1 Faculty of Science, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice, 040 01 Košice, Slovakia

Understanding the human gut microbiome has traditionally focused on the relative abundance of bacterial taxa, while largely overlooking total microbial biomass. A recent study published in Cell by Nishijima et al. [1] reframes this approach by demonstrating that microbial load—the total number of microbial cells per gram of feces—is a powerful, yet often neglected, determinant of microbiome structure, function, and health outcomes. The conclusions are drawn from two large-scale cohorts: GALAXY/MicrobLiver (n = 1894) and MetaCardis (n = 1812). This study showed that microbial load is a major determinant of gut microbiome diversity, function, and inter-individual variation (see Fig. 1), and demonstrated that correcting for microbial load substantially reduces the statistical significance of many disease-associated species, thus reinforcing the central findings of the original work. The data can be used in follow-up studies to develop machine-learning algorithms for forecasting microbial load-based relative abundance.

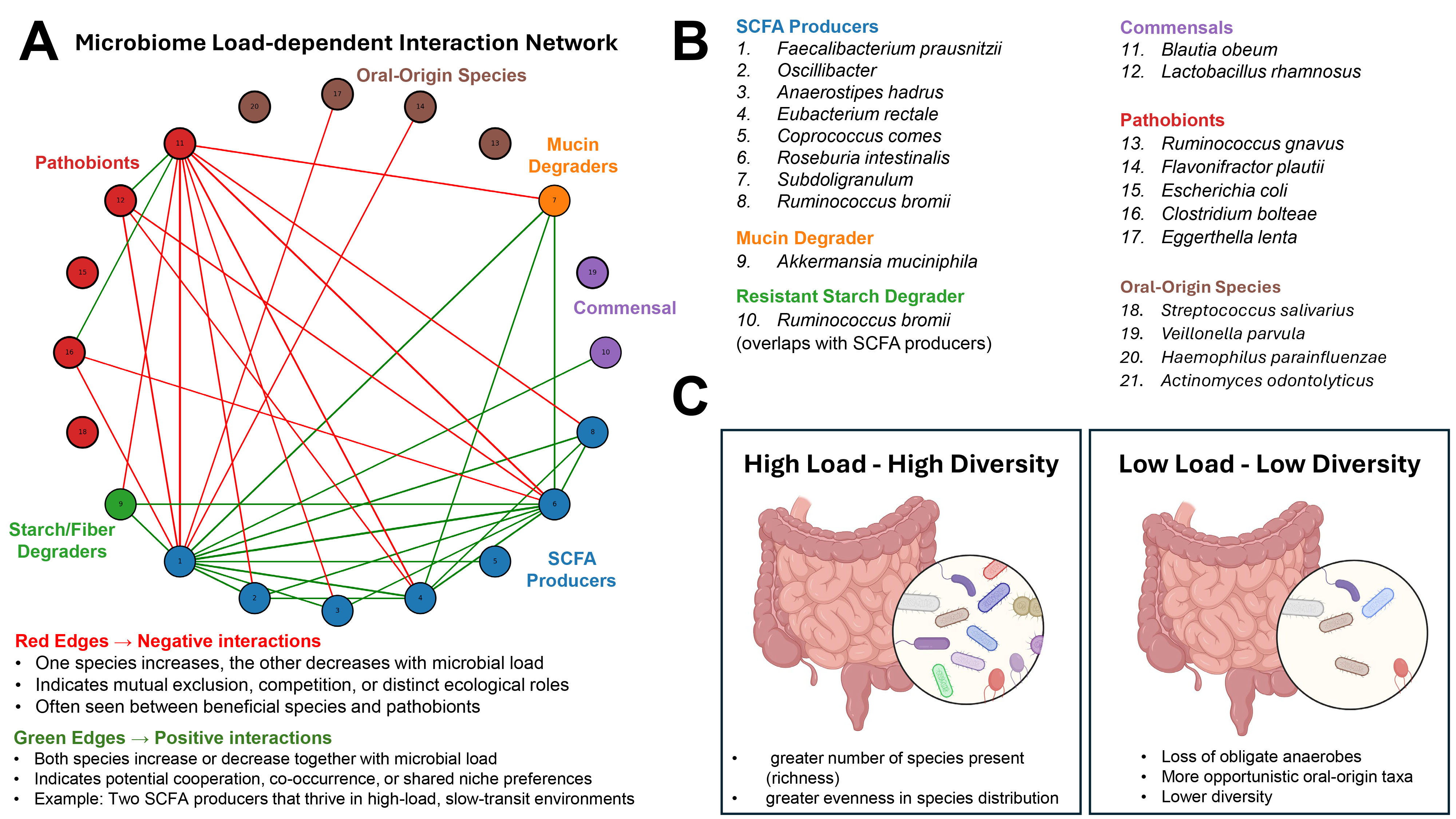

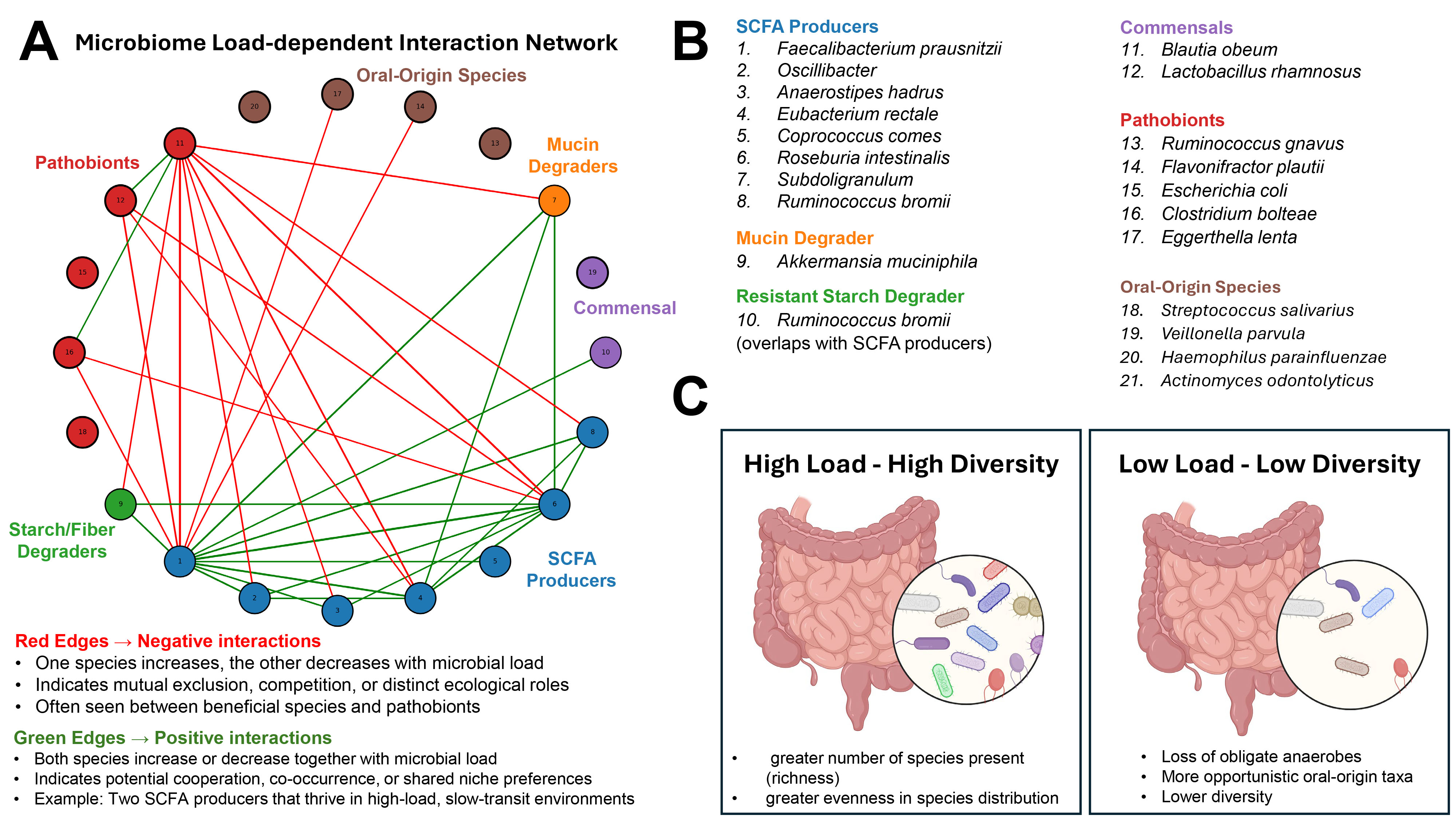

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Microbial load-dependent structure of the gut microbiome. (A) Interaction network of 20 selected gut microbial species derived from their correlation patterns with microbial load across human cohorts (species selection was based on the top 20% highest values of correlations, data taken from Fig. 1C in [1]). Nodes are color-coded by functional group (e.g., short-chain fatty acid [SCFA] producers, pathobionts, oral-origin species), and edges represent interaction types: green = positive correlations (co-occurring responses to microbial load), red = negative correlations (inverse responses). (B) Functional grouping of species included in the network, highlighting ecological roles such as SCFA production, mucin degradation, and oral-origin transients. (C) Conceptual model illustrating the relationship between microbial load and community diversity: high-load environments support diverse, anaerobic, health-associated microbiota, while low-load environments are characterized by reduced diversity, loss of obligate anaerobes, and increased prevalence of oral-origin or stress-tolerant taxa. Created with BioRender.com.

Measuring microbial load: Beyond relative abundance. Microbial load in the study by Nishijima et al. [1] was quantified using flow cytometry, where fecal samples were stained with DNA-binding dyes and microbial cells were counted directly. This allowed the authors to move beyond compositional (relative) data and explore how absolute cell numbers influence microbiome ecology. By comparing total microbial cell counts with genetic profiles of the gut microbiome, the authors showed that more microbes usually means a more diverse and functionally capable microbial community. To quantify associations between individual taxa and microbial load, the authors computed Pearson correlations between load measurements and relative abundances of bacterial species across hundreds of individuals. Then, species showing high positive or negative correlations were mapped to ecological and functional categories. Notably, oral-origin species such as Streptococcus and Veillonella spp. were negatively correlated with microbial load, indicating enrichment in low-biomass samples, potentially due to reduced competition or transit time effects.

While flow cytometry was used effectively in the study by Nishijima et al. [1] to estimate microbial load by staining fecal cells with DNA-binding dyes, this technique has inherent limitations. For instance, it can have difficulty differentiating between microbial cells and non-biological particles, particularly in complex matrices like feces, and it does not distinguish live from dead cells without viability dyes. In addition, variations in staining efficiency and cell aggregation may affect count accuracy. To enhance robustness, complementary methods such as quantitative PCR (qPCR), which targets conserved bacterial genes (e.g., 16S rRNA gene copy number), or digital PCR for absolute quantification, can be employed. Gravimetric or dry weight measurements and total DNA extraction yield are also commonly used proxies for microbial biomass, although they can be influenced by host DNA or other contaminants. A multimodal approach integrating flow cytometry with qPCR and total DNA quantification would offer a more accurate and resilient framework for assessing microbial load across diverse sample types.

Microbial load and community resilience. Nishijima et al. [1] observed that high microbial load was associated with increased alpha diversity, metabolic potential (e.g., short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) biosynthesis), and prevalence of health-associated taxa like Faecalibacterium. By contrast, low-load states reflected microbial collapse, with reduced diversity and increased representation of stress-tolerant or transitory taxa. These low-load patterns were mirrored in disease states such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and diarrhea. This concept of a biomass-dependent ecological state is reinforced by animal models of ulcerative colitis induced in pseudo-germ-free mice (e.g., Gancarcikova et al. [2], Lauko et al. [3]). These studies confirm that microbiota depletion or dysbiosis alters host immunity and metabolic signaling. Importantly, restoration of load via fecal microbiota transplantation improved clinical outcomes in colitis, highlighting the therapeutic relevance of re-establishing microbial biomass.

A context for probiotic interventions. Works by Strompfová et al. [4, 5] and Bomba et al. [6] in canine models showed that probiotic interventions (e.g., with Bifidobacterium or Limosilactobacillus spp., formerly classified under Lactobacillus) can modulate microbial balance and increase beneficial SCFAs, but their effects may depend on baseline microbial load. These studies support the idea that microbial load is not only an ecological variable but also a critical consideration in designing microbiome-targeted therapies. While the cited probiotic studies [4, 5, 6] suggest beneficial modulation of microbial balance and SCFA levels, it is important to acknowledge that probiotic effects are often highly strain-specific. Not all strains within a species (e.g., Limosilactobacillus fermentum) exert comparable functional effects, and their efficacy can depend on formulation, dosage, and delivery method. Moreover, host–microbe interactions are context-dependent, with outcomes shaped by baseline microbiota composition, immune status, and diet. These factors complicate efforts to generalize findings across populations. In addition, the majority of current evidence stems from preclinical models, particularly in dogs or rodents, which differ from humans in gut anatomy, physiology, and microbial ecology. Translational gaps remain a major barrier, and future research should incorporate human-relevant models and personalized approaches to probiotic development.

Relevance for functional annotation. The Cell study [1] used a gene classification system called KEGG Orthology (KO) to match microbial genes with their potential biological roles. Samples with higher microbial load showed a broader range of gene functions, including those linked to health benefits. For example, genes like K00844, which codes for a common enzyme (hexokinase), were found more frequently in high-load communities, suggesting these communities may have greater metabolic potential.

While the association between microbial load and ecological or health outcomes is compelling, it is important to note that the findings remain correlative in nature. Observations of low microbial biomass in disease states, such as IBD or diarrhea, do not establish microbial depletion as the cause of dysbiosis or pathology. Such associations may reflect downstream effects of host-driven inflammation, altered gut motility, or other physiological disruptions. Establishing causality will require controlled interventional studies and longitudinal designs, including mechanistic validation in gnotobiotic models. Therefore, future work should prioritize experimental frameworks that can distinguish whether microbial load is a driver, consequence, or epiphenomenon of host–microbiome dynamics. While the study by Nishijima et al. [1] provides compelling evidence that microbial load shapes gut microbiome structure and function, it is important to note that this relationship may not be universal across all disease states. For instance, certain conditions, such as obesity or metabolic syndrome, may not consistently exhibit reduced microbial burden, and in some cases, microbial load may remain stable or even increase despite dysbiosis. Moreover, methods for absolute quantification of microbial biomass—such as flow cytometry, qPCR, and total DNA yield—are subject to technical variability, matrix effects, and practical limitations, particularly in large-scale clinical settings. These challenges can influence the reproducibility and comparability of microbial load measurements across studies. Therefore, while the proposed framework offers a valuable shift in perspective, its translation into clinical diagnostics or intervention strategies will require further standardization, validation, and contextual refinement.

Future directions. Building on this foundation, several forward‑looking studies may help to accelerate the translation. We see four major points as potential key drivers:

1. Mechanistic basis of dynamic load variation; 2. Clinically actionable load thresholds; 3. Cross‑population generalizability; and 4. Multiomics integration for causal inference.

Longitudinal multiscale studies that integrate host parameters—mucosal nutrient flux, bile‑acid pools, intestinal motility, and innate immune effectors—with microbial community dynamics will clarify how host–microbe and microbe–microbe interactions jointly drive load fluctuations. Gnotobiotic and ex vivo gut models offer tractable systems for causal perturbations. Next, establishing population‑level reference ranges for “eubiosis”, “dysbiosis”, and biomass collapse will require harmonized absolute‑quantification methods (flow cytometry, qPCR, droplet digital PCR) linked to host metabolic and immunological readouts. To this end, defining these thresholds is a prerequisite for load‑informed diagnostics and intervention trials. Meta‑analyses spanning diverse geographies, diets, age groups, and disease phenotypes—facilitated by federated learning to mitigate batch effects—will test whether load–diversity relationships and threshold values are conserved or context‑dependent. Such efforts are critical for global applicability of load‑based biomarkers.

Coupling metagenomics with untargeted metabolomics, metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and high‑throughput culturomics will map how absolute abundance translates into metabolic output and host molecular phenotypes. Causal mediation analysis, isotope‑tracing, and targeted perturbations (e.g., defined consortia, phage therapy) can then validate mechanistic links between functional activity and microbial load. Future studies are essential to move beyond association to mechanism, refine microbiome‑based diagnostics, and unlock biomass‑aware therapeutic strategies.

MŽ, NCH, GŽ designed the research study, performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The research was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the Contract no. APVV-23-0212. GŽ is partly funded by the European Union’s NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under the project No. 09I03-03-V03-00008.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.