1 School of Life Sciences, University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, NSW 2007, Australia

Abstract

Transcription factors are significant regulators of gene expression in most biological processes related to diabetes, including beta cell (β-cell) development, insulin secretion and glucose metabolism. Dysregulation of transcription factor expression or abundance has been closely associated with the pathogenesis of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, including pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1), neurogenic differentiation 1 (NEUROD1), and forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1). Gene expression is regulated at the transcriptional level by transcription factor binding, epigenetically by DNA methylation and chromatin remodelling, and post-transcriptional mechanisms, including alternative splicing and microRNA (miRNA). Recent data indicate a central role for transcription factors in pancreatic β-cell failure in the context of systemic insulin resistance and chronic inflammation. Therapeutic modulation of transcription factor abundance via gene therapy, small-molecule pharmacology, and epigenetic therapies holds great promise for β-cell restoration and metabolic normalisation. However, further clinical translation will require targeted delivery to appropriate tissues, minimising off-target effects and ensuring long-term safety. This review focuses on the involvement of pancreatic β-cells and transcription factors in diabetes development and their therapeutic implications, intending to develop and consolidate a basis for further research in this area and for the treatment of diabetes in the future.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- diabetes

- pancreatic transcription factors

- epigenetic therapy

- chromatin remodeling

- metabolic dysfunction

- insulin resistance

- hepatic gluconeogenesis

- lipid metabolism

- inflammatory responses

- islet cell types

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disorder characterised by persistently high blood glucose levels over a relatively long period [1]. Due to a paradigm shift in lifestyle, aging of the population, and increasing rates of obesity, the global prevalence of the disease has increased phenomenally within the last two decades [1]. In 2021, there were 529 million (95% uncertainty interval [UI] 500–564) people living with diabetes worldwide, and the global age-standardised total diabetes prevalence was 6.1% (5.8–6.5). Prevalence has been rising more rapidly in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income countries. The study in the Lancet predicted that between 2021 and 2050, the global age-standardised total diabetes prevalence is expected to increase by 59.7% (95% UI 54.7–66.0), from 6.1% (5.8–6.5) to 9.8% (9.4–10.2), resulting in 1.31 billion (1.22–1.39) people living with diabetes in 2050 [2]. Diabetes leads to serious long-term complications, which are broadly categorised as macrovascular or microvascular. Macrovascular complications affect large vessels and result in cardiovascular events such as heart attack and stroke [3]. Microvascular complications affect smaller vessels and cause diabetic retinopathy, which affects the eyes, diabetic nephropathy, and diabetic neuropathy, which affects the nerves [4]. These complications reduce the quality of life of patients with diabetes and contribute to other health conditions, including an increased risk of infection and foot conditions [4, 5]. Diabetes is a life-threatening condition requiring constant management and treatment [5].

Transcription factors (TFs) are a class of proteins that bind specific DNA sequences to modulate the transcriptional activity of genes. They regulate the expression of genes at the transcription stage and, therefore, play a critical role in switching genes on and off and controlling the extent of expression. Transcription factors may function as activators that stimulate transcription or repressors that block this process [6]. This regulatory system is essential for many cellular processes, including development, differentiation, and environmental responses. The binding of transcription factors to DNA at the promoter or enhancer regions is a crucial way RNA polymerase is either enabled or prevented from transcribing a gene to produce the corresponding mRNA [3]. TFs are therefore central to maintaining cellular identity and function, with consequences of aberrant function observed in diseases such as cancer and some genetic disorders such as diabetes, congenital hypothyroidism, and syndromes such as Rett syndrome and Waardenburg syndrome, all considered to be linked with mutations that affect specific transcription factor genes [7].

TFs connect cellular signalling pathways to major metabolic functions such as

insulin secretion and beta cell (

TFs play important roles in diabetes management by regulating metabolic pathways that influence metabolic processes, such as lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity. For instance, forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1) is a major transcription factor that controls hepatic gluconeogenesis; inhibition of this factor reduces glucose overproduction and increases sensitivity to insulin. In contrast, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP1c) controls lipogenesis in the liver and its overactivity contributes to hepatic steatosis and hyperlipidaemia. Thus, the specific targeting of these factors by selective inhibitors or modulators may offer alternative valid therapeutic approaches to metabolic dysfunction with fewer side effects. The complex mechanisms developed in relation to these TFs interact with signalling pathways such as PI3K/protein kinase B (Akt) and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). A deeper understanding of these factors will lead to the development of safer and more effective therapies against diabetes [1].

This review outlines the knowledge gaps related to the role and mechanism of TFs

in pancreatic islet cells, with particular emphasis on pancreatic

TFs are determinants of developmental stages in pancreatic

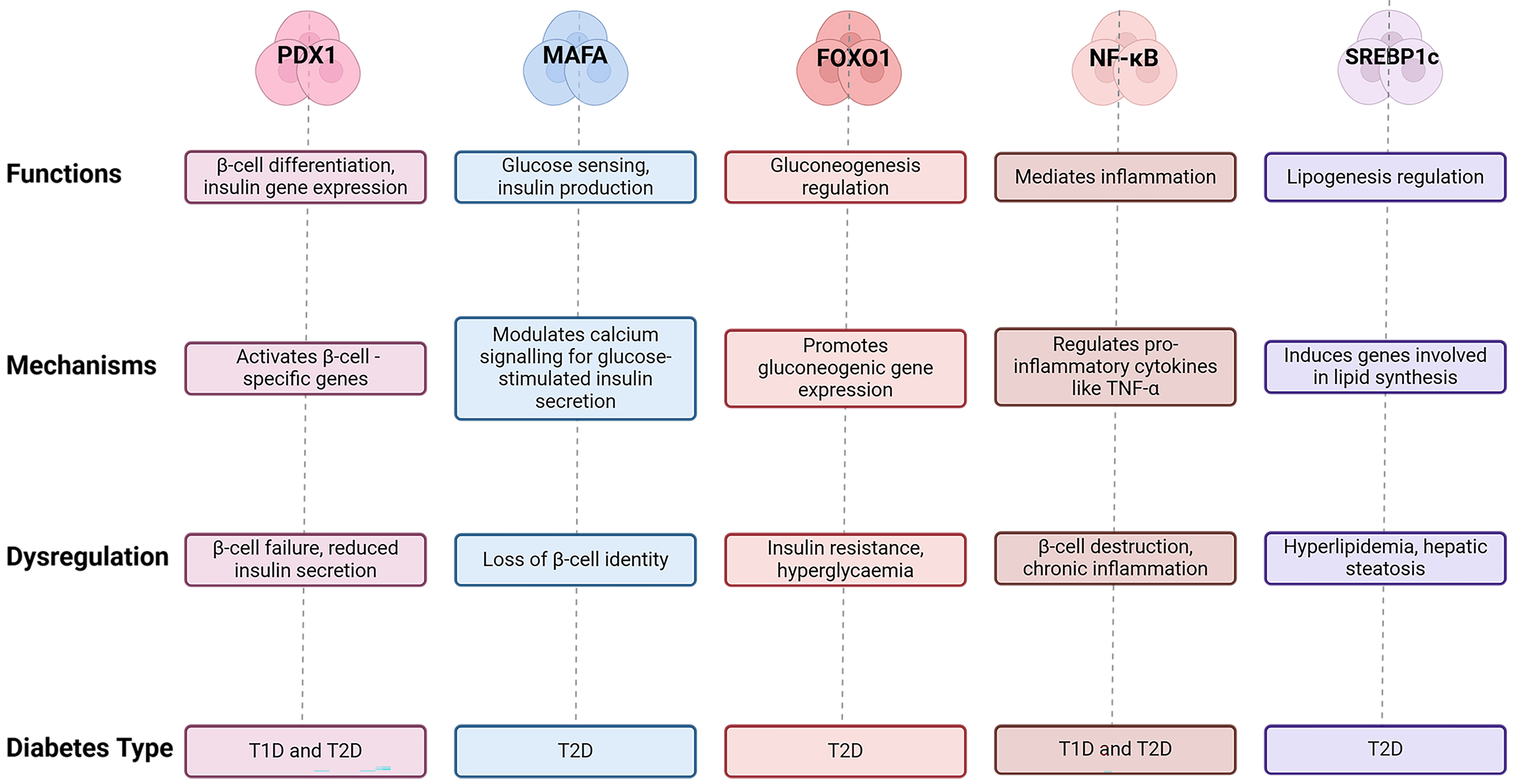

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The role(s) of the major TFs involved in the

pathogenesis of diabetes, including PDX1, MAFA, FOXO1,

NF-

| Transcription factor | Function | Mechanism | Diabetes type | Dysregulation outcome | References |

| PDX1 | Activates |

T1D, T2D | [11, 12] | ||

| MAFA | Glucose sensing, insulin production | Modulates calcium signalling for glucose-stimulated insulin secretion | T2D | Loss of |

[12] |

| FOXO1 | Gluconeogenesis regulation | Promotes gluconeogenic gene expression | T2D | Insulin resistance, hyperglycemia | [12] |

| NF- |

Mediates inflammation | Regulates pro-inflammatory cytokines | T1D, T2D | [13] | |

| SREBP1c | Lipogenesis regulation | Induces genes involved in lipid synthesis | T2D | Hyperlipidemia, hepatic steatosis | [14] |

| HNF4 |

Regulates glucose-responsive genes | Activates SLC2A2, GCK | T1D, T2D, MODY1 | Impaired insulin secretion | [15] |

| KLF11 | Suppresses |

Represses pro-apoptotic BAX | T2D | [16] |

TFs, Transcription factors; PDX1, pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1;

MAFA, v-Maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog A;

FOXO1, forkhead box protein O1; NF-

Additionally, Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4

As well as the TFs involved in pancreatic development and differentiation, other TFs have been implicated in diabetic complications. These include CCAAT enhancer binding protein beta (CEBPB), Jun proto-oncogene (JUN), and Fos proto-oncogene (FOS), which have all been implicated in vascular calcification (VC). High-glucose-induced activation of CEBPB upregulates miR-32–5p [20], downregulates the protective regulator of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation GATA binding protein 6 (GATA6), and promotes VC in T2D [20]. This could provide an example of how TFs interact with diabetic vascular pathology. Other TFs implicated in hepatic gluconeogenesis are FOXO1 and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) [18, 20]. Dysregulation of FOXO1 promotes gluconeogenic gene expression and perpetuates a state of insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia, with PEPCK, a transcriptional target of FOXO1, being a key mediator of glucose overproduction [20].

Some TFs have opposing functions in diabetes. For example, mothers against

decapentaplegic homolog 3 (SMAD3) and PDX1 are representative

of the bifunctional nature of TFs in diabetes, with SMAD3 inhibiting

insulin transcription and promoting

TFs contribute to T1D and T2D through shared but distinct mechanisms, suggesting

that their roles in the pathogenesis of diabetes are multi-layered. While

PDX1 and NEUROD1 are essential in both T1D and T2D because of

their essential roles in

Pancreatic islet TFs are among the most important regulators of

Dysregulation of the action of the TFs NKX6.1 and the regulatory factor

X (RFX) family is highly implicated in diabetes pathogenesis. NKX6.1

maintains

Specific TFs control insulin biosynthesis and secretion at both levels. For

example, Hasnain et al. (2014) [17] showed that interleukin (IL)-22

could rejuvenate glucose-induced insulin secretion by inhibiting endoplasmic

reticulum stress caused by proinflammatory cytokines. This illustrates how TFs

maintain

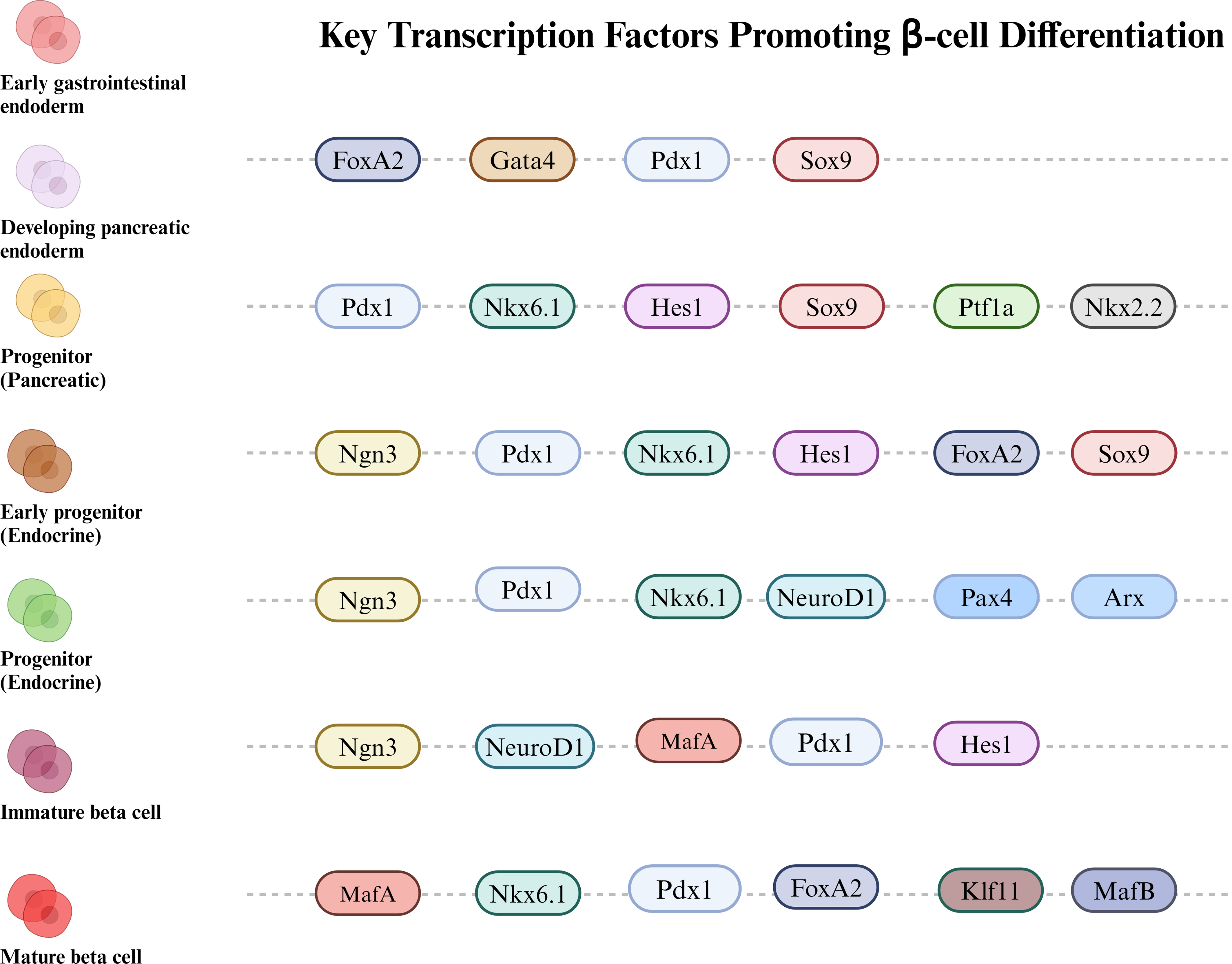

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of how various TFs

sequentially contribute to the

TFs in insulin-responsive tissues, such as the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue, are critical for maintaining glucose and lipid homeostasis. Dysfunctional activity seriously underlies the development of insulin resistance and T2D [30].

FOXO1 is an essential modifier of hepatic glucose metabolism that mediates gluconeogenesis in response to metabolic and carbohydrate signalling. Stojchevski et al. (2024) [31] demonstrated that in a model of induced insulin resistance, increased FOXO1 activity leads to higher hepatic glucose output through the upregulation of gluconeogenic genes, thereby exacerbating hyperglycaemia. More importantly, the interaction of FOXO1 with a key insulin signalling component, insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2), further supports the role of FOXO1 in perpetuating insulin resistance and disturbing glucose metabolism during chronic states [22, 32].

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR

SREBP1c, through Akt signalling, is an effective inducer of lipogenic genes in the insulin response, which requires nuclear trafficking in the endoplasmic reticulum followed by proteolytic processing for nuclear translocation to activate target gene expression [33, 34]. In insulin-resistant states, however, where this is impaired, apart from disturbing glucose homeostasis, SREBP1c unleashes uncontrolled lipogenesis, leading to hyperglycaemia, hyperlipidaemia, and hepatic steatosis. Insulin resistance is characterised by metabolic dysfunction and further drives the development of diabetes.

Carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP) is a glucose-responsive transcription factor that interacts specifically with carbohydrate response elements, which mediate the primary transcriptional activity of genes encoding glycolytic enzymes in response to high glucose availability [33]. This transcription factor induces glycolytic and lipogenic genes in response to a high intake of carbohydrates in the liver, including liver pyruvate kinase (LPK), which is required for the appropriate use of glucose and deposition of triglycerides [33, 35]. The state of its phosphorylation controls its activity, that is, its DNA-binding ability and subsequent transcriptional activity. This marks the final role attributed to TFs, such as ChREBP, in maintaining blood glucose levels.

These interactions in insulin-responsive tissues are integrated into complex

networks that regulate glucose and lipid metabolisms. For example, insulin,

through Akt, activates SREBP1c but inhibits FOXO1 in the liver,

and this reciprocal regulation maintains the balance between glucose production

and lipogenesis [32, 35]. Insulin signalling in skeletal muscle regulates the

expression of TFs responsible for glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation, thus

playing a critical role in maintaining insulin sensitivity. Thus, TFs such as

PPAR

Recent studies have focused on how some TFs, including anterior open (Drosophila

ETS transcription factor) (AOP), FOXO, and pointed (Drosophila ETS transcription

factor) (PNT), interact in hepatic and adipose tissues to change the metabolic

rate and, as a result, longevity [10, 36]. In the skeletal muscle, factors such

as fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) stimulate glucose uptake and lipid

metabolism through signalling pathways initiated by AMPK and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1),

which control PGC-1

Insight into such interactions may provide a general understanding of possible therapeutic approaches that target TFs to improve insulin resistance and T2D. Such tissue-specific actions and systemic interactions of regulators may reveal unique ways to restore metabolic imbalance.

TFs are critical regulators of gene expression related to the inflammatory and

immune responses. They are molecular switches that drive the expression of genes

essential for various immune processes [13].

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-

The STAT family of TFs, particularly STAT4, have emerged as

critical regulators in immune responses implicated in the pathogenesis of

diabetes [8, 21]. Induction by cytokines, such as IL-12, triggers

STAT4-dependent transactivation of IFN-

Interferon Regulatory Factors (IRFs) modulate the expression of chemokines in

the context of chronic inflammation associated with diabetes and, by doing so,

prolong the infiltration of immune cells into the sites of inflammation, creating

a continuous inflammatory environment that contributes to insulin resistance and

metabolic dysregulation [10, 37]. Abnormal IRF function disrupts the balance

between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators, characterising chronic inflammation

in T1D and 2 diabetes [37, 38]. Therefore, the regulation of chemokines and

inflammatory responses places IRFs in a critical role in the development of

diabetes. IRF5 and AP-1 further exacerbate diabetic inflammation. The

activation of IRF5 leads to M1 macrophage polarisation, which results in

enhanced TNF-

Chronic inflammation mediates a positive feedback loop by inducing several TFs

that in turn promote

Anti-inflammatory treatments decrease

CHOP is an essential mediator of apoptosis after ER stress, and while necessary

to maintain cellular homeostasis, it becomes deleterious after stress if it is

highly activated [9]. This further complicates the understanding of

Another key player is represented by JNK and its corresponding JNK pathway,

which is implicated in the

By its very nature, hyperglycaemia impairs the activity of key TFs, further

promoting

Other critical oxidative stress pathways, induced by activating certain TFs,

also induce

Through interacting and regulatory networks, these TFs determine the balance

between survival and apoptosis of

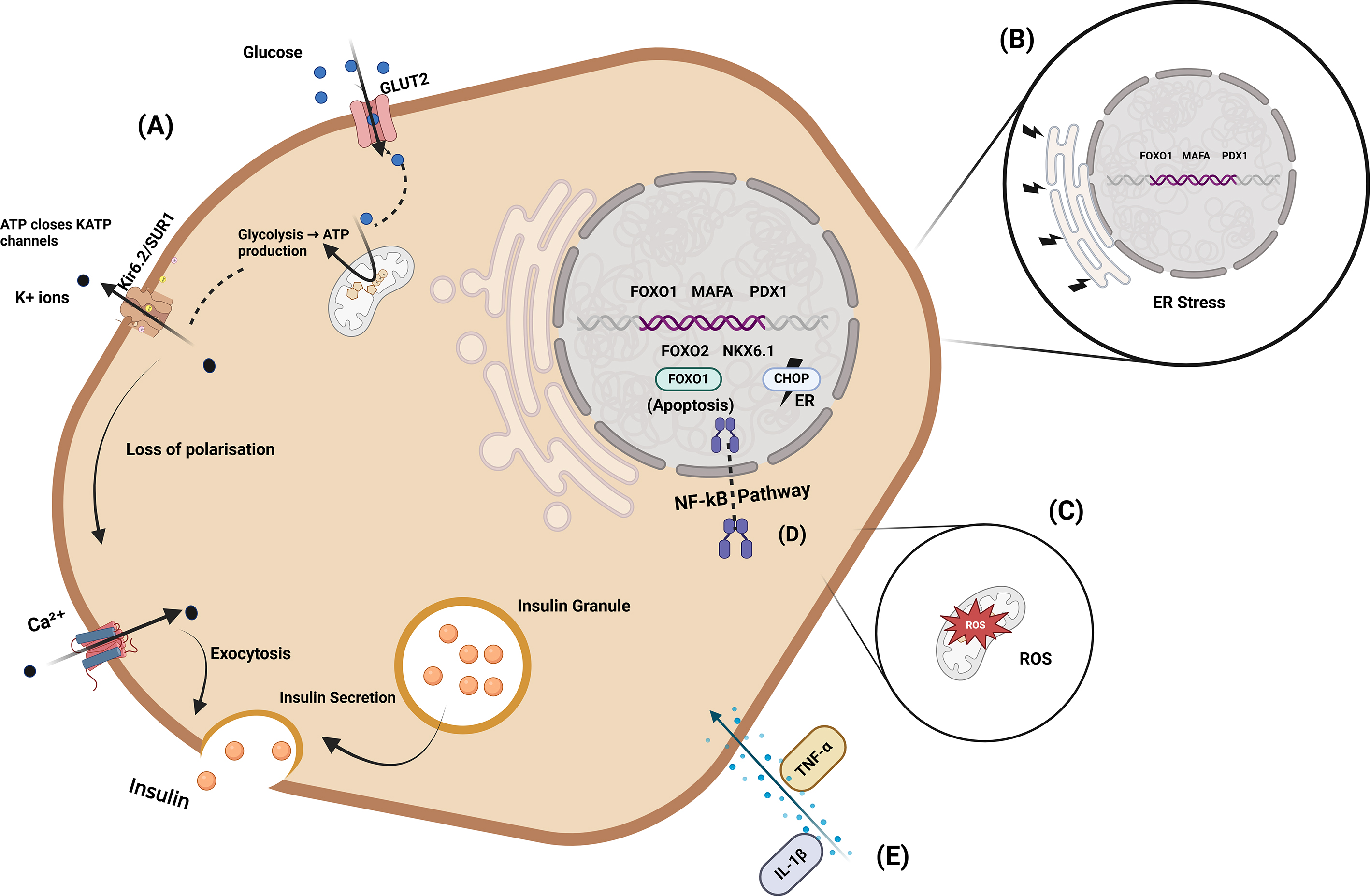

The connection between glucose metabolism (Fig. 3A), ER

stress (Fig. 3B), reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Fig. 3C), NF-

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Integrated pathways regulating insulin production and

The development of diabetes involves contributions from non-beta islet cells

through the action of transcription factors that include aristaless-related

homeobox (ARX) in

Specific TF pathways are implicated in the development of diabetic complications

including retinopathy, nephropathy, and cardiovascular diseases [4]. Increased

vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels due to HIF-1

TFs represent one of the most essential classes of gene expression regulators

and are significant players in cellular homeostasis in response to metabolic and

environmental signals. Their mode of action involves direct interaction with DNA

at specific promoter or enhancer regions, recruitment of coactivators and

corepressor proteins, and modification of chromatin structures [49]. TFs are

targets of highly sophisticated regulation at multiple levels, including

transcriptional regulation (including DNA methylation and histone remodelling),

post-transcriptional regulation (such as microRNA (miRNA)-mediated control), and

post-translational modifications (including phosphorylation and ubiquitination)

[50]. These regulatory mechanisms dynamically control the critical pathways

essential for

| Modification types | Target TFs | Effect on activity | Relevance to diabetes | References |

| Phosphorylation | FOXO1 | Suppresses nuclear activity, promotes cytoplasmic retention | Reduces |

[14] |

| Ubiquitination | EZH2 | Targeted for degradation | Reduces inflammation, enhances |

[51] |

| Acetylation | PDX1 | Enhances DNA binding and transcription | Promotes |

[34, 52] |

| Sumoylation | FOXO1, NF- |

Stabilises protein and enhances inflammatory gene expression | Exacerbates chronic inflammation in diabetes | [13, 53] |

| Deacetylation | SIRT1 | Promotes anti-inflammatory response | Reduces oxidative stress and insulin resistance | [36] |

EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2; SIRT1, sirtuin 1.

TFs linked to diabetes control essential cellular functions by interacting with

their target DNA-binding motifs, including positive regulatory domain

III/positive regulatory domain I (PRDIII/PRDI) and AP-1 [50]. For instance, MafB

activates the AP-1 motif, stimulating the cytokine promoter activity of genes

such as interferon

Generally, post-translational modifications are essential for fine-tuning the activity of the TFs involved in diabetes. Phosphorylation is likely the most important process in post-translational mechanisms. Phosphorylation is expected the most important step in these processes. FOXO1, for instance, undergoes insulin-induced phosphorylation at sites such as Thr-24, Ser-256, and Ser-319, which prevents its translocation into the nucleus and causes its retention in the cytoplasm, thereby hindering its transcriptional activity [14]. Furthermore, the phosphorylation of Ser-256 may be subjected to additional phosphorylation events that allow interaction with nuclear export proteins. Similarly, phosphorylation affects TFs such as SREBP1c, where signalling pathways regulate its expression via factors such as specificity protein 1 (Sp1) and liver X receptor (LXR), modulating the transcription of target genes [14].

Ubiquitination affects the stability of TFs. For example, the E3 ligase F-box/WD

repeat-containing protein 7 (FBW7) targets enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) for

proteasomal degradation [14]. Lower levels of FBW7 in T1D favour the stability of

EZH2 and enhance

Under ER stress FOXO1 becomes Sumoylated which maintains its nuclear

localisation and increases the activity of pro-apoptotic genes such as

CHOP [9, 57, 58]. The study reveals that sumoylation of NF-

Acetylation and deacetylation are dynamic epigenetic modifications that regulate the extent of gene expression. Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) catalyse the addition of an acetyl group to histones, maintaining an open configuration of chromatin with active transcription [61]. On the contrary, histone deacetylases remove the acetyl groups from histones, enabling chromatin’s condensation and inhibiting transcription [56, 61]. The process of DNA repair is regulated by histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and HDAC2 histone deacetylases, either directly altering the key histone residues histone H3 lysine 56 (H3K56) and H4K16, which affect the choice of repair pathway [51]. The other family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent deacetylases consists of sirtuins, which regulate stress responses and metabolic processes, and thus participate in maintaining cellular homeostasis under conditions of metabolic stress.

Sumoylation is the post-translational attachment of small ubiquitin-like modifier proteins that links the stability, localisation, and activity of TFs to oxidative or metabolic stress [43, 53]. This modification supports cellular adaptation because it mechanistically influences the expression of stress-related genes that are essential for maintaining homeostasis and evading apoptosis [42, 43].

miRNAs are important post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression through

the specificity of their binding to mRNAs, leading to either the prevention of

translation or the degradation of these mRNAs [62]. For

instance, miR-709 was previously identified to directly target the TFs CCAAT

enhancer-binding protein

Epigenetic modifications determine the activity of transcription factors that control gene expression and influence the development of diabetes. Transcription factor expression shows a connection with DNA methylation which functions as a crucial epigenetic mechanism through changes in the methylation status of cytosine-phosphate-guanine dinucleotide (CpG) sites [65, 66]. Environmental exposure may induce methylation changes in genes that control inflammation, which is a risk factor for the development of diabetes. For example, DNA methylation may target TFs, such as bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) and basic leucine zipper ATF-like transcription factor 3 (BATF3), which repress the expression of their respective genes or be deposited on their target genes, thus preventing correct target regulation by these factors. The methylation pattern changes impact both immune responses during cytomegalovirus infection and diabetes susceptibility [65]. The mentioned case stands as a single instance demonstrating how methylation changes control diabetes-related biological processes.

Post-transcriptional control by miRNAs functions as a vital mechanism for gene

expression regulation in diabetes beyond DNA methylation. miRNAs are small

molecules of non-coding RNA which attach to specific mRNA targets which results

in mRNA degradation or translational blockage. The microRNA miR-709 targets

transcription factors CEBPA and MYC directly which affect glucose metabolism and

Non-coding RNAs include long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and miRNAs, which are

major regulators of epigenetic modifications of transcription factor genes.

lncRNAs can act as circRNAs (ccRNAs), thus regulating miRNA availability and the

number of TFs [67]. lncRNA myocardial infarction-associated transcript (MIAT)

affects transcription factor expression indirectly by changing intracellular

signalling, which includes TGF-

Histone modifications including acetylation and methylation are essential for

chromatin accessibility and transcriptional activity. High levels of acetylated

histone three (H3) within myoblasts with reduced vacuolar protein sorting

associated protein 39 (VPS39) indicate disturbances in the differentiation

processes associated with diabetes [65]. In a somewhat related scenario, high

glucose levels cause changes in the degree of histone acetylation, for example,

histone 3 lysine 9 and 14 (H3K9/K14), and reduce repressive trimethylation marks

on H3K9, thus allowing for the perpetual activation of inflammatory genes, such

as IL-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) [51]. Increased lipid

levels, including oxidised low-density lipoprotein (LDL), trigger active

epigenetic reprogramming and maintain both proinflammatory responses and

metabolic disorders. Hence, environmental stressors such as high glucose and

lipid levels would strongly influence epigenetics, particularly in endothelial

cells and monocytes, resulting in long-lasting changes in gene expression

observed in metabolic and cardiovascular disorders [65]. The lncRNA

metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1) maintains

NF-

Epigenetic therapies targeting DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and HDACs are promising approaches for restoring transcription factor regulation in diabetes [65]. Dietary extremes of lipid and carbohydrate consumption, as defined by the IDECG Working Group, have been shown to modulate DNA methylation patterns and thereby alter transcription factor accessibility and downstream gene expression [69]. Simultaneously, HDAC inhibitors improve histone acetylation, thereby increasing chromatin openness and transcriptional activity [65]. Such epigenetic therapies could offer a potential approach for correcting dysregulated gene expression and slowing diabetes progression Table 3 (Ref. [31, 50, 56, 70, 71]) summarises epigenetic modifications influencing TFs and their clinical implications in diabetes.

| Modification | Target gene/factor | Impact on gene expression | Clinical implication | References |

| DNA methylation | NF- |

Reduces transcriptional activity | Suppresses pro-inflammatory responses, reduces |

[50] |

| Histone acetylation | PDPX1 | Enhances chromatin openness | Improves insulin secretion and |

[71] |

| Histone methylation | IL-6 | Increases inflammatory gene expression | Exacerbates chronic inflammation and insulin resistance | [70] |

| Non-coding RNAs | PPAR |

Regulates lipid metabolism gene expression | Reduces lipid accumulation, improves insulin sensitivity | [31] |

| lncRNA-mediated modification | TGF- |

Impacts TFs indirectly | Alters |

[56] |

PPAR

Therapeutic interventions aimed at modulating these transcription factors have,

therefore, become therapeutic targets in antidiabetic treatment approaches,

primarily through the enhancement of

PDX1 is critical for

Similarly, NEUROD1 is essential for

MAFA is a key modulator of the glucose-sensing pathway, supports

insulin secretion and

Other key transcription factors implicated as general regulators of metabolic

pathways, including FOXO1, PPAR

Epigenetic treatments add another layer of complexity to target transcription

factors in diabetes. Inhibitors of HDACs and DNMTs-enzymes that modify chromatin

accessibility can indirectly influence the transcription and activity of

transcription factors [65]. Such methods have shown promise in restoring

appropriate gene expression in

The therapeutic potential associated with the modulation of TFs in diabetes reflects the advances that have been made in understanding their role in disease mechanisms Table 4 (Ref. [7, 11, 12, 37, 41, 73, 78, 79]) outlines therapeutic strategies for targeting transcription factors in diabetes management, including their mechanisms and challenges. Although there have been valuable insights into preclinical studies and early clinical trials, developing safe, selective, and effective treatments is a major barrier to the translation of TFs into diabetes therapeutics.

| Transcription factor | Therapeutic approach | Mechanism of action | Challenges | References |

| PDX1 | Gene therapy | Restores |

Precision targeting of |

[12, 79] |

| NEUROD1 | Pharmacological modulator | Enhances |

Off-target effects, in vivo modulation issues | [7, 11, 73] |

| FOXO1 | Inhibitor | Reduces |

Systemic side effects due to broad activity | [12] |

| SREBP1c | Modulator | Reduces lipogenesis and hepatic steatosis | Difficulties in achieving tissue-specific action | [41, 78] |

| NF-κB | Anti-inflammatory drugs | Suppresses pro-inflammatory pathways | Risk of immunosuppression | [37] |

Transcriptional activators based on the clustered regularly interspaced short

palindromic repeats/deactivated Cas9 system (CRISPR/dCas9) system allow targeted

overexpression of PDX1 in

Transcription factors are instrumental targets for therapeutic intervention in

treating the complex pathogenesis of diabetes. They are relevant to disease

progression, given their key roles in beta-cell function, glucose metabolism, and

inflammation. Therapeutic restoration approaches for transcription factors,

including PDX1, NEUROD1, and MAFA, have shown promise,

whereas modulation of FOXO1, SREBP1c, and PPAR

Future research should focus on delivery systems, such as tissue-specific gene

therapy and advanced drug delivery techniques, to achieve greater therapeutic

specificity. Studying combinatorial approaches using transcription factor

manipulation combined with different metabolic interventions may yield additional

benefits. This calls for increasing insights into transcriptional networks,

especially the mutual influences between transcription factors and epigenetic

regulators when developing new therapeutic approaches. Overcoming these issues

with thorough preclinical and clinical testing will be important to ensure that

transcription factor-based therapies can be safely and effectively applied to

treat diabetes. Also, future research should focus on single-cell multi-omics

techniques to investigate TF networks within human islets from various diabetes

subtypes. Light-activated dCas9 among other inducible CRISPR systems presents a

method for controlling TF activity during specific time periods. Patient-derived

organoid models will help demonstrate the effects of genetic variations in

transcription factors such as HNF4

TFs, transcription factors;

NKP and AMS established the concept, NKP wrote the initial draft, AMS and NTN provided advice on the structure of the review, all authors edited the manuscript, and all authors read and approved the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not Applicable.

Not Applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.