1 Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, 117997 Moscow, Russia

2 Laboratory of Tick-Borne Encephalitis and Other Viral Encephalitides, Chumakov Federal Scientific Center for Research and Development of Immune-and-Biological Products, 108819 Moscow, Russia

3 Vavilov Institute of General Genetics, 119991 Moscow, Russia

4 Department of Biomedicine to Department of Biomedical Sciences, School of Medicine, Nazarbayev University, 02000 Astana, Kazakhstan

Abstract

The tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a fundamental role in tumor progression. Cancer cells interact with their surroundings to establish a supportive niche through structural changes and paracrine signaling. Cells around transformed tumor cells contribute to cancer development, while infiltrating immune cells in this aggressive TME often become exhausted. Solid tumors, especially the most invasive types such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, are notably stiff mechanically, with cross-linking enzymes significantly affecting the survival of cancer cells in both primary tumors and metastatic sites. In this review, we highlight recent key contributions to the field, focusing on single-cell sequencing of stromal cells, which are increasingly seen as highly heterogeneous yet classifiable into distinct subtypes. These new insights enable the development of effective co-treatment approaches that could significantly enhance current and novel therapies against the most aggressive cancers.

Keywords

- cancer

- desmoplasia

- extracellular matrix

- metastasis

- cancer-associated cells

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is defined as the sum of acellular components (extracellular matrix (ECM) plus fluids), and various cells in contact with surrounding blood and lymph vessels. TME is heterogeneous to such a high extent that may be viewed upon as a disordered mass. The cells and ECM are continuously undergoing remodeling, and the cells communicate with each other through direct contacts, paracrine and autocrine secreted factors. In such communications, extracellular vesicles (EVs) carrying various cargos are recognized as extremely important for tumor progression and dissemination. There is ongoing debate about the role of inflammation, particularly regarding the eicosanoid axis involving prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which is under intense scrutiny.

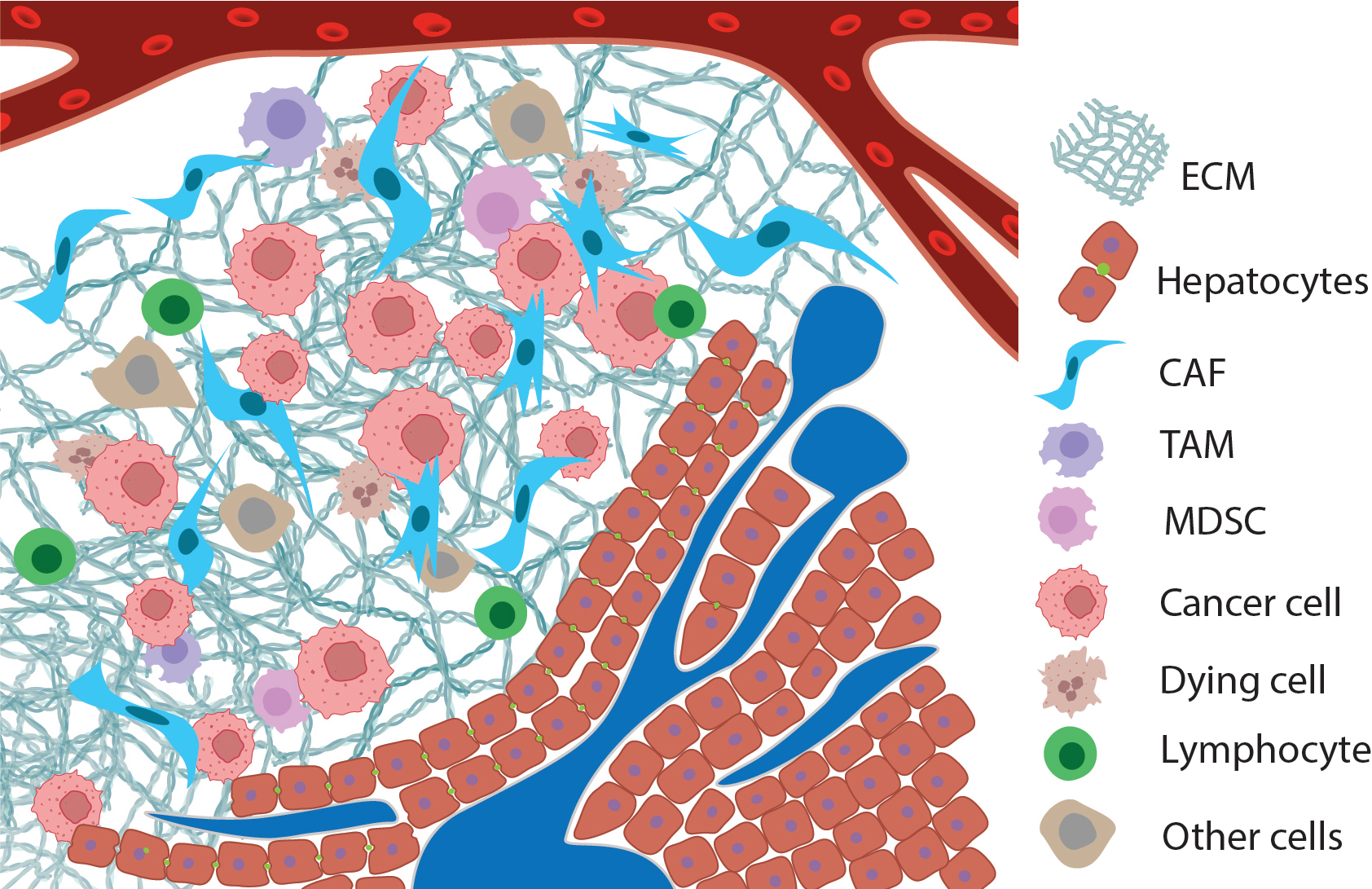

Not only are the cancer cells proper (transformed cells) heterogeneous. The cells that surround them (frequently called stromal cells) are even more diverse, they differ in properties and their origins; they may be resident cells or cells that have migrated from other organs. These cells include–to name the most frequently used types: cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), dendritic cells (DCs), regulatory T cells (Tregs), cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), natural killer (NK) cells, tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), B cells (including plasma cells), mast cells, and others (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Ideogram of the tumor microenvironment: metastasis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma to the liver. Normal tissue with ducts is depicted in the lower-right corner, with a blood vessel at the top. The tumor includes not only transformed cells (pink) but also a large number of tumor-associated fibroblasts (spindle-shaped blue cells), tumor-associated macrophages, lymphocytes mainly at the periphery (green cells), dying cells (brown with segmented nuclei), and others, along with a dense extracellular matrix, shown as tangled triple spirals of collagen. Created with Adobe Illustrator (version 29.5, Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). ECM, extracellular matrix; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell.

Some of these cells are immunosuppressive, while others attempt to combat the tumor but may become exhausted, for example, through TGF-

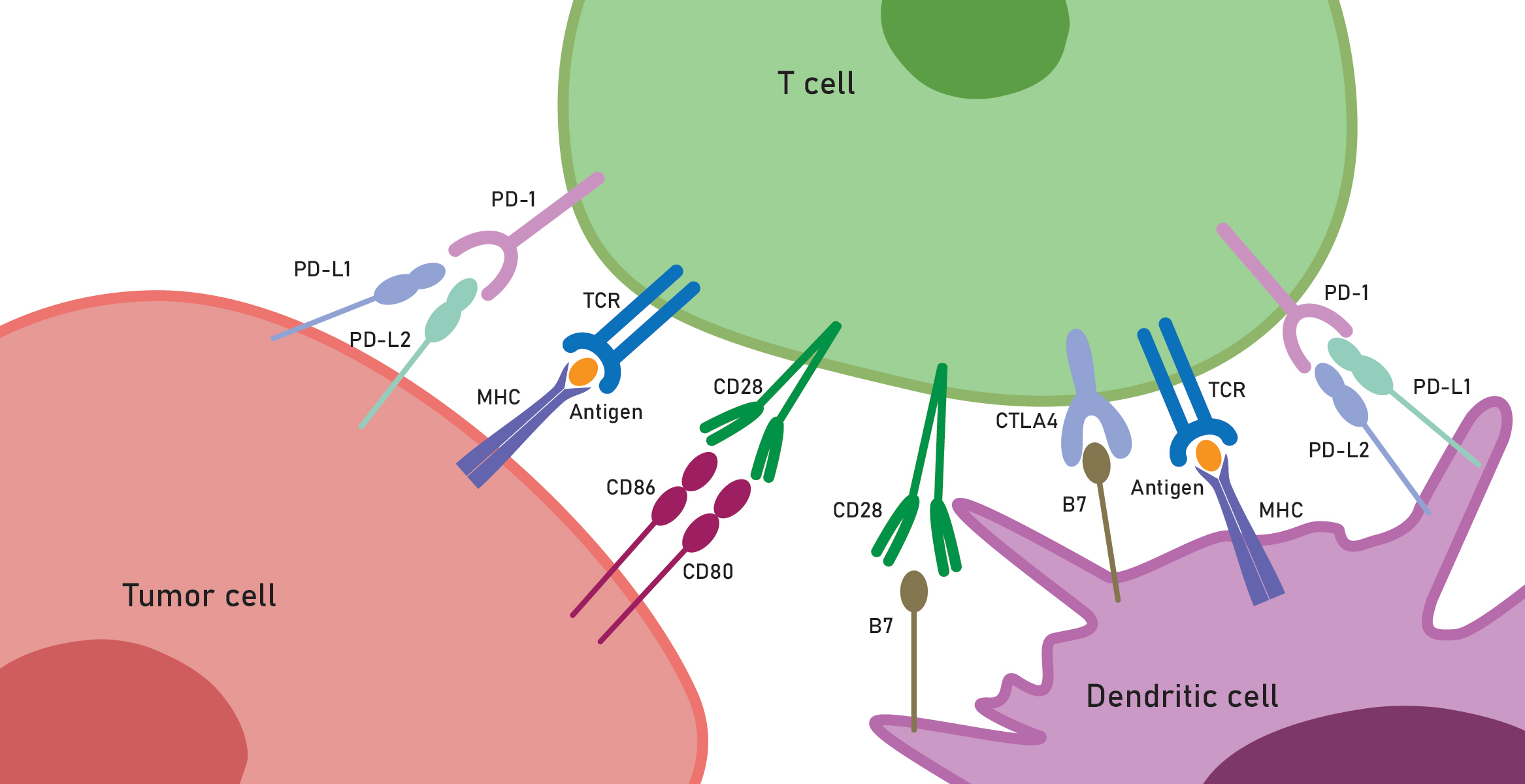

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Key receptor interactions in the tumor microenvironment. Figure highlights tumor cells, cytotoxic cells, and dendritic cells, where immune checkpoint mechanisms enable tumors to evade destruction by cytotoxic cells and, vice versa, to develop effective strategies for ICB therapies. Created with Adobe Illustrator (Adobe Systems). B7, B7 family ligands; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4; CD28,80,86, cluster of differentiation 28,80,86; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; TCR, T cell receptor; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1,2, programmed cell death ligand 1,2.

Here, we aim to review the most recent and important discoveries in the field of TME features, focusing on different functions such as the re-education of normal cells, immune evasion, immune cell exhaustion, and drug resistance. The major message of this review is that the cells surrounding tumor cells are not mere bystanders in cancer. Classically, higher densities of CD8+ T cells, conventional dendritic cells type 1 (cDC1), and natural killer (NK) cells indicate a better anti-tumor response and improved survival. But how can we move further from these paradigms? We also include novel fields of research that previously lacked attention, such as the issue of the intratumor microbiota, which usually aggravates the disease but in some cases may provide significant advantages.

The ECM can form a barrier that impedes T cell infiltration into tumors. ECM stiffness is enhanced by the cross-linking of ECM proteins by protein-protein cross-linking enzymes such as lysyl oxidase (LOX) and lysyl hydroxylase (procollagen-lysine,2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase, PLOD). The latter enzyme’s action helps to form more stable cross-links, thus it not surprising that PLODs contribute significantly to stiffness of ECM in TME. The heterogeneous TME and ECM stiffening affect intratumoral T cell migration, it has been shown that inhibition of LOX reduces the number of protein cross-links within the ECM, thereby decreasing its stiffness, thus tumor stiffness in vivo positively correlates with tumor growth and negatively correlates with T cell tumor infiltration [2]. High expression levels of PLOD family genes are associated with poorer disease-free survival and distant metastasis-free survival. Indeed, elevated levels of PLOD1 and PLOD3 are linked to worse overall survival in patients with breast cancer [3], and in cervical cancer the role of PLOD2 appears to be especially pronounced [4]. Collagen type IV is usually believed to be the preferred substrate for PLOD enzymes, however, other collagens are also important, for example, in prostate cancer, it has been shown that a collagen VI-rich microenvironment reduces the motility of T cells, leading to their entrapment within the stroma [5]. Recent discoveries indicate that collagen I promotes oncogenic signaling and cancer cell proliferation, moreover, the deletion of collagen I homotrimers has been found to enhance T cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment and improve the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy [6].

Regarding colorectal cancer, the role of ECM stiffness has been explored in detail. It is proposed that increased ECM stiffness primarily affects tumors by physically restraining immune cells within the dense matrix. This mechanical barrier is a major reason why a stiff ECM enables tumors to escape immune surveillance [7]. Thus, ECM aging—which can lead to increased stiffness—is an important factor in TME.

Not only mechanic properties but continuous remodeling of ECM proteins, especially collagens, plays a significant role in TME. For example, for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), it has been shown that both matrix metalloprotease-cleaved collagen I (cCol I) and intact collagen I (iCol I) activate the discoidin domain receptor 1 (DDR1)-NF-

Importantly, ECM stiffness greatly influences the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of cancer cells, and for this process, particularly important molecules include integrins, selectins, and cadherins, etc. The functional role of vimentin—a key intermediate filament protein associated with EMT—has been examined in detail, and it was found that topographical patterning of such proteins influences EMT [12], thus it is clear that physical properties of TME govern many properties of cancer cells including their motility. Vice versa, EMT induces changes in the mechanics and composition of the ECM, creating a feedback loop that perpetuates these processes [13]. Since EMT is tightly regulated by a complex network orchestrated by various intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including multiple transcription factors, post-translational modifications, epigenetic changes, and noncoding RNA-mediated regulation [14], any increase in ECM stiffness can impact cellular signaling pathways through mechanotransduction, promoting carcinoma cells to undergo EMT. This suggests that mechanical forces, being dependent on the ECM structure, play a critical role in tumor invasion and metastasis [15].

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are cells of different origins (thus CAFs is a collective term), moreover, transition of normal cells into CAFs, i.e., cells programed (educated) by tumor cells into CAFs, usually continues throughout tumor growth and dissemination: even stellate cells and pericytes can be transformed into CAFs. CAFs can be either resting or activated, with distinct morphologies and marker expressions. Activated fibroblasts express

It is not surprising that CAFs are heterogeneous, and this is proved by recent breakthroughs in understanding the role of CAFs obtained from single-cell sequencing (SCS) data. Pan-cancer SCS indicate that CAFs have distinct origins (including not only normal fibroblasts but also endothelial cells, peripheral nerves, and macrophages) and may be classified into three subtypes correlating with prognosis [18]. For example, in chordoma, it has been shown that a subset of inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs) correlates strongly with tumor aggressiveness and impacts patient morbidity and mortality [19]. In bladder cancer, a unique CAF signature (PDGFR

Recently, SCS revealed that in PDAC there are more than three distinct types of CAFs: myofibroblasts (myCAFs), inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs), and others such as POSTN-CAFs, and antigen-presenting CAFs (apCAFs). Among these, myCAFs are especially important for PDAC progression, possibly due to their physical proximity to the PDAC cells. In contrast, iCAFs, marked by PDPN and COL14A1, are more distant and may share SASP characteristics with senescent CAFs. MyCAFs are classically characterized by TGF-

In various skin cancers, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma, previously unrecognized CAF types have been identified: myofibroblast-like RGS5+ CAFs, matrix CAFs, and immunomodulatory CAFs. The matrix CAFs actively produce novel ECM and restrict T cell invasion in low-grade tumors through a mechanical barrier, whereas high-grade tumors have abundant immunomodulatory CAFs that actively secrete various cytokines and chemokines [34].

In GBM, immature CAFs evolve into distinct subtypes, with mature CAFs expressing ACTA2. These CAFs are in contact with mesenchymal glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs), endothelial cells, and M2 macrophages, and are involved in PDGF and TGF-

In clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), SCS uncovered the spatial relatedness of mesenchymal-like ccRCC cells and myCAFs at the tumor-NAT interface. Also, a high presence of myCAFs was linked to primary resistance to ICB therapy [36].

For colorectal cancer, SCS allowed stratification of samples into three subtypes with different distribution of cancer cell supporting SFRP2+ CAFs [37].

In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), CAFs deposit collagen fibers at tumor boundaries, creating a barrier that prevents T cells from entering TME. SCS revelead a novel CAF group called antigen-presenting CAFs (apCAFs) [38]. Recently, another study on primary human NSCLC identified at least five CAF types, including a new type, CAF-S5 [39]. This previously undescribed population is FAP+ and PDPN+, but

Interleukins play a decisive role in communication between CAFs and other cells, as some interleukins may also induce senescence in iCAFs. Senescent iCAFs can make tumors more resistant to therapies, so inhibiting them could increase tumor sensitivity to treatments, at least in colorectal cancer [41]. To add complexity, CAFs use various cytokines to communicate with cancer cells and other cells of TME, for example, in HCC, a study showed that the IL-6-IGF-1 axis is crucial for communication between HCC and CAFs [42]. A novel regulatory axis was found in gastric cancer where IL-8 from CAFs, under the control of serglycin secreted by tumor cells, plays a significant role in these cell-cell communications [43]. Highly metastatic cancer cells mobilize periostin-expressing CAFs at the primary tumor site—such CAFs promote collagen remodeling and facilitate collective cell invasion into lymphatic vessels and nodes [44].

Recent discoveries pose the major question: how can interactions between CAFs and cancer cells be disrupted? Recently, the small molecule ketotifen was found to reduce the contractile activity of TGF-

At least in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, SCS allowed dissection of CAFs in two major subtypes, myCAFs (without notable LOX expression) and LOX + iCAFs, and the latter subtype was noted to be actively supporting cancer cell proliferation and migration [46], also indicating that cross-linking enzymes secreted from cancer-associated cells may be more important than those produced in the so called cancer cell autonomous manner.

CAFs affect monocytes and tissue-resident macrophages through signals like SDF-1, MCP-1, and CXCL12/14 to promote their differentiation into tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). CAFs and TAMs engage in reciprocal communication with tumor cells within TME [47]. The classical understanding of the inactivity of TAMs (phagocytes with cancer cell killing capability) is that cancer cells evade macrophage attack by overexpressing anti-phagocytic surface proteins, known as “don’t eat me” signals, such as CD47, PD-L1, and the

Traditionally, the usual M1 and M2 classification of TAM is still employed, where M1 is the pro-inflammatory phenotype, that produces NO, whereas M2 is immunosuppressive, producing arginase among other cues supporting tumor persistence and growth. This distinction is now recognized as overly simplistic [51], but remains quite useful for identifying new important molecular markers. In contrast, this binary paradigm may not be necessarily aligned with traditional views on particular molecular players, for example, CD206, once considered a marker of immunosuppressive TAMs, actually shows a more complex relationship with immune suppression, since CD206+ TAMs have been found to correlate with better immune responses and improved survival [52]. Integrins

In breast cancer, TAMs form a network throughout the tumor, similar to resident macrophages of the normal breast [55]. There, TAMs are mostly M2, they have specific mechanisms of polarization, markers, and functions. Also, macrophages specifically expressing CD68 may be typical for TAMs in breast cancer [56]. The major pro-cancer functions of TAMs include producing TGF-

TAMs promote primary tumors and metastasis by suppressing tumor immune surveillance, but the metabolic requirements for this were largely unknown. It turns out that long-chain fatty acid metabolism, particularly with unsaturated fatty acids like oleic acid, leads to the formation of lipid droplets. This process can inhibit the in vitro polarization of TAMs and reduce tumor growth in vivo. In human colon cancer, myeloid cells have been found to accumulate lipid droplets [59]. Using SCS, diverse subsets of macrophages with links to lipid metabolism were observed in the mice bearing orthotopic mammary tumors. Among seven distinct macrophage clusters identified, one demonstrated a profile consistent with lipid-associated macrophages (expressing LGALS3 and TREM2) and exhibited a reduced capacity for phagocytosis [60]. Also, it has been proposed recently that active TAMs in breast cancer enhance stiffness by collagen synthesis, and also negatively affect CD8+ cells by depletion of arginine, and secretion of ornithine [61].

In bladder cancer TAMs promote BC cell migration and invasion, and this can be elegantly modeled by co-culturing bladder cancer cell lines with THP-1 cells, where the latter show M2-like features (e.g., a decrease in CD68 and an increase in CD206 expression) under this influence [62].

The significance of tissue-resident, embryonically derived macrophages has increasingly been recognized in recent years. Resident TAMs may prime the premetastatic niches to enable the growth of metastases and then support secondary tumor growth [63]. In gastric cancer, a proliferative cell lineage known as C1QC+MKI67+ TAMs has been identified, exhibiting high immunosuppressive capabilities [64].

Concerning pro-cancer activities of TAMs, novel regulatory pathways continue to be discovered. For example, a new axis involving THBS2-positive myCAFs (THBS2+ mCAFs) has been found to facilitate the recruitment and conversion of peritoneum-specific tissue-resident macrophages into SPP1-positive tumor-associated macrophages (SPP1+ TAMs). This process leads to the formation of a protumoral stroma-myeloid niche in the peritoneum [65].

A recent discovery found that sepsis survivors have a lower cumulative incidence of cancer, attributed to sepsis-trained resident macrophages. These macrophages promote tissue residency of T cells via CCR2 and CXCR6. The accumulation of CXCR6 tissue-resident T cells in humans with history of sepsis has been associated with prolonged survival in cancer patients [66].

Some researchers propose that TAMs hold greater promise than T cells in cancer therapies, since TAMs and other myeloid-origin cells extensively infiltrate tumors, unfortunately usually in immunosuppressive states. It has been shown that IgM-induced signaling in murine TAMs leads to the secretion of lytic granules, promoting tumor cell death. Additionally, the incorporation of chimeric receptors featuring high-affinity Fc

Dendritic cells (DC), the most important among the professional antigen-presenting cells, play a huge role both in suppressing tumors and supporting those that evade the immune system. Two main types are found in tumors: previously known as myeloid DCs, now referred to as cDCs (CD141+, CD1c+). These are further divided into cDC-1 cells, which activate cytotoxic lymphocytes, and cDC-2, which support T-helper cells. The second type, plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), marked as CD303+, actively produce IFN-

The paradigm “no effector T cell without dendritic cell” underscores the essential role of DCs in initiating T cell responses [69]. The presentation of antigens—including cancer neoantigens—and the impact of cancer cell heterogeneity in real tumors on these processes remain matters of debate. The multiplicity of neoantigens—their diverse varieties and numbers—is so vast that T cells may struggle to prioritize which antigens are most important to target [70], thus the role of DCs in tumors is immense, for example, therapeutic RNA-based vaccination that targets immune-suppressed T-cell responses has been shown to synergize with ICB, enabling control of tumors with subclonal neoantigen expression [71]. On one hand, DCs have anti-tumor functions: they produce chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10, which attract cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and Th1 cells—with BATF3 expression—to the tumors. On the other hand, certain dendritic cell subsets can recruit regulatory T cells (Tregs), thereby promoting tumorigenesis. Tumor cells can also reprogram DCs through tumor-derived factors and metabolites [72].

Breast cancer immunosurveillance requires the involvement of cDC1, natural killer (NK) and NKT cells (natural killer T cells), conventional CD4+ T helper cells, and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), where cDC1s are essential for T-cell priming. Within tumors, cDC1 interact with CD4+ T cells and tumor-specific CTLs to initiate effective immune responses. Both cDC1 and interferons are necessary for anti-tumor activity, mediated through cDC1 signaling via IFN-

In vitro experimentation with cultured DCs presents significant challenges, particularly concerning the timing of DC maturation. The temporal aspect of maturation is vital, especially at the critical point when DCs interact with responding T cells or after CD40-Ligand restimulation. Unexpectedly, prolonged maturation periods may lead to overstimulation of DCs, whereas shorter maturation times might be more advantageous [75]. It is important that cDC2s are abundant in tumors. In three-dimensional (3D) DC-tumor co-cultures, ECM, including collagen, plays an important role in supporting DC function and tumor interaction. Additionally, the participation and interaction of PGE2 and IL-6 are significant in this context [76] .

One of the most important recent findings is the observation of functional diversity among DCs in TME. For example, at least one population of CCR7-positive (CCR7+) DCs migrates to the tumor-draining lymph nodes (dLNs), while another CCR7+ subset remains resident within the tumor tissue. These tumor-resident CCR7+ DCs differ from those that migrate to the dLNs. Notably, the tumor-retained DCs perform poorly in antigen presentation and maintain contact with PD-1+ CD8+ T cells. As a result, these tumor-resident DCs appear exhausted [77].

In the past, there were great hopes for simple manipulations using cancer cell lysates and DCs to better present cancer neoepitopes from DCs to T cells. However, this approach now appears to be a dead end [78], perhaps due to the fact that the presence of neoantigens do not guarantee T cell infiltration [79].

Lymphocytes, including CD8+ cytotoxic and CD4+ helper lymphocytes, are key components of adaptive immunity and are crucial for targeting malignant cells expressing neoantigens. Also, cancer vaccines primarily rely on these lymphocytes. However, “cold” tumors evade detection by reducing HLA expression, while “hot” tumors focus on ICB and inducing immune exhaustion. The role of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in tumorigenesis, coupled to inflammation, and control of tumor growth and dissemination is immense, unfortunately, mechanisms of evading their cytotoxic actions may be diverse, not limited to HLA repression, for example, PDAC with mutated KRAS epigenetically silence promoter of FAS death receptor gene [80, 81].

The heterogeneity of TILs is now studied using novel in-depth methods such as SCS. For example, in HCC, SCS indicated that abundant non-exhausted CD4+ T cells correlate with a better prognosis, including increased sensitivity to immunotherapy. In contrast, an immune “desert” phenotype was associated with the worst survival outcomes, mechanistically linked to spindle assembly abnormal protein 6 homolog (SASS6) as a new therapeutic target [82]. In a murine model of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs), SCS revealed important differences in the T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire of CD8+ TILs and the various TCR clonotypes, indicating that antitumor immune responses are highly individualized, with different hosts employing different TCR specificities against the same tumors [83]. In gastric cancer, SCS allowed classification of infiltrating CD8+ T cell into several subsets, namely progenitor, intermediate, proliferative, and terminally differentiated [84], putatively, this may be pertinent for other cancer types.

In biliary tract cancer (BTC), two specific cancer cell subtypes were identified by SCS—extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ECC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC). ECC exhibited a unique immune profile characterized by T cell exhaustion, elevated CXCL13 expression in CD4+ T helper-like cells and CD8+CXCL13+ exhausted T cells, more mature TLS, and fewer “desert” immunophenotypes. In contrast, ICC displayed an inflamed immunophenotype with an enrichment of interferon-related pathways and high expression of LGALS1 in activated regulatory T cells, which is associated with immunosuppression [85].

Regulatory T cells (Tregs, FOXP3 dependent) are one of the major causes behind the failure of immunotherapies [86], being activated by complex cues including IL-33 [54]. Mechanistically, higher RANKL/RANK expression is associated with worse survival rates, and RANKL is typically produced by Tregs [87]. Importantly, TAMs and Tregs, independently or collaboratively, utilize metabolic mechanisms to suppress the activity of CD8+ T cells [88]. Tregs greatly affect the function of TAMs, since Treg cells suppress CD8+ T cell secretion of IFN

There are complex interactions between different cell types within TME. For example, predominant pro-tumor Th2-type inflammation in PDAC is associated with poor outcomes, whereas the presence of T follicular helper (Tfh) cells appears to improve survival. In PDAC patients, a recent important study on Tfh1-, Tfh2-, and Tfh17-like cell clusters showed that abundant Tfh2 cells within the tumors and tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLNs) correlated with worse survival [92]. Unexpectedly, it was also found that these Tfh2 cells inhibited the secretion of pro-inflammatory secretagogues [92]. While the presence of Tph cells is associated with worse prognosis in autoimmune conditions, intriguingly, their presence has been correlated with better outcomes in certain types of cancer. This suggests that they may be involved in the assembly of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS). Tph cells have been reviewed in another recent study [93].

There are complex links between neoantigen intratumor heterogeneity and antitumor immunity. In primary NSCLC, CD8+ TILs recognizing clonal neoantigens are present [70], moreover, regarding sensitivity to ICB in patients with NSCLC and melanoma, the presence of T cells recognizing specific neoantigen clones in patients correlates with durable clinical benefit [94].

An important discovery emerged from the analysis of tumor regions and adjacent nonmalignant lung tissues from patients with lung cancer, conducted for deep neoantigen exploration. Diverse immune cell populations were identified alongside the immunopeptidome, as anticipated. Interestingly, many neoantigens were located within HLA class I presentation hotspots in tumors that lacked infiltration by CD3+CD8+ T cells [95].

Other immune cell subtypes should indeed be delineated beyond

An interesting discovery regarding the mechanisms of intratumoral natural killer T cells (NKT) cells is their new role beyond the well-known function of facilitating type I interferon production to initiate adaptive immune responses through the interaction of their CD40L with CD40 on myeloid cells. In addition, NKT cells affect intratumoral infiltration of T cells, DCs, NK cells, and MDSCs. Notably, it was found that administering folinic acid to mice with PDAC increased the number of NKT cells in TME and improved their response to anti-PD-1 antibody treatment [97].

B cells are also important in tumor immunology, beyond immunoglobulin production. For example, in the B16F10 melanoma model, a subset of B cells expands in the draining lymph nodes (dLNs), and these cells express T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 (TIM-1). Selective deletion of the gene encoding TIM-1 in B cells substantially inhibits tumor growth. This indicates that the presence of TIM-1 in B cells plays a serious role in promoting tumor progression [98]. Plasma cells are also important in TME, especially this is clear from the role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1). It is important to remind that while some plasma cells are short-lived, others are long-lived, and among plasma cells, there is a subset that becomes long-lived plasma cells (LLPCs). LLPCs interact with stromal cells, producing an immunosuppressive enzyme IDO1, which activates upon the interaction of CD80/CD86 molecules on DCs. Once activated, IDO1 produces kynurenine, which activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in LLPCs, increasing CD28 expression and promoting signals of pro-tumor cell survival nature. Thus, kynurenine acts as an oncometabolite, supporting tumor progression [99].

Mast cells should not be forgotten, for example, SCS of cervical cancer types transformative tumor-associated MCs subpopulation with C2 ALOX5+ MCs was also found useful for inclusion in the prognostic correlations [100].

Natural killer (NK) cells have shown great promise as key anti-tumor agents, especially because they possess inhibitory HLA receptors and thus are capable to recognize cancer cells that evade detection by suppressing normal HLA expression. They are currently identified as CD256+ large granular lymphocytes, part of group 1 ILCs, and produce IFN-

In human colorectal cancer, it appears that NK cells are suppressed through the actions of both M2 macrophages and CAFs, where CAFs contribute to this suppression by secreting IL-8. Additionally, tumor cells express high levels of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), which is a highly important molecule that promotes the adhesion of monocytes, nurturing the immunosuppressive TME [102]. A recent SCS study also pinpointed the distinction between exhausted NK cells and NK cells with high killing potential, and the role of TIGIT and PRMT5 was delineated as markers of immunosuppressive action of TME on NK cells [103].

An important discovery is that intratumoral NK cells have fewer plasma membrane protrusions and exhibit disturbed sphingomyelin metabolism compared to peripheral NK cells. This reduction in membrane protrusions makes the formation of lytic immunological synapses less likely. Consequently, inhibiting sphingomyelinase presents a novel avenue to enhance anti-tumor therapies by promoting the effective formation of these synapses [104].

In aggressive tumors HLA loss is widespread—in addition to the natural variability of HLA in normal tissues. In a recent study [105], it was shown that 61% of lung adenocarcinomas (LUAD), 76% of lung squamous cell carcinomas (LUSC), and 35% of estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) cancers harbored class I HLA transcriptional repression. Not surprisingly, in LUADs, HLA loss of heterozygosity (LOH) was associated with metastasis. LUAD primary tumor regions that seeded metastases had a lower effective neoantigen burden than non-seeding regions. These findings are quite logical in terms of current paradigms of HLA loss [105]. Thus, NK cells should be regarded as prime candidates for cell-based antitumor therapies in many cancers, for example, in BRCA1/BRCA2 mutated breast cancer the role of NK for good anti-tumor response to therapies was shown to be immense [106].

The huge mass of neutrophils in the body has the potential to both destroy tumors and prevent metastasis to distant organs via lymph and blood. In metastasis, neutrophils generally play a protective role, but when they become tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs), they complicate the functions of cytotoxic cells. The short lifespan of neutrophils results in conditions that favor cancer cells evasion of immune responses, this process being mediated by massive cell death of neutrophils in TME (e.g., by ferroptosis [107]) creating a cancer cell protective milieu. An important question in cancer immunology is whether myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a subset of tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs). Among MDSCs, there is a specific group known as polymorphonuclear MDSCs (PMN-MDSCs), which are similar to TANs and are derived form a neutrophil lineage. PMN-MDSCs play a significant role in causing immune suppression in TME. According to recent data, MDSCs exert their action through PF4–CXCR3, thus leading to the establishment of an immune “desert” phenotype [108]. MDSCs apparently need G-CSF, and IL-6 for their formation, whereas, when formed, MDSC work in autocrine and paracrine modes, secreting NO, ROS, TNF-

Interestingly, while newly recruited neutrophils to tumor sites remain activated and highly motile, they become strongly immunosuppressive after exposure to factors secreted by cancer cells. In vitro naïve neutrophils incubated with cancer cell culture supernatant adopt a suppressive phenotype. An important secretagogue in this context is a lipid molecule, platelet-activating factor (PAF; 1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), which induces neutrophil differentiation into immunosuppressive cells. Notably, lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 2 (LPCAT2), the enzyme responsible for PAF biosynthesis, is upregulated in PDAC. This upregulation is significant because it leads to increased levels of PAF in the TME, promoting the differentiation of neutrophils into suppressive PMN-MDSCs. Therefore, inhibiting LPCAT2 may provide an additional avenue to enhance the efficacy of cancer therapies by preventing the formation of immunosuppressive neutrophils and restoring immune surveillance against the tumor [109].

Neutrophils are frequently classified into high-density neutrophils (HDNs) and low-density neutrophils (LDNs). LDNs can be further separated into immature myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and mature cells derived from HDNs in a TGF-

KRAS and TP53 co-mutations are pivotal in PDAC initiation and growth, where these mutations induce tolerogenic signaling from myeloid cells, like PMN-MDSCs, which promote T-cell dysfunction and exclusion, as well as pro-inflammatory polarization of iCAF that secrete IL-6 and other factors. It was found that a KRAS-TP53 cooperative “immunoregulatory” program exists in PDAC cells, where CXCL1 restricts T-cell activity through interactions with CXCR2+ PMN-MDSCs in human tumors. There, neutrophil-restricted TNF-

The activation of the Wnt–

In gliomas and cancer brain metastases, TANs support immunosuppression , where their complex interactions with other cells are mediated by tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-

In prostate cancer, high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is indicative of poorer survival and is associated with persistent inflammation mediated through tumor cell secretion CXCR2-binding chemokines, and recently it was demonstrated that pharmacological interference may be beneficial for some patients [114].

In colorectal cancer, metastasis to the liver correlated with infiltration of a neutrophil subpopulation denoted by high expression of PROK2, which exacerbated exhaustion of T cells [115].

On the contrary, in some models of melanoma, activated neutrophils were found to be required for successful eradication of tumors by ICB therapies perhaps involving NO metabolism [116].

It should be noted that some controversies may result from heterogeneity of TANs infiltration obsereved at a macro scale, for example, an extremely interesting recent report demonstrated the existence of oxidative neutrophil-rich hydrogen peroxide producing hotspots in most cancers [117], and this oxidative milieu promotes EMT.

Early studies found that, in TME, endogenous PGE2 acts as an anti-inflammatory agent by inhibiting the release of inflammatory chemokines from activated DCs, thereby preventing the excessive accumulation of activated immune cells. Moreover, in some contexts, PGE2 may also deactivate certain immune mechanisms [118]. In fact, PGE2 reprograms DCs, so that intratumoral cDC1s ignore CD8+ T cells. Mechanistically, cyclic AMP (cAMP) signaling downstream of the PGE2 receptors EP2 and EP4 reprograms cDC1s to become dysfunctional. However, blocking the PGE2–EP2/EP4–cDC1 axis can counteract PGE2-mediated immune evasion [119]. Additionally, PGE2-mediated disruption of pericytes is crucial for vascular destabilization [120]. The key enzyme in these processes is cyclooxygenase (COX); at least in melanoma, COX activity acts as a mechanism of immune suppression, so that inhibition of COX may even synergize with anti-PD-1 blockade adjuvants [121]. Accumulating data indicates that, in some cancer subtypes, COX inhibitors like coxibs and ibuprofen can improve survival, suggesting that COX inhibition may benefit patients with specific cancer subtype [122]. Moreover, even aspirin in some murine models can inhibit metastasis through halted production of T cell suppressive thromboxane A2 [123].

Interestingly, PGE2 attains high levels in healthy intestinal tissues, enhancing the function of infiltrating intestinal CD8+ T cells. In this context, PGE2 promotes mitochondrial depolarization in CD8+ T cells, induces autophagy to clear depolarized mitochondria, and increases glutathione synthesis to scavenge ROS resulting from mitochondrial depolarization, promoting this specific metabolic adaptation of CD8+ T cells to the intestinal microenvironment [124]. Carcinogenesis may disrupt this process, yet the remnants of this normal adaptation may persist in colorectal tumors. This could be one of the reasons why such tumors suppress T cell responses—T cells become quiescent and do not effectively act against tumors, entering an exhausted state.

A recent SCS analysis of immune cells has shown that PGE2-EP4/EP2 signaling impairs both adaptive and innate immunity in the TME by hampering the bioenergetics and ribosome function in TILs [125]. Also, PGE2 signaling through its receptors EP2 and EP4 mediates NK cell dysfunction. This leads to reprogramming of NK cell gene expression and results in impaired production of anti-metastatic cytokines [126]. Thus, these findings are consistent with each other. Furthermore, tumors can produce enhanced levels of PGE2, which reduces the ability of NK cells to degranulate, a critical process for their cytotoxic function against tumor cells. Additionally, PGE2 influences the expression of chemokine receptors on NK cells by inhibiting CXCR3 and increasing CXCR4 expression [127]. IL-15 in lung cancer could reduce NK cell sensitivity to PGE2, which is known to suppress NK cells in TME. Since IL-15 enhances CD25+ and CD54+ NK cell populations, which may infiltrate tumors and target cancer cells, even with PGE2 present, the targeted delivery of IL-15 to tumors should be explored in various contexts [128].

In a mouse model of T4 breast cancer, mice bearing PTGS-2 knockdown (KD) 4T1 tumors exhibited decreased tumor burden and lower levels of PGE2. Treatment of these mice with either a COX-2 inhibitor or an EP4 antagonist resulted in further decrease in tumor burden [129].

In tumors, interleukins have been shown to be critically involved in tumor-induced effects on immune cells. For example, neutrophil-derived IL-1

It is well known that CD8+ T cells undergo full effector differentiation and acquire cytotoxic anti-tumor functions through interactions with cDC1s. In this complex process, inflammatory monocytes play an important role. Unlike type cDC1s, which cross-present antigens, inflammatory monocytes obtain and present peptide-MHC I complexes from tumor cells through a process called by authors of this exciting study ‘cross-dressing’. Hyperactivation of MAPK signaling in cancer cells hampers this process by simultaneously blunting the production of IFN-I, and PGE2. This leads to impairment of the inflammatory monocyte state and reduces intratumoral T cell stimulation. Therefore, a viable strategy to improve the anti-tumor response is to enhance IFN-I cytokine production and block PGE2 secretion, which would restore this process and re-sensitize tumors to T cell–mediated immunity [133]. It should be emphasized once again that tumor-derived PGE2 shapes DC function by signaling through its two E-prostanoid receptors (EPs), namely EP2 and EP4, explaining T cell suppressive pro-tumor function of cDC2s cells [74].

Furthermore, mutant KRAS promotes immune evasion in cancer cells, in part by stimulating COX-2 expression. Therefore, targeting the COX-2/PGE2 pathway is beneficial to enhance pro-inflammatory polarization of myeloid cells and to increase the influx of activated cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, which improves the efficacy of ICB. It can be said that COX-2 signaling via PGE2 is a major mediator of immune evasion driven by oncogenic KRAS, that promotes resistance to immunotherapy and KRAS-targeted therapies [134].

An important recent finding suggests that mitotransfer—the transfer of mitochondria or mitochondrial DNA—is indeed a real phenomenon in cancer biology. Preliminary conclusions indicate that iCAFs transfer mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) to lung cancer cells to restore their ROS-damaged mitochondria. This mtDNA transfer helps tumor cells recover mitochondrial function impaired by oxidative stress, highlighting a novel mechanism by which iCAFs support tumor survival and growth [135]. In another fascinating discovery, CAFs were found to communicate with breast cancer cells through the formation of contact-dependent tunneling nanotubes (TNTs), which allow for the exchange of cellular cargo between the two cell types. These TNTs also facilitate the mitotransfer from CAFs to cancer cells. The fresh mitochondria acquired by the cancer cells sustain an increase in mitochondrial ATP production, which enhances cancer cell migration. This synergistic interaction is referred to as metabolic symbiosis [136].

Among the different types of extracellular vesicles (EVs), exosomes are particularly important. EVs from highly metastatic lung cancer cells can convert normal fibroblasts into iCAFs [135]. Exosomes in NSCLC cells deliver miR-155-5p from M2-polarized TAM, and such exosomes enhance the aggressiveness of NSCLC by activating the VEGFR2/PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in recipient cells [137]. CAF-derived EVs contain various signaling molecules, including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). For example, in PDAC, these EVs downregulate HLA-A expression [138]. Additionally, under hypoxic conditions, there is significant overexpression of miR-4488 in exosomes derived from hypoxic pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm cells. When macrophages absorb circulating exosomal miR-4488, they are prone to undergo M2-like polarization, which contribute to the formation of the premetastatic niche [139]. Similarly, in many tumors, especially in neuroendocrine tumors, exosomes can shift TAMs toward the M2 phenotype, especially those exosomes derived under hypoxic conditions [54, 140].

The formation of the premetastatic niche by exosomes from TNBC cells is an exciting concept that continues to garner interest. Exosomes derived from cancer stem cells (EVsCSC) and those from differentiated cancer cells (EVsDCC) contain distinct bioactive cargos, eliciting different effects on stromal cells in TME. Specifically, EVsDCC activate secretory CAFs, triggering IL-6/IL-8 signaling pathways and sustaining stemness features of cancer cells, and, vice versa, EVsCSC promote the activation of myCAFs and increase endothelial remodeling, enhancing the invasive potential of TNBC cells both in vitro and in vivo [141]. Additionally, at least some circulating tumor cells (CTCs) may be protected from T cells by EV-derived CD45, referred to as CD45+ CTCs. This mechanism may enhance their transfer through the blood from one TME to another [142].

In sarcoma research, it has been observed that alveolar macrophages prime the lung microenvironment for osteosarcoma metastasis, and EVs have recently been implicated in this process. A study comparing two osteosarcoma cell lines with different metastatic abilities—the highly metastatic K7M2 and the less metastatic K12—found notable differences in how their EVs interact with macrophages [143]. While EVs from both cell lines associate with M0 (unpolarized) and M1 macrophages, only EVs from the K7M2 cells associate with M2 macrophages. This specific interaction with M2 macrophages is abolished when the EVs are pre-treated with an anti-CD47 antibody. These findings suggest that exosomes may play a significant role in priming pre-metastatic niches in osteosarcoma and potentially in other tumors by influencing macrophage polarization [143].

Furthermore, it should be emphasized that in the immunosuppressive TME characterized by M2 macrophage infiltration, CYR61 production plays a significant role. Patients with colorectal cancer liver metastasis and fatty liver disease exhibit elevated nuclear Yes-associated protein (YAP) expression, increased CYR61 expression, and enhanced M2 macrophage infiltration. Thus, fatty liver-induced EVs-delivered microRNAs and YAP may be important contributors to tumor progression [144].

EVs can activate tumor-specific NK and T cell responses, either directly or indirectly, by transferring antigens to tumor-infiltrating DCs. However, phase I and II clinical trials have shown a limited clinical efficacy of EV-based anticancer vaccines [145]. To combat tumor-promoting EVs, it is feasible to employ competent EVs packaged with inhibitory cargoes [138]. EVs may be useful in many aspects, for example, abscopal effects may be also mediated by EVs [146].

The full realization of the obvious idea that tumors are not sterile but are, in fact, more susceptible to infections than normal tissues increasingly attracts research efforts, despite challenges for correct interpretation of experimental data [147]. In certain cancers—such as gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, bladder cancer—the role of bacteria is evidently significant, not only in the initial tumorigenesis but also in tumor progression at later stages, a fact that was also appreciated in the past, but deemed to be limited to either adverse reactions or effects from gut microbiome, which are definitely important at least in connection with the use of antibiotics [148]. In bladder cancer specifically, there is important communication between bacteria and M2 macrophages playing a crucial role in prognosis [149]. In PDAC, it was found that Stenotrophomonas correlates with shorter survivals of patients, while Neorickettsia and Mediterraneibacter are correlated with longer survival, although these findings represent correlations rather than causations [150].

Importantly, it is necessary to move beyond bulk sample analysis to utilize single-cell data that can resolve spatial intricacies within tumors. For example, in oral squamous cell carcinoma and colorectal cancer, recent studies have shown that bacterial communities populate microniches that are less vascularized, highly immunosuppressive, and associated with malignant cells exhibiting lower levels of Ki-67 compared to bacteria-negative tumor regions. Indeed, cancer cells infected with bacteria attract immunosuppressive myeloid cells [151].

Intratumoral bacteria have been found to promote metastasis in murine breast cancer models without affecting the growth of the primary tumor. An intriguing hypothesis suggests that these bacteria travel in clusters together with circulating tumor cells (CTCs). Within these clusters, the bacteria enhance the resistance of CTCs to fluid shear stress encountered in the bloodstream by reorganizing their actin cytoskeletons, helping the tumor cells survive in circulation and facilitate the metastatic process [152].

Recent intensive and fruitful studies have uncovered significant insights into the role of microbiota in cancer progression and treatment resistance. For example, it has been found that Fusobacterium may enhance resistance to ICB therapy in lung cancer [153]. Unsurprisingly, RNA sequencing data from patients with colorectal cancer treated with radiotherapy showed that hypoxia gene expression scores predicted poor patient outcomes. However, an interesting finding was that these tumors were enriched with certain bacterial species, such as Fusobacterium nucleatum and Fusobacterium canifelinum, which also predicted poor patient outcomes. This concept was verified in a murine syngeneic colorectal cancer model, where the tumors passively acquired microbes from the gastrointestinal tract. Upon harvesting the tumors, it appeared that there is indeed a link between the tumor hypoxic state and the microbiota, suggesting that tumor hypoxia may facilitate the colonization of tumors by specific bacteria, which in turn may contribute to poor patient outcomes [154]. In colorectal cancer, it has been also demonstrated that colibactin-producing Escherichia coli (CoPEC) can significantly affect the lipidome of cancer cells by creating a glycerophospholipid-rich microenvironment. These bacteria may decrease the immunogenicity of the tumor, leading to reduced infiltration of CD8+ T cells. This effect is possibly mediated through the formation of lipid droplets in infected cancer cells following colibactin production. Additionally, heightened phosphatidylcholine remodeling via enzymes involved in the Lands cycle supplies CoPEC-infected cancer cells with sufficient energy to sustain survival, especially in response to chemotherapy treatments. It is fascinating to note that the Lands cycle—a crucial pathway in lipid metabolism—is involved in and influenced by microbiota such as CoPEC. This interaction appears to correlate with clinical outcomes, as colorectal cancer patients at stages III–IV who are colonized by CoPEC exhibit lower overall survival rates compared to patients at stages I–II. Therefore, targeting the enzymes of the lipid turnover, such as acyl-CoA synthetase, presents a promising new strategy for the development of synergistic therapies aimed at improving patient outcomes [155]. Another study [156] focused on colorectal cancer liver metastasis: it was shown that E. coli residing in TME microenvironment can enhance lactate production. This lactate mediates M2 macrophage polarization by suppressing NF-

Some recently published data suggests that certain microbiota profiles can be favorable. For example, in gastric cancer, butyric acid producing bacteria correlate with improved survival outcomes [157]. Similarly, in HCC, Intestinimonas, Brachybacterium, and Rothia have been identified as independent risk factors affecting the overall survival of HCC patients who underwent treatment [158]. In contrast, in lung cancer, certain microbiota may promote tumor progression by acting suspiciously similarly to histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2), leading to an increase in H3K27 acetylation at the H19 promoter, inducing M2 macrophage polarization. It appears that butyrate might be an important substance involved, as it boosts metastasis through an effect that is dependent on TAMs [159] (thus the effect of butyrate may be cancer context dependent (compare to [157]).

In lung cancer, fungi can have detrimental effects and a particularly concerning example is the presence of tumor-resident Aspergillus sydowii in patients with lung adenocarcinomas. Also, in syngeneic lung cancer mouse models, A. sydowii has been shown to promote lung tumor progression via IL-1

Definitely, not all tumors are densely infected. Sarcomas, for instance, appear to lack a consistent and stable microbiome, containing only random bacteria [161]. Conversely, this absence of a stable microbial community might explain why bacteriotherapy (this old approach continues to garner certain interest) could be considered a potential treatment option for such malignancies [162]. Interestingly, emerging evidence suggests that the combination of bacteria and fungi may be more effective than bacteriotherapy, implying a synergistic interaction between the two could play a significant role in therapy and disease progression [163]. Recall that Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) is used in the treatment of bladder cancer, and while its antitumoral activities are predominantly thought to rely on stimulating an effective adaptive immune response, evidence demonstrates that macrophages alone can induce tumor apoptosis and clearance after stimulation with BCG, indicating that several additional mechanisms are elicited by BCG in inducing anti-tumor immunity beyond merely activating the adaptive immune system [164]. As the mysteries of intratumoral microflora are uncovered, there is renewed interest in anti-cancer bacteriotherapy, for example, it was found that intratumoral E. coli can transform TAMs into the M1 phenotype [165].

One of the most surprising findings in studies of intratumoral microbiota is that mice with increased availability of vitamin D exhibit greater immune-dependent resistance to transplantable cancers and enhanced responses to ICB therapies [166]. Furthermore, vitamin D-induced genes correlate with improved responses to ICB, and better overall survivals in human patients. The mechanism behind this phenomenon may involve vitamin D, which affects the gut microbiota in favor of Bacteroides fragilis within the intestines [166]. However, in humans, this relationship is likely more complex and less consistent, as previous studies have not consistently observed such a significant influence of vitamin D on the survival of patients with aggressive cancers.

Previously there have been great hopes that manipulating metabolism of both cancer cells and surrounding cells may have a strong impact on tumor growth. These included acidification, hypoxia, lack of specific nutrients etc, now this amount of efforts look partially overjustified. nevertheless, no one doubts that these factors remain to be important, and special attention is attracted to the fact that hypoxia in TME impedes activation of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs) [38].

A surprising finding reveals that IL-4 and tumor-conditioned media upregulate PHGDH expression in macrophages, promoting the activation and proliferation of immunosuppressive M2 TAMs. PHGDH-mediated serine biosynthesis appears to enhance

Adaptation of Treg cells within TME is crucial in the fight against cancers, and it is surprising that simple factors like acidity significantly enhance the immunosuppressive functions of Treg cells, without altering expression of their critical transcription factor FOXP3. Even a simple addition of lactate boosts the acidity-induced enhancement of Treg functions, possibly due to increased mitochondrial respiratory capacity and ATP-coupled respiration, highlighting the importance of metabolic programming [168]. In gastric cancer, IGF2BP3 overexpression may promote lactate accumulation, impairing CD8+ T cells’ antitumor activity, similarly to the effects mentioned above [169].

Efforts to intervene in the metabolism of TME are significant. In prostate cancer, secreted lactate apparently is produced mostly by CAFs. This lactate promotes the expression of collagen-related genes in prostate cancer cells, and

Attention is increasingly focused on fatty acid metabolism in the TME. Recent reviews explore lipids in cancer [171], with a particular focus on cancer stem cells [172]. It is plausible that fatty acid availability influences both cancer and, more importantly, immune cells, thus accessible fatty acids might enhance the effectiveness of immunotherapies [173], at least in some PDAC models adipocytes supported tumor growth [174]. However, in general, lipid accumulation in TAMs boosts metastasis: specifically, linoleic acids (LA), via the FABP4/CEBP

In glioblastoma, SCS data suggests that extracellular ATP (eATP) produced by TAMs in the presence of GBM cells supports cancer cell proliferation [179]. Although eATP typically acts as a DAMP to attract CTLs, this may be unique to immune-privileged environments like the brain.

Regarding lipid metabolism interventions, the limited supply of arachidonic acid (AA) may be beneficial, as CAFs promotion of cancer progression and induction of fibrosis may be related to AA-induced secretion of IL-11 in lung fibroblasts, dependent on the activation of p38 and ERK MAPK signaling pathways. Also, PGE2, linked to elevated COX-2 expression, upregulates IL-11, exposing the role of COX-2, PGE2, and possibly other eicosanoids in cancer progression [180]. Thus, AA potentially has pro-cancer effects as a precursor of eicosanoids, whereas supplementation by site-specifically deuterated AA, resistant to oxidation, were hypothesized to offer some benefits [181]. During chemotherapy, inhibiting PGE2 signaling may enhance the efficacy of combining chemotherapy with PD-1 blockade even in poorly immunogenic breast cancer models [182]. Conversely, AA may enhance the action of T cell-derived IFN

The role of adipose tissue become unveiled in more elaborate recent studies, for example, in ovarian cancer models, the presence of adipocytes the cancer cell metabolism is shifted to accumulation of glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P), rendering them more metastasis-prone [185]. In breast cancer, at least p53 deficient cells educate preadipocytes into inflammatory cells that support cancer cell protective TME [186].

A recent review highlighted signals like those from TGF-

Ion homeostasis is crucial in immune cell exhaustion. Notably, deficiency in the

Epigenetic factors play a crucial role in shaping TME, as they are profoundly related to the evolution of neoantigens [70]. The interplay between evolving cancer and the dynamic TME is rather complex: in early-stage, untreated NSCLC tumors, immune infiltration varied both between and within tumors. As expected, low infiltration correlates with low neoantigen variability, whereas dense infiltration suggests strong immunoediting, driven by Darwinian processes, but the mechanisms behind this heterogeneity are apparently epigenetic: for example, promoter hypermethylation of genes with neoantigenic mutations was detected [189]. Overall, the role of epigenetic modifications is becoming clearer, those that stand behind immune exhaustion have been reviewed, highlighting major factors like transcription factor locations, histone modifications, DNA methylation, and three-dimensional genome conformation [190]. Evidence suggests that inhibiting DNA methylation can enhance the memory of TILs, countering tumor cells that modify their epigenomes [191], although the effects of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine might involve mechanisms beyond DNA methylation inhibition.

Lactylation was discovered relatively recently and now is attracting great attention—e.g., (H3K18la) in NSCLC, where it was correlated with poor patient prognosis. Thus it is an attractive target to boost CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity [192]. In PDAC, lactylation also has been recently reported to promote immunosuppressive TME [193]. This intreresting protein modification thus emerged as a promising target for pharmacological control [194].

In melanoma, IL-7 appeared as a highly important mediator of immune exhaustion, since high IL-7R expression marks a CD8+ population in lymphoid organs with strong cytotoxic activity, lacking exhaustion markers and showing superior antitumor efficacy. Hypomethylating agents can improve the DNA methylation profile of IL-7Rhigh cells, boosting survival in a murine melanoma model. Furthermore, IL-7R expression in human melanoma is an independent prognostic factor for improved survival [195].

The complexity of immune exhaustion is evident in recent examples of interesting research achievements like the identification of S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR), a denitrosylase enzyme, as a tumor suppressor. GSNOR deficiency in tumors links to poor prognosis and survival in colorectal cancer patients, partly due to the exclusion of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. GSNOR knockout cells exhibit enhanced immune evasion and resistance to immunotherapy. They undergo a metabolic shift from OXPHOS to glycolysis for energy, demonstrated by increased lactate secretion, and a fragmented mitochondrial network. This metabolic reprogramming resulting from GSNOR deficiency contributes to tumor progression and immune evasion in colorectal cancer [196]. Introducing this enzyme as a transgene could potentially remodel the tumor microenvironment to foster more favorable conditions.

A recent study [197] unveiled a significant role of retinoic acid-inducible gene I protein (RIG-I), primarily expressed in immune cells like T cells, a key pathogen pattern recognition receptor. RIG-I detects RNA structures through its carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD) and acts as an intracellular checkpoint in CD8+ T cells within TME, inhibiting their anti-tumor activity via the AKT/glycolysis signaling pathway. RIG-I normally aids in fighting pathogen invasion by activating immune cells from signals presented by APCs. However, tumor cells exploit this by amplifying immune checkpoint signals, causing immune escape. While RIG-I activation can enhance ICB therapies, it can also contribute to T-cell exhaustion, characterized by reduced cytokine production and increased inhibitory receptor expression. Moreover, overactive T cells upregulate RIG-I to evade CD8+ T cell-mediated killing. Targeting RIG-I in human CD8+ T cells improves the effectiveness of adoptive T cell therapy in reducing tumor growth. Although targeting RIG-I poses infection aggravated risks, it holds potential for anti-tumor therapies [197].

How can we enhance ICB effects in tumor therapies? Complex networks in TME must be addressed, for example, in some mouse cancers SCS showed that co-inhibitory receptors (PD-1, TIM-3, LAG-3, TIGIT) interact with previously underexplored receptors such as PROCR and PDPN, which are co-expressed in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, when induced by IL-27 [198]. This complexity explains why antibodies against PD-1 or CTLA-4 alone are not always effective. Recently, many new findings have emerged, elucidating immune exhaustion mechanisms. For example, exhausted CD8 T (Tex) cells co-express inhibitory receptors (IRs), but such Tex cells can be reinvigorated by blocking IRs like PD-1, or more effectively by co-targeting multiple IRs, such as PD-1 and LAG-3 [199]. The loss of PD-1 and/or LAG-3 on Tex cells in chronic infection is important, and this may also be true in cancers.

Enhancing ICB through combination therapies can boost cancer treatment effectiveness. Interleukins such as IL-1 and IL-12 play a role in antitumor immunity by affecting TME, not cancer cells proper. Cytokines like IL-36

In TME, it is preferable to avoid induction of apoptosis and instead aim at eliciting immunogenic cell death (ICD) or necrosis in cancer cells and their surrounding, as apoptotic death can enhance metastatic growth in neighboring cells [201]. Similarly, radiotherapy in gliomas can lead to the production of EVs (predominantly exosomes) from apoptotic cells, promoting more aggressive tumor types [202]. EVs from GBM also stimulate formation of is tumor-associated foam cells (TAFs), lipid-loaded macrophages that promote pro-tumorigenic traits. Therefore, inhibition of enzymes involved in lipid droplet formation, could be a viable strategy in GBM treatment [203]. Additionally, exosomes have been implicated in prostate cancer metastasis, affecting TAMs, TANs, and CAFs [204]. Thus, ICD in tumor or stromal cells can aid in making the right therapeutic choices.

A promising approach involves the use of cDC1 cells to reprogram cancer cells into professional APCs (tumor-APCs). By expressing key transcription factors such as PU.1, IRF8, and BATF3, a cDC1-like profile can be induced in both human and murine cell lines, which present endogenous tumor antigens on MHC-I, thus rendering them sensitive to CD8+ T cells. Such tumor-APCs showed reduced tumorigenicity both in vitro and in vivo–injecting in vitro-generated melanoma-derived tumor-APCs into subcutaneous melanoma tumors delayed tumor growth and increased survival in mice [205]. However, it is still unclear if this approach is feasible in a clinical setting.

Recent discoveries attract attention to other factors important for TME, and immune cell exhaustion, for example, it was found that exhausted CD8+ T cells overexpress

Elimination of CAFs in tumors can expose cancer cells to CAR-T and other cell therapies. In treating desmoplastic pancreatic tumors, targeting the fibroblast activation protein (FAP) on CAFs disrupts the structural integrity of the desmoplastic matrix. This allows treatments like mesothelin-targeted CAR-T cells and anti-PD-1 antibody therapy to be more effective, as T cells gain easier access to the cancer cells [210] (also recently reviewed in [211]).

The anti-neoangiogenesis treatments long known to be effective in many cancers may benefit from discoveries on concerted actions of VEGF and angiopoietin 2, and their synchronous blockade is promising [212], but perhaps more complex combinations should be tested as enhancers of immunotherapies [213] reversing the anergic phenotype of endothelial cells in cancer-associated blood vessels. Indeed, the topic of vascularization is of paramount importance for tumor growth both the induction of neoangiogensis and intercellular communications between the tumor and endothelial cells. In these context, various cells like pericytes are also important for TME formation [16].

Numerous failures with promising therapeutic approaches to treat aggressive cancer types such as PDAC pose the question that maybe the problem is not only physical access to immune cells, but, rather, tumors may inherit an intrinsic immune response limiting program from normal tissues of origin [187], and, also, this may be enhanced by cellular senescence in TME for PDAC [214] and breast cancers [215].

Summarizing the key advancements in studying TME with new methods, it is possible to state that a significant progress has been achieved in recent years, with much higher resolution at the cellular level, allowing better understanding of cell distribution and interaction. Traditional analyses of protein modifications or gene expression levels often failed to provide decisive insights, since many cancer-related genes may have opposing effects depending on the tumor-specific context. By distinguishing between cancer cell-autonomous processes and those involving TME, our understanding improved significantly, and this is particularly beneficial in understanding aggressive cancers like PDAC, where dysplastic fibroblasts outnumber cancer cells. Single-cell analysis revealed significant heterogeneity among histologically similar cells. Finally, factors like intratumoral microbiota, previously regarded either as insignificant or chaotic (thus too unpredictable to employ in therapies), are starting to show patterns that can be standardized and used to enhance therapeutic options.

Clearing TME barriers around dividing cancer cells, shielded by stiff ECM and “educated” non-transformed cancer-associated cells, and addressing the exhaustion of infiltrating immune cells constitute major priorities in developing therapeutic boosts of anti-cancer treatments, which may work well in simple in vitro systems or preclinical models, whereas real-life medicine faces much more resistant tumors due to the heterogeneity of both cancer cells populations and TMEs. It is necessary to study both oncotherapeutic resistance and clinical cases of exceptional responders to traditional and innovative treatments. In the latter, understudied phenomena like the intratumoral microbial insemination may play a critical role, providing fresh insights in order to develop novel agents that can overcome the obstacles created by TME, exposing cancer cells to cytotoxic cures.

CAFs, cancer associated fibroblasts; FAD, flavine adenine dinucleotide; ECM, extracellular matrix; FN, fibronectin; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; GEMM, genetically engineered mouse model; HSPCs, hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells; ICB, immune checkpoint blockade; MET, mesenchymal-epithelial transition; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PML-NBs, promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies; PPI, protein-protein interaction; TNBC, triple negative breast cancer.

TVK prepared figures. TVK, NBP wrote the paper. MIS provided funding. NAB wrote the initial plan and edited the first manuscript. NBP, MIS, and NAB collected and sorted references. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Authors are grateful to Nadine V. Antipova for her excellent advice.

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation 24-15-00097 (to TVK).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.