, Daxx-Fas coupling restricts the activation of apoptosis under moderate stress. Since 4-HNE is diffusible, as shown in vivo, this negative loop can maintain tissue integrity. Since Daxx acts in both the cytosol and the nucleus, its activity as a pro- or anti-apoptotic agent may vary. Differences between types of cells and the relative significance of the JNK and Fas pathways further indicate the complexity of apoptosis regulation by 4-HNE. A schematic representation of the involvement of 4-HNE in apoptosis is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The involvement of 4-HNE in apoptosis. 4-HNE, a by-product of lipid peroxidation, induces apoptosis by activating FAS and the TRAIL pathways. The ASK1/JNK pathway triggers AP-1-dependent transcription through the DISC-independent route. After JNK phosphorylation, the c-jun transcription factor translocates to the nucleus and regulates the expression of pro-apoptotic genes. Exported Daxx is involved in the regulation of the FAS pathway. The intrinsic apoptotic pathway is induced by oxidative stress, p53, and mitochondrial membrane disturbances. The figures are drawn in PowerPoint (Microsoft Office 2019, Redmond, WA, USA) and Inkscape (Software Freedom Conservancy, Brooklyn, NY, USA). Abbreviations: 4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; AP-1, activator protein 1; ASK1, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; Daxx, death domain-associated protein; FADD, Fas-associated protein with death domain; FasL, Fas ligand; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; cyt-c, cytochrome c; MOMP, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization; TRAIL, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; Bak, Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer; Bax, Bcl-2-associated X protein; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2.

The intrinsic, i.e., mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis is the most common mechanism of apoptosis in vertebrates. Activation of this pathway can be triggered by toxic substances, viral infections, DNA damage, radiation exposure, or growth factor deprivation [31, 39]. 4-HNE, a product of lipid peroxidation, damages mitochondrial DNA and activates the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. This damage caused by 4-HNE results in respiratory enzyme defects, lowering the capacity of reducing potential and energy production. 4-HNE can be produced via cytochrome c (cyt-c) oxidation of cardiolipin, which is an essential phospholipid found in mitochondrial membranes. Cardiolipin oxidation is required for further steps of intrinsic apoptosis [40]. It activates mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and causes the activation of proteins of the B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family, which contain pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic factors and regulate the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Under physiological cellular conditions, these proteins form heterodimers with Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) and Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer (Bak) proteins from pro-apoptotic groups, blocking their action and maintaining the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane. 4-HNE can induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis as shown in mouse leukemic macrophage cell line, with common signs of intrinsic apoptosis, such as DNA fragmentation, pro-apoptotic protein upregulation, and anti-apoptotic protein downregulation [41, 42]. When a cell is threatened by DNA damage, BH3-only proteins are expressed, initiating apoptosis and binding anti-apoptotic factors, releasing Bax and Bak proteins. Anti-apoptotic factors, especially myeloid cell leukemia-1, are ubiquitinated and degraded to induce apoptosis. Uninhibited pro-apoptotic factors Bax and Bak form oligomers that insert into the outer mitochondrial membrane, leading to pores and permeabilization. Hence, soluble proteins from the intramembrane space of mitochondria spill into the cytoplasm [31, 43], so cyt-c also leaks from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm and binds to the apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (Apaf1). This leads to the activation of Apaf1, which is activated by a circular homoheptameric complex denoted apoptosome. The main role of the apoptosome is to activate the inactive pro-caspase-9. For the proper activity of caspase-9, proteolytic cleavage is not as important as binding to the apoptosome. The holoenzyme of apoptosome and caspase-9 activates executioner caspases (3 and 7) [31, 43]. It has been shown that caspase-3 and caspase-7 are crucial for apoptosis. There is a functional redundancy between caspase-3 and caspase-7, but they do not overlap completely [44]. However, caspase-3 is the main executor of the process, while caspase-7 has more of a supporting role by causing an accumulation of ROS [45]. Research on sympathetic and hippocampal neurons showed that the downregulation of caspase-3 and caspase-7 protects from 4-HNE-induced death [46]. In age-related sarcopenia, the increase in 4-HNE generation during muscle cell apoptosis results in the inactivation of anti-apoptotic protein and activation of caspase-9 and JNK [47], with the same observation made in PC-12 pheochromocytoma cells [48], and RKO colon cancer cells [49].

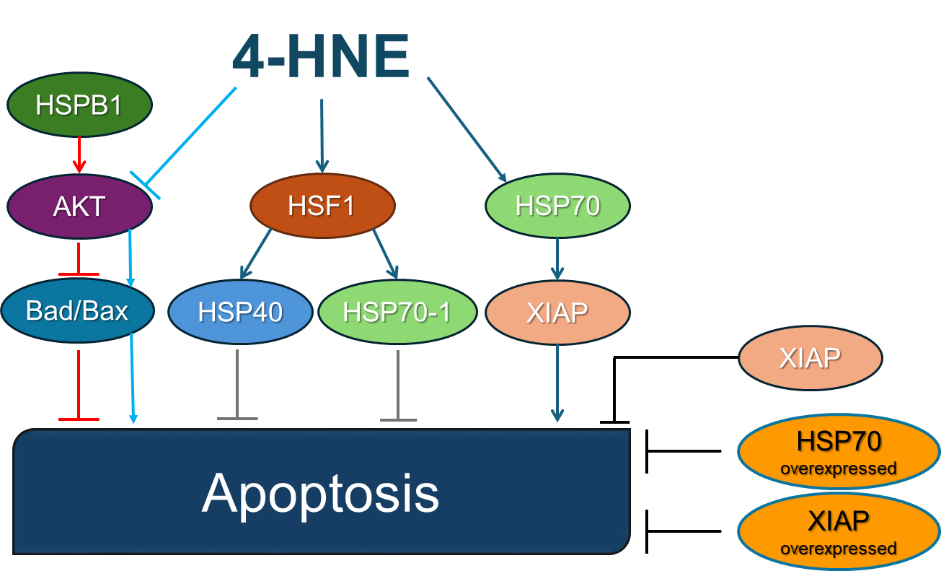

Apoptotic proteins often interact with heat shock proteins (HSP), which are molecular chaperones that enhance a cellular ability to withstand various types of stress. HSPs can regulate apoptosis at multiple levels [50]. HSP70 plays a crucial role in regulating the intrinsic apoptosis pathway by regulating apoptosis at the level of mitochondrial permeabilization and preventing the recruitment of caspases and the formation of apoptosome [51]. One study showed that 4-HNE did not alter the expression of HSP70 protein, but it caused late apoptosis in retinal pigment epithelial cells ARPE-19 cells along with increased levels of 4-HNE-modified HSP70. While the expression of the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) is downregulated by 4-HNE-modified HSP70, the 4-HNE-mediated apoptosis of ARPE-19 is reduced by overexpression of HSP70 or XIAP [52]. Interestingly, in addition to its pro-apoptotic effects, 4-HNE was also found to activate stress response pathways via heat shock factor 1 (HSF1), which stimulates the expression of HSP40 and HSP70-1, most likely due to 4-HNE disrupting the inhibitory relationship between HSP70-1 and HSF1 [53]. In addition, HSPB1 regulates the intrinsic pathway by activating the protein kinase B (Akt), preventing the activation of Bax, and inactivating the apoptosis initiator Bcl-2-associated death promoter (Bad). They indirectly reduce the activity of the intrinsic pathway by stabilizing the actin cytoskeleton and maintaining connections between cells. Exposure of cells to 4-HNE reduced the activity of Akt via 4-HNE-mediated Ser473 dephosphorylation [54], therefore, two possible pathways for 4-HNE-mediated downregulation of Akt were proposed, one dependent on protein phosphatase 2A and one independent of protein phosphatase 2A [35]. Tumor protein 53 (p53) is a transcription factor and tumor suppressor that regulates the expression of genes involved in apoptosis, DNA repair, and the cell cycle. The p53 is activated to protect and repair the cell when oxidative stress and DNA damage occur. However, p53 triggers cell death when the stress or damage reaches a certain threshold. By entering the mitochondria and binding to the anti-apoptotic factors Bcl-x and Bcl-2, p53 helps to activate the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis and initiate the transcription of pro-apoptotic genes of the Bcl-2 family. This enables the permeabilization of the mitochondrial membrane. It also promotes the activation of the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis by inducing the transcription of death receptor genes [39, 55]. The effect that 4-HNE has on HSPs is shown in Fig. 3, while the effect on p53 has been shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Heat shock proteins and 4-HNE in apoptosis. 4-HNE modifies HSP70 without altering its overall expression levels. Modified HSP70 downregulates the apoptosis-inhibitory protein XIAP, thereby indirectly enhancing apoptosis. Experimental overexpression of either HSP70 or XIAP effectively counteracts 4-HNE-induced apoptosis by providing stronger apoptotic inhibition. 4-HNE activates HSF1, leading to elevated expression of HSP40 and HSP70-1, which enhances the cellular stress response, providing protective, anti-apoptotic effects. HSPB1 stimulates Akt kinase, which inhibits pro-apoptotic proteins Bad and Bax, thereby preventing apoptosis under normal conditions. 4-HNE-mediated inhibition of Akt kinase removes this protective inhibition, indirectly activating Bad/Bax and promoting apoptosis. The figures are drawn in PowerPoint (Microsoft Office 2019, Redmond, WA, USA). Abbreviations: 4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; HSP, heat shock protein; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein; HSF1, heat shock factor 1; Akt, protein kinase B; Bad, Bcl-2-associated death promoter; Bax, Bcl-2-associated X protein.

In Jurkat, human T-cell leukemia cells treated with 4-HNE, glutathione depletion was found to directly activate caspases-8, -9, and -3. Instead of Fas-mediated glutathione release across the plasma membrane, oxidation by 4-HNE was the cause of the underlying glutathione depletion [56]. In HepG2 cells, 4-HNE was shown to trigger apoptotic signaling through both the p53-mediated intrinsic and Fas-mediated extrinsic pathways. 4-HNE activates Bax, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21), JNK, and caspase-3, which in turn triggers apoptosis via the p53 pathway in HepG2 cells [38]. DNA fragmentation, cytochrome c and apoptosis-induced factor release from mitochondria, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage, Bcl-2 downregulation, Bax overexpression, and caspase activation were among the conventional hallmarks of apoptosis that were demonstrated in 4-HNE-induced chondrocyte death by increased expression of p53 and Fas while suppressing pro-survival Akt kinase activity [57]. Moreover, the LNCaP hormone-sensitive prostate cancer cells showed enhanced anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic actions of 4-HNE in a time- and dose-dependent manner that corresponded with the activation of p53-mediated intrinsic apoptotic signaling. On the other hand, hormone-insensitive DU145 prostate cancer cells displayed reduced apoptosis and enhanced proliferation, while their JNK was continuously activated, but p53, p21, Bax, and caspase-3 were not [58].

In human umbilical vein endothelial cells subjected to heat stress, the accumulation of 4-HNE was induced by silencing aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2). An ALDH2 agonist (Alda-1) reduced the activation of inflammatory pathways, senescence, and apoptosis induced by heat stress. In an in vivo study in lung homogenates of mice subjected to whole-body heating, Alda-1 was shown to significantly reduce the accumulation of 4-HNE and the activation of p65 and p38 [59]. Morphological changes and DNA damage were observed in ARPE-19 retinal pigment epithelial cells after 4-HNE application, but the damage was able to be reversed with Fucoxanthin treatment [60].

Moreover, 4-HNE was shown to cause neuronal cell death by inducing aberrant expression of apoptotic markers, such as caspase-3, Bax, and p53. In neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, increased expressions of Bax and p53 were associated with HNE-induced oxidative stress. Increased caspase-3 expression and activity confirmed mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis [61]. 4-HNE was found to be associated with mortality and oxidative destruction of neurons after subarachnoid hemorrhage, especially in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus on the third day after injury. Administration of edaravone dexborneol strongly inhibited the increase of 4-HNE, reduced neuronal death, and improved long-term neurological outcomes by preventing the oxidative stress response associated with 4-HNE [25]. 4-HNE is widely viewed as a central factor in oxidative stress-mediated neuronal apoptosis. For example, researchers found 4-HNE adducts to neurofilaments in Alzheimer’s disease [62], while in Parkinson’s disease, it can cause neuronal cell death via adducts with proteins connected to the proteasome system [63]. Under conditions marked by elevated ROS, 4-HNE induces neuron death by binding to and altering transmembrane receptors, cytosolic enzymes, and even DNA, ultimately triggering apoptotic signaling cascades.

Furthermore, 4-HNE can impair mitochondrial function or reduce cellular antioxidant capacity, leading to additional ROS generation [64, 65, 66, 67]. Metabolic syndrome encompasses several interrelated metabolic disturbances, such as impaired glucose tolerance, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, obesity, and liver disease. In the context of diabetes, pancreatic

Therefore, it is certain that 4-HNE is a key mediator of oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and acts through various mechanisms. Its pathological significance underscores the importance of understanding its role in apoptosis and exploring targeted interventions to mitigate its detrimental effects in various diseases.

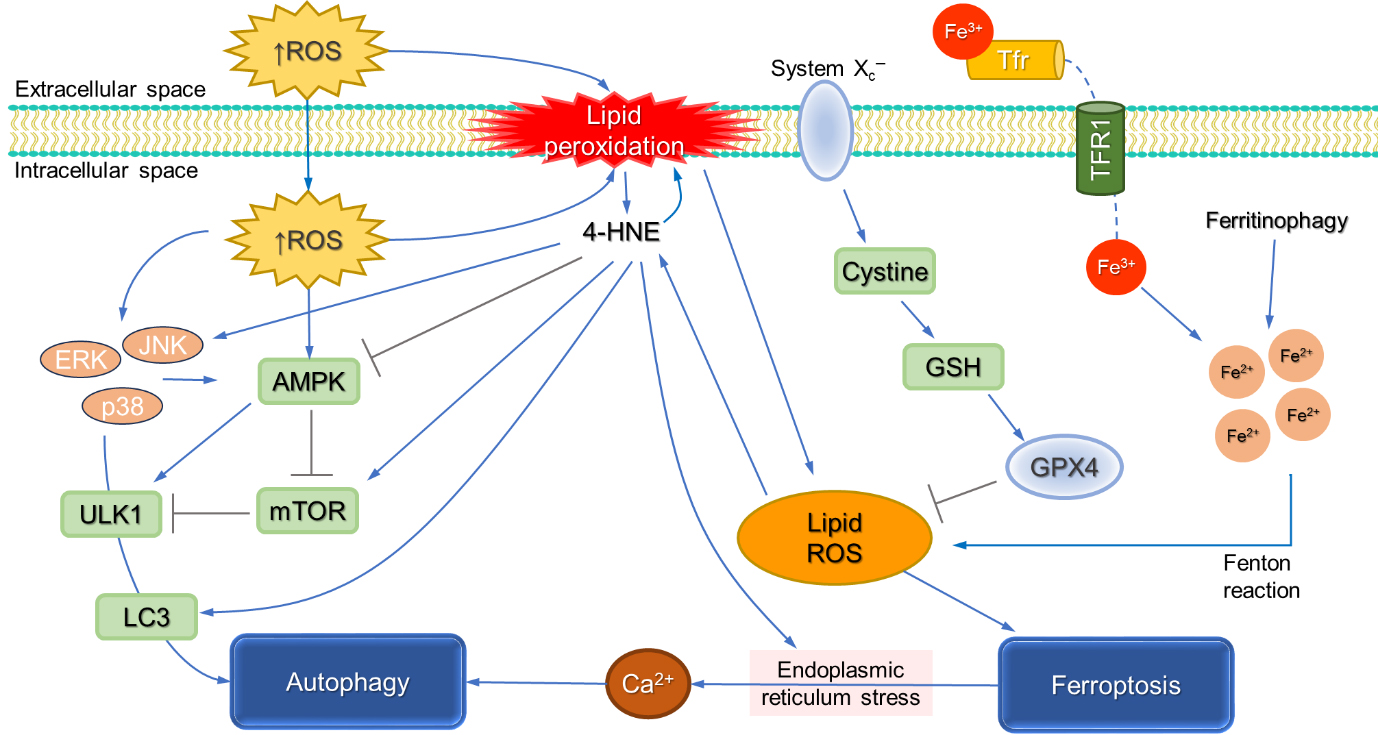

Lipid peroxidation is a hallmark of ferroptosis. In the presence of free intracellular iron, ferroptosis can be triggered by excessive accumulation of ROS, including lipid ROS. Lipid ROS may be reduced by the action of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and thus prevent ferroptosis [69]. On the other side, direct inhibition or inactivation of GPX4, inhibition of GSH biosynthesis, or excessive intracellular iron uptake are all conditions that favor ferroptosis-induced cell death [70]. The cystine/glutamate antiporter system (Xc–) is essential for the intracellular production of GSH by providing cystine. In recent years, GSH-independent ferroptosis defense mechanisms have been identified based on ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) and dihydroorotate dehydrogenase [71, 72, 73]. Furthermore, glutathione S-transferase P1 (GSTP1) detoxicates lipid ROS by catalyzing 4-HNE-GSH conjugation independent from GPX4/FSP1 acting as an unconventional ferroptosis regulator [74]. Excessive iron was shown to accumulate in mitochondria, causing mitochondrial dysfunction in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via ferroptosis [75]. Administration of an iron chelator such as deferoxamine or a ferroptosis inhibitor such as ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) can reduce the amount of available iron, attenuating lipid peroxidation and eventually ferroptosis [75].

Changes in extracellular pH can also trigger ferroptosis. Namely, G protein-coupled receptor 4 (GPR4), an acid-sensing receptor, is implicated in neuronal ferroptosis in early brain injury. Administration of a GPR4 antagonist reduces 4-HNE formation, mitochondrial damage, and neuronal ferroptosis achieved through the Ras homolog family member A/Yes-associated Protein pathway [76]. Furthermore, elevated intracellular pH decreases ALDH2 activity and inhibits the Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase/cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein 1/GPX4 axis, preventing its role in inhibiting ferroptosis via 4-HNE detoxification [77]. In addition, 4-HNE reduces GPX4 expression and modifies GPX4 function by its carbonylation [78]. A schematic presentation of the roles of 4-HNE in ferroptosis is presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. The involvement of 4-HNE in ferroptosis and autophagy. Excessive ROS promotes peroxidation of membrane-bound PUFAs, triggering a chain reaction of lipid peroxidation and formation of lipid ROS and eventually 4-HNE. GPX4 has a major role in lipid ROS detoxification. Inhibition of the cystine/glutamate antiporter Xc– system deprives cellular cysteine, affecting GSH biosynthesis that consequentially impacts GPX4 activity, resulting in elevated lipid ROS. Intracellular labile iron accumulation further promotes the accumulation of lipid ROS, eventually resulting in ferroptotic cell death. Alternatively, 4-HNE can inhibit autophagy by inhibiting AMPK activity but also promote autophagy via a modified JNK pathway. Moreover, 4-HNE was shown to activate the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway to trigger light chain 3 (LC3) formation and induce endoplasmic reticulum stress, all of which promote autophagy. The figures are drawn in PowerPoint (Microsoft Office 2019, Redmond, WA, USA). Abbreviations: 4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; GSH, glutathione; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; Xc–, the cystine/glutamate antiporter system.

NADPH-oxidase 4 activation was found to promote ferroptosis by impacting myeloperoxidase and osteopontin, causing mitochondrial dysfunction and excessive 4-HNE formation in astrocytes, which ultimately promotes ferroptosis [79]. On the other hand, the release of corticosteroids increased under stress induces activation of the protein kinase C pathway, which facilitates 15-lipoxygenase-1 localization in the vicinity of plasma membranes and promotes lipid peroxidation triggering ferroptosis in dopaminergic neurons [80].

A transmembrane glycoprotein, fibronectin type III domain containing 5 (FNDC5) has cardioprotective effects. When cells are exposed to oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL), the expression of FNDC5 and the expression of antioxidants are reduced, while it promotes the release of inflammatory cytokines, lipid peroxidation, and the formation of 4-HNE, ultimately leading to ferroptosis [81]. A recent study identified the important role of adipose tissue-derived protein asprosin in ferroptosis. Through integrin

Therefore, it is evident that 4-HNE is not only the hallmark of ferroptosis but also a critical factor of ferroptosis in various diseases. Accordingly, a better understanding of the roles 4-HNE has in ferroptotic cell death in different diseases may provide novel potential therapeutic options targeting the pathways that regulate 4-HNE formation, lipid peroxidation, and iron homeostasis.

Autophagy is a strictly regulated process in which cells degrade cellular components such as proteins and organelles. While stress-induced autophagy can promote cell survival, it is also an essential process alongside other mechanisms of regulated cell death or autophagy-dependent cell death [34]. Key proteins in autophagy include microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) and autophagy-related proteins (ATG), which orchestrate the formation and elongation of the phagophore and, finally, the formation of a mature autophagosome that, following the fusion with the lysosome, forms an autolysosome [84].

Autophagy is closely linked to the physiological response to oxidative stress. Intracellular accumulation of 4-HNE promotes the activation of kinases, including p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, JNK, and protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase. It also increases the expression of heme oxygenase-1 and LC3-II formation, enabling cell survival, while inhibition of JNK may ameliorate these effects, resulting in cell death [85]. The protective effect of autophagy was also observed in retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, where ethanol exposure damaged mitochondria and caused accumulation of 4-HNE, while autophagy was activated as a defense mechanism of degradation of impacted mitochondria and 4-HNE aggresomes [86]. On the other hand, dysfunctional autophagic machinery promotes the accumulation of oxidized proteins, protein aggregates, damaged lipids, and damaged organelles, thus promoting diseases such as Down syndrome, and age-related macular degeneration [87, 88]. The p62, a selective autophagy receptor [89] is another target of 4-HNE. Exposure to 4-HNE upregulates the p62 expression, promoting autophagy of damaged macromolecules and organelles [90, 91].

Dysregulated autophagy can also have deleterious effects. Depending on the concentration, 4-HNE exhibits a dual effect on autophagy. 4-HNE can inhibit autophagy via inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity but may also promote autophagy via a modified JNK pathway [85, 92]. Additionally, 4-HNE can activate the mTOR pathway [93], induce endoplasmic reticulum stress [85] and trigger LC3 formation [94] promoting autophagy.

Moreover, 4-HNE was shown to activate the mTOR pathway, to trigger LC3 formation, and to induce endoplasmic reticulum stress, all of which promote autophagy. Furthermore, low concentrations of 4-HNE have been shown to promote autophagy in neuronal cells, while at higher concentrations, 4-HNE causes mitochondrial dysfunction and inhibits autophagy, leading to cellular dysfunction [95]. The altered metabolism of cells, such as the inhibition of glycolysis in neuroblastoma cells, can enhance cellular sensitivity to 4-HNE by attenuating autophagy while enhancing apoptosis, highlighting an important role of glucose metabolism in the regulation of autophagy activated by 4-HNE [96]. In the recent review, the current evidence on the involvement of 4-HNE from the initiation of autophagy and the formation of phagophores to the final degradation stage of autophagy has been summarized [97].

The findings regarding the role of 4-HNE in autophagy may represent the basis for the development of innovative strategies to either enhance protective autophagy or prevent its dysfunction and thus offer promising avenues for treating a wide range of diseases, particularly diseases associated with oxidative stress and autophagic dysfunction.

Inflammatory cell death, known as pyroptosis, is characterized by inflammasome-dependent caspase-1 activity [98]. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) is an example of an intracellular sensor that can trigger pyroptosis and attract the apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC), yielding inflammasome formation. This promotes caspase-1 activation, which cleaves gasdermin D (GSDMD). It was recently found that degradation of Xc– via the ubiquitin-proteasome system promotes lipid peroxidation, as evidenced by increased 4-HNE production, which in turn leads to gasdermin D-mediated pyroptosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [99]. Similarly, pyroptosis may be induced by cytosolic lipopolysaccharide, which activates caspase-4/5/11, leading to GSDMD cleavage. Released gasdermin-N then promotes plasma membrane pore formation, leading to ion fluxes, cell swelling, the release of inflammatory mediators, and, ultimately, the lysis of the cell [100].

The ox-LDL-induced activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is important for the onset and progression of atherosclerosis. Namely, ox-LDL alters cellular redox homeostasis, promotes the formation of 4-HNE, reduces ALDH2 activity, activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, and may cause DNA damage, leading to pyroptosis as observed in RAW264.7 cells. One of ALDH2’s primary substrates is 4-HNE, and the reduced enzyme activity could be at least partially due to ox-LDL-induced 4-HNE. Hence, the cells were partially rescued from pyroptosis and excessive 4-HNE by administration of the ALDH2 activator Alda-1 [101]. The protective role of ALDH2 by inhibiting pyroptosis has also been documented in cardiac injury induced by high glucose, which could be attributed at least in part to NLRP3 inflammasome action, excessive mitochondrial ROS production, and lipid peroxidation. Overexpression of ALDH2 in H9C2 cardiac cells exposed to high glucose inhibited mitochondrial ROS production, decreased 4-HNE levels, and decreased key components of pyroptosis, such as caspase-1 activity, NLRP3 inflammasome-related proteins, and ASC, thereby inhibiting pyroptosis [102]. In addition, increased levels of 4-HNE, NLRP3, and gasdermin are induced in the heart and the brain after ischemia/reperfusion injury, while Alda-1 ameliorated oxidative stress, 4-HNE formation, and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, resulting in the inhibition of pyroptosis and improved recovery of the heart and brain in pigs after eight minutes of untreated ventricular fibrillation [103]. The interaction between mitochondrial ALDH2, ferroptosis, and pyroptosis has also been evidenced in the murine sepsis-induced lung injury model. Namely lung injury was accompanied by excessive ROS, elevated levels of 4-HNE-modified proteins, increased prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2, and decreased GPX4, while administration of Alda1, Fer-1, and the NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 alleviated those effects [104]. On the other hand, in the mouse models of acute lung injury and sepsis, 4-HNE attenuated the NLRP3 inflammasome, acting even as an endogenous inhibitor of pyroptosis [105].

In a mouse model of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, caspase-1 activity, level of 4-HNE, and the expression of GSDMD mRNA are increased [106]. Interestingly, the ferroptosis inhibitor liproxstatin-1 alleviated these alterations. In addition, liproxstatin-1 also inhibited apoptosis and necroptosis, suggesting its novel role as an inhibitor of PANoptosis, a type of cell death that involves an interplay of pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis, sharing their characteristics [107]. This process is regulated by a large protein complex called the PANoptosome, which is made up of sensors, adaptors, and catalytic effectors [108]. A recent study demonstrated that hypoxia-induced cell death involves crosstalk between ferroptosis and PANoptosis and that both processes can be mitigated with the scavenger of lipid peroxidation [109].

Therefore, understanding the intricate interplay between oxidative stress, 4-HNE, inflammasome activation, and pyroptosis is of high relevance for developing targeted therapies to manage diseases linked to pyroptosis and PANoptosis.

The activation of death receptors like TNF-R1 or pathogen recognition receptors like toll-like receptor 4 triggers a regulated form of cell death with a necrotic phenotype known as necroptosis [34, 110]. Necroptosis requires activation of both mixed lineage kinase domain like pseudokinase (MLKL) and receptor interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1)-induced RIPK3 activation [34]. Recent studies have observed the involvement of lipid peroxidation in necroptosis, too. Hence, linoleic acid and

The involvement of oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in parthanatos has not been extensively explored. Hyperactivation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) drives the parthanatos mechanism of programmed cell death [34], while one of the factors that triggers PARP1 activation is oxidative stress-induced DNA damage. Namely, a recent study showed a positive correlation of oxidative stress parameters, including 4-HNE, with PARP1 activation and parthanatos in human leukocytes derived from chronic heart failure patients [116].

In the last few years, two new forms of programmed cell death closely associated with oxidative stress were discovered and termed oxeiptosis and cuproptosis [117, 118]. Oxeiptosis is a form of cell death triggered by ROS that resembles apoptosis but is independent of caspases [118]. Oxeiptosis is mediated through the interaction of Keap1, mitochondrial serine-threonine phosphatase phosphoglycerate mutase 5 (PGAM5), and apoptosis inducing factor mitochondria associated 1 (AIFM1). The Keap1 and Nrf2 complex is normally attached to mitochondria via PGAM5 [119], while under mitochondrial stress, PGAM5 dissociates from Nrf2, inducing the translocation of Nrf2 to the nucleus and the expression of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response [120]. At high levels of oxidative stress, PGAM5 dissociates from Keap1 and interacts with AIFM1, ultimately resulting in oxeiptotic, non-inflammatory cell death. Although the direct role of 4-HNE in oxeiptosis has not been extensively studied, 4-HNE may influence oxeiptosis, though further research is needed to confirm this potential interaction.

Cuproptosis depends on copper imbalance and mitochondrial respiration. Excessive copper targets lipoylated components of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, which results in protein aggregation, proteo-toxic stress, and cell death [117]. Moreover, excessive copper, acting as a transition metal resembling iron, induces ROS production, reduces antioxidant defenses, and promotes lipid peroxidation [121]. Although 4-HNE and copper induce oxidative stress and peroxidation of lipids, which further generates 4-HNE, the direct involvement of 4-HNE in cuproptosis is not well-established. Thus, further research is needed to determine whether 4-HNE interacts with copper-induced cell death mechanisms.

Because 4-HNE has a strong affinity for binding to the proteins, its regulatory as well as toxic effects depend on the function of the proteins modified by 4-HNE and their overall intracellular concentration [2, 11, 122, 123, 124, 125]. Generally speaking, relatively low levels of 4-HNE are regulatory; higher levels induce cellular decay, while very high levels can induce rapid cell death caused by an irreversible process of autolysis known as necrosis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

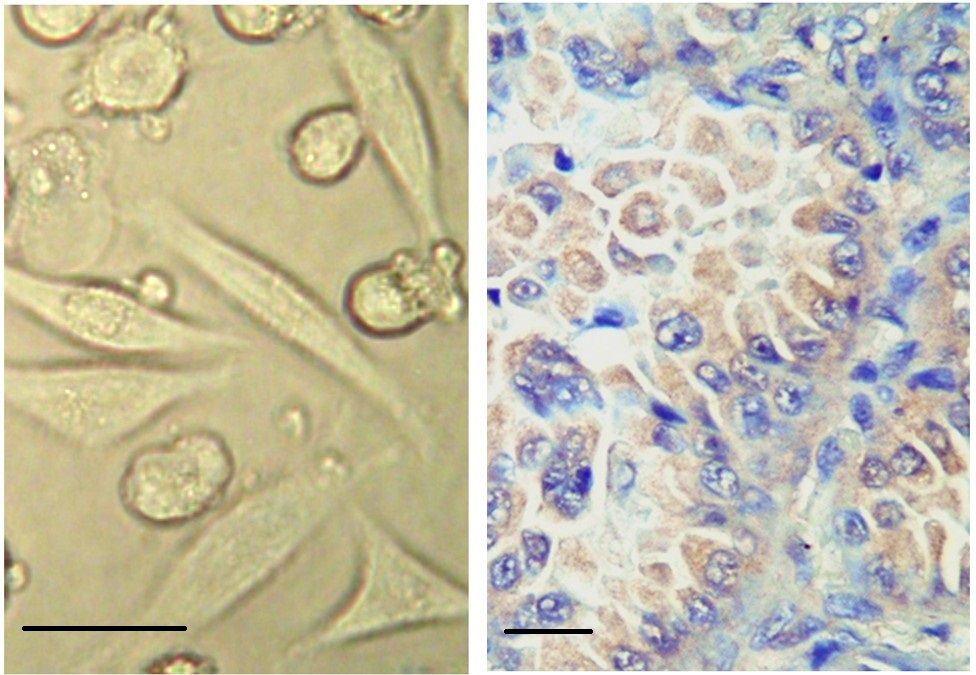

Fig. 5. Necrosis induced by 4-HNE. 4-HNE added at 100 µM to human carcinoma cells (HeLa; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) in vitro induces necrosis in some cells in less than five minutes, which is associated with the shrinking of the cells into a rounded, pyknotic shape associated with lipid peroxidation of the cellular membrane manifested by blebbing (left photo, no staining, magnification 650

Necrosis is an unspecific, uncontrolled, and irreversible process of cellular death, usually developing after acute and severe damage followed by the rapid degradation of the cells and the release of the cellular contents in the affected tissue, thus spreading the damage and the death of the cells [126]. The involvement of lipid peroxidation as a crucial pathogenic factor of liver necrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4), was known more than fifty years ago [127]. However, at that time, 4-HNE was not known to be an important factor of liver necrosis, as was found afterward to be even in the case of liver inflammation, i.e., hepatitis, and damage of other organs caused by various diseases [128].

Induction of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and necrosis by 4-HNE also depends on the type of cells, among which cancer cells are more sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of 4-HNE than are non-malignant normal cells [129, 130, 131]. The sensitivity of the cells to 4-HNE also depends on the level of differentiation, suggesting that reduced proliferation of cancer cells associated with induced differentiation also increases the sensitivity of cancer cells to the pro-apoptotic and necrotic effects of 4-HNE [132]. However, in case of extremely intense production of 4-HNE and accumulation of its protein adducts, as in the case of COVID-19, 4-HNE can induce local and systemic, unselective ferroptosis and necrosis of normal cells, thus having lethal consequences for the entire organism [133, 134, 135].

Taking together the complex regulatory and cytotoxic effects of 4-HNE in vitro and in vivo, we can conclude that oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and thus generated 4-HNE have fundamental roles in the death of cells included by different pathways under different pathophysiological and pathological processes. Due to the presence of 4-HNE-modified proteins even after the end of oxidative stress or even in the absence of manifested lipid peroxidation, we can assume that 4-HNE can cause not only acute but also chronic consequences associated with the decay of cells and the entire organism. However, accumulation of the 4-HNE-modified proteins can be reversible in vital cells, if not associated with necrosis, while 4-HNE targets mostly aged and malignant cells. Therefore, options for targeted cytotoxic effects of 4-HNE might be an interesting option for future treatments of degenerative and malignant processes.

4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; AIFM1, apoptosis inducing factor mitochondria associated 1; Akt, protein kinase B; Alda-1, ALDH2 agonist; ALDH2, aldehyde dehydrogenase 2; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; AP-1, activator protein 1; Apaf1, apoptotic protease activating factor 1; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD; ASK1, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; ATG, autophagy-related proteins; Bad, Bcl-2-associated death promoter; Bak, Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer; Bax, Bcl-2-associated X protein; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; cyt-c, cytochrome c; Daxx, death domain-associated protein; DISC, death signaling complex; FADD, FAS-associated death domain protein; FasL, Fas ligand; FasR, Fas receptor; Fer-1, ferrostatin-1; FNDC5, Fibronectin Type III Domain Containing 5; FSP1, ferroptosis suppressor protein 1; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; GSDMD, gasdermin D; GSH, glutathione; GSTP1, glutathione S-transferase P1; HSF1, heat shock factor 1; HSP, heat shock proteins; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; Keap1, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; LC3, light chain 3; MLKL, mixed lineage kinase domain like pseudokinase; MOMP, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NLRP3, nucleotide binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3; Nrf2, nuclear factor, erythroid 2 like 2; ox-LDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; p21, Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A; p53, tumor protein 53; PARP1, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1; PGAM5, phosphoglycerate mutase 5; PUFA, poly unsaturated fatty acids; RIPK1, receptor interacting protein kinase-1; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RPE, retinal pigment epithelial cells; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNF-R1, TNF-receptor 1; TRAIL, TNF-related inducing apoptotic ligand; Xc–, the cystine/glutamate antiporter system; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein.

Conceptualization, NZ; ND, acquisition of references; writing—original draft preparation, MJ, ASM, ND and NZ; writing—review and editing, MJ, ASM and NZ; visualization, MJ and ASM; supervision, NZ and MJ. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript and its revision.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Neven Zarkovic is serving as the Guest Editor and Editorial Board member of this journal. We declare that Neven Zarkovic was not involved in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Guohui Sun.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.