1 Department of Infectious Diseases, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, 430060 Wuhan, Hubei, China

Abstract

Histones were once thought to be exclusive to the nucleus, but were recently discovered in the extracellular space, where they play important roles in disease pathogenesis. In addition to their traditional functions in chromatin organization and gene regulation, extracellular histones also serve as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), drive inflammation and immune responses, and are responsible for the progression of diseases such as sepsis, autoimmune diseases, and inflammatory diseases. To effectively target extracellular histones and improve disease progression, this review begins with the release and pathogenic mechanisms of histones and explains the main pathogenic mechanisms of extracellular histones in many diseases. In addition, common antagonistic methods for targeting extracellular histones are summarized, and the mechanisms that need to be further studied at this stage are discussed, providing new directions for the future development of effective and safe histone-targeting drugs.

Keywords

- extracellular histones

- inflammation

- immune response

- therapy

Histones are a group of highly conserved, basic, positively charged proteins consisting of five histone subtypes, that are functionally categorized into linker histones (H1) and core histones (H2A, H2B, H3, H4). They can also be classified based on their amino acid composition into lysine-rich (H1, H2A, H2B) and arginine-rich (H3, H4) histones [1]. Within the nucleus, histones are the primary components of nucleosomes, and their complex and diverse posttranslational modifications (PTMs) play critical roles in key physiological processes, such as DNA transcription, replication, and repair [2]. Abnormal histone modifications within the nucleus have been implicated in the pathogenesis of various diseases [3]. Recent studies have increasingly indicated that histones released into the extracellular space from damaged or activated cells are considered novel damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). These extracellular histones exhibit significant toxicity, immune stimulation, and procoagulant functions both in vivo and in vitro [4, 5]. They can stimulate endothelial cells, macrophages, and other immune cells through specific receptors, thereby inducing the onset of conditions such as sepsis, liver injury, and myocardial infarction [6, 7, 8]. In this review, we focus on how extracellular histones mediate injury and immune stimulation, and we discuss the current status and future prospects of targeting extracellular histones.

To coordinate the accessibility of a vast and orderly genome, eukaryotic cell nuclei form highly organized chromatin structures through the binding of DNA molecules to proteins, primarily conserved histones [9]. Histones are basic proteins found within the nucleus that neutralize the acidic residues of DNA, thereby contributing to the structural organization and stability of chromatin [10]. Generally, the nucleosome structure can impede DNA transcription through physical obstruction and bending of the DNA [11, 12].

However, histones can also influence chromatin compaction and accessibility, thereby regulating gene expression through posttranslational modifications at their tail or central globular domains, such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and glycosylation [13, 14]. For example, acetylation of histone H4 at lysine 16 (H4K16) has been shown to reduce chromatin compaction and increase transcription both in vitro and in vivo [15]. In addition to these direct effects, histone modifications can recruit effector proteins to activate downstream signaling pathways or influence the recruitment of chromatin-modifying transcription factors, thus exerting indirect regulatory effects [16].

Therefore, under homeostatic conditions, histones are confined within the nucleus, where they utilize posttranslational modifications to regulate chromosome structure and chromatin accessibility, participating in transcriptional regulation.

Histones are considered among the most positively charged proteins, a characteristic that helps maintain chromosome structure within the nucleus. However, once released into the extracellular space, this property can trigger inflammatory responses and various harmful effects, including tissue damage. In 2002, research first demonstrated that core nucleosome histones from apoptotic cells can dissociate from chromatin and be released into the extracellular environment, which is detectable in cell lysates prepared with nonionic detergents [17]. In 2003, studies in patients with sepsis revealed significantly elevated plasma nucleosome levels due to the involvement of apoptosis in severe sepsis and septic shock [18]. In 2009, animal models revealed that intravenous infusion of histones was lethal to mice, whereas the administration of histone antibodies and activated protein C had protective effects. Elevated histone levels have also been detected in the serum of patients with sepsis and are correlated with poor prognosis and high mortality rates [18, 19, 20].

Under normal circumstances, histones are retained within the nucleus, where they regulate chromosomal stability and epigenetic control. During programmed or nonprogrammed cell death, histones can be released into the extracellular space from any nucleated cell. Additionally, histones can be actively secreted by living cells, are located on the surfaces of vesicles, and interact with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) to initiate signaling [21, 22]. All five histone subtypes can be detected in extracellular media such as blood, where they can function in a free form, unconstrained by other macromolecules, or be released as part of nucleosomes bound to DNA or in association with other proteins.

Extracellular histones act as DAMPs, inducing severe local and systemic inflammatory responses through mechanisms such as cytotoxicity, immune stimulation, and coagulation. For example, extracellular histones can induce signaling through TLR4 and TLR2, resulting in cytotoxic effects on endothelial and renal tubular epithelial cells while eliciting immune stimulation in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) [23].

Although histones are typically located within the nucleus, they can also be detected in circulation, on cell surfaces, or within the cytoplasm. Histones can be expelled from living cells in the form of exosomes, but more commonly, they are released through dying cells. Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, induces unique posttranslational modifications of histones that facilitate chromatin condensation and degradation [21, 24, 25, 26]. During the apoptotic process, cysteine protease-activated DNase I mediates DNA fragmentation, leading to the dissociation of histones from nucleosomes, which aids in the expulsion of histones from cells during the later stages of apoptosis [26]. Additionally, during apoptosis, human lymphocytes, leukocytes, and monocyte lines passively release nucleosomes from microvesicles, increasing the extracellular histone content [27]. Beyond apoptosis, ferroptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis are also significant sources of extracellular histones [28].

In nonprogrammed cell death, such as necrosis, cell membrane rupture results in the leakage of cellular contents into the extracellular space. Although this process does not exhibit characteristics of apoptosis, such as chromatin fragmentation or the activation of intracellular nucleases, evidence shows that necrotic mouse or human cells can release histones in either bound or unbound states. Once released, these histones can perform DAMP-like activities, causing tissue and organ damage [29, 30, 31].

In addition to histones released from apoptotic and necrotic cells, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) released by neutrophils are another important source of extracellular histones, excluding H1 [32]. NETs are complexes formed from neutrophil elastase (NE), myeloperoxidase (MPO), DNA, and histones, which have antimicrobial and disease-fighting functions [33]. Classical NETosis is considered a specific form of neutrophil death associated with the release of NETs. Under inflammatory conditions, neutrophils are recruited to sites of infection or tissue damage, where activated neutrophils release histone-containing NETs, which serve as part of the innate defense to capture and eliminate pathogens [34]. However, abnormal NET release can also induce neighboring cells to release additional DAMPs and even trigger cell death, exacerbating inflammatory responses and tissue damage [35]. During the formation of NETs, increased intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and calcium ion concentrations activate peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4), which randomly citrullinates arginine residues on core histone tails, leading to chromatin decondensation and promoting NET formation [35]. The released citrullinated histones play significant roles in the pathogenesis and progression of various diseases.

Under physiological conditions, low levels of histone or nucleosome content can be detected in extracellular environments, such as serum [36]. However, as their concentration increases, histones can cause varying degrees of damage to peripheral tissues and organs (Table 1, Ref. [29, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42]). High levels of extracellular histones have been detected in the serum of patients with sepsis, autoimmune diseases, and inflammatory conditions [20, 43, 44]. Moreover, extracellular histone levels in patients with sepsis are negatively correlated with platelet and antithrombin levels and are closely associated with mortality rates in these patients [19]. Elevated histone levels have also been detected in the serum of patients with severe trauma and are positively correlated with the severity of the injury, the occurrence of multiple organ dysfunction, and mortality rates [45]. Similarly, high levels of nucleosomes have been detected in pediatric trauma patients and are correlated with the severity of injury and coagulopathy [46].

| Organ | Effects of histones |

| Brain [37] | Extracellular histones induce neuroinflammation |

| H1 induces microglial phagocytic dysfunction | |

| H1 directly induces neurotoxicity | |

| Exogenous infusion of histones increases infarct size and neurological scores | |

| Retina [38] | The intravitreal concentration of histones in the eyes of patients with retinal detachment is higher than that in normal eyes |

| Heart [39] | Extracellular histones induce cardiomyocyte cytotoxicity |

| Lungs [40] | Extracellular histones stimulate alveolar macrophage activation and inflammatory responses |

| Extracellular histones induce endothelial cytotoxicity and immune activation | |

| Extracellular histones promote neutrophil aggregation and NETs formation | |

| Extracellular histones induce microvascular thrombosis | |

| Liver [41] | Extracellular histones induce activation of inflammasomes within the liver |

| Extracellular histones directly induce hepatocyte death | |

| Extracellular histones activate hepatic stellate cells, promoting liver fibrosis | |

| Kidney [42] | Extracellular histones induce cytotoxicity in renal tubular epithelial cells |

| Extracellular histones promote the formation of NETs, further exacerbating kidney damage | |

| Pancreas [29] | Necrotic acinar cells can release histones |

| The H3-neutralizing antibody provides significant protection against experimental acute pancreatitis |

Abbreviations: NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps.

The release of NETs is a significant source of extracellular histones, with citrullinated histone H3 (CitH3) being a major component of NETs and widely used as a surrogate marker for NETs in both in vivo and in vitro studies [47]. Given the critical role of NETosis in the occurrence and progression of endometrial cancer, serum CitH3 and cell-free DNA (cf-DNA) may serve as noninvasive biomarkers for tumor-induced systemic effects in endometrial cancer [48]. Additionally, as important components of NETs, citrullinated and carbamylated histones are associated with the severity of periodontal disease in patients [49].

Furthermore, components of NETs, including extracellular histones, are believed to play significant pathogenic roles during the early stages of SARS-CoV-2 infection, potentially serving as biomarkers for assessing disease status in patients with COVID-19, with implications for clinical decision-making [50].

Extracellular histones lead to various pathological changes through multiple mechanisms, contributing to conditions such as sepsis and trauma, as well as damage and fibrosis in the lungs, heart, kidneys, liver, and brain [39, 51]. In the context of liver fibrosis, extracellular histones can activate hepatic stellate cells, promoting the progression of liver fibrosis [52]. In mouse models of sepsis, intervention with histones has been shown to be lethal and can induce organ damage [53, 54]. Additionally, existing studies indicate that peripheral extracellular histones can cross the blood‒brain barrier, collectively damaging brain cells along with histones released by cells in the brain, thereby promoting inflammatory responses [55].

Given the significant role of extracellular histones in trauma and inflammation-related diseases, neutralizing extracellular histones is considered an important strategy for treating severe tissue injuries, inflammation, and even infections. Molecules such as activated protein C (APC), heparin, and histone antibodies have been identified as important means of neutralizing extracellular histones. Therefore, in-depth research into the specific mechanisms by which extracellular histones contribute to disease pathogenesis is crucial for targeting extracellular histones and improving disease progression.

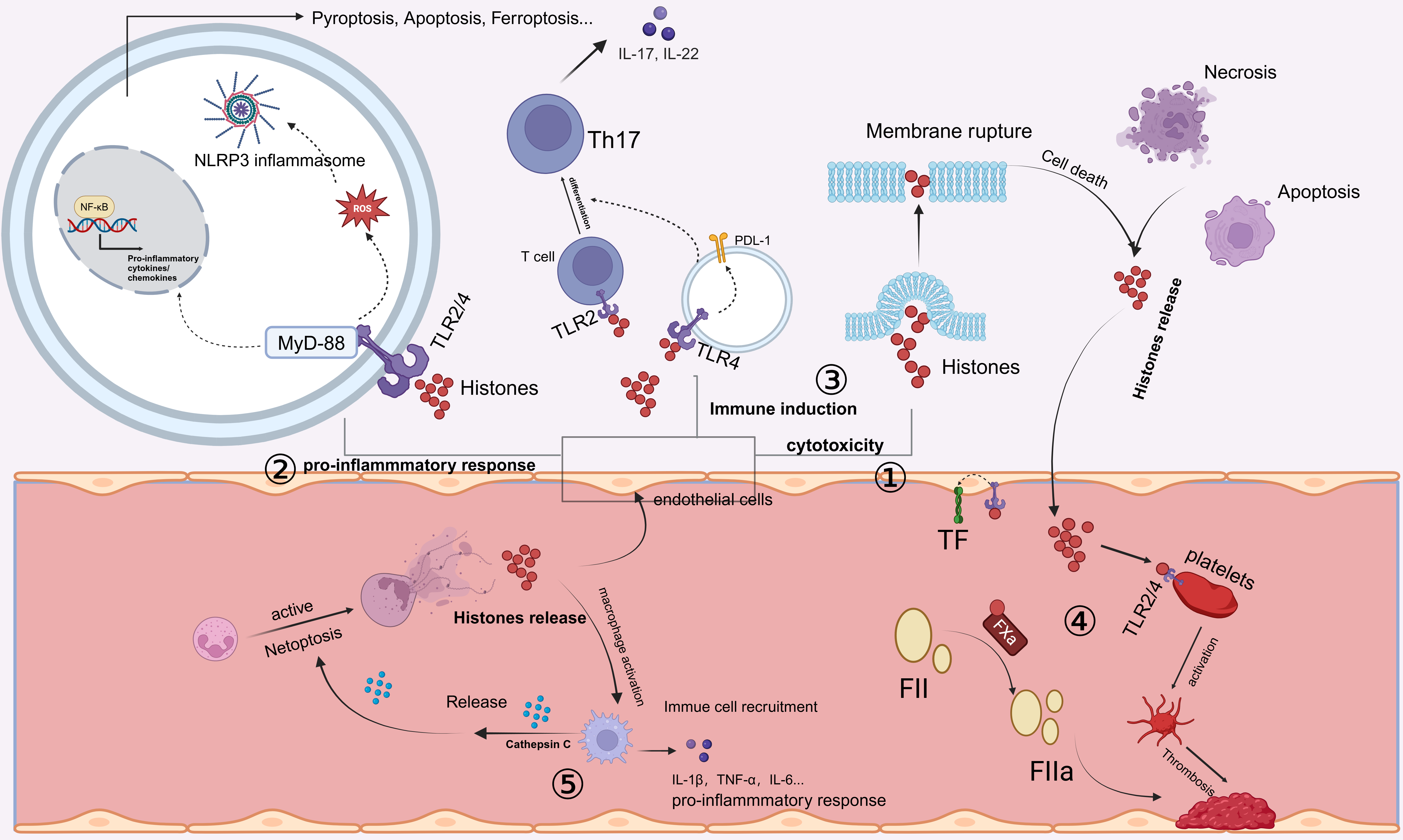

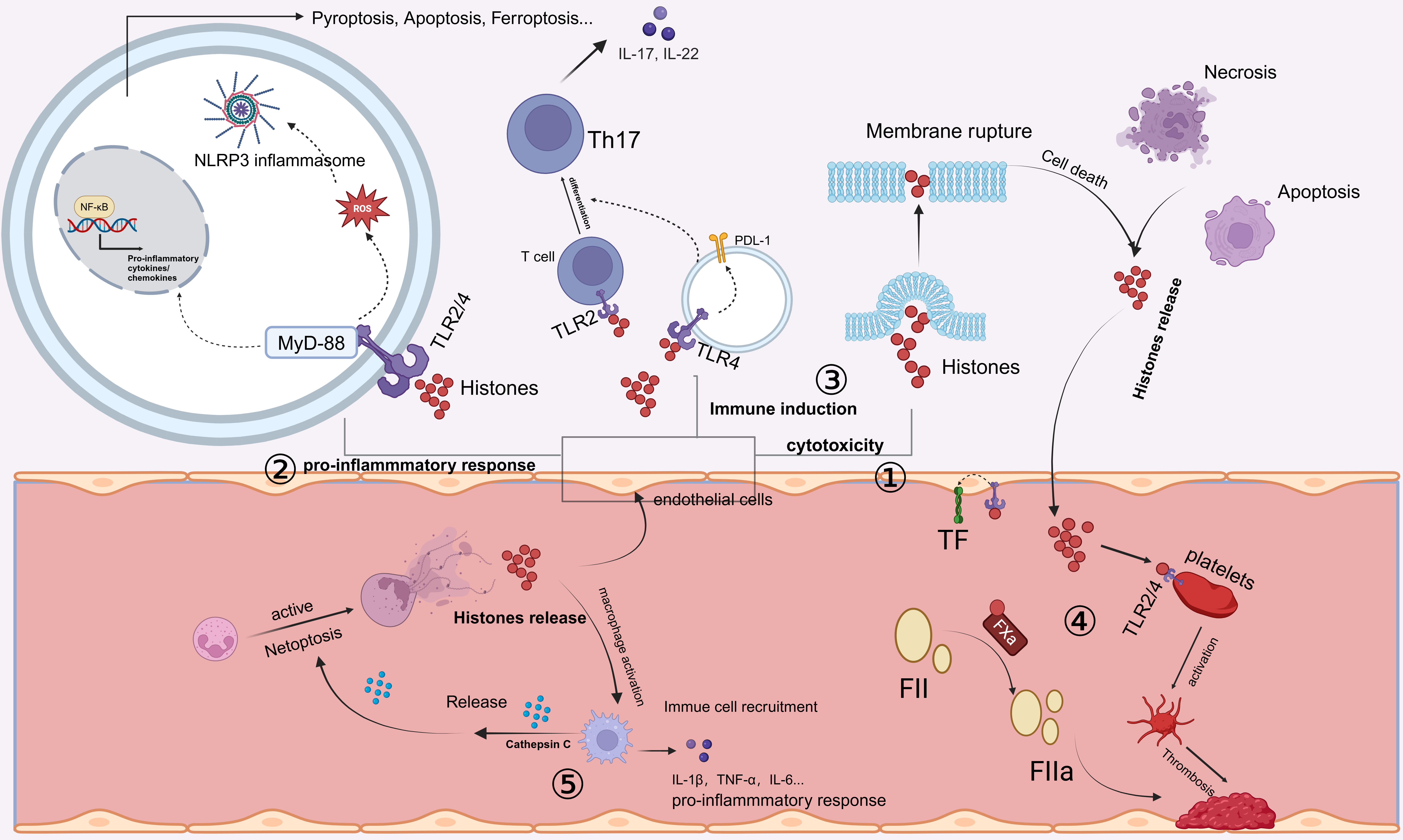

The spatial localization of histones within the body influences their roles and functions. In the circulation, the damaging effects of histones on tissues and organs exhibit a concentration-dependent relationship. Numerous studies have shown that extracellular histones mediate the progression of inflammation and organ injury through several critical mechanisms, including cytotoxicity, immune stimulation, and vascular coagulation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Release and mechanisms of action of extracellular histones.

Extracellular histones can be released by cells undergoing cell death processes

such as necrosis or apoptosis. In addition, activated neutrophils can undergo

NETosis, releasing neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which contain cytotoxic

histones. ① Extracellular histones exhibit direct cytotoxicity by

disrupting cell membranes, thereby inducing cell death. ② Extracellular

histones bind to Toll-like receptors (TLR2 or TLR4), activating the MyD88

signaling pathway. This leads to the activation of nuclear factor kappa-B

(NF-

Histones and their histone-derived antimicrobial peptides (HDAPs) were first reported to possess antimicrobial activity in 1942 [56]. Subsequent studies revealed that histidine-rich histones exhibit effective bactericidal properties, surpassing the activity of many antimicrobial agents [57]. Histones, as antimicrobial biomolecules, constitute part of the skin’s defense system. Similarly, the lysine-rich histone H2B and arginine-rich histones H3 and H4 inhibit Escherichia coli growth via outer membrane protein T cleavage [58]. The complex mixture of calf thymus histones shows notable bactericidal activity against Bacillus thuringiensis [59]. Consequently, synthetic peptides based on histone amino acid sequences possess antimicrobial properties, making histone templates useful for designing new antimicrobial peptides [60]. A recent study showed that histone H3.1 exhibits effective bactericidal activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, whereas its citrullinated form reduces this activity in cystic fibrosis lungs, suggesting a potential therapeutic target for cystic fibrosis-related lung infections [61].

However, although histones exhibit potent antimicrobial properties, their cytotoxicity at high concentrations limits their therapeutic application. Given this dual role, developing histone-derived peptides with reduced cytotoxicity is essential. A study on various histone H3 molecular fragments revealed that histone H3 fragments 35–68 and 69–102 display antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities, respectively [62].

In addition to acting as direct antimicrobial agents, extracellular histones, as major components of NETs, contribute to host defense. Extracellular NETs, which form extracellular fibrils on cell surfaces, bind both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, leading to virulence factor degradation and bacterial death. Core histones, which constitute 70% of NETs, are considered the primary antimicrobial components in biological defense [63].

Histones belong to the family of cell-penetrating peptides; however, due to their lack of specificity, they can induce cell death in a variety of cells while exerting their antimicrobial activity by forming pores in the membranes of prokaryotic organisms [64]. Research has shown that histone H4 can directly bend lipid bilayers, inducing the formation of pores within the lipid bilayer. Furthermore, the addition of cholesterol to lipid mixtures enhances the ability of histone H4 to bend the lipid bilayer [65]. Interestingly, cholesterol levels in the plasma membrane can be altered by conditions such as hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, which are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases [66]. Consequently, histone-induced cell death may exacerbate the progression of such diseases and mediate adverse prognoses.

Extracellular histones exhibit cytotoxicity both in vitro and in vivo. Mouse studies demonstrated dose-dependent lethality upon injection of histone mixtures, with histone-neutralizing antibodies or activated protein C (APC) partially reducing mortality [20]. Extracellular histones are major mediators of mortality during sepsis and are correlated with patient mortality rates. Intravenous injection of histones induces a pseudoseptic shock state in mice, accompanied by neutrophil aggregation, vascular thrombosis, and fibrosis in the lungs [20, 67]. In autoimmune arthritis, extracellular histones are the principal mediators of synovial cell and macrophage lysis [68].

Endothelial cells are common targets of extracellular histones, and elevated histone levels disrupt endothelial permeability and promote dysfunction, potentially leading to fatal organ failure [69]. In addition to their effects on endothelial cells, extracellular histones are directly toxic to intestinal epithelial cells, neurons, and microglia and play roles in neuroinflammatory damage [37, 70, 71]. A recent study demonstrated the cell type-specific cytotoxic effects of extracellular histones, with histone H1 exhibiting neurotoxicity, whereas core histones lack this effect. Notably, histone H1 can kill neurons without affecting astrocytes or microglia [55].

The immune-stimulating function of histones is another major mechanism through

which extracellular histones induce damage. High concentrations of histones

induce widespread cytotoxic damage, whereas low concentrations of histones can

stimulate the production of chemokines and cytokines. Extracellular histones can

activate oxidative stress pathways, which, in turn, promote the activation of the

protein domain associated protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and subsequent

interleukin-1beta (IL-1

In addition to directly inducing inflammatory responses, endothelial cells are also among the primary target cells for immune responses induced by extracellular histones. Extracellular histones can modulate the immunogenicity of endothelial cells. When endothelial cells are treated with histones and then cocultured with CD4+ T cells, they promote the differentiation of T cells into a regulatory T-cell subset expressing human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4). This interaction increases the number of immunosuppressive FoxP3+ T regulatory (Treg) cells, enhancing immune tolerance [77].

Extracellular histones not only indirectly regulate T-cell phenotypes by altering the immunogenicity of endothelial cells but also serve as key components of NETs. Histones can directly promote the differentiation of Th17 cells through TLR2 activation, leading to the activation of downstream pathways [78]. Moreover, similar effects have been observed in models of periodontitis, where extracellular histones can trigger the upregulation of IL-17/Th17 responses, promoting mucosal inflammation and bone destruction. This mechanism is considered a significant contributor to NET-driven inflammatory bone loss [49].

Furthermore, extracellular histones promote the differentiation of alveolar macrophages toward the M1 phenotype, stimulating the production and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines [79]. Additionally, extracellular histones can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages through nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2) receptor pathways, leading to pyroptosis and contributing to acute liver failure progression [80]. In addition to their effects on peripheral macrophage function, extracellular histones also impact immune cells within the central nervous system (CNS). Histones H1 and H3 increase the production of nitric oxide (NO) and cytokines in microglia, promoting proinflammatory activation. Notably, histone H1 disrupts phagocytic activity in microglia, further aggravating neuroinflammation [55].

NETs, a primary source of extracellular histones, play essential roles in both immune defense and pathogenesis. Citrullinated histones, major NET components, are involved in NET-induced cell death, inflammation, and tissue damage. Studies have shown that extracellular histones released by hypoxia-induced necrotic tubular epithelial cells in vitro can trigger NET formation in neutrophils, which, in turn, can induce further tubular epithelial cell death and worsen disease progression [42]. Additionally, extracellular histones released with NETs can induce alveolar macrophages to polarize toward the M1 phenotype. Activated macrophages then secrete cathepsin C, promoting neutrophil NET formation, which subsequently amplifies tissue damage through positive feedback mechanisms [79].

Ion homeostasis is crucial for maintaining cellular physiological functions and morphology. In particular, mitochondrial function is highly dependent on ion balance and is closely related to various diseases, including cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders [81]. For example, the activation of mitochondrial potassium channels may play a protective role in cardiac tissue and neurons. Conversely, the inhibition of these potassium channels can lead to cell death [82]. Additionally, ion imbalances play a significant role in the induction of inflammatory responses.

Extracellular histones affect intracellular calcium (Ca2+) homeostasis. Early studies demonstrated that exposure to histone H1 leads to increased extracellular Ca2+ influx and intracellular Ca2+ release in breast cancer cells [83]. Subsequent research has shown that circulating histones activate nonselective cation channels in the plasma membrane, rapidly increasing Ca2+ levels in endothelial cells [84]. Intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis is crucial for normal cellular function; therefore, the disruption of Ca2+ balance by extracellular histones significantly impacts tissue injury. In patients with sepsis, increased levels of extracellular histones correlate with decreased Mg2+ levels, which also relate to monocyte levels. In both in vivo and in vitro sepsis models, the addition of Mg2+ affects calcium signaling pathways, reducing histone-induced macrophage apoptosis and phagocytic dysfunction, significantly improving survival rates in mice [85].

In addition to disrupting Ca2+ homeostasis, extracellular histones affect potassium (K+) levels. In studies on septic lung injury, histone-induced calcium influx in alveolar macrophages promotes the transport and localization of two-pore domain weak inwardly rectifying K+ channel 2 (TWIK2) to the plasma membrane, facilitating TWIK2-dependent K+ efflux. This, in turn, activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in alveolar macrophages, triggering inflammatory responses [86].

Extracellular histones can trigger platelet aggregation and coagulation, which are associated with microvascular thrombosis. In septic mouse models, histone administration results in microthrombi rich in platelets and fibrin within pulmonary tissues, along with fibrin deposits in alveoli [20]. Notably, platelet depletion prevents histone-induced lethality in mice but does not prevent tissue damage [87]. Additionally, research has shown that the protective effects of heparin and albumin against tissue damage are associated primarily with the inhibition of platelet activation. In patients with sepsis, extracellular histone H3 levels negatively correlate with antithrombin levels and platelet counts, linking histone levels to coagulation abnormalities and mortality rates [19]. Similarly, the infusion of sublethal doses of histones into mice can lead to rapid depletion of platelets, which may result from their activation and aggregation. This phenomenon could also be an important factor contributing to thrombocytopenia in critically ill patients [87].

Extracellular histones of all subtypes can noncovalently bind fibrin, accelerating the lateral aggregation of fibrinogen fibrils and inhibiting fibrinolysis, thereby promoting coagulation and enhancing clot stability. Low-molecular-weight heparin therapy disrupts histone‒fibrin interactions and neutralizes the effects of histones on fibrinolysis, mitigating thrombus progression. The effects of histones on platelet activation and fibrinolytic processes underscore the importance of extracellular histones in the coagulation process [88].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that extracellular histones function as DAMPs during tissue injury, disrupting immune signaling and exacerbating tissue damage through direct cytotoxic effects on other cells. Based on the mechanisms by which extracellular histones cause damage, therapeutic strategies targeting extracellular histones can be conceived through several approaches: inhibiting the release of extracellular histones, directly neutralizing histones, or inhibiting histone signaling pathways.

NETosis is one of the primary sources of extracellular histones, with citrullination being a common modification. As part of NETs, CitH3 plays a significant pathological role in mediating tissue damage in diseases such as sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), COVID-19, rheumatoid arthritis, and periodontitis [34, 89]. Peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 (PAD4) is the key enzyme responsible for the citrullination of histone H3. In animal models, inhibiting PAD4 activity can mitigate disease progression by reducing histone release and the occurrence of NETosis [36, 90].

Drugs that directly target histones need to exert their neutralizing effect extracellularly to avoid intracellular neutralization, which could lead to cellular dysfunction. C-reactive protein (CRP) and activated protein C (APC) are endogenous proteins that are negatively correlated with histone levels in the circulation, suggesting their potential regulatory effects on extracellular histones [36]. Further research has revealed that CRP can bind to extracellular histones to form complexes, competing with histones for phospholipid binding sites [91]. This competitive inhibition prevents histones from integrating into the plasma membrane, thereby obstructing their downstream damaging signals. In both in vivo and in vitro experiments, CRP synthesis has been found to protect against the cytotoxicity of extracellular histones as well as their prothrombotic and platelet-activating effects. Moreover, CRP can bind to histone H4, reducing its cytotoxicity and assisting in the mitigation of the vicious cycle observed in patients with COVID-19 [92].

Unlike CRP, which functions through competitive inhibition by forming complexes with extracellular histones, activated protein C (APC) reduces extracellular histone levels through proteolytic degradation, thereby mitigating their cytotoxic effects [93]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that APC intervention can prevent endothelial dysfunction, organ failure, and high mortality rates caused by histone infusion [94]. However, subsequent clinical trials revealed that the use of APC did not benefit patients with severe sepsis [95]. However, ongoing research has validated the neutralizing effects of APC on histones and its ability to inhibit NET formation, thereby preventing the damaging effects of extracellular histones [93]. Given this, further purification and enhancement of APC activity are critically important. A recent study designed APC variants to develop histone-neutralizing biologics that reduce the side effects associated with APC use while enhancing its histone-neutralizing functions. This targeted approach may offer a promising avenue for therapeutics aimed at mitigating the damage caused by extracellular histones [96].

Heparin is a well-tolerated anticoagulant widely utilized in clinical settings [97]. Research has revealed that exogenously administered heparin is effective in combating SARS-CoV strains [98]. Moreover, heparin has recently been considered a candidate drug for anti-COVID-19 therapies, leading to the development of heparin-based treatments [99]. As a negatively charged polysaccharide, heparin can bind to positively charged extracellular histones, thereby neutralizing histone toxicity, excessive inflammation, and organ damage [100]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that intervention with unfractionated heparin (UFH) significantly reduces histone-induced inflammatory cytokine levels [98]. In acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) models, UFH administration hinders histone-induced alveolar macrophage activation and ameliorates lung tissue damage [72]. UFH has been tested as an adjunct therapy for sepsis in clinical trials. Furthermore, therapeutic dosages of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) can mitigate the effects of histones on fibrinolytic processes by inhibiting histone‒fibrin cross-linking, thereby increasing the efficacy of standard heparin treatment [101]. Research on pregnancy responses in placental pathways has shown that LMWH, but not aspirin, can reverse histone-induced invasion inhibition, suggesting that the protective effects of LMWH are closely related to histone neutralization [102]. Despite heparin’s significant role in histone binding and neutralization, the specific dosage threshold for heparin in animal models remains unclear; additionally, high doses may increase the risk of bleeding, limiting its further use [103]. Therefore, extensive research on heparin and its derivatives continues. Antithrombin affinity-depleted heparin (AADH), a nonanticoagulant heparin derived from UFH that depletes the anticoagulant component, effectively reduces mortality from sterile inflammation and sepsis in mouse models without increasing the risk of bleeding [99]. Additionally, M6229, a low-anticoagulant fraction of UFH, has shown marked therapeutic effects in rat models of acute and lethal inflammation induced by extracellular histones. Treatment of rats with M6229 resulted in a dose-dependent increase in activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) without bleeding complications and did not significantly affect red blood cell or platelet counts in the absence of histones [104]. Therefore, investigating heparin derivatives that minimize side effects is highly important for neutralizing histones and preventing damage, with implications for clinical application and improved disease prognosis.

Methyl

The release of histones into the extracellular environment primarily activates

the NLRP3 inflammasome or the NF-

Extracellular histones play crucial roles in the pathological processes of diseases such as sepsis and ARDS, contributing to excessive inflammatory responses, endothelial dysfunction, platelet activation, microvascular thrombosis, and organ damage. Elevated levels of circulating histones are correlated with disease severity and increased mortality rates. To alleviate tissue inflammation, mitigate organ damage, and improve the progression of histone-induced diseases, investigations of the specific pathogenic mechanisms of extracellular histones and the development of effective histone-neutralizing drugs are essential.

Research has revealed that the impact of extracellular histones on cellular and tissue damage is influenced by their posttranslational modifications. For example, citH3 is a major component of NETs and mediates inflammation and death during sepsis-induced acute lung injury (ALI), making it a potential therapeutic target in mouse models of endotoxin shock and periodontal bone destruction [108]. Conversely, in models of autoimmune arthritis, extracellular histones can induce lytic cell death in synovial and macrophages, but their citrullinated forms provide some alleviation [68]. However, acetylated histone H3.3 has been implicated in cytotoxicity and inflammatory responses that exacerbate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)-related lung damage [109]. Therefore, ongoing research must focus not only on the overall mechanisms of extracellular histone action but also on the specific modifications and variants of these histones to lay the groundwork for developing effective therapeutic drugs.

Additionally, although various therapeutic strategies targeting extracellular histones have shown potential, comparative efficacy studies are lacking. Moreover, owing to side effects or other limitations, these therapeutic agents lack validation in authoritative clinical trials and cannot yet be directly applied in clinical settings. The development of safe and effective treatments and advancements in disease therapy remain challenges that need to be addressed.

In summary, extracellular histones play crucial roles as mediators in various pathological processes, including the induction of inflammatory responses, endothelial dysfunction, intracellular calcium overload, and immune cell dysfunction. These phenomena are associated with disease onset and poor prognosis. This review delves into the mechanisms underlying extracellular histone release and its pathogenic impact while highlighting common strategies for targeting extracellular histones. This approach aims to offer novel perspectives for improving disease progression through targeted interventions against extracellular histones.

DZ: Design the manuscript framework, write and modify the manuscript, confirm the final manuscript. XZ, YW, JG: Search for related documents and information required, modify the manuscript and confirm the final manuscript. ZG: Design of manuscript ideas, ,modify and confirm the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.